Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common extracranial

solid tumor in children and accounts for 3–10% of cases of

childhood cancer mortality (1–3). The

prognosis markedly varies, with overall survival ranging from

>95% for low-risk patients to <40% for high-risk patients

(4). The treatment plan for NB is

mainly based on the degree of risk expected at the time of

diagnosis, with risk assessment including various factors, such as

age, International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS)

stage/International Neuroblastoma Risk Group stage (5,6), MYCN

amplification status, International Neuroblastoma Pathology

Classification (7), histological

category, grade of tumor differentiation, DNA ploidy and 11q

deletion (8). Among them, MYCN

amplification status (9) and

metastasis (10) are the key

reasons for treatment failure.

MYCN is a highly conserved human oncogene and

numerous studies have confirmed that MYCN gene status is associated

with various types of cancer, particularly NB (11,12),

and is key for the prediction of patient prognosis and guiding

treatment. Compared with in patients with NB without MYCN

amplification (MYCN−), those with MYCN amplification

(MYCN+) have been reported to have an increased

probability of metastasis (13).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) serve key roles in

the proliferation, differentiation and migration of malignant tumor

cells by competitively binding to microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) as

competitive endogenous RNAs and then regulating the expression of

target genes, and the differentiation and migration of malignant

tumor cells (14). Previous studies

have reported an association between MYCN and lncRNAs. For example,

the lncRNA AC142119.1 has been reported to be markedly upregulated

in MYCN+, advanced INSS and high-risk NB tissues, and is

associated with poor survival in patients with NB. Furthermore,

increased expression levels of AC142119.1 can enhance NB cell

proliferation in vitro and in vivo (15). High expression levels of the lncRNA

small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 (SNHG1) are associated with a poor

prognosis and MYCN status in NB. Downregulation of SNHG1 levels in

the MYCN+ NB cell line SK-N-BE2 have been shown to

result in the inhibition of cell proliferation and colony-forming

ability (16). In addition,

elevated levels of nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1

(NEAT1) expression in NB cells and tissues are associated with

advanced pathological stages and poor prognosis, whereas NEAT1

silencing inhibits NB proliferation in vivo.

Mechanistically, NEAT1 acts as a competitive sponge for miR-873-5p

and regulates MYCN and polypeptide

N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase I level (17). These studies suggest that lncRNAs

serve key roles in the progression of MYCN+ NB.

In the present study, bioinformatics analyses were

performed on different NB samples to identify the differentially

expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) that were associated with MYCN and

their functions were analyzed. CIBERSORT was used to identify

MYCN-regulated regulatory T cells (Tregs) and T follicular helper

cells (Tfhs). To identify the DElncRNAs associated with Tregs and

Tfhs, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was further computed

using the DElncRNA expression levels, and the proportions of Tregs

and Tfhs. On this basis, the lncRNA RP11-196G11.6 was selected. The

effects of miR-376a-3p and its downstream target genes mediated by

RP11-196G11.6 on the viability, migration and invasion of NB cells

were further verified. The aim of the present study was to

elucidate the specific mechanisms by which RP11-196G11.6 acts as a

tumor suppressor in NB, and to establish a potential novel target

for the diagnosis and treatment of NB.

Materials and methods

Clinical specimens and public

data

Public transcriptome-sequence data files from

patients with NB, comprising tumor samples (n=16) and disseminated

tumor cells (DTC) (n=42) [Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO); accession

no. GSE94035; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE94035]

-were downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra?term=SRP097735). The

National Center for Biotechnology Information SRA Tool FASTQ-dump

(https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools/wiki/02.-Installing-SRA-Toolkit)

was used to convert the SRA Run files to FASTQ format.

FASTX-Toolkit (version 0.0.13; http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) was used to

trim the raw reads of low-quality bases. The clean reads were

subsequently evaluated using FastQC (Version 0.12.0) (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/).

Reads alignment and differentially

expressed gene (DEG) analysis

The clean reads were aligned with the human GRch38

genome via ‘tophat2’ (Version 2.1.1), allowing four mismatches

(18). Several core bioinformatics

analyses, including DEG analysis, immune cell-type quantification

and principal component analysis (PCA), were implemented using the

R programming environment (Version 4.3.2; http://cran.r-project.org/). The unique mapped reads

were ultimately used to calculate the read number and the reads/kb

of exon per million fragments mapped (RPKM) for each gene. The RPKM

values were used to assess gene expression levels. ‘edgeR’ (Version

4.6.3) (19), a software tool

specifically designed to analyze the differential expression of

genes, was applied to screen the RNA-sequencing data for DEGs

(including lncRNA and mRNA). The results were analyzed according to

the following criteria: Fold change ≥2 or ≤0.5, and false discovery

rate (FDR) ≤0.05, to determine whether genes were differentially

expressed.

lncRNA prediction and direction

identification

A pipeline for lncRNA identification similar to that

described in a previous study was used to systematically understand

the lncRNA expression of NB tumor samples and DTC samples (20), which was constructed via Cufflinks

software (Version 2.2.1) (21). All

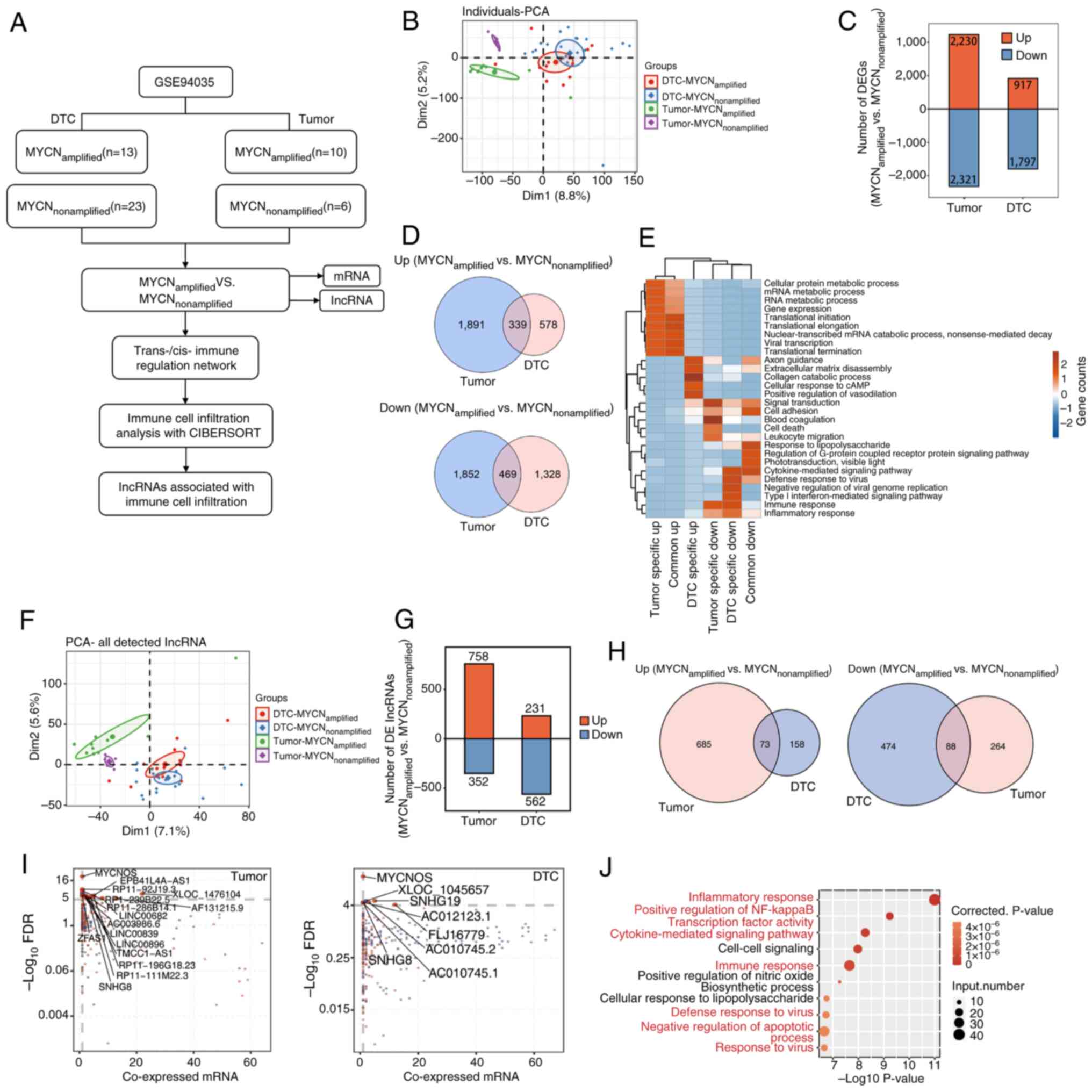

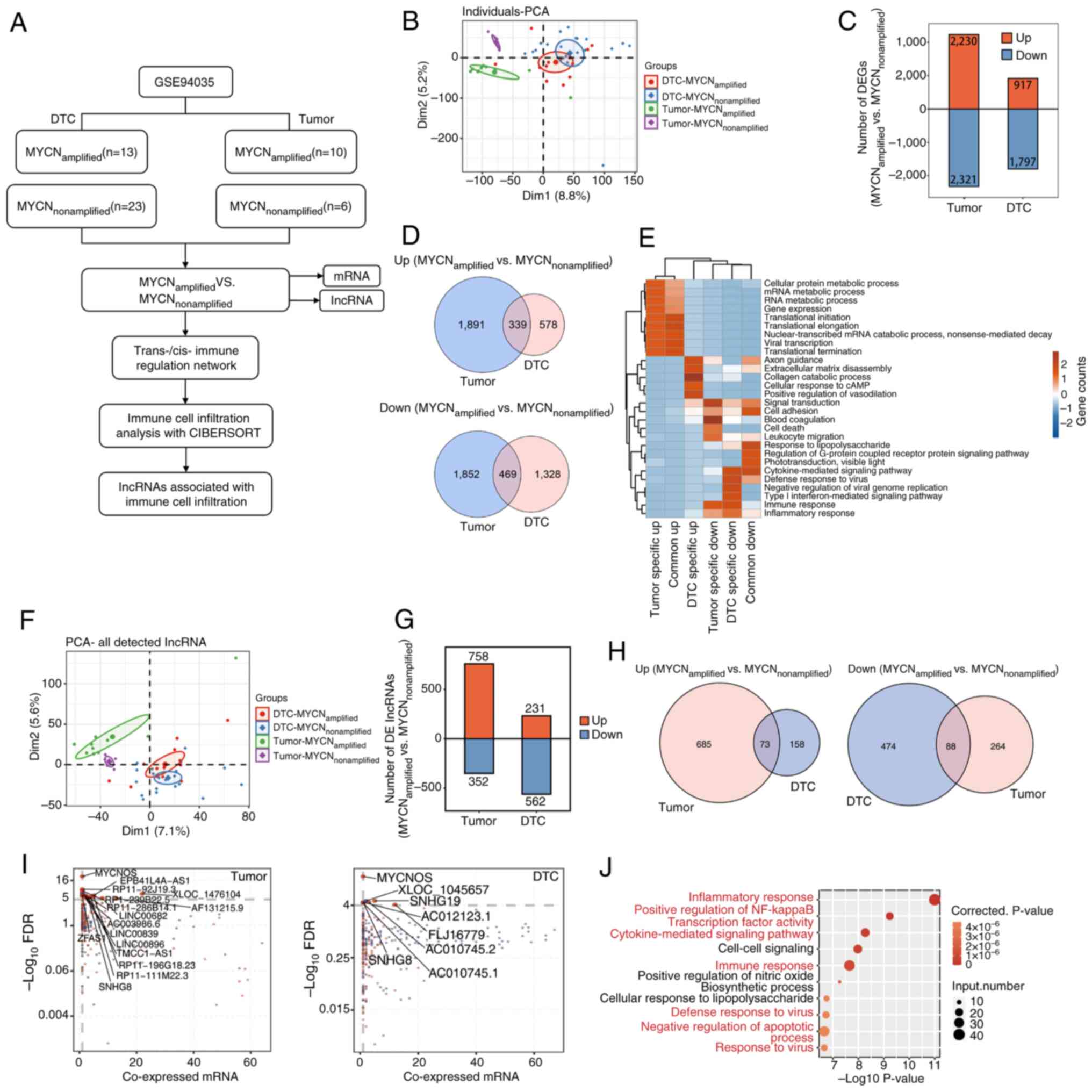

the steps of the pipeline are shown in Fig. 1A. Based on the NB GSE94035 dataset,

samples from the DTC group (MYCNamplified n=13,

MYCNnon-amplified n=23) and the tumor group

(MYCNamplified n=10, MYCNnon-amplified n=6)

were included. The edgeR software (Version 4.6.3) was used to

analyze the differential expression of mRNAs and lncRNAs between

DTCs and tumors. Then, using the immunedeconv package (Version

2.0.3) (22), a lncRNA

immunoregulatory network was constructed. Furthermore, the

infiltration levels of 22 immune cell subtypes were quantified

using CIBERSORT (Version 2020; http://cibersortx.stanford.edu/) and intergroup

differences were compared. Through integrated analysis, key lncRNAs

were identified among the DElncRNAs that not only participate in

immunoregulatory networks but also demonstrate significant

associations with specific immune cell infiltration levels.

Potential miRNAs interacting with the target lncRNA were predicted

using miRanda (https://cloud.oebiotech.cn/task/detail/array_miranda_plot/),

while the potential target genes binding to these miRNAs were

identified via miRDB (https://mirdb.org/).

| Figure 1.Analysis of DElncRNAs in tumor and

bone marrow metastatic tissues. (A) Schematic diagram of the

bioinformatics analysis process. (B) PCA between tumor and DTC

samples, and between MYCN amplification statuses. (C) Analysis of

DEGs between MYCN+ and MYCN− samples in tumor

and DTC samples. (D) Venn diagrams depicting commonly upregulated

and downregulated DEGs in the four groups of samples. (E) GO

enrichment analysis showing the GO terms that were most

significantly enriched in 808 DEGs. The color scale represents the

enrichment intensity of gene sets across different groups, based on

the number of genes enriched in each pathway and normalized to a

range of −2 to 2. (F) PCA of the lncRNAs among the DEGs. (G)

DElncRNA analysis between MYCN+ and MYCN−

samples in tumor and DTC samples. (H) Venn diagrams indicating

commonly upregulated and downregulated DElncRNAs in the four groups

of samples. (I) Weighted gene co-expression network analysis and

co-expression analysis. Scatter plots of DElncRNAs and their

co-expressed DEmRNAs in MYCN+ vs. MYCN−

samples across tumor and DTC cohorts. Red points denote upregulated

lncRNAs involved in co-expression pairs and blue points denote

downregulated lncRNAs. The straight lines represent correlations

between the two variables. Cutoffs of P≤0.01 and Pearson

coefficient >0.8 were applied to identify the co-expression

pairs. (J) Top 10 most enriched GO terms (biological processes) in

DEmRNAs co-expressed with the DElncRNAs; the highlighted terms in

red are associated with immune and inflammatory responses. lncRNA,

long non-coding RNA; PCA, principal component analysis; DTC,

disseminated tumor cell; DEG, differentially expressed gene; GO,

Gene Ontology; DElncRNA, differentially expressed lncRNA; DEmRNA,

differentially expressed mRNA; FDR, false discovery rate. |

Weighted gene co-expression network

analysis (WGCNA) and co-expression analysis

To fully understand gene expression patterns, WGCNA

(23) was used to cluster genes

with similar expression patterns and the default parameters were

used. All expressed genes were used as input data. The eigengenes

of each clustering module were regarded as the representative

expression pattern of the gene in each module. To explore the

regulatory mode between lncRNAs and their host mRNAs, Pearson's

rank correlation coefficients were computed, which were used to

divide their relationships into the following three categories: i)

Positively correlated; ii) negatively correlated; and iii)

non-correlated. Cutoffs of P≤0.01 and Pearson coefficient >0.8

were applied to identify the co-expression pairs.

Functional enrichment analysis

To determine the functional categories of the DEGs,

the KOBAS 2.0 server was used to identify the enriched Gene

Ontology (GO) terms (24). The

enrichment of each term was defined via a hypergeometric test and

the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR controlling procedure.

Cell-type quantification

The R (Version 4.3.2; http://cran.r-project.org/) package ‘immunedeconv

(Version 2.0.3)’ provides a unified interface for seven

deconvolution methods to estimate immune cell fractions, with the

EPIC and CIBERSORT methods applied in the present study.

MYCN-associated lncRNA-immune cell

infiltration network

The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to

assess the correlation between the expression levels of DElncRNAs

and the ratio of Tregs to Tfhs. lncRNA-cell pairs with Spearman

correlation coefficients of >0.6 (or <-0.6) and a

corresponding P-value (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected) of <0.01

were considered significantly correlated. A lncRNA-immune cell

infiltration network was constructed with Cytoscape (Version

3.10.4; http://cytoscape.org/).

PCA and Venn diagram

PCA was performed using the R package ‘factoextra’

(Version 1.0.7; http://cloud.r-project.org/package=factoextra) to

display the clusters of samples with the first two components.

After the reads of each gene in the samples were standardized by

tags/million, the internal script was used for the visualization of

next-generation sequencing data and genome annotations. The Venn

diagram was generated using Venny (Version 2.1; http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/;) with gene

lists from MYCN+ and MYCN− tumor and DTC

samples inputted for comparative analysis.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

(FISH)

Between March and May 2025, MYCN+ and

MYCN− tumor samples (n=5/group) were collected

retrospectively from the Department of Pathology, Guizhou

Provincial People's Hospital (Guiyang, China). The cohort comprised

10 children (7 male and 3 female patients) aged between 5 months

and 12 years old, with an mean age of 4.58 years. The inclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Pathological confirmation of NB

following surgery; ii) availability of adequate resected tissue

specimens; iii) genetic testing to determine MYCN amplification

status. Patients failing to meet any of these criteria were

excluded. Following resection, all tumor tissues were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h, followed by paraffin

embedding. Then, tissue sections (6 µm) were mounted on positively

charged slides and stored at 4°C until use. The expression levels

of RP11-196G11.6 and U6 in tumor samples were detected using a

customized RP11-196G11.6 FISH detection kit [cat. no. Mk1257-H

(CY3); Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.]; all reagents

including antibodies used prior to DAPI staining were sourced from

this kit. Briefly, after deparaffinization and rehydration of the

slides, target nucleic acids were exposed by digestion with pepsin

(3% citric acid-diluted) for 20 min at 37°C. This was followed by

washes with PBS and distilled water. Post-fixation was carried out

using 1% paraformaldehyde containing 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate for

10 min at room temperature. Pre-hybridization was performed at 42°C

for 4 h in a humidified chamber containing 20% glycerol. A 20-µl

hybridization solution containing the RP11-196G11.6 oligonucleotide

probe (primary antibody) was added to the sample under a coverslip

and incubated at 42°C overnight. Post-hybridization washes included

2X SSC (5 min twice), 0.5X SSC (15 min) and 0.2X SSC (15 min) at

37°C. Subsequently, the sections were blocked and incubated with

biotinylated mouse anti-digoxigenin (secondary antibody) at 37°C

for 1 h, washed with PBS and treated with SABC-Cy3 at 37°C for 1 h.

After the final PBS washes, the nuclei were counterstained with

DAPI (cat. no. KGA215-50;Nanjing KGI Biological Technology

Development Co., Ltd.). The images were captured via fluorescence

microscopy (DAPI and CY3 channels; CKX53; Olympus Corporation), and

image analysis was performed using ImageJ (version 1.53q; National

Institutes of Health). Background correction was performed using

five cell-free regions. Nuclei were identified via Otsu's

thresholding and watershed segmentation (excluding

abnormal/incomplete nuclei). CY3 integrated density (IntDen) was

measured within nuclear regions of interest and normalized to

nuclear area, which was defined by nuclear segmentation performed

on DAPI channel images, using the following formula: Normalized

intensity=(CY3 IntDen-Background)/Nuclear Area. Measurements were

verified across three non-overlapping fields. Normalized intensity

values were compared between MYCN+ and MYCN−

groups.

Cell culture and transfection

SH-SY5Y (cat. no. iCell-h187; iCell Bioscience,

Inc.), IMR-32 (cat. no. CL-0124; Procell Life Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) and 293T (cat. no. CL-0005; Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) cells were confirmed by short

tandem repeat profiling. IMR-32 and SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in

MEM (cat. no. 11090081; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and

293T cells were cultured in DMEM (cat. no. 11965092; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no.

10100147C; Gibco: Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122;Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The cells were cultured in a cell incubator at

37°C and 5% CO2.

IMR-32 and SH-SY5Y cells were transfected at 70%

confluence using Lipofectamine® 3000 Transfection Kit

(cat. no. L3000150; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, for each well of

a 6-well plate, 2.5 µg RP11-196G11.6 overexpression vector

[oe-RP11; pcDNA3.1(+) vector utilized as the plasmid backbone], 3.3

µg RP11-196G11.6 small interfering (si)RNA [si-RP11 (125 µl/1OD)]

or 0.4 µg mimics (20 µmol/l) were diluted in 125 µl Opti-MEM with 5

µl P3000 reagent, whereas 5 µl Lipofectamine 3000 was diluted in

125 µl Opti-MEM. After 5 min incubation at 37°C, the two solutions

were combined, incubated for 15 min at 37°C and added to cells in

serum-free medium. Following 6 h transfection, the medium was

supplemented with complete medium containing 20% FBS, and cells

were analyzed after 48 h of incubation at 37°C. The si-RP11,

oe-RP11, miR-376a-3p mimic and corresponding controls were all

provided by Jiangxi Zhonghong Boyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Transfection was performed according to the instructions of the

Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Kit. Briefly, si-RP11 and

si-negative control (NC) were transfected into IMR-32 cells; and

oe-RP11 and oe-NC were transfected into SH-SY5Y cells. To assess

whether RP11-196G11.6 mediates its effect on NB cells by regulating

the expression of miR-376a-3p, SH-SY5Y cells were co-transfected

with oe-RP11 or oe-NC, and the miR-376a-3p mimic or mimic NC. The

sense and antisense sequences of the si-RP11 and si-NC, together

with the sequences of the hsa-miR-376a-3p mimic and mimic NC, are

detailed in Table I.

| Table I.RP11-196G11.6-siRNA and

hsa-miR-376a-3p mimic sequences. |

Table I.

RP11-196G11.6-siRNA and

hsa-miR-376a-3p mimic sequences.

| Name | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

|

RP11-196G11.6-siRNA | S:

GUCACUAGACAUCCUGAAA |

|

| AS:

UUUCAGGAUGUCUAGUGAC |

| Negative

control-siRNA | S:

UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU |

|

| AS:

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA |

| hsa-miR-376a-3p

mimic | S:

AUCAUAGAGGAAAAUCCACGU |

|

| AS:

ACGUGGAUUUUCCUCUAUGAU |

| Negative control

mimic | S:

UCACAACCUCCUAGAAAGAGUAGA |

|

| AS:

UCUACUCUUUCUAGGAGGUUGUGA |

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Cellular total RNA was extracted using the miRNA

Extraction Kit (cat. no. CWY113S; CWBio) for miRNA, and the

Ultrapure RNA Kit (cat. no. CW0581M; CWBio) for lncRNA and mRNA.

Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from the respective RNA

fractions using the miRNA Extraction Kit (cat. no. CWY113S; CWBio)

or the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (cat. no.

R223-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.), in accordance with the

manufacturers' protocols. Subsequently, fluorescence qPCR was

performed using a fluorescence PCR instrument with SuperStar

Universal SYBR Master Mix (cat. no. CW3360M; CWBio), as follows:

Pre-denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 58°C for 30 sec and

extension at 72°C for 30 sec. β-actin and U6 were employed as

endogenous controls for lncRNA/mRNA and miRNA normalization,

respectively, and the relative expression levels of each gene were

calculated with the 2−ΔΔCq method (25). The specific primer sequences were as

follows: Forward (F), 5′-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3′ and reverse (R),

5′-CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3′ for β-actin NM_001101.5); F,

5′-CCAAGAAGGGCACAGGGAA-3′ and R, 5′-GGAGTGAATGGGTGGGAGTTT-3′ for

RP11-196G11.6 (ENST00000622229.1); F, 5′-CACCTCCATTGTCTTCCC-3′ and

R, 5′-CCACTACTGCCCATTTCC-3′ for U47924.29 (ENST00000606539.1); F,

5′-GACTTGTCTTTCGGGTTC-3′ and R, 5′-CCTGGCAGCAATACTTTA-3′ for

AC000068.10 (ENST00000608816.1); F, 5′-GATCAGCAGTTCGAGACCAGC-3′ and

R, 5′-CACCTCACGTCACCTTCCATAA-3′ for RP3-508I15.9

(ENST00000423346.1); F, 5′-GCGTACTGCAGACGTGGCA-3′ and R,

5′-AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT-3′ for hsa-miR-509-3-5p (MIMAT0004975); F,

5′-GCGCGATCATAGAGGAAAATC-3′ and R, 5′-AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT-3′ for

hsa-miR-376b-3p (MIMAT0002172) F, 5′-CGCGCGATCATAGAGGAAAAT-3′ and

R, 5′-AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT-3′ for hsa-miR-376a-3p (MIMAT0000729);

F, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ and R, 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′ for U6

(cat. no. NR_004394.1).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The transfected cells were plated uniformly in

96-well plates at a density of 3,000 cells/well and cultured

overnight. At the specified time, the culture medium was discarded

and the medium was replaced with serum-free medium containing CCK-8

reagent (cat. no. C0041; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, the absorbance values of each

well were determined at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate

reader (cat. no. WD-2012B; Beijing Liuyi Biotechnology, Co.,

Ltd.).

Apoptosis detected using flow

cytometry

Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using the

Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit [cat. no. AP101-100-kit;

Multisciences (Lianke) Biotech Co., Ltd.]. After digestion of

SH-SY5Y or IMR-32 cells from a 6-well plate, a single-cell

suspension with a concentration of 1×106/well was

prepared. After centrifugation at 450 × g for 3 min at 37°C, the

samples were washed twice with PBS. The cells were then resuspended

in 300 µl precooled 1XBinding Buffer, 5 µl Annexin V-FITC and 10 µl

PI were added to each well and mixed gently, and the cells were

incubated for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The changes

in apoptosis were observed using a flow cytometer (NovoCyte 2060R;

ACEA Biosciences; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Data analysis was

performed using FlowJo (version v10.9.0; BD Biosciences). Apoptotic

cells were defined as the cell population positive for Annexin

V-FITC and negative for PI (early apoptosis), or positive for both

Annexin V-FITC and PI (late apoptosis).

Cell scratch assay for cell

migration

The cells (3×105/well) were cultured in

6-well plates until they reached 80–90% confluence with normal

morphology and stable growth kinetics. Subsequently, the cells were

inoculated into 24-well plates and cultured overnight to ensure

cell attachment. Scratches were then made perpendicular to the

bottom of the well using a 200-µl pipette tip. The cells were then

cultured in serum-free medium for 24 h and images were captured

under a light microscope (BX43; Olympus Corporation). The cell

migration rate was calculated using the following formula: Cell

migration rate (%)=[(A0-A24)/A0]

×100. (A0 refers to the initial wound area at 0 h;

A24 indicates the remaining wound area at the measured

24 h).

Transwell assay for cell invasion

The cells were cultured until they reached 80–90%

confluence with normal morphology and stable growth kinetics.

Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in serum-free medium. A

500-µl aliquot of cell-specific medium supplemented with 10% FBS

was added to the lower chamber of a 24-well Transwell invasion

chamber (BioCoat® Matrigel® Invasion Chamber;

8-µm pore size; cat. no. 354480; Corning, Inc.). The upper chamber

was seeded with a 300-µl cell suspension containing

5×104 cells/well. After incubation in a 37°C

CO2 incubator for 24 h, the chambers were removed, the

medium was discarded and the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal

violet for 1 h at 37°. The unmigrated cells in the upper chambers

were removed with a cotton swab and the cells that had invaded the

lower chambers observed under a light microscope (BX43; Olympus

Corporation). After images were captured, the staining solution was

removed, the samples were treated with 33% acetic acid and the

absorbance value of each well was measured at 562 nm with an enzyme

labeling instrument (cat. no. WD-2012B; Beijing Liuyi

Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.).

Western blotting (WB)

The cells were harvested, the culture medium was

discarded and total protein was extracted with RIPA lysis buffer

(cat. no. C1053; Beijing Applygen Technologies, Inc.). After

centrifugation at 14,490 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was

collected and total protein was quantified using a BCA protein

quantification kit (cat. no. E-BC-K318-M; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). After denaturation of the protein

samples, the loading volume was calculated based on a protein

amount of 20 µg/lane. SDS gel (10% separating gel and 5% stacking

gel) electrophoresis was performed for 1.5 h, followed by constant

flow of the membrane at 300 mA for 1 h. The PVDF membrane (cat. no.

IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma) was sealed with 3% non-fat dry milk for

1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies

against RING1 and YY1-binding protein (RYBP; cat. no. 68130-1-Ig;

Proteintech Group, Inc.; 1:2,000), EGFR (cat. no. GB11084-2; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; 1:1,000), phosphorylated (p)-EGFR

(cat. no. YP0086; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company; 1:1,000),

vimentin (cat. no. GB11192; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.;

1:1,000), GAPDH (cat. no. HC301; TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.;

1:2,000) and E-cadherin [cat. no. GB12868; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.; 1:1,000] overnight at 4°C. The following day,

the PVDF membrane was incubated with the HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.; 1:2,000) or HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse

IgG (H+L) (cat. no. GB23301; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.;

1:2,000) secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. The

membrane was washed with 1X TBS-0.1% Tween buffer. Subsequently,

the PVDF membrane was incubated with SuperSignal® West

Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (cat. no. RJ239676; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and imaged using an ultra-high sensitivity

chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon-5200; Tanon Science and

Technology Co., Ltd.). Semi-quantitative analysis was performed

using Image Lab software (version 6.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.).

Dual-luciferase reporter gene

assay

In the dual-luciferase reporter gene assay, the

wild-type (WT) and mutant (MUT) binding sequences of RP11-196G11.6

or RYBP 3′-UTR were cloned into the pmirGLO vector (Promega

Corporation). The 239T cells were seeded in 24-well plates and were

co- transfected with the following sequences using Lipofectamine

3000: i) To assess the RP11-196G11.6-miR-376a-3p interaction, cells

were co-transfected with WT-RP11 vector + miR-376a-3p mimic,

WT-RP11 vector + NC mimic, MUT-RP11 vector + miR-376a-3p mimic or

MUT-RP11 vector + NC mimic; ii) to assess the miR-376a-3p-RYBP

interaction, cells were co-transfected with WT-RYBP vector +

miR-376a-3p mimic, WT-RYBP vector + NC mimic, MUT-RYBP vector +

miR-376a-3p mimic or MUT-RYBP vector + NC mimic.

WT-RP11-196G11.6-pmirGLO, MUT-RP11-196G11.6-pmirGLO,

WT-RYBP-pmirGLO and MUT-RYBP-pmirGLO were obtained from ZHBY

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. After transfection according to the

experimental protocol of the dual-luciferase reporter gene assay

kit (cat. no. RG027; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), the

cells were cultured for 24 h. The medium was discarded and the

remaining medium was washed with PBS. The supernatant was collected

after the cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (cat. no.

RG027; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) Firefly and

Renilla luciferase activities were measured sequentially

using a chemiluminescence device (Glomax® 20/20

Luminometer; Promega Corporation) and the ratio of the two was

calculated as relative luciferase activity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and the visualization of

experimental data were performed using IBM SPSS software (version

22.0; IBM Corp.). Measurement data that follow a normal

distribution are presented as the mean ± SD. For comparisons among

multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test

was used. For comparisons between two groups, unpaired Student's

t-test was employed. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used

when both variables followed a normal distribution. For variables

that deviated from normality or were ordinal in nature, Spearman's

rank correlation coefficient was applied. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference. All experiments

were performed with a minimum of three independent replicates. A

graphical abstract for the present study is available in Fig. S1.

Results

Analysis of DElncRNAs in tumor tissues

and DTC samples

First, an NB transcriptome sequencing dataset was

downloaded from the GEO (accession no. GSE94035). Different NB

samples (tumor samples and DTC samples with and without MYCN

amplification) were analyzed at the molecular level. Using PCA, a

clear distinction between tumor and DTC samples, and between

MYCN+ and MYCN− tumor samples was identified,

but PCA was unable to distinguish between MYCN+ and

MYCN− DTC samples (Fig.

1B). The PCA results suggested that MYCN may serve a key role

in tumor growth. Therefore, the DEGs between MYCN+ and

MYCN− samples were analyzed, and a total of 4,551 DEGs

were detected in tumors (2,230 upregulated and 2,321

downregulated), whereas 2,714 DEGs were detected in DTCs (917

upregulated and 1,797 downregulated) (Fig. 1C). As shown in the Venn diagram, a

total of 808 DEGs were detected, of which 339 were upregulated and

469 were downregulated (Fig. 1D).

GO enrichment analysis revealed the GO terms that were most

enriched in DEGs. As shown in Fig.

1E, specific upregulated DEGs regulated by MYCN in DTCs were

enriched in ‘extracellular matrix disassembly’, ‘collagen catabolic

process’, ‘cellular response to cAMP’, ‘positive regulation of

vasodilation’ and ‘axon guidance’. Downregulated DEGs in DTCs were

enriched in ‘cytokine-mediated signaling pathway’, ‘type I

interferon-mediated signaling pathway’, ‘immune response’ and

‘inflammatory response’. These biological processes were associated

with NB metastasis and invasion.

Next, the lncRNAs among the DEGs were analyzed.

Using PCA, a clear distinction was identified between tumor samples

and DTC samples, and between MYCN+ and MYCN−

tumor samples, whereas MYCN+ and MYCN− DTC

samples could not be distinguished (Fig. 1F). In addition, 1,110 DElncRNAs were

identified in tumors (758 upregulated and 352 downregulated),

whereas 793 DElncRNAs were identified in DTCs (231 upregulated and

562 downregulated) (Fig. 1G). Venn

diagrams of the upregulated and downregulated lncRNAs in

MYCN+ tumor and DTC samples revealed that 73 DElncRNAs

were co-upregulated and that 88 DElncRNAs were co-downregulated

(Fig. 1H). WGCNA and co-expression

analysis were analyzed between DElncRNAs and DEmRNAs in tumor and

DTC samples (Fig. 1I). The results

demonstrated that MYCNOS, XLOC-1045657, SNHG19, AC012123.1 and

SNHG8 were the primary DElncRNAs in DTCs, whereas MYCNOS,

EPB41L4A-AS1, RP11-92J19.3 and ZFAS1 were the primary DElncRNAs in

tumors. The top 10 most enriched GO terms by DEmRNAs co-expressed

with DElncRNAs are shown in Fig.

1J, which include a large number of signaling pathways

associated with inflammation/immunity. These findings indicated

that DElncRNA may serve a role in the progression of NB via

immune-related pathways.

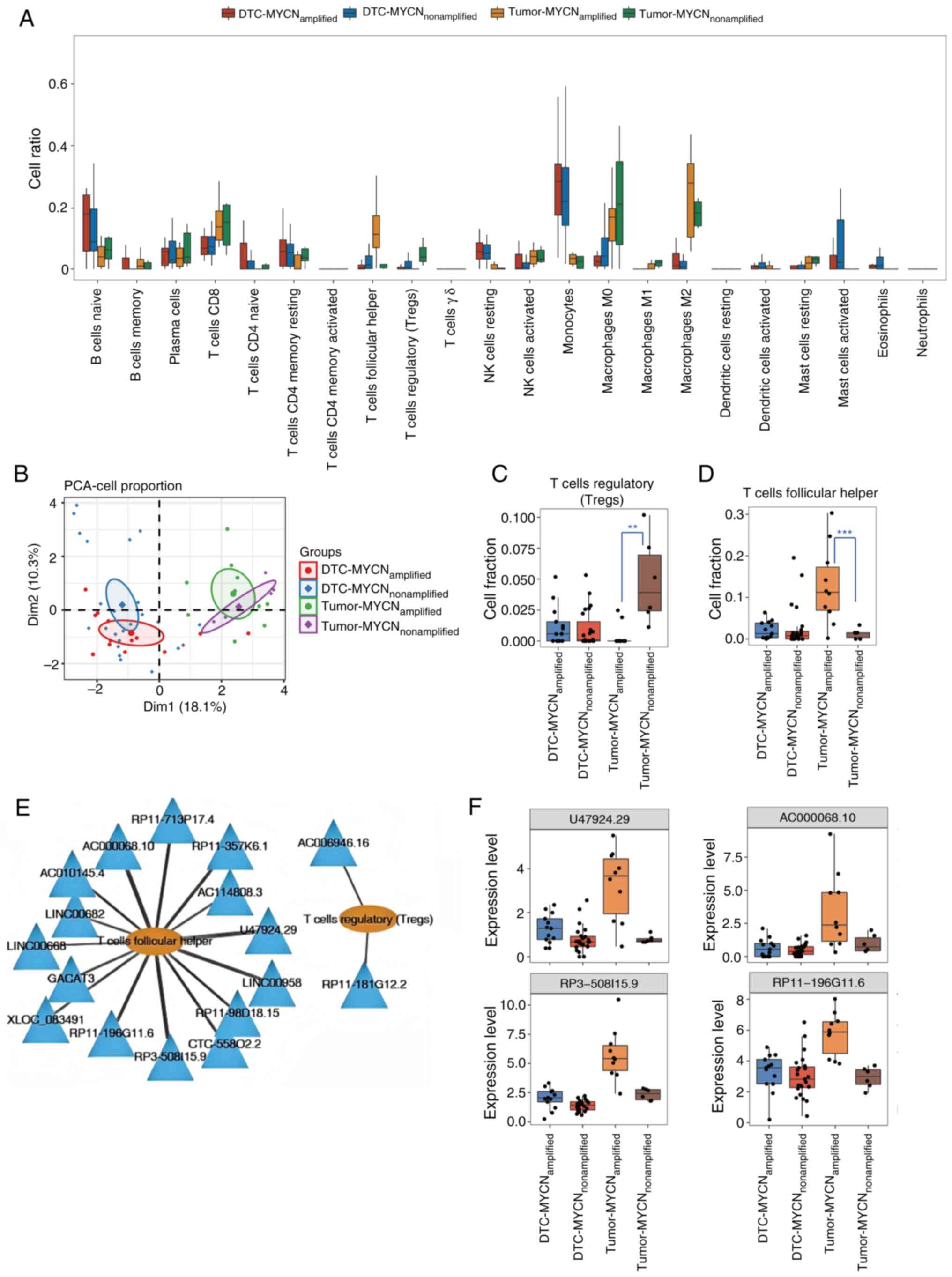

Analysis of DElncRNAs associated with

Tregs and Tfhs

CIBERSORT was used to analyze the proportion of each

immune cell type in MYCN+ and MYCN− tumor and

DTC samples (Fig. 2A). Based on the

magnitude of intergroup differences between MYCN+ and

MYCN− samples in both tumor and DTC samples. Tregs

demonstrated the highest proportion in the tumor-nonamplified

group, whereas Tfhs were most abundant in the tumor-amplified

group. By contrast, other cell types such as monocytes/macrophages

showed minimal differences between groups. PCA revealed that the

different types of cells clearly differentiated between the DTC and

tumor samples, but the MYCN+ samples and

MYCN− samples were indistinguishable (Fig. 2B). Fig.

2C and D display the specific proportions of Tregs and Tfhs in

the four types of samples. In DTC samples, there was no significant

difference in the proportions of Tregs or Tfhs between

MYCN+ and MYCN− samples. However, in tumor

samples, the proportion of Tregs in MYCN+ samples were

markedly lower compared with that in MYCN− samples,

whereas the proportion of Tfhs in MYCN+ samples was

markedly higher compared with that in MYCN− samples.

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was further

calculated on the basis of the expression level of DElncRNAs and

the ratio of Tregs to Tfhs, and 15 lncRNAs were shown to be

associated with Tfhs, while two lncRNAs were associated with Tregs.

The lncRNA-immune cell infiltration networks were constructed with

Cytoscape (Fig. 2E), which revealed

the lncRNAs associated with Tregs and Tfhs. Fig. 2F displays the expression levels of

the top four DElncRNAs (U47924.29, AC000068.10, RP3-508I15.9 and

RP11-196G11.6) associated with Tfh infiltration as determined by

Spearman's rank correlation analysis. In DTC samples, there was no

notable change in the expression levels of these four lncRNAs

between the MYCN+ and MYCN− samples. However,

in tumor samples, the expression levels of these lncRNAs were

markedly higher in MYCN+ samples compared with those in

MYCN− samples. The present study findings suggested that

these four lncRNAs may be associated with NB tumor growth as well

as immune infiltration. Next, the expression levels of these four

lncRNAs were verified in MYCN+ and MYCN−

cells using RT-qPCR. It was identified that only RP11-196G11.6

exhibited successful amplification and showed high expression in

MYCN+ cells, while the other three lncRNAs failed to

amplify, exhibiting delayed amplification profiles and aberrant

dissociation curves, likely attributable to their inherently low

expression levels in NB cells, which precluded further validation

(Fig. S2). Thus, RP11-196G11.6 was

selected for subsequent experimentation.

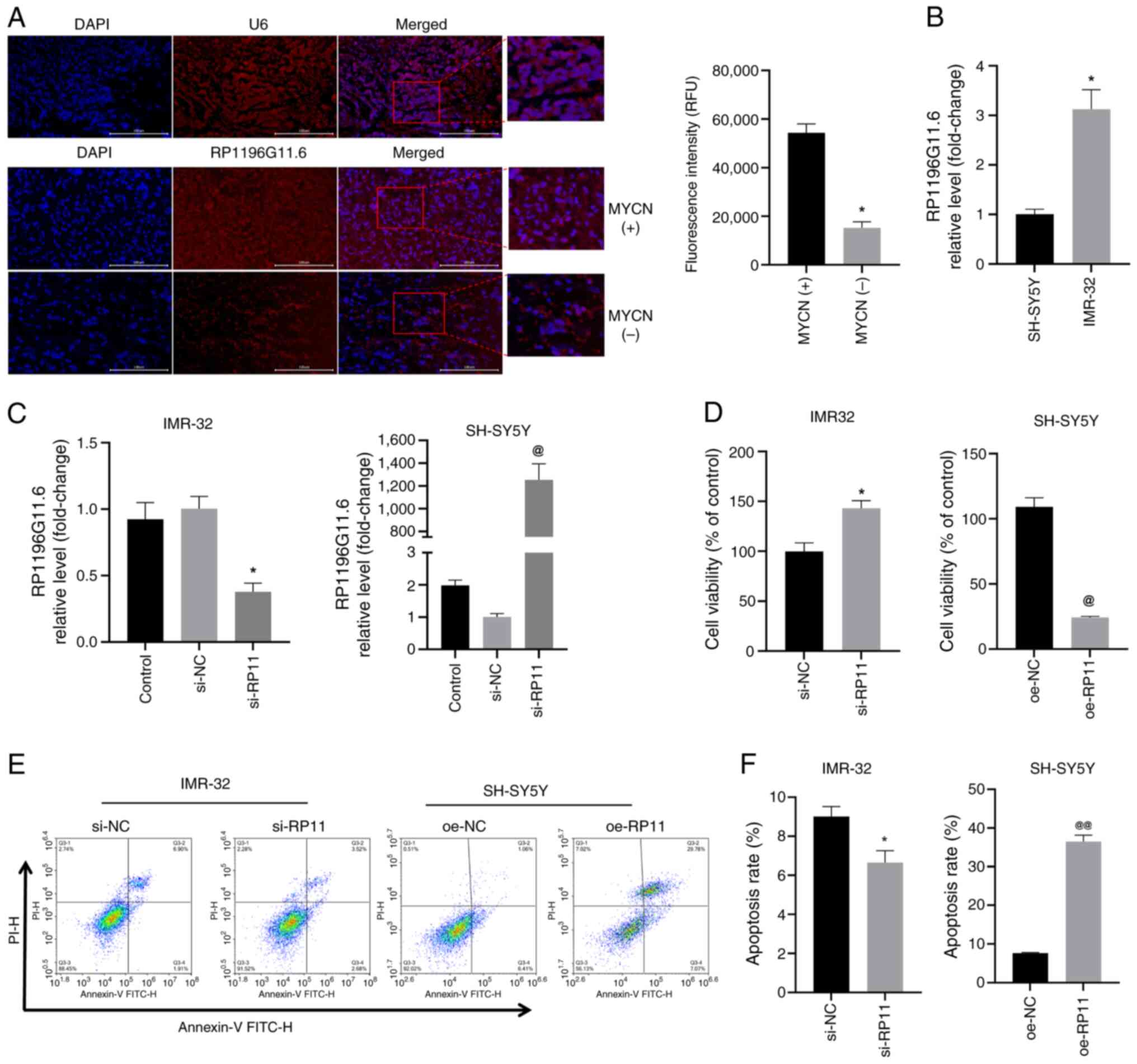

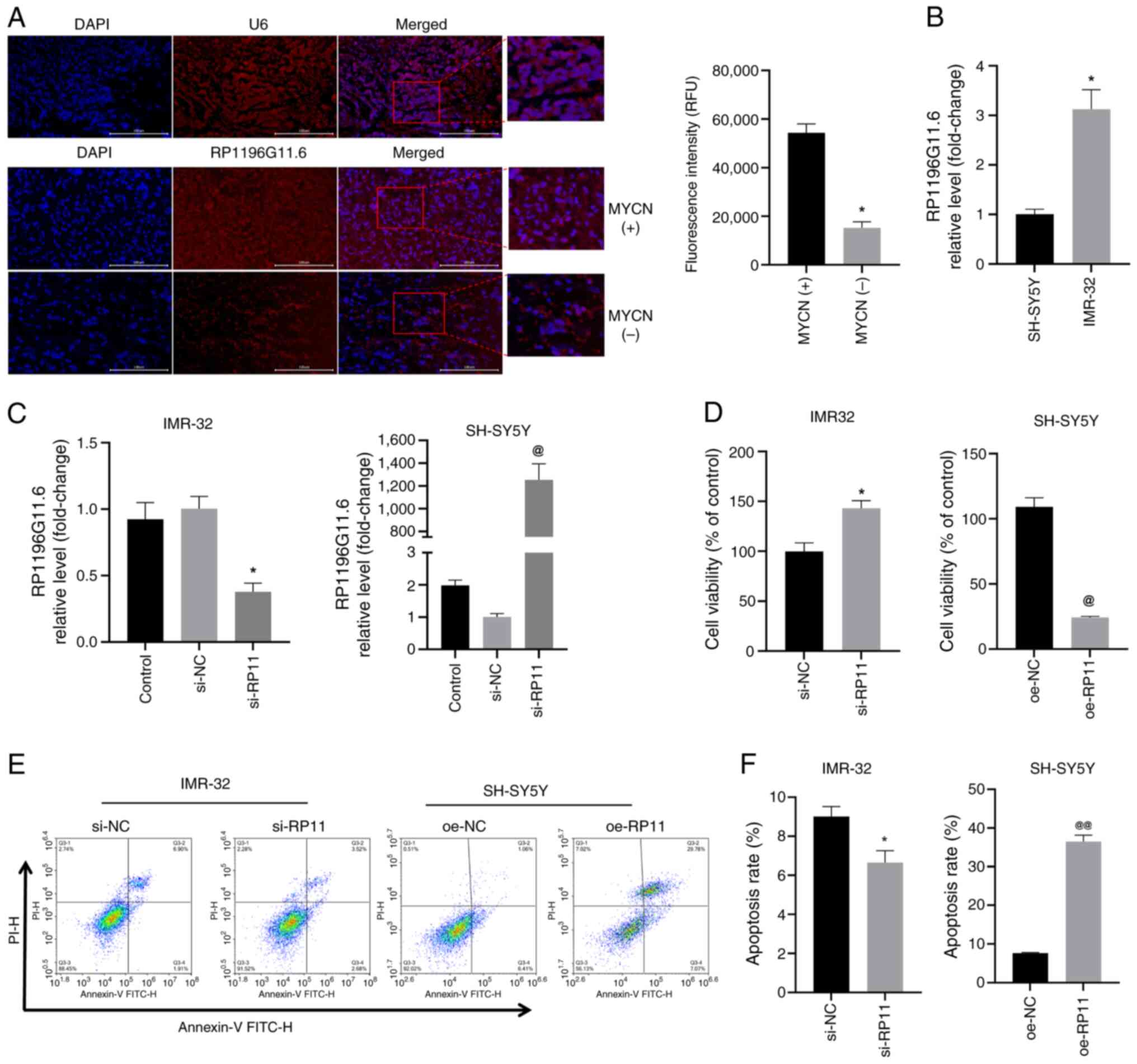

RP11-196G11.6 is highly expressed in

MYCN+ NB tumor tissues and MYCN+ cells

First, the expression of RP11-196G11.6 was examined

in MYCN+ and MYCN− NB tumor tissues using

FISH. According to the present study findings (Fig. 3A), RP11-196G11.6 was highly

expressed in MYCN+ NB tumor tissues. Next, the

expression levels of RP11-196G11.6 were examined in

MYCN− (SH-SY5Y) and the MYCN+ (IMR-32) NB

cell lines by RT-qPCR. The results revealed that the expression

levels of RP11-196G11.6 were significantly higher in IMR-32 cells

compared with those in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that

RP11-196G11.6 may be highly expressed in MYCN+ NB tumor

tissues and cells.

| Figure 3.RP11is highly expressed in

MYCN+ NB tumor tissues and MYCN+ NB cells,

and RP11 upregulation inhibits NB cell viability. (A) FISH analysis

revealed the expression level of RP11 in MYCN+ and

MYCN− NB tumor tissue specimens (scale bar, 100 µm; U6,

control probe). *P<0.05 vs. MYCN+ group. (B)

Quantification of RP11 levels in SH-SY5Y and IMR-32 cells by

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. *P<0.05 vs. SH-SY5Y. (C)

Quantification of RP11 levels in IMR-32 cells following

transfection with si-RP11 and RP11 levels in SH-SY5Y cells

following transfection with oe-RP11. *P<0.05 vs. si-NC,

@P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. (D) Viability of IMR-32 and

SH-SY5Y cells was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay.

*P<0.05 vs. si-NC, @P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. (E) Levels

of apoptosis were assessed using flow cytometry in IMR-32 and

SH-SY5Y cells. (F) Apoptosis rate of IMR-32 and SH-SHY5Y cells

*P<0.05 vs. si-NC or @@P<0.01 vs. oe-NC. RP11,

RP11-196G11.6; si, small interfering; oe, overexpression; NB,

neuroblastoma; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; NC,

negative control. |

RP11-196G11.6 inhibits the viability,

migration and invasion of NB cells

si-RP11 was transfected into IMR-32 cells and

oe-RP11 was transfected into SH-SY5Y cells; subsequently, RT-qPCR

confirmed that siRNA transfection significantly downregulated

RP11-196G11.6 expression in IMR-32 cells, whereas transfection with

oe-RP11 resulted in substantial upregulation of RP11-196G11.6 in

SH-SY5Y cells, thereby validating the successful knockdown and

overexpression of this lncRNA (Fig.

3C). The results of the CCK-8 assay (Fig. 3D) revealed that RP11-196G11.6

knockdown increased IMR-32 cell viability, whereas RP11-196G11.6

overexpression decreased the viability of SH-SY5Y cells. Flow

cytometry (Fig. 3E and F) revealed

that RP11-196G11.6 downregulation significantly inhibited IMR-32

apoptosis, whereas RP11-196G11.6 upregulation significantly

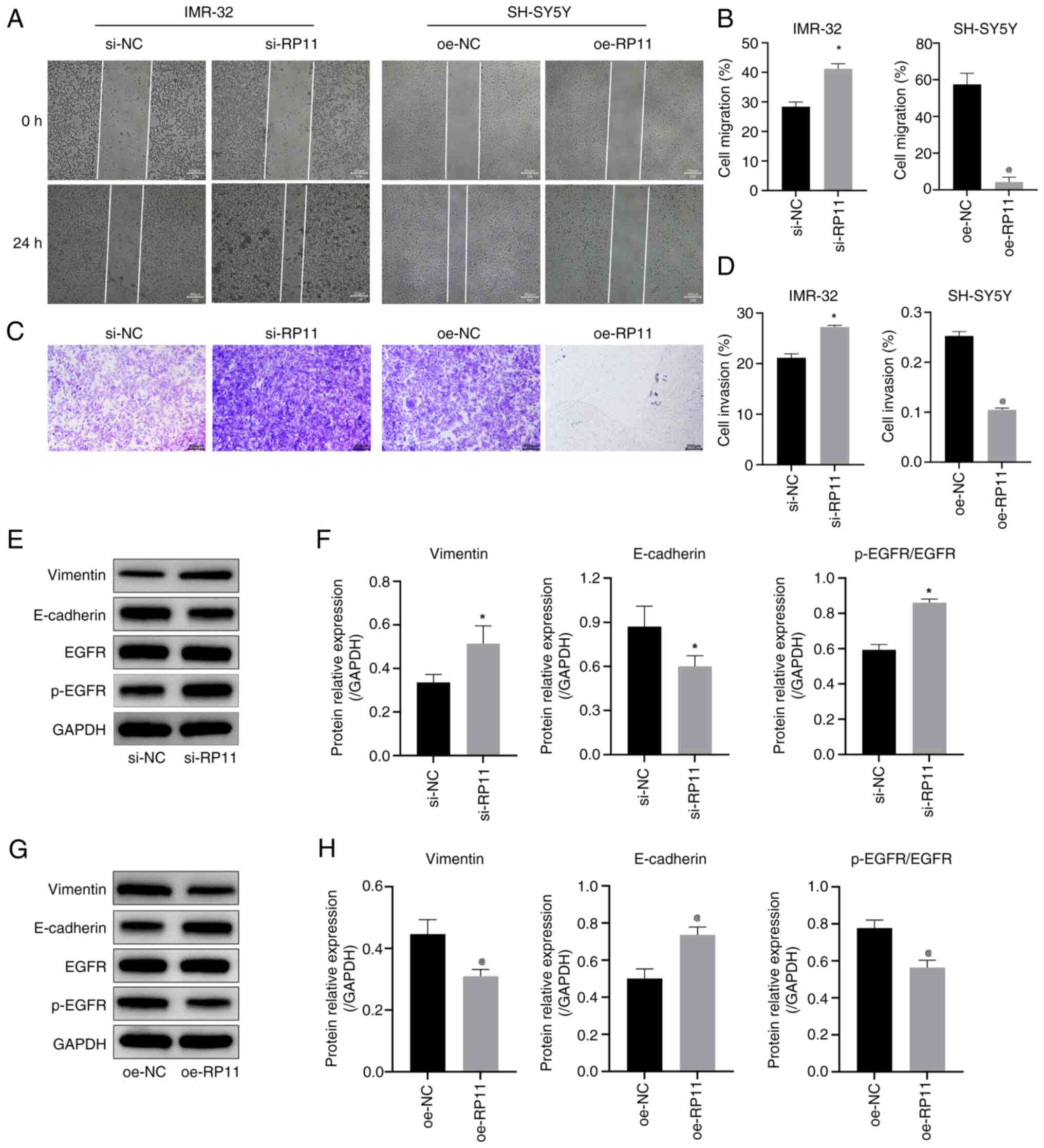

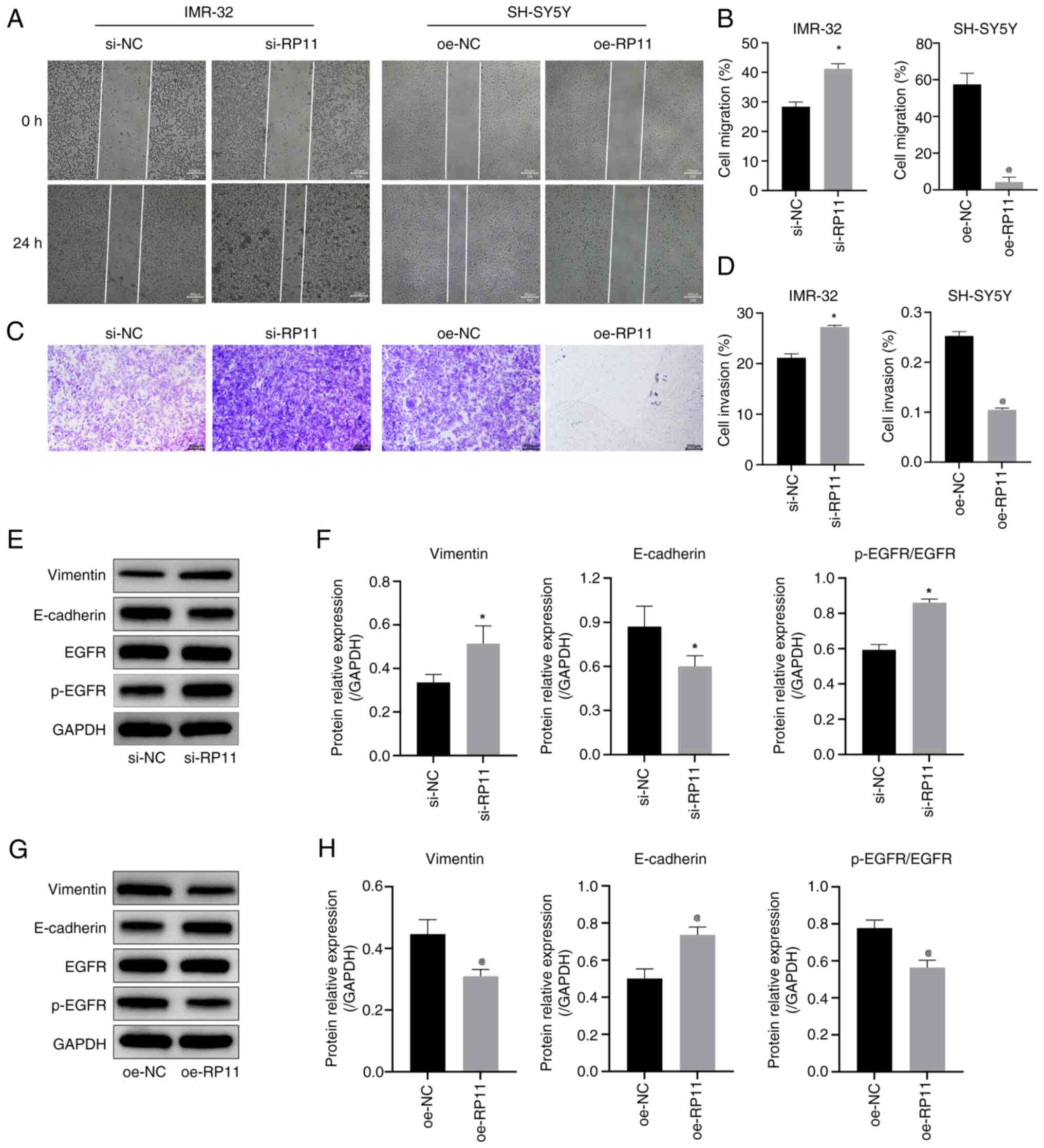

increased SH-SY5Y apoptosis. The results of the cell scratch assay

(Fig. 4A and B) revealed that

RP11-196G11.6 downregulation promoted IMR-32 cell migration,

whereas RP11-196G11.6 upregulation inhibited SH-SY5Y cell

migration. Furthermore, the results of the Transwell assay

(Fig. 4C and D) revealed that

RP11-196G11.6 downregulation promoted IMR-32 cell invasion, whereas

RP11-196G11.6 upregulation inhibited SH-SY5Y cell invasion. These

results indicated that RP11-196G11.6 knockdown could promote NB

cell viability, migration and invasion, whereas RP11-196G11.6

upregulation may inhibit these processes.

| Figure 4.RP11 upregulation inhibits

neuroblastoma cell migration and invasion. (A) Cell scratch assay

results indicated that knockdown of RP11 expression promoted

migration in IMR-32 cells and oe-RP11 suppressed migration in

SH-SY5Y cells (scale bar, 200 µm). (B) Comparison of cell migration

rates in IMR-32 and SH-SY5Y cells in the cell scratch assay.

*P<0.05 vs. si-NC, @P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. (C)

Transwell assay results indicated that knockdown of RP11 expression

promoted invasion in IMR-32 cells and oe-RP11-196G11.6 suppressed

invasion in SH-SY5Y cells (scale bar, 200 µm). (D) Quantitative

analysis of cell invasion rate in the Transwell assay. *P<0.05

vs. si-NC, @P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. (E) Representative WB

images in IMR-32 cells. (F) Expression levels of vimentin,

E-cadherin and p-EGFR/EGFR in IMR-32 cells *P<0.05 vs. si-NC.

(G) Representative WB images in SH-SY5Y cells. (H) Expression

levels of vimentin, E-cadherin and p-EGFR/EGFR protein in SH-SY5Y

cells. @P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. RP11, RP11-196G11.6; si,

small interfering; oe, overexpression; WB, western blotting; p-,

phosphorylated; NC, negative control. |

Next, the expression levels of the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related proteins, vimentin,

E-cadherin, EGFR and p-EGFR, were detected in NB cells by WB. The

results in IMR-32 cells (Fig. 4E and

F) revealed that the downregulation of RP11-196G11.6

significantly decreased the protein expression levels of

E-cadherin, and significantly increased the protein expression

levels of vimentin and p-EGFR/EGFR. By contrast, the results in

SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4G and H)

revealed that the upregulation of RP11-196G11.6 significantly

increased the protein expression levels of E-cadherin, but

significantly decreased the protein expression levels of vimentin

and p-EGFR/EGFR. These results indicated that the upregulation of

RP11-196G11.6 may inhibit the viability, migration and invasion of

NB cells, and promote their apoptosis.

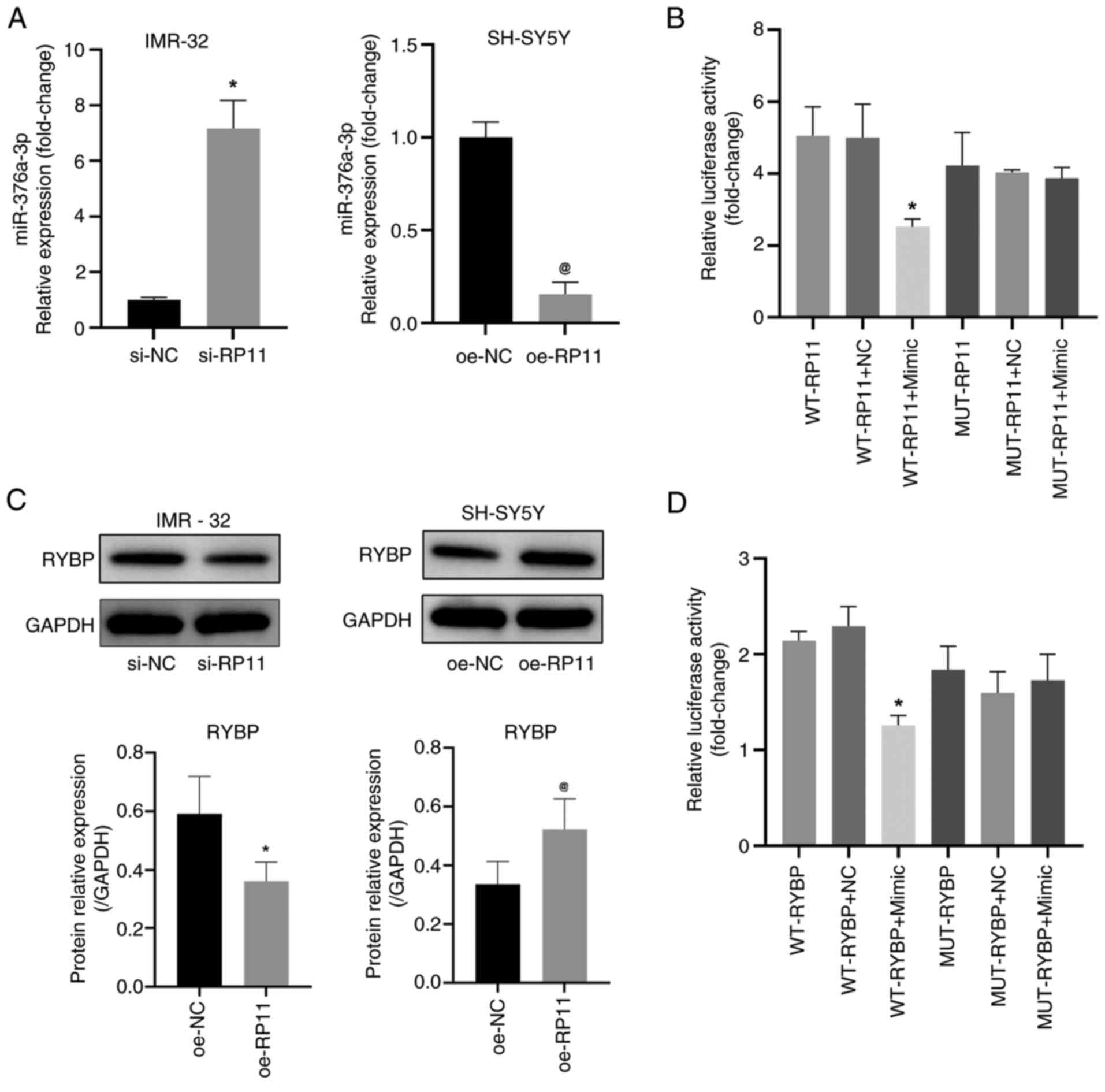

RP11-196G11.6 targets and inhibits the

expression of miR-376a-3p in NB cells

miRanda predicted that the following three miRNAs

could potentially bind to RP11-196G11.6: i) miR-376b-3p ii)

miR-509-3-5p and iii) miR-376a-3p. These predictions were confirmed

by RT-qPCR, which revealed that miR-376b-3p and miR-509-3-5p failed

to amplify, exhibiting delayed amplification profiles and aberrant

dissociation curves, likely attributable to their inherently low

expression levels in NB cells, which could not be further

validation (Fig. S3). However, it

was revealed that the downregulation of RP11-196G11.6 significantly

increased the expression levels of miR-376a-3p in IMR-32 cells

whereas the upregulation of RP11-196G11.6 significantly decreased

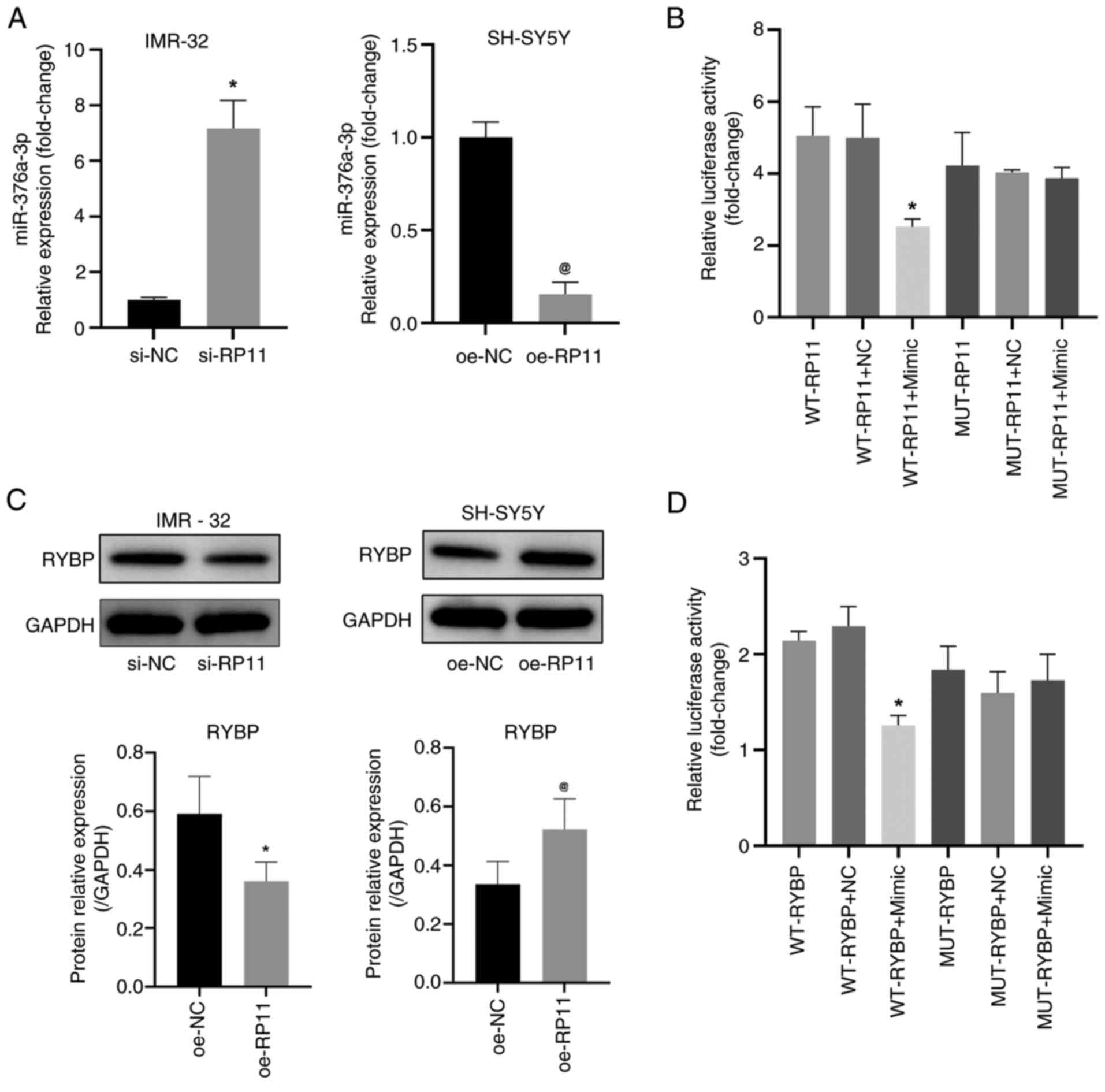

the expression levels of miR-376a-3p in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, a dual-luciferase

reporter gene assay (Fig. 5B)

revealed that luciferase activity was significantly lower in the

WT-RP11 + miR-376a-3p mimic group compared with that in the WT-RP11

+ NC mimic group; however, the luciferase activity was not

evidently different between the MUT-RP11 + NC group and the

MUT-RP11 + mimic group. These results indicated that RP11-196G11.6

could target and inhibit the expression of miR-376a-3p. Using miRDB

prediction, RYBP was identified as a downstream target gene of

miR-376a-3p and RYBP has been confirmed to be associated with tumor

suppression (26–28), including in hepatocellular

carcinoma, colorectal cancer and lung cancer. Therefore, the

protein expression levels of RYBP in cells was assessed by WB. The

results revealed that the downregulation of RP11-196G11.6

significantly decreased the protein levels of RYBP in IMR-32 cells

whereas the upregulation of RP11-196G11.6 significantly increased

the protein levels of RYBP in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 5C). The targeting relationship

between miR-376a-3p and RYBP was further verified using the

dual-luciferase reporter gene assay. Compared with that in the

WT-RYBP + NC mimic group, luciferase activity was significantly

lower in the WT-RYBP + miR-376a-3p mimic group; however, the

luciferase activity was not evidently different between the

MUT-RYBP + NC group and the MUT-RYBP + mimic group (Fig. 5D). These results suggested that

miR-376a-3p can bind to RYBP.

| Figure 5.RP11 inhibits miR-376a-3p expression

in neuroblastoma cells. (A) Quantification of miR-376a-3p levels in

IMR-32 cells following transfection with si-RP11 and in SH-SY5Y

cells following transfection with oe-RP11. *P<0.05 vs. si-NC,

@P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. (B) Luciferase reporter assay was

performed to measure the activity of the WT or MUT RP11 3′UTR

vector in 293T cells that were co-transfected with either

miR-376a-3p or NC mimics. *P<0.05 vs. WT-RP11 + NC. (C) RYBP

protein levels detected by WB in IMR-32 and SH-SY5Y cells.

*P<0.05 vs. si-NC, @P<0.05 vs. oe-NC. (D)

Luciferase reporter assay was performed to measure the activity of

the WT or MUT RYBP 3′UTR vector in 293T cells that were

co-transfected with either miR-376a-3p or NC mimics. *P<0.05 vs.

WT-RYBP + NC. RP11, RP11-196G11.6; si, small interfering; oe,

overexpression; NC, negative control; WB, western blotting; WT,

wild-type; RYBP, RING1 and YY1-binding protein; MUT, mutant;

miR-376a-3p, microRNA-376a-3p. |

RP11-196G11.6 inhibits NB cell

viability, migration and invasion by downregulating miR-376a-3p

expression

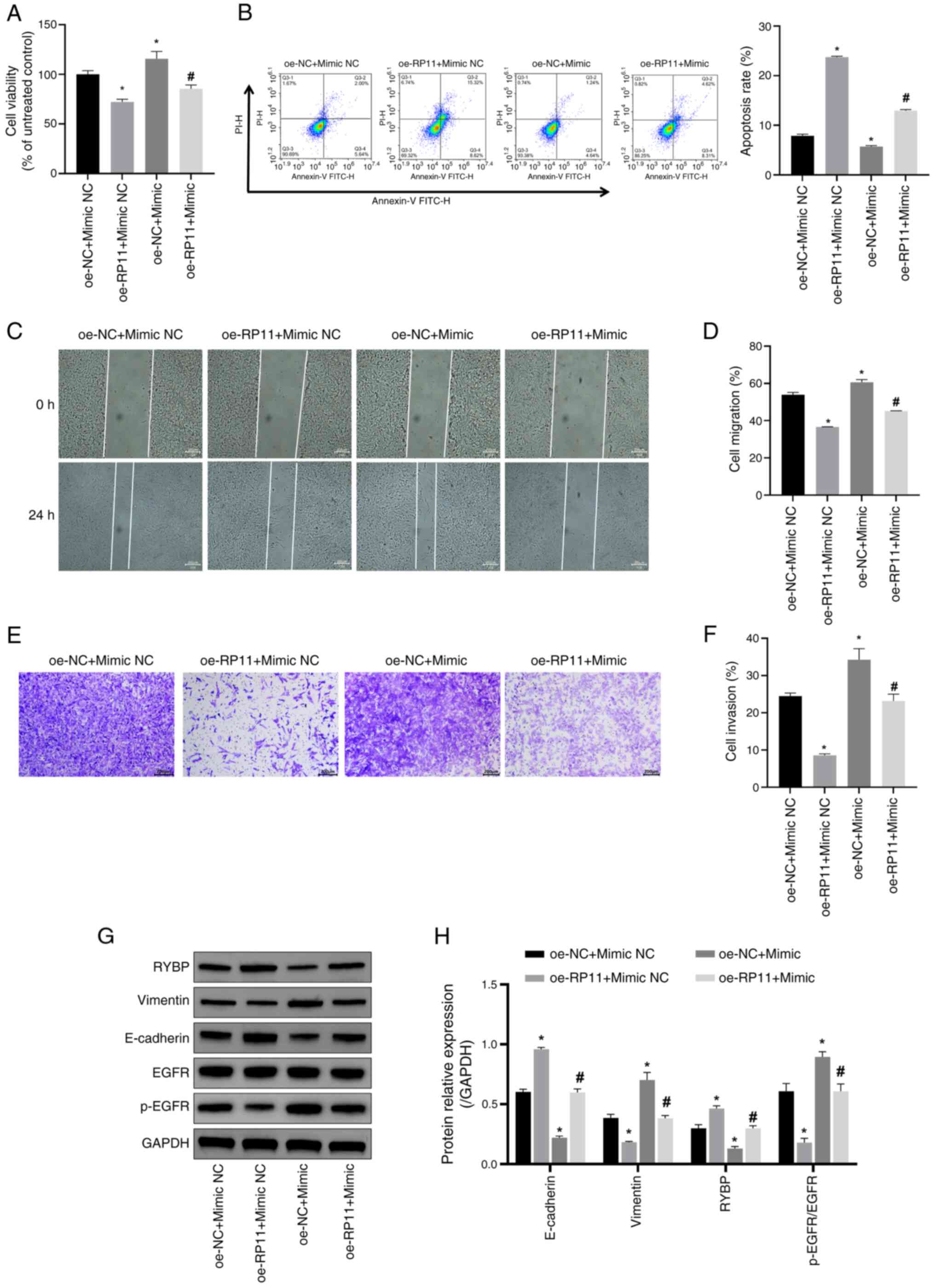

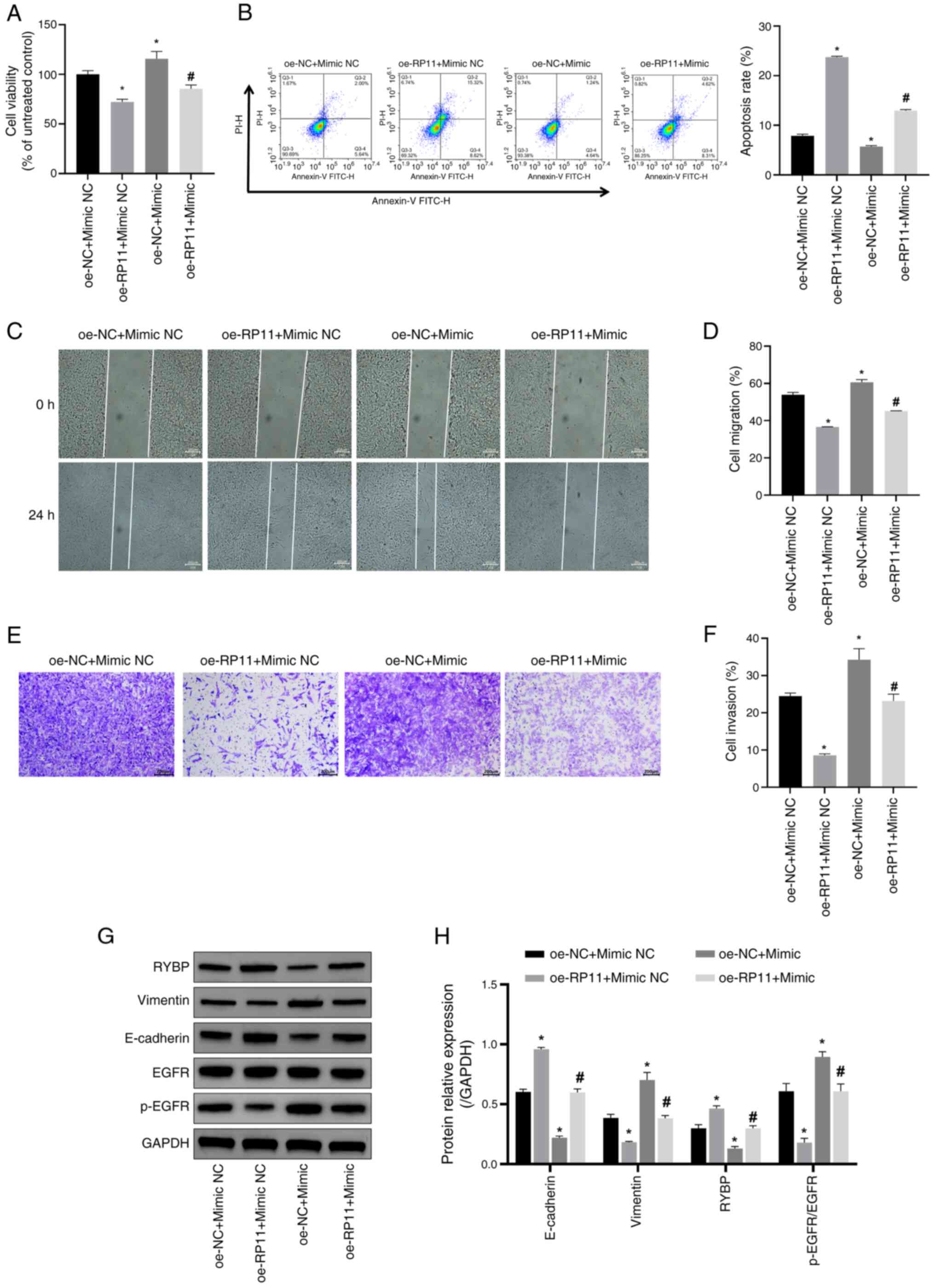

To verify whether RP11-196G11.6 inhibits NB cell

viability, migration and invasion via downregulation of

miR-376a-3p, the effects of miR-376a-3p overexpression (Fig. S4) on the viability, migration and

invasion of SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing RP11-196G11.6 was

examined. The findings indicated that overexpression of miR-376a-3p

reduced apoptosis and increased cell viability; the inhibitory

effects of RP11-196G11.6 overexpression on cell viability (Fig. 6A) and the promotion of apoptosis

(Fig. 6B) were partially reversed

by miR-376a-3p overexpression. These results indicated that

RP11-196G11.6 may inhibit NB cell viability and induce apoptosis by

downregulating miR-376a-3p. In addition, miR-376a-3p overexpression

promoted cell migration and invasion; it partially reversed the

inhibitory effects of RP11-196G11.6 overexpression on cell

migration and invasion (Fig. 6C-F).

These findings suggested that RP11-196G11.6 could inhibit NB cell

migration and invasion by downregulating miR-376a-3p.

| Figure 6.RP11 inhibits SH-SY5Y cell viability,

migration and invasion by downregulating miR-376a-3p expression.

(A) SH-SY5Y cell viability was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8

assay. *P<0.05 vs. oe-NC + mimic NC; #P<0.05 vs.

oe-RP11 + mimic NC. (B) SH-SY5Y apoptosis was assessed using flow

cytometry to assess the levels of SH-SY5Y apoptosis. *P<0.05 vs.

oe-NC + mimic NC; #P<0.05 vs. oe-RP11 + mimic NC. (C)

SH-SY5Y cell migration ability was detected using a cell scratch

assay (scale bar, 200 µm). (D) Comparison of cell migration rates

between the four groups in the cell scratch assay. *P<0.05 vs.

oe-NC + mimic NC; #P<0.05 vs. oe-RP11 + mimic NC. (E)

SH-SY5Y cell invasive ability was detected using a Transwell assay

(scale bar, 200 µm). (F) Quantitative analysis of cell invasion

rate in the four groups. *P<0.05 vs. oe-NC + mimic NC;

#P<0.05 vs. oe-RP11 + mimic NC. (G) Representative

western blotting image. (H) Semi-quantification of RYBP, vimentin,

E-cadherin and p-EGFR/EGFR protein expression levels. *P<0.05

vs. oe-NC + mimic NC; #P<0.05 vs. oe-RP11 + mimic NC.

oe, overexpression; NC, negative control; RP11, RP11-196G11.6;

RYBP, RING1 and YY1-binding protein; miR-376a-3p, microRNA-376a-3p;

p-, phosphorylated. |

Next, the expression levels of the EMT-related

proteins (vimentin, E-cadherin, EGFR, and p-EGFR) and RYBP in

SH-SY5Y cells were detected by WB. The results revealed that,

compared with in the oe-RP11 + Mimic NC group, miR-376a-3p

overexpression in the oe-RP11 + Mimic downregulated the protein

expression levels of RYBP and E-cadherin, but increased the protein

expression levels of vimentin and p-EGFR/EGFR (Fig. 6G and H). Notably, miR-376a-3p

overexpression partially reversed the effects of RP11-196G11.6

overexpression on the expression levels of RYBP, vimentin,

E-cadherin and p-EGFR/EGFR.

Discussion

NB is one of the most common extracranial solid

tumors in children, with notable heterogeneity and prognostic

variability (29,30). MYCN amplification is a key molecular

hallmark of NB, and is closely associated with tumor progression

and poor prognosis (31). As

lncRNAs serve a key role in NB (32), the molecular mechanism of action of

lncRNAs remains to be further explored. In the present study,

different NB samples were explored via bioinformatics analysis to

identify MYCN-related DElncRNAs and analyze their potential roles

in NB development. The results revealed high expression of

RP11-196G11.6 in MYCN-amplified NB cells and further confirmed the

effects of RP11-196G11.6-mediated miR-376a-3p and its downstream

target gene RYBP on NB cell viability, migration and invasion.

First, MYCN-regulated Tregs and Tfhs were identified

via CIBERSORT analysis. Subsequently, using Spearman's rank

correlation analysis of the expression levels of DElncRNAs and the

ratios of Tregs and Tfhs, DElncRNAs that were closely associated

with Tregs and Tfhs were identified, and RP11-196G11.6 was selected

as the focus of the present study. lncRNAs may influence the immune

response by the following two mechanisms: i) lncRNAs regulate the

innate immune response; and ii) lncRNAs regulate T-cell activation,

development and differentiation (33).

Amplification of MYCN was among the earliest genetic

hallmarks identified in NB and remains one of the most robust

predictors of poor prognosis (34).

Functionally, MYCN operates as both a transcription factor and a

key oncogenic driver in this malignancy. As a member of the bHLH-LZ

transcription factor family, MYCN binds canonical E-box motifs to

activate proliferation-related targets, including ID2, ODC1 and

MAD2, while concurrently suppressing neuronal differentiation

pathways (35). MYCN exerts potent

anti-apoptotic effects by upregulating the pro-survival proteins

Bcl-2 and MCL-1, and by downregulating TP73, thereby attenuating

the p53 pathway (36).

Epigenetically, MYCN recruits the histone methyltransferase G9a and

histone deacetylases 1 and 2, resulting in elevated histone H3

lysine 9 dimethylation and histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation at

both the ARID3B and MYCN promoters, and consequent transcriptional

silencing of these loci (37).

In vivo evidence was provided by the tyrosine

hydroxylase-MYCN transgenic mouse model, in which restricted

overexpression of MYCN within the sympathetic nervous system alone

was sufficient to induce rapidly fatal NB, thereby establishing

MYCN as a key oncogenic driver in this disease (38). In the present study, RP11-196G11.6

was highly expressed in MYCN-amplified cells, implying a functional

association with MYCN. Previous data have indicated that MYCN can

directly activate the transcription of multiple lncRNAs, such as

CCAT1-L, H19 and HOTAIR (39);

therefore, the elevated expression of RP11-196G11.6 may reflect

direct transcriptional activation by MYCN. Nevertheless, it remains

plausible that MYCN does not bind the RP11-196G11.6 locus directly

but instead induces other transcription factors that indirectly

de-repress or activate RP11-196G11.6 transcription.

Functional experiments in the present study

confirmed that the downregulation of RP11-196G11.6 promoted the

malignant phenotype of MYCN-amplified cells, whereas its

overexpression suppressed the viability, migration and invasion of

non-amplified cells. This result is consistent with previous

studies, which demonstrated that MYCN can drive tumor progression

by directly or indirectly regulating lncRNA expression. For

example, the expression levels of LINC00839 in MYCN-amplified NB

have been shown to be positively correlated with MYCN

amplification, advanced INSS staging and worse prognosis. In in

vitro experiments, silencing LINC00839 was demonstrated to

inhibit cell proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT (40). The results of the present study

suggested that RP11-196G11.6 serves a key regulatory role in the

viability, migration and invasion of NB cells under different MYCN

amplification states.

miR-376a-3p serves a key role in the malignant

progression of several tumors. For example, in acute myeloid

leukemia (AML), miR-376a-3p serves an inhibitory role in AML

progression by targeting the metallothionein-1X gene, increasing

apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation (41). In addition, miR-376a-3p serves a key

role in colorectal cancer (CRC). Titin-antisense RNA1 (TTN-AS1), a

lncRNA, sponges miR-376a-3p, which upregulates the expression of

Krüppel-like factor 15 and promotes the progression of CRC. By

inhibiting miR-376a-3p, TTN-AS1 can increase the proliferation and

invasion of CRC cells (42).

Similarly, in thyroid cancer, miR-376a-3p has been identified to be

inhibitory. The lncRNA LINC00488 regulates the expression of

paraoxonase 2, and promotes the proliferation and migration of

thyroid cancer cells by binding to miR-376a-3p, whereas the

overexpression of miR-376a-3p can inhibit these processes (43). However, in NB, to the best of our

knowledge, there is no clear information regarding the role of

miR-376a-3p. In the present study, it was identified that

miR-376a-3p overexpression promoted SH-SY5Y cell viability,

migration and invasion. Further molecular mechanism studies

revealed that RP11-196G11.6 regulates the activity of its

downstream target gene RYBP by targeting and inhibiting the

expression of miR-376a-3p. The dual luciferase assay results

confirmed the interaction between RP11-196G11.6 and miR-376a-3p,

and revealed that miR-376a-3p was able to directly target the RYBP

gene. Notably, the subsequent experiments revealed that the

overexpression of miR-376a-3p partially reversed the inhibition of

SH-SY5Y cell viability, migration and invasion induced by

RP11-196G11.6 overexpression. These findings imply that

RP11-196G11.6 may regulate the miR-376a-3p/RYBP pathway to inhibit

NB progression.

Notably, CIBERSORT analysis revealed that

RP11-196G11.6 expression was significantly correlated with the

ratio of Tfhs in the tumor microenvironment. The enrichment of

Tregs is often associated with the immunosuppressive

microenvironment and tumor immune escape (44,45),

while Tfhs may influence the antitumor immune response by

modulating B-cell function, which affects the antitumor immune

response (46). Whether

RP11-196G11.6 indirectly regulates immune cell infiltration through

the miR-376a-3p/RYBP axis remains to be further explored. In

addition, aberrant expression of RYBP may affect tumor

cell-microenvironment interactions through epigenetic

reprogramming, which provides a potential direction for future

studies.

RYBP has been reported to inhibit cell

proliferation, migration and invasion in a variety of tumors, in

particular by regulating the EGFR signaling pathway (47,48).

In lung cancer studies, RYBP suppresses tumor progression and

metastasis by inhibiting EGFR signaling and EMT. As core EMT

markers, vimentin and E-cadherin are key in tumor biology, where

EMT enables cancer cells to acquire migratory, invasive and

metastatic properties (49).

E-cadherin, as a key epithelial cell adhesion molecule, is often

markedly downregulated or absent during the EMT process, leading to

the dissociation of intercellular junction structures, thus making

tumor cells more likely to detach from the primary site and enter a

migratory and invasive state (50).

By contrast, vimentin, a mesenchymal cytoskeletal protein, is

markedly upregulated during the EMT process. This change helps

enhance the motility and morphological plasticity of cells, thereby

promoting their invasive and metastatic potential (51). Particularly, overexpression of RYBP

has been shown to reduce the phosphorylation level of EGFR and its

downstream signaling molecules, thereby inhibiting cell

proliferation and migration (52).

In addition, RYBP expression has been identified to be negatively

associated with tumor invasiveness, and to inhibit tumor cell

proliferation and migration by suppressing the EGFR signaling

pathway. These results implied that by controlling the EGFR

signaling pathway, RYBP may have an inhibitory effect on a range of

malignancies (53). The findings of

the present study demonstrated that RP11-196G11.6 overexpression

blocked the EGFR pathway and increased RYBP expression.

Overexpression of RP11-196G11.6 suppressed vimentin protein

expression and promoted E-cadherin protein expression. These

findings suggest that by influencing the EGFR pathway and mediating

EMT, the RP11-196G11.6/miR-376a-3p/RYBP axis may have an impact on

the invasive metastasis of NB tumors.

Although the present study initially elucidated the

function and mechanism of RP11-196G11.6, certain limitations still

exist. The present study lacked the validation of clinical data and

animal models, and was based on cell line models. Therefore,

further external validation methods should be performed in the

future. Second, it remains unclear as to whether RP11-196G11.6 is

directly regulated by MYCN transcription and this requires further

experimental verification. Lastly, whether RYBP inhibits the

progression of NB by suppressing the EGFR signaling pathway still

requires in-depth analysis. In addition, the role of RP11-196G11.6

in the prognosis of NB with MYCN amplification will be explored in

future studies, with the aim of identifying additional potential

markers for prognostic assessment.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the

present study was the first to demonstrate the key function of

RP11-196G11.6 in NB. Through the regulation of miR-376a-3p and its

target gene RYBP, RP11-196G11.6 may promote apoptosis, and inhibit

NB cell viability, migration and invasion. Therefore, RP11-196G11.6

could potentially be a novel target for therapeutic intervention in

NB.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported in part by the Key Project of

the National Key R&D Plan ‘Research on Prevention and Control

of Major Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases’, the Ministry of

Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (grant

nos. 2018YFC1313000 and 2018YFC1313004).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JZha was responsible for the overall conception and

design of the present study and wrote the manuscript. KH and JZho

performed most of the experiments and the data analysis. WL and FL

collected the data. ZZ reviewed and revised the manuscript, and

performed the bioinformatics analyses, including figure generation

and statistical analysis. SW prepared research ideas, obtained

funding and revised the manuscript, and was responsible for

interpretation of the experimental findings and statistical

analysis. JZHa and KH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethical

Committee of Guizhou Provincial People's Hospital (approval no.

2025-104; Guizhou, China) and written informed consent was obtained

from the parents of all participants before enrollment in the

present study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Irwin MS and Park JR: Neuroblastoma:

Paradigm for precision medicine. Pediatr Clin North Am. 62:225–256.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Suh E, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, Nathan

PC, Ford JS, Freyer DR, McNeer JL, Stock W, Stovall M, Krull KR, et

al: Late mortality chronic health conditions in long-term survivors

of early-adolescent, young adult cancers: A retrospective cohort

analysis from the childhood cancer survivor study. Lancet Oncol.

21:421–435. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ponzoni M, Bachetti T, Corrias MV,

Brignole C, Pastorino F, Calarco E, Bensa V, Giusto E, Ceccherini I

and Perri P: Recent advances in the developmental origin of

neuroblastoma: An overview. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:922022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Körber V, Stainczyk SA, Kurilov R, Henrich

KO, Hero B, Brors B, Westermann F and Höfer T: Neuroblastoma arises

in early fetal development and its evolutionary duration predicts

outcome. Nat Genet. 55:619–630. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Monclair T, Brodeur GM, Ambros PF, Brisse

HJ, Cecchetto G, Holmes K, Kaneko M, London WB, Matthay KK,

Nuchtern JG, et al: The international neuroblastoma risk group

(INRG) staging system: An INRG task force report. J Clin Oncol.

27:298–303. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Castel V, García-Miguel P, Cañete A,

Melero C, Navajas A, Ruíz-Jiménez JI, Navarro S and Badal MD:

Prospective evaluation of the international neuroblastoma staging

system (INSS) and the international neuroblastoma response criteria

(INRC) in a multicentre setting. Eur J Cancer. 35:606–611. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shimada H, Ambros IM, Dehner LP, Hata J,

Joshi VV, Roald B, Stram DO, Gerbing RB, Lukens JN, Matthay KK and

Castleberry RP: The international neuroblastoma pathology

classification (the Shimada system). Cancer. 86:364–372. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pinto NR, Applebaum MA, Volchenboum SL,

Matthay KK, London WB, Ambros PF, Nakagawara A, Berthold F,

Schleiermacher G, Park JR, et al: Advances in risk classification

and treatment strategies for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol.

33:3008–3017. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries

LAG, Moreno F, Dolya A, Bray F, Hesseling P, Shin HY and Stiller

CA: IICC-3 contributors: International incidence of childhood

cancer, 2001-10: A population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol.

18:719–731. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Diede SJ: Spontaneous regression of

metastatic cancer: Learning from neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Cancer.

14:71–72. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, Varmus HE

and Bishop JM: Amplification of N-myc in untreated human

neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science.

224:1121–1124. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ruiz-Pérez MV, Henley AB and

Arsenian-Henriksson M: The MYCN protein in health and disease.

Genes (Basel). 8:1132017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Huang M and Weiss WA: Neuroblastoma and

MYCN. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 3:a0144152013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Taniue K and Akimitsu N: The functions and

unique features of LncRNAs in cancer development and tumorigenesis.

Int J Mol Sci. 22:6322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang R, Liu N, Li T, Liu F, Zhang J, Zhao

H, Zou L and He X: LncRNA AC142119.1 facilitates the progression of

neuroblastoma by epigenetically initiating the transcription of

MYCN. J Transl Med. 21:6592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hsu CL, Yin CF, Chang YW, Fan YC, Lin SH,

Wu YC, Huang HC and Juan HF: LncRNA SNHG1 regulates neuroblastoma

cell fate via interactions with HDAC1/2. Cell Death Dis.

13:8092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hu Z, Xu W, Wang H, Li M, Wang J, Sun C

and Yang X: CARM1-induced lncRNA NEAT1 synchronously activates MYCN

and GalNAcT-I to accelerate the progression of neuroblastoma. Gene.

938:1491642025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H,

Kelley R and Salzberg SL: TopHat2: Accurate alignment of

transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene

fusions. Genome Biol. 14:R362013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ and Smyth GK:

edgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis

of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26:139–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu S, Wang Z, Chen D, Zhang B, Tian RR,

Wu J, Zhang Y, Xu K, Yang LM, Cheng C, et al: Annotation and

cluster analysis of spatiotemporal- and sex-related lncRNA

expression in rhesus macaque brain. Genome Res. 27:1608–1620. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G,

Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL and Pachter L:

Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq

experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 7:562–578. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sturm G, Finotello F and List M:

Immunedeconv: An R package for unified access to computational

methods for estimating immune cell fractions from bulk

RNA-sequencing data. Methods Mol Biol. 2120:223–232. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Langfelder P and Horvath S: WGCNA: An R

package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC

Bioinformatics. 9:5592008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xie C, Mao X, Huang J, Ding Y, Wu J, Dong

S, Kong L, Gao G, Li CY and Wei L: KOBAS 2.0: A web server for

annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases.

Nucleic Acids Res. 39((Web Server Issue)): W316–W322. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tan K, Zhang X, Cong X, Huang B, Chen H

and Chen D: Tumor suppressor RYBP harbors three nuclear

localization signals and its cytoplasm-located mutant exerts more

potent anti-cancer activities than corresponding wild type. Cell

Signal. 29:127–137. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhu X, Yan M, Luo W, Liu W, Ren Y, Bei C,

Tang G, Chen R and Tan S: Expression and clinical significance of

PcG-associated protein RYBP in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol

Lett. 13:141–150. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Morinaka T, Sakai N, Takayashiki T, Kuboki

S, Takano S, Ohira G, Matsubara H and Ohtsuka M: RYBP contributes

to improved prognosis in colorectal cancer via regulation of cell

cycle, apoptosis and oxaliplatin sensitivity. Int J Oncol.

63:1202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zafar A, Wang W, Liu G, Wang X, Xian W,

McKeon F, Foster J, Zhou J and Zhang R: Molecular targeting

therapies for neuroblastoma: Progress and challenges. Med Res Rev.

41:961–1021. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Qiu B and Matthay KK: Advancing therapy

for neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:515–533. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Floros KV, Cai J, Jacob S, Kurupi R,

Fairchild CK, Shende M, Coon CM, Powell KM, Belvin BR, Hu B, et al:

MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma is addicted to iron and vulnerable to

inhibition of the system Xc-/glutathione axis. Cancer Res.

81:1896–1908. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vaid R, Thombare K, Mendez A,

Burgos-Panadero R, Djos A, Jachimowicz D, Lundberg KI, Bartenhagen

C, Kumar N, Tümmler C, et al: METTL3 drives telomere targeting of

TERRA lncRNA through m6A-dependent R-loop formation: A therapeutic

target for ALT-positive neuroblastoma. Nucleic Acids Res.

52:2648–2671. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Heward JA and Lindsay MA: Long non-coding

RNAs in the regulation of the immune response. Trends Immunol.

35:408–419. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Otte J, Dyberg C, Pepich A and Johnsen JI:

MYCN function in neuroblastoma development. Front Oncol.

10:6240792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Braoudaki M, Hatziagapiou K, Zaravinos A

and Lambrou GI: MYCN in neuroblastoma: ‘Old wine into new

wineskins’. Diseases. 78:782021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Chen L and Tweddle DA: p53, SKP2, and DKK3

as MYCN target genes and their potential therapeutic significance.

Front Oncol. 28:1732012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kobayashi K, Jakt LM and Nishikawa SI:

Epigenetic regulation of the neuroblastoma genes, Arid3b and Mycn.

Oncogene. 32:2640–2648. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Weiss WA, Aldape K, Mohapatra G,

Feuerstein BG and Bishop JM: Targeted expression of MYCN causes

neuroblastoma in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 16:2985–1995. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Winkle M, van den Berg A, Tayari M,

Sietzema J, Terpstra M, Kortman G, de Jong D, Visser L, Diepstra A,

Kok K and Kluiver J: Long noncoding RNAs as a novel component of

the Myc transcriptional network. FASEB J. 29:2338–2346. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang Q, Wei J, Li N and Liu B: LINC00839

promotes neuroblastoma progression by sponging miR-454-3p to

Up-regulate NEUROD1. Neurochem Res. 47:2278–2293. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Xin X, Xu Z, Wei J and Zhang Y:

MiR-376a-3p increases cell apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia by

targeting MT1X. Cancer Biol Ther. 23:234–242. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang Y, Jiang F, Xiong Y, Cheng X, Qiu Z

and Song R: LncRNA TTN-AS1 sponges miR-376a-3p to promote

colorectal cancer progression via upregulating KLF15. Life Sci.

244:1169362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Xie F, Li L, Luo Y, Chen R and Mei J: Long

non-coding RNA LINC00488 facilitates thyroid cancer cell

progression through miR-376a-3p/PON2. Biosci Rep.

41:BSR202016032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Shan F, Somasundaram A, Bruno TC, Workman

CJ and Vignali DAA: Therapeutic targeting of regulatory T cells in

cancer. Trends Cancer. 8:944–961. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yan S, Zhang Y and Sun B: The function and

potential drug targets of tumour-associated Tregs for cancer

immunotherapy. Sci China Life Sci. 62:179:1862019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Overacre-Delgoffe AE, Bumgarner HJ, Cillo

AR, Burr AHP, Tometich JT, Bhattacharjee A, Bruno TC, Vignali DAA

and Hand TW: Microbiota-specific T follicular helper cells drive

tertiary lymphoid structures and anti-tumor immunity against

colorectal cancer. Immunity. 54:2812–2824.e4. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhou H, Li J, Zhang Z, Ye R, Shao N,

Cheang T and Wang S: RING1 and YY1 binding protein suppresses

breast cancer growth and metastasis. Int J Oncol. 49:2442–2452.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Xian Y, Wang L, Yao B, Yang W, Mo H, Zhang

L and Tu K: MicroRNA-769-5p contributes to the proliferation,

migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by

attenuating RYBP. Biomed Pharmacother. 118:1093432019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ganesan K, Xu C, Wu S, Sui Y, Du B, Zhang

J, Gao F, Chen J and Tang H: Ononin inhibits tumor bone metastasis

and osteoclastogenesis by targeting mitogen-activated protein

kinase pathway in breast cancer. Research (Wash D C).

7:05532024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zeng Y, Du W, Huang Z, Wu S, Ou X, Zhang

J, Peng C, Sun X and Tang H: Hsa_circ_0060467 promotes breast

cancer liver metastasis by complexing with eIF4A3 and sponging

miR-1205. Cell Death Discov. 9:1532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Han M, Yang J, Chen P, Li S, Tang H, Fan

H, Wang Y, Li X, Pan W, Koutouratsas V, et al: Isocucurbitacin B

inhibits gliomas through the promotion of anoikis by targeting

caveolin 1. Cancer Lett. 629:2178732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Dinglin X, Ding L, Li Q, Liu Y, Zhang J

and Yao H: RYBP inhibits progression and metastasis of lung cancer

by suppressing EGFR signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition. Transl Oncol. 10:280–287. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Tong AH, Tan J, Zhang JH, Xu FJ, Li FY and

Cao CY: Overexpression of RYBP inhibits proliferation, invasion,

and chemoresistance to cisplatin in anaplastic thyroid cancer cells

via the EGFR pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 33:e222412019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|