Introduction

Multiple primary malignant neoplasms (MPMNs) are

defined as the presence of two or more histologically distinct

primary cancer types arising in separate organs or anatomical sites

in the same patient (1–4). Although the reported incidence of

MPMNs in China remains low (ranging from 0.4 to 2.4%) it has

steadily increased in recent years owing to advances in imaging and

diagnostic methodologies (4–6). The

widely accepted diagnostic framework combines the original Warren

criteria (1) with the modifications

from Liu et al (2), which

stipulate that: i) Each neoplasm must be confirmed as malignant by

histopathology; ii) each neoplasm must display unique pathological

features; iii) tumors must develop in non-contiguous locations; and

iv) each tumor must demonstrate an independent pattern of

metastasis, thereby excluding secondary spread or recurrence.

Nevertheless, clinicians frequently encounter challenges in

differentiating multiple primary tumors from metastases due to

overlapping clinical presentations, limitations of conventional

imaging and difficulties in accurately determining tumor origin on

pathological examination (7). These

factors contribute to increased rates of both misdiagnosis and

underdiagnosis.

In the present case report, the case of a

79-year-old male patient diagnosed with multiple primary malignant

neoplasms is described. The coexistence of distinct malignancies

posed substantial diagnostic challenges, particularly in

differentiating primary lesions from potential metastatic disease.

The present study highlights the utility of

99mTc-labeled methylene diphosphonate

(99mTc-MDP) three-phase bone imaging in providing

integrated diagnostic information that facilitates accurate

evaluation and clinical decision-making.

Case report

Chief complaint

A 79-year-old male patient, who had a forearm lesion

present for >5 years with recurrence noted in the past 6 months,

was admitted to the Department of Joint Surgery at the Third

Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou,

China) in March 2024.

History of present illness

The patient first noticed a painless nodular lesion

on the left forearm in 2020 without any apparent cause. After local

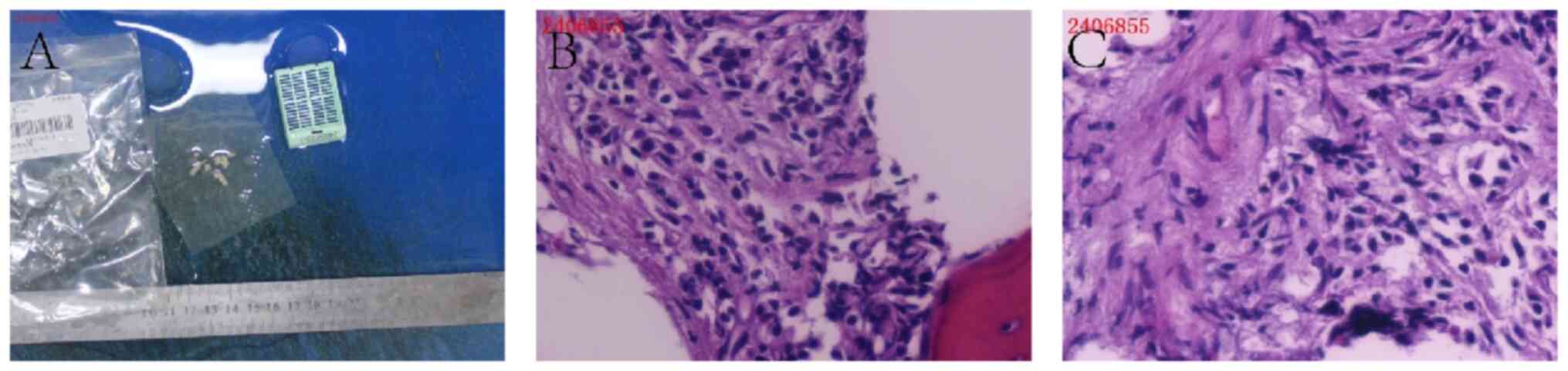

excision, histopathology revealed nodular fasciitis (Fig. S1). In 2021 (1 years later) the

lesion recurred at the same site and grew to 6×4 cm. Despite the

notable increase in size, the patient remained asymptomatic and

underwent a skin tumor resection at the Department of Joint

Surgery, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical

University. The excised tissue was fixed in 4% neutral

phosphate-buffered formaldehyde solution at room temperature

(~25°C) for 24 h. The specimens were sectioned at a thickness of 4

µm and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) reagents

[Roche Diagnostics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.] at 25°C for 8 h. The

stained slides were examined under a light microscope (Olympus

BX43; Olympus Corporation) at ×100 magnification, and

representative images were captured for histopathological

evaluation. Histopathological analysis revealed fibrous tissue

proliferation, spindle-shaped tumor cells with nuclear atypia and

inflammatory cell infiltration, accompanied by myxoid degeneration,

hemorrhage and frequent mitotic figures (4 per high-power field)

(Fig. S2). The differential

diagnoses included nodular fasciitis and malignant mesenchymal

tumor. At this time, the clinical diagnosis was a cutaneous tumor,

and no further specific treatment was administered following the

excision.

In December 2023 (onset time), the patient noticed

two new lesions at the original site, measuring 3×3×2 and 2×2×1 cm.

The overlying skin showed erythema and swelling, but no additional

symptoms were reported. In March 2024, the patient presented to the

Surgical Outpatient Clinic at the Third Affiliated Hospital of

Guangzhou Medical University for evaluation. Throughout the course

of the illness, the patient maintained normal bowel movements and

stable mental status, but experienced urinary frequency and

urgency, and occasional hematuria, without significant changes in

sleep, appetite or weight.

Past medical and family history

The patient had no history of trauma, fractures,

tumors or other relevant medical conditions. The patient had no

family history of malignancy, and no history of exposure to

carcinogenic chemicals, radiation or toxic substances. The patient

also reported no history of smoking, alcohol use or illicit drug

use.

Physical examination

On March 26, 2024, a physical examination of the

left forearm revealed a 6×4 cm subcutaneous lesion with

well-defined borders and an indurated, rubbery consistency. The

lesion was partially movable upon palpation and was without any

signs of inflammation. Palpation revealed two additional lesions in

the left forearm. The larger lesion measured 3×3×2 cm with

well-defined borders and the smaller measured 2×2×1 cm with poorly

defined borders. A longitudinal surgical scar was noted on the skin

surface of the left forearm.

Preoperative laboratory tests

The preoperative laboratory tests revealed the

following results: Red blood cell count, 2.88×1012/l

(reference range, 4.3-5.8×1012/l); and hemoglobin, 81

g/l (reference range, 130–175 g/l). The white blood cell count,

platelet count, coagulation profile and liver and kidney function

tests were all within the normal limits.

Preoperative imaging

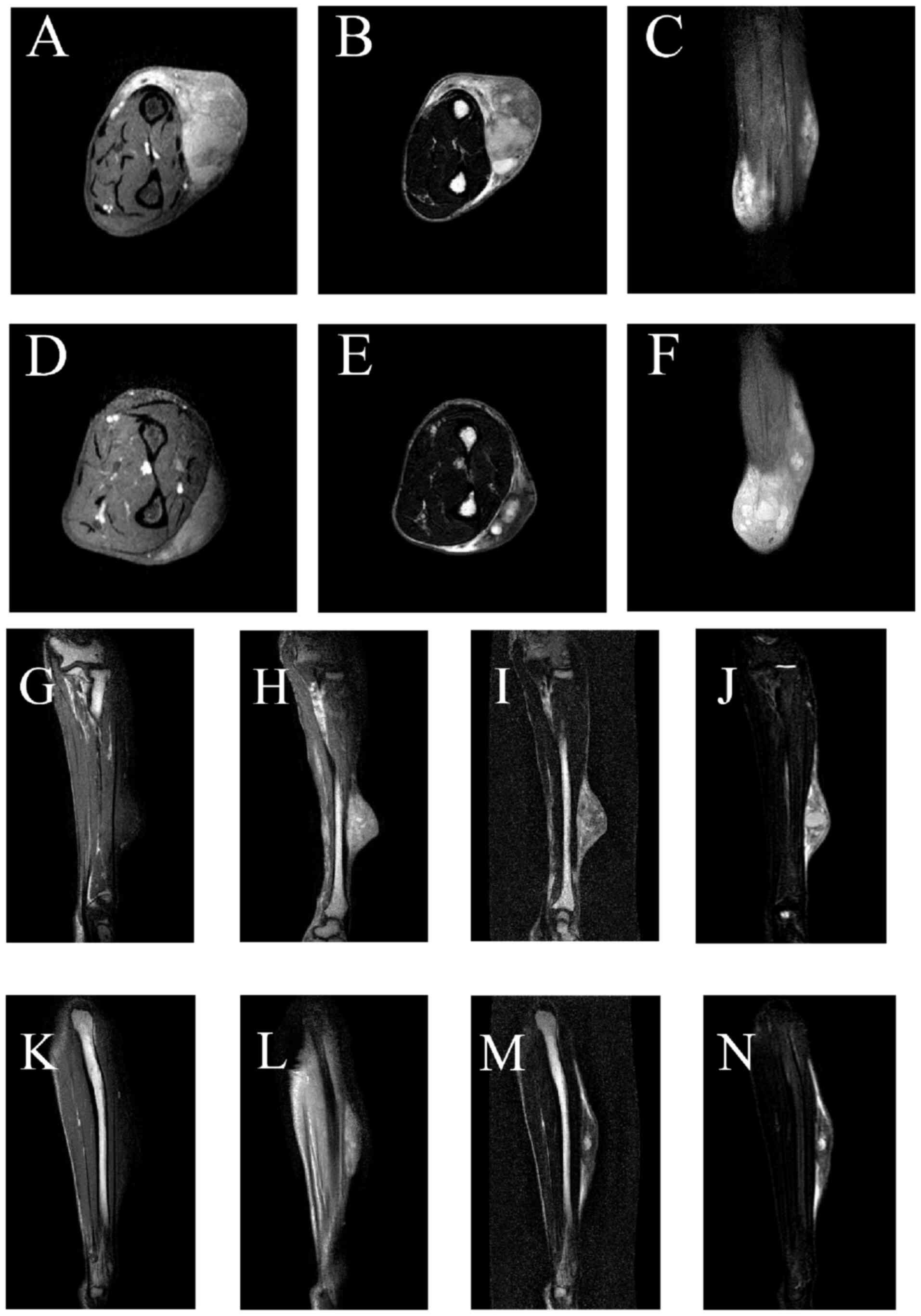

In April 2024, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of

the left forearm demonstrated multiple irregular subcutaneous

lesions on the dorsal aspect measuring 46×27×60 and 38×12×72 mm.

These lesions showed hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging and

heterogeneous signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging and proton

density-weighted imaging, along with notable heterogeneous

enhancement and poorly defined borders on contrast-enhanced imaging

(Fig. 1). Despite the indistinct

margins, the lesions remained well-demarcated from the adjacent

muscles. The osseous structures appeared normal with an intact and

continuous cortex. No evidence of destructive bony changes, osseous

metastasis or abnormal signal intensity was observed. T1-weighted

contrast-enhanced imaging revealed no abnormal bone enhancement

(Fig. 1C, F, H and L). Although

X-ray, thin-section bone window computed tomography (CT) and 3D-CT

were not performed due to financial constraints and clinical

priorities, the absence of peri-tumoral bone destruction on MRI

definitively excluded direct osseous invasion, strongly suggesting

local recurrence of the soft-tissue sarcoma.

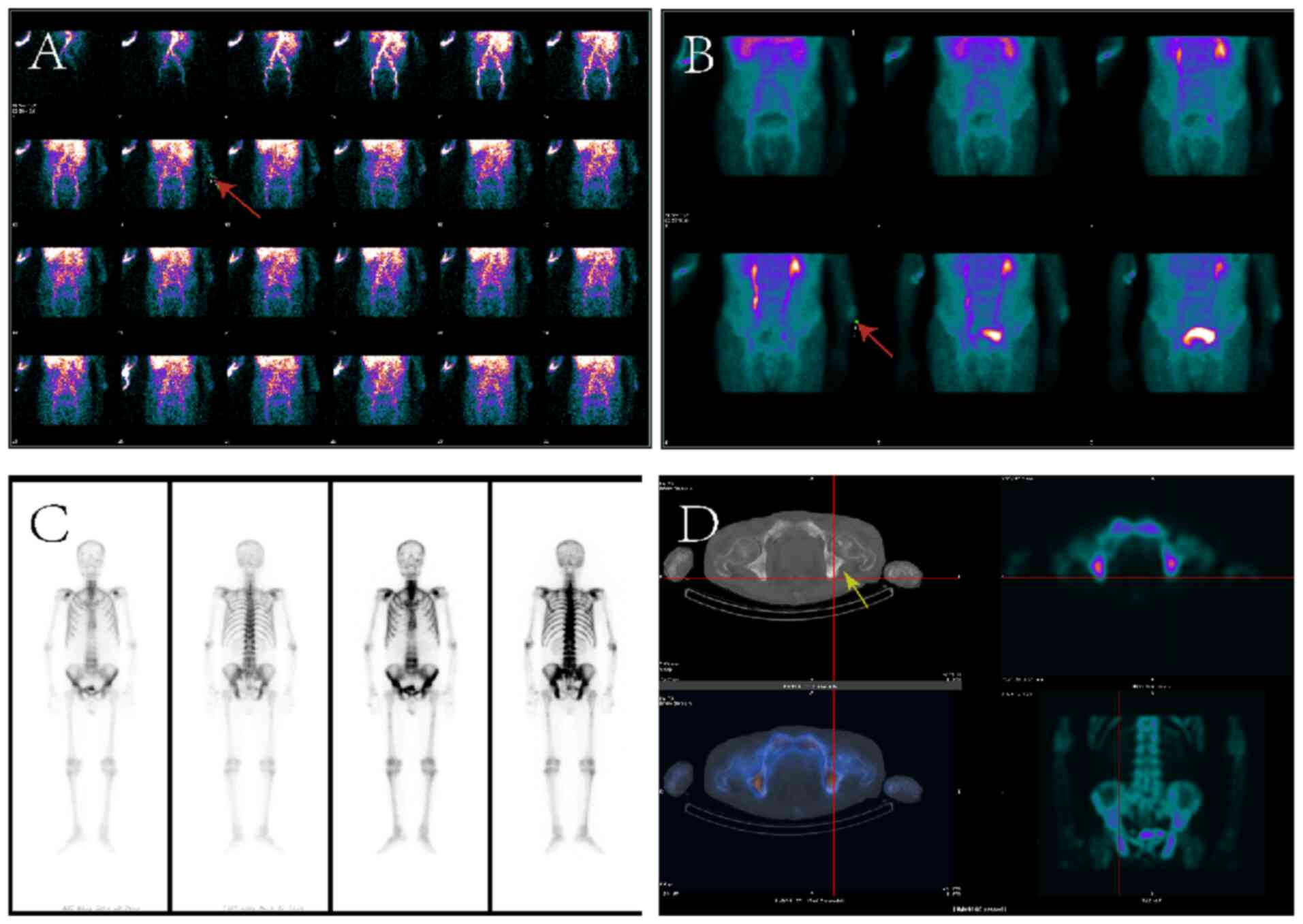

Concurrent 99mTc-MDP three-phase bone

imaging revealed markedly increased perfusion to the left forearm

following radiotracer injection, along with localized abnormal

radiotracer uptake during the blood pool phase, suggesting the

possibility of soft tissue pathology (Fig. 2A and B). Whole-body bone imaging

demonstrated diffusely increased skeletal radiotracer uptake, with

multiple irregularly shaped, heterogeneous foci exhibiting moderate

to high intensity in the cervical and thoracolumbar spine,

bilateral ribs, pelvis and proximal femurs (Fig. 2C and D). Such imaging results are

consistent with widespread bone metastasis, indicating extensive

involvement and heterogeneous uptake across the skeletal system.

The kidneys exhibited minimal tracer uptake, and the bladder showed

limited concentration, resulting in a characteristic ‘superscan’

pattern (Fig. 2C and D). Single

photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT fusion imaging confirmed multiple

osteoblastic changes in the thoracolumbar spine, ribs and pelvis,

along with soft-tissue lesions in the dorsal left forearm showing

reduced 99mTc-MDP uptake, without evidence of

significant bone involvement (Fig. 2C

and D). Due to the financial constraints and advanced age of

the patient, X-ray, thin-section bone window CT and 3D CT imaging

were not performed.

Treatment process and follow-up

pathology

Following the 99mTc-MDP whole-body

three-phase bone scan, the left forearm lesion was highly suspected

to be malignant, with augmented blood flow and increased bone

metabolic activity. Nevertheless, the extensive bone metastases,

indicative of multiple secondary lesions, are atypical for

fibrosarcoma. In April 2024, a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test

revealed a markedly elevated total PSA level of 563.864 ng/ml

(reference range for age >80 years, 0–8 ng/ml), raising a strong

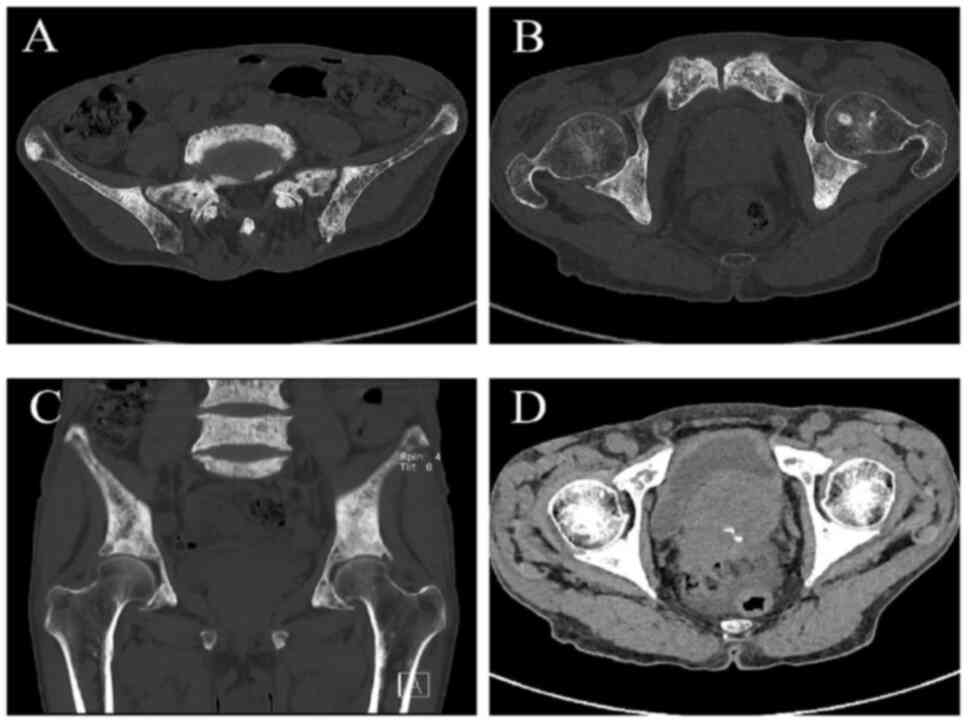

suspicion of an underlying malignancy. A subsequent CT scan

demonstrated heterogeneous bone density with multiple sclerotic and

lytic lesions in the hips and lumbar vertebrae, findings that are

highly indicative of metastatic bone disease (Fig. 3A-C). Additionally, significant

prostate enlargement was identified (Fig. 3D), which, in conjunction with the

elevated PSA levels and the extent of skeletal involvement,

provided compelling evidence supporting the diagnosis of advanced

prostate cancer. Pathological examination of the pubic bone biopsy

confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma consistent with a prostatic

primary origin. The diagnosis of advanced prostate adenocarcinoma

had been established previously, as aforementioned.

After ruling out surgical contraindications, the

patient underwent wide excision of the left forearm tumor with skin

grafting, vacuum sealing drainage closure and a pubic bone biopsy

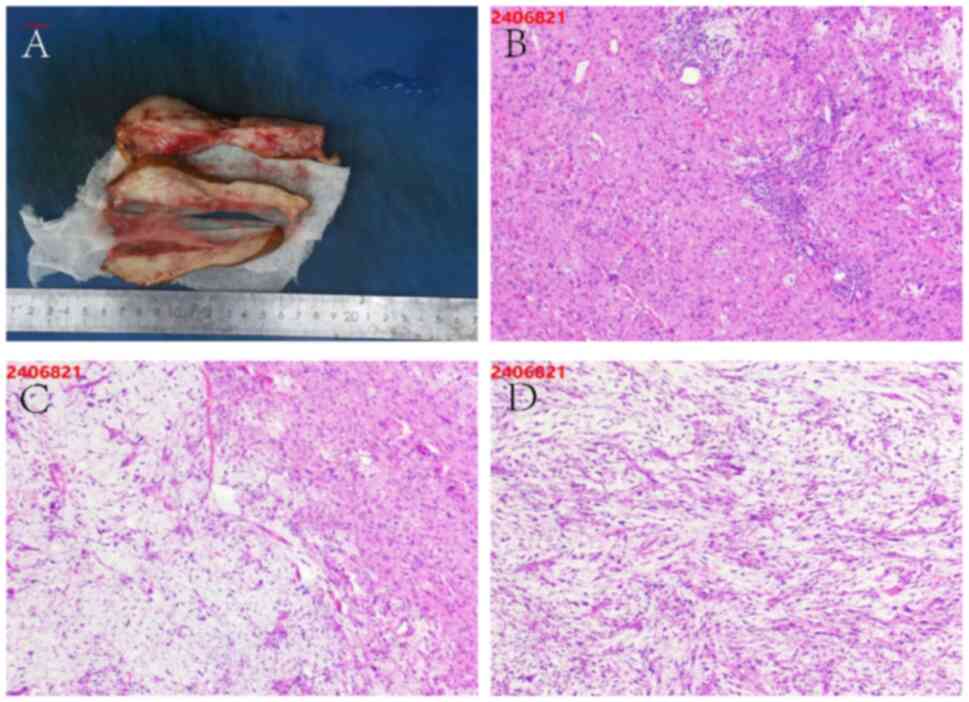

in April 2024 (Fig. 4A). The

operation was successful without obvious postoperative acute

complications. The excised tissue was paraffin-embedded after

fixation in 4% neutral phosphate-buffered formaldehyde solution at

room temperature (~25°C) for 24 h. Sections were cut at a thickness

of 4 µm and stained with H&E using reagents supplied by Roche

Diagnostics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. at 25°C for 8 h. The stained

slides were examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX43;

Olympus Corporation) and representative images were captured for

histopathological evaluation. Histopathological analysis of the

left forearm tumor demonstrated key features of a high-grade

malignant mesenchymal tumor, suggesting a diagnosis of high-grade

myxofibrosarcoma (MFS) (4). The

tumor was characterized by spindle cells with marked atypia,

frequent mitotic figures and multinucleated giant cells, along with

myxoid degeneration within the stroma and extensive inflammatory

cell infiltration, findings consistent with high-grade MFS

(Fig. 4B-D). Additionally, the

poorly defined margins, combined with notable cellular

pleomorphism, further supported the diagnosis of a highly

aggressive malignant mesenchymal tumor.

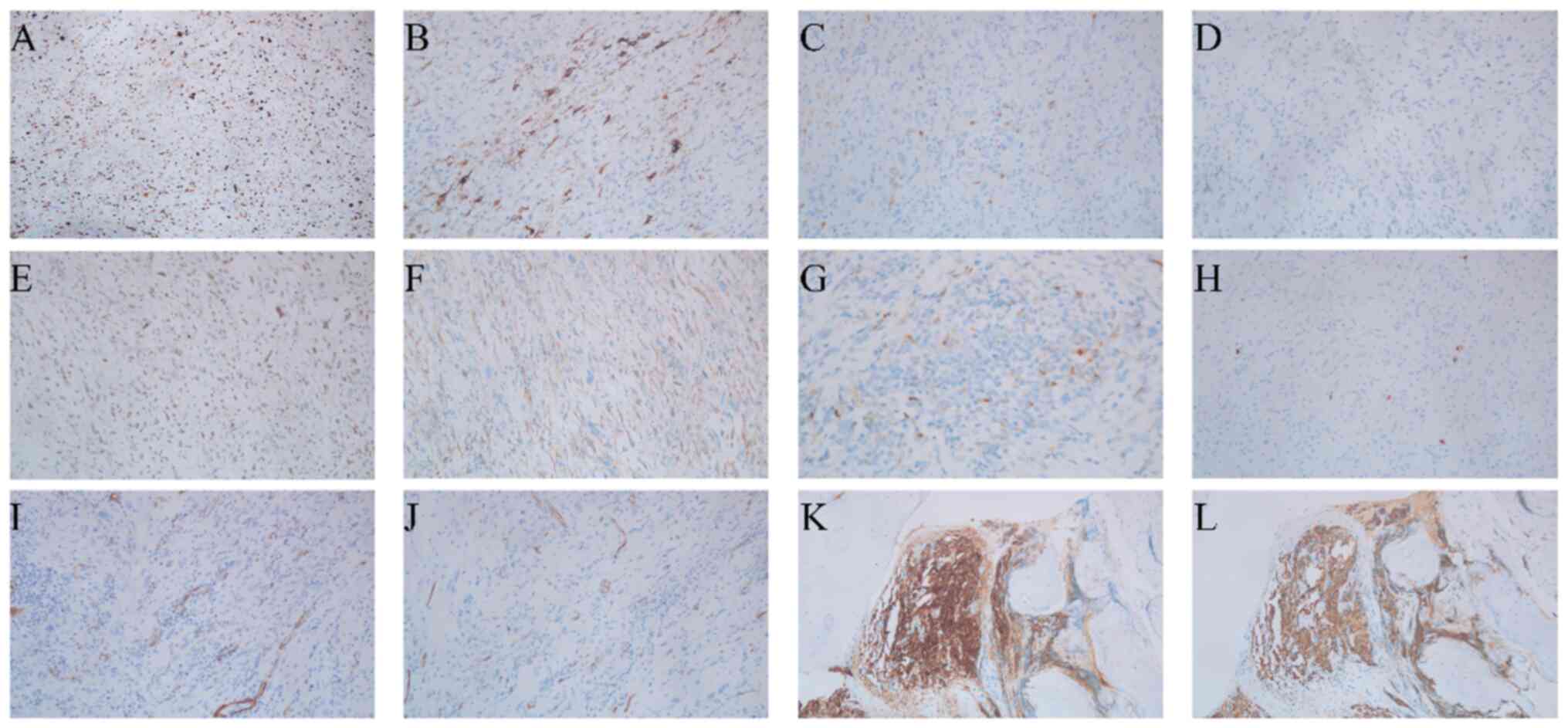

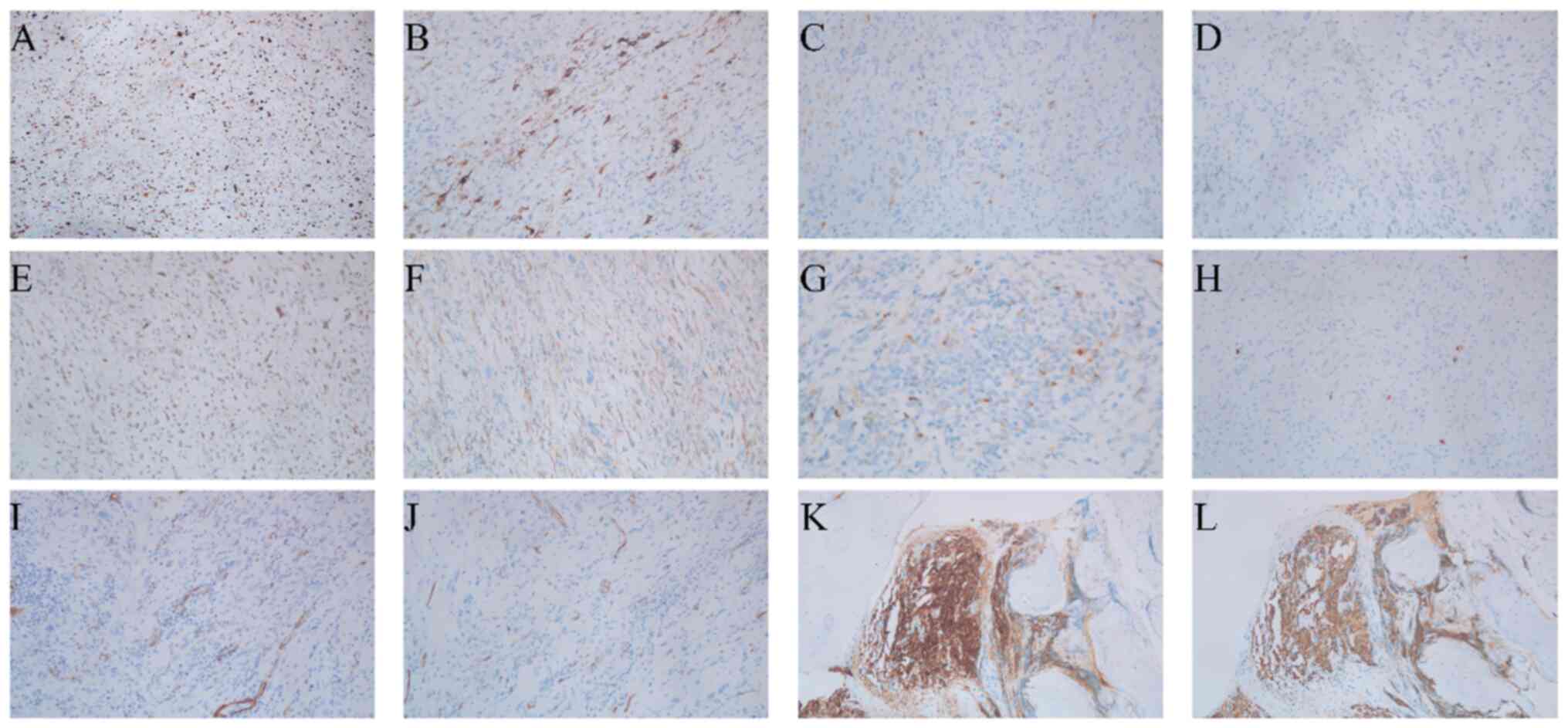

Immunohistochemical analysis of the left forearm

tumor revealed a high proliferative index (Ki-67, 60%) with focal

cytoplasmic desmin expression and scattered p16 immunoreactivity

(Fig. 5A-C). Tumor cells

demonstrated wild-type p53 nuclear expression pattern and weak MDM2

positivity (Fig. 5D and E).

β-catenin exhibited preserved membranous localization (Fig. 5F). Notably, pan-tropomyosin receptor

kinase (pan-TRK) staining showed weak focal cytoplasmic positivity

in 10% of tumor cells without nuclear expression (Fig. 5G). S-100 highlighted scattered

interstitial cells, whereas smooth muscle actin (SMA) and CD34

positivity confirmed vascular components (Fig. 5H-J). Finally, the tumor was negative

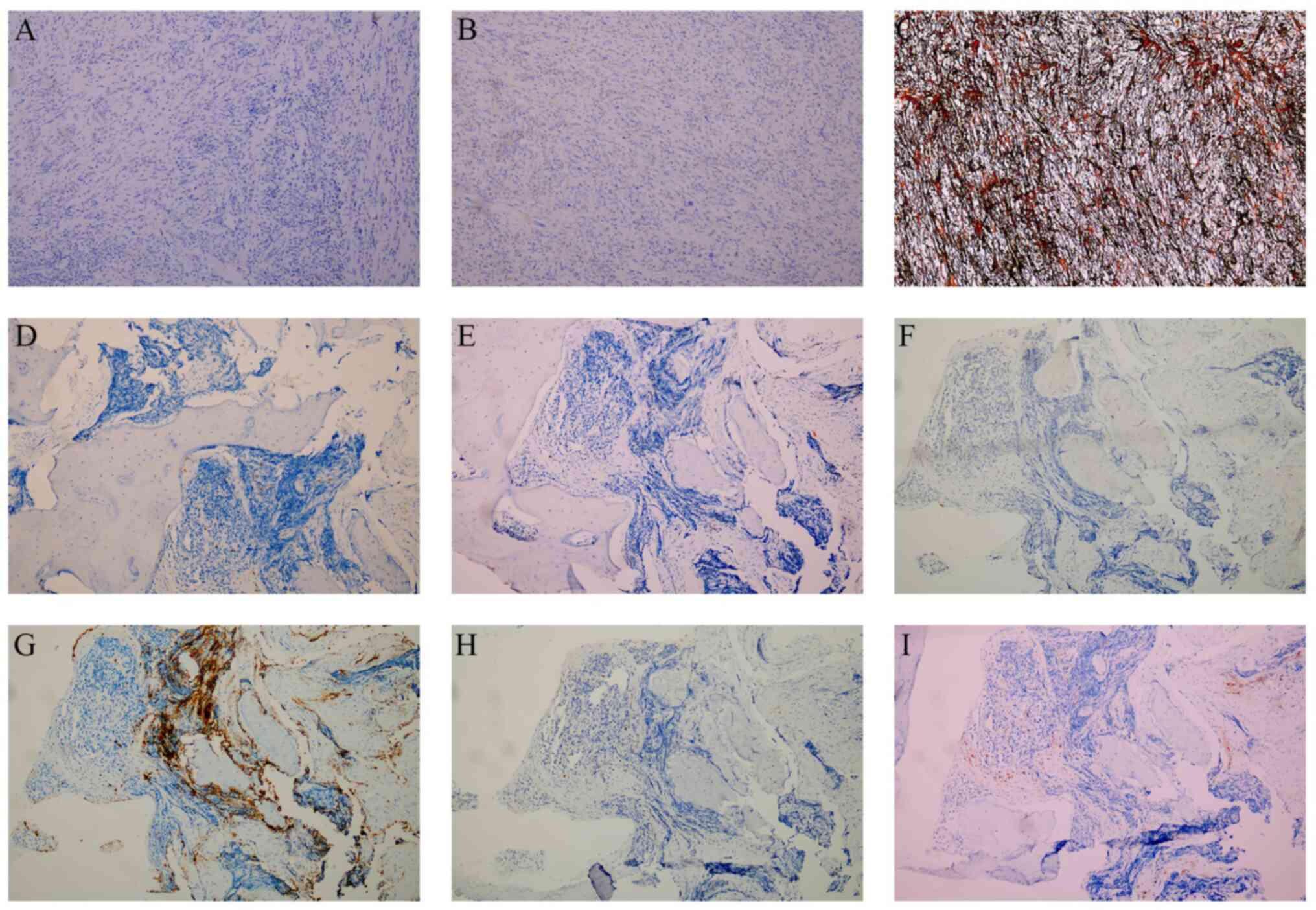

for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and SRY-box transcription

factor 10 (SOX10), while the reticulin stain demonstrated delicate

fibers encircling individual tumor cells (Fig. 6A-C).

| Figure 5.Representative immunohistochemical

staining of myxofibrosarcoma and pubic bone metastasis. (A) Ki-67,

(B) desmin, (C) p16, (D) p53, (E) MDM2, (F) β-catenin, (G)

Pan-tropomyosin receptor kinase, (H) S-100, (I) smooth muscle

actin, (J) CD34, (K) prostate-specific antigen, (L) cytokeratin.

Magnification, ×100. |

The tissue processing and immunohistochemical

staining procedures were as follows: Tumor tissues were fixed in 4%

neutral phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for 24 h at room

temperature (25°C) and subsequently paraffin-embedded. Paraffin

blocks were sectioned into 4-µm slices and baked at 65°C for 60 min

or overnight at 58°C. Sections were then deparaffinized in three

xylene baths (5–10 min each) and rehydrated through a descending

alcohol series (100, 95, 85 and 75% each for 2 min). Antigen

retrieval and immunostaining were performed using a BenchMark ULTRA

automated immunostainer (Roche Diagnostics) at 99°C for 16 min with

an immunohistochemistry antigen retrieval buffer (cat. no.

24005424569188; Roche Diagnostics). Endogenous peroxidase activity

was blocked using a peroxidase inhibitor for 5 min at 25°C. Primary

antibodies (prediluted; Roche Diagnostics) were incubated with the

sections at 25°C for 16 min, followed by the OptiView DAB Detection

Kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Sections were incubated with OptiView HQ Universal Linker

containing horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 8 min at 25°C, and

subsequently with HRP Multimer for 8 min to visualize staining.

The detailed information on the primary antibodies

used in this study is as follows. Ki-67 (Xiamen Talent Biomedical

Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. AM0241; clone MIB1; 1:200), SMA

(Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

kit-0006; clone 1A4; 1:100), Desmin [GeneTech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. GT225229; clone GTM2; 1:300], p16 (Beijing Zhongshan

Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. ZM-0205; clone 1C1;

1:300), p53 (Quan Hui Trading International Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

AQ20025; clone DO-7; 1:100), MDM2 (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. ZM-0425; clone 0TI17B3;

ready-to-use), ALK (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. TA800712; clone 0TI1H7; ready-to-use), CD34

(Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

kit-0004; clone QBEND/10; 1:100), β-Catenin (Beijing Zhongshan

Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. ZM-0442; clone

UMAB15; 1:300), pan-TRK (VENTANA Roche; cat. no. 08494665001; clone

EPR17341-4; ready-to-use), S-100 (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology

Development Co., Ltd.; cat. no. kit-0007; clone 4C4.9; 1:100),

SOX10 (Xiamen Talent Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

AM0417; clone SDM2; ready-to-use), PSA (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology

Development Co., Ltd.; cat. no. MAB-0146; clone ER-PR8; 1:50), CK

(Guangzhou Anbiping Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

IM069; clone AE1&AE3; 1:150), CD3 (Quan Hui Trading

International Co., Ltd.; cat. no. NCL-L-CD3-565; clone LN10; 1:50),

CD20 (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

kit-0001; clone L26; 1:1), CD61 (Agilent Technologies Singapore

International; cat. no. 8930248; clone VI-PL2; 1:100), CD235a

(Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

MAB-0603; clone JC159; ready-to-use), MPO (Quan Hui Trading

International Co., Ltd.; cat. no. AQ20285; polyclonal; 1:100) and

CD38 (Quan Hui Trading International Co., Ltd.; cat. no.

NCL-L-CD38-290; clone SPC32; 1:100).

Reticulin staining was performed on formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded sections using standard protocols. Slides were

counterstained with hematoxylin for 8 min and eosin for 1 min at

room temperature and examined under a light microscope (Olympus

BX53) at ×100 magnification.

Subsequently, histopathological analysis of the

pubic bone biopsy confirmed metastatic prostate cancer. Gross

examination revealed multiple gray-white specimens from the pubic

bone (Fig. 7A). Microscopically,

the fibrous tissue surrounding the lesion exhibited marked

proliferation and infiltrative growth of epithelioid cells,

characterized by abundant cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli and

pleomorphic features, consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of

prostatic origin (Fig. 7B and C).

Immunohistochemistry further demonstrated PSA and cytokeratin

positivity (Fig. 5K and L), while

hematopoietic markers (CD3, CD20 and MPO), megakaryocytic/erythroid

markers (CD61 and CD235a) and the plasma cell marker (CD38) were

uniformly negative (Fig. 6D-I).

These findings, in conjunction with the notably elevated serum PSA

levels and the clinical profile, conclusively supported a diagnosis

of advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Given the unequivocal

histopathological confirmation of osseous metastasis in this

octogenarian patient, a prostate biopsy was deemed unwarranted per

multidisciplinary consensus guidelines.

Postoperatively, the patient was treated with

cefuroxime sodium (1.5 g twice daily, i.v.), papaverine

hydrochloride (30 mg i.v.), celecoxib (0.2 g twice daily, p.o.) and

rabeprazole sodium (10 mg p.o.) for anti-infection, circulation

improvement, analgesia, and gastric protection, respectively. The

patient demonstrated favorable recovery and remained in stable

condition, with no other notable concurrent interventions. The

patient exhibited good treatment compliance and reported no

significant discomfort. By August 2024, the patient had achieved a

marked recovery, maintained a stable appetite and regular sleep

patterns, adhered to scheduled follow-up visits and continued a

routine regimen of bone pain medication. As of September 2025, the

patient remained alive, in stable condition and under regular

follow-up. The final diagnosis of metachronous multiple primary

malignant neoplasms (MMPMNs; high-grade myxofibrosarcoma of the

left forearm and prostate adenocarcinoma with osseous metastasis)

was thus established.

Discussion

MFS, formerly classified as a subtype of malignant

fibrous histiocytoma, predominantly affects patients aged 40 to 80

years (8,9). In total, two-thirds of MFS cases arise

in superficial soft tissues, typically the deep dermis and subcutis

of the limbs, while the remainder occur in deeper subfascial or

intramuscular locations (9,10). Histologically, MFS is distinguished

by a myxoid extracellular matrix, pleomorphic spindle cells and

characteristic curvilinear blood vessels (11). Patients with MFS exhibit a notably

elevated risk of developing subsequent primary malignancies

(12). Following the analysis of a

retrospective cohort, Tateishi et al (13) reported 5- and 10-year cumulative

incidences of secondary cancers of 16.9%, significantly exceeding

rates seen in other sarcoma subtypes (hazard ratio, 2.34; 95%

confidence interval, 1.01-5.41; P=0.048). In that cohort, patients

with MFS who developed secondary malignancies exhibited a wide

spectrum of additional tumor types involving multiple organ

systems. The secondary cancers most frequently comprised

adenocarcinomas arising in the stomach, ovary, prostate, colon,

cecum, breast, kidney, lung and rectum. Other histological subtypes

included squamous cell carcinomas of the pharynx, tongue, gingiva

and esophagus, as well as transitional cell carcinoma of the

bladder and renal cell carcinoma of the kidney. These neoplasms

represented independent primary tumors coexisting with MFS rather

than metastatic lesions, with some diagnosed prior to and others

following the onset of sarcoma. This series also included a case of

metachronous prostate adenocarcinoma following MFS, mirroring the

observation of occult prostate cancer detected via superscan in the

present study.

Beyond the risk of additional primary tumors, MFS

poses its own clinical challenges due to aggressive behavior and

high local recurrence rates, particularly in high-grade tumors.

Recurrence rates for MFS rank among the highest of all soft-tissue

sarcomas, underscoring the necessity for rigorous surveillance

(14,15). Although distant metastases are less

frequent (occurring in 13–16% of cases), the lungs and brain are

the most common sites, with occasional spread to the small

intestine, pelvis, retroperitoneum, stomach, liver and adrenal

glands (16,17). In the present study, the paradoxical

finding of a superscan (indicating diffuse osteoblastic activity)

combined with intact cortical bone adjacent to the sarcoma and the

rarity of MFS metastasis to prostate or bone strongly supports the

diagnosis of multiple primary malignancies rather than metastatic

spread.

Following intravenous administration of

99mTc-MDP, nuclear imaging techniques such as SPECT and

positron emission tomography (PET) assess the skeletal

biodistribution of the tracer, mediated by its affinity for

hydroxyapatite in bone tissue. While physiological uptake in soft

tissues may occasionally occur, abnormal extraosseous radiotracer

accumulation warrants further investigation. Research highlights a

strong correlation between radiotracer deposition and malignancies,

primarily driven by metastatic spread or primary soft-tissue

tumors, reflecting its critical diagnostic application in

oncological settings (18–20). Soft-tissue tumors in the limbs are

frequently characterized by increased blood volume within malignant

tissues, driven by tumor-induced angiogenesis. As a result, this

vascular proliferation leads to abnormal tracer accumulation as the

enhanced and permeable vasculature facilitates tracer retention in

non-target regions, complicating the accuracy of imaging

interpretation (21).

A superscan represents a distinctive pattern

observed in three-phase bone imaging, characterized by diffuse and

intense skeletal uptake, and accompanied by markedly diminished

soft tissue and renal activity. While, under normal conditions, the

tracer uptake ratio between the skeletal system and kidneys is

~2:3, in cases of a superscan, this ratio may shift to as high as

17:3 (22), indicating significant

deviations from typical tracer distribution. Given the inherent

complexities involved in achieving objective quantification, the

accurate diagnosis of a superscan is particularly challenging and

often necessitates the specialized expertise and interpretive

skills of experienced nuclear medicine physicians (23). Superscan is frequently associated

with conditions that promote diffuse reactive bone formation, such

as bone metastases from malignancies and certain metabolic bone

diseases (24,25). Notably, this phenomenon has been

documented in the literature as an unexpected indicator of occult

prostate cancer, underscoring the critical role of bone

scintigraphy as a diagnostic alert for asymptomatic secondary

malignancies (26). Data indicate

that superscan occurs in 15–23% of patients with prostate cancer,

establishing the disease as the most common underlying cause.

Although other malignancies, including gastric and breast cancer,

are also capable of inducing superscan, their incidence remains

significantly lower by comparison (25). Given the broad differential

diagnosis associated with superscan, visual interpretation alone is

insufficient. Laboratory tests (such as serum calcium and alkaline

phosphatase), tumor markers and additional imaging are critical for

an accurate diagnosis.

In the present study, X-ray, thin-section

bone-window CT and 3D-CT were not performed for the patient due to

financial constraints and comorbidities, which limits the

anatomical assessment and the exclusion of microscopic bone

invasion. Future similar cases should incorporate these imaging

modalities to enhance lesion characterization and diagnostic

precision.

Although the present case lacked molecular

profiling, available data indicate key genetic alterations in both

malignancies (MFS and prostate cancer) that may reveal shared

oncogenic pathways. MFS often harbors TP53 mutations and CDKN2A

deletions, leading to disrupted cell-cycle control and genomic

instability, while prostate adenocarcinoma frequently features

androgen receptor amplification and PTEN loss, driving tumor growth

and metastatic potential (27,28).

Furthermore, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA; classically

upregulated in prostate cancer) is also detected in the

neovasculature of sarcomas (up to 35.3% in MFS), where it promotes

angiogenesis and may contribute to increased 99mTc-MDP

uptake in a superscan (29,30). Both tumor types express luteinizing

hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) receptors, suggesting potential

benefit from LHRH-targeted therapies (31). Emerging evidence implicates

dysregulated p53 signaling, PI3K/AKT pathway activation and an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment characterized by

tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and T-cell exhaustion as

possible common mechanisms underlying multiple primary malignancies

(32–34). Future studies should employ

comprehensive genomic sequencing and immune profiling to identify

overlapping driver mutations, clarify the role of PSMA-mediated

angiogenesis and LHRH pathways, and evaluate whether targeted or

immunomodulatory treatments can mitigate the risk of metachronous

tumors.

MPMNs within the same individual are identified by

the presence of distinct pathological features in each tumor

(1–4). Traditionally, the diagnosis of MPMN is

based on the Warren criteria (35)

and revisions by Liu et al (36). However, the Surveillance,

Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) and International Agency for

Research on Cancer/International Association of Cancer Registries

(IARC/IACR) guidelines have become integral to modern diagnostics,

serving to enhance and extend the criteria used for diagnosing

MPMNs. SEER emphasizes tumor histology, anatomical location,

laterality and the time interval between diagnoses, thereby

facilitating the identification of multiple independent primary

tumors (37). By contrast, the

IARC/IACR criteria are more conservative, typically registering

only one tumor per organ or paired organs, emphasizing histological

consistency and adopting a cautious approach to multiple tumors in

the same anatomical site (38).

Synchronous MPMNs (SMPMNs) are defined as two or

more primary malignancies diagnosed within 6 months, while those

diagnosed after 6 months are termed metachronous MPMNs (MMPMNs).

MMPMNs have a lower incidence but similar survival rate compared

with SMPMNs (3,5). In the present case, the patient was

diagnosed with MMPMNs, comprising high-grade myxofibrosarcoma of

the left forearm and prostate adenocarcinoma with osseous

metastasis, as the two malignancies were identified more than 6

months apart. Tumor growth patterns, treatment approaches and

individual variability can affect the timing of diagnosis. Data

suggest a median interval of 3.45-6.13 years between the diagnoses

of the first and second primary tumors in MMPMN, but the prognostic

relevance of this interval remains uncertain (5,6,39).

Regardless, early detection, precise diagnosis and prompt treatment

are critical to improving outcomes in MPMNs. While imaging

techniques such as SPECT/CT and PET/CT enhance diagnostic accuracy,

pathological examination remains the gold standard when MPMN cannot

be ruled out.

In the evaluation of MFS,

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT can

offer valuable metabolic information, while 99mTc-MDP

three-phase bone scintigraphy is traditionally used to detect

osteoblastic activity and assess potential bone metastases, often

demonstrating only minimal soft-tissue uptake (40). Although in the present study bone

scintigraphy revealed increased perfusion and focal

99mTc-MDP accumulation in the left forearm, suggestive

of soft-tissue malignancy, and produced a classic superscan pattern

indicative of diffuse skeletal involvement, it lacks the

specificity to distinguish primary sarcoma from metastatic disease.

By contrast, 18F-FDG PET/CT quantifies tumor glucose

metabolism, achieving sensitivity rates of >90% for soft-tissue

sarcomas compared with ~70% for planar bone scans, and can detect

microscopic cortical or marrow invasion that may be occult on bone

scintigraphy or MRI (41,42). In the present study,

18F-FDG PET/CT was not performed due to the advanced

age, frailty and financial constraints of the patient, which

constitutes a limitation of the diagnostic workup. While

99mTc-MDP SPECT/CT has high utility for detecting

widespread bone metastatic activity (superscan), its sensitivity

(~86.7%) and specificity (~98.8%) for prostate cancer bone

metastases are slightly inferior to those of

18Ffluorocholine PET/CT, which achieves a sensitivity of

up to 93.3% and a specificity of 100% in biochemical recurrence

settings (43,44). A prospective comparative study also

showed that NaF PET/CT attains a sensitivity of ~95% and a

specificity of ~93%, marginally outperforming SPECT/CT and MRI

(45). Moreover,

18F-DCFPyL PET/CT demonstrated superior diagnostic

accuracy vs. 99mTc-MDP SPECT/CT in a direct head-to-head

study (46). Together, these

findings indicate that PET/CT modalities, especially PSMA-targeted

or choline-based tracers and NaF PET, offer significantly higher

sensitivity and specificity compared with conventional bone

SPECT/CT in prostate cancer bone metastasis detection.

In the present study, preserved cortical bone

integrity was confirmed via histopathological microsectioning,

effectively ruling out local invasion despite the presence of a

superscan pattern. Given this discordance, PSA testing (563.864

ng/ml) and hip CT were pursued, which, combined with SPECT/CT

fusion imaging, identified prostate enlargement and mixed

sclerotic/lytic lesions consistent with metastatic prostate cancer.

The final diagnosis of metachronous MPMN (high-grade MFS and

prostate adenocarcinoma) was thus established. Nonetheless, the

absence of PET/CT imaging and molecular profiling remains a

limitation, and we recommend employing PET/CT or CT bone-window

imaging in similar future cases to enhance diagnostic accuracy and

to better distinguish primary soft-tissue tumors from skeletal

metastases.

In conclusion, the present study describes a rare

case involving dual primary malignancies (subcutaneous MFS and

prostate cancer with extensive bone metastases) diagnosed through

99mTc-MDP three-phase bone scintigraphy. The unique

imaging characteristics, specifically the extensive metastases on

superscan bone imaging and its established association with occult

prostate cancer, together with the patterns of recurrence and

metastasis of the primary tumor, were pivotal in informing and

shaping the subsequent therapeutic approach. Given the scarce

reports of MPMNs identified through 99mTc-MDP

scintigraphy, the present case highlights the need for heightened

clinical vigilance. For patients with recurrent soft-tissue sarcoma

who demonstrate a superscan on bone scintigraphy, routine screening

for occult prostate carcinoma should be undertaken. For any patient

newly diagnosed with a malignancy, clinicians should integrate

detailed clinical evaluation with three-phase bone imaging findings

to eliminate suspicion for additional primary tumors. Such a

strategy enhances diagnostic precision, reduces the likelihood of

missed or incorrect diagnoses and facilitates individualized

treatment planning that may improve overall patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JYL, JLL, HYZ, SXY and JSZ confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. JYL, JLL, HYZ and JSZ contributed to the

conception of the study. JYL, JLL and SXY were responsible for

writing the original draft and reviewing and editing the

manuscript. SXY was responsible for the acquisition of clinical

data. JSZ was responsible for critical revision of the manuscript

and the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study passed ethical review by the Ethics

Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical

University (Guangzhou, China). No information that could

potentially compromise patient privacy or personal identity was

included in this article. All the data used in this study were

collected from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical

University with both written and verbal informed consent from the

patient.

Patient consent for publication

All the test results, images and permission for

their publication were obtained with written consent from the

patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

18F-FDG

|

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

|

|

IARC/IACR

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer/International Association of Cancer Registries

|

|

LHRH

|

luteinizing hormone releasing

hormone

|

|

MFS

|

myxofibrosarcoma

|

|

MMPMN

|

metachronous multiple primary

malignant neoplasm

|

|

MPMN

|

multiple primary malignant

neoplasm

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

PET

|

positron emission tomography

|

|

PSA

|

prostate-specific antigen

|

|

PSMA

|

prostate-specific membrane antigen

|

|

SEER

|

Surveillance Epidemiology and End

Results

|

|

SMPMN

|

synchronous multiple primary malignant

neoplasm

|

|

SPECT

|

single photon emission computed

tomography

|

|

99mTc-MDP

|

99mTc-labeled methylene

diphosphonate

|

References

|

1

|

Warren S and Gates O: Multiple primary

malignant tumors. A survey of the literature and stasistical study.

Am J Cancer. 16:1358–1414. 1932.

|

|

2

|

Liu F, Qin D and Wang Q: Clinical

pathological analysis of 172 cases with multiple primary carcinoma.

Chin J Oncol. 1:113–119. 1979.

|

|

3

|

Moertel CG, Dockerty MB and Baggenstoss

AH: Multiple primary malignant neoplasms. I. Introduction and

presentation of data. Cancer. 14:221–230. 1961. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Shi L, Zhou S, Jiang Y, Wan Y, Ma J, Fu S

and Cheng W: Gynecological malignant tumor related multiple primary

malignant neoplasms: Clinical analysis of 30 cases. Zhonghua Fu

Chan Ke Za Zhi. 49:199–203. 2014.

|

|

5

|

Xu LL and Gu KS: Clinical retrospective

analysis of cases with multiple primary malignant neoplasms. Genet

Mol Res. 13:9271–9284. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang Y, Jiao F, Yao J, Zhou X, Zhang X and

Wang L: Clinical features of multiple primary malignant tumors: A

retrospective clinical analysis of 213 Chinese patients at two

centers. Discov Med. 32:65–78. 2021.

|

|

7

|

Vogt A, Schmid S, Heinimann K, Frick H,

Herrmann C, Cerny T and Omlin A: Multiple primary tumours:

Challenges and approaches, a review. ESMO Open. 2:e0001722017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pauli C, De Boni L, Pauwels JE, Chen Y,

Planas-Paz L, Shaw R, Emerling BM, Grandori C, Hopkins BD and Rubin

MA: A functional precision oncology approach to identify treatment

strategies for myxofibrosarcoma patients. Mol Cancer Res.

20:244–252. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Rachdi I, Daoud F, Khanchel F, Arbaoui I,

Somai M, Zoubeidi H, Aydi Z, Ben Dhaou B, Debbiche A and Boussema

F: Myxofibrosarcoma of the leg: A diagnostic challenge. Clin Case

Rep. 8:3332–3335. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhang P, Ruan SF, Huang J, Gong T and Ji

C: Multiple cutaneous myxofibrosarcoma on the right arm:

Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis. Authorea.

2023.

|

|

11

|

Vanni S, De Vita A, Gurrieri L, Fausti V,

Miserocchi G, Spadazzi C, Liverani C, Cocchi C, Calabrese C,

Bongiovanni A, et al: Myxofibrosarcoma landscape: Diagnostic

pitfalls, clinical management and future perspectives. Ther Adv Med

Oncol. 14:175883592210939732022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Fernebro J, Bladström A, Rydholm A,

Gustafson P, Olsson H, Engellau J and Nilbert M: Increased risk of

malignancies in a population-based study of 818 soft-tissue sarcoma

patients. Br J Cancer. 95:986–990. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Yamamoto S,

Yamaguchi U, Yokoyama R, Kawamoto H, Satake M and Arai Y: Incidence

of multiple primary malignancies in a cohort of adult patients with

soft tissue sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 35:444–452. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sanfilippo R, Miceli R, Grosso F, Fiore M,

Puma E, Pennacchioli E, Barisella M, Sangalli C, Mariani L, Casali

PG and Gronchi A: Myxofibrosarcoma: Prognostic factors and survival

in a series of patients treated at a single institution. Ann Surg

Oncol. 18:720–725. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Mentzel T, Calonje E, Wadden C, Camplejohn

RS, Beham A, Smith MA and Fletcher CD: Myxofibrosarcoma.

Clinicopathologic analysis of 75 cases with emphasis on the

low-grade variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 20:391–405. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Neagu TP, Sinescu RD, Enache V, Achim SC,

Ţigliş M and Mirea LE: Metastatic high-grade myxofibrosarcoma:

Review of a clinical case. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 58:603–609.

2017.

|

|

17

|

Look Hong NJ, Hornicek FJ, Raskin KA, Yoon

SS, Szymonifka J, Yeap B, Chen YL, DeLaney TF, Nielsen GP and

Mullen JT: Prognostic factors and outcomes of patients with

myxofibrosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 20:80–86. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Castaigne C, Martin P and Blocklet D:

Lung, gastric, and soft tissue uptake of Tc-99m MDP and Ga-67

citrate associated with hypercalcemia. Clin Nucl Med. 28:467–471.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Flores LGI, Nagamachi S, Jinnouchi S,

Ohnishi T, Futami S, Nakahara H and Tamura S: Relationship between

extraosseous accumulation in bone scintigraphy with 99Tcm-HMDP and

histopathology. Nucl Med Commun. 19:347–354. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zeng D, Chen Y, Cai L and Zhou F: Analysis

of abnormal uptake of extraskeletal soft tissue in

99mTc-MDP whole bone scan. Chongqing Med J.

45:2073–2077. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

21

|

Ostergaard L, Tietze A, Nielsen T, Drasbek

KR, Mouridsen K, Jespersen SN and Horsman MR: The relationship

between tumor blood flow, angiogenesis, tumor hypoxia, and aerobic

glycolysis. Cancer Res. 73:5618–5624. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Buckley O, O'Keeffe S, Geoghegan T, Lyburn

ID, Munk PL, Worsley D and Torreggiani WC: 99mTc bone scintigraphy

superscans: A review. Nucl Med Commun. 28:521–527. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ren JYL, Li Y and Luo Y: Differentiation

of superscan in 99TCm-MDP bone scintigraphy:

A case report. Chin J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 39:39–40. 2019.(In

Chinese).

|

|

24

|

Askari E, Shakeri S, Roustaei H, Fotouhi

M, Sadeghi R, Harsini S and Vali R: Superscan pattern on bone

scintigraphy: A comprehensive review. Diagnostics (Basel).

14:22292024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kovacsne A, Kozon I, Bentestuen M and

Zacho HD: Frequency of superscan on bone scintigraphy: A systematic

review. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 43:297–304. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Prakash R: Incidental detection of

skeletal metastases on technetium-99m DTPA renal scintigraphy.

Australas Radiol. 39:182–184. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ogura K, Hosoda F, Arai Y, Nakamura H,

Hama N, Totoki Y, Yoshida A, Nagai M, Kato M, Arakawa E, et al:

Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis of myxofibrosarcoma. Nat

Commun. 9:27652018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bui NQ, Przybyl J, Trabucco SE, Frampton

G, Hastie T, van de Rijn M and Ganjoo KN: A clinico-genomic

analysis of soft tissue sarcoma patients reveals CDKN2A deletion as

a biomarker for poor prognosis. Clin Sarcoma Res. 9:122019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kleiburg F, van der Hulle T, Gelderblom H,

Slingerland M, Speetjens FM, Hawinkels LJAC, Dibbets-Schneider P,

van Velden FHP, Pool M, Lam SW, et al: PSMA expression and PSMA

PET/CT imaging in metastatic soft tissue sarcoma patients, results

of a prospective study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 52:3690–3699.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Spiridon IA, Ong SLM, Soukup J,

Topirceanu-Andreoiu OM, de Geus-Oei LF, Gelderblom H, Lam SW, de

Bruijn IHB, Akker BEWMVD, Hijmen L, et al: Neovascular prostate

specific membrane antigen (PSMA) expression in bone and soft tissue

sarcoma: A systematic analysis. Virchows Arch. Apr 9–2025.(Epub

ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Deivaraju C, Temple HT, Block N, Robinson

P and Schally AV: LHRH receptor expression in sarcomas of bone and

soft tissue. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 28:105–111. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wu H, Li J, Yao R, Liu J, Su L and You W:

Focusing on the interplay between tumor-associated macrophages and

tumor microenvironment: from mechanism to intervention.

Theranostics. 15:7378–7408. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhang Z and Wu Y: Research progress on

mechanisms of tumor immune microenvironment and gastrointestinal

resistance to immunotherapy: Mini review. Front Immunol.

16:16415182025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Nair R, Somasundaram V, Kuriakose A,

Krishn SR, Raben D, Salazar R and Nair P: Deciphering T-cell

exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment: Paving the way for

innovative solid tumor therapies. Front Immunol. 16:15482342025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Swaroop VS, Winawer SJ, Kurtz RC and

Lipkin M: Multiple primary malignant tumors. Gastroenterology.

93:779–783. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Liu F, Qin D and Wang Q: Clinical and

pathological analysis of 172 cases of multiple primary cancers.

Chin J Oncol. 1:113–119. 1979.(In Chinese).

|

|

37

|

Adamo M, Johnson C, Ruhl J and Dicki L:

SEER program coding and staging manual. NIH publication number

12-5581. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2012

|

|

38

|

Working Group Report: International rules

for multiple primary cancers (ICD-0 third edition). Eur J Cancer

Prev. 14:307–308. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tichansky DS, Cagir B, Borrazzo E, Topham

A, Palazzo J, Weaver EJ, Lange A and Fry RD: Risk of second cancers

in patients with colorectal carcinoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 45:91–97.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ito K, Masuda-Miyata Y, Wada S, Morooka M,

Yamasawa K, Hashimoto M and Kubota K: F-18 FDG PET/CT imaging of

bulky myxofibrosarcoma in chest wall. Clin Nucl Med. 36:212–213.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Younis MH, Abu-Hijleh HA, Aldahamsheh OO,

Abualruz A and Thalib L: Meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy

of primary bone and soft tissue sarcomas by 18F-FDG-PET. Med Princ

Pract. 29:465–472. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kassem TW, Abdelaziz O and Emad-Eldin S:

Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG-PET/CT for the follow-up and

restaging of soft tissue sarcomas in adults. Diagn Interv Imaging.

98:693–698. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Shen G, Deng H, Hu S and Jia Z: Comparison

of choline-PET/CT, MRI, SPECT, and bone scintigraphy in the

diagnosis of bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer: A

meta-analysis. Skeletal Radiol. 43:1503–1513. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

de Leiris N, Leenhardt J, Boussat B,

Montemagno C, Seiller A, Phan Sy O, Roux J, Laramas M, Verry C,

Iriart C, et al: Does whole-body bone SPECT/CT provide additional

diagnostic information over [18F]-FCH PET/CT for the detection of

bone metastases in the setting of prostate cancer biochemical

recurrence? Cancer Imaging. 20:582020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zamani-Siahkali N, Mirshahvalad SA, Farbod

A, Divband G, Pirich C, Veit-Haibach P, Cook G and Beheshti M:

SPECT/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI for response assessment of bone

metastases. Semin Nucl Med. 54:356–370. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Hu X, Cao Y, Ji B, Zhao M, Wen Q and Chen

B: Comparative study of 18F-DCFPyL PET/CT and

99mTc-MDP SPECT/CT bone imaging for the detection of

bone metastases in prostate cancer. Front Med (Lausanne).

10:12019772023. View Article : Google Scholar

|