Introduction

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare malignant tumor

that accounts for ~1% of all breast cancer cases (1). Globally, the incidence of MBC is

relatively low, with GLOBOCAN 2020 data reporting an annual rate of

0.5–1.0 cases per 100,000 individuals (2). The mortality rate of MBC in 2021 was

0.34 cases per 100,000 individuals [95% uncertainty interval (UI),

0.23–0.41], which was markedly lower compared with the rate of

female breast cancer (FBC) at 14.55 cases per 100,000 individuals

(95% UI, 13.45–15.56) (3). Due to

its rarity, MBC is underrepresented in breast cancer trials,

resulting in a lack of prospective or randomized data specific to

men. Therefore, treatment decisions are typically extrapolated from

data derived from female patients (4), whose adverse event (AE) profiles often

lack characteristics specific to men. Therefore, notable emphasis

should be placed on including male patients in clinical trials of

breast cancer and reporting AE data.

Primary treatment modalities for MBC include

surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted

therapy and immunotherapy (IO) (5,6).

Mastectomy has traditionally been considered the standard surgical

approach for early-stage MBC due to limited breast tissue in men

and the typical proximity of tumors to the nipple-areolar complex

(5). Since the majority of MBCs are

hormone receptor-positive, adjuvant endocrine therapy, primarily

tamoxifen, constitutes the cornerstone of treatment for hormone

receptor-positive disease. Radiotherapy is considered to provide

clinically notable benefits for male patients with early-stage and

locally advanced disease. Furthermore, the management of advanced

MBC typically aligns with established approaches used for female

patients, including chemotherapy, HER2-targeted agents, IO and

poly(ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors (5,6).

HER2 is expressed in tumor tissues and cells of

various advanced malignant solid tumors, such as breast (7), gastric (8), pancreatic (9), lung (10), colorectal (11) and ovarian (12) cancer. In breast cancer, the

incidence of HER2 gene amplification and upregulation can reach

15–20% (13). The HER2 receptor is

recognized as an effective therapeutic target for tumors with HER2

amplification or upregulation. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)

combine the high specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the

potent antitumor activity of cytotoxic payloads. The targeted

delivery mechanism of ADCs enhances safety profiles, making them a

prominent research focus in oncology therapeutics (14). Although several HER2-directed ADCs,

such as trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) (15), trastuzumab deruxtecan (16) and disitamab vedotin (17), have been approved for clinical use,

subcutaneous (SC) formulations of HER2-directed ADCs remain in the

emerging phase of clinical investigation, with limited reported

data on associated AEs.

In January 2025, the Phase I Unit of Fudan

University Shanghai Cancer Center (Shanghai, China) initiated a

phase I/II clinical trial evaluating the safety, tolerability,

pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and antitumor activity of JSKN033

(18). JSKN033 is a fixed-dose

combination for SC injection that comprises JSKN003, a biparatopic

HER2-directed ADC, and envafolimab, a programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) inhibitor approved by the National Medical Products

Administration of China (18). In

the dose-escalation phase, patients received SC JSKN033 across

three doses (5.6, 6.7 and 8.4 mg/kg, once weekly) following a

modified 3+3 design. Safety evaluations were based on

treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) and dose-limiting toxicities to

assess the primary endpoints of safety and tolerability. The

dose-limiting toxicity assessment period was 21 days. Investigators

evaluated tumor response every 6 weeks using the Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1; RECIST) (19) and performed tumor imaging

assessments with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI). Preliminary study data indicated that the most

common TRAE of JSKN033 was mild to moderate (grade 1 and 2)

injection site reactions (90.9%). This was followed by diarrhea

(54.5%), nausea (45.5%), increased aspartate aminotransferase

(27.3%), decreased appetite (27.3%), increased alanine

aminotransferase (18.2%) and maculo-papular rash (18.2%). No grade

3 or higher TRAEs or serious AEs were observed and no TRAEs led to

treatment discontinuation (18).

During the same month of JSKN033 initiation, a male patient with

breast cancer was enrolled and subsequently developed evident

systemic and injection-site adverse reactions after treatment,

including fatigue, diarrhea and localized injection-site

manifestations of pruritus, pain, cutaneous depression and SC

induration.

The development of SC formulations for anticancer

agents has gained increasing attention in oncological therapeutics

due to their notable convenience and improved treatment experience.

Notable examples include subcutaneous formulations of the

monoclonal antibodies trastuzumab (20), the fixed-dose combination of

pertuzumab and trastuzumab (21),

and the PD-L1 inhibitor envafolimab (22). JSKN033 is the first global SC

coformulation consisting of an ADC and an immune checkpoint

inhibitor, and to the best of our knowledge, research on the

underlying mechanisms of JSKN033-associated AEs and their clinical

management is limited (18,23). The present case report focuses on

JSKN033-associated AEs, which may contribute to the understanding

of the toxicity profiles of SC-administered ADCs and the

optimization of management strategies. Furthermore, as the present

case includes a male patient with breast cancer, it may provide

distinctive data and insights that are potentially valuable for

future research.

Case report

A 38-year-old man underwent a right-sided simple

mastectomy at Changzhou Wujin People's Hospital (Changzhou, China)

in March 2023 after self-identifying a 7×7-cm mass in the right

breast. Postoperative pathology [based on histopathological slides

from Changzhou Wujin People's Hospital and subsequent consultation

with the Department of Pathology of Fudan University Shanghai

Cancer Center (Shanghai, China)] revealed grade 3 invasive ductal

carcinoma according to the Nottingham histological grading system

(24) [estrogen receptor (ER), 90%;

progesterone receptor, 90%; HER2, 2+; and Ki-67, 40%). The

immunohistochemistry and H&E images are not available as the

original histopathological slides were processed and diagnosed by

Changzhou Wujin People's Hospital (data not shown). In April 2023,

the patient received a modified radical mastectomy followed by

adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide

[1.5 g intravenously (IV) every 3 weeks] plus epirubicin (180 mg IV

every 3 weeks) and 4 cycles of trastuzumab (1,120 mg IV every 3

weeks), pertuzumab (840 mg IV every 3 weeks) and docetaxel (202.4

mg IV every 3 weeks). The patient subsequently received adjuvant

radiotherapy in November 2023 (total dose of 4,256 cGy in 16

fractions at 266 cGy/fraction), followed by 2 cycles of T-DM1 (500

mg IV every 3 weeks), which was discontinued due to disease

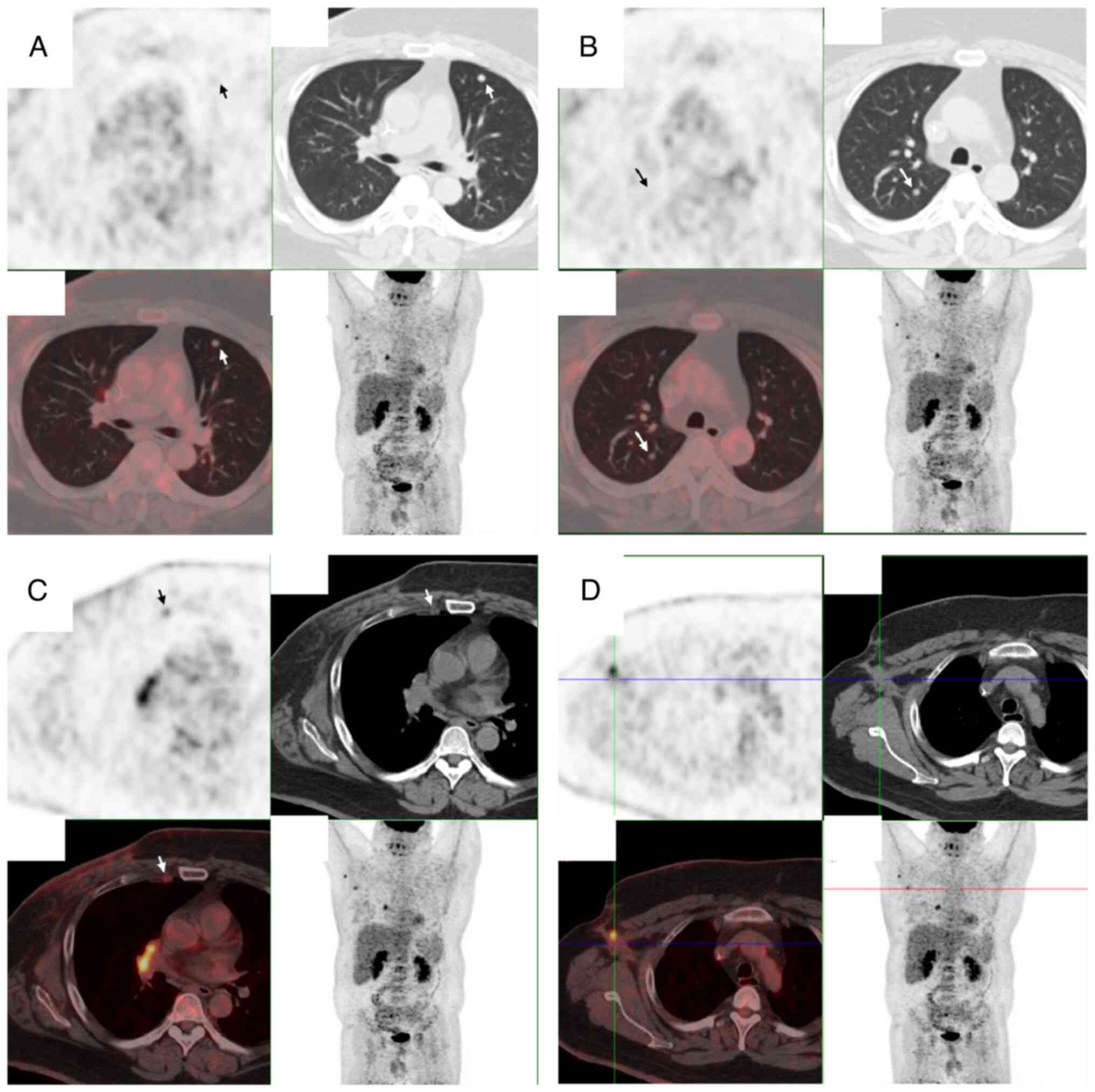

progression. In December 2023, positron emission tomography-CT

revealed disease recurrence in the chest wall with multiple

pulmonary and lymph node metastases (Fig. 1). The patient was subsequently

enrolled in two Phase 1 clinical trials [SMP-656 (CTR20233290) and

ASKG-915 (CTR20232767)] from January to June 2024 but was withdrawn

from both trials due to progressive disease.

The patient was enrolled in the JSKN033 phase I/II

clinical trial (CTR20244896) at the Phase I Clinical Trial Center

of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center in January 2025. The

patient had a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and

hypertension, with concomitant medications, including metformin

(0.5 g twice daily, orally), protamine human insulin mixed

injection (30 IU once daily, administered subcutaneously in the

bilateral upper arms), amlodipine besylate (5 mg once daily,

orally), valsartan (100 mg three times daily, orally) and

arotinolol (10 mg three times daily, orally). No history of drug or

disinfectant allergies was reported. Physical examination revealed

no ecchymoses, erythema or SC nodules on the skin or mucous

membranes. Baseline target lesion selection was performed in

January 2025, identifying a left pulmonary nodule as the target

lesion, with a sum of the longest diameters measuring 17.3 mm.

JSKN033 [180 mg (1 ml)/vial] consisted of 80 mg of JSKN003 and 100

mg of envafolimab. The JSKN033 treatment regimen included weekly SC

administration. The dose administered to the patient was calculated

as 560 mg (3.1 ml) per administration on the basis of body weight,

which was divided into two SC injections (2+1.1 ml) due to protocol

recommendations (maximum 2 ml per injection) (25,26),

which meant that the patient received two SC injections per weekly

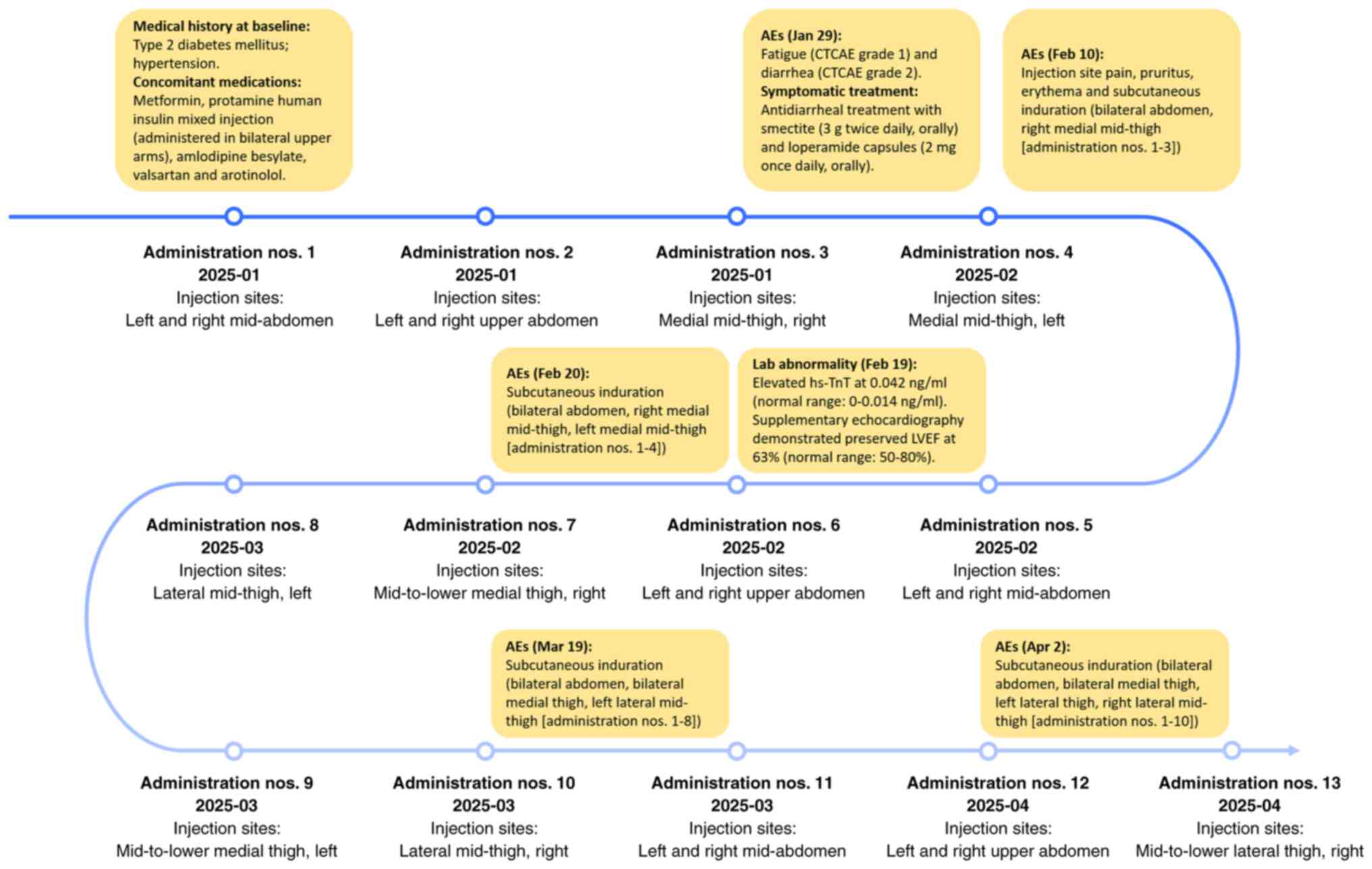

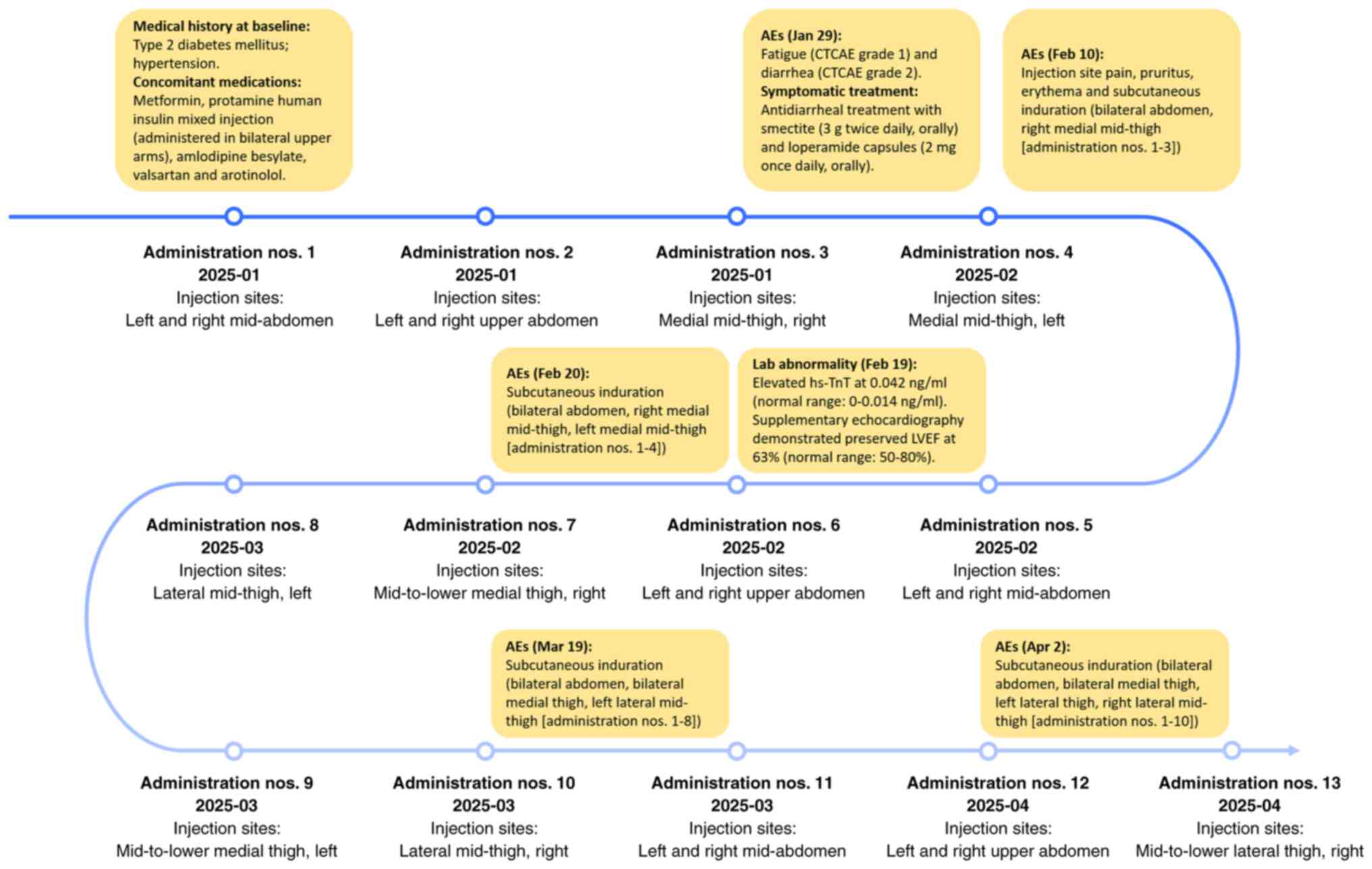

dose. The first dose of JSKN033 was administered in January 2025.

As of April 2025, the patient had received 13 weekly doses,

totaling 26 SC injections over the 13-week period. On the basis of

the protocol recommendation that the optimal injection sites are

the abdomen and thighs (25,26),

the injection sites were selected in the following order: i)

Left/right mid-abdomen, ii) left/right upper abdomen, iii)

left/right lower abdomen, iv) medial mid-to-lower left/right thigh;

and v) lateral mid-to-lower left/right thigh. New injection sites

were selected for each administration and no single site was

injected twice consecutively; when repeated injections in the same

anatomical region were necessary due to practical constraints,

subsequent injections were administered ≥2.5 cm from previous

sites. Please refer to Fig. 2 for a

detailed illustration of the injection site rotation strategy. With

the protocol recommended injection rate of ≤0.06 ml/sec, the

minimum injection time of each administration was calculated as 52

sec. Postinjection observation was required for 1 h before

discharge.

| Figure 2.Timeline of treatment interventions

and AEs. Each administration required two separate subcutaneous

injections (2+1.1 ml), with injection sites within the same

anatomical region spaced ≥2.5 cm apart (administration nos. 3, 4,

7, 8, 9, 10 and 13). CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events; AEs, adverse events; LVEF, left ventricular ejection

fraction; hs-TnT, high-sensitivity troponin T. |

AEs were classified and graded according to the

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0

(27). The patient developed

systemic reactions 2 weeks after administration (January 2025),

presenting with fatigue (CTCAE grade 1) and diarrhea (watery

stools, 4–5 episodes/day; CTCAE grade 2). The patient demonstrated

no evidence of anemia or thyroid dysfunction at baseline or during

treatment. Therefore, these factors were excluded as potential

causes of fatigue. The diarrhea improved to 1–2 episodes/day (CTCAE

grade 1) following antidiarrheal treatment with smectite (3 g twice

daily, orally) and loperamide capsules (2 mg once daily, orally).

Furthermore, 5 weeks after administration (February 2025), the

patient exhibited an elevated high-sensitivity troponin T

concentration of 0.042 ng/ml (normal range, 0–0.014 ng/ml).

Supplementary echocardiography demonstrated a preserved left

ventricular ejection fraction of 63% (normal range, 50–80%). No

elevated liver enzymes or hematological toxicity was observed

during the treatment course. The patient self-reported

postinjection localized tension-type pain, quantified as 2 on a

0–10 numeric rating scale, where 0 indicates no pain and 10

represents the worst possible pain (28). Mild pruritus (CTCAE grade 1) at the

injection site was noted and worsened with thermal stimulation.

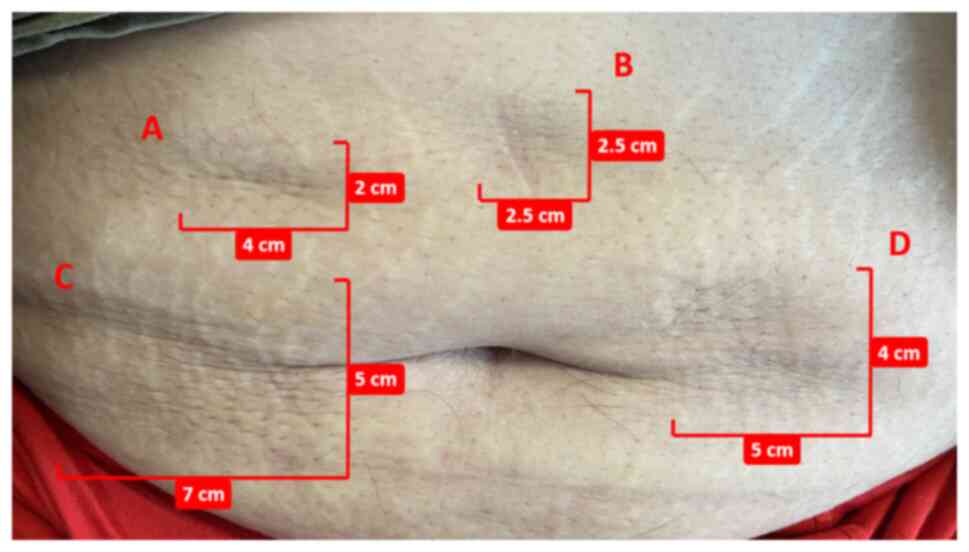

Furthermore, the patient experienced local erythema (Fig. 3) without swelling at ~1 week, which

typically resolved within 2–3 weeks, resulting in post-inflammatory

hyperpigmentation. Persistent cutaneous changes included

injection-site depression (Fig. 4),

enlarged pores, deepened skin folds and SC induration resistance to

resolution. All cutaneous abnormalities presented in Figs. 3 and 4 occurred following single injections at

each site. The overall treatment process and progression of AEs are

shown in Fig. 2.

The patient was followed up weekly, and tumor

assessments were performed using CT or MRI every 6 weeks (±7 days).

At the 12-week follow-up (April 2025), the therapeutic response was

assessed as a partial response according to RECIST (version 1.1),

with the target left pulmonary nodule demonstrating a sum of the

longest diameters of 9.8 mm (baseline, 17.3 mm). All observed AEs

were mild and clinically manageable. Treatment continuation was

approved, with ongoing monitoring.

Discussion

JSKN033 is a fixed-dose combination of JSKN003 and

envafolimab (18). JSKN003 is a

biparatopic HER2-directed ADC composed of a recombinant humanized

anti-HER2 bispecific antibody, a linker and a topoisomerase I

inhibitor payload. The JSKN003 mechanism of action includes

specific recognition and binding to HER2 on tumor cell surfaces,

followed by HER2-mediated internalization, intracellular release of

the topoisomerase I inhibitor payload, induction of DNA damage and

subsequent apoptosis, thereby exerting antitumor effects (29). The combination of ADCs with IO may

provide potential synergistic effects to enhance clinical benefits,

representing a promising direction for future ADC development

(30). The currently approved

HER2-targeted ADCs (for example, T-DM1, disitamab vedotin and

trastuzumab deruxtecan) (17,31)

are all administered via intravenous (IV) infusion. Furthermore,

both ADC-IO combinations and SC ADC formulations remain under

clinical investigation (18,32).

Based on current reports of HER2-targeted ADCs, the

commonly observed AEs include elevated liver enzymes, fatigue,

decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, interstitial lung

disease/non-infectious pneumonitis, loss of appetite, nausea,

vomiting, diarrhea, hematological toxicity and infusion-associated

reactions (14,33–35).

The toxicity profile of ADCs is primarily associated with target

selection and payload characteristics (33). In the present case, the systemic

reactions of the patient manifested mainly as diarrhea and fatigue,

which may be attributed to cross-reactivity of the HER2-targeted

ADC with gastrointestinal HER2 receptors during tumor antigen

binding (36) and the payload, a

topoisomerase I inhibitor, which can induce early-onset and

delayed-onset diarrhea (37). With

respect to non-infectious etiologies, mild diarrhea typically

responds to loperamide supplemented by fluid/electrolyte

replacement when necessary (38).

Overall, these systemic reactions remain mild and manageable

through symptomatic treatment and lifestyle modifications. From

both theoretical and clinical data, the systemic adverse reactions

associated with SC administration are generally consistent with

those associated with the IV route (in terms of classification

rather than specific incidence rates) (14,18,33–35).

Compared with IV administration, SC delivery avoids

infusion-associated reactions but may induce injection site

reactions (ISRs). In accordance with the preliminary clinical data

of JSKN033, 11 patients were enrolled in the dose-escalation phase

in Australia, 10 of whom (90.9%) experienced ISRs following

administration (18), all of which

were mild in severity, with no reported cases requiring dose

reduction or treatment discontinuation. To the best of our

knowledge, current research on the mechanisms underlying ISRs

associated with SC administration of HER2-targeted ADCs remains

limited. Potential contributing factors to these local reactions

may include the following: i) Drug-associated factors: The

cytotoxic payloads of ADCs are likely the primary causes of ISRs

(23). The slow absorption process

and prolonged local retention of large-molecule ADCs can lead to

sustained local drug exposure at the injection site. Furthermore,

enhanced immune cell uptake of the antibody-conjugated payload may

exacerbate immune system and skin inflammation (23). Furthermore, envafolimab in JSKN033

is the first approved global SC-administered PD-L1 inhibitor and is

marketed in China. Current data indicates that envafolimab induces

ISRs with no more than a 5% incidence rate, potentially associated

with immune system activation and inflammatory responses, possibly

contributing to the ISR presentation of the patient (39). ii) Injection technique factors: The

stability of the linker markedly influences payload release, where

premature release of the cytotoxic payload may result in off-target

toxicity (33). Improper handling

practices such as excessive heating or agitation before injection

could compromise linkers, thereby impairing therapeutic efficacy

and exacerbating AEs. Furthermore, injection parameters, including

volume, injection rate, technique and repeated dosing at the same

site, contribute to ISRs (40).

iii) Patient-specific factors: The present patient had a baseline

body weight of 120 kg, with a BMI >37 kg/m2. Previous

studies have indicated that pro-inflammatory immune cells and

adipocytes secrete inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and

leptin), creating a chronic low-grade inflammatory state in obesity

that likely exacerbates injection-site inflammatory responses and

induration formation (41–43). Furthermore, obesity affects skin

barrier integrity, which gets translated into clinical xerosis.

Obesity also causes altered collagen structure and impaired wound

healing due to decreased mechanical strength (44). These factors may have collectively

contributed to the development of ISRs in the present patient.

Furthermore, MBC is usually ER+. A large

multicenter retrospective cohort study demonstrated strong ER

expression in >90% of MBC cases (45). The gene encoding ERα acts as a key

regulator of several key hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes,

including cytochrome P450 families, exerting broad effects on drug

metabolism (46). Therefore, the

high ER-positive profile characteristic of MBC may also represent

one of the factors influencing drug metabolism and the development

of AEs. It has been reported that certain sex-based differences

exist in the risk of AEs between male and female patients with

cancer receiving IO, targeted therapy or chemotherapy (47). Women are at a notably greater risk

of severe symptomatic AEs across multiple treatment domains,

including patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

and targeted therapies with kinase inhibitors (47). This disparity may be associated with

factors such as differences in sex hormone levels affecting drug

metabolism and sex variations in pharmacokinetics, pharmacogenomics

and treatment adherence (47).

JSKN033 is a combination of JSKN003 (a biparatopic HER2-directed

ADC) and envafolimab (a PD-L1 inhibitor) (18); therefore, its treatment-associated

AEs may also exhibit sex-specific variations. However, as JSKN033

is still in the clinical trial stage, robust statistical evidence

regarding sex differences in its toxicity profile remains

unavailable. Future research on sex-specific differences in

JSKN033-associated AEs would be valuable to inform optimized dosing

strategies for both male and female patients.

SC administration improves patient experience,

treatment adherence and quality of life by markedly reducing

administration time, increasing treatment convenience, decreasing

hospitalization frequency, lowering both temporal and economic

health care burdens, and eliminating complications associated with

venipuncture (48). Therefore, the

development of SC formulations for anticancer agents has gained

increasing attention in oncological therapeutics. However, compared

with IV administration, the localized reactions associated with SC

injection may pose a limiting factor for its widespread adoption.

Therefore, proper injection techniques and skin protection measures

should be implemented when SC ADCs are administered to minimize or

prevent these localized reactions.

Excessive injection rates, and improper injection

angles or needle gauges may exacerbate ISRs (40,49).

Therefore, standardized SC administration is essential for

prevention. Since current research on the SC administration of ADCs

is limited, the present case report offers recommendations for

combining the pharmacological mechanisms of ADCs with those of

established SC injection techniques for biologics such as

monoclonal antibodies (40,49,50).

i) Medication preparation: After removal from 2–8°C refrigeration,

allow 30 min to let the medication reach room temperature prior to

injection, while avoiding improper heating or vigorous agitation to

maintain pharmaceutical stability. ii) Needle: SC injections

typically employ short (4–8 mm) and thin-wall needles with small

gauges (25–27 G) and sharp tips to minimize pain. iii) Injection

volume: The amount of drug injected should not be >2.0 ml per

injection site to prevent injection pain, leakage and tissue

distortion. iv) Injection site: Adipose-rich areas such as the

abdomen and thighs should be chosen for injection, ensuring that

the injection site exhibits no erythema, damage, ecchymosis,

scarring, induration or hyperpigmentation. v) Rotation techniques:

Injection sites should be rotated systematically to reduce

irritation and ISRs, with subsequent injection administered ≥2.5 cm

from previous sites. vi) Injection angle/technique: The

non-dominant hand should be used to elevate a skin fold and the

dominant hand should be used to insert the needle at a 30–40°

angle, which can be adjusted on the basis of SC fat thickness to

achieve optimal deposition. vii) Injection rate: The injection rate

should not exceed 0.06 ml/sec to ensure patient comfort and proper

drug dispersion. viii) Post-injection monitoring: A minimum of 1 h

of observation is needed after injection to confirm patient safety

before discharge.

Current clinical data indicates that ISRs are the

most frequently reported AEs associated with SC-administered

JSKN033, primarily manifesting as localized erythema, swelling,

pain and pruritus (18). Most ISRs

are mild in severity and typically resolve without intervention or

can be effectively managed with physician-directed antihistamine

therapy when necessary. For localized skin temperature elevation or

erythema, cold compresses or topical corticosteroids may be applied

(50). Analgesics should be

considered for patients with notable pain. Warm compresses and

physiotherapy may help alleviate induration. For severe cutaneous

reactions such as ulceration or necrosis, immediate treatment

discontinuation or regimen adjustment is warranted.

Although ISRs are usually mild and rarely classified

as severe AEs, they may have a notable effect on patient

satisfaction with treatment and even contribute to treatment

discontinuation (51). Adequate

patient education on the following aspects can help improve

treatment experience. Before injection, patients should be informed

about the procedure, precautions, common AEs and corresponding

management measures. During the injection, any discomfort, such as

pain at the injection site or systemic/local allergic reactions

(for example, fever, chills, rash, dizziness or chest tightness),

should be reported to medical staff immediately. After the

injection, patients should be instructed to apply proper pressure

to the injection site to minimize bleeding. The patients should

also be educated on self-identifying AEs and promptly reporting

them to medical staff, keeping the injection site clean and dry,

avoiding water exposure for ≥24 h and bathing only after the

injection site has fully healed. Furthermore, at 24 h

post-injection, patients should not apply heat, undergo

physiotherapy or vigorously massage the area in order to prevent

capillary rupture and bleeding (52).

Due to study limitations and the personal preference

of the patient, the present case report was unable to obtain

additional imaging data (for example, ultrasound and MRI scans) or

histological data regarding the AEs of the patient. The results

described in the study are based on pathology reports rather than

retrievable image files. Therefore, there is a lack of

histopathological or biopsy evidence to further support diagnostic

evaluation. Furthermore, during the current therapeutic response

assessment, HER2 fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis

was not performed, which represents a limitation of the present

case report. JSKN033 remains in the emerging phase of clinical

investigation. The AE mechanisms of JSKN033 and their management

are still being investigated, with little existing research

reported, to the best of our knowledge. Based on the present case

report and the pharmacological mechanisms of JSKN033, potential AE

mechanisms and management strategies were analyzed. However, these

analyses had limitations. Notably, the small sample size inherent

in a case report design limits the generalizability of the study

findings and precludes definitive statistical conclusions.

Furthermore, as the present case had only completed 13 weeks of

administration at the time of manuscript preparation, longer-term

follow-up outcomes were not yet available.

ADCs are currently a key research focus in oncology

therapeutics. SC administration has demonstrated notable potential

to improve the treatment experience and quality of life of patients

due to its enhanced convenience. However, SC ADC formulations

remain in the investigational stage and further study is warranted

to fully characterize their AE profiles, and the mechanisms,

prevention and management strategies of these AEs. The present

study reported a case of systemic and localized AEs associated with

SC ADC administration, aiming to provide data and potential

insights for associated research in this field. JSKN033 remains in

the emerging phase of clinical investigation, including the

underlying mechanisms and management of its associated AEs, with,

to the best of our knowledge, limited existing research. Based on

the present case report and the underlying pharmacological

mechanisms of JSKN033, the potential underlying mechanisms and

management strategies of JSKN033-associated AEs were analyzed.

However, these analyses had limitations. Future studies may collect

more comprehensive and long-term evidence to potentially improve

the mechanistic understanding and clinical management of AEs

associated with SC-administered ADCs to guide targeted management

strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

RY wrote the original draft, devised the

methodology, conducted the investigation and conceptualized the

present case report. JZ advised on patient treatment, analyzed

patient data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

YW reviewed and edited the manuscript, devised the methodology and

conceptualized the present case report. RY and YW confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present case report was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (Shanghai,

China; approval no. 2409305-22).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the case report, including any

potentially identifiable images or data.

Competing interests

The present case report has been published with the

written permission of the sponsor of JSKN033 (Jiangsu Alphamab

Biopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd.) from Clinical Trials ID no.

NCT06226766 and Chinese Clinical Trial Registry ID no. CTR20244896.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence

of any commercial or financial relationships that could be

construed as a potential competing interest.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhao L, Cheng H, He D, Zhang Y, Chai Y,

Song A and Sun G: Decoding male breast cancer: Epidemiological

insights, cutting-edge treatments, and future perspectives. Discov

Oncol. 16:3602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

An B, Che M, Liu Y, Yang X and Li Z:

Analysis and comparison of the burden of male breast cancer:

differences between the global, China, India, and the United

States. BMC Public Health. 25:22052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ter-Zakarian A, Agelidis A and Jaloudi M:

Male breast cancer: Evaluating the current landscape of diagnosis

and treatment. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 17:567–572.

2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hou J, Feng H, Zhang M, Wang D and Fan H:

Hotspots and future trends of male breast cancer: A global

perspective. Clin Transl Oncol. Aug 21–2025.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ross JS, Slodkowska EA, Symmans WF,

Pusztai L, Ravdin PM and Hortobagyi GN: The HER-2 receptor and

breast cancer: Ten years of targeted anti-HER-2 therapy and

personalized medicine. Oncologist. 14:320–368. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gravalos C and Jimeno A: HER2 in gastric

cancer: A new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann

Oncol. 19:1523–1529. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Harder J, Ihorst G, Heinemann V, Hofheinz

R, Moehler M, Buechler P, Kloeppel G, Röcken C, Bitzer M, Boeck S,

et al: Multicentre phase II trial of trastuzumab and capecitabine

in patients with HER2 overexpressing metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Br J Cancer. 106:1033–1038. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yoshizawa A, Sumiyoshi S, Sonobe M,

Kobayashi M, Uehara T, Fujimoto M, Tsuruyama T, Date H and Haga H:

HER2 status in lung adenocarcinoma: A comparison of

immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH),

dual-ISH, and gene mutations. Lung Cancer. 85:373–378. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Blok EJ, Kuppen PJ, van Leeuwen JE and

Sier CF: Cytoplasmic overexpression of HER2: A key factor in

colorectal cancer. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 7:41–51. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Verri E, Guglielmini P, Puntoni M,

Perdelli L, Papadia A, Lorenzi P, Rubagotti A, Ragni N and Boccardo

F: HER2/neu oncoprotein overexpression in epithelial ovarian

cancer: Evaluation of its prevalence and prognostic significance.

Clinical study. Oncology. 68:154–161. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Waks AG and Winer EP: Breast cancer

treatment: A review. JAMA. 321:288–300. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wei H, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Zou Y, Zhou L, Qin X

and Jiang Q: Is ADC a rising star in solid tumor? An umbrella

review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Cancer.

25:3802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wedam S, Fashoyin-Aje L, Gao X, Bloomquist

E, Tang S, Sridhara R, Goldberg KB, King-Kallimanis BL, Theoret MR,

Ibrahim A, et al: FDA approval summary: Ado-trastuzumab emtansine

for the adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive early breast cancer.

Clin Cancer Res. 26:4180–4185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Dilawari A, Zhang H, Shah M, Gao X, Fiero

M, Bhatnagar V, Pierce W, Mixter B, Pazdur R and Amiri-Kordestani

L: US Food and Drug Administration approval summary: trastuzumab

deruxtecan for the treatment of adult patients with hormone

receptor-positive, unresectable or metastatic human epidermal

growth factor receptor 2-low or human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2-ultralow breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 43:2942–2951.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Deeks ED: Disitamab vedotin: First

approval. Drugs. 81:1929–1935. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lemech C, Wei J, O'Neill S, et al: 1496

JSKN033, an innovative subcutaneous-injected fixed-dose combination

(FDC) of biparatopic anti-HER2 antibody drug conjugate (ADC) and

PD-L1 inhibitor in advanced solid tumor. J Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Nov 5–2024.(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

19

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ismael G, Hegg R, Muehlbauer S, Heinzmann

D, Lum B, Kim SB, Pienkowski T, Lichinitser M, Semiglazov V,

Melichar B and Jackisch C: Subcutaneous versus intravenous

administration of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab in patients with

HER2-positive, clinical stage I–III breast cancer (HannaH study): A

phase 3, open-label, multicenter, randomized trial. Lancet Oncol.

13:869–878. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tan AR, Im SA, Mattar A, Colomer R,

Stroyakovskii D, Nowecki Z, De Laurentiis M, Pierga JY, Jung KH,

Schem C, et al: Fixed-dose combination of pertuzumab and

trastuzumab for subcutaneous injection plus chemotherapy in

HER2-positive early breast cancer (FeDeriCa): A randomized,

open-label, multicenter, non-inferiority, phase 3 study. Lancet

Oncol. 22:85–97. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Markham A: Envafolimab: First approval.

Drugs. 82:235–240. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chang HP, Le HK and Shah DK:

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibody-drug conjugates

administered via subcutaneous and intratumoral routes.

Pharmaceutics. 15:11322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Elston CW and Ellis IO: Pathological

prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological

grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with

long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 19:403–410. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Boudreau A: Practical considerations for

the integration of subcutaneous targeted therapies into the

oncology clinic. Can Oncol Nurs J. 29:267–270. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Davis JD, Bravo Padros M, Conrado DJ,

Ganguly S, Guan X, Hassan HE, Hazra A, Irvin SC, Jayachandran P,

Kosloski MP, et al: Subcutaneous administration of monoclonal

antibodies: Pharmacology, delivery, immunogenicity, and learnings

from applications to clinical development. Clin Pharmacol Ther.

115:422–439. 2024. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

National Cancer Institute. Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, . National

Cancer Institute website. Updated November 27 and 2017. May

26–2025Available from. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm

|

|

28

|

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth

JL and Poole MR: Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain

intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

Pain. 94:149–158. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yang Q and Liu Y: Technical, preclinical,

and clinical developments of Fc-glycan-specific antibody-drug

conjugates. RSC Med Chem. 16:50–62. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Joubert N, Beck A, Dumontet C and

Denevault-Sabourin C: Antibody-drug conjugates: The last decade.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 13:2452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Liang Y, Zhang P, Li F, Lai H, Qi T and

Wang Y: Advances in the study of marketed antibody-drug conjugates

(ADCs) for the treatment of breast cancer. Front Pharmacol.

14:13325392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hobson AD, Xu J, Marvin CC, McPherson MJ,

Hollmann M, Gattner M, Dzeyk K, Fettis MM, Bischoff AK, Wang L, et

al: Optimization of drug-linker to enable long-term storage of

antibody-drug conjugate for subcutaneous dosing. J Med Chem.

66:9161–9173. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ballestin P, López de Sá A, Diaz-Tejeiro

C, Paniagua-Herranz L, Sanvicente A, López-Cade I, Pérez-Segura P,

Alonso-Moreno C, Nieto-Jiménez C and Ocaña A: Understanding the

toxicity profile of approved ADCs. Pharmaceutics. 17:2582025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tan HN, Morcillo MA, Lopez J, Minchom A,

Sharp A, Paschalis A, Silva-Fortes G, Raobaikady B and Banerji U:

Treatment-related adverse events of antibody drug-conjugates in

clinical trials. J Hematol Oncol. 18:712025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Schettini F, Nucera S, Pascual T,

Martínez-Sáez O, Sánchez-Bayona R, Conte B, Buono G, Lambertini M,

Punie K, Cejalvo JM, et al: Efficacy and safety of antibody-drug

conjugates in pretreated HER2-low metastatic breast cancer: A

systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev.

132:1028652025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Al-Dasooqi N, Bowen JM, Gibson RJ,

Sullivan T, Lees J and Keefe DM: Trastuzumab induces

gastrointestinal side effects in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer

patients. Invest New Drugs. 27:173–178. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Paulik A, Grim J and Filip S: Predictors

of irinotecan toxicity and efficacy in treatment of metastatic

colorectal cancer. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 55:153–159. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Manna M, Brabant M, Greene R, Chamberlain

MD, Kumar A, Alimohamed N and Brezden-Masley C: Canadian expert

recommendations on safety overview and toxicity management

strategies for sacituzumab govitecan based on use in metastatic

triple-negative breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 31:5694–5708. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cui C, Wang J, Wang C, Xu T, Qin L, Xiao

S, Gong J, Song L and Liu D: Model-informed drug development of

envafolimab, a subcutaneously injectable PD-L1 antibody, in

patients with advanced solid tumors. Oncologist. 29:e1189–e1200.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

St Clair-Jones A, Prignano F, Goncalves J,

Paul M and Sewerin P: Understanding and minimising injection-site

pain following subcutaneous administration of biologics: A

narrative review. Rheumatol Ther. 7:741–757. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chin SH, Huang WL, Akter S and Binks M:

Obesity and pain: A systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond).

44:969–979. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hildebrandt X, Ibrahim M and Peltzer N:

Cell death and inflammation during obesity: ‘Know my methods,

WAT(son)’. Cell Death Differ. 30:279–292. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Erstad BL and Barletta JF: Implications of

obesity for drug administration and absorption from subcutaneous

and intramuscular injections: A primer. Am J Health Syst Pharm.

79:1236–1244. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hirt PA, Castillo DE, Yosipovitch G and

Keri JE: Skin changes in the obese patient. J Am Acad Dermatol.

81:1037–1057. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Cardoso F, Bartlett J, Slaets L, van

Deurzen CHM, van Leeuwen-Stok E, Porter P, Linderholm B, Hedenfalk

I, Schröder C, Martens J, et al: Characterization of male breast

cancer: Results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG international

male breast cancer program. Ann Oncol. 29:405–417. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang D, Lu R, Rempala G and Sadee W:

Ligand-free estrogen receptor α (ESR1) as master regulator for the

expression of CYP3A4 and other cytochrome P450 enzymes in the human

liver. Mol Pharmacol. 96:430–440. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Unger JM, Vaidya R, Albain KS, LeBlanc M,

Minasian LM, Gotay CC, Henry NL, Fisch MJ, Lee SM, Blanke CD and

Hershman DL: Sex differences in risk of severe adverse events in

patients receiving immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or chemotherapy

in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 40:1474–1486. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Otoya I, Valdiviezo N, Morante Z, Calle C,

Ferreyra Y, Huarcaya-Chombo N, Polo-Mendoza G, Castañeda C,

Vidaurre T, Neciosup SP, et al: Subcutaneous trastuzumab: an

observational study of safety and tolerability in patients with

early HER2-positive breast cancer. Int J Breast Cancer.

2024:95517102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhi L, Liu D and Shameem M: Injection site

reactions of biologics and mitigation strategies. AAPS Open.

11:52025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Wang LY, Qin HY and Lu YH: Expert

consensus on breast cancer targeted therapy with subcutaneous

injection. Chin J Nurs. 60:43–47. 2025.

|

|

51

|

Kim PJ, Lansang RP and Vender R: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of injection site reactions in

randomized-controlled trials of biologic injections. J Cutan Med

Surg. 27:358–367. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Cancer Clinical Pharmacy Committee of

China Anti-cancer Association, Case Management Committee of China

Anti-cancer Association, . Expert consensus on the standardized

construction of ‘Convenient Injection Centers’ for anti-tumor

subcutaneous preparations. Chin J Mod Nurs. 30:1121–1130. 2024.

|