Introduction

The incidence rate and mortality of prostate cancer

(PCa) pose a huge threat to global health (1). The androgen receptor (AR) signaling

pathway, as the most important growth signaling axis, plays an

important role in PCa progression (2,3). This

is mainly closely related to the numerous downstream target genes

regulated by AR, which are widely involved in multiple tumor

characteristics of PCa (2).

Therefore, identification of novel AR downstream target genes and

clarification of their functions are expected to bring new insights

into PCa diagnosis and treatment. In the present study, it was

found that SENP5 acts as a downstream target of AR and

contributions to PCa growth.

SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) mainly consist of 7

genes, namely SENP1, SENP2, SENP3, SENP5, SENP6, SENP7 and SENP8,

and their abnormal expression are closely related to the

development of multiple tumors (4).

Currently, the main research hotspots are SENP1 and SENP2 of this

family, and a large number of studies have shown that SENP1/2 can

act as oncogenes involving PCa progression (4,5).

Further research reveals that SENP1 and SENP2 are downstream target

genes of AR (6). However, the roles

of other genes in this family have not yet been clarified in

PCa.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The present study and all related procedures were

approved (approval no. 2021-1142) by the Ethics Committee of

Zhejiang University School of Medicine Second Affiliated Hospital

(Hangzhou, China). Prior to conducting the study, informed consent

forms were obtained from all patients with PCa participating in the

study.

Bioinformatics

JASPARA database (https://jaspar.elixir.no/) was used to predicted

sequences of transcription factor AR binding to the promoter of

SENPs genes.

Survival analysis

The survival analysis of SENPs was obtained from the

GEPIA 2.0 database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), including overall

survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with

cancer. Patients were divided into two groups according to the

tumor types and the levels of SENPs from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) database (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga),

either lower or higher than the mean level. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a significantly significant difference. The

95% confidence interval (CI) is presented as dotted line, hazards

ratio (HR).

Cell lines and cell culture

LNCaP cells (cat. no. CRL-1740) were purchased from

the American Type Culture Collection, cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 media (cat. no. PYG0006; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in

37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere. To mimic patients undergoing

ADT treatment, androgen-independent cell lines, had already been

generated: LNCaP-AI cells derived from androgen-sensitive LNCaP

cells cultured under androgen-depleted conditions (7). LNCaP-AI cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium with 10% dextran-charcoal stripped FBS (CS-FBS;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Reagents and antibodies

Enzalutamide (cat. no. MDV3100) was purchased from

Selleck Chemicals and dihydrotestosterone (DHT; cat. no. A8380)

from MilliporeSigma. Antibody against GAPDH (cat. no. 5174) was

obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Anti-human SENP5 (cat

no. 19529-1-AP) antibody was purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc.

Secondary antibodies [HRP-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit antibodies

(cat. no. AP510P) or HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse antibodies

(cat. no. AC111P)] for western blotting were obtained from

MilliporeSigma. DyLight 488 AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L)

for immunofluorescence were obtained from Abbkine Scientific Co.,

Ltd.

Immunofluorescence staining of

tissues

Immunofluorescence staining with SENP5 was performed

as previously described (8).

Transfection

LNCaP and LNCaP-AI cells were seeded in six-well

plates (5×105/well) and transfected with the siRNAs (100

nM) using Lipofectamine 2000® according to the

manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

siRNAs used in the study were as follows: siSENP5 #1:

5′-CCAACACTTGTGCATTCTGAA-3′; siSENP5 #2:

5′-CCTTACCAGAACATCGTTCTA-3′; siAR: 5′-GGAACTCGATCGTATCATTGC-3′;

negative control: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′. Cell transfection

was performed for 6 h at 37°C, after which the medium was replaced.

After 48 h, the cells were collected for subsequent

experiments.

Western blot analysis

Total protein of cells was extracted with RIPA

buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), and western blot

analysis was performed as previously described (9).

Cell Counting Kit-8 assay

LNCaP and LNCaP-AI cells were transfected with siScr

or siSENP5 for 48 h. Cell proliferation assay was performed as

previously described (9).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

RNA isolation and qPCR were performed as previously

described (8). Primers used were as

follows: SENP5 forward, 5′-CTTTAGGTCAGGCCAATGGTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CAGCAGCCGTAACAAAAGCC-3; and GAPDH forward,

5′-AACAGCCTCAAGATCATCAGCA-3′ and reverse,

5′-CATGAGTCCTTCCACGATACCA-3′.

Chromatin

immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR assays (ChIP-qPCR)

ChIP-qPCR was performed as previously described

(10). Cells (5×107)

were collected, followed by ChIP assays with anti-AR (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 5153) or IgG (Proteintech

Group, Inc.; cat no. 30000-0-AP). qPCR analysis was carried out on

ChIPed and input DNA. Data are presented as percent of input DNA,

and error bars represent S.D. for technical duplicates of the qPCR

analysis. Primer sequences to detect the AR binding site along the

SENP5 promoter were as follows: SENP5-ChIP-F1:

TGGGGCGGGTAAGACATAGA; SENP5-ChIP-R1: CCATTCCAGCTCTGGACGTT.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8

(Dotmatics). The values were shown as the mean ± S.D. for

triplicate experiments and the statistical differences were

calculated by one-way ANOVA analysis of variance with Dunnett's

test or Newman-Keuls test and Student's two-tailed t-test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

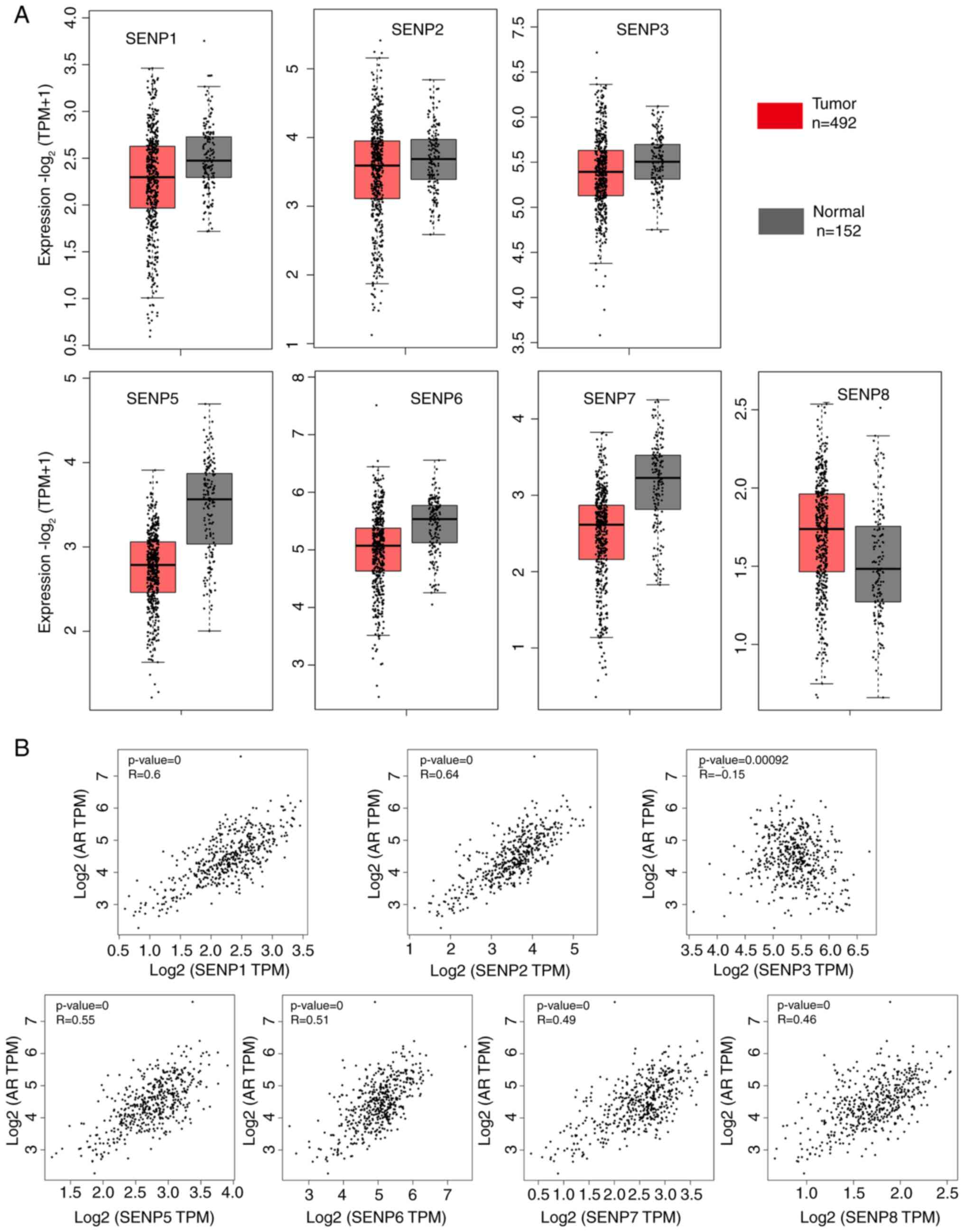

SENPs are potential downstream target

genes of transcription factor AR

In order to clarify the expression and potential

clinical values of SENPs in PCa, firstly, the mRNA expression level

of SENPs were analyzed in PCa and normal tissues using the TCGA

database. As revealed in Fig. 1A,

the expression level of SENPs were almost no difference between PCa

and normal tissues. However, interestingly, significant

co-expression between SENPs and AR was found (Fig. 1B), except for SENP3, strongly

indicating a potential regulatory relationship between SENPs and

AR. It has been previously reported that AR can transcriptionally

regulate SENP1 and SENP2 (6).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that AR may also be able to

transcriptionally regulate other genes in the SENP family. Using

the public online tool JASPARA, an interaction was found between

the promoter regions of SENPs genes and the transcription factor AR

(Table SI, Table SII, Table SIII, Table SIV, Table SV, Table SVI, Table SVII). These data indicated that

SENPs are potential downstream target genes of transcription factor

AR.

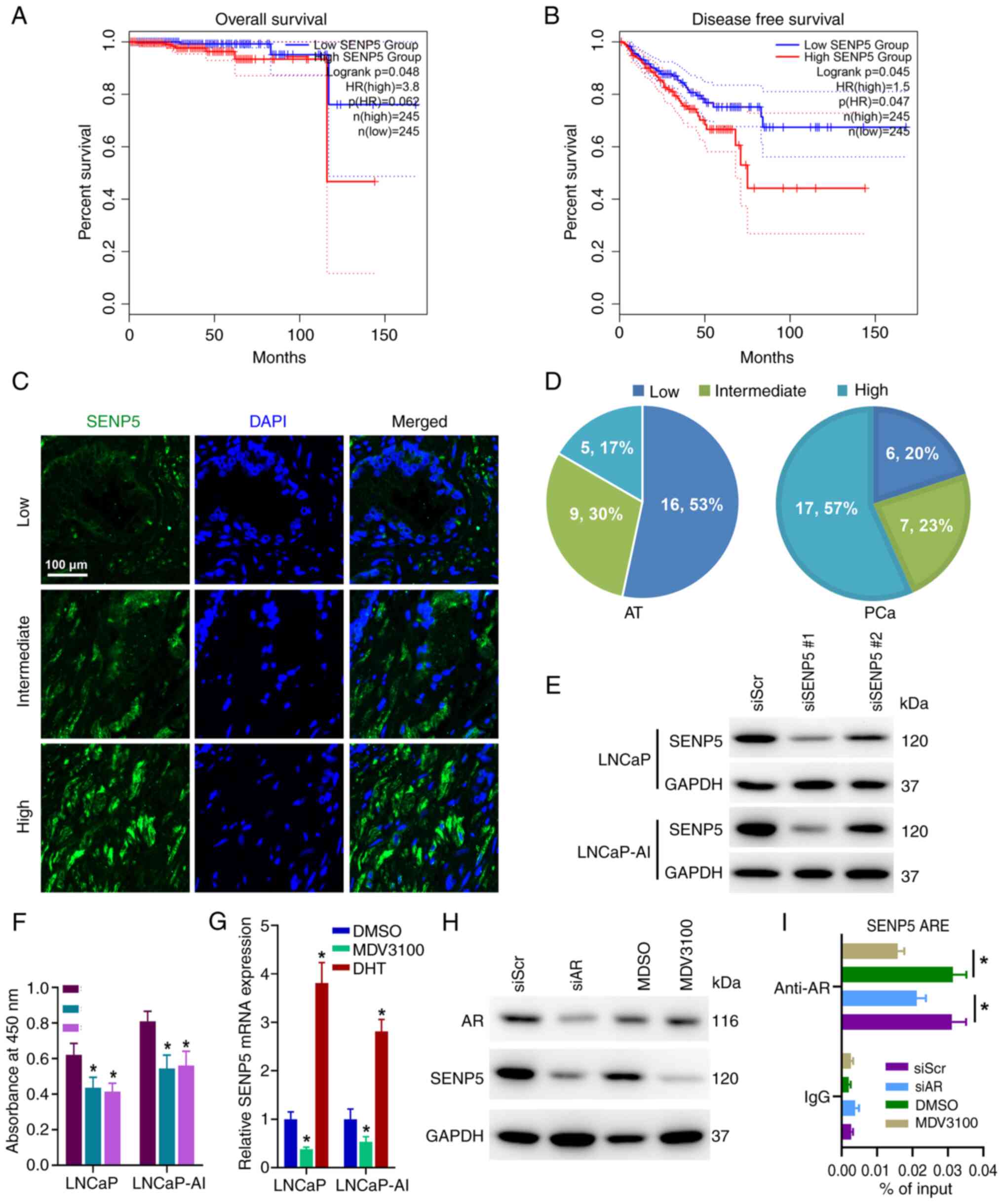

SENP5 acts as a downstream target of

AR and contributes to PCa growth

Despite there was almost no difference in the

expression level of SENPs between PCa and normal tissues, it was

attempted to further clarify whether the expression of SENPs is

related to the prognosis of PCa. Using the TCGA database, it was

found that the mRNA expression of SENP5 was significantly

negatively associated with OS (Fig.

2A) and DFS (Fig. 2B) in PCa,

while other genes in the SENP family were not markedly associated

with OS and DFS (Fig. S1),

indicating that high expression of SENP5 is associated with poor

prognosis in PCa. Furthermore, it was found that the protein level

of SENP5 was markedly higher in PCa tissues compared with normal

adjacent tissues through immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 2C and D). In addition, SENP5

silencing significantly inhibited the proliferation activity of

LNCaP and LNCaP AI cells (Fig. 2E and

F). These results suggested that SENP5 may act as an oncogene

in PCa.

To further illuminate the regulatory mechanism

between AR and SENP5, PCa cell lines (LNCaP and LNCaP-AI) were

treated with MDV3100 and DHT respectively. DHT, the most potent

androgen, is usually synthesized in the prostate from testosterone

secreted by the testis, which acts as the activating ligand of AR

(11). Furthermore, MDV3100 is an

antagonist of AR that is widely used in the treatment of patients

with PCa (12). Compared with the

control group, qPCR results showed that the mRNA level of SENP5 was

significantly reduced after MDV3100 treatment (Fig. 2G). On the contrary, the mRNA level

of SENP5 significantly increased after DHT treatment (Fig. 2G). Consistent with the mRNA results,

similar results were also obtained at the protein level (Fig. 2H). In addition, it was further

confirmed that AR could transcriptionally activate SENP5 expression

using CHIP-qPCR (Fig. 2I). These

results further confirmed that SENP5 is indeed a direct downstream

target gene of AR.

Discussion

SUMO-mediated signaling is a proteome regulatory

pathway that plays a key role in maintaining cellular physiological

functions (13,14). Aberrant SENPs expression promotes

the development and progression of multiple cancers, including

colon cancer (15), ovarian cancer

(16), and breast cancer (17). In the present study, it was

demonstrated that SENP5 protein level was markedly elevated in PCa

tissues compared to normal adjacent tissues. Moreover, knocking

down SENP5 significantly inhibited the growth activity of PCa

cells, indicating that SENP5 may act as an oncogene in PCa.

High-level expression of SENP5 is significantly associated with

poor prognosis, further suggests that SENP5 is an oncogene in PCa

(Fig. 2B). Our finding is

consistent with its role in promoting drug resistance in colon

cancer (18).

Furthermore, it was confirmed that SENP5 is a direct

downstream target gene of AR. Firstly, TCGA dataset showed

significant co-expression between SENP5 and AR (Fig. 1B). Using JASPARA database, we

further found an interaction between the promoter regions of SENP5

and AR, strongly indicating that SENP5 is a potential downstream

target gene of AR. Thus, we further verified the result using

CHIP-qPCR, as expected, SENP5 is indeed a direct downstream target

gene of AR (Fig. 2I). Our finding

further expands the types of SENPs targeted by AR, in addition to

SENP1 and SENP2 (6), but also

SENP5. To some extent, this also implies that inhibition of SENP5

may induce the expression of SENP1 and SENP2 as a negative feedback

mechanism to maintain the growth of PCa cells, and the combined

blockade of AR and SENP5 may be an improved therapeutic

strategy.

Taken together, our results suggest that SENP5 is a

novel downstream target gene of AR, and its mRNA level is

significantly associated with poor prognosis in PCa, indicating

that SENP5 can participate in the occurrence and development of PCa

as an oncogene, the underlying molecular mechanism of which needs

further investigation. Thus, SENP5 has great potential to become a

new target for the diagnosis and treatment of PCa.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Clinical

Research Center, Zhejiang University School of Medicine Second

Affiliated Hospital for essential technical support and the use of

the laboratory to perform experiments.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China Youth Science Foundation Project (grant no.

81802571) and Zhejiang Medical and Health Science and Technology

Project (grant no. 2019RC039).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

WL and JZ designed the study. XC, XG and WL

performed the experiments. XC, XG and WL supervised specific

experiments and revised the manuscript. WL wrote the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. WL and JZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All samples were collected from patients with

informed consent, and all related procedures were performed with

the approval of the internal review and ethics boards of Zhejiang

University School of Medicine Second Affiliated Hospital (approval

no. 2021-1142; Hangzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49. 2024.

|

|

2

|

Mills IG: Maintaining and reprogramming

genomic androgen receptor activity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev

Cancer. 14:187–198. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Dai C, Dehm SM and Sharifi N: Targeting

the androgen signaling axis in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol.

41:4267–4278. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Claessens LA and Vertegaal ACO: SUMO

proteases: From cellular functions to disease. Trends Cell Biol.

34:901–912. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chang HM and Yeh ETH: SUMO: From bench to

bedside. Physiol Rev. 100:1599–1619. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kaikkonen S, Jääskeläinen T, Karvonen U,

Rytinki MM, Makkonen H, Gioeli D, Paschal BM and Palvimo JJ:

SUMO-specific protease 1 (SENP1) reverses the hormone-augmented

SUMOylation of androgen receptor and modulates gene responses in

prostate cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 23:292–307. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Xu G, Wu J, Zhou L, Chen B, Sun Z, Zhao F

and Tao Z: Characterization of the small RNA transcriptomes of

androgen dependent and independent prostate cancer cell line by

deep sequencing. PLoS One. 5:e155192010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu W, Wang X, Wang Y, Dai Y, Xie Y, Ping

Y, Yin B, Yu P, Liu Z, Duan X, et al: SGK1 inhibition-induced

autophagy impairs prostate cancer metastasis by reversing EMT. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 37:732018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liu W, Wang X, Wang Y, Dai Y, Xie Y, Ping

Y, Yin B, Yu P, Liu Z, Duan X, et al: SGK1 inhibition induces

autophagy-dependent apoptosis via the mTOR-Foxo3a pathway. Br J

Cancer. 117:1139–1153. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liang D, Feng Y, Zandkarimi F, Wang H,

Zhang Z, Kim J, Cai Y, Gu W, Stockwell BR and Jiang X: Ferroptosis

surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by

sex hormones. Cell. 186:2748–2764.e2722. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chang KH, Li R, Kuri B, Lotan Y, Roehrborn

CG, Liu J, Vessella R, Nelson PS, Kapur P, Guo X, et al: A

gain-of-function mutation in DHT synthesis in castration-resistant

prostate cancer. Cell. 154:1074–1084. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Higano CS, Beer TM, Taplin ME, Efstathiou

E, Hirmand M, Forer D and Scher HI: Long-term safety and antitumor

activity in the phase 1–2 study of enzalutamide in pre- and

post-docetaxel castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol.

68:795–801. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Claessens LA, Verlaan-de Vries M, de Graaf

IJ and Vertegaal ACO: SENP6 regulates localization and nuclear

condensation of DNA damage response proteins by group

deSUMOylation. Nat Commun. 14:58932023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lin H, Suzuki K, Smith N, Li X, Nalbach L,

Fuentes S, Spigelman AF, Dai XQ, Bautista A, Ferdaoussi M, et al: A

role and mechanism for redox sensing by SENP1 in β-cell responses

to high fat feeding. Nat Commun. 15:3342024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wei M, Huang X, Liao L, Tian Y and Zheng

X: SENP1 decreases RNF168 phase separation to promote DNA damage

repair and drug resistance in colon cancer. Cancer Res.

83:2908–2923. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhang Y, Wei H, Zhou Y, Li Z, Gou W, Meng

Y, Zheng W, Li J, Li Y and Zhu W: Identification of potent SENP1

inhibitors that inactivate SENP1/JAK2/STAT signaling pathway and

overcome platinum drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Clin Transl

Med. 11:e6492021. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xiao M, Bian Q, Lao Y, Yi J, Sun X, Sun X

and Yang J: SENP3 loss promotes M2 macrophage polarization and

breast cancer progression. Mol Oncol. 16:1026–1044. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Liu T, Wang H, Chen Y, Wan Z, Du Z, Shen

H, Yu Y, Ma S, Xu Y, Li Z, et al: SENP5 promotes homologous

recombination-mediated DNA damage repair in colorectal cancer cells

through H2AZ deSUMOylation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:2342023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|