Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most

prevalent subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), characterized by

aggressive mature B-cell tumors with heterogeneous clinical

features and varying responses to treatment (1–3). Only

60% of patients achieve long-term remission, and approximately

one-third experience treatment resistance or relapse, despite

conventional immunochemotherapy with a rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) regimen (4).

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) (5) is the leading prognostic tool for

clinical decision-making, and incorporates age, stage, lactate

dehydrogenase (LDH) level, performance status and extranodal

involvement. Although gene expression profiling and molecular

markers (including MYD88, TP53 and KMT2D) provide useful prognostic

information (6,7), their high expense, technical

requirements and time-consuming procedures prevent widespread

clinical use. Therefore, there is an urgent need for accessible and

cost-effective prognostic biomarkers.

By inhibiting antitumor immunity, promoting

angiogenesis and providing trophic factors for malignant lymphocyte

survival, monocytes and tumor-associated macrophages play important

roles in the pathophysiology of lymphomas (8,9).

Absolute monocyte counts (AMCs) have demonstrated prognostic value

in lymphoma (10,11), but have important clinical

limitations. Patients with DLBCL frequently present with

significant hematological variations, including treatment-induced

leukopenia or leukocytosis, bone marrow involvement,

infection-related white blood cell (WBC) fluctuations (12) and corticosteroid effects (13). These factors can substantially alter

absolute counts while potentially masking the underlying immune

composition.

By contrast, monocyte percentage (MP) offers several

distinct advantages: First, MP reflects the relative immune cell

composition and the proportional balance between immunosuppressive

monocytes and other immune populations, which may more accurately

represent tumor-immune microenvironment dynamics given that

monocytes play pivotal roles in shaping immunosuppressive

environments through various mechanisms (14). Second, MP is less susceptible to the

confounding effects of total WBC variations, providing a more

stable measure across different clinical scenarios (15). Third, MP may eliminate variability

from laboratory-specific reference ranges, enhancing

standardization and applicability across diverse healthcare

settings. Despite these theoretical advantages and the established

role of monocytes in lymphoma pathogenesis, MP has been

underexplored as an independent prognostic marker in DLBCL.

Therefore, the present retrospective cohort study

was conducted to evaluate the prognostic value of MP in patients

with newly diagnosed DLBCL treated with R-CHOP, and to assess its

independent prognostic significance beyond established markers,

including analysis of IPI and AMC.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

The present study included patients with newly

diagnosed DLBCL who received R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

hydroxydaunorubicin, tumor protein, and prednisone) treatment and

evaluation at Ganzhou People's Hospital (Ganzhou, China) between

January 2015 and December 2023. This study was conducted in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the

Ganzhou People's Hospital Ethics Committee (Ganzhou, China;

approval no. PJB2025-210-01). The requirement for informed consent

was waived by the ethics committee due to the retrospective nature

of the study and the use of fully anonymized clinical data.

Exclusion criteria included autoimmune diseases, a human

immunodeficiency virus-positive status, inflammatory conditions,

other lymphomas (such as follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma)

or leukemias and previous chemoradiotherapy. The following clinical

baseline data were retrieved from medical records during diagnosis:

Sex, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Score (16), Ann Arbor tumor stage (17), molecular sub-type, extranodal

infiltration number, lactate dehydrogenase level, IPI score, bone

marrow involvement and pathology results, WBC count, MP, AMC,

absolute lymphocyte count, red blood cell (RBC) count, blood

platelet (PLT) count, hemoglobin level, fibrinogen level, LDH,

albumin level and immunophenotype. Clinicopathological criteria

from either an initial lymph node biopsy or an external biopsy of

the primary nodes were used to confirm the DLBCL diagnosis. The

molecular subtype of DLBCL was classified into germinal center

B-cell-like (GCB) and non-GCB subtypes using the Hans algorithm,

which is based on immunohistochemical staining for CD10, BCL6 and

MUM1 (6) When diagnosing DLBCL, an

automated complete blood count (CBC) is frequently used to measure

the MP in peripheral WBCs.

Grouping strategy

Patients were divided into two groups based on MP,

with the clinical laboratory standard upper limit threshold of 10%

used as the primary cutoff; however, receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) analysis using the Youden Index suggested

using an optimal threshold of 8.7%. The 10% threshold represents

the established upper limit for normal MP and defines monocytosis

in standard clinical practice. To evaluate how cutoff selection

affected prognostic performance, a sensitivity analysis was

conducted comparing the two thresholds. Participants were

classified based on a cut-off value of MP (≤10 and >10%) for the

primary analysis.

Follow-up and outcome definitions

Follow-up was conducted by reviewing medical

histories or through telephone conversations. Progression-free

survival (PFS) time was defined as the interval between the date of

diagnosis and disease progression, recurrence, death or the end of

follow-up. Overall survival (OS) time was defined as the interval

between diagnosis and death or the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as n (%), and

continuous variables that are normally distributed are presented as

mean ± standard deviation. Continuous variables with skewed

distribution are presented as median (interquartile range). All

comparisons were performed with appropriate statistical tests

(χ2/Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and

unpaired t-test/Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables) with

P-values reported.

A multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression

model was used to adjust for potential confounders to estimate the

association of MP with OS and PFS in newly diagnosed DLBCL. The

lower group (≤10%) was the reference group. Model 1 had no

adjustments, whereas model 2 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 3

was further adjusted for Ann Arbor tumor stage, molecular subtype,

double expression, extranodal infiltration number, IPI score, bone

marrow involvement, Epstein-Barr virus infection, WBC count, RBC

count, PLT count, hemoglobin level, fibrinogen level and albumin

level. To determine the association of MP with OS and PFS, the

cumulative Kaplan-Meier curve was plotted. Eventually, by

calculating the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and 95% confidence

intervals (CIs) for outcomes, the predictive power of IPI scores

and their combination with the MP was evaluated. P<0.05 was used

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the

software package R (http://www.R-project.org) and Empower Stats

(http://www.empowerstats.com; X&Y

Solutions, Inc.).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 169 newly diagnosed DLBCL patients were

included in the present study, with a median age of 59.0±13.0 years

(median, 61.0 years; IQR 53.0-68.0) and 53.8% male predominance.

Based on the optimal cutoff of 10% MP, 117 patients (69.2%) were

classified in the low MP group and 52 (30.8%) in the high MP group

(Table I).

| Table I.Association between MP and clinical

characteristics in patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma. |

Table I.

Association between MP and clinical

characteristics in patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma.

| Variables | Total (n=169) | MP ≤10% (n=117) | MP >10%

(n=52) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.738 |

|

Female | 78 (46.2) | 53 (45.3) | 25 (48.1) |

|

| Male | 91 (53.8) | 64 (54.7) | 27 (51.9) |

|

| Age, years |

|

|

| 0.757 |

| ≤60 | 75 (44.4) | 51 (43.6) | 24 (46.2) |

|

|

>60 | 94 (55.6) | 66 (56.4) | 28 (53.8) |

|

| Mean ± SD | 59.0±13.0 | 59.0±13.2 | 59.2±12.7 | 0.893 |

| Median (IQR) | 61.0 (53.0,

68.0) | 61.0 (53.0,

68.0) | 61.0 (53.0,

69.0) | 0.969 |

| Hans algorithm, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| GCB | 112 (66.3) | 70 (59.8) | 42 (80.8) |

|

|

Non-GCB | 57 (33.7) | 47 (40.2) | 10 (19.2) |

|

| Double expression, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.149 |

| No | 126 (74.6) | 91 (77.8) | 35 (67.3) |

|

| Yes | 43 (25.4) | 26 (22.2) | 17 (32.7) |

|

| Ann Arbor clinical

stage, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.016 |

|

I–II | 27 (16.0) | 24 (20.5) | 3 (5.8) |

|

|

III–IV | 138 (81.7) | 89 (76.1) | 49 (94.2) |

|

| NA | 4 (2.4) | 4 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| IPI score, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.278 |

| 0 | 12 (7.1) | 10 (8.5) | 2 (3.8) |

|

| 1 | 34 (20.1) | 26 (22.2) | 8 (15.4) |

|

| 2 | 41 (24.3) | 27 (23.1) | 14 (26.9) |

|

| 3 | 43 (25.4) | 32 (27.4) | 11 (21.2) |

|

| 4 | 27 (16.0) | 14 (12.0) | 13 (25.0) |

|

| 5 | 12 (7.1) | 8 (6.8) | 4 (7.7) |

|

| Extranodal

involvement, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.062 |

|

<2 | 73 (43.2) | 45 (38.5) | 28 (53.8) |

|

| ≥2 | 96 (56.8) | 72 (61.5) | 24 (46.2) |

|

| Bone marrow

infiltration, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.769 |

| No | 145 (85.8) | 101 (86.3) | 44 (84.6) |

|

|

Yes | 24 (14.2) | 16 (13.7) | 8 (15.4) |

|

| Combined with

cancer, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.703 |

| No | 161 (95.3) | 112 (95.7) | 49 (94.2) |

|

|

Yes | 8 (4.7) | 5 (4.3) | 3 (5.8) |

|

| EBV DNA >500

copies/ml, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.253 |

| No | 136 (80.5) | 98 (83.8) | 38 (73.1) |

|

|

Yes | 24 (14.2) | 14 (12.0) | 10 (19.2) |

|

| NA | 9 (5.3) | 5 (4.3) | 4 (7.7) |

|

| Mean WBC ± SD,

×109/l | 6.4±3.1 | 6.9±3.3 | 5.1±2.4 | <0.001 |

| AMC,

×109/la | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | <0.001 |

| ALC,

×109/la | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | <0.001 |

| Mean RBC ± SD,

×1012/l | 4.2±0.8 | 4.3±0.7 | 3.8±0.9 | <0.001 |

| Mean Hb ± SD,

g/l | 122.9±25.5 | 127.5±23.2 | 112.3±27.3 | <0.001 |

| PLT,

×109/la | 219.0

(159.0-284.0) | 234.0

(188.0-308.0) | 172.5

(122.2-246.2) | <0.001 |

| Mean Fbg ± SD,

g/l | 3.8±1.3 | 3.8±1.2 | 3.8±1.4 | 0.980 |

| Mean Alb ± SD,

g/l | 40.7±5.7 | 41.6±5.4 | 38.6±6.0 | 0.001 |

| Ferritin,

ng/mla | 261.2

(148.9-464.9) | 244.7

(144.1-440.6) | 317.0

(168.2-748.0) | 0.045 |

| LDH,

U/la | 233.0

(182.5-448.5) | 208.0

(172.0-327.0) | 344.5

(209.2-550.8) | 0.001 |

| LDH >ULN, n

(%) | 69 (40.8) | 36 (30.8) | 33 (63.5) | <0.001 |

Baseline characteristics were generally balanced

between groups regarding age, sex, double expression, IPI score,

extranodal involvement, bone marrow infiltration, concurrent

malignancy, EBV DNA levels and fibrinogen levels (all P>0.05).

However, significant differences emerged in several key features.

Patients with high MP more frequently presented with advanced stage

III–IV disease (94.2 vs. 76.1%; P=0.016) and GCB subtype (80.8 vs.

59.8%; P=0.008). Laboratory analyses revealed that high MP was

associated with elevated LDH (median, 344.5 vs. 208.0 U/l;

P=0.001), with 63.5% exceeding the upper limit of normal LDH level

compared with 30.8% in the low MP group (P<0.001). Despite lower

total WBC counts (5.1×109/l vs. 6.9×109/l;

P<0.001), the high MP group had a higher AMC

(0.7×109/l vs. 0.4×109/l; P<0.001) but

lower ALC (0.9×109/l vs. 1.4×109/l;

P<0.001), indicating a shift in immune cell composition.

Additionally, high MP was associated with lower hemoglobin (112.3

vs. 127.5 g/l; P<0.001), PLTs (172.5×109/l vs.

234.0×109/l; P<0.001) and albumin (38.6 vs. 41.6 g/l;

P=0.001) levels, and a higher ferritin level (317.0 vs. 244.7

ng/ml; P=0.045), suggesting greater disease burden.

Univariate analysis

Using univariate Cox regression analysis, various

prognostic factors that affect PFS and OS were analyzed (Table II). PFS was strongly correlated

with Ann Arbor stages III to IV (HR=8.30, 95% CI: 1.14-60.23;

P=0.036), bone marrow involvement (HR=3.05, 95% CI: 1.64-5.68;

P<0.001), IPI scores >3 (HR=4.64, 95% CI: 2.68-8.02;

P<0.001), RBC (HR=0.59, 95% CI: 0.42-0.83; P=0.002), hemoglobin

(HR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.98-1.00; P=0.016), PLT count (HR=1.00, 95% CI:

0.99-1.00; P=0.023) and albumin level (HR=0.95, 95% CI: 0.91-1.00;

P=0.048). Similarly, OS was strongly associated with Ann Arbor

stages III to IV (HR=7.45, 95% CI: 1.24-54.68; P=0.002), IPI scores

>3 (HR=5.12, 95% CI: 1.62-16.18; P=0.005) and WBC count

(HR=0.75, 95% CI: 0.58-0.97; P=0.028).

| Table II.Univariate analysis of

clinicopathological parameters for OS and PFS time in patients with

newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. |

Table II.

Univariate analysis of

clinicopathological parameters for OS and PFS time in patients with

newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

|

| PFS | OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Female | 1.28

(0.74-2.21) | 0.383 | 1.12

(0.40-3.14) | 0.831 |

| Age >60

years | 1.31

(0.76-2.26) | 0.335 | 1.00

(0.96-1.04) | 0.840 |

| Ann Arbor stage

III–IV | 8.30

(1.14-60.23) | 0.036 | 7.45

(1.24-54.68) | 0.002 |

| Hans type | 1.54

(0.87-2.72) | 0.137 | 1.08

(0.27-4.26) | 0.917 |

| IPI scores | 4.64

(2.68-8.02) | <0.001 | 5.12

(1.62-16.18) | 0.005 |

| Extranodal sites

≥2 | 1.20

(0.69-2.10) | 0.516 | 0.20

(0.41-3.54) | 0.744 |

| Bone marrow

involvement | 3.05

(1.64-5.68) | <0.001 | 1.96

(0.61-6.29) | 0.260 |

| EBV DNA >500

copies | 1.17

(0.46-3.00) | 0.736 | 2.10

(0.25-17.61) | 0.493 |

| Combined with

tumor | 2.26

(0.81-6.32) | 0.119 | 1.81

(0.40-8.29) | 0.442 |

| WBC | 0.92

(0.82-1.02) | 0.120 | 0.75

(0.58-0.97) | 0.028 |

| RBC | 0.59

(0.42-0.83) | 0.002 | 0.63

(0.35-1.15) | 0.133 |

| Hb | 0.99

(0.98-1.00) | 0.016 | 0.98

(0.97-1.00) | 0.072 |

| PLT | 1.00

(0.99-1.00) | 0.023 | 1.00

(0.99-1.00) | 0.383 |

| Fbg | 1.02

(0.81-1.29) | 0.843 | 0.64

(0.37-1.10) | 0.106 |

| Alb | 0.95

(0.91-1.00) | 0.048 | 0.92

(0.84-1.00) | 0.064 |

| Ferritins | 1.00

(1.00-1.00) | 0.337 | 1.00

(1.00-1.00) | 0.492 |

Cutoff value determination

The following performance metrics were observed by

comparing the ROC-optimal (8.7%) and clinical (10%) cutoffs: The

8.7% cutoff demonstrated higher sensitivity (62.3 vs. 45.3%),

Youden Index (0.286 vs. 0.194) and negative predictive value (NPV)

(79.4 vs. 74.8%), whereas the 10% cutoff showed superior

specificity (74.1 vs. 66.4%). Between the 8.7 and 10% cutoffs,

positive predictive values were comparable (45.8 vs. 44.4%;

difference 1.4%). The 10% threshold was selected for its clinical

practicality as a round number and higher specificity, which

minimizes false-positive risk stratification despite slightly lower

sensitivity and NPV. Table SI

summarizes the performance comparison.

In order to ascertain the predictive value of the MP

in peripheral blood, MP was measured from peripheral blood samples

collected at initial diagnosis. In the multivariate Cox regression

analysis, MP was analyzed both as a continuous variable and as a

dichotomized variable using a 10% cutoff.

Multivariate analysis

When MP was analyzed as a continuous variable, it

demonstrated consistent prognostic significance across all three

models. In model 1, each 1% increase in MP was associated with

worse PFS (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05-1.15; P<0.001) and OS (HR,

1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.22; P=0.003) (Table III). In model 2, MP remained

significantly associated with PFS (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.03-1.15;

P=0.001) and OS (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05-1.24; P=0.002). In model 3,

MP continued to be an independent prognostic factor for both PFS

(HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05-1.25; P=0.002) and OS (HR, 2.15; 95% CI,

1.15-4.03; P=0.017) (Table

III).

| Table III.Multivariate Cox proportional

analysis of MP for the prediction of OS and PFS in patients with

DLBCL. |

Table III.

Multivariate Cox proportional

analysis of MP for the prediction of OS and PFS in patients with

DLBCL.

| A, Model 1 |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| Multivariate

analysis PFS | Multivariate

analysis OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Parameter | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| MP (per 1%

increase) | 1.10

(1.05-1.15) | <0.001 | 1.13

(1.04-1.22) | 0.003 |

| MP (>10 vs.

≤10%) | 1.94

(1.12-3.37) | 0.018 | 3.73

(1.01-13.77) | 0.049 |

|

| B, Model

2 |

|

|

| Multivariate

analysis PFS | Multivariate

analysis OS |

|

|

|

|

|

Parameter | HR (95%

CI) | P-value | HR (95%

CI) | P-value |

|

| MP (per 1%

increase) | 1.09

(1.03-1.15) | 0.001 | 1.14

(1.05-1.24) | 0.002 |

| MP (>10 vs.

≤10%) | 1.79

(1.02-3.13) | 0.042 | 3.92

(1.05-14.72) | 0.043 |

|

| C, Model

3 |

|

|

| Multivariate

analysis PFS | Multivariate

analysis OS |

|

|

|

|

|

Parameter | HR (95%

CI) | P-value | HR (95%

CI) | P-value |

|

| MP (per 1%

increase) | 1.14

(1.05-1.25) | 0.002 | 2.15

(1.14-4.03) | 0.017 |

| MP (>10 vs.

≤10%) | 2.54

(1.08-5.99) | 0.033 | 5.34

(0.57-50.14) | 0.143 |

When MP was analyzed as a dichotomized variable with

10% as the cutoff, patients with MP >10% showed significantly

worse outcomes compared with those with MP ≤10% (reference group).

In model 1, elevated MP (>10%) was associated with worse PFS

(HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.12-3.37; P=0.018) and OS (HR, 3.73; 95% CI,

1.01-13.77; P=0.049). In model 2, the associations remained

significant for both PFS (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.02-3.13; P=0.042) and

OS (HR, 3.92; 95% CI, 1.05-14.72; P=0.043). In model 3, MP remained

an independent predictor of PFS, compared with the reference group

(HR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.08-5.99; P=0.033). By contrast, no significant

difference was observed when comparing OS to the reference group

(HR, 5.34; 95% CI, 0.57-50.14; P=0.143) (Table III).

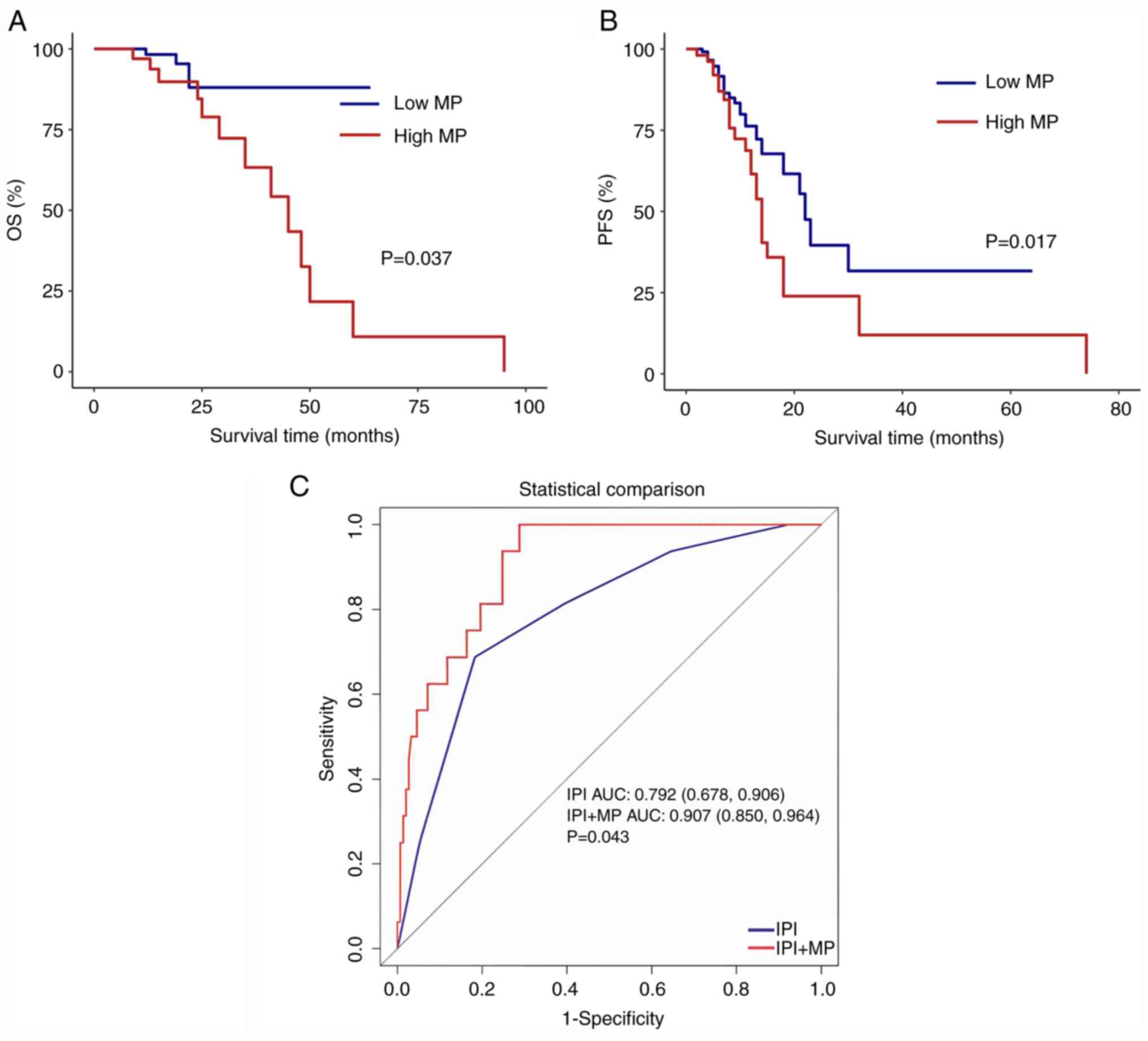

Survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to compare

the two groups (≤10 and >10%). Both PFS (P=0.017) and OS

(P=0.037) were poor in the high MP group compared with those in the

low MP group (Fig. 1A and B).

To evaluate the predictive value of MP and assess

the impact of identifying multiple biomarkers on OS prediction, ROC

curves were plotted for patients with OS outcomes. Compared with

the international IPI score for assessing risk factors,

incorporating the MP increased the AUC (0.792 vs. 0.907; P=0.043)

(Fig. 1C).

Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that MP at

diagnosis may be utilized as a biomarker to predict survival in

patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL treated with R-CHOP. A high MP

was associated with poor PFS and OS. Additionally, MP provided

prognostic information independent of IPI score, and it may

increase the predictive effectiveness of outcomes when combined

with IPI score. Although the prognostic value of AMC in DLBCL has

been reported (10,11), the precise function of MP as a

readily available biomarker remains unknown. To the best of our

knowledge, the present study is the first to systematically

evaluate the value of MP as an independent prognostic indicator.

Compared with AMC, MP provides a standardized assessment method

that is unaffected by factors such as hemodilution or

hemoconcentration, offering better clinical applicability.

The tumor microenvironment and host immunity are

crucial factors in DLBCL outcomes (18,19).

Monocytes and monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells may

suppress host antitumor immunity through several mechanisms,

including secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., IL-10,

TGF-β), depletion of amino acids via arginase-1 and inducible

nitric oxide synthase, production of reactive oxygen species, and

expression of immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1 (20). Additionally, myeloid cells have been

implicated in fostering tumor angiogenesis within the tumor

microenvironment (21).

Furthermore, immune-derived myeloid cells produced by tumors

directly promote tumor growth and vascularization by their

differentiation into endothelial cells (22). In human umbilical vein endothelial

cell cultures, monocytes actively promote endothelial cell

proliferation through C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1/fractalkine

interaction (23).

Beyond promoting tumor cell angiogenesis, monocytes

can suppress the host's antitumor immune response. T-cell

co-inhibitory ligand B7-homolog 1 (also known as programmed

death-ligand 1) is expressed in the tumor microenvironment by

peripheral blood monocytes and their progeny (24). Moreover, lymphoma B cells can

recruit monocytes via chemokine C-C motif ligand 5, which enhances

the survival and proliferation of neoplastic B lymphocytes while

suppressing the proliferation of healthy T cells (25). Finally, monocytes are an essential

source of soluble mediators, such as B lymphocyte stimulator, that

promote the growth and survival of healthy and malignant B cells

(26,27). It follows that monocytes promote the

growth of malignant lymphocytes in both T-cell and B-cell NHL

(8,28). The mechanism underlying the

association between monocytes and rituximab-mediated B-cell

lymphoma outcomes was elucidated by these cited earlier

investigations.

Different molecular subtypes and clinical features

may affect the association between MP and DLBCL outcomes. Germinal

center B-cell-like (GCB) and non-GCB DLBCL subtypes exhibit

fundamentally different tumor microenvironments and inflammatory

profiles. In contrast to GCB subtypes, non-GCB subtypes may promote

more monocyte recruitment and activation owing to their

constitutive NF-κB activation and elevated inflammatory signaling

(29,30). By promoting angiogenesis and

suppressing the immune system, these activated monocytes can

differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages, which aid in tumor

growth (31).

Double expressor lymphomas

(MYC+/BCL2+) are a physiologically aggressive

subtype with distinct immune characteristics. MYC overexpression

has been associated with changes in immune cell recruitment and

function, which may affect the differentiation state of circulating

monocytes (32,33). By altering apoptotic pathways in

both tumor cells and immune effector cells, the concomitant

upregulation of BCL2 may further modulate the tumor-immune

interface (34). Similarly, more

aggressive disease biology and systemic inflammatory responses that

may influence MP and function are frequently reflected in

extranodal involvement.

Importantly, the multivariate analysis in the

present study demonstrated that MP maintained independent

prognostic value even after adjusting for the established molecular

markers (GCB subtype and double expressor status) and clinical

variables (extranodal involvement). The novelty of this study lies

in, to the best of our knowledge, the first demonstration that MP

retains independent prognostic value after adjusting for molecular

markers (GCB subtype and double expressor status) and clinical

variables. This suggests that MP may capture biological information

not reflected by existing molecular and clinical stratification

methods. Thus, MP may reflect the complex interplay between

systemic immune status and local tumor microenvironment dynamics,

capturing further biological information beyond the current

molecular and clinical stratification approaches.

In the present study, patients with DLBCL who had a

high MP at diagnosis tended to have poor PFS and OS. After

controlling for other key negative prognostic variables,

multivariate analysis retained the predictive value of MP. These

results support the adverse prognostic impact of elevated MP on

B-cell NHL and are in line with earlier research (19,35,36).

The majority of studies have suggested that the AMC may be

considered a prognostic indicator for DLBCL. However, the precise

association between a high MP acquired from a CBC and a poor

prognosis remains debatable. Notably, monocytes may contribute to

tumor immunity and the tumor microenvironment as vital components

of the immune system. Hemoglobin levels and PLT counts are

independent predictors of poor 5-year OS and disease-free survival

rates in patients with DLBCL (37).

Similarly, Li et al (38)

reported that decreased peripheral blood PLT count may be a factor

associated with a poor prognosis in newly diagnosed DLBCL. The

present results, which suggested that the PLT count was a

protective factor for PFS, are in line with this previous research.

Using univariate Cox regression analysis, the present study

demonstrated positive associations between hemoglobin levels and

PFS. However, the hemoglobin level did not affect OS. Unlike gene

expression profiling or immunohistochemistry, which require complex

testing, MP is a simple indicator readily obtainable from a routine

CBC, yet its prognostic value has been underrecognized. To the best

of our knowledge, the present study is the first to validate MP as

an independent prognostic biomarker and demonstrate its ability to

enhance the predictive power of the National Comprehensive Cancer

Network (NCCN)-IPI.

Despite increasing evidence emphasizing the

association between the tumor microenvironment and lymphoma, it is

challenging to incorporate tumor microenvironment-related

prognostic variables into standard clinical practice. This is

because gene expression profiles or immunohistochemical data often

form the basis for most research estimating such associations. By

contrast, the MP data achieved from a CBC may be widely used and

easily incorporated into clinical practice. The important

contribution of the present study is identifying MP as a unique

prognostic indicator from among numerous hematological parameters.

While previous studies have focused on AMC, MP as a relative

proportion indicator offers several advantages: i) It is unaffected

by individual blood volume variations; ii) it reflects the relative

balance of immune cell composition; and iii) it may more accurately

reflect tumor-associated systemic immune status changes.

Furthermore, MP, a novel prognostic metric derived from CBC that is

easily accessible in clinical data, presents information

independent of NCCN-IPI. Additionally, it may provide further

predictive value when combined with NCCN-IPI.

The present study has several limitations. First,

the limited number of OS events (n=16; 9.5%) resulted in large

confidence intervals and low statistical power for multivariate

analysis. Post-hoc power analysis suggested that ~50 OS events

would be required to detect the observed effect size with 80%

power. This explains why the hazard ratio remained high (HR, 5.34)

but had wide confidence intervals (95% CI, 0.57-50.14) in the

non-significant multivariate Cox model (P=0.143), compared with the

significant univariate Kaplan-Meier analysis (P=0.037). Second,

although the association between MP and DLBCL prognosis was

assessed using multivariate Cox regression analysis, the influence

of unaccounted-for confounding factors could not be excluded

entirely. Third, although the 10% MP cutoff was based on laboratory

reference ranges, it may not be optimal for prognostic

stratification and warrants further investigation in larger cohorts

using ROC-derived thresholds. Therefore, larger prospective

multi-center studies with longer follow-up periods are warranted to

confirm the predictive efficacy of MP, an easily available and

affordable parameter for determining patient prognosis in those

with DLBCL.

In conclusion, the present cohort study demonstrated

a significant association between elevated MP and poor survival

outcomes. Furthermore, combining MP with IPI may improve the

predictive efficiency of these results.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the talent project of

2025 ‘Technology + Medical’ Joint Plan Project/Ganzhou Science and

Technology Bureau (grant no. 2025YLCE0072).

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study's findings are

available online at DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.25151393.

Authors' contributions

XX and CZ contributed to the study design and data

collection. XX performed the statistical analysis and data

analysis. CZ was involved in the writing and revision of the

manuscript. XX and CZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Both authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The studies involving human participants were

reviewed and approved by the Ganzhou People's Hospital Ethics

Committee (Ganzhou, China; approval no. PJB2025-210-01). The

requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee

due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of fully

anonymized clinical data.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu X, Zeng L, Liu J, Huang Y, Yao H,

Zhong J, Tan J, Gao X, Xiong D and Liu L: Artesunate induces

ferroptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by targeting

PRDX1 and PRDX2. Cell Death Dis. 16:5132025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Barraclough A, Hawkes E, Sehn LH and Smith

SM: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 42:e32022024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Liang XJ, Song XY, Wu JL, Liu D, Lin BY,

Zhou HS and Wang L: Advances in multi-omics study of prognostic

biomarkers of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Biol Sci.

18:1313–1327. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Poletto S, Novo M, Paruzzo L, Frascione

PMM and Vitolo U: Treatment strategies for patients with diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 110:1024432022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Prognostic Factors Project: A predictive model for aggressive

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 329:987–994. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC,

Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Müller-Hermelink HK, Campo E,

Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, et al: Confirmation of the molecular

classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by

immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 103:275–282.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Shen R, Fu D, Dong L, Zhang MC, Shi Q, Shi

ZY, Cheng S, Wang L, Xu PP and Zhao WL: Simplified algorithm for

genetic subtyping in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 8:1452023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wilcox RA, Wada DA, Ziesmer SC, Elsawa SF,

Comfere NI, Dietz AB, Novak AJ, Witzig TE, Feldman AL, Pittelkow MR

and Ansell SM: Monocytes promote tumor cell survival in T-cell

lymphoproliferative disorders and are impaired in their ability to

differentiate into mature dendritic cells. Blood. 114:2936–2944.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Shivakumar L and Ansell S: Targeting

B-lymphocyte stimulator/B-cell activating factor and a

proliferation-inducing ligand in hematologic malignancies. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma. 7:106–108. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

10.Shang CY, Wu JZ, Ren YM, Liang JH, Yin

H, Xia Y, Wang L, Li JY, Li Y and Xu W: Prognostic significance of

absolute monocyte count and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Ann Hematol.

102:359–367. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mohsen A, Taalab M, Abousamra N and Mabed

M: Prognostic significance of absolute lymphocyte count, absolute

monocyte count, and absolute lymphocyte count to absolute monocyte

count ratio in follicular non-hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma Leuk. 20:e606–e615. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Conlan MG, Armitage JO, Bast M and

Weisenburger DD: Clinical significance of hematologic parameters in

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma at diagnosis. Cancer. 67:1389–1395. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Jia WY and Zhang JJ: Effects of

glucocorticoids on leukocytes: Genomic and non-genomic mechanisms.

World J Clin Cases. 10:7187–7194. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ugel S, Canè S, De Sanctis F and Bronte V:

Monocytes in the tumor microenvironment. Annu Rev Pathol.

16:93–122. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Arneth B: Complete blood count: Absolute

or relative values? J Hematol. 5:49–53. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF,

Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA; Alliance, Australasian

Leukaemia; Lymphoma Group and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ;

et al: Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and

response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: The Lugano

classification. J Clin Oncol. 32:3059–3068. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zeng J, Zhang X, Jia L, Wu Y, Tian Y and

Zhang Y: Pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratios predict

AIDS-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma overall survival. J Med

Virol. 93:3907–3914. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kharroubi DM, Nsouli G and Haroun Z:

Potential prognostic and predictive role of monocyte and lymphocyte

counts on presentation in patients diagnosed with diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma. Cureus. 15:e356542023.

|

|

20

|

Condamine T and Gabrilovich DI: Molecular

mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell

differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 32:19–25. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yang F, Lee G and Fan Y: Navigating tumor

angiogenesis: Therapeutic perspectives and myeloid cell regulation

mechanism. Angiogenesis. 27:333–349. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zha C, Yang X, Yang J, Zhang Y and Huang

R: Immunosuppressive microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia:

Overview, therapeutic targets and corresponding strategies. Ann

Hematol. 103:4883–4899. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kim JA, Kwak JY, Eunjung Y, Lee J, Park Y

and Broxmeyer HE: Fractalkine/CX3CR1 signaling promotes angiogenic

potentials in CX3CR1 expressing monocytes. Blood. 128:25072016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Song H, Chen L, Pan X, Shen Y, Ye M, Wang

G, Cui C, Zhou Q, Tseng Y, Gong Z, et al: Targeting tumor

monocyte-intrinsic PD-L1 by rewiring STING signaling and enhancing

STING agonist therapy. Cancer Cell. 43:503–518.e10. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Le Gallou S, Lhomme F, Irish JM, Mingam A,

Pangault C, Monvoisin C, Ferrant J, Azzaoui I, Rossille D,

Bouabdallah K, et al: Nonclassical monocytes are prone to migrate

into tumor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front Immunol.

12:7556232021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

He B, Chadburn A, Jou E, Schattner EJ,

Knowles DM and Cerutti A: Lymphoma B cells evade apoptosis through

the TNF family members BAFF/BLyS and APRIL. J Immunol.

172:3268–3279. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Novak AJ, Grote DM, Stenson M, Ziesmer SC,

Witzig TE, Habermann TM, Harder B, Ristow KM, Bram RJ, Jelinek DF,

et al: Expression of BLyS and its receptors in B-cell non-Hodgkin

lymphoma: Correlation with disease activity and patient outcome.

Blood. 104:2247–2253. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Seiffert M, Schulz A, Ohl S, Döhner H,

Stilgenbauer S and Lichter P: Soluble CD14 is a novel

monocyte-derived survival factor for chronic lymphocytic leukemia

cells, which is induced by CLL cells in vitro and present at

abnormally high levels in vivo. Blood. 116:4223–4230. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young

RM, Romesser PB, Kohlhammer H, Lamy L, Zhao H, Yang Y, et al:

Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Nature. 463:88–92. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D and Sun SC: NF-κB

signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

2:170232017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, Farinha P, Han

G, Nayar T, Delaney A, Jones SJ, Iqbal J, Weisenburger DD, et al:

Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's

lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 362:875–885. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, Do R, Walz S,

Fitzgerald KN, Gouw AM, Baylot V, Gütgemann I, Eilers M and Felsher

DW: MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and

PD-L1. Science. 352:227–231. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kortlever RM, Sodir NM, Wilson CH,

Burkhart DL, Pellegrinet L, Brown Swigart L, Littlewood TD and Evan

GI: Myc cooperates with Ras by programming inflammation and immune

suppression. Cell. 171:1301–1315.e14. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Xu-Monette ZY, Wei L, Fang X, Au Q, Nunns

H, Nagy M, Tzankov A, Zhu F, Visco C, Bhagat G, et al: Genetic

subtyping and phenotypic characterization of the immune

microenvironment and MYC/BCL2 double expression reveal

heterogeneity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res.

28:972–983. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

von Hohenstaufen KA, Conconi A, de Campos

CP, Franceschetti S, Bertoni F, Margiotta CG, Stathis A, Ghielmini

M, Stussi G, Cavalli F, et al: Prognostic impact of monocyte count

at presentation in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol.

162:465–473. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tadmor T, Bari A, Sacchi S, Marcheselli L,

Liardo EV, Avivi I, Benyamini N, Attias D, Pozzi S, Cox MC, et al:

Monocyte count at diagnosis is a prognostic parameter in diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma: Results from a large multicenter study

involving 1191 patients in the pre- and post-rituximab era.

Haematologica. 99:125–130. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Troppan KT, Melchardt T, Deutsch A,

Schlick K, Stojakovic T, Bullock MD, Reitz D, Beham-Schmid C, Weiss

L, Neureiter D, et al: The significance of pretreatment anemia in

the era of R-IPI and NCCN-IPI prognostic risk assessment tools: A

dual-center study in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Eur J

Haematol. 95:538–544. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Li M, Xia H, Zheng H, Li Y, Liu J, Hu L,

Li J, Ding Y, Pu L, Gui Q, et al: Red blood cell distribution width

and platelet counts are independent prognostic factors and improve

the predictive ability of IPI score in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma patients. BMC Cancer. 19:10842019. View Article : Google Scholar

|