OC is associated with the highest mortality rates

among female reproductive system malignancies, with a 5-year

survival rate of ~47% (1,2). Annually, there are >239,000 new

cases of OC worldwide and 152,000 deaths. Only 15% of cases of OC

are diagnosed clinically early, and the majority of patients are

already diagnosed with metastatic tumors upon receiving an OC

diagnosis, thereby exacerbating their unfavorable prognosis and

elevated mortality rate. Most cases of OC are treated with surgery

and cytoreduction (3); however, in

this context, drug resistance arising from repeated therapy may no

longer explain the low 5-year survival rates. In particular, OC

enhances chemotherapy resistance through its antioxidant capacity

by upregulating multiple key antioxidant systems, such as NAD(P)H

oxidoreductase 1 (4), the

SLC7A11/xCT antiporter (5) and the

NRF2 pathway (6), which can prevent

the formation of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by

chemotherapy, particularly platinum-based therapies such as

cisplatin. Therefore, investigating new and potent biomarkers of OC

tumors, as well as elucidating the molecular mechanisms driving

cancer metastasis, is imperative to develop more targeted

therapeutic strategies for OC (7).

NPs are known to both contribute to and inhibit the

growth of cancer cells by controlling the cell cycle (8), stem cell development (9), exercise metabolism (10), the immune response (11) and DNA damage and repair (12,13).

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) of these proteins,

including phosphorylation, ubiquitin conjugation, SUMOylation and

poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, are known to control these various

biological processes (14,15). Nuclear proteins (NPs) can be altered

in different ways, including genomic mutations,

transcriptional/splicing variations and PTMs, depending on the

expression levels at their target sites. These alterations, acting

alone or in concert, allow NPs to exert distinct molecular and

biological impacts. For example, when mutated, the nuclear protein

p53, normally a tumor suppressor, acquires oncogenic

gain-of-function activity at high concentrations, driving

metastasis and chemoresistance (16). Similarly, as a core PEST-NP that

governs ovarian cancer (OC) progression, especially critical in

high-grade serous OC (HGSOC), where ~96% of cases harbor p53

mutations, p53 activation in response to DNA damage induces the

expression of ring finger protein 144A (RNF144A) (11). RNF144A exhibits broad cellular

distribution, primarily localizing to the plasma membrane and

perinuclear region; notably, as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, it is

directly involved in regulating the PTM of p53, a key process

controlling the stability, degradation and functional output of

this PEST-NP. However, the functional importance of the

interactions of RNF144A with DNA-dependent protein kinases, which

itself acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase to mediate p53 degradation

during p53 autoubiquitination, remains currently unclear.

Therefore, as ubiquitination status of p53 directly dictates its

ability to inhibit OC cell proliferation, induce apoptosis or drive

chemoresistance, clarifying how DNA-dependent protein kinase

(DNA-PK) modulates RNF144A-mediated p53 degradation could uncover

novel regulatory mechanisms of PEST-NP function in OC, and

potentially identify new therapeutic targets to restore the

tumor-suppressive role of p53 in OC. Several NPs, including KU70,

PARP1, DNA ligase III and XRCC1, undergo degradation through

PAR-dependent alterations (17).

PTMs serve key roles in regulating various physiological processes

involving these proteins. For instance, ubiquitination controls the

stability of PEST-containing NPs (PCNPs) such as p53, while

phosphorylation at Ser15/Ser20 disrupts p53-MDM2 interactions to

stabilize p53 during DNA damage (18). Such PTM-dependent regulation is

often disrupted by p53 mutations in OC, driving chemoresistance

(19).

The present review summarized the current research

on NP biology and associated potential molecular targets involved

in various cellular processes that contribute to the development of

OC. Further research may elucidate the precise associations of NPs

and mechanisms of cancer progression that hold significant

potential for the wider utilization of NPs as diagnostic and

therapeutic targets in various types of OC.

The PEST sequence is a peptide sequence rich in P,

E, S and T. PEST sequences are commonly found in proteins with a

short intracellular half-life, acting as a recognition motif for

degradation-related enzymes and thus influencing protein stability

and turnover in cellular processes. Further research has

demonstrated that PEST sequence-enriched NPs are numerous, widely

dispersed and involved in various physiological and cellular

processes. Often referred to as ‘cell guardians’, PEST-NPs regulate

pathways such as the ubiquitin-proteasome system, nuclear pore

glycosylation and the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (20). PEST-NPs participate in cell cycle

control, cyclic nucleotide signaling, nucleocytoplasmic transport

and the nutritional regulation of cellular metabolism and

physiology (21). In cancer

biology, several PEST-NPs regulate the tumor cell cycle, either

directly by binding to DNA or indirectly by ubiquitinating cyclins

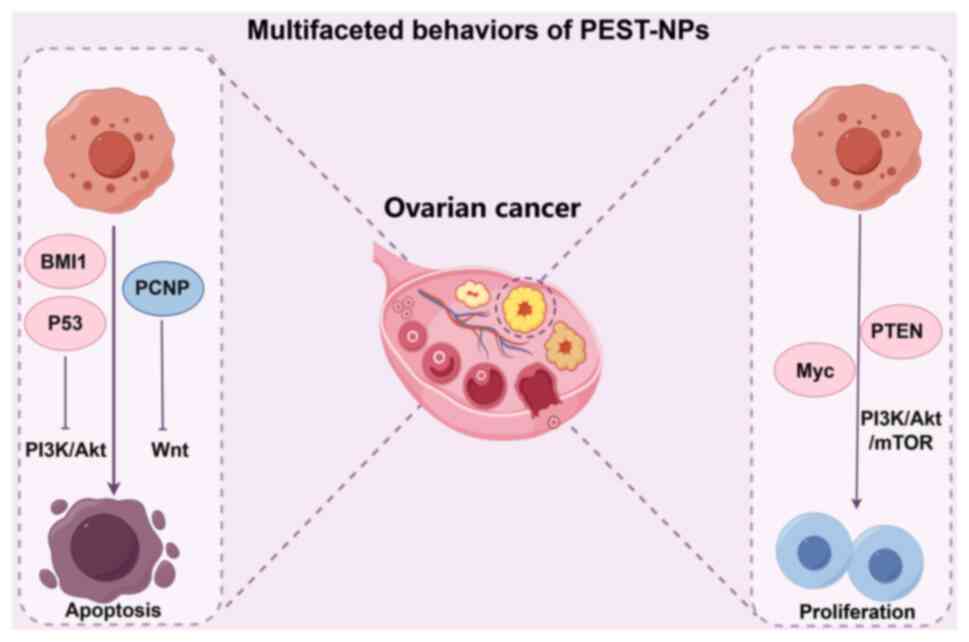

D1 and E1, leading to G1 arrest (Fig. 1). PEST-NPs can also modulate the

cancer-immune system through apoptosis and autophagy induction and

regulate cancer metabolism via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

(PI3K), mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. The biological activity

of PEST-NPs is influenced by their intracellular distribution and

abundance at target sites, with PTMs such as phosphorylation and

ubiquitination serving key roles in regulating their localization,

activation and expression levels. For instance, the ubiquitination

of the PEST-domain of p53 by MDM2 controls its nucleocytoplasmic

shuttling and stability, dictating apoptotic vs. pro-survival

outcomes in OC (18).

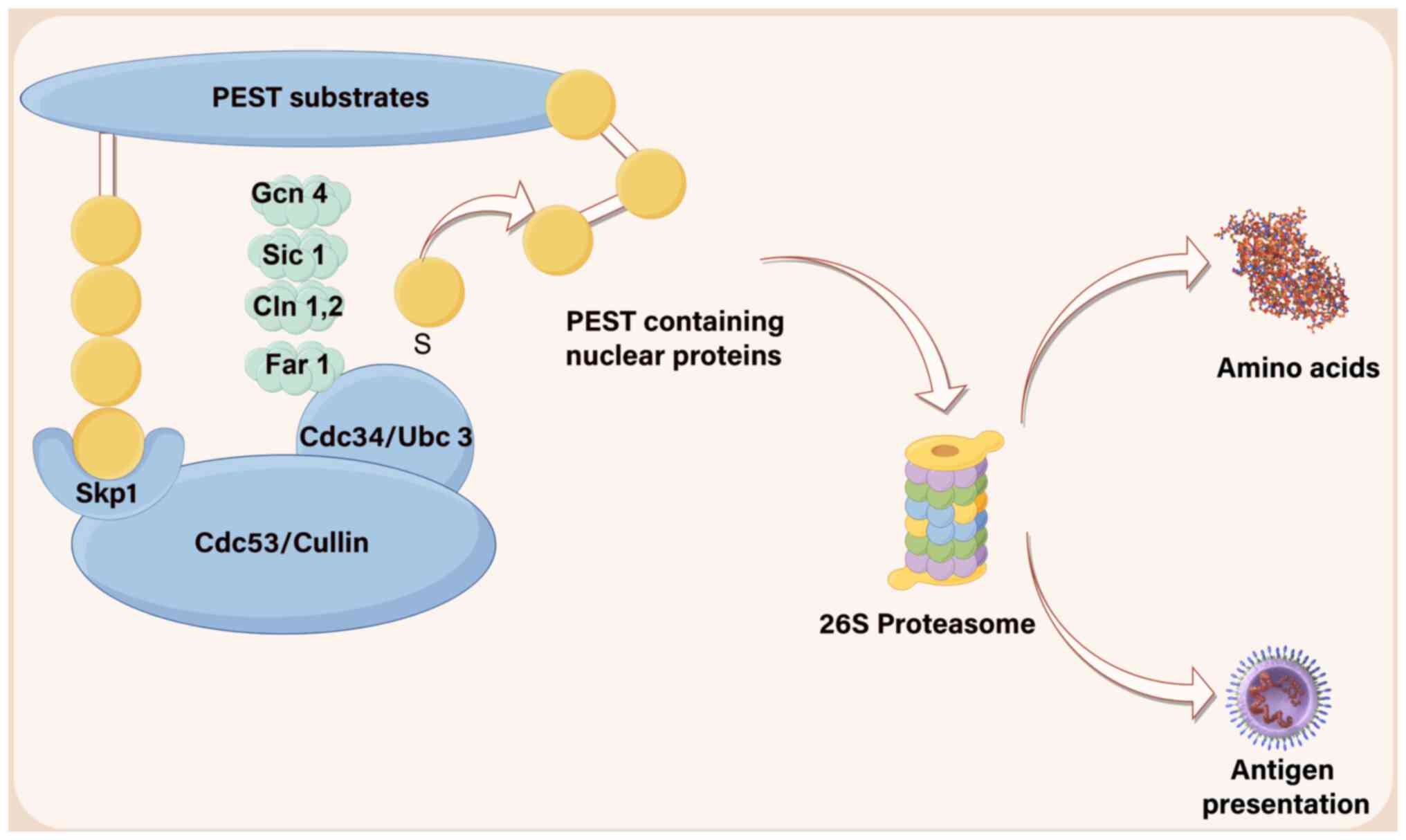

As a structural recognition element, the PEST motif

primarily governs substrate degradation primarily through

mechanisms such as proteasomal turnover (such as endocytosis of the

yeast a-factor receptor STE3) (22)

or lysosomal degradation (such as human calcium receptors on the

cell surface) (23). For example,

Ck2-mediated phosphorylation leads to the degradation of IkB and

IKK, whereas cAMP-dependent protein kinase breaks down proteins

involved in cyclic nucleotide metabolism. Phosphorylation of the

carboxyl terminus of the PEST domain promotes the degradation of

substrate proteins such as PCNP and MeCP2, such as PCNP and MeCP2,

which are also heavily ubiquitinated (24,25).

Additionally, IKK undergoes degradation via calpain-mediated

modification of Bcl6 and P300-mediated acetylation of Bcl6

(26,27). The stability and MAPK-induced

activation of VEGF2 are mediated by the phosphorylation of serine

1,188 within its PEST sequence (28). Under normal conditions, PEST-NPs

maintain short half-lives due to PEST-regulated proteasomal

degradation, ubiquitin conjugation and ligase-mediated control of

their cellular levels (Fig. 2).

Two major genetic alterations drive carcinogenesis:

The activation of oncogenes and the loss of tumor suppressor

activity. In this context, protein modifications mediate

transcription, intracellular localization and degradation (29,30).

Overproduction or overactivation of transcription factors such as

Myc and NF-κB leads to uncontrolled growth and metastasis in

various types of cancer (31). For

example, PTEN activity, localization and stability are regulated by

SUMOylation (mono- or poly-ubiquitination of SUMO1 and SUMO2/3)

(32,33). Similarly, in NF-κB signaling,

phosphorylation of the PEST motif and subsequent proteolytic

degradation of the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase initiates NF-κB

nuclear translocation, transcriptional activation and DNA damage.

Overall, PTMs are responsible for regulating activation and

inhibition, maintaining protein stability and degradation, and

determining the intracellular localization of PEST-NPs (34,35).

p53, a PEST-NP with anticancer properties, induces

apoptosis by increasing mitochondrial permeability. Under stress,

nuclear p53 interacts with the cytoplasmic Bcl-xl-p53 complex,

releasing the p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) to

initiate mitochondria-dependent apoptosis (36,37).

Following apoptosis, p53 is rapidly degraded in both the cytoplasm

and nucleus: Nuclear p53 is conjugated with ubiquitin, translocates

across the nuclear membrane and is degraded by the ubiquitin ligase

mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) in the cytoplasm (38,39).

This PTM-mediated activation (via stress-induced conformational

changes) and inhibition (via MDM2-dependent ubiquitination)

exemplify how PTMs control p53 function.

PEST motif modifications are critical for PEST-NP

stability, activation and deactivation. The PEST-containing

transcription factor BMI1 proto-oncogene, polycomb ring finger

(Bmi1, a PEST-NP) interacts with O-GlcNAcylation transferase at

serine 255, increasing its stability and oncogenic activity by

suppressing p53, PTEN and CDKN1A/CDKN2A (40). Similarly, tankyrase-mediated

ADP-ribosylation of PTEN (a PEST-NP with two PEST sequences)

promotes its ubiquitination and degradation by the E3 ligase

RNF146, reducing its tumor suppressor activity (33). These examples illustrate how PTMs

directly modulate PEST-NP turnover to influence carcinogenesis.

PTMs of the PEST motif also regulate the

localization, a key determinant of their pharmacological and

carcinogenic effects, through modifications that impact protein

activation, stability and subcellular distribution (35). The nuclear localization sequences

(NLSs) and nuclear export sequences (NES) found on cargo proteins

are recognized by importins and export proteins, which mediate

directional transport across the nuclear envelope (41,42).

The imbalanced shuttling of cargo proteins between the nucleus and

cytoplasm, often driven by mutations in NLS/NES regions or

dysregulation of shuttle determinants like PSPC1, is closely

related to tumorigenesis (43,44).

Unlike the cytoplasmic form of p53, which induces apoptosis through

interactions with mitochondrial Bcl-2 family proteins (such as

Bax), the nucleolar form of p53 is activated in response to

nucleolar stress and participates in the DNA damage response

(45). The antiapoptotic protein

Bcl-xL, by contrast, binds to cytoplasmic p53. Unless PUMA releases

the protein trapped in p53, the mitochondrial membrane cannot be

opened to carry out anticancer actions. Numerous transporter

inhibitors are being studied for their potential anticancer

properties, such as withacnistin which decreases the levels of

antiapoptotic proteins, and prevents signal transducer and

activator of STAT3 from being localized in the nucleus (46). As a result, the PEST motif

contributes to the diverse properties of NPs, giving PEST-NPs a

wide range of molecular and physiological functions.

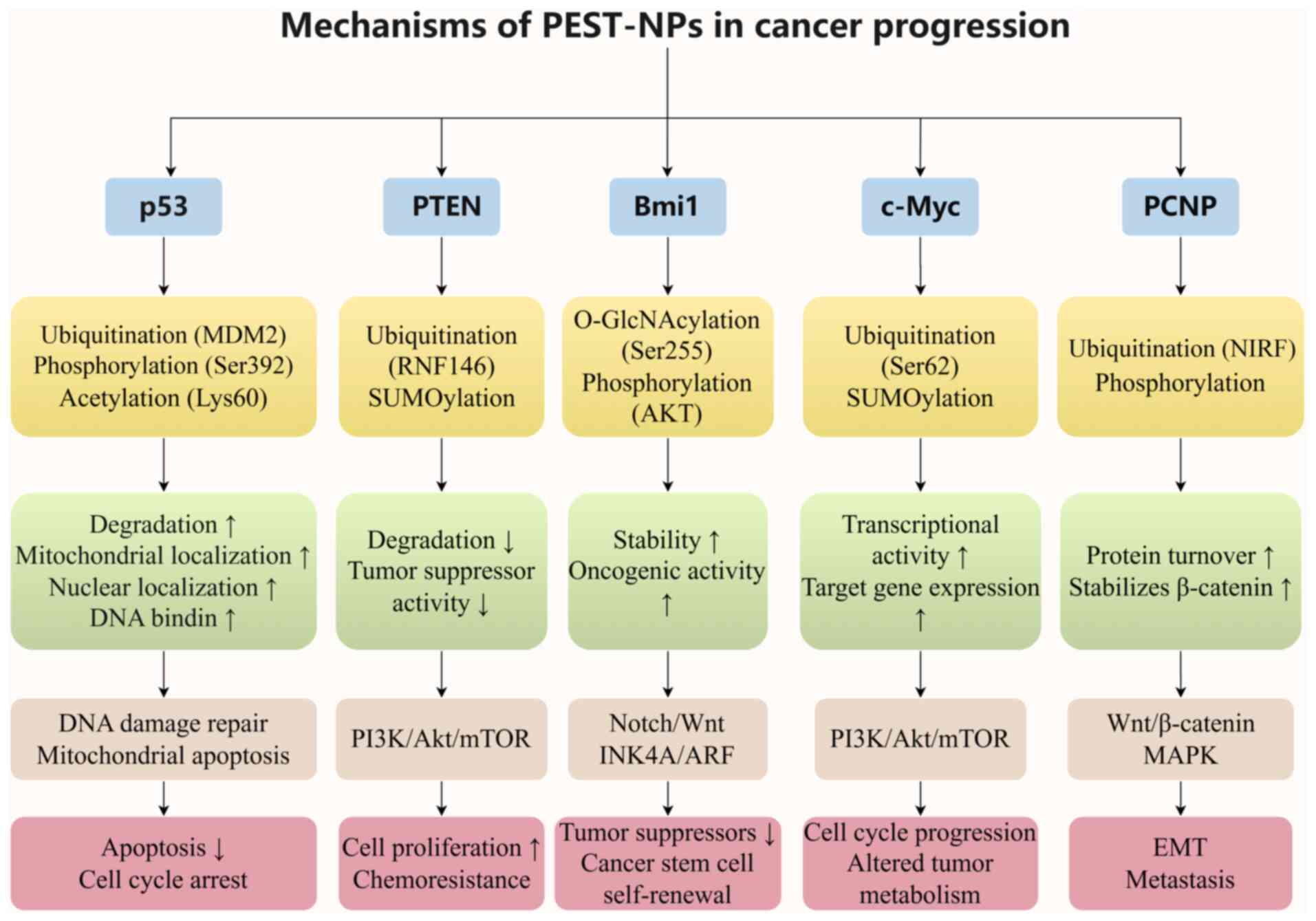

The present review outlined how PTMs of PEST NPs

affect their activation/inhibition, stability/degradation and

intracellular localization to induce a tumor-promoting or

tumor-suppressive response. The emphasis on molecular-level

protein-protein interactions enables supports the understanding of

the complex behavior of PEST NPs in cancer biology. Although

numerous NPs exist, the most significant model PEST NPs, including

p53, PTEN, Bmi1, c-Myc and PCNP, were examined as model

PEST-containing proteins. The structural composition of these

proteins determines their genesis, mode of action and ultimate

fate. The computer-aided application ‘PEST Discover’ defines

authentic PEST domains by calculating a ‘PEST score’, a metric

combining residue composition (P, E, S and T) and hydrophobicity to

predict proteolytic signals. This score [PEST-FIND=0.5 × (mole

percent of P/E/D/S/T)-0.5 × (hydrophobicity index)] discriminates

degradation-prone regions (score >0.5) and enables structural

comparisons of PEST-containing proteins. The computational

framework aligns with tools like PESTfind (http://emb1.bcc.univie.ac.at/embnet/tools/bio/PESTfind),

which implements this algorithm (Table

I).

A number of malignancies (50%) have a mutation in

the p53 gene, which can result in either loss of function or

carcinogenicity (47).

Loss-of-function mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor have the

potential to cause chromosomal instability, loss of cell cycle

arrest, loss of apoptosis, loss of senescent growth arrest and

ineffective DNA base excision repair (48). These modifications enable the

avoidance of key cell cycle pathways, promoting cancer growth. By

contrast, p53 oncogenic mutations with gain-of-function effects can

accelerate tumor metastasis, alter the transcriptional activity of

target genes, inhibit apoptosis and increase chemotherapeutic

resistance (49). A large

proportion (96%) of patients with HGSOC have p53 mutations that

span both gain-of-function (oncogenic) and loss-of-function (loss

of p53 activity) events (50–52).

Human p53 functions as an active homotetramer, with

each subunit consisting of 393 amino acids. This protein has a

complex domain structure, including an N-terminal region with a

ubiquitin ligase (MDM2) binding site, an amino-terminal

transactivation domain (TAD; comprising TAD1 and TAD2), a

DNA-binding domain (DBD), a tetramerization domain, a linker

region, a proline-rich domain and a carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD)

(41,53). The N-terminal segment features five

repeats of proline-XX-proline sequences, where ‘X’ represents an

amino acid that varies across species, as do several

phosphorylation sites between residues 62 and 94 (53). The MDM2 binding site overlaps with

the TAD, specifically TAD1 (residues 1–39) and TAD2 (residues

40–61). The N-terminal region, particularly TAD2, contains PEST

motifs, which can interact with the DBD, potentially inhibiting DNA

binding. The DBD regulates the nuclear and cytoplasmic functions of

p53, as it is critical for mediating DNA-dependent nuclear

activities and indirectly influencing cytoplasmic processes through

its structural role in maintaining p53 functional integrity

(54). Missense mutations in the

DBD (R175, Y220, G245, R248, R249, R273 or R282) account for 62% of

all p53 mutations that are associated with cancer (82% of HGSOC

cases). These mutations eliminate DNA-binding capabilities either

directly or indirectly (53–55).

According to a previous study, the amino acid arginine at position

273 (R273) in the DBD is the most frequently altered, with

histidine (R273H) accounting for 46.6% of the R273 mutations and

cysteine (R273C) accounting for 39.1% (19). It has been proposed that these DBD

mutations lead to a structural shift that affects p53 stability,

making the protein structure stiffer compared with wild-type (WT)

p53 (56). These important DBD

mutations interfere with the ability of p53 ability to regulate

apoptosis, causing malignant cells to proliferate unrestrained. The

CTD carries three nuclear localization signals that allow p53 to

localize to the nucleus (57).

As a transcription factor, p53 interacts with

thousands of genes and is essential for preserving cellular

homeostasis (58,59). In normal cells, p53 is maintained at

a tightly regulated, physiological level; this strict control is

necessary because p53 acts as a potent inducer of apoptosis, and

unregulated p53 activity would trigger excessive cell death that

disrupts normal tissue homeostasis (60). Under normal circumstances, the

cellular expression level of the p53 protein, similar to that of

other PEST-NPs, is very low because of its short half-life of ~620

min. PEST motifs, which are attached to the COOH terminus of

residual proteins, act as signals for PTMs of p53 (phosphorylation

and ubiquitination) and regulate not only proteasomal degradation

(57). The PEST motifs attached to

the CTD of p53 function as signals for its PTMs, including

phosphorylation and ubiquitination; these motifs not only regulate

the proteasomal degradation of p53 but also modulate its

intracellular localization (53).

The protein p53 mediates distinct responses depending on its

subcellular localization: Cytoplasmic accumulation of p53 promotes

mitochondrial outer membrane permeability and initiates

mitochondria-dependent apoptosis (61), whereas nuclear localization enables

p53 to trigger the DNA damage response and transcribe target genes

involved in cell cycle regulation (54,62).

Upon cellular stress, p53 is activated via phosphorylation and

other PTMs; this activation enhances its stability and DNA-binding

capacity, thereby increasing the expression of target genes

associated with cell cycle arrest and DNA repair (62). In the cytoplasm and mitochondria,

monomeric or homodimeric p53 interacts with Bcl-xL (antiapoptotic)

and Bak (apoptotic regulator) to control autophagy and apoptosis

(60). In the cytoplasm and

mitochondria, monomeric or homodimeric p53 interacts with Bcl-xL

(antiapoptotic) and Bak (apoptotic regulator) to control autophagy

and apoptosis (61–63).

Inactivation of p53 activity can occur directly

through mutation or indirectly through the aggregation or

disruption of regulatory proteins (64). The E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2

typically maintains low levels of p53 through ubiquitin-mediated

proteasomal degradation, a process facilitated by the PEST motifs

located in the CTD of p53 (65).

Overall, two basic pathways for p53 inactivation have been

proposed: p53 mutation and WT p53 degradation through negative

regulatory proteins, such as MDM2 or MDM4 (41). The ubiquitin ligases MDM2 and MDM4

facilitate the targeting of p53 for proteasomal degradation

(65). In malignancies such as

epithelial (EOC) and HGSOC, the most aggressive and common subtypes

of OC (52), the upregulation of

MDM2 and MDM4 (inhibitors of p53) can lead to the downregulation of

p53, in addition to p53 mutations (57,65).

The upregulation of MDM2 and MDM4 inhibitors can lead to the

downregulation of p53, in addition to p53 mutations. Thus, a

primary focus of treatment strategies for malignancies with

wild-type p53 has been the development of antagonists for MDM2 and

MDM4 (65).

The overexpression of the PI3K pathway occurs in

40–70% of OCs and is thus another significant mechanism for p53

regulation (66). The suppression

of PI3K has been shown to lead to the regression of OC both in

vivo and in vitro (67).

Additionally, PTEN, a negative regulator of PI3K, is often found to

be absent in OC. Furthermore, owing to the exposure of a structural

‘sticky’ region, typical p53 mutations can lead to protein

aggregation (57). These distinct

yet related pathways highlight the complexity of p53 regulation,

several mechanisms of which are currently poorly understood. Cancer

cells have developed the capacity to modify and inactivate p53,

dubbed ‘the guardian of the genome’ for its role in maintaining

genomic integrity (60), to evade

tumor suppression and promote proliferation; p53 mutations are

nearly ubiquitous in HGSOC, with reported frequencies exceeding 90%

in clinical cohorts (53). Notably,

however, there are currently no Food and Drug administration

approved p53-based therapeutics for HGSOC. While WT p53 and

p53-based therapeutics, which may be administered via drug delivery

systems such as nanoparticles, viruses, polymers and liposomes,

have been a focus of extensive study (68–73),

these innovative therapeutic approaches have yet to be fully

developed and optimized.

In response to active accumulation in specific

subcellular compartments, the p53 protein mediates distinct

cytoplasmic and nuclear responses. Cytoplasmic accumulation of p53

induces mitochondrial outer membrane permeability and apoptosis

through direct interactions with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family

proteins (60,61), whereas nuclear localization enables

p53 to initiate the DNA damage response and transcription of target

genes involved in cell cycle regulation and genome maintenance

(53,54). A p53 mutation, however, can suddenly

disrupt the normal processes of tightly regulated nucleocytoplasmic

shuttling. PTMs include phosphorylation at threonine 155, which

mediates nuclear export (74);

phosphorylation at serine 392, which mediates mitochondrial

localization (75); and kinase

inhibitors, which suppress nuclear export and are responsible for

p53 nuclear export (57). Another

alteration of p53 that results in activation, DNA binding and

nuclear localization is acetylation at lysine residues (76).

PTEN is a tumor suppressor nuclear protein initially

discovered in a mutant form in glioblastoma, prostate and breast

cancer cell lines and xenografts (77). PEST-NP PTEN (or MMACI/TEP1) has 9

exons, 1,212 nucleotides and 403 amino acids and has a molecular

mass of 47 kDa (78–80). The N-terminal phosphatase and

C-terminal domains, along with a short N-terminal tail, constitute

the major portion of the PDZ-binding C2 domain, which is

responsible for binding the phospholipid membrane and serves a key

role in the proper positioning of PTEN at the plasma membrane in

the C-terminal region. The protein also contains two PEST

sequences, which regulate its tumor-suppressive function (81,82).

The tail of the C-terminus comprises ~50 amino acids

and is responsible for active phosphorylation. The primary cause of

the anticancer activity of PTEN is its lipid phosphatase activity.

Loss of function is characterized by the inhibition of the

enzymatic activity of PTEN. Invasion and gene expression are

correlated with phosphatase activity. In addition to being

responsible for the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of

proteins, the PEST region of PTEN also contributes to increased

protein stability, and its loss significantly decreases the

expression of the PTEN protein. The nuclear import,

tumor-suppressing properties and degradation of PTEN are controlled

by ubiquitination, specifically ubiquitination of its PEST motifs

(81–83). PTEN contains two PEST sequences in

its carboxyl-terminal region; these motifs not only contribute to

maintaining PTEN protein stability (81,82)

but also serve as key targets for ubiquitin ligases. This PEST

motif-specific ubiquitination directly modulates PTEN's nuclear

translocation, abrogates its tumor-suppressive activity and

promotes its proteasomal degradation (83).

KRAS, BRAF, PTEN and β-catenin mutations are present

in type I tumors, which are considered to be genetically stable

(84–86). KRAS and BRAF mutations, in

particular, are mutually exclusive, affect two-thirds of type I

OCs, and cause early neoplastic transformation by constitutively

activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction

pathway (87). PTEN mutations can

coexist with KRAS mutations in the ovary, which has been found to

cause invasive and broadly metastatic EOC (86,87).

PTEN mutations can also occur independently, leading to aberrant

activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (88). According to several preclinical

models, one of several genetic modifications affecting the

fallopian tube is the deletion of PTEN (89–91).

The conditional homozygous PTEN deletion mediated by

PAX8-cre recombinase was sufficient to cause borderline serous OC

and endometrioid tumors in mouse models (92). Research suggests that HGSOC has a

unique etiology; the current HGSOC formation paradigm suggests that

it originates in the fallopian tube, which is supported by genomic,

transcriptomic and proteomic investigations demonstrating shared

molecular signatures between fallopian tube precursor lesions and

invasive HGSOC (93–95). Mutations in the p53 gene that cause

protein stabilization in the fallopian tube are crucial in this

process. Following the loss of other tumor suppressors or the

amplification of oncogenes (such as PTEN and KRAS), a serous tubal

intraepithelial carcinoma develops, which later metastasizes to the

ovary and peritoneum (94).

Research has shown that four out of twelve (33%)

serous intratubal carcinoma samples had PTEN deletion (95). These findings, in line with those of

endometrioid carcinomas of the uterus, where progressive loss of

PTEN and PAX2 expression characterizes early precancerous lesions

and carcinogenesis (96,97), led to the suggestion that variations

in PTEN and PAX2 expression may be involved in the early stages of

serous carcinogenesis. As observed in the endometrial model, it is

unknown whether these modifications occur before malignancy or

concurrently with its onset. Additionally, it has been demonstrated

that the loss of PTEN enables the formation of multicellular tumor

spheroids in the fallopian tube epithelium. These spheroids

colonize the ovary by adhering to the extracellular matrix that is

exposed after ovulation and may have seeded the ovary in patients

with HGSOC (96). PTEN loss has

been associated with increased cell transformation and

proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, as well as

with the stimulation of MUC1 expression, which is known to serve

key roles in cancer cell migration and metastasis (97).

Bmi1, a polycomb group protein (also known as PRC1),

is essential for the epigenetic regulation of several cellular

processes, including proliferation, differentiation, stem cell

self-renewal and chemoresistance to various cancer drugs. In EOC,

Bmi1 contributes to resistance against platinum-based

chemotherapeutic agents (such as cisplatin), Bmi1 encodes 326 amino

acids with a molecular weight of 44–46 kDa. The protein has two

domains: Bmi1, which associates with and partially encloses Ring1b,

and the tail of Ring1b, which wraps around Bmi1. The oncogene Bmi1

binds to the substrate protein and ubiquitinates the lysine of the

substrate protein, via the E3 ligase Ring1b, (97,98).

For example, Bmi1 reduces the stability of p53 by ubiquitinating it

via Ring Finger Protein 2/Ring1b (99,100).

Two NLSs, NLS1 and NLS2, are located in the protein

Bmi1 and are responsible for the nuclear localization of Bmi1. NLS2

is a key signal for the nuclear localization of Bmi1 (98). Bmi1 is split into three parts on the

basis of its function: An N-terminal conserved ring domain, a

central helix-turn-helix (HTH) domain and a carboxyl-terminal area

with a PEST-like domain. The ring domain of Bmi1 focuses on DNA

strand breaks in response to DNA damage, which helps cells escape

senescence due to the synergistic action between the N-terminal

ring domain and central HTH domain Bmi1 (101,102). As a result, it lengthens the time

that cells can replicate, leading to the accumulation of more cells

in the G2/M phase and thereby increasing cell

proliferation (103).

Bmi1 also increases the length of time that a tumor

cell can survive because by activating N-Myc, as it blocks the

transcription of tumor suppressor genes such as p16, p19, p53 and

PTEN; thus, Bmi1 has an oncogenic function (104,105). Bmi1 overexpression has been

documented in lymphomas (106),

prostate cancer (107), non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (108),

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (109)

and breast cancer. Specifically, in prostate cancer, Bmi1

upregulation correlates with downregulated p16(INK4A) and p14(ARF).

In NSCLC, high Bmi1 expression is associated with reduced p16 and

p14ARF levels. In colon cancer, Bmi1 overexpression coincides with

decreased p16INK4a/p14ARF expression. Through the suppression of

the p21CIP1 gene and the INK4A/ARF locus, Bmi1 is essential for

tumor cell growth and survival in brain cells (110).

The progression of neuroblastoma caused by Bmi1 is

facilitated by the upregulation of cyclin E (111). In prostate cancer cells and

mammary epithelial cells, Bmi1 also increases telomerase activity

(112,113). Bmi1 PTMs at various serine

residues control its INK4A/ARF-dependent and INK4A/ARF-independent

functions (114). Through an

INK4A/ARF-independent mechanism, phosphorylation of Bmi1 by AKT

promotes glioma and hepatic carcinogenesis (115,116) and reduces tumor growth through an

INK4A/ARF-dependent pathway. In accordance with the type of

residual substrate, alterations in the AKT kinase activity of Bmi1

alter its oncogenic characteristics (117).

MAPKAPK3, a MAPK-activated protein kinase, also

phosphorylates Bmi1. The activation or upregulation of MAPKAPK3

leads to the phosphorylation of Bmi1 and other Polycomb proteins,

the recruitment of substrate proteins from chromatin, the

activation of the INKA4/ARF locus induce cell cycle arrest and

senescence to inhibit cancer progression (118,119). Bmi1 is positively regulated by

numerous transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulators,

including N-Myc, C-Myc, specialized protein 1, twist-related

protein 1, forkhead box protein M1, E2F1 and sal-like protein 4. By

contrast, Bmi1 is suppressed at the transcriptional level by

Mel-18, Kruppel-like factor 4 and histone deacetylase inhibitors.

The expression of Bmi1 is also regulated by the Notch and Wnt

pathways (120).

In PTEN-null prostate cancer, elevated Bmi1

expression and its role in neoplasia progression are supported by

studies showing that Bmi1 upregulation correlates with PTEN loss

and promotes tumor aggressiveness, while Bmi1 depletion inhibits

progression. Regarding Bmi1 degradation, it is regulated by

βTrCP-mediated ubiquitination: βTrCP recognizes a specific motif in

Bmi1, promoting its proteasomal turnover via the

ubiquitin-proteasome system (121). βTrCP mediates the ubiquitination

of Bmi1 at tyrosine 18 within its N-terminal RING finger domain;

subsequently, the ubiquitinated Bmi1 is shuttled into proteasomes

for degradation (121,122). The degradation of Bmi1 is

increased in MCF10A cells when TrCP is overexpressed, whereas the

opposite occurs in these MCF10A cells with no TrCP overexpression

(122).

In a previous study, compared with original ovarian

carcinomas, metastatic lymph nodes and recurring tumors

significantly overexpressed Bmi1 (123). Furthermore, Bmi1 is highly

expressed in metastatic and recurrent tumors, and was found to be

predictive of both survival and relapse (124). A number of studies have

investigated the role of Bmi1 as a pathway regulator in both stem

cells and cancer cells, validating its oncogenic activation in

various human malignancies Examples include EOC, where Bmi1

overexpression in metastatic/recurrent tumors correlates with

disease progression and platinum resistance (125), NSCLC, where it links EMT to cancer

stem cell properties (126), as

well as lymphomas, prostate cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and

breast cancer, where elevated Bmi1 expression is associated with

tumor aggressiveness and suppressed tumor suppressor genes

(125,126). Upon suppression of Bmi1, cell

proliferation was significantly reduced and a greater proportion of

EOC cells remained in the G1 phase. Previous research

demonstrated that ER-coupled Bmi1 signature activity influences the

status of p16INK4a and cyclin D1, which correlates with tumor

molecular subtypes and biological behavior in breast cancer

(127).

Furthermore, Bmi1 knockout decreased the ability of

EOC cells to migrate and invade; additional studies demonstrated

that Bmi1 is responsible for triggering the EMT, which leads to

tumor invasion and metastasis (128). Additionally, the overexpression of

Bmi1 in EOC cells increased the expression of cyclin D1, CDK4 and

Bcl-2, thereby increasing cell proliferation and inhibiting cell

death (129). By contrast, a

previous study demonstrated that silencing Bmi1 had the opposite

effect on controlling the cell cycle and apoptosis; it was also

shown that Bmi1 knockout increased the susceptibility of EOC cells

to platinum (123). Similarly,

Wang et al (130) reported

that downregulating Bmi1 increased ROS, triggered the DNA damage

repair pathway and ultimately promoted cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

Together, these data provided insight into chemoresistance, an

ongoing and complex problem in the management of EOC.

The Myc gene, which may be located at chromosome

8q24.21, encodes the super-transcription factor Myc (131). Myc oncoproteins (c-Myc, N-Myc and

L-Myc) regulate the transcription of >15% of expressed genes

(132). The PEST-NP Myc, as the

prototypical nuclear transcription factor, dimerizes with MAX to

drive proliferation and repress differentiation via E-box binding

(133). However, Myc requires

cooperative genetic events, such as loss of p53/p16 checkpoints, to

overcome apoptosis/senescence and induce oncogenesis, as

demonstrated in Myc-Ras transgenic models (134). In ovarian cancer, c-Myc

overexpression is detected in 65.9% of epithelial tumors,

correlating with aggressive phenotypes, consistent with its

PEST-mediated instability and oncogenic plasticity.

The wide, unstructured amino-terminal region in Myc

proteins, which is considered critical for transcriptional

activation, contains conserved boxes known as Myc boxes (MBI and

MBII) (135). The PEST sequences,

meanwhile, are responsible for ubiquitination, with two conserved

Myc boxes (MBIII and MBIV) and one NLS for nuclear accumulation

comprising the middle portion of Myc proteins (136). The basic helix-loop-helix leucine

zipper domain is made up of 100 amino acids, which is necessary for

the DNA-protein interactions that start transcription (133,136). Human cancer cells frequently

overexpress the protein Myc; specific examples include EOC, where

c-Myc overexpression correlates with aggressive tumor phenotypes

(133), as well as lymphomas and

prostate cancer, where Myc overexpression has been linked to

malignant transformation processes (133). Protein translation, cell cycle

progression and differentiation, tumor metabolism and ribosome

biogenesis are important downstream effects of Myc. Numerous

biological processes, including cell differentiation, growth,

survival, immune surveillance and apoptosis, are coordinated with

the regulatory process mediated by the downstream effects of Myc

(137). Myc-associated cell cycle

abnormalities occur after SUMOylation, leading to the enzymatic

activation of Myc (135).

The protein expression of c-Myc has previously been

identified in OC and stromal cells via immunohistochemical

techniques (138). In 76% of cases

of early-stage EOC, Skírnisdóttir et al (139) reported positive staining for c-Myc

via the same method. Tumor grade and positivity status are related;

the c-Myc protein was discovered to be overexpressed in 65.9% of

EOC cases compared with that of normal ovary cancer cases,

according to research by Chen et al (140). However, no discernible distinction

in histological subtypes was observed.

However, retrospective clinical data analysis has

indicated that standard histological indicators are more reliable

predictors of tumor behavior than an evaluation of the c-Myc

expression pattern solely by immunostaining. Ning et al

(147) observed that, following

treatment with platinum-based regimens for ovarian carcinomas,

c-Myc upregulation was associated with improved tumor

differentiation, increased p27 levels and decreased Ki-67

expression. Furthermore, Ning et al (147) reported an association between

shorter overall survival and elevated nuclear c-Myc expression in

early-stage OC.

A PEST-NP member currently under investigation is

PCNP, a PEST-containing nuclear protein first identified in the

early 2000s, which consists of 178 amino acids and exhibits

consistent colocalization with the RING finger protein NIRF in the

perinuclear region (152,153). PCNP mRNA has been detected in

several cell types, including normal fibroblasts (WI-38 and TIG-7),

fibrosarcoma (HT-1080) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells

(151). Further evidence, such as

PCNP overexpression in ovarian cancer driving

Wnt/β-catenin-mediated cell proliferation, migration and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (154), and its interaction with NIRF to

regulate cell cycle-related stability (151). PCNP and NIRF have been

demonstrated to interact with each other both in vitro and

in vivo. The presence of the ubiquitin domain in the

N-terminus and the ring finger catalytic domain in the C-terminus

of NIRF suggests that the PCNP has catalytic activity. The

ubiquitination of PCNP by NIRF is highlighted by the interaction of

PCNP with NIRF in vitro and in vivo, which in turn

controls the stability and regulation of PCNP. The ring finger

proteins MDM2 and p53 share a similar interaction (20,154).

Additionally, NIRF is expressed at a markedly high level in several

malignancies, including EOC, hepatocellular carcinoma and NSCLC

(154,155).

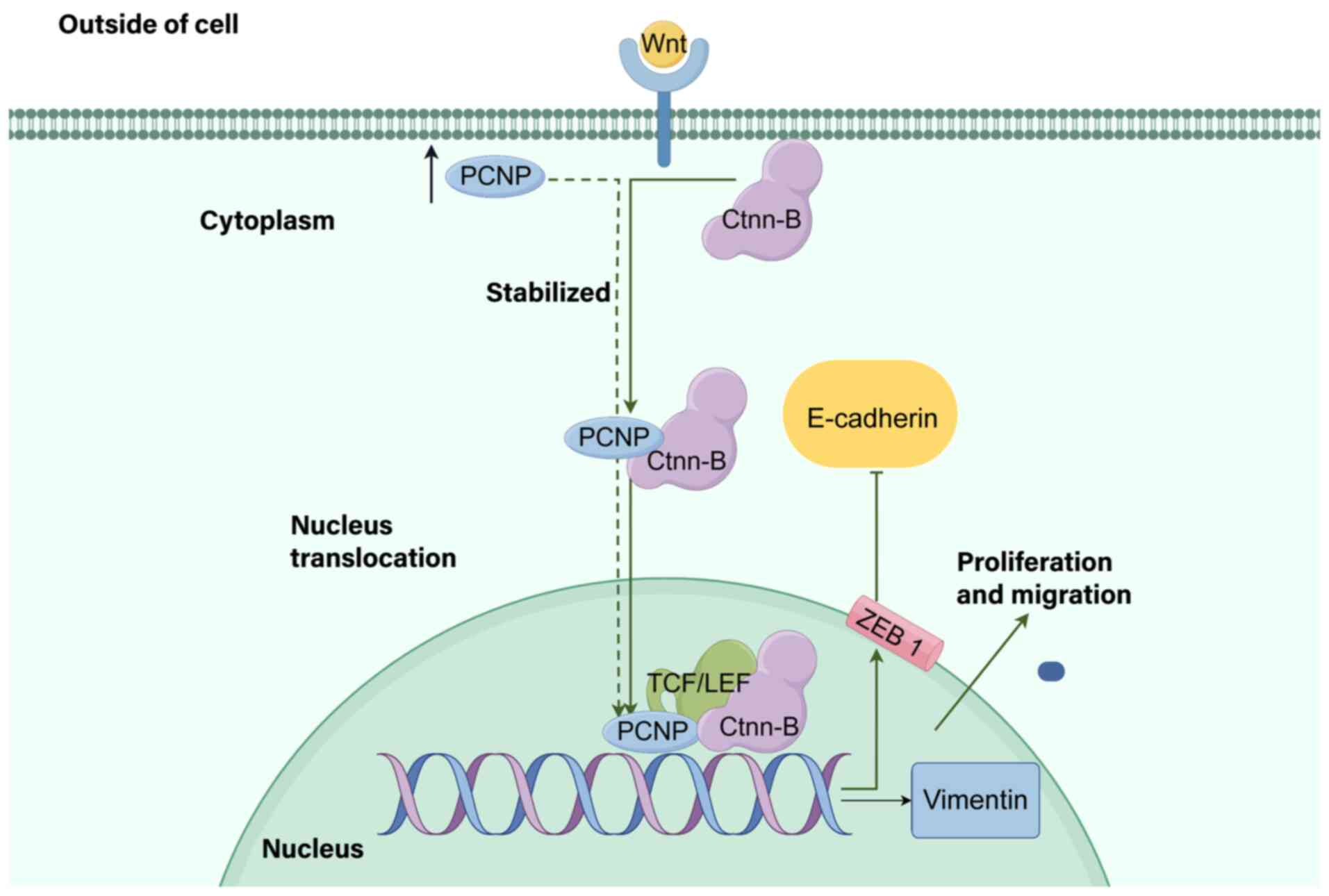

According to previous studies, the MAPK and

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways serve pivotal roles together with

PCNP in the proliferation, migration and invasion of OC,

neuroblastoma and lung adenocarcinoma (154,156). Mechanistically, PCNP binds to

β-catenin, accelerates its nuclear translocation and activates

Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suggesting that PCNP is an upstream

regulator of Wnt-mediated OC progression and a potential

therapeutic target (Fig. 3). The

Wnt signaling pathway, which regulates cell proliferation,

apoptosis and EMT, is critical for tumor initiation and

development, and aberrations in this pathway significantly

contribute to OC progression (157–159). Dong et al (154) identified a direct link between

PCNP and the Wnt pathway: PCNP is overexpressed in OC tissues and

cells (compared with that of paracancerous and IOSE80 cells), and

this overexpression promotes OC cell proliferation, migration and

invasion while suppressing apoptosis (validated in SK-OV-3/A2780

cells and xenograft models). High expression levels of PCNP can

reduce apoptosis by increasing the expression levels of the

transcription factor (STAT) activators of phosphor signal

transducers (153). In addition to

TNF-inducible protein 8-like 2, PCNP is also involved in the immune

response in rheumatoid arthritis (160). Although PCNP is known to mediate

caspase activities, upregulating cleaved caspase-3, −8, and −9

in vitro and in vivo, it remains unclear how PCNP

specifically activates these caspases to induce apoptosis (156). The induction of autophagy and

apoptosis in distinct cell lines, however, implies that alternative

nuclear transporters are involved in the dual behavior of the

protein (156). Overall, however,

further research is needed on the nuclear transportation of PCNP

(Fig. 4; Table II and III).

As analyzed in the present review, OC progression

is driven by dysregulated transcription factors and signaling

pathways, with PEST-NPs emerging as key regulators through their

PTMs. PTMs such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination and SUMOylation

control the stability, activation and intracellular localization of

core PEST-NPs, thereby modulating oncogenic pathways such as the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin pathways to influence OC growth,

metastasis and chemoresistance.

Notably, PCNP and Bmi1, as key PEST-NPs, may hold

translational potential for OC therapy based on their characterized

roles. The direct interaction of PCNP with β-catenin accelerates

nuclear translocation and activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling, a

pathway critical for OC proliferation, migration and invasion.

Targeting PCNP could therefore involve strategies to block its

binding to β-catenin or inhibit its phosphorylation, which

modulates its oncogenic activity in regulating the MAPK and

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways. Given that PCNP is overexpressed in OC

tissues and cells compared with that of their normal counterparts,

such interventions may specifically disrupt tumor-promoting

signaling without affecting normal cells. The ability of Bmi1 to be

overexpressed in metastatic and recurrent OC supports its utility

as a therapeutic target. Inhibiting Bmi1 could reduce its

stabilization via O-GlcNAcylation or block its phosphorylation by

AKT, thereby reversing its oncogenic effects on cell cycle

progression and stemness. This may sensitize OC cells to

platinum-based therapies, as Bmi1 silencing has been shown to

increase platinum susceptibility in preclinical models.

These insights deepen the current understanding of

OC pathogenesis by linking PEST motif-mediated protein dynamics to

tumor behavior, thus underscoring PEST-NPs as valuable diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets. To advance clinical

translation, future research should focus on elucidating the

intricate interactions of PCNP with cancer-related genes and

pathways, validating PEST-NP-targeted strategies in preclinical

models and exploring PEST-NP expression/PTM profiles as predictors

of treatment response, which will serve to bridge the gap between

laboratory research and clinical applications.

Not applicable.

The present work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 31902287 and 81670988), Cultivation

Project for Innovation Team in Teachers' Teaching Proficiency by

Zhengzhou Health College (grant no. 2024jxcxtd01).

Not applicable.

HL, ZLJ, YL, YHZ, MUA and ZDL conceived the study

and drafted the manuscript. MBK, SK and UAKS prepared the figures,

participated in manuscript content revision and table legend

editing. YZ and XYJ provided funding and supervision, reviewed the

manuscript framework, revised key sections and ensured academic

consistency. ZLJ and YL participated in the extensive review,

revision, and figure/table production of the review. Data

authentication is not applicable. All the authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Menon U, Griffin M and Gentry-Maharaj A:

Ovarian cancer screening-current status, future directions. Gynecol

Oncol. 132:490–495. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Gupta KK, Gupta VK and Naumann RW: Ovarian

cancer: Screening and future directions. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

29:195–200. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang MH, Zhang HH, Du XH, Gao J, Li C,

Shi HR and Li SZ: UCHL3 promotes ovarian cancer progression by

stabilizing TRAF2 to activate the NF-κB pathway. Oncogene.

39:322–333. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hubackova M, Vaclavikova R, Ehrlichova M,

Mrhalova M, Kodet R, Kubackova K, Vrána D, Gut I and Soucek P:

Association of superoxide dismutases and NAD(P)H quinone

oxidoreductases with prognosis of patients with breast carcinomas.

Int J Cancer. 130:338–348. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ke Y, Chen X, Su Y, Chen C, Lei S, Xia L,

Wei D, Zhang H, Dong C, Liu X and Yin F: Low expression of SLC7A11

confers drug resistance and worse survival in ovarian cancer via

inhibition of cell autophagy as a competing endogenous RNA. Front

Oncol. 11:7449402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li D, Hong X, Zhao F, Ci X and Zhang S:

Targeting Nrf2 may reverse the drug resistance in ovarian cancer.

Cancer Cell Int. 21:1162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gao Y, Liu X, Li T, Wei L, Yang A, Lu Y,

Zhang J, Li L, Wang S and Yin F: Cross-validation of genes

potentially associated with overall survival and drug resistance in

ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 37:3084–3092. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hydbring P, Castell A and Larsson LG: MYC

modulation around the CDK2/p27/SKP2 axis. Genes (Basel). 8:1742017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ammirante M, Kuraishy AI, Shalapour S,

Strasner A, Ramirez-Sanchez C, Zhang W, Shabaik A and Karin M: An

IKKα-E2F1-BMI1 cascade activated by infiltrating B cells controls

prostate regeneration and tumor recurrence. Genes Dev.

27:1435–1440. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Park JY, Wang PY, Matsumoto T, Sung HJ, Ma

W, Choi JW, Anderson SA, Leary SC, Balaban RS, Kang JG and Hwang

PM: p53 improves aerobic exercise capacity and augments skeletal

muscle mitochondrial DNA content. Circ Res. 105:705–712. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ho SR, Mahanic CS, Lee YJ and Lin WC:

RNF144A, an E3 ubiquitin ligase for DNA-PKcs, promotes apoptosis

during DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:E2646–E2655. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Bakhanashvili M, Grinberg S, Bonda E,

Simon AJ, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S and Rahav G: p53 in mitochondria

enhances the accuracy of DNA synthesis. Cell Death Differ.

15:1865–1874. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nithipongvanitch R, Ittarat W, Velez JM,

Zhao R, St Clair DK and Oberley TD: Evidence for p53 as guardian of

the cardiomyocyte mitochondrial genome following acute adriamycin

treatment. J Histochem Cytochem. 55:629–639. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nie M, Moser BA, Nakamura TM and Boddy MN:

SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase activity can either suppress or

promote genome instability, depending on the nature of the DNA

lesion. PLoS Genet. 13:e10067762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhou ZD, Chan CH, Xiao ZC and Tan EK: Ring

finger protein 146/Iduna is a poly(ADP-ribose) polymer binding and

PARsylation dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase. Cell Adh Migr.

5:463–471. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Freed-Pastor WA and Prives C: Mutant p53:

One name, many proteins. Genes Dev. 26:1268–2686. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kang HC, Lee YI, Shin JH, Andrabi SA, Chi

Z, Gagné JP, Lee Y, Ko HS, Lee BD, Poirier GG, et al: Iduna is a

poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR)-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates

DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:14103–14108. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hu L, Zhang H, Bergholz J, Sun S and Xiao

ZX: MDM2/MDMX: Master negative regulators for p53 and RB. Mol Cell

Oncol. 3:e11066352016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tuna M, Ju Z, Yoshihara K, Amos CI, Tanyi

JL and Mills GB: Clinical relevance of TP53 hotspot mutations in

high-grade serous ovarian cancers. Br J Cancer. 122:405–412. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Afzal A, Sarfraz M, Li GL, Ji SP, Duan SF,

Khan NH, Wu DD and Ji XY: Taking a holistic view of PEST-containing

nuclear protein (PCNP) in cancer biology. Cancer Med. 8:6335–6343.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rogers S, Wells R and Rechsteiner M: Amino

acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: The PEST

hypothesis. Science. 234:364–368. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Roth AF, Sullivan DM and Davis NG: A large

PEST-like sequence directs the ubiquitination, endocytosis, and

vacuolar degradation of the yeast a-factor receptor. J Cell Biol.

142:949–961. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhuang X, Northup JK and Ray K: Large

putative PEST-like sequence motif at the carboxyl tail of human

calcium receptor directs lysosomal degradation and regulates cell

surface receptor level. J Biol Chem. 287:4165–4176. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sekhar KR and Freeman ML: PEST sequences

in proteins involved in cyclic nucleotide signalling pathways. J

Recept Signal Transduct Res. 18:113–132. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bellini E, Pavesi G, Barbiero I, Bergo A,

Chandola C, Nawaz MS, Rusconi L, Stefanelli G, Strollo M, Valente

MM, et al: MeCP2 post-translational modifications: A mechanism to

control its involvement in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis?

Front Cell Neurosci. 8:2362014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bereshchenko OR, Gu W and Dalla-Favera R:

Acetylation inactivates the transcriptional repressor BCL6. Nat

Genet. 32:606–613. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhao JF, Shyue SK and Lee TS: Excess

nitric oxide activates TRPV1-Ca(2+)-calpain signaling and promotes

PEST-dependent degradation of liver X receptor α. Int J Biol Sci.

12:18–29. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu R, Hong J, Xu X, Feng Q, Zhang D, Gu

Y, Shi J, Zhao S, Liu W, Wang X, et al: Gut microbiome and serum

metabolome alterations in obesity and after weight-loss

intervention. Nat Med. 23:859–868. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pan S and Chen R: Pathological implication

of protein post-translational modifications in cancer. Mol Aspects

Med. 86:1010972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Afzal A, Sarfraz M, Wu Z, Wang G and Sun

J: Integrated scientific data bases review on asulacrine and

associated toxicity. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 104:78–86. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lang V, Aillet F, Da Silva-Ferrada E,

Xolalpa W, Zabaleta L, Rivas C and Rodriguez MS: Analysis of PTEN

ubiquitylation and SUMOylation using molecular traps. Methods.

77–78. 112–118. 2015.

|

|

33

|

Li N, Zhang Y, Han X, Liang K, Wang J,

Feng L, Wang W, Songyang Z, Lin C, Yang L, et al: Poly-ADP

ribosylation of PTEN by tankyrases promotes PTEN degradation and

tumor growth. Genes Dev. 29:157–170. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shumway SD, Maki M and Miyamoto S: The

PEST domain of IkappaBalpha is necessary and sufficient for in

vitro degradation by mu-calpain. J Biol Chem. 274:30874–30881.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sarfraz M, Afzal A, Khattak S, Saddozai

UAK, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Madni A, Haleem KS, Duan SF, Wu DD, et al:

Multifaceted behavior of PEST sequence enriched nuclear proteins in

cancer biology and role in gene therapy. J Cell Physiol.

236:1658–1676. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T,

Newmeyer DD and Green DR: PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic

proapoptotic function of p53. Science. 309:1732–1735. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lisachev PD, Pustylnyak VO and Shtark MB:

Mdm2-dependent regulation of p53 expression during long-term

potentiation. Bull Exp Biol Med. 158:333–335. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Geyer RK, Yu ZK and Maki CG: The MDM2

RING-finger domain is required to promote p53 nuclear export. Nat

Cell Biol. 2:569–573. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lu W, Pochampally R, Chen L, Traidej M,

Wang Y and Chen J: Nuclear exclusion of p53 in a subset of tumors

requires MDM2 function. Oncogene. 19:232–240. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang DY, Hong Y, Chen YG, Dong PZ, Liu SY,

Gao YR, Lu D, Li HM, Li T, Guo JC, et al: PEST-containing nuclear

protein regulates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in

lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogenesis. 8:222019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ye J, Zhong L, Xiong L, Li J, Yu L, Dan W,

Yuan Z, Yao J, Zhong P, Liu J, et al: Nuclear import of NLS-RARα is

mediated by importin α/β. Cell Signal. 69:1095672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Panagiotopoulos AA, Polioudaki C, Ntallis

SG, Dellis D, Notas G, Panagiotidis CA, Theodoropoulos PA, Castanas

E and Kampa M: The sequence [EKRKI(E/R)(K/L/R/S/T)] is a nuclear

localization signal for importin 7 binding (NLS7). Biochim Biophys

Acta Gen Subj. 1865:1298512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zheng Y, Yu K, Lin JF, Liang Z, Zhang Q,

Li J, Wu QN, He CY, Lin M, Zhao Q, et al: Deep learning prioritizes

cancer mutations that alter protein nucleocytoplasmic shuttling to

drive tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 16:25112025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lang YD and Jou YS: PSPC1 is a new

contextual determinant of aberrant subcellular translocation of

oncogenes in tumor progression. J Biomed Sci. 28:572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Rubbi CP and Milner J: Disruption of the

nucleolus mediates stabilization of p53 in response to DNA damage

and other stresses. EMBO J. 22:6068–6077. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang X, Blaskovich MA, Forinash KD and

Sebti SM: Withacnistin inhibits recruitment of STAT3 and STAT5 to

growth factor and cytokine receptors and induces regression of

breast tumours. Br J Cancer. 111:894–902. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Baugh EH, Ke H, Levine AJ, Bonneau RA and

Chan CS: Why are there hotspot mutations in the TP53 gene in human

cancers? Cell Death Differ. 25:154–160. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kastan MB and Berkovich E: p53: A

two-faced cancer gene. Nat Cell Biol. 9:489–491. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Levine AJ and Oren M: The first 30 years

of p53: Growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:749–758. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wojnarowicz PM, Oros KK, Quinn MC, Arcand

SL, Gambaro K, Madore J, Birch AH, de Ladurantaye M, Rahimi K,

Provencher DM, et al: The genomic landscape of TP53 and p53

annotated high grade ovarian serous carcinomas from a defined

founder population associated with patient outcome. PLoS One.

7:e454842012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC and

Ledermann JA: Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 384:1376–1388. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Matulonis UA, Sood AK, Fallowfield L,

Howitt BE, Sehouli J and Karlan BY: Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis

Primers. 2:160612016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Joerger AC and Fersht AR: The tumor

suppressor p53: From structures to drug discovery. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 2:a0009192010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhu G, Pan C, Bei JX, Li B, Liang C, Xu Y

and Fu X: Mutant p53 in cancer progression and targeted therapies.

Front Oncol. 10:5951872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Cole AJ, Dwight T, Gill AJ, Dickson KA,

Zhu Y, Clarkson A, Gard GB, Maidens J, Valmadre S, Clifton-Bligh R

and Marsh DJ: Assessing mutant p53 in primary high-grade serous

ovarian cancer using immunohistochemistry and massively parallel

sequencing. Sci Rep. 6:261912016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Flemming A: Cancer: Mutant p53 rescued by

aggregation inhibitor. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 15:852016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Duffy MJ, Synnott NC, O'Grady S and Crown

J: Targeting p53 for the treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol.

79:58–67. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Okal A, Cornillie S, Matissek SJ, Matissek

KJ, Cheatham TE III and Lim CS: Re-engineered p53 chimera with

enhanced homo-oligomerization that maintains tumor suppressor

activity. Mol Pharm. 11:2442–2452. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Okal A, Matissek KJ, Matissek SJ, Price R,

Salama ME, Janát-Amsbury MM and Lim CS: Re-engineered p53 activates

apoptosis in vivo and causes primary tumor regression in a dominant

negative breast cancer xenograft model. Gene Ther. 21:903–912.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Brady CA and Attardi LD: p53 at a glance.

J Cell Sci. 123:2527–2532. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wei H, Qu L, Dai S, Li Y, Wang H, Feng Y,

Chen X, Jiang L, Guo M, Li J, et al: Structural insight into the

molecular mechanism of p53-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Nat

Commun. 12:22802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME and

George DL: Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of

a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 6:443–450. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Heyne K, Schmitt K, Mueller D, Armbruester

V, Mestres P and Roemer K: Resistance of mitochondrial p53 to

dominant inhibition. Mol Cancer. 7:542008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Chen S, Cavazza E, Barlier C, Salleron J,

Filhine-Tresarrieu P, Gavoilles C, Merlin JL and Harlé A: Beside

P53 and PTEN: Identification of molecular alterations of the

RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in high-grade serous

ovarian carcinomas to determine potential novel therapeutic

targets. Oncol Lett. 12:3264–3272. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Toledo F and Wahl GM: MDM2 and MDM4: p53

regulators as targets in anticancer therapy. Int J Biochem Cell

Biol. 39:1476–1482. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Astanehe A, Arenillas D, Wasserman WW,

Leung PC, Dunn SE, Davies BR, Mills GB and Auersperg N: Mechanisms

underlying p53 regulation of PIK3CA transcription in ovarian

surface epithelium and in ovarian cancer. J Cell Sci. 121:664–674.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hu L, Zaloudek C, Mills GB, Gray J and

Jaffe RB: In vivo and in vitro ovarian carcinoma growth inhibition

by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor (LY294002). Clin

Cancer Res. 6:880–886. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Raab M, Kostova I, Peña-Llopis S, Fietz D,

Kressin M, Aberoumandi SM, Ullrich E, Becker S, Sanhaji M and

Strebhardt K: Rescue of p53 functions by in vitro-transcribed mRNA

impedes the growth of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer

Commun (Lond). 44:101–126. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Faramarzi L, Dadashpour M, Sadeghzadeh H,

Mahdavi M and Zarghami N: Enhanced anti-proliferative and

pro-apoptotic effects of metformin encapsulated PLGA-PEG

nanoparticles on SKOV3 human ovarian carcinoma cells. Artif Cells

Nanomed Biotechnol. 47:737–746. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Guo X, Fang Z, Zhang M, Yang D, Wang S and

Liu K: A Co-delivery system of curcumin and p53 for enhancing the

sensitivity of drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin.

Molecules. 25:26212020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Huang X, Cao Z, Qian J, Ding T, Wu Y,

Zhang H, Zhong S, Wang X, Ren X, Zhang W, et al: Nanoreceptors

promote mutant p53 protein degradation by mimicking selective

autophagy receptors. Nat Nanotechnol. 19:545–553. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zhang XF and Gurunathan S: Combination of

salinomycin and silver nanoparticles enhances apoptosis and

autophagy in human ovarian cancer cells: An effective anticancer

therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 11:3655–3675. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wang J, Qu C, Shao X, Song G, Sun J, Shi

D, Jia R, An H and Wang H: Carrier-free nanoprodrug for p53-mutated

tumor therapy via concurrent delivery of zinc-manganese dual ions

and ROS. Bioact Mater. 20:404–417. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lee JM and Johnson JA: An important role

of Nrf2-ARE pathway in the cellular defense mechanism. J Biochem

Mol Biol. 37:139–143. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Castrogiovanni C, Waterschoot B, De Backer

O and Dumont P: Serine 392 phosphorylation modulates p53

mitochondrial translocation and transcription-independent

apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 25:190–203. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Ai G, Dachineni R, Kumar DR, Marimuthu S,

Alfonso LF and Bhat GJ: Aspirin acetylates wild type and mutant p53

in colon cancer cells: Identification of aspirin acetylated sites

on recombinant p53. Tumour Biol. 37:6007–6016. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Oreskes N: Beyond the ivory tower. The

scientific consensus on climate change. Science. 306:16862004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Haddadi N, Lin Y, Travis G, Simpson AM,

Nassif NT and McGowan EM: PTEN/PTENP1: ‘Regulating the regulator of

RTK-dependent PI3K/Akt signalling’, new targets for cancer therapy.

Mol Cancer. 17:372018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jiang C, Song Y, Rorive S, Allard J, Tika

E, Zahedi Z, Dubois C, Salmon I, Sifrim A and Blanpain C: Innate

immunity and the NF-κB pathway control prostate stem cell

plasticity, reprogramming and tumor initiation. Nat Cancer.

6:1537–1558. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Ren G, Chen J, Pu Y, Yang EJ, Tao S, Mou

PK, Chen LJ, Zhu W, Chan KL, Luo G, et al: BET inhibition induces

synthetic lethality in PTEN deficient colorectal cancers via dual

action on p21CIP1/WAF1. Int J Biol Sci. 20:1978–1991.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Georgescu MM, Kirsch KH, Akagi T, Shishido

T and Hanafusa H: The tumor-suppressor activity of PTEN is

regulated by its carboxyl-terminal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

96:10182–10187. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Meyer RD, Srinivasan S, Singh AJ, Mahoney

JE, Gharahassanlou KR and Rahimi N: PEST motif serine and tyrosine

phosphorylation controls vascular endothelial growth factor

receptor 2 stability and downregulation. Mol Cell Biol.

31:2010–2025. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Trotman LC, Wang X, Alimonti A, Chen Z,

Teruya-Feldstein J, Yang H, Pavletich NP, Carver BS, Cordon-Cardo

C, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al: Ubiquitination regulates PTEN

nuclear import and tumor suppression. Cell. 128:141–156. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Hu X, Xu X, Zeng X, Jin R, Wang S, Jiang

H, Tang Y, Chen G, Wei J, Chen T and Chen Q: Gut microbiota

dysbiosis promotes the development of epithelial ovarian cancer via

regulating Hedgehog signaling pathway. Gut Microbes.

15:22210932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Willner J, Wurz K, Allison KH, Galic V,

Garcia RL, Goff BA and Swisher EM: Alternate molecular genetic

pathways in ovarian carcinomas of common histological types. Hum

Pathol. 38:607–613. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Karlsson T, Krakstad C, Tangen IL, Hoivik

EA, Pollock PM, Salvesen HB and Lewis AE: Endometrial cancer cells

exhibit high expression of p110β and its selective inhibition

induces variable responses on PI3K signaling, cell survival and

proliferation. Oncotarget. 8:3881–3894. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Singer G, Oldt R III, Cohen Y, Wang BG,

Sidransky D, Kurman RJ and Shih IeM: Mutations in BRAF and KRAS

characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 95:484–486. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Dinulescu DM, Ince TA, Quade BJ, Shafer

SA, Crowley D and Jacks T: Role of K-ras and Pten in the

development of mouse models of endometriosis and endometrioid

ovarian cancer. Nat Med. 11:63–70. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Zhao X, Lai H, Li G, Qin Y, Chen R, Labrie

M, Stommel JM, Mills GB, Ma D, Gao Q and Fang Y: Rictor

orchestrates β-catenin/FOXO balance by maintaining redox

homeostasis during development of ovarian cancer. Oncogene.

44:1820–1832. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Tamura T, Nagai S, Masuda K, Imaeda K,

Sugihara E, Yamasaki J, Kawaida M, Otsuki Y, Suina K, Nobusue H, et

al: mTOR-mediated p62/SQSTM1 stabilization confers a robust

survival mechanism for ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 616:2175652025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Trillsch F, Czogalla B, Mahner S, Loidl V,

Reuss A, du Bois A, Sehouli J, Raspagliesi F, Meier W, Cibula D, et

al: Risk factors for anastomotic leakage and its impact on survival

outcomes in radical multivisceral surgery for advanced ovarian

cancer: An AGO-OVAR.OP3/LION exploratory analysis. Int J Surg.

111:2914–2922. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Russo A, Czarnecki AA, Dean M, Modi DA,

Lantvit DD, Hardy L, Baligod S, Davis DA, Wei JJ and Burdette JE:

PTEN loss in the fallopian tube induces hyperplasia and ovarian

tumor formation. Oncogene. 37:1976–1990. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Coscia F, Watters KM, Curtis M, Eckert MA,

Chiang CY, Tyanova S, Montag A, Lastra RR, Lengyel E and Mann M:

Integrative proteomic profiling of ovarian cancer cell lines

reveals precursor cell associated proteins and functional status.

Nat Commun. 7:126452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Labidi-Galy SI, Papp E, Hallberg D,

Niknafs N, Adleff V, Noe M, Bhattacharya R, Novak M, Jones S,

Phallen J, et al: High grade serous ovarian carcinomas originate in

the fallopian tube. Nat Commun. 8:10932017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Roh MH, Yassin Y, Miron A, Mehra KK,

Mehrad M, Monte NM, Mutter GL, Nucci MR, Ning G, Mckeon FD, et al:

High-grade fimbrial-ovarian carcinomas are unified by altered p53,

PTEN and PAX2 expression. Mod Pathol. 23:1316–1324. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Dean M, Jin V, Bergsten TM, Austin JR,

Lantvit DD, Russo A and Burdette JE: Loss of PTEN in fallopian tube

epithelium results in multicellular tumor spheroid formation and

metastasis to the ovary. Cancers (Basel). 11:8842019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Zhang L, Ma T, Brozick J, Babalola K,

Budiu R, Tseng G and Vlad AM: Effects of Kras activation and Pten

deletion alone or in combination on MUC1 biology and

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer. Oncogene.

35:5010–5020. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Alkema MJ, Wiegant J, Raap AK, Berns A and

van Lohuizen M: Characterization and chromosomal localization of

the human proto-oncogene BMI-1. Hum Mol Genet. 2:1597–1603. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Calao M, Sekyere EO, Cui HJ, Cheung BB,

Thomas WD, Keating J, Chen JB, Raif A, Jankowski K, Davies NP, et

al: Direct effects of Bmi1 on p53 protein stability inactivates

oncoprotein stress responses in embryonal cancer precursor cells at

tumor initiation. Oncogene. 32:3616–3626. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Su WJ, Fang JS, Cheng F, Liu C, Zhou F and

Zhang J: RNF2/Ring1b negatively regulates p53 expression in

selective cancer cell types to promote tumor development. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 110:1720–1725. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Ginjala V, Nacerddine K, Kulkarni A, Oza

J, Hill SJ, Yao M, Citterio E, van Lohuizen M and Ganesan S: BMI1

is recruited to DNA breaks and contributes to DNA damage-induced

H2A ubiquitination and repair. Mol Cell Biol. 31:1972–1982. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Itahana K, Zou Y, Itahana Y, Martinez JL,

Beausejour C, Jacobs JJ, Van Lohuizen M, Band V, Campisi J and

Dimri GP: Control of the replicative life span of human fibroblasts

by p16 and the polycomb protein Bmi-1. Mol Cell Biol. 23:389–401.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Yadav AK, Sahasrabuddhe AA, Dimri M, Bommi

PV, Sainger R and Dimri GP: Deletion analysis of BMI1 oncoprotein

identifies its negative regulatory domain. Mol Cancer. 9:1582010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Jacobs JJ, Scheijen B, Voncken JW, Kieboom

K, Berns A and van Lohuizen M: Bmi-1 collaborates with c-Myc in

tumorigenesis by inhibiting c-Myc-induced apoptosis via INK4a/ARF.

Genes Dev. 13:2678–2690. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Song LB, Li J, Liao WT, Feng Y, Yu CP, Hu

LJ, Kong QL, Xu LH, Zhang X, Liu WL, et al: The polycomb group

protein Bmi-1 represses the tumor suppressor PTEN and induces

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human nasopharyngeal

epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 119:3626–3636. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Bhattacharyya J, Mihara K, Ohtsubo M,

Yasunaga S, Takei Y, Yanagihara K, Sakai A, Hoshi M, Takihara Y and

Kimura A: Overexpression of BMI-1 correlates with drug resistance

in B-cell lymphoma cells through the stabilization of survivin

expression. Cancer Sci. 103:34–41. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Fan C, He L, Kapoor A, Gillis A, Rybak AP,

Cutz JC and Tang D: Bmi1 promotes prostate tumorigenesis via

inhibiting p16(INK4A) and p14(ARF) expression. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1782:642–648. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Vonlanthen S, Heighway J, Altermatt HJ,

Gugger M, Kappeler A, Borner MM, van Lohuizen M and Betticher DC:

The bmi-1 oncoprotein is differentially expressed in non-small cell

lung cancer and correlates with INK4A-ARF locus expression. Br J

Cancer. 84:1372–1376. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Song LB, Zeng MS, Liao WT, Zhang L, Mo HY,

Liu WL, Shao JY, Wu QL, Li MZ, Xia YF, et al: Bmi-1 is a novel

molecular marker of nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression and

immortalizes primary human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Cancer

Res. 66:6225–6232. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Fasano CA, Dimos JT, Ivanova NB, Lowry N,

Lemischka IR and Temple S: shRNA knockdown of Bmi-1 reveals a

critical role for p21-Rb pathway in NSC self-renewal during

development. Cell Stem Cell. 1:87–99. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Mao L, Ding J, Perdue A, Yang L, Zha Y,

Ren M, Huang S, Cui H and Ding HF: Cyclin E1 is a common target of

BMI1 and MYCN and a prognostic marker for neuroblastoma

progression. Oncogene. 31:3785–3795. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Dimri GP, Martinez JL, Jacobs JJ, Keblusek

P, Itahana K, Van Lohuizen M, Campisi J, Wazer DE and Band V: The

Bmi-1 oncogene induces telomerase activity and immortalizes human

mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 62:4736–4745. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Ismail IH, Gagné JP, Caron MC, McDonald D,

Xu Z, Masson JY, Poirier GG and Hendzel MJ: CBX4-mediated SUMO

modification regulates BMI1 recruitment at sites of DNA damage.

Nucleic Acids Res. 40:5497–5510. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Voncken JW, Niessen H, Neufeld B,

Rennefahrt U, Dahlmans V, Kubben N, Holzer B, Ludwig S and Rapp UR:

MAPKAP kinase 3pK phosphorylates and regulates chromatin

association of the polycomb group protein Bmi1. J Biol Chem.

280:5178–5187. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Bruggeman SW, Hulsman D, Tanger E, Buckle