Introduction

Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (NKTCL) represents a

rare and highly aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)

with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. The incidence of NKTCL

exhibits a predilection for certain geographical regions, such as

Asia and Latin America, with relatively fewer cases reported in

Europe and North America. Within the Chinese population, NKTCL

accounts for 12–17% of NHL cases and 55–61% of peripheral T-cell

lymphoma cases (1,2).

The therapeutic strategies for NKTCL vary based on

disease staging, and no standard regimen has been established.

Combined radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy are recommended for

patients with early-stage (Ann Arbor stage I/II) (3) disease, but systemic therapy is

recommended for patients with advanced-stage disease (4,5). The

success of early-stage NKTCL treatment hinges upon the irradiation

field and dosage, which are associated with local control rates and

prognosis (6). The optimal

chemotherapy regimens for NKTCL include those incorporating

pegaspargase, such as SMILE (dexamethasone, methotrexate,

ifosfamide, L-asparaginase and etoposide) (7), P-Gemox (gemcitabine, pegaspargase and

oxaliplatin) (8), P-GDP

(dexamethasone, cisplatin, gemcitabine and pegaspargase) (9) and AspMetDex (L-asparaginase,

methotrexate and dexamethasone) regimens (10). Largely variable effective results

have been reported for these regimens (11); however, a standard treatment for

NKTCL has not been established.

Several prognostic models have been developed for

patients with NKTCL. For example, the international prognostic

index (IPI) and Korean Prognostic Index are useful for patients

with anthracycline-containing response (12), and the prognostic index for NKTCL

(PINK) and the prognostic index for NKTCL with extended features

(PINK-E) were developed for patients treated with

non-anthracycline-containing regimens (13,14).

However, the most accurate model is yet to be determined.

The present study performed a retrospective analysis

of patients with NKTCL who received treatment at the Cancer Center,

Union Hospital, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

(Wuhan, China) between June 2013 and June 2022. The aim was to

assess the clinical features, treatment outcomes and prognostic

factors of NKTCL, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of

this aggressive disease.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients diagnosed with NKTCL between June 2013 and

June 2022 at the Cancer Center Union Hospital, Huazhong University

of Science and Technology, were identified, and those that met the

following criteria were included: i) Histologically confirmed NKTCL

according to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors

of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues (15); ii) ≥1 type of antitumor therapy

administered; and iii) follow-up completed and clinical data

available. The sample size was determined by the total number of

eligible cases meeting the inclusion criteria during this period.

The clinical data were retrieved from electronic medical records,

including sex, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance

status (ECOG PS) (16), disease

staging, involved anatomical sites, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

levels, prognostic indicators, EBV DNA levels, hematological

characteristics, presence of B symptoms and radiological

manifestations.

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong

University of Science and Technology (approval no. 20240986).

Written informed consent was waived, as there were no conflicts of

interest or potential harm to patients, and the confidentiality of

patient data was guaranteed in accordance with the requirements of

the Ethics Committee.

Treatments

Treatment strategies were implemented based on the

stage classification of each patient. For those presenting with

early-stage disease, a radiation regimen consisting of 50–54 Gy

delivered over 25–27 fractions was administered concurrently with

weekly intravenous cisplatin at a dose of 30 mg/m2.

Following completion of radiation therapy, patients underwent 3–4

cycles of pegaspargase-based chemotherapy (dosing schedule as

described for those with advanced-stage disease).

By contrast, patients diagnosed with advanced-stage

disease received chemotherapy as the primary treatment modality.

The selection of chemotherapy regimens was determined in alignment

with the patient's individual preferences. The combined

chemotherapy protocols employed included PIDE (2,500

IU/m2 pegaspargase with a maximum dose of 3,750 IU

administered intramuscularly on day 1; 1g/m2 ifosfamide

administered intravenously on days 2–4; 40 mg dexamethasone

administered orally on days 1–4; and 100 mg/m2 etoposide

administered intravenously on days 2–4), P-GDP (2,500

IU/m2 pegaspargase with a maximum dose of 3,750 IU

administered intramuscularly on day 1; 1,000 mg/m2

gemcitabine administered intravenously on days 1–8; 40 mg

dexamethasone administered orally on days 1–4; and 25

mg/m2 cisplatin administered intravenously on days 1–3),

P-Gemox (2,500 IU/m2 pegaspargase administered

intramuscularly on day 1; 1,000 mg/m2 gemcitabine

administered intravenously on days 1–8; and 100 mg/m2

oxaliplatin administered intravenously on days 1–8) and PPME (2,500

IU/m2 pegaspargase administered intramuscularly on day

1; 100 mg/m2 etoposide administered intravenously on

days 1–3; 3 g/m2 high-dose methotrexate administered

intravenously on day 4; and 200 mg camrelizumab administered

intravenously on day 7). The chemotherapy cycles were repeated

every 21 days. Regimens were designed by investigators based on

prior literature (6–9), with P-Gemox, PIDE and P-GDP adapted

from pegaspargase-based protocols and PPME incorporating immune

checkpoint blockade to reflect immunotherapy advances. Response

evaluation was performed following the completion of RT or after

every two cycles of chemotherapy.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

26.0 software (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 9 software

(Dotmatics). Pearson's χ2 test was used for comparing

data from different groups. Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank

test were used to evaluate OS and PFS. To assess prognostic factors

associated with OS and PFS, Cox proportional hazards regression was

employed. Both univariate and multivariate Cox analyses were

performed to identify variables with significant prognostic values.

To account for multiple comparisons, the Benjamini-Hochberg false

discovery rate correction was applied separately to P-values from

multivariate Cox models for PFS and OS. Furthermore, an interaction

effect analysis was performed using R software (version 4.3.2;

Posit Software, PBC). Specifically, Cox proportional hazards

regression models (survival package) were fitted for both PFS and

OS, and multiplicative interaction terms (stage × age, stage × LDH,

stage × EBV DNA level and EBV DNA × age) were included in the

multivariate models. Wald tests were applied to evaluate the

statistical significance of the interaction terms, and hazard

ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

For the retrospective sample size, an events per covariate value of

5–10 was targeted to ensure reliable multivariate Cox model

estimates for PFS and OS, with sufficient power to detect a hazard

ratio of 2.0 (α=0.05). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of patients

A retrospective analysis was performed on 200

individuals newly diagnosed with NKTCL who were admitted to the

Cancer Center at Union Hospital between June 2013 and June 2022.

Among the initial cohort, 29 patients were excluded from the study:

12 individuals did not undergo any form of treatment, whilst 17

received inadequate treatment. A total of 171 patients were

subsequently included in the final analysis. Within this cohort,

there were 114 male patients (66.7%) and 57 female patients

(33.3%), resulting in a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. The mean age

of the patients was 45 years, with an age range of 16–77 years. The

distribution of disease stages revealed that 117 patients presented

with early-stage disease (stage I/II; 68.4%), whilst 54 patients

were classified as having advanced-stage disease (stage III/IV;

31.6%). Among the patient population, 60.2% (103/171) exhibited B

symptoms, whilst elevated LDH levels were observed in 19.3% of

patients (33/171). ECOG PS scores of 0–1 were recorded for 93.6% of

individuals (160/171). Additionally, most patients were categorized

as having a low-to-moderate risk based on the IPI (86.0%; 147/171),

PINK (71.3%; 122/171) and PINK-E scores (65.5%; 112/171). Notably,

baseline assessments revealed the presence of EBV DNA in the

bloodstream of all patients except for 5 individuals (2.9%). A

detailed summary of the clinical characteristics of the patient

cohort is provided in Table I.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of patients

with natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (n=171). |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients

with natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (n=171).

|

Characteristics | Patients, n

(%) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 114 (66.7) |

|

Female | 57 (33.3) |

| Age, years |

|

|

≥60 | 33 (19.3) |

|

<60 | 138 (80.7) |

| B symptoms |

|

|

Yes | 103 (60.2) |

| No | 68 (39.8) |

| Distant lymph node

involvement |

|

|

Yes | 49 (28.7) |

| No | 122 (71.3) |

| LDH |

|

|

Elevated | 33 (19.3) |

|

Normal | 138 (80.7) |

| Ann Arbor

Stage |

|

|

I/II | 117 (68.4) |

|

III/IV | 54 (31.6) |

| Bone marrow

involvement |

|

|

Yes | 18 (10.5) |

| No | 153 (89.5) |

| ECOG PS |

|

|

0-1 | 160 (93.6) |

| ≥2 | 11 (6.4) |

| IPI |

|

|

0-2 | 147 (86.0) |

|

3-5 | 24 (14.0) |

| PINK |

|

|

0-2 | 122 (71.3) |

|

3-5 | 49 (28.7) |

| PINK-E |

|

|

0-2 | 114 (66.7) |

|

3-5 | 57 (33.3) |

| Baseline serum EBV

DNA |

|

|

Positive | 106 (62.0) |

|

Negative | 65 (38.0) |

Treatment responses

Treatment response in patients with early-stage

NKTCL

A total of 117 patients diagnosed with early-stage

NKTCL were treated with combined RT and chemotherapy. The ORR

achieved through this combined treatment approach was 98.2%. In

terms of the chemotherapy regimens employed, the patient cohort was

stratified as follows: 66 individuals (56.4%) were subjected to the

PIDE protocol, 27 patients (23.1%) received P-GDP, 13 patients

(11.1%) were treated with the PPME and 11 patients (9.4%) underwent

P-Gemox treatment. Notably, patients administered PIDE and PPME

exhibited an ORR of 100%, whilst those receiving P-GDP and P-Gemox

demonstrated response rates of 96.4 and 90.9%, respectively.

Detailed findings pertaining to treatment responses are presented

in Table II.

| Table II.Treatment response in patients with

early-stage natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. |

Table II.

Treatment response in patients with

early-stage natural killer/T-cell lymphoma.

| Treatment | CR, n (%) | PR, n (%) | SD, n (%) | PD, n (%) |

|---|

| PIDE (n=66) | 66 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P-GDP (n=27) | 26 (96.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) |

| PPME (n=13) | 13 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gemox (n=11) | 10 (90.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) |

Treatment response in patients with

advanced-stage NKTCL

A total of 54 patients diagnosed with advanced-stage

NKTCL were subjected to chemotherapy, either as a standalone

treatment or in combination with RT. The choice of treatment

modality was made in consultation with each patient, considering

individual preferences. The ORR achieved through these

interventions was determined to be 92.5%. In terms of the specific

chemotherapy regimens employed, patient management encompassed the

following strategies: 17 individuals (31.5%) underwent treatment

with PPME, 13 patients (24.1%) were administered P-GDP, 12 patients

(22.2%) received PIDE, 8 individuals (14.8%) were treated with

P-Gemox, 3 patients (5.6%) received AspaMetDex and 1 patient (1.9%)

was enrolled in a clinical trial. A total of 18 patients underwent

RT after completing the chemotherapy regimen. Notably, patients

managed with PPME exhibited an ORR of 100%, with a complete

response (CR) rate of 94.1%. Those subjected to P-GDP demonstrated

an ORR of 92.3%, whilst individuals receiving PIDE achieved an ORR

of 100%. Patients treated with P-Gemox exhibited an ORR of 87.5%,

whilst those receiving AspaMetDex demonstrated an ORR of 66.7%. The

sole patient participating in the clinical trial experienced

progressive disease. Detailed findings regarding treatment

responses are presented in Table

III.

| Table III.Treatment response in patients with

advanced-stage natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. |

Table III.

Treatment response in patients with

advanced-stage natural killer/T-cell lymphoma.

| Treatment | CR, n (%) | PR, n (%) | SD, n (%) | PD, n (%) |

|---|

| PPME (n=17) | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P-GDP (n=13) | 12 (92.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| PIDE (n=12) | 12 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P-Gemox (n=8) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| AspaMetDex

(n=3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) |

Survival outcomes

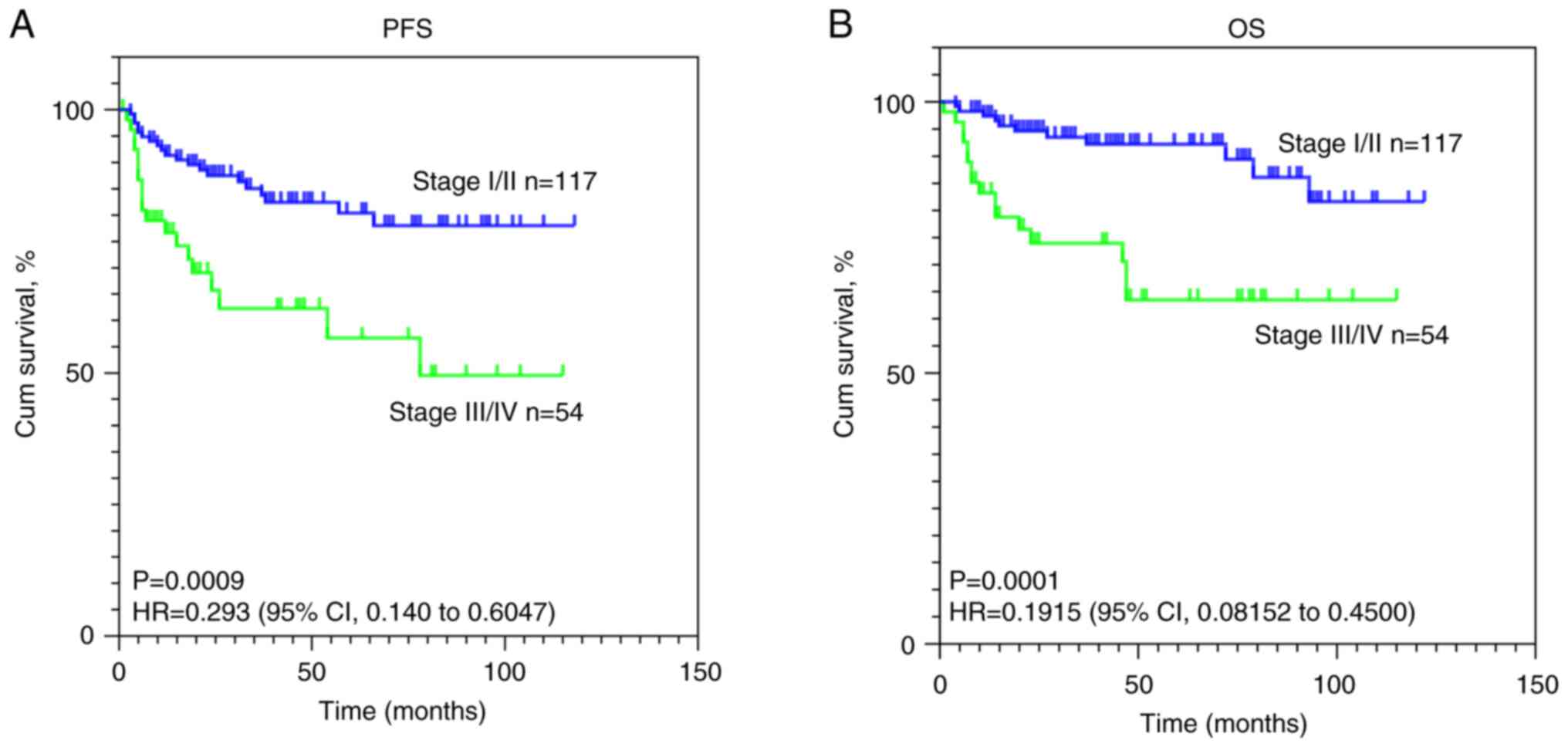

Over a median follow-up period of 47.5 months

(range, 2–122 months), the mortality rate among patients was 15.8%

(27/171). Of these cases, 26 deaths were attributed to disease

progression, whilst 1 patient death was associated with an

infection. Among the deceased, 11 patients were in the early-stage

category (11/117; 9.4%) and 16 were classified as advanced-stage

patients (16/54; 29.6%). A total of 39 patients experienced disease

progression, accounting for 22.8% of the total patient cohort.

Specifically, 20 cases of disease progression were observed within

the early-stage group (20/117; 17.1%) and 19 instances were

recorded among the advanced-stage patients (19/54; 35.2%). The

4-year PFS and OS rates for the entire patient cohort were 76.7%

(95% CI, 69.8–83.6%) and 83.3% (95% CI, 77.1–89.6%), respectively.

Furthermore, the 4-year PFS rate was 82.5% (95% CI, 75.1–89.9%) for

patients in the early-stage group and 62.3% (95% CI, 47.4–77.2%)

for those in the advanced-stage group. The 4-year OS rate was

recorded as 92.2% (95% CI, 86.9–97.5%) for the early-stage patients

and 63.5% (95% CI, 48.2–78.8%) for the advanced-stage cohort.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS and OS are visually depicted in

Fig. 1. The statistical analysis

using the log-rank test indicated significant differences in

survival curves (both P<0.001) for both OS and PFS based on

stage.

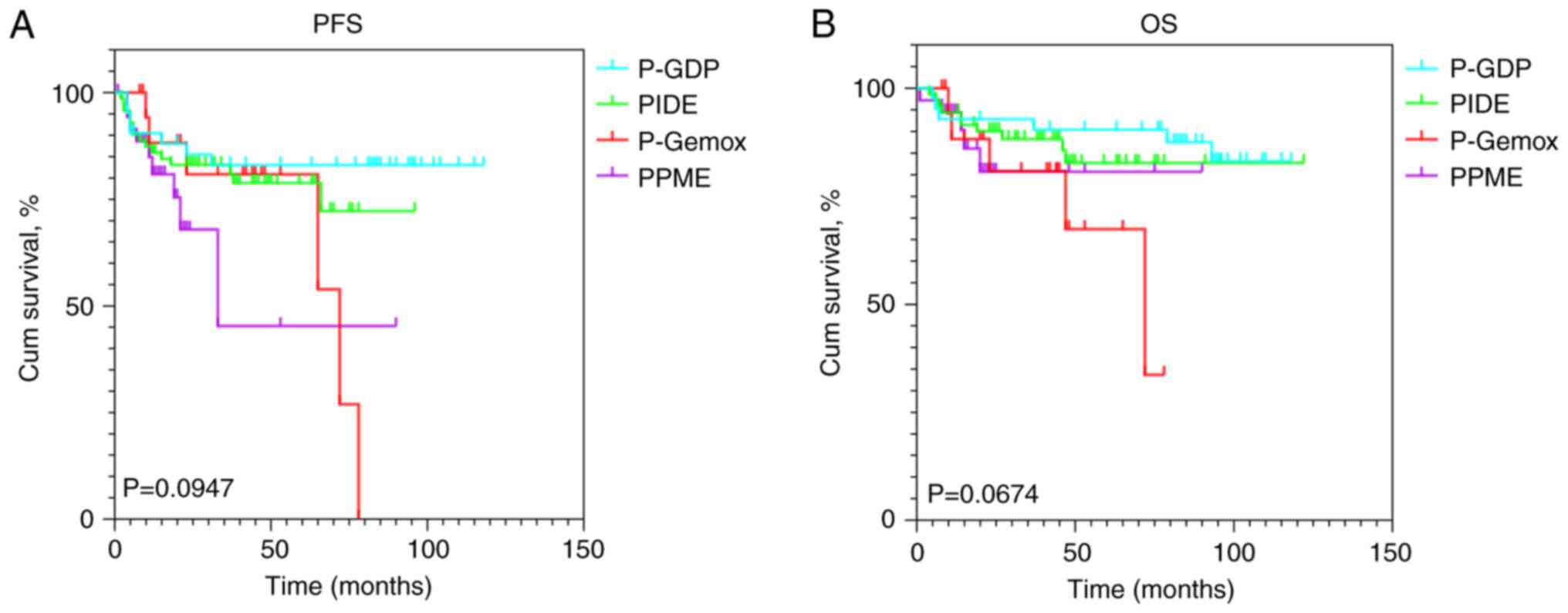

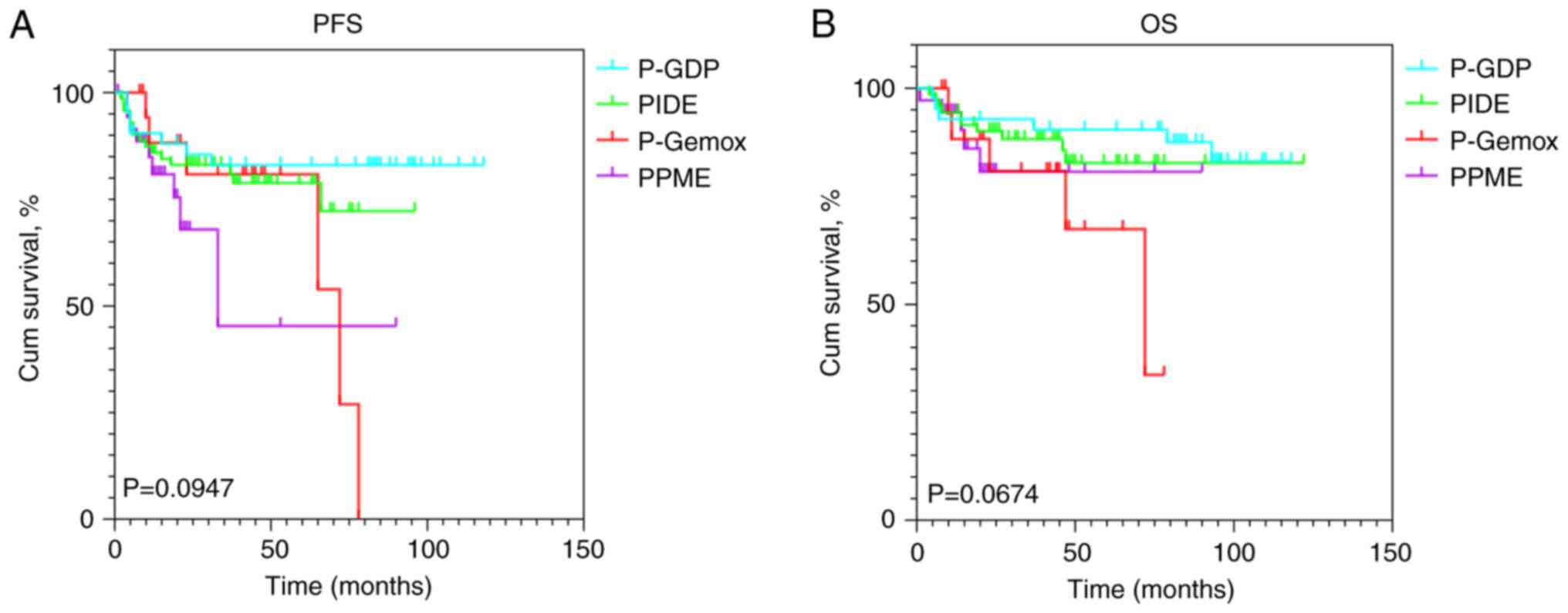

To determine if treatment regimen choice influenced

survival outcomes in NKTCL, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were

generated for four chemotherapy regimens (P-Gemox, PIDE, P-GDP and

PPME) and compared using log-rank tests. The analysis revealed no

significant differences in PFS (P>0.05) or OS (P>0.05) across

the regimens (Fig. 2), indicating

that the treatment regimen did not significantly impact survival

outcomes in this cohort.

| Figure 2.Kaplan-Meier survival curves of (A)

PFS and (B) OS stratified by chemotherapy regimens, including PIDE,

P-GDP, P-Gemox and PPME. P-GDP, pegaspargase, gemcitabine,

dexamethasone, and cisplatin; PIDE, pegaspargase, ifosfamide,

dexamethasone, and etoposide; P-Gemox, pegaspargase, gemcitabine,

and oxaliplatin; PPME: pegaspargase, etoposide, high-dose

methotrexate, and camrelizumab; PFS, progression-free survival; OS,

overall survival; cum, cumulative. |

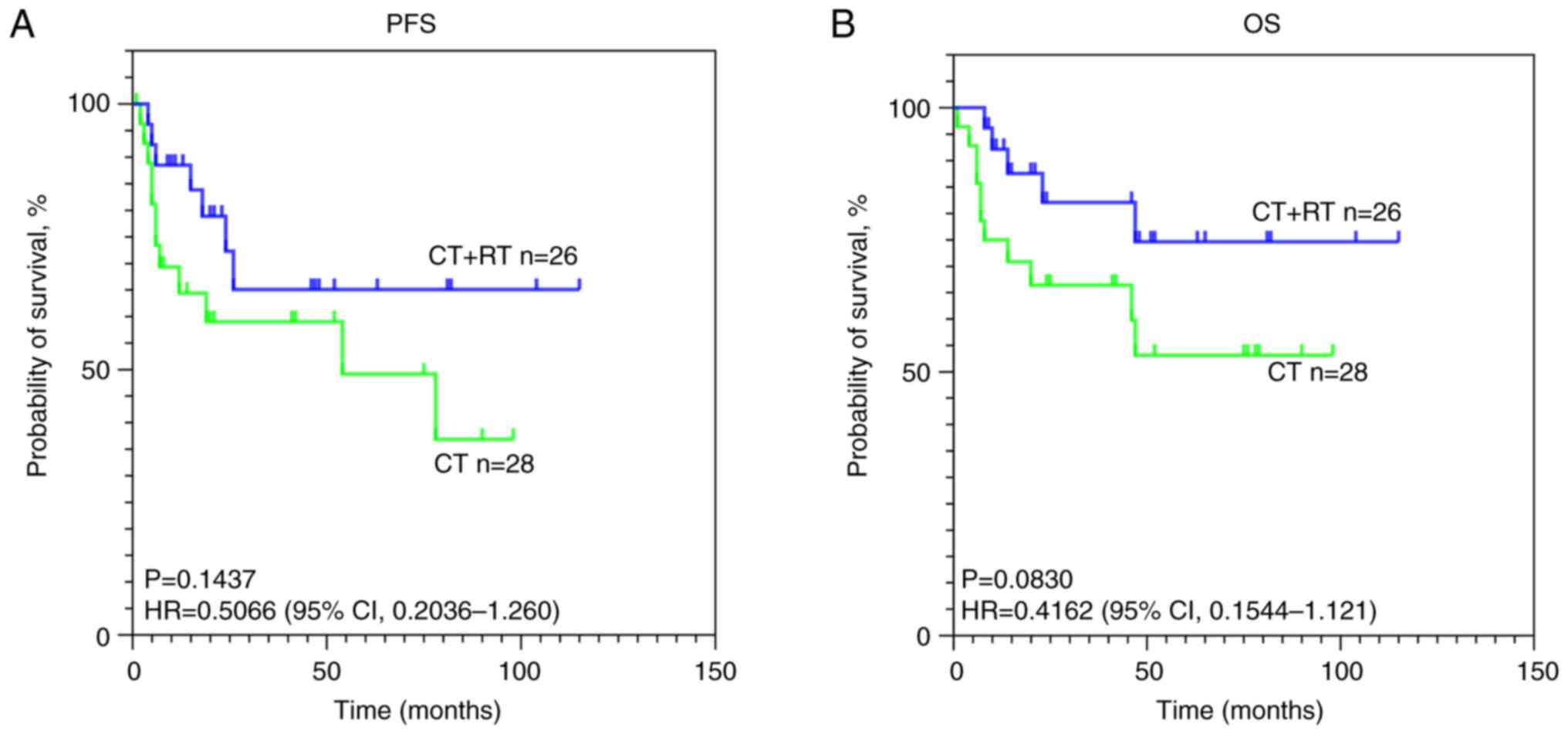

In patients with advanced-stage disease, whether

chemotherapy combined with RT could improve PFS and OS was

analyzed. Although the differences did not reach statistical

significance, a clear trend toward improved prognosis was observed

in patients receiving chemoradiotherapy. Kaplan-Meier estimates of

PFS and OS are presented in Fig.

3.

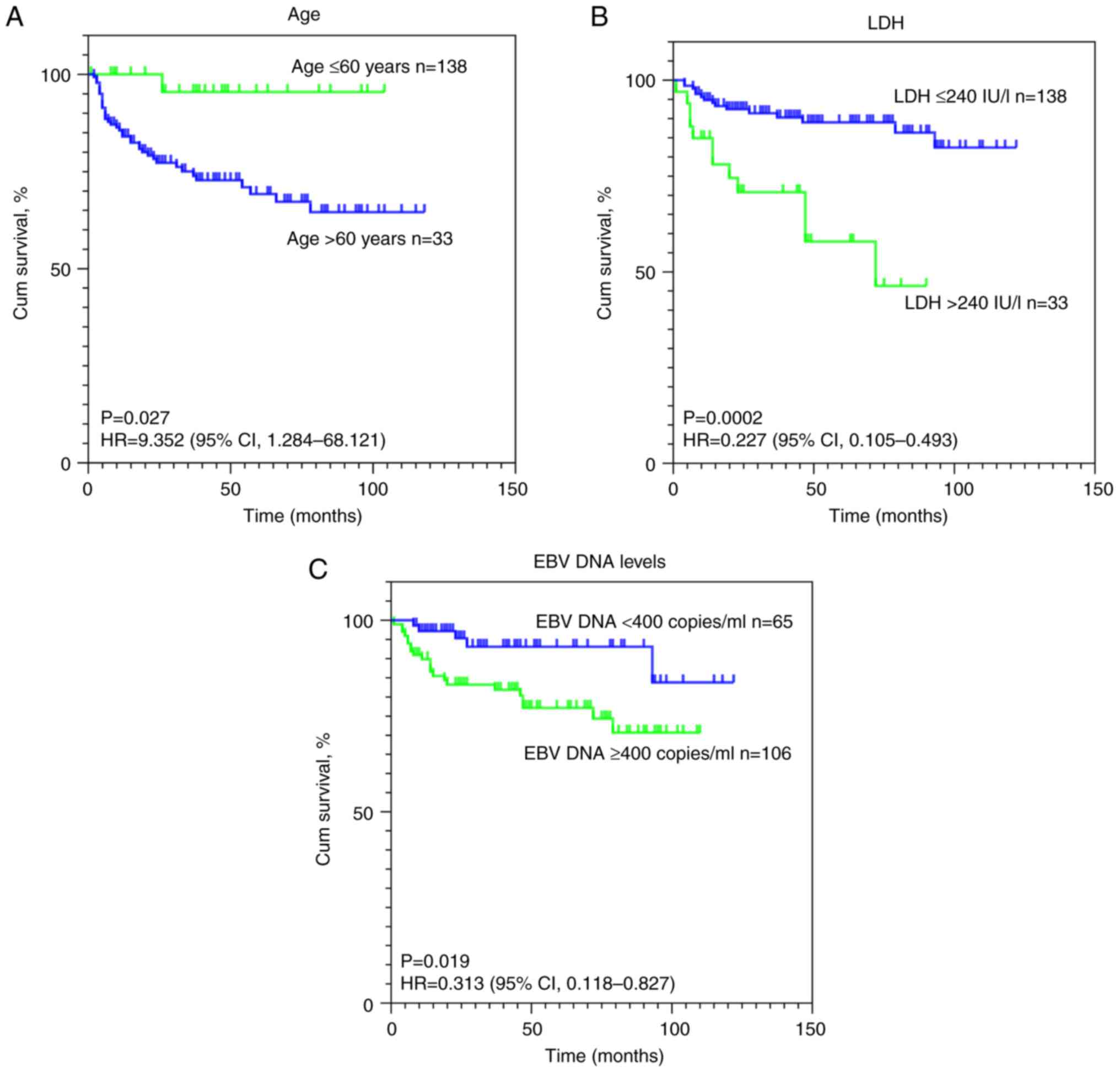

Prognosis

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed

to identify the prognostic factors influencing OS and PFS in

patients with NKTCL. The univariate analysis revealed that an age

of >60 years and stage III/IV disease were adverse prognostic

indicators for PFS in patients with NKTCL, whilst elevated LDH

levels, stage III/IV disease and high EBV DNA levels were

identified as adverse prognostic factors for OS (Table IV). Subsequent multivariate

analysis demonstrated that an age of >60 years and stage III/IV

disease were independent unfavorable prognostic factors for PFS,

whilst elevated LDH levels and stage III/IV disease were

established as independent adverse prognostic factors for OS

(Table V). Given that treatment

modality had been previously demonstrated to exert no significant

impact on patient prognosis in both the univariate analyses and

Kaplan-Meier survival assessments, analysis of chemotherapy

regimens as a prognostic factor was excluded from the subsequent

multivariate analysis. The survival curves delineating the impact

of these prognostic factors are visually presented in Fig. 4. Interaction effects among clinical

variables (stage × age, stage × LDH, stage × EBV DNA and EBV DNA ×

age) were evaluated in multivariate Cox models. No significant

interactions were observed, as shown in Fig. S1 and Table SI. The multivariate Cox models,

adjusting for five covariates, yielded 7.8 (PFS) and 5.4 (OS)

events per covariate, supporting reliable estimates based on the

current sample size.

| Table IV.Univariate analysis of prognosis

factors associated with survival. |

Table IV.

Univariate analysis of prognosis

factors associated with survival.

|

| PFS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 1.249

(0.655–2.383) | 0.499 | 1.193

(0.546–2.607) | 0.658 |

| Age (>60 vs. ≤60

years) | 9.352

(1.284–68.121) | 0.027a | 1.293

(0.447–3.740) | 0.636 |

| Stage (I/II vs.

III/IV) | 0.362

(0.192–0.677) | 0.002a | 0.251

(0.116–0.544) |

<0.001a |

| ECOG PS (0/1 vs.

≥2) | 0.910

(0.279–2.965) | 0.876 | 0.597

(0.179–1.989) | 0.401 |

| B symptoms (no vs.

yes) | 0.729

(0.374–1.420) | 0.353 | 0.623

(0.273–1.424) | 0.262 |

| LDH (≤240 vs.

>240 IU/l) | 0.662

(0.314–1.395) | 0.278 | 0.227

(0.105–0.493) |

<0.001a |

| EBV DNA levels

(<400 vs. ≥400 copies/ml) | 0.669

(0.344–1.304) | 0.802 | 0.313

(0.118–0.827) | 0.019a |

| Chemotherapy

regimen | - | 0.053 | - | 0.297 |

| PGDP

vs. PIDE | 1.771

(0.697–4.504) | 0.230 | 1.697

(0.565–5.098) | 0.346 |

| PGDP

vs. P-Gemox | 2.914

(0.944–8.997) | 0.063 | 3.611

(1.005–12.97) | 0.051 |

| PGDP

vs. PPME | 3.431

(1.196–9.841) | 0.052 | 2.500

(0.685–9.118) | 0.165 |

| Table V.Multivariate analysis of prognosis

factors associated with survival. |

Table V.

Multivariate analysis of prognosis

factors associated with survival.

|

| PFS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | Bonferroni-Hochberg

adjusted P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | Bonferroni-Hochberg

adjusted P-value |

|---|

| Sex (female vs.

male) | 1.399

(0.692–2.828) | 0.350 | - | 1.194

(0.525–2.712) | 0.672 | - |

| Age (>60 vs. ≤60

years) | 9.877

(1.305–74.732) | 0.027a | 0.036a | 1.113

(0.364–3.405) | 0.851 | - |

| Stage (I/II vs.

III/IV) | 0.311

(0.143–0.676) | 0.003a | 0.012a | 0.292

(0.112–0.761) | 0.012a | 0.024a |

| ECOG PS (0/1 vs.

2) | 1.070

(0.266–4.312) | 0.924 | - | 1.106

(0.284–4.315) | 0.884 | - |

| B symptoms (no vs.

yes) | 0.656

(0.333–1.292) | 0.223 | - | 0.570

(0.247–1.315) | 0.188 | - |

| LDH (≤240 vs.

>240 IU/l) | 1.150

(0.416–3.182) | 0.788 | - | 0.361

(0.136–0.956) | 0.040a | 0.040a |

| EBV DNA levels

(<400 vs. ≥400 copies/ml) | 0.654

(0.324–1.321) | 0.236 | - | 0.420

(0.152–1.164) | 0.095 | - |

Discussion

NKTCL is a rare and aggressive subtype of NHL,

typically characterized by a poor prognosis. The present study

performed a retrospective review of a cohort comprising 171

patients with NKTCL, aiming to analyze their clinical

characteristics, evaluate the efficacy of asparaginase-based

treatment regimens in improving survival rates, and investigate

determinants influencing the survival. The findings demonstrated

that the median age of onset for NKTCL was 45 years, with a

predominance of men with the disease. The etiology of NKTCL was

significantly associated with EBV infection. Moreover, a

preliminary assessment revealed that, except for a minority of 5

patients, all patients exhibited positive serum EBV DNA levels.

Notably, the number of cases classified as early-stage exceeded

those classified as late-stage.

Retrospective comparative studies have reported that

asparaginase-based or pegaspargase-based regimens are associated

with superior efficacy compared with conventional

anthracycline-based regimens. In a retrospective study by Wang

et al (17), the efficacy of

chemotherapy regimen GELOX (gemcitabine, l-asparaginase and

oxaliplatin) was compared with those of EPOCH (etoposide,

vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and prednisone) and CHOP

(cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) in the

treatment of NKTCL. The results demonstrated that the 3-year OS and

PFS rates in the GELOX group were significantly superior to those

in the EPOCH or CHOP groups (OS, 87.0 vs. 54.0 vs. 54.0%,

respectively; P<0.05; PFS, 72.0 vs. 50.0 vs. 43.0%,

respectively; P<0.05). However, no significant differences in

PFS (P=0.421) and OS (P=0.765) were observed between the EPOCH and

CHOP groups, indicating the effectiveness of asparaginase-based

chemotherapy regimens. The present study also demonstrated that

asparaginase-based chemotherapy exhibited promising efficacy.

Several studies have demonstrated the value of

combined RT and chemotherapy rather than chemotherapy alone in

early-stage patients. The study by Cao et al (18) reported that sequential

RT-chemotherapy combination therapy or concomitant chemo-RT (CCRT)

produced a greater response than CHOP chemotherapy alone, with a CR

of ~70% (RT-chemotherapy) and 77% (CCRT) compared with 60% (CHOP),

and a 5-year OS rate of 42% (RT-chemotherapy) and 71% (CCRT)

compared with 35% (CHOP), respectively. Huang et al

(19) reported that in 44 patients

treated with gemcitabine, cisplatin and dexamethasone, the ORR was

~95% after intensity-adjusted RT (50 Gy for primary tumor and

additional 3–6 Gy for residual tumor area), with ~89% of patients

achieving a CR, and the 3-year OS and PFS rates were 85 and 77%,

respectively. Zhu et al (9)

performed a study involving 30 patients who underwent concurrent

chemo-RT (RT at 56 Gy/27F and chemotherapy using 25

mg/m2 cisplatin), followed by 3 cycles of DDGP

chemotherapy (dexamethasone, cisplatin, gemcitabine and

pegaspargase). The ORR was 93.3% (28/30), with all 28 patients

achieving a CR at the end of treatment. The findings of the present

study for early-stage patients are consistent with the results

reported in the aforementioned study.

Numerous studies have also indicated that

chemotherapy containing pegaspargase is superior to CHOP

chemotherapy in terms of efficacy and survival rates. In a study by

Bi et al (20), compared

with the regimen without pegaspargase, the P-Gemox/GELOX regimen

was associated with a significantly higher ORR in early-stage

patients (92.9 vs. 51.6%; P=0.009) and demonstrated significantly

improved 5-year OS rates (78.6 vs. 23.9%; P=0.010). Dong et

al (21) reported that,

compared with RT alone, the combination of L-asparaginase,

cisplatin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone with RT

showed no significant difference in CR rates (90.9 vs. 77.8%;

P=0.124). Nevertheless, the group receiving chemotherapy combined

with RT exhibited higher 5-year PFS and OS rates compared with the

RT-alone group (89.2 vs. 49.6%, P=0.024; and 82.9% vs. 48%,

P=0.039; respectively). Huang et al (19) reported that the ORRs for the

combination of L-asparaginase, vincristine and dexamethasone (LOP)

or CHOP with RT were 89.6 and 65.6%, respectively (P=0.009), with

CR rates of 68.8 vs. 50%, respectively. Furthermore, the 3-year OS

and PFS rates significantly increased with LOP treatment (87.5 vs.

62.5%, P=0.006; and 79.2 vs. 50%, P=0.007; respectively),

indicating the superiority of asparaginase-based chemotherapy.

The dosage of RT for NKTCL is controversial, as

increasing the radiation dose may enhance efficacy, but it also

increases the risk of radiation-related complications. A literature

review revealed variability across different clinical centers, with

doses ranging from 40–65 Gy (22,23).

In the study by Wang et al (24), a planned prescription dose of 50 Gy

was administered, with an additional 5–10 Gy of radiation dose for

residual primary disease, resulting in actual doses ranging from

49.6–64 Gy, with a mean dose of 55.5 Gy. Jiang et al

(25) utilized a dose of 56 Gy,

achieving a reasonable ORR (88.5%) whilst maintaining tolerable

radiation toxicity. In the study by Oh et al (26), which involved 62 patients diagnosed

with stage I/II NKTCL, a median dose of 40 Gy of radiation therapy

was administered, resulting in a total response rate of 97% and a

CR rate of 90%. Among this cohort, 58 patients continued with

consolidation chemotherapy, achieving 3-year OS and PFS rates of

83.1 and 77.1%, respectively. The study by Niu et al

(27) involved 60 patients with

stage I/II nasal-type extranodal NKTCL. After induction

chemotherapy with pegaspargase, the patients received radiation

therapy with a dose of 54.6 Gy to the tumor and positive lymph

nodes, 50.7 Gy to the high-risk clinical target volume (CTV) and

45.5 Gy to the low-risk CTV, delivered in 26 fractions. The median

follow-up time was 95.8 months, and the 5-year locoregional

recurrence-free survival, PFS and OS rates were 83.3, 81.7 and

88.3%, respectively. In the present study, combined

chemoradiotherapy with a dose of 54 Gy demonstrated favorable

outcomes, with an ORR of 98.2%, a 4-year PFS rate of 82.5% (95% CI,

75.1–89.9%) and an OS rate of 92.2% (95% CI, 86.9–97.5%) for

early-stage patients. For advanced-stage patients treated with

pegaspargase-based chemotherapy, the 4-year PFS rate was 62.3% (95%

CI, 47.4–77.2%) and the OS rate was 63.5% (95% CI, 48.2–78.8%).

Both early and advanced-stage patients treated with

pegaspargase-based chemotherapy demonstrated high response rates

and long-term survival, consistent with the present study

findings.

The EBV load is an important consideration in NKTCL.

Numerous studies have reported an association between EBV viral

load and prognosis. A meta-analysis performed by Liu et al

(28) indicated that high EBV viral

load before and after treatment is associated with decreased

survival rates. High levels of baseline EBV DNA were significantly

associated with a poor OS, with an HR of 3.45 (95% CI, 1.63–7.31;

P=0.001), and a poor PFS, with an HR of 2.29 (95% CI, 1.50–3.51;

P=0.0001). Similarly, patients with high EBV DNA levels

post-treatment had poor PFS, with an HR of 2.36 (95% CI, 1.40–3.98;

P=0.001). These findings have been corroborated by subsequent

studies (29,30). Wang et al (31) also demonstrated that pre- and

post-treatment EBV DNA positivity were associated with worse OS and

PFS. Moreover, Suzuki et al (32) stratified patients into three

prognostic groups based on post-treatment plasma EBV viral load,

namely, negative, <100 copies/µg and >100 copies/µg, with

significantly decreased survival rates observed in the latter two

groups (P=0.001). The study by Zhong et al (33) also reported that the presence of EBV

DNA positivity during treatment is an independent predictor of

worse PFS and OS. EBV DNA positivity is associated with

upregulation of chromatin remodeling changes, immune

evasion-related genes and a reduction in infiltrating monocytes/M1

macrophages (34). The present

study also demonstrated that EBV load is an essential factor

influencing prognosis. Currently, due to the high sensitivity of

quantitative-PCR and its routine applicability in several medical

facilities, assessing EBV viral load in plasma samples using

quantitative-PCR is crucial throughout the diagnostic, treatment

and long-term follow-up phases (35). An increase in viral load levels may

indicate a recurrence of lymphoma, underscoring the importance of

evaluating EBV during follow-up (36).

The present study has several limitations related to

its retrospective, single-center design. Reliance on incomplete or

inconsistent medical records may introduce selection and

information bias, potentially obscuring true treatment effects and

compromising outcome assessment. Patient preference in choosing

chemotherapy regimens was not controlled, which may confound

survival outcomes. The single-institution setting may reflect local

practices, limiting generalizability. Additionally, variable

follow-up durations may affect prognostic analyses, as shorter

follow-up increases censoring, while longer follow-up may

overrepresent favorable outcomes. These limitations highlight the

need for future prospective, multi-center studies with standardized

protocols and larger, more diverse populations to validate and

strengthen the findings.

In summary, NKTCL predominantly affects young men

and is often associated with B symptoms. Staging is a crucial

prognostic factor for both PFS and OS. Frontline therapy with

pegaspargase-based chemotherapy, either alone or in combination

with concurrent RT, has demonstrated promising efficacy. Future

efforts should focus on optimizing treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LiZ conceived the study. Data was collected,

organized, validated, and managed to ensure data quality and

consistency for statistical analysis by QL, XL, FZ and TL. Data

collection was performed by PL, GA, LuZ, QL and XL. Data analysis

was performed by PL, GA, LuZ, FZ, TL and LiZ. QL and XL were also

involved in the statistical analysis. PL and GA wrote the original

draft. LiZ reviewed and edited the manuscript. TL and LiZ confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors contributed to

the article and approved the submitted version.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved

by the Ethical Review Committee of the Union Hospital, Tongji

Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

(Wuhan, China; approval no. 20240986). The requirement for patient

approval or written informed consent to participate was waived due

to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wei YC, Qi F, Zheng BM, Zhang CG, Xie Y,

Chen B, Liu WX, Liu WP, Fang H, Qi SN, et al: Intensive therapy can

improve long-term survival in newly diagnosed, advanced-stage

extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma: A multi-institutional, real-world

study. Int J Cancer. 153:1643–1657. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen JJ, Tokumori FC, Del Guzzo C, Kim J

and Ruan J: Update on T-cell lymphoma epidemiology. Curr Hematol

Malig Rep. 19:93–103. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF,

Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA; Alliance, Australasian

Leukaemia; Lymphoma Group and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ;

et al: Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and

response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: The Lugano

classification. J Clin Oncol. 32:3059–3068. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yan Z, Yao S, Wang Z, Zhou W, Yao Z and

Liu Y: Treatment of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma: From past to

future. Front Immunol. 14:10886852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang C and Wang L: Resistance mechanisms

and potential therapeutic strategies in relapsed or refractory

natural killer/T cell lymphoma. Chin Med J (Engl). 137:2308–2324.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Deng XW, Wu JX, Wu T, Zhu SY, Shi M, Su H,

Wang Y, He X, Xu LM, Yuan ZY, et al: Radiotherapy is essential

after complete response to asparaginase-containing chemotherapy in

early-stage extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma: A multicenter

study from the China Lymphoma Collaborative Group (CLCG). Radiother

Oncol. 129:3–9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yamaguchi M, Suzuki R, Miyazaki K, Amaki

J, Takizawa J, Sekiguchi N, Kinoshita S, Tomita N, Wada H,

Kobayashi Y, et al: Improved prognosis of extranodal NK/T cell

lymphoma, nasal type of nasal origin but not extranasal origin. Ann

Hematol. 98:1647–1655. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Feng D, Bai S, Chen G, Fu B, Song C, Tang

H, Wang L and Wang H: Comparison of pegaspargase with concurrent

radiation vs. P-GEMOX with sequential radiation in early-stage

NK/T-cell lymphoma. Oncol Res. 33:965–974. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhu F, Liu T, Pan H, Xiao Y, Li Q, Liu X,

Chen W, Wu G and Zhang L: Long-term outcomes of upfront concurrent

chemoradiotherapy followed by P-GDP regimen in newly diagnosed

early stage extranodal nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: A prospective

single-center phase II study. Medicine (Baltimore). 99:e217052020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Horwitz SM, Ansell S, Ai WZ, Barnes J,

Barta SK, Clemens MW, Dogan A, Goodman AM, Goyal G, Guitart J, et

al: NCCN guidelines insights: T-cell lymphomas, version 1.2021. J

Natl Compr Canc Netw. 18:1460–1467. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yang H, Xun Y, Ke C, Tateishi K and You H:

Extranodal lymphoma: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Mol

Biomed. 4:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang Y, Zhang YJ, Zhu Y, Cao JZ, Yuan ZY,

Xu LM, Wu JX, Wang W, Wu T, Lu B, et al: Prognostic nomogram for

overall survival in previously untreated patients with extranodal

NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type: A multicenter study. Leukemia.

29:1571–1577. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lin HN, Liu CY, Pai JT, Chang FP, Yang CF,

Yu YB, Hsiao LT, Chiou TJ, Liu JH, Gau JP, et al: How to predict

the outcome in mature T and NK cell lymphoma by currently used

prognostic models? Blood Cancer J. 2:e932012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lim JQ, Huang D, Chan JY, Laurensia Y,

Wong EKY, Cheah DMZ, Chia BKH, Chuang WY, Kuo MC, Su YJ, et al: A

genomic-augmented multivariate prognostic model for the survival of

natural-killer/T-cell lymphoma patients from an international

cohort. Am J Hematol. 97:1159–1169. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I,

Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, Borges AM, Boyer D,

Calaminici M, et al: The 5th edition of the World Health

Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: Lymphoid

neoplasms. Leukemia. 36:1720–1748. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yang F, Markovic SN, Molina JR,

Halfdanarson TR, Pagliaro LC, Chintakuntlawar AV, Li R, Wei J, Wang

L, Liu B, et al: Association of sex, age, and eastern cooperative

oncology group performance status with survival benefit of cancer

immunotherapy in randomized clinical trials: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 3:e20125342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang L, Wang WD, Xia ZJ, Zhang YJ, Xiang J

and Lu Y: Combination of gemcitabine, L-asparaginase, and

oxaliplatin (GELOX) is superior to EPOCH or CHOP in the treatment

of patients with stage IE/IIE extranodal natural killer/T cell

lymphoma: A retrospective study in a cohort of 227 patients with

long-term follow-up. Med Oncol. 31:8602014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cao J, Lan S, Shen L, Si H, Zhang N, Li H

and Guo R: A comparison of treatment modalities for nasal

extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma in early stages: The

efficacy of CHOP regimen based concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Oncotarget. 8:20362–20370. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang Y, Yang J, Liu P, Zhou S, Gui L, He

X, Qin Y, Zhang C, Yang S, Xing P, et al: Intensity-modulated

radiation therapy followed by GDP chemotherapy for newly diagnosed

stage I/II extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma, nasal type.

Ann Hematol. 96:1477–1483. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bi XW, Xia Y, Zhang WW, Sun P, Liu PP,

Wang Y, Huang JJ, Jiang WQ and Li ZM: Radiotherapy and PGEMOX/GELOX

regimen improved prognosis in elderly patients with early-stage

extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 94:1525–1533. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Dong LH, Zhang LJ, Wang WJ, Lei W, Sun X,

Du JW, Gao X, Li GP and Li YF: Sequential DICE combined with

l-asparaginase chemotherapy followed by involved field radiation in

newly diagnosed, stage IE to IIE, nasal and extranodal NK/T-cell

lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 57:1600–1606. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim SJ, Kim K, Kim BS, Kim CY, Suh C, Huh

J, Lee SW, Kim JS, Cho J, Lee GW, et al: Phase II trial of

concurrent radiation and weekly cisplatin followed by VIPD

chemotherapy in newly diagnosed, stage IE to IIE, nasal, extranodal

NK/T-Cell Lymphoma: Consortium for improving survival of lymphoma

study. J Clin Oncol. 27:6027–6032. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li YX, Yao B, Jin J, Wang WH, Liu YP, Song

YW, Wang SL, Liu XF, Zhou LQ, He XH, et al: Radiotherapy as primary

treatment for stage IE and IIE nasal natural killer/T-cell

lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 24:181–189. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang H, Li YX, Wang WH, Jin J, Dai JR,

Wang SL, Liu YP, Song YW, Wang ZY, Liu QF, et al: Mild toxicity and

favorable prognosis of high-dose and extended involved-field

intensity-modulated radiotherapy for patients with early-stage

nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

82:1115–1121. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang M, Zhang L, Xie L, Zhang H, Jiang Y,

Liu WP, Zhang WY, Tian R, Deng YT, Zhao S and Zou LQ: A phase II

prospective study of the ‘Sandwich’ protocol, L-asparaginase,

cisplatin, dexamethasone and etoposide chemotherapy combined with

concurrent radiation and cisplatin, in newly diagnosed, I/II stage,

nasal type, extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget.

8:50155–50163. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Oh D, Ahn YC, Kim SJ, Kim WS and Ko YH:

Concurrent chemoradiation therapy followed by consolidation

chemotherapy for localized extranodal natural killer/t-cell

lymphoma, nasal type. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 93:677–683.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Niu S, Li Y, Shao H, Hu J, Wang J, Wang H

and Zhang Y: Phase 2 clinical trial of simultaneous boost intensity

modulated radiation therapy with 3 dose gradients in patients with

stage I–II nasal type natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: Long-term

outcomes of survival and quality of life. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 118:770–780. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu ZL, Bi XW, Liu PP, Lei DX, Jiang WQ

and Xia Y: The clinical utility of circulating epstein-barr virus

DNA concentrations in NK/T-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Dis

Markers. 2018:19610582018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kimura H and Kwong YL: EBV viral loads in

diagnosis, monitoring, and response assessment. Front Oncol.

9:622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Porte J, Hennequin C, Krizch D, Vercellino

L, Guillerm S, Thieblemont C and Quéro L: Extranodal nasal-type

NK/T lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy: Case

series from a European tertiary referral center and review of the

literature. Strahlenther Onkol. 200:434–443. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang X, Hu J, Dong M, Ding M, Zhu L, Wu J,

Sun Z, Li X, Zhang L, Li L, et al: DDGP vs. SMILE in

relapsed/refractory extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma,

nasal type: A retrospective study of 54 patients. Clin Transl Sci.

14:405–411. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Suzuki R, Yamaguchi M, Izutsu K, Yamamoto

G, Takada K, Harabuchi Y, Isobe Y, Gomyo H, Koike T, Okamoto M, et

al: Prospective measurement of Epstein-Barr virus-DNA in plasma and

peripheral blood mononuclear cells of extranodal NK/T-cell

lymphoma, nasal type. Blood. 118:6018–6022. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhong H, Cheng S, Xiong J, Chen J, Mu R,

Yang H, Yi H, Song Q, Zhang H, Hu Y, et al: Dynamic change in

Epstein-Barr virus DNA predicts prognosis in early stage natural

killer/T-cell lymphoma with pegaspargase-based treatment: long-term

follow-up and biomarker analysis from the NHL-004 multicenter

randomized study. Haematologica. 2025.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Damania B, Kenney SC and Raab-Traub N:

Epstein-Barr virus: Biology and clinical disease. Cell.

185:3652–3670. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Stelzl E, Kessler HH, Parulekar AD, Bier

C, Nörz D, Schneider T, Kumar S, Simon CO and Lütgehetmann M:

Comparison of four commercial EBV DNA quantitative tests to a new

test at an early stage of development. J Clin Virol.

161:1054002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shannon-Lowe C, Rickinson AB and Bell AI:

Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B

Biol Sci. 372:201602712017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|