Introduction

Hypopharyngeal cancer (HPC) is a highly aggressive

subtype of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) developing

from the epithelial lining of the hypopharynx. In the United

States, HPC accounts for 3–5% of all head and neck malignancies and

is often diagnosed at an advanced stage due to its asymptomatic

early progression and the anatomical complexity of the hypopharynx

(1,2). Risk factors, including tobacco use,

excessive alcohol consumption and human papillomavirus infection,

contribute markedly to its pathogenesis (3,4). HPC

is clinically classified according to the TNM staging system;

early-stage disease (stage I and II) is often localized, while in

its advanced stages (stage III and IV), regional lymph node

involvement and distant metastasis are observed, leading to poor

prognosis (5). Due to the

aggressive nature of late-stage HPC, treatment strategies involve a

combination of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy; however,

five-year survival rates have been reported to be 15–45%, due to

high recurrence and resistance to therapy (6).

The progression of HPC, at the molecular level, is

driven by a complex network of signaling pathways that regulate

tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. A hallmark of HPC is

aberrant activation of the EGFR pathway, promoting uncontrolled

cell proliferation through downstream effectors such as

Ras-Raf-MEK-extracellular signal-regulated kinase and

phosphoinositide 3 kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin, which

promote tumor cell survival, proliferation and resistance to

apoptosis (7). The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, mediated by

transforming growth factor-β, Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling, is

pivotal in enhancing tumor cell motility and invasiveness (8). Therefore, angiogenesis is a key factor

supporting metastasis, driven by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

(HIF-1α) and vascular endothelial growth factor for

neovascularization, ensuring an adequate supply of oxygen and

nutrients to proliferating tumor cells (9). Increased angiogenic activity in

advanced HPC is associated with increased metastatic potential and

worse clinical outcomes (10).

Recent studies have highlighted the role of HIF-1α in promoting

metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis, contributing to tumor

progression and resistance to therapy (11,12).

Suppression of interferon (IFN) signaling has been

identified as a key mechanism of immune evasion in HPC, reducing

the susceptibility of the tumor to immune surveillance.

IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) are required for the enhancement of

immune recognition and antiviral responses, while they have been

reported to be frequently downregulated, impairing antitumor

immunity (13,14). The loss of IFN signaling not only

reduces immune-mediated tumor clearance but also promotes

resistance to immunotherapy.

The present study aimed to identify the

differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between parental FaDu HPC

cells and advanced FaDu (FaDuex) cells, which were isolated from a

late-stage xenograft tumor, were analyzed using the RNA-sequencing

(RNA-seq) technique.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The human HPC FaDu cells (cat no. HTB-43TM; American

Type Culture Collection) and FaDuex cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10%

FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1% penicillin/streptomycin

and 1% L-glutamine (both MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). The FaDu

cells were originally derived from a punch biopsy of a

hypopharyngeal tumor obtained from a 56-year-old White male patient

(15). FaDuex cells were previously

established and considered as late-stage or advanced HPC cells,

isolated from FaDu cells-derived xenograft tumors that reached

2,000 mm3 at 40 days (10). In brief, when the tumor size reached

600 mm3 exhibiting a necrotic region, the tumor was

excised and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with

high-dose antibiotics, allowing viable cells to migrate from the

tumor mass. These cells have been demonstrated to be more

tumorigenic, exhibiting an increased rate of proliferation,

angiogenesis and invasive capacity (10). The biological characteristics of

FaDuex cells closely reflect the clinical features of human HPC

diagnosed at a late stage (16).

RNA extraction and RNA-seq

analysis

RNA was extracted from cells using the GENEZol™

TriRNA Pure Kit (cat. no. GZX100; Geneaid Biotech), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Up to 5×106 cells were

harvested by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room

temperature and the culture medium was completely removed. The cell

pellet was thoroughly mixed in 700 µl of GENEzol™ reagent by

pipetting and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Ethanol was

added in a 1:1 ratio to the lysate and the mixture was processed

through a spin column-based protocol. RNA was eluted using

RNase-free water and stored at −80°C until further use. For each

condition (FaDu and FaDuex), there were two biological replicates

and RNA was independently extracted from separate cultures, and

reproducibility was ascertained. RNA library preparation and

next-generation sequencing were performed by Biotools Co., Ltd.

using their RNA-Seq (Q)20M package (service code: B-IRQTNT-E20P).

Libraries were constructed using poly(A) mRNA enrichment and

sequenced with 150 bp paired-end reads on the Illumina platform.

All samples were processed and sequenced in a single batch.

The raw sequencing reads were processed for quality

control using Trimmomatic (version 0.38) by Biotools Co., Ltd. and

assessed using FastQC and MultiQC (17,18).

Clean reads were aligned using HISAT2 to the human reference genome

(GRCh38) and read counts for each gene were quantified using

‘featureCounts’. DEGs were analyzed by comparing the transcripts

per million (TPM) values of genes between FaDuex and FaDu

samples using ‘DESeq2’ to calculate fold-changes and statistical

significance of the outcomes (19).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in ‘clusterProfiler’ (version

4.6.2, Bioconductor release 3.16) (20,21)

was performed to identify significant pathways in the Hallmark and

C2 gene sets from the Human Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB;

h.all.v2023.2.Hs and c2.all.v2023.2.Hs) (22–24),

as well as other pathways of interest, including 23 downstream NFE2

like BZIP transcription factor 2 gene sets

[Transcription_Factor_PPIs (25),

Rummagene_transcription_factors (26), TRRUST_Transcription_Factors

(27) and TRANSFAC_and_JASPAR_PWMs

(28)] (26,28,29)

and 20 cancer stem cell-related gene sets (30) collected from Enrichr (25,31,32).

Only pathways with an adjusted P<0.05, as determined by

Benjamini-Hochberg correction, were considered.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and

quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

The cDNA was synthesized using the ToolsQuant II

Fast RT kit (cat. no. KRT-BA-06; TOOLS Biotech) following the

manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after quantifying total RNA

using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), 300 ng of RNA was used as the template for

reverse transcription. Genomic DNA contamination was removed by

incubating with gDNA Eraser at 42°C for 3 min, followed by reverse

transcription at 42°C for 15 min. The resulting cDNA was diluted

with 80 µl nuclease-free water and utilized directly for subsequent

qPCR analysis employing the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Primers used

for qPCR are summarized in Table I.

Each reaction was carried out in a final volume of 20 µl,

comprising 6 µl nuclease-free water, 2 µl primer mix (6 µM forward

primer and 6 µM reverse primer), 2 µl cDNA template and 10 µl,

EnTurbo™ SYBR Green PCR SuperMix (cat. no. EQ013; High ROX

Premixed; ELK Biotechnology). The thermal cycling program was as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 20 sec, followed by 40

cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 3 sec and annealing/extension at

60°C for 30 sec, during which fluorescence signals were recorded.

At the end of the amplification reaction, the melt curve was

analyzed to confirm product specificity. The expression of each

target gene, along with the internal control gene (S26), was

analyzed in four technical replicates. Each datum represented a

mean of four repeats and was compared using unpaired t-tests.

Relative expression levels were estimated based on amplification

curves (33).

| Table I.Sequences of primers for each gene

analyzed by quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Sequences of primers for each gene

analyzed by quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| KRT13 | F:

GATGCTGAGGAATGGTTCCACG |

|

| R:

AGCTCCGTGATCTCTGTCTTGC |

| IFI44L | F:

TGCACTGAGGCAGATGCTGCG |

|

| R:

TCATTGCGGCACACCAGTACAG |

| IFI6 | F:

TGATGAGCTGGTCTGCGATCCT |

|

| R:

GTAGCCCATCAGGGCACCAATA |

| STC1 | F:

GCAGGAAGAGTGCTACAGCAAG |

|

| R:

CATTCCAGCAGGCTTCGGACAA |

| MUC16 | F:

GATGTCAAGCCAGGCAGCACAA |

|

| R:

GAGAGTGGTAGACATTTCTGGGC |

| S26 | F:

CCGTGCCTCCAAGATGACAAAG |

|

| R:

ACTCAGCTCCTTACATGGGCTT |

Results and Discussion

Analysis of DEGs between parental and

advanced HPC cells isolated from late-stage xenograft tumors

The present study first analyzed the DEGs between

FaDu and FaDuex cells (advanced FaDu cells) to identify

transcriptional differences associated with their phenotypic

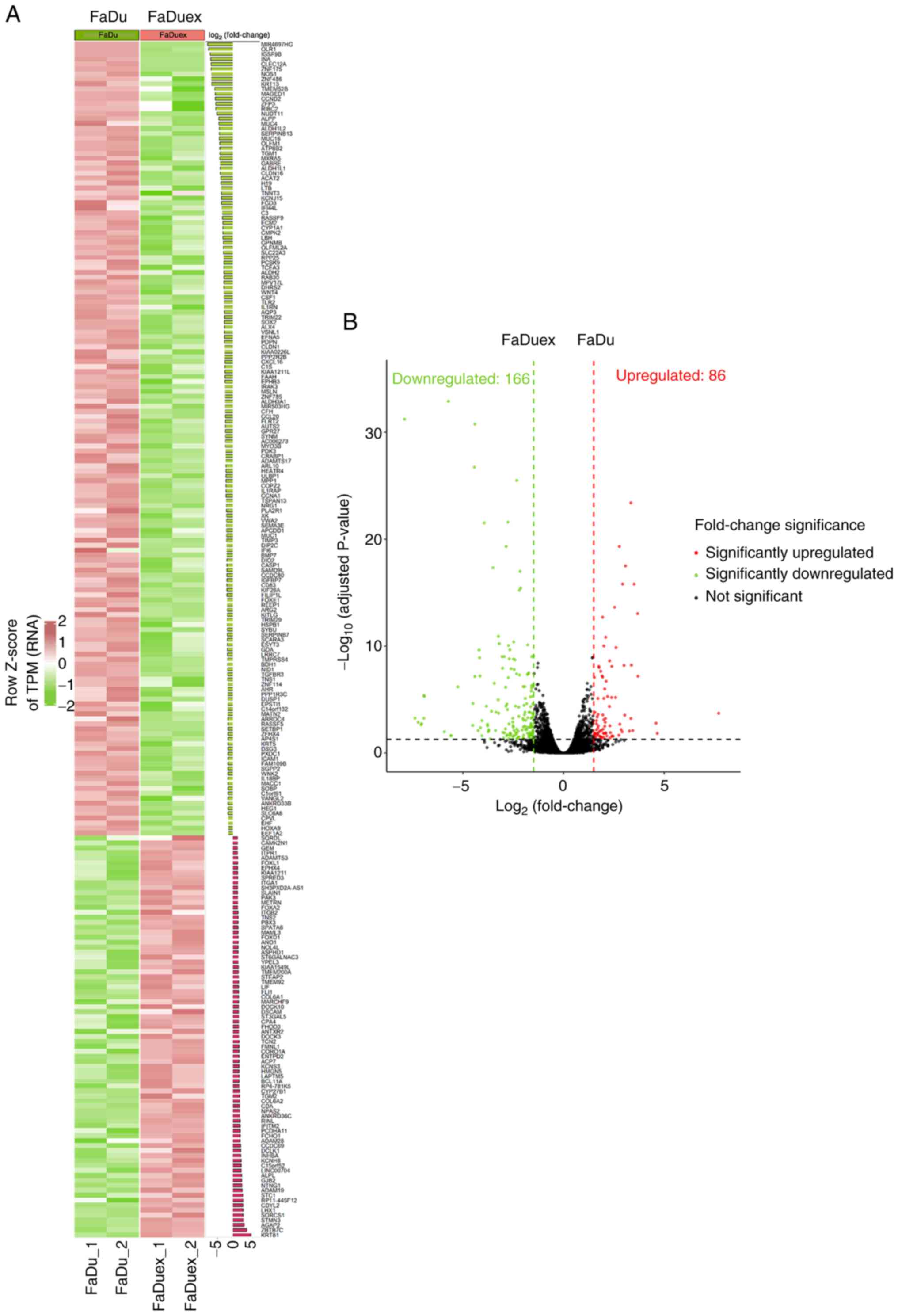

variation. The heatmap in Fig. 1A

presents distinct clustering patterns; genes upregulated in FaDuex

cells are displayed in red and the downregulated genes are

presented in green, indicating significant transcriptional

reprogramming (Fig. 1A). The

differences are further illustrated in the volcano plot (Fig. 1B). A total of 86 genes were

significantly upregulated, while 166 genes were significantly

downregulated in FaDuex cells relative to their expression in FaDu

cells (adjusted P<0.05). These findings suggest that the

expression levels of genes in FaDuex cells undergo significant

changes, potentially explaining their distinct biological

properties.

Comparison of specific signaling

pathways activated and suppressed in advanced HPC cells

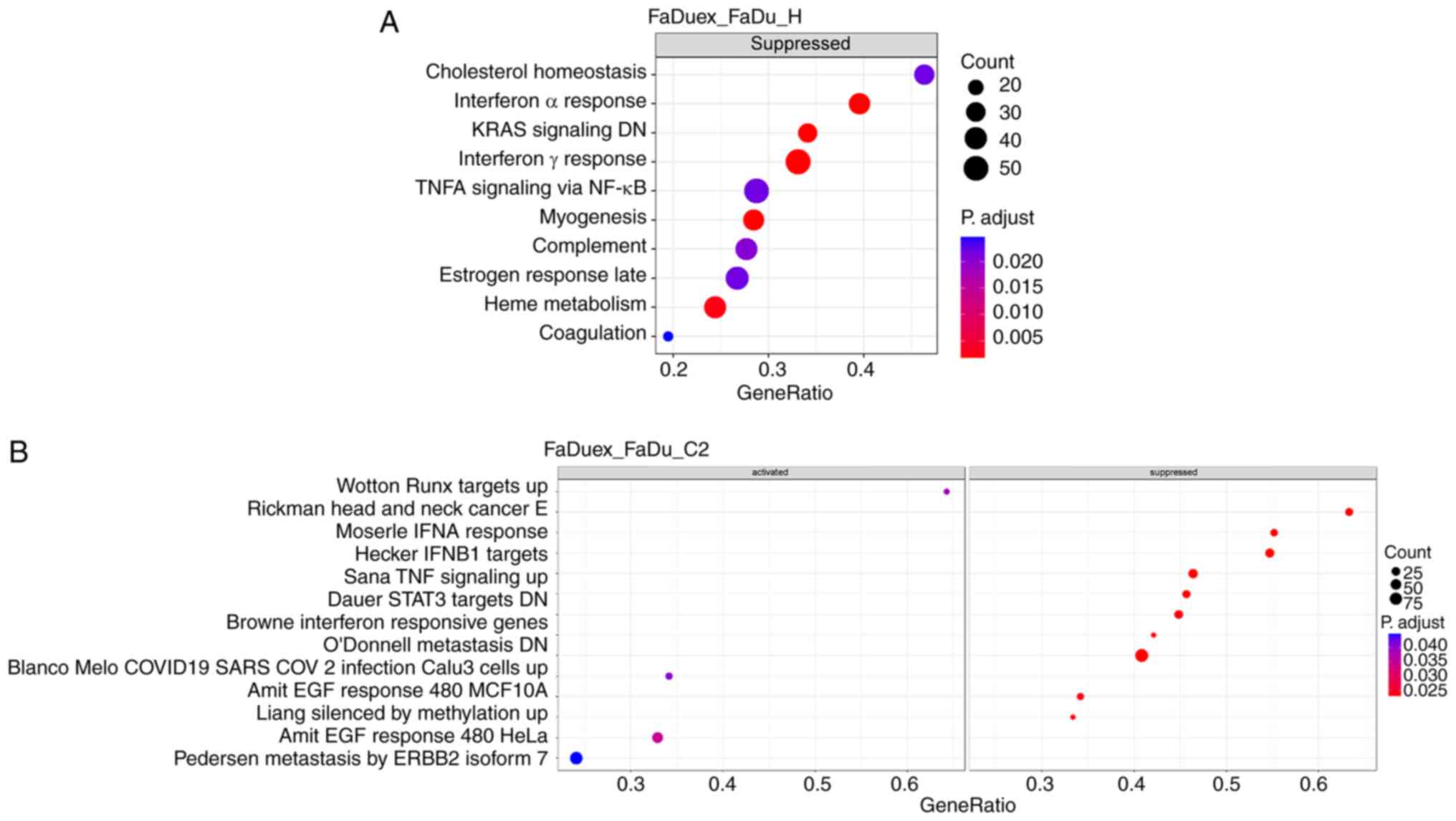

GSEA was performed next using the Hallmark and C2

gene sets to investigate the biological processes associated with

the DEGs between FaDuex and FaDu cells. Significantly enriched

pathways were subsequently categorized into activated and

suppressed groups. In the Hallmark gene set, only suppressed

enriched pathways were significant and the most suppressed pathways

included those involved in ‘IFNα response’, downregulated ‘KRAS

signaling’, ‘IFNγ response’, ‘myogenesis’ and ‘heme metabolism’

(Fig. 2A). In the C2 gene set with

significant changes, four enriched pathways (upregulated ‘Wotton

RUNX targets’, ‘AMIT EGF response’ in MCF10A and HeLa cells and

‘Pedersen metastasis by ERBB2 isoform’) were activated, while 10

pathways were suppressed, including those involved in ‘BROWNE IFN

response’ and ‘Pedersen IFN-α response’ (Fig. 2B). Since the IFN pathways are key

for antiviral defense and tumor immune surveillance (34,35),

their suppression in FaDuex cells possibly indicates an immune

evasion phenomenon, potentially facilitating tumor progression and

resistance to immune-mediated clearance. These findings highlighted

a significant suppression of IFN signaling in FaDuex cells,

potentially contributing to their altered immune landscape and

tumorigenic potential.

Gene regulations of advanced HPC cells

involved in different cancerous associated signaling pathways

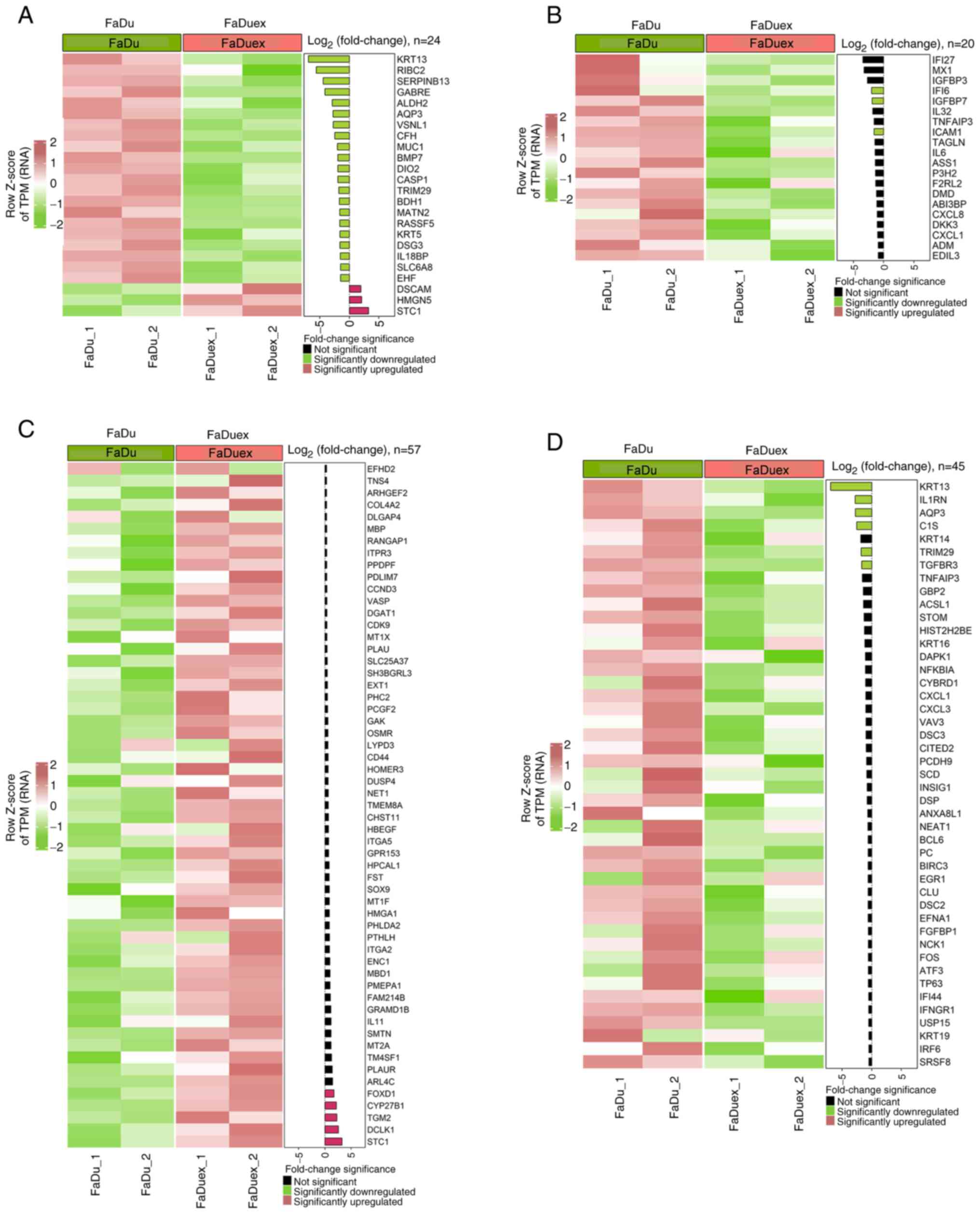

The changes in the expression levels of genes

associated with several pathways involved in metastasis,

angiogenesis, EGF signaling and EMT in FaDuex compared with FaDu

cells were further examined. Assessment of differential expression

of genes revealed that several metastasis-related genes were

altered, with keratin 13 (KRT13), RIBC2 and serpin

family B member 13 being the most significantly downregulated

metastasis-inhibiting genes, and stanniocalcin-1 (STC1),

high mobility group nucleosome binding domain 5 and down syndrome

cell adhesion molecule being the most significantly upregulated

metastasis-promoting genes, suggesting an increase in metastatic

potential in FaDuex cells (Fig.

3A). Regarding the angiogenesis pathway, only interferon

α-inducible protein 6 (IFI6), insulin-like growth factor

binding protein 7 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1

(ICAM1) were significantly downregulated

angiogenesis-inhibiting genes in FaDuex cells, indicating a

possible promotion of neovascularization (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, a significant

upregulation of STC1, doublecortin-like kinase 1,

transglutaminase 2, cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1

and forkhead box D1 genes was noted, indicating the activation of

the EGF-related pathway, which may contribute to enhanced

proliferative and survival signaling in FaDuex cells (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the genes involved

in the inhibition of the EMT pathway, including KRT13,

interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, aquaporin-3, complement

component 1s, tripartite motif-containing protein 29 and

transforming growth factor-β receptor 3, were downregulated in

FaDuex cells, suggesting a shift toward EMT phenotypes (Fig. 3D). These findings indicated that

FaDuex cells exhibit enhanced metastatic, angiogenic, proliferative

and EMT-related potential, reflecting a more aggressive

phenotype.

Downregulation of interferon

signaling-associated genes in advanced HPC cells

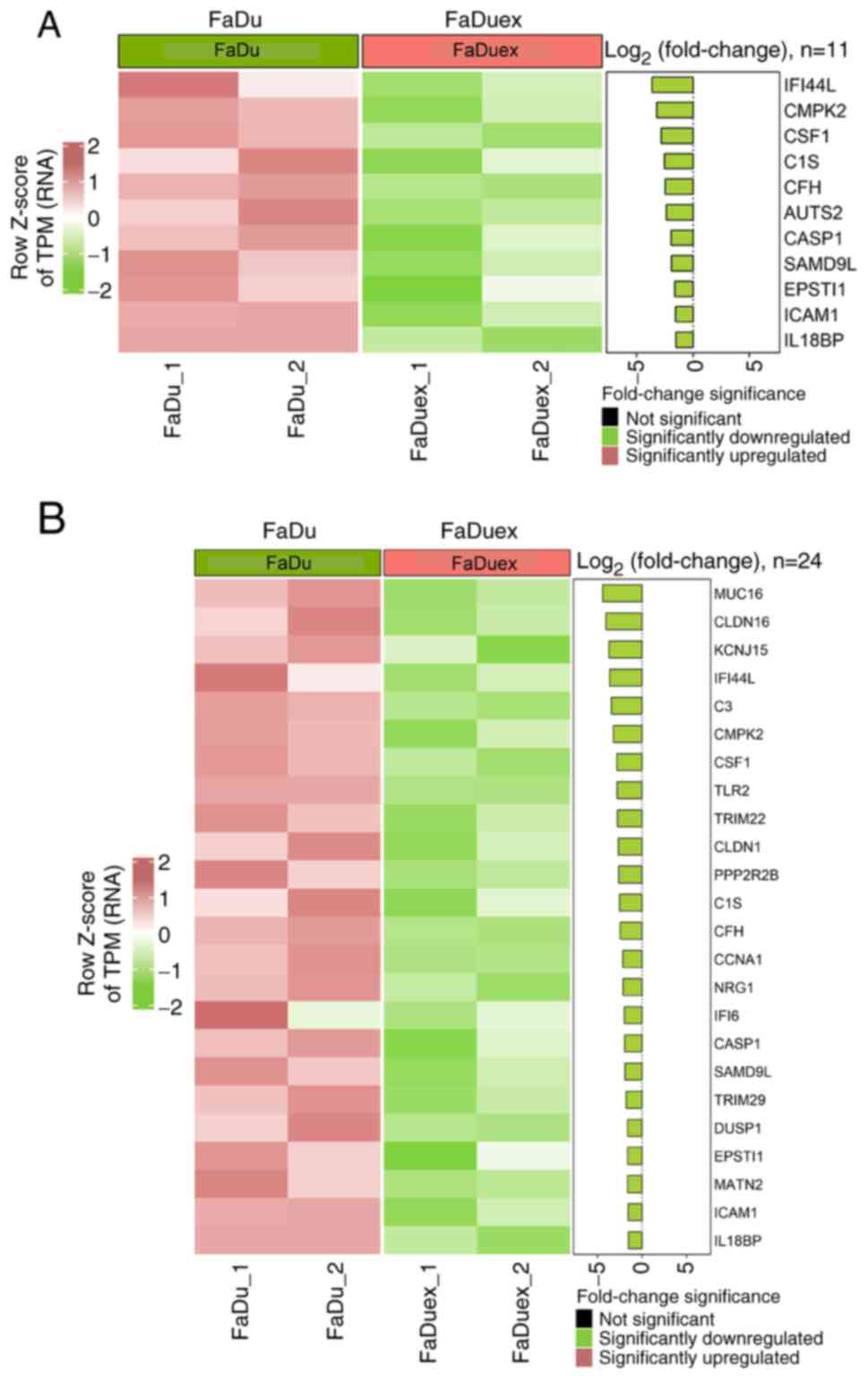

The present study analyzed the expression of

IFN-responsive genes using the C2 and Hallmark gene sets to

evaluate the differences in IFN signaling between FaDu and FaDuex

cells. Both analyses revealed a broad suppression of ISGs in FaDuex

cells, indicating a significant suppression of IFN signaling. In

the C2 gene set (Fig. 4A), key ISGs

such as interferon-induced protein 44-like (IFI44L),

IFI6 and tripartite motif-containing protein 22, all of

which are key mediators of the IFN response and antiviral defense

mechanisms, were markedly downregulated. The Hallmark gene set

(Fig. 4B) further confirmed the

suppression of IFN signaling, demonstrating a decrease in the

expression of genes such as IFI44L, caspase-1 and

ICAM1, which are involved in immune activation and

inflammatory responses. In the Hallmark gene set, mucin-16

(MUC16) was the most significantly downregulated; however,

its expression was only stimulated by the combined action of tumor

necrosis factor-α and IFN-γ (36).

The downregulation of these ISGs suggested that FaDuex cells may

have reduced sensitivity to IFN-mediated immune responses,

potentially altering their interaction with the immune

microenvironment and affecting their ability to respond to external

immune challenges.

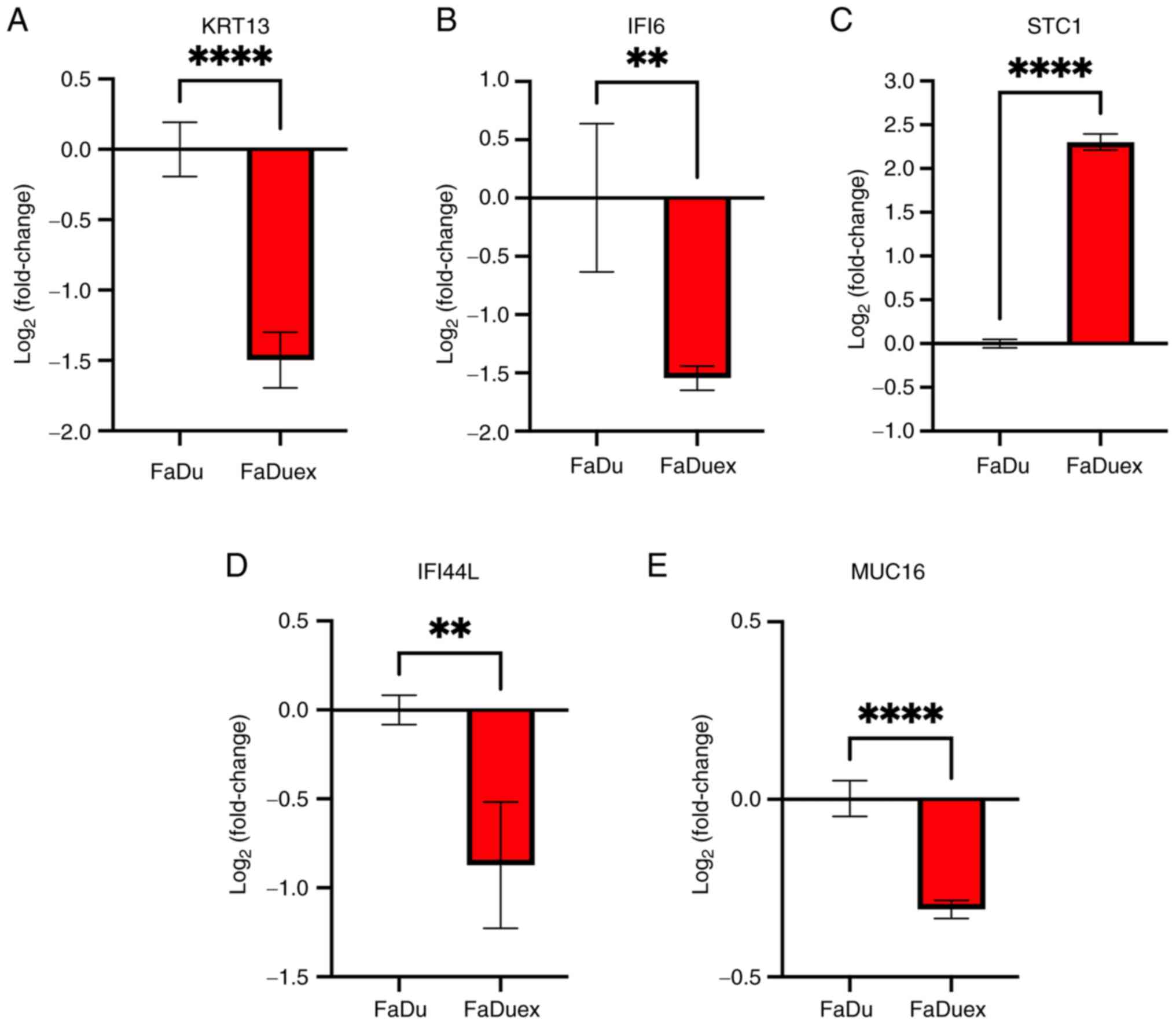

Validation of gene expression using

qPCR

The results of DEGs analysis were validated by

performing qPCR by selecting genes, in FaDu cells and FaDuex cells,

whose expression levels exhibited the most significant changes.

According to the DEGs analysis, KRT13 and IFI6 were

most significantly downregulated in metastasis/EMT and

angiogenesis, respectively, whereas STC1 was the most

significantly upregulated in proliferative and survival-related

gene of FaDuex cells. In addition, IFI44L and MUC16

were most downregulated in the IFN-responsive genes of FaDuex cells

according to the C2 and Hallmark gene sets. The qPCR analysis

further demonstrated the downregulation of KRT13, IFI44L,

IFI6 and MUC16 transcripts (Fig. 5A, B, D and E) and STC1 was

upregulated in FaDuex cells (Fig.

5C), consistent with DEG analysis. These results suggested that

RNA-seq determined gene expression is useful for the prediction of

cancer-related signaling pathways.

The limitations of the present study include a small

sample size; in addition, the results were analyzed from human HPC

cell lines rather than clinical samples. As mentioned, HPC is a

rare subtype of HNSCC (6). In

Taiwan, the age-standardized incidence rate for HPC was increased

from 1980 and reached 6.46 per 100,000 in 2019 (37). A pilot study may be initiated in the

future to determine notable changes of gene expression using a

widely used HPC cell line and its derivatives from xenograft tumor.

FaDu cells are isolated from the primary tumor of a White male

patient with HPC in 1968 (15).

Recently, another HPC cell type (CZH1) isolated from a Chinese

patient with HPC has been reported, exhibiting a greater capacity

for invasion and increased radiosensitivity compared with FaDu

cells (38). The present study

would be key in exploring the gene expression differences of

patients with HPC from different ethnicities. FaDuex cells are

isolated from xenograft tumors that have reached 2,000

mm3 and the present study defined them as late-stage

tumors because of increased metastatic, tumorigenic, angiogenic and

chemoradiotherapy-resistant capacity (10). However, it is difficult to explain

the TNM stage of clinical HPC through late-stage FaDuex cells, as

they exhibit similar characteristics as advanced human HPC

diagnosed in clinics. In addition, the translational limitation may

still exist when using FaDuex cells to represent late-stage HPC in

clinical settings. Another limitation of the present study was the

use of parental FaDu cells for comparison with tumor-derived FaDuex

cells rather than the early stage of FaDu tumors (for example,

tumor size at 100 mm3). It may be key to compare potent

DEGs in FaDu-derived xenograft tumors at the early (small size)

stage and the late (large size) stage in the future.

To conclude, the present study demonstrated that

FaDuex cells, the arbitrarily defined late-stage HPC cells isolated

from xenograft tumors, exhibited several genes - including

KRT13, IFI6, STC1, MUC16 and IFI44L - that were

differentially expressed and were associated with malignant

characteristics, including increased metastasis, angiogenesis,

proliferation and decreased inflammatory responses. The present

study also observed that RNA-seq data-based DEGs analysis could be

validated using qPCR. Although the use of human cell lines may

encounter several of the aforementioned limitations, the variation

in samples would be low and easy to interpret. The present study

results suggest that several genes are associated with the advanced

malignancy of HPC cells, which makes this information potentially

key for diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in the

future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant of Taipei City

Hospital, RenAi Branch (grant no. TPCH-112-12) and that of National

Science and Technology Council (grant no. NSTC

114-2314-B-A49-065-MY3).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of National Library of Medicine

under accession no. PRJNA1282043 or at the following URL:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1282043.

Authors' contributions

CWK conducted the cell culture experiments, RNA

preparation, RNA-sequencing arrangement and data analysis. YPY

conducted the differential gene expression and gene set enrichment

analyses. TWC, JDL and YJL confirmed the authenticity of all the

raw data. TWC interpreted the RNA sequencing data, and resolved

questions related to the accuracy of this work. MYL isolated and

identified different types of FaDu cells. JDL and YJL contributed

to the conception and the design of the present study. YJL drafted

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Petersen JF, Timmermans AJ, van Dijk BAC,

Overbeek LIH, Smit LA, Hilgers FJM, Stuiver MM and van den Brekel

MWM: Trends in treatment, incidence and survival of hypopharynx

cancer: A 20-year population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur

Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 275:181–189. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cordunianu AV, Ganea G, Cordunianu MA,

Cochior D, Moldovan CA and Adam R: Hypopharyngeal cancer trends in

a high-incidence region: A retrospective tertiary single center

study. World J Clin Cases. 11:5666–5677. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sanders O and Pathak S: Hypopharyngeal

Cancer. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL:

2025

|

|

4

|

Patel EJ, Oliver JR, Jacobson AS, Li Z, Hu

KS, Tam M, Vaezi A, Morris LGT and Givi B: Human papillomavirus in

patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg. 166:109–117. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rami-Porta R, Nishimura KK, Giroux DJ,

Detterbeck F, Cardillo G, Edwards JG, Fong KM, Giuliani M, Huang J,

Kernstine KH Sr, et al: The International association for the study

of lung cancer lung cancer staging project: Proposals for revision

of the TNM stage groups in the forthcoming (Ninth) Edition of the

TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 19:1007–1027.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bozec A, Benezery K, Chamorey E, Ettaiche

M, Vandersteen C, Dassonville O, Poissonnet G, Riss JC,

Hannoun-Lévi JM, Chand ME, et al: Nutritional status and

feeding-tube placement in patients with locally advanced

hypopharyngeal cancer included in an induction chemotherapy-based

larynx preservation program. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

273:2681–2687. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Malecki K, Glinski B, Mucha-Malecka A, Rys

J, Kruczak A, Roszkowski K, Urbańska-Gąsiorowska M and Hetnał M:

Prognostic and predictive significance of p53, EGFr, Ki-67 in

larynx preservation treatment. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 15:87–92.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang J, Tian XJ and Xing J: Signal

transduction pathways of EMT Induced by TGF-beta, SHH, and WNT and

their crosstalks. J Clin Med. 5:412016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ahluwalia A and Tarnawski AS: Critical

role of hypoxia sensor-HIF-1α in VEGF gene activation. Implications

for angiogenesis and tissue injury healing. Curr Med Chem.

19:90–97. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lin MY, Wang CY, Chan YH, Su SP, Chiang

HK, Yang MH and Lee YJ: The emergence of tumor-initiating cells in

an advanced hypopharyngeal tumor model exhibits enhanced

angiogenesis and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

2-associated antioxidant effects. Antioxid Redox Signal.

41:505–521. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Taneja N, Chauhan A, Kulshreshtha R and

Singh S: HIF-1 mediated metabolic reprogramming in cancer:

Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Life Sci. 352:1228902024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhong X, Wang Y, He X, He X, Hu Z, Huang

H, Chen J, Chen K, Wei P, Zhao S, et al: HIF1A-AS2 promotes the

metabolic reprogramming and progression of colorectal cancer via

miR-141-3p/FOXC1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 15:6452024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Meyer SP, Bauer R, Brune B and Schmid T:

The role of type I interferon signaling in myeloid anti-tumor

immunity. Front Immunol. 16:15474662025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Critchley-Thorne RJ, Yan N, Nacu S, Weber

J, Holmes SP and Lee PP: Down-regulation of the interferon

signaling pathway in T lymphocytes from patients with metastatic

melanoma. PLoS Med. 4:e1762007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Rangan SR: A new human cell line (FaDu)

from a hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 29:117–121. 1972.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Keski-Santti H, Luukkaa M, Carpen T,

Jouppila-Matto A, Lehtio K, Maenpaa H, Vuolukka K, Vahlberg T and

Mäkitie A: Hypopharyngeal carcinoma in Finland from 2005 to 2014:

Outcome remains poor after major changes in treatment. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 280:1361–1367. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S and Kaller

M: MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and

samples in a single report. Bioinformatics. 32:3047–3048. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kim D, Langmead B and Salzberg SL: HISAT:

A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods.

12:357–360. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2:1001412021.

|

|

21

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H,

Ghandi M, Mesirov JP and Tamayo P: The molecular signatures

database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst.

1:417–425. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R,

Thorvaldsdottir H, Tamayo P and Mesirov JP: Molecular signatures

database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 27:1739–1740. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK,

Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub

TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP: Gene set enrichment analysis: A

knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression

profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:15545–15550. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD,

Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM,

Lachmann A, et al: Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment

analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:W90–W97.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Clarke DJB, Marino GB, Deng EZ, Xie Z,

Evangelista JE and Ma'ayan A: Rummagene: Massive mining of gene

sets from supporting materials of biomedical research publications.

Commun Biol. 7:4822024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Han H, Cho JW, Lee S, Yun A, Kim H, Bae D,

Yang S, Kim CY, Lee M, Kim E, et al: TRRUST v2: An expanded

reference database of human and mouse transcriptional regulatory

interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:D380–D386. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Rauluseviciute I, Riudavets-Puig R,

Blanc-Mathieu R, Castro-Mondragon JA, Ferenc K, Kumar V, Lemma RB,

Lucas J, Chèneby J, Baranasic D, et al: JASPAR 2024: 20th

anniversary of the open-access database of transcription factor

binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 52:D174–D182. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Han H, Cho JW, Lee S, Yun A, Kim H, Bae D,

et al: TRRUST v2: an expanded reference database of human and mouse

transcriptional regulatory interactions. Nucleic Acids Res.

46:D380–D386. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hu C, Li T, Xu Y, Zhang X, Li F, Bai J,

Chen J, Jiang W, Yang K, Ou Q, et al: CellMarker 2.0: An updated

database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web

tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D870–D876.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Xie Z, Bailey A, Kuleshov MV, Clarke DJB,

Evangelista JE, Jenkins SL, Lachmann A, Wojciechowicz ML,

Kropiwnicki E, Jagodnik KM, et al: Gene set knowledge discovery

with enrichr. Curr Protoc. 1:e902021. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z,

Meirelles GV, Clark NR and Ma'ayan A: Enrichr: Interactive and

collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC

Bioinformatics. 14:1282013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Bonjardim CA, Ferreira PC and Kroon EG:

Interferons: Signaling, antiviral and viral evasion. Immunol Lett.

122:1–11. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kaplan DH, Shankaran V, Dighe AS, Stockert

E, Aguet M, Old LJ and Schreiber RD: Demonstration of an interferon

gamma-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:7556–7561. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Morgado M, Sutton MN, Simmons M, Warren

CR, Lu Z, Constantinou PE, Liu J, Francis LL, Conlan RS, Bast RC Jr

and Carson DD: Tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-ү stimulate

MUC16 (CA125) expression in breast, endometrial and ovarian cancers

through NFĸB. Oncotarget. 7:14871–14884. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Tsai YS, Chen YC, Chen TI, Lee YK, Chiang

CJ, You SL, Hsu WL and Liao LJ: Incidence trends of oral cavity,

oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancers among males in

Taiwan, 1980–2019: A population-based cancer registry study. BMC

Cancer. 23:2132023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ma J, Zhu X, Heng Y, Ding X, Tao L and Lu

L: Establishment and characterization of a novel hypopharyngeal

squamous cell carcinoma cell line CZH1 with genetic abnormalities.

Hum Cell. 37:546–559. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|