Introduction

Breast cancer, a common type of cancer, is

widespread among women (1).

Globally, breast cancer accounts for approximately one-third of all

malignant tumors in women, with its mortality rate representing

~15% of the total diagnosed cases (2). Breast cancer has surpassed lung cancer

in terms of incidence and has become the leading form of cancer

globally, far exceeding other types of cancer in women; the

incidence rate of breast cancer is approximately 2-fold the

combined incidence rate of cervical, ovarian and endometrial cancer

(2). In China, ~429,105 new cancer

cases and 43,780 mortalities due to breast cancer were reported in

2022, with an earlier onset age than that of Western countries, and

the peak incidence was between 45 and 55 years of age (3). Although early detection and increased

awareness of cancer prevention have led to decreased mortality, the

disease's incidence rates rose by 1% each year from 2012 to 2021

(1). Thus, understanding the

nosogenesis of breast cancer and identifying powerful new

biomarkers are necessary for the treatment and prognosis of breast

cancer.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)

belongs to the same family of epidermal growth factor receptors

(4). HER2 activation has been

demonstrated to significantly promote the occurrence of cancer

(5). HER2 is linked to unfavorable

outcomes in human breast cancer, including increased risk of early

recurrence and metastasis (6).

HER2-positive breast cancer is a highly invasive malignant disease

(7). Due to considering HER2 as a

therapeutic target for breast cancer and advances in HER2-targeted

therapy, the prognosis of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer

has been changed, and with improved anti-HER2-targeted therapy,

patient survival time has significantly increased (8,9).

However, an increasing recognition of the frequent occurrence of

tumors with low or heterogeneous HER2 exists (10). Thus, understanding HER2 is of utmost

importance for the treatment of breast cancer.

The present study aimed to screen HER2-related

indicators, build a prognostic risk model to predict breast cancer

prognosis, and identify potential chemotherapeutics for

HER2-positive breast cancer. The current findings provide a

foundation for the treatment and prognosis of HER2-positive breast

cancer.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (http://gdc.cancer.gov) was used to retrieve

TCGA-breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) gene expression and clinical

data. After data pre-processing, 741 TCGA breast cancer samples

were obtained for subsequent analysis. In addition, clinical

information from the GSE7390 dataset was acquired from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). After excluding

specimens with an overall survival (OS) time of 0 days or missing

survival data (due to data unavailability or inability to obtain),

a total of 198 breast cancer samples were included in the

analysis.

Prognosis and clinical feature

analyses

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using

the R package ‘survival’ (Version 3.2-13; http://bioconductor.org/packages/survivalr/)

(11), with statistical comparisons

performed by log-rank test. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was employed

to evaluate the association between different HER2 sample groups

(negative and positive) and OS. In addition, the association

between HER2 and clinical data of breast cancer cases was evaluated

by χ2 or Fisher's exact tests.

Tumor microenvironment (TME)

The Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative

Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT) (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/index.php) (12), Single-sample Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis (ssGSEA) (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ssGSEA.html)

(13) and xCELL (https://github.com/dviraran/xCell) (14) algorithms were adopted to assess the

score of immune cells according to the mRNA expression matrix of

breast cancer samples. The ‘ESTIMATE’ package (http://127.0.0.1:29606/library/estimate/html/estimateScore.html)

(15) in R was employed to obtain

stromal, immune and ESTIMATE fractions. The expression data of

checkpoint genes, human leukocyte antigen family genes and

chemokine genes were extracted from the breast cancer expression

data, and the differences in expression levels between negative-

and positive-HER2 sample groups were compared using the Wilcoxon

rank-sum test.

Mutation analysis

Based on breast cancer sample mutation information,

the mutation status of each gene in the samples was counted, genes

were sorted in descending order by the number of mutations and then

the TOP 20 genes with the highest mutations were selected for

mutation display. Furthermore, the mutation frequency of the top 20

genes was analyzed using the ‘maftools’ package (Version 2.8.0)

(https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/maftools.html)

(16). In addition, the tumor

mutation burden (TMB) of all cancer samples was determined, and the

discrepancy in TMB values between the HER2-negative and -positive

groups was analyzed.

Drug sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity of all cases to chemotherapy agents

was assessed based on data obtained from the Genomics of Drug

Sensitivity in Cancer database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/), and the half maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50) was quantified with the

‘pRRophetic’ package (https://github.com/paulgeeleher/pRRophetic) (17). Differences in the IC50

values of 138 chemotherapeutics between HER2-negative and -positive

groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Immunotherapy response

The Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE)

database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) was used to analyze the

response of patients to immune checkpoint treatment, which was

represented as the TIDE score. In addition, the immunophenoscore

(IPS) was used to determine the scores of the four different immune

phenotypes (namely, inhibitory cells, effector cells, antigen

presentation and checkpoints). Furthermore, the Gene Set Variation

Analysis algorithm was employed to evaluate the tertiary lymphoid

structure (TLS) scores of TLS feature genes [such as CC motif

chemokine ligand (CCL)2, CCL3 and CCL4]. Finally, the differences

in TIDE, IPS and TLS scores between HER2-negative and -positive

groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

GSEA

GSEA (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GSVA.html)

(18) was used to assess the

significant enrichment pathways of hallmark gene sets (h.all.v7.4.

symbols) between HER2-negative and -positive groups with

P<0.05 and |(Normalized Enrichment Score|>1.

Identification of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs)

To identify HER2-specific genes, differential

expression analysis was performed between HER2-positive and

HER2-negative samples using the ‘limma’ package (Version 3.34.7)

(https://

bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html)

(19). This analysis generated

gene-specific P-values, logFC (log2 fold change), and

other relevant metrics. Additionally, the limma package was

employed to perform an empirical Bayes moderated t-test/F-test. The

resulting P-values were sorted and adjusted using the Benjamini and

Hochberg method to obtain false discovery rate (FDR)/q-values,

thereby controlling the overall FDR. DEGs meeting |log2

fold-change|≥0.585 and adj. P<0.05 were used for subsequent

analyses. In addition, enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed

through the ‘clusterProfiler’ package (Version 4.0.5) (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html)

(20) in R, with a threshold of

count >2 and adj. P<0.05.

Construction of a prognostic risk

model

Univariate Cox regression analysis of DEGs was

performed using the Kaplan-Meier ‘survival’ package (http://bioconductor.org/packages/survivalr/) (11) with a critical value of P<0.05 to

identify genes associated with prognosis. The least absolute

shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) is a

dimensionality-reduction method that has shown advantages over

regression analysis in evaluating high-dimensional data. LASSO is

an improvement of linear regression that achieves feature selection

and complexity control by adding a penalty term. For parameter

optimization, LASSO provides two criteria: i) ‘min’ selects the

model achieving minimum cross-validation error within allowable

variance; and ii) ‘1se’ (one standard error rule) chooses the most

parsimonious model whose performance is statistically

indistinguishable from the ‘min’ model, effectively balancing

accuracy and simplicity. This algorithm can determine the optimal

penalty coefficient based on the minimum likelihood deviation and

10-fold cross validation (21).

Therefore, LASSO (21) was used to

identify key genes. The risk score was constructed using stepwise

Cox regression analysis with the survminer package in R (Version

0.4.9) (https://cran.rstudio.com/web/packages/survminer/index.html).

The formula is as follows: RiskScore=h (t,X)=h0 (t) ×

exp (β1X1 + β2X2 + ...

+ βnXn), where β indicates the regression

coefficient; h0(t), the benchmark risk function; and h

(t,X) the risk role related to X (covariate) at time t. All

specimens were classified into high- and low-risk groups according

to the median RiskScores. Survival analysis was performed using the

Kaplan-Meier curve method with the log-rank test for statistical

comparison between groups. To evaluate the diagnostic performance

of feature genes, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

and the area under the curve (AUC) were plotted across all

datasets, including both training and validation sets.

Nomogram construction

The association between RiskScores and

clinicopathological data (such as age and stage) was investigated,

and univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were

performed to screen for useful prognostic features, with a

threshold of P<0.05. Next, the ‘rms’ package (Version 6.2-0)

(https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html)

(22) was further utilized to

construct a nomogram.

Association analysis of RiskScore and

immunity

The ‘ssGSEA’ and ‘CIBERSORT’ algorithms were

employed to evaluate the proportional distribution of immune cells

between different risk groups. Spearman correlation analysis was

performed using the ‘ggcor’ package (Version 0.9.8.1) (https://pan.baidu.com/s/1S6w93IjfO6sU8IHGvvCa1w)

(23) to assess the association

between RiskScore and immune cell infiltration.

Characteristics of key genes

The associations between the expression levels of

key genes were determined with the ‘ggplot2’ package (Version

3.3.5) (https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2) (24), while the ‘RCircos’ package (Version

1.2.2) (https://github.com/hzhanghenry/RCircos) (25) was employed to draw the mutation gene

plot of key genes. The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to assess the

survival of patients. The log-rank test was employed to determine

the statistical significance of differences between survival curves

with a P-value threshold of <0.05.

Single-cell analysis

Based on a single-cell RNA sequencing database

focused on the TME accessed through the Tumor Immune Single-cell

Hub (TISCH) database (http://tisch.comp-genomics.org), scRNA-seq data from

GSE161529 (26) were analyzed.

Detailed cell type annotation was performed at the single-cell

level for subsequent analysis of specific gene expression across

distinct cell populations (27).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Six HER2-negative and six HER2-positive breast

cancer samples were collected from May 1, 2023, to December 31,

2023, at Weifang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Weifang,

China). The enrolled patients ranged in age from 32 to 69 years,

and all samples were obtained through surgical resection. The

Ethics Committee of Weifang Hospital of Traditional Chinese

Medicine approved the present study (approval no. WF2023-428). All

the participants provided written informed consent.

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was extracted from tissue

samples using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Inc. cat. no. 74104) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. According to the manufacturer's

instructions, the RNA samples were reverse transcribed into cDNA

using an QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (cat. no. 205311;

Qiagen GmbH), and qPCR was performed using a CFX96 Bio-Rad system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with SYBR Green I fluorophore (cat.

no. 1708882; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec, with

a final melting curve analysis from 65°C to 95°C in 0.5°C

increments. The primer sequences, which were designed and

synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., are listed in Table I. The internal reference gene for

normalization was GAPDH. Each sample was analyzed in three

technical replicates, and the relative levels of key genes were

analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCq method (28).

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| ETFA (F) |

ACAAAGGCACTCTAGCCACC |

| ETFA (R) |

GTCCAAGAGTGTCACCAGGG |

| RAPGEFL1 (F) |

AGGGGCTGCTTCAAGAGGA |

| RAPGEFL1 (R) |

CCCTGGTAAAGGGACTCGT |

| KRT7 (F) |

CGGTGAGGACAAGGAACCTG |

| KRT7 (R) |

CCTTGGAGCAGGAATCAGCA |

| CD24 (F) |

TTCTCCAAGCACCCAGCA |

| CD24 (R) |

TGGAATAAATCTGCGTGGGTA |

| PRR15L (F) |

GACTTTAACACCCGCCTGGA |

| PRR15L (R) |

TGAAGCGTCCTGAGTTGGAG |

| ALOX15B (F) |

CCACCCTCTCTTCAAGTCCAC |

| ALOX15B (R) |

CTTGGAGAAGATCTCTCTGACCC |

| ELOVL2 (F) |

AAGCTGACATCCGGGTAG |

| ELOVL2 (R) |

TGTCCACAAGGTATCCAGTT |

| CXCL9 (F) |

GGCTTTGGAAGCCATGTGAT |

| CXCL9 (R) |

GAAGAGCTGACTTGAATGAAGCAA |

| GAPDH (F) |

GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG |

| GAPDH (R) |

ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA |

Cell culture and transfection

The HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines BT474

(cat. no. TCHu143) and SKBR-3 (cat. no. TCHu225) (29), and the HER2-negative breast cancer

cell line MDA-MB-468 (cat. no. TCHu136) (30) were purchased from The Cell Bank of

Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences. All

cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (cat. no. 11875093; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; cat. no. 10099141; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in

an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells at logarithmic

proliferation stage were transfected. The ELOVL2 overexpression

plasmid (OE-ELOVL2) and its negative control (NC-ELOVL2) were

constructed using the pCMV6-AC-GFP vector backbone (cat. no.

YC-13849RJ) by Shanghai Yaji Biotechnology Co., Ltd., and then

transfected into cells using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (cat.

no. 11668019; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at a

concentration of 2 µg per 1×106 cells. After 6 h of

transfection, the complete medium was replaced and the cells were

further cultured for 48 h. The transfected cells were then

collected for subsequent experiments.

Cell Counting Kit (CCK-8) cytotoxicity

assay

BT474 and SKBR-3 cells were inoculated into 96-well

plates with 1×104 cells per well in a ~100 µl

suspension, and cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37ºC

in triplicate wells. After the cells reached 80–90% confluence (as

observed by phase-contrast microscopy), CCK-8 reagent (cat. no.

CK04; Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) was added, and incubated at 37°C

for 2 h. Next, the absorption value at 450 nm was measured using a

microplate reader (ELx800; BioTek Instruments; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.), and the cytotoxicity curves of the cells at

different times were plotted. The experiment was repeated three

times independently.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (cat. no. P0013B;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF to

extract the total proteins from each group. SDS-PAGE was performed

with 30 µg protein loaded per lane on 10% polyacrylamide gels after

determining the protein concentration in each group using a BCA kit

(cat. no. 23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After

electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a PVDF

membrane, which was then blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin

(MilliporeSigma) for 1 h at 37°C. Next, primary antibodies against

PI3K (p110 alpha) (1:1,000; cat. no. 4255; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), phosphorylated (p)-PI3K recognizing p85

(Tyr458)/p55 (Tyr199) (E3U1H) (1:1,000; cat. no. 17366; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), AKT (pan) (11E7) (1:1,000; cat. no.

4685; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), p-AKT (Ser473) (D9E)

XP® (1:1,000; cat. no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.) and GAPDH (used as a loading control for normalization)

(1:10,000; cat. no. 2118; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were

added and incubated at 4°C overnight. After that, the membranes

were washed thoroughly to remove unbound primary antibodies,

followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody

[Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H+L) (peroxidase/HRP conjugated); 1:10,000,

cat. no. E-AB-1003; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; and

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (peroxidase/HRP conjugated); 1:10,000;

cat. no. E-AB-1001; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.] at

room temperature for 1 h. Next, a laser imager (Typhoon FLA 9500;

GE Healthcare) was used for scanning with ECL Plus Western Blotting

Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the gray values

were analyzed after normalization to GAPDH as a loading

control.

Statistical analysis

R software (SPSS 22.0) and GraphPad software

(version 7.0; GraphPad; Dotmatics) were used for data processing,

statistical analyses and plotting. Survival curves were constructed

using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was employed

to compare survival differences between groups, provided the

proportional hazards assumption held. For time-to-event data with

intermediate events, the two-stage survival analysis method from

the Two Stage Hazard Rate Comparison package (Version 0.1-6) was

applied when the proportional hazards assumption was violated.

One-way analysis of variance was performed to assess overall

differences, followed by pairwise comparisons between groups using

Tukey's honestly significant difference test. In Table II, continuous variables with normal

distribution are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, with

intergroup comparisons assessed using unpaired Student's t-test;

while skewed data are reported as median (interquartile range) and

were compared via Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis H test

followed by Dunn's multiple comparison post hoc test. Categorical

variables are expressed as counts and percentages, with comparisons

analyzed using χ2 or Fisher's exact tests. Unpaired All

statistical tests were two-sided and P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

| Table II.Association between clinical

characteristics and HER2 expression. |

Table II.

Association between clinical

characteristics and HER2 expression.

|

Characteristics | Negative | Positive | Total | P-value |

|---|

| ER status, n

(%) |

|

|

|

6.00×10−3 |

|

Indeterminate | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.28) | 2 (0.28) |

|

|

Negative | 138 (19.27) | 31 (4.33) | 169 (23.60) |

|

|

Positive | 471 (65.78) | 74 (10.34) | 545 (76.12) |

|

| PR status, n

(%) |

|

|

|

4.00×10−3 |

|

Indeterminate | 4 (0.56) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.56) |

|

|

Negative | 181 (25.31) | 49 (6.85) | 230 (32.17) |

|

|

Positive | 423 (59.16) | 58 (8.11) | 481 (67.27) |

|

| Age, years |

|

|

| 0.71 |

| Mean ±

SD | 57.83±13.15 | 58.37±13.21 | 57.91±13.15 |

|

| Median

(range) | 58.00

(26.00-90.00) | 58.00

(27.00-90.00) | 58.00

(26.00-90.00) |

|

| M stage, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.62 |

| M0 | 620 (83.78) | 107 (14.46) | 727 (98.24) |

|

| M1 | 12 (1.62) | 1 (0.14) | 13 (1.76) |

|

| N stage, n (%) |

|

|

|

3.00×10−3 |

| N0 | 329 (44.16) | 37 (4.97) | 366 (49.13) |

|

| N1 | 195 (26.17) | 50 (6.71) | 245 (32.89) |

|

| N2 | 80 (10.74) | 14 (1.88) | 94 (12.62) |

|

| N3 | 32 (4.30) | 8 (1.07) | 40 (5.37) |

|

| T stage, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.11 |

| T1 | 180 (24.26) | 19 (2.56) | 199 (26.82) |

|

| T2 | 368 (49.60) | 74 (9.97) | 442 (59.57) |

|

| T3 | 63 (8.49) | 10 (1.35) | 73 (9.84) |

|

| T4 | 22 (2.96) | 6 (0.81) | 28 (3.77) |

|

| AJCC stage, n

(%) |

|

|

|

2.00×10−3 |

| I | 124 (17.06) | 6 (0.82) | 130 (17.88) |

|

| II | 348 (47.87) | 71 (9.77) | 419 (57.63) |

|

|

III | 135 (18.57) | 29 (3.99) | 164 (22.56) |

|

| IV | 13 (1.79) | 1 (0.14) | 14 (1.93) |

|

| DFS time,

months |

|

|

| 0.40 |

| Mean ±

SD | 41.07±39.64 | 37.74±31.88 | 40.56±38.55 |

|

| Median

(range) | 28.50

(0.16-281.29) | 23.34

(0.03-139.17) | 28.44

(0.03-281.29) |

|

| DFS status, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.34 |

|

Disease-free | 504 (77.18) | 93 (14.24) | 597 (91.42) |

|

|

Recurred/Progressed | 49 (7.50) | 7 (1.07) | 56 (8.58) |

|

| DSS tim,

months |

|

|

| 0.21 |

| Mean ±

SD | 43.78±41.74 | 39.16±35.24 | 43.10±40.87 |

|

| Median

(range) | 31.36

(0.16-282.90) | 24.79

(0.03-212.25) | 31.00

(0.03-282.90) |

|

| DSS status, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.44 |

|

Alive | 572 (78.25) | 102 (13.95) | 674 (92.20) |

|

|

Deceased | 52 (7.11) | 5 (0.68) | 57 (7.80) |

|

| MSIsensor

score |

|

|

| 0.75 |

| Mean ±

SD | 0.65±2.01 | 0.44±0.61 | 0.62±1.87 |

|

| Median

(range) | 0.26

(0.00-32.92) | 0.28

(0.00-4.09) | 0.26

(0.00-32.92) |

|

| Mutation count,

n |

|

|

|

3.00×10−6 |

| Mean ±

SD | 81.15±271.60 | 116.03±413.31 | 86.26±296.53 |

|

| Median

(range) | 37.00

(2.00-5,400.00) | 53.00

(17.00-4,259.00) | 40.00

(2.00-5,400.00) |

|

| OS time,

months |

|

|

| 0.21 |

| Mean ±

SD | 43.77±41.71 | 39.16±35.24 | 43.10±40.84 |

|

| Median

(range) | 31.54

(0.16-282.90) | 24.79

(0.03-212.25) | 31.00

(0.03-282.90) |

|

| OS status, n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.88 |

|

Alive | 547 (73.42) | 95 (12.75) | 642 (86.17) |

|

|

Deceased | 89 (11.95) | 14 (1.88) | 103 (13.83) |

|

| PFS time,

months |

|

|

| 0.20 |

| Mean ±

SD | 40.93±38.60 | 36.66±31.51 | 40.30±37.66 |

|

| Median

(range) | 28.77

(0.16-281.29) | 21.83

(0.03-139.17) | 28.44

(0.03-281.29) |

|

| PFS status n

(%) |

|

|

| 0.45 |

|

Censored | 546 (73.39) | 98 (13.17) | 644 (86.56) |

|

|

Progression | 89 (11.96) | 11 (1.48) | 100 (13.44) |

|

| TMB, n |

|

|

|

3.10×10−5 |

| Mean ±

SD | 2.75±9.02 | 3.94±13.76 | 2.92±9.86 |

|

| Median

(range) | 1.30

(0.00-180.83) | 1.77

(0.00-142.67) | 1.40

(0.00-180.83) |

|

Results

Prognosis and analysis of clinical

features

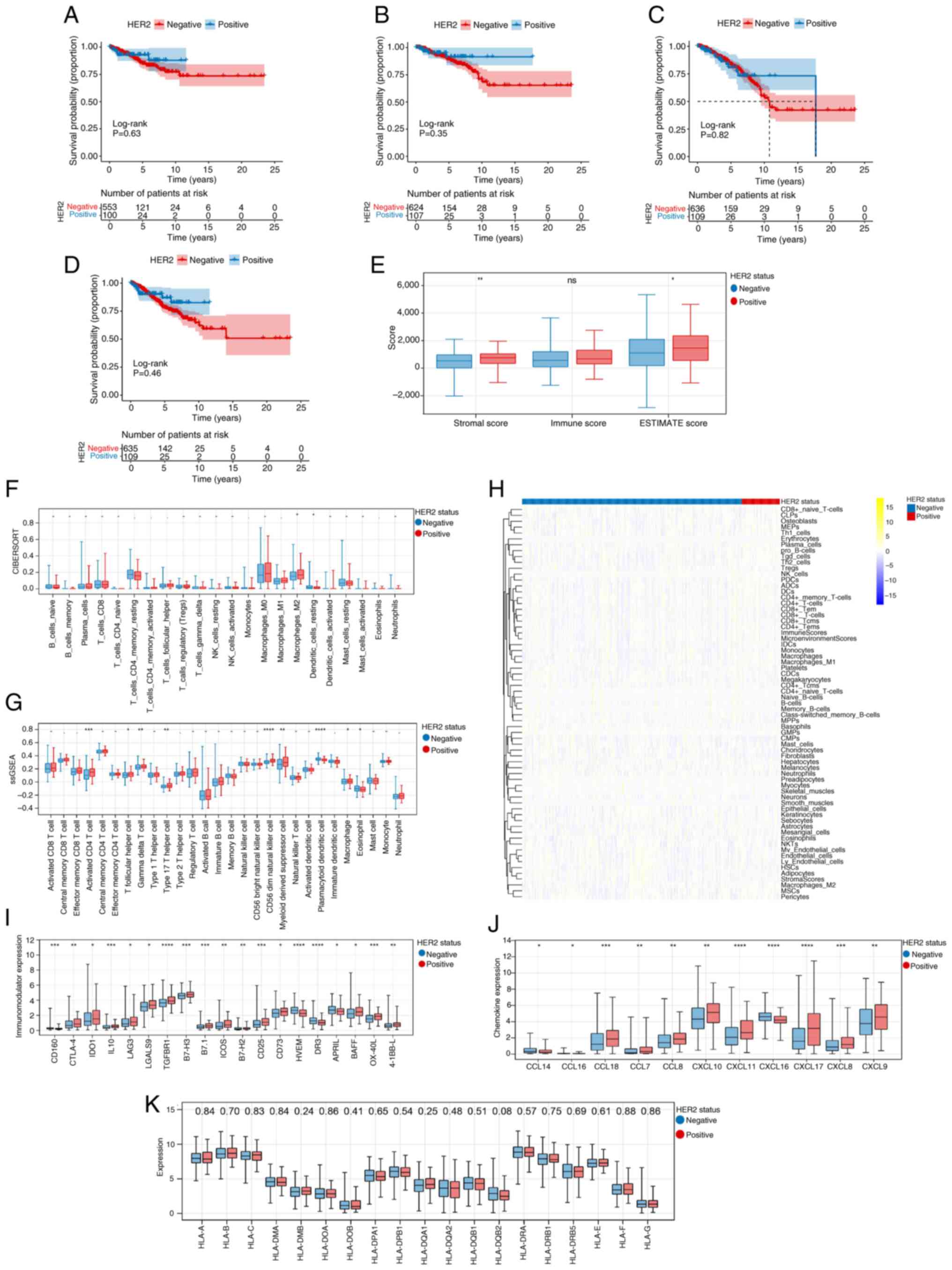

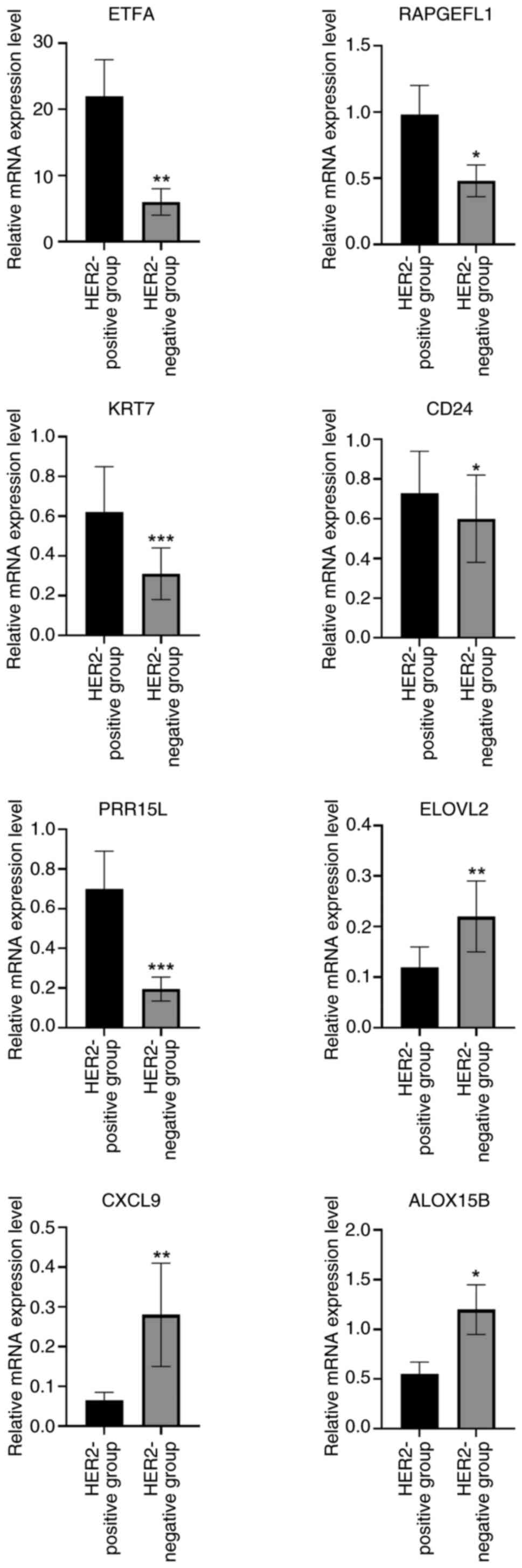

As shown in Fig.

1A-D, no statistically significant differences were observed in

prognosis between HER2-negative and -positive groups. Analysis of

the association between clinical traits and HER2 suggested that

HER2 was significantly associated with ER status, PR status, N

stage, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, mutation

count and TMB (Table II).

| Figure 1.Prognosis, clinical features and

tumor microenvironment analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves of (A)

disease-free survival, (B) disease-specific survival, (C) overall

survival and (D) progression-free survival in HER2-negative and

positive groups. Note: Survival curves were constructed using the

Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was employed to compare

survival differences between groups, provided the proportional

hazards assumption held. The two-stage survival analysis method

from the two-stage Hazard Rate Comparison package was applied when

this assumption was violated. (E) Differences in stromal, immune

and ESTIMATE scores between HER2-negative and positive groups. The

(F) ‘CIBERSORT’, (G) ‘Single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(ssGSEA)’ and (H) ‘xCELL’ algorithms revealed the fraction of

immune cells in the HER2-negative and -positive groups. The numbers

displayed in the yellow/blue legend represent the standardized

expression levels (Z-scores). Differences in (I) Immunomodulator

expression levels, (J) chemokine genes and (K) HLA family genes

between HER2-negative and -positive groups. The numerical values

displayed at the top of the panel refer to P-values. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. ns, -, and . indicate

no significant difference; HER2, human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2; CIBERSORT, Cell-type Identification By Estimating

Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts; ssGSEA, single-sample Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis; NK, natural killer; T helper; HLA, human

leukocyte antigen; CCL, Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CXCL,

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; CLP, common lymphoid progenitors;

MEP, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors; Th, T helper cells; Tgd,

Tgd-like cells; iDC, immature dendritic cells; cDC, conventional

dendritic cells; MPP, multipotent progenitors; GMP,

granulocyte-macrophage progenitors; CMP, common myeloid

progenitors; NKT, natural killer T-cells; mv, mv-like cells; HSC,

hematopoietic stem cells; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells; Tregs,

regulatory T cells. |

TME

Fig. 1E shows that

the Stromal and ESTIMATE scores in HER2-positive group were higher

than those in the HER2-negative group. Moreover, the ‘CIBERSORT’

algorithm revealed that the fraction of M2 macrophages and resting

dendritic cells showed significant differences between the

different HER2 groups (Fig. 1F).

Additionally, the ‘ssGSEA’ and ‘xCELL’ algorithms revealed that

there were 9 types (Activated CD4 T cell, T follicular helper cell,

Gamma delta T cell, Type 17 T helper cell, CD56 bright natural

killer cell, Myeloid derived suppressor cell, Plasmacytoid

dendritic cell, Macrophage and Eosinophil) and 20 types of immune

cells, respectively, which showed marked differences between

different HER2 groups (Fig. 1G and

H, respectively). The present study also identified 19 immune

regulatory genes (Fig. 1I) and 11

chemokine genes (Fig. 1J) that

exhibited remarkable differences between the HER2-negative and

-positive groups. Fig. 1K

demonstrates the differential expression of HLA family genes across

distinct HER2 status groups.

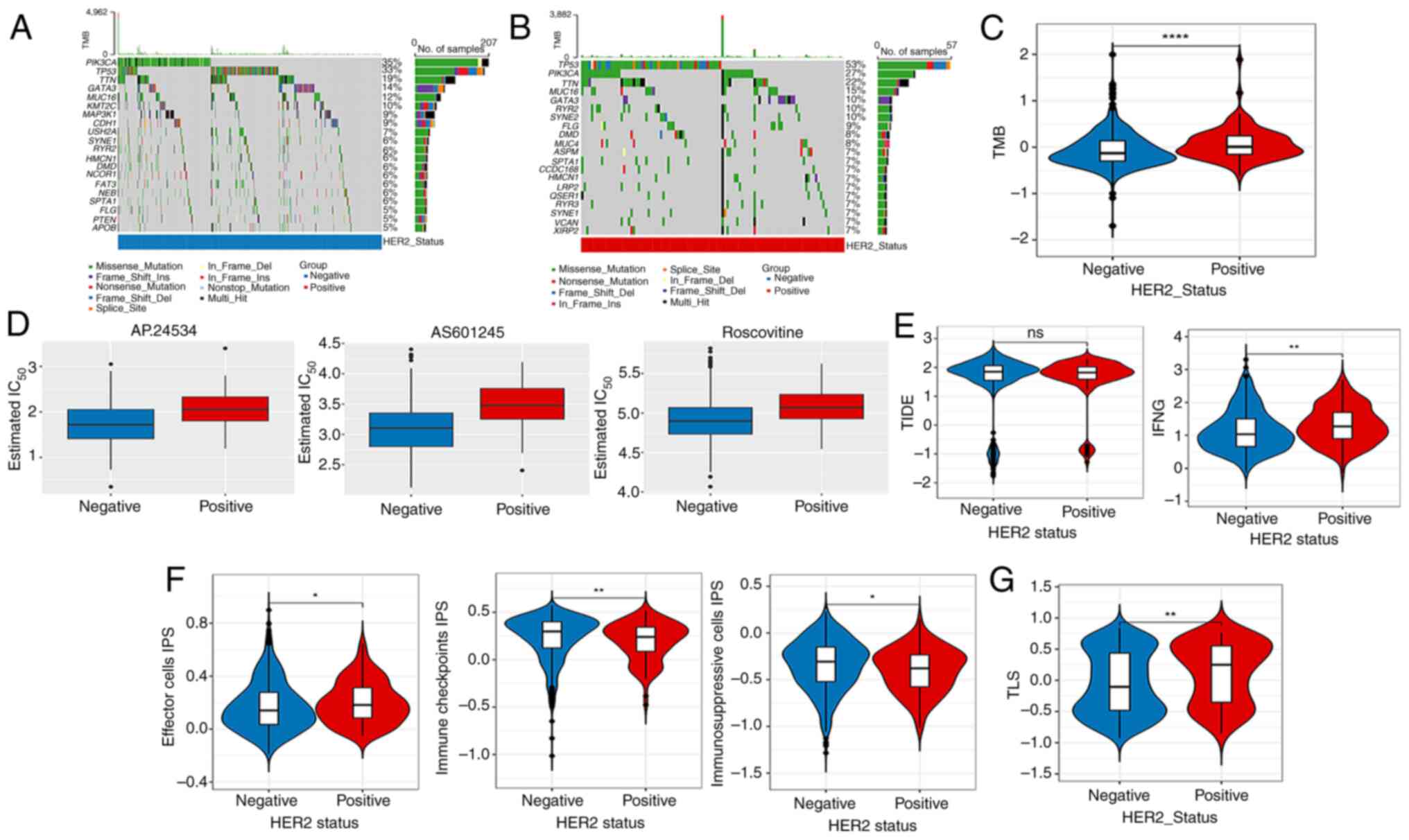

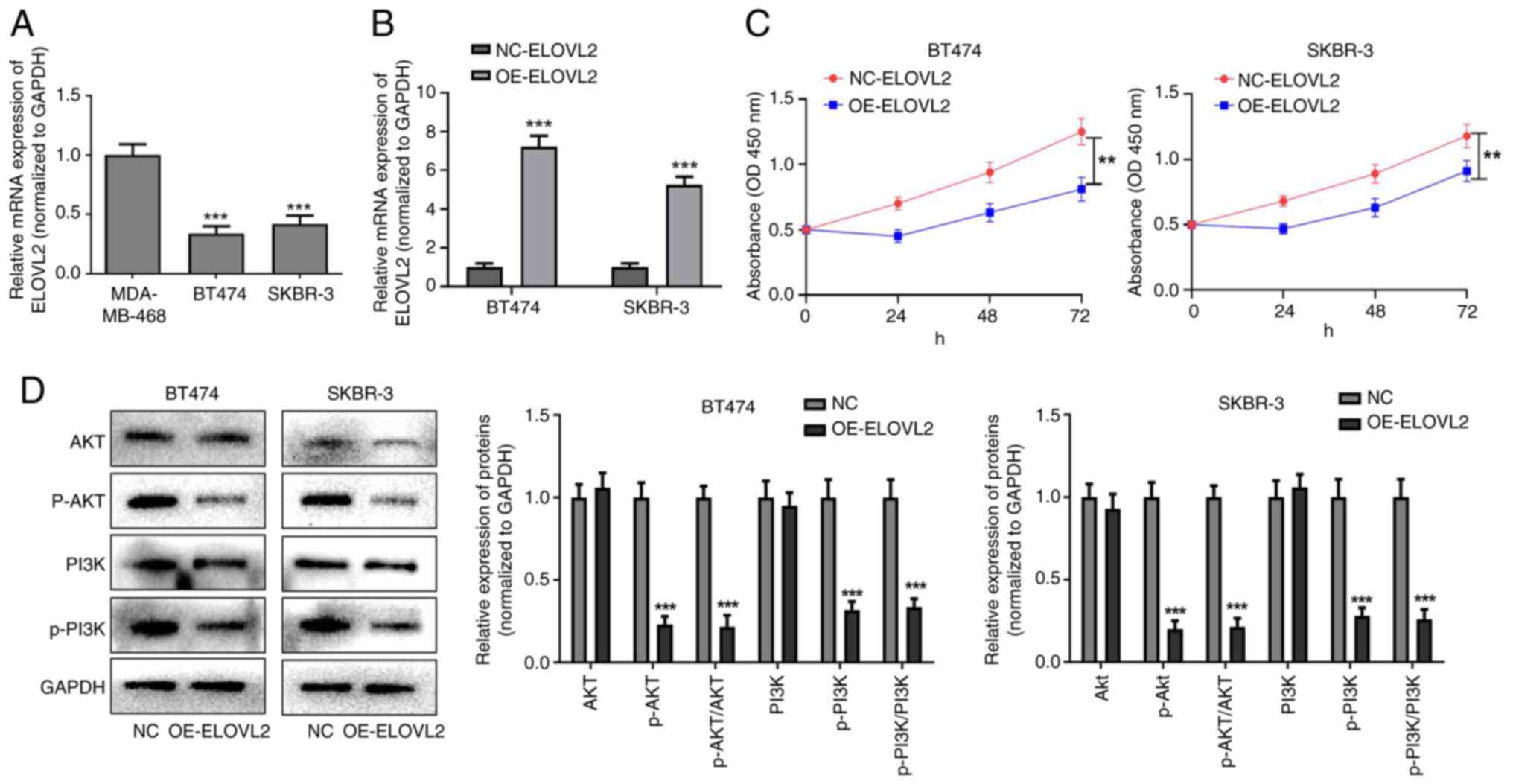

Mutation analysis, immunotherapy

response and drug sensitivity analysis

Based on the TCGA-derived mutational profiles,

gene-specific mutation frequencies across breast cancer cohorts

were systematically analyzed. Fig. 2A

and B illustrates the hierarchical distribution of the top 20

most frequently mutated genes, with Fig. 2A and B demonstrating distinct

mutational landscapes between HER2-negative and HER2-positive

subtypes, respectively. Mutation analysis showed that, compared

with those of the HER2-negative group, the TMB values of the top 20

genes in the HER2-positive group were higher (Fig. 2C). Fig.

2D shows the top three chemotherapeutic drugs with significant

differences between the two groups. In addition, no significant

difference was observed in the TIDE score among the HER2-positive

and -negative groups, whereas the interferon γ score in the

HER2-positive group was higher than that in the HER2-negative group

(Fig. 2E). The data showed

remarkable discrepancies in the effector cell, immunosuppressive

cells and immune checkpoint IPS scores among the different HER2

groups (Fig. 2F). In addition, the

TLS scores showed remarkable differences among the HER2-positive

and -negative groups (Fig. 2G).

| Figure 2.Mutation analysis, drug sensitivity

analysis and immunotherapy response. Top 20 mutation genes in (A)

HER2-negative and (B) -positive samples. (C) Differences in TMB

values between the HER2-negative and -positive groups. (D) Top 3

chemotherapeutics with notable differences in their IC50

between the HER2-negative and -positive groups. Differences in (E)

TIDE, IFNG, (F) IPS, (G) TLS scores between HER2-negative and

-positive groups. ns, no obvious difference, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. ns, no significant difference; TMB,

tumor mutation burden; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor

2; Ins, insertion; Del, deletion; IC50, half maximal

inhibitory concentration; TIDE, Tumor Immune Dysfunction and

Exclusion; IFNG, interferon γ; IPS, immunophenoscore; TLS, tertiary

lymphoid structure. |

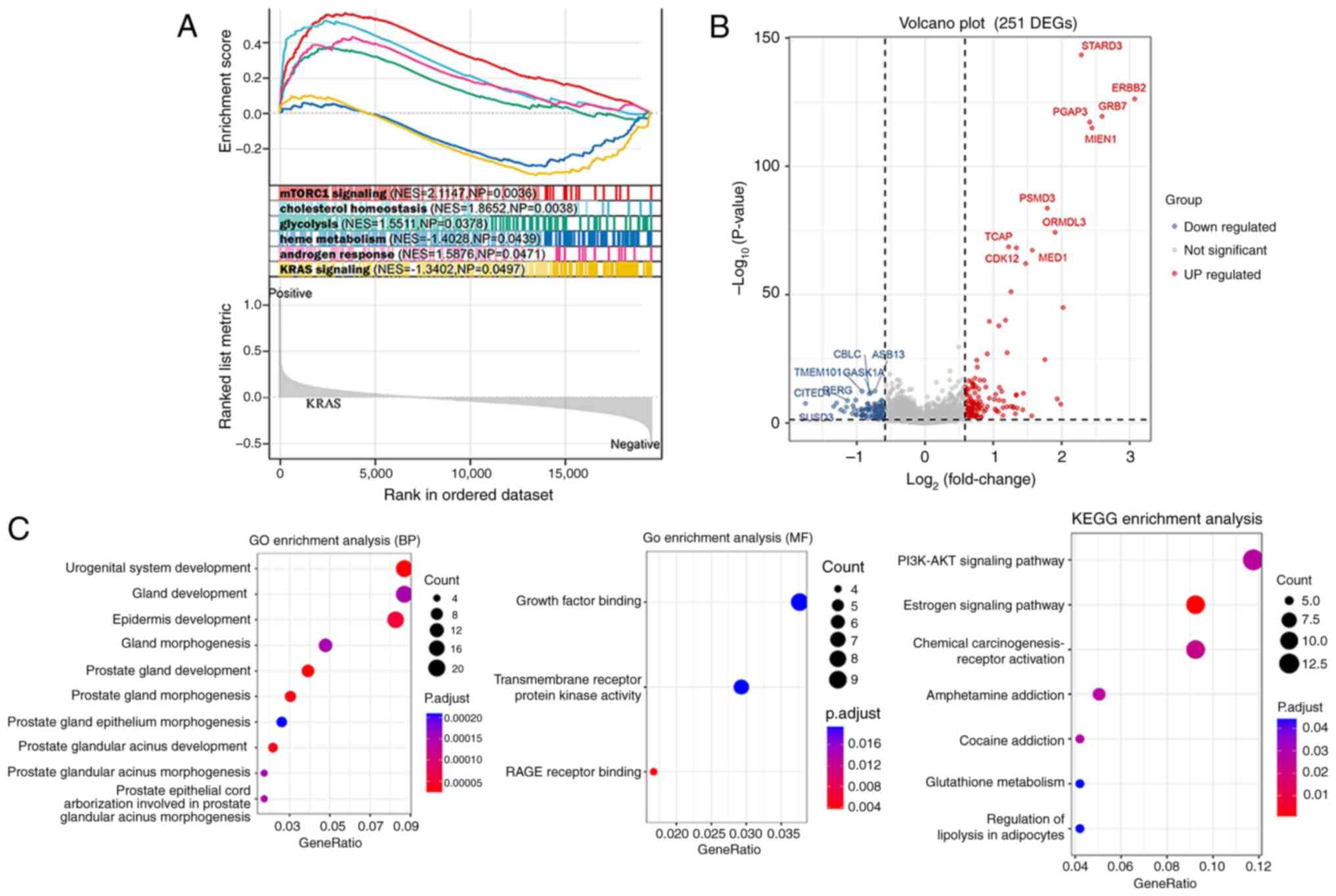

Enrichment analysis

GSEA identified six pathways of hallmark gene sets

between different HER2 groups, namely, mTORC1 signaling,

cholesterol homeostasis, glycolysis, heme metabolism, androgen

response and KRAS signaling (Fig.

3A). A total of 251 DEGs between different HER2 groups were

screened (Fig. 3B), and these DEGs

were enriched in the GO terms of urogenital system development and

RAGE receptor binding, and were involved in the following KEGG

pathways: Estrogen signaling pathway, chemical

carcinogenesis-receptor activation and PI3K-AKT signaling pathway

(Fig. 3C).

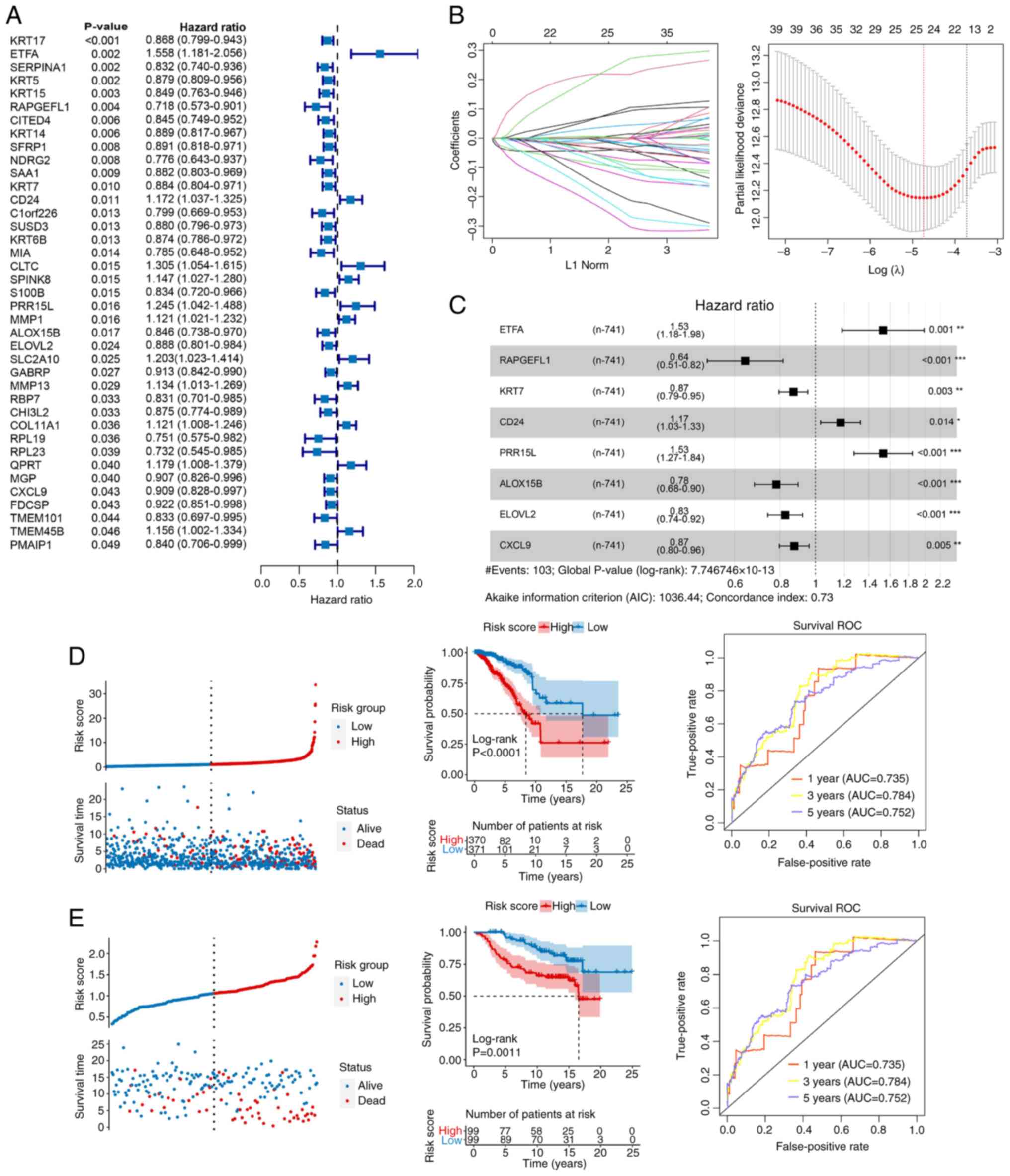

Construction and validation of a

prognostic risk model

A total of 39 prognostic related genes were screened

from the 251 DEGs (Fig. 4A).

Subsequently, LASSO regression analysis was performed using

univariate Cox regression with a P-value threshold of <0.05,

which narrowed down the candidates to 25 genes (Fig. 4B). Moreover, eight key genes were

identified after stepwise Cox regression analysis (Fig. 4C): ETFA, RAPGEFL1, KRT7, CD24,

PRR15L, ALOX15B, ELOVL2 and CXCL9. A risk model was constructed

based on the aforementioned key genes. As shown in Fig. 4D and E, compared with the low-risk

group, patients in the high-risk group had a notably poorer

prognosis (P<0.01), and AUC of the ROC curve was 0.735, 0.784

and 0.752 for the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival, respectively, in TCGA

dataset (Fig. 4D), vs. 0.787, 0.796

and 0.771, respectively, in the GSE7390 dataset (Fig. 4E).

Nomogram

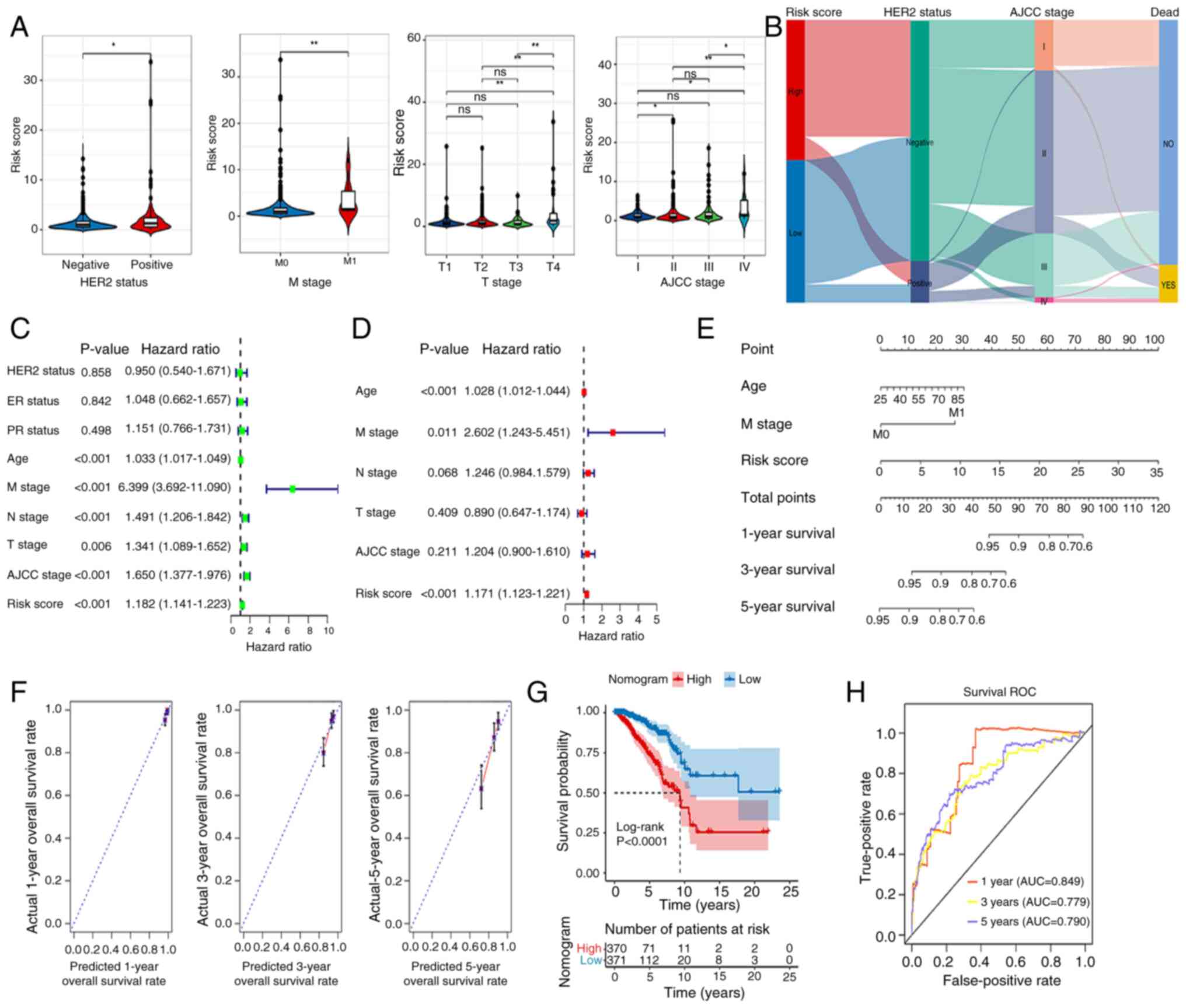

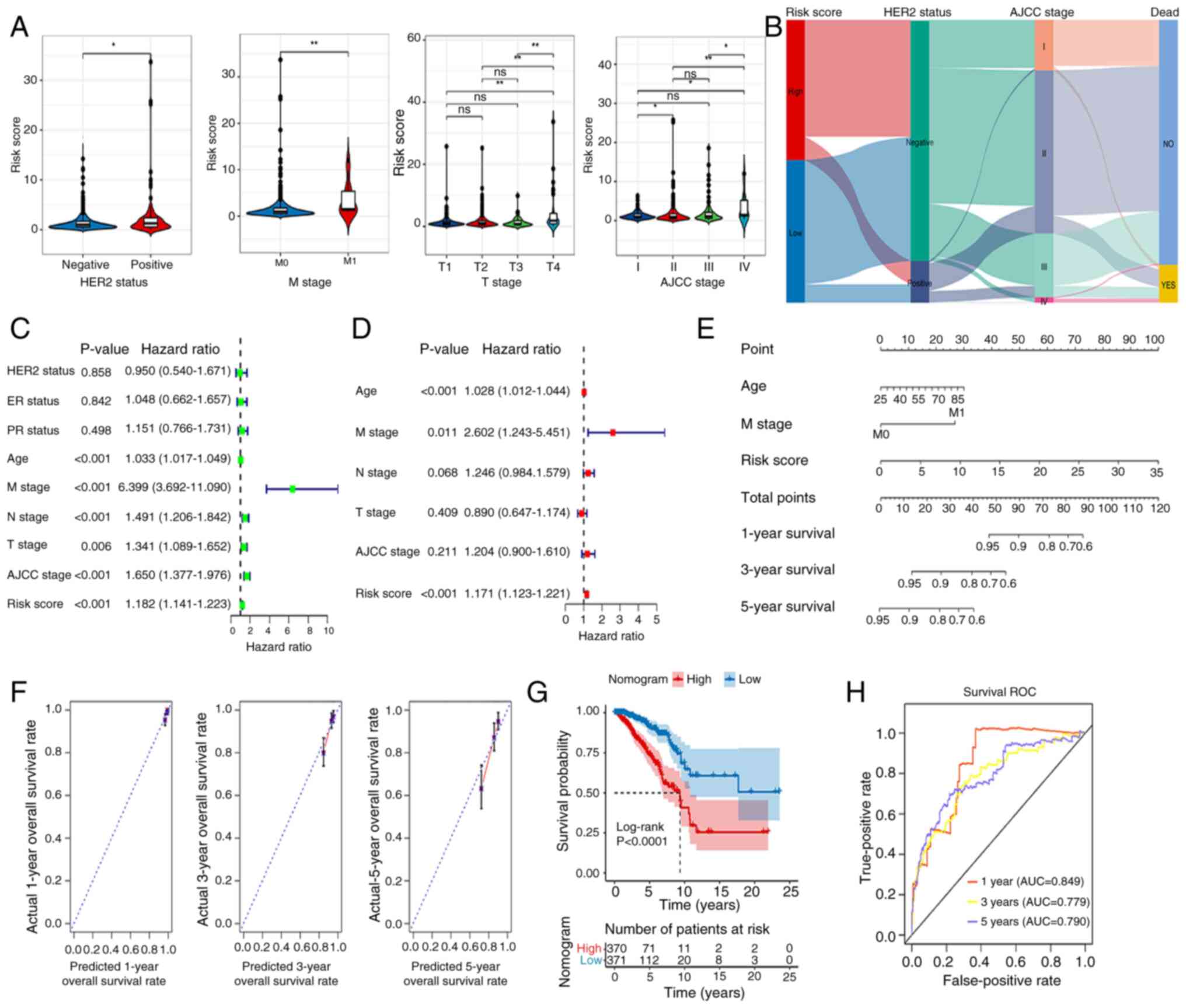

Fig. 5A shows marked

differences in Risk score between different HER2 groups (positive

vs. negative), M stage (M0 vs. M1), T stage (T1 vs. T4, T2 vs. T4,

T3 vs. T4) and AJCC stage (I vs. II, I vs. IV, II vs. IV, III vs.

IV). Fig. 5B demonstrates that the

high-risk group exhibits a significant tendency toward

HER2-negative cases, whereas the low-risk group shows a higher

proportion of HER2-positive cases. The HER2 status indirectly

influences survival outcomes by affecting AJCC staging.

HER2-negative cases are more likely to be classified as early-stage

(I/II), associated with higher survival rates, while HER2-positive

tumors tend to progress to advanced stages (III/IV), linked to

elevated mortality risks. AJCC stage is strongly associated with

survival outcomes: stages I, II, and III primarily exhibit NO

(survival), whereas stage IV predominantly presents YES (death).

Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed on clinical

factors and risk score of the samples. Factors with P<0.05 were

selected for subsequent multivariate Cox regression analysis to

identify significant independent prognostic factors. Age, risk

score and M stage were considered as independent prognostic factors

(Fig. 5C and D). These factors were

then used to build a nomogram, demonstrating that each variable

independently contributed to survival probability prediction.

Increased age corresponded with lower survival rates, advanced M

stage significantly reduced survival probability, and higher risk

scores were associated with poorer prognoses. Total points provided

an intuitive prediction of outcomes, such as the 5-year survival

rate. Model validation revealed high discriminatory ability

(C-index=0.748) (Fig. 5E). The

survival rate model predicted by the nomogram shows overall

consistency with the actual survival rates for 1-, 3- and 5-year

predictions. Specifically, the 1-year survival rate predictions are

closely clustered around the ideal dashed line, indicating better

consistency. The 3-year survival rate data points are more

dispersed but still remain around the dashed line, demonstrating

good consistency. However, the 5-year survival rate data points

exhibit increased dispersion, with some deviating from the dashed

line, leading to a decline in consistency. Overall, the consistency

decreases as the predicted time span increases (Fig. 5F). Fig.

5G shows the marked association of these factors with patient

outcomes. The ROC for the nomogram suggested that the AUCs at 1, 3

and 5 years were 0.849, 0.779 and 0.790, respectively (Fig. 5H).

| Figure 5.Construction of a nomogram. (A)

Differences in RiskScore between different HER2-status groups and

clinical features. (B) Association between HER2 and RiskScores. (C)

Univariate and (D) multivariate analyses of clinical data and risk

group. (E) Nomogram for predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year overall

survival. (F) Calibration curve analysis of nomogram. (G)

Kaplan-Meier analysis of the nomogram. (H) AUCs for predicting 1-,

3- and 5-year OS. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. ns, no significant

difference; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ER,

estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; M, metastasis; N,

node; T, tumor; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; OS,

overall survival; AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver

operating characteristic. |

Association analysis of immunity and

RiskScore

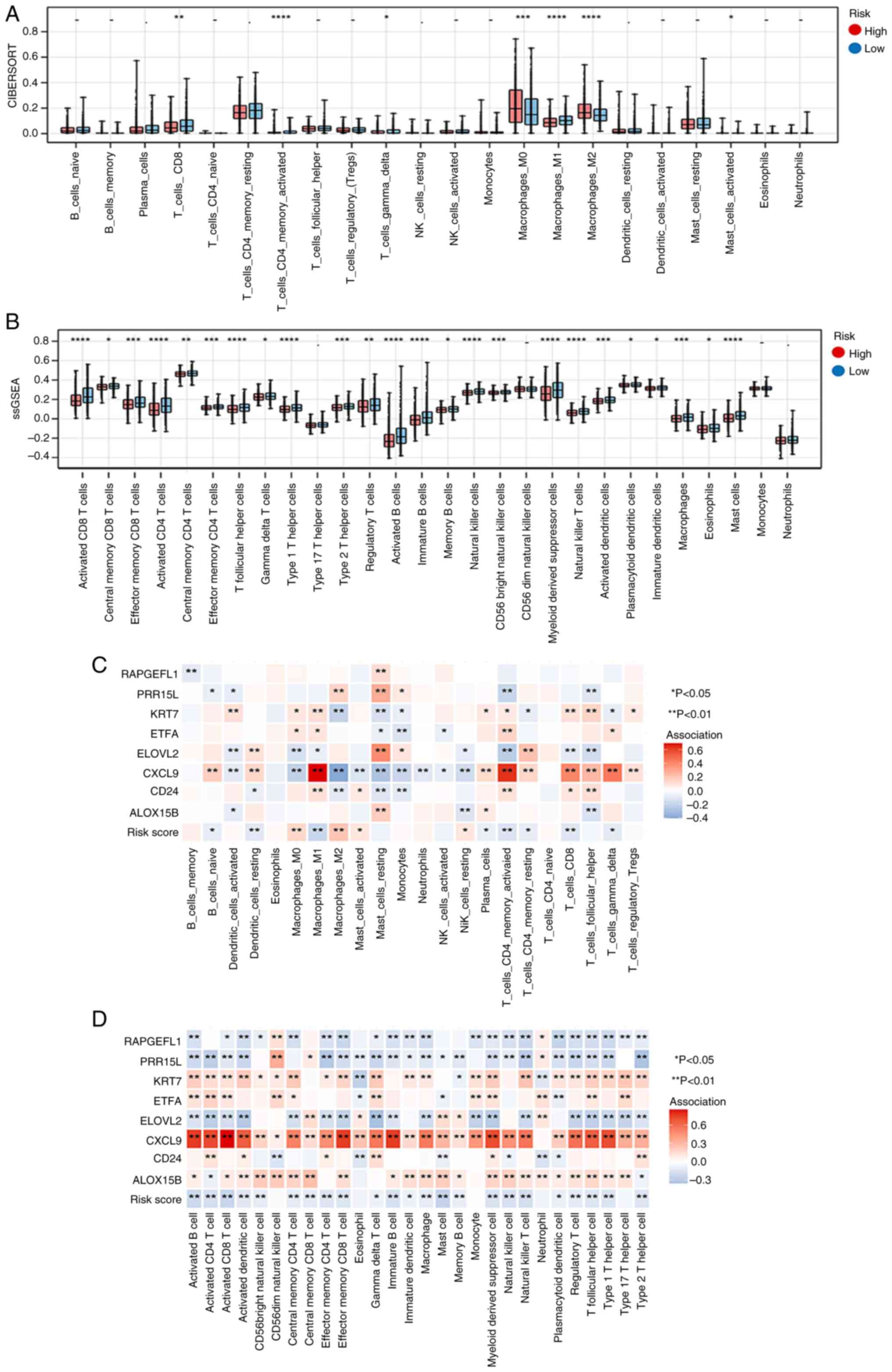

A significant difference was observed in the

proportions of 7 and 24 immune cell types between the high- and

low-risk groups according to the results of ‘CIBERSORT’ and

‘ssGSEA’ analyses, respectively (Fig.

6A and B, respectively). The associations of 22 and 28 immune

cell types with eight key genes are shown in Fig. 6C and D, respectively.

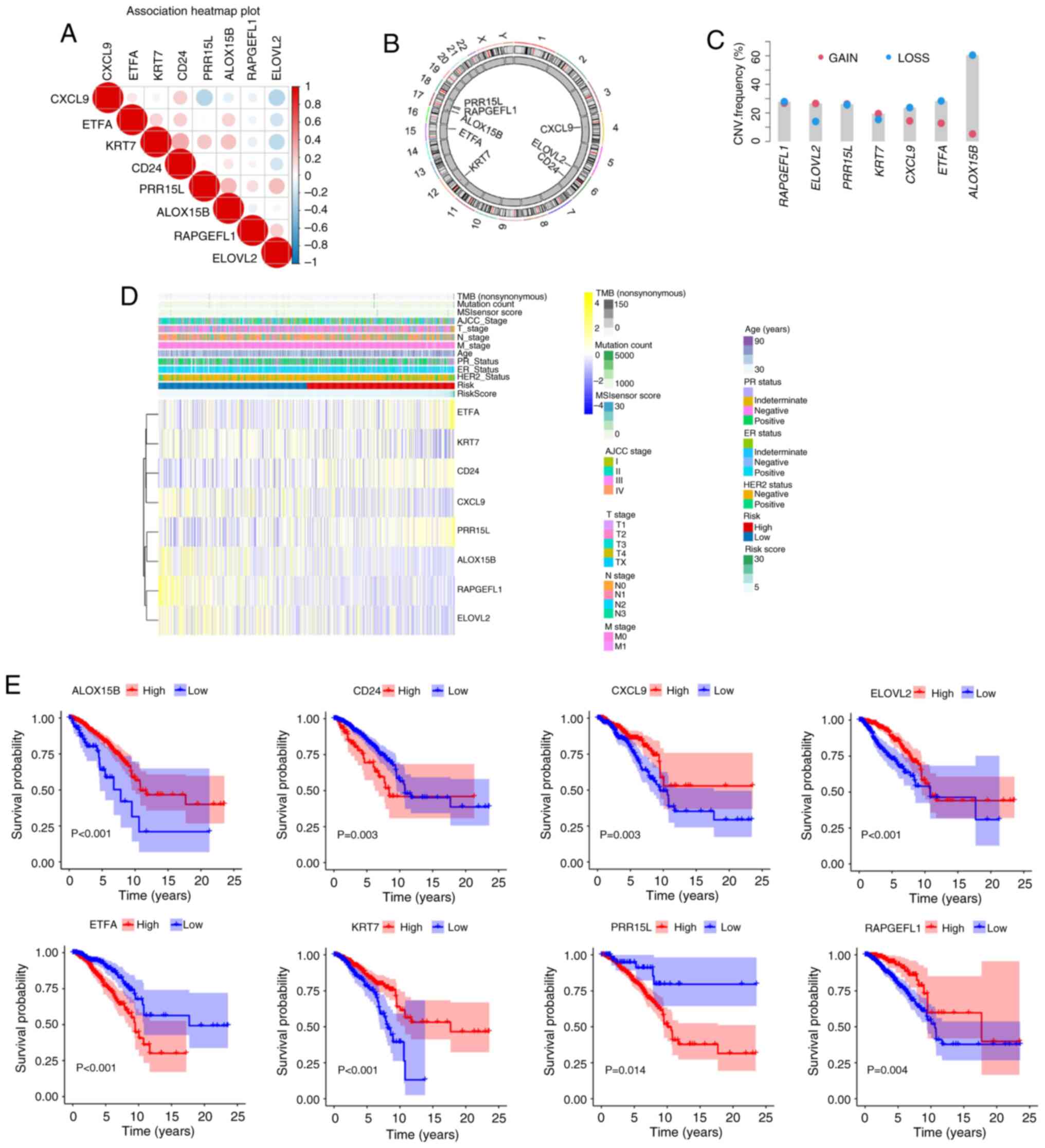

Characteristics of crucial genes

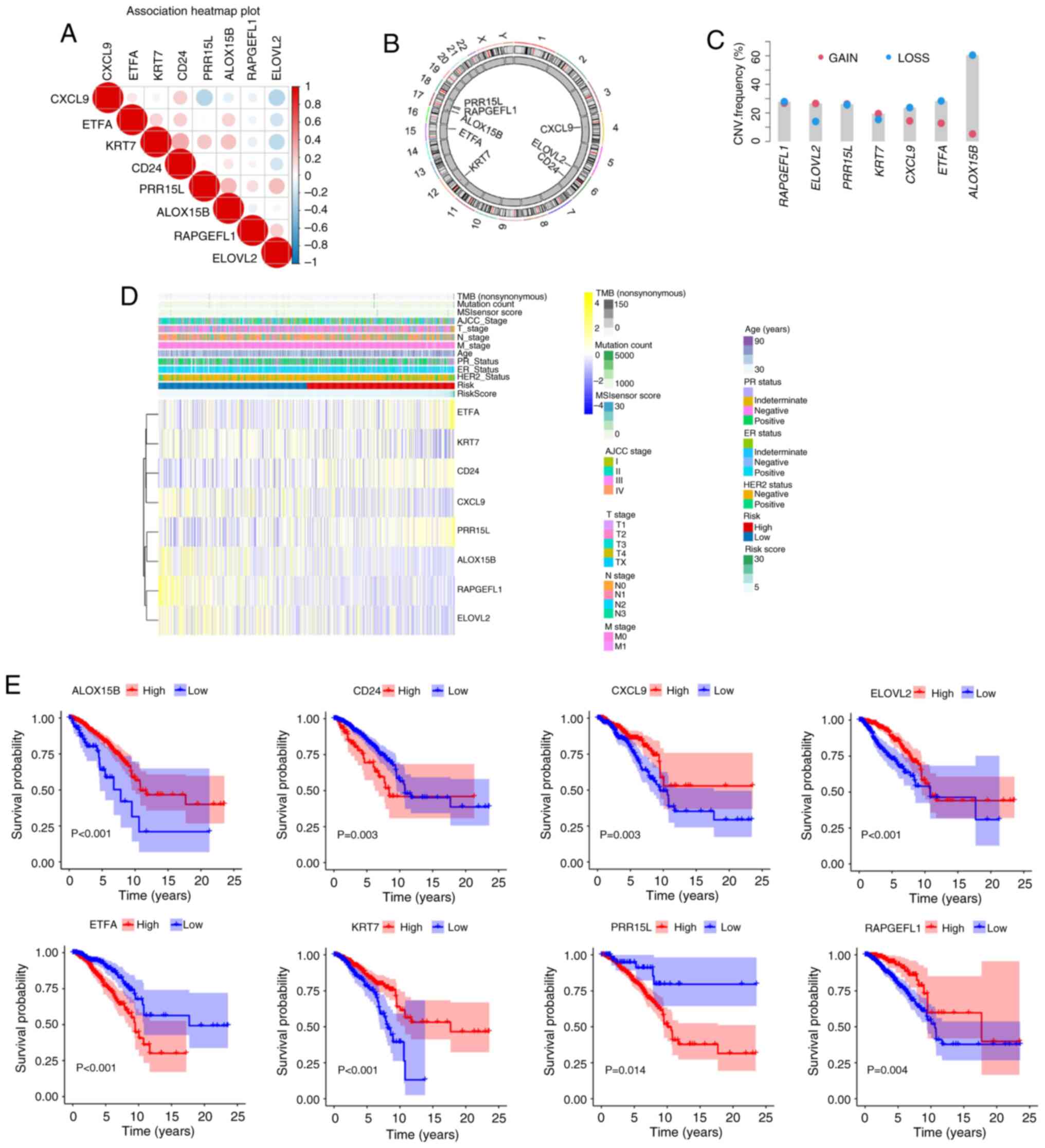

Spearman's correlation test was utilized to analyze

the association between the expression levels of the aforementioned

eight key genes and the prognosis of patients with breast cancer

was analyzed revealed a positive trend in general (Fig. 7A). Based on the circular graph, the

chromosomal localization distribution and copy number variation

(CNV) status of 8 model genes were visually mapped, clearly

presenting the positions of each gene on the chromosome and their

CNV alteration characteristics (Fig.

7B). The gain and loss trends are displayed in Fig. 7C. Fig.

7D shows heatmaps of the aforementioned eight key genes.

Survival analysis showed that the prognosis of patients with high

expression of CD24, ETFA and PRR15L was worse than that of patients

with low expression, whereas RAPGEFL1, KRT7, ALOX15B, ELOVL2 and

CXCL9 showed the opposite trend (all P<0.05; Fig. 7E).

| Figure 7.Characteristics of key genes (ETFA,

RAPGEFL1, KRT7, CD24, PRR15L, ALOX15B, ELOVL2 and CXCL9). (A)

Analysis of the association between the expression levels of the

eight key genes and the prognosis of patients with breast cancer

was analyzed revealed a positive trend in general. (B) CNV changes

of the above eight key genes on chromosomes. (C) CNV changes (gain

and loss trends) of the aforementioned eight key genes (there is no

relevant information about gene CD24 so a graph cannot be drawn).

(D) Heatmap of the expression of eight crucial genes. (E) Survival

analysis patients with different levels of expression of the

aforementioned eight crucial genes. Note: Survival curves were

constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test

was employed to compare survival differences between groups,

provided the proportional hazards assumption held (ETFA, RAPGEFL1,

KRT7, PRR15L, ALOX15B, and CXCL9 genes). For time-to-event data

with intermediate events, the two-stage survival analysis method

from the Two Stage Hazard Rate Comparison (TSHRC) package (Version

0.1-6) was applied when the proportional hazards assumption was

violated (CD24 and ELOVL2 genes). CNV, copy number variation; TMB,

tumor mutation burden; M, metastasis; N, node; T, tumor; AJCC,

American Joint Committee on Cancer; HER2, human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone

receptor. ETFA, electron transfer flavoprotein subunitα; RAPGEFL1,

rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor-like 1; KRT7, keratin 7;

CD24, cluster of differentiation 24; PRR15L, proline rich 15-like;

ALOX15B, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase type B; ELOVL2, ELOVL fatty

acid elongase 2; CXCL9, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9. |

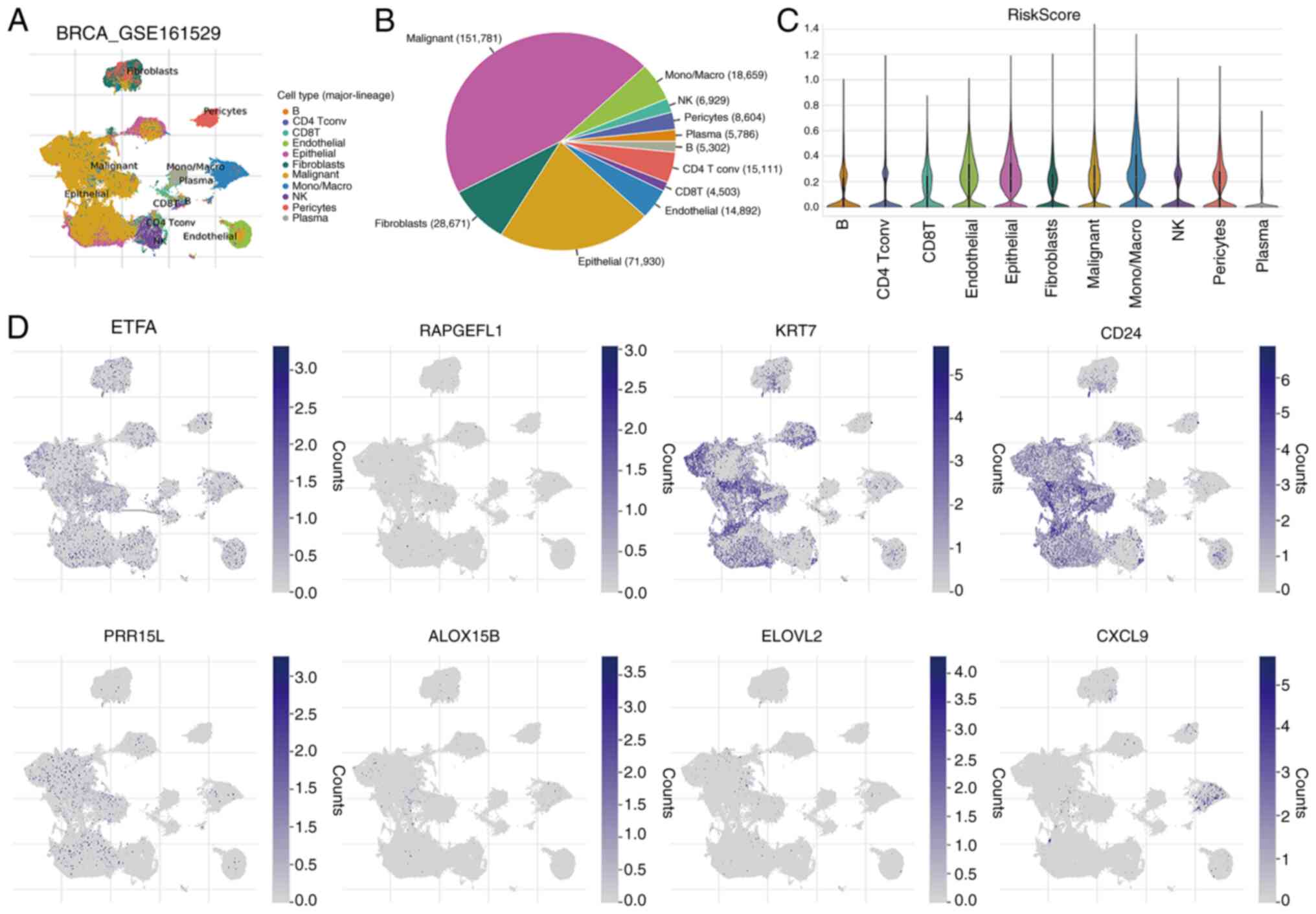

Single cell analysis

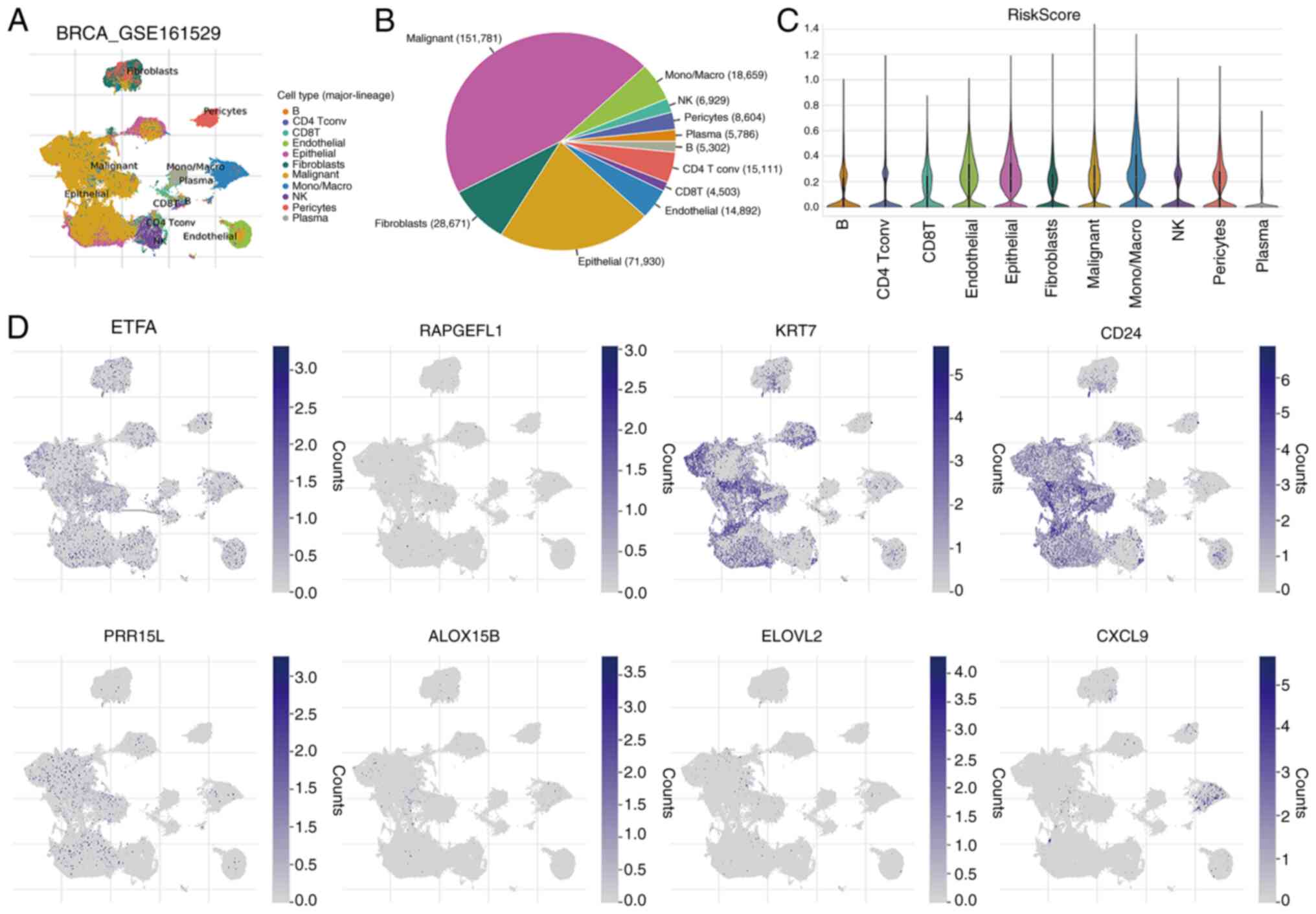

The GSE161529 single-cell dataset was used to

explore the expression of the aforementioned eight crucial genes in

the immune microenvironment, and the results revealed the

involvement of 11 cell types (Fig.

8A). The distribution and percentage of these cell types are

displayed in Fig. 8B. The largest

proportions corresponded to malignant and epithelial cells.

Fig. 8C shows the distribution of

the RiskScore in the 11 cell types. In addition, immune

microenvironment analysis revealed that the aforementioned eight

key genes were expressed in various immune cells (Fig. 8D).

| Figure 8.Single cell analysis. (A) Levels of

eight key genes in 11 cell types based on the single-cell dataset

GSE161529. (B) Distribution and percentage of 11 cell types. (C)

Distribution of RiskScore in the above 11 cell types. (D)

Expression pattern of the aforementioned eight key genes in immune

cells. NK, natural killer; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; Tconv,

Tconvoluted; Mono/Macro, monocyte/macrophage; ETFA, electron

transfer flavoprotein subunitα; RAPGEFL1, rap guanine nucleotide

exchange factor-like 1; KRT7, keratin 7; CD24, cluster of

differentiation 24; PRR15L, proline rich 15-like; ALOX15B,

arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase type B; ELOVL2, ELOVL fatty acid

elongase 2; CXCL9, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9. |

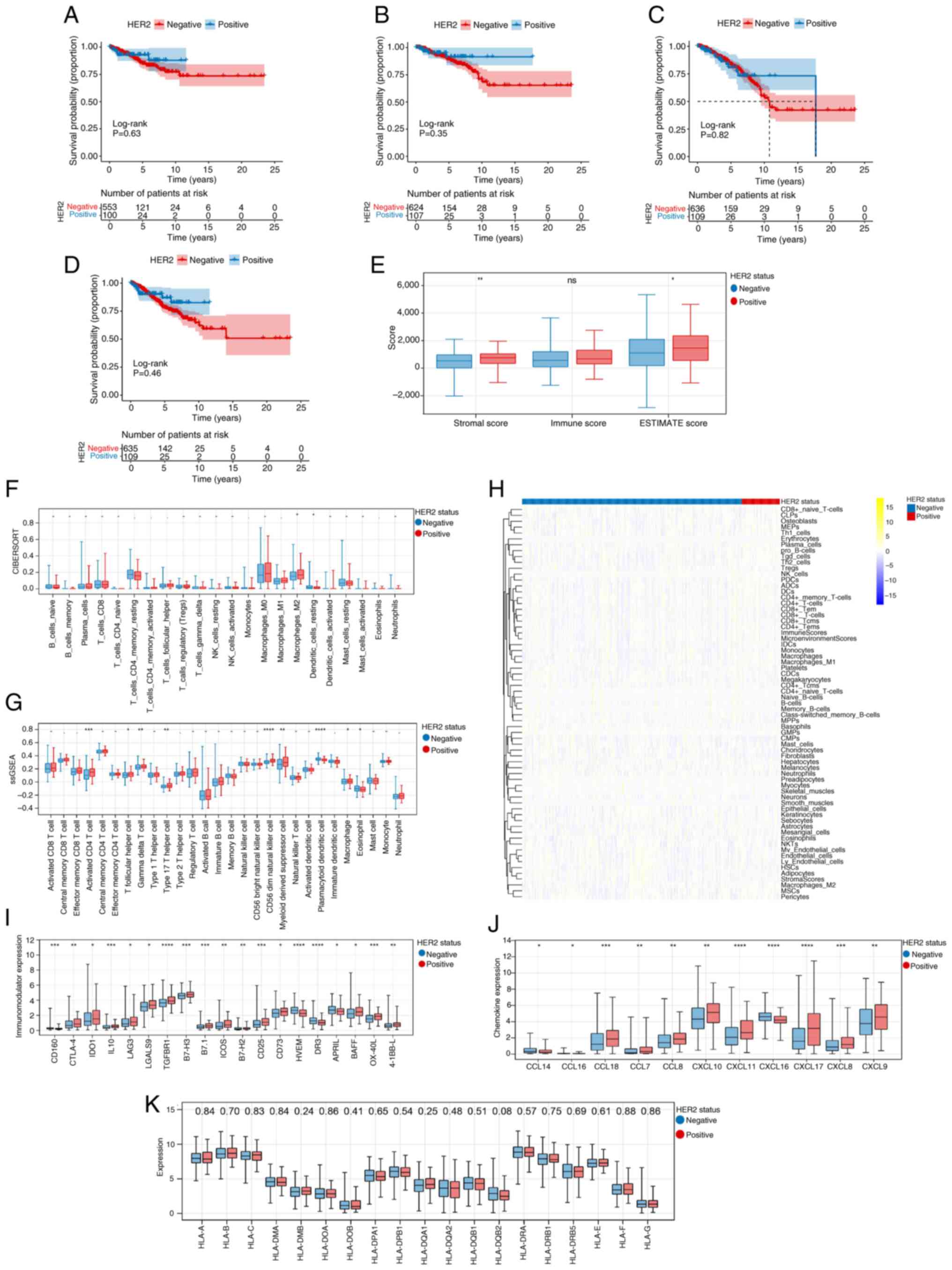

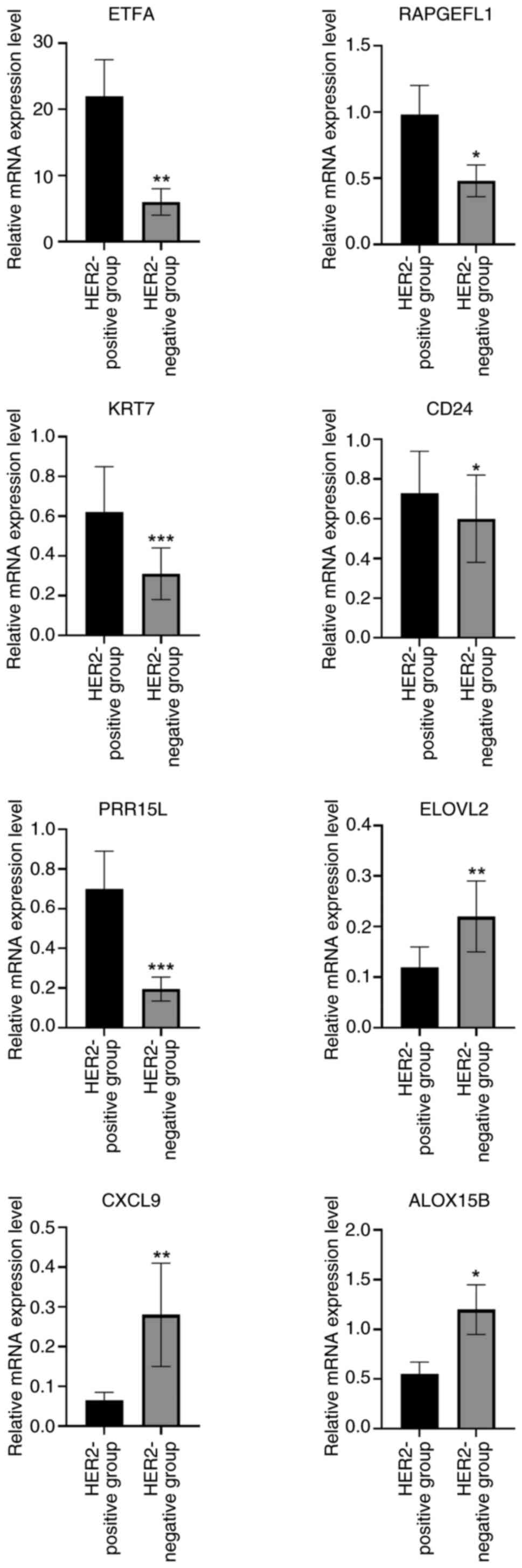

Validation results

RT-qPCR was performed to validate the expression of

eight crucial genes (ETFA, RAPGEFL1, KRT7, CD24, PRR15L, ALOX15B,

ELOVL2 and CXCL9). As shown in Fig.

9, the assays confirmed that ETFA, RAPGEFL1, KRT7, CD24 and

PRR15L were significantly upregulated in the HER2-positive groups,

whereas ELOVL2, CXCL9 and ALOX15B were significantly downregulated,

compared with the HER2-negative group. ELOVL2 is a novel tumor

suppressor with low expression in breast cancer (31). In prostate cancer, high expression

of ELOVL2 suggests improved prognosis, and small hairpin RNA

targeting ELOVL2 promotes cell proliferation, colony formation,

migration and invasion, as well as the growth of subcutaneous

xenografts by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (32). Therefore, ELOVL2 was selected in the

present study for follow-up experiments.

| Figure 9.RT-qPCR was performed to validate the

expression of eight crucial genes (ETFA, RAPGEFL1, KRT7, CD24,

PRR15L, ALOX15B, ELOVL2 and CXCL9). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2;

ETFA, electron transfer flavoprotein subunitα; RAPGEFL1, rap

guanine nucleotide exchange factor-like 1; KRT7, keratin 7; CD24,

cluster of differentiation 24; PRR15L, proline rich 15-like;

ALOX15B, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase type B; ELOVL2, ELOVL fatty

acid elongase 2; CXCL9, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9. |

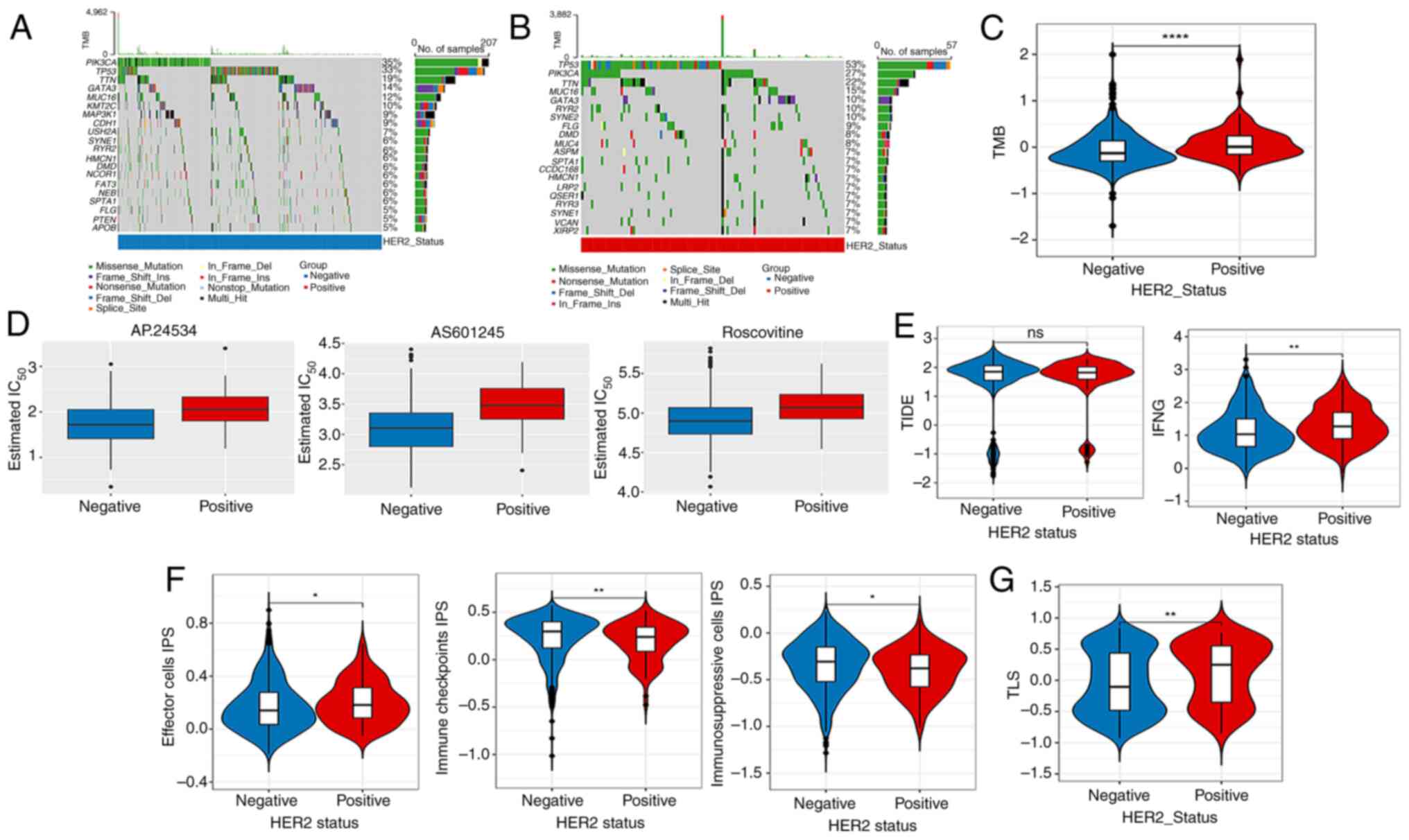

ELOVL2 overexpression inhibits the

proliferation of HER2-positive breast cancer cells by inhibiting

the PI3K-AKT pathway

The RT-qPCR results showed that the expression of

ELOVL2 was significantly lower in BT474 and SKBR-3 cells than in

MDA-MB-468 cells (P<0.001; Fig.

10A). In addition, RT-qPCR revealed that OE-ELOVL2

significantly increased the expression of ELOVL2 in BT474 and

SKBR-3 cells, suggesting successful transfection (P<0.001;

Fig. 10B). Furthermore, the CCK-8

proliferation assay showed that OE-ELOVL2 significantly inhibited

the proliferation of BT474 and SKBR-3 cells (P<0.01; Fig. 10C). Western blot analysis showed no

significant difference in the expression levels of PI3K or AKT in

the OE-ELOVL2 group compared to the negative control group, whereas

overexpression of ELOVL2 could decrease the levels of p-PI3K and

p-AKT proteins. In addition, compared with the corresponding

control group, the p-AKT/AKT and p-PI3K/PI3K ratios in the

OE-ELOVL2 groups of both BT474 and SKBR-3 cell lines were

significantly decreased (P<0.001; Fig. 10D). In conclusion, ELOVL2

overexpression inhibits HER2-positive breast cancer cell

proliferation by inhibiting the PI3K-AKT pathway.

Discussion

The oncogenic potential and activation of HER2 have

been well established in various human tumors (33). In the present study, HER2 expression

was significantly associated with ER status, PR status, N stage,

AJCC stage, mutation count and TMB in breast cancer. Therefore, the

molecular mechanisms underlying the involvement of HER2 in breast

cancer were investigated. A total of 251 DEGs between HER2-negative

and-positive groups were screened, and these DEGs were

significantly enriched in the KEGG pathways of estrogen signaling

pathway, chemical carcinogenesis-receptor activation and PI3K-AKT

signaling pathway. Numerous studies have shown that these pathways

are strongly associated with tumor progression. The PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway is activated through the generation of 3′

p-phosphoinositides, which plays a crucial role in multidrug

resistance in several cancer types such as breast cancer (34,35).

The chemical carcinogenesis receptor activation pathway is involved

in several diseases (36,37). Estrogen is involved in the

metabolism of normal physiological processes and diseases, and the

metabolic profile of endogenous breast cancer subtypes changes

according to estrogen receptor expression (38). Therefore, it can be proposed that

HER2-related DEGs participate in breast cancer progression through

these pathways. However, this conclusion needs to be verified

experimentally.

The TME plays a major role in tumorigenesis

(39,40). Stromal and ESTIMATE scores, known as

prognostic factors for tumors, are strongly linked to the tumor

immune microenvironment, with higher scores associated with worse

overall survival (41,42). The current results align with the

above findings, showing that stromal and ESTIMATE scores in the

HER2-positive group were increased compared to those in the

HER-negative group. Furthermore, the immune cell scores of the

HER2-negative and -positive groups were calculated. The ‘CIBERSORT’

and ‘xCELL’ algorithms revealed that the fraction of M2 macrophages

showed marked differences between different HER2 groups. An

increasing body of evidence indicates that M2 macrophages promote

tumor growth and invasion (43–45).

Yamaguchi et al (46)

reported that M2 macrophages are involved in the development of

peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. Additionally, the

present study also identified 19 checkpoint genes, and 11 chemokine

genes exhibited notable differences between the HER2-negative and

-positive groups. Therefore, it can be considered that these immune

cells, 19 checkpoint genes and 11 chemokine genes may participate

in the development of HER2-positive breast cancer, providing

reliable targets for immunotherapy of HER2-positive breast

cancer.

The IC50 differences of 138

chemotherapeutic agents between HER2-negative and -positive groups

were analyzed, and the top three chemotherapeutic agents with

significant differences were identified, including AS601245,

AP.24534 and roscovitine. Previous evidence suggests that

activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) can promote tumor

progression and is implicated in several types of tumors (47,48).

AS601245 is an inhibitor of JNK signaling (47), and Luo et al (49) suggested that AS601245 may be a new

inhibitor of breast cancer. AP.24534, known as ponatinib, is a

pan-fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor (50). Ponatinib is currently used for the

treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (51), and is presently in clinical trials

as an anticancer drug (52).

Roscovitine is a small molecule that inhibits the activity of

cyclin-dependent kinases by competitively binding to ATP-binding

sites (53). Previous studies have

confirmed that roscovitine blocks the cell cycle of cancer cells

(54,55) and has synergistic effects with other

anticancer drugs (56). In the

present study, the IC50 values of the aforementioned top

three chemotherapy drugs were higher in the HER2-positive group

than in the HER2-negative group. Thus, AS601245, AP.24534 and

roscovitine show promise for clinical application in HER2-positive

breast cancer treatment.

In addition, a prognostic risk model was constructed

using ETFA, RAPGEFL1, KRT7, CD24, PRR15L, ALOX15B, ELOVL2 and

CXCL9. Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of these

genes in various cancer types. Chen et al (57) revealed that ETFA expression was

upregulated in colorectal cancer, and that NBPF4 suppressed the

progression of colorectal cancer by controlling the activity of

EZH2-associated ETFA. Zhou et al (58) observed the amplification of

RAPGEFL1 in HER2-positive gastric cancer samples. KRT7

belongs to the family of genes known as keratins, which are highly

expressed in numerous types of cancer and facilitate tumor

progression (59,60). CD24 regulates the physiological

activity of cancer cells (61).

Furthermore, Li et al (62)

reported that p53 induced iron death in bladder cancer cells by

stimulating the lipoxygenase function of ALOX15B via suppression of

SLC7A11. Hu et al (32)

showed that ELOVL2 inhibited cell invasion, migration and

proliferation in prostate cancer by modulating the activity of the

cancer suppressor INPP4B. Seitz et al (63) demonstrated that CXCL9 inhibited

tumor progression and enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 treatment

in ovarian cancer. PRR15L is overexpressed in certain cancer types

(64). More importantly, RT-qPCR

analysis suggested that the expression of ETFA, RAPGEFL1, KRT7,

CD24, PRR15L, ALOX15B, ELOVL2 and CXCL9 was consistent with the

results of the bioinformatic analysis, indicating the reliability

and robustness of the present study. Therefore, the above eight

genes may be useful treatment targets for breast cancer.

Nomograms are valuable prognostic tools, including

personalized applications and intuitive visual representations

(65). In the current study, a

nomogram was built using age, M stage and RiskScore, which

demonstrated high accuracy in estimating the survival probabilities

of individuals diagnosed with breast cancer, with ROC curves

showing AUCs >0.75 at 1, 3 and 5 years, indicating an accurate

predictive capability for survival. Wang et al (66) constructed a prognostic model for

HER2-positive breast cancer based on nine autophagy-related genes

(ARGs). The analytical methods used in that study are consistent

with those used in the present study, and all the constructed

prognostic models exhibited good accuracy and predictive ability.

Zhao et al (67) constructed

a prognostic model for predicting male patients with HER2-positive

breast cancer, and the accuracy of this model was verified using

calibration curves and decision curve analysis. The model genes

found in the current study are different from those found in the

models of the studies by Wang et al (66) and Zhao et al (67), which may be due to the different

datasets selected. Wang et al (66) mainly studied ARGs, while Zhao et

al (67) studied male patients

with breast cancer, resulting in the selection of datasets and

final model genes that are not consistent with the present study.

Furthermore, a previous study found that a risk model composed of

PTGDR, PNOC and CCL23 was helpful in predicting the prognosis of

HER2-positive breast cancer, and that patients with low risk scores

may benefit from immunotherapy (68). In general, the current and previous

studies have shown that the constructed models are accurate and

reliable, and can help clinicians select appropriate treatment

strategies for HER2-positive breast cancer. However, these models

require further investigations. Therefore, in the present study,

the molecular mechanisms of the key gene ELOVL2 in HER2-positive

breast cancer were preliminarily explored. The results showed that

ELOVL2 overexpression inhibited the proliferation of HER2-positive

breast cancer cells by inhibiting the PI3K-AKT pathway, suggesting

that ELOVL2 is a potential target gene for the treatment of

patients with HER2-positive breast cancer, laying the foundation

for targeted therapy and improving the clinical adaptability of

this model.

However, the current study has several limitations.

First, the small sample size may have affected the accuracy of the

results. Second, the molecular mechanisms of key genes affecting

the prognosis of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer require

further exploration. Third, the screened drugs must be validated

experimentally. Therefore, future studies should collect additional

cases, include a larger number of clinical samples, and conduct

relevant clinical studies to provide effective personalized

treatment plans or targeted therapies for patients and to improve

their prognosis.

In conclusion, a valuable prognostic model that

included eight HER2-related genes was developed in the current

study. This model could accurately evaluate the survival rate of

patients with HER2-positive breast cancer, and provide effective

indicators or therapeutic targets for HER2-positive breast cancer.

The present findings provide a new direction for the development of

novel immunotherapeutic targets and personalized treatment for

HER2-positive breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Weifang City Science and

Technology Development Plan Project (grant no. 2022YX016).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LH, CX, YS, FS, XS, HY, ML and NL contributed to the

conception and design of the study. Material preparation and

drafting of the manuscript were performed by LH and CX. Acquisition

of data was performed by YS and FS. Analysis and interpretation of

data were conducted by XS and XY. Statistical analysis was

performed by ML. Revision of the manuscript for important

intellectual content were conducted by NL. LH and CX confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki, and received ethics approval from the

Weifang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine Ethics Committee

(approval no. WF2023-428/2023.4.23). All the participants provided

written informed consent for participation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Newman LA, Freedman

RA, Smith RA, Star J, Jemal A and Siegel RL: Breast cancer

statistics 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:477–495. 2024.

|

|

2

|

Xiong X, Zheng LW, Ding Y, Chen YF, Cai YW

and Wang LP: Huang L, Liu CC, Shao ZM and Yu KD: Breast cancer:

Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

10:492025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S,

Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N and Chen W: Cancer statistics in China

and United States, 2022: Profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin

Med J (Engl). 135:584–590. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yin Y, Song L, Shi D, Liu B, Li X, Yang M,

Liu B, Wang D and Qin J: Identification of recurrent insertions and

deletions in exon 18 and 19 of human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2 as potential drivers in non-small-cell lung cancer and

other cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 6:e21003252022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cheng X: A comprehensive review of HER2 in

cancer biology and therapeutics. Genes (Basel). 15:9032024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Marchiò C, Annaratone L, Marques A,

Casorzo L, Berrino E and Sapino A: Evolving concepts in HER2

evaluation in breast cancer: Heterogeneity, HER2-low carcinomas and

beyond. Semin Cancer Biol. 72:123–135. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chen Z, Yang L, Yang Z, Wang Z, He W and

Zhang W: Ultrasonic-responsive piezoelectric stimulation enhances

sonodynamic therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer. J

Nanobiotechnology. 22:3692024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ocaña A, Amir E and Pandiella A: HER2

heterogeneity and resistance to anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugates.

Breast Cancer Res. 22:152020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kang S and Kim SB: HER2-low breast cancer:

Now and in the future. Cancer Res Treat. 56:700–720. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shi Z, Liu Y, Fang X, Liu X, Meng J and

Zhang J: Efficacy and prognosis of HER2-low and HER2-zero in

triple-negative breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci

Rep. 14:168992024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Rizvi AA, Karaesmen E, Morgan M, Preus L,

Wang J, Sovic M, Hahn T and Sucheston-Campbell LE: gwasurvivr: An R

package for genome-wide survival analysis. Bioinformatics.

35:1968–1970. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, Newman AM

and Alizadeh AA: Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with

CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol. 1711:243–259. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Xiao B, Liu L, Li A, Xiang C, Wang P, Li H

and Xiao T: Identification and verification of immune-related gene

prognostic signature based on ssGSEA for osteosarcoma. Front Oncol.

10:6076222020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Aran D: Cell-type enrichment analysis of

bulk transcriptomes using xCell. Methods Mol Biol. 2120:263–276.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hu D, Zhou M and Zhu X: Deciphering

immune-associated genes to predict survival in clear cell renal

cell cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2019:25068432019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C

and Koeffler HP: Maftools: Efficient and comprehensive analysis of

somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28:1747–1756. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Geeleher P, Cox N and Huang RS:

pRRophetic: An R package for prediction of clinical

chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PLoS

One. 9:e1074682014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Reimand J, Isserlin R, Voisin V, Kucera M,

Tannus-Lopes C, Rostamianfar A, Wadi L, Meyer M, Wong J, Xu C, et

al: Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data

using g:Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nat Protoc.

14:482–517. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Tibshirani R: The lasso method for

variable selection in the Cox model. Stat Med. 16:385–395. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zhang S, Tong YX, Zhang XH, Zhang YJ, Xu

XS, Xiao AT, Chao TF and Gong JP: A novel and validated nomogram to

predict overall survival for gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. J

Cancer. 10:5944–5954. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wang L, Peng F, Li ZH, Deng YF, Ruan MN,

Mao ZG and Li L: Identification of AKI signatures and

classification patterns in ccRCC based on machine learning. Front

Med (Lausanne). 10:11956782023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gustavsson EK, Zhang D, Reynolds RH,

Garcia-Ruiz S and Ryten M: ggtranscript: An R package for the

visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using

ggplot2. Bioinformatics. 38:3844–3846. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang H, Meltzer P and Davis S: RCircos:

An R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinformatics.

14:2442013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Pal B, Chen Y, Vaillant F, Capaldo BD,

Joyce R, Song X, Bryant VL, Penington JS, Di Stefano L, Tubau

Ribera N, et al: A single-cell RNA expression atlas of normal,

preneoplastic and tumorigenic states in the human breast. EMBO J.

40:e1073332021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Han Y, Wang Y, Dong X, Sun D, Liu Z, Yue

J, Wang H, Li T and Wang C: TISCH2: Expanded datasets and new tools

for single-cell transcriptome analyses of the tumor

microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1): D1425–D1431. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kokot A, Gadakh S, Saha I, Gajda E,

Łaźniewski M, Rakshit S, Sengupta K, Mollah AF, Denkiewicz M,

Górczak K, et al: Unveiling the molecular mechanism of trastuzumab

resistance in SKBR3 and BT474 cell lines for HER2 positive breast

cancer. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 46:2713–2740. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ogitani Y, Hagihara K, Oitate M, Naito H

and Agatsuma T: Bystander killing effect of DS-8201a, a novel

anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody-drug

conjugate, in tumors with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

heterogeneity. Cancer Sci. 107:1039–1046. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Jeong D, Ham J, Kim HW, Kim H, Ji HW, Yun

SH, Park JE, Lee KS, Jo H, Han JH, et al: ELOVL2: A novel tumor

suppressor attenuating tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Am J

Cancer Res. 11:2568–2589. 2021.

|

|

32

|

Hu T, Zhang H, Du Y, Luo S, Yang X, Zhang

H, Feng J, Chen X, Tu X, Wang C and Zhang Y: ELOVL2 restrains cell

proliferation, migration, and invasion of prostate cancer via

regulation of the tumor suppressor INPP4B. Cell Signal.

96:1103732022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Vranić S, Bešlija S and Gatalica Z:

Targeting HER2 expression in cancer: New drugs and new indications.

Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 21:1–4. 2021.

|

|

34

|

Rittler D, Baranyi M, Molnár E, Garay T,

Jalsovszky I, Varga IK, Hegedűs L, Aigner C, Tóvári J, Tímár J and

Hegedűs B: The antitumor effect of lipophilic bisphosphonate

BPH1222 in melanoma models: The role of the PI3K/Akt pathway and

the small G protein Rheb. Int J Mol Sci. 20:49172019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Soltani A, Torki S, Ghahfarokhi MS, Jami

MS and Ghatrehsamani M: Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT

pathways by small molecules and natural compounds as a therapeutic

approach for breast cancer cells. Mol Biol Rep. 46:4809–4816. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ye X, Liu J, Yuan X, Yang S, Huang Y and

Chen Y: Molecular mechanism of Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge in

treating cerebral infarction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2022:59923942022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wu X, Pan J, Yu JJ, Kang J, Hou S, Cheng

M, Xu L, Gong L and Li Y: DiDang decoction improves mitochondrial

function and lipid metabolism via the HIF-1 signaling pathway to

treat atherosclerosis and hyperlipidemia. J Ethnopharmacol.

308:1162892023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kulkoyluoglu-Cotul E, Arca A and

Madak-Erdogan Z: Crosstalk between estrogen signaling and breast

cancer metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 30:25–38. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hinshaw DC and Shevde LA: The tumor

microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res.

79:4557–4566. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

de Visser KE and Joyce JA: The evolving

tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic

outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41:374–403. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Mao M, Yu Q, Huang R, Lu Y, Wang Z and

Liao L: Stromal score as a prognostic factor in primary gastric

cancer and close association with tumor immune microenvironment.

Cancer Med. 9:4980–4990. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Song J, Yang R, Wei R, Du Y, He P and Liu

X: Pan-cancer analysis reveals RIPK2 predicts prognosis and

promotes immune therapy resistance via triggering cytotoxic T

lymphocytes dysfunction. Mol Med. 28:472022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Xia Y, Rao L, Yao H, Wang Z, Ning P and

Chen X: Engineering macrophages for cancer immunotherapy and drug

delivery. Adv Mater. 32:e20020542020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Sun Y, Lian Y, Mei X, Xia J, Feng L, Gao

J, Xu H, Zhang X, Yang H, Hao X and Feng Y: Cinobufagin inhibits

M2-like tumor-associated macrophage polarization to attenuate the

invasion and migration of lung cancer cells. Int J Oncol.

65:1022024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhang Y, Chen S, You L, He Z, Xu P and

Huang W: LINC00161 upregulated by M2-like tumor-associated

macrophages promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by

methylating HACE1 promoters. Cytotechnology. 76:777–793. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Yamaguchi T, Fushida S, Yamamoto Y,

Tsukada T, Kinoshita J, Oyama K, Miyashita T, Tajima H, Ninomiya I,

Munesue S, et al: Tumor-associated macrophages of the M2 phenotype

contribute to progression in gastric cancer with peritoneal

dissemination. Gastric Cancer. 19:1052–1065. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Wu Q, Wu W, Jacevic V, Franca TCC, Wang X

and Kuca K: Selective inhibitors for JNK signalling: A potential

targeted therapy in cancer. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 35:574–583.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Bubici C and Papa S: JNK signalling in

cancer: In need of new, smarter therapeutic targets. Br J

Pharmacol. 171:24–37. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Luo W, Han Y, Li X, Liu Z, Meng P and Wang

Y: Breast cancer prognosis prediction and immune pathway molecular

analysis based on mitochondria-related genes. Genet Res (Camb).

2022:22499092022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Katoh M: FGFR inhibitors: Effects on

cancer cells, tumor microenvironment and whole-body homeostasis

(review). Int J Mol Med. 38:3–15. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Massaro F, Molica M and Breccia M:

Ponatinib: A review of efficacy and safety. Curr Cancer Drug

Targets. 18:847–856. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Katoh M and Nakagama H: FGF receptors:

Cancer biology and therapeutics. Med Res Rev. 34:280–300. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Cicenas J, Kalyan K, Sorokinas A,

Stankunas E, Levy J, Meskinyte I, Stankevicius V, Kaupinis A and

Valius M: Roscovitine in cancer and other diseases. Ann Transl Med.

3:1352015.

|

|

54

|

Raynaud FI, Whittaker SR, Fischer PM,

McClue S, Walton MI, Barrie SE, Garrett MD, Rogers P, Clarke SJ,

Kelland LR, et al: In vitro and in vivo

pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the

trisubstituted aminopurine cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors

olomoucine, bohemine and CYC202. Clin Cancer Res. 11:4875–4887.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

De Azevedo WF, Leclerc S, Meijer L,

Havlicek L, Strnad M and Kim SH: Inhibition of cyclin-dependent

kinases by purine analogues: Crystal structure of human cdk2

complexed with roscovitine. Eur J Biochem. 243:518–526. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lambert LA, Qiao N, Hunt KK, Lambert DH,

Mills GB, Meijer L and Keyomarsi K: Autophagy: A novel mechanism of

synergistic cytotoxicity between doxorubicin and roscovitine in a

sarcoma model. Cancer Res. 68:7966–7974. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Chen W, Di Z, Chen Z, Nan K, Gu J, Ge F,

Liu J, Zhang H and Miao C: NBPF4 mitigates progression in

colorectal cancer through the regulation of EZH2-associated ETFA. J

Cell Mol Med. 25:9038–9050. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Zhou C, Feng X, Yuan F, Ji J, Shi M, Yu Y,

Zhu Z and Zhang J: Difference of molecular alterations in

HER2-positive and HER2-negative gastric cancers by whole-genome

sequencing analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 10:3945–3954. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

An Q, Liu T, Wang MY, Yang YJ, Zhang ZD,

Liu ZJ and Yang B: KRT7 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition

in ovarian cancer via the TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling pathway. Oncol

Rep. 45:481–492. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Song J, Ruze R, Chen Y, Xu R, Yin X, Wang

C, Xu Q and Zhao Y: Construction of a novel model based on

cell-in-cell-related genes and validation of KRT7 as a biomarker

for predicting survival and immune microenvironment in pancreatic

cancer. BMC Cancer. 22:8942022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Altevogt P, Sammar M, Hüser L and

Kristiansen G: Novel insights into the function of CD24: A driving

force in cancer. Int J Cancer. 148:546–559. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Li X, Xiong W, Wang Y, Li Y, Cheng X and

Liu W: p53 activates the lipoxygenase activity of ALOX15B via

inhibiting SLC7A11 to induce ferroptosis in bladder cancer cells.

Lab Invest. 103:1000582023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Seitz S, Dreyer TF, Stange C, Steiger K,

Bräuer R, Scheutz L, Multhoff G, Weichert W, Kiechle M, Magdolen V

and Bronger H: CXCL9 inhibits tumour growth and drives anti-PD-L1

therapy in ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 126:1470–1480. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Mizuguchi Y, Sakamoto T, Hashimoto T,

Tsukamoto S, Iwasa S, Saito Y and Sekine S: Identification of a

novel PRR15L-RSPO2 fusion transcript in a sigmoid colon cancer

derived from superficially serrated adenoma. Virchows Arch.

475:659–663. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Wu J, Zhang H, Li L, Hu M, Chen L, Xu B

and Song Q: A nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients

with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based

analysis. Cancer Commun (Lond). 40:301–312. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Wang F, Fang L, Fu B and Fan C:

Construction of a prognostic risk assessment model for HER2 +

breast cancer based on autophagy-related genes. Breast Cancer.

30:478–488. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Zhao L, Lin Z, Nong S, Li C, Li J, Lin C,

Safi SZ, Huang S and Ismail ISB: Development and validation of a

prognostic nomogram model for HER2-positive male breast cancer

patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 25:3199–3207. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Lin J, Zhao A and Fu D: Evaluating the

tumor immune profile based on a three-gene prognostic risk model in

HER2 positive breast cancer. Sci Rep. 12:93112022. View Article : Google Scholar

|