Introduction

Mandibular reconstruction following segmental

resection, often performed in the context of oral and maxillofacial

malignancies, is one of the most challenging procedures in head and

neck oncology. The accuracy of reconstruction critically affects

postoperative oral function, facial symmetry, and overall quality

of life. Due to both cosmetic and functional considerations,

including the maintenance of occlusion, mandibular reconstruction

requires precise alignment and preservation of the spatial

relationship between the divided bone fragments pre- and

postoperatively. After segmental mandibular resection, the bone may

be replaced with a graft, and various bone sources have been used,

including the fibula, iliac crest, scapula, and radius of the

forearm. When using bone replacements, sculpting them precisely to

fit the mandibular defect intraoperatively and aligning them

optimally to enhance bone approximation and promote bone healing is

crucial (1–4).

Traditionally, mandibular reconstruction has relied

on freehand techniques, which are highly dependent on the surgeon's

experience and intraoperative judgment. These methods often result

in variability in outcomes and prolonged surgical time.

Computer-assisted surgery (CAS) for mandibular reconstruction has

been increasingly adopted in clinical practice. CAS encompasses a

surgical approach and a set of methods that use computer technology

for surgical planning, guidance, or execution of interventions. CAS

in mandibular reconstruction was first implemented clinically by

determining the extent of mandibular resection, the shape of the

mandibular reconstruction metal plate, and the morphology and

position of the graft bone through preoperative computer

simulation, as described by Hirsch et al in 2009 (1). The resulting three-dimensional

(3D)-printed osteotomy guides and preshaped mandibular

reconstruction plates allow precisely planned surgery to be

executed with high accuracy and greater efficiency in the operating

room. These advancements reduce surgical duration and facilitate

technique optimization (2,5–15).

Currently, outsourced mandibular reconstruction CAS

systems, such as TruMatch® (DePuy Synthes, MA, USA), are

widely used (16). Introduced in

Japan in 2022, the TruMatch system has been applied in numerous

cases at our facility. However, these systems require long

preparation times, typically one month, and incur substantial

costs, which may limit their accessibility, especially in urgent

oncologic cases. Additionally, communication with external

engineers during planning may not fully capture the surgeon's

intent, and the hospital receives only the final product, with

limited control over the design process (17). To overcome these challenges, we

developed an in-house CAS system utilizing widely available 3D

printing and surgical simulation software. This system allows for

rapid planning, greater customization, and reduced costs, making it

a potentially viable alternative to commercial solutions. Despite

the growing interest in in-house CAS, few studies have directly

compared its accuracy with that of outsourced systems or

conventional methods.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate and compare

the accuracy of mandibular reconstruction using three approaches:

conventional surgery (non-CAS), outsourced CAS (TruMatch), and an

in-house CAS system. Given that the majority of cases involved

segmental mandibulectomy for malignant tumors, particularly oral

cancer, the study also sought to assess the feasibility and

precision of CAS-based reconstruction in oncologic settings.

Postoperative outcomes were analyzed using 3D model overlay

techniques to determine whether in-house CAS could provide accuracy

comparable to that of outsourced systems and support broader

clinical application in cancer-related mandibular

reconstruction.

Materials and methods

Patients

All patients who underwent mandibular reconstruction

surgery at our department (Center for Oral Cancer, The University

of Osaka Dental Hospital, Suita, Japan) between April 2018 and

January 2025 were included in this study. The cases were

categorized into three groups based on the surgical technique and

time period:

Non-CAS group: Cases treated before March 2021,

prior to the introduction of CAS at our institution. These cases

were managed using conventional freehand techniques with

miniplates. In cases where the mandibular segment would have been

too small following resection, segmental reconstruction was not

feasible, and a hemimandibulectomy was performed instead.

Outsourced CAS (TruMatch) group: Cases treated after

March 2021, where sufficient preparation time (≥1 month) and budget

permitted the use of outsourced CAS. TruMatch was not used in

urgent cases or when financial constraints precluded

outsourcing.

In-house CAS group: Cases treated after August 2022,

where outsourced CAS was not feasible due to time or cost

limitations. These cases underwent preoperative simulation and

guide design using Vincent and 3Shape software within our

institution. Standard reconstruction plates were manually contoured

to fit the simulated mandibular model and positioned

intraoperatively using custom-designed devices. The scapular graft

was adjusted and fixed in the same manner as in the TruMatch

group.

However, we excluded cases where one mandibular

condyle was completely resected and thus could not be analyzed,

cases where the reconstruction plate was temporarily positioned

directly on the mandible prior to resection during surgery, and

cases where pre- and postoperative computed tomography (CT) scans

were unavailable for comparison. All surgeries were performed by a

consistent surgical team specializing in oral and maxillofacial

oncology. The principal surgeons were board-certified oral and

maxillofacial surgeons with over 10 years of clinical experience in

oncologic head and neck surgery. The core members of this team

remained unchanged throughout the study period, thereby minimizing

variability related to surgeon experience. Of the 59 cases of

segmental mandibular resection performed during this period, 32

were included in this study. This retrospective study was approved

by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Osaka

Graduate School of Dentistry (approval number: R6-E35). Although

all patients were treated at The University of Osaka Dental

Hospital, ethics approval was obtained from the university-level

committee in accordance with institutional policy. At The

University of Osaka Graduate School of Dentistry, retrospective

clinical studies involving comparative analysis of multiple cases,

including those using opt-out consent, require formal review and

approval by the Graduate School of Dentistry Research Ethics

Committee to ensure consistent ethical oversight across affiliated

institutions. Patient data were collected from electronic medical

records and imaging archives maintained at The University of Osaka

Dental Hospital. In accordance with ethical guidelines, informed

consent was obtained from all patients using an opt-out method,

whereby information about the study was disclosed publicly and

patients were given the opportunity to decline participation. The

University of Osaka Dental Hospital is officially affiliated with

The University of Osaka Graduate School of Dentistry.

Virtual surgical planning and 3D

fabrication of surgical devices

All patients underwent CT scans of the mandible.

Similarly, patients planned for scapular grafting underwent

scapular CT imaging. The CT scans were saved as Digital Imaging and

Communications in Medicine files, segmented, and converted into a

virtual 3D model in Stereolithography (STL) format. For cases using

the TruMatch (DePuy Synthes, MA, USA) system, the order was placed

at least 1 month prior to surgery and discussed with the company

technician during preoperative planning. For the in-house CAS

system, a virtual mandibulectomy and reconstruction of the planned

mandibular defect were performed using Vincent software (Fujifilm,

Japan), which allowed for interactive 3D modeling of the mandible

and donor bone. Cases with severely deformed mandibles due to

tumors, fractures, or segmental defects were modeled based on the

contralateral, unaffected side using the mirror image principle

(8,12,18).

The cutting guide and bone/plate-positioning devices were designed

using Vincent software and the 3Shape Dental System (3Shape,

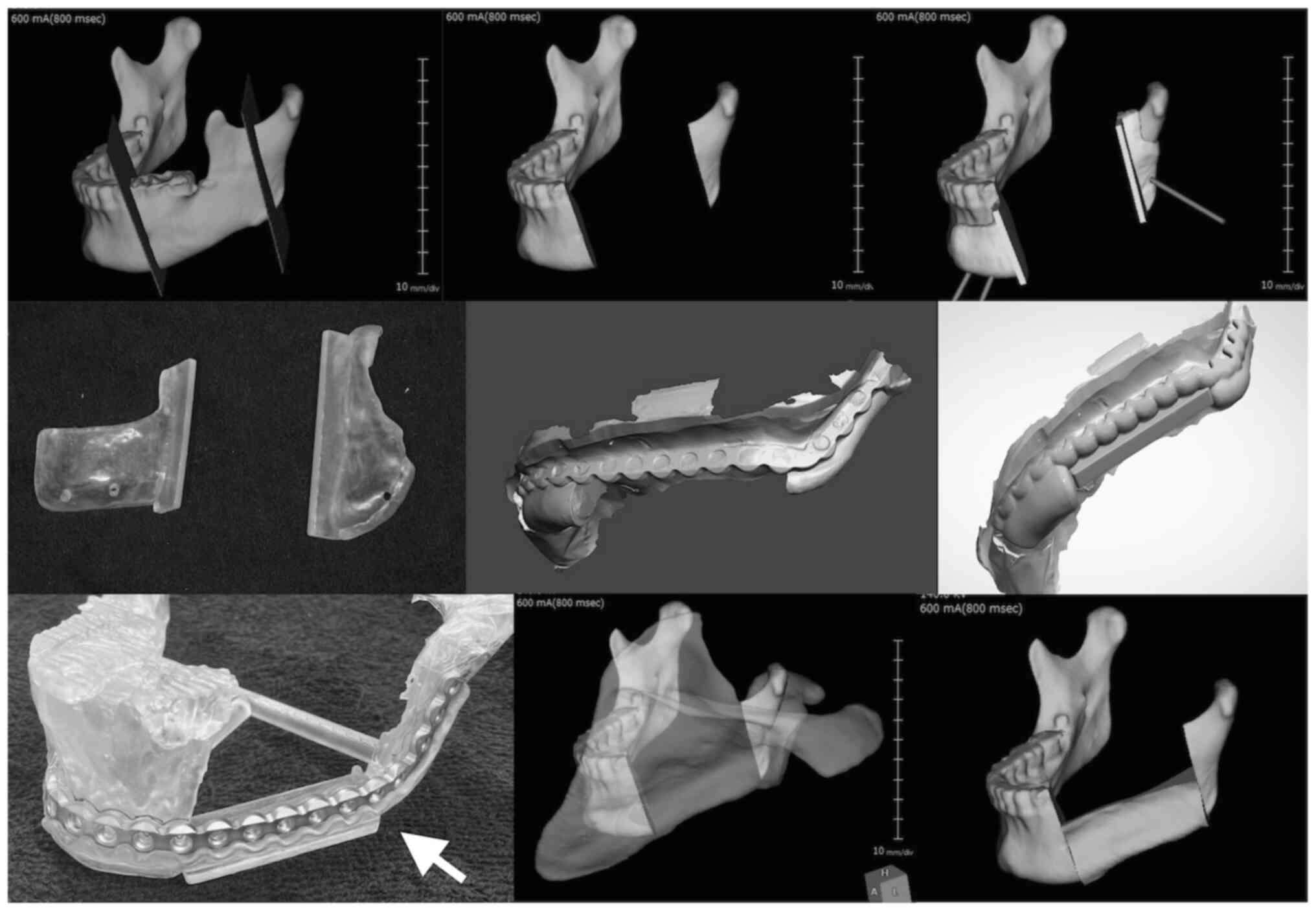

Denmark) (Fig. 1). The 3D models of

the mandible, bone/plate-positioning devices, and cutting-guide

devices were fabricated in photopolymer resin using a 3D printer

(Formlabs Inc., MA, USA). A 3D-printed model of the reconstructed

mandible was created. Preoperatively, a 2.6-mm locking titanium

mandibular reconstruction plate was manually contoured to fit the

3D-reconstructed mandibular model.

Vincent software, originally developed as a

diagnostic imaging viewer and analysis tool for radiology, is

primarily used to evaluate CT and magnetic resonance imaging data

and does not include surgical simulation functions by default. In

this study, we adapted the Vincent software for virtual

mandibulectomy and 3D modeling by utilizing its segmentation and

visualization capabilities. The 3Shape Dental System, primarily

intended for designing dental prostheses such as crowns, bridges,

custom impression trays, and complete or partial dentures, was

repurposed in our workflow. Specifically, we employed its CAD

modules to design bone and plate positioning devices for mandibular

reconstruction.

Surgical procedure

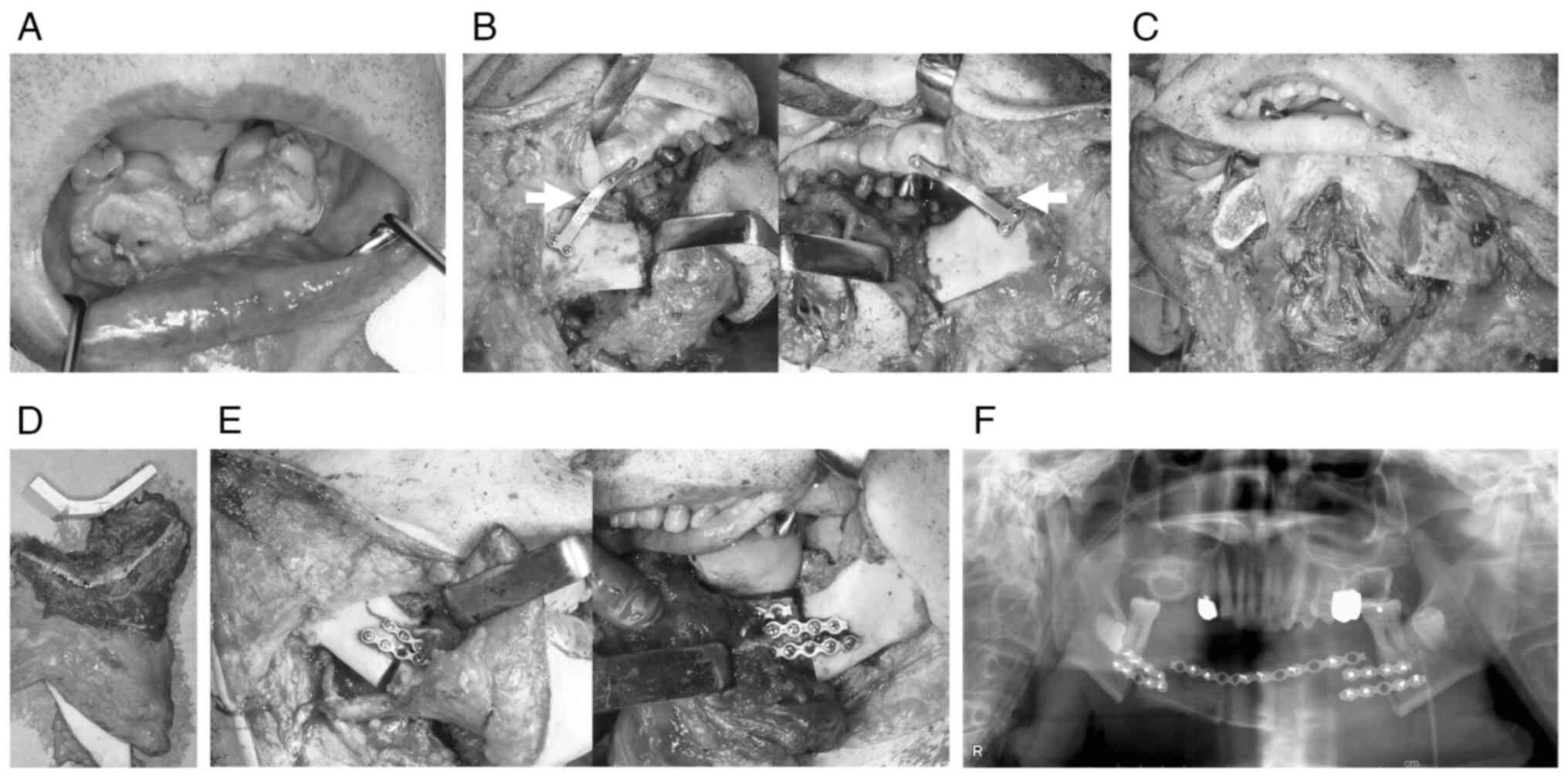

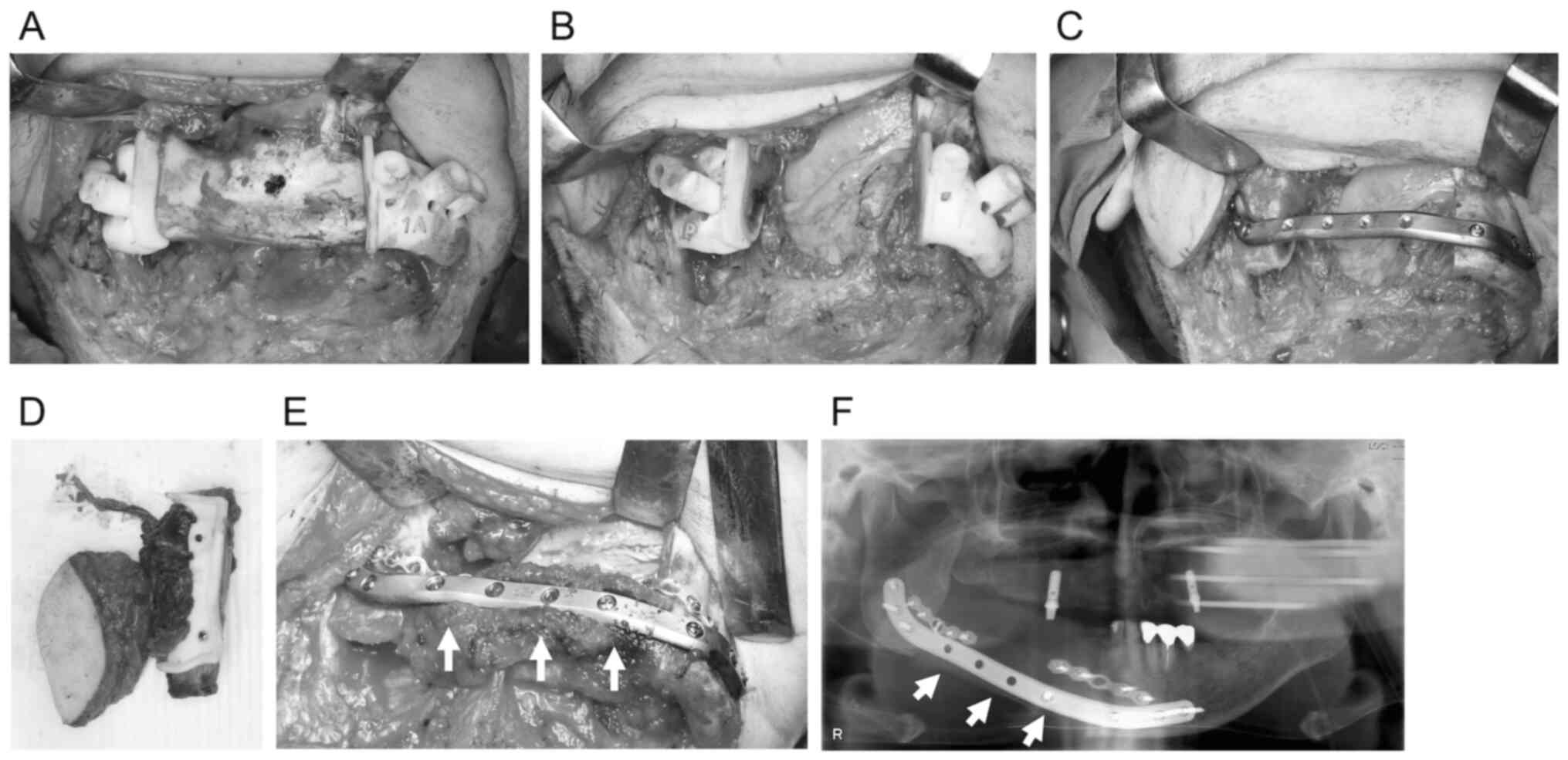

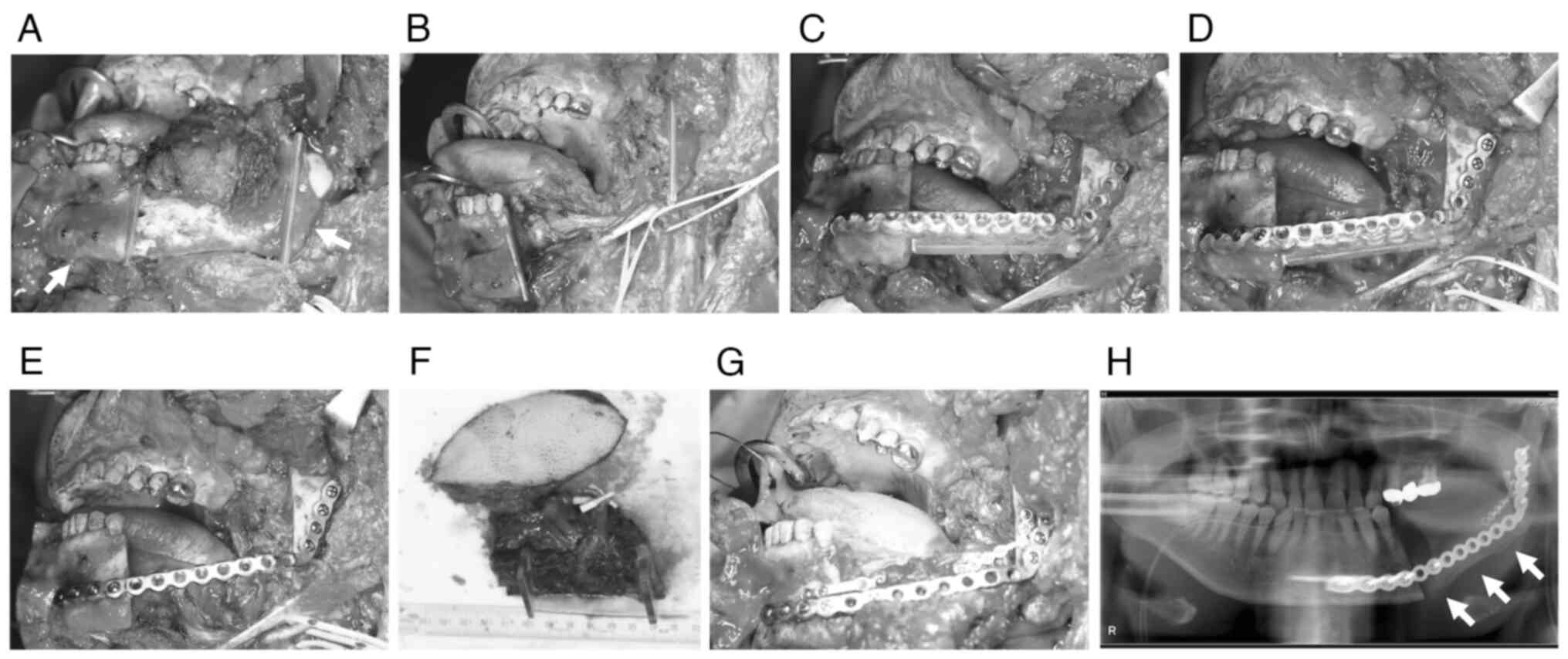

The surgeries were broadly divided into the

following three types: non-CAS, TruMatch, and in-house CAS

(Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig.

4). In non-CAS, intermaxillary fixation was used to maintain

the mandible's position after amputation, or a positioning plate

was used to fix it to the maxilla.

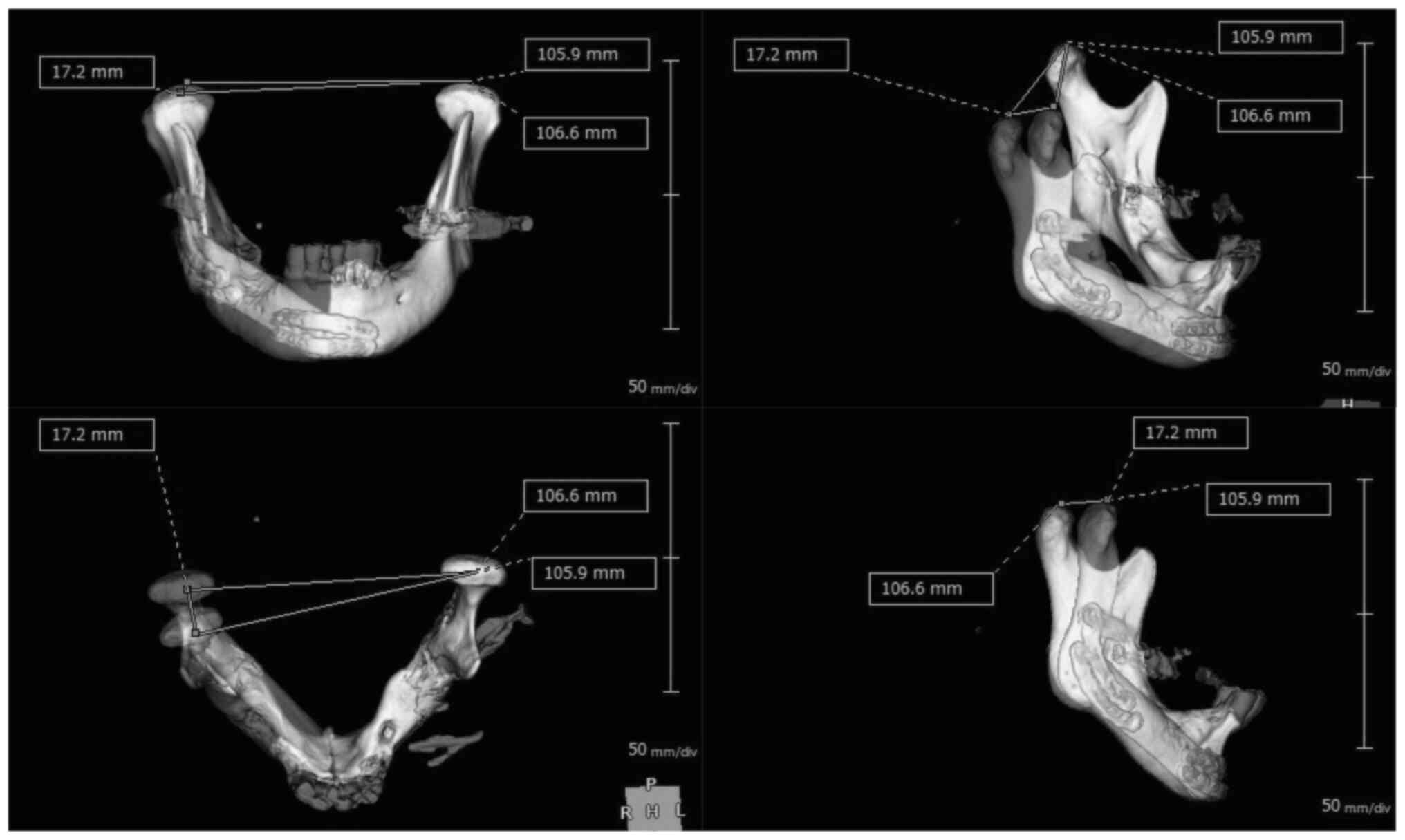

Accuracy analysis

Postoperative CT scans were taken approximately 1

month after surgery in all cases. These scans were used for

accuracy assessment through 3D model overlay analysis. The

postoperative CT scans were converted into 3D-STL models, which

were then superimposed on the preoperative 3D-STL models used for

virtual surgical planning, with the apex of the mandibular condyle

serving as the anchor point (software: Vincent, Fujifilm). The

discrepancy between the planned and actual mandibular

reconstruction was evaluated using two metrics: the intercondylar

distance (ICD, defined as the change in linear distance between the

apices of the bilateral mandibular condyles before and after

surgery, as described by Zhang et al) (19) and the 3D deviation distance (3DD,

defined as the spatial deviation of the apex of the affected

mandibular condyle between the planned and actual postoperative

positions) (Fig. 5). The analysis

was performed using Vincent software (Fujifilm, Japan) as follows:

A single anatomical landmark, the apex of the mandibular condyle,

was defined as the most superior point of the condyle on the

preoperative CT scan. Using Vincent's overlay function, the

postoperative condyle was superimposed onto the preoperative

condyle for each side separately, and the same apex point was

defined at the postoperative condyles. Next, using the healthy side

of the mandible (including the mandibular body, angle, and ramus)

as a reference, the preoperative and postoperative models were

overlaid again using Vincent's overlay function. Based on this 3D

overlay, the ICD was calculated as the difference in ICD before and

after surgery, and the 3DD was calculated as the spatial deviation

of the affected condyle apex.

Statistical analysis

To determine the appropriate statistical tests, we

assessed the normality of the ICD and 3DD datasets using the

Shapiro-Wilk test. Based on the results and the limited sample

size, comparisons among the three groups were conducted using the

Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test.

However, the comparison between two groups was analyzed using the

Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Between April 2018 and January 2025, a total of 32

cases were included, comprising eight non-CAS cases, 13 TruMatch

cases, and 11 in-house CAS cases (Table

I, Table II, Table III). The overall mean age of

patients was 67.8 years, with 13 females and 19 males. Of the 32

cases, 23 involved malignant tumors, eight involved benign tumors,

and three were cases of osteomyelitis. Regarding mandibular

reconstruction, five cases involved plate-only reconstruction,

eight cases involved plate + pectoralis major myocutaneous flap, 16

cases involved plate + scapular flap, two cases involved plate +

fibula flap, and one case involved plate + rectus abdominis

musculocutaneous flap (Table IV).

Based on the classification of mandibular defects by Boyd et

al (HCL classification) (20),

nine cases (28.1%) were classified as lateral-condyle (LC) or

lateral-condyle-lateral (LCL) mandibular defects. Furthermore,

almost all in-house CAS cases involved malignant tumors, and half

of these cases were classified as LC or LCL. In both TruMatch and

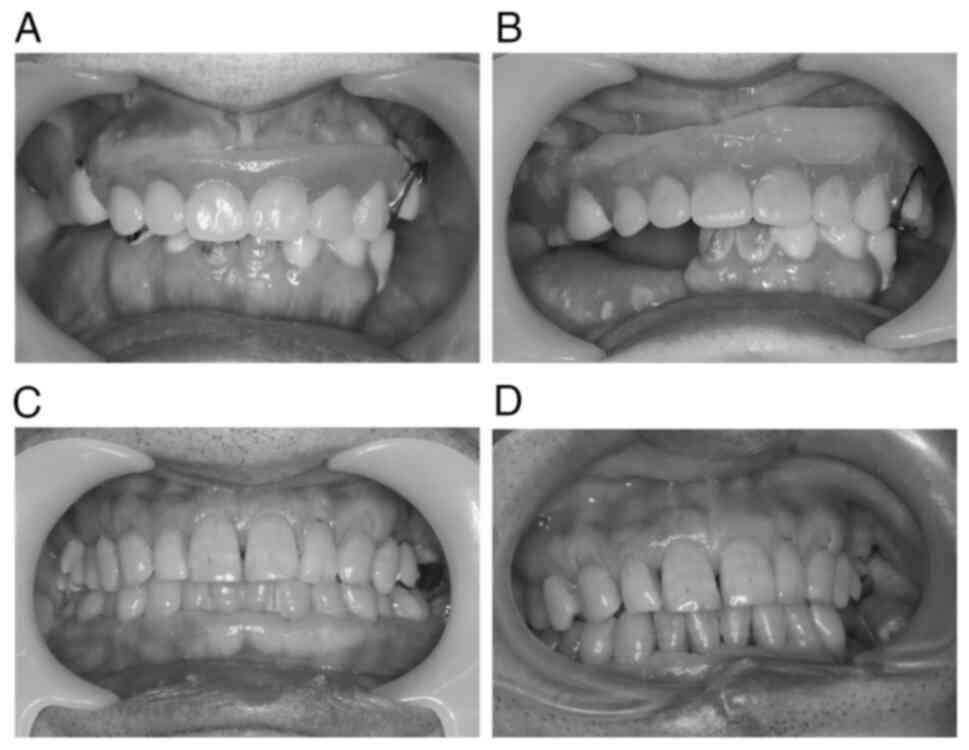

in-house CAS cases, the occlusal relationship was well maintained

pre- and postoperatively (Fig.

6).

| Table I.List of the non-computer-assisted

surgery system cases. |

Table I.

List of the non-computer-assisted

surgery system cases.

| No. | Age, years | Sex | Diagnosis | HCL

classification | Reconstruction |

|---|

| 1 | 69 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | Fibula flap,

mini-plate |

| 2 | 37 | F | Ossifying

fibroma | L | Scapula flap,

mini-plate |

| 3 | 77 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LCL | Scapula flap,

mini-plate |

| 4 | 52 | F | Ameloblastoma | L | Scapula flap,

mini-plate |

| 5 | 78 | M | Carcinoma of floor of

mouth | LCL | Scapula flap,

mini-plate |

| 6 | 75 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | Fibula flap,

mini-plate |

| 7 | 65 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | Scapula flap,

mini-plate |

| 8 | 74 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | Scapula flap,

mini-plate |

| Table II.List of the TruMatch system

cases. |

Table II.

List of the TruMatch system

cases.

| No. | Age, years | Sex | Diagnosis | HCL

classification | Reconstruction |

|---|

| 1 | 70 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 2 | 77 | M | Radiation

osteomyelitisa | L | TruMatch plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 3 | 49 | F | Ameloblastoma | L | TruMatch plate |

| 4 | 65 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 5 | 67 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | TruMatch plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 6 | 73 | M | Ameloblastoma | L | TruMatch plate |

| 7 | 71 | F | Ameloblastoma | L | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 8 | 56 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 9 | 65 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LCL | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 10 | 29 | F |

Cementoblastoma | L | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 11 | 83 | F | Medication-Related

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw | LCL | TruMatch plate |

| 12 | 63 | M | Postoperative

mandibular gingival carcinoma | L | TruMatch plate,

scapula flap |

| 13 | 77 | M | Postoperative

mandibular gingival carcinoma | L | TruMatch plate |

| Table III.List of the in-house

computer-assisted surgery system cases. |

Table III.

List of the in-house

computer-assisted surgery system cases.

| No. | Age, years | Sex | Diagnosis | HCL

classification | Reconstruction |

|---|

| 1 | 94 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LC | In-house plate |

| 2 | 86 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LCL | In-house plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 3 | 70 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | In-house plate,

scapula flap |

| 4 | 78 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | In-house plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 5 | 51 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LCL | In-house plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 6 | 80 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | In-house plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 7 | 67 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LCL | In-house plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 8 | 90 | F | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | LCL | In-house plate,

PMMC-flap |

| 9 | 58 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | In-house plate,

scapula flap |

| 10 | 55 | M | Carcinoma of

mandibular gingiva | L | In-house plate,

scapula flap |

| 11 | 70 | M | Radiation

osteomyelitisa | L | In-house plate,

RA-flap |

| Table IV.Patient characteristics. |

Table IV.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total | Non-CAS | TruMatch | In-house |

|---|

| Mean age,

years | 67.8 | 65.9 | 65.0 | 72.6 |

| Cases | 32 | 8 | 13 | 11 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

Female | 13 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

|

Male | 19 | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Reconstruction |

|

|

|

|

| Only

the plate | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| The

plate + PMMC-flap | 8 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| The

plate + scapula flap | 16 | 6 | 7 | 3 |

| The

plate + fibula flap | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| The

plate + RA-flap | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Primary

disease |

|

|

|

|

|

Malignant tumor | 23 | 6 | 7 | 10 |

| Benign

tumor | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

|

Osteomyelitis | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| HCL

classification |

|

|

|

|

| L | 23 | 6 | 11 | 6 |

| LC or

LCL | 9 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

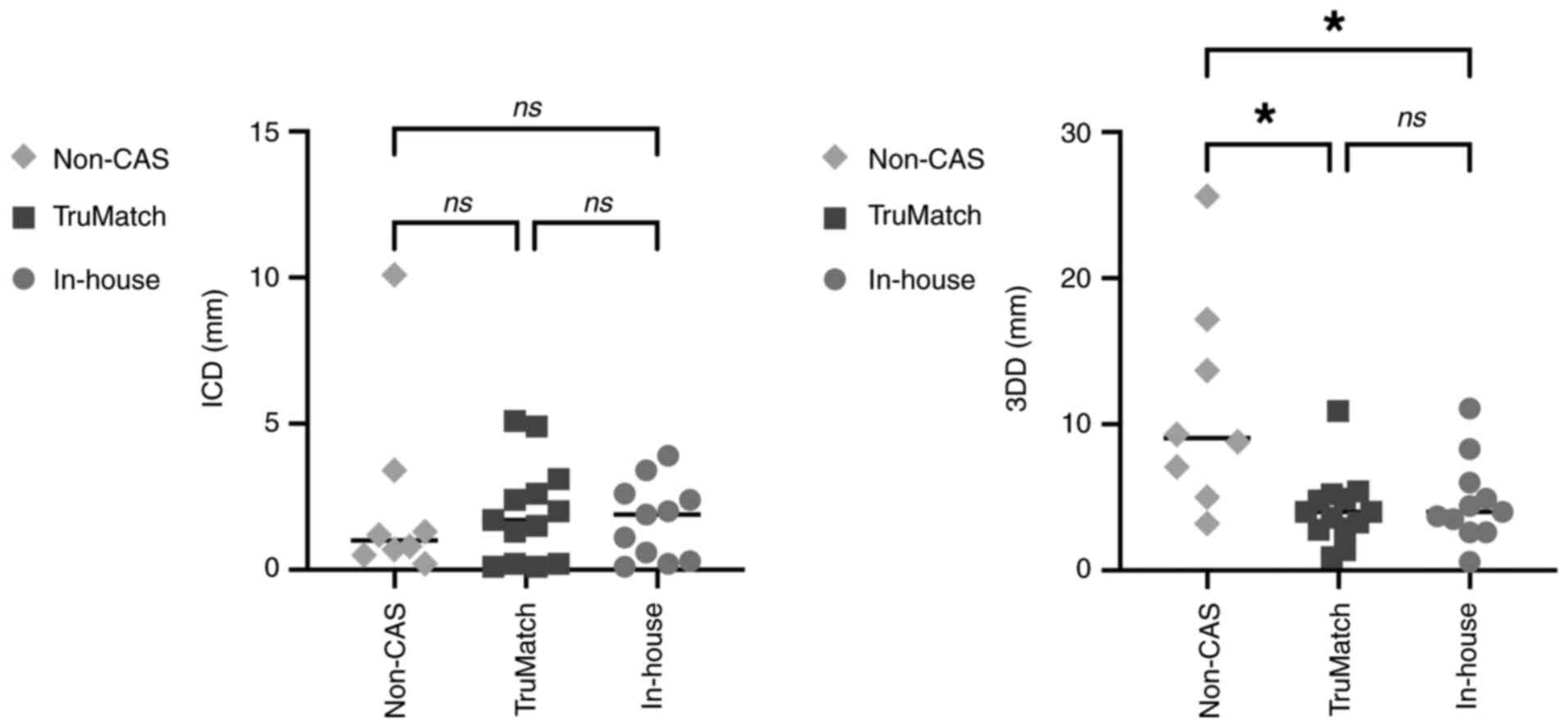

The results of the accuracy analysis using 3D model

overlay comparison are presented in Fig. 7. The ICD measurements were 2.3 mm on

average [standard deviation (SD): 3.3] in the non-CAS group, 1.9 mm

on average (SD: 1.7) in the TruMatch cases, and 1.8 mm on average

(SD: 1.3) in the in-house CAS group. No significant differences

were observed among the three groups. However, the 3DD results were

11.2 mm on average (SD: 7.4) in the non-CAS group, 4.2 mm on

average (SD: 2.4) in the TruMatch group, and 5.1 mm on average (SD:

2.7) in the in-house CAS group. The 3DD results indicated that

CAS-assisted cases were significantly more accurate, with no

significant difference between the TruMatch and in-house CAS

groups. However, significant differences were observed between the

TruMatch and non-CAS groups (adjusted P=0.0193) and between the

in-house CAS and non-CAS groups (adjusted P=0.0499).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of

mandibular reconstruction using three approaches: conventional

(non-CAS), outsourced CAS (TruMatch), and in-house CAS. The results

demonstrated that both CAS methods significantly improved

mandibular segment positioning compared with the conventional

method, with no significant difference in accuracy between

outsourced and in-house CAS.

In conventional mandibular reconstruction, plates

are typically pre-bent and temporarily fixed to the mandible before

resection to preserve the spatial relationship between bone

segments. However, this technique is feasible only when the bone

surface is clearly visible and unaffected by disease. In cases

involving tumor-related deformity or indistinct resection margins,

preoperative plate fixation is not possible, and attempting it may

result in plate protrusion and facial deformity.

All CAS cases in this study were selected because

preoperative plate fixation could not be performed. By contrast,

the non-CAS group included patients in whom reconstruction plates

were not applicable, and miniplates with bone grafts were used

instead. This selection strategy ensured that all groups faced

comparable surgical challenges regarding mandibular segment

positioning. Importantly, the presence or absence of bone grafting

does not influence the accuracy of segment alignment, which was the

primary focus of this study. This statement is supported by

internal data comparing CAS cases with and without bone grafting,

which showed no significant difference in either ICD or 3DD

(Fig. S1). Therefore, we believe

that bone grafting does not affect the spatial positioning of

mandibular segments, and the comparison across groups remains

valid.

The advantages of using CAS in mandibular

reconstruction are as follows: i) the ability to define the

resection range precisely by simulating surgery on CT images; ii)

the cutting-guide device for the mandible enables accurate and

efficient bone resection; iii) the grafting-bone cutting-guide

reduces the preparation time required for bone adjustment; iv) the

occlusal relationship can be maintained almost identically to the

preoperative condition; and v) custom-made plates eliminate the

need for bending, minimizing the risk of plate fracture due to

metal fatigue (16,21). However, outsourced custom-made CAS

systems also have some limitations. First, they require a

preparation period of at least 1 month, making them challenging to

use in malignant tumor cases. Due to outsourcing, the high costs

make it difficult for hospitals to profit, and cancellations can

result in significant financial losses. Additionally, since the

meetings are held online, it can be difficult for engineers to

fully understand the surgeon's specific needs (17). The outsourcing retains all data

during the creation process, meaning the hospital only receives the

final product. To address these issues, we initiated mandibular

reconstruction using our in-house CAS system in 2022. In terms of

cost, the outsourced TruMatch system, including the custom plate,

screws, surgical guides, and 3D models, typically costs more than

¥800,000 per case in Japan. By contrast, our in-house CAS system

costs approximately ¥150,000 per case. This substantial cost

reduction is primarily attributed to our institution's ownership of

3D printing equipment and the availability of skilled dental

technicians proficient in the software and fabrication process.

Although these institutional advantages may not be universally

applicable, they demonstrate the potential for cost-effective CAS

implementation in facilities with comparable resources.

The reported improvement in efficiency from

shortening the operation time is between 80 and 88 min (6,22), and

the reduction in free-flap ischemia time is reported to be 36–50

min (19,22). One of the greatest advantages of

reconstruction using surgical devices with CAS is that the surgical

plan can be easily and rapidly reproduced in the operating room.

The learning curve for freehand graft bone sculpting and plate

bending without CAS is long, and outcomes vary between surgeons

depending on their experience and technical skills (23). CAS, through the use of surgical

guides, reduces the learning curve of mandibular reconstruction and

significantly enhances proficiency and precision (13,22).

Surgical results using surgical guides are consistent and

reproducible, even by surgeons with varying levels of experience,

which benefits less experienced surgeons (14). In our study, all surgeries were

performed by a consistent surgical team specializing in oral and

maxillofacial oncology. The core members of this team remained

unchanged across the three groups (non-CAS, outsourced CAS, and

in-house CAS), minimizing variability related to individual surgeon

experience. However, we acknowledge that other potential

confounding factors, such as differences in tumor size, defect

classification, and the presence or absence of bone grafting, may

have influenced the outcomes. To mitigate this, cases were selected

based on a common criterion: the inability to perform preoperative

plate fixation due to tumor-related bone deformity or unclear

resection margins. Furthermore, internal data comparing CAS cases

with and without bone grafting showed no significant difference in

ICD or 3DD, suggesting that grafting itself does not affect segment

positioning accuracy. These factors support the validity of our

comparative analysis.

Several classification systems for mandibular

defects have been proposed, with the HCL classification being the

most widely used due to its simplicity (20,24).

However, it may lack detail in distinguishing functional and

reconstructive differences within the same category. In Japan, the

CAT classification offers a more detailed framework by using six

anatomical landmarks, allowing for better prediction of

reconstruction strategies and outcomes (25). Although more complex, it provides

clearer guidance for clinical decision-making. In this study, the

HCL classification was used for consistency with international

standards. Generally, mandibular reconstruction may be more

difficult in LC and LCL cases due to mandibular defects in the

anterior region compared to cases classified as L. However, this

trend was not observed in this study. Although it might be

difficult to detect a trend due to the small number of cases, it is

possible that when CAS is used, accuracy is not affected even in

cases with mandibular defects in the anterior region.

This single-center retrospective study compared the

accuracy of reconstruction using CAS vs. non-CAS after mandibular

resection in cases where the reconstruction plate could not be

placed directly on the mandible before mandibular resection

intraoperatively. Among the cases using CAS, we also compared

outsourced CAS using TruMatch with in-house CAS. In these

comparisons, the 3DD values, which represent the displacement of

the mandibular condyle, showed that CAS-based reconstruction

methods were significantly more accurate. Furthermore, our in-house

CAS was comparable to the outsourced CAS, with almost identical

accuracy. There have been previous reports on the application of

CAS in mandibular reconstruction. For these methods to be

implemented and established as superior techniques, evaluating

their accuracy is essential. Measurements used to determine

accuracy include ICD, intergonial distance, anterior-posterior

distance, and gonial angle (26).

However, in many cases of mandibular segmental resection, the

mandibular angle and anterior teeth are also resected, and in

practice, only the ICD could be measured in almost all our cases.

Since the change in ICD may not reflect slight changes before and

after surgery, we chose to superimpose the healthy side using pre-

and postoperative 3D images and measure the displacement of the

affected mandibular condyle as 3DD. Therefore, in our cases, we did

not find a significant difference in ICD between non-CAS and CAS,

but we did find a significant difference in 3DD.

Several studies have reported on mandibular

reconstruction using either outsourced CAS or unique in-house CAS,

but few have directly compared the two (14). In our study, no significant

difference in accuracy was observed between in-house CAS and

outsourced CAS. Both approaches improved operation time and

occlusal relationships, and the fit between the reconstruction

plate and the mandible was enhanced. However, TruMatch employs a

custom plate, which may contribute to slightly higher accuracy.

In-house CAS requires the use of a standard reconstruction plate,

which is weaker than the custom-made outsourced plate, and this

limitation needs improvement in the future. However, because custom

plates take time to manufacture, the TruMatch system requires a

minimum of one month for preparation, limiting its usefulness in

malignant tumor surgeries. On the other hand, in-house CAS can be

used in as little as one week of preparation, making it suitable

for emergency surgeries. This explains why our results show a

higher proportion of malignant tumor patients in the in-house CAS

cases compared to TruMatch cases. Although occlusal stability

appeared visually consistent in CAS cases, a more detailed and

objective analysis is warranted. Future studies should address this

aspect to more accurately quantify functional outcomes. In

contrast, occlusal abnormalities were observed in several cases

within the non-CAS group, including malalignment and asymmetry of

the dental arches, as noted during routine postoperative follow-up

and radiographic evaluation. These findings suggest that even minor

deviations in mandibular positioning can lead to functional

impairment, particularly when preoperative plate fixation is not

feasible. While no severe mastication disorders or

temporomandibular joint dysfunction were reported within one month

postoperatively, the presence of occlusal discrepancies underscores

the importance of incorporating functional assessments into future

studies. Quantitative evaluation of occlusal force, mandibular

mobility, and long-term functional outcomes will be essential to

fully understand the clinical impact of CAS-based

reconstruction.

Directions for further improving mandibular

reconstruction using CAS include improving preoperative surgical

planning and revising and upgrading the equipment used during

surgery. For example, when determining the extent of resection,

which is a crucial factor in mandibular reconstruction for

malignant tumor surgeries, machine learning may be able to

automatically determine the appropriate resection extent by

superimposing not only CT scans but also magnetic resonance imaging

and positron emission tomography-CT images. Furthermore,

mathematical modeling and machine learning may reduce the reliance

on the capabilities of surgeons and clinical engineers to select

the optimal reconstruction solution and suggest the ideal shape of

the surgical device (27).

Additionally, 3D printed mandibular reconstruction plates are now

available and are preferred over pre-bent plates because they offer

more accurate results and are less likely to break. However,

attention should be given to disadvantages, such as plate exposure,

especially if the design becomes too complex (22,28).

To minimize the risk of breakage due to bending of ready-to-use

reconstruction plates, this can be addressed by developing

efficient bending techniques.

Although our in-house CAS system currently relies on

commercially available software such as Vincent (Fujifilm, Japan)

and 3Shape Dental System (3Shape, Denmark), it is used in a

customized manner not originally intended for clinical mandibular

reconstruction. To address concerns regarding generalizability and

reproducibility, we are actively developing a dedicated software

platform that integrates virtual surgical planning, guide design,

and plate fitting. This new system aims to standardize the workflow

and facilitate broader adoption of in-house CAS techniques in

diverse clinical settings.

Prior to implementing the in-house CAS system, we

gained experience with several cases using the outsourced TruMatch

system. The design of our in-house surgical guides and positioning

devices was informed by the structure and functionality of those

used in TruMatch, allowing us to adopt and adapt effective design

elements. This experience contributed to the reproducibility and

reliability of our in-house workflow, despite the continued use of

standard reconstruction plates.

In terms of plate fitting accuracy, the TruMatch

system clearly outperforms the in-house CAS approach. This

limitation arises from manual plate bending, which inevitably

introduces gaps between the plate and the bone surface. Such gaps

can result in misalignment during fixation, as the plate may be

secured in a position deviating from that planned on the 3D model.

To mitigate this issue, our in-house CAS workflow incorporates a

custom-designed device that enables the precise placement of

manually bent plates at the intended location. While this does not

eliminate the inherent limitations of manual bending, it ensures

that the plate is fixed exactly where planned, thereby improving

reproducibility and reducing positional errors.

As a future direction, we aim to develop techniques

or tools that further minimize the gap between manually bent plates

and the bone surface, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of

in-house CAS-based mandibular reconstruction. However, in this

study, the fit of the plate was not assessed objectively, as no

standardized imaging or intraoperative measurement protocols were

implemented. Future studies should incorporate objective methods to

evaluate plate fitting accuracy, such as quantitative measurement

of the plate-to-bone gap using high-resolution postoperative CT

imaging and assessment of the contact surface area with 3D modeling

software.

Finally, we acknowledge that this study evaluated

surgical accuracy only at approximately 1 month postoperatively.

Long-term functional outcomes, including occlusal stability, mouth

opening, aesthetic appearance, and postoperative complications such

as non-union or infection, were not assessed. These factors are

critical for determining the true clinical value of CAS-based

mandibular reconstruction. Future prospective studies with extended

follow-up periods are warranted to comprehensively evaluate both

functional and aesthetic outcomes over time.

In addition to technical improvements, future

research should focus on study design enhancements. Given the

retrospective nature of the present study, randomization and

stratification by surgeon experience were not feasible. Prospective

studies with randomized designs and clearly defined surgeon

qualifications and experience levels would help reduce potential

confounding factors and strengthen the evidence supporting

CAS-based mandibular reconstruction.

In conclusion, the use of CAS systems in mandibular

reconstruction surgery may be particularly advantageous in cases

involving mandibular resection where postoperative occlusal

reconstruction is challenging. In-house CAS systems provide

comparable and favorable outcomes to outsourced CAS, making them a

potentially cost-effective option for precise reconstructive

surgery and enabling a greater number of patients to benefit from

CAS technology in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the OU Master Plan Implementation

Project from The University of Osaka.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ShK, YM, TM and NU conceptualized the study and

designed the overall research approach. ShK, RK, KK, ATN and EO

performed experiments and ensured their completeness and integrity.

ShK and YM confirm the authenticity of the all the raw data. ShK,

YM, RK, TM, KK, ATN and EO performed formal statistical analyses.

YM and NU acquired funding for the project. ShK, RK, YU, SaK, YMM,

AT and KM conducted experimental and clinical investigations. ShK,

YM, RK, TM and KK developed and optimized the study methodology,

including experimental protocols and analysis pipelines. ShK, YM,

RK, TM, KK, AN, EO, YU, SaK, AT, KM and NU provided essential

resources, including access to clinical samples, instrumentation

and institutional facilities. ShK, YM, RK and TM developed and

maintained the software tools used for image processing and data

analysis. ShK, YM and NU supervised and validated the study steps

and results. ShK produced the visual materials (figures and

schematic diagrams) and, together with YM, prepared the initial

draft of the manuscript. ShK, SaK, YM, YMM, AT, KM and NU

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content and approved the final version. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all

aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent for

participation

The study was approved by The University of Osaka

Graduate School of Dentistry Research Ethics Committee (approval

number: R6-E35). All methods were performed in accordance with the

relevant guidelines and regulations of the Basel Declaration.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients using an opt-out

method.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hirsch DL, Garfein ES, Christensen AM,

Weimer KA, Saddeh PB and Levine JP: Use of computer-aided design

and computer-aided manufacturing to produce orthognathically ideal

surgical outcomes: A paradigm shift in head and neck

reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 67:2115–2122. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chang EI, Jenkins MP, Patel SA and Topham

NS: Long-term operative outcomes of preoperative computed

tomography-guided virtual surgical planning for osteocutaneous free

flap mandible reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 137:619–623.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Antony AK, Chen WF, Kolokythas A, Weimer

KA and Cohen MN: Use of virtual surgery and

stereolithography-guided osteotomy for mandibular reconstruction

with the free fibula. Plast Reconstr Surg. 128:1080–1084. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Largo RD and Garvey PB: Updates in head

and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 141:271e–285e. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ren W, Gao L, Li S, Chen C, Li F, Wang Q,

Zhi Y, Song J, Dou Z, Xue L and Zhi K: Virtual Planning and 3D

printing modeling for mandibular reconstruction with fibula free

flap. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 23:e359–e366. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang YY, Zhang HQ, Fan S, Zhang DM, Huang

ZQ, Chen WL, Ye JT and Li JS: Mandibular reconstruction with the

vascularized fibula flap: Comparison of virtual planning surgery

and conventional surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 45:1400–1405.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Toto JM, Chang EI, Agag R, Devarajan K,

Patel SA and Topham NS: Improved operative efficiency of free

fibula flap mandible reconstruction with patient-specific,

computer-guided preoperative planning. Head Neck. 37:1660–1664.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kumta S, Kumta M, Jain L, Purohit S and

Ummul R: A novel 3D template for mandible and maxilla

reconstruction: Rapid prototyping using stereolithography. Indian J

Plast Surg. 48:263–273. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Avraham T, Franco P, Brecht LE, Ceradini

DJ, Saadeh PB, Hirsch DL and Levine JP: Functional outcomes of

virtually planned free fibula flap reconstruction of the mandible.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 134:628e–634e. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu YF, Xu LW, Zhu HY and Liu SSY:

Technical procedures for template-guided surgery for mandibular

reconstruction based on digital design and manufacturing. Biomed

Eng Online. 13:632014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mazzoni S, Marchetti C, Sgarzani R,

Cipriani R, Scotti R and Ciocca L: Prosthetically guided

maxillofacial surgery: Evaluation of the accuracy of a surgical

guide and custom-made bone plate in oncology patients after

mandibular reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 131:1376–1385.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hanasono MM and Skoracki RJ:

Computer-assisted design and rapid prototype modeling in

microvascular mandible reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 123:597–604.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Foley BD, Thayer WP, Honeybrook A, McKenna

S and Press S: Mandibular reconstruction using computer-aided

design and computer-aided manufacturing: An analysis of surgical

results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 71:e111–e119. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pucci R, Weyh A, Smotherman C, Valentini

V, Bunnell A and Fernandes R: Accuracy of virtual planned surgery

versus conventional free-hand surgery for reconstruction of the

mandible with osteocutaneous free flaps. Int J Oral Maxillofac

Surg. 49:1153–1161. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rodby KA, Turin S, Jacobs RJ, Cruz JF,

Hassid VJ, Kolokythas A and Antony AK: Advances in oncologic head

and neck reconstruction: Systematic review and future

considerations of virtual surgical planning and computer aided

design/computer aided modeling. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg.

67:1171–1185. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Dong QN, Karino M, Osako R, Ishizuka S,

Toda E, Kanayama J, Sato S, Okuma S, Okui T and Kanno T:

Computer-assisted fabrication of a cutting guide for marginal

mandibulectomy and a patient-specific mandibular reconstruction

plate: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol.

33:505–512. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ohyama Y, Hasegawa K, Uzawa N, Yamashiro

M, Michi Y, Inaba Y, Kubota M, Kanemaru T, Iwasaki T and Yoda T:

Vascularized bony reconstruction after mandibular resection-Report

and discussion of experience with 3 types of plates. Jpn J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 69:493–498. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Metzler P, Geiger EJ, Alcon A, Ma X and

Steinbacher DM: Three-dimensional virtual surgery accuracy for free

fibula mandibular reconstruction: planned versus actual results. J

Oral Maxillofac Surg. 72:2601–2612. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang L, Liu Z, Li B, Yu H, Shen SG and

Wang X: Evaluation of computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction

with vascularized fibular flap compared to conventional surgery.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 121:139–148. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Boyd JB, Gullane PJ, Rotstein LE, Brown DH

and Irish JC: Classification of mandibular defects. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 92:1266–1275. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Koyachi M, Sugahara K, Tachizawa K,

Nishiyama A, Odaka K, Matsunaga S, Sugimoto M and Katakura A:

Mixed-reality and computer-aided design/computer-aided

manufacturing technology for mandibular reconstruction: A case

description. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 13:4050–4056. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Blanc J, Fuchsmann C, Nistiriuc-Muntean V,

Jacquenot P, Philouze P and Ceruse P: Evaluation of virtual

surgical planning systems and customized devices in fibula free

flap mandibular reconstruction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

276:3477–3486. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bartier S, Mazzaschi O, Benichou L and

Sauvaget E: Computer-assisted versus traditional technique in

fibular free-flap mandibular reconstruction: A CT symmetry study.

Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 138:23–27. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jagtiani K, Gurav S, Singh G and Dholam K:

A review on the classification of mandibulectomy defects and

suggested criteria for a universal description. J Prosthet Dent.

132:270–277. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hashikawa K, Yokoo S and Tahara S: Novel

classification system for oncological mandibular defect: CAT

classification. Jpn J Head Neck Cancer. 34:412–418. 2008.

|

|

26

|

Annino DJ Jr, Sethi RK, Hansen EE, Horne

S, Dey T, Rettig EM, Uppaluri R, Kass JI and Goguen LA: Virtual

planning and 3D-printed guides for mandibular reconstruction:

Factors impacting accuracy. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol.

7:1798–1807. 2022. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang E, Durham JS, Anderson DW and Prisman

E: Clinical evaluation of an automated virtual surgical planning

platform for mandibular reconstruction. Head Neck. 42:3506–3514.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang WF, Choi WS, Wong MCM, Powcharoen W,

Zhu WY, Tsoi JK, Chow M, Kwok KW and Su YX: Three-dimensionally

printed patient-specific surgical plates increase accuracy of

oncologic head and neck reconstruction versus conventional surgical

plates: A comparative study. Ann Surg Oncol. 28:363–375. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|