Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the primary cause

of mortality from gynecological malignancies and the sixth most

common cause of cancer-related fatalities overall in the Western

world. Women face a 1 in 70 to 80 a lifetime risk of developing EOC

and a chance of 1 in 90 to 100 of succumbing to this illness

(1). Currently, estimates indicate

that ~90% of these neoplasms originate from the ovary, while 5–7%

originate from the fallopian tubes. Non-epithelial ovarian tumors,

developed from stromal or germ cell neoplasms, make up the

remaining 3–5% (2). Ovarian cancer

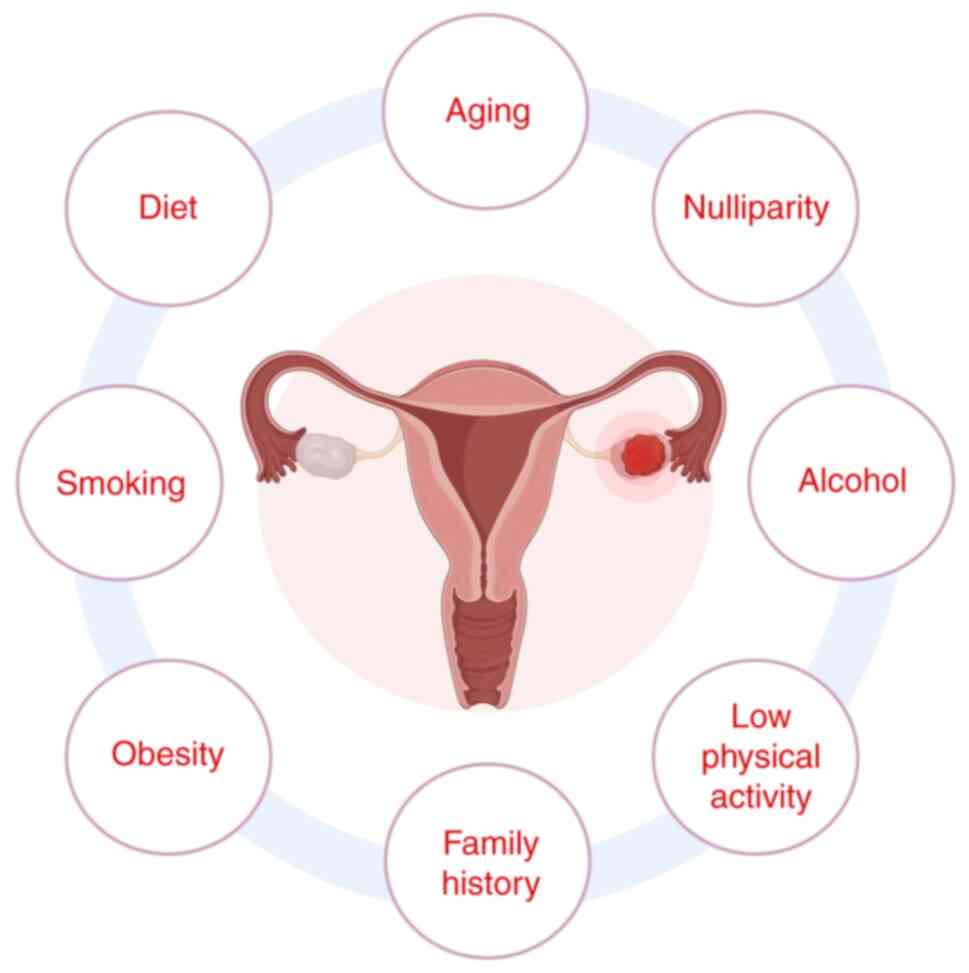

is a complex illness shaped by genetic, hormonal and environmental

influences. Principal risk factors encompass BRCA mutations,

nulliparity, early menarche, late menopause, hormone replacement

treatment, obesity and lifestyle choices (1) (Fig.

1). Although several studies indicated that dietary and

environmental exposures may serve a role in illness development,

causal associations remain ambiguous (3–8). The

clinical management of EOC presents considerable hurdles, as the

majority of cases are discovered at an advanced stage, hence

restricting therapy choices. Surgical intervention is fundamental

to therapy, with cytoreductive surgery markedly enhancing survival

rates. However, reconciling oncological results with minimally

invasive techniques (MITs) continues to be a topic of ongoing

research, especially in advanced-stage illness when optimum

cytoreduction is more challenging to attain (9). Innovations in surgical methodologies

seek to reduce patient stress while maintaining oncological safety;

nonetheless, the long-term advantages of minimally invasive surgery

(MIS) in EOC necessitate further research (10,11).

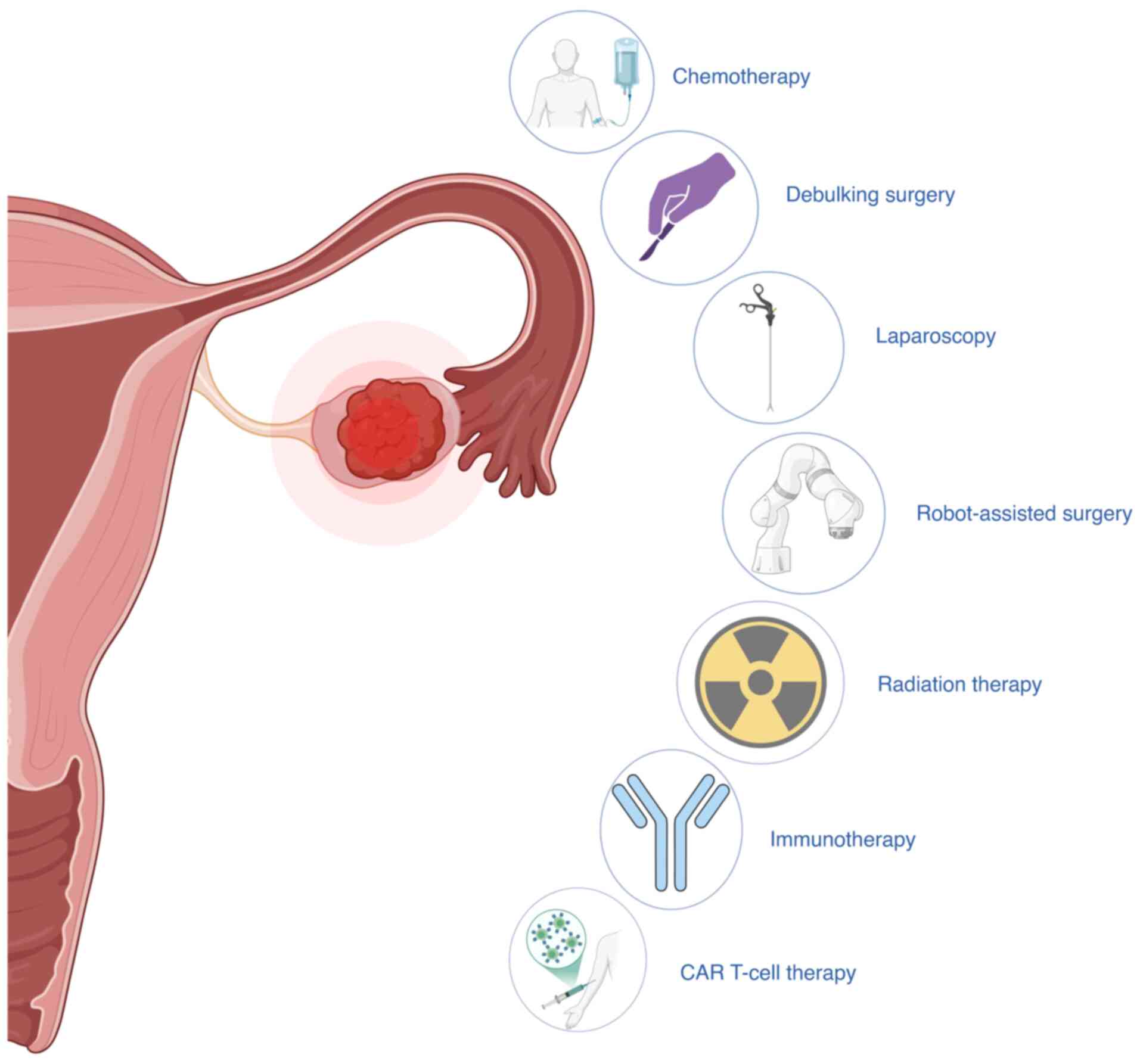

A multimodal approach is used to treat EOC, which

includes surgery and chemotherapy, with the specifics changing

based on the stage of the disease and the type of tissue involved.

The principal intervention is cytoreductive surgery, as achieving a

low residual tumor burden markedly associates with improved

progression-free and overall survival rates. In early-stage cancer,

surgery succeeded by platinum-based chemotherapy yields marked

results, whereas in advanced-stage disease, surgical cytoreduction

in conjunction with systemic treatment is the standard of care

(12,13).

Chemotherapy, primarily with platinum-taxane

regimens, continues to be the cornerstone of systemic treatment

(3,14). Novel targeted medicines, such as

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for BRCA-mutated

cancer types and angiogenesis inhibitors such as bevacizumab, have

broadened treatment alternatives; yet, therapeutic resistance

remains a notable concern (15,16).

Radiotherapy is infrequently employed in cases of EOC outside of

palliative care, given that its toxicity frequently surpasses its

advantages due to the low radiosensitivity of EOC. Current research

seeks to enhance therapy approaches by incorporating innovative

medicines and enhancing patient selection to increase treatment

effectiveness while reducing unwanted effects.

The present review was conducted as a narrative

review, with the aim of synthesizing recent advances in minimally

invasive surgical techniques and their integration with systemic

therapies in the management of EOC. A comprehensive literature

search was performed across the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/) and Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/)

databases. The search focused on English-language peer-reviewed

publications from January 2009 to April 2024. The inclusion

criteria encompassed randomized controlled trials (RCTs),

prospective and retrospective clinical studies, large cohort

analyses, meta-analyses and relevant consensus guidelines

associated with surgical management, systemic therapies and their

integration in EOC. Studies focusing on non-surgical interventions,

preclinical or animal models or other types of gynecological cancer

were excluded. Titles and abstracts of 114 article were screened

and full texts of relevant articles were reviewed to ensure

alignment with the scope of the present review. The Scale for the

Assessment of Narrative Review Articles guidelines were followed to

enhance the methodological rigor and transparency of the present

narrative synthesis (17).

Surgical techniques in minimally invasive

management

The notion of MIS cancer cytoreduction was first

presented through the evaluation of two non-randomized studies that

indicated the non-inferiority of laparoscopy regarding

progression-free survival (PFS). A randomized phase III trial was

subsequently reported, which did not demonstrate non-inferiority in

overall survival for patients who had debulking by the minimally

invasive surgical strategy compared with open surgery (18,19).

Retrospective studies have reported an absence of drawbacks for the

MIS approach in terms of PFS and the finding of decreased

postoperative pain and tolerance to chemotherapy (20–22).

There are differences in study design and execution

between two major prospective randomized phase III trials that

investigated the MIS approach, such as operative duration and

center experience (19). The

different results have been attributed to various factors, such as

the longer duration and bleeding that come with laparoscopy and

that almost all of the participating centers have only performed a

few procedures each year, indicating less experience with the

procedure, which could negatively impact the outcomes. Regarding

the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)

stage IA disease (23), the concept

of keeping the uterus stable during minimal surgical changes makes

the MIS approach more likely to be used. This could facilitate more

straightforward and standardized minimally invasive procedures for

complex surgeries. Further recommendations for patient selection

criteria, standardized surgical protocols and intraoperative safety

measures may emerge from analyses performed by skilled surgical

teams (24).

Laparoscopy

Imaging methods often cannot differentiate between

the different kinds of adnexal masses on their own, when it comes

to functional and benign variants. Accurately predicting the

presence of ovarian cancer and the need for surgery can both be

improved with laparoscopy. This method also helps in making a

correct diagnosis before surgery. Laparoscopy is an improved

technique as it helps reduce the need for individuals to undergo

unnecessary surgery to treat functional and benign ovarian cysts

(25,26). A histology examination of the tumor

and its implants typically offer additional diagnostic insights,

along with information regarding the stage of disease. Laparoscopy

facilitates the sampling of purulent peritoneal effusion for

culture testing, which aids in the identification of any

accompanying infection and in determining the appropriate surgical

approach (20).

In the context of malignant diseases, prioritizing

the complete removal of the primary tumor is key in ovarian cancer

as well. The primary objective of oncologists and gynecologists is

to ensure the safety of the patient; therefore, it is essential to

maintain a pathway for the potential conversion of laparoscopy to

laparotomy at any given time. Furthermore, depending on the

experience of the surgical oncologist, MITs such as laparoscopy can

provide patients with adnexal masses of unclear origin the same

diagnostic and therapeutic surgical staging benefits as laparotomy

(21). Furthermore, the prevention

of notable surgical procedures and complications can lead to a more

efficient recovery process for the patient. These factors enhance

the quality of life (QoL) and potentially the self-esteem of

patients while reducing their costs (21,27,28).

Robot-assisted surgery

In EOC surgery, the robotic system enhances

precision and dexterity of the surgeon, enabling fine dissection

and removal of primary tumors, targeted omentectomy and systematic

lymphadenectomy through small ports with three-dimensional

magnified visualization (29).

Robotic-assisted surgery is particularly crucial for patients with

cardiovascular, hepatic, renal or pulmonary comorbidities, as it

minimizes physiological stress by reducing intraoperative blood

loss, shortening operative time and maintaining stable

intra-abdominal pressures, thereby lowering cardiopulmonary

complication rates. In women aged 18–40 years who desire fertility

preservation, combining laparoscopy with robotic precision enables

accurate tumor resection, targeted omentectomy and unilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy while sparing the contralateral ovary

(29). Multiple retrospective

series have demonstrated that robotic cytoreduction reduces

hospital stays to an average of 2–3 days and decreases 90-day

morbidity compared with open surgery, driving its increasing

adoption among gynecological oncologists (21,28,30,31).

A 2-year retrospective observational study was

conducted, analyzing data on women diagnosed with ovarian cancer

and compared outcomes according to their surgical methods (29,30).

Robot-assisted surgery enables precise pelvic and para-aortic

lymphadenectomy, including dissection of nodal stations enriched

with hematopoietic progenitor cell niches, thereby improving

staging accuracy while minimizing collateral tissue trauma. This

allows the provision of gonadotoxic treatments to these patients,

which protects their ability to have children. The robot-assisted

surgical approach has been employed to perform systematic pelvic

and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, enabling accurate staging of

ovarian cancer and facilitating evaluation of the therapeutic

impact of varying lymph node harvests (31). Robotic surgery methods may help

identify high-risk patients who can have a full lymphadenectomy and

still receive fertility-preserving treatment. The growing adoption

of MITs in ovarian cancer surgery highlights various benefits,

including enhanced patient satisfaction and potential cost savings

associated with these approaches.

Molecular-based therapies in conjunction

with MITs

The clinical management of ovarian carcinoma poses

significant challenges for oncology professionals due to the

typically late-stage presentation of the disease, the high

propensity for peritoneal dissemination and the complexity in

achieving complete cytoreduction. According to the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for ovarian cancer, optimal

management of advanced-stage EOC requires maximal cytoreductive

surgery, preferably achieving no macroscopic residual disease,

followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, with

consideration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and interval

debulking in selected patients. Minimally invasive surgical

techniques in EOC allow optimal cytoreduction with outcomes

comparable to open surgery, while significantly reducing

perioperative morbidity and accelerating recovery. This faster

recovery enables earlier initiation of adjuvant therapy, so

patients can promptly receive novel systemic treatments that

improve disease control (27). This

faster recovery enables earlier initiation of adjuvant therapy, so

patients can promptly receive novel systemic treatments that

improve disease control (32).

Additionally, integrating immunotherapy (for example, checkpoint

inhibitors) is an emerging strategy, combination approaches, such

as a PARP inhibitor plus programmed cell death protein (PD)-1

blockade, have demonstrated higher response rates in refractory

ovarian cancer compared with either modality alone (33). In current practice, the combination

of MIS and these targeted therapies translates into improved

clinical outcomes: Patients experience shorter hospital stays,

improved treatment responses and extended remissions, which

demonstrate that surgical innovation complements systemic advances

without compromising oncological efficacy (32).

In EOC, combining MIS with novel systemic therapies

(PARP inhibitors or anti-angiogenic agents such as bevacizumab and

emerging immunotherapies) is shaping a more effective, multimodal

treatment paradigm. MIS (for example, laparoscopic or robotic

debulking) offers well-documented perioperative advantages over

open surgery, including shorter hospital stays, reduced blood loss

and fewer complications, which translate into faster recovery and

allows patients to proceed more swiftly to adjuvant systemic

therapy. This expedited post-surgery recovery means maintenance

treatments such as PARP inhibitor therapy or anti-angiogenic agents

can be initiated without undue delay, which maximizes their impact

(21,27,32,34,35).

By contrast, systemic therapies can shrink or control tumor burden

(for instance, NACT is often combined with bevacizumab in trials),

which thereby increases the likelihood that a subsequent

cytoreduction can be successfully performed via MIS. This

bidirectional synergy ensures each modality enhances the other:

Effective preoperative systemic therapy can render disease more

resectable for minimally invasive surgeons, while the lower

surgical morbidity of MIS preserves patient performance status for

the continuation of systemic treatments (27,36).

Clinical studies and outcomes underscore the value of this

integrated approach. The ongoing phase III Laparoscopic

Cytoreduction After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (LANCE) trial is

directly evaluating MIS vs. open laparotomy after NACT in advanced

EOC, reflecting the effort to confirm that a less invasive surgical

approach can achieve equivalent oncological outcomes (32,35)(Fig.

2).

The benefit of coupling surgery with targeted

post-operative therapy has also been reported, for example, in the

PAOLA-1 trial, patients who received standard surgery and

chemotherapy followed by maintenance olaparib (a PARP inhibitor)

plus bevacizumab had markedly prolonged PFS (22.1 months vs. 16.6

months with bevacizumab alone). This finding led to regulatory

approval of the olaparib-bevacizumab combination and illustrates

how surgery complemented by novel agents can improve patient

outcomes (35). Immunotherapy is

also being explored in combination with these modalities; although

checkpoint inhibitors alone have demonstrated limited efficacy in

EOC, integrating them with other treatments may unlock synergistic

effects. Preclinical evidence suggested that debulking surgery can

enhance the impact of immunotherapy by reducing immunosuppressive

tumor burden (for example, decreasing myeloid suppressor cells and

improving T-cell trafficking) (36)

and early-phase studies indicated that PARP inhibitors combined

with PD-1/PD-ligand 1 (L1) checkpoint blockade yield additive

antitumor activity in ovarian cancer (37). Clinical guidelines now advocate an

integrated, individualized approach to EOC management. The National

Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends offering minimally invasive

surgery for surgical staging in early-stage disease (FIGO I–IIA) or

for interval cytoreduction following neoadjuvant platinum-taxane

chemotherapy when key criteria are met: i) Disease confined to the

pelvis or superficial peritoneum without extensive diaphragmatic,

mesenteric, hepatic or splenic involvement; ii) at least a 50%

reduction in tumor volume on imaging to facilitate complete gross

resection via laparoscopy or robotics; iii) confirmation by

preoperative imaging or diagnostic laparoscopy that R0

cytoreduction is achievable without multiorgan resections; and iv)

patient performance status of ECOG 0–1 with well-controlled

comorbidities and anatomy suitable for minimally invasive access

(38,39). Concurrently, American Society of

Clinical Oncology/European Society for Medical Oncology consensus

guidelines endorse maintenance targeted therapy in patients with

advanced (FIGO III–IV) ovarian cancer who respond to first-line

platinum-taxane chemotherapy, specifying olaparib maintenance in

BRCA-mutated patients based on SOLO-1, niraparib maintenance in

BRCA wild-type or homologous recombination deficiency

(HRD)-positive patients per PRIMA, and the combination of olaparib

plus bevacizumab maintenance in HRD-positive cases according to

PAOLA-1 (27,35,40–42).

Together, these strategies create a cohesive treatment plan:

Maximal tumor reduction through surgery (increasingly via MIS to

minimize patient burden) followed by tailored systemic therapy to

eradicate microscopic disease and suppress recurrence. This

holistic approach has a compounding positive effect on patient

outcomes, which yields longer remissions and potentially improved

survival, while also improving QoL by reducing surgical trauma and

leveraging more precise, effective medications (27,32,35).

In summary, MIS and novel systemic therapies are not competing

alternatives but complementary approaches in the treatment of

ovarian cancer, as each reinforces the efficacy of the other, which

results in a synergistic improvement in clinical results for

patients with EOC.

Targeted therapies

Targeted therapies are fundamental in ovarian cancer

management as they are designed to interfere with specific

molecular pathways that cancer cells rely on for growth, survival

and proliferation, distinguishing them from traditional

chemotherapy agents such as carboplatin, paclitaxel and

doxorubicin, which broadly target all rapidly dividing cells.

Unlike conventional chemotherapy, which causes damage to both

malignant and normal cells leading to significant side effects such

as neutropenia, alopecia, mucositis and fatigue, targeted therapies

such as PARP inhibitors (including olaparib and rucaparib),

anti-angiogenic agents (including bevacizumab) and folate receptor

α inhibitors (including mirvetuximab), specifically attack pathways

activated only in cancer cells, resulting in fewer off-target

effects. These therapies work by inducing apoptosis through

disruption of cancer-specific signaling pathways, including

homologous recombination repair pathways and tumor angiogenesis

processes, which suppress tumor growth and promote cancer cell

death. Furthermore, predictive biomarkers such as BRCA mutations

and HRD status enable clinicians to identify patients who are most

likely to benefit from these targeted treatments, providing a

personalized approach that enhances efficacy (35,43–45).

Nonetheless, the emergence of drug resistance

presents a notable limitation. A potentially more effective

strategy may involve a combination therapy utilizing ≥2 targeted

agents or integrating chemotherapy with hormone therapy alongside a

targeted agent to enhance sensitivities (46). The foundation of these approaches

relies on current understanding of the molecular pathways that

serve a role in the development and progression of cancer. In the

past decade, research on EOC has highlighted mutations or

amplifications in specific genes that indicate the involvement of

pathways associated with DNA damage repair, apoptosis, cell cycle

control and anti-angiogenesis. The present review underscores the

necessity for innovative pharmaceuticals and the initiation of

clinical trials to explore therapeutic alternatives.

PARP inhibitors

In recent years, PARP inhibitors have emerged as a

prominent class of targeted therapies in EOC (32,33,47).

These agents act by disrupting the DNA repair process,

specifically, the repair of single-strand DNA breaks. When PARP is

inhibited, these breaks evolve into double-strand DNA damage, which

cannot be effectively repaired in cancer cells harboring BRCA1/2

mutations, which leads to cell death via synthetic lethality

(37,46,48).

Currently, three PARP inhibitors, olaparib, rucaparib and

niraparib, are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for

ovarian cancer treatment, based on a number of pivotal trials

(40,41,49).

For instance, the SOLO-1 trial demonstrated a

notable increase in PFS from 13.8 to 56 months in newly diagnosed

patients with BRCA-mutated EOC receiving olaparib as maintenance

therapy [Hazard ratio (HR), 0.30; P<0.001] (40). The PRIMA trial extended this benefit

to a broader population, which demonstrated improved PFS from 8.2

to 13.8 months with niraparib in both BRCA and non-BRCA advanced

cases (HR, 0.62; P<0.001) (41).

In recurrent BRCA-mutated EOC, the ARIEL3 trial confirmed the

efficacy of rucaparib, with PFS increasing from 5.4 to 10.8 months

(HR, 0.36; P<0.0001) (49). The

VELIA trial assessed veliparib added to first-line chemotherapy and

as maintenance, which reported an increase in PFS from 17.3 to 23.5

months (HR, 0.68; P<0.001), which supports the role of PARP

inhibitors in newly diagnosed EOC (50). Notably, the PAOLA-1 trial evaluated

the combination of olaparib with bevacizumab in HRD-positive

patients, which demonstrated improved PFS from 16.6 to 22.1 months

(HR, 0.59; P<0.001), which suggested potential synergy between

DNA repair inhibition and anti-angiogenic therapy (35). Together, these trials establish the

clinical efficacy of PARP inhibitors across different settings:

BRCA-mutated, HRD-positive and BRCA wild-type subpopulations. While

resistance mechanisms and optimal combinations remain areas of

active research, ongoing research continues to explore the role of

PARP inhibitors in frontline and maintenance therapy (Table I). These results have firmly

established PARP inhibitors, particularly olaparib and niraparib,

as standard of care in maintenance therapy for EOC.

| Table I.Efficacy of targeted therapies in

improving PFS across patient populations with ovarian cancer. |

Table I.

Efficacy of targeted therapies in

improving PFS across patient populations with ovarian cancer.

| A, PARP

inhibitors |

|---|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Clinical trial | Drug | NCT no. | Clinical trial

subject/design | Control to

treatment PFS improvement, months | HR (95% CI) | P-value | (Ref.) |

|---|

| Moore et al,

2018 | SOLO-1 | Olaparib | NCT01844986 | Newly diagnosed

BRCA-mutated EOC | 13.8–56 | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | <0.001 | (40) |

| Psomiadou et

al, 2021 | PRIMA | Niraparib | NCT02655016 | Advanced ovarian

cancer (BRCA and non-BRCA) | 8.2–13.8 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | <0.001 | (29) |

| Abitbol et

al, 2019 | ARIEL3 | Rucaparib | NCT01968213 | Recurrent

BRCA-mutated EOC | 5.4–10.8 | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) | <0.0001 | (30) |

| Chen et al,

2023 | VELIA | Veliparib | NCT02470585 | Newly diagnosed

EOC | 17.3–23.5 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | <0.001 | (31) |

| Baum et al,

2022 | PAOLA-1 | Olaparib +

bevacizumab | NCT02477644 | HRD-positive

ovarian cancer | 16.6–22.1 | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | <0.001 | (24) |

|

| B, Angiogenesis

inhibitors |

|

| First author,

year | Clinical

trial | Drug | NCT no. | Clinical trial

subject/design | Control to

treatment PFS improvement, months | HR (95%

CI) | P-value | (Ref.) |

|

| Rauh-Hain et

al, 2024 | GOG-0218 | Bevacizumab | NCT00262847 | Advanced ovarian

cancer (first-line) | 10.3–14.1 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | <0.001 | (9) |

| Ray-Coquard et

al, 2023 | ICON7 | Bevacizumab | NCT00483782 | Newly diagnosed

advanced ovarian cancer | 17.3–19 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.004 | (32) |

| Zhao et al,

2024 | OCEANS | Bevacizumab | NCT00434642 | Platinum-sensitive

recurrent ovarian cancer | 8.4–12.4 | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | <0.0001 | (33) |

| Nezhat et

al, 2024 | AGO-OVAR16 | Pazopanib | NCT00484442 | Advanced ovarian

cancer (maintenance) | 12.3–17.9 | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) | 0.0021 | (34) |

|

| C, Tyrosine

kinase inhibitors |

|

| First author,

year | Clinical

trial | Drug | NCT no. | Clinical trial

subject/design | Control to

treatment PFS improvement, months | HR (95%

CI) | P-value | (Ref.) |

|

| Ray-Coquard et

al, 2019 | ALTER-GO-010 | Anlotinib | NCT02773524 | Newly diagnosed

advanced ovarian cancer: A phase II, single-arm | 6 months, 100%; 9

months, 100% | 5.3 (3.7–8) | Final median PFS

not yet reached due to ongoing follow-up | (35) |

| Predina et

al, 2012 | MITO 11 | Pazopanib +

Paclitaxel | NCT01335226 |

Platinum-resistant/refractory advanced

ovarian cancer | 3.5–6.3 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.0002 | (36) |

| Xiao et al,

2024 | NCT03367741 | Cabozantinib +

Nivolumab |

| Recurrent

endometrial cancer | 1.9–5.3 | 0.6 (90% CI,

0.3–1) | 0.09 | (37) |

Angiogenesis inhibitors

Angiogenesis serves a key role in ovarian cancer

progression, which supports tumor growth and metastasis by

establishing a dedicated blood supply. Targeting this pathway has

yielded promising therapeutic strategies, particularly with

bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against VEGF and pazopanib, a

multi-targeted angiogenesis inhibitor (16,51).

In the GOG-0218 trial, bevacizumab added to standard

first-line chemotherapy extended PFS from 10.3 to 14.1 months (HR,

0.717; P<0.001), which highlighted its benefit in newly

diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (16). Similarly, the ICON7 trial

demonstrated a modest but notable improvement in PFS (17.3–19

months) in patients receiving bevacizumab with chemotherapy (HR,

0.81; P=0.004) (52). In the

recurrent setting, the OCEANS trial confirmed the benefit of

bevacizumab in platinum-sensitive relapse, with PFS rising from 8.4

to 12.4 months (HR, 0.484; P<0.0001) (53). For maintenance therapy, the

AGO-OVAR16 study evaluated pazopanib and observed a PFS extension

from 12.3 to 17.9 months in advanced ovarian cancer (HR, 0.77;

P=0.0021) (51).

In recurrent settings, the OCEANS trial demonstrated

that adding bevacizumab to chemotherapy improved PFS from 8.4 to

12.4 months (HR, 0.484; P<0.0001) in platinum-sensitive

relapses. Similarly, the AGO-OV/AR16 study demonstrated that

pazopanib maintenance extended PFS from 12.3 to 17.9 months in

advanced ovarian cancer (HR, 0.77; P=0.0021). Despite these

positive results, resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy remains a

challenge and future directions may involve biomarker-guided

patient selection or combination regimens with immunotherapy or

PARP inhibitors (Table I). While

bevacizumab is incorporated into standard regimens based on

GOG-0218 and ICON7, other agents such as pazopanib warrant further

investigation.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

TKIs represent a diverse class of targeted agents

designed to interfere with signaling pathways that mediate tumor

cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis and invasion (54–56).

TKIs block multiple oncogenic signaling cascades that contribute to

ovarian cancer growth and spread. By inhibiting the VEGFR and

platelet-derived growth factor receptor, TKIs disrupt angiogenesis

and stromal support for tumor proliferation, while blockade of

fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling further impairs

neovascularization and cell survival. In addition, inhibition of

the hepatocyte growth factor/c-MET axis reduces tumor cell motility

and invasion, and targeting other kinases such as AXL and RET

overcome resistance mechanisms and attenuates survival pathways in

cancer cells (57–59). Several TKIs have been investigated

in ovarian and endometrial cancer types, with growing evidence

supporting their utility, especially in combination strategies. For

example, anlotinib, a multi-targeted TKI assessed in the

ALTER-GO-010 phase II trial for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian

cancer. This single-arm study reported a 100% PFS at both 6 and 9

months, with a median PFS of 5.36 months (95% CI, 3.68–7.98),

although final PFS was not yet reached due to ongoing follow-up

(54,60). The MITO 11 study, while primarily

assessing anti-angiogenesis, also demonstrated the efficacy of

pazopanib, which possesses TKI activity. Pazopanib combination with

paclitaxel yielded notable improvements in PFS in a

platinum-resistant/refractory cohort (55). A novel combination of a TKI and

immunotherapy was explored in trial NCT03367741, which evaluated

cabozantinib plus nivolumab in recurrent endometrial cancer.

Patients receiving the combination had a PFS of 5.3 vs. 1.9 months

with nivolumab alone (HR, 0.59; P=0.09) (56). Although these trials focused on

endometrial compared with ovarian cancer, these findings highlight

the expanding landscape of TKI-based combinations in gynecological

oncology.

Furthermore, in the NCT03367741 study, the

combination of cabozantinib and nivolumab was investigated in

recurrent endometrial cancer, which indicated a PFS improvement

from 1.9 to 5.3 months (HR, 0.59), which suggests potential synergy

between TKIs and immune checkpoint inhibitors, although these

findings remain preliminary and warrant further exploration in

ovarian cancer (56). Overall,

while TKIs alone have demonstrated modest efficacy, their

integration into combinatorial regimens, especially with immune

checkpoint inhibitors, may offer enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

Ongoing trials continue to assess the optimal positioning of TKIs

in ovarian cancer treatment, including in front-line, maintenance

and recurrent settings (Table I).

TKI-based combinations, such as those explored in ALTER-GO-010 and

NCT03367741, remain investigational and require validation through

larger trials.

Immunotherapeutic strategies in EOC

Vaccines

Several types of vaccines have been investigated in

EOC, most containing proteins or peptides that are associated with

ovarian cancer. Examples of tumor-associated antigens targeted in

ovarian cancer vaccines include MUC1, cancer-testis antigen

NY-ESO-1, WT1, folate receptor α and mesothelin (61). Numerous studies have seen T-cell

responses or longer disease stability in patients who are getting

treatment; however, not all of these studies demonstrated the same

benefits (62–64). The initial vaccine evaluated in EOC

and the only vaccine assessed in a randomized phase III trial was

canvaxin. Autologous tumor cell lysates were changed to add a novel

glycosylation site to the mucin 1 protein, which is a known antigen

located in ovarian tumors. The vaccine generated antibody responses

in 88% of vaccinated patients and seemed to improve tolerance

compared with the chemotherapy recommended by the physician in a

selected group of women. Eventually, this trial had to be

discontinued because the tumors were not under control (65–67).

However, canvaxin was still investigated in other studies as an

adjuvant, with and without chemotherapy, specifically in patients

with EOC (68,69). Several recent clinical trials have

evaluated novel antigen-targeted vaccines in EOC (61). The phase I study of folate

receptor-α peptide vaccine in patients with advanced ovarian cancer

demonstrated induction of FRα-specific CD8+ T-cell

responses in 90% of participants and disease stabilization in 40%

at 6 months. A multicenter phase II trial of the MUC1-liposomal

vaccine tecemotide added to neoadjuvant platinum-taxane

chemotherapy reported enhanced MUC1-specific CD4+ and

CD8+ T-cell responses in 75% of patients, with a

12-month PFS of 65% compared with 50% historical controls. These

treatments demonstrate the potential to prepare women for

subsequent therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (61,67).

Cell-based interventions

Adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

and engineered CAR-T cells targeting mesothelin, HER2 or folate

receptor α have demonstrated potent antigen-specific cytotoxicity

and clinical activity in early-phase trials of EOC, especially for

antibody-coated T cells, chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T),

specifically chosen tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes or those that

have been engineered to express a tumor-specific T-cell receptor

(70–72). By using genetic engineering to

change the T cells of a patient, CAR-T therapies make it possible

for these cells to express specific receptors that help find and

kill cancer cells. CAR molecules have an antigen-binding domain

that is outside of cells, a transmembrane domain and an

intracellular signaling domain that activates more co-stimulatory

receptors after interacting with the target epitope (73,74).

Therefore, CAR-Ts demonstrate specificity for a certain antigen

while also being less dependent on HLA expression. CAR-T therapies

have evolved in recent years and gaining attention in the field.

The anti-CD19 therapy has demonstrated potential in treating

patients with B-cell malignancies (75). Concerning EOC, CAR-T-based

approaches have been created to target different antigens

associated with tumors, such as mesothelin, HER2 and folate

receptor α. These treatment approaches have demonstrated potential

in early-stage clinical trials (76–79).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have transformed the

treatment landscape for multiple malignancies, including metastatic

melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma. By

blocking receptors such as PD-1 on T cells or ligands like PD-L1 on

tumor cells, these agents prevent inhibitory signaling that

normally dampens T-cell activation. Specifically, PD-1/PD-L1

blockade restores T-cell receptor signaling, leading to increased

proliferation of effector T cells, enhanced cytokine production and

sustained antitumor cytotoxicity. The goal of anti-PD-1/PD-L1

therapies was to revive lymphocytes that had been eliminated by

advanced tumors. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies demonstrated efficacy

for several types of cancer that exhibited HLA-antigen

presentation; therefore, the demonstrating potential for these

types of drugs to help treat EOC. The effectiveness of these drugs

could be increased by combining them with other treatments, such as

VEGF inhibitors, PARP inhibitors or platinum-based chemotherapy

(64,80). The efficacy of both anti-PD-1 and

anti-PD-L1 antibodies have been assessed in patients with EOC.

Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy in EOC has produced modest clinical

benefits. In the phase II trial of nivolumab in platinum-resistant

ovarian cancer, the objective response rate was 15% and the disease

control rate (responses plus stable disease ≥6 months) was 45%,

with a median PFS of 3.5 months. Similarly, pembrolizumab in the

KEYNOTE-100 study achieved an ORR of 8% and a DCR of 34%, with a

median PFS of 2.1 months, indicating that while a subset of

patients experiences prolonged stabilization, the overall impact on

disease control remains limited (81,82).

As a stand-alone treatment, PD-L1 blockade has had response rates

of <15%. This suggests that blocking the PD-L1/PD-1 interaction

may not be enough to activate and grow T cells, unlike what has

been reported with anti-CTLA-4 therapies. Consequently, further

immunotherapy approaches are currently being investigated (64,80).

Combining targeted therapies with immunotherapy or

chemotherapy holds notable potential in improving outcomes for

patients with EOC. PARP inhibitors, when combined with immune

checkpoint inhibitors, may enhance antitumor immunity by increasing

the tumor neoantigen load and modulating the tumor microenvironment

(37,83). Similarly, combining anti-angiogenic

agents with immunotherapy can normalize tumor vasculature,

promoting enhanced immune cell infiltration. However, these

combinations present challenges, including increased risk of

overlapping toxicities, optimal treatment schedule, dosing

strategies and patient selection. Optimal sequencing refers to the

strategic order and timing of administering each therapy to

maximize synergistic efficacy and minimize cumulative toxicity. In

EOC combinations: For PARP inhibitor + ICI: Sequencing may involve

giving the PARP inhibitor first to induce DNA damage and neoantigen

release, then administering PD-1/PD-L1 blockade at the peak of

antigen presentation to reinvigorate T cells. For anti-angiogenic +

ICI: VEGF inhibition is often delivered prior to checkpoint

blockade to normalize abnormal tumor vasculature and improve

effector T-cell infiltration, followed by PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies to

sustain the immune response (37,84,85).

Furthermore, identifying reliable biomarkers to predict response

remains an unmet need (86).

Ongoing trials are actively exploring these strategies and future

research will be key to refining combination approaches and

determining their place in clinical practice (37).

Clinical outcomes and efficacy of MITs

Over the past few decades, MITs such as laparoscopy

and robotic-assisted surgery have increasingly been incorporated

into the surgical management of EOC. Originally introduced for

early-stage disease, these approaches have expanded into selected

cases of advanced-stage (FIGO III–IV) cancer (9,87).

Previous studies have demonstrated that, in appropriately selected

patients with EOC, MITs can reduce blood loss, shorten hospital

stays and accelerate postoperative recovery, all while maintaining

long-term oncological outcomes comparable to open laparotomy

(27,88). Furthermore, the enhanced

visualization of retroperitoneal spaces during MIS may support more

accurate staging and surgical precision.

However, outcomes associated with MIS depend heavily

on surgeon expertise, institutional experience and careful patient

selection. Integrating MIS into oncological practice requires

gynecological oncologists to master advanced laparoscopic

techniques, particularly when pursuing complete cytoreduction in

high-risk patients. Standardization of surgical protocols,

including safe tumor handling and use of containment systems,

remains essential to minimize the risk of intraoperative tumor

spread. The clinical efficacy of MIS in advanced EOC has been

summarized from cohort studies, meta-analyses and emerging

randomized trial data; the residual disease rates, survival

outcomes, recurrence patterns and real-world implementation across

high-volume centers were also assessed (Table II).

| Table II.Summary of key comparative studies on

minimally invasive vs. open cytoreductive surgery in advanced-stage

EOC. |

Table II.

Summary of key comparative studies on

minimally invasive vs. open cytoreductive surgery in advanced-stage

EOC.

| First author,

year | Design | Country | Setting | No. of patients

(stage) | Intervention vs.

control | Key findings | (Ref.) |

|---|

| Jorgensen et

al, 2023 | NCDB retrospective

cohort (multicenter). | USA | Interval debulking

after NACT (2013–2018) | 7,897 (stage

III–IV). MIS, 2,021; Open, 5,876 (after matching) | MIS IDS vs. open

IDS (propensity-matched) | OS: Median 46.7

months MIS vs. 41.0 months open (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79–0.94; no

detriment). 5-year OS: ~38 vs. 35% (ns). Residual disease: R0

achieved in 76% MIS vs. 73% open (MIS had slightly lower residual

rates). Morbidity: 90-day mortality 1.4 vs. 2.5% (P<0.01);

shorter LOS (~3 vs. 5 days). MIS usage rose to ~29% by 2018; cases

had less extensive disease (fewer multi-organ resections). | (27) |

| Alletti et

al, 2016 | Single-institution

case-control | Italy | Interval debulking

(after NACT) | 46 (stage III).

MIS, 23; open, 23 (matched on chemotherapy response) | Laparoscopic IDS

vs. open IDS | OS/PFS: No

significant difference in 5-year OS or PFS between groups (matched

selection). One analysis demonstrated median PFS 18 MIS vs. 12

months open (P<0.05), attributed to selection. Residual disease:

100% R0 in both groups (all patients optimally debulked).

Perioperative: MIS had less blood loss and shorter hospital stay.

Demonstrated feasibility of complete laparoscopy in

responders. | (92) |

| Feuer et al,

2013 | Single-center

retrospective | Israel | Mixed PDS/IDS cases

(stage III–IV) | 89 (advanced EOC).

MIS, 63; open, 26 (open included conversions) | Robotic-assisted

MIS vs. open (mixed timing) | OS/PFS: No

differences in PFS or OS between robotic MIS and open laparotomy.

Residual disease: laparotomy. Residual disease: Comparable R0

rates. All cases were R0 by inclusion (complete gross resection

achieved). More patients in MIS group had received NACT (52 vs. 15%

in open), which indicates selection of responders for MIS.

Demonstrated safety of robotic debulking with similar

outcomes. | (21) |

| Magrina et

al, 2011 | Multi-center

retrospective | Spain and USA | Mixed PDS and IDS

(primary or secondary cytoreduction) | 171 (stage III–IV).

Robot, 25; lap, 27; open, 119 | Robotic MIS vs.

conventional laparoscopy vs. open | OS: No OS

differences among the three groups. Residual disease: R0 was

achieved more often in open surgery (data from one center

demonstrated higher complete resection in laparotomy), but all

groups had high optimal debulk rates (>90%). PFS: MIS groups had

longer PFS compared with open in this series (P<0.05)

Perioperative: MIS had longer OR time in robot group, but much

lower EBL and shorter LOS. Highlighted that extensive disease cases

went open, explaining R0 difference. | (22) |

| Pereira et

al, 2022 | Dual-center

retrospective | Spain and USA | Both PDS and IDS

analyzed (2012–2013) | 89 (stage IIIC-IV

unresectable at diagnosis). IDS, 59 after NACT; PDS, 30 upfront.

Subgroups, MIS vs. open | MIS vs. open at

IDS; also some MIS vs. open PDS | OS: At last

follow-up, survival favored MIS (47.5 MIS vs. 30% open alive in IDS

cohort), although groups differed. No statistically significant OS

disadvantage for MIS in either PDS or IDS. Recurrence: No

difference in recurrence rate between MIS and open. Findings: MIS

was viable for IDS in selected patients without compromising

survival. Significantly shorter hospital stays with MIS (2 days vs.

8 days) and fewer bowel resections at IDS. | (90) |

| Hayek, 2024 | NCDB analysis

subseta; multi-center | USA | Interval R0 cases

only | 2,412 (stage III–IV

IDS with complete gross resection). MIS, 25.9%; open, 74.1% | MIS vs. open

Interval R0 (real-world subset) | OS: No difference

in OS for MIS vs. open R0 debulking (median OS ~51 vs. 46 months;

HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.94–1.26; P=0.17). Achieving R0 negated route as

a factor in survival. Morbidity: MIS had shorter hospital stays.

30/90-day mortality and readmission were low and similar between

groups. Other: MIS use increased from ~12% in 2010 to 36.5% in

2019. Open surgery group had more ‘extensive’ procedures (53% vs.

41%; P<0.001). Real-world data from community centers mirrored

high-volume outcomes. | (93) |

Residual disease rates

Achieving minimal or no gross residual disease (R0)

is critical in advanced ovarian cancer. Recent studies indicate

that MIS can attain similar optimal cytoreduction rates as open

surgery in selected patients. A 2024 meta-analysis stratified by

surgery timing reported no notable difference in optimal debulking

rates between MIS and laparotomy for both primary debulking surgery

(PDS) and interval debulking surgery (IDS). In interval debulking

after NACT, the pooled risk ratio for achieving optimal

cytoreduction with MIS was ~1.03 relative to open surgery (95% CI,

0.96–1.11; P=0.05), essentially indicating equivalent success

rates. Similarly, the rate of complete gross resection (no

macroscopic disease) did not differ between MIS and open approaches

(risk ratio, ~1.01; 95% CI, 0.97–1.07) (34). These findings have been similarly

reported by other studies (34,42,89); a

2022 systematic review reported no notable disparity in R0

(complete debulking) or R1 (≤1 cm residual) rates between

laparoscopic/robotic IDS and open IDS (89).

Individual cohort studies reinforce that

well-selected MIS cases can achieve high R0 rates. In the

multi-center MISSION trial (2019), which evaluated 127 patients

undergoing MIS IDS, 96.1% of patients had no gross residual disease

at surgery. The conversion to laparotomy in that series was only

~3.9%, which implied that nearly all intended MIS procedures could

be completed with optimal resection (42). Certain single-center studies have

reported slightly lower complete resection rates with MIS, but

these differences appear to reflect case selection. For example,

Pereira et al (90) observed

a higher R0 rate in their laparotomy group compared with MIS

groups, potentially because surgeons attempted MIS only in cases

with smaller tumor burden. Across numerous reports, when MIS was

chosen for patients with limited disease distribution or marked

chemotherapy response, residual disease outcomes were comparable

with to open surgery (34,89).

Overall survival

Long-term survival outcomes (overall survival and

PFS) have been a central concern when comparing MIS to open

debulking in advanced ovarian cancer. Notably, no RCT has yet

reported survival comparisons, although the phase III LANCE trial

is currently evaluating MIS vs. open laparotomy in this setting

(9,27,91).

However, multiple large observational studies and meta-analyses in

the last 5 years consistently reported no OS disadvantage with MIS

and some even suggest non-inferiority or parity in survival

(34,88,89).

A comprehensive 2023 analysis of nearly 7,900

patients from the U.S. National Cancer Database (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/)

demonstrated no notable difference in overall survival between MIS

and open surgery for interval debulking after NACT. After

propensity score matching, the median OS was ~46.7 months with MIS

vs. 41.0 months with laparotomy (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79–0.94);

5-year survival probabilities were essentially equivalent (38.3%

MIS vs. 34.8% open; P<0.01 in favor of MIS. This apparent

advantage may have been influenced by differences in patient

selection). There was no detriment to survival with MIS, if

anything, MIS reported a slight survival benefit in this weighted

analysis (27). This aligns with a

Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Committee meta-analysis (2024) which

reported no notable OS differences between MIS and open approaches

in advanced-stage disease, whether for PDS or IDS. For instance, in

advanced primary debulking cases, the pooled odds of survival were

similar (OR, ~0.66; 95% CI, 0.36–1.22; P>0.05), and likewise no

OS disadvantage was seen for MIS IDS (OR, ~0.93; CI 0.25–3.44)

(88).

PFS has also been reported to be equivalent between

minimally invasive and open surgery approaches. Numerous studies

found no notable PFS difference between MIS and open surgery groups

(20). In a meta-analysis of 6

studies (3,528 patients) focusing on IDS after NACT, MIS was

associated with a trend toward improved PFS but no OS difference

(89). Specifically, patients in

the MIS group had slightly improved PFS in some cohorts, possibly

due to selection of improved responders, but on the whole PFS is

equivalent when accounting for confounders. For example, Alletti

et al (92) reported median

PFS of 18 months with laparoscopy vs. 12 months with open in a

single-center IDS series, but no difference in 5-year OS. In the

pooled analysis of six studies (3,528 patients) after NACT, MIS was

associated with a median PFS of 15.8–18.0 months vs. 12.0–14.2

months with open surgery, translating into an absolute PFS gain of

1.6–3.8 months. From meta-analysis data, the pooled hazard ratio

for progression was 0.85 (95% CI, 0.73–0.99; P=0.04), indicating a

15% lower risk of progression with MIS, even though overall

survival did not differ between the groups (89).

Several individual center studies and registry

analyses further support OS parity. A study by Pereira et al

(90) reported that 5-year survival

rates were comparable with MIS. In their analysis, 47.5% of

patients with MIS IDS were alive at 5 years vs. 30% of patients

with open IDS (41 vs. 28% for MIS vs. open PDS). While such

differences reflect selection factors, MIS did not compromise

long-term survival in appropriate candidates. Additionally, a

recent conference report including >2,400 interval debulking

cases with R0 resection reported median OS ~51 months MIS vs. 46

months open, a difference that was not statistically significant

(HR, ~1.1; P=0.17) (92). Taken

together, current evidence indicated that overall survival with MIS

in advanced ovarian cancer is comparable to open surgery, provided

patients are selected for achievable complete cytoreduction

(88,93).

Recurrence patterns

Beyond survival duration, the pattern and timing of

disease recurrence are important considerations. Thus far, studies

have not identified any unique or worse recurrence patterns

associated with minimally invasive debulking. Recurrence rates

appear similar between MIS and open approaches in advanced-stage

patients. For patients with advanced-stage (FIGO III–IV) EOC

undergoing interval debulking after NACT, Zeng et al

(89) performed a meta-analysis of

six studies encompassing 3,528 patients and found no significant

difference in recurrence rates between minimally invasive surgery

and open laparotomy groups. In a dual-center retrospective cohort

of 89 patients with stage IIIC-IV EOC (59 MIS vs. 30 open IDS),

Pereira et al (90) reported

equivalent recurrence frequencies in both approaches. Similarly,

Alletti et al (92)

evaluated 46 patients with stage III EOC (23 MIS vs. 23 open IDS)

and observed no increase in early or atypical recurrences with

minimally invasive techniques. A single-center comparison of

robotic vs. open cytoreduction reported that the recurrence-free

survival was longer in the MIS cohort (potentially reflecting

case-specific factors such as patient selection bias, tumor stage

distribution, preoperative disease burden, performance status or

differences in adjuvant therapy protocols), but recurrence

frequency was similar across groups. No study to date has

demonstrated a higher risk of recurrence solely due to the

minimally invasive technique when surgical completeness is

equivalent (34).

A specific concern with MIS is the risk of port-site

metastases (tumor seeding at trocar sites). Port-site metastases

have been documented in advanced ovarian cancer after diagnostic

laparoscopy, with rates of 5–17% reported when no precautions were

taken. However, these metastases are usually detected at the time

of subsequent surgery or during chemotherapy and are resected or

sterilized by treatment. Furthermore, long-term follow-up has

indicated no adverse impact on prognosis from port-site implants if

patients receive standard therapy (94). In a novel published series of MIS

IDS (from 2015 onwards), port-site recurrences were rare (>1–2%

of cases) and have not been reported as a notable pattern of

failure compared to the overall recurrence rates in ovarian cancer

(89,95). The majority of recurrences after

either MIS or open debulking occur in typical intra-abdominal

locations (peritoneum and retroperitoneum account for 75–80% of

recurrence sites), with remaining recurrences distributed among

distant sites (liver, brain and lungs), reflecting the biology of

ovarian cancer compared with the surgical route (42,94).

Overall, current evidence suggests no difference in recurrence

patterns between MIS and open surgery; the key determinant is

whether complete cytoreduction is achieved, not the incision type

(89). Notably, no increase in

distant or early recurrence has been observed with MIS, unlike

early-stage cervical cancer MIS trials (95). Ongoing studies will continue to

monitor for any subtle differences in recurrence dynamics with

MIS.

Patient selection criteria

Patient selection is a key factor in the success of

minimally invasive cytoreductive surgery. Several previous studies

emphasize that MIS in advanced ovarian cancer should be reserved

for patients with a limited disease burden that can be addressed

with standard cytoreductive techniques not requiring extensive

multiorgan resections. Common selection criteria include: Notable

response to NACT (for interval cases) with substantial tumor

shrinkage; disease distribution confined to areas amenable to

laparoscopic resection (for example, superficial peritoneal

implants, easily accessible pelvic/abdominal disease, omental

caking that can be removed en bloc); absence of extensive

diaphragmatic or mesenteric disease requiring large incisions; and

patient factors such as body habitus and comorbidities that favor a

minimally invasive approach (42,94).

In practice, surgeons often perform a thorough preoperative imaging

assessment and may even use diagnostic laparoscopy to confirm that

complete resection may be feasible via MIS ports (89).

Previous studies demonstrated that when these

selection principles are applied, patients with MIS tend to have

lower initial tumor load. For example, in the National Cancer

Database (NCDB; http://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/)

study, MIS cases had significantly fewer ‘additional cytoreductive

procedures’ (for example, bowel or spleen resections) compared with

open cases (59.3 vs. 70.8%; P<0.01). This suggests surgeons

selected MIS for patients with less disseminated disease, hence

needing fewer organ resections. In the same dataset, the rate of

any gross residual disease was slightly lower in patients with MIS

(23.9 vs. 26.7% in open; corresponding to higher complete resection

rates) (27), which suggested that

surgeons attempted MIS primarily in cases where they anticipated

achieving R0. Another analysis noted patients with MIS were less

likely to require ‘extensive’ surgery compared with open patients

(41 vs. 53%; P<0.001). All of this reflects a selection bias:

Candidates for MIS are typically those with resectable disease of

low complexity (42,93). A multi-center consensus concluded

that MIS is appropriate when surgery can be limited to standard

cytoreductive procedures without major complexity (42).

Beyond tumor factors, patient factors serve a role;

a previous study reported that patients with MIS were on average

older compared with those undergoing open surgery (93), possibly because surgeons chose MIS

to minimize morbidity in older patients (≥65 years) who had

adequate response to chemotherapy. Other selection considerations

include performance status and surgeon experience. High-volume

centers with advanced MIS skills are more likely to attempt

laparoscopy/robotics on borderline cases, whereas less experienced

centers might opt for laparotomy for the same patient. In summary,

ideal candidates for MIS PDS/IDS are those with regionally confined

disease, notable response to therapy and no need for large en

bloc resections, as determined by imaging or laparoscopic

assessment. These selection criteria underlie the similar outcomes

seen, and differences in the characteristics of the patient groups,

such as age, comorbidities, response to chemotherapy and extent of

disease, rather than the surgical approach itself, may account for

any modest benefits observed in the MIS cohorts (27,89).

Data limitations and ongoing

studies

Although outcomes thus far are encouraging, it is

important to acknowledge the limitations of existing data.

Selection bias is the foremost limitation, as all comparative

studies to date are non-randomized and patients with MIS inevitably

had more favorable disease characteristics. Propensity score

matching and multivariable adjustments, as performed in the NCDB

analyses (27), help mitigate but

cannot eliminate this bias. Thus, it remains possible that

equivalent patients with extensive disease would fare differently

with MIS compared with open surgery. High-level evidence from

randomized trials to confirm oncological safety.

To date, no RCT has published definitive results

comparing MIS vs. open debulking in advanced ovarian cancer

(34). However, the first such

trial is presently underway. The international LANCE trial is a

phase III multicenter RCT designed to evaluate non-inferiority of

MIS vs. laparotomy for IDS in advanced-stage ovarian cancer after

3–4 cycles of NACT (95). The pilot

phase of the trial demonstrated feasibility and acceptable

conversion rates, enabling full accrual. The outcome of the trial

(disease-free survival as primary endpoint) will provide level I

evidence on the oncological efficacy of MIS in this setting

(9,95). Therefore, until the LANCE trial

results are reported, the present review relied on observational

data.

Another limitation is that most studies have been

conducted in specialized centers or databases from developed

healthcare systems, which may not reflect all practice settings

globally. There is a paucity of data on MIS outcomes in

resource-limited regions or low-volume centers. Additionally,

follow-up duration in previous MIS series was still short, as

several studies reported a median follow-up of 3–4 years, so

long-term survival equivalence and patterns of late recurrence

require continued investigation (42). Data on recurrence patterns

specifically (for example whether MIS might lead to different

metastatic spread) are limited. To date, no concerning safety

issues or unexpected complications have been reported. Numerous

analyses (for example, NCDB) lack specific details such as exact

residual tumor size or QoL outcomes. QoL and recovery metrics may

favor MIS (due to faster recovery), but robust prospective data on

patient-reported outcomes are needed.

In summary, although current evidence supports MIS

as an acceptable approach in advanced ovarian cancer, it is still

largely retrospective. Results must be interpreted with caution

given the non-randomized nature of published studies and potential

confounders (34). The ongoing

LANCE RCT and other prospective studies will be key to conclusively

establish whether MIS is comparable with open surgery in all

oncological outcomes or if differences may emerge when selection

bias is removed. To date, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN) and the European Society of Gynecological Oncology (96) guidelines emphasize that MIS for

advanced ovarian cancer should be offered only in highly selected

patients by experienced surgeons, preferably in the context of

clinical trials or protocols (38,89).

Furthermore, current evidence is largely derived from retrospective

studies with inherent selection biases. While several cohort

analyses indicate non-inferior outcomes for MIT compared with open

surgery, the lack of level I evidence from completed RCTs mandates

cautious interpretation. The ongoing LANCE trial is expected to

address this gap.

Real-world outcomes in high-volume

centers

Real-world data from high-volume gynecological

oncology centers have consistently reported that in appropriately

selected patients, MIS can safely replicate the oncological

outcomes of open cytoreduction. For instance, the NCDB analyses

demonstrated that between 2013 and 2019, MIS usage in IDS increased

significantly in the USA, with comparable overall survival (OS) and

even lower perioperative mortality compared with open surgery

(90-day mortality; 1.4 vs. 2.5%; P<0.01) (27). Similar findings were reported by the

MISSION study in Europe and South America (42) and by multi-center registries from

including a 2022 meta-analysis (89). These studies confirmed equivalent

5-year OS rates and high R0 rates with MIS when performed by

experienced teams (90,92). MIS has also been associated with

faster recovery, shorter hospital stays and earlier initiation of

postoperative chemotherapy in some cohorts (93). Collectively, these real-world data

suggest the feasibility and safety of MIS for advanced ovarian

cancer and support its broader implementation when patient

selection and surgical expertise are appropriate.

However, comprehensive data specifically addressing

QoL in advanced-stage EOC are limited. While some retrospective

analyses and small prospective series suggest potential QoL

benefits, large, well-powered studies are needed to establish

definitive conclusions. Furthermore, while some studies have

utilized validated patient-reported outcome instruments such as the

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality

of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-Core 30 and QLQ-Ovarian Cancer Module

28 to assess postoperative QoL in patients with EOC, robust PRO

data specific to advanced-stage disease remain sparse and warrant

further prospective investigation (97).

Challenges and limitations of MITs

MIS has the potential to improve the outcomes of EOC

surgery. However, the implementation of MIS must be accompanied by

high adherence to oncological principles, which will consequently

push the envelope in technically challenging cases. These are the

cases in which the use of conventional laparoscopy or

robotic-assisted laparoscopy can be limited, which leads to an

increased incompletion of surgery and residual disease. In

low-volume centers, adnexal masses may be misdiagnosed and thereby

given a less conservative approach, which can lead to stage

upstaging and incomplete surgery (42,87,98).

Therefore, preoperative and intraoperative protocols and criteria,

surgical expertise and the correct allocation of resources, that

is, ensuring that surgical expertise is available at several

tertiary reference centers as possible.

Previous studies have highlighted that

hepatobiliary involvement in ovarian cancer is associated with

increased tumor burden, necessitating more complex surgical

approaches and specialized expertise (42,87,98).

Findings by Di Donato et al (98) further confirmed that achieving

complete cytoreduction in such cases significantly impacted patient

survival outcomes. In the future, the use of novel imaging

techniques that can further assess tumor spread and the molecular

characteristics of cancer will contribute to patient selection,

allowing, whenever possible, an optimal MIS approach to be selected

for EOC surgery.

While MITs offer several advantages, they are not

free of risks; a key concern is the increased likelihood of

intraoperative complications, particularly in advanced-stage

ovarian cancer cases where optimal cytoreduction is technically

challenging. Additionally, suboptimal staging may lead to higher

recurrence rates due to the incomplete assessment of peritoneal

spread and lymph node involvement (34). Further studies are needed to

determine standardized protocols that minimize these risks and

ensure oncological safety.

Patient selection

Currently, there is a lack of consensus in the

field of gynecological oncology on the definition of ‘early stage’

ovarian cancer and its management. Typically, gynecological

oncologists identify most EOC types at an advanced stage and the

standard surgical intervention involves primary cytoreduction,

followed by discrimination (12,13).

However, two distinct cohorts of patients with apparently

early-stage disease (those with Stage I disease on imaging who are

ultimately found to have advanced disease at surgery and those with

localized Stage I disease) may potentially gain from varying

management approaches. In the early stages of the disease, surgery

could lead to the diagnosis of Stage IIIB serous carcinoma, which

may cause the disease stage to progress (12,13).

The NCCN guidelines currently advocate conducting

the standard staging of surgical procedures for tumors classified

as small stage I diseases (99). An

alternative biological perspective suggested evaluating an early

suspicious pelvic and/or para-aortic stage from a clinical

standpoint. It is possible for these rare conditions to be caused

by nodal endometriosis or dermoids or these conditions may be

associated with a slow progression of hematogenous

lymphangiomatosis, which usually occurs when endometriosis stays

the same (38,57,92,100).

Currently, research on the origins of these small, less aggressive

atypical nodular forms of cancer is being conducted. The surgical

techniques should vary when executed in a gynecology unit focused

on these distinct procedures. Only certain patients qualify as

suitable candidates for MIS in cases of advanced stage disease: i)

Patients with documented major response to NACT, defined by imaging

or laparoscopic assessment showing >80% reduction in tumor

volume and confinement of residual disease to easily accessible

pelvic and omental sites; ii) individuals whose disease

distribution is limited to superficial peritoneal implants, minor

omental caking that can be removed en bloc and absence of

extensive diaphragmatic or mesenteric involvement; iii) cases

without bulky upper abdominal disease or large bowel, splenic or

hepatic surface metastases, such that no multiorgan resections are

anticipated; iv) patients with Charlson comorbidity index <2 and

adequate performance status (ECOG 0–1), minimizing anesthesia risk

and facilitating rapid postoperative recovery; v) selected older

patients (aged ≥65 years) with limited tumor burden who stand to

benefit most from reduced perioperative morbidity and shorter

hospital stays; and vi) selected older patients (aged ≥65 years)

with limited tumor burden who stand to benefit most from reduced

perioperative morbidity and shorter hospital stays.

The feasibility and safety of MIS in selected

patients has been demonstrated in the MISSION study, where 96%

achieved no gross residual disease via MIS after NACT and

conversion to laparotomy occurred in only 3.9% of cases (57,92).

It could be suggested that patients should have: i) Imaging after

clinical evaluation by the multidisciplinary team with radiological

diagnosis; ii) FIGO stage IIIC or less; iii) Charlson comorbidity

index <2 (100); iv)

pauci-symptomatic small disease; v) imaging with pre-operative

diagnostic laparoscopy; and vi) no notable protein anemia. As for

the patients with carcinoma in situ (CIS), strong

de-swelling surgical procedures should be avoided; albumin and

hemoglobin must be normal; albumin and creatinine must be normal;

fitness status and adequate psycho-physiological support; no

overfeeding of the pathology or performance status; and ovarian

clear cell carcinoma and CIS, against serous papillary histotype

required.

Proper patient selection is key to achieve

favorable outcomes in MIS. While early-stage disease, lower

histological aggressiveness and a lower Charlson comorbidity index

favor the feasibility of this approach, further research is

required to validate these selection criteria across diverse

patient populations and advanced-stage cases.

Training and expertise

The role of MIS in the management of ovarian cancer

has been well documented in the form of low invasive techniques

such as laparoscopic, robotic or single port surgery. Consequently,

the approach has been associated with favorable reports in terms of

blood loss, time, length of stay, wound complications and recovery

time. However, despite favorable outcomes for recurrence, mortality

and overall survival for patients receiving MIS, favorable surgical

results are only associated with centers that have extensive

experience in MIS.

The viability of hepatobiliary cytoreduction is

markedly influenced by the skill level of the surgeon and the

available resources at the institution. Previous studies have

demonstrated that high-volume centers tend to achieve superior

oncological outcomes compared with lower-volume centers (42,89,98).

Di Donato et al (98)

demonstrated that complete cytoreduction can be achieved in

patients with hepatobiliary metastases when conducted in

specialized centers with a multidisciplinary approach. In this

situation, procedures such as sentinel node mapping and the removal

of lymph nodes using minimally invasive methods have been

recognized as important (42,89,98).

However, these procedures should only be performed by surgeons with

documented expertise in minimally invasive debulking surgery,

following established institutional guidelines and quality

standards to ensure patient safety and adequate disease

management.

Future directions

Novel technology brings novel challenges in

training and implementing these technologies in clinical practice.

The implementation of robotic surgery, for instance, is associated

with a steep learning curve. The effectiveness of different

training models remains to be elucidated. Furthermore, not all

departments can afford to start a robotics program directly.

Specifically, in resource-limited healthcare systems, a

multimillion investment could endanger other goals. In the

development of both robotic and laparoscopic surgical techniques,

training in simulations is key. Since there are several types and

complexities of intraoperative complications, in vivo

training combined with mentored procedures before leading a

procedure might be beneficial.

It will be important to choose patients who are in

medically fit before surgery, have few comorbidities (such as

hypertension without end-organ damage, diet-controlled diabetes,

mild COPD with preserved lung function or stable thyroid disease),

have early-stage EOC and have a low risk of complications, as not

every patient with stage I–IV EOC will gain advantages from a

minimally invasive approach. Prospective trials and retrospective

cohort studies may combine to create and assess these algorithms.

Furthermore, the formulation of these guidelines is essential,

grounded in real data compared with relying on automated training

databases. Among promising innovations in EOC management, liquid

biopsy and advanced imaging techniques are poised to serve

transformative roles, yet several hurdles must be addressed before

widespread clinical adoption. Liquid biopsy approaches, such as

circulating tumor DNA, circulating tumor cells and exosomal RNA

analyses, offer non-invasive means for early detection, monitoring

of minimal residual disease and treatment stratification (101,102). However, the sensitivity and

specificity of these assays remain variable and standardization

across platforms is still evolving. Regulatory approvals are

currently limited and liquid biopsy is notably viewed as a

complementary adjunct compared with a replacement for traditional

imaging and tissue biopsy (101,102). Similarly, advanced imaging

modalities, including diffusion-weighted MRI, PET/CT with novel

tracers and AI-enhanced imaging, hold potential to improve the

detection of small-volume peritoneal disease and informing surgical

planning (103,104). Nevertheless, variability in

imaging sensitivity, the need for specialized infrastructure and

the lack of established cost-effectiveness data pose notable

barriers to routine clinical integration. As ongoing prospective

studies refine the performance and clinical utility of these

technologies, their eventual incorporation into multimodal EOC

management strategies will require careful consideration of

regulatory, logistical and economic factors.

Conclusion

MITs and molecular-based therapies have reshaped

the management of EOC, particularly in selected cases of

advanced-stage disease. The current evidence, including large

cohort studies and recent meta-analyses, demonstrated that in

appropriately chosen patients, MIS can achieve comparable

oncological outcomes to open surgery, with the added benefits of

reduced perioperative morbidity, faster recovery and earlier

initiation of adjuvant treatment. These surgical innovations, when

aligned with novel systemic therapies such as PARP inhibitors,

anti-angiogenic agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors, offer an

integrated approach that enhances survival and maintains QoL.

For practicing gynecological oncologists, these

findings underscore the importance of individualized treatment

planning based on disease burden, response to neoadjuvant therapy

and institutional expertise. However, the adoption of these

strategies must be guided by rigorous criteria for patient

selection, as well as multidisciplinary coordination. Despite these

advances, several gaps remain. Long-term survival data from RCTs

comparing MIS with laparotomy in advanced EOC are still pending.

Additionally, real-world outcomes in low-volume or resource-limited

settings require further validation. QoL metrics and

cost-effectiveness analyses also need to be integrated into future

research to further inform clinical decision-making.

Currently, several studies support the use of MITs

for staging and interval debulking following NACT in carefully

selected patients with advanced-stage EOC, when performed by

experienced surgeons (27,42,90).

For systemic therapy, PARP inhibitors have become standard of care

for maintenance treatment in BRCA-mutated and HRD-positive EOC,

based on high-level evidence from pivotal trials such as SOLO-1 and

PRIMA. By contrast, immunotherapy remains investigational in this

setting, with ongoing trials evaluating optimal combinations. Key

gaps include the need for level I data validating the long-term

oncological safety of MITs in advanced-stage EOC, improved

strategies for the integration of systemic therapies and robust

patient-reported outcome data to guide treatment decisions.

Addressing these questions will be key for the translation of

evolving innovations into clinical practice and to optimize the

personalized management of EOC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions