Endometrial cancer (EC), a malignancy originating

from the uterine endometrium, exhibits a rising global incidence,

with >417,000 new cases and 97,000 deaths reported worldwide in

2022 alone (1). This trend is

largely attributable to the increasing prevalence of risk factors

such as obesity and metabolic syndrome (1–3).

Therapeutically, EC management has been refined by the molecular

classification established by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which

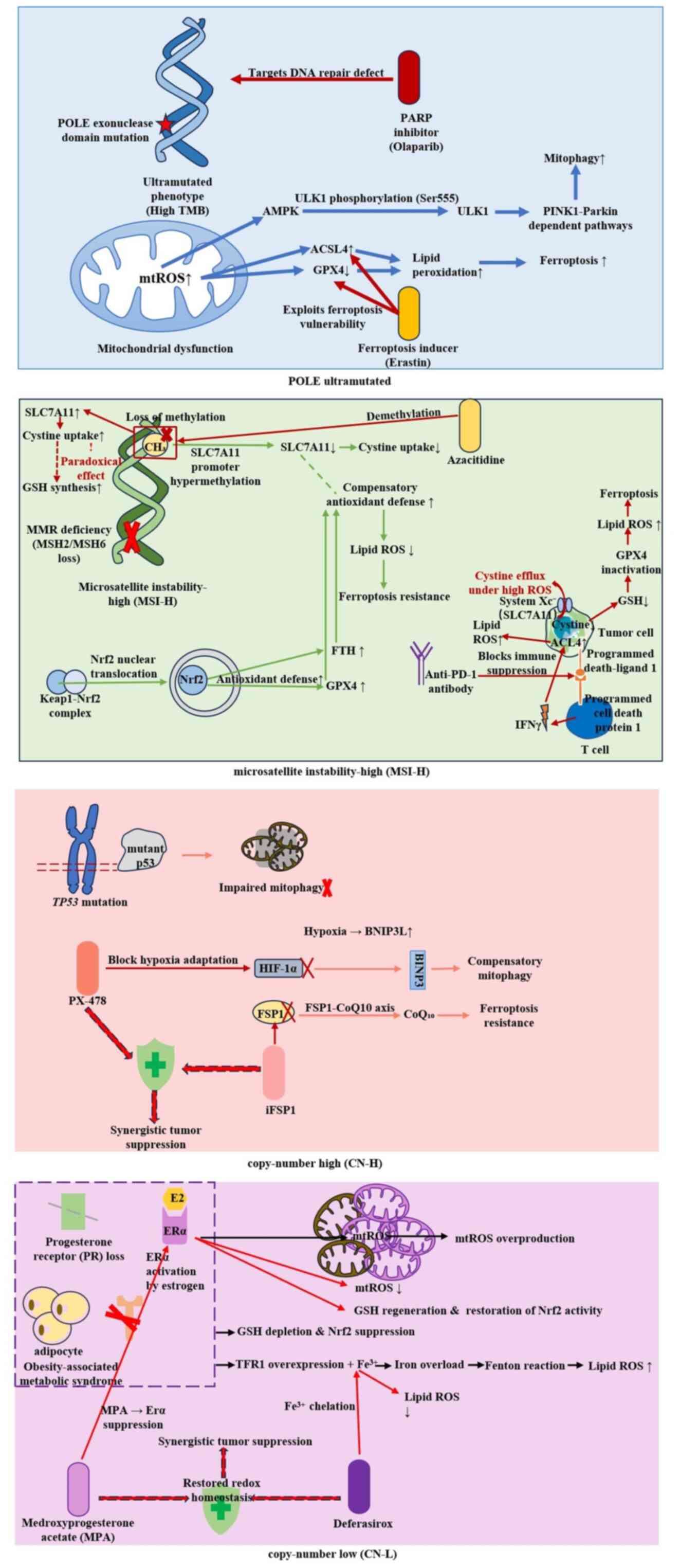

categorizes EC into four subtypes [DNA polymerase ε (POLE)

ultramutated, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), copy-number

low and copy-number high], each with distinct prognoses and

therapeutic implications (4–6). This

classification provides a critical basis for personalized therapy

(7,8). Surgical intervention remains the

cornerstone of EC management. Chemotherapy is mainly reserved for

cases with advanced or recurrent disease, as well as for patients

with high-risk pathological features post-surgery. Nevertheless,

chemoresistance development presents a major therapeutic challenge

(9), leading to treatment failure

and mortality in >90% of patients with advanced-stage disease. A

notable clinical limitation is the lack of effective prognostic

biomarkers and specific targets to overcome chemoresistance

(10). Dysregulation of regulated

cell death (RCD) mechanisms is a recognized cancer hallmark,

contributing to tumor progression and drug resistance. Emerging

evidence has indicated novel RCD pathways, including autophagy,

ferroptosis and pyroptosis, as potential therapeutic targets to

enhance therapeutic efficacy and reverse chemoresistance in EC

(11–16).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), primarily generated

via mitochondrial electron transport chain activity (17,18),

NADPH oxidases (19) and exogenous

stressors, exhibit a dual role in cancer initiation, progression,

suppression and therapy (20).

Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between ROS production

and elimination, is a critical pathogenic factor in numerous

chronic diseases, including cancer (21), cardiovascular diseases (22,23),

metabolic disorders (24) and

neurodegenerative conditions (such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's

diseases) (25). Depending on their

levels and cellular context, ROS can promote tumorigenesis by

inducing DNA damage, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and

immune evasion, or suppress tumor growth by triggering cell death

pathways such as apoptosis and ferroptosis (20,26).

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of RCD marked

by iron accumulation and extensive lipid peroxidation. Key

morphological characteristics include condensed cellular membranes,

with increased density and reduction, or loss of mitochondrial

cristae (27). Ferroptosis involves

disruption of redox homeostasis, marked by depleted antioxidants

[such as glutathione (GSH) and GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4)] and

accumulation of oxidants (such as Fe2+ and lipid ROS)

(28). As primary intracellular ROS

sources, mitochondria are intrinsically linked to ferroptosis.

Mitophagy, a selective autophagic process that degrades damaged

mitochondria via ubiquitin (Ub)-dependent or -independent pathways,

serves as a protective mechanism against stress and is crucial for

mitochondrial quality control (29–32).

Mitophagy and ferroptosis, as two distinct forms of RCD, have been

increasingly implicated in EC (11,16,33,34).

Concurrently, oxidative stress, a key regulator of cellular

metabolism, is closely linked to EC progression (35,36).

The triad of mitophagy, ferroptosis and oxidative stress forms a

dynamic equilibrium, collectively contributing to the pathogenesis

of diverse diseases through their interconnected regulatory

networks (37,38). The present review aims to delineate

the role of oxidative stress as a central hub integrating mitophagy

and ferroptosis in EC pathogenesis, offering novel perspectives for

its prevention and treatment.

ROS, including superoxide anions, free radicals and

hydrogen peroxide, are highly reactive molecules generated

primarily through mitochondrial electron transport and NADPH

oxidase activity (16–19,38,39).

Additional sources include peroxisomal metabolism and endoplasmic

reticulum stress (40,41). Oxidative stress occurs due to a

disruption in the balance between ROS generation and clearance,

serving a notable role in the development of cancer (21–23).

Cellular protection against ROS involves a multi-level defense

system, including enzymatic antioxidants (such as superoxide

dismutase, catalase and GSH peroxidase), non-enzymatic scavengers

(such as vitamin C, vitamins E and GSH) and repair systems for

oxidized biomolecules, which collectively maintain redox

homeostasis (39).

Physiological ROS levels regulate essential cellular

processes (including proliferation, differentiation, survival and

apoptosis). However, supraphysiological ROS levels drive

tumorigenesis and progression (42,43).

Excessive endogenous or exogenous ROS levels induce direct DNA

damage and impair DNA repair mechanisms, causing mutations that

inactivate tumor suppressors (such as p53) or activate oncogenes

(such as KRAS) (44–46).

ROS further promote malignancy by activating

proliferative signaling (including the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK

pathways), and suppressing antitumor immunity via impaired T-cell

differentiation/activation, T-cell death, natural killer cell

dysfunction and M2 macrophage polarization/recruitment (47,48).

ROS facilitate invasion and metastasis through EMT, and induce

EMT-associated cytoskeletal rearrangement (Rho GTPase-dependent),

extracellular matrix degradation (matrix

metalloproteinase-dependent) and angiogenesis [hypoxia-inducible

factor (HIF)-dependent] (49).

Although high ROS levels are crucial in promoting

tumor initiation and progression, excessive ROS levels also serve

an antioncogenic role in cancer (26,50).

Excessively accumulated ROS repress cancer cell growth by

inhibiting cancer cell proliferation through disrupting

nucleotide/ATP synthesis and inducing cell cycle arrest (51). ROS also trigger tumor cell death by

activating endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated, mitochondrial and

p53-dependent apoptotic pathways, along with the ferroptosis

pathway (26). Therefore, targeting

the regulation of ROS levels (for example, using pro-oxidant agents

or inhibiting antioxidant pathways) has emerged as a novel

therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment, aiming to exploit the

‘dual role’ of oxidative stress to achieve selective elimination of

tumor cells.

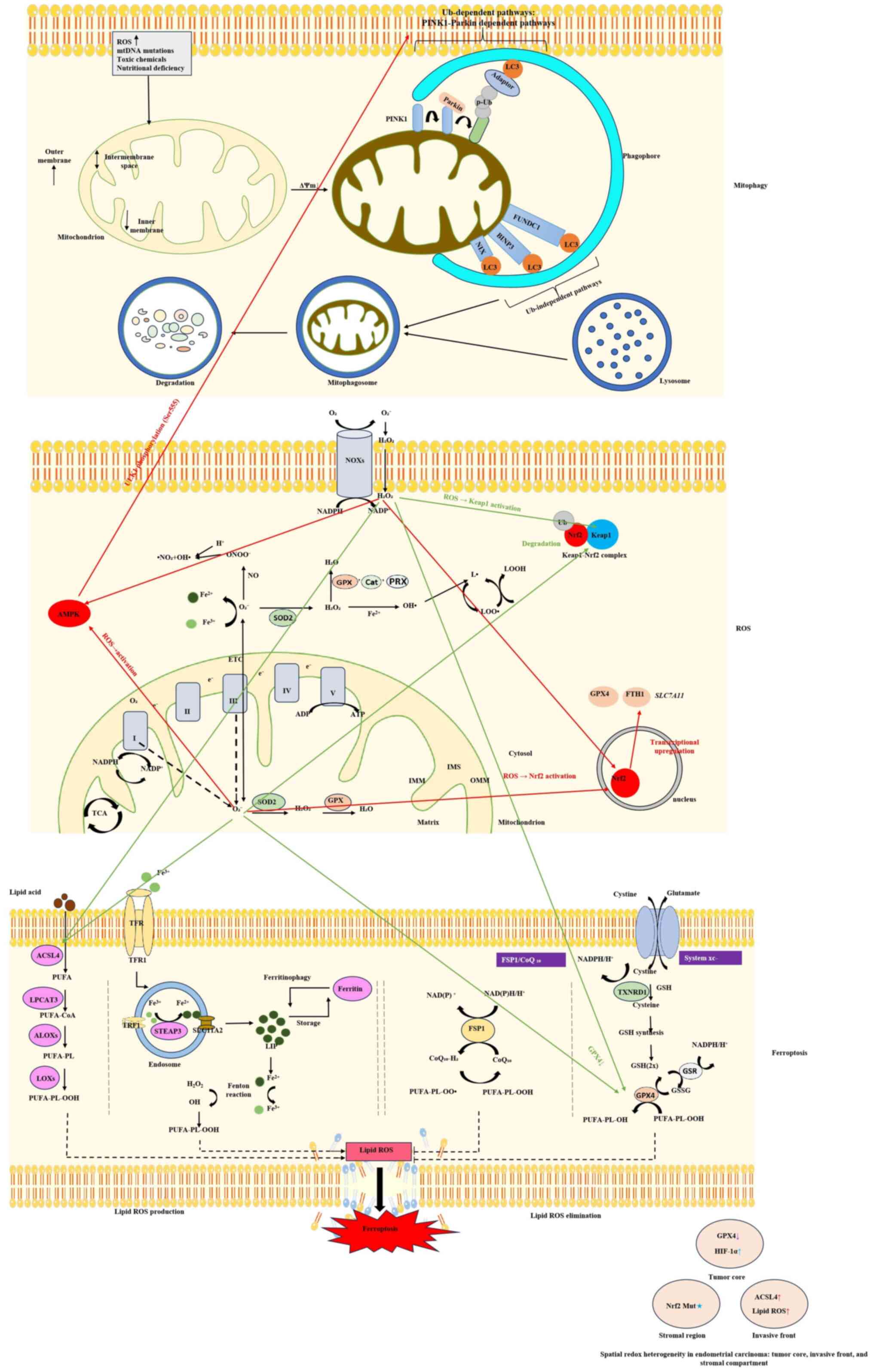

Mitophagy represents a selective type of autophagy

that functions as a protective response to intracellular and

extracellular stress signals (32).

Mitophagy maintains mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis by

eliminating dysfunctional mitochondria, including depolarized,

damaged or superfluous organelles, through lysosomal degradation.

The core molecular mechanisms can be divided into Ub-dependent

pathways and Ub-independent pathways (31). The PTEN-induced kinase 1

(PINK1)/Parkin pathway represents the most well-characterized

Ub-dependent mechanism. Upon mitochondrial depolarization or

damage, PINK1 stabilizes on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM),

and phosphorylates Ub and the E3 Ub ligase Parkin, leading to the

ubiquitination of OMM proteins. Autophagy receptors such as

p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) and optineurin then recognize

ubiquitinated substrates and link them to microtubule-associated

proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC3)-positive autophagosomal

membranes for engulfment (31).

Alternatively, Ub-independent pathways utilize OMM-resident

receptors, including BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting

protein 3 (BNIP3), BNIP3L (also known as NIX) and FUN14

domain-containing protein 1 (FUNDC1), which directly interact with

LC3/GABA type A receptor-associated protein via LC3-interacting

regions to initiate mitophagy. These coordinated mechanisms ensure

the precise elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria, and their

dysregulation is broadly implicated in various pathological states,

including cancer (30,52,53).

Mitophagy is widely reported to exhibit aberrant

activity levels in various cancer types compared with under normal

physiological conditions (54,55).

Current research has revealed its dual role in cancer biology,

demonstrating both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressive functions

depending on the cellular context (56,57).

In its pro-tumorigenic capacity, mitophagy is known to enable

cancer cell survival under stress and facilitates malignant

progression by clearing dysfunctional mitochondria (58). Under hypoxia, mitophagy mediated by

BNIP3 and NIX is known to enhance tumor aggressiveness by lowering

mitochondrial ROS levels, stabilizing HIF-1α, promoting glycolytic

shift and inducing EMT, which collectively increase invasiveness

and metastatic potential (59).

Chemotherapy- or radiotherapy-induced mitochondrial damage can

activate the PINK1/Parkin pathway, which ubiquitinates damaged

mitochondria to block cytochrome c release, thereby potentially

enabling cancer cells to evade apoptosis and develop therapeutic

resistance (60). During

metastasis, FUNDC1-dependent mitophagy is suggested to optimize

energy metabolism to fuel ATP production, supporting cancer cell

migration and invasion (61).

Additionally, mitophagy may suppress NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation by removing

mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns [mitochondrial

DNA (mtDNA) and cardiolipin], thereby reducing secretion of the

pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β and impairing antitumor immunity to

promote immune evasion (62).

Conversely, mitophagy also exerts tumor-suppressive

effects, as supported by multiple lines of evidence (59,63).

In precancerous or early-stage tumors, mitophagy impedes malignant

transformation by eliminating mitochondria harboring oncogenic

damage. For example, mtDNA mutations, which drive early

carcinogenesis, are selectively cleared via NIX/BNIP3-dependent

mitophagy, thereby mitigating ROS-induced nuclear genomic

instability and delaying tumor initiation (64). The tumor suppressor p53 has been

shown to enhance mitophagy by transcriptionally activating DNA

damage-regulated autophagy modulator 1, facilitating the removal of

dysfunctional mitochondria and inducing apoptosis in premalignant

cells, as validated in colorectal precancerous models (65,66).

Furthermore, excessive mitochondrial damage can trigger ‘autosis’,

a form of autophagic cell death, via mitochondrial membrane

potential collapse and ATP depletion, irreversibly eliminating

premalignant cells. In inflammation-associated carcinogenesis,

mitophagy is proposed to block chronic inflammation-driven

tumorigenesis by clearing mitochondrial damage-associated molecular

patterns (such as cardiolipin and mtDNA), thereby inhibiting NLRP3

inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion (67). Critically, the tumor-suppressive

effects of mitophagy are context- and stage-dependent: Activation

of mitophagy in PTEN-deficient or KRAS-mutant precancerous models

reduces hyperproliferative lesions, whereas the same intervention

in advanced tumors may paradoxically promote malignancy due to

metabolic rewiring and survival adaptation. This spatiotemporal

duality underscores the necessity of stage-specific targeting of

mitophagy pathways in cancer therapy (68,69).

Emerging evidence highlights stage- and molecular

context-specific regulation of mitophagy in EC, although research

in this field remains sparse (70).

Dysregulation of the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway, observed in >80% of

EC cases, impairs PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, resulting in the

accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, increased ROS levels,

heightened genomic instability and estrogen-driven proliferation

(71). However, evidence has

revealed that PTEN-deficient EC cells activate an alternative

mitophagy pathway mediated by the autophagy and beclin 1 regulator

1-autophagy-related protein 5 complex, which bypasses Unc-51 like

autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) inhibition and maintains

mitochondrial quality control under mTORC1 hyperactivation

(13). In type I EC, hyperactivated

mTORC1 phosphorylates ULK1 at Ser757, disrupting the

ULK1-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) complex essential for

mitophagy initiation and promoting tumor cell survival (34). Notably, advanced TP53-mutant ECs

exhibit hypoxia-driven compensatory upregulation of

BNIP3L/NIX-mediated mitophagy, which is transcriptionally activated

by HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions to sustain mitochondrial

metabolism and chemoresistance, thereby contributing to the poor

prognosis of p53-aberrant tumors (33). This dual regulatory role,

tumor-suppressive in early stages and pro-tumorigenic in advanced

disease, underscores the need for stage-specific therapeutic

strategies. Restoring PINK1/Parkin signaling in PTEN-deficient

models may improve mitochondrial quality control, while targeting

BNIP3L/NIX in TP53-mutant tumors could enhance chemosensitivity.

However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these

context-dependent effects require further elucidation.

In conclusion, mitophagy serves as both a ‘metabolic

accomplice’ and a ‘genomic custodian’ in EC, with its dualistic

role underscoring the therapeutic conundrum in targeting

mitochondrial quality control. The transition from

tumor-suppressive to pro-survival functions is intricately linked

to disease stage, molecular subtypes (such as POLE-mutated and

TP53-aberrant) and metabolic rewiring driven by PTEN/PI3K

dysregulation or obesity-associated stress (33). Future endeavors must prioritize

stage-adaptive strategies, activating mitophagy to enforce genomic

fidelity in precancerous lesions while inhibiting

FUNDC1/PINK1/Parkin-driven pathways to disrupt metabolic plasticity

in advanced tumors. Integrating multi-omics profiling (such as

mitophagic flux mapping and spatial metabolomics) with clinical

staging will unlock context-specific vulnerabilities, enabling the

design of precision therapies that convert mitophagy from a foe to

an ally in the battle against EC, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent RCD pathway that is

driven by lipid peroxidation, originating from redox imbalance,

dysregulated lipid metabolism and disrupted iron homeostasis

(72); however, cellular adaptation

to these stressors hinges on dynamic modifications of core

regulatory pathways, which paradoxically form the molecular basis

of ferroptosis resistance (29).

The GPX4/GSH axis is a central defense system: System

Xc− [composed of solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11) and solute carrier family 3 member 2] imports cystine for

GSH synthesis and GPX4 utilizes GSH to reduce lipid peroxides.

Resistance often arises from GPX4 or System Xc−

upregulation (73). Alternatively,

the ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)-coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

axis has been identified as a key GPX4-independent pathway wherein

FSP1 reduces ubiquinone to ubiquinol, which quenches lipid radicals

(28). Acyl-CoA synthetase

long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) is a well-established promoter

of ferroptosis that enriches membranes with polyunsaturated fatty

acids; its suppression diminishes ferroptosis sensitivity (74). Iron metabolism serves a dual role:

Iron overload amplifies lipid peroxidation, while iron storage

proteins [such as ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1)] buffer toxicity.

The nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway is a

recognized suppressor of ferroptosis, primarily by activating

antioxidant genes (such as GPX4 and FTH1) (29,75).

p53 exerts context-dependent effects, which may include inhibiting

SLC7A11 or activating spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1

(65–67).

Ferroptosis exhibits a dynamically regulated dual

role in EC progression: Its suppressed state drives tumor invasion,

metastasis and therapy resistance through multifaceted molecular

mechanisms, while ferroptosis-inducing strategies have the

potential to reverse drug resistance and inhibit metastasis

(16,76–78).

The core regulatory hubs GPX4 and Nrf2 are upregulated in EC and

are functionally synergistic. GPX4 maintains membrane stability by

reducing toxic lipid peroxides (such as phosphatidylethanolamine

hydroperoxide), whereas Nrf2 enhances antioxidant defense via

transcriptional activation of SLC7A11 (cystine/glutamate

antiporter) and FTH1 (iron storage protein) (79–81). A

multivariate analysis of the TCGA-uterine corpus endometrial

carcinoma cohort revealed that GPX4/Nrf2 co-upregulation was

independently associated with lymph node metastasis risk [odds

ratio (OR), 3.21; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.38–7.45; P=0.007]

and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics III/IV

staging (OR, 2.94; P=0.012) (82,83).

EC cells evade ferroptosis through epigenetic reprogramming,

including the microRNA (miR)-424-5p-mediated destabilization of

ACSL4 mRNA via 3′untranslated region binding (validated by

dual-luciferase assays) and hypermethylation of the ACSL4 promoter

CpG island (methylation β-value >0.6; P<0.001), collectively

suppressing pro-ferroptotic lipid peroxidation (83). Iron metabolism dysregulation

exacerbates malignant phenotypes: FTH1 upregulation reduces the

labile iron pool by enhancing iron storage, thereby inhibiting

Fenton reaction-driven lipid peroxidation, while divalent metal

transporter 1 mediates lysosomal iron efflux to amplify ferroptosis

sensitivity in metastatic niches. Concurrently, transferrin

receptor 1 (TFR1)-mediated iron overload activates pro-angiogenic

factors (such as VEGF) via the mitochondrial ROS/HIF-1α axis

(84). Clinical translational

studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of combining

erastin with cisplatin: Cisplatin-resistant EC cells (Ishikawa-CR

line) acquire ferroptosis resistance via GPX4/FSP1 dual-pathway

upregulation, whereas erastin/cisplatin co-treatment induces

caspase-3-independent cell death (4.2-fold apoptosis increase;

P<0.001) (11,85). Metformin suppresses SLC7A11

transcription via the AMPK/p53 axis (chromatin

immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR-validated), reducing

peritoneal metastases by 68% in patient-derived xenograft (PDX)

models (P=0.002) (86,87). Interim analysis of the NCT04817332

phase II trial demonstrated improved objective response rates with

erastin/carboplatin-paclitaxel combination therapy in recurrent EC

(51 vs. 32% for monotherapy; P=0.039), albeit with increased

ferroptosis-related toxicity (grade 3 anemia, 28 vs. 12%) (88). Parallel preclinical investigations

provided complementary insights: To further elucidate the cellular

diversity underlying treatment responses, single-cell RNA

sequencing of patient-derived EC samples revealed significant

heterogeneity in ferroptosis-related gene expression profiles.

Meanwhile, leveraging nanodelivery systems to encapsulate

ferroptosis inducers has been established as a promising strategy

in preclinical models to enhance tumor selectivity and reduce

systemic toxicity (89). These

findings systematically elucidate the pivotal role of ferroptosis

dysregulation in EC progression and provide novel directions for

developing redox metabolism-targeted precision therapies (16).

ROS serve as key signaling molecules that

dynamically coordinate the balance between mitophagy and

ferroptosis. Mitochondrial ROS promote PINK1/Parkin-mediated

mitophagy, which clears damaged mitochondria and limits lipid

peroxidation (31,52). Conversely, endoplasmic

reticulum-derived ROS activate the inositol-requiring enzyme

1α/c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway, upregulating ACSL4 to enhance

membrane polyunsaturated fatty acid incorporation and ferroptosis

sensitivity (90). Lipid

peroxidation products [such as phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOH)]

further amplify mitochondrial damage, establishing a feedforward

loop (91). This interplay exhibits

concentration dependence in EC: Physiological ROS levels promote

cytoprotective mitophagy via AMPK-ULK1 signaling to suppress early

malignant transformation (92),

whereas chemotherapy (such as cisplatin)-induced ROS trigger

ferroptosis-dominated cell death by depleting GSH and inhibiting

GPX4 (93). A previous study has

revealed that estrogen receptor α (ERα) activation in EC cells

simultaneously upregulates mitochondrial ROS production and

autophagy-related genes (such as BNIP3), driving dynamic imbalances

between mitophagy and ferroptosis to fuel tumor progression

(94).

Mitophagy and ferroptosis are interconnected through

shared molecular nodes, forming a bidirectional regulatory network

(95). On the one hand, mitophagy

suppresses ferroptosis by degrading ACSL4, a key enzyme that

catalyzes polyunsaturated fatty acid-phospholipid synthesis, and

removing lipid peroxidation precursors (96). On the other hand,

ferroptosis-derived lipid peroxides (such as PLOOH) activate

PINK1/Parkin or NIX/BNIP3L-dependent mitophagy via mitochondrial

membrane oxidation (97). Emerging

evidence demonstrates that ACSL4, a ferroptosis-specific regulator,

induces mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, leading to membrane

depolarization and subsequent mitophagy initiation (98). Additionally, labile iron released

during ferroptosis exacerbates mitochondrial oxidative damage

through Fenton reactions, creating an ‘iron-ROS-mitophagy’ cycle.

In EC, PTEN loss-induced dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

disrupts redox homeostasis via dual mechanisms: Impairing ULK1

phosphorylation to block protective mitophagy and downregulating

GPX4 to heighten ferroptosis susceptibility (33). Combined targeting of both pathways

(for example, using mitophagy inducer urolithin A + ferroptosis

activator RSL3) synergistically inhibits tumor growth in

preclinical models, highlighting the therapeutic potential of

modulating the ROS-mitophagy-ferroptosis axis (16,71),

as illustrated in Fig. 2.

EC is characterized by alterations in redox

homeostasis that is driven by hormonal imbalances and somatic

mutations. Estrogen dominance, a hallmark of type I EC, activates

ERα-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis, amplifying superoxide

generation while epigenetically suppressing Nrf2-dependent

antioxidant defenses through promoter hypermethylation of NFE2 like

bZIP transcription factor 2 (NFE2L2) (99). Conversely, progesterone exerts

protective effects by binding to the progesterone receptor-B

isoform, upregulating thioredoxin reductase and GSH synthetase

through cAMP-response element binding protein phosphorylation, a

mechanism disrupted in obesity-associated progesterone resistance

(100). PTEN loss (occurring in

40–80% of cases) exacerbates this imbalance via dual pathways: i)

Hyperactivation of PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 inhibits ULK1-driven mitophagy,

allowing the accumulation of ROS-generated damaged mitochondria;

and ii) transcriptional repression of the FSP1/CoQ10 axis through

yes-associated protein and transcriptional coactivator with

PDZ-binding motif nuclear translocation, sensitizing cells to

ferroptosis (101,102). Single-cell multi-omics has

identified PTEN-null CD44-positive aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family

member A1-high cancer stem cells (CSCs) that evade ferroptosis via

aldehyde detoxification and CoQ10 recycling, establishing a

redox-buffered niche resistant to oxidative stress (103).

Redox adaptations exhibit temporal evolution during

disease progression: i) Premalignant lesions exhibit compensatory

upregulation of mitophagic machinery (elevated Parkin RBR E3

ubiquitin-protein ligase and BNIP3 levels) with concomitant

suppression of ferroptosis drivers (low ACSL4 expression); ii)

early invasive tumors activate the FSP1/CoQ10 antioxidant system

and suppress mitophagy through mTORC1-mediated transcription factor

EB phosphorylation, resulting in lipid peroxide accumulation; and

iii) advanced tumors undergo metabolic rewiring (glutamine-driven

oxidative phosphorylation and HIF-1α signaling) to enforce

mitophagy dependency and ferroptosis resistance (104–106). These stage-specific adaptations

inform rational therapeutic targeting: mTOR inhibition with

rapamycin restores protective mitophagy in premalignant states,

while FSP1 inhibitors combined with ferroptosis inducers (such as

imidazole ketone erastin) overcome therapy resistance in advanced

disease.

Dynamic regulation of the Nrf2/Kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) axis and EC-specific

dysregulation

The Nrf2/Keap1 pathway serves as a central hub for

oxidative stress responses, integrating antioxidant defenses,

mitophagy and ferroptosis to maintain cellular homeostasis. Under

physiological conditions, Keap1-mediated ubiquitination and

degradation of Nrf2 restrict its activity, while oxidative stress

triggers Nrf2 nuclear translocation, activating target genes such

as heme oxygenase 1 (which degrades pro-ferroptotic labile iron)

and SQSTM1/p62 (which promotes clearance of damaged mitochondria

via selective autophagy) (107).

In EC, KEAP1 loss-of-function mutations or NFE2L2 (encoding Nrf2)

amplifications lead to constitutive Nrf2 activation, driving

p62-dependent mitophagy and suppressing ferroptosis to favor tumor

survival. Estrogen enhances NFE2L2 transcription via ERα binding to

its promoter, while progesterone upregulates Keap1 expression

through PR-B, establishing hormone-dependent oscillations in Nrf2

activity (100,108). Furthermore, Nrf2-hyperactive

tumors reprogram metabolism by upregulating glutaminase and the

cystine transporter xCT/SLC7A11, sustaining mitochondrial function

and ferroptosis resistance, a mechanism particularly prominent in

PTEN-deficient subtypes (13).

Fe-S cluster biogenesis acts as a critical node

linking mitochondrial integrity and ferroptosis sensitivity.

Deficiencies in mitochondrial Fe-S assembly systems [such as

iron-sulfur cluster assembly enzyme (ISCU) and frataxin] disrupt

electron transport chain function, causing superoxide accumulation

and PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, while cytosolic labile iron

pool expansion exacerbates lipid peroxidation via Fenton reactions,

increasing ferroptosis susceptibility (109). In EC, ISCU promoter

hypermethylation and miR-214 upregulation synergistically impair

Fe-S cluster synthesis, whereas cancer-associated fibroblasts

rescue redox homeostasis by delivering Fe-S complementation factors

(such as cysteine desulfurase) via exosomes (110,111). Therapeutic Fe-S cluster donors

(such as Fe4S4) restore mitochondrial

function while inducing ferroptosis, exhibiting synergistic

efficacy in PTEN-deficient organoid models and offering a novel

strategy to overcome therapy resistance (103).

The spatiotemporal dynamics of oxidative stress

critically influence therapeutic responses in EC. Chemotherapy

(e.g., cisplatin) induces biphasic ROS generation (112): Acute-phase mitochondrial ROS

activate AMPK-ULK1-mediated protective mitophagy, promoting cell

survival, while chronic-phase ROS accumulation triggers ferroptosis

via GSH depletion and GPX4 inactivation. The circadian regulators

BMAL1 and CLOCK rhythmically control the expression of autophagy

genes like LC3B. This regulation drives a peak in autophagic

activity at night, which helps to counteract the oxidative damage

that accumulates during the day (113). Chronotherapy strategies leveraging

these rhythms [e.g., administering ferroptosis inducers (such as

erastin) during active circadian phases] synergize with endogenous

ROS fluctuations, enhancing treatment efficacy (114,115).

Spatial heterogeneity further shapes oxidative

stress regulation: Hypoxic tumor cores suppress ferroptosis via

HIF-1α-mediated downregulation of ACSL4 and TFR1, while

upregulating BNIP3-driven mitophagy to maintain CSC stemness. By

contrast, high-ROS microenvironments at invasive fronts activate

NF-κB/STAT3 signaling to promote EMT and FSP1/CoQ10-dependent

ferroptosis resistance (112,116). CSCs remodel stromal niches via

exosomal transfer of antioxidants (such as glutathione

S-transferase P1) and iron chelators, creating localized ‘oxidative

sanctuaries’ (117).

Nanotherapeutic strategies exploiting this heterogeneity, such as

ROS-responsive carriers delivering autophagy inhibitors to cores

and ferroptosis inducers to invasive fronts, exhibit potent

antitumor effects in preclinical models (118).

In summary, the spatiotemporal regulation of

oxidative stress defines distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities,

enabling chronotherapeutic and microenvironment-targeted

interventions.

The oxidative stress network offers novel biomarkers

and therapeutic strategies (119).

Combined evaluation of mitophagy (for example, mtDNA copy number)

and ferroptosis markers (for example, lipid peroxidation products)

enables real-time monitoring of tumor redox status (120). CD8+ T cell-derived IFNγ

enhances ferroptosis susceptibility via STAT1/interferon regulatory

factor 1/ACSL4 signaling, suggesting synergies between immune

checkpoint inhibitors and ferroptosis inducers (121). Advanced imaging technologies (such

as nanoprobe-based iron tracking) integrated with artificial

intelligence (AI) algorithms accurately predict ferroptosis

sensitivity (122).

Spatiotemporally optimized combinations, such as

sequential autophagy inhibition followed by ferroptosis induction,

overcome compensatory resistance (123,124). ROS-responsive nanocarriers achieve

precise drug release by exploiting microenvironmental features

(such as low pH and high GSH levels), effectively targeting both

hypoxic cores and invasive fronts. Additionally, targeting

PTEN-null vulnerabilities with mTOR and glutaminase inhibitors

synergistically blocks mitophagy and induces ferroptosis, achieving

remarkable responses in patient-derived models (101).

These advances highlight the clinical potential of

targeting oxidative stress dynamics for precision therapy in

EC.

Key challenges remain in modeling oxidative stress

dynamics. Current organoid systems lack spatiotemporal resolution

for tumor-microenvironment crosstalk (for example, immune cell

interactions and hormone gradients) (125). Integrating single-cell

transcriptomics with spatial metabolomics is essential to resolve

redox heterogeneity and niche-specific adaptations (126,127). Mechanistic gaps persist regarding

the subcellular localization of ferroptosis regulators (such as

FSP1) and the crosstalk between Nrf2 and circadian pathways

(96–99). Compensatory activation, such as GPX4

inhibition upregulating FSP1/CoQ10, requires sequential targeting

strategies tailored to tumor heterogeneity (128–131). AI-driven drug discovery (for

example, using deep generative models) predicts synergistic

combinations (such as mTOR inhibitors with ferroptosis inducers),

validated in PDX models (132).

Future studies must integrate computational biology

and high-resolution omics to map the oxidative stress landscape,

enabling personalized therapeutic strategies.

The establishment of oxidative stress as a nexus

between mitophagy and ferroptosis unveils a novel therapeutic

landscape in EC (95,120,133). However, clinical translation is

impeded by defined knowledge gaps and practical challenges that

must be prioritized in future research.

A primary unresolved question is the spatiotemporal

dynamics of this interplay within the tumor microenvironment (TME).

The precise thresholds of oxidative stress that dictate a switch

from pro-survival mitophagy to lethal ferroptosis across different

molecular subtypes and disease stages remain unmapped (120). This context-dependent duality

necessitates a deeper understanding of how metabolic and hormonal

cues influence this balance. Concurrently, the immunological

consequences of targeting this axis constitute a critical knowledge

gap. It is not known whether ferroptosis induction or mitophagy

modulation can enhance antitumor immunity by, for example,

triggering immunogenic cell death or reversing immunosuppressive

niches, which would create a rationale for combinations with

immunotherapy.

The compelling preclinical evidence stands in stark

contrast to the current clinical trial landscape, highlighting a

significant translation gap. To definitively assess the clinical

translation of these mechanisms, a systematic search of the

ClinicalTrials.gov registry (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) was conducted on

September 10, 2025. The search strategy utilized keywords including

‘endometrial cancer’, ‘ferroptosis’, ‘mitophagy’ and related terms.

Crucially, the following exclusion criteria were applied: i) Trials

not focused on EC; ii) non-interventional studies; and iii) trials

where direct targeting of mitophagy or induction of ferroptosis was

not an explicit primary strategy. It is important to note that this

search constituted a systematic search of trial registries and not

a systematic review; as such, a formal quality assessment of the

identified trials or a synthesis of data from existing publications

was not performed, which is a limitation of this methodological

approach.

This rigorous search confirmed a complete absence of

clinical trials specifically designed to directly target mitophagy

or induce ferroptosis as a primary therapeutic strategy in EC.

However, the search identified several interventional trials

investigating agents with indirect mechanistic links to these

pathways: i) mTOR inhibitors: Active and completed trials

investigating everolimus (such as NCT01797523 and NCT00870337) are

relevant due to the established role of mTOR signaling in

regulating the mitophagic flux and cellular stress responses; and

ii) AMPK activators: Multiple trials involving metformin (such as

NCT04576104, NCT07145827 and NCT01205672) are of interest based on

preclinical evidence suggesting its potential to modulate AMPK

activity and sensitize cells to ferroptosis.

The absence of direct-targeting trials underscores

the nascent stage of translating these concepts into clinical

applications. Conversely, the prevalence of trials involving mTOR

inhibitors and AMPK activators suggests a growing clinical

recognition of the importance of targeting broader metabolic and

stress-response pathways in EC, which may indirectly influence

mitophagy and ferroptosis (134,135).

Translation of these insights faces significant

barriers. The lack of robust, dynamic biomarkers (such as

circulating lipid peroxidation products) beyond static molecular

classification severely hinders patient stratification.

Furthermore, managing systemic toxicity, particularly of potent

ferroptosis inducers, is a paramount concern. Overcoming this

requires the development of advanced nano-theranostic platforms

engineered for EC-specific targeting [e.g., against folate receptor

α (FRα)] and TME-responsive drug release (e.g., triggered by high

ROS levels) to maximize efficacy and minimize off-target effects.

The inherent compensatory activation of parallel pathways (such as

upregulation of the FSP1/CoQ10 axis upon GPX4 inhibition) further

necessitates the rational design of combination therapies.

In summary, the present review consolidates evidence

that oxidative stress functions as a critical mechanistic nexus

coordinating mitophagy and ferroptosis in EC. The deregulation of

this axis presents a compelling therapeutic vulnerability.

The future of targeting this nexus lies in precision

medicine strategies that directly address the aforementioned

challenges, with tailored approaches for both mitophagy and

ferroptosis: i) Biomarker-guided stratification: Future efforts

must integrate functional redox biomarkers with molecular subtyping

to identify patient populations most likely to benefit, such as

those with PTEN-deficient tumors exhibiting heightened ferroptosis

sensitivity. For mitophagy, this necessitates stage-aware

strategies, such as activating it to enforce genomic fidelity in

precancerous/early-stage lesions (such as PTEN-deficient) while

inhibiting its pro-survival function in advanced or

therapy-resistant tumors (such as TP53-mutant or BNIP3L/NIX-high).

ii) Intelligent therapeutic platforms: The development of

stimuli-responsive nanocarriers is indispensable to overcome the

dual challenges of drug delivery efficiency and systemic toxicity,

enabling spatially controlled therapy within the TME for

ferroptosis inducers. Complementary efforts should develop

mitochondrially-targeted delivery systems for mitophagy modulators

(such as PINK1 activators or FUNDC1 inhibitors) to achieve

organelle-specific precision. iii) Rational combination therapies:

Overcoming adaptive resistance necessitates ‘two-pronged’

strategies, such as co-inhibiting parallel defense pathways (for

example, GPX4 and FSP1) or combining ferroptosis inducers with

immunotherapy in appropriate subtypes (such as MSI-H) to exploit

immunogenic cell death. Similarly, mitophagy inhibition can be

rationally combined with standard chemo-/radiotherapy to prevent

treatment resistance or with ferroptosis inducers to

synergistically disrupt mitochondrial metabolism and redox

homeostasis.

By addressing the knowledge gaps and embracing these

precision approaches, the transformative potential of targeting the

oxidative stress-mitophagy-ferroptosis axis can be realized, paving

the way for novel and effective management strategies in EC.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Medical and Health Science and

Technology Development Program Project of Shandong Province (grant

no. 2019WS335).

Not applicable.

FL designed the study and critically revised the

manuscript. QY wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. LR

performed analysis and interpretation of the underlying data to

draw the figures and authored and revised the figure legends and

the corresponding part of the Methods section. FR participated in

the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, ME JF,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and DVM AJ: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. 74:229–263. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mili N, Paschou SA, Goulis DG, Dimopoulos

MA, Lambrinoudaki I and Psaltopoulou T: Obesity, metabolic

syndrome, and cancer: Pathophysiological and therapeutic

associations. Endocrine. 74:478–497. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Henley SJ, Ward E, Scott S, Ma J, Anderson

RN, Firth AU, Thomas CC, Islami F, Weir HK, Lewis DR, et al: Annual

report to the nation on the status of cancer, Part 1: National

cancer statistics. Cancer. 126:2225–2249. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS and

Dalamaga M: Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms

and perspectives. Metabolism. 92:121–135. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Karpel HC, Slomovitz B, Coleman RL and

Pothuri B: Treatment options for molecular subtypes of endometrial

cancer in 2023. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 35:270–278. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Alexa M, Hasenburg A and Battista MJ: The

TCGA molecular classification of endometrial cancer and its

possible impact on adjuvant treatment decisions. Cancers.

13:14782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Vermij L, Smit V, Nout R and Bosse T:

Incorporation of molecular characteristics into endometrial cancer

management. Histopathology. 76:52–63. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Galant N, Krawczyk P, Monist M, Obara A,

Gajek Ł, Grenda A, Nicoś M, Kalinka E and Milanowski J: Molecular

classification of endometrial cancer and its impact on therapy

selection. Int J Mol Sci. 25:58932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Brasseur K, Gévry N and Asselin E:

Chemoresistance and targeted therapies in ovarian and endometrial

cancers. Oncotarget. 8:4008–4042. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wilson EM, Eskander RN and Binder PS:

Recent therapeutic advances in gynecologic oncology: A review.

Cancers. 16:7702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Žalytė E: Ferroptosis, metabolic rewiring,

and endometrial cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 25:752023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Al Mamun A, Geng P, Wang S and Shao C:

Role of pyroptosis in endometrial cancer and its therapeutic

regulation. J Inflamm Res. 17:7037–7056. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Devis-Jauregui L, Eritja N, Davis ML,

Matias-Guiu X and Llobet-Navàs D: Autophagy in the physiological

endometrium and cancer. Autophagy. 17:1077–1095. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fukuda T and Wada-Hiraike O: The Two-faced

role of autophagy in endometrial cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10:8394162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nuñez-Olvera SI, Gallardo-Rincón D,

Puente-Rivera J, Salinas-Vera YM, Marchat LA, Morales-Villegas R

and López-Camarillo C: Autophagy machinery as a promising

therapeutic target in endometrial cancer. Front Oncol. 9:13262019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu J, Zhang L, Wu S and Liu Z:

Ferroptosis: Opportunities and challenges in treating endometrial

cancer. Front Mol Biosci. 9:9298322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Brand MD: The sites and topology of

mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol. 45:466–472.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

West AP, Shadel GS and Ghosh S:

Mitochondria in innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol.

11:389–402. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lambeth JD and Neish AS: Nox enzymes and

new thinking on reactive oxygen: A Double-edged sword revisited.

Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 9:119–145. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang Y, Qi H, Liu Y, Duan C, Liu X, Xia T,

Chen D, Piao HL and Liu HX: The double-edged roles of ROS in cancer

prevention and therapy. Theranostics. 11:4839–4857. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Perillo B, Di Donato M, Pezone A, Di Zazzo

E, Giovannelli P, Galasso G, Castoria G and Migliaccio A: ROS in

cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp Mol Med.

52:192–203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

van der Pol A, van Gilst WH, Voors AA and

van der Meer P: Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: Past,

present and future. Eur J Heart Fail. 21:425–435. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Senoner T and Dichtl W: Oxidative stress

in cardiovascular diseases: Still a therapeutic target? Nutrients.

11:20902019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rezzani R and Franco C: Liver, oxidative

stress and metabolic syndromes. Nutrients. 13:3012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Teleanu DM, Niculescu AG, Lungu II, Radu

CI, Vladâcenco O, Roza E, Costăchescu B, Grumezescu AM and Teleanu

RI: An overview of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and

neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 23:59382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Huang R, Chen H, Liang J, Li Y, Yang J,

Luo C, Tang Y, Ding Y, Liu X, Yuan Q, et al: Dual role of reactive

oxygen species and their application in cancer therapy. J Cancer.

12:5543–5561. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An Iron-dependent form of Non-apoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tang D, Chen X, Kang R and Kroemer G:

Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell

Res. 31:107–125. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao

N, Sun B and Wang G: Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell

Death Dis. 11:882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xu Y, Shen J and Ran Z: Emerging views of

mitophagy in immunity and autoimmune diseases. Autophagy. 16:3–17.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lu Y, Li Z, Zhang S, Zhang T, Liu Y and

Zhang L: Cellular mitophagy: Mechanism, roles in diseases and small

molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics. 13:736–766.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Onishi M, Yamano K, Sato M, Matsuda N and

Okamoto K: Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of

mitophagy. EMBO J. 40:e1047052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Czegle I, Huang C, Soria PG, Purkiss DW,

Shields A and Wappler-Guzzetta EA: The role of genetic mutations in

mitochondrial-driven cancer growth in selected tumors: Breast and

gynecological malignancies. Life. 13:9962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Musicco C, Cormio G, Pesce V, Loizzi V,

Cicinelli E, Resta L, Ranieri G and Cormio A: Mitochondrial

dysfunctions in type I endometrial carcinoma: Exploring their role

in oncogenesis and tumor progression. Int J Mol Sci. 19:20762018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yıldırım E, Türkler C, Görkem Ü, Şimşek

ÖY, Yılmaz E and Aladağ H: The relationship between oxidative

stress markers and endometrial hyperplasia: A case-control study.

Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 18:298–303. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bukato K, Kostrzewa T, Gammazza AM,

Gorska-Ponikowska M and Sawicki S: Endogenous estrogen metabolites

as oxidative stress mediators and endometrial cancer biomarkers.

Cell Commun Signal. 22:2052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gao Y, Sun W, Wang J, Zhao D, Tian H, Qiu

Y, Ji S, Wang S, Fu Q, Zhang F, et al: Oxidative stress induces

ferroptosis in tendon stem cells by regulating mitophagy through

cGAS-STING pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 138:1126522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Granata S, Votrico V, Spadaccino F,

Catalano V, Netti GS, Ranieri E, Stallone G and Zaza G: Oxidative

Stress and Ischemia/reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation:

Focus on ferroptosis, mitophagy and new antioxidants. Antioxidants

(Basel). 11:7692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jomova K, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH,

Nepovimova E, Kuca K and Valko M: Several lines of antioxidant

defense against oxidative stress: antioxidant enzymes,

nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and

low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch Toxicol. 98:1323–1367.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zorov DB, Juhaszova M and Sollott SJ:

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS

Release. Physiol Rev. 94:909–950. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Phaniendra A, Jestadi DB and Periyasamy L:

Free Radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implication

in various diseases. Indian J Clin Biochem. 30:11–26. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Canli Ö, Nicolas AM, Gupta J, Finkelmeier

F, Goncharova O, Pesic M, Neumann T, Horst D, Löwer M, Sahin U and

Greten FR: Myeloid Cell-derived reactive oxygen species induce

epithelial mutagenesis. Cancer Cell. 32:869–883.e5. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kumari S, Badana AK G MM, G S and Malla R:

Reactive oxygen species: A key constituent in cancer survival.

Biomark Insights. 13:11772719187553912018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Iskandar K, Foo J, Liew AQX, Zhu H, Raman

D, Hirpara JL, Leong YY, Babak MV, Kirsanova AA and Armand AS: A

novel MTORC2-AKT-ROS axis triggers mitofission and

mitophagy-associated execution of colorectal cancer cells upon

drug-induced activation of mutant KRAS. Autophagy. 20:1418–1441.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Srinivas US, Tan BWQ, Vellayappan BA and

Jeyasekharan AD: ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox

Biol. 25:1010842018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu B, Chen Y and St Clair DK: ROS and

p53: Versatile partnership. Free Radic Biol Med. 44:1529–1535.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang Y, Choksi S, Chen K, Pobezinskaya Y,

Linnoila I and Liu ZG: ROS play a critical role in the

differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages and the

occurrence of Tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Res. 23:898–914.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhong LM, Liu ZG, Zhou X, Song SH, Weng

GY, Wen Y, Liu FB, Cao DL and Liu YF: Expansion of PMN-myeloid

derived suppressor cells and their clinical relevance in patients

with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 95:157–163. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jiang J, Wang K, Chen Y, Chen H, Nice EC

and Huang C: Redox regulation in tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal

transition: molecular basis and therapeutic strategy. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 2:170362017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Snezhkina AV, Kudryavtseva AV, Kardymon

OL, Savvateeva MV, Melnikova NV, Krasnov GS and Dmitriev AA: ROS

generation and antioxidant defense systems in normal and malignant

cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:61758042019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Dey P, Baddour J, Muller F, Wu CC, Wang H,

Liao WT, Lan Z, Chen A, Gutschner T, Kang Y, et al: Genomic

deletion of malic enzyme 2 confers collateral lethality in

pancreatic cancer. Nature. 542:119–123. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang S, Long H, Hou L, Feng B, Ma Z, Wu Y,

Zeng Y, Cai J, Zhang DW and Zhao G: The mitophagy pathway and its

implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8:3042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Orvedahl A, Sumpter R, Xiao G, Ng A, Zou

Z, Tang Y, Narimatsu M, Gilpin C, Sun Q and Roth M: Image-based

Genome-Wide siRNA screen identifies selective autophagy factors.

Nature. 480:113–117. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Vara-Perez M, Felipe-Abrio B and Agostinis

P: Mitophagy in cancer: A tale of adaptation. Cells. 8:4932019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ferro F, Servais S, Besson P, Roger S,

Dumas JF and Brisson L: Autophagy and mitophagy in cancer metabolic

remodelling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 98:129–138. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Peoples JN, Saraf A, Ghazal N, Pham TT and

Kwong JQ: Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart

disease. Exp Mol Med. 51:1622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Scheibye-Knudsen M, Fang EF, Croteau DL,

Wilson DM and Bohr VA: Protecting the mitochondrial powerhouse.

Trends Cell Biol. 25:158–170. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wu W, Xu H, Wang Z, Mao Y, Yuan L, Luo W,

Cui Z, Cui T, Wang XL and Shen YH: PINK1-Parkin-Mediated mitophagy

protects mitochondrial integrity and prevents metabolic

stress-induced endothelial injury. PLoS One. 10:e01324992015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Song C, Pan S, Zhang J, Li N and Geng Q:

Mitophagy: A novel perspective for insighting into cancer and

cancer treatment. Cell Prolif. 55:e133272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chen Z, Liu L, Cheng Q, Li Y, Wu H, Zhang

W, Zhang W, Wang Y, Sehgal SA, Siraj S, et al: Mitochondrial E3

ligase MARCH5 regulates FUNDC1 to fine-tune hypoxic mitophagy. EMBO

Rep. 18:495–509. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Li J, Agarwal E, Bertolini I, Seo JH,

Caino MC, Ghosh JC, Kossenkov AV, Liu Q, Tang HY, Goldman AR, et

al: The mitophagy effector FUNDC1 controls mitochondrial

reprogramming and cellular plasticity in cancer cells. Sci Signal.

13:eaaz82402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Poole LP and Macleod KF: Mitophagy in

tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 78:3817–3851.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Akabane S, Matsuzaki K, Yamashita S, Arai

K, Okatsu K, Kanki T, Matsuda N and Oka T: Constitutive activation

of PINK1 protein leads to proteasome-mediated and Non-apoptotic

cell death independently of mitochondrial autophagy. J Biol Chem.

291:16162–16174. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Song C, Pan S, Zhang J, Li N and Geng Q:

Mitophagy: A novel perspective for insighting into cancer and

cancer treatment. Cell Prolif. 55:e133272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu K, Shi Y, Guo XH, Ouyang YB, Wang SS,

Liu DJ, Wang AN, Li N and Chen DX: Phosphorylated AKT inhibits the

apoptosis induced by DRAM-mediated mitophagy in hepatocellular

carcinoma by preventing the translocation of DRAM to mitochondria.

Cell Death Dis. 5:e10782014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Yin K, Lee J, Liu Z, Kim H, Martin DR, Wu

D, Liu M and Xue X: Mitophagy protein PINK1 suppresses colon tumor

growth by metabolic reprogramming via p53 activation and reducing

acetyl-CoA production. Cell Death Differ. 28:2421–2435. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Chen L, Mao LS, Xue JY, Jian YH, Deng ZW,

Mazhar M, Zou Y, Liu P, Chen MT, Luo G and Liu MN: Myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury: The balance mechanism between

mitophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome. Life Sci. 355:1229982024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Ikeda H, Kawase K, Nishi T, Watanabe T,

Takenaga K, Inozume T, Ishino T, Aki S, Lin J, Kawashima S, et al:

Immune evasion through mitochondrial transfer in the tumour

microenvironment. Nature. 638:225–236. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Wang SF, Tseng LM and Lee HC: Role of

mitochondrial alterations in human cancer progression and cancer

immunity. J Biomed Sci. 30:612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Sun R, Zhou X, Wang T, Liu Y, Wei L, Qiu

Z, Qiu C and Jiang J: Novel insights into tumorigenesis and

prognosis of endometrial cancer through systematic investigation

and validation on mitophagy-related signature. Hum Cell.

36:1548–1563. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhao MM, Wang B, Huang WX, Zhang L, Peng R

and Wang C: Verteporfin suppressed mitophagy via PINK1/parkin

pathway in endometrial cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 14:1935–1946. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology, and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y and Guo R:

Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: A novel approach to reversing drug

resistance. Mol Cancer. 21:472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang

D: Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 17:2054–2081.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Pandrangi SL, Chittineedi P, Chikati R,

Lingareddy JR, Nagoor M and Ponnada SK: Role of dietary iron

revisited: In metabolism, ferroptosis and pathophysiology of

cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 12:974–985. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Gao W, Wang X, Zhou Y, Wang X and Yu Y:

Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor

immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Dai E, Chen X, Linkermann A, Jiang X, Kang

R, Kagan VE, Bayir H, Yang WS, Garcia-Saez AJ, Ioannou MS, et al: A

guideline on the molecular ecosystem regulating ferroptosis. Nat

Cell Biol. 26:1447–1547. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C

and Li B: Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: opportunities and

challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 12:342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Zhang M, Zhang T, Song C, Qu J, Gu Y, Liu

S, Li H, Xiao W, Kong L, Sun Y and Lv W: Guizhi Fuling Capsule

ameliorates endometrial hyperplasia through promoting

p62-Keap1-NRF2-mediated ferroptosis. J Ethnopharmacol.

274:1140642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

López-Janeiro Á, Ruz-Caracuel I,

Ramón-Patino JL, De Los Ríos V, Villalba Esparza M, Berjón A,

Yébenes L, Hernández A, Masetto I, Kadioglu E, et al: Proteomic

analysis of Low-grade, early-stage endometrial carcinoma reveals

new dysregulated pathways associated with cell death and cell

signaling. Cancers (Basel). 13:7942021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Tang S and Chen L: The recent advancements

of ferroptosis of gynecological cancer. Cancer Cell Int.

24:3512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Huang JY and Yu HN: The role of the Nrf2

pathway in inhibiting ferroptosis in kidney disease and its future

prospects. Pathol Res Pract. 272:1560842025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius

E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A,

et al: Acsl4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular

lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 13:91–98. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Rosenblum SL: Inflammation, dysregulated

iron metabolism, and cardiovascular disease. Front Aging.

4:11241782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Wei S, Yu Z, Shi R, An L, Zhang Q, Zhang

Q, Zhang T, Zhang J and Wang H: GPX4 suppresses ferroptosis to

promote malignant progression of endometrial carcinoma via

transcriptional activation by ELK1. BMC Cancer. 22:8812022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Hirayama T, Nagata Y, Nishida M, Matsuo M,

Kobayashi S, Yoneda A, Kanetaka K, Udono H and Eguchi S: Metformin

prevents peritoneal dissemination via Immune-suppressive cells in

the tumor microenvironment. Anticancer Res. 39:4699–4709. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhang X, Han S and Yang B:

Metformin-induced RBMS3 expression enhances ferroptosis and

suppresses ovarian cancer progression. Reprod Biol. 25:1009682025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

van den Heerik ASVM, Horeweg N, de Boer

SM, Bosse T and Creutzberg CL: Adjuvant therapy for endometrial

cancer in the era of molecular classification: Radiotherapy,

chemoradiation and novel targets for therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

31:594–604. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Liu Q, Zhao Y, Zhou H and Chen C:

Ferroptosis: Challenges and opportunities for nanomaterials in

cancer therapy. Regen Biomater. 10:rbad0042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Sotomayor-Flores C, Rivera-Mejías P,

Vásquez-Trincado C, López-Crisosto C, Morales PE, Pennanen C,

Polakovicova I, Aliaga-Tobar V, García L, Roa JC, et al:

Angiotensin-(1–9) prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by controlling

mitochondrial dynamics via miR-129-3p/PKIA pathway. Cell Death

Differ. 27:2586–2604. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB, et al: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by

GPX4. Cell. 156:317–33. 20141 View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM,

Gelino SR, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor

R, et al: Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein

kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 331:456–461.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zhao L, Zhou X, Xie F and Zhang L, Yan H,

Huang J, Zhang C, Zhou F, Chen J and Zhang L: Ferroptosis in cancer

and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 42:88–116. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Cormio A, Musicco C, Gasparre G, Cormio G,

Pesce V, Sardanelli AM and Gadaleta MN: Increase in proteins

involved in mitochondrial fission, mitophagy, proteolysis and

antioxidant response in type I endometrial cancer as an adaptive

response to respiratory complex I deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 491:85–90. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Liu C, Li Z, Li B, Liu W, Zhang S, Qiu K

and Zhu W: Relationship between ferroptosis and mitophagy in

cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury: A mini-review. PeerJ.

11:e149522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Bi Y, Liu S, Qin X, Abudureyimu M, Wang L,

Zou R, Ajoolabady A, Zhang W, Peng H, Ren J and Zhang Y: FUNDC1

interacts with GPx4 to govern hepatic ferroptosis and fibrotic

injury through a mitophagy-dependent manner. J Adv Res. 55:45–60.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Wilhelm LP, Zapata-Muñoz J, Villarejo-Zori

B, Pellegrin S, Freire CM, Toye AM, Boya P and Ganley IG:

BNIP3L/NIX regulates both mitophagy and pexophagy. EMBO J.

41:e1111152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Yamashita SI, Sugiura Y, Matsuoka Y, Maeda

R, Inoue K, Furukawa K, Fukuda T, Chan DC and Kanki T: Mitophagy

mediated by BNIP3 and NIX protects against ferroptosis by

downregulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell Death

Differ. 31:651–661. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Yang CH, Almomen A, Wee YS, Jarboe EA,

Peterson CM and Janát-Amsbury MM: An estrogen-induced endometrial

hyperplasia mouse model recapitulating human disease progression

and genetic aberrations. Cancer Med. 4:1039–1050. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Fan R, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wei L and Zheng W:

Mechanism of progestin resistance in endometrial precancer/cancer

through Nrf2-survivin pathway. Am J Transl Res. 9:1483–1491.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Yi J, Zhu J, Wu J, Thompson CB and Jiang

X: Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses

ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

117:31189–31197. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Álvarez-Garcia V, Tawil Y, Wise HM and

Leslie NR: Mechanisms of PTEN loss in cancer: It's all about

diversity. Semin Cancer Biol. 59:66–79. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Nero C, Ciccarone F, Pietragalla A and

Scambia G: PTEN and gynecological cancers. Cancers. 11:14582019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Wang P, Zhang XP, Liu F and Wang W:

Progressive Deactivation of Hydroxylases Controls Hypoxia-Inducible

Factor-1α-Coordinated Cellular Adaptation to Graded Hypoxia.

Research. 8:06512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Wang P, Dai X, Jiang W, Li Y and Wei W:

RBR E3 ubiquitin ligases in tumorigenesis. Semin Cancer Biol.

67:131–144. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Zhang HL, Hu BX, Li ZL, Du T, Shan JL, Ye

ZP, Peng XD, Li X, Huang Y, Zhu XY, et al: PKCβII phosphorylates

ACSL4 to amplify lipid peroxidation to induce ferroptosis. Nature

Cell Biol. 24:88–98. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Jaramillo MC and Zhang DD: The emerging

role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev.

27:2179–2191. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Yang B, Hu M, Fu Y, Sun D, Zheng W, Liao

H, Zhang Z and Chen X: LASS2 mediates Nrf2-driven progestin

resistance in endometrial cancer. Am J Transl Res. 13:1280–1289.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Read AD, Bentley RET, Archer SL and

Dunham-Snary KJ: Mitochondrial iron-sulfur clusters: Structure,

function, and an emerging role in vascular biology. Redox Biol.

47:1021642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Luo J, Zhang X, Liang Z, Zhuang W, Jiang

M, Ma M, Peng S, Huang S, Qiao G and Chen Q: ISCU-p53 axis

orchestrates macrophage polarization to dictate immunotherapy

response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis.

16:4622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Yang H, Yao X, Liu Y, Shen X, Li M and Luo

Z: Ferroptosis Nanomedicine: Clinical Challenges and Opportunities

for Modulating Tumor Metabolic and Immunological Landscape. ACS

Nano. 17:15328–15353. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Glorieux C, Liu S, Trachootham D and Huang

P: Targeting ROS in cancer: Rationale and strategies. Nature

Reviews Drug Discovery. 23:583–606. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

McKee CA, Polino AJ, King MW and Musiek

ES: Circadian clock protein BMAL1 broadly influences autophagy and

endolysosomal function in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e22205511202025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Makovec T: Cisplatin and beyond: Molecular

mechanisms of action and drug resistance development in cancer

chemotherapy. Radiol Oncol. 53:148–1458. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Dasari S and Tchounwou PB: Cisplatin in

cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol.

740:364–378. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Mauro-Lizcano M, Sotgia F and Lisanti MP:

Mitophagy and cancer: Role of BNIP3/BNIP3L as energetic drivers of

stemness features, ATP production, proliferation, and cell

migration. Aging (Albany NY). 16:9334–9349. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Li K, Xu K, He Y, Yang Y, Tan M, Mao Y,

Zou Y, Feng Q, Luo Z and Cai K: Oxygen Self-generating nanoreactor

mediated ferroptosis activation and immunotherapy in

Triple-negative breast cancer. ACS Nano. 17:4667–4687. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Xu L, Fang Q, Miao Y, Xu M, Wang Y, Sun L

and Jia X: The role of CCR2 in prognosis of patients with

endometrial cancer and tumor microenvironment remodeling.

Bioengineered. 12:3467–3484. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Nizami ZN, Aburawi HE, Semlali A, Muhammad

K and Iratni R: Oxidative stress inducers in cancer therapy:

Preclinical and clinical evidence. Antioxidants. 12:11592023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Li J, Jia Y Chen, Ding Y Xuan, Bai J, Cao

F and Li F: The crosstalk between ferroptosis and mitochondrial

dynamic regulatory networks. Int J Biol Sci. 19:2756–2771. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

CD8+ T cells and fatty acids orchestrate

tumor ferroptosis and immunity via ACSL4-PMC [Internet], . [cited

2025 Sept 10]. Available from. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9007863/

|

|

122

|

Huo K, Yang Y, Yang T, Zhang W and Shao J:

Identification of drug targets and agents associated with

ferroptosis-related osteoporosis through integrated network

pharmacology and molecular docking technology. Curr Pharm Des.

30:1103–1114. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Hu G, Yuan Z and Wang J: Autophagy

inhibition and ferroptosis activation during atherosclerosis:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α inhibitor PX-478 alleviates

atherosclerosis by inducing autophagy and suppressing ferroptosis

in macrophages. Biomed Pharmacother. 161:1143332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Bhatt V, Lan T, Wang W, Kong J, Lopes EC,

Wang J, Khayati K, Raju A, Rangel M, Lopez E, et al: Inhibition of

autophagy and MEK promotes ferroptosis in Lkb1-deficient

Kras-driven lung tumors. Cell Death Dis. 14:612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Crouigneau R, Li YF, Auxillos J,

Goncalves-Alves E, Marie R, Sandelin A and Pedersen SF: Mimicking

and analyzing the tumor microenvironment. Cell Rep Methods.

4:1008662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Early JO, Menon D, Wyse CA,

Cervantes-Silva MP, Zaslona Z, Carroll RG, Palsson-McDermott EM,

Angiari S, Ryan DG, Corcoran SE, et al: Circadian clock protein

BMAL1 regulates IL-1β in macrophages via NRF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 115:E8460–E8468. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Wang Z, Ge S, Liao T, Yuan M, Qian W, Chen

Q, Liang W, Cheng X, Zhou Q, Ju Z, et al: Integrative single-cell

metabolomics and phenotypic profiling reveals metabolic

heterogeneity of cellular oxidation and senescence. Nat Commun.

16:27402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M,

da Silva MC, Ingold I, Grocin AG, da Silva TNX, Panzilius E, Scheel

CH, et al: FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis

suppressor. Nature. 575:693–698. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks J, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts in parallel to GPX4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Pekovic-Vaughan V, Gibbs J, Yoshitane H,

Yang N, Pathiranage D, Guo B, Sagami A, Taguchi K, Bechtold D,

Loudon A, et al: The circadian clock regulates rhythmic activation

of the NRF2/glutathione-mediated antioxidant defense pathway to

modulate pulmonary fibrosis. Genes Dev. 28:548–560. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee

H, Koppula P, Wu S, Zhuang L, Fang B, et al: DHODH-mediated

ferroptosis defense is a targetable vulnerability in cancer.

Nature. 593:586–590. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Oh M, Jang SY, Lee JY, Kim JW, Jung Y, Kim

J, Seo J, Han TS, Jang E, Son HY, et al: The lipoprotein-associated

phospholipase A2 inhibitor Darapladib sensitises cancer cells to

ferroptosis by remodelling lipid metabolism. Nat Commun.

14:57282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|