Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major cause of

cancer-associated mortality worldwide, In 2023, an estimated 1.97

million new cases of CRC and ~0.93 million deaths were reported

globally (1). The burden of CRC is

increasing in Eastern Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Southeast

Asia, where rapid lifestyle transitions, Westernized diets, and

limited early-screening coverage have contributed to rising

incidence trends (2). In Asia,

~992,000 new CRC cases and ~498,000 related deaths were reported in

2020 (3). Proteomic and genomic

studies have advanced cancer research by revealing molecular

pathways involved in CRC particularly through dysregulated

signaling cascades that drive tumor development and progression,

such as the Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT signaling, MAPK/ERK pathway,

and alterations in TP53-regulated stress response networks, all of

which play key roles in cell proliferation, survival, and

metastasis (4). Among key molecular

players, claudin-2 (CLDN2), a component of tight junctions,

has emerged as a contributor to malignancy by exhibiting aberrant

expression (5).

The claudin family serves a key role in cell

barriers, differentiation and proliferation. The expression

patterns of claudin knockout (KO) vary throughout malignancies and

organs (6). Thus, claudins have

been proposed as targets for cancer treatment as well as diagnostic

indicators. Previous research has demonstrated an increasing

consensus on the potential value of CLDN2 as a biomarker for

prognostic and therapeutic features in CRC (7–9).

Notably, CLDN2 expression is elevated in inflammatory bowel

disease and colorectal tumors compared with normal tissues

(10).

CLDN2 has diverse biological functions beyond

maintaining epithelial permeability. It contributes to paracellular

water and ion transport, modulates epithelial proliferation and

participates in signaling events associated with oncogenic

transformation (8,11). Elevated CLDN2 levels have

been associated with poor prognosis, advanced tumor stages and

increased metastatic potential in several cancer types, including

CRC (7,12). These findings highlight the

importance of understanding the multifunctional role of

CLDN2 in colorectal carcinogenesis. CLDN2 is the most

distinct member of the claudin family and exhibits a unique

expression pattern because its expression is limited to permeable

epithelial tissues (11). In colon

cancer, CLDN2 appears to function as an oncogene, enhancing

cell proliferation and migration capacity through EGFR-mediated

pathways (12). Notably, the

increasing incidence of CRC has been connected to the presence of

CLDN2 in cellular tight junctions.

Mechanistically, it has been demonstrated that

CLDN2 inhibits the transcription of N-Myc

downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1), a well-established metastasis

suppressor gene. This repression is mediated through the

recruitment of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1)-associated nucleic

acid binding protein (ZONAB) to the NDRG1 promoter,

where CLDN2 facilitates ZONAB binding and suppresses

NDRG1 transcriptional activity (13).

Elevated CLDN2 expression has been observed

in CRC compared with adjacent normal tissue and is associated with

shorter cancer-specific survival and increased risk of recurrence

in stage II/III CRC receiving adjuvant therapy (14). Although environmental and genetic

variables can affect CRC, such as diet, obesity, and smoking,

understanding the mechanisms by which CLDN2 functions during

CRC development could help identify potential novel treatment

options in the future. High CLDN2 expression patterns

reported shorter survival outcomes, indicating a connection between

high CLDN2 expression and CRC progression (13).

While genomic analyses have identified driver

mutations in CRC, understanding the mechanisms by which specific

proteins such as CLDN2 integrate into oncogenic signaling

networks remains challenging (15–17).

CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing offers a key tool to dissect

functional roles by enabling precise gene KO models (18). Furthermore, combining CRISPR

approaches with gene expression profiling allows for further

investigation into CRC biology and the identification of potential

novel therapeutic targets in the future (19). Due to the limited mechanistic

understanding of CLDN2 in CRC, the present study aimed to

investigate the effects of CLDN2 deletion on gene expression

patterns associated with migration, invasion and metastasis. A

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated KO approach was used in HCT116 cells to assess

both phenotypic changes and transcriptional alterations, with a

focus on pathways implicated in CRC progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human CRC cell line HCT116 (cat. no. CCL-247;

American Type Culture Collection) was obtained from Synthego. The

HCT116 cell line is a widely used model of CRC repair deficiency

due to a mutation in the mutL homolog 1 gene. Cells were

authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling, and were confirmed

to be mycoplasma-free prior to use.

Wild-type (Wt) and CLDN2-KO HCT116 cells were

cultured in McCoy's 5A medium (cat. no. 16600082; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no. 10270106;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(cat. no. 15140-122; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells

were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2.

Generation of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated

CLDN2-KO cells

CRISPR/Cas9 mediated KO of human CLDN2 (gene

ID, 9075) in HCT116 cells was produced by Synthego. Guide RNA

design and off-target prediction were performed using the Synthego

CRISPR Design Tool (v1.2; Synthego). Ribonucleoprotein complexes

consisting of Cas9 protein and a synthetic, chemically modified

single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting exon 2 of human CLDN2

(sgRNA sequence, 5′-GGUGCUAUAGAUGUCACACU-3′) were electroporated

into HCT116 cells. The sgRNA cut site was chrX:106,928,419.

Following electroporation (20),

single-cell clones were generated by fluorescence-activated cell

sorting into 96- or 384-well plates and expanded (21). The assessment of editing efficiency

was performed 48 h after electroporation. The process involved

extracting genomic DNA (gDNA) from a subset of cells, followed by

PCR amplification and sequencing using the Sanger sequencing

method. Sequencing was performed in the forward direction using a

20-nt primer, generating 700–900 nt reads. Sanger sequencing

services were provided by Synthego. PCR primers were as follows:

Forward, 5′-CAGCCTGAAGACAAGGGAGC-3′; and reverse,

5′-TGTCTTTGGCTCGGGATTCC-3′. The sequencing primer used was as

follows: 5′-CAGCCTGAAGACAAGGGAGC-3′. The chromatograms obtained

were analyzed using the Synthego Inference of CRISPR edits (ICE;

version 2.0 (Synthego) (22).

For insertion-deletion (indel), the indel

examination was performed using the Illumina sequencing platform

(Illumina, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol

(23). A total of 20 ng gDNA was

utilized as a template for amplifying the region surrounding the

sgRNA target site, using the specified primers. To generate

monoclonal cell populations, cell pools with altered CLDN2

gene (CLDN2-KO) were distributed at a density of 1 cell/well

using a single cell printer onto either 96- or 384-well plates

(24). Every 3 days, all wells were

recorded to verify the growth of a clone originating from a single

cell. The PCR-Sanger-ICE genotyping technique was used to screen

and identify clonal populations.

Wound healing assay

The migratory capacity of Wt and CLDN2-KO

cells was assessed using a wound healing assay (25). Briefly, 3×105 cells/well

were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured until they reached 90%

confluence. After which, a sterile pipette tip was used to scratch

across the center of each well, creating a defined wound area.

Detached cells were removed by washing with 500 µl PBS and fresh

culture medium was added. Subsequently, cell migration into the

scratched area was monitored and captured at 0 and 24 h using a

Nikon E 600 phase-contrast microscope. Images of the wound area

were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 2.9.0/1.53t; National

Institutes of Health) (26). Wound

closure percentage was calculated as

[(At=0-At=∆t)/At=0] ×100, where

At=0 is the scratch area at 0 h and At=∆t is

the scratch area at 24 h.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated in accordance with the

manufacturer's protocol using an RNA extraction kit (cat. no.

R1200; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized using random nonamer primers and

the First-Strand Synthesis System (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA).

EvaGreen fluorescence-based RT-qPCR was performed using reagents

purchased from Applied Biological Materials, Inc. RT-qPCR reactions

were performed following standard protocols as previously described

(27). The RT-qPCR primers used in

the present study are listed in Table

I. The gene expression levels in the samples were investigated

using RT-qPCR and the cDNA synthesis and PCR procedures were

optimized to ensure high-quality results.

| Table I.Primers for RT-qPCR used in the

present study. |

Table I.

Primers for RT-qPCR used in the

present study.

| Gene symbol | Oligo sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| AF-6

(AFDN) | F:

AGTCGGTTGTGAAAGGAGGTGC |

|

| R:

TCCTGAGAGAGTCCAACCAGAC |

| APC | F:

AGGCTGCATGAGAGCACTTGTG |

|

| R:

CACACTTCCAACTTCTCGCAACG |

| Bax | F:

TCAGGATGCGTCCACCAAGAAG |

|

| R:

TGTGTCCACGGCGGCAATCATC |

| Bcl-2 | F:

ATCGCCCTGTGGATGACTGAGT |

|

| R:

GCCAGGAGAAATCAAACAGAGGC |

| Bcl-6 | F:

CATGCAGAGATGTGCCTCCACA |

|

| R:

TCAGAGAAGCGGCAGTCACACT |

| Caspase

3 | F:

GGAAGCGAATCAATGGACTCTGG |

|

| R:

GCATCGACATCTGTACCAGACC |

| CDK4 | F:

CCATCAGCACAGTTCGTGAGGT |

|

| R:

TCAGTTCGGGATGTGGCACAGA |

| CLDN2 | F:

GTGACAGCAGTTGGCTTCTCCA |

|

| R:

GGAGATTGCACTGGATGTCACC |

| CLDN14 | F:

CCAAGACCACCTTTGCCATCCT |

|

| R:

AGTTCTGCACCACGTCGTTGGT |

| CLDN23 | F:

CCTGGTGCGACGAGCGTTGTC |

|

| R:

GTCGCTGTAGTACTTGATGGCG |

| IL-6 | F:

AGACAGCCACTCACCTCTTCAG |

|

| R:

TTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTTGCTG |

| MMP7 | F:

TCGGAGGAGATGCTCACTTCGA |

|

| R:

GGATCAGAGGAATGTCCCATACC |

| NDRG1 | F:

ATCACCCAGCACTTTGCCGTCT |

|

| R:

GACTCCAGGAAGCATTTCAGCC |

| p53 | F:

CCTCAGCATCTTATCCGAGTGG |

|

| R:

TGGATGGTGGTACAGTCAGAGC |

| PTMS | F:

AGAAACTGCCGAGGATGGAGAG |

|

| R:

TGCCGTTTGGGATCCGCTTCAT |

| TCN1 | F:

CAGTGTGATGGAGAAAGCCCAG |

|

| R:

CCACTCAGAAGTTCCCAGTAGG |

| VDR | F:

CGCATCATTGCCATACTGCTGG |

|

| R:

CCACCATCATTCACACGAACTGG |

| ZO-1

(TJP1) | F:

GTCCAGAATCTCGGAAAAGTGCC |

|

| R:

CTTTCAGCGCACCATACCAACC |

| ZONAB

(YBX3) | F:

TGGTCCAAACCAGCCGTCTGTT |

|

| R:

GTTCTCAGTTGGTGCTTCACCTG |

| GAPDH

(RG) | F:

GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG |

|

| R:

ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA |

Relative and normalized fold

expression values calculation

The gene expression patterns of several target genes

were examined in samples from both Wt and CLDN2-KO cells

using RT-qPCR. Relative expression levels were calculated using the

comparative Cq method (ΔΔCq), normalized to GAPDH as the reference

gene (28). For every target gene,

the Cq values that were derived from the amplification curves were

used to compute ΔCq, copy number, ΔΔCq and fold change. ΔCq was

calculated using the following formula: ΔCq=Cq(target gene;

same sample)-Cq(control gene; same sample). Copy

number was calculated using the following formula: Copy number=100

× 2−ΔCq. ΔΔCq was calculated using the following

formula: ΔΔCq=ΔCq(same gene; target

sample)-ΔCq(same gene; control sample). Fold

change was calculated using the following formula: Fold

change=2−ΔΔCq.

The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as an

internal control for normalization. The expression levels of

GAPDH were relatively stable across all samples. Data are

represented as the mean of three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism software (version 8.0; Dotmatics). Data are presented as the

mean ± SEM, with at least three independent biological replicates.

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical

significance was assessed using Welch's unpaired t-test for ΔCq

values Comparisons between two groups (Wt vs. CLDN2-KO) were

made using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test if data were

normally distributed or a Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric

comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

High efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 editing

of the CLDN2 gene

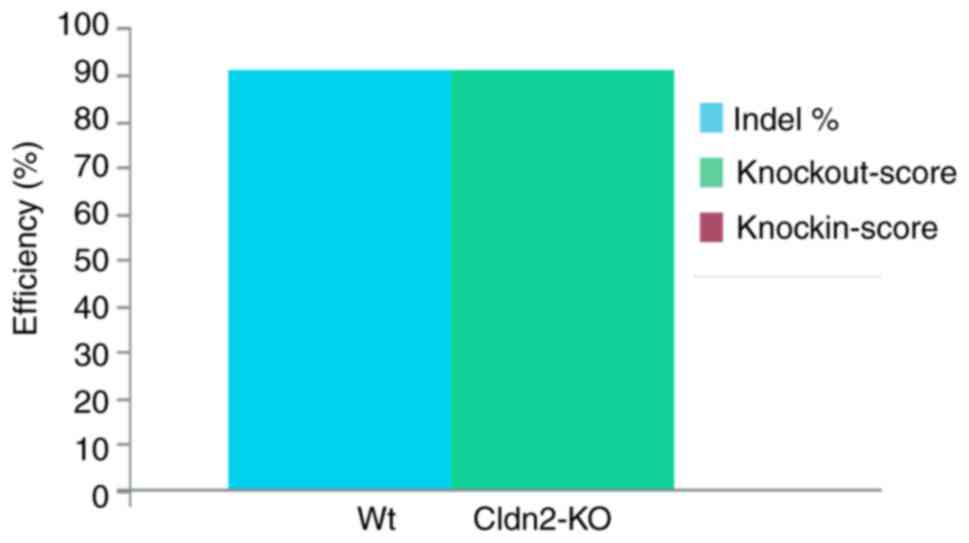

The Synthego ICE CRISPR Analysis tool was employed

to assess the effectiveness of CRISPR CLDN2 gene KO

(Fig. 1). The ICE value of 91%

indicated a high degree of editing efficiency, suggesting that a

notable proportion of the cells within the edited population

harbored the intended CLDN2 gene KO. Particularly, 91% of

cells contained the indel of the CLDN2 gene after

CRISPR/Cas9 editing.

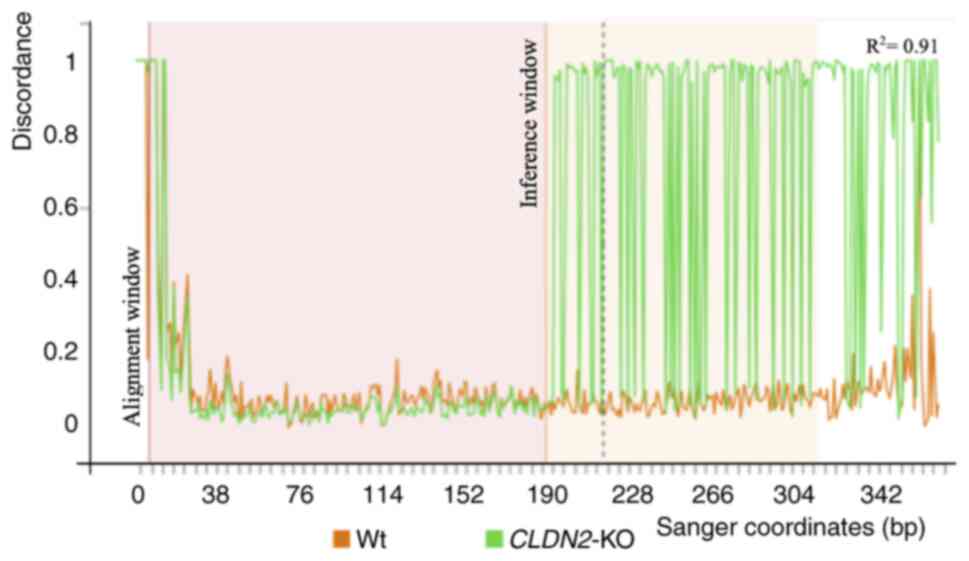

Fig. 2 presents the

Sanger sequencing discordance plot, comparing sequencing traces

from Wt and CLDN2-KO cells around the CRISPR cut site. Prior

to the cut site, the Wt and CLDN2-KO traces overlapped. At

the target site, a sharp increase in sequence discordance was

observed in CLDN2-KO cells, evidenced by the divergence

between Wt (green) and CLDN2-KO (orange) signal lines. This

pattern is characteristic of successful genome editing.

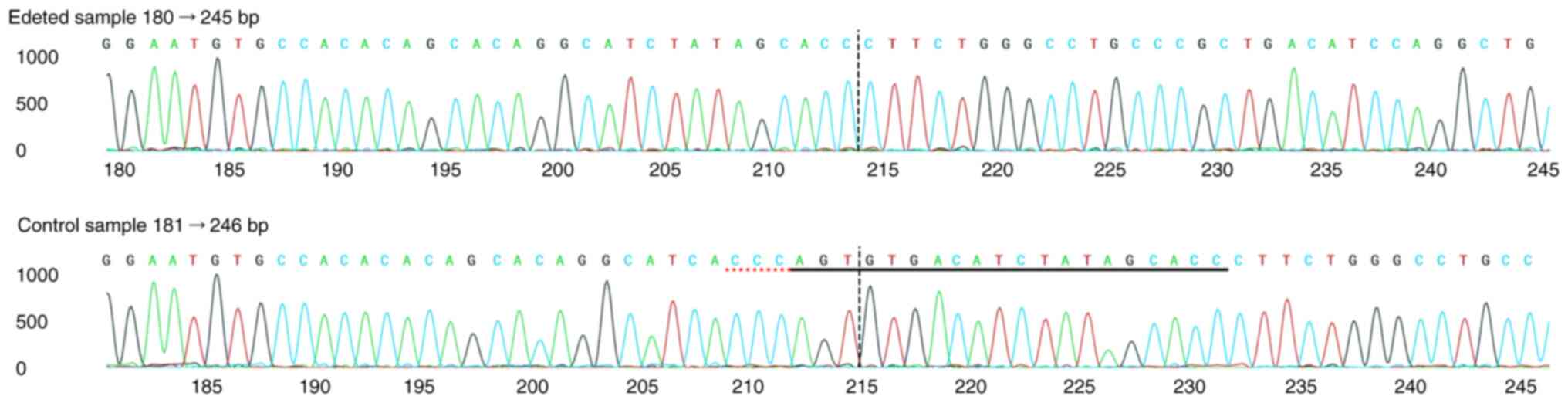

Furthermore, Fig. 3 displays the

Sanger sequence alignment surrounding the sgRNA target site, with

the sgRNA sequence underlined in black and the protospacer adjacent

motif underlined in red. A vertical line marks the cut site, where

sequence differences between Wt and CLDN2-KO cells become

evident. These results confirmed that the CLDN2 gene was

effectively knocked out in HCT116 cells with high efficiency.

Consistent with the sequencing results, qPCR analysis demonstrated

a significant reduction in CLDN2 expression in

CLDN2-KO cells relative to Wt cells (Fig. S1).

CLDN2-KO impairs HCT116 cell

migration

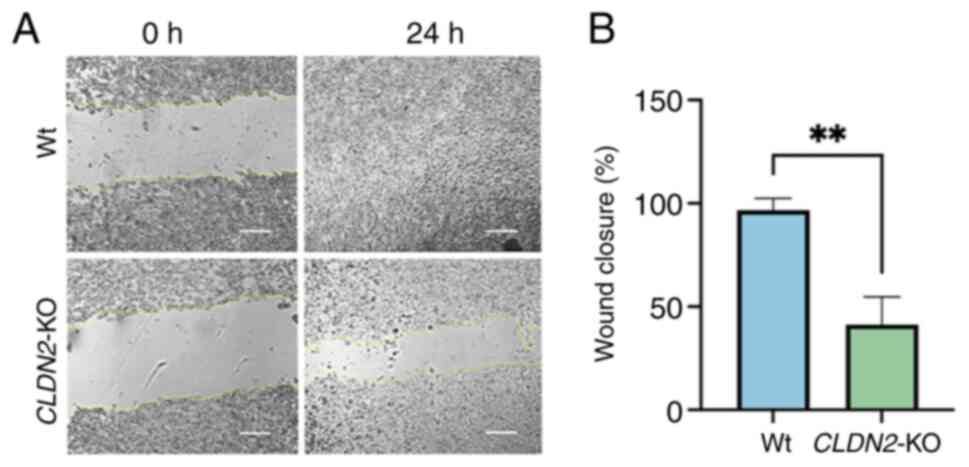

At 24 h, Wt cells exhibited near-complete wound

closure (~96%), while CLDN2-KO cells achieved only ~41%

closure. Quantification of wound healing (Fig. 4B) demonstrated a significant

reduction in migratory capacity in CLDN2-KO cells compared

with Wt controls (P=0.0027; unpaired t-test; n=3 independent

experiments). These findings indicated that CLDN2 is key for

the efficient migration of CRC cells.

Gene expression profiles in Wt and

CLDN2-KO samples

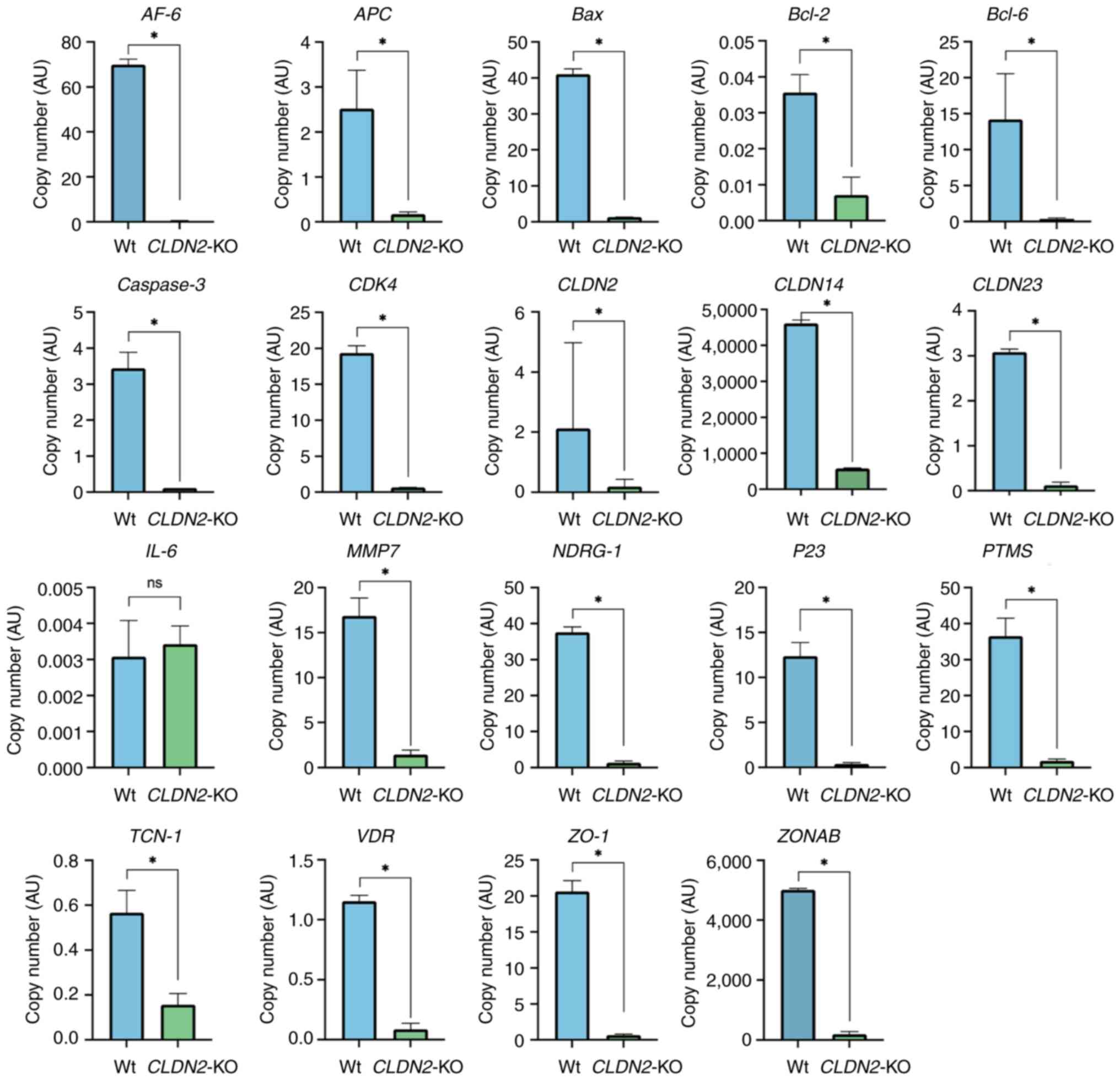

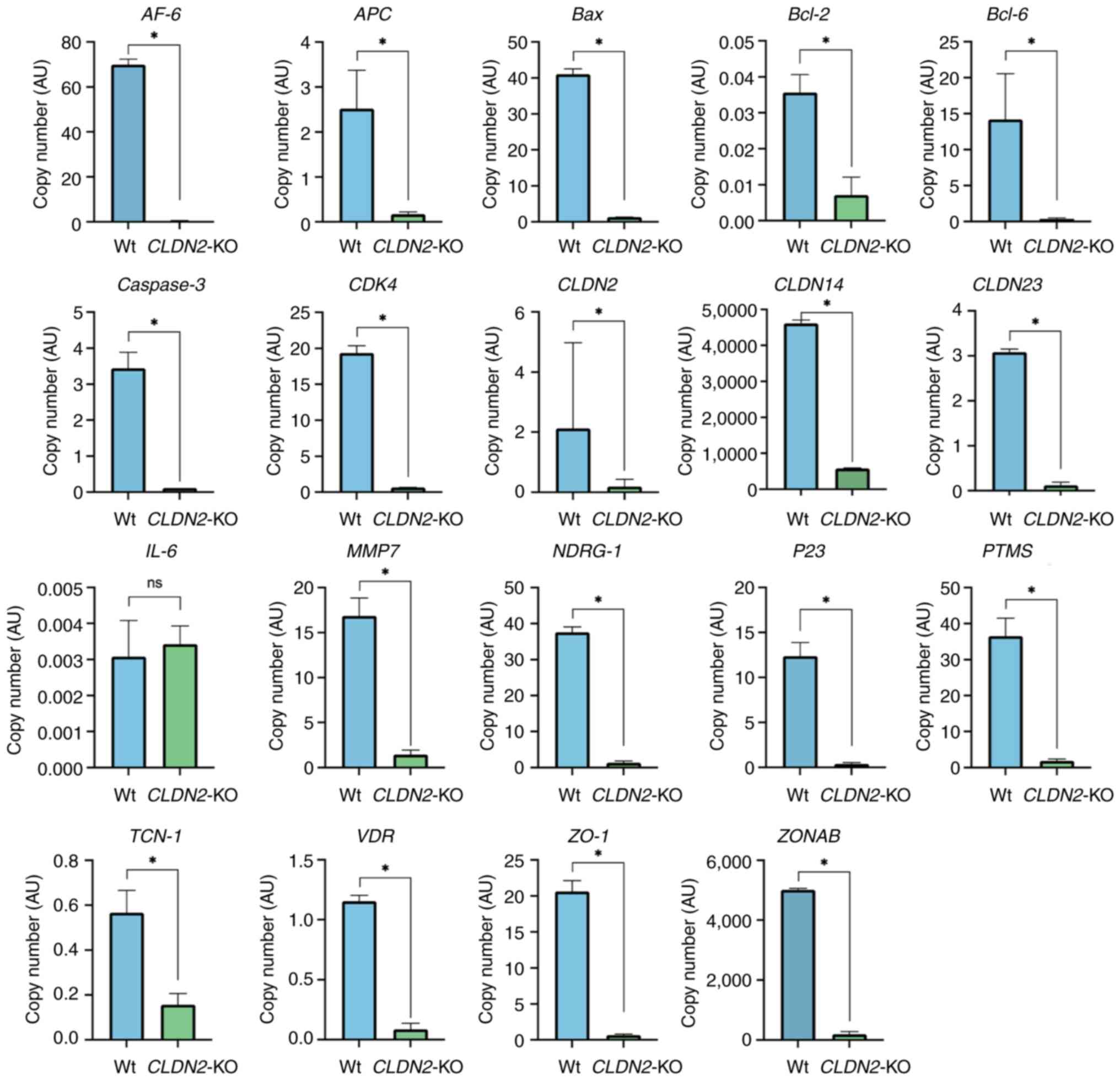

To investigate the transcriptional effects of

CLDN2 deletion, the expression levels of multiple genes

implicated in invasion and metastasis was analyzed using RT-qPCR.

Fig. 5 displays the copy numbers of

target genes in Wt and CLDN2-KO cells. Analysis of copy

number variations for all genes consistently demonstrated a

significant decrease in copy number in CLDN2-KO samples

compared with the Wt cells (all P<0.05). The observed patterns

indicated that CLDN2-KO has a notable impact on its

interacting partners, causing their downregulation.

| Figure 5.Gene expression analysis of invasion-

and metastasis-related genes in CLDN2-KO vs. Wt HCT116

cells. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR exhibited significant

downregulation of multiple target genes, including ZONAB, NDRG1,

CLDN14, CLDN23, Bcl-2, p53 and Bcl-6. Gene expression

levels were normalized to GAPDH. Data are represented as mean ± SEM

(n=3). Statistical comparisons were made using unpaired two-tailed

t-tests. *P<0.05. ns, not significant; Wt, wild-type;

CLDN2-KO, claudin-2 knock out; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1;

VDR, vitamin D receptor; ZONAB, ZO-1-associated

nucleic acid binding protein; NDRG1, N-Myc downstream-regulated

gene 1; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; AF-6/AFDN, Afadin;

TJP1, tight junction protein 1; YBX3, Y-box binding protein 3;

PTMS, parathymosin; TCN-1, transcobalamin 1. |

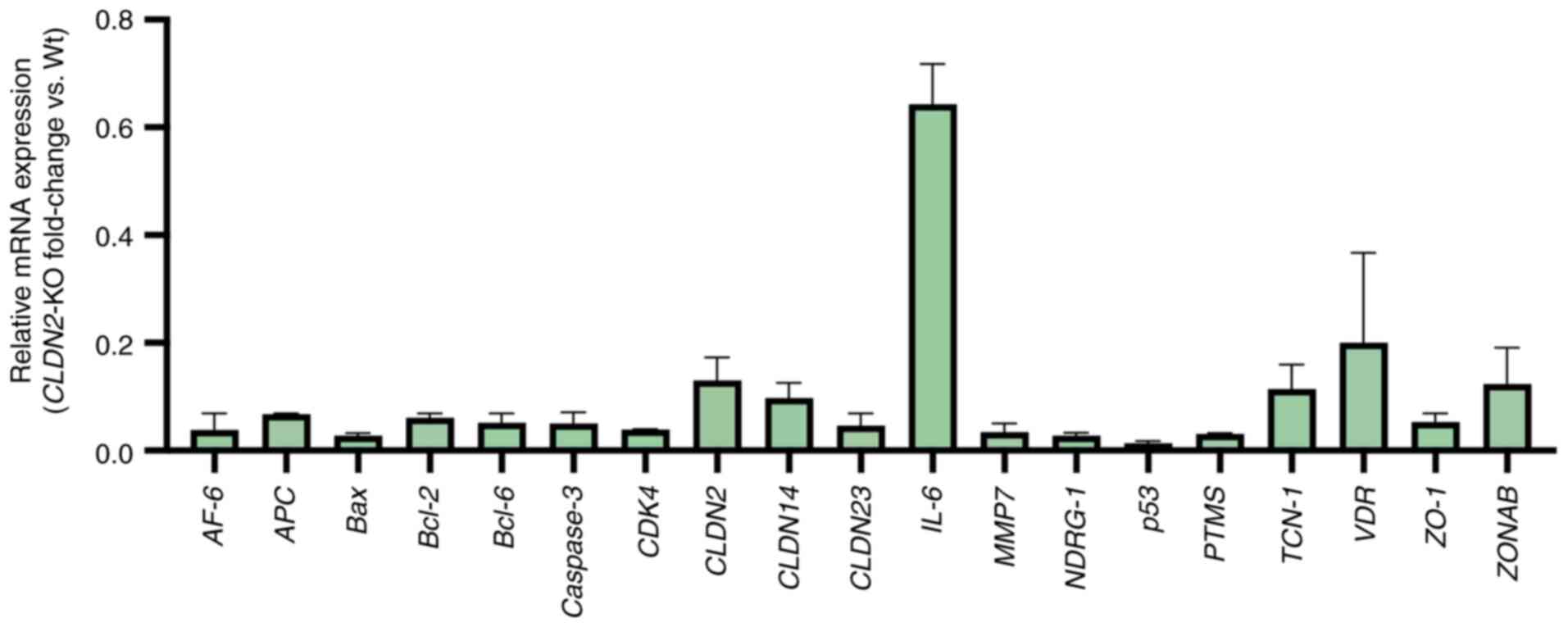

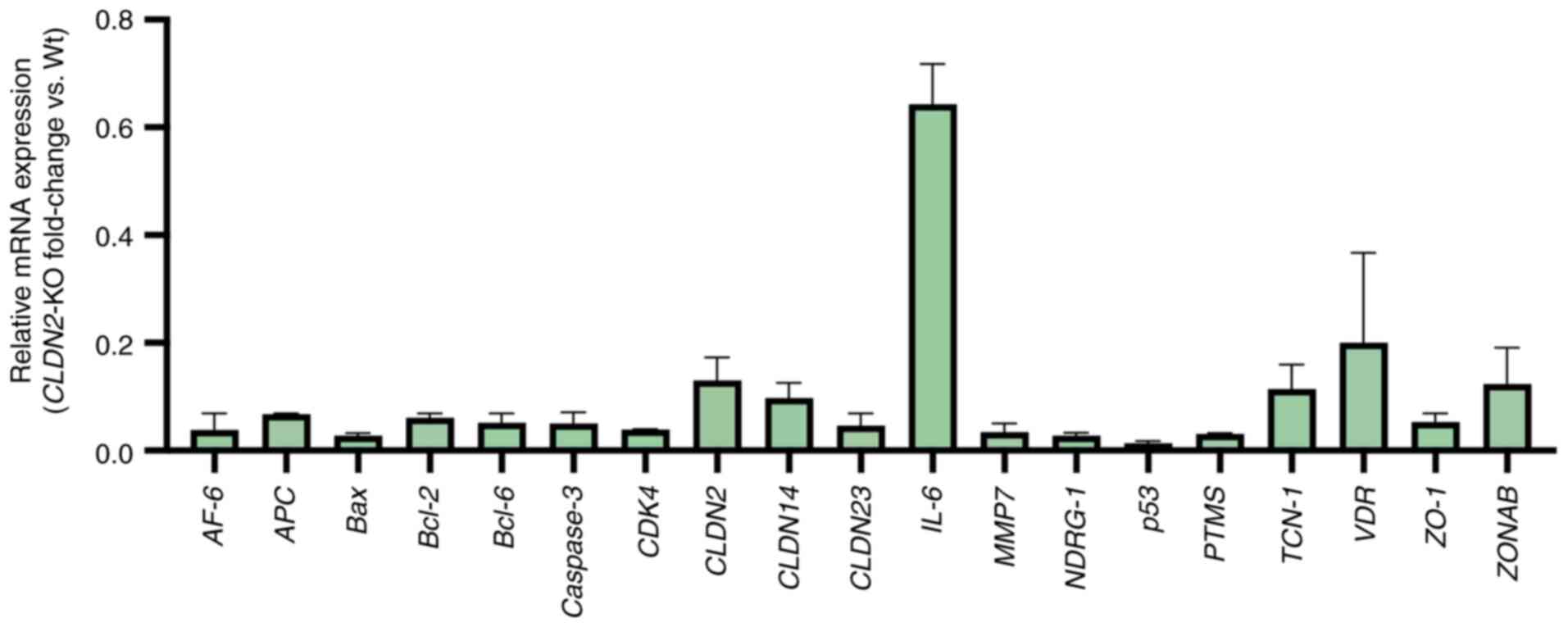

Fig. 6 depicts the

fold-change values of several genes in both Wt and CLDN2-KO

samples. Of all the genes that were evaluated, IL-6 was the

least downregulated in CLDN2-KO samples, with a fold-change

of 0.718 and maintains a relatively stable expression pattern. By

contrast, AF-6, which encodes Afadin, exhibited the most

marked downregulation, with a fold-change of 0.008. These results

suggested that CLDN2 loss disrupts a network of

pro-metastatic gene expression programs that may contribute to

impaired cellular migration and reduced metastatic potential.

| Figure 6.Relative expression levels of

metastasis-associated genes in Wt and CLDN2-KO HCT116 cells.

Gene expression was quantified using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM

of three independent experiments. Values were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method and normalized to GAPDH. Expression in Wt

cells was set to 1.0 and knock out values were expressed relative

to this baseline. Each bar corresponds to a specific gene and the

height of the bars indicates the magnitude of the fold-change

observed in the CLDN2-KO samples compared with the Wt

samples. The highest bars on the figure represent the gene with the

lowest degree of expression variation. IL-6 exhibited the

lowest degree of downregulation (fold-change, 0.718), whereas AF-6

demonstrated the most pronounced reduction (fold-change, 0.008).

Wt, wild type; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; VDR, vitamin

D receptor; ZONAB, ZO-1-associated nucleic acid binding

protein; NDRG1, N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 1; APC, adenomatous

polyposis coli; AF-6, Afadin; PTMS, parathymosin; TCN-1,

transcobalamin 1; CLDN2-KO, claudin-2 knock out; AU,

arbitrary Units. |

Discussion

Claudins are key components of tight junctions,

serving key roles in the maintenance of epithelial integrity and

regulating paracellular permeability (8). Previous studies have suggested that

claudins are involved in the development of malignancies. However,

the specific process has not yet been fully elucidated (9,29,30).

In the present study, the role of CLDN2 in

CRC progression was investigated. Using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated

CLDN2-KO in HCT116 cells, it was demonstrated that the loss

of CLDN2 leads to significant downregulation of genes

associated with invasion, metastasis and cell motility. The

findings of the present study aligned with previous studies

suggesting that CLDN2 promotes tumorigenicity and metastasis

in CRC (8–11,26,31).

Particularly, it was observed that CLDN2-KO resulted in

significantly reduced expression levels of ZONAB and NDRG1, two

factors which regulate epithelial proliferation and metastasis

suppression, respectively.

ZONAB is a Y-box transcription factor that interacts

with the tight junction protein ZO-1. When retained at tight

junctions, its transcriptional activity is restricted, whereas

nuclear translocation of ZONAB promotes the expression levels of

genes involved in proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (32,33). By contrast, NDRG1 functions as a

metastasis suppressor. It inhibits invasion and migration,

modulates epithelial differentiation and negatively regulates

oncogenic pathways such as PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin

(34,35). Downregulation of NDRG1 is

associated with poor prognosis in CRC (13). Thus, CLDN2-driven suppression

of NDRG1 through ZONAB activity provides a mechanistic

association between tight junction dysregulation and enhanced tumor

progression. These results support the hypothesis that CLDN2

may modulate the CLDN2/ZO-1/ZONAB signaling axis, thereby

influencing transcriptional programs key for cancer cell migration

and invasion (36). Previous

studies suggested that the abundance of CLDN2 increases with

cell confluence and the maturation of tight junctions and that

ZO-1 (and ZO-2) help stabilize CLDN2 by

reducing its turnover. Knockdown of ZO-1 leads to notable

loss of CLDN2 abundance and promoter activity (37). In the present study, the

downregulation of ZO-1 in CLDN2-KO cells indicated

that downstream signaling is disrupted in the absence of

CLDN2.

In addition to tight junction-related proteins,

CLDN2-KO affected the expression levels of other

metastasis-associated genes. Downregulation of CLDN14 and

CLDN23, tight junction components previously associated with

CRC progression (38,39), was observed. Furthermore, reduced

expression level of AF-6 (encoding Afadin), a scaffolding

protein involved in cell-cell adhesion and migration, was also

notable. Previous research has demonstrated that CLDN2

physically interacts with Afadin via its PDZ-binding motif and this

complex contributes to metastatic behavior in breast cancer models.

In addition, loss of Afadin impairs colony formation and metastasis

(40,41). This provides a precedent to consider

a CLDN2-Afadin axis in CRC.

Furthermore, the data in the present study revealed

a decreased expression level of CDK4, a cyclin-dependent kinase key

for cell cycle progression. Since ZONAB (regulated by CLDN2)

can associate with and influence CDK4 nuclear activity, reduced

CDK4 expression may reflect the disruption of

CLDN2/ZO-1/ZONAB signaling (32,33,42).

Collectively, these transcriptional changes highlight the broad

regulatory influence of CLDN2 on multiple pathways driving

CRC metastasis.

Notably, several key oncogenic and tumor suppressor

genes were also modulated by CLDN2 deletion. The

proto-oncogene c-Myc, a master regulator of proliferation

and metabolism, was significantly downregulated. Reduced

c-Myc expression may contribute to the suppression of

migratory and invasive phenotypes in CLDN2-deficient cells,

consistent with its role in CRC aggressiveness (43).

An inverse association between p53 and

CLDN2 has been reported in mouse colon tissue during dextran

sulfate sodium-induced colitis (44), where reduced p53 expression

was accompanied by increased CLDN2 levels, suggesting that

loss of p53-mediated regulation may contribute to

CLDN2 upregulation in inflamed and neoplastic intestinal

epithelium (45). Furthermore, a

previous study suggested a negative regulatory complex involving

p53 and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α that may influence

CLDN2 expression (44).

However, in the present study, downregulation of p53 in the

KO condition, indicated by a fold-change of 0.02, suggests that

CLDN2 may have a regulatory role in its own expression. The

reduced copy number further supports the notion of downregulation

of p53 in the CLDN2-KO cells.

A previous study provided evidence for the

qualitative and quantitative expression levels of Bcl-6

involvement in human CRC progression, and demonstrated that

Bcl-6 appears to be involved in tumor development, from the

earliest stage of carcinogenesis (46). In the present study, in the KO

condition, Bcl-6 exhibited a downregulation, indicating a

possible regulatory function for CLDN2 in its expression.

Although direct evidence of a CLDN2-Bcl-6 axis is limited,

to the best of our knowledge, perturbations in tight junction

integrity and nuclear signaling have been associated with

transcriptional repressor modulation in cancer (47,48),

suggesting that CLDN2 loss may indirectly influence

Bcl-6 expression.

Furthermore, the tumor suppressor gene adenomatous

polyposis coli (APC), a key component of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway, was markedly reduced. APC dysfunction is a

hallmark of CRC initiation and progression (49,50).

Its downregulation following CLDN2-KO highlights the complex

interplay between tight junction integrity and oncogenic pathways.

Loss of APC may also reflect feedback from junctional disruption on

Wnt signaling regulation, further implicating CLDN2 in the

modulation of oncogenic cascades. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway has been documented in a notable proportion of

gastric cancer cases. For example, nuclear β-catenin accumulation,

a hallmark of Wnt pathway activation, has been reported in ~1/3 of

gastric adenocarcinomas (51).

Recent studies estimated that 30–50% of gastric tumor specimens

exhibit hyperactivation of this pathway (52,53).

In addition, activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been

reported to increase the expression levels of MMP7 at both

the mRNA and protein levels in triple-negative breast cancer,

providing a mechanistic association between Wnt signaling and

invasive phenotypes (54,55). These findings further support the

role of Wnt pathway activation in promoting cancer progression

across multiple tumor types.

Furthermore, the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which

regulates proliferation, differentiation and epithelial barrier

function, exhibited decreased expression. Multiple studies have

indicated that VDR can directly bind and regulate

CLDN2 transcription in intestinal tissues, and that

VDR dysregulation has been implicated in colorectal

tumorigenesis (56,57). This supports a bidirectional

regulatory association between VDR and CLDN2

expression, and suggests that CLDN2 loss may contribute to

impaired VDR signaling in CRC.

Notably, elevated CLDN2 expression has been

associated with poor prognosis in CRC, liver cancer and other

gastrointestinal malignancies (7,12,58).

The findings of the present study supported this clinical

association by demonstrating that Cldn2 loss impairs migratory

potential and suppresses pro-metastatic gene expression. Thus,

targeting CLDN2 may represent a promising therapeutic

strategy to inhibit CRC metastasis in the future, although careful

evaluation of potential side effects on normal epithelial function

is warranted in future studies.

It is key to acknowledge the limitations of the

present study. While the present study results demonstrated a

strong association between CLDN2 loss and altered gene

expression, mechanistic experiments, such as rescue assays or

pathway-specific inhibition, were not performed to directly

establish causality. The findings were also based on in

vitro analyses in a single CRC cell line; validation using

in vivo models or additional cell lines in future studies

would strengthen these conclusions. Another limitation is that

CLDN2 protein loss was not validated by western blotting,

although the CRISPR editing efficiency was demonstrated by qPCR,

ICE analysis and Sanger sequencing. In addition, cell migration was

assessed only by the wound healing assay. While this method

reflects overall migratory capacity, it does not capture

chemotactic or invasive behavior. Incorporating approaches such as

Transwell migration and invasion assays would provide complementary

evidence and these are planned for future research. Lastly, further

studies are warranted to dissect the downstream mechanisms by which

CLDN2 modulates signaling pathways. Rescue experiments

restoring CLDN2 expression, pathway-specific analyses (such

as PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin and yes-associated

protein/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif) and

investigation of the interaction partners of CLDN2, such as

ZONAB and Afadin, will be key to elucidate its precise role in CRC

progression in the future.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

CLDN2 serves a key role in regulating metastasis-associated

gene networks in CRC. Disruption of CLDN2 in HCT116 cells

significantly impaired migration and was accompanied by the

downregulation of key invasion- and metastasis-related genes,

including ZONAB, NDRG1, AF-6, CLDN14, CLDN23, CDK4,

Bcl−6 and APC. These transcriptional changes

highlight the broad regulatory influence of CLDN2 on

pathways governing cell adhesion, proliferation and Wnt/β-catenin

signaling. While additional mechanistic studies, such as rescue

assays and pathway-specific analyses, are warranted to further

dissect these interactions, the present study findings provide

notable genetic and phenotypic evidence that CLDN2

contributes to CRC progression. By directly associating

CLDN2 deletion with the suppression of specific

pro-metastatic genes, the present study suggests that targeting

CLDN2 may represent a promising therapeutic strategy to

potentially inhibit CRC metastasis in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Deanship of Scientific

Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

(grant no. G: 48-665-1443).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RA conceived and designed the study. MA designed

the study. RA and MA performed experiments, analyzed and

interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. RA and MA confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA

and Jemal A: Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin.

73:233–254. 2023.

|

|

2

|

Xi Y and Xu P: Global colorectal cancer

burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol.

14:1011742021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mousavi SE, Ilaghi M, Hamidi Rad R and

Nejadghaderi SA: Epidemiology and socioeconomic correlates of

colorectal cancer in Asia in 2020 and its projection to 2040. Sci

Rep. 15:266392025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sarkar S: Proteogenomic approaches to

understand gene mutations and protein structural alterations in

colon cancer. Physiologia. 3:11–29. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tabariès S, Dupuy F, Dong Z, Monast A,

Annis MG, Spicer J, Ferri LE, Omeroglu A, Basik M, Amir E, et al:

Claudin-2 promotes breast cancer liver metastasis by facilitating

tumor cell interactions with hepatocytes. Mol Cell Biol.

32:2979–2991. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cherradi S, Ayrolles-Torro A, Vezzo-Vié N,

Gueguinou N, Denis V, Combes E, Boissière F, Busson M,

Canterel-Thouennon L, Mollevi C, et al: Antibody targeting of

claudin-1 as a potential colorectal cancer therapy. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 36:892017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tabariès S, Annis MG, Lazaris A, Petrillo

SK, Huxham J, Abdellatif A, Palmieri V, Chabot J, Johnson RM, Van

Laere S, et al: Claudin-2 promotes colorectal cancer liver

metastasis and is a biomarker of the replacement type growth

pattern. Commun Biol. 4:6572021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Venugopal S, Anwer S and Szászi K:

Claudin-2: Roles beyond permeability functions. Int J Mol Sci.

20:56552019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alghamdi RA and Al-Zahrani MH:

Identification of key claudin genes associated with survival

prognosis and diagnosis in colon cancer through integrated

bioinformatic analysis. Front Genet. 14:12218152023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Weber CR, Nalle SC, Tretiakova M, Rubin DT

and Turner JR: Claudin-1 and claudin-2 expression is elevated in

inflammatory bowel disease and may contribute to early neoplastic

transformation. Lab Invest. 88:1110–120. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Rosenthal R, Milatz S, Krug SM, Oelrich B,

Schulzke JD, Amasheh S, Günzel D and Fromm M: Claudin-2, a

component of the tight junction, forms a paracellular water

channel. J Cell Sci. 123:1913–1921. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Dhawan P, Ahmad R, Chaturvedi R, Smith JJ,

Midha R, Mittal MK, Krishnan M, Chen X, Eschrich S, Yeatman TJ, et

al: Claudin-2 expression increases tumorigenicity of colon cancer

cells: Role of epidermal growth factor receptor activation.

Oncogene. 30:3234–3247. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wei M, Zhang Y, Yang X, Ma P, Li Y, Wu Y,

Chen X, Deng X, Yang T, Mao X, et al: Claudin-2 promotes colorectal

cancer growth and metastasis by suppressing NDRG1 transcription.

Clin Transl Med. 11:e6672021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Al-Zahrani M, Lary S, Assidi M, Hakamy S,

Dallol A, Alahwal M, Al-Maghrabi J, Sibiany A, Abuzenadah A,

Al-Qahtani M and Buhmeida A: Evaluation of prognostic potential of

CD44, Claudin-2 and EpCAM expression patterns in colorectal

carcinoma. Adv Environmental Biol. 10:147–156. 2016.

|

|

15

|

Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu

VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr and Kinzler KW: Cancer genome landscapes.

Science. 339:1546–1558. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kim D and Cho KH: Hidden patterns of gene

expression provide prognostic insight for colorectal cancer. Cancer

Gene Ther. 30:11–21. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Network, .

Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal

cancer. Nature. 487:330–337. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhao Z, Li C, Tong F, Deng J, Huang G and

Sang Y: Review of applications of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing

technology in cancer research. Biol Proced Online. 23:142021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Meng H, Nan M, Li Y, Ding Y, Yin Y and

Zhang M: Application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology in

basic research, diagnosis and treatment of colon cancer. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14:11484122023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Neumann E, Schaefer-Ridder M, Wang Y and

Hofschneider P: Gene transfer into mouse lyoma cells by

electroporation in high electric fields. EMBO J. 1:841–845. 1982.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Enzmann BL and Wronski A: Synthego's

engineered cells allow scientists to ‘Cut Out’ CRISPR optimization

[SPONSORED]. CRISPR J. 1:255–257. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Roginsky J: Analyzing CRISPR editing

results: Synthego developed a tool called ICE to be more efficient

than other methods. Genet Eng Biotechnol News. 38 (Suppl):S24–S26.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow

HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL,

Bignell HR, et al: Accurate whole human genome sequencing using

reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 456:53–59. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gross A, Schoendube J, Zimmermann S, Steeb

M, Zengerle R and Koltay P: Technologies for single-cell isolation.

Int J Mol Sci. 16:16897–16919. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liang CC, Park AY and Guan JL: In vitro

scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of

cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2:329–333. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Schneider CA, Rasband WS and Eliceiri KW:

NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods.

9:671–675. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans

J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL,

et al: The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of

quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 55:611–622.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)). Method. 25:402–408. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhu L, Han J, Li L, Wang Y, Li Y and Zhang

S: Claudin family participates in the pathogenesis of inflammatory

bowel diseases and Colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Front

Immunol. 10:14412019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Al-Zahrani MH, Assidi M, Pushparaj PN,

Al-Maghrabi J, Zari A, Abusanad A, Buhmeida A and Abu-Elmagd M:

Expression pattern, prognostic value and potential microRNA

silencing of FZD8 in breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 26:4772023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ahmad R, Kumar B, Thapa I, Tamang RL,

Yadav SK, Washington MK, Talmon GA, Yu AS, Bastola DK, Dhawan P and

Singh AB: Claudin-2 protects against colitis-associated cancer by

promoting colitis-associated mucosal healing. J Clin Invest.

133:e1707712023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sourisseau T, Georgiadis A, Tsapara A, Ali

RR, Pestell R, Matter K and Balda MS: Regulation of PCNA and Cyclin

D1 expression and epithelial morphogenesis by the ZO-1-regulated

transcription factor ZONAB/DbpA. Mol Cell Biol. 26:2387–2398. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Balda MS: The tight junction protein ZO-1

and an interacting transcription factor regulate ErbB-2 expression.

EMBO J. 19:2024–2033. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kovacevic Z and Richardson DR: The

metastasis suppressor, Ndrg-1: A new ally in the fight against

cancer. Carcinogenesis. 27:2355–2366. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sun J, Zhang D, Bae DH, Sahni S, Jansson

P, Zheng Y, Zhao Q, Yue F, Zheng M, Kovacevic Z and Richardson DR:

Metastasis suppressor, NDRG1, mediates its activity through

signaling pathways and molecular motors. Carcinogenesis.

34:1943–1954. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tao D, Guan B, Li H and Zhou C: Expression

patterns of claudins in cancer. Heliyon. 9:e213382023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Amoozadeh Y, Anwer S, Dan Q, Venugopal S,

Shi Y, Branchard E, Liedtke E, Ailenberg M, Rotstein OD, Kapus A

and Szászi K: Cell confluence regulates claudin-2 expression:

Possible role for ZO-1 and Rac. Am J Physiol Physiol.

314:C366–C378. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Yang L and Zhang W, Li M, Dam J, Huang K,

Wang Y, Qiu Z, Sun T, Chen P, Zhang Z and Zhang W: Evaluation of

the prognostic relevance of differential claudin gene expression

highlights Claudin-4 as Being Suppressed by TGFβ1 inhibitor in

colorectal cancer. Front Genet. 13:7830162022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chen W, Zhu XN, Wang J, Wang YP and Yang

JL: The expression and biological function of claudin-23 in

colorectal cancer. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 49:331–336.

2018.(In Chinese).

|

|

40

|

Tabariès S, McNulty A, Ouellet V, Annis

MG, Dessureault M, Vinette M, Hachem Y, Lavoie B, Omeroglu A, Simon

HG, et al: Afadin cooperates with Claudin-2 to promote breast

cancer metastasis. Genes Dev. 33:180–193. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhang X, Wang H, Li Q and Li T: CLDN2

inhibits the metastasis of osteosarcoma cells via down-regulating

the afadin/ERK signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 18:1602018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

González-Mariscal L, Miranda J,

Gallego-Gutiérrez H, Cano-Cortina M and Amaya E: Relationship

between apical junction proteins, gene expression and cancer.

Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 1862:1832782020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Dang CV: MYC on the path to cancer. Cell.

149:22–35. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Hirota C, Takashina Y, Ikumi N, Ishizuka

N, Hayashi H, Tabuchi Y, Yoshino Y, Matsunaga T and Ikari A:

Inverse regulation of claudin-2 and −7 expression by p53 and

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α in colonic MCE301 cells. Tissue

Barriers. 9:18604092021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kim HY, Jeon H, Bae CH, Lee Y, Kim H and

Kim S: Rumex japonicus Houtt. alleviates dextran sulfate

sodium-induced colitis by protecting tight junctions in mice.

Integr Med Res. 9:1003982020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Sena P, Mariani F, Benincasa M, De Leon

MP, Di Gregorio C, Mancini S, Cavani F, Smargiassi A, Palumbo C and

Roncucci L: Morphological and quantitative analysis of BCL6

expression in human colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncol Rep.

31:103–110. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Li J: Context-dependent roles of claudins

in tumorigenesis. Front Oncol. 11:6767812021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Nehme Z, Roehlen N, Dhawan P and Baumert

TF: Tight junction protein signaling and cancer biology. Cells.

12:2432023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Miwa N, Furuse M, Tsukita S, Niikawa N,

Nakamura Y and Furukawa Y: Involvement of claudin-1 in the

beta-catenin/Tcf signaling pathway and its frequent upregulation in

human colorectal cancers. Oncol Res. 12:469–476. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Mankertz J, Hillenbrand B, Tavalali S,

Huber O, Fromm M and Schulzke JD: Functional crosstalk between Wnt

signaling and Cdx-related transcriptional activation in the

regulation of the claudin-2 promoter activity. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 314:1001–1007. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Clements WM, Wang J, Sarnaik A, Kim OJ,

MacDonald J, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Groden J and Lowy AM: Beta-Catenin

mutation is a frequent cause of Wnt pathway activation in gastric

cancer. Cancer Res. 62:3503–3506. 2002.

|

|

52

|

Chiurillo MA: Role of the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway in gastric cancer: An in-depth literature review. World J

Exp Med. 5:84–102. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Jang JH, Jung J, Kang HG, Kim W, Kim WJ,

Lee H, Cho JY, Hong R, Kim JW, Chung JY, et al: Kindlin-1 promotes

gastric cancer cell motility through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway. Sci Rep. 15:24812025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zhang N, Wei P, Gong A, Chiu WT, Lee HT,

Colman H, Huang H, Xue J, Liu M, Wang Y, et al: FoxM1 promotes

β-catenin nuclear localization and controls Wnt target-gene

expression and glioma tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 20:427–442. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Dey N, Young B, Abramovitz M, Bouzyk M,

Barwick B, De P and Leyland-Jones B: Differential activation of

Wnt-β-catenin pathway in triple negative breast cancer increases

MMP7 in a PTEN dependent manner. PLoS One. 8:e774252013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Zhang YG, Wu S, Lu R, Zhou D, Zhou J,

Carmeliet G, Petrof E, Claud EC and Sun J: Tight junction CLDN2

gene is a direct target of the Vitamin D receptor. Sci Rep.

5:106422015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Pereira F, Fernández-Barral A, Larriba MJ,

Barbáchano A and González-Sancho JM: From molecular basis to

clinical insights: A challenging future for the vitamin D endocrine

system in colorectal cancer. FEBS J. 291:2485–2518. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Mariadason JM, Nicholas C, L'Italien KE,

Zhuang M, Smartt HJM, Heerdt BG, Yang W, Corner GA, Wilson AJ,

Klampfer L, et al: Gene expression profiling of intestinal

epithelial cell maturation along the crypt-villus axis.

Gastroenterology. 128:1081–1088. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|