Introduction

Cancer remains a major health burden. Lung cancer

ranks as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide,

accounting for ~1.8 million new cases and ~1.6 million deaths

annually (1). Non-small cell lung

cancer, which accounts for ~85% of all lung canc er cases, is of

particular concern as the majority of patients are diagnosed at

advanced or metastatic stages (2).

Although notable progress has been made in surgery, chemotherapy,

radiotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy, resistance to

treatment and relapse remain major challenges, thus highlighting

the need for novel therapeutic strategies (3–6).

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) offers unique

advantages due to its multi-target and multi-component nature, as

well as its relative low toxicity. Emerging evidence has

highlighted its role in cancer therapy, with research reporting

improvements in patient quality of life and an increase in the

efficacy and reduction of adverse effects of conventional therapies

(7,8). TCM exerts its therapeutic effects via

targeting several biomolecules, modulating downstream signaling

pathways and disrupting disease-associated networks (9,10).

Therefore, identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds

in TCM is a pivotal step toward understanding its underlying

therapeutic mechanisms and advancing their modern clinical

applications (11).

Despite marked progress in drug discovery,

elucidating the molecular targets of TCM compounds remains a major

challenge due to the lack of effective tools for investigating

small molecule-protein interactions. Conventional methods include

affinity chromatography (12),

activity-based protein profiling (13) and label-free approaches such as drug

affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) (14), oxidative rate-dependent protein

stability analysis (15) and

thermal proteome profiling (16–19).

For example, oxidative rate-dependent protein stability leverages

changes in protein oxidation kinetics upon ligand binding to

identify potential targets (15).

However, label-free methods commonly lack sufficient sensitivity,

whilst label-based techniques frequently require structural

modifications that can compromise compound activity (20). These limitations have hindered the

comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying TCM and

slowed their broader integration into modern therapeutic

applications.

The advent of clustered regularly interspaced short

palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)

genome-editing technology in 2013 has revolutionized functional

genomics research (21).

Genome-wide CRISPR libraries enable unbiased and high-throughput

screening of functional genes, thus offering transformative

potential in drug resistance (22),

tumor biology (23), immune

responses (24) and cancer

immunotherapy (25). Previous

applications of CRISPR-based screening in drug discovery have

supported its potential in identifying molecular targets of

bioactive compounds (26,27), thus providing novel insights into

its adoption in TCM research.

Berberine (BBR), a natural alkaloid extracted from

Coptis chinensis and related medicinal plants, exhibits

several biological activities, including anti-inflammatory,

antimicrobial and anticancer properties (28–30).

Notably, a previous study reported that BBR could inhibit lung

cancer cell proliferation (31).

However, its particular molecular mechanisms remain largely

unknown, thus limiting its therapeutic application. Recent studies

have demonstrated the anticancer versatility of BBR. For instance,

Li et al (32) reported that

BBR induced apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest across different cancer

cell lines. Additionally, Shen et al (33) reported that BBR delivered via

polyethylene glycol-poly-lactide co-glycolide acid nanocarriers

could enhance transcriptomic changes in colorectal cancer cells,

thus modulating the Wnt, TGF-β, Hippo and mammalian target of

rapamycin signaling pathways. Consistently, Sun et al

(34) reported the multifaceted

antitumor activities of BBR, including anti-inflammatory activity,

inhibition of angiogenesis and reversal of drug resistance. In

2024, a review article further summarized the effects of BBR on

nuclear factor κB, mitogen-activated protein kinase and

phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling, as well as

its synergistic effects with conventional therapies (35).

Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically

identify genes responsive to BBR in A549 lung cancer cells via

employing a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening library. This

approach could provide a powerful platform for identifying

molecular targets of TCM, thus contributing to a deeper

understanding of their mechanisms of action and accelerating their

integration into modern oncological practice.

Materials and methods

Reagents and instruments

BBR (purity ≥98%; cat. no. 2086-83-1) was purchased

from MedChemExpress. F-12K medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and

trypsin were purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

RIPA lysis buffer, protease inhibitor cocktail, western blot

reagents, Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8) assay and BCA protein assay

kits were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology. The cell culture

plates and microplate reader were purchased from Falcon (Corning

Life Sciences) and Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

respectively.

Cell culture

The A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cell line was

purchased from Shanghai Hanyu Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Cells were

maintained in F-12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in a

humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells cultured at a

maximum of 5–20 passages were used for all experiments. Routine

mycoplasma testing was performed and confirmed negative. Culture

medium was replaced every 2–3 days. The incubator was maintained at

~95% relative humidity to ensure optimal growth conditions. All

experiments, including CCK-8 assays, CRISPR screening, western

blotting and flow cytometry, were performed in at least three

independent biological replicates, each using separately cultured

cell batches. For all assays, cells in the logarithmic growth phase

were digested, counted and seeded as single-cell suspensions at a

density of 2,000 cells/well in 12-well plates, to ensure uniform

distribution. Edge wells were filled with sterile water to minimize

evaporation.

Cell viability assay

The effects of BBR on cell viability were assessed

using a CCK-8 assay. Briefly, cells were treated with 1–60 µM BBR

or with the corresponding control reagent (DMSO). Following

incubation for 72 h, each well was supplemented with 10 µl CCK-8

reagent, followed by incubation for an additional 2 h. Finally, to

quantify cell viability, the absorbance in each well was measured

at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader.

CRISPR/Cas9 genome-wide knockout

screening

A genome-wide CRISPR knockout library was generated

using the GeCKO v2.0 platform (36), encompassing 123,411 single-guide

(sg)RNAs targeting 19,050 human genes. The sgRNA plasmid library

(Addgene plasmid #1000000048) used in the present study may be

obtained through Addgene, Inc. (https://www.addgene.org/pooled-library/zhang-human-gecko-v2/),

and its use and construction have been previously described

(36). Each gene was targeted by

six independent sgRNAs distributed across constitutive exons to

maximize knockout efficiency.

To achieve comprehensive genome coverage,

~1.6×108 A549 cells were infected with lentiviral

particles at a multiplicity of infection of 0.3-0.5. Cells were

seeded in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene and subjected to spin

infection (450 × g at 37°C for 2 h), followed by replacement with

fresh medium. Cells were then selected with puromycin (1 µg/ml) for

14 days. To confirm stable expression, the expression levels of

Cas9 in A549 cells were assessed using western blot analysis. The

screening employed a single-vector lentiviral system (lentiCRISPR

v2; cat. no. 52961; Addgene, Inc.), in which both Cas9 and sgRNA

expression cassettes are integrated within the same backbone;

therefore, no additional Cas9 transfection was required.

Library quality was evaluated using next-generation

sequencing (NGS), which verified uniform sgRNA representation, with

>200-fold coverage per sgRNA. Genomic DNA was amplified using

the NEBNext High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix (cat. no. M0541; New

England Biolabs, Inc.) and purified using the QIAquick Gel

Extraction Kit (cat. no. 28704; Qiagen GmbH). The integrity of the

200- to 300-bp amplified fragments was verified by 1.5% agarose gel

electrophoresis prior to sequencing. Sequencing was performed on an

Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform using the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent

Kit v1.5 (cat. no. 20028312; Illumina, Inc.), generating paired-end

150 bp (PE150) reads at an average depth exceeding 300 times. The

final pooled library was loaded at a concentration of 1.457 µg/µl

(2.18×10−9 mol/µl), quantified using a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). To maintain

library complexity, a total of 4×107 cells were

collected every 3 days and stored at −80°C. For NGS, genomic DNA

was extracted on day 14, and candidate genes responsive to BBR were

identified using MAGeCKFlute (version 0.5) analysis (37). Genes were ranked based on the

changes in their sgRNA abundances between treatment and control

groups. Those significantly enriched or reduced (P<0.05) were

subsequently subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) classification and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment

analysis using the Omicsbean proteomics toolkit (www.omicsbean.cn).

Treatment of genome-wide edited cell

libraries with BBR

A549 cells harboring the CRISPR knockout library

were expanded and divided into the following three groups: i)

Untreated (control); ii) BBR-treated; and iii) vehicle-treated

(DMSO) groups. Cells in the experimental group were exposed to 10

µM BBR at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 3

days, whilst those in the control group were cultured under routine

conditions with regular medium changes and passaging. When cell

viability in the BBR-treated group reached ~10% of that of the

untreated group, genomic DNA was extracted for NGS to identify

sgRNA enrichment patterns.

Claudin (CLDN)-1 knockout and

lentiviral transduction

A second-generation lentiviral packaging system was

used for transduction. The lentiviral vector encompassing sgRNA

sequences targeting CLDN1 was constructed after cloning

oligonucleotide sequences (sgRNA-Z9, 5′-AGCGAGTCATGGCCAACGCG-3′;

sgRNA-Z10, 5′-GGCGCCGATCCATCCCAGGA-3′) into the lentiCRISPR v2

plasmid (cat. no. 52961; Addgene, Inc.). Prior to transduction, the

successful construction of plasmids was verified by Sanger

sequencing, which was performed by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.

(Shanghai, China) using an Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher

Scientific) platform. Lentiviral particles were produced in 293T

cells (ATCC CRL-3216) by co-transfecting the transfer plasmid

(lentiCRISPR v2) with the packaging plasmids psPAX2 (cat. no.

12260; Addgene, Inc.) and the envelope plasmid pMD2.G (cat. no.

12259; Addgene, Inc.) at a mass ratio of 2:1:1, using

polyethylenimine as the transfection reagent. Transfection was

performed at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

The viral supernatant was collected 48 and 72 h post-transfection,

pooled, filtered through a 0.45-µm filter and concentrated by

ultracentrifugation. A549 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at

~70% confluency and were then infected with lentiviral supernatant

at a multiplicity of infection of 5–10, containing 8 µg/ml

polybrene. Following incubation for 12 h at 37°C, the medium was

replaced with fresh F-12K supplemented with 10% FBS. Transduced

cells were subsequently selected with 2 µg/ml puromycin for 7 days

to establish stable CLDN1 knockout cell lines. A puromycin

concentration of 1 µg/ml was used for the maintenance of selected

cells. Following a 7-day recovery period after puromycin selection,

the cells were used for subsequent experimentation. Genomic DNA

from puromycin-resistant A549 cells was extracted using a genomic

DNA purification kit (Tiangen Biotech, Co., Ltd.), and the

CLDN1 target region encompassing the Z10 site was amplified

using PCR performed with PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio

Inc.) and the following primers: Forward,

5′-GCAACCGCAGCTTCTAGTATC-3′; and reverse,

5′-TGCACACTTGAGAAGTTACC-3′. The following thermocycling conditions

were applied: Initial denaturation at 98°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of

98°C for 10 sec, 58°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 15 sec; with a final

extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were separated on a 1.2%

agarose gel stained with GoldView (Takara Bio Inc.) and visualized

using a GelDoc XR+ imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). PCR

products were purified and subjected to Sanger sequencing by Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) to verify the successful genome

editing of CLDN1.

Western blot analysis

Protein lysates were prepared using NP-40 lysis

buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. The protein

concentration was measured using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein extract (20 µg per

lane) were first separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and were then

transferred to PVDF membranes. Following blocking with 3% bovine

serum albumin (Beyotime Biotechnology) at room temperature for 2 h,

the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following

primary antibodies: Anti-CLDN1 (1:1,000 dilution; cat. no.

28674-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-cyclin D1 (1:1,000

dilution; cat. no. 26939-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-Cas9

(1:1,000 dilution; cat. no. 26758-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

anti-GAPDH (1:5,000 dilution; cat. no. 10494-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) and anti-β-actin (1:5,000 dilution; cat. no.

66009-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.). Subsequently, the membranes

were incubated with corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG; 1:5,000 dilution; cat. no.

SA00001-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature,

and the immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced

chemiluminescence (BeyoECL Plus; cat. no. P0018S; Beyotime

Biotechnology).

Flow cytometry analysis

To assess the effects of BBR on cell cycle

progression, A549 and CLDN1-knockout A549 cells were treated

with 2.5 µM BBR, a sublethal dose slightly below the calculated

half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50; 2.856 µM).

This concentration was selected to minimize cytotoxicity whilst

allowing the detection of sensitization effects associated with

CLDN1 knockout. This was consistent with standard

pharmacological studies aiming to evaluate differential cellular

responses using sub-lethal or slightly sub-IC50

concentrations (38,39). Following incubation for 72 h, cells

were fixed with 70% ethanol, washed with PBS and stained with

propidium iodide. Samples were incubated at 37°C in the dark for 30

min prior analysis on a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter,

Inc.) equipped with a 488-nm laser. Data analysis was performed

using FlowJo software (version 8.0; FlowJo LLC).

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were statistically analyzed

using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (Dotmatics). Groups were compared

using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of BBR on A549 cell

proliferation

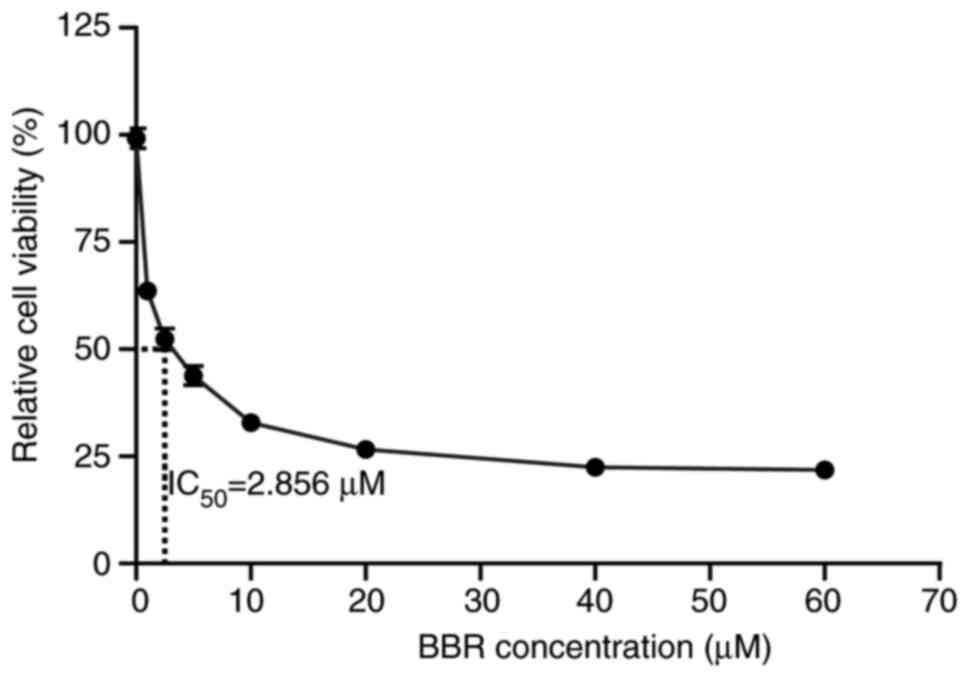

Previous studies have reported that BBR can inhibit

the growth of lung cancer cells, including that of A549 cells, in a

dose-dependent manner. However, effective concentrations vary among

different cell lines (40–42). Therefore, to determine the optimal

concentration of BBR in A549 cells, the cells were treated with

increasing concentrations of BBR (1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 60 µM)

and cell viability was then assessed using a CCK-8 assay. The

results revealed that BBR significantly reduced cell viability in a

dose-dependent manner, with only 21.5% of cells remaining viable at

a concentration of 60 µM (Fig. 1).

Analysis using GraphPad Prism software revealed that the

IC50 was 2.856 µM. These findings indicated that BBR

could effectively suppresses A549 cell proliferation, thus

providing a foundation for subsequent mechanistic experiments.

Construction of A549 genome-wide

knockout library and BBR target screening

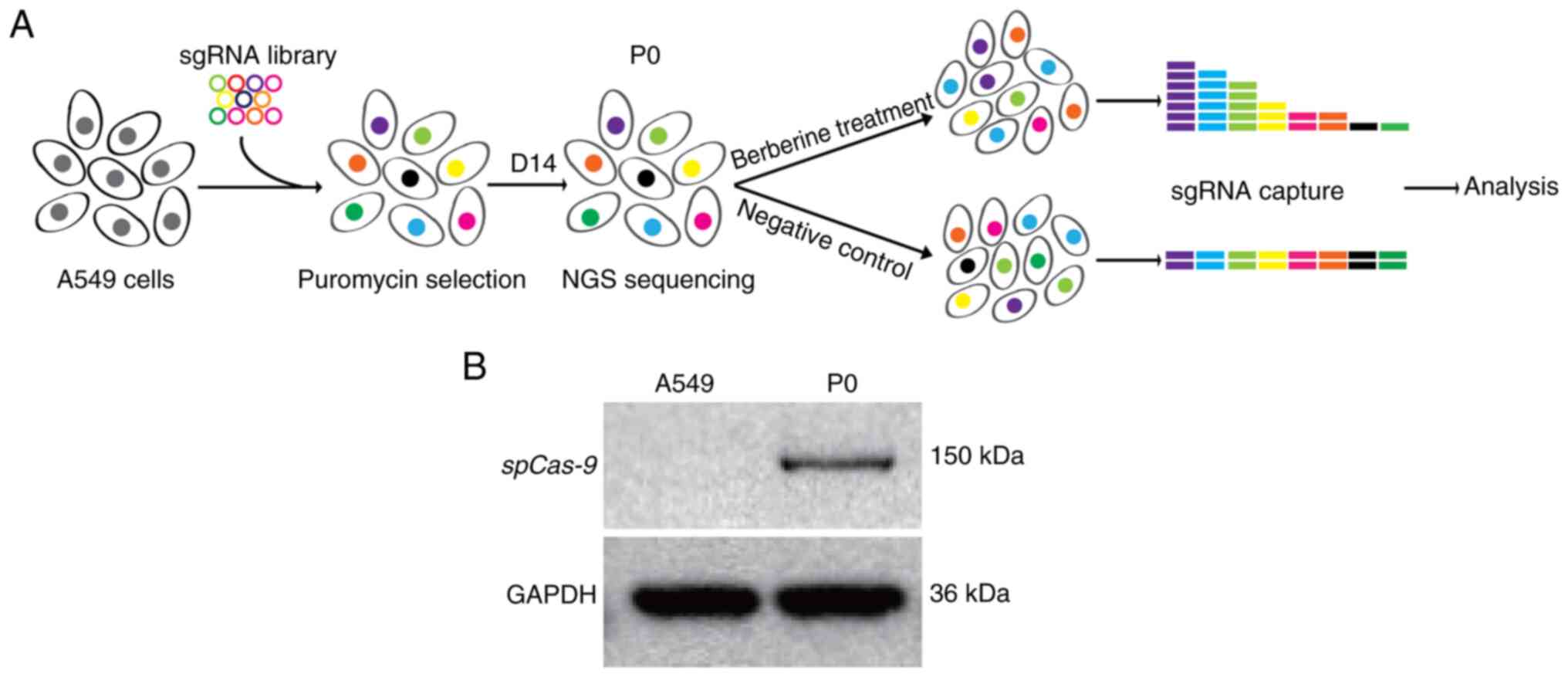

To comprehensively identify genes responsive to BBR

treatment, a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout library was

constructed in A549 cells (Fig.

2A). Library generation followed established protocols

(36), with lentiviral transduction

enabling stable expression of Streptococcus pyogenes

(sp)Cas9 in A549 cells. Western blot analysis was performed

to confirm the successful expression of spCas9 protein at the

expected molecular weight of 140–160 kDa (Fig. 2B). The resulting knockout library

was designated as P0. To assess the capacity of the library in

identifying BBR targets, P0 cells were treated with BBR until cell

viability reduced to ~10% of the untreated cell population.

Subsequently, genomic DNA was extracted from surviving cells, and

sgRNA sequence representation was determined using NGS. Candidate

genes were ranked based on positive (pos|score) or negative

(neg|score) selection values using the MAGeCK algorithm, with a

significance threshold of P<0.05. A total of 3,873 genes

exhibited significant differential selection, including 749

positively selected genes (associated with resistance) and 3,124

negatively selected ones (associated with sensitivity) (Tables SI and SII).

Enrichment analysis of resistance and

sensitivity genes

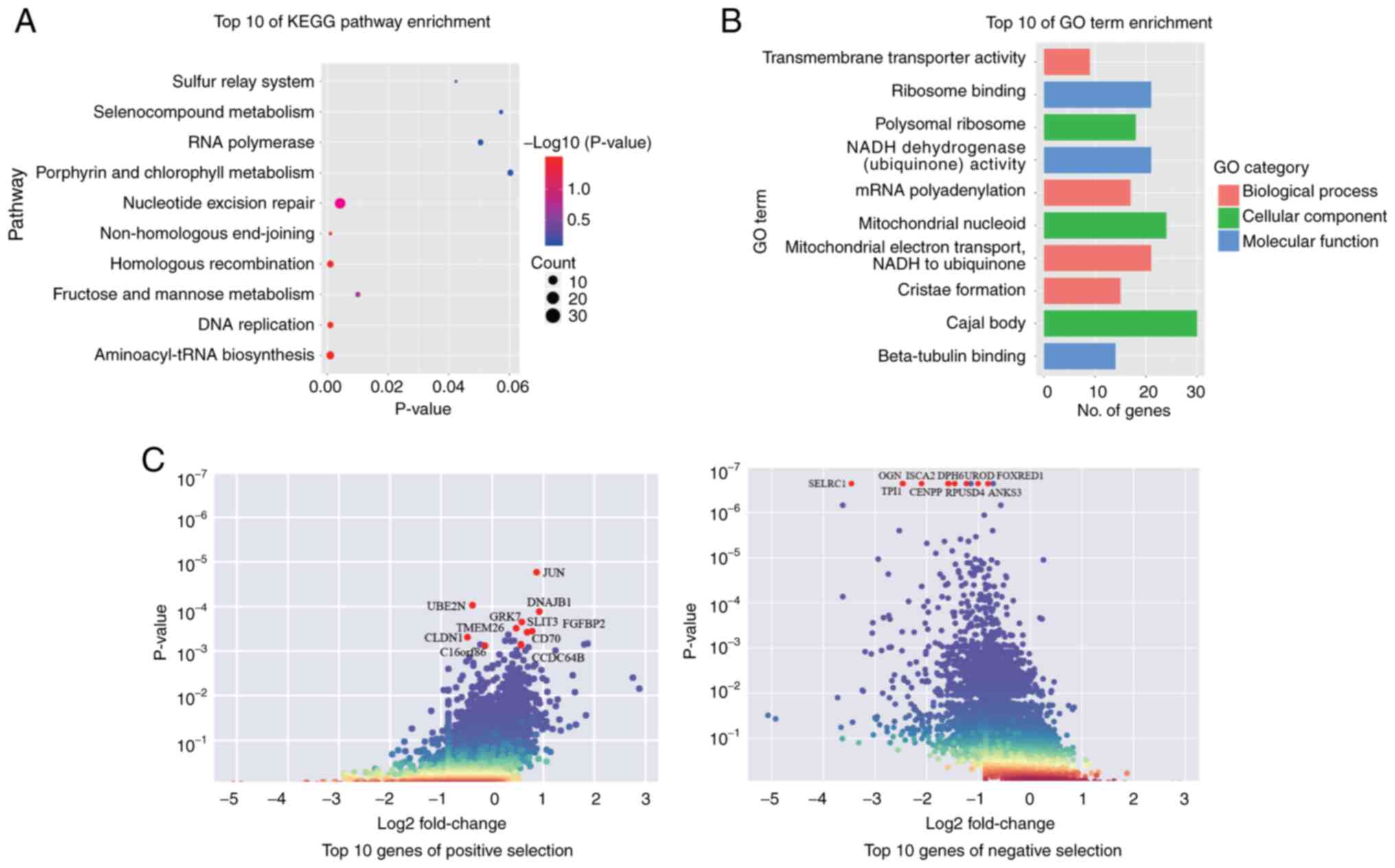

To elucidate the biological pathways underlying BBR

response, KEGG pathway and GO enrichment analyses were performed on

the differentially selected genes. KEGG analysis revealed that the

selected genes were mainly enriched in the ‘aminoacyl-tRNA

biosynthesis’, ‘homologous recombination’, ‘DNA replication’ and

‘non-homologous end-joining’ pathways (Fig. 3A). Notably, several DNA damage

repair-related pathways were highlighted, thus suggesting that BBR

could be associated with genomic stability and cell cycle

regulation. GO analysis further revealed that the selected genes

were enriched into the following molecular functions: ‘ribosome

binding’, ‘beta-tubulin binding’ and ‘NADH dehydrogenase activity’;

cellular components: ‘mitochondrial nucleoid’, ‘Cajal body’ and

‘polysomal ribosome’; and biological processes: ‘mitochondrial

electron transport’, ‘mRNA polyadenylation’ and ‘transmembrane

transporter activity’ (Fig. 3B).

These findings indicate that BBR could potentially disrupt cellular

energy metabolism and fundamental biological processes. Among the

top-ranked candidate genes (Fig.

3C), slit guidance ligand 3, DNAJ heat shock protein family

(Hsp40) member B1, ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 N and

CLDN1 were of particular interest due to their established

roles in lung cancer cell proliferation, invasion and drug

resistance (43–50). Notably, CLDN1, a member of

the CLDN family involved in tight junction integrity, has been

associated with tumor progression and chemoresistance in A549 cells

(50), highlighting its potential

as a compelling target for further investigation.

Functional validation of CLDN1 in BBR

response

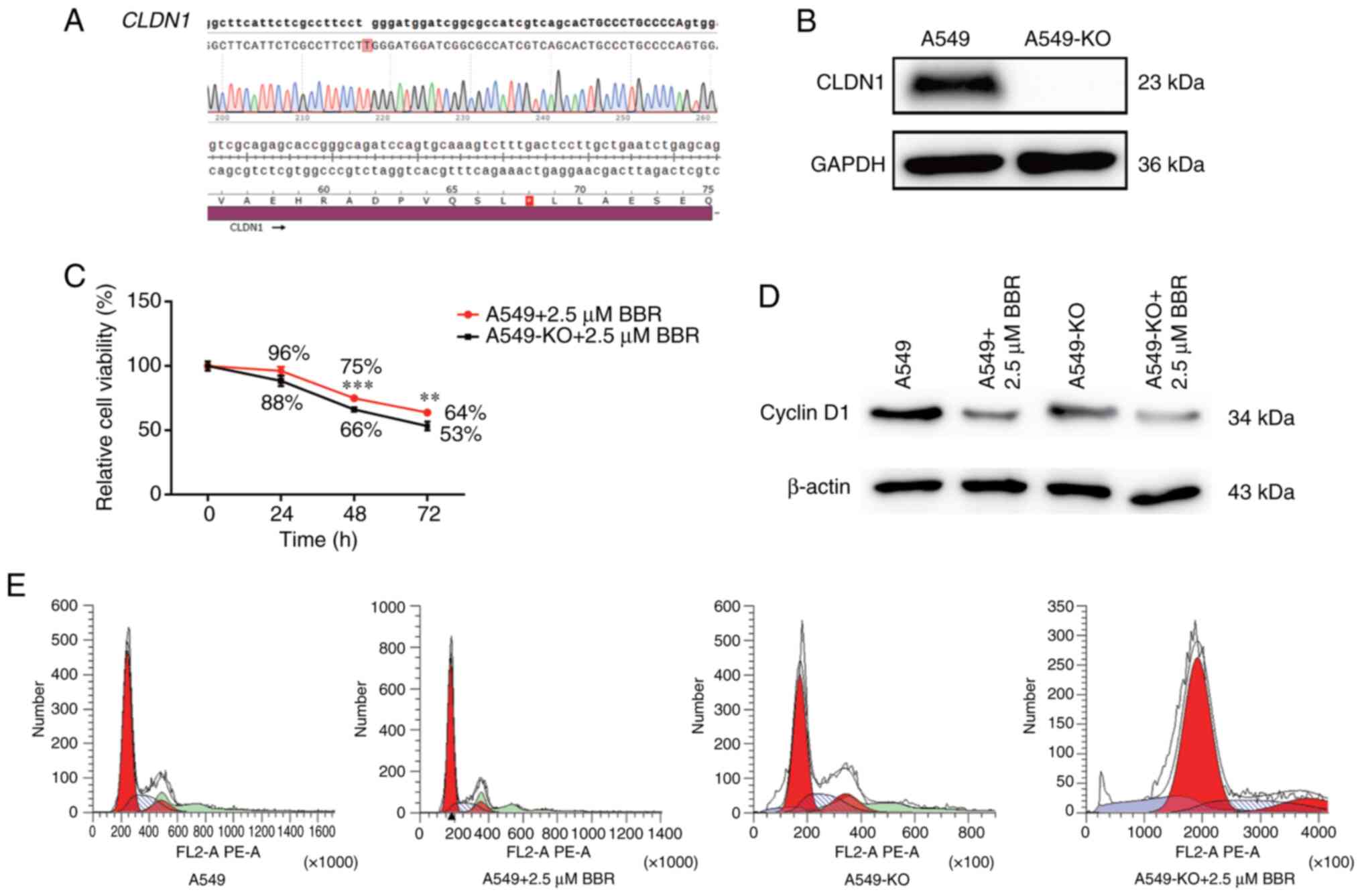

To assess the role of CLDN1 in mediating

response to BBR, two sgRNAs targeting the CLDN1 coding

region (sgRNA-Z9, 5′-AGCGAGTCATGGCCAACGCG-3′; sgRNA-Z10,

5′-GGCGCCGATCCATCCCAGGA-3′) were designed, and

CLDN1-knockout A549 cells were established via lentiviral

transduction. Sanger sequencing confirmed a single-nucleotide

insertion at the Z10 target site, introducing a premature stop

codon at amino acid position 68 (Fig.

4A). Additionally, western blot analysis demonstrated the

complete absence of CLDN1 protein expression in knockout cells

(A549-KO cells; Fig. 4B).

Furthermore, A549-KO cell treatment with BBR significantly reduced

cell viability compared with that in wildtype A549 cells, with

notable differences observed at 48 and 72 h, thus supporting the

dose- and time-dependent sensitization effects of BBR (Fig. 4C). Additionally, flow cytometry

revealed a marked reduction in the S-phase population and a

concomitant increase in the G1-phase population in A549-KO cells

following BBR treatment, indicative of G1-phase cell cycle arrest

(Fig. 4E). Consistent with the

aforementioned findings, cyclin D1, a key regulator of G1/S

transition (51), was notably

downregulated in BBR-treated A549-KO cells compared with that in

wild-type cells (Fig. 4D). These

results indicate that CLDN1 could be involved in BBR-induced

cell cycle arrest and growth suppression in A549 cells.

Discussion

Lung cancer, accounting for ~1.8 million new cases

and ~1.6 million deaths annually, remains a global health challenge

due to its low 5-year survival rate, ranging from 4–17% depending

on the stage of diagnosis and geographical region (52,53).

Despite advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapies

and immunotherapies, drug resistance still poses a critical

barrier, notably limiting long-term efficacy (54). In this context, TCM offers a

promising complementary approach, owning to its multi-target and

multi-component characteristics. Among TCM-derived compounds, BBR

has shown potent anticancer properties via modulating key cellular

processes, such as proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy and immune

modulation within the tumor microenvironment (55). However, the particular molecular

targets and pathways underlying its anticancer effects remain

insufficiently characterized.

The identification of molecular targets of bioactive

compounds is essential for the modernization of TCM and the

development of novel cancer therapeutics (9,11).

Although label-based approaches, such as chemical probe-assisted

affinity capture, have successfully identified key targets, their

application is limited due to chemical modification-induced

activity loss and structural constraints (56,57).

By contrast, label-free methods such as DARTS, cellular thermal

shift assay and thermal proteome profiling offer non-invasive

alternatives. However, their use is commonly hindered by limited

sensitivity to weak or low-abundance protein interactions (14,15,17,58).

These limitations highlight the urgent need for scalable and

precise strategies to enable systematic target identification.

In the present study, a CRISPR/Cas9 genome-wide

knockout library was constructed in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells

to systematically investigate the molecular targets and resistance

mechanisms associated with BBR treatment. The unbiased screening

identified a total of 3,873 genes with differential selection under

BBR exposure, including 749 positive-selection genes associated

with resistance and 3,124 negative-selection genes essential for

cellular viability. Among the resistance-related genes, CLDN1, a

tight junction protein of the CLDN family, could serve as a pivotal

mediator of BBR resistance. In a previous study, CLDN1

overexpression was associated with poor prognosis and resistance to

cisplatin in patients with lung cancer (50). Consistently, the results of the

present study demonstrated that CLDN1 knockout enhanced the

sensitivity of A549 cells to BBR, characterized by reduced cell

proliferation, decreased S-phase entry and G1-phase arrest. The

CRISPR-based identification of CLDN1 as a mediator of the

anticancer effects of BBR aligned with broader advances in CRISPR

therapeutic strategies. Previous comprehensive reviews summarized

the potential of CRISPR in targeting oncogenes, precise gene

modulation and overcoming drug resistance (59). Notably, an in vivo study

reported that CRISPR-lipid nanoparticle platforms could eliminate

≤50% of tumors in mouse models (60). Furthermore, BBR could inhibit tumor

growth in lung cancer models via several pathways, including

epigenetic and DNA-repair modulation (61). Taken together, the results of the

present study could extend current therapeutic paradigms by

positioning CLDN1 as a critical regulator of BBR

responsiveness. Notably, the functional assays in the present study

were performed at 2.5 µM BBR, slightly below the IC50

value (2.856 µM), thus ensuring that the observed differences were

due to genetic manipulation rather than cytotoxicity. However,

future studies are needed to refine this analysis using a

concentration gradient (such as 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0 µM) to further

validate the robustness of the findings. Nevertheless, the results

strongly suggest that CLDN1 could serve a key role in

mediating resistance to BBR via modulating cell cycle

progression.

Beyond CLDN1, other CLDN family members have

also been involved in cancer progression and therapeutic targeting.

For example, a study reported that CLDN4 could act as a

molecular target in epithelial cancers, thus being involved in

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and YAP-mediated

proliferation, with ongoing preclinical efforts exploring

CLDN4-directed antibody therapies (62). Additionally, CLDN18.2 could serve as

a clinically actionable target in gastric and pancreatic cancers,

with monoclonal antibody approaches, such as zolbetuximab,

demonstrating promising antitumor activity (63). Collectively, these findings could

frame CLDN1 within a broader CLDN-triggered regulatory

network and highlight the potential of multi-CLDN targeting

approaches in cancer therapy.

Beyond its role in cell cycle regulation,

CLDN1 has also been involved in additional signaling

pathways associated with cancer biology. A previous study reported

that CLDN1 overexpression could activate the TGF-β1/EMT

signaling pathway, thus mitigating the sensitivity of lung cancer

cells to doxorubicin (64). These

findings indicated that CLDN1 could act as a multifunctional

regulator linking junctional integrity to oncogenic signaling.

Whilst the present study primarily established CLDN1 as a

mediator of BBR sensitivity, future research is needed to further

investigate EMT- and TGF-β1-associated mechanisms downstream of

CLDN1 to provide a more comprehensive mechanistic framework.

Notably, the identification of CLDN1 as a BBR-resistance

gene underscored the broader utility of the current CRISPR/Cas9

screening platform. Compared with conventional methods, this

genome-wide approach could enable unbiased and high-throughput

target identification, thus providing a powerful framework for

elucidating the molecular mechanisms of TCM-derived compounds. The

discovery of CLDN1 could not only deepen the understanding

of the pharmacological effects of BBR, but also highlight its

potential as a therapeutic target for overcoming drug resistance in

lung cancer.

Moving forward, the development of specific

CLDN1 inhibitors could provide novel opportunities for

combination therapies, enhancing the efficacy of BBR and that of

other anticancer agents. In addition, the present study established

a proof-of-concept for applying CRISPR-based screening in TCM

research, thus offering novel insights into the systematic

exploration of bioactive compounds and their molecular targets.

This integrative approach could not only support the modernization

and global acceptance of TCM, but it could be also involved into

the broader advancement of precision oncology.

While the present study successfully identified

CLDN1 as a pivotal mediator of berberine (BBR) resistance

through a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening in A549 cells, several

aspects merit further investigation. The findings were derived from

a single lung adenocarcinoma model, and validation in additional

lung cancer subtypes or in vivo systems would strengthen the

generalizability of the results. Moreover, this study focused on

gene-level knockout screening; integration with transcriptomic or

proteomic data could provide a broader mechanistic perspective on

the BBR-CLDN1 network. In addition, although a sub-IC50

concentration of BBR was used to highlight genetic effects rather

than cytotoxicity, evaluation across a concentration gradient would

better characterize dose-dependent responses. Addressing these

aspects in future work will refine the mechanistic insights and

enhance the translational relevance of the findings.

In conclusion, the present study identifies

CLDN1 as a critical determinant of berberine responsiveness

in lung cancer cells and establishes a CRISPR/Cas9-based framework

for target discovery in traditional Chinese medicine. These

findings provide mechanistic insight into BBR resistance and offer

a promising direction for the development of CLDN1-targeted

combination therapies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation

of Chongqing-Postdoctoral Science Foundation Project (grant nos.

cstc2021jcyj-bshX0016 and cstc2021jcyj-bshX0034), Chongqing

Scientific Research Institutions Performance Incentive and Guidance

Project (grant nos. cstc2023jxjl-jbky130009, zzkjjh2022012,

zzkjjh2022013 and CSTB2023TIAD-KPX0101) and the Project of Basic

Scientific Research Plan of Chongqing (grant nos. jbky20210030 and

jbky20200008).

Availability of data and materials

The NGS data generated in the present study may be

found in the NCBI BioProject database under accession number

PRJNA1345357 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1345357.

All other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XGW and XT contributed to the design of CRISPR/Cas9

screening strategies. YDW contributed to the design and

optimization of the functional validation experiments following the

primary CRISPR/Cas9 screen. XGW, BZM and YDW were involved in the

literature search and review. XJW, BZM, YJX and FL performed the

experiments. JFL and JYH performed the data analysis. BZM and YDW

provided key reagents, cell lines and instrumental resources. XGW,

YJX and YDZ wrote the manuscript. YDZ conceived and coordinated the

study, integrated the overall data analysis and manuscript

preparation, and was responsible for communication and revision

with the journal, with YDW assisting in correspondence and resource

support. XGW and YDZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BBR

|

berberine

|

|

CLDN1

|

claudin-1

|

|

CRISPR

|

clustered regularly interspaced short

palindromic repeats

|

|

DARTS

|

drug affinity responsive target

stability

|

|

sgRNA

|

single-guide RNA

|

|

KO

|

knockout

|

|

TCM

|

traditional Chinese medicine

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

|

|

2

|

Phillips I, Stares M, Allan L, Sayers J,

Skipworth R and Laird B: Optimising outcomes in non small cell lung

cancer: Targeting cancer cachexia. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed).

27:1292022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Su PL, Furuya N, Asrar A, Rolfo C, Li Z,

Carbone DP and He K: Recent advances in therapeutic strategies for

non-small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 18:352025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Riely GJ, Wood DE, Ettinger DS, Aisner DL,

Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, et

al: Non-small cell lung cancer, version 4.2024, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:249–274. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wang JL, Qiu TY and Ren SX: Updates to the

2024 CSCO advanced non-small cell lung cancer guidelines. Cancer

Biol Med. 22:77–82. 2025.

|

|

6

|

Huang Q, Li Y, Huang Y, Wu J, Bao W, Xue

C, Li X, Dong S, Dong Z and Hu S: Advances in molecular pathology

and therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Tar.

10:1862025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Li S, Chen X, Shi H, Yi M, Xiong B and Li

T: Tailoring traditional Chinese medicine in cancer therapy. Mol

Cancer. 24:272025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chen JF, Wu SW, Shi ZM and Hu B:

Traditional Chinese medicine for colorectal cancer treatment:

potential targets and mechanisms of action. Chin Med. 18:142023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Paolini GV, Shapland RH, van Hoorn WP,

Mason JS and Hopkins AL: Global mapping of pharmacological space.

Nat Biotechnol. 24:805–815. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Mohamad Zobir SZ, Mohd Fauzi F, Liggi S,

Drakakis G, Fu X, Fan TP and Bender A: Global Mapping of

Traditional Chinese Medicine into Bioactivity Space and Pathways

Annotation Improves Mechanistic Understanding and Discovers

Relationships between Therapeutic Action (Sub)classes. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2016:21064652016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang J, Wong YK and Liao F: What has

traditional Chinese medicine delivered for modern medicine? Expert

Rev Mol Med. 20:e42018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Koshelev YA: Affinity chromatography and

proteomic screening as the effective method for S100A4 new protein

targets discovery. Mol Biol (Mosk). 48:868–872. 2014.(In Russian).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Niphakis MJ and Cravatt BF: Enzyme

inhibitor discovery by activity-based protein profiling. Annu Rev

Biochem. 83:341–377. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lomenick B, Hao R, Jonai N, Chin RM,

Aghajan M, Warburton S, Wang J, Wu RP, Gomez F, Loo JA, et al:

Target identification using drug affinity responsive target

stability (DARTS). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:21984–21989. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Dearmond PD, Xu Y, Strickland EC, Daniels

KG and Fitzgerald MC: Thermodynamic analysis of protein-ligand

interactions in complex biological mixtures using a shotgun

proteomics approach. J Proteome Res. 10:4948–4958. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Martinez Molina D, Jafari R,

Ignatushchenko M, Seki T, Larsson EA, Dan C, Sreekumar L, Cao Y and

Nordlund P: Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues

using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science. 341:84–87. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Savitski MM, Reinhard FB, Franken H,

Werner T, Savitski MF, Eberhard D, Martinez Molina D, Jafari R,

Dovega RB, Klaeger S, et al: Tracking cancer drugs in living cells

by thermal profiling of the proteome. Science. 346:12557842014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nabet B, Roberts JM, Buckley DL, Paulk J,

Dastjerdi S, Yang A, Leggett AL, Erb MA, Lawlor MA, Souza A, et al:

The dTAG system for immediate and target-specific protein

degradation. Nat Chem Biol. 14:431–441. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wittrup A, Ai A, Liu X, Hamar P, Trifonova

R, Charisse K, Manoharan M, Kirchhausen T and Lieberman J:

Visualizing Lipid-formulated siRNA release from endosomes and

target gene knockdown. Nat Biotechnol. 33:870–876. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Schirle M, Bantscheff M and Kuster B: Mass

Spectrometry-based proteomics in preclinical drug discovery. Chem

Biol. 19:72–84. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Koike-Yusa H, Li Y, Tan EP,

Velasco-Herrera Mdel C and Yusa K: Genome-wide recessive genetic

screening in mammalian cells with a lentiviral CRISPR-guide RNA

library. Nat Biotechnol. 32:267–273. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hou P, Wu C, Wang Y, Qi R, Bhavanasi D,

Zuo Z, Dos Santos C, Chen S, Chen Y, Zheng H, et al: A Genome-Wide

CRISPR screen identifies genes critical for resistance to FLT3

inhibitor AC220. Cancer Res. 77:4402–4413. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Song CQ, Li Y, Mou H, Moore J, Park A,

Pomyen Y, Hough S, Kennedy Z, Fischer A, Yin H, et al: Genome-Wide

CRISPR screen identifies regulators of Mitogen-activated protein

kinase as suppressors of liver tumors in mice. Gastroenterology.

152:1161–1173.e1. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Parnas O, Jovanovic M, Eisenhaure TM,

Herbst RH, Dixit A, Ye CJ, Przybylski D, Platt RJ, Tirosh I,

Sanjana NE, et al: A Genome-wide CRISPR screen in primary immune

cells to dissect regulatory networks. Cell. 162:675–686. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Patel SJ, Sanjana NE, Kishton RJ,

Eidizadeh A, Vodnala SK, Cam M, Gartner JJ, Jia L, Steinberg SM,

Yamamoto TN, et al: Identification of essential genes for cancer

immunotherapy. Nature. 548:537–542. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kurata M, Yamamoto K, Moriarity BS,

Kitagawa M and Largaespada DA: CRISPR/Cas9 library screening for

drug target discovery. J Hum Genet. 63:179–186. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kwon JW, Oh JS, Seok SH, An HW, Lee YJ,

Lee NY, Ha T, Kim HA, Yoon GM, Kim SE, et al: Combined inhibition

of Bcl-2 family members and YAP induces synthetic lethality in

metastatic gastric cancer with RASA1 and NF2 deficiency. Mol

Cancer. 22:1562023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Och A, Podgorski R and Nowak R: Biological

activity of Berberine-A summary update. Toxins (Basel). 12:7132020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Habtemariam S: Recent advances in

berberine inspired anticancer approaches: From drug combination to

novel formulation technology and derivatization. Molecules.

25:14262020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Samadi P, Sarvarian P, Gholipour E,

Asenjan KS, Aghebati-Maleki L, Motavalli R, Hojjat-Farsangi M and

Yousefi M: Berberine: A novel therapeutic strategy for cancer.

IUBMB Life. 72:2065–2079. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Paudel KR, Mehta M, Yin GHS, Yen LL,

Malyla V, Patel VK, Panneerselvam J, Madheswaran T, MacLoughlin R,

Jha NK, et al: Berberine-loaded liquid crystalline nanoparticles

inhibit non-small cell lung cancer proliferation and migration in

vitro. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 29:46830–46847. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Li Q, Zhao H, Chen W and Huang P:

Berberine induces apoptosis and arrests the cell cycle in multiple

cancer cell lines. Arch Med Sci. 19:1530–1537. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Shen F, Zheng YS, Dong L, Cao Z and Cao J:

Enhanced tumor suppression in colorectal cancer via

berberine-loaded PEG-PLGA nanoparticles. Front Pharmacol.

15:15007312024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sun L, Lan J, Li Z, Zeng R, Shen Y, Zhang

T and Ding Y: Transforming cancer treatment with nanotechnology:

The role of berberine as a star natural compound. Int J

Nanomedicine. 19:8621–8640. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Haque S, Mathkor DM, Bhat SA, Musayev A,

Khituova L, Ramniwas S, Phillips E, Swamy N, Kumar S, Yerer MB, et

al: A comprehensive review highlighting the prospects of

phytonutrient berberine as an anticancer agent. J Biochem Mol

Toxicol. 39:e700732025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Shalem O, Sanjana NE and Zhang F:

High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Rev

Genet. 16:299–311. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li W, Xu H, Xiao T, Cong L, Love MI, Zhang

F, Irizarry RA, Liu JS, Brown M and Liu XS: MAGeCK enables robust

identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9

knockout screens. Genome Biol. 15:5542014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Estoppey D, Schutzius G, Kolter C, Salathe

A, Wunderlin T, Meyer A, Nigsch F, Bouwmeester T, Hoepfner D and

Kirkland S: Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screens identify mechanisms of

BET bromodomain inhibitor sensitivity. Iscience. 24:1033232021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhao Y, Wei L, Tagmount A, Loguinov A,

Sobh A, Hubbard A, McHale CM, Chang CJ, Vulpe CD and Zhang L:

Applying genome-wide CRISPR to identify known and novel genes and

pathways that modulate formaldehyde toxicity. Chemosphere.

269:1287012021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yan YQ, Fu YJ, Wu S, Qin HQ, Zhen X, Song

BM, Weng YS, Wang PC, Chen XY and Jiang ZY: Anti-influenza activity

of berberine improves prognosis by reducing viral replication in

mice. Phytother Res. 32:2560–2567. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kalaiarasi A, Anusha C, Sankar R,

Rajasekaran S, John Marshal J, Muthusamy K and Ravikumar V: Plant

isoquinoline alkaloid berberine exhibits chromatin remodeling by

modulation of histone deacetylase to induce growth arrest and

apoptosis in the A549 cell line. J Agric Food Chem. 64:9542–9550.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Qi HW, Xin LY, Xu X, Ji XX and Fan LH:

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers to predict response of

Berberine in suppressing lung cancer invasion and metastasis. J

Transl Med. 12:222014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zheng F, Wu J, Tang Q, Xiao Q, Wu W and

Hann SS: The enhancement of combination of berberine and metformin

in inhibition of DNMT1 gene expression through interplay of SP1 and

PDPK1. J Cell Mol Med. 22:600–612. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen QQ, Shi JM, Ding Z, Xia Q, Zheng TS,

Ren YB, Li M and Fan LH: Berberine induces apoptosis in

non-small-cell lung cancer cells by upregulating miR-19a targeting

tissue factor. Cancer Manag Res. 11:9005–9015. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kumar R, Awasthi M, Sharma A, Padwad Y and

Sharma R: Berberine induces dose-dependent quiescence and apoptosis

in A549 cancer cells by modulating cell cyclins and inflammation

independent of mTOR pathway. Life Sci. 244:1173462020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Pope JL, Bhat AA, Sharma A, Ahmad R,

Krishnan M, Washington MK, Beauchamp RD, Singh AB and Dhawan P:

Claudin-1 regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis through the

modulation of Notch-signalling. Gut. 63:622–634. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Singh AB, Uppada SB and Dhawan P: Claudin

proteins, outside-in signaling, and carcinogenesis. Pflugers Arch.

469:69–75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Turksen K: Claudins and cancer stem cells.

Stem Cell Rev Rep. 7:797–798. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Zhou B, Flodby P, Luo J, Castillo DR, Liu

Y, Yu FX, McConnell A, Varghese B, Li G, Chimge NO, et al:

Claudin-18-mediated YAP activity regulates lung stem and progenitor

cell homeostasis and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 128:970–984.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Zhao Z, Li J, Jiang Y, Xu W, Li X and Jing

W: CLDN1 increases drug resistance of Non-small cell lung cancer by

activating autophagy via Up-regulation of ULK1 phosphorylation. Med

Sci Monit. 23:2906–2916. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Cai W, Shu LZ, Liu DJ, Zhou L, Wang MM and

Deng H: Targeting cyclin D1 as a therapeutic approach for papillary

thyroid carcinoma. Front Oncol. 13:11450822023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

O'Kane GM and Leighl NB: Are immune

checkpoint blockade monoclonal antibodies active against CNS

metastases from NSCLC?-current evidence and future perspectives.

Transl Lung Cancer Res. 5:628–636. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Economopoulou P and Mountzios G: Non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and central nervous system (CNS)

metastases: Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and evidence

in favor or against their use with concurrent cranial radiotherapy.

Transl Lung Cancer Res. 5:588–598. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Lin JJ and Shaw AT: Resisting resistance:

Targeted therapies in lung cancer. Trends Cancer. 2:350–364. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wang Y, Liu Y, Du X, Ma H and Yao J: The

Anti-cancer mechanisms of berberine: A review. Cancer Manag Res.

12:695–702. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Liao LX, Song XM, Wang LC, Lv HN, Chen JF,

Liu D, Fu G, Zhao MB, Jiang Y, Zeng KW and Tu PF: Highly selective

inhibition of IMPDH2 provides the basis of antineuroinflammation

therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E5986–E5994. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Luo P, Zhang Q, Zhong TY, Chen JY, Zhang

JZ, Tian Y, Zheng LH, Yang F, Dai LY, Zou C, et al: Celastrol

mitigates inflammation in sepsis by inhibiting the PKM2-dependent

Warburg effect. Mil Med Res. 9:222022.

|

|

58

|

Reinhard FB, Eberhard D, Werner T, Franken

H, Childs D, Doce C, Savitski MF, Huber W, Bantscheff M, Savitski

MM and Drewes G: Thermal proteome profiling monitors ligand

interactions with cellular membrane proteins. Nat Methods.

12:1129–1131. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Chehelgerdi M, Chehelgerdi M,

Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi M, Shafieizadeh M, Mahmoudi E, Eskandari F,

Rashidi M, Arshi A and Mokhtari-Farsani A: Comprehensive review of

CRISPR-based gene editing: Mechanisms, challenges, and applications

in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 23:92024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Masarwy R, Breier D, Stotsky-Oterin L,

Ad-El N, Qassem S, Naidu GS, Aitha A, Ezra A, Goldsmith M,

Hazan-Halevy I and Peer D: Targeted CRISPR/Cas9 lipid nanoparticles

elicits therapeutic genome editing in head and neck cancer. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24110322025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Xu X, He Y and Liu J: Berberine: A

multifaceted agent for lung cancer treatment-from molecular insight

to clinical applications. Gene. 934:1490212025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Fujiwara-Tani R, Mori S, Ogata R, Sasaki

R, Ikemoto A, Kishi S, Kondoh M and Kuniyasu H: Claudin-4: A new

molecular target for epithelial cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

24:54942023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Tojjari A, Idrissi YA and Saeed A:

Emerging targets in gastric and pancreatic cancer: Focus on claudin

18.2. Cancer Lett. 611:2173622024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Nagaoka Y, Oshiro K, Yoshino Y, Matsunaga

T, Endo S and Ikari A: Activation of the TGF-beta1/EMT signaling

pathway by claudin-1 overexpression reduces doxorubicin sensitivity

in small cell lung cancer SBC-3 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys.

751:1098242024. View Article : Google Scholar

|