Introduction

According to the latest tumor epidemiological

statistics, prostate cancer (PCa) is still the most common tumor

affecting male reproductive and urinary health, with its incidence

rate and mortality ranking fourth and eighth, respectively

(1). PCa progresses slowly in the

early stages and surgical resection, radiation therapy and androgen

deprivation therapy can effectively halt the progression of

disease. However, approximately one-third of patients with PCa

develop recurrence or metastasis after radical surgery. These

patients can be treated with androgen-deprivation therapy, also

known as castration therapy, which involves the administration of

gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, or with surgical

castration (2). Unfortunately, most

patients develop disease progression again ~18 months after

treatment and are no longer affected by androgen levels. Instead,

the disease evolves into a more aggressive form of

castration-resistant PCa, either metastatic castration-resistant

disease or non-metastatic castration-resistant disease (3). The first-line treatment for

castration-resistant PCa mainly includes the chemotherapy drug

docetaxel along with novel endocrine drugs, such as abiraterone or

enzalutamide (4). Although the

early treatment response is good, drug resistance is still

inevitable in the later stages and no effective treatment exists

for these patients at present. Therefore, it is important to

explore the molecular mechanisms of PCa progression (5).

Mitochondria are responsible for the synthesis of

intracellular bioenergetics. In addition to the synthesis of ATP,

mitochondria can also synthesize macromolecular metabolic

precursors, such as lipids, proteins, DNA and RNA. Mitochondria can

also remove or use metabolic waste, such as reactive oxygen species

(ROS) and gases (6). Under normal

physiological conditions, mitochondria are important cell pressure

sensors and can coordinate cell adaptation to various stressors,

such as nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, DNA damage and

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Therefore, mitochondria can maintain

the growth and survival of tumor cells in harsh environments,

including nutrient depletion, hypoxia and tumor treatment, which is

a key factor in promoting tumor progression (7). An early study found that tumor cells

still tended to undergo glycolysis under aerobic conditions, known

as the Warburg effect, indicating that mitochondrial respiratory

defects may be the fundamental cause of tumor development. In

recent years, mitochondrial function and tumor metabolism

reprogramming have received increasing attention (8). Researchers have found that the Warburg

effect is not a characteristic of all cancer cells. Although

damaged mitochondria may drive the Warburg effect in some cases, a

number of tumor cells that exhibit Warburg metabolism also have

complete mitochondrial respiration and some tumor subtypes also

depend on mitochondrial respiration (7,9).

Biosynthesis and other functions of mitochondria are typically

upregulated in cancer and metabolic reprogramming has become an

important tumor marker (10). The

metabolic phenotype of prostate epithelial cells is unique and the

stages of tumor development and progression from prostatic

intraepithelial neoplasia to metastasis are different. Normal

prostate epithelial cells are highly dependent on glycolysis, but

during tumor progression, PCa cells gradually reactivate

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation while increasing glucose

metabolism and reducing citrate production (11,12).

In PCa, androgen receptors (ARs) also participate in cellular

metabolic reprogramming, which includes aerobic glycolysis,

mitochondrial respiration and de novo fat generation,

thereby meeting the metabolic and biosynthetic needs of PCa cells

(13,14).

In the present study, differentially expressed genes

(DEGs) in PCa were first identified by analyzing three datasets:

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD),

GSE46602 and GSE55945. This initial step focused on screening

general DEGs (upregulated or downregulated) between PCa and

adjacent normal tissues across the datasets, without restricting to

mitochondrial relevance. To narrow down the identified DEGs to

mitochondria-associated candidates, the first intersection was

performed by overlapping these general PCa DEGs with the full list

of human mitochondrial protein-coding genes from the MitoCarta3.0

database. This step yielded a preliminary set of differentially

expressed mitochondrial-related genes (DeMRGs) but still included

all genes that met both ‘differential expression in PCa’ and

‘mitochondrial localization’ criteria. To further refine and

prioritize high-confidence targets, a second targeted intersection

was conducted: The upregulated subset of the initially obtained

DeMRGs was re-intersected with the MitoCarta3.0 mitochondrial gene

list. This distinct step aimed to exclude potential false positives

and focus specifically on consistently upregulated DeMRGs, a subset

with stronger relevance to PCa progression as upregulated

mitochondrial genes are more likely to drive pro-tumor metabolic

reprogramming. Subsequently, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed on

these DeMRGs. The transcription factors and microRNAs (miRNAs)

associated with the DEGs were also analyzed to provide a basis for

further mechanistic studies. Furthermore, to explore the role of

mitochondrial-related genes in PCa, the present study analyzed the

correlation between key mitochondrial genes and immune infiltration

through immune infiltration analysis. Additionally, it investigated

the association of these genes with mitochondrial respiration and

their relationship with mitochondrial metabolic pathways in PCa,

aiming to identify potential mitochondrial hub genes involved in

PCa progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The PCa cell lines (Du145, PC-3 and LNcap) and

normal prostate cells (RWPE-1) purchased from American Type Culture

Collection) were cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine

serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C constant

temperature and 5% CO2. Du145 cells were maintained in

MEM (Biotecnómica), whereas PC-3 and LNcap were maintained in RPMI

(Biotecnómica) and RWPE-1 was maintained in K-SFM

(Biotecnómica).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the RWPE-1, PC-3, LNcap

and Du145 cell lines using RNAiso Plus reagent (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript™ RT

reagent kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd) at 42°C for 15 min and

85°C for 5 sec. Two-step qPCR was performed using SYBR Green

Reagent (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), C1000 Touch Thermal

Cycler and the CFX96 Real-Time System according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The primer sequences are listed in

Table I. The results were

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method, and the data are

expressed as a ratio of the control gene GAPDH (15).

| Table I.Sequences of the reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR primers. |

Table I.

Sequences of the reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR primers.

| Genes | Forward

(5′-3′) | Reverse

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| ACACB |

AGATCGCCTCCACCGTTGTC |

CTGTCACCTCACCTGTCTTCTACT |

| PDK4 |

TGAGTGTTCAAGGATGCTCTGTG |

GGTCTGGTTGGTTAAGTGTAGCA |

| GATM |

TCATTGGACCTGGTATTGTGCTTTC |

GTAATGAGGAGGTTGTGGTTAGT |

|

|

| AGG |

| MCCC2 |

AGGTGGCATTATTACAGGCATTGG |

CGGATGATGGGTCACTGACACTT |

| MRPL12 |

ACATCGCCAGCCTCACTCTC |

GGCTACCCACCACACTACAGA |

| FASN |

CAGCGGCAAGCGTGTGATG |

GTTGACCTGCGACCTCCTCC |

| GAPDH |

AATGGGCAGCCGTTAGGAA |

GAGACTAAACCAGCATAACCCG |

Public data acquisition and

preprocessing

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data for patients with PCa

were derived from the TCGA-PRAD dataset (TCGA-PRAD; http://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga),

which includes 502 cancer tissues and 52 adjacent tissues, and from

two datasets provided by the National Center for Biotechnology

Information Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo): GSE46602

(consisting of 36 cancer tissues and 14 adjacent tissues) and

GSE55945 (including sequencing data from 13 cancer tissues and 8

adjacent tissues) (16,17). In addition, the GSE70770 dataset was

used as an independent validation cohort, which contains RNA-seq

data for 220 PCa tissues and 73 adjacent non-cancerous tissues

(18). Using R v4.2.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/), the array datasets were

normalized using the limma package v3.58.1 and high-throughput

sequencing count data were normalized using DESeq2 (version 3.20.0)

to generate standardized matrices. Specifically, the DESeq function

was applied for normalization, which accounts for library size

differences and adjusts for gene-wise dispersion estimates. For

genes with multiple transcript IDs, the ID with the highest average

expression was selected. The original gene expression data

underwent log2 transformation and quantile normalization for

subsequent downstream analyses.

Identification and functional

enrichment analysis of DeMRGs

The DEGs found in PCa and adjacent tissues were

analyzed using the limma and DESeq2 packages, with the following

selection criteria: log2|fold change|≥1 and P<0.05.

DeMRGs were identified by intersecting these DEGs (from TCGA-PRAD,

GSE46602 and GSE55945) with 1,136 human mitochondrial

protein-coding genes from MitoCarta3.0 (https://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta/mitocarta30-inventory-mammalian-mitochondrial-proteins-and-pathways),

visualized via heat maps, Venn diagrams and volcano plots. GO

(http://geneontology.org) and KEGG (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg1.html)

enrichment analyses of DeMRGs were performed using R's

clusterProfiler package (v4.10.1). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(GSEA; http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/) with KEGG gene

sets (c2.cp.KEGG.v7.4.symbols.gmt from MSigDB; http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/)

was conducted, with significance defined as P<0.05 and false

discovery rate <0.05. The transcription factors and interacting

miRNAs of the identified DeMRGs were predicted using the online

platform NetworkAnalyst 3.0 (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/) and visualized with

Cytoscape software.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

analysis and hub gene extraction

In the present study, PPI networks of DeMRGs were

identified to determine the differences between PCa and its

adjacent tissues from the perspective of protein interactions.

First, the STRING online analysis tool (https://www.string-db.org/) was used to generate the

PPI network of DeMRGs. Then, the PPI network was analyzed using

Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org; CytoHubba plugin and DMNC;

v3.10.0) and screened out genes with a degree value ≥4 as core

genes for further research. The network type was full STRING. In

total, six core data sources were integrated to ensure interaction

reliability, including ‘experiments’, ‘databases’, ‘co-expression’,

‘neighborhood’, ‘gene fusion’ and ‘co-occurrence’. The interaction

score was set to a confidence threshold of 0.4.

Hub genes and PCa immune infiltration

analysis

The TCGA-PRAD differential gene volcano plot was

generated using R's ggplot2 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2; v3.5.1).

Core DeMRGs in TCGA-PRAD were obtained by intersecting TCGA-PRAD

DEGs with core genes. For immune infiltration analysis, R was used

to convert count data to transcripts per million (TPM), followed by

the use of CIBERSORT (http://cibersort.stanford.edu; v3.15.0) to estimate 22

immune cell proportions (P<0.05 was considered reliable). The

correlation between each hub gene and the 22 immune cell types was

tested using Spearman's rank correlation analysis and visualized as

lollipop plots. GSEA with KEGG analysis were used for functional

enrichment. Using the GSE70770 dataset, the immune infiltration

scores for 22 immune cell subsets were calculated via single-sample

GSEA (ssGSEA) implemented through the R package Gene Set Variation

Analysis (GSVA). Specifically, the GSVA package was used to run

ssGSEA, which quantifies the enrichment level of each immune

cell-associated gene set within individual samples of GSE70770,

thereby generating the immune infiltration scores for each cell

type. Paired t-tests were used to compare the immune scores of PCa

and adjacent tissues, visualized as box plots with R's ggplot2.

Immune cell composition was also plotted with R's ggplot2. Spearman

correlation tests of genes and immune cells were visualized as heat

maps using R's ComplexHeatmap (v1.0.12). To ensure the reliability

of the observed correlations across different computational tools,

R's psych package (v2.4.3) was used to compute correlation

coefficients and P-values of core DeMRGs and immune cells; box

plots showed the differences in the immune scores of high/low

expression (samples with expression levels greater than or equal to

the median were defined as the high expression subgroup, while

those with expression levels below the median were designated as

the low expression subgroup.) subgroups. Cluster analysis heat maps

(using the pheatmap v1.0.12 function in R) illustrated the

relationships between hub gene expression and immune cells. The

correlations between the 6 core genes and immune cells were

calculated using the R package Hmisc (v5.1–1).

Bioinformatics evaluation of the PCa

mitochondrial respiratory chain and mitochondrial metabolism

Using MitoCarta3.0 and TCGA-PRAD data, paired

t-tests were conducted to identify genes with significant

differences (P<0.05) in oxidative respiratory chain complexes in

cancer cells and adjacent tissues, visualized via R's ggplot2.

Genes that were |statistical|>6 were correlated with the

CIBERSORT immune infiltration results, with correlation heat maps

generated using ggplot2. Spearman rank analysis was conducted to

assess the correlations between the 6 hub genes and oxidative

respiratory chain complex genes (|statistical|>4); these

correlations were visualized using ggplot2. Linear regression was

used to evaluate the pairwise relationships between the 4 selected

hub genes and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) genes. R's ggplot2

(stat_compare_means) was used to perform paired t-tests to analyze

the expression of damage associated molecular patterns DAMPs genes

(such as BCL2 and calreticulin) and immune receptor-related genes

(such as toll-like receptor 2 and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase). Mantel

tests and Pearson correlations were used to calculate the

correlations between the 4 hub genes, mitochondrial metabolism and

DAMPs.

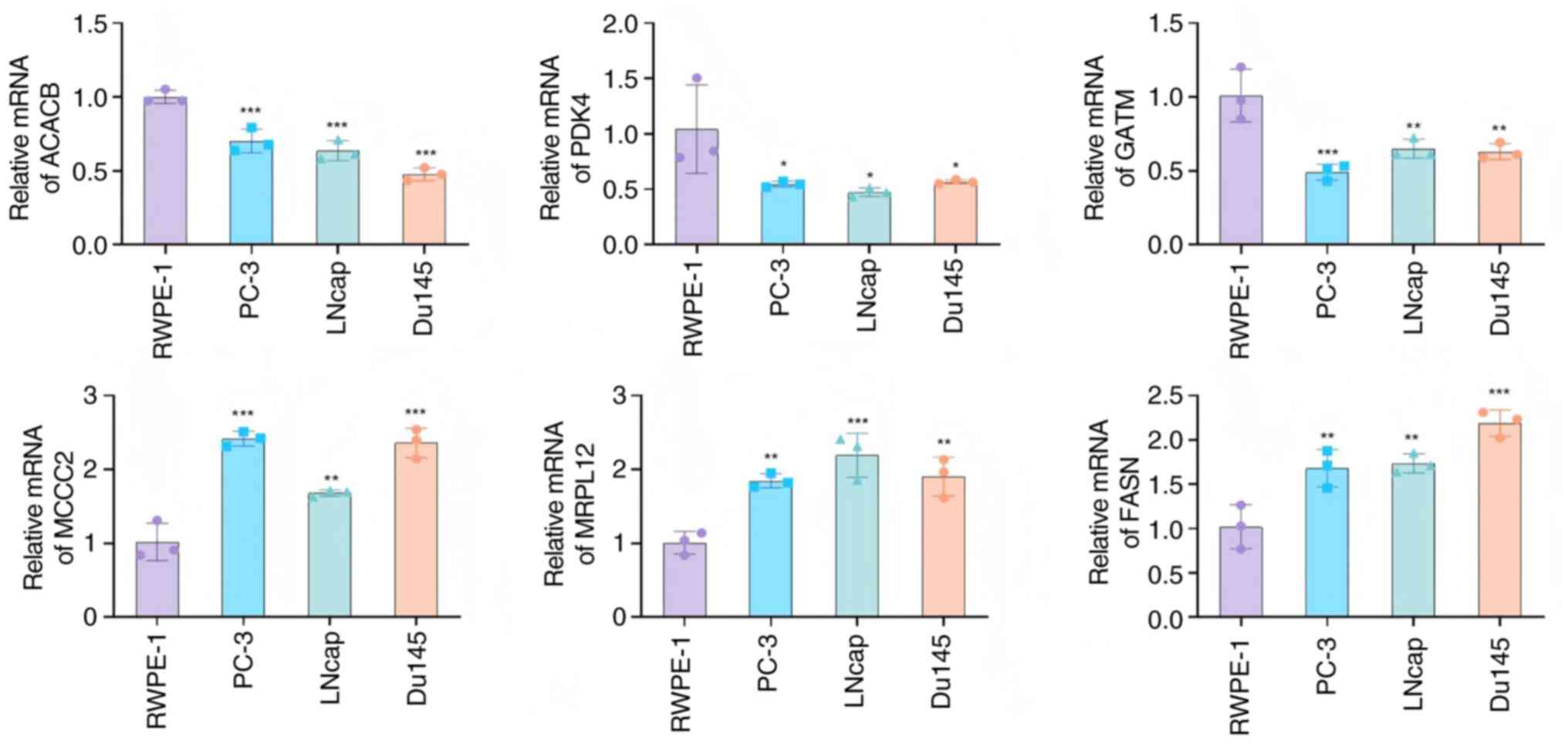

Statistical analyses

SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp.) was utilized to perform the

statistical analyses. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error

of the mean according to the results of three independent repeated

experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to

analyze differences in the expression levels of the 6 core DeMRGs

[acetyl-CoA carboxylase β (ACACB), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4

(PDK4), glycine amidinotransferase (GATM), methylcrotonyl-CoA

carboxylase subunit 2 (MCCC2), mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12

(MRPL12) and fatty acid synthase (FASN)] in the four different cell

lines, which were detected by RT-qPCR from three independent

repeated experiments. Following the one-way ANOVA, the Tukey's

honestly significant difference test was used as the post hoc test

to perform pairwise comparisons between groups, ensuring the

accurate identification of specific differences in gene expression

levels among different cell lines and between different genes.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

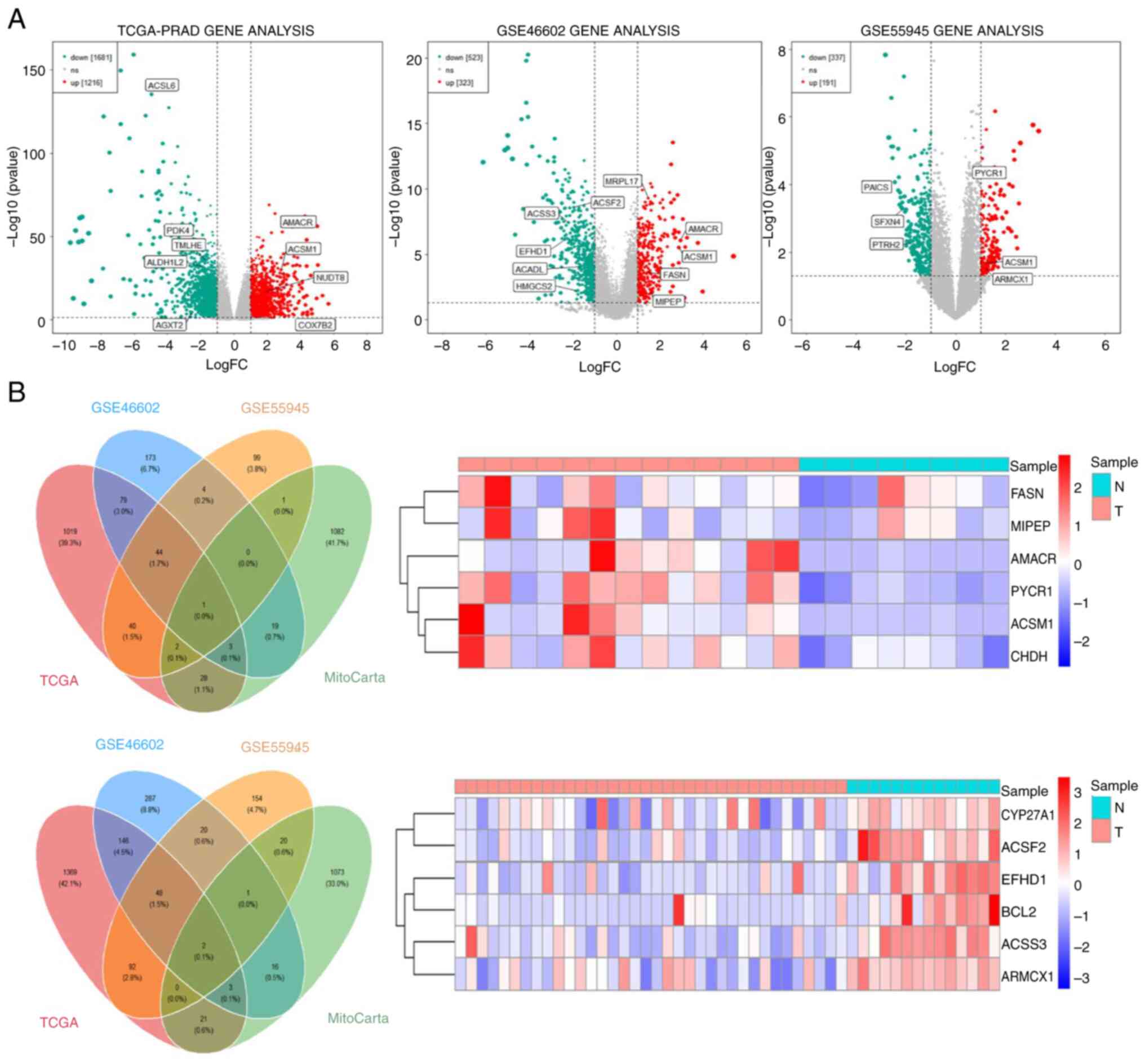

Identification of DeMRGs in PCa and

enrichment analyses

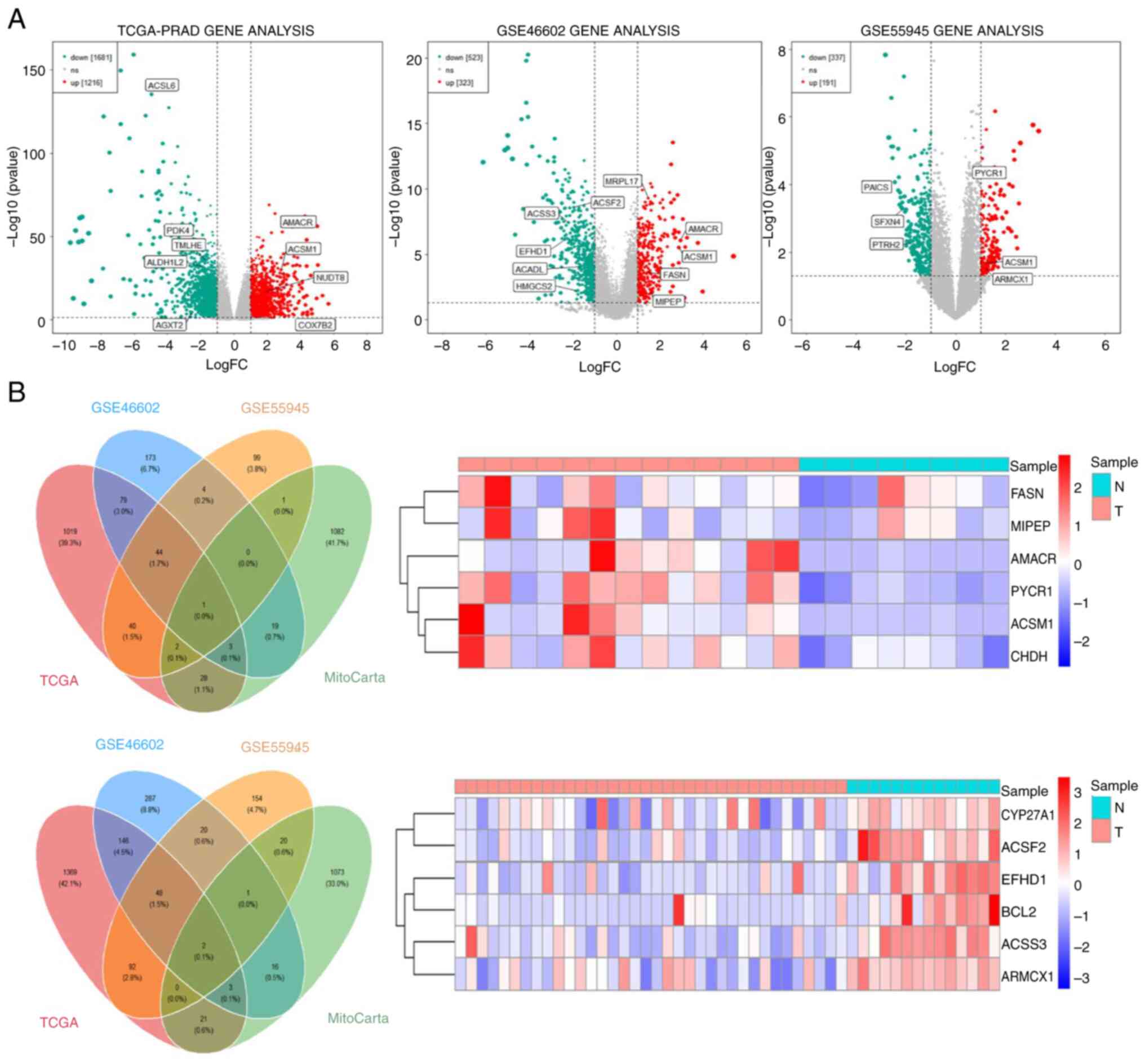

TCGA-PRAD contains RNA-seq data for 554 tissue

samples, including 502 cancer tissues and 52 adjacent tissues.

Differential analysis identified 1,681 genes that were

significantly downregulated and 1,216 genes that were significantly

upregulated in PCa. The DEGs were intersected with human

mitochondrial genes in the MitoCarta3.0 database to obtain 60

intersecting genes, including 34 significantly upregulated and 26

significantly downregulated genes. The top 9 DeMRGs are shown in

Fig. 1A. Similarly, 523 genes were

significantly downregulated and 323 genes were significantly

upregulated in PCa in GSE46606 and 337 genes were significantly

downregulated and 191 genes were significantly upregulated in PCa

in GSE55945. After taking the intersection of these DEGs with the

MitoCarta3.0 database, 23 significantly upregulated and 22

significantly downregulated genes were identified in GSE46602,

while 4 significantly upregulated and 23 significantly

downregulated genes were identified in GSE55945 (Fig. 1A). After conducting a differential

analysis using the training set (TCGA-PRAD, GSE 46606 and

GSE55945), To specifically screen for high-confidence upregulated

mitochondria-related genes in PCa, the upregulated subset of the

initially identified 60 DeMRGs (from intersecting general PCa DEGs

with MitoCarta3.0 mitochondrial genes) was further intersected with

the human mitochondrial genes in the MitoCarta3.0 database. This

targeted refinement yielded 6 core upregulated mitochondrial genes,

which were selected for subsequent functional and correlation

analyses. The 6 mitochondrial genes in GSE55945 and GSE46602 are

presented as heat maps (Fig.

1B).

| Figure 1.Differential expression of mRNA in

mitochondria between prostate cancer and normal prostate tissue.

(A) Differential analysis was conducted on three training sets

(TCGA-PRAD, GSE46602 and GSE55945). (B) The left sides are the Venn

diagram, and the right side is the expression heatmap. The top

images are for GSE55945 and the bottom images are for GSE46602;

TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; ns,

no significance; FASN, fatty acid synthase; MIPEP, mitochondrial

intermediate peptidase; AMACR, α-methylacyl-CoA racemase; PYCR1,

pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1; ACSM1, acyl-CoA synthetase

medium chain family member 1; CHDH, choline dehydrogenase; N,

normal; T, tumor; FC, fold change. |

GO analysis was performed on all significantly

upregulated DeMRGs (54 genes) in the three datasets, including in

terms of molecular function, biological process and cell component.

This analysis showed that the DeMRGs significantly upregulated in

PCa were related to ‘nucleotide phosphate metabolic process’,

‘oxidative phosphorylation’, ‘mitochondrial transport’,

‘mitochondrial transmembrane transport’ and ‘ribosomes’ (Fig. S1A). By contrast, the 63

significantly downregulated DeMRGs in PCa were associated with

‘small molecule catabolic process’, ‘organic acid biosynthetic

process’ and ‘mitochondrial gene expression’ (Fig. S1B).

Correlation analysis of core

genes

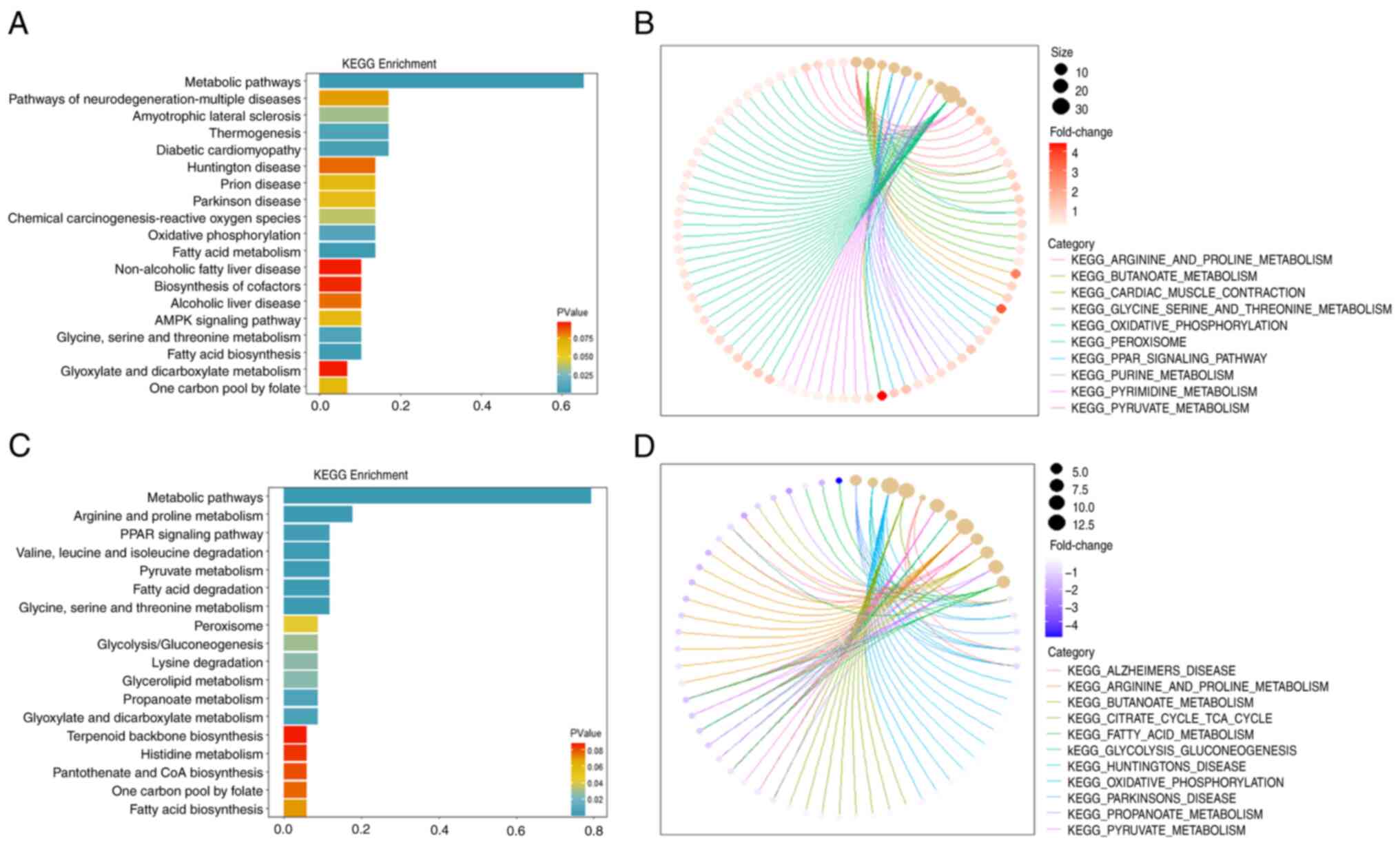

KEGG analysis and GSEA showed that the upregulated

DeMRGs were enriched in multiple metabolic pathways and were

associated with multiple diseases, including ‘Huntington’ disease’,

‘Parkinson disease’ and ‘prion diseases’ (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, the KEGG and

GSEA results showed that the downregulated DeMRGs were enriched in

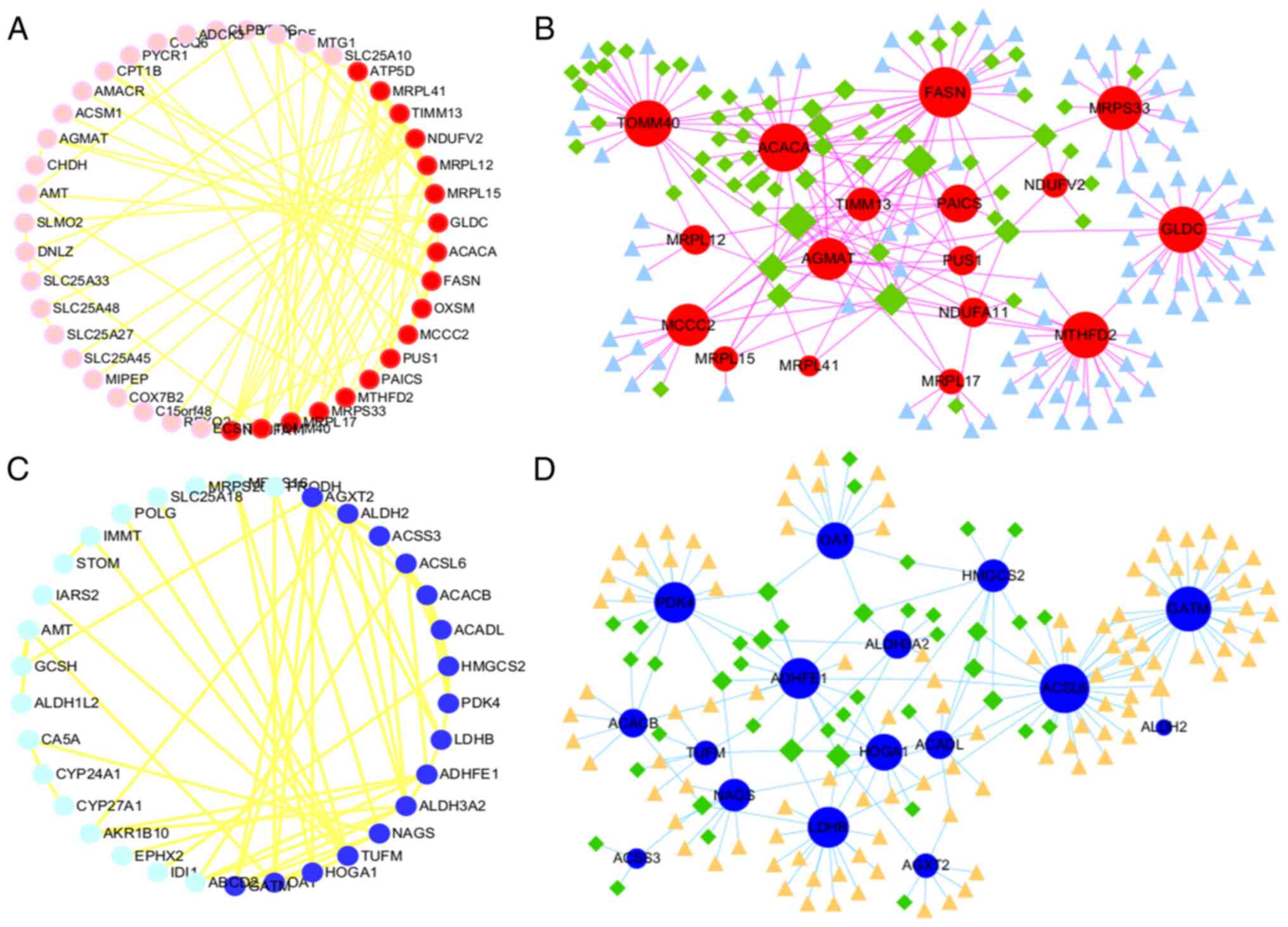

multiple metabolic pathways and ‘PPAR signaling pathway’ (Fig. 2C and D). A PPI network was

constructed using the STRING website to analyze the 54 upregulated

genes and Cytoscape analysis was used to screen out 18 core genes

with a degree value >4 (Fig.

3A). Subsequently, NetworkAnalyst 3.0 was used to predict the

transcription factors and interacting miRNAs of these 18 genes

(Fig. 3B). Similarly, the 63

downregulated genes were used to construct a PPI network through

the STRING website and 16 genes were screened out based on a degree

value >4 (Fig. 3C). The

predicted transcription factors and interacting miRNAs of these 16

genes were also screened out (Fig.

3D). The results collectively suggest that the core genes

selected in the present study are related to multiple transcription

factors and miRNAs.

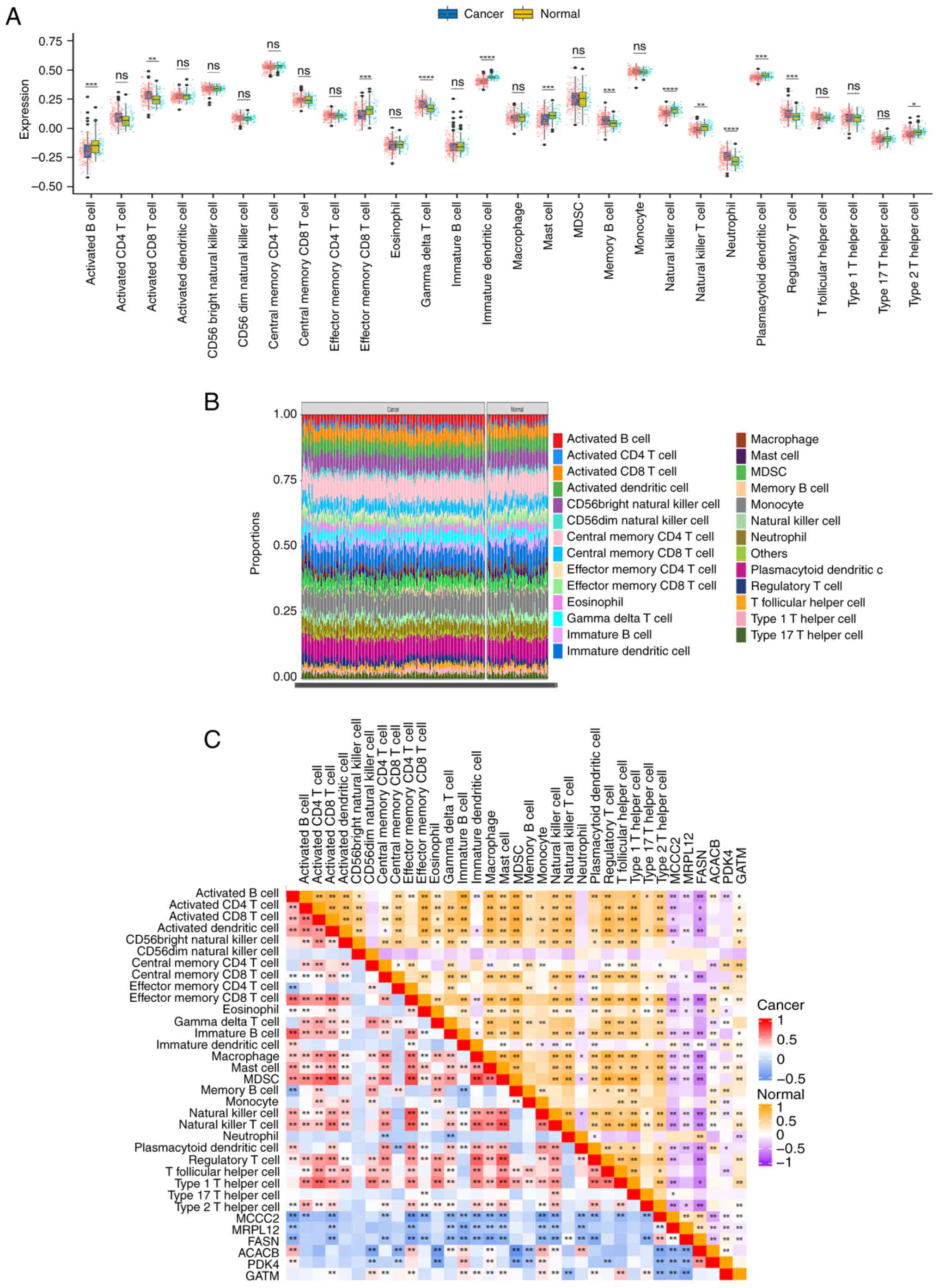

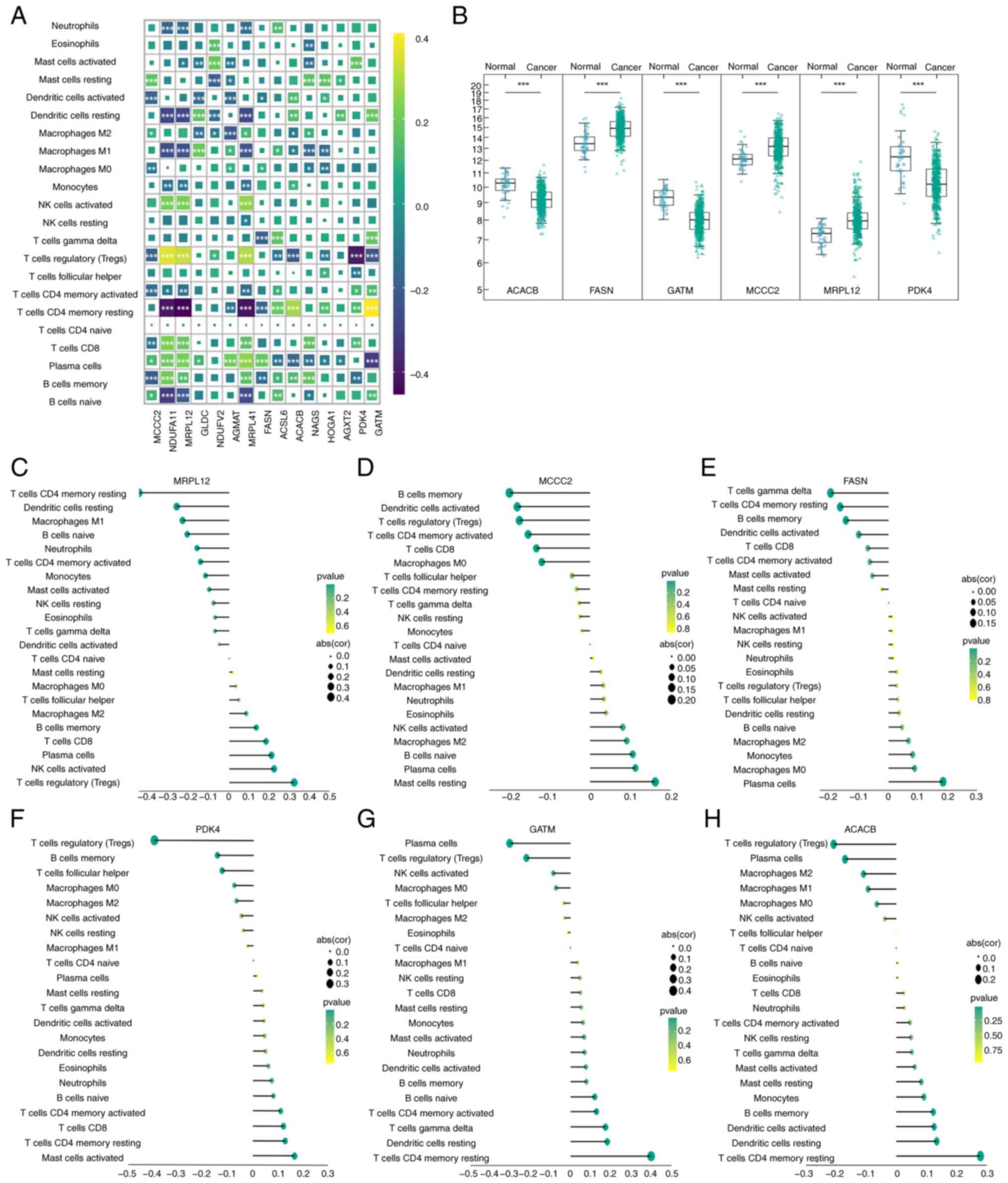

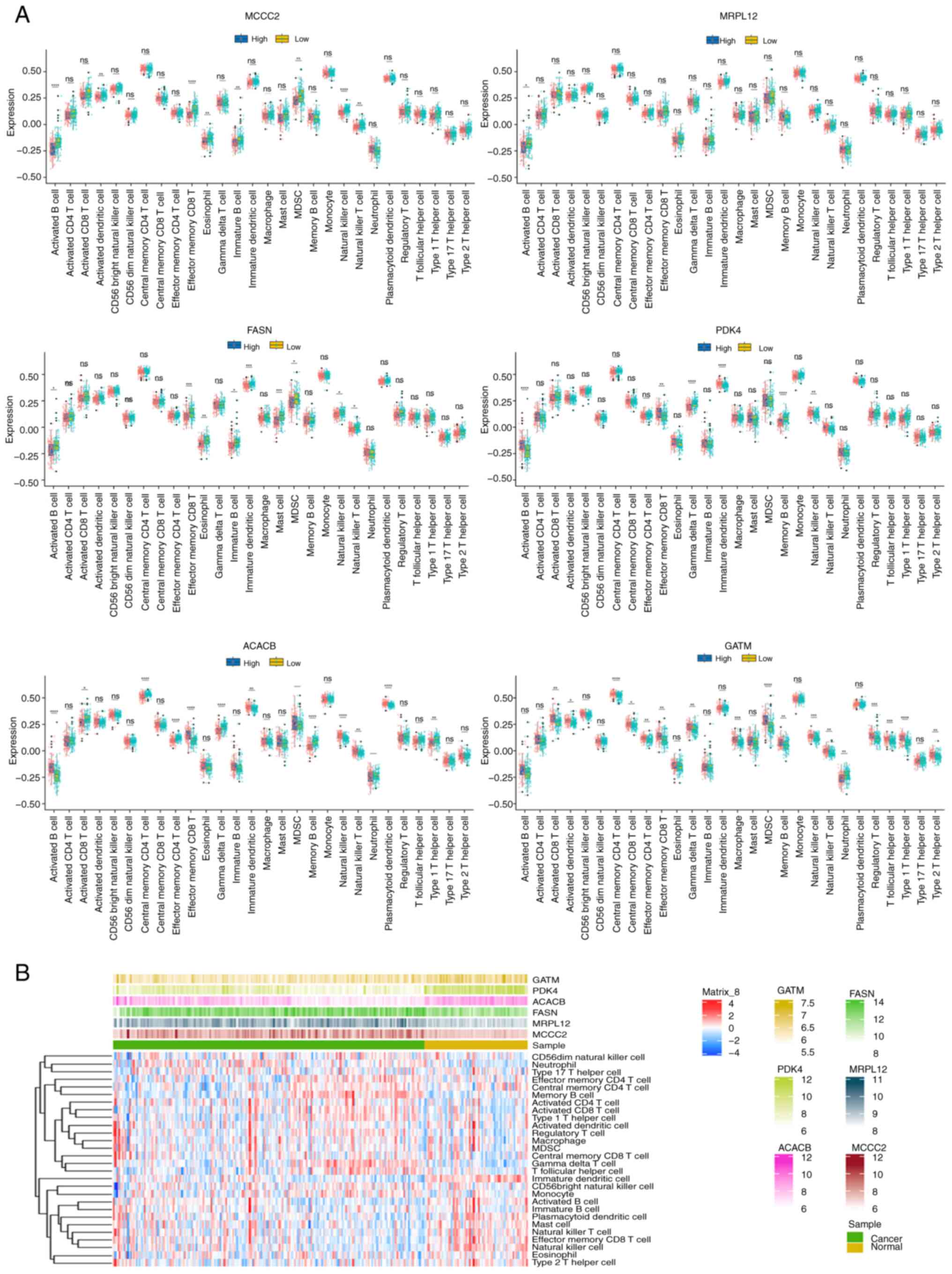

Correlation between core DeMRGs and

immune infiltration in PCa

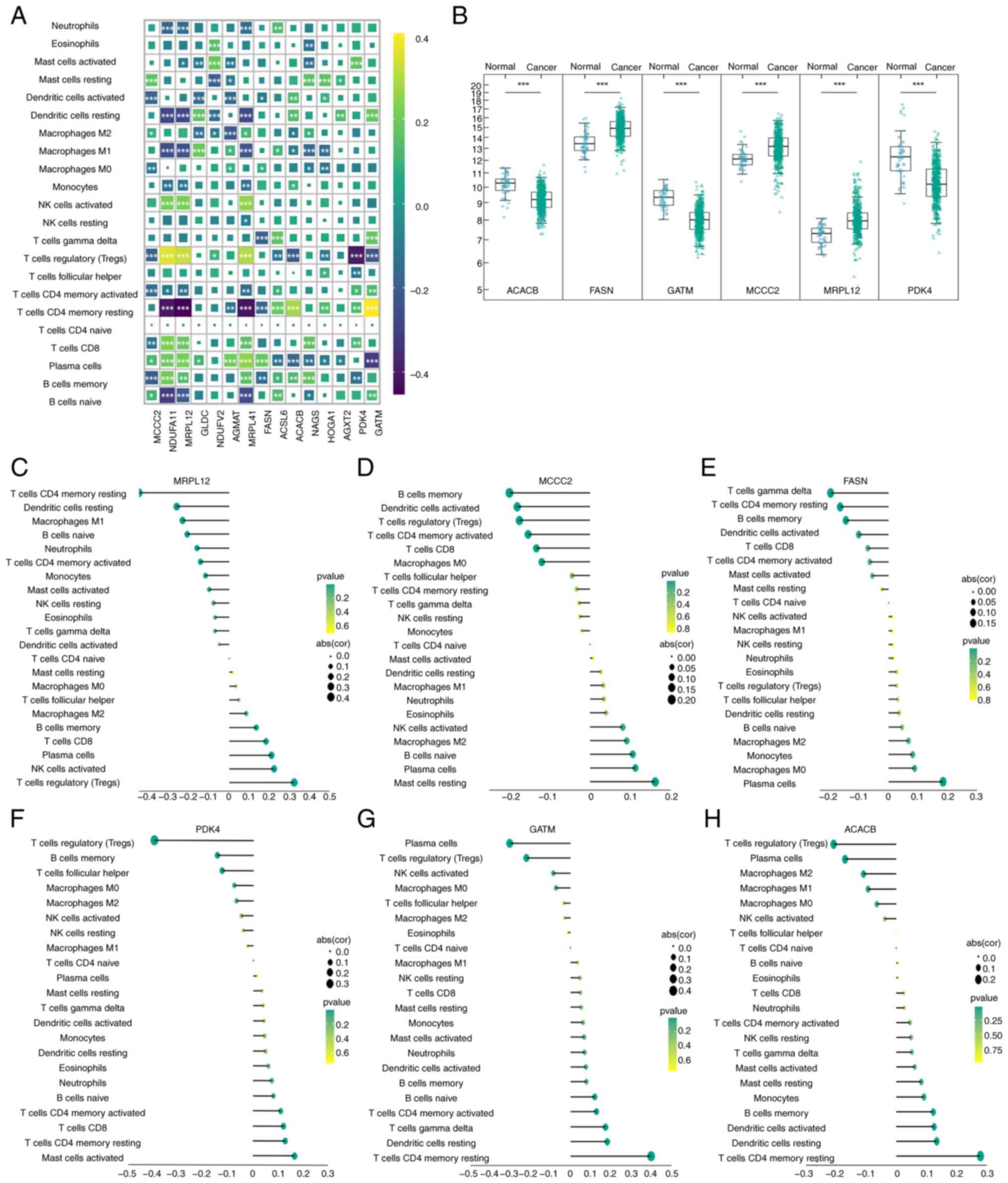

The TPM expression matrix of PCa tissue (502 cases)

was used to calculate its immune score using the CIBERSORT

deconvolution algorithm. The genes examined are the intersection of

the 60 DeMRGs in TCGA-PRAD and the 34 core upregulated genes

selected earlier, resulting in 15 intersection genes, which were

the core DeMRGs of TCGA-PRAD. Subsequently, using the TPM

expression matrix of PCa tissues (502 cases) from TCGA-PRAD

dataset, the proportions of 22 immune cell subsets were first

estimated via the CIBERSORT deconvolution algorithm to generate

immune infiltration profiles. On this basis, a correlation analysis

was further performed between these 15 intersection genes and the

aforementioned immune infiltration results (Fig. 4A). It can be observed that there are

significant differences in the positive and negative correlations

between different immune cells and specific genes. These

differences help to reveal the association between immune cell

functions and gene expression, and provide references for research

on tumor immune regulation, gene functions and other related

fields. The 6 genes most closely related to immunity were screened

out, as shown in Fig. 4B. The

differences in the expression of the 6 genes in PCa and adjacent

tissues were significant. ACACB, PDK4 and GATM were downregulated

in PCa, while MCCC2, MRPL12 and FASN were upregulated in PCa.

Lollipop plots of the 6 genes were constructed and the results

showed a significant negative correlation between MRPL12 and

quiescent CD4 memory T cells, memory B cells and M1 macrophage

infiltration, while the trend was the opposite for Tregs and

NK-activated cells (P<0.05; Fig

4C). MCCC2 was significantly negatively correlated with the

infiltration of memory B cells, activated dendritic cells and Tregs

cells, while the trend was the opposite for plasma cells and

stationary mast cells (P<0.05; Fig.

4D). A significant negative correlation was found between FASN

and γ-δ T cells, quiescent CD4 memory T cells and memory B cells,

while the opposite was found for plasma cells and M0 macrophages

(P<0.05; Fig. 4E). PDK4 was

significantly negatively correlated with Tregs, memory B cells and

follicular helper T cells, while it was positively correlated with

activated mast cells, resting CD4+ memory T cells and

CD8 T cells (Fig. 4F). GATM was

significantly negatively correlated with plasma cells and Tregs,

while it was positively correlated with resting CD4+

memory T cells, resting dendritic cells and γ-δ T cells (Fig. 4G). ACACB was significantly

negatively correlated with Tregs, plasma cells and M2 macrophages,

while it was positively correlated with resting CD4+

memory T cells, resting dendritic cells and activated dendritic

cells (Fig. 4H). Subsequently, a

single-gene GSEA was conducted; the results showed that MCCC2,

MRPL12 and FASN were negatively correlated with ‘KEGG_APOPTOSIS’,

‘KEGG_B_CELL_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY’ and

‘KEGG_INTESINAL_IMMUNE_NETWORK_FOR_IGA_PRODUCTION’. However, ACACB,

PDK4 and GATM showed the opposite results (Fig. S2). These results imply a close

association between the core DeMRGs and infiltrating immune

cells.

| Figure 4.Relationship between core

differential mitochondrial mRNA and tumor immune infiltration in

PCa and normal prostate tissue. (A) TCGA-PRAD dataset was used to

calculate the immune score of the transcripts per million

expression matrix of PCa tissue (502 cases), which is shown as a

heatmap. The genes on the x-axis are the core genes selected from

TCGA-PRAD. The color of the heatmap represents the correlation

coefficient. The larger the box is, the more statistically

significant the correlation. (B) The box plot shows the 6 genes

most closely related to immunity, with P-values determined by

paired t-test. The R package ggplot2 was used to examine the

correlation between hub genes and immune cells, with the results

presented as lollipop plots. The relationship between (C) MRPL12,

(D) MCCC2, (E) FASN, (F) PDK4, (G) GTAM and (H) ACACB with immune

cell infiltration. The size of the points represents the absolute

value of the correlation coefficient and the larger the points, the

more correlated they are. The greener the point, the smaller the

P-value. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. PCa, prostate

cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; PRAD, prostate

adenocarcinoma; ACACB, acetyl-CoA carboxylase β; PDK4, pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinase 4; GATM, glycine amidinotransferase; MCCC2,

methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit 2; MRPL12, mitochondrial

ribosomal protein L12; FASN, fatty acid synthase. |

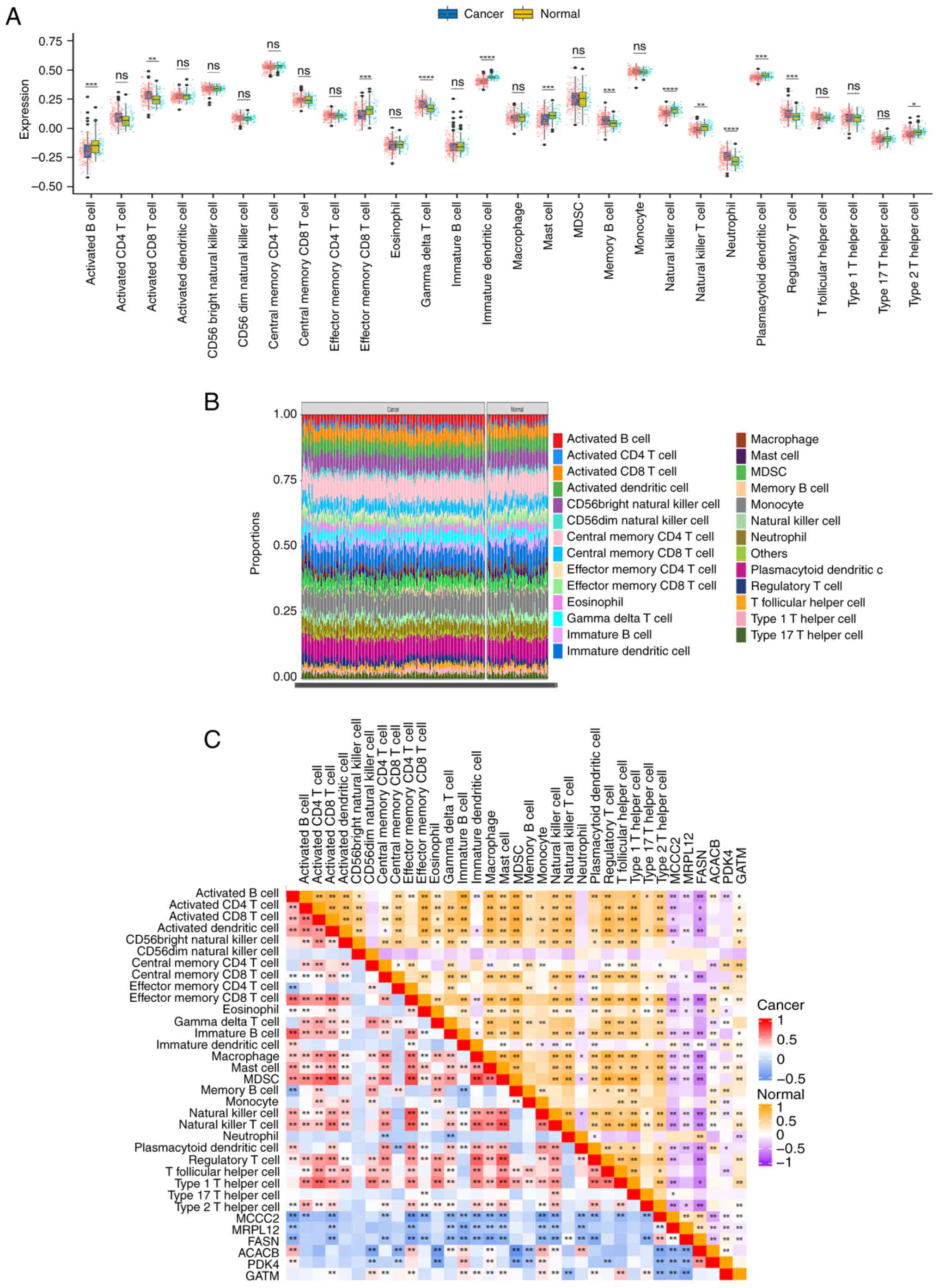

Validation of the correlation between

the 6 characteristic genes and immune cell infiltration

GSE70770 was used for validation, which included a

total of 293 tissue samples: 220 PCa tissues and 73 adjacent cancer

samples. The results showed that in PCa, the 6 genes were

significantly downregulated in activated B cells, effector CD8

memory T cells, immature dendritic cells, mast cells and NK cells

of PCa tissues compared with the adjacent cancer tissues (Fig. 5A). Next, the proportion of 26 immune

cells in PCa and adjacent tissues were analyzed using the GSE70770

dataset (Fig. 5B). There were

significant stratified differences in the proportions of different

types of immune cells (such as activated B cells, activated CD4/CD8

T cells, macrophages and neutrophils) between the two types of

tissues. These observed differences are suggestive of immune cell

remodeling within the tumor microenvironment, thereby providing

critical insights that hold value for investigating the molecular

mechanisms underlying tumor immune escape and identifying candidate

targets for immune-based therapeutic interventions. The correlation

between the 6 core genes and immune cells were calculated using the

Hmisc R package and displayed it in the form of a heat map

(Fig. 5C). The results showed that

these genes were correlated (P<0.001) with NK cells, NK-T cells,

B cells, dendritic cells, mast cells and CD8 memory T cells. The

correlation coefficients and P-values for these 6 genes and the

immune cells were calculated separately. The results showed that

high expression of MCCC2, MRPL12 and FASN was associated with low

expression of activated B cells, CD8 memory T cells, NK cells and

NK-T cells. In addition, low expression of PDK4, ACACB and GATM was

associated with low expression of activated B cells, CD8 memory T

cells, NK cells and NK-T cells; the strongest immune correlation

was with GATM (Fig. 6A). A heat map

was used to visually display the differences between cancer and the

adjacent immune cells, as well as the relationship between the

expression levels of these 6 core genes and immune cells. The

results showed that with low expression of PDK4 and GATM, memory B

cells and CD4 memory T cells were highly expressed, while CD8

memory T cells showed lower expression levels (Fig. 6B).

| Figure 5.Validation of the relationship

between MCCC2, MRPL12, FASN, PDK4, ACACB and GATM genes and tumor

immunity in prostate cancer and normal prostate tissue. (A)

Validation of the relationship between the MCCC2, MRPL12, FASN,

PDK4, ACACB and GATM genes and tumor immunity in PCa and normal

prostate tissue. The data is sourced from the validation dataset

GSE70770. (B) The proportion of 26 immune cells in PCa and adjacent

tissues in the validation dataset GSE70770. (C) The correlation

between 6 core genes and immune cells in the validation dataset

GSE70770. The darker the color, the stronger the correlation. The

upper right corner shows the correlation between these genes and

immune cells, while the lower left corner shows the correlation

between these genes and immune cells in PCa. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. ACACB, acetyl-CoA

carboxylase β; PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; GATM, glycine

amidinotransferase; MCCC2, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit

2; MRPL12, mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12; FASN, fatty acid

synthase; PCa, prostate cancer. |

| Figure 6.Validation of the relationship

between the MCCC2, MRPL12, FASN, PDK4, ACACB and GATMM genes and

immune cells in prostate cancer and normal prostate tissue. (A) The

relationship between the core MCCC2, MRPL12, FASN, PDK4, ACACB and

GATMM genes and immune cells, using the validation dataset

GSE70770. (B) The differences between cancer and adjacent immune

cells, as well as the relationship between the expression levels of

the 6 core genes and immune cells, using the validation dataset

GSE70770. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001.

ns, no significance; ACACB, acetyl-CoA carboxylase β; PDK4,

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; GATM, glycine amidinotransferase;

MCCC2, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit 2; MRPL12,

mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12; FASN, fatty acid synthase. |

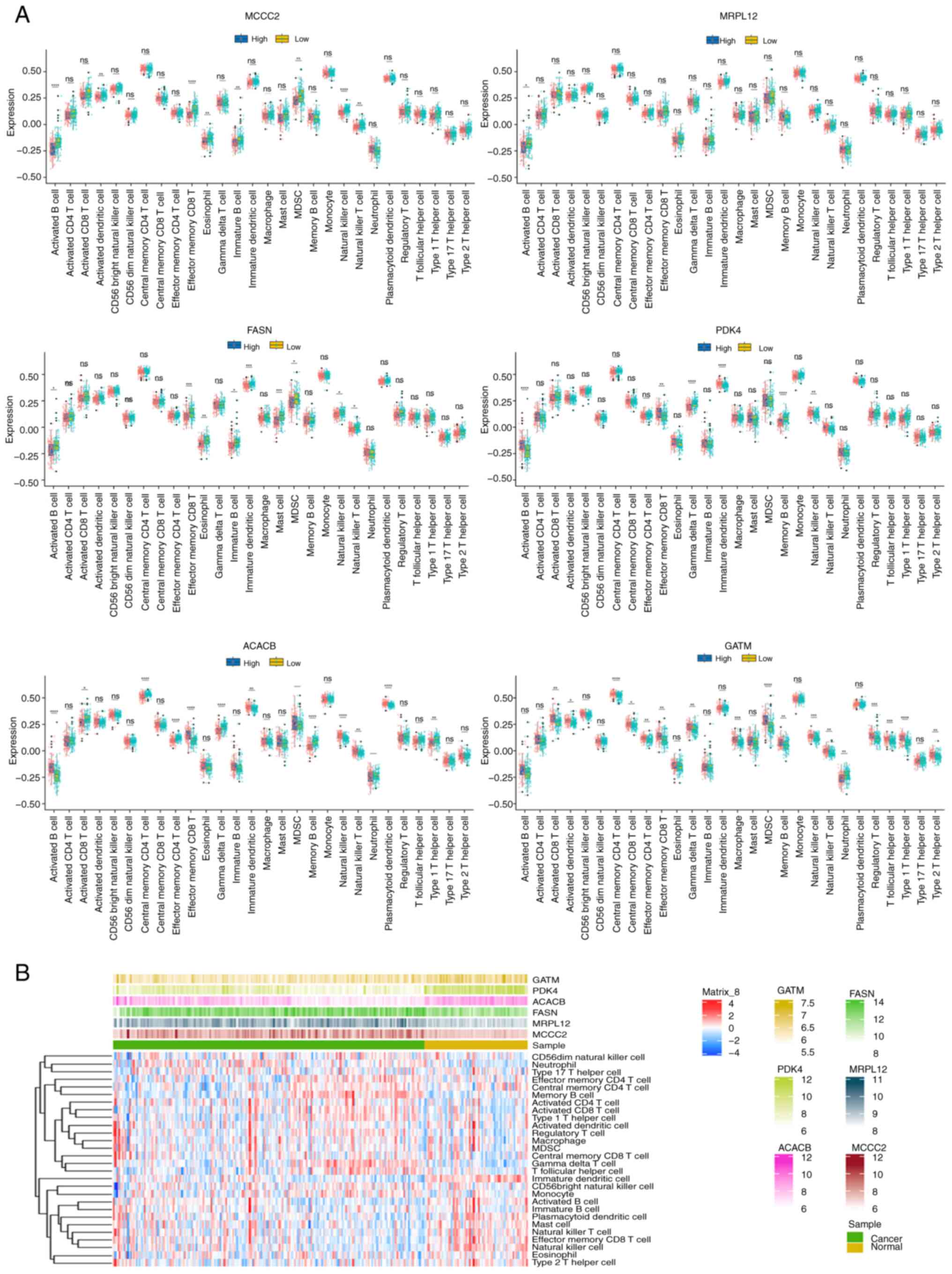

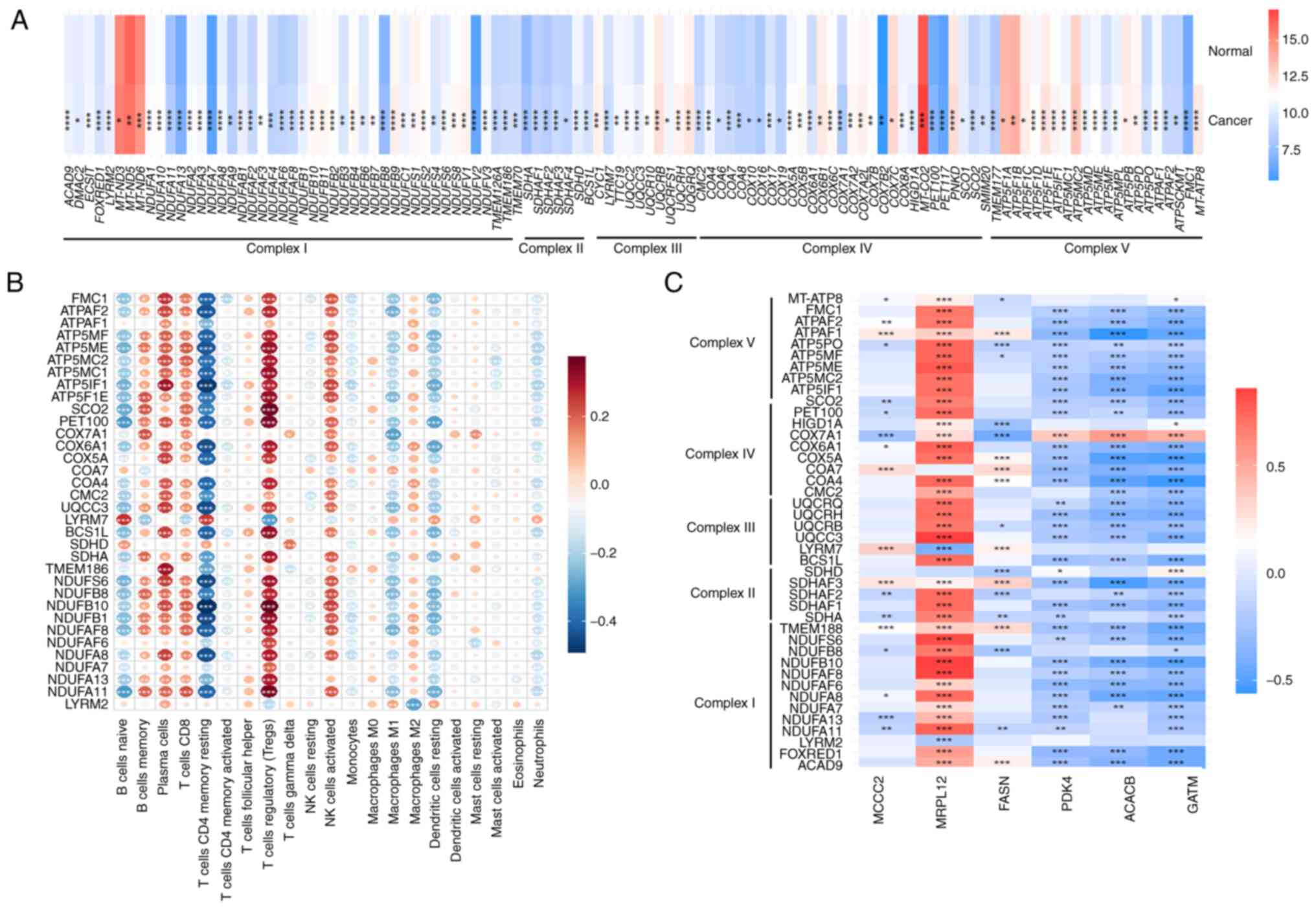

Relationship between the 6 core genes,

mitochondrial respiration and PCa progression

Next, the TCGA-PRAD dataset was used to study the

relationship between mitochondrial respiration and PCa as well as

its relationship with the 6 core genes and selected statistically

significant genes (P<0.05; Fig.

7A). Genes such as COX10, COX11 and COX14 were upregulated,

while genes such as FOXRED1, AGOX3 and FMC1 showed a downward

trend. Genes with |statistical|>6 were selected and their

correlation with immune infiltrating cells was calculated using

CIBERSORT. The results showed that these mitochondrial respiratory

chain genes were negatively correlated with resting CD4 memory T

cells and positively correlated with Tregs (Fig. 7B). Using the TCGA-PRAD dataset, the

correlation between the 6 core genes and mitochondrial respiratory

chain genes (|statistical|>4) was calculated. The results showed

that MRPL12, PDK4, ACACB and GATM had the strongest correlation

with mitochondrial respiration, and these 4 genes were selected as

hub genes (Fig. 7C). The 6

mitochondrial respiratory chain genes most closely related to these

4 hub genes were then selected and a linear regression scatter plot

was created. The results showed that MRPL12 was significantly

positively correlated with TMEM186, UQCC3, COX7A1 and ATPAF1

(Fig. S3A), while PDK4, ACACB and

GATM were positively correlated with COX7A1 and negatively

correlated with TMEMI186, SDHAF3, UQCC3, COA7 and ATPAF1 (Fig. S3B-D). These results suggest that

the core differential genes related to mitochondrial respiration

are closely related to immune infiltrating cells in PCa.

| Figure 7.Relationship between mitochondrial

respiration and prostate cancer. (A) Relationship between

mitochondrial respiration and prostate cancer, as well as the

relationship with 6 core genes. The dataset used is TCGA-PRAD. The

genes of the five stages of mitochondrial respiration were provided

by the MitoCarta 3.0 database, and statistically significant genes

were screened out; (B) Using the TCGA-PRAD dataset, genes with

|statistical|>6 from (A) were selected and the correlation

between these genes and CIBERSORT immune infiltrating cells was

calculated. (C) Using the TCGA-PRAD dataset, the correlation

between the 6 core genes and mitochondrial respiratory chain genes

(|statistical|>4) was calculated. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; ACACB, acetyl-CoA carboxylase β;

PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; GATM, glycine

amidinotransferase; MCCC2, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit

2; MRPL12, mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12; FASN, fatty acid

synthase; |

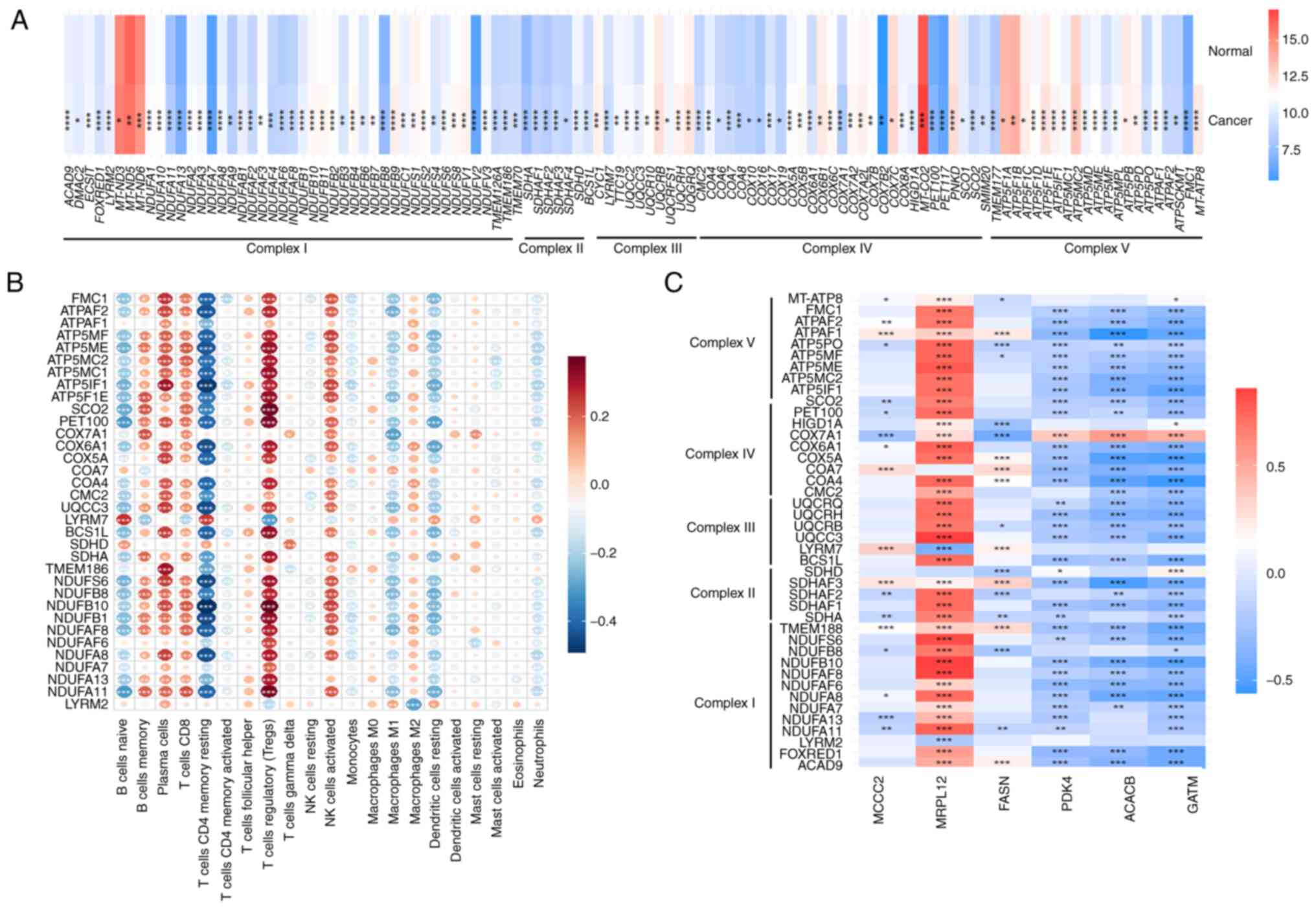

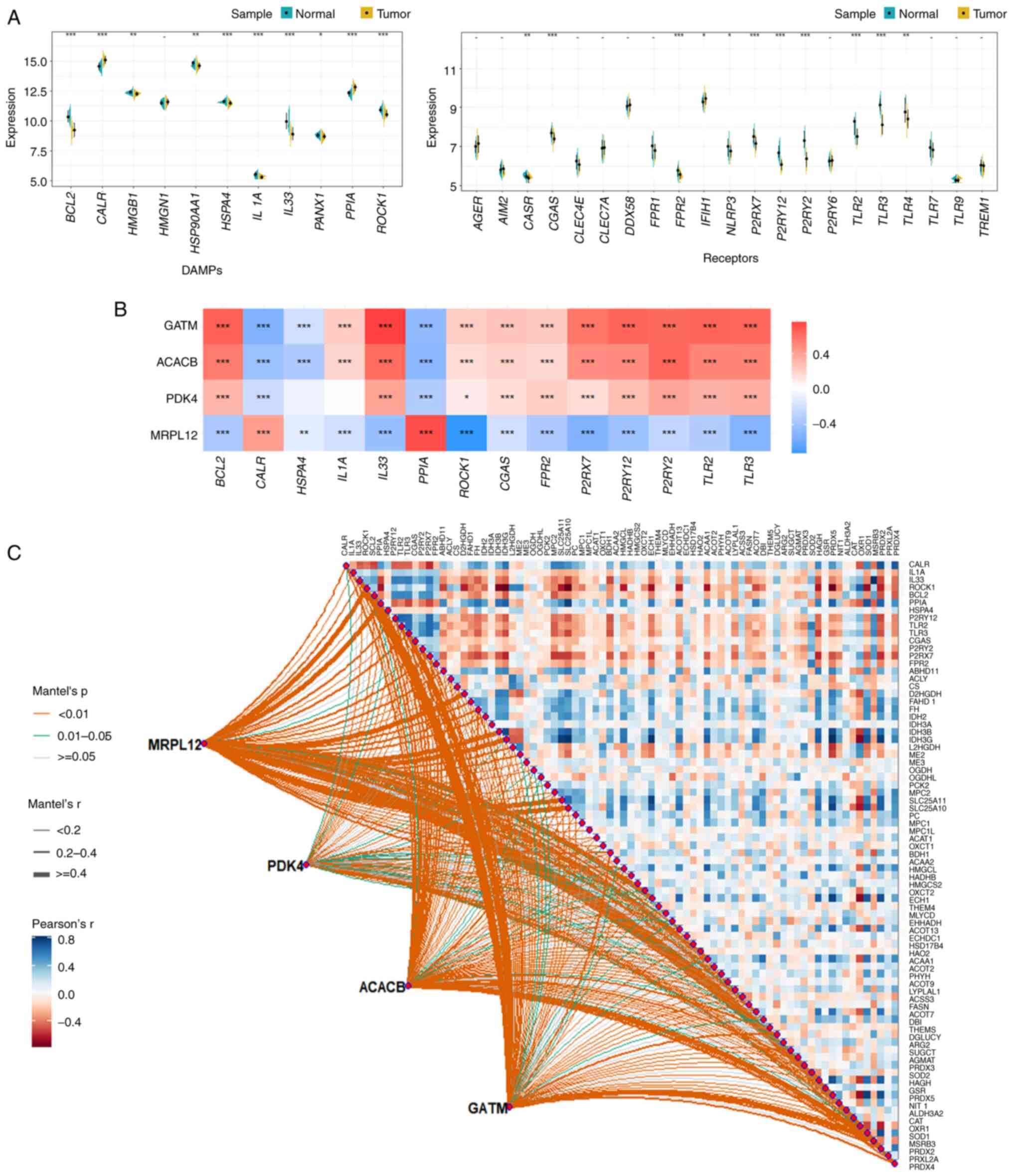

Potential association of hub genes

with DAMPs and mitochondrial metabolism

The TCGA-PRAD dataset was then used to create violin

plots to determine the differences between DAMP-related genes (11

genes) and immune receptor-related genes (21 genes) in PCa and

adjacent tissues. Genes with significant differences were selected

for further research (P<0.001; Fig.

8A). An analysis of the correlation between the 4 hub genes and

significantly different DAMP-related genes and immune receptors

showed that they have a strong correlation (Fig. 8B). To further investigate the

potential correlation between the 4 hub genes (MRPL12, PDK4, ACACB

and GATM) and DAMPs and mitochondrial metabolism, the Mantel test

was used to analyze statistical significance. The results showed

that they were closely related to the mitochondrial metabolic

pathways in gluconeogenesis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and

pyruvate/ketone/lipid/amino acid metabolism in PCa (Fig. 8C).

| Figure 8.Potential correlation between 4 hub

genes (MRPL12, PDK4, ACACB and GATM) and immune receptors and

mitochondrial metabolism. (A) Using the TCGA-PRAD dataset, the

differences between DAMP-related genes (11) and immune receptor-related genes

(21) in PCa and adjacent tissues

were detected; the genes with significant differences

(**P<0.001) were selected for further study. (B) The correlation

between the 4 hub genes and the significant differences in

DAMP-related genes and immune receptors selected in (a). (C)

Further investigation of the potential correlation between the 4

hub genes and DAMPs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. PRAD,

prostate adenocarcinoma; ACACB, acetyl-CoA carboxylase β; PDK4,

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; GATM, glycine amidinotransferase;

MCCC2, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit 2; MRPL12,

mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12; FASN, fatty acid synthase;

TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas. |

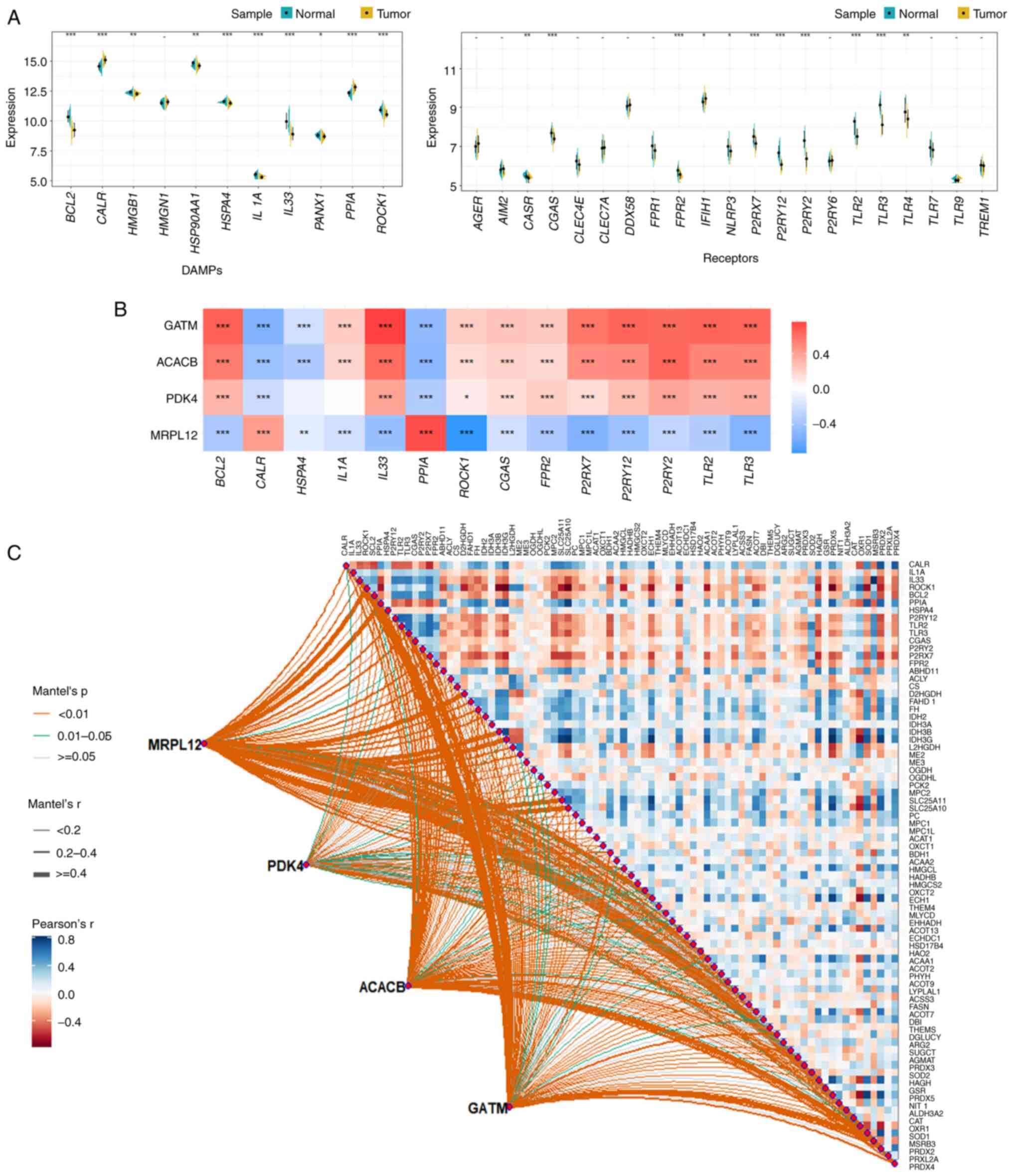

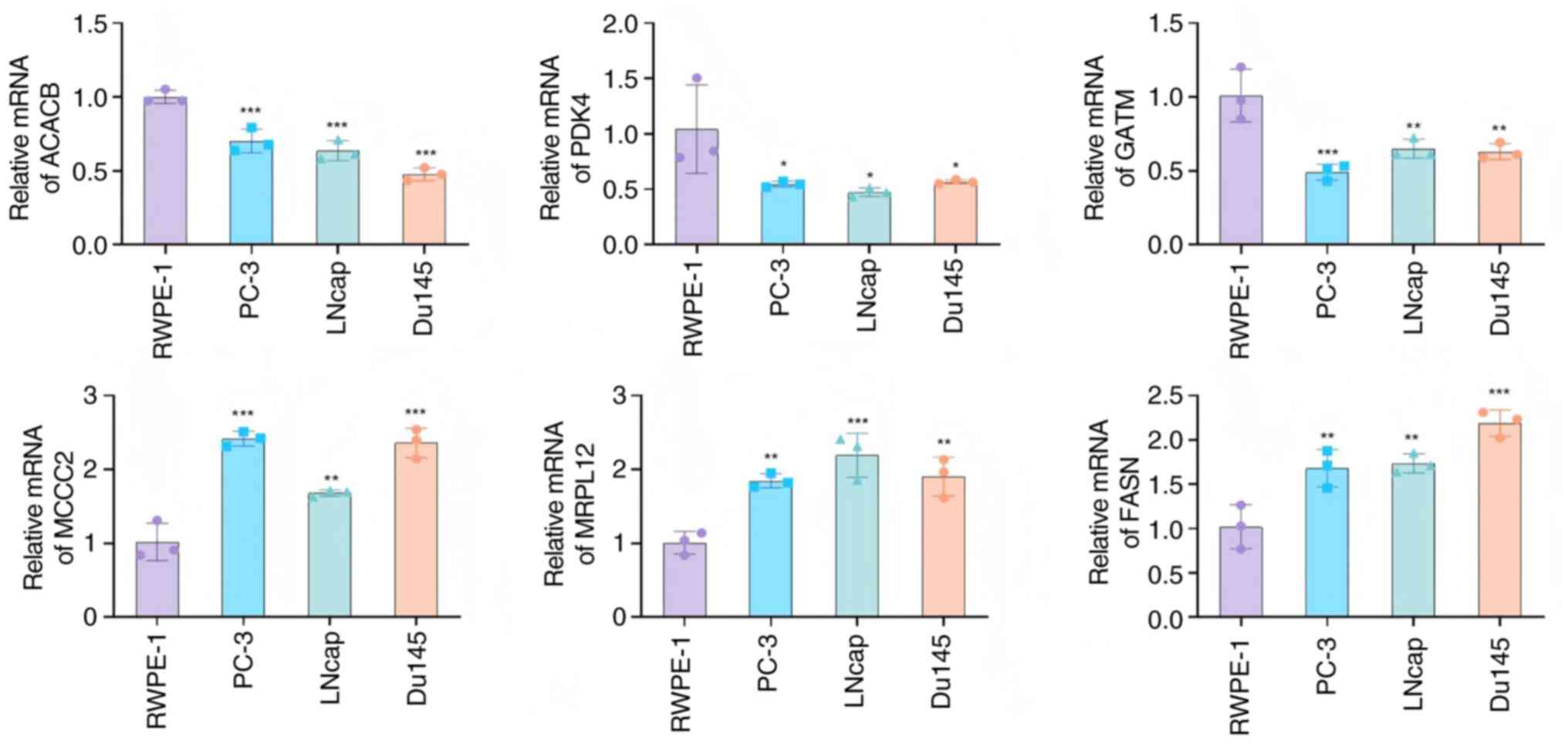

Validating expression levels of

DeMRGs

Finally, expression of the core genes was validated

using the RWPE-1 (the non-PCa cell line used for comparison), PC-3,

LNcap and Du145 cell lines. The results showed that ACACB, PDK4 and

GATM were downregulated in PCa, while MCCC2, MRPL12 and FASN were

upregulated in PCa, consistent with the bioinformatics analysis

(Fig. 9).

| Figure 9.RT-qPCR validation of the core genes.

Relative RNA levels of ACACB, PDK4, GATM, MCCC2, MRPL12 and FASN

were determined by the RT-qPCR for the RWPE-1, PC-3, LNcap and

Du145 cell lines. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; n=3.

RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; ACACB, acetyl-CoA

carboxylase β; PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4; GATM, glycine

amidinotransferase; MCCC2, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit

2; MRPL12, mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12; FASN, fatty acid

synthase. |

Discussion

Mitochondria are the ‘power factories’ in cells,

providing 80% of the energy required for cellular life activities.

Mitochondria play an important role in maintaining normal

physiological metabolism and body development and are involved in

the occurrence and development of various diseases (such as breast

cancer and renal cell carcinoma) (19). Variations in mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) sequences are common in certain tumors (such as ovarian

cancer, oncocytoma and prostate cancer). Two types of mtDNA cancer

variants can be identified: Novel mutations as oncogenic inducers

and functional variants as adaptors, allowing cancer cells to grow

in different environments. These mtDNA variants come from three

sources: Familial variants, somatic mutations produced within each

cell or individual and variants associated with ancient mtDNA

lineages (haplotypes) that are considered to adapt to constantly

changing tissues or geographical environments (20,21).

In addition to mtDNA sequence mutations, mtDNA copy number and

mtDNA sequence transfer to the nucleus may also lead to certain

cancer types [such as breast epithelial cell lines, patient-derived

xenograft models of triple-negative breast cancer and high-grade

serous ovarian cancer (HGSC) and primary HGSC tumors] (22). There is a strong functional

correlation between mtDNA mutations in eosinophilic tumors and PCa

(21). In PCa, significant changes

occur in the mitochondrial membrane, leading to the increased

uptake of integrated membrane proteins. This process leads to

increased rigidity and higher enzyme activity of cancer cell

mitochondria (23). NKX3.1 is

expressed in the prostate epithelium and its function is to protect

the prostate from damage and inflammation as well as maintain the

luminal prostate stem cells. In addition, it can regulate the

expression of mitochondrial genes to promote mitochondrial

homeostasis and prevent the occurrence of PCa (24).

Mitochondrial changes have a significant impact on

the phenotype of prostate tumor cells. First, the progression of

PCa is accompanied by an increase in ROS, which promotes its

invasiveness. During the transformation and later stages of PCa

development, PCa cells increase their mitochondrial respiration and

glycolytic rates to meet energy needs. Due to enhanced

mitochondrial respiration, ROS levels increase, inducing signaling

pathways related to PCa growth and survival (25–27).

Mitochondrial respiration and metabolism are related to PCa, while

normal prostate epithelial cells are highly dependent on glycolysis

and produce citrate from glucose. TCA cycle cannot effectively

produce a large amount of citrate. During the transformation

process, PCa cells gradually reactivate OXPHOS, increase glucose

metabolism and reduce citrate production. In addition, the late

stages of PCa are marked by an increase in TCA cycle and citrate

levels, which are used by cancer cells for biomolecular synthesis

to support their growth (28).

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) provides enhanced migration

and invasion capabilities for cancer cells, promoting tumor

dissemination and metastasis. A study has shown that the

downregulation of mitochondrial proteins involved in OXPHOS is

associated with increased EMT and invasive disease characteristics

(29). The changes in mitochondrial

gene expression are also related to the growth, survival and drug

resistance of PCa. Previous research has found that mitochondrial

fission factor and dynamic related protein-1 are amplified in

castration-resistant PCa, leading to low patient survival rates

(29). In addition to serving as a

power source for cells, mitochondria also play an important role in

cell death pathways, such as apoptosis. Mitochondria are crucial in

the activation of cell apoptosis through intrinsic pathways in

response to excessive oxidative stress and DNA damage (30,31).

Higher expression of Bcl-x is associated with higher-grade PCa

tumors, as well as the presence of lymph node metastasis and

distant metastasis. Given that Bcl-x is a key regulator of

mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis, these findings further indicate

that mitochondria play an important role in PCa immune escape

(32,33).

In PCa, ARs reprogram the entire cellular metabolic

pathway, including aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial

respiration, as well as de novo fat generation, to support

the metabolic and biosynthetic needs of PCa cells (34,35).

The m6A-mediated circular RNA (circ)RBM33-FMR1 complex can activate

mitochondrial metabolism by stabilizing pyruvate dehydrogenase E1

subunit α1 mRNA, thereby promoting the progression of PCa and

reducing the arylsulfatase family member I efficacy of circRBM33 in

PCa treatment (36). Treatment

targeting mitochondria may help with PCa as the naturally occurring

amino acid 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) immediately enhances

mitochondrial ROS production after exposure to IR and reduces

mitochondrial membrane potential by increasing intracellular PpIX

(the metabolite of 5-ALA) in PC-3 and DU-145 PCA cell lines. IR is

accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction induced by 5-ALA and an

increase in ATP production, which switches energy metabolism to a

quiescent state. Under hypoxic conditions, IR induces ROS burst and

mitochondrial dysfunction with 5-ALA to reduce cancer stemness and

radiation resistance (37). RNA

polymerase mitochondria (POLRMT) are crucial for mitochondrial

transcription mechanisms and other mitochondrial functions.

Upregulated POLRMT is important for PCa cell growth and

mitochondrial POLRMT may serve as a target for PCa treatment

(38).

In the present study, MRPL12, PDK4, ACACB and GATM

were identified as hub genes. MRPL12 is a core component of the

mitochondrial ribosome (mitoribosome), which is essential for

synthesizing proteins encoded by mtDNA, including key subunits of

the OXPHOS complex (39). In

hepatocellular carcinoma, MRPL12 is upregulated via the

PI3K/mTOR/YY1 pathway, which enhances OXPHOS and mitochondrial DNA

content, thereby driving malignant phenotypes (39). PDK4 is a gene involved in fatty acid

metabolism. Together with ACACB, FABP3 and other genes, it

constitutes a metabolic gene signature for prostate cancer. By

inhibiting the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, PDK4

promotes glycolysis and suppresses OXPHOS, thereby supporting the

Warburg effect in tumors (40).

Following androgen receptor inhibition, PCa cells switch to a

dependence on mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, and PDK4 may play

a regulatory role in this process (41). ACACB is a rate-limiting enzyme in

fatty acid synthesis and is involved in lipid metabolic

reprogramming in prostate cancer. As a member of the same 5-gene

metabolic signature as PDK4, its low expression is associated with

high-risk PCa (40). Dysregulated

lipid metabolism may promote immune evasion by altering the

function of immune cells (such as CD8+ T cells) in the

tumor microenvironment (42). GATM

is involved in creatine synthesis, and its expression is associated

with the MYC pathway and OXPHOS. In PCa, high GATM expression may

lead to mitochondrial dysfunction (such as reduced aspartate

levels), driving metabolic shifts toward glycolysis (43).

Despite the novel findings regarding mitochondrial

hub genes in PCa, the present study has several limitations that

should be acknowledged. First, the identification and validation of

DeMRGs and hub genes relied heavily on publicly available datasets

(TCGA-PRAD, GSE46602, GSE55945 and GSE70770) and in vitro

experiments using established PCa cell lines (Du145, PC-3 and

LNcap) and a normal prostate epithelial cell line (RWPE-1). The

lack of primary PCa tissue samples from a patient cohort (such as

clinical specimens with detailed pathological staging, treatment

history and long-term follow-up data) limits the generalizability

of the results to diverse clinical populations, as public datasets

may have inherent biases in sample selection and data

standardization. Second, the functional validation of the four hub

genes (MRPL12, PDK4, ACACB and GATM) was limited to correlative

analyses (such as associations with immune cell infiltration,

mitochondrial respiration and metabolic pathways) and gene

expression verification via RT-qPCR. No in-depth mechanistic

experiments were performed to elucidate the direct roles of these

hub genes in PCa progression, for instance,

gain-of-function/loss-of-function assays (such as overexpression

plasmids, small interfering RNA or CRISPR-Cas9) to assess changes

in PCa cell proliferation, migration, invasion or mitochondrial

function (such as mitochondrial membrane potential, ROS production

and ATP levels) were not conducted. Additionally, in vivo

validation using PCa xenograft models or genetically engineered

mouse models was absent, which would be critical to confirm the

in vivo relevance of these hub genes. In summary, while the

present study provides a foundation for understanding the role of

mitochondrial hub genes in PCa, future studies addressing these

limitations, including large-scale clinical validation, mechanistic

experiments and subtype-specific analyses, will be necessary to

advance the translational potential of the findings.

In summary, the present study found that ACACB, PDK4

and GATM were downregulated, while MCCC2, MRPL12 and FASN are

upregulated in PCa; among these genes, MCCC2 and FASN were linked

to adverse PCa phenotypes and MRPL12, PDK4, ACACB and GATM showed

the strongest associations with mitochondrial metabolic pathways in

PCa, providing potential therapeutic targets for PCa treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Hunan Provincial Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 2025JJ50553 and 2025JJ80574) and

Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

kq2502330).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SL and HS conducted most experiments and wrote the

manuscript. LH, LL, YW conceived, designed and interpreted data.

All authors edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. SL and HS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Moris L, Cumberbatch MG, Van den Broeck T,

Gandaglia G, Fossati N, Kelly B, Pal R, Briers E, Cornford P, De

Santis M, et al: Benefits and risks of primary treatments for

High-risk localized and locally advanced prostate cancer: An

international multidisciplinary systematic review. Eur Urol.

77:614–627. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, Loeb S,

Johnson DC, Reiter RE, Gillessen S, Van der Kwast T and Bristow RG:

Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:92021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Schaeffer E, Srinivas S, Antonarakis ES,

Armstrong AJ, Bekelman JE, Cheng H, D'Amico AV, Davis BJ, Desai N,

Dorff T, et al: NCCN guidelines insights: Prostate cancer, version

1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 19:134–143. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Linder S, van der Poel HG, Bergman AM,

Zwart W and Prekovic S: Enzalutamide therapy for advanced prostate

cancer: Efficacy, resistance and beyond. Endocr Relat Cancer.

26:R31–R52. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Parida S, Pal I, Parekh A, Thakur B,

Bharti R, Das S and Mandal M: GW627368X inhibits proliferation and

induces apoptosis in cervical cancer by interfering with EP4/EGFR

interactive signaling. Cell Death Dis. 7:e21542016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sathya S, Sudhagar S, Sarathkumar B and

Lakshmi BS: EGFR inhibition by pentacyclic triterpenes exhibit cell

cycle and growth arrest in breast cancer cells. Life Sci. 95:53–62.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kang H, Kim B, Park J, Youn H and Youn B:

The Warburg effect on radioresistance: Survival beyond growth.

Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1889882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chen H, Zhou L, Wu X, Li R, Wen J, Sha J

and Wen X: The PI3K/AKT pathway in the pathogenesis of prostate

cancer. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 21:1084–1091. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kumar R, Srinivasan S, Pahari P, Rohr J

and Damodaran C: Activating stress-activated protein

kinase-mediated cell death and inhibiting epidermal growth factor

receptor signaling: A promising therapeutic strategy for prostate

cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 9:2488–2496. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu W, Yang Q, Fung KM, Humphreys MR, Brame

LS, Cao A, Fang YT, Shih PT, Kropp BP and Lin HK: Linking

γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor to epidermal growth factor receptor

pathways activation in human prostate cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

383:69–79. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hirokawa N, Noda Y, Tanaka Y and Niwa S:

Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10:682–696. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Drechsler H and McAinsh AD: Kinesin-12

motors cooperate to suppress microtubule catastrophes and drive the

formation of parallel microtubule bundles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

113:E1635–E1644. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhao H, Bo Q, Wu Z, Liu Q, Li Y, Zhang N,

Guo H and Shi B: KIF15 promotes bladder cancer proliferation via

the MEK-ERK signaling pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 11:1857–1868.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mortensen MM, Høyer S, Lynnerup AS,

Ørntoft TF, Sørensen KD, Borre M and Dyrskjøt L: Expression

profiling of prostate cancer tissue delineates genes associated

with recurrence after prostatectomy. Sci Rep. 5:160182015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Arredouani MS, Lu B, Bhasin M, Eljanne M,

Yue W, Mosquera JM, Bubley GJ, Li V, Rubin MA, Libermann TA and

Sanda MG: Identification of the transcription factor single-minded

homologue 2 as a potential biomarker and immunotherapy target in

prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 15:5794–5802. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ross-Adams H, Lamb AD, Dunning MJ, Halim

S, Lindberg J, Massie CM, Egevad LA, Russell R, Ramos-Montoya A,

Vowler SL, et al: Integration of copy number and transcriptomics

provides risk stratification in prostate cancer: A discovery and

validation cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2:1133–1144. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hocaoglu H and Sieber M: Mitochondrial

respiratory quiescence: A new model for examining the role of

mitochondrial metabolism in development. Semin Cell Dev Biol.

138:94–103. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Boso D, Piga I, Trento C, Minuzzo S, Angi

E, Iommarini L, Lazzarini E, Caporali L, Fiorini C, D'Angelo L, et

al: Pathogenic mitochondrial DNA variants are associated with

response to anti-VEGF therapy in ovarian cancer PDX models. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 43:3252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kopinski PK, Singh LN, Zhang S, Lott MT

and Wallace DC: Mitochondrial DNA variation and cancer. Nat Rev

Cancer. 21:431–445. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim M, Gorelick AN, Vàzquez-García I,

Williams MJ, Salehi S, Shi H, Weiner AC, Ceglia N, Funnell T, Park

T, et al: Single-cell mtDNA dynamics in tumors is driven by

coregulation of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Nat Genet.

56:889–899. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zichri SB, Kolusheva S, Shames AI,

Schneiderman EA, Poggio JL, Stein DE, Doubijensky E, Levy D,

Orynbayeva Z and Jelinek R: Mitochondria membrane transformations

in colon and prostate cancer and their biological implications.

Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 1863:1834712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Papachristodoulou A, Rodriguez-Calero A,

Panja S, Margolskee E, Virk RK, Milner TA, Martina LP, Kim JY, Di

Bernardo M, Williams AB, et al: NKX3.1 Localization to mitochondria

suppresses prostate cancer initiation. Cancer Discov. 11:2316–2333.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mamouni K, Kallifatidis G and Lokeshwar

BL: Targeting mitochondrial metabolism in prostate cancer with

triterpenoids. Int J Mol Sci. 22:24662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen CL, Lin CY and Kung HJ: Targeting

mitochondrial OXPHOS and their regulatory signals in prostate

cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 22:134352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Han C, Wang Z, Xu Y, Chen S, Han Y, Li L,

Wang M and Jin X: Roles of reactive oxygen species in biological

behaviors of prostate cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2020:12696242020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang H, Li N, Liu Q, Guo J, Pan Q, Cheng

B, Xu J, Dong B, Yang G, Yang B, et al: Antiandrogen treatment

induces stromal cell reprogramming to promote castration resistance

in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 41:1345–1362.e9. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guerra F, Guaragnella N, Arbini AA, Bucci

C, Giannattasio S and Moro L: Mitochondrial dysfunction: A novel

potential driver of Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer.

Front Oncol. 7:2952017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Civenni G, Bosotti R, Timpanaro A, Vàzquez

R, Merulla J, Pandit S, Rossi S, Albino D, Allegrini S, Mitra A, et

al: Epigenetic control of mitochondrial fission enables

Self-renewal of stem-like tumor cells in human prostate cancer.

Cell Metab. 30:303–318.e6. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jeong SY and Seol DW: The role of

mitochondria in apoptosis. BMB Rep. 41:11–22. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Castilla C, Congregado B, Chinchón D,

Torrubia FJ, Japón MA and Sáez C: Bcl-xL is overexpressed in

hormone-resistant prostate cancer and promotes survival of LNCaP

cells via interaction with proapoptotic Bak. Endocrinology.

147:4960–4967. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Krajewska M, Krajewski S, Epstein JI,

Shabaik A, Sauvageot J, Song K, Kitada S and Reed JC:

Immunohistochemical analysis of bcl-2, bax, bcl-X, and mcl-1

expression in prostate cancers. Am J Pathol. 148:1567–1576.

1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Massie CE, Lynch A, Ramos-Montoya A, Boren

J, Stark R, Fazli L, Warren A, Scott H, Madhu B, Sharma N, et al:

The androgen receptor fuels prostate cancer by regulating central

metabolism and biosynthesis. EMBO J. 30:2719–2733. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Audet-Walsh É, Dufour CR, Yee T, Zouanat

FZ, Yan M, Kalloghlian G, Vernier M, Caron M, Bourque G, Scarlata

E, et al: Nuclear mTOR acts as a transcriptional integrator of the

androgen signaling pathway in prostate cancer. Genes Dev.

31:1228–1242. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhong C, Long Z, Yang T, Wang S, Zhong W,

Hu F, Teoh JY, Lu J and Mao X: M6A-modified circRBM33 promotes

prostate cancer progression via PDHA1-mediated mitochondrial

respiration regulation and presents a potential target for ARSI

therapy. Int J Biol Sci. 19:1543–1563. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Owari T, Tanaka N, Nakai Y, Miyake M, Anai

S, Kishi S, Mori S, Fujiwara-Tani R, Hojo Y, Mori T, et al:

5-Aminolevulinic acid overcomes hypoxia-induced radiation

resistance by enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

production in prostate cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 127:350–363.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li X, Yao L, Wang T, Gu X, Wu Y and Jiang

T: Identification of the mitochondrial protein POLRMT as a

potential therapeutic target of prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis.

14:6652023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ji X, Yang Z, Li C, Zhu S, Zhang Y, Xue F,

Sun S, Fu T, Ding C, Liu Y, et al: Mitochondrial ribosomal protein

L12 potentiates hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating

mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolic reprogramming. Metabolism.

152:1557612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fan Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Li Y, Wang S, Weng

Y, Yang Q, Chen C, Lin L, Qiu Y, et al: Development and clinical

validation of a novel 5 gene signature based on fatty acid

Metabolism-related genes in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2022:32853932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Crowell PD, Giafaglione JM, Jones AE,

Nunley NM, Hashimoto T, Delcourt AML, Petcherski A, Agrawal R,

Bernard MJ, Diaz JA, et al: MYC is a regulator of androgen receptor

inhibition-induced metabolic requirements in prostate cancer. Cell

Rep. 42:1132212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li L, Chao Z, Peng H, Hu Z, Wang Z and

Zeng X: Tumor ABCC4-mediated release of PGE2 induces CD8+ T cell

dysfunction and impairs PD-1 blockade in prostate cancer. Int J

Biol Sci. 20:4424–4437. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Löf C, Sultana N, Goel N, Heron S,

Wahlström G, House A, Holopainen M, Käkelä R and Schleutker J: ANO7

expression in the prostate modulates mitochondrial function and

lipid metabolism. Cell Commun Signal. 23:712025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|