The incidence and mortality rates of pancreatic

cancer (PC) have been steadily increasing; there were 441,000 cases

of PC worldwide in 2017, compared with only 196,000 cases in 1990

(1). According to epidemiological

data, PC has the lowest 5-year relative survival rate among all

solid tumors, estimated at ~13% (2). Surgical resection combined with

adjuvant chemotherapy represents the current standard of care and

the most widely adopted clinical strategy for the treatment of PC

(3). However, due to the

asymptomatic nature of early-stage PC, the majority of patients are

diagnosed at an advanced stage. Consequently, only a small subset

of patients remains eligible for surgical intervention (4). Furthermore, the development of

chemotherapy resistance, often resulting from prolonged treatment,

notably impacts both the survival and quality of life of patients

with PC. The pathogenesis of PC remains incompletely elucidated;

however, in addition to modifiable risk factors such as smoking,

alcohol consumption, obesity and diabetes, genetic mutations,

familial inheritance and a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) are

also recognized as critical contributing factors (1,5,6). The

TME of PC is a complex ecosystem composed of cancer cells, stromal

cells, immune cells and various extracellular components. PC cells

actively drive genetic mutations; stromal cells produce abundant

collagen and extracellular matrix leading to tissue fibrosis and

highly expressed inflammatory factors create a pro-inflammatory

environment. This unique TME establishes a robust foundation for

the growth and metastasis of PC (7). Therefore, deepening the understanding

of the molecular mechanisms underlying PC, developing more

effective therapeutic strategies and overcoming chemotherapy

resistance represent critical research directions that require

further exploration.

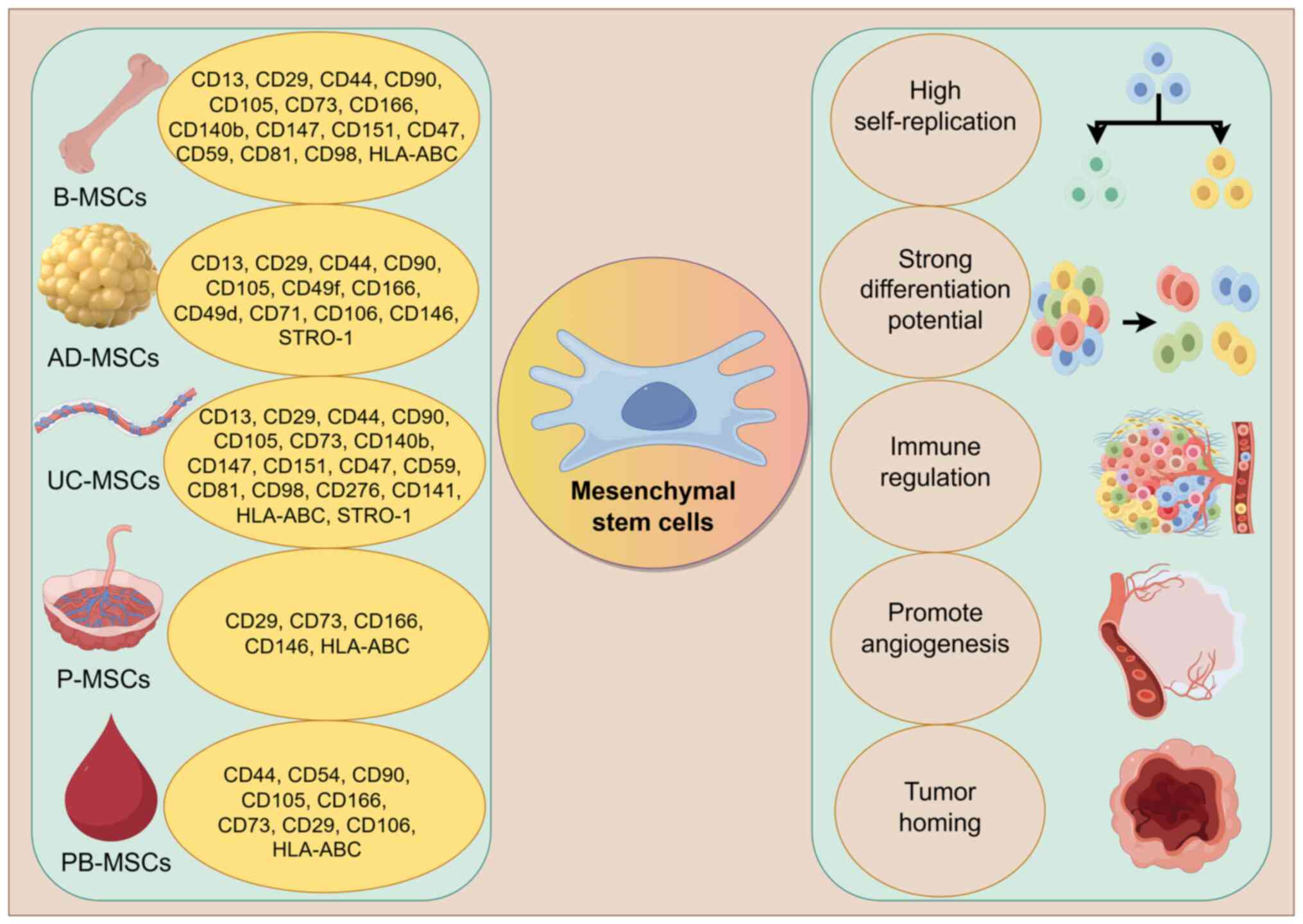

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent stem

cells characterized by high differentiation potential and strong

self-renewal capacity, which originate from the mesoderm and

ectoderm during early development (8). Studies have indicated that MSCs

actively participate in the progression of PC, including tumor

growth and metastasis of cancer cells, as well as the modulation of

TME (9–11). Studies have reported that MSCs can

promote the progression of PC by secreting pro-tumorigenic factors

(12) and differentiating into

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (13). However, other evidence suggests that

MSCs can also suppress the development of PC. For example, Mohr

et al (14) demonstrated

that systemic MSC-mediated delivery of soluble tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand, combined with X-linked

inhibitor of apoptosis protein inhibition, could inhibit PC growth

and metastasis. Additionally, IL-10-modified human MSCs were shown

to inhibit PC progression by suppressing the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α and inhibiting tumor

angiogenesis (15). The role of

MSCs in PC is closely associated with their derived EXOs (16).

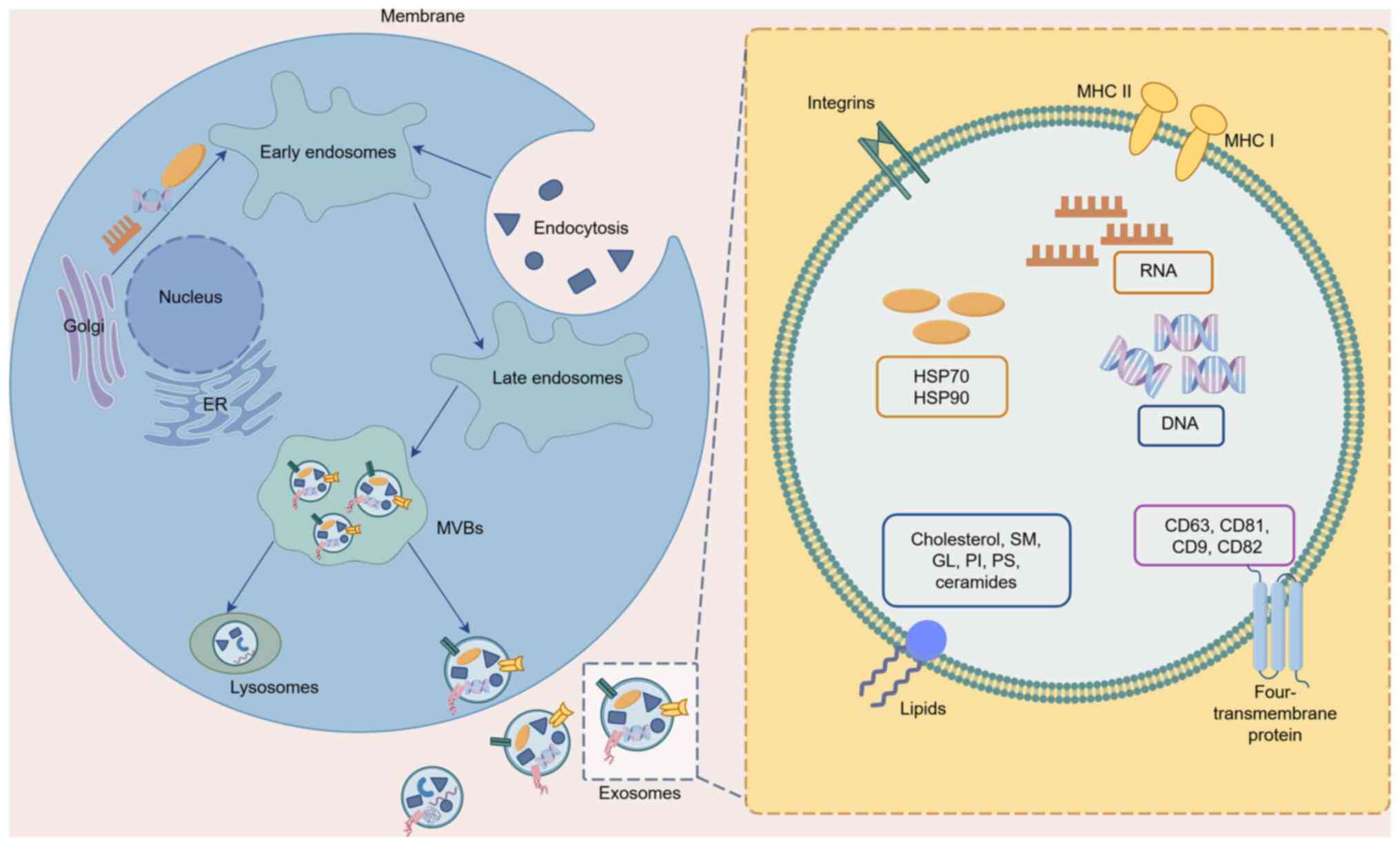

EXOs are extracellular vesicles (EVs) with a

diameter of 30–150 nm that are capable of transmitting complex

information between cells (17),

across distant tissues (18) and

between tumor and stromal compartments (19). They originate from a wide variety of

sources and are present in nearly all bodily fluids, and EXOs from

different origins exhibit distinct functions (20). MSC-derived EXOs (MSC-EXOs) share

numerous functional similarities with MSCs. However, compared with

MSCs, MSC-EXOs demonstrate enhanced safety, superior penetrability,

improved compatibility and higher stability when interacting with

tumor cells (21,22). In recent years, the role of MSC-EXOs

in the treatment of PC has been extensively investigated. For

instance, it has been reported that human umbilical cord MSC-EXOs

(hUC-MSC-EXOs) can promote the growth of pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma by transferring microRNA (miR/miRNA)-100-5p into the

PC tumor model (23). By contrast,

Xie et al (24) reported

opposing findings, demonstrating that hsa-miRNA-128-3p carried by

hUC-MSC-EXOs suppressed the proliferation, invasion and migration

of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells by targeting galectin-3.

These findings indicate that MSC-EXOs serve a dual role in PC. The

present article systematically elaborates on the dual

tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing mechanisms of MSC-EXOs in PC.

It also clarifies the potential factors influencing this duality

and provides direction for their application in targeted PC

therapy.

The International Society for Cell Therapy has

established the minimal defining criteria for MSCs: i) They must

exhibit plastic-adherence under standard culture conditions; ii)

they must express specific surface markers such as CD73, CD90 and

CD105; iii) they must possess the capacity to differentiate into

osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes in vitro; and iv)

they must lack expression of CD14, CD34, CD45, CD11b, CD79a, CD19

and human leukocyte antigen-DR (25,26).

MSCs can be isolated from a wide range of biological tissues,

including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta and

peripheral blood (27–29). In previous years, MSCs have

demonstrated notable potential in the treatment of PC; however,

several limitations have also been identified. For example, studies

have indicated that MSCs may increase the risk of tumorigenicity

and cell death (30,31). To address these concerns,

researchers have proposed using MSC-EXOs as an alternative

therapeutic approach for PC. These EXOs exhibit a number of

functions similar to those of MSCs, offer improved safety and

stability profiles and can serve as excellent carriers for

delivering antitumor drugs (32).

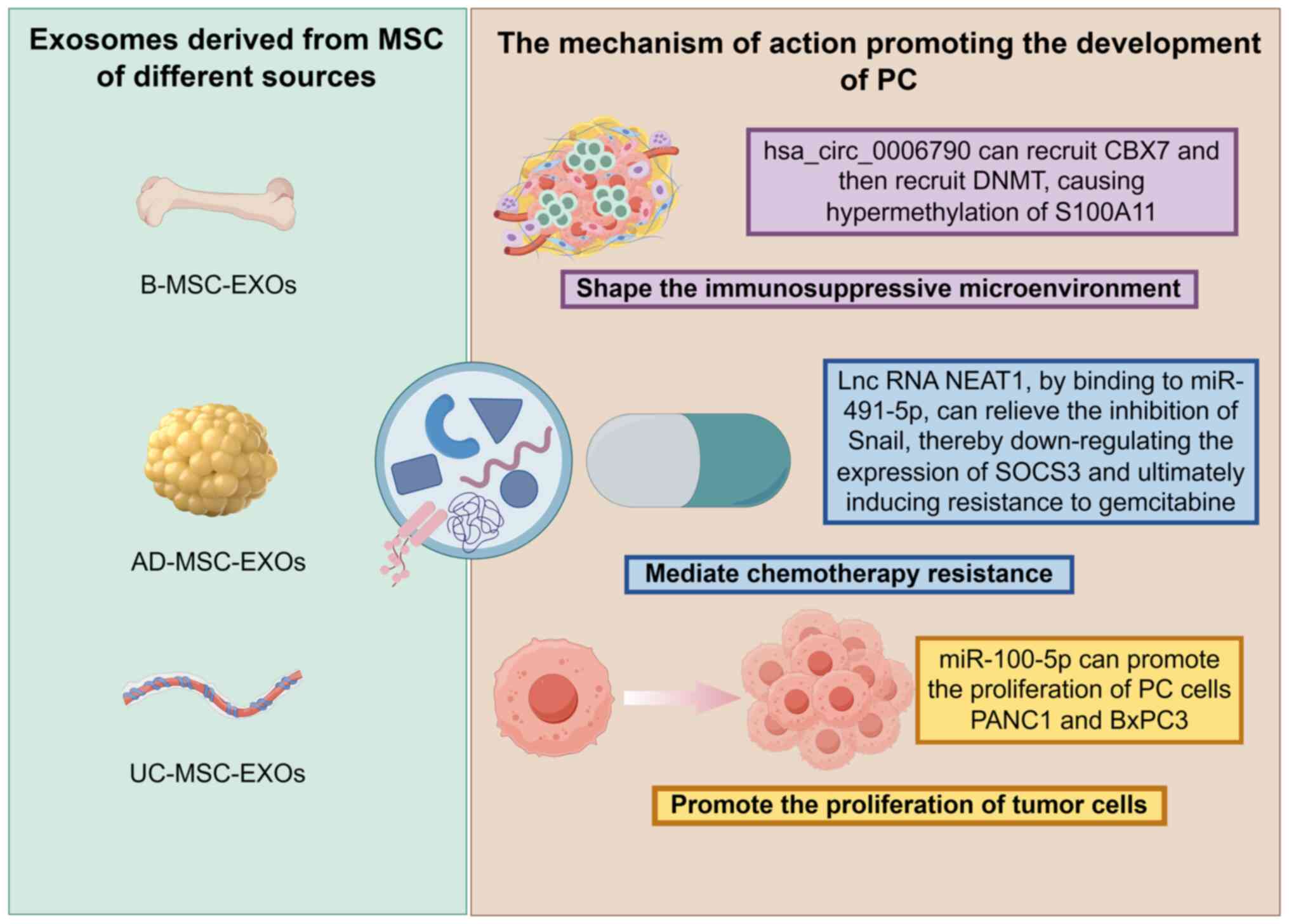

The tumor-promoting role of MSC-EXOs in PC has been

demonstrated in multiple studies (23,46,47).

For instance, B-MSC-EXOs, AD-MSC-EXOs and UC-MSC-EXOs can jointly

exert cancer-promoting effects through different mechanisms of

action (Fig. 2). The current

section will focus on elucidating the specific molecular mechanisms

and signaling pathways underlying their pro-tumorigenic effects,

including promoting tumor cell proliferation, shaping an

immunosuppressive microenvironment and mediating chemotherapy

resistance (Table I). By

systematically elaborating these mechanisms, the present study

aimed to provide researchers with a clear understanding of the

tumor-promoting functions of MSC-EXOs in PC and establish a

theoretical foundation for developing future exosome-targeted

therapeutic strategies.

MSC-EXOs can directly promote the proliferation of

PC cells, thereby exerting tumor-promoting effects. In the study by

Ding et al (23),

hUC-MSC-EXOs carrying miR-100-5p were demonstrated to promote the

proliferation of PC cells PANC1 and BxPC3 in both in vivo

and in vitro studies, consequently accelerating the growth

of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. This finding not only reveals

the key mechanism by which hUC-MSC-EXOs contribute to the

development and progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

through the transfer of miR-100-5p, but also provides new insights

for targeted intervention. Inhibiting miR-100-5p may represent a

potential therapeutic strategy to block EXO-mediated

pro-tumorigenic effects, thereby opening new avenues for precision

therapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

MSC-EXOs can participate in shaping the

immunosuppressive microenvironment of PC through complex

mechanisms, thereby providing favorable conditions for tumor

initiation and progression. For example, Gao et al (46) found that bone marrow MSC-EXOs

(B-MSC-EXOs) carrying hsa_circ_0006790 can recruit chromobox

protein homolog 7, which subsequently recruits DNA

methyltransferases, leading to hypermethylation of the promoter

region of the downstream target gene S100A11 and resulting in its

downregulation. As a key molecule involved in immunoregulation, the

decreased expression of S100A11 ultimately induces immune escape in

PC cells. This study by Gao et al (46) not only reveals the specific

mechanism by which B-MSC-EXOs contribute to the formation of the

immunosuppressive microenvironment in PC but also provides a

potential target for developing novel immunotherapy strategies

targeting the exosomal signaling axis.

MSC-EXOs can participate in mediating chemotherapy

resistance in PC. For example, a study showed that human adipose

MSC-EXOs (hAD-MSC-EXOs) are enriched with the lncRNA NEAT1, which

can competitively bind to miR-491-5p, thereby relieving its

inhibition of the transcription factor Snail. This subsequently

leads to downregulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3

(SOCS3) expression, ultimately inducing resistance to gemcitabine

in PC cells (47). This mechanism

highlights the critical role of exosome-carried lncRNA in mediating

chemotherapy resistance, not only providing a new molecular

perspective for understanding drug resistance in PC but also

offering potential therapeutic strategies for reversing resistance,

such as targeting the NEAT1/miR-491-5p/Snail/SOCS3 signaling axis

to reduce chemoresistance.

In conclusion, although MSC-EXOs derived from

different tissues such as umbilical cord, bone marrow and adipose

can promote the progression of PC through multiple mechanisms,

related research is still relatively limited, and more experimental

evidence is needed to verify the specific cancer-promoting

mechanisms. In addition, apart from gemcitabine, there are

currently numerous drugs used to inhibit the development of PC.

Therefore, whether hAD-MSC-EXOs still exhibit cancer-promoting

effects when used in conjuction with other anticancer drugs remains

to be elucidated. In addition, whether MSC-EXOs derived from the

same tissue only serve a promoting role in PC also remains to be

elucidated. Through in-depth sorting and analysis, a more complex

fact has been demonstrated: Even MSC-EXOs derived from the same

tissue exhibit a dual role in PC and may either promote tumor

development or inhibit its progression.

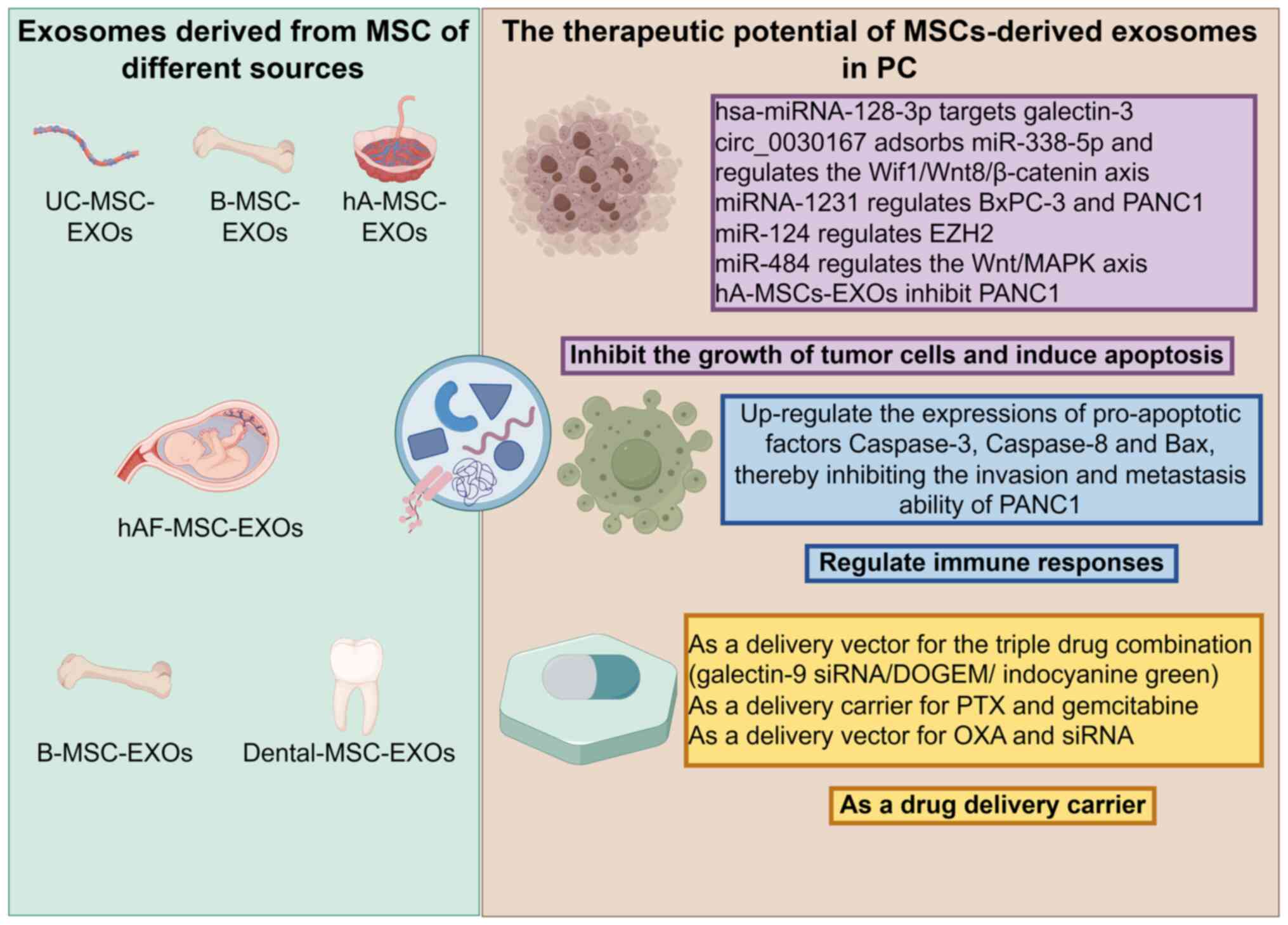

Although MSC-EXOs can promote the initiation and

progression of PC through various mechanisms, current research

focuses more on their tumor-suppressive roles. For instance,

UC-MSC-EXOs, B-MSC-EXOs, hA-MSC-EXOs, hAF-MSC-EXOs and

Dental-MSC-EXOs can jointly exert anti-cancer effects through

different mechanisms of action (Fig.

3). In fact, owing to their notable immunomodulatory

capabilities and tumor-homing properties, MSC-EXOs exhibit

multifaceted functions in tumor suppression: On the one hand, they

can directly inhibit the proliferation of PC cells and induce

apoptosis; on the other hand, they can indirectly exert antitumor

effects by modulating immune responses. Furthermore, due to their

high biocompatibility, low immunogenicity and efficient targeted

delivery capacity, MSC-EXOs serve as a highly promising drug

delivery system and are widely used for loading antitumor agents,

thereby further enhancing their value in suppressing PC (Table II) (48,49).

Therefore, despite reports indicating that MSC-EXOs may promote the

growth and development of PC, their functions in tumor suppression

remain more comprehensive and hold greater translational

potential.

MSC-EXOs exert notable tumor-suppressive effects by

inhibiting tumor cell growth and inducing apoptosis. Multiple

studies support this conclusion through various mechanisms. For

instance, hsa-miRNA-128-3p in hUC-MSC-EXOs can effectively inhibit

the proliferation, invasion and migration of PC PANC1 cells by

targeting galectin-3 (24).

Meanwhile, circ_0030167 from human (h)B-MSC-EXOs suppresses the

proliferation, invasion and metastasis of PC cells by sponging

miR-338-5p and regulating the Wnt inhibitory factor

1/Wnt8/β-catenin axis (50).

Additionally, miRNA-1231 from B-MSC-EXOs negatively regulates the

proliferation, migration, invasion and matrix adhesion of both

BxPC-3 and PANC1 cells (51). Xu

et al (52) demonstrated

that B-MSC-EXOs carrying miR-124 inhibit proliferation, invasion

and metastasis, while promoting apoptosis in AsPC1 and PANC1 cells

by modulating enhancer of zeste homolog 2 expression. Another study

indicated that miR-484, carried by hB-MSC-EXOs, suppresses

proliferation and migration and induces apoptosis in PC cells via

regulation of the Wnt/MAPK axis (53). Furthermore, human amniotic MSC-EXOs

inhibit the proliferation of PANC1 cells by downregulating the

expression of Sugen kinase 269, E-cadherin, vimentin and the Snail

transcription factor (54), a

finding further supported by studies from Safari and Dadvar

(55) and Safari et al

(56). Collectively, these findings

demonstrate that MSC-EXOs inhibit PC cell proliferation and promote

apoptosis through multiple molecular mechanisms, serving a crucial

role in suppressing PC progression.

MSC-EXOs can exert antitumor effects by modulating

immune responses. For example, a study by Chen et al

(9) demonstrated that human

amniotic fluid MSC-EXOs (hAF-MSC-EXOs) markedly upregulate the

expression of pro-apoptotic factors caspase-3, caspase-8 and Bax,

thereby inhibiting the invasion and metastatic capabilities of

PANC1 cells. This finding suggests that hAF-MSC-EXOs may enhance

immune effector mechanisms by upregulating pro-apoptotic factors,

consequently suppressing the progression of PC.

MSC-EXOs are regarded as a highly promising drug

delivery vehicle for anti-PC therapy due to their excellent

biocompatibility, low immunogenicity and inherent targeting

capability. A study has shown that B-MSC-EXOs can serve as carriers

for a triple-drug combination [galectin-9 small interfering

(si)RNA/dodecyloxybenzyl gemcitabine/indocyanine green],

demonstrating favorable tumor-targeting ability and pH-responsive

release characteristics both in vivo and in vitro,

notably enhancing the anti-PC efficacy (48). Furthermore, B-MSC-EXOs, as delivery

vehicles for paclitaxel and gemcitabine, effectively overcome

chemotherapy resistance in PC owing to their superior homing and

penetration capabilities during delivery (49). Zhou et al (57) developed a dual-delivery biosystem

using B-MSC-EXOs capable of co-loading oxaliplatin and siRNA. This

system not only elicits an antitumor immune response by inhibiting

tumor-associated macrophage polarization, promoting T lymphocyte

recruitment and downregulating regulatory T cell activity, but also

exhibits higher stability and lower side effects compared with

conventional synthetic carriers. An in vitro study by

Klimova et al (58) found

that EXOs derived from human dental pulp MSCs can act as carriers

for gemcitabine, significantly inhibiting the growth of PC cells.

In summary, the multiple advantages demonstrated by MSC-EXOs in

drug delivery indicate their potential as an efficient and safe

nanoscale platform for the treatment of PC.

Over time, genetic engineering has evolved into a

pivotal approach for treating various diseases, including

hematological disorders, genetic conditions, and cancers (59–61).

Particularly in the field of oncology, continuous technological

advancements and expanding applications have notably enhanced the

efficacy and safety of genetic engineering-based therapies,

demonstrating broad prospects for clinical application. MSC-EXOs

have garnered considerable attention in the treatment of PC due to

their unique biocompatibility, low immunogenicity and targeted

delivery capabilities. However, natural EXOs face limitations such

as insufficient targeting specificity, limited efficacy of their

cargo and rapid clearance, which substantially restrict their

clinical translation and therapeutic effectiveness. Consequently,

combining them with genetic engineering strategies can markedly

enhance their tumor-targeting ability, treatment specificity and

immunomodulatory functions in PC.

PC CAFs serve a critical role in the initiation and

progression of PC. Targeted reprogramming of CAFs may represent a

promising therapeutic strategy for PC. Zhou et al (62) employed a genetic engineering

approach to endogenously modify B-MSC-EXOs, enabling surface

display of integrin α5 targeting peptides and concomitant

overexpression of miR-148a-3p, thereby achieving precise

reprogramming of CAFs and providing new insights for clinical

translation of this strategy. On the other hand, Buocikova et

al (63) genetically engineered

EXOs from placental MSCs to express the yeast cytosine

deaminase::uracil phosphoribosyltransferase fusion enzyme. In a

model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, this approach

demonstrated potent cytotoxicity-reducing effects. Therefore, it

offers a promising cell-free therapeutic strategy for PC. Although

genetically engineered MSC-EXOs are considered a promising strategy

for cancer treatment, their current application in PC remains in

its early stages and requires further in-depth research to advance

their development. The development of more efficient and safer

engineered exosome-based therapeutic strategies remains a notable

challenge in the current treatment of PC.

MSC-EXOs exhibit a dual role in PC, a phenomenon

that warrants in-depth consideration. The underlying mechanisms are

likely closely associated with the following factors. Firstly, the

functional properties of EXOs are notably influenced by their

cellular origin. Although EXOs derived from different sources of

MSCs share common characteristics, such as high self-renewal

capacity, multipotent differentiation potential, immunomodulatory

activity, pro-angiogenic effects and tumor-homing ability (64–74)

(Fig. 4), the specific molecules

present on their surface and their cargo compositions may vary

considerably, potentially leading to distinct functional

orientations (75–79) (Table

III). MSC-EXOs from different tissue sources have demonstrated

a dual role in PC, which has been discussed in the present review.

On the other hand, the stage of PC progression may also affect the

functional outcomes of EXOs. For instance, early-stage PC may

respond more favorably to therapy with MSC-EXOs compared with

advanced-stage disease; however, this hypothesis still lacks robust

experimental evidence and thus represents a critical question that

urgently requires validation in future research. In addition, the

differences in experimental design within this research field are

another reason for the contradictions among different research

results. Specifically, the differences in the extraction and

identification methods of EXOs, cell co-culture systems and animal

models (such as mouse strains, quantities and tumor-bearing sites)

may all introduce notable heterogeneity, thereby affecting the

comparability and repeatability of research conclusions.

In summary, MSC-EXOs exhibit a notable dual role in

PC. The present review has systematically discussed their specific

molecular mechanisms and functional characteristics in PC, and

summarized the latest research advances in engineered modification

of MSC-EXOs. In-depth elucidation of the key molecules, proteins

and signaling pathways involved will provide new research

directions and intervention strategies for the treatment of PC.

Despite the considerable tumor-suppressive potential

of MSC-EXOs in PC, several unresolved issues and challenges remain.

First, the techniques for isolating and extracting MSC-EXOs are

still inadequate. Although multiple methods have been developed for

exosome isolation and extraction, such as ultracentrifugation

(80,81), ultrafiltration (82–84),

flushing separation (85),

precipitation (86–88), immunoaffinity capture (89–91),

microfluidics (92–95) and mass spectrometry (96), each of these approaches has its own

limitations. There is currently a lack of a simple, efficient,

cost-effective and standardized extraction protocol suitable for

clinical application. Second, research on and preparation of

MSC-EXOs lack unified standards. No authoritative institutions have

yet established clear guidelines for their isolation, preparation,

characterization and functional evaluation. Third, large-scale

production, storage and transportation systems remain

underdeveloped. Systematic research and solutions are still needed

regarding large-scale preparation, long-term stable storage methods

and potential loss of activity and integrity during transportation.

Fourth, evidence for clinical translation is insufficient. Most

current studies are limited to animal experiments; future research

should focus on clinical trials to validate the safety and efficacy

of these EXOs in human applications. Fifth, the immunogenicity

risks brought about by the engineering modification of MSC-EXOs

need to be systematically evaluated. For example, whether the

natural low immunogenicity advantage of MSC-EXOs will be altered

after engineering. Or, whether it may trigger an immune response in

the body, especially in the context of repeated administration for

PC, which would be a core issue regarding treatment safety. Sixth,

the dense fibrotic matrix of PC may severely impede the penetration

ability of EXOs, and their pharmacokinetic performance in this

environment requires further research and confirmation. Finally,

there is a lack of horizontal efficacy comparisons among various

treatment methods for PC. For instance, compared with traditional

nanoparticles (such as liposomes) that have entered clinical

application, MSC-EXOs may have inherent advantages in active

targeting and biocompatibility, but they are slightly inferior in

drug loading capacity and the maturity of production processes

(97). However, future research

should prospectively explore strategies for combining the two to

achieve synergistic therapeutic effects.

Although the present article systematically expounds

the research progress of MSC-EXOs in PC, there are still certain

limitations. Firstly, due to the rapid development of research in

this field, this article may not be able to cover all the latest

released research achievements. Secondly, the discussion on the

mechanism of MSC-EXOs in promoting cancer still needs to be further

clarified. In addition, the analysis of the potential and

challenges of EXOs derived from engineered MSCs in this field needs

to be strengthened. Looking to the future, first of all,

researchers should focus on developing a simple, efficient and

low-cost standardized extraction scheme for the separation and

extraction of EXOs. Secondly, more in-depth exploration and

research should be performed on the role of MSC-EXOs in PC to

address the potential loss issues that may arise during their

large-scale production, storage and transportation. In addition, a

systematic safety assessment of the immunogenicity risk and in

vivo pharmacokinetic behavior of engineered modified EXOs is

necessary, which is a prerequisite for their clinical

transformation. Another important task lies in performing a

horizontal efficacy comparison between exosome therapy and other

treatment methods, with the aim of providing the optimal treatment

strategy for patients with PC. Finally, accelerating the

transformation of MSC-EXOs from basic research to clinical practice

makes it possible for them to become an important component of the

comprehensive treatment system for PC.

MSC-EXOs serve as highly plastic messengers in PC,

where their role in promoting or suppressing tumor progression is

not fixed but rather determined by their specific surface molecules

and cargo contents, which are closely associated with the diverse

origins of MSCs. Future research should focus on transforming

MSC-EXOs from a ‘double-edged sword’ into a precise weapon against

PC. The primary task is to deeply explore its specific active

ingredients and their precise regulatory mechanisms in PC and, on

this basis, strategies for engineering and modifying MSC-EXOs

should be established. At the same time, establishing standardized,

repeatable, low-cost yet high-purity separation and purification

technologies is the core step for it to move towards clinical

application. In addition, it is important to actively explore the

combined application of EXOs therapy and existing treatment

methods. Only through in-depth exploration at multiple levels can

this promising treatment method be advanced from the laboratory to

clinical practice, bringing new treatment options for patients with

PC.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

HZ contributed to the conception and overall design

of the study. HZ drafted the manuscript and prepared the figures

and tables. XS reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication was not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Klein AP: Pancreatic cancer epidemiology:

understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat

Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:493–502. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Park W, Chawla A and O'Reilly EM:

Pancreatic cancer: A review. JAMA. 326:851–862. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kleeff J, Korc M, Apte M, La Vecchia C,

Johnson CD, Biankin AV, Neale RE, Tempero M, Tuveson DA, Hruban RH

and Neoptolemos JP: Pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

2:160222016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Halbrook CJ, Lyssiotis CA, Pasca di

Magliano M and Maitra A: Pancreatic cancer: Advances and

challenges. Cell. 186:1729–1754. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Klatte DCF, Wallace MB, Löhr M, Bruno MJ

and van Leerdam ME: Hereditary pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res

Clin Gastroenterol. 58–59. 1017832022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wood LD, Canto MI, Jaffee EM and Simeone

DM: Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and

treatment. Gastroenterology. 163:386–402.e1. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tsai CC, Su PF, Huang YF, Yew TL and Hung

SC: Oct4 and Nanog directly regulate Dnmt1 to maintain self-renewal

and undifferentiated state in mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell.

47:169–182. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chen YC, Lan YW, Huang SM, Yen CC, Chen W,

Wu WJ, Staniczek T, Chong KY and Chen CM: Human amniotic fluid

mesenchymal stem cells attenuate pancreatic cancer cell

proliferation and tumor growth in an orthotopic xenograft mouse

model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 13:2352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kabashima-Niibe A, Higuchi H, Takaishi H,

Masugi Y, Matsuzaki Y, Mabuchi Y, Funakoshi S, Adachi M, Hamamoto

Y, Kawachi S, et al: Mesenchymal stem cells regulate

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor progression of

pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 104:157–164. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Beckermann BM, Kallifatidis G, Groth A,

Frommhold D, Apel A, Mattern J, Salnikov AV, Moldenhauer G, Wagner

W, Diehlmann A, et al: VEGF expression by mesenchymal stem cells

contributes to angiogenesis in pancreatic carcinoma. Br J Cancer.

99:622–631. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Saito K, Sakaguchi M, Maruyama S, Iioka H,

Putranto EW, Sumardika IW, Tomonobu N, Kawasaki T, Homma K and

Kondo E: Stromal mesenchymal stem cells facilitate pancreatic

cancer progression by regulating specific secretory molecules

through mutual cellular interaction. J Cancer. 9:2916–2929. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Miyazaki Y, Oda T, Inagaki Y, Kushige H,

Saito Y, Mori N, Takayama Y, Kumagai Y, Mitsuyama T and Kida YS:

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into

heterogeneous cancer-associated fibroblasts in a stroma-rich

xenograft model. Sci Rep. 11:46902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mohr A, Albarenque SM, Deedigan L, Yu R,

Reidy M, Fulda S and Zwacka RM: Targeting of XIAP combined with

systemic mesenchymal stem cell-mediated delivery of sTRAIL ligand

inhibits metastatic growth of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Stem

Cells. 28:2109–2120. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao C, Pu Y, Zhang H, Hu X, Zhang R, He

S, Zhao Q and Mu B: IL10-modified human mesenchymal stem cells

inhibit pancreatic cancer growth through angiogenesis inhibition. J

Cancer. 11:5345–5352. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Keshtkar S, Azarpira N and Ghahremani MH:

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: Novel

frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 9:632018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhou J, Tan X, Tan Y, Li Q, Ma J and Wang

G: Mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes in cancer progression,

metastasis and drug delivery: A comprehensive review. J Cancer.

9:3129–3137. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Costa-Silva B, Aiello NM, Ocean AJ, Singh

S, Zhang H, Thakur BK, Becker A, Hoshino A, Mark MT, Molina H, et

al: Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche

formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol. 17:816–826. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Han S, Gonzalo DH, Feely M, Rinaldi C,

Belsare S, Zhai H, Kalra K, Gerber MH, Forsmark CE and Hughes SJ:

Stroma-derived extracellular vesicles deliver tumor-suppressive

miRNAs to pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 9:5764–5777. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, Fabijanic K,

Li Z, Chen H, Mark MT, Molina H, Martin AB, Bojmar L, et al:

Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of

extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation.

Nat Cell Biol. 20:332–343. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zagrean AM, Hermann DM, Opris I, Zagrean L

and Popa-Wagner A: Multicellular crosstalk between exosomes and the

neurovascular unit after cerebral ischemia. therapeutic

implications. Front Neurosci. 12:8112018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee JR, Park BW, Kim J, Choo YW, Kim HY,

Yoon JK, Kim H, Hwang JW, Kang M, Kwon SP, et al: Nanovesicles

derived from iron oxide nanoparticles-incorporated mesenchymal stem

cells for cardiac repair. Sci Adv. 6:eaaz09522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ding Y, Mei W, Zheng Z, Cao F, Liang K,

Jia Y, Wang Y, Liu D, Li J and Li F: Exosomes secreted from human

umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promote pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma growth by transferring miR-100-5p. Tissue Cell.

73:1016232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xie X, Ji J, Chen X, Xu W, Chen H, Zhu S,

Wu J, Wu Y, Sun Y, Sai W, et al: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal

stem cell-derived exosomes carrying hsa-miRNA-128-3p suppress

pancreatic ductal cell carcinoma by inhibiting Galectin-3. Clin

Transl Oncol. 24:517–531. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I,

Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A,

Prockop Dj and Horwitz E: Minimal criteria for defining multipotent

mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular

Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 8:315–317. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lv FJ, Tuan RS, Cheung KM and Leung VY:

Concise review: The surface markers and identity of human

mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 32:1408–1419. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Teixeira FG, Panchalingam KM, Anjo SI,

Manadas B, Pereira R, Sousa N, Salgado AJ and Behie LA: Do

hypoxia/normoxia culturing conditions change the neuroregulatory

profile of Wharton Jelly mesenchymal stem cell secretome? Stem Cell

Res Ther. 6:1332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kisiel AH, McDuffee LA, Masaoud E, Bailey

TR, Esparza Gonzalez BP and Nino-Fong R: Isolation,

characterization, and in vitro proliferation of canine mesenchymal

stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, muscle, and

periosteum. Am J Vet Res. 73:1305–1317. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Murphy MB, Moncivais K and Caplan AI:

Mesenchymal stem cells: Environmentally responsive therapeutics for

regenerative medicine. Exp Mol Med. 45:e542013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Trounson A and McDonald C: Stem cell

therapies in clinical trials: Progress and challenges. Cell Stem

Cell. 17:11–22. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

He Z, Wang J, Zhu C, Xu J, Chen P, Jiang

X, Chen Y, Jiang J and Sun C: Exosome-derived FGD5-AS1 promotes

tumor-associated macrophage M2 polarization-mediated pancreatic

cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. Cancer Lett.

548:2157512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cai J, Wu J, Wang J, Li Y, Hu X, Luo S and

Xiang D: Extracellular vesicles derived from different sources of

mesenchymal stem cells: Therapeutic effects and translational

potential. Cell Biosci. 10:692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Singh S, Dansby C, Agarwal D, Bhat PD,

Dubey PK and Krishnamurthy P: Exosomes: Methods for isolation and

characterization in biological samples. Methods Mol Biol.

2835:181–213. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ and Emr SD: The

ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell. 21:77–91. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tschuschke M, Kocherova I, Bryja A,

Mozdziak P, Angelova Volponi A, Janowicz K, Sibiak R,

Piotrowska-Kempisty H, Iżycki D, Bukowska D, et al: Inclusion

biogenesis, methods of isolation and clinical application of human

cellular exosomes. J Clin Med. 9:4362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gurung S, Perocheau D, Touramanidou L and

Baruteau J: The exosome journey: From biogenesis to uptake and

intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal. 19:472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Joo HS, Suh JH, Lee HJ, Bang ES and Lee

JM: Current knowledge and future perspectives on mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomes as a new therapeutic agent. Int J Mol Sci.

21:7272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kowal J, Tkach M and Théry C: Biogenesis

and secretion of exosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 29:116–125. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wortzel I, Dror S, Kenific CM and Lyden D:

Exosome-mediated metastasis: Communication from a distance. Dev

Cell. 49:347–360. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Doyle LM and Wang MZ: Overview of

extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and

methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells. 8:7272019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yang Y, Hong Y, Cho E, Kim GB and Kim IS:

Extracellular vesicles as a platform for membrane-associated

therapeutic protein delivery. J Extracell Vesicles. 7:14401312018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kugeratski FG, Hodge K, Lilla S, McAndrews

KM, Zhou X, Hwang RF, Zanivan S and Kalluri R: Quantitative

proteomics identifies the core proteome of exosomes with syntenin-1

as the highest abundant protein and a putative universal biomarker.

Nat Cell Biol. 23:631–641. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hánělová K, Raudenská M, Masařík M and

Balvan J: Protein cargo in extracellular vesicles as the key

mediator in the progression of cancer. Cell Commun Signal.

22:252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Choi DS, Kim DK, Kim YK and Gho YS:

Proteomics, transcriptomics and lipidomics of exosomes and

ectosomes. Proteomics. 13:1554–1571. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand

M, Lee JJ and Lötvall JO: Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and

microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells.

Nat Cell Biol. 9:654–659. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gao G, Wang L and Li C: Circ_0006790

carried by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes

regulates S100A11 DNA methylation through binding to CBX7 in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 12:1934–1959.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wu R, Su Z, Zhao L, Pei R, Ding Y, Li D,

Zhu S, Xu L, Zhao W and Zhou W: Extracellular vesicle-loaded

oncogenic lncRNA NEAT1 from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells

confers gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer via

miR-491-5p/Snail/SOCS3 axis. Stem Cells Int. 2023:65105712023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang R, Zhang Y, Hao F, Su Z, Duan X and

Song X: Exosome-mediated triple drug delivery enhances apoptosis in

pancreatic cancer cells. Apoptosis. 30:1893–1911. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhou Y, Zhou W, Chen X, Wang Q, Li C, Chen

Q, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Ding X and Jiang C: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells-derived exosomes for penetrating and targeted chemotherapy of

pancreatic cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 10:1563–1575. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yao X, Mao Y, Wu D, Zhu Y, Lu J, Huang Y,

Guo Y, Wang Z, Zhu S, Li X and Lu Y: Exosomal circ_0030167 derived

from BM-MSCs inhibits the invasion, migration, proliferation and

stemness of pancreatic cancer cells by sponging miR-338-5p and

targeting the Wif1/Wnt8/β-catenin axis. Cancer Lett. 512:38–50.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shang S, Wang J, Chen S, Tian R, Zeng H,

Wang L, Xia M, Zhu H and Zuo C: Exosomal miRNA-1231 derived from

bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibits the activity of

pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 8:7728–7740. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xu Y, Liu N, Wei Y, Zhou D, Lin R, Wang X

and Shi B: Anticancer effects of miR-124 delivered by BM-MSC

derived exosomes on cell proliferation, epithelial mesenchymal

transition, and chemotherapy sensitivity of pancreatic cancer

cells. Aging (Albany NY). 12:19660–19676. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lin T, Pu X, Zhou S, Huang Z, Chen Q,

Zhang Y, Mao Q, Liang Y and Ding G: Identification of exosomal

miR-484 role in reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism in

pancreatic cancer through Wnt/MAPK axis control. Pharmacol Res.

197:1069802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Alidoust Saharkhiz Lahiji M and Safari F:

Potential therapeutic effects of hAMSCs secretome on Panc1

pancreatic cancer cells through downregulation of SgK269,

E-cadherin, vimentin, and snail expression. Biologicals. 76:24–30.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Safari F and Dadvar F: In vitro evaluation

of autophagy and cell death induction in Panc1 pancreatic cancer by

secretome of hAMSCs through downregulation of p-AKT/p-mTOR and

upregulation of p-AMPK/ULK1 signal transduction pathways. Tissue

Cell. 84:1021602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Safari F, Shafiee Nejad N and Aghaei Nejad

A: The inhibition of Panc1 cancer cells invasion by hAMSCs

secretome through suppression of tyrosine phosphorylation of SGK223

(at Y411 site), c-Src (at Y416, Y530 sites), AKT activity, and

JAK1/Stat3 signaling. Med Oncol. 39:282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhou W, Zhou Y, Chen X, Ning T, Chen H,

Guo Q, Zhang Y, Liu P, Zhang Y, Li C, et al: Pancreatic

cancer-targeting exosomes for enhancing immunotherapy and

reprogramming tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials. 268:1205462021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Klimova D, Jakubechova J, Altanerova U,

Nicodemou A, Styk J, Szemes T, Repiska V and Altaner C:

Extracellular vesicles derived from dental mesenchymal stem/stromal

cells with gemcitabine as a cargo have an inhibitory effect on the

growth of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines in vitro. Mol Cell

Probes. 67:1018942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Hu X, Zhou W, Pi R, Zhao X and Wang W:

Genetically modified cancer vaccines: Current status and future

prospects. Med Res Rev. 42:1492–1517. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Dunbar CE, High KA, Joung JK, Kohn DB,

Ozawa K and Sadelain M: Gene therapy comes of age. Science.

359:eaan46722018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Doering CB, Archer D and Spencer HT:

Delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics by genetically engineered

hematopoietic stem cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 62:1204–1212. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhou P, Ding X, Du X, Wang L and Zhang Y:

Targeting reprogrammed cancer-associated fibroblasts with

engineered mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicles for

pancreatic cancer treatment. Biomater Res. 28:00502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Buocikova V, Altanerova U, Soltysova A,

Andrezal M, Vanova D, Jakubechova J, Cihova M, Burikova M, Urbanova

M, Juhasikova L, et al: Placental mesenchymal stem cells: A

promising platform for advancing gene therapy in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 190:1184282025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Amati E, Perbellini O, Rotta G, Bernardi

M, Chieregato K, Sella S, Rodeghiero F, Ruggeri M and Astori G:

High-throughput immunophenotypic characterization of bone marrow-

and cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells reveals common and

differentially expressed markers: Identification of

angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) as a marker differentially

expressed between adult and perinatal tissue sources. Stem Cell Res

Ther. 9:102018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhang J, Liu Y, Yin W and Hu X:

Adipose-derived stromal cells in regulation of hematopoiesis. Cell

Mol Biol Lett. 25:162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Xu T, Yu X, Yang Q, Liu X, Fang J and Dai

X: Autologous micro-fragmented adipose tissue as stem cell-based

natural scaffold for cartilage defect repair. Cell Transplant.

28:1709–1720. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Schäffler A and Büchler C: Concise review:

Adipose tissue-derived stromal cells-basic and clinical

implications for novel cell-based therapies. Stem Cells.

25:818–827. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kozlowska U, Krawczenko A, Futoma K, Jurek

T, Rorat M, Patrzalek D and Klimczak A: Similarities and

differences between mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells derived from

various human tissues. World J Stem Cells. 11:347–374. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Dubey NK, Mishra VK, Dubey R, Deng YH,

Tsai FC and Deng WP: Revisiting the advances in isolation,

characterization and secretome of adipose-derived stromal/stem

cells. Int J Mol Sci. 19:22002018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Fukuchi Y, Nakajima H, Sugiyama D, Hirose

I, Kitamura T and Tsuji K: Human placenta-derived cells have

mesenchymal stem/progenitor cell potential. Stem Cells. 22:649–658.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Oliveira MS and Barreto-Filho JB:

Placental-derived stem cells: Culture, differentiation and

challenges. World J Stem Cells. 7:769–775. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ulrich C, Abruzzese T, Maerz JK, Ruh M,

Amend B, Benz K, Rolauffs B, Abele H, Hart ML and Aicher WK: Human

placenta-derived CD146-positive mesenchymal stromal cells display a

distinct osteogenic differentiation potential. Stem Cells Dev.

24:1558–1569. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Li S, Huang KJ, Wu JC, Hu MS, Sanyal M, Hu

M, Longaker MT and Lorenz HP: Peripheral blood-derived mesenchymal

stem cells: Candidate cells responsible for healing critical-sized

calvarial bone defects. Stem Cells Transl Med. 4:359–368. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Cao C and Dong Y and Dong Y: Study on

culture and in vitro osteogenesis of blood-derived human

mesenchymal stem cells. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi.

19:642–647. 2005.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Tracy SA, Ahmed A, Tigges JC, Ericsson M,

Pal AK, Zurakowski D and Fauza DO: A comparison of clinically

relevant sources of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: Bone

marrow and amniotic fluid. J Pediatr Surg. 54:86–90. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang Z, He Z, Liang S, Yang Q, Cheng P and

Chen A: Comprehensive proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from

human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord mesenchymal

stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 11:5112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ji L, Bao L, Gu Z, Zhou Q, Liang Y, Zheng

Y, Xu Y, Zhang X and Feng X: Comparison of immunomodulatory

properties of exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells and dental pulp stem cells. Immunol Res. 67:432–442. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Katsuda T, Tsuchiya R, Kosaka N, Yoshioka

Y, Takagaki K, Oki K, Takeshita F, Sakai Y, Kuroda M and Ochiya T:

Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells secrete

functional neprilysin-bound exosomes. Sci Rep. 3:11972013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Pomatto M, Gai C, Negro F, Cedrino M,

Grange C, Ceccotti E, Togliatto G, Collino F, Tapparo M, Figliolini

F, et al: Differential therapeutic effect of extracellular vesicles

derived by bone marrow and adipose mesenchymal stem cells on wound

healing of diabetic ulcers and correlation to their cargoes. Int J

Mol Sci. 22:38512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Langevin SM, Kuhnell D, Orr-Asman MA,

Biesiada J, Zhang X, Medvedovic M and Thomas HE: Balancing yield,

purity and practicality: A modified differential

ultracentrifugation protocol for efficient isolation of small

extracellular vesicles from human serum. RNA Biol. 16:5–12. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Gardiner C, Di Vizio D, Sahoo S, Théry C,

Witwer KW, Wauben M and Hill AF: Techniques used for the isolation

and characterization of extracellular vesicles: Results of a

worldwide survey. J Extracell Vesicles. 5:329452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Van Deun J, Mestdagh P, Sormunen R,

Cocquyt V, Vermaelen K, Vandesompele J, Bracke M, De Wever O and

Hendrix A: The impact of disparate isolation methods for

extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J Extracell

Vesicles. 3:2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Lobb RJ, Becker M, Wen SW, Wong CS,

Wiegmans AP, Leimgruber A and Möller A: Optimized exosome isolation

protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J Extracell

Vesicles. 4:270312015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Bhattacharjee C and Singh M: Studies on

the applicability of artificial neural network (ANN) in continuous

stirred ultrafiltration. Chem Eng Technol. 25:1187–1192. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Cheng H, Fang H, Xu RD, Fu MQ, Chen L,

Song XY, Qian JY, Zou YZ, Ma JY and Ge JB: Development of a rinsing

separation method for exosome isolation and comparison to

conventional methods. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 23:5074–5083.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Soares Martins T, Catita J, Martins Rosa

I, AB da Cruz E, Silva O and Henriques AG: Exosome isolation from

distinct biofluids using precipitation and column-based approaches.

PLoS One. 13:e01988202018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Buschmann D, Kirchner B, Hermann S, Märte

M, Wurmser C, Brandes F, Kotschote S, Bonin M, Steinlein OK, Pfaffl

MW, et al: Evaluation of serum extracellular vesicle isolation

methods for profiling miRNAs by next-generation sequencing. J

Extracell Vesicles. 7:14813212018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Zhao L, Yu J, Wang J, Li H, Che J and Cao

B: Isolation and identification of miRNAs in exosomes derived from

serum of colon cancer patients. J Cancer. 8:1145–1152. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Popovic M, Mazzega E, Toffoletto B and De

Marco A: Isolation of anti-extra-cellular vesicle single-domain

antibodies by direct panning on vesicle-enriched fractions. Microb

Cell Fact. 17:62018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhu L, Sun HT, Wang S, Huang SL, Zheng Y,

Wang CQ, Hu BY, Qin W, Zou TT, Fu Y, et al: Isolation and

characterization of exosomes for cancer research. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Pei S, Sun W, Han Q, Wang H and Liang Q:

Bifunctional immunoaffinity magnetic nanoparticles for

high-efficiency separation of exosomes based on host-guest

interaction. Talanta. 272:1257902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Iliescu FS, Vrtačnik D, Neuzil P and

Iliescu C: Microfluidic technology for clinical applications of

exosomes. Micromachines (Basel). 10:3922019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zhang P, Zhou X, He M, Shang Y, Tetlow AL,

Godwin AK and Zeng Y: Ultrasensitive detection of circulating

exosomes with a 3D-nanopatterned microfluidic chip. Nat Biomed Eng.

3:438–451. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Hua X, Zhu Q, Liu Y, Zhou S, Huang P, Li Q

and Liu S: A double tangential flow filtration-based microfluidic

device for highly efficient separation and enrichment of exosomes.

Anal Chim Acta. 1258:3411602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Ding L, Liu X, Zhang Z, Liu LE, He S, Wu

Y, Effah CY, Yang R, Zhang A, Chen W, et al:

Magnetic-nanowaxberry-based microfluidic ExoSIC for affinity and

continuous separation of circulating exosomes towards cancer

diagnosis. Lab Chip. 23:1694–1702. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Abramowicz A, Marczak L, Wojakowska A,

Zapotoczny S, Whiteside TL, Widlak P and Pietrowska M:

Harmonization of exosome isolation from culture supernatants for

optimized proteomics analysis. PLoS One. 13:e02054962018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Iqbal Z, Rehman K, Mahmood A, Shabbir M,

Liang Y, Duan L and Zeng H: Exosome for mRNA delivery: Strategies

and therapeutic applications. J Nanobiotechnology. 22:3952024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|