Introduction

Temporal bone malignant tumors are rare and

represent a small proportion (0.2%) of head and neck malignancies,

with an approximate annual incidence rate of 1–6 cases per million

individuals (1,2). Temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma

is the most common malignant tumor in this area, representing 80%

of all malignancies (2). The

remaining cases include adenoid cystic carcinoma and other rare

pathologies, such as sarcoma. The tumors can be primary (from the

external/middle ear) or secondary (from adjacent sites such as the

periauricular skin or parotid gland) and are chiefly diagnosed in

patients beyond the age of 60 years (3). These tumors often present with

non-specific symptoms such as otorrhea, otalgia, tinnitus, hearing

loss, and occasionally, facial paralysis, making early diagnosis

challenging. By the time a definitive diagnosis is made, the

disease tends to have expanded to a large extent, frequently

invading adjacent nerves, blood vessels and other vital organs

(1).

The persistent tissue injury stemming from ongoing

otitis media and external otitis is a predominant risk factor,

which serves as the primary mechanism driving the carcinogenesis of

temporal bone malignancies (4–6). Other

risk factors include exposure to ultraviolet radiation and prior

radiotherapy (RT), older age and immunodeficiency (7). Surgical resection is the mainstay of

curative treatment, typically in the form of temporal bone

resection with or without RT (8,9).

Despite multidisciplinary treatment, the prognosis

of temporal bone malignancies remains poor. The rarity of the

disease has impeded the collection of evidence from both clinical

and basic research, and there is currently no unified staging

system. The present retrospective analysis aimed to evaluate the

management strategies, survival outcomes and possible adverse

features of patients with temporal bone malignancies treated at

Beijing Tiantan Hospital (Beijing, China).

Materials and methods

Patient population

Patients with pathologically confirmed temporal bone

malignancies treated at Beijing Tiantan Hospital between March 2014

and March 2022 were retrospectively included in the current study.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan

Hospital (approval no. 2022-255-01) and was carried out in

accordance with the principles of The Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had any of the

following: A prior carcinoma in another organ, metastatic disease,

a periauricular skin or parotid gland origin, or incomplete

treatment records. All patients routinely underwent parotid and

cervical lymph node ultrasound, and temporal bone computed

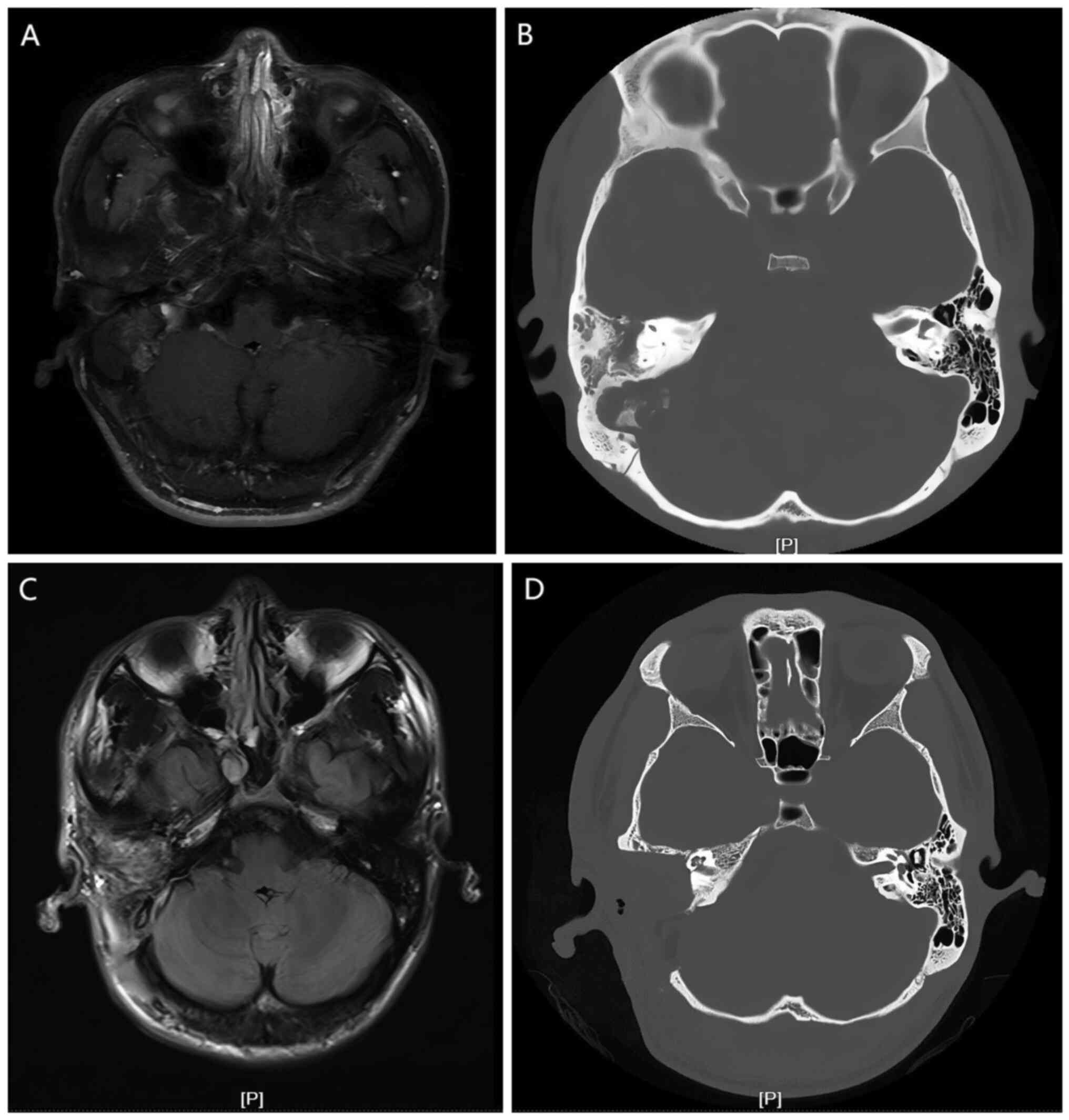

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1) examinations to determine the

extent of lesions and bone destruction, and the presence of

intracranial invasion before surgery. Positron emission tomography

was conducted in selected cases. Facial nerve function was

evaluated using the House-Brackmann (HB) grading system (10). Patients with squamous cell carcinoma

(SCC) and adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) were staged according to

the revised Pittsburgh classification system (11).

Treatment strategy

The surgical methods mainly included lateral

temporal bone resection (LTBR) and subtotal temporal bone resection

(STBR). For patients with involvement of the lateral skull base,

the infratemporal fossa approach was used to remove the tumor. The

facial nerve was preserved as much as possible, unless it was

infiltrated by the tumor and could not be separated. Parotidectomy

and neck dissection were performed if clinically indicated, and the

temporomandibular joint was resected to achieve complete excision

of the tumor when necessary. Surgical margins were determined based

on postoperative pathological examination for patients with lateral

temporal bone resection applied. A clear margin was defined as a

distance of ≥5 mm from the invasive tumor front. However, since

early symptoms of malignant temporal bone tumors are often

non-specific, most patients presented with advanced disease at the

time of treatment. In such cases, subtotal temporal bone resection

rarely allows for en bloc excision. After tumor resection, an

otological drill is used to remove the diseased bone tissue, which

is not included in the histological examination. Therefore, margin

assessment requires a comprehensive evaluation that integrates

postoperative paraffin-section pathology with intraoperative

findings. Regular follow-up was routinely conducted every 3 months

for the first 3 years, every 6 months for years 4 and 5, and once a

year thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM

Corp.). The survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier

method. A log-rank test was employed to compare the differences in

patient survival between groups. Survival analysis was confined to

univariate comparisons with the log-rank test, as the sample size

was too small for a reliable multivariate analysis. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical data

In the group of 20 patients, there were 16 men and 4

women, aged between 9 and 90 years, with a mean age of 50.8 years.

The duration of illness varied from 1 month to 40 years. According

to the revised Pittsburgh classification system (11), 1 patient presented with a T1 tumor,

5 patients with T3 tumors and 8 patients with T4 tumors, among the

14 patients diagnosed with SCC and ACC. The follow-up period ranged

from 1 to 140 months, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up (5%). The

clinical symptoms mainly included hearing loss (n=15, 75%), otalgia

(n=13, 65%), chronic ear discharge (n=8, 40%), headaches (n=6,

30%), facial paralysis (n=5, 25%), dizziness (n=5, 25%) and

tinnitus (n=5, 25%). Regarding HB facial paralysis, 1 case

presented as grade II, 2 cases presented as grade V and 2 cases

presented as grade VI. A single case had previously undergone

surgery for chronic otitis media. Table

I summarizes the patient demographics, tumor characteristics

and survival outcomes.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of temporal

carcinoma (n=20). |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of temporal

carcinoma (n=20).

| Patient no. | Pittsburgh stage | Age, years | Sex | Symptoms | Treatment | Pathology | Follow-up status

and survival time (months) |

|---|

| 1 | T3 | 56 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, otalgia and headache | STBR | SCC | DOD (37) |

| 2 | T4 | 59 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, ear bleeding, otalgia and facioplegia | STBR + CRT | SCC | DM (24); A (74) |

| 3 | T4 | 64 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, otalgia, headache, dizziness and limited mouth

opening | STBR + RT | SCC | DOD (10) |

| 4 | T4 | 59 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, otalgia, ear bleeding and tinnitus | STBR | SCC | DOD (8) |

| 5 | T1 | 56 | M | Headache | LTBR | ACC | A (54) |

| 6 | T3 | 56 | M | Otalgia | STBR + RT | ACC | A (54) |

| 7 | T4 | 76 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, otalgia and tinnitus | STBR | ACC | A (73) |

| 8 | / | 53 | F | Hearing loss and

headache | LTBR (1st

treatment), STBR + END + RT (2nd treatment) | ACC | LR (64); A

(140) |

| 9 | T4 | 65 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, otalgia and dizziness | ITF+RT | SCC | A (85) |

| 10 | T4 | 43 | M | Hearing loss and

limited mouth opening | STBR+RT | ACC | A (64) |

| 11 | / | 33 | F | Otalgia | LTBR (1st

treatment), STBR + CRT (2nd treatment) | ACC | LR (61); DOD

(70) |

| 12 | T3 | 33 | M | Hearing loss,

otorrhea, otalgia, facioplegia, tinnitus and dizziness | STBR + CRT | SCC | LFU |

| 13 | / | 54 | M | Vision loss,

headache, dizziness and hearing loss | STBR + RT | Fibrosarcoma | A (56) |

| 14 | / | 28 | M | Facioplegia and

mass | ITF | Chondrosarcoma | A (104) |

| 15 | / | 56 | M | Ear stuffy, hearing

loss, otorrhea, tinnitus and ear bleeding | STBR + CRT (1st

treatment), ITF (2nd treatment) | Endolymphatic

cystic papillary adenocarcinoma | LR (11); DWD (65) |

| 16 | / | 39 | M | Facioplegia,

otalgia, hearing loss and tinnitus | STBR (1st

treatment), ITF (2nd treatment) | Chondrosarcoma | LR (62); A

(140) |

| 17 | / | 9 | F | Headache, dizziness

and facioplegia | ITF |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | DOD (1) |

| 18 | / | 18 | M | Hearing loss and

otalgia | ITF + RT | LMPNST | LR (8); DOD (16) |

| 19 | T4 | 36 | M | Hearing loss and

otalgia | LTBR + RT (1st

treatment), STBR (2nd treatment) | ACC | LR (26); A (54) |

| 20 | T4 | 90 | M | Hearing loss and

otalgia | STBR | SCC | DWD (16) |

Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis in

all 20 cases, with 7 patients diagnosed with SCC, 7 with ACC, 2

with chondrosarcoma, 1 with fibrosarcoma, 1 with endolymphatic

cystic papillary adenocarcinoma, 1 with rhabdomyosarcoma and 1 with

a low-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

Treatment

Among the 20 cases, as the first treatment, 10

underwent surgical excision only, 7 received surgery and RT, and 3

underwent surgery combined with chemoradiotherapy (CRT). RT with a

dose of 60–66 Gy in 30–33 fractions at 1.8–2 Gy per fraction was

administrated postoperatively for patients with an advanced tumor

or positive margin. Additional concurrent weekly cisplatin

chemotherapy (30–40 mg/m2) was administered in patients

with positive margins. For patients unsuitable to receive

cisplatin, either carboplatin or RT alone was used. A total of 4

cases underwent LTBR, 12 cases received STBR and 4 cases received

lateral skull base tumor resection via the infratemporal fossa

approach (Table I).

A parotidectomy was conducted in 8 patients, of

which 5 were pathologically confirmed with tumor invasion. A

partial temporomandibular joint cyst resection was performed in 8

patients, with tumor invasion in 4 patients. The facial nerve was

involved in 9 cases, among which the tumor was resected while

preserving the facial nerve in 3 patients. All 3 patients appeared

with varying degrees of facial nerve paralysis after surgery

(Table II).

| Table II.Structures found to be invaded by the

tumor during surgery. |

Table II.

Structures found to be invaded by the

tumor during surgery.

|

|

Patient

no. |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Operative

details | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|

| SP/pathology

confirmed invasion | -/- | +/+ | +/- | +/+ | -/- | -/- | +/+ | -/- | +/- | +/+ | +/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | +/+ | -/- |

| TMJ

resection/pathology confirmed invasion | -/- | +/+ | +/+ | +/- | -/- | -/- | +/- | -/- | +/- | +/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | +/+ | +/+ |

| Posterior cranial

fossa meningeal involvement | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| Medial cranial

fossa meningeal involvement | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| Facial nerve

invasion/resection | -/- | +/+ | -/- | +/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- | +/- | +/+ | -/- | -/- | -/- | +/+ | +/- | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | -/- | -/- |

The tumor involved the cranial fossa meninges in 9

cases, including 5 cases of medial cranial fossa meninges

involvement, 1 case of post cranial fossa meninges involvement and

3 cases of both, among which tumors were resected while preserving

the integrity of the meninges without evident cerebrospinal fluid

leakage in 8 cases. In the remaining case, the tumor and affected

dura were excised, and repair was performed using the artificial

dura mater interposition method. The tumor invaded the cochlea and

penetrated deep into the skull in 1 case, and cerebrospinal fluid

leakage occurred after tumor resection. This was managed by

utilizing free fat grafting to fill the cavity, along with temporal

muscle flap reinforcement.

Follow-up results

The 3- and 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS)

rates were 79 and 73%, and the 3- and 5-year overall survival (OS)

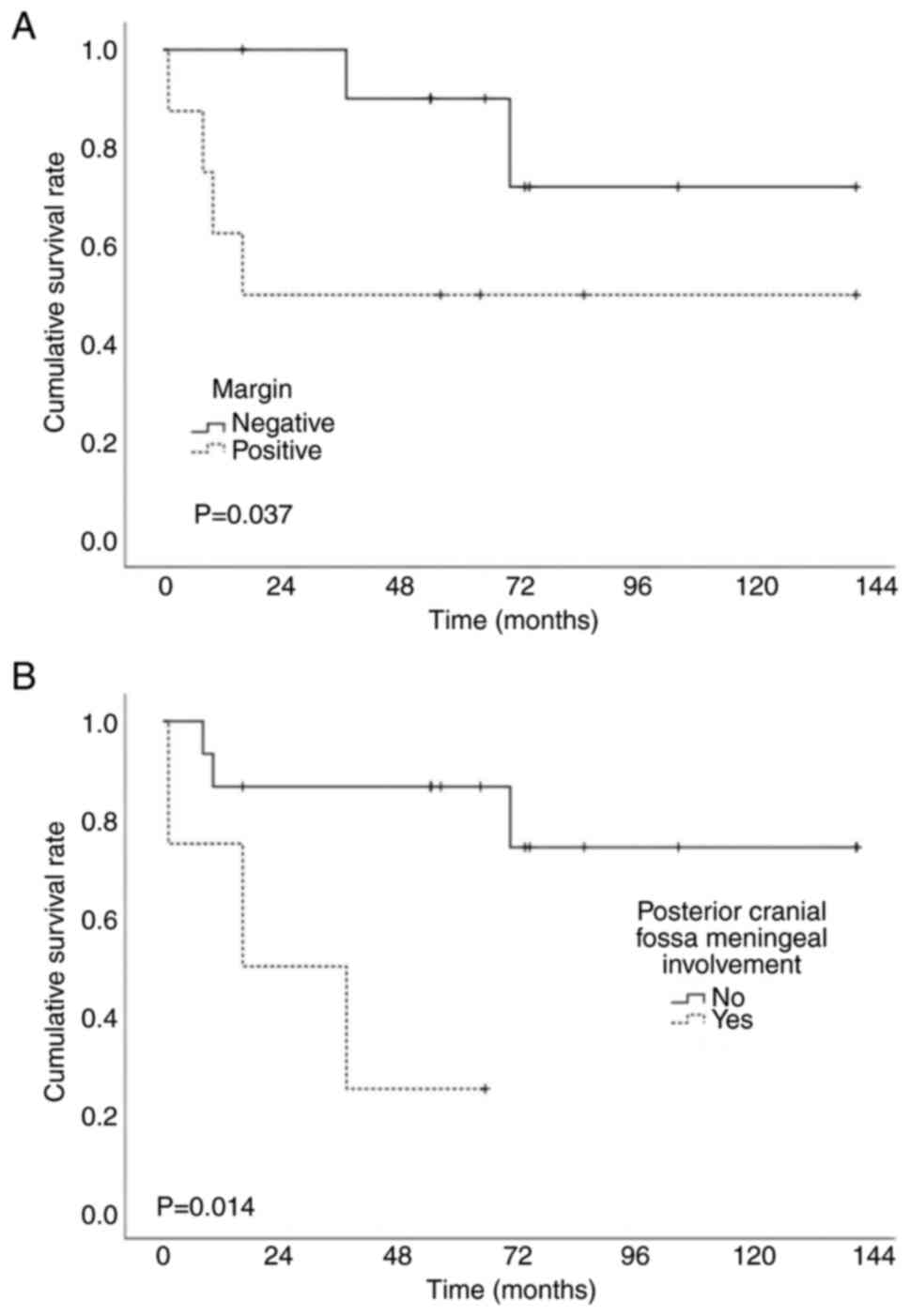

rates were 74 and 68%. Univariate analysis (Table III) results indicated that the

pathological type (both P<0.001) and posterior cranial fossa

meningeal involvement (P=0.005 and P=0.014, respectively) were

significantly associated with OS and DSS. Patients with a positive

surgical margin tended to have worse DSS (P=0.037) (Fig. 2). Due to the limited sample size,

further multivariate survival analysis was not conducted.

| Table III.Variables associated with survival

(univariate analysis by log-rank test). |

Table III.

Variables associated with survival

(univariate analysis by log-rank test).

| Variables | Ovall survival

P-value | Disease-specific

survival P-value |

|---|

| Sex

(male/female) | 0.301 | 0.442 |

| Age (≤55/>55

years) | 0.492 | 0.974 |

| Facial paralysis

(yes/no) | 0.421 | 0.703 |

| Medial cranial

fossa meningeal involvement (yes/no) | 0.369 | 0.121 |

| Posterior cranial

fossa meningeal involvement (yes/no) | 0.005 | 0.014 |

| Parotid gland/TMJ

involvement (yes/no) | 0.428 | 0.265 |

| T stage

(T4/T1-3) | 0.888 | 0.762 |

| Margin

(positive/negative) | 0.287 | 0.037a |

| Histology

(SCC/ACC/FSa/CS/ELST/RMS/LMPNST) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treatment modality

(surgery/surgery + RT/CRT) | 0.630 | 0.513 |

Among the 14 patients diagnosed with ACC and SCC, 3

patients experienced local recurrence and underwent a second

surgery. A single patient with ACC died of disease at 70 months,

while another 2 patients with ACC were alive at 54 and 140 months

of follow-up. Only 1 out of the 14 patients had distant metastasis

to the lung at 24 months, and this patient received CRT and was

alive at 74 months. Another 3 patients died of the disease, at 8,

10 and 37 months postoperatively. A single patient died of

pulmonary infection at 16 months without evidence of disease.

Another patient diagnosed with a T3 tumor failed to be followed up

for unknown reason after receiving surgery and CRT. A further 5

patients survived without showing signs of disease at a mean of 66

months of follow-up (range, 54–85 months) (Table I).

Among the 6 patients with rare temporal bone

malignancies, 3 underwent lateral skull base tumor resection via

the infratemporal fossa approach and 2 experienced local relapse. A

single patient with a low-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumor died of disease at 16 months, while another patient with

endolymphatic cystic papillary adenocarcinoma died of glioma at 65

months. In addition, 1 patient with chondrosarcoma was alive at 140

months. Another 9-year-old child with rhabdomyosarcoma underwent

incomplete resection due to internal carotid artery invasion and

died of disease soon after the surgery. Furthermore, 2 patients

were alive at 56 and 104 months of follow-up.

Discussion

The present study conducted a thorough examination

of the survival rates and possible factors influencing the

prognosis for patients diagnosed with temporal bone malignancies at

Beijing Tiantan Hospital. The findings confirmed that the

pathological type and the presence of positive surgical margins may

be significant prognostic indicators of patients with temporal bone

malignancies.

At present, the International Union Against Cancer

and the American Joint Committee on Cancer have not proposed

staging criteria specifically for temporal bone malignancies. The

modified Pittsburgh staging criteria (11) is widely accepted for patients with

SCC of the temporal bone. However, Nabuurs et al (12) recruited 381 patients to assess the

prognostic predictive value of the modified Pittsburgh staging

system and demonstrated that T4 tumors with different directions of

invasion (anterior, posterior, superior, inferior, medial or

lateral) had different prognoses, but the staging system did not

distinguish between different directions of invasion of T4 tumors.

Zanoletti et al (13)

reported a hazard ratio of 1.13 (95% confidence interval,

0.98–1.32; P=0.089) for patients with tumors spreading in other

directions compared with patients with T4 external auditory canal

SCC tumors spreading anteriorly (preauricular region and parotid

space). Similarly, the results of the present study suggested that

patients with posterior cranial fossa meningeal involvement had a

worse prognosis. Patients without posterior cranial fossa disease

involvement had significantly superior 5-year OS and DSS rates of

80 and 87%, respectively, compared with those with involvement

(both 25%). Additionally, Zanoletti et al (13) built a new staging system based on

the modified Pittsburgh staging criteria combined with additional

T4 tumor prognostic factors, such as dural involvement, the

direction of invasion and histological grading. This new standard

was used to evaluate the prognosis of 44 cases of SCC of the

temporal bone, as well as other case series from different studies.

The results indicated that the new staging standard not only had

better prognostic predictive effects than the modified Pittsburgh

staging criteria, but also demonstrated good applicability

(13,14). Moreover, as demonstrated in the

present study, there are other types of temporal bone malignancies,

including ACC and other rare types, and more research is needed to

refine a staging system of temporal bone malignancies.

Depending on the area of tumor invasion, the

surgical approaches for temporal osteotomy include LTBR (resection

of the ear canal and tympanic membrane), STBR (resection of the

labyrinth/cochlea and internal auditory canal) and total temporal

bone resection (TTBR; resection of the petrous apex) (15). Typically, LTBR is recognized as a

preferred treatment for early-stage (T1-2) carcinoma, dispensing

with the need for postoperative RT, provided that the surgical

margins are clear of disease (15–19).

For advanced-stage tumors, treatment for the majority of patients

involves STBR with adjuvant RT, and occasionally, chemotherapy

(20). TTBR is now rarely used due

to associated surgical complications and lower survival rates

without an improvement in prognosis when compared with STBR plus

adjuvant therapy (16). In the

present study, 12 patients received STBR, 4 underwent LTBR, and 4

received lateral skull base tumor resection via the infratemporal

fossa approach.

The lymph node metastasis rate of temporal

malignancies is relatively low (21,22).

Neck dissection is undertaken mainly for patients exhibiting

radiographic or clinical signs of cervical lymph node involvement.

In the present group of patients, with the exception of 2 patients

who underwent parotid and postauricular lymph node excision with

negative pathology, no patient underwent an elective regional neck

dissection. Moreover, no local lymph node recurrence was observed

in any patient during the follow-up period. There is still

considerable debate over whether patients with malignant tumors of

the temporal bone should routinely undergo parotidectomy (23,24).

Currently, a parotidectomy is performed in cases with notable

involvement of the parotid gland or suspicion of facial nerve

invasion, and it is also utilized in specific cases to achieve

negative margins. In the present study, a parotidectomy was

conducted in 8 patients, and in 5 of these cases, tumor invasion

was confirmed pathologically.

In terms of functionality, the goal when treating

temporal bone malignancies is to completely remove the tumor with

negative margin while preserving the integrity of the facial nerve

as much as possible. However, temporal bone malignancies are often

covert, and by the time they are diagnosed, the extent of the

disease can be quite high. Compared with LTBR, STBR often requires

consideration as to whether to preserve or sacrifice the facial

nerve, and it may be necessary to sacrifice it. Since malignant

tumors of the external auditory canal and middle ear have a high

degree of malignancy and pose a threat to life, the focus is on

completely removing the lesion and extending survival, rather than

emphasizing the preservation of hearing. In the present group of

patients, the facial nerve was resected in 6 cases, and the tumor

was peeled off the surface of the facial nerve in 3 cases. All

patients had varying degrees of hearing loss after surgery.

Surgery combined with postoperative supplementary RT

is an effective intervention for controlling temporal bone tumors,

even though ACC and tumors of mesenchymal origin are not

particularly sensitive to RT (25–28).

Generally, RT is applied postoperatively for advanced/recurrent

disease, as well as for individuals exhibiting positive surgical

margins, lymph node metastasis, nerve invasion and extracapsular

spread. However, definitive CRT is emerging as a primary treatment

for advanced or unresectable disease. Morita et al (19) observed comparable 5-year OS rates

among patients with T3-4 tumors who underwent definitive CRT

(52.1%) in contrast to patients who received surgery followed by

postoperative RT, with or without chemotherapy (55.6%).

Limited research shows that molecular-targeting

agents, such as cetuximab and isocitrate dehydrogenase 1

inhibitors, exhibit promising antitumor activity in patients with

advanced temporal bone malignancies (29,30).

Additionally, Yan and Sui (31)

reported the long-term survival of a 47-year-old man with

uncontrolled locally advanced temporal bone SCC after immunotherapy

followed by CRT. Addressing these challenges will lead to improved

prognosis for patients with unresectable, residual, or recurrent

temporal bone malignancies.

The 5-year OS rate has been reported to vary in

different studies, ranging from 51.7 to 66.8% (6,32–34),

while the DSS rate for patients with T1 and T2 temporal bone tumors

has been shown to range from 92 to 100%, compared with 48 to 65%

for those with T3 and T4 tumors (21). The majority of patients included in

the present study presented as advanced and recurrent cases, and

the 5-year DSS and OS rates were 73 and 68%, respectively.

A positive margin is often considered a poor

prognostic factor (20,35), as reported in the present study. The

5-year DSS rates of patients with negative and positive margins

were 89 and 50%, respectively. However, what should be noted is

that the correct judgment of tumor margins must take into account

both histological examinations and surgical records, distinguishing

between ‘false-positives’ and ‘true-positives’ due to piecemeal

resection. Other reported factors associated with a poor prognosis

include clinical facial nerve palsy at presentation and advanced

stage disease (11,36–39).

However, a recent multivariate analysis revealed the sole poor

prognostic indicator with statistical significance was surgery on

patients with recurrent disease (2). Dean et al (40) also found no difference between local

control rates for cases that required facial nerve resection

(67.6%) compared with those that did not (76.9%) (P=0.13), a

finding that aligns with the results of the current study.

Manolidis et al (41) noted

that tumors of mesenchymal origin were generally less invasive and

tended to exhibit better local control rates in comparison to other

types of malignancies. Similar results were observed in the present

study, since pathological type statistically affected prognosis

(P<0.001). Notably, the SCC pathological type was associated

with worse OS and DSS rates compared with the ACC (P=0.028

and P=0.073, respectively). However, given the small number

of patients with other pathological types, interpretation of the

prognostic data requires caution.

The present study has some limitations. Owing to the

rarity of temporal bone malignancies, conducting large-scale

prospective studies within a single institution has been

challenging. Thus, the present study is a single-centre

retrospective case series, which may have potential selection bias.

The small sample size precluded statistical analysis of several

adverse features and further multivariable survival analysis to

rule out the influence of confounding factors. Multicenter

collaboration is warranted to validate these findings in a larger,

more diverse cohort. In addition, the retrospective study design

relied on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which

may result in potential information bias. Moreover, with the

progression of technology, surgical techniques and adjuvant

treatment strategies, it may be challenging to compare treatment

results with those from other studies and to determine the optimal

therapeutic approach.

In conclusion, temporal bone malignancies are rare

and are associated with a poor prognosis. Factors predictive of

poor survival outcomes include SCC pathology, a positive surgical

margin and posterior cranial fossa meningeal involvement. Treatment

is complex, and surgery combined with RT/CRT is currently the main

effective treatment plan. Nevertheless, further multi-institutional

prospective investigations are required to specify the biological

behavior of temporal malignancies, and to identify unified staging

and optimal treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

All authors had full access to the data in the study

and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the

accuracy of the data analysis. LG and YX were responsible for

conceptualization. LG and RG were responsible for the methodology.

Study investigation was performed by LG and TY. Formal data

analysis and interpretation was performed by LG, TY, RG and WZ. The

original draft was written by LG. YX and RG reviewed and revised

the manuscript. RG supervised the study. Data curation was the

responsibility of LG and TY. Project administration was performed

by RG, and validation was performed by YX and RG. LG and YX confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Beijing Tiantan Hospital (Beijing, China; approval no.

2022-255-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lechner M, Sutton L, Murkin C, Masterson

L, O'Flynn P, Wareing MJ, Tatla T and Saeed S: Squamous cell cancer

of the temporal bone: A review of the literature. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 278:2225–2228. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

McCracken M, Pai K, Cabrera CI, Johnson

BR, Tamaki A, Gidley PW and Manzoor NF: Temporal bone resection for

squamous cell carcinoma of the lateral skull base: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 168:154–164.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gidley PW, Thompson CR, Roberts DB,

DeMonte F and Hanna EY: The oncology of otology. Laryngoscope.

122:393–400. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Allanson BM, Low TH, Clark JR and Gupta R:

Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal and temporal

bone: An update. Head Neck Pathol. 12:407–418. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sato K, Komune N, Hongo T, Koike K, Niida

A, Uchi R, Noda T, Kogo R, Matsumoto N, Yamamoto H, et al: Genetic

landscape of external auditory canal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Sci. 111:3010–3019. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yin M, Ishikawa K, Honda K, Arakawa T,

Harabuchi Y, Nagabashi T, Fukuda S, Taira A, Himi T, Nakamura N, et

al: Analysis of 95 cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the external

and middle ear. Auris Nasus Larynx. 33:251–257. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Acharya PP, Sarma D and McKinnon B: Trends

of temporal bone cancer: SEER database. Am J Otolaryngol.

41:1022972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hongo T, Kuga R, Miyazaki M, Komune N,

Nakano T, Yamamoto H, Koike K, Sato K, Kogo R, Nabeshima K, et al:

Programmed death-ligand 1 expression and tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes in temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope.

131:2674–2683. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Komune N, Noda T, Kogo R, Miyazaki M,

Tsuchihashi NA, Hongo T, Koike K, Sato K, Uchi R, Wakasaki T, et

al: Primary advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone:

A single-center clinical study. Laryngoscope. 131:E583–E589. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

House JW: Facial nerve grading systems.

Laryngoscope. 93:1056–1069. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Moody SA, Hirsch BE and Myers EN: Squamous

cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: An evaluation of a

staging system. Am J Otol. 21:582–588. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nabuurs CH, Kievit W, Labbe N, Leemans CR,

Smit CFGM, van den Brekel MWM, Pauw RJ, van der Laan BFAM, Jansen

JC, Lacko M, et al: Evaluation of the modified Pittsburgh

classification for predicting the disease-free survival outcome of

squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal. Head Neck.

42:3609–3622. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zanoletti E, Franz L, Cazzador D,

Franchella S, Calvanese L, Nicolai P, Mazzoni A and Marioni G:

Temporal bone carcinoma: Novel prognostic score based on clinical

and histological features. Head Neck. 42:3693–3701. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Franz L, Zanoletti E, Franchella S,

Cazzador D, Favaretto N, Calvanese L, Mazzoni A, Nicolai P and

Marioni G: Temporal bone carcinoma: Testing the prognostic value of

a novel clinical and histological scoring system. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 278:4179–4186. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shinomiya H, Uehara N, Teshima M, Kakigi

A, Otsuki N and Nibu KI: Clinical management for T1 and T2 external

auditory canal cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx. 46:785–789. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Piras G, Grinblat G, Albertini R,

Sykopetrites V, Zhong SX, Lauda L and Sanna M: Management of

squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: Long-term results and

factors influencing outcomes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

278:3193–3202. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang T, Li W, Dai C, Chi F, Wang S and

Wang Z: Evidence-based surgical management of T1 or T2 temporal

bone malignancies. Laryngoscope. 123:244–248. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Homer JJ, Lesser T, Moffat D, Slevin N,

Price R and Blackburn T: Management of lateral skull base cancer:

United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol

Otol. 130:S119–S124. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Morita S, Homma A, Nakamaru Y, Sakashita

T, Hatakeyama H, Kano S, Fukuda A and Fukuda S: The outcomes of

surgery and chemoradiotherapy for temporal bone cancer. Otol

Neurotol. 37:1174–1182. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Seligman KL, Sun DQ, Eyck PP, Schularick

NM and Hansen MR: Temporal bone carcinoma: Treatment patterns and

survival. Laryngoscope. 130:E11–E20. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lovin BD and Gidley PW: Squamous cell

carcinoma of the temporal bone: A current review. Laryngoscope

Investig Otolaryngol. 4:684–692. 2019. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Borsetto D, Vijendren A, Franchin G,

Donnelly N, Axon P, Smith M, Masterson L, Bance M, Saratziotis A,

Polesel J, et al: Prevalence of occult nodal metastases in squamous

cell carcinoma of the temporal bone: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 279:5573–5581. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lee JM, Joo JW, Kim SH, Choi JY and Moon

IS: Evidence based tailored parotidectomy in treating external

auditory canal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 8:121122018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xie B, Wang M, Zhang S and Liu Y:

Parotidectomy in the management of squamous cell carcinoma of the

external auditory canal. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 278:1355–1364.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhen S, Fu T, Qi J and Wen J: Adenoid

cystic carcinoma of external auditory canal: 8 cases report. Lin

Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 29:343–345. 2015.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang M, Song Y, Liu S and Sun W: Effect of

surgery and radiotherapy on overall survival in patients with

chondrosarcoma: A SEER-based study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong).

30:102255362210863192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lu VM, Wang S, Daniels DJ, Spinner RJ,

Levi AD and Niazi TN: The clinical course and role of surgery in

pediatric malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: A database

study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 29:92–99. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Frankart AJ, Breneman JC and Pater LE:

Radiation therapy in the treatment of head and neck

rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 13:35672021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Agosti E, Zeppieri M, Antonietti S, Ius T,

Fontanella MM and Panciani PP: Advancing the management of skull

base chondrosarcomas: A systematic review of targeted therapies. J

Pers Med. 14:2612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ebisumoto K, Okami K, Hamada M, Maki D,

Sakai A, Saito K, Shimizu F, Kaneda S and Iida M: Cetuximab with

radiotherapy as an alternative treatment for advanced squamous cell

carcinoma of the temporal bone. Auris Nasus Larynx. 45:637–639.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yan J and Sui JD: Long-term survival after

immunotherapy for uncontrolled locally advanced temporal bone

squamous cell carcinoma followed by chemoradiotherapy: A case

report. Precis Radiat Oncol. 28:99–105. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Testa JR, Fukuda Y and Kowalski LP:

Prognostic factors in carcinoma of the external auditory canal.

Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 123:720–724. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang B, Tu G, Xu G, Tang P and Hu Y:

Squamous cell carcinoma of temporal bone: reported on 33 patients.

Head Neck. 21:461–466. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nyrop M and Grontved A: Cancer of the

external auditory canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

128:834–837. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Komune N, Kuga R, Hongo T, Kuga D, Sato K

and Nakagawa T: Impact of positive-margin resection of external

auditory canal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel).

15:42892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gidley PW and DeMonte F: Temporal bone

malignancies. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 24:97–110. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bacciu A, Clemente IA, Piccirillo E,

Ferrari S and Sanna M: Guidelines for treating temporal bone

carcinoma based on long-term outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 34:898–907.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Morris LG, Mehra S, Shah JP, Bilsky MH,

Selesnick SH and Kraus DH: Predictors of survival and recurrence

after temporal bone resection for cancer. Head Neck. 34:1231–1239.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Omura G, Ando M, Saito Y, Fukuoka O,

Akashi K, Yoshida M, Kakigi A, Asakage T and Yamasoba T: Survival

impact of local extension sites in surgically treated patients with

temporal bone squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol.

22:431–437. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dean NR, White HN, Carter DS, Desmond RA,

Carroll WR, McGrew BM and Rosenthal EL: Outcomes following temporal

bone resection. Laryngoscope. 120:1516–1522. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Manolidis S, Pappas D Jr, Von Doersten P,

Jackson CG and Glasscock ME III: Temporal bone and lateral skull

base malignancy: Experience and results with 81 patients. Am J

Otol. 19:S1–S15. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|