Introduction

Cancer is a multifactorial disease due to various

causes and impacts, such as environmental factors, infectious

agents, genetic alterations and epigenetic shifts (1,2).

Advances in genetic research have not only elucidated the

pathogenesis of several cancer types, such as acute myeloid

leukemia (AML), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and prostate

cancer (PCa), but have also directly contributed to the development

of treatments (3–6). For example, imatinib is an effective

treatment for leukemia caused by mutations in the breakpoint

cluster region-Abelson, offering the possibility of long-term

disease remission. Furthermore, <2% of the entire genome encode

proteins, while the rest of the genetic material is composed of

non-coding genes, which are key contributors to tumorigenesis among

multiple cancer types, such as PCa and colorectal cancer (CRC)

(7–9).

Transcripts >200 nucleotides in length and which

have little or no ability to code for proteins are termed long

non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) (10,11).

Previous studies identified that several dysregulated lncRNAs

contribute to the development and progression of cancer types,

working as oncogenes or tumor suppressors (12–15).

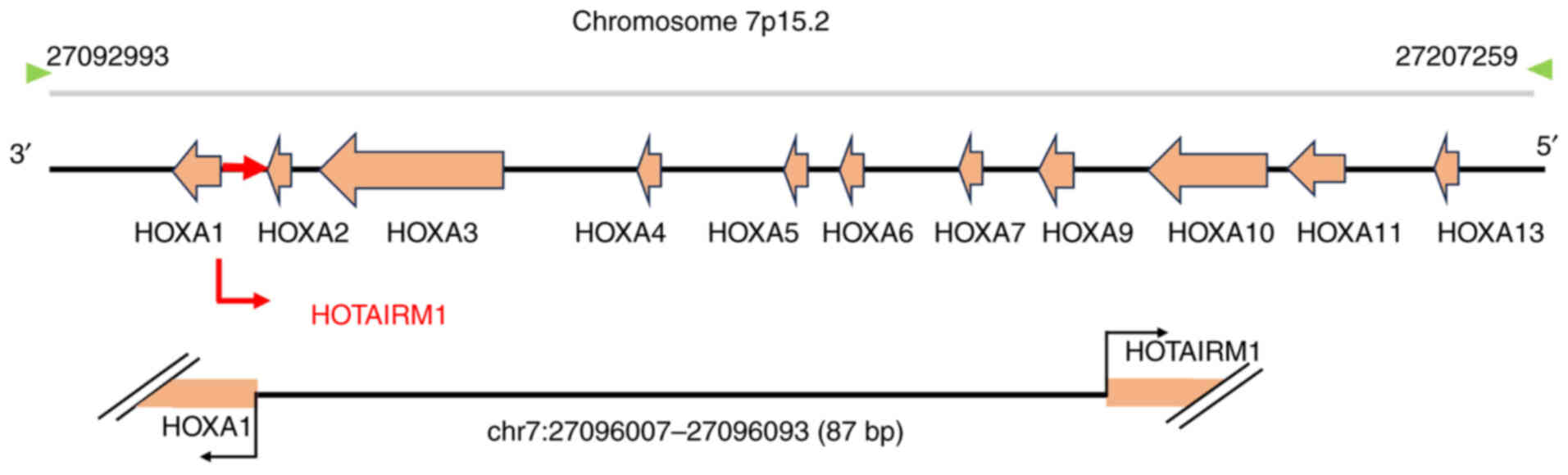

HOTAIRM1 is a recently identified lncRNA located in the HOXA gene

cluster on the human chromosome 7p15.2 (Fig. 1) (16). HOTAIRM1 was first identified as

involved in the differentiation of granulocytes in the NB4

promyelocytic leukemia model (17).

Since its identification, HOTAIRM1 has gained notable attention in

cancer research (18–20).

The relevant studies in the present review were

collected using PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) with a combination of

the following terms: ‘HOTAIRM1’, ‘cancer’, ‘tumor’ and ‘disease’.

English-language publications from the past 10 years were selected.

Two reviewers (YJ and XL) independently performed an initial

screening of titles and abstracts. The reference lists of

potentially eligible articles were cross-checked to ensure

extensive coverage of the literature. A total of 103 articles

meeting the predefined literature searching criteria were

identified by May 2025.

Therefore, the present review provides a

comprehensive overview of the current understanding of the

expression, roles and molecular mechanisms of HOTAIRM1 to regulate

cancer.

HOTAIRM1 expression in cancer

Several previous studies have documented the

abnormal expression of lncRNAs in different diseases, particularly

in cancer (21–23). The dysregulation of lncRNAs

contributes to the development of tumors through the promotion,

proliferation, invasion and metastasis of cancer cells (24–26).

The lncRNA HOTAIRM1 is upregulated in different types of cancer

such as glioma (27–35), AML (36–38),

osteosarcoma (OS) (39),

endometrial cancer (EC) (40),

thyroid cancer (TC) (41,42), NSCLC (43,44),

oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (45), PCa (46), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

(PDAC) (47,48) and ovarian cancer (OC) (49,50).

The involvement of HOTAIRM1 in governing tumor characteristics,

including proliferation, invasion and metastasis, has been

demonstrated. However, HOTAIRM1 expression is downregulated in

papillary TC (PTC) (51), head and

neck tumor (HNT) (52),

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (53), lung adenocarcinoma (ADC) (54), gastric cancer (GC) (55,56)

and CRC (Table I) (57,58).

These collective findings position HOTAIRM1 as a key tumor-related

lncRNA, whose dysregulation could drive oncogenic pathways and

offers a promising target for future cancer interventions.

| Table I.HOTAIRM1 expression in several cancer

types. |

Table I.

HOTAIRM1 expression in several cancer

types.

| Cancer type | Expression | Functions | Associated

genes | Role | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Glioma | Up | Migration,

invasion, VM formation, proliferation, stemness and

radiosensitivity | IGFBP2, FUS, HOXAs,

miR-133b-3p, miR-137, miR-153-5p and TGM2 | Oncogene | (27–35) |

| AML | Up | Autophagy,

proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle and differentiation | EGR1, miR-152-3p

and miR-148b | Oncogene | (36–38) |

| OS | Up | Proliferation,

apoptosis | miR-664b-3p | Oncogene | (39) |

| EC | Up | Proliferation,

migration, invasion and EMT | HOXA1 | Oncogene | (40) |

| TC | Up | Proliferation,

apoptosis, migration and invasion | ILF3, pri-miR-144

and miR148a | Oncogene | (41,42) |

| NSCLC | Up | Proliferation,

apoptosis, migration, invasion and glycolysis metabolism | miR-498 | Oncogene | (43,44) |

| OSCC | Up | Proliferation and

cell cycle | PCNA, cyclin D1,

p53, p21, CDK4 and CDK6 | Oncogene | (45) |

| PCa | Up | Proliferation and

apoptosis | β-catenin | Oncogene | (46) |

| PDAC | Up | Proliferation,

apoptosis, cell cycle and migration | CDK1, cyclin D1,

p21, Bax, Bad and Bcl-2 | Oncogene | (47,48) |

| OC | Up | Proliferation and

apoptosis | MMP2 | Oncogene | (49) |

| PTC | Down | Proliferation,

migration and invasion | miR-107 | Anticancer | (51) |

| OC | Down | Proliferation

invasion and apoptosis | miR-106a-5p | Anticancer | (50) |

| HNT | Down | Proliferation,

apoptosis, migration and invasion | miR-148a | Anticancer | (52) |

| HCC | Down | Proliferation and

apoptosis | β-catenin | Anticancer | (53) |

| ADC | Down | Cell cycle,

proliferation and invasion | miR-498 | Anticancer | (54) |

| GC | Down | Proliferation,

migration and apoptosis | miR-29b-1-5p and

miR-17-5p | Anticancer | (55,56) |

| CRC | Down | Invasion, migration

and multi-drug resistance | miR-17-5p | Anticancer | (57,58) |

HOTAIRM1 expression in glioma

Glioma is the most common primary central nervous

system tumor (59). Several

previous studies have reported a notable increase in HOTAIRM1

expression in glioblastoma tissues and cell lines when compared

with their normal counterparts (27–32).

Glioblastoma tissues and cells exhibit an abnormal HOTAIRM1

upregulation, which promotes glioma malignancy by enhancing cell

proliferation, migration, invasion and VM formation. The high

HOTAIRM1 expression is mediated by METTL3-dependent m6A

modification (33). Furthermore,

Snail family transcriptional repressor 2 transcriptionally

activated HOTAIRM1 and a strong association was observed between

increased HOTAIRM1 expression and worse prognosis in glioma

(34). HOTAIRM1 is also strongly

associated with decreased survival rates of patients diagnosed with

glioblastoma (35).

HOTAIRM1 expression in AML

AML is a heterogeneous disease characterized by

genetic irregularities (including mutations in genes like FLT3,

NPM1 and RUNX1) and epigenetic alterations (such as mutations in

regulators of DNA methylation like DNMT3A, TET2 and IDH1/2)

(60,61). Jing et al (36) observed that HOTAIRM1 expression was

increased in 14 AML samples with nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) mutations

when compared with AML samples without NPM1 mutations. This finding

suggested a potential functional link between HOTAIRM1 and this

specific genetic irregularity, implying that HOTAIRM1 upregulation

may be part of the oncogenic machinery in NPM1-mutated AML.

Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis on patients with AML

demonstrated a notably reduced survival time in the group with high

HOTAIRM1 expression. A different investigation demonstrated that

the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells with all-trans

retinoic acid led to an increase in HOTAIRM1 expression, which is

key to myeloid differentiation. Notably, the transcription factor

PU.1 binds to a specific DNA site (+1,100) in the promoter of the

HOTAIRM1 gene, therefore activating it and increasing its

expression (37). Furthermore, Hu

et al (38) demonstrated

that HOTAIRM1 expression is increased in patients with AML compared

with individuals without the disease. The functional analysis

indicated that HOTAIRM1 downregulation inhibits the growth and

triggers cell death in AML cells, indicating its tumorigenic

function in AML.

HOTAIRM1 expression in OS

OS is a prevalent and aggressive form of primary

bone cancer that mostly affects children and teenagers (62). HOTAIRM1 expression is markedly

increased in both OS samples and cell lines compared with their

non-cancerous counterparts. The association between HOTAIRM1

expression and the clinicopathological features of patients with OS

revealed that individuals with high HOTAIRM1 expression are prone

to having an advanced TNM stage (as defined by the American Joint

Committee on Cancer, 8th edition) (63). HOTAIRM1 upregulation stimulates the

growth and movement of cells while inhibiting cell death. These

findings suggest that HOTAIRM1, a cancer-causing gene in OS,

potentially holds promise in the identification and management of

this disease (39).

HOTAIRM1 expression in EC

In the female reproductive system, EC ranks as one

of the top three prevalent malignancies (64). Li et al (40) identified markedly higher HOTAIRM1

expression in type I EC tissues compared with normal endometrium

tissues and showed it is associated with the clinicopathological

features of affected patients. The increased expression of HOTAIRM1

is also strongly associated with advanced International Federation

of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage (according to the FIGO

staging system, 2023 edition) (65)

and the presence of lymph node metastasis. The suppression of

HOTAIRM1 inhibits the growth, movement, infiltration of type I EC

cells, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and tumor growth

in vivo (40).

HOTAIRM1 expression in TC

TC is divided into three main histological groups:

i) Differentiated TC, which includes papillary, follicular and

oncocytic carcinomas; ii) medullary TC, often associated with

multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndrome; and iii) anaplastic

TC, an aggressive malignancy that often arises from pre-existing

differentiated lesions and is characterized by a high mortality

rate (66,67). Zhang et al (41) reported that HOTAIRM1 gene is

amplified and its expression is increased in anaplastic TC compared

with PTC and normal thyroid tissue. Furthermore, patients with

anaplastic TC indicating higher HOTAIRM1 copy number and expression

have worse survival outcomes. The role of HOTAIRM1 in TC appears to

be complex and potentially context-dependent. While one study by Li

et al (42) reported that

elevated HOTAIRM1 expression in TC cells and tissues was associated

with advanced TNM stage and lymph node metastasis, another

investigation found contrary evidence, demonstrating that HOTAIRM1

expression was notably reduced in PTC tissues and that lower levels

correlated with lymph node metastasis and more advanced disease

(51). This discrepancy highlights

the need for further research to clarify the precise function of

HOTAIRM1 in TC progression.

HOTAIRM1 expression in NSCLC

NSCLC is responsible for ~85% of cancer-related

mortality globally, making it the primary contributor to lung

cancer mortalities worldwide (68).

Chen et al (43) observed

that HOTAIRM1 expression is markedly increased in NSCLC tissues

compared with tissues of a control group. A different study

demonstrated that HOTAIRM1 expression is associated with tumor

histological differentiation, tumor size, TNM stage and Ki-67

expression in patients with NSCLC. Furthermore, HOTAIRM1 expression

is increased in NSCLC compared with that in adjacent non-cancerous

tissues. Patients with NSCLC with low HOTAIRM1 expression have a

markedly longer overall survival compared with those with high

expression (44).

HOTAIRM1 expression in OSCC

OSCC is a malignant tumor with the highest

occurrence rate among tumors affecting mouth and face. OSCC is well

known for its tendency to recur and spread to other parts of the

body (69,70). Yu et al (45) reported that HOTAIRM1 expression is

increased in OSCC and it is closely associated with poor prognosis.

Systematic bioinformatics analyses revealed that HOTAIRM1 is

associated with tumor stage, overall survival, genomic instability,

tumor cell stemness, tumor microenvironment activity and immunocyte

infiltration.

HOTAIRM1 expression in PCa

PCa is a major contributor to cancer-associated

mortality among men, particularly in Western countries, with Africa

and Asia having the lowest incidence rates (71,72).

Wang et al (46) reported

that HOTAIRM1 expression is increased in PCa cells. The inhibition

of HOTAIRM1 expression prevents tumor cell proliferation while

inducing programmed cell death through the modulation of proteins

associated with apoptosis. The inhibition of HOTAIRM1 expression

limits the activity of the Wnt pathway in PCa cells, thereby

suppressing the malignant characteristics of tumor cells.

HOTAIRM1 expression in PDAC

PDAC is the most common form of PCa arising from the

epithelial lining of the pancreatic duct (73). Samples of 47 PDAC tissues and 5 cell

lines exhibit an abnormal increase of HOTAIRM1 expression compared

with its expression in a control group (47). Similarly, Zhou et al

(48) reported that HOTAIRM1

expression is increased in 12 PDAC tissue samples when compared

with the corresponding non-tumor samples.

HOTAIRM1 expression in OC

OC is the eighth most common type of cancer among

women worldwide and is the third most frequent gynecological cancer

after cervical cancer and EC (74).

Ye et al (49) reported an

overexpression of HOTAIRM1 in the human ovarian cancer cell line

SKOV3. Inhibition of HOTAIRM1 expression reduces cell proliferation

and increases cell death. Chao et al (50) observed that HOTAIRM1 expression is

reduced in both ovarian cancer tissues and cells and advanced FIGO

stage and lymphatic metastasis are associated with reduced HOTAIRM1

expression. HOTAIRM1 overexpression inhibits the growth and

invasion of OC cells, while enhancing apoptosis. Furthermore,

HOTAIRM1 slows OC tumor growth in vivo.

HOTAIRM1 expression in head and neck

cancer

Head and neck cancer is a frequently diagnosed form

of cancer globally, with an annual incidence of >600,000 new

cases (75,76). Zheng et al (52) reported that HOTAIRM1 expression is

decreased in 43 head carcinoma tissues and 41 neck carcinoma

tissues when compared with the corresponding adjacent normal

tissues. Furthermore, no association was identified between

HOTAIRM1 expression and age, sex or tumor location. However,

patients with increased HOTAIRM1 expression have a higher

probability to develop an advanced TNM stage, suggesting that

although HOTAIRM1 is generally downregulated in head and neck

cancer, tumors that maintain a relatively higher expression

(although still lower compared with normal tissues) are associated

with increased malignancy and progression.

HOTAIRM1 expression in HCC

HCC is classified as the sixth most prevalent tumor

and the third main reason of cancer fatality (77). Zhang et al (53) reported that HOTAIRM1 expression is

lower in HCC tissues compared with that in the adjacent

non-cancerous tissues. Furthermore, the receiver operating

characteristic curve demonstrated that HOTAIRM1 expression so a

notable level of sensitivity and specificity in detecting HCC. The

absence of disease progression in patients with HCC is associated

with tumor size and HOTAIRM1 expression. However, no association

was observed with age, sex, γ-glutamyl transferase levels,

α-fetoprotein levels, Child-Pugh grade (as defined by the American

Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines)

(78), hepatitis B surface antigen

status, presence of cirrhosis, number of tumors, micro-vessel

metastasis, tumor differentiation and TNM stage of HCC.

HOTAIRM1 expression in ADC

Among NSCLCs, ADC is one of the key histological

subtypes with high incidence and mortality (79,80).

Thus, current studies on HOTAIRM1 primarily focus on ADC rather

than other NSCLC subtypes, such as squamous cell carcinoma or large

cell carcinoma. Chen et al (54) reported a notable decrease in

HOTAIRM1 expression in ADC tissues compared with that in normal

lung tissues. A clear association exists between the decrease of

HOTAIRM1 expression and clinical stage, metastasis to lymph nodes

and tumor size. Furthermore, HOTAIRM1 inhibition is associated with

poor overall survival in patients with ADC, as demonstrated by the

Kaplan-Meier analysis.

HOTAIRM1 expression in GC

GC is a prevalent malignancy worldwide. GC ranks as

the second most prevalent form of cancer in China and ranks as the

third leading cause of cancer-associated mortality (81). Xu et al (55) identified a notable decrease of

HOTAIRM1 expression in GC tissues is associated with a low survival

rate among patients with GC. These findings are consistent with

those reported by Lu et al (56) suggesting a marked decrease in

HOTAIRM1 expression in 20 gastric cancer tissues and cell lines.

Furthermore, HOTAIRM1 expression is associated with the

clinicopathological features of patients with GC and a strong

association exists between decreased HOTAIRM1 expression and

advanced TNM stage as well as lymph node metastasis.

HOTAIRM1 expression in CRC

CRC is one of the most prevalent malignancies

worldwide, with particularly high incidence in Western countries

(82,83). Wan et al (57) reported that HOTAIRM1 expression is

reduced in CRC tissues compared with that in normal tissues.

Furthermore, in the matched cohort, plasma HOTAIRM1 levels were

markedly lower in patients with CRC compared with those in healthy

controls. Ren et al (58)

identified a similar scenario where HOTAIRM1 expression is

downregulated in both CRC tissues and cell lines and is even lower

in 5-fluorouracil (FU)-resistant CRC tissues and cell lines. This

progressive downregulation in resistant tissues and cell lines

strongly implied that the loss of HOTAIRM1 is a key event in the

acquisition of chemoresistance, consistent with its established

role in suppressing cancer progression through mechanisms such as

the miR-17-5p/BTG3 axis (58).

Mechanisms involved in the regulation of

HOTAIRM1

LncRNAs interact with DNA, RNA or proteins as

molecular absorbers, frameworks and stimulators, exerting

regulatory functions in different biological processes, including

gene regulation, cellular differentiation and human diseases,

particularly cancer (84–88). HOTAIRM1 is involved in normal and

abnormal biological processes. Several molecular functions have

been identified after years of research and they are categorized

into three primary pathways: i) Interaction with DNA; ii)

interaction with RNA; and iii) interaction with proteins.

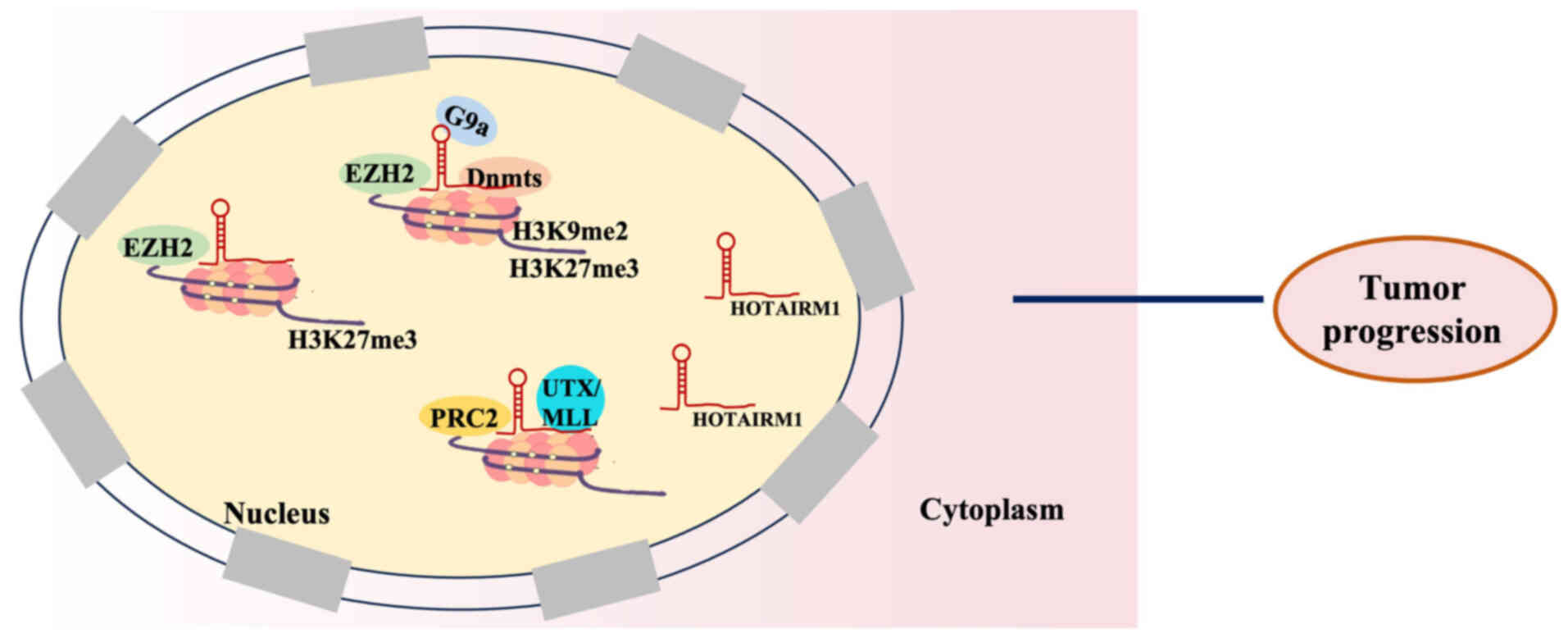

Interaction with DNA

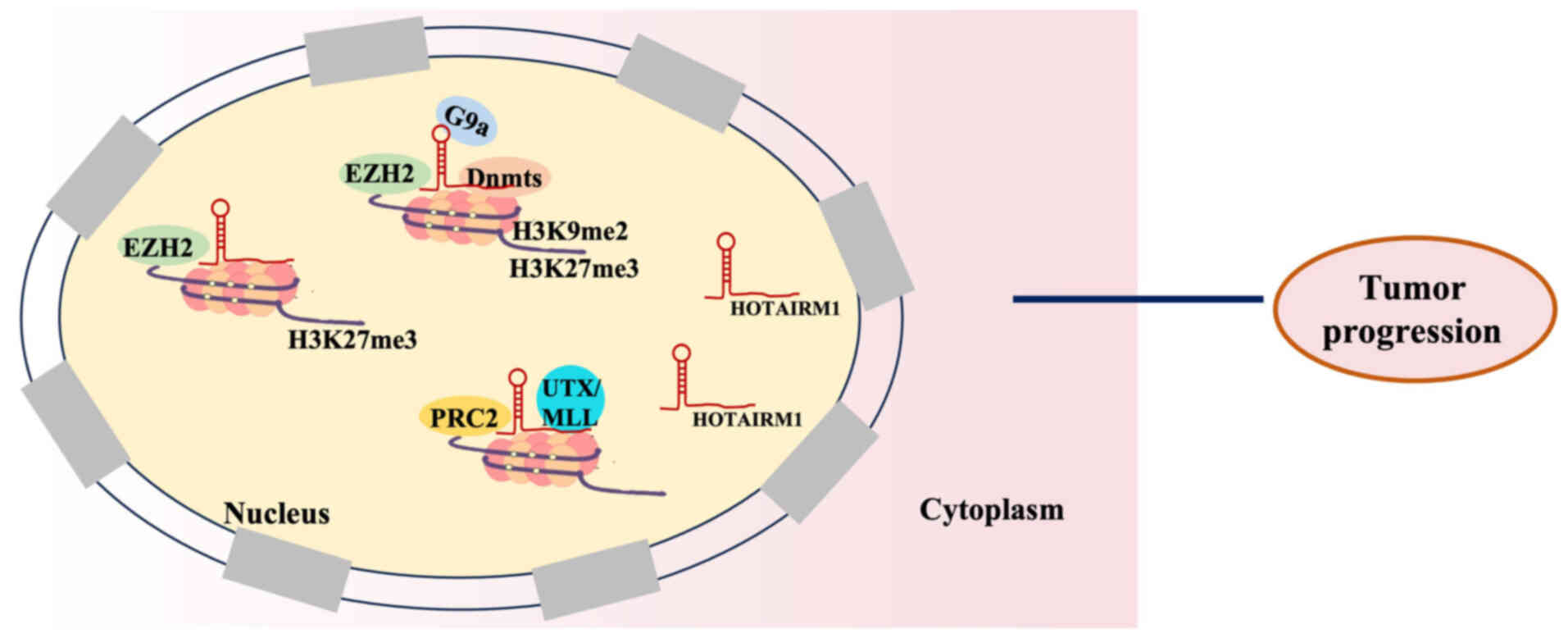

HOTAIRM1 is involved in the methylation alteration

of several genes that are associated with tumors and in the

modification of histones (Fig. 2).

HOTAIRM1 controls gene expression through its interaction with

polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which consists of enhancer of

zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), suppressor of zeste 12 homolog and

embryonic ectoderm development protein. HOTAIRM1 catalyzes the

dimethylation and trimethylation of the histone 3 lysine residue 27

(H3K27me3), thus controlling the expression of its gene. Li et

al (89) identified that

HOTAIRM1 triggers the transcription of the homeobox A1 (HOXA1) gene

by reducing the levels of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) dimethylation,

H3K27me3 and DNA methylation, which are markers associated with the

suppression of gene expression. HOTAIRM1 prevents the recruitment

of histone H3K9 methyltransferase, EZH2 and DNA methyltransferases

to the HOXA1 promoter during its interaction with them, thereby

reducing their local abundance at this site (89). Kim et al (90) reported that HOTAIRM1 directly

interacts with EZH2, the histone methyltransferases responsible for

H3K27me3 trimethylation, thereby preventing the deposition of

H3K27me3 marks at the putative HOXA1 promoter. Therefore, HOXA1

expression is increased in ER+ breast cancer cells.

Furthermore, HOTAIRM1 interacts with the histone demethylases PRC2

and ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat on chromosome

X/mixed lineage leukemia to control chromatin structure and

subsequently impacts the transcriptional activity of the HOXA gene

cluster (91).

| Figure 2.HOTAIRM1 interaction with DNA to

exert a regulatory role in tumor progression. Interaction with

PRC2/EZH2: HOTAIRM1 directly interacts with EZH2 of the PRC2

complex, preventing the deposition of the repressive H3K27me3 mark

at target gene promoters; Interaction with H3K9 methyltransferases

and DNMTs: HOTAIRM1 binds to and prevents the recruitment of H3K9

methyltransferases and DNA methyltransferases to promoters, thereby

reducing repressive H3K9me2 and DNA methylation. Interaction with

histone demethylases: HOTAIRM1 interacts with histone demethylases

to help control chromatin structure and activate transcription of

target gene cluster. HOTAIRM1, HOXA transcript antisense RNA

myeloid-specific 1; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; H3K27me3,

lysine residue 27 of histone 3; H3K9me2, histone H3 lysine 9

dimethylation; UTX, ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide

repeat on chromosome X; MLL, mixed lineage leukemia; PRC2, polycomb

repressive complex 2; G9a, euchromatic histone-lysine

N-methyltransferase 2. |

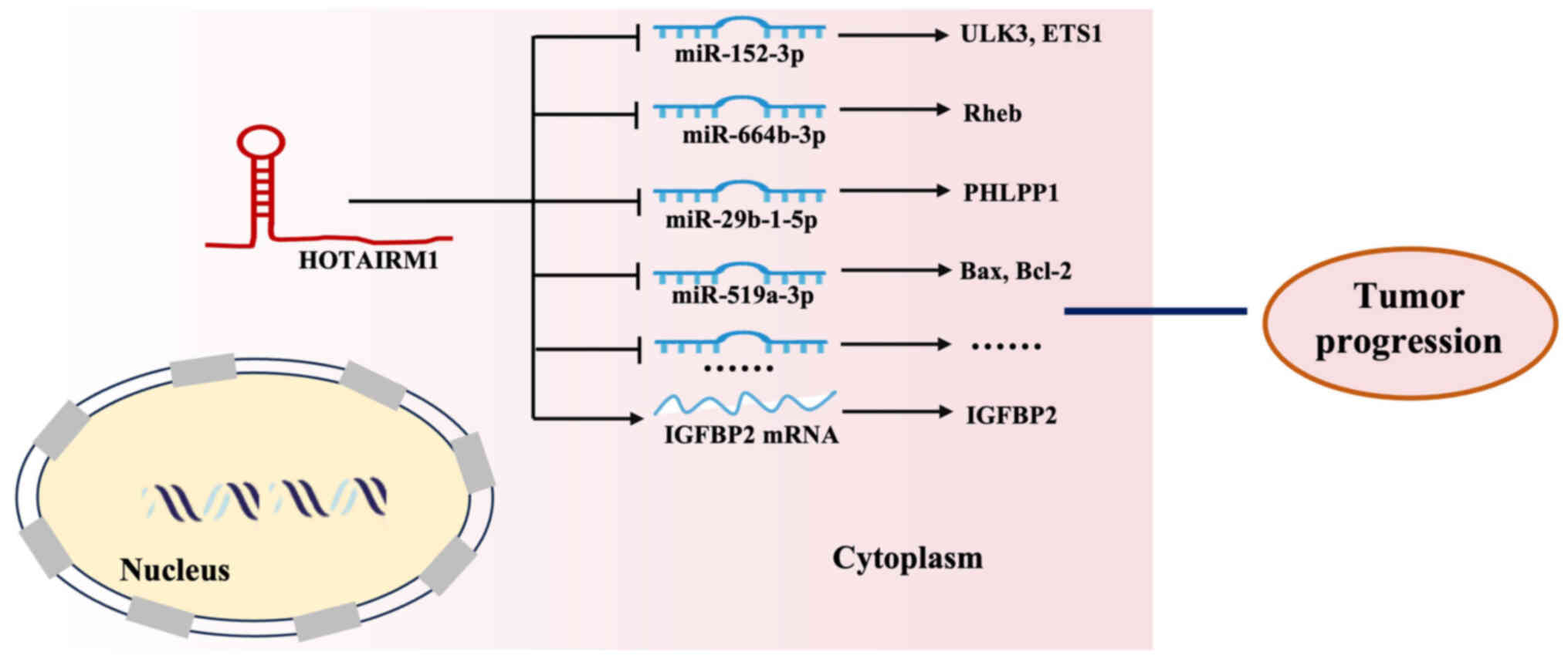

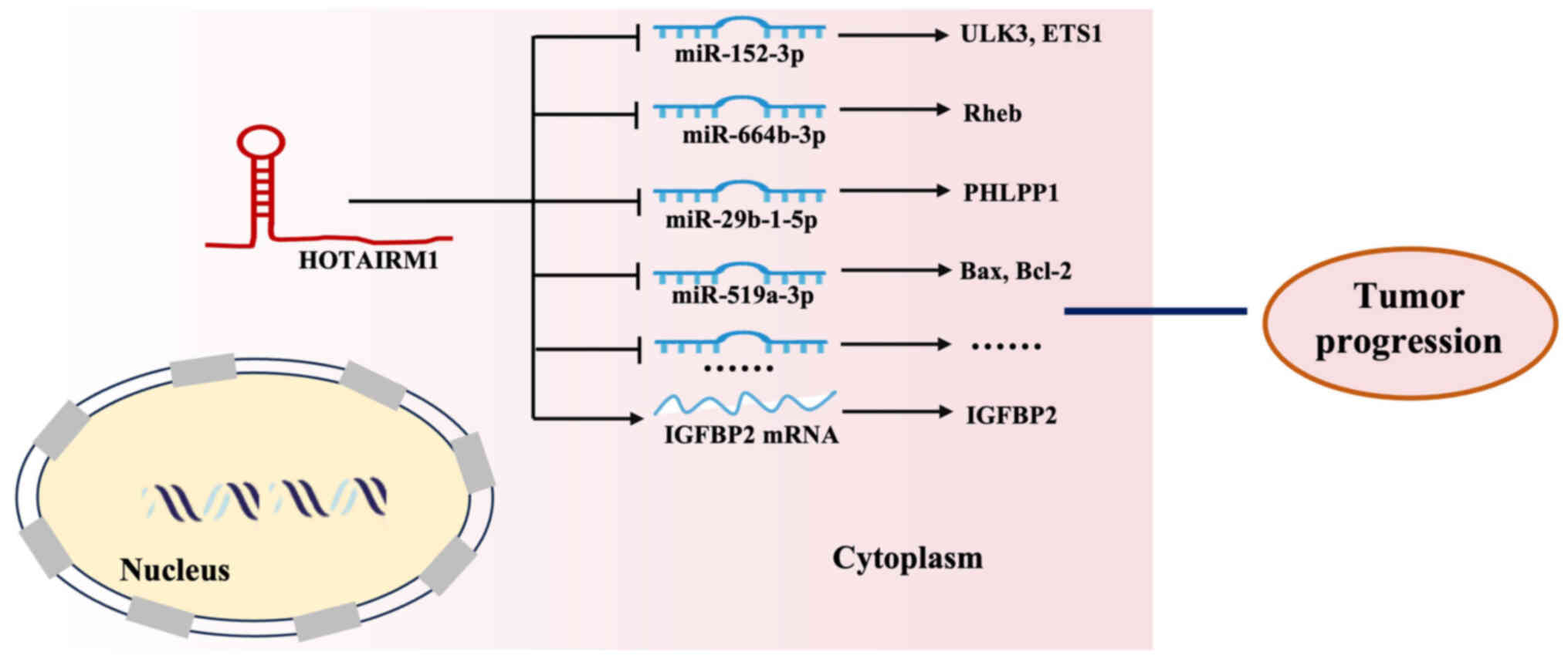

Interaction with RNA

HOTAIRM1 also interacts with RNA to mediate several

molecular functions, including the promotion of cell proliferation

(33,36), invasion and metastasis (40,58).

The relevance of competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks in

cancer initiation and progression has become apparent in recent

years (92,93). MicroRNAs (miR/miRNA) are involved in

the ceRNA network, exerting a negative influence on mRNA

expression. The canonical mechanism involves miRNAs binding to the

3′-untranslated regions of target mRNAs, which leads to their

demethylation and subsequent destabilization (94,95).

HOTAIRM1 competitively binds to specific miRNAs through the ceRNA

mechanism, thereby relieving the repression of their target mRNAs

and modulating tumor progression (Fig.

3). HOTAIRM1 competitively binds to miR-152-3p, functioning as

a ceRNA that inhibits miR-152-3p activity and therefore upregulates

its target Unc-51 like kinase 3 (ULK3), thereby modulating various

leukemic cell processes, including autophagy, proliferation and

apoptosis (36). Yu et al

(39) identified that HOTAIRM1

functions as a molecular sponge for miR-664b-3p, thereby

upregulating Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) and activating

the mTOR pathway to promote the Warburg effect in OS. Furthermore,

it enhances E26 transformation-specific 1 (ETS1) mRNA expression

and facilitates the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem

cells derived from human bone marrow (96). Similarly, HOTAIRM1 promotes PH

domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase 1 upregulation in GC

cells by sponging miR-29b-1-5p, thus demonstrating a classic ceRNA

mechanism (55). Wang et al

(97) reported that the

HOTAIRM1/miR-519a-3p axis is markedly involved in the

proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress of

neuroblastoma cells when exposed to the toxic metabolite

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium. HOTAIRM1 directly regulates mRNA

stability. Specifically, its binding to insulin-like growth factor

binding protein 2 (IGFBP2) mRNA increases IGFBP2 expression, thus

promoting glioma cell proliferation, migration, invasion and

vasculogenic mimicry formation (27).

| Figure 3.HOTAIRM1 interaction with RNA to

exert a regulatory role in tumor progression. Interaction with

specific miRNAs (e.g., miR-152-3p, miR-664b-3p, miR-29b-1-5p,

miR-519a-3p): HOTAIRM1 functions as a competitive endogenous RNA or

‘molecular sponge’ by binding to these miRNAs, leading to the

upregulation of genes like ULK3, ETS1, Rheb, PHLPP1, Bax, and

Bcl-2, which in turn modulates tumor progression. Interaction with

IGFBP2 mRNA: HOTAIRM1 directly binds to IGFBP2 mRNA to promote

tumor progression. HOTAIRM1, HOXA transcript antisense RNA

myeloid-specific 1; miR, microRNA; ULK3, Unc-51 like kinase 3;

ETS1, E26 transformation-specific 1; Rheb, Ras homolog enriched in

brain; PHLPP1, PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase 1;

IGFBP2, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2. |

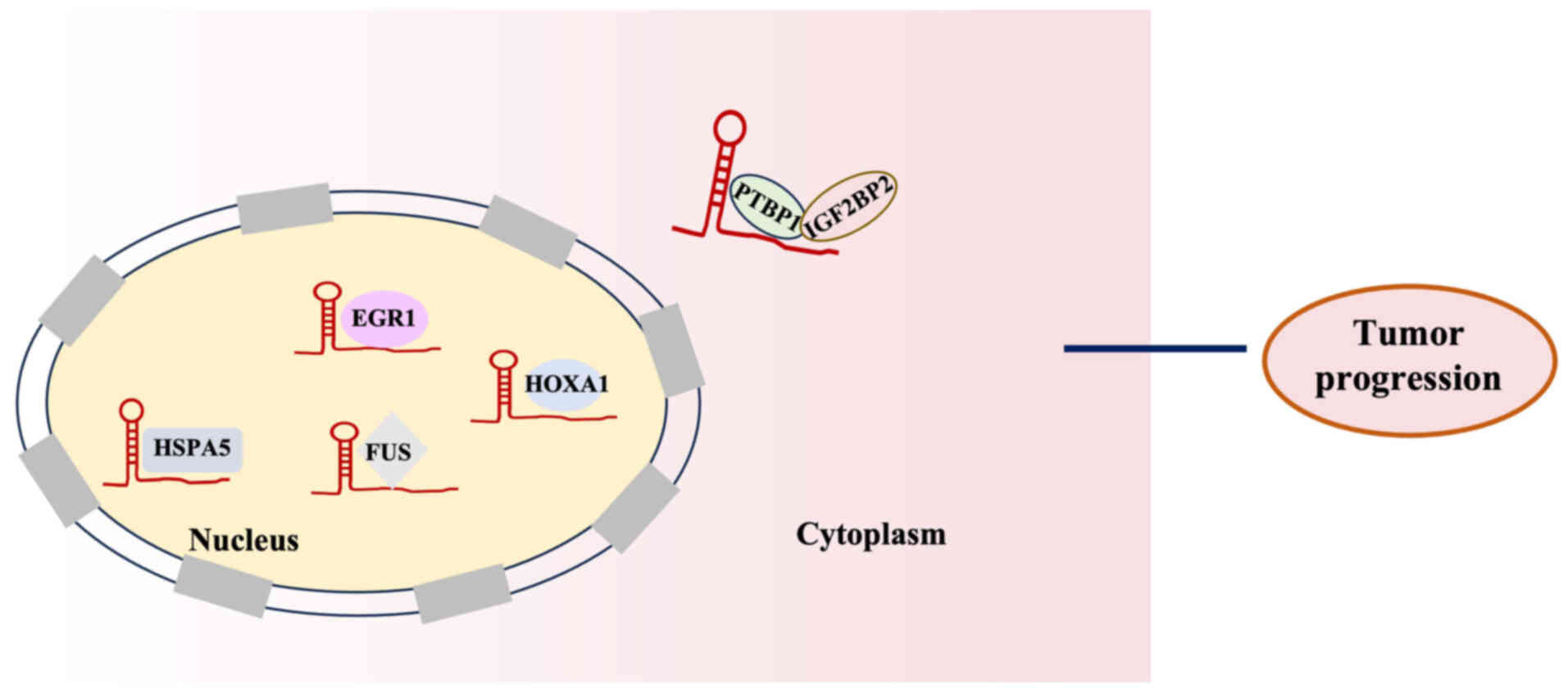

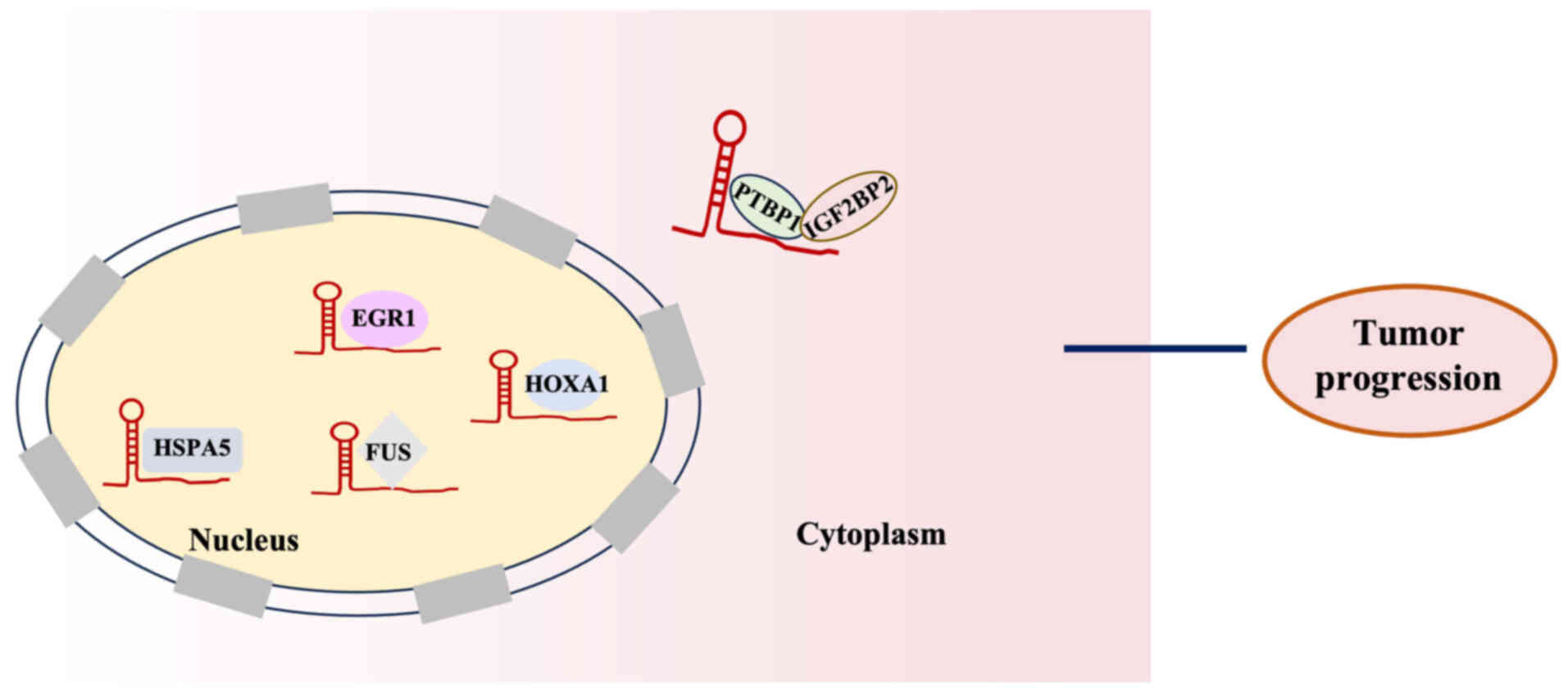

Interaction with proteins

Several lncRNAs including HOTAIRM1 are involved in

the molecular regulation of proteins by directly binding to them

(Fig. 4). For example, HOTAIRM1

interacts with heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 5 (HSPA5)

and transcriptionally regulates its expression, with the resulting

effects on proliferation being partly dependent on this chaperone

(98). Han et al (98) demonstrated that HOTAIRM1 forms a

complex with polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 and

insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2, strengthening

their interaction and facilitating their recruitment to the serine

hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2) mRNA. Therefore, the stability

of SHMT2 mRNA has improved, leading to an increase in SHMT2 protein

expression. This ultimately induces mitochondrial activity and

promotes the malignant advancement of glioma. Liu et al

(28) reported that HOTAIRM1 binds

to the RNA-binding protein fused in sarcoma (FUS), thereby

regulating E2F transcription factor 7 expression, promoting the

proliferation, migration and invasion of glioma stem

cell-transformed mesenchymal stem cells. In addition, Chen et

al (99) demonstrated that the

regulation of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in lung

alveolar epithelial cells is controlled by HOTAIRM1 through its

interaction with the key transcription factor HOXA1, having

alleviated lung injury and improved survival of mice. Jing et

al (36) demonstrated that the

interaction of HOTAIRM1 with early growth response 1 (EGR1) and

murine double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) suggests that it serves as a

scaffold facilitating MDM2 recruitment to EGR1, thereby promoting

autophagy and proliferation in leukemia cells.

| Figure 4.HOTAIRM1 interaction with proteins to

exert a regulatory role in tumor progression. Interaction with

HSPA5: HOTAIRM1 interacts with HSPA5 to transcriptionally regulate

its expression, influencing tumor progression. Interaction with

PTBP1 and IGF2BP2: HOTAIRM1 forms a complex with PTBP1 and IGF2BP2

to enhance its stability, thereby promoting tumor progression.

Interaction with FUS: HOTAIRM1 binds to the RNA-binding protein FUS

to promote tumor progression. Interaction with HOXA1: HOTAIRM1

interacts with HOXA1 to regulate tumor progression. Interaction

with EGR1: HOTAIRM1 acts as a scaffold, facilitating the EGR1 to

promote tumor progression. HOTAIRM1, HOXA transcript antisense RNA

myeloid-specific 1; IGF2BP2, insulin-like growth factor 2

mRNA-binding protein 2; EGR1, early growth response 1; FUS, fused

in sarcoma; HSPA2, heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 2;

PTBP1, polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1; HOXA1, homeobox

A1. |

HOTAIRM1 regulates various hallmarks of

cancer

Cancer is complex disease characterized by multiple

genetic abnormalities, including epigenetic alterations,

chromosomal translocations and gene deletions or amplifications.

The human genome encodes several lncRNAs (such as PVT1, HOTAIR and

MALAT1), most of which are not translated into proteins. Despite

their lack of coding potential, lncRNAs exert key regulatory

functions among different cellular processes (11,100).

Among them, HOTAIRM1 modulates multiple signaling pathways (Wnt,

Caspase signaling pathways) and is associated with hallmark cancer

traits such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis,

metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis (Fig. 5).

| Figure 5.HOTAIRM1 regulates various hallmarks

of cancer. HOTAIRM1 promotes cell proliferation by upregulating

Igfbp2/Hspa5/mTor or downregulating Egr1, while also upregulating

Pik3cd to exert an inhibitory effect on proliferation; HOTAIRM1

suppresses apoptosis by downregulating Bcl-2/Bid/p53 and promotes

autophagy by upregulating Ulk3/LC3 while downregulating p62;

HOTAIRM1 promotes EMT by upregulating Hoxa1 and downregulating

BTG3, leading to increased N-cadherin/Vimentin/Snail and decreased

E-cadherin; HOTAIRM1 promotes cell differentiation by upregulating

Nanog/Sox2/Pou5f1/Ets1 and downregulating miR-125b; HOTAIRM1

promotes metabolic reprogramming by upregulating mTOR/Hk2 to

enhance glycolysis and increasing Shmt2 to stimulate serine

metabolism; HOTAIRM1 modulates therapy response through

upregulating RhoA/ROCK1/Beclin-1/BTG3 expression. HOTAIRM1, HOXA

transcript antisense RNA myeloid-specific 1; Igfbp2, insulin-like

growth factor binding protein 2; Egr1, early growth response 1;

miR, microRNA; Ulk3, Unc-51 like kinase 3; Hoxa1, homeobox A1;

Ets1, E26 transformation-specific 1; Shmt2, serine

hydroxymethyltransferase 2; Hk2, hexokinase 2; Btg3, B-cell

translocation gene 3; Rock1, ρ-associated coiled-coil containing

protein kinase 1; Rhoa, Ras homolog family member A; Bid, BH3

interacting-domain death agonist; Pik3cd,

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit

∆. |

Proliferation

Dysregulated cell proliferation resulting in

uncontrolled growth represents a fundamental hallmark of

tumorigenesis (101). Aberrant

expression of HOTAIRM1 has been reported in multiple tumor types

and is closely associated with enhanced tumor cell proliferation.

For example, Wu et al (33)

identified an increase in HOTAIRM1 expression in both glioma

tissues and cells. Furthermore, HOTAIRM1 overexpression increases

the proliferation of glioma cells. Zhou et al (102) identified a key functional

connection among HOXA4, HOTAIRM1 and HSPA5, forming a novel

regulatory circuit that governs HUVEC proliferation. HOTAIRM1

promotes OS cell proliferation by sponging miR-664b-3p, thereby

activating the mTOR pathway (39).

On the other hand, HOTAIRM1 also suppresses the proliferative

ability of granulosa cells (103).

Furthermore, Jing et al (36) demonstrated that HOTAIRM1 markedly

promotes the proliferation of AML cells harboring NPM1

mutations.

Cell death

Apoptosis is a programmed form of cell death that

maintains cellular balance. The induction of apoptosis in cancer

cells is a key strategy in clinical cancer therapy. Dahariya et

al (104) reported that

HOTAIRM1 functions as a molecular decoy for miR-125b regulating

apoptosis to facilitate the terminal differentiation of

megakaryocytes, thereby regulating key processes including

apoptosis, cyclin D1-dependent cell cycling, and reactive oxygen

species production. HOTAIRM1 also induces Jurkat cell apoptosis

through the KIT/AKT signaling pathway (105). Liu et al (106) demonstrated that the loss of

HOTAIRM1 activity causes an abnormal increase in chondrocyte

apoptosis. Similarly, Ye et al (49) reported that HOTAIRM1 suppression

increases the expression of pro-apoptotic factors, including Bad

and Bax, while it reduces the expression of BH3 interacting-domain

death agonist and Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic factors) in ovarian cancer

cells.

Autophagy is a self-degradative process in which

cytoplasmic proteins and organelles are delivered to lysosomes to

maintain cellular metabolism and homeostasis. A previous study has

reported that HOTAIRM1 induces autophagy by upregulating ULK3

expression, leading to an increased expression of autophagy-related

proteins including microtubule-associated protein LC3 II and a

concomitant decrease in the autophagy substrate p62, thereby

promoting cell proliferation and exerting a pro-tumorigenic effect

(36).

Invasion and metastasis

Metastasis is a complex, multistep process involving

EMT, invasion, intravasation, cell survival in the bloodstream,

extravasation and the formation of secondary tumor colonies. The

initial step in cancer metastasis is the EMT, during which

epithelial cells lose their polarity and intercellular adhesion,

acquire mesenchymal characteristics and gain enhanced migratory and

invasive abilities. The upregulation of HOXA1 expression by

HOTAIRM1 enhances the ability of type I EC cells to undergo EMT and

metastasis, resulting in a decrease in the epithelial marker

E-cadherin expression and an increase in the mesenchymal marker

N-cadherin (40). Ren et al

(58) examined the impact of

HOTAIRM1 dysregulation in 5-FU-resistant CRC cells and identified

that the increased expression of HOTAIRM1 reduces cell invasion and

migration according to EMT assay.

Cell differentiation

Cell differentiation is the process through which

cells acquire specialized function and form distinct tissues. By

contrast, carcinogenesis represents a breakdown of normal

differentiation, resulting in the uncontrolled proliferation of

immature or aberrant cells. Tollis et al (107) used a model framework of spinal

motor neurons to demonstrate that neuronal HOTAIRM1, a specific

isoform of HOTAIRM1, influences cell fate between motor neurons and

interneurons by promoting motor neuron differentiation. HOTAIRM1

contributes to proper progression during the early stages of

neuronal differentiation. It also influences the core pluripotency

network composed of NANOG, POU class 5 homeobox 1 and Sox2, thereby

helping to maintain cells in an undifferentiated state (108). Wang et al (73) identified HOTAIRM1 as a novel

regulator of the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived

mesenchymal stem cells. This regulation occurs through the

miR-152-3p/ETS1 axis, suggesting that HOTAIRM1 may represent a

potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis. Furthermore,

Dahariya et al (104)

demonstrated that HOTAIRM1 regulates the p53-mediated control of

cyclin D1 expression during megakaryocytopoiesis. The function of

HOTAIRM1 is to promote megakaryocyte maturation by acting as a

molecular sponge for miR-125b.

Metabolism

Tumor cells undergo notable metabolic reprogramming

to support their rapid proliferation. Unlike regular cells, they

preferentially use aerobic glycolysis, an energetically inefficient

pathway with a considerably higher turnover rate, even under

oxygen-sufficient conditions, a phenomenon known as the Warburg

effect. The miR-664b-3p/Rheb/mTOR axis markedly improves the

Warburg effect in OS cells, due to the notable enhancement by

HOTAIRM1 (39). HOTAIRM1 knockdown

attenuates the Warburg effect in NSCLC by reducing glucose uptake

and lactate production. This metabolic suppression is associated

with a marked decrease in hexokinase 2 protein expression, a key

glycolytic enzyme that phosphorylates glucose to initiate

glycolysis and sustain cancer cell energy metabolism (43). Han et al (98) reported that HOTAIRM1 increases SHMT2

protein expression by improving the lifespan of its mRNA, leading

to the stimulation of mitochondrial activity through oxidative

phosphorylation and serine metabolism.

Therapy response

Despite notable advances in antitumor therapies,

resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy and

immunotherapy still represents a major obstacle to an effective

cancer treatment (109). HOTAIRM1

is involved in the response to therapy by cancer cells. According

to previous research, HOTAIRM1 interacts with the inhibitory region

of ρ GTPase-activating protein 18 and suppresses its expression,

resulting in the activation of the Ras homolog family member

A/ρ-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 signaling

pathway and enhancing leukemia cell resistance to glucocorticoid

treatment (110). Gu et al

(111) reported that HOTAIRM1

upregulation leads to lenvatinib resistance by reducing miR-34a

expression and increasing Beclin-1 expression in HCC cancer cells.

In addition, Chen et al (112) revealed that HOTAIRM1 suppression

increases the effectiveness of cytarabine in killing cells by

controlling the Wnt/β-catenin/platelet-type isoform of

phosphofructokinase signaling pathway. In vitro and in

vivo, HOTAIRM1 functions as a tumor suppressor in

5-FU-resistant CRC cells by reducing the activity of the

miR-17-5p/B-cell translocation gene 3 (BTG3) pathway and preventing

the development of multi-drug resistance (58).

Conclusion and prospects

Cancer remains a major global threat to human

health. Although recent advances have slightly reduced the overall

mortality rates, notable obstacles persist in the early diagnosis

and effective management. Numerous patients are still diagnosed at

advanced stages of the disease, which notably worsens their

prognosis (113,114). Hence, it is key to identify novel

biomarkers and examine the different molecular pathways involved in

cancer for its timely detection and management.

Several studies have indicated the abnormal

expression of lncRNAs in several diseases and their ability to

function as tumor suppressors or oncogenes (115,116). HOTAIRM1 exhibits an abnormal

expression in both tumor tissues and cells of different types of

cancer and it serves as a standalone indicator for unfavorable

prognosis in a wide range of carcinomas. HOTAIRM1 upregulation

promotes tumor cell proliferation in several neoplasms, including

glioma, AML, OS, EC, TC, NSCLC, OSCC, PCa, PDAC and OC. However,

HOTAIRM1 upregulation suppresses cancer cell proliferation in PTC,

OC, HNT, HCC, ADC, GC and CRC. Furthermore, a strong association

exists between atypical HOTAIRM1 expression and several clinical

and pathological characteristics of tumors, including age, tumor

size, invasion of blood vessels, metastasis, overall survival and

recurrence. These findings support the idea that the cellular

function of HOTAIRM1 is not static but context-dependent.

Initially, HOTAIRM1 triggers H3K27me3 by interacting

with EZH2/PRC2 and also participates in the alteration of chromatin

structure by directing the recruitment of chromatin-modifying

enzymes to a specific gene location. Furthermore, HOTAIRM1 acts as

a molecular sponge for miRNAs, exerting its regulatory effects

through the HOTAIRM1-miRNA-mRNA pathway. In addition, HOTAIRM1

binds to functional proteins within both the nucleus and cytoplasm,

thereby modulating their expression and markedly influencing tumor

progression. Other potential molecular mechanisms underlying the

biological functions of HOTAIRM1 warrant further investigation.

HOTAIRM1 potentially regulates tumors and impacts

multiple aspects of cancer, such as cell proliferation, death,

invasion, spread, cellular differentiation, metabolism and

resistance to chemotherapy. Nevertheless, in certain contexts, such

as drug resistance, the exact function of HOTAIRM1 remains to be

elucidated, as current studies report conflicting results that

require further detailed investigation. Liang et al

(110) revealed that HOTAIRM1

promotes GC resistance by inhibiting apoptosis in leukemia cells.

Notably, Ren et al (58)

reported that HOTAIRM1 suppresses the miR-17-5p/BTG3 pathway,

leading to the inhibition of multi-drug resistance. Currently,

further in-depth research is required to explore the potential

ability of HOTAIRM1 to control additional characteristics of

cancer, including the evasion of immune surveillance, genome

instability and mutation, non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming,

unlocking phenotypic plasticity and polymorphic microbiomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of

Beijing Municipal (grant no. 7254399) and supported by the

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no.

APL24100310010301071027).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YJ and YG conceptualized the present review. YJ and

XL prepared the original draft. YJ and YG reviewed and edited the

manuscript. YJ and YG provided supervision and project

administration. YJ obtained funding for the present review. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

lncRNAs

|

long non-coding RNAs

|

|

HOTAIRM1

|

HOXA transcript antisense RNA

myeloid-specific 1

|

|

AML

|

acute myeloid leukemia

|

|

OS

|

osteosarcoma

|

|

EC

|

endometrial cancer

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

TC

|

thyroid cancer

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

OSCC

|

oral squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

PCa

|

prostate cancer

|

|

PDAC

|

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

ADC

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

GC

|

gastric cancer

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

PRC2

|

polycomb repressive complex 2

|

|

H3K27me3

|

lysine residue 27 of histone 3

|

References

|

1

|

Vaghari-Tabari M, Ferns GA, Qujeq D,

Andevari AN, Sabahi Z and Moein ZS: Signaling, metabolism, and

cancer: An important relationship for therapeutic intervention. J

Cell Physiol. 236:5512–5532. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Giunta S: Decoding human cancer with whole

genome sequencing: A review of PCAWG Project studies published in

February 2020. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 40:909–924. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chi Y, Wang D, Wang J, Yu W and Yang J:

Long non-coding RNA in the pathogenesis of cancers. Cells.

8:10152019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ramezankhani R, Solhi R, Es HA, Vosough M

and Hassan M: Novel molecular targets in gastric adenocarcinoma.

Pharmacol Ther. 220:1077142021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Guo N, Liu JB, Li W, Ma YS and Fu D: The

power and the promise of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for clinical

application with gene therapy. J Adv Res. 40:135–152. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Traba J, Sack MN, Waldmann TA and Anton

OM: Immunometabolism at the nexus of cancer therapeutic efficacy

and resistance. Front Immunol. 12:6572932021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ghafouri-Fard S, Khoshbakht T, Taheri M

and Hajiesmaeili M: Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 460:

Review of its role in carcinogenesis. Pathol Res Pract.

225:1535562021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hovhannisyan H and Gabaldón T: The long

non-coding RNA landscape of Candida yeast pathogens. Nat Commun.

12:73172021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kovalenko TF, Yadav B, Anufrieva KS,

Rubtsov YP, Zatsepin TS, Shcherbinina EY, Solyus EM, Staroverov DB,

Larionova TD, Latyshev YA, et al: Functions of long non-coding RNA

ROR in patient-derived glioblastoma cells. Biochimie. 200:131–139.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL and Huarte M:

Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological

functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:96–118. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Herman AB, Tsitsipatis D and Gorospe M:

Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation.

Mol Cell. 82:2252–2266. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Sun KK, Zu C, Wu XY, Wang QH, Hua P, Zhang

YF, Shen XJ and Wu YY: Identification of lncRNA and mRNA regulatory

networks associated with gastric cancer progression. Front Oncol.

13:11404602023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Pierce JB, Zhou H, Simion V and Feinberg

MW: Long noncoding RNAs as therapeutic targets. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1363:161–175. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sun W, Xu J, Wang L, Jiang Y, Cui J, Su X,

Yang F, Tian L, Si Z and Xing Y: Non-coding RNAs in cancer

therapy-induced cardiotoxicity: Mechanisms, biomarkers, and

treatments. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9:9461372022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhu Y, Ren J, Wu X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Xu J,

Tan Q, Jiang Y and Li Y: lncRNA ENST00000422059 promotes cell

proliferation and inhibits cell apoptosis in breast cancer by

regulating the miR-145-5p/KLF5 axis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin

(Shanghai). 55:1892–1901. 2023.

|

|

16

|

Bah I, Youssef D, Yao ZQ, McCall CE and El

Gazzar M: Hotairm1 controls S100A9 protein phosphorylation in

myeloid-derived suppressor cells during sepsis. J Clin Cell

Immunol. 14:10006912023.

|

|

17

|

Zhang X, Weissman SM and Newburger PE:

Long intergenic non-coding RNA HOTAIRM1 regulates cell cycle

progression during myeloid maturation in NB4 human promyelocytic

leukemia cells. RNA Biol. 11:777–787. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Basyegit H, Tatar BG, Kose S, Gunduz C,

Ozmen Yelken B and Yilmaz Susluer S: Exploring the role of long

non-coding RNAs in predicting outcomes for hepatitis B patients.

Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 25:4313–4321. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bagheri-Mohammadi S, Karamivandishi A,

Mahdavi SA and Siahposht-Khachaki A: New sights on long non-coding

RNAs in glioblastoma: A review of molecular mechanism. Heliyon.

10:e397442024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Nekoeian S, Rostami T, Norouzy A, Hussein

S, Tavoosidana G, Chahardouli B, Rostami S, Asgari Y and Azizi Z:

Identification of lncRNAs associated with the progression of acute

lymphoblastic leukemia using a competing endogenous RNAs network.

Oncol Res. 30:259–268. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chen R, Zhou D, Chen Y, Chen M and Shuai

Z: Understanding the role of exosomal lncRNAs in rheumatic

diseases: A review. PeerJ. 11:e164342023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ramos TAR, Urquiza-Zurich S, Kim SY,

Gillette TG, Hill JA, Lavandero S, Rêgo TG and Maracaja-Coutinho V:

Single-cell transcriptional landscape of long non-coding RNAs

orchestrating mouse heart development. Cell Death Dis. 14:8412023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hu C, Dai Q, Zhang R, Yang H, Wang M, Gu

K, Yang J, Meng W, Chen P and Xu M: Case report: Identification of

a novel LYN::LINC01900 transcript with promyelocytic phenotype and

TP53 mutation in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol.

13:13224032023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang D, Zhao X, Li S, Guo H, Li S and Yu

D: The impact of LncRNA-SOX2-OT/let-7c-3p/SKP2 Axis on head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma progression: Insights from

bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Cell Signal.

115:1110182024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Yu M, He X, Liu T and Li J: lncRNA

GPRC5D-AS1 as a ceRNA inhibits skeletal muscle aging by regulating

miR-520d-5p. Aging (Albany NY). 15:13980–13997. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhang X, Zhong Y, Liu L, Jia C, Cai H,

Yang J, Wu B and Lv Z: Fasting regulates mitochondrial function

through lncRNA PRKCQ-AS1-mediated IGF2BPs in papillary thyroid

carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 14:8272023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wu Z, Lin Y and Wei N:

N6-methyladenosine-modified HOTAIRM1 promotes vasculogenic mimicry

formation in glioma. Cancer Sci. 114:129–141. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Liu L, Zhou Y, Dong X, Li S, Cheng S, Li

H, Li Y, Yuan J, Wang L and Dong J: HOTAIRM1 maintained the

malignant phenotype of tMSCs transformed by GSCs via E2F7 by

binding to FUS. J Oncol. 2022:77344132022.

|

|

29

|

Shi T, Guo D, Xu H, Su G, Chen J, Zhao Z,

Shi J, Wedemeyer M, Attenello F, Zhang L and Lu W: HOTAIRM1, an

enhancer lncRNA, promotes glioma proliferation by regulating

long-range chromatin interactions within HOXA cluster genes. Mol

Biol Rep. 47:2723–2733. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang H, Li H, Jiang Q, Dong X, Li S, Cheng

S, Shi J, Liu L, Qian Z and Dong J: HOTAIRM1 promotes malignant

progression of transformed fibroblasts in glioma stem-like cells

remodeled microenvironment via regulating miR-133b-3p/TGFβ Axis.

Front Oncol. 11:6031282021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Xia H, Liu Y, Wang Z, Zhang W, Qi M, Qi B

and Jiang X: Long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 maintains tumorigenicity

of glioblastoma stem-like cells through regulation of HOX gene

expression. Neurotherapeutics. 17:754–764. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hao Y, Li X, Chen H, Huo H, Liu Z and Chai

E: Over-expression of long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 promotes cell

proliferation and invasion in human glioblastoma by up-regulating

SP1 via sponging miR-137. Neuroreport. 31:109–117. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wu Z and Wei N: METTL3-mediated HOTAIRM1

promotes vasculogenic mimicry icontributionsn glioma via regulating

IGFBP2 expression. J Transl Med. 21:8552023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Xie P, Li X, Chen R, Liu Y, Liu DC, Liu W,

Cui G and Xu J: Upregulation of HOTAIRM1 increases migration and

invasion by glioblastoma cells. Aging (Albany NY). 13:2348–2364.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ahmadov U, Picard D, Bartl J, Silginer M,

Trajkovic-Arsic M, Qin N, Blümel L, Wolter M, Lim JKM, Pauck D, et

al: The long non-coding RNA HOTAIRM1 promotes tumor aggressiveness

and radiotherapy resistance in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis.

12:8852021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jing Y, Jiang X, Lei L, Peng M, Ren J,

Xiao Q, Tao Y, Tao Y, Huang J, Wang L, et al: Mutant NPM1-regulated

lncRNA HOTAIRM1 promotes leukemia cell autophagy and proliferation

by targeting EGR1 and ULK3. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:3122021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wei S, Zhao M, Wang X, Li Y and Wang K:

PU.1 controls the expression of long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 during

granulocytic differentiation. J Hematol Oncol. 9:442016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hu N, Chen L, Li Q and Zhao H: LncRNA

HOTAIRM1 is involved in the progression of acute myeloid leukemia

through targeting miR-148b. RSC Adv. 9:10352–10359. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yu X, Duan W, Wu F, Yang D, Wang X, Wu J,

Zhou D and Shen Y: LncRNA-HOTAIRM1 promotes aerobic glycolysis and

proliferation in osteosarcoma via the miR-664b-3p/Rheb/mTOR

pathway. Cancer Sci. 114:3537–3552. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Li X, Pang L, Yang Z, Liu J, Li W and Wang

D: LncRNA HOTAIRM1/HOXA1 axis promotes cell proliferation,

migration and invasion in endometrial cancer. Onco Targets Ther.

12:10997–11015. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhang L, Zhang J, Li S, Zhang Y, Liu Y,

Dong J, Zhao W, Yu B, Wang H and Liu J: Genomic amplification of

long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 drives anaplastic thyroid cancer

progression via repressing miR-144 biogenesis. RNA Biol.

18:547–562. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Li C, Chen X, Liu T and Chen G: lncRNA

HOTAIRM1 regulates cell proliferation and the metastasis of thyroid

cancer by targeting Wnt10b. Oncol Rep. 45:1083–1093. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chen D, Li Y, Wang Y and Xu J: LncRNA

HOTAIRM1 knockdown inhibits cell glycolysis metabolism and tumor

progression by miR-498/ABCE1 axis in non-small cell lung cancer.

Genes Genomics. 43:183–194. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Xiong F, Yin H, Zhang H, Zhu C, Zhang B,

Chen S, Ling C and Chen X: Clinicopathologic features and the

prognostic implications of long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 in non-small

cell lung cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 24:47–53. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Yu Y, Niu J, Zhang X, Wang X, Song H, Liu

Y, Jiao X and Chen F: Identification and validation of HOTAIRM1 as

a novel biomarker for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front Bioeng

Biotechnol. 9:7985842022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wang L, Wang L, Wang Q, Yosefi B, Wei S,

Wang X and Shen D: The function of long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 in

the progression of prostate cancer cells. Andrologia.

53:e138972021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Luo Y, He Y, Ye X, Song J, Wang Q, Li Y

and Xie X: High expression of long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 is

associated with the proliferation and migration in pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 25:1567–1577. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Zhou Y, Gong B, Jiang ZL, Zhong S, Liu XC,

Dong K, Wu HS, Yang HJ and Zhu SK: Microarray expression profile

analysis of long non-coding RNAs in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 48:670–680. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Ye L, Meng X, Xiang R, Li W and Wang J:

Investigating function of long noncoding RNA of HOTAIRM1 in

progression of SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells. Drug Dev Res.

82:1162–1168. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Chao H, Zhang M, Hou H, Zhang Z and Li N:

HOTAIRM1 suppresses cell proliferation and invasion in ovarian

cancer through facilitating ARHGAP24 expression by sponging

miR-106a-5p. Life Sci. 243:1172962020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Li D, Chai L, Yu X, Song Y, Zhu X, Fan S,

Jiang W, Qiao T, Tong J, Liu S, et al: The HOTAIRM1/miR-107/TDG

axis regulates papillary thyroid cancer cell proliferation and

invasion. Cell Death Dis. 11:2272020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Zheng M, Liu X, Zhou Q and Liu G: HOTAIRM1

competed endogenously with miR-148a to regulate DLGAP1 in head and

neck tumor cells. Cancer Med. 7:3143–3156. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang Y, Mi L, Xuan Y, Gao C, Wang YH,

Ming HX and Liu J: LncRNA HOTAIRM1 inhibits the progression of

hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway.

Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 22:4861–4868. 2018.

|

|

54

|

Chen TJ, Gao F, Yang T, Li H, Li Y, Ren H

and Chen MW: LncRNA HOTAIRM1 inhibits the proliferation and

invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells via the miR-498/WWOX Axis.

Cancer Manag Res. 12:4379–4390. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Xu F, Chen M, Chen H, Wu N, Qi Q, Jiang X,

Fang D, Feng Q, Jin R and Jiang L: The curcumin analog Da0324

inhibits the proliferation of gastric cancer cells via

HOTAIRM1/miR-29b-1-5p/PHLPP1 Axis. J Cancer. 13:2644–2655. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lu R, Zhao G, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Cai J,

Zhang Z and Hu H: Long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 inhibits cell

progression by regulating miR-17-5p/PTEN axis in gastric cancer. J

Cell Biochem. 120:4952–4965. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Wan L, Kong J, Tang J, Wu Y, Xu E, Lai M

and Zhang H: HOTAIRM1 as a potential biomarker for diagnosis of

colorectal cancer functions the role in the tumour suppressor. J

Cell Mol Med. 20:2036–2044. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Ren T, Hou J, Liu C, Shan F, Xiong X, Qin

A, Chen J and Ren W: The long non-coding RNA HOTAIRM1 suppresses

cell progression via sponging endogenous miR-17-5p/B-cell

translocation gene 3 (BTG3) axis in 5-fluorouracil resistant

colorectal cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 117:1091712019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Zhang W, Dang R, Liu H, Dai L, Liu H,

Adegboro AA, Zhang Y, Li W, Peng K, Hong J and Li X: Machine

learning-based investigation of regulated cell death for predicting

prognosis and immunotherapy response in glioma patients. Sci Rep.

14:41732024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Zafar N, Ghias K and Fadoo Z: Genetic

aberrations involved in relapse of pediatric acute myeloid

leukemia: A literature review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 17:e135–e141.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hayatigolkhatmi K, Valzelli R, El Menna O

and Minucci S: Epigenetic alterations in AML: Deregulated functions

leading to new therapeutic options. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol.

387:27–75. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Ding Y and Chen Q: Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway: An attractive potential therapeutic target in

osteosarcoma. Front Oncol. 14:14569592025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

“personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017.

|

|

64

|

Ding S, Hao Y, Qi Y, Wei H, Zhang J and Li

H: Molecular mechanism of tumor-infiltrating immune cells

regulating endometrial carcinoma. Genes Dis. 12:1014422024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Menendez-Santos M, Gonzalez-Baerga C,

Taher D, Waters R, Virarkar M and Bhosale P: Endometrial cancer:

2023 Revised FIGO staging system and the role of imaging. Cancers

(Basel). 16:18692024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Chen DW, Lang BHH, McLeod DSA, Newbold K

and Haymart MR: Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 401:1531–1544. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Boucai L, Zafereo M and Cabanillas ME:

Thyroid cancer: A review. JAMA. 331:425–435. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Meyer ML, Fitzgerald BG, Paz-Ares L,

Cappuzzo F, Jänne PA, Peters S and Hirsch FR: New promises and

challenges in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.

Lancet. 404:803–822. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Badwelan M, Muaddi H, Ahmed A, Lee KT and

Tran SD: Oral squamous cell carcinoma and concomitant primary

tumors, what do we know? A review of the literature. Curr Oncol.

30:3721–3734. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Jagadeesan D, Sathasivam KV, Fuloria NK,

Balakrishnan V, Khor GH, Ravichandran M, Solyappan M, Fuloria S,

Gupta G, Ahlawat A, et al: Comprehensive insights into oral

squamous cell carcinoma: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapeutic

advances. Pathol Res Pract. 261:1554892024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Almeeri MNE, Awies M and Constantinou C:

Prostate cancer, pathophysiology and recent developments in

management: A narrative review. Curr Oncol Rep. 26:1511–1519. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wilson TK and Zishiri OT: Prostate cancer:

A review of genetics, current biomarkers and personalised

treatments. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 7:e700162024.

|

|

73

|

Dhillon J and Betancourt M: Pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma. Monogr Clin Cytol. 26:74–91. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Konstantinopoulos PA and Matulonis UA:

Clinical and translational advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Nat

Cancer. 4:1239–1257. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Chow LQM: Head and neck cancer. N Engl J

Med. 382:60–72. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Kudrimoti A and Kudrimoti MR: Head and

neck cancers. Prim Care. 52:139–155. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Da BL, Suchman KI, Lau L, Rabiee A, He AR,

Shetty K, Yu H, Wong LL, Amdur RL, Crawford JM, et al: Pathogenesis

to management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Cancer. 13:72–87.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Akhras A, Beran A, Guardiola J,

Bhavsar-Burke I, Reyes B and Ur Rahman A: S2808 direct oral

anticoagulants versus warfarin in elderly patients with child-pugh

C cirrhosis and atrial fibrillation: A real-world perspective. Am J

Gastroenterol. 120((10S2)): pS6032025.

|

|

79

|

Tawfiq RK, de Camargo Correia GS, Li S,

Zhao Y, Lou Y and Manochakian R: Targeting lung cancer with

precision: The ADC therapeutic revolution. Curr Oncol Rep.

27:669–686. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Merle G, Friedlaender A, Desai A and Addeo

A: Antibody drug conjugates in lung cancer. Cancer J. 28:429–435.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

López MJ, Carbajal J, Alfaro AL, Saravia

LG, Zanabria D, Araujo JM, Quispe L, Zevallos A, Buleje JL, Cho CE,

et al: Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 181:1038412023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Baidoun F, Elshiwy K, Elkeraie Y, Merjaneh

Z, Khoudari G, Sarmini MT, Gad M, Al-Husseini M and Saad A:

Colorectal cancer epidemiology: Recent trends and impact on

outcomes. Curr Drug Targets. 22:998–1009. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Mahmoud NN: Colorectal cancer:

Preoperative evaluation and staging. Surg Oncol Clin N Am.

31:127–141. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Salido-Guadarrama I, Romero-Cordoba SL and

Rueda-Zarazua B: Multi-Omics Mining of lncRNAs with biological and

clinical relevance in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:166002023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Mahato RK, Bhattacharya S, Khullar N,

Sidhu IS, Reddy PH, Bhatti GK and Bhatti JS: Targeting long

non-coding RNAs in cancer therapy using CRISPR-Cas9 technology: A

novel paradigm for precision oncology. J Biotechnol. 379:98–119.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Yang Q, Fu Y, Wang J, Yang H and Zhang X:

Roles of lncRNA in the diagnosis and prognosis of triple-negative

breast cancer. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 24:1123–1140. 2023.(In

English, Chinese). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Alharthi NS, Al-Zahrani MH, Hazazi A,

Alhuthali HM, Gharib AF, Alzahrani S, Altalhi W, Almalki WH and

Khan FR: Exploring the lncRNA-VEGF axis: Implications for cancer

detection and therapy. Pathol Res Pract. 253:1549982023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Mehmandar-Oskuie A, Jahankhani K,

Rostamlou A, Mardafkan N, Karamali N, Razavi ZS and Mardi A:

Molecular mechanism of lncRNAs in pathogenesis and diagnosis of

auto-immune diseases, with a special focus on lncRNA-based

therapeutic approaches. Life Sci. 336:1223222024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Li Q, Dong C, Cui J, Wang Y and Hong X:

Over-expressed lncRNA HOTAIRM1 promotes tumor growth and invasion

through up-regulating HOXA1 and sequestering G9a/EZH2/Dnmts away

from the HOXA1 gene in glioblastoma multiforme. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 37:2652018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Kim CY, Oh JH, Lee JY and Kim MH: The

LncRNA HOTAIRM1 promotes tamoxifen resistance by mediating HOXA1

expression in ER+ breast cancer cells. J Cancer. 11:3416–3423.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Wang XQ and Dostie J: Reciprocal

regulation of chromatin state and architecture by HOTAIRM1

contributes to temporal collinear HOXA gene activation. Nucleic

Acids Res. 45:1091–1104. 2017.

|

|

92

|

Usman M, Li A, Wu D, Qinyan Y, Yi LX, He G

and Lu H: The functional role of lncRNAs as ceRNAs in both ovarian

processes and associated diseases. Noncoding RNA Res. 9:165–177.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Kim S: LncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory

networks in skin aging and therapeutic potentials. Front Physiol.

14:13031512023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Lin Y, Wen H, Yang B, Wang C and Liang R:

Integrated bioinformatics and validation to construct

lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA network in status epilepticus. Heliyon.

9:e222052023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Jiang M, Wang Z, Lu T, Li X, Yang K, Zhao

L, Zhang D, Li J and Wang L: Integrative analysis of long noncoding

RNAs dysregulation and synapse-associated ceRNA regulatory axes in

autism. Transl Psychiatry. 13:3752023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Wang X, Liu Y and Lei P: LncRNA HOTAIRM1

promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived

mesenchymal stem cells by targeting miR-152-3p/ETS1 axis. Mol Biol

Rep. 50:5597–5608. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Wang G, Yu Y and Wang Y: Effects of

propofol on neuroblastoma cells via the HOTAIRM1/miR-519a-3p axis.

Transl Neurosci. 13:57–69. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Han W, Wang S, Qi Y, Wu F, Tian N, Qiang B

and Peng X: Targeting HOTAIRM1 ameliorates glioblastoma by

disrupting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and serine

metabolism. iScience. 25:1048232022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Chen W, Liu J, Ge F, Chen Z, Qu M, Nan K,

Gu J, Jiang Y, Gao S and Liao Y: Long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1

promotes immunosuppression in sepsis by inducing T cell exhaustion.

J Immunol. 208:618–632. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Peng WX, Koirala P and Mo YY:

LncRNA-mediated regulation of cell signaling in cancer. Oncogene.

36:5661–5667. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Ge T, Gu X, Jia R, Ge S, Chai P, Zhuang A

and Fan X: Crosstalk between metabolic reprogramming and

epigenetics in cancer: Updates on mechanisms and therapeutic

opportunities. Cancer Commun (Lond). 42:1049–1082. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Zhou Y, Wu Q, Long X, He Y and Huang J:

lncRNA HOTAIRM1 Activated by hoxa4 drives huvec proliferation

through direct interaction with protein partner HSPA5.

Inflammation. 47:421–437. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Guo H, Li T and Sun X: LncRNA HOTAIRM1,

miR-433-5p and PIK3CD function as a ceRNA network to exacerbate the

development of PCOS. J Ovarian Res. 14:192021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Dahariya S, Raghuwanshi S, Thamodaran V,

Velayudhan SR and Gutti RK: Role of long non-coding RNAs in

human-induced pluripotent stem cells derived megakaryocytes: A p53,

HOX antisense intergenic RNA Myeloid 1, and miR-125b interaction

study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 384:92–101. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Li YR, Yan WJ, Cai LL and Deng XL: Effect

of down-regulation of LncRNA-HOTAIRM1 to proliferation, apoptosis

and KIT/AKT pathway of jurkat cells. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za

Zhi. 29:1123–1128. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

106

|

Liu WB, Li GS, Shen P, Li YN and Zhang FJ:

Long non-coding RNA HOTAIRM1-1 silencing in cartilage tissue

induces osteoarthritis through microRNA-125b. Exp Ther Med.

22:9332021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Tollis P, Vitiello E, Migliaccio F,

D'Ambra E, Rocchegiani A, Garone MG, Bozzoni I, Rosa A, Carissimo

A, Laneve P and Caffarelli E: The long noncoding RNA nHOTAIRM1 is

necessary for differentiation and activity of iPSC-derived spinal

motor neurons. Cell Death Dis. 14:7412023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Segal D, Coulombe S, Sim J and Josée

Dostie J: A conserved HOTAIRM1-HOXA1 regulatory axis contributes

early to neuronal differentiation. RNA Biol. 20:1523–1539. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Zamame Ramirez JA, Romagnoli GG and Kaneno

R: Inhibiting autophagy to prevent drug resistance and improve

anti-tumor therapy. Life Sci. 265:1187452021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Liang L, Gu W, Li M, Gao R, Zhang X, Guo C

and Mi S: The long noncoding RNA HOTAIRM1 controlled by AML1

enhances glucocorticoid resistance by activating RHOA/ROCK1 pathway

through suppressing ARHGAP18. Cell Death Dis. 12:7022021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Gu D, Tong M, Wang J, Zhang B, Liu J, Song

G and Zhu B: Overexpression of the lncRNA HOTAIRM1 promotes

lenvatinib resistance by downregulating miR-34a and activating

autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Discov Oncol. 14:662023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Chen L, Hu N, Wang C and Zhao H: HOTAIRM1

knockdown enhances cytarabine-induced cytotoxicity by suppression

of glycolysis through the Wnt/β-catenin/PFKP pathway in acute

myeloid leukemia cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 680:1082442020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Gustafson MP, Ligon JA, Bersenev A, McCann

CD, Shah NN and Hanley PJ: Emerging frontiers in immuno- and gene

therapy for cancer. Cytotherapy. 25:20–32. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Kaur R, Bhardwaj A and Gupta S: Cancer

treatment therapies: Traditional to modern approaches to combat

cancers. Mol Biol Rep. 50:9663–9676. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Hashemi M, Moosavi MS, Abed HM, Dehghani

M, Aalipour M, Heydari EA, Behroozaghdam M, Entezari M,

Salimimoghadam S, Gunduz ES, et al: Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA)

H19 in human cancer: From proliferation and metastasis to therapy.

Pharmacol Res. 184:1064182022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

McCabe EM and Rasmussen TP: lncRNA

involvement in cancer stem cell function and epithelial-mesenchymal

transitions. Semin Cancer Biol. 75:38–48. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|