Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent

malignancies worldwide, accounting for a significant proportion of

cancer-related morbidity and mortality. According to global cancer

statistics, CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and

second leading cause of cancer-related deaths (1). Despite advancements in surgical

techniques and early detection methods, many patients present with

locally advanced or metastatic disease at diagnosis, necessitating

systemic chemotherapy to improve outcomes.

For metastatic CRC (mCRC), systemic chemotherapy has

been a cornerstone of treatment and is often combined with targeted

therapies. The introduction of monoclonal antibodies, including

bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

agent, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors

(cetuximab and panitumumab), has significantly improved survival in

specific patient subgroups. The combination of fluorouracil,

leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and/or irinotecan (FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, or

FOLFOXIRI) with targeted agents has effected a median overall

survival (OS) >30 months in selected patients (2,3).

However, despite these advancements in CRC

treatment, resistance and progression remain major challenges for

later-line therapies. TAS-102, an effective treatment for

previously treated mCRC, exerts its cytotoxic effects through

trifluridine (FTD), which gets incorporated into DNA, thereby

disrupting its replication (4).

Additionally, preclinical CRC models have demonstrated that adding

bevacizumab enhances phosphorylated FTD levels, supporting the

rationale for this combination in mCRC (5).

In 2023, the results of the SUNLIGHT trial, a phase

III study, showed a significantly better OS for TAS-102 plus

bevacizumab compared with TAS-102 alone [10.8 vs. 7.5 months;

hazard ratio (HR)=0.61, P<0.001] (6).

Based on the results of the phase 1/2 C-TASK FORCE

trial (7) and after undergoing

Institutional Review Board approval, we have been actively

introducing and administering TAS-102 plus bevacizumab therapy as a

backward treatment since October 2016. The results of the SUNLIGHT

study were used as the basis for the present retrospective analysis

of the results and validity of TAS-102 plus bevacizumab

therapy.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective observational study was approved

by the Ethics Committee of Gifu University Graduate School of

Medicine (Institutional Review Board approval no. 2024-144) and was

conducted in accordance with the national guidelines for human

research. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the

Ethics Committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

This study analyzed data from electronic medical

records at our hospital. The study included patients with mCRC

resistant to at least one of the following: Fluoropyrimidine,

irinotecan, oxaliplatin, anti-VEGF therapy, and anti-EGFR therapy

(for KRAS wild-type tumors). These patients were administered

TAS-102 at our outpatient chemotherapy clinic between October 2016

and December 2023. The median age of the patients was 67 years

(range, 24–86 years).

KRAS/NRAS mutation status was analyzed at our

institution using a PCR-SSO (sequence-specific oligonucleotide)

method routinely performed in the clinical diagnostic laboratory,

covering exon 2 (codons 12, 13), exon 3 (codons 59, 61), and exon 4

(codons 117, 146). Primer sequences are proprietary and not

disclosed, but the assay is standardized and validated in our

institutional diagnostic setting.

Chemotherapy

Patients were administered TAS-102 (35

mg/m2 body surface area) orally twice daily on days 1–5

and 8–12 of a 28-day cycle, in combination with bevacizumab (5

mg/kg, infused intravenously over 30 min every 2 weeks).

For severe adverse events (grade 3–4 neutropenia), a

10-mg/day dose reduction was applied in subsequent cycles without

re-escalation. Treatment was suspended in cases of grade 3–4

neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, febrile neutropenia, elevated

bilirubin (>3.0 mg/dl), aspartate aminotransferase/alanine

aminotransferase level >150 U/l, creatinine level >1.5 mg/dl,

or grade 3–4 non-hematologic toxicities. After resolution,

treatment was resumed at a lower TAS-102 dose of 10 mg/day.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP

Student Edition version 18 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The

significance level (α) was set at 0.05 (two-sided). Categorical

variables were compared using the χ2 test (for

frequencies), and continuous variables, such as age, were compared

using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Survival curves were analyzed

using both the log-rank test and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test;

both were included because the log-rank test is more sensitive to

proportional hazards, whereas the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test

places more weight on early differences. Median survival times with

95% confidence intervals were calculated, and hazard ratios were

estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. Both

univariable and multivariable analyses were performed.

Results

Patient backgrounds

A total of 101 patients with CRC (65 men and 36

women; median age, 67 years) were administered TAS-102 plus

bevacizumab during the study period (Table I). Approximately 60% of the patients

had a primary rectal tumor, and 90% had ≤2 metastatic organs. The

metastatic organs included 48 livers, 47 lungs, 25 lymph nodes, 11

local, and 6 others. Approximately 60% and <20% of the patients

were administered the study treatment as third- and second-line

therapies, respectively. Wild-type RAS was present in approximately

half of the patients, and mutant BRAF and low microsatellite

instability (MSI) were observed in two patients each. The

chemotherapy history included fluoropyrimidine (101 patients,

100%), oxaliplatin (95 patients, 94.1%), irinotecan (82 patients,

81.2%), anti-VEGF antibody (92 patients, 91.1%), and anti-EGFR

antibody (41 patients, accounting for 87.2% of the RAS wild-type

subgroup). Subsequent therapy was administered in 66 patients

(65.3%), and regorafenib was used in 54 patients, accounting for

81.8% of those who received subsequent therapy. The median duration

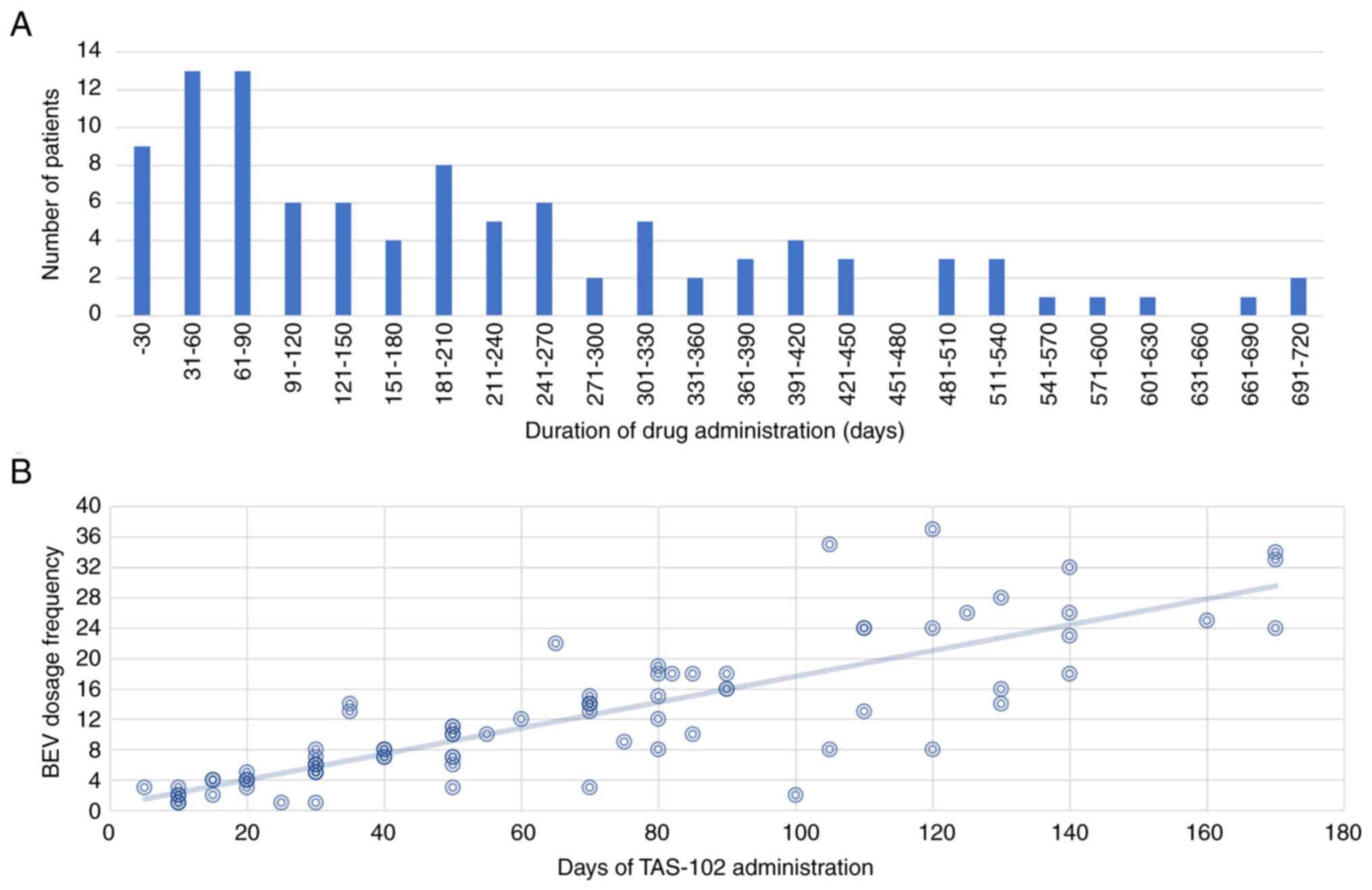

of TAS-102 plus bevacizumab treatment was 184 days (Fig. 1A). The longest treatment duration

was approximately 2 years, but most cases lasted for 9 months.

Although most patients were administered the same regimen, those

who skipped FTD/tipiracil (TPI) and received more bevacizumab and

those who skipped bevacizumab and received more FTD/TPI were

approximately the same (Fig. 1B).

The most frequent grade ≥3 adverse event was neutropenia [25

(24.8%) grade 3 and 18 (17.8%) grade 4], followed by leukopenia [25

(24.8%)], anemia [16 (15.8%)], and thrombocytopenia [6 (5.9%)].

Among non-hematological toxicities, grade 3 hypertension [12

(11.9%)], proteinuria [8 (7.9%)], and diarrhea [6 (5.9%)] were

observed. Notably, no grade 5 treatment-related adverse events

occurred (Table II).

| Table I.Subject and patient background. |

Table I.

Subject and patient background.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Age,

yearsa | 67 (24–86) |

| Sex |

|

| Male | 65 (64.4%) |

|

Female | 36 (35.6%) |

| Primary

diagnosis |

|

|

Right-sided colon | 16 (15.8%) |

|

Left-sided colon | 23 (22.8%) |

|

Rectum | 62 (61.4%) |

| Time from diagnosis

of first metastasis to treatment |

|

| <18

months | 38 (37.6%) |

| ≥18

months | 63 (62.4%) |

| Number of metastatic

sites |

|

| 1 | 55 (54.5%) |

| 2 | 37 (36.6%) |

| 3 | 7 (6.9%) |

| 4 | 2 (2.0%) |

| RAS status |

|

| Wild

type | 47 (46.5%) |

|

Mutation | 52 (51.5%) |

|

Unknown | 2 (2.0%) |

| BRAF status |

|

| Wild

type | 66 (65.3%) |

|

Mutation | 2 (2.0%) |

|

Unknown | 33 (32.7%) |

| MMR and MSI

status |

|

| MMR

deficient and high MSI | 2 (2.0%) |

| MMR

proficient and stable or low MSI | 72 (71.3%) |

|

Unknown | 27 (26.7%) |

| Number of previous

treatment regimens |

|

| 1 | 17 (16.8%) |

| 2 | 63 (62.4%) |

| ≥3 | 21 (20.8%) |

| Subsequent

therapy |

|

| Yes | 66 (65.3%) |

|

Regorafenib | 54

(81.8%)b |

| No | 35 (34.7%) |

| Drugs used in the

previous treatment regimen |

|

|

Fluoropyrimidine | 101 (100.0%) |

|

Irinotecan | 82 (81.2%) |

|

Oxaliplatin | 95 (94.1%) |

|

Anti-VEGF monoclonal

antibody | 92 (91.1%) |

|

Anti-EGFR monoclonal

antibody | 41/47

(87.2%)c |

| Table II.Treatment-related adverse events of

grade ≥3. |

Table II.

Treatment-related adverse events of

grade ≥3.

| Adverse event | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|

| Neutropenia | 25 (24.8) | 18 (17.8) | 43 (42.6) |

| Leukopenia | 25 (24.8) | 0 | 25 (24.8) |

| Anemia | 16 (15.8) | 0 | 16 (15.8) |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 6 (5.9) | 0 | 6 (5.9) |

| Hypertension | 12 (11.9) | 0 | 12 (11.9) |

| Proteinuria | 8 (7.9) | 0 | 8 (7.9) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (5.9) | 0 | 6 (5.9) |

OS and progression-free survival

(PFS)

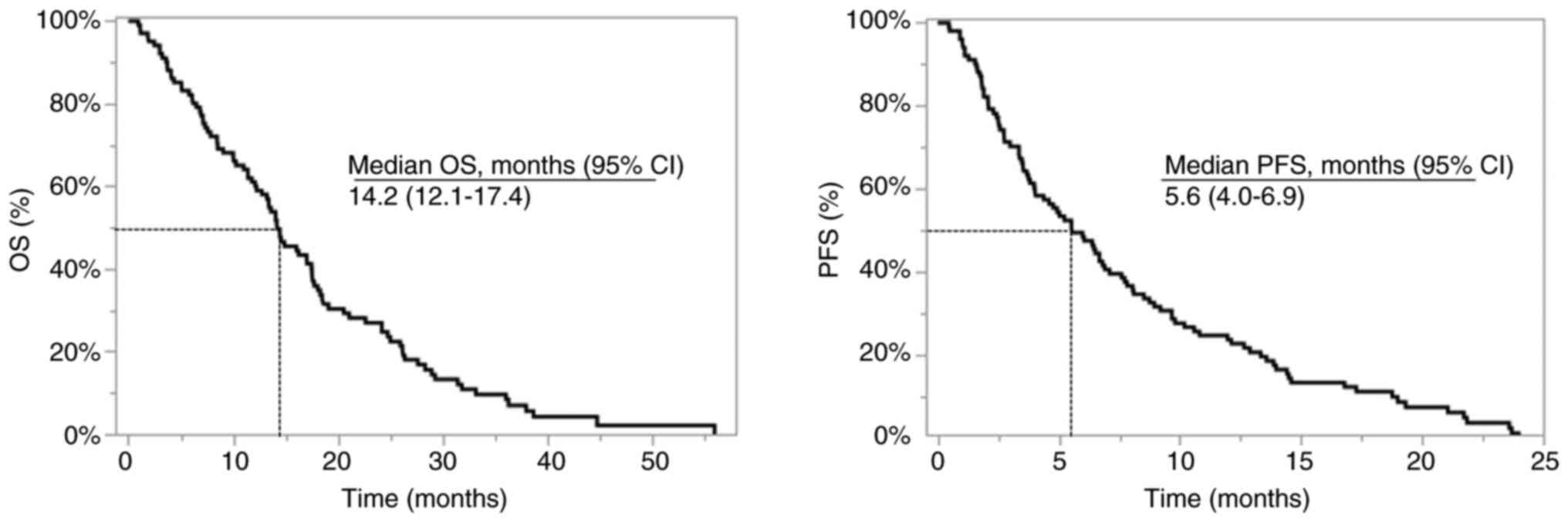

Overall, the median PFS and OS were 5.6 and 14.2

months, respectively (Fig. 2).

Regarding the primary tumor site, the median PFS was 4.0 months for

colon cancer and 6.9 months for rectal cancer, and the median OS

values were 11.0 and 17.6 months, respectively. Baseline

characteristics of patients with colon and rectal cancers are

summarized in Table III.

Concerning survival curve comparison, the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon

test showed a statistically significant difference in favor of

rectal cancer (PFS: P=0.035; OS: P=0.025), whereas the log-rank

test did not show a statistically significant difference (PFS:

P=0.54; OS: P=0.65). In the multivariable Cox regression analysis

adjusting for RAS mutation, primary site, anti-VEGF antibody

administration, number of treatment lines, and liver metastasis,

primary site was not identified as an independent prognostic factor

for either PFS or OS (Table

IV).

| Table III.Comparison of patient backgrounds in

the colon and rectum. |

Table III.

Comparison of patient backgrounds in

the colon and rectum.

| Characteristic | Colon (n=39) | Rectum (n=62) | P-value |

|---|

| Age,

yearsa | 64.7±13.8 | 65.6±10.7 | 0.7340 |

| Male sex | 22 (56.4%) | 43 (69.4%) | 0.1860 |

| RAS mutation | 20 (51.3%) | 33 (54.1%) | 0.8490 |

| BRAF mutation | 2 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.1463b |

| MSI high | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (2.2%) |

>0.999b |

| Number of previous

treatment regimens |

|

| 0.3718 |

| 1 | 4 | 13 |

|

| 2 | 26 | 37 |

|

| ≥3 | 9 | 12 |

|

| Subsequent

therapy |

|

| 0.2858c |

|

Yes | 23 | 43 |

|

|

Regorafenib | 19 | 35 |

|

| No | 16 | 19 |

|

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

| 0.1662 |

| 1 | 21 | 34 |

|

| 2 | 12 | 25 |

|

| ≥3 | 6 | 3 |

|

| Sites of

metastasisd |

|

| 0.0103b |

|

Liver | 28 | 20 |

|

|

Lung | 13 | 34 |

|

| Lymph

node | 7 | 18 |

|

|

Local | 2 | 9 |

|

|

Bone | 0 | 1 |

|

|

Others | 2 | 3 |

|

| Table IV.Multivariable Cox proportional

hazards analysis. |

Table IV.

Multivariable Cox proportional

hazards analysis.

|

| OS | PFS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Ras status (wild

type vs. mutation) | 0.62 | 0.34–1.65 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.31–1.29 | 0.37 |

| Primary site

(rectum vs. colon) | 1.20 | 0.65–1.78 | 0.65 | 1.18 | 0.73–1.82 | 0.54 |

| Anti-VEGF therapy

(yes vs. no) | 1.29 | 0.61–2.98 | 0.51 | 1.46 | 0.67–3.54 | 0.35 |

| Liver metastasis

(yes vs. no) | 1.08 | 0.71–2.08 | 0.75 | 1.36 | 0.87–2.12 | 0.18 |

| Treatment line

number | 1.02 | 0.64–1.47 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.67–1.37 | 0.82 |

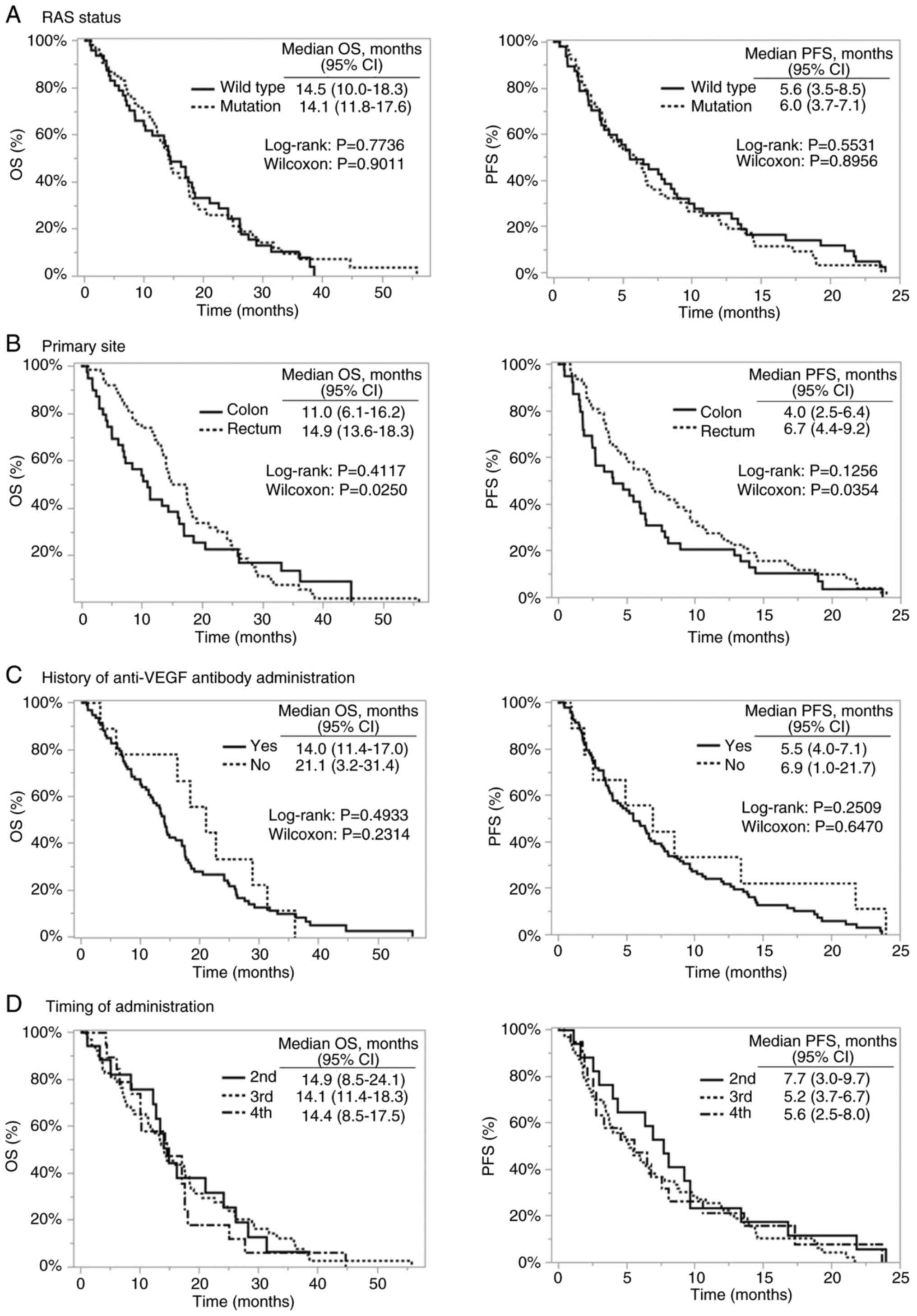

Comparisons based on the presence or absence of RAS

mutations, history of anti-VEGF antibody administration, and

treatment line showed numerically longer OS in patients without

prior anti-VEGF antibody administration and a trend toward longer

PFS in the second-line treatment group; however, none of these

differences were statistically significant in

Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon, log-rank, or Cox analyses (Fig. 3; Table

IV). In addition, comparisons according to the presence or

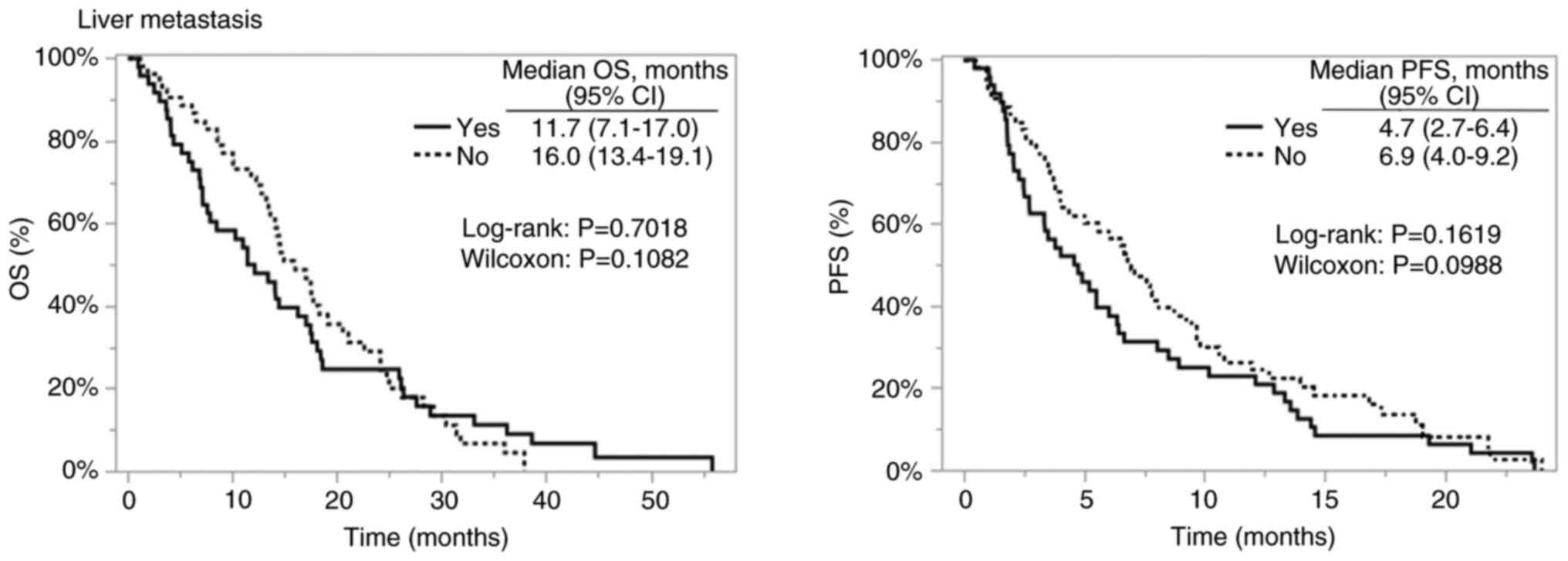

absence of liver metastasis are shown in Fig. 4, and the corresponding patient

characteristics and outcomes are summarized in Table V.

| Table V.Comparison with and without liver

metastasis. |

Table V.

Comparison with and without liver

metastasis.

| Characteristic | With liver

metastasis (n=48) | Without liver

metastasis (n=53) | P-value |

|---|

| Age,

yearsa | 64.0±13.3 | 66.5±10.6 | 0.3097 |

| Male sex | 34 (70.8%) | 31 (58.5%) | 0.1959 |

| Primary

diagnosis |

|

| 0.0001 |

|

Colon | 28 (58.3%) | 11 (20.8%) |

|

|

Rectum | 20 (41.7%) | 42 (79.2%) |

|

| RAS mutation | 24 (50.0%) | 30 (56.6%) | 0.5063 |

| BRAF mutation | 2 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.2234b |

| MSI high | 2 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.2234b |

| Number of previous

treatment regimens |

|

| 0.0211 |

| 1 | 3 | 14 |

|

| 2 | 35 | 28 |

|

| ≥3 | 10 | 11 |

|

| Subsequent

therapy |

|

| 0.2701c |

|

Yes | 34 | 32 |

|

|

Regorafenib | 29 | 25 |

|

| No | 14 | 21 |

|

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

| 0.1534b |

| 1 | 23 | 32 |

|

| 2 | 14 | 19 |

|

| ≥3 | 7 | 2 |

|

Discussion

Combination therapy with TAS-102 and bevacizumab has

demonstrated improved survival outcomes compared to TAS-102

monotherapy in patients with mCRC. Across multiple studies, the

median PFS for this combination ranged from 4.29 to 5.6 months,

whereas the median OS spanned 9.3 to 14.4 months (4,5,8–11)

(Table VI).

| Table VI.Treatment outcomes of TAS-102 plus

bevacizumab therapy. |

Table VI.

Treatment outcomes of TAS-102 plus

bevacizumab therapy.

| First author,

year | Median OS, months

(95% CI) | Median PFS, months

(95% CI) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Satake et

al, 2020 | 10.86 | 4.29 | (5) |

| Chida et al,

2021 | 11.5

(9.9–13.9) | 4.4 (3.7–5.4) | (8) |

| Fujii et al,

2020 | 14.4 | 5.6 (TTF) | (9) |

| Joarder et

al, 2025 | 10.9

(8.9–12.8) | 4.4 (3.1–5.7) | (10) |

| Liu et al,

2021 | 10.41

(8.40–12.89) | 4.35

(3.05–6.20) | (11) |

| Martínez-Lago et

al, 2022 | 9.3 (6.6–12.1) | 4.3 (3.4–5.1) | (4) |

| Present study,

2025 | 14.2

(12.1–17.4) | 5.6 (4.0–6.9) | - |

Although TAS-102 plus bevacizumab therapy has shown

promising results in mCRC, to date, no study has specifically

analyzed or reported outcomes for patients with rectal cancer

separately from those for CRC as a whole. All existing studies have

combined data for CRC (including both colon and rectal cancers)

without a subgroup analysis for rectal cancer. This lack of

differentiation represents a significant gap in current research

and limits the ability to assess potential differences in treatment

efficacy or safety profiles between rectal and colon cancers.

Although both colon and rectal cancers are

classified as CRC, they differ in prognosis, recurrence patterns,

and treatment responses. Several studies have investigated the

survival rates and prognostic factors of these two malignancies,

revealing key differences in their outcomes.

Historically, colon cancer has demonstrated a mildly

better prognosis than rectal cancer, particularly in the early

stages. Population-based studies indicate that five-year survival

rates for colon cancer have improved from 51–57% to 62–66%, whereas

rectal cancer survival has increased from 44–51% to 59–65%

(12–14). These improvements are partly

attributable to advances in systemic therapy for colon cancer and

preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgical techniques for rectal

cancer (14–16). Thus, the survival gap between colon

and rectal cancers has narrowed over time.

Additionally, survival rates differ with disease

recurrence. Colon cancer has a high propensity for liver

metastasis, whereas rectal cancer more frequently metastasizes to

the lungs, and local recurrence remains a major challenge (17–20).

These distinct metastatic patterns may partly explain the survival

differences observed in our cohort. Nevertheless, the effect of

primary tumor site on prognosis in patients with refractory mCRC

should be considered hypothesis-generating, and confirmation

through larger prospective datasets or pooled analyses is

warranted.

In our study, the comparison between rectal and

colon cancers revealed no significant differences in age, sex, RAS

or BRAF mutation status, MSI status, number of previous treatment

regimens, subsequent therapies, or the number of metastatic sites.

However, similar to the results of previous surveys, liver

metastases were less common in patients with rectal cancer than in

those with colon cancer, whereas lung metastases and local

recurrence were more common (Table

III).

Various studies have also reported prognostic

differences based on metastatic and recurrent sites in CRC. For

instance, some studies have suggested that solitary lung metastases

are associated with a better prognosis (21–23);

however, these analyses often included cases in which the

metastases were surgically resected. In our study, likely owing to

the small sample size, no significant prognostic differences were

observed among cases with solitary metastases based on the

metastatic site.

The present study is the first to evaluate the

differences in prognosis after salvage therapy. Contrary to

previous reports, most patients receiving the salvage line did not

have resectable distant metastases. In our analysis, patients with

liver metastases tended to have poorer OS and PFS compared with

those without metastases (Fig. 4).

Comparison of patient characteristics based on liver metastasis

status revealed that colon cancer was significantly more frequent

and the proportion of patients receiving second-line treatment was

significantly higher in patients with liver metastases. Although

the number of metastatic sites in three or more organs was

numerically higher in the liver metastasis group, the difference

was not statistically significant (Table VI). Notably, although the

proportion of patients receiving second-line treatment with a good

treatment response was higher in the liver metastasis group, the OS

and PFS still tended to be poorer in patients with liver

metastasis.

When comparing rectal and colon cancers, survival

curve analysis showed a significant difference in favor of rectal

cancer with the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test but no significant

difference with the log-rank test. Moreover, primary tumor site was

not identified as an independent prognostic factor in the

multivariable Cox regression model. This suggests that patients

with rectal cancer may experience better outcomes during the early

phase of treatment; however, these differences diminish over time

and may be confounded by other clinical factors.

Taken together, these findings suggest that liver

metastasis is associated with a poor prognosis in salvage therapy,

and the lower frequency of liver metastases in rectal cancer may

partially explain the relatively favorable outcomes in this

subgroup. However, these results should be interpreted with

caution. The observed survival advantage in rectal cancer is

hypothesis-generating, and thus confirmation is required via larger

prospective datasets or pooled analyses.

The proportion of elderly patients in the present

study was higher than that reported in the SUNLIGHT study. As a

result, irinotecan was administered less frequently, with a trend

towards the use of the less invasive TAS-102 plus bevacizumab

regimen as second-line therapy. Similarly, the rate of anti-EGFR

antibody administration was low, with a trend towards a higher rate

of bevacizumab combination therapy (Table VII). In addition, the high

proportion of patients with rectal cancer may have resulted in a

relatively good prognosis. Although the patient backgrounds

differed from those in the SUNLIGHT study and other previous

reports, similar results were obtained in the present study,

indicating the efficacy of TAS-102 plus bevacizumab therapy across

different patient populations.

| Table VII.Comparison of patient backgrounds in

the SUNLIGHT trial and this study. |

Table VII.

Comparison of patient backgrounds in

the SUNLIGHT trial and this study.

| Characteristic | SUNLIGHT trial

(n=246) | Our cases

(n=101) |

|---|

| Age,

yearsa | 62 (20–84) | 67 (24–86) |

| Male sex | 122 (49.6%) | 65 (64.4%) |

| Primary

diagnosis |

|

|

|

Colon | 180 (73.2%) | 39 (38.6%) |

|

Rectum | 66 (26.8%) | 62 (61.4%) |

| Number of

metastatic sites |

|

|

| 1 or

2 | 152 (61.8%) | 92 (91.1%) |

| ≥3 | 94 (38.2%) | 9 (8.9%) |

| RAS status |

|

|

| Wild

type | 75 (30.5%) | 47 (46.5%) |

|

Mutation | 171 (69.5%) | 52 (51.5%) |

|

Unknown | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Number of previous

treatment regimens |

|

|

| 1 | 11 (4.5%) | 17 (16.8%) |

| 2 | 229 (93.1%) | 63 (62.4%) |

| ≥3 | 6 (2.4%) | 21 (20.8%) |

| Drugs used in the

previous treatment regimen |

|

|

|

Fluoropyrimidine | 246 (100.0%) | 101(100.0%) |

|

Irinotecan | 246 (100.0%) | 82 (81.2%) |

|

Oxaliplatin | 241 (98.0%) | 95 (94.1%) |

|

Anti-VEGF monoclonal

antibody | 178 (72.4%) | 92 (91.1%) |

|

Anti-EGFR monoclonal

antibodyb | 67/71 (94.4%) | 41/47 (87.2%) |

In conclusion, in the present study, TAS-102

combined with bevacizumab in subsequent treatments showed greater

efficacy against rectal cancer than against colon cancer. This may

be because rectal cancer is associated with fewer liver metastases

than colon cancer. However, these results should be interpreted

with caution.

The limitations of this study include its

retrospective single-center design, potential selection bias,

relatively small sample size, and insufficient statistical power

for subgroup analyses. In particular, the lack of significant

differences in many subgroup comparisons is likely due to the

limited number of patients in each subgroup. Therefore, the

observed survival advantage for rectal cancer should be considered

hypothesis-generating, and further investigations using larger

prospective or pooled datasets are required to validate these

findings.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KMa and NM conceptualized the study, performed data

analysis, wrote the original draft and reviewed and edited the

manuscript. RY, CM, RA, JYT, ME, YH, TH, MF, IY, YS, YT and KMu

contributed to data acquisition, clinical supervision, and

interpretation of the data. KMa and NM confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethics approval and waiver of informed consent were

obtained from the Ethics Committee of Gifu University Graduate

School of Medicine (approval no. 2024-144).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript, and

subsequently, the authors revised and edited the content produced

by the AI tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

EGFR

|

epidermal growth factor receptor

|

|

FTD

|

trifluridine

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

TPI

|

tipiracil

|

|

VEGF

|

vascular endothelial growth factor

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C,

Lupi C, Sensi E, Lonardi S, Mezi S, Tomasello G, Ronzoni M,

Zaniboni A, et al: FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus

bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic

colorectal cancer: Updated overall survival and molecular subgroup

analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol.

16:1306–1315. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shinozaki K, Yamada T, Nasu J, Matsumoto

T, Yuasa Y, Shiraishi T, Nagano H, Moriyama I, Fujiwara T, Miguchi

M, et al: A phase II study of folfoxiri plus bevacizumab as initial

chemotherapy for patients with untreated metastatic colorectal

cancer: TRICC1414 (BeTRI). Int J Clin Oncol. 26:399–408. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Martínez-Lago N, Chucla TC, De Castro BA,

Ponte RV, Rendo CR, Rodriguez MIGR, Diaz SS, Suarez BG, Gomez JC,

Fernandez FB, et al: Efficacy, safety and prognostic factors in

patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with

trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab in a real-world setting.

Sci Rep. 12:146122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Satake H, Kato T, Oba K, Kotaka M, Kagawa

Y, Yasui H, Nakamura M, Watanabe T, Matsumoto T, Kii T, et al:

Phase Ib/II study of biweekly TAS-102 in combination with

bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer

refractory to standard therapies (BiTS Study). Oncologist.

25:e1855–e1863. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Prager GW, Taieb J, Fakih M, Ciardiello F,

Van Cutsem E, Elez E, Cruz FM, Wyrwicz L, Stroyakovskiy D, Papai Z,

et al: Trifluridine-tipiracil and bevacizumab in refractory

metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 388:1657–1667. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kuboki Y, Nishina T, Shinozaki E, Yamazaki

K, Shitara K, Okamoto W, Kajiwara T, Matsumoto T, Tsushima T,

Mochizuki N, et al: TAS-102 plus bevacizumab for patients with

metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies

(C-TASK FORCE): An investigator-initiated, open-label, single-arm,

multicentre, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 18:1172–1181. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chida K, Kotani D, Nakamura Y, Kawazoe A,

Kuboki Y, Kojima T, Taniguchi H, Watanabe J, Endo I and Yoshino T:

Efficacy and safety of trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab and

trifluridine/tipiracil or regorafenib monotherapy for

chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective

study. Ther Adv Med Oncol. April 20–2021.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Fujii H, Matsuhashi N, Kitahora M,

Takahashi T, Hirose C, Iihara H, Yamada Y, Watanabe D, Ishihara T,

Suzuki A and Yoshida K: Bevacizumab in combination with TAS-102

improves clinical outcomes in patients with refractory metastatic

colorectal cancer: A retrospective study. Oncologist. 25:e469–e476.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Joarder R, Patel D, Tiwari A, Choudhary J,

Vana P, Shenoy V, Mer N, Ramaswamy A, Bhargava P and Ostwal V:

TAS-102 plus bevacizumab as an effective and well tolerated regimen

in chemotherapy-refractory advanced colorectal cancers-A single

institution retrospective analysis. South Asian J Cancer. Jan

7–2025.(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

11

|

Liu CJ, Hu T, Shao P, Chu WY, Cao Y and

Zhang F: TAS-102 monotherapy and combination therapy with

bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Res

Pract. 2021:40146012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Brouwer NPM, Bos ACRK, Lemmens VEPP, Tanis

PJ, Hugen N, Nagtegaal ID, de Wilt JHW and Verhoeven RHA: An

overview of 25 years of incidence, treatment and outcome of

colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 143:2758–2766. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lemmens V, van Steenbergen L,

Janssen-Heijnen M, Martijn H, Rutten H and Coebergh JW: Trends in

colorectal cancer in the south of the Netherlands 1975–2007: Rectal

cancer survival levels with colon cancer survival. Acta Oncol.

49:784–796. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Renouf DJ, Woods R, Speers C, Hay J, Phang

PT, Fitzgerald C and Kennecke H: Improvements in 5-year outcomes of

stage II/III rectal cancer relative to colon cancer. Am J Clin

Oncol. 36:558–564. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fernandez-Martos C, Garcia-Albeniz X,

Pericay C, Maurel J, Aparicio J, Montagut C, Safont MJ, Salud A,

Vera R, Massuti B, et al: Chemoradiation, surgery and adjuvant

chemotherapy versus induction chemotherapy followed by

chemoradiation and surgery: Long-term results of the Spanish GCR-3

phase II randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 26:1722–1728. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yaffee P, Osipov A, Tan C, Tuli R and

Hendifar A: Review of systemic therapies for locally advanced and

metastatic rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 6:185–200.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J and

Hemminki K: Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci

Rep. 6:297652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Holch JW, Demmer M, Lamersdorf C, Michl M,

Schulz C, von Einem JC, Modest DP and Heinemann V: Pattern and

dynamics of distant metastases in metastatic colorectal cancer.

Visc Med. 33:70–75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shinto E, Ike H, Ito M, Takahashi K, Ohue

M, Kanemitsu Y, Suto T, Kinugasa T, Watanabe J, Hida JI, et al:

Lateral node metastasis in low rectal cancer as a hallmark to

predict recurrence patterns. Int J Clin Oncol. 29:1896–1907. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kobayashi A, Sugito M, Ito M and Saito N:

Predictors of successful salvage surgery for local pelvic

recurrence of rectosigmoid colon and rectal cancers. Surg Today.

37:853–859. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Khattak MA, Martin HL, Beeke C, Price T,

Carruthers S, Kim S, Padbury R and Karapetis CS: Survival

differences in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and with

single site metastatic disease at initial presentation: Results

from South Australian clinical registry for advanced colorectal

cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 11:247–254. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pu H, Chen Y, Shen R, Zhang Y, Yang D, Liu

L, Dong X and Yang G: Influence of the initial recurrence site on

prognosis after radical surgery for colorectal cancer: A

retrospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 21:1372023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kawaguchi K, Uehara K, Nakayama G, Fukui

T, Fukumoto K, Nakamura S and Yokoi K: Growth rate of

chemotherapy-naïve lung metastasis from colorectal cancer could be

a predictor of early relapse after lung resection. Int J Clin

Oncol. 21:329–334. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|