Introduction

Improvements in socioeconomic conditions have

enhanced the average life expectancy of humans (1). However, an aging population has been

associated with some public health concerns (2). In particular, the cancer incidence and

mortality rates have been increasing (3). According to published epidemiological

studies, global cancer incidence in 2012 reached 14.1 million new

cases with 8.2 million associated deaths (4). By 2022, however, these figures had

risen to ~19.98 million newly diagnosed cases and 9.74 million

cancer-attributable deaths worldwide (3). Globally, cancer, a chronic disease, is

a major cause of death (5,6).

Chemotherapy, radiotherapy (RT) and surgical

resection were the main therapeutic strategies for cancer until the

21st century. RT was traditionally assumed to function by

irreversibly damaging tumor cell DNA, which led to cell death or

loss of replicative ability (7).

Preclinical and clinical studies have reported that the immune

system also determines the response to RT (8,9). More

than a century ago, clinicians observed complete remission in

advanced cancer cases after acute bacterial infections (10). This observation established the

concept of immunological approaches for cancer treatment.

Immunotherapy has since transformed cancer treatment and improved

the current understanding of tumor biology (11). It has been highlighted that cancer

treatment should not only target the cancer cells but also consider

the entire tumor microenvironment (TME). The cellular mediators of

the anticancer effects of immunotherapy are immune cells (11). Previous studies have reported that

the combination of RT and immunotherapy significantly improves

cancer treatment outcomes (12,13).

However, the effect of the combination of RT and immunotherapy on

the T-cell receptor β chain (TCRβ) repertoire is unclear.

The immune system determines the anticancer efficacy

of both RT and immunotherapy. T cells are involved in adaptive

immune responses and complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3)

determines the specificity of T cells (14). CDR3 is generated through the

recombination of germline V, D and J genes, as well as the deletion

and insertion of nucleotides at the V(D)J junctions (15–17).

As CDR3 closely interacts with antigen peptides, its sequence

diversity is a key indicator of T cell diversity. Recombination

events at the TCR loci can lead to the production of non-functional

(out-of-frame) TCRs with frameshift mutations or premature stop

codons (18,19). In this situation, the T cells

attempt to rearrange the second allele. If a functional (in-frame)

TCR is successfully formed, the T cells carry both functional and

non-functional TCR genes (18).

There is a certain level of mRNA in the T cells, although

non-functional TCR genes cannot be translated into functional TCRβ

chains. Non-functional TCRs can represent the pre-selection TCR

repertoire as they are not influenced by the functional selection

processes (both positive and negative selection) (19–21).

Functional TCRs can be used to investigate the TCR repertoire after

selection. Certain studies have demonstrated that deep sequencing

analysis of TCRβ CDR3 can provide useful insights into the effect

of treatment on the T cell response (22,23).

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4)

and programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) are immunosuppressive molecules

expressed on the immune cell surface and can regulate immune

activation (24). Furthermore,

CTLA-4 and PD-1 prevent the occurrence of autoimmune effects. The

present study analyzed a publicly available sequencing dataset of

the immune repertoire of a mouse cancer model treated with a

combination of RT and anti-CTLA-4/anti-PD-1 therapy. Furthermore, a

public dataset of T cell repertoire sequencing derived from the

hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) of mice exposed to various

radiation doses was also analyzed. The present study focused on

examining the effects of RT and immunotherapy on the TCRβ

repertoire in cancer treatment based on various parameters, such as

TCRβ CDR3 diversity, frequency distribution of CDR3, length

distribution of CDR3, V/J gene usage, V-J pairing and overlap

indices. The findings from the present study will enhance the

current understanding of radiation-induced adaptive immune

responses and the TCRβ repertoire after RT and

anti-CTLA-4/anti-PD-1 therapy, which can potentially provide

valuable insights into the complex dynamics driving global cancer

patterns.

Materials and methods

TCR sequencing data from public

databases

The TCR sequencing data of T cells derived from

CBA/HmCherry mouse HSCs exposed to radiation doses of 0,

10 and 100 mGy were obtained online from the Adaptive

Biotechnologies immuneACCESS database (https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/pub/candeias-2019-mouse;

immuneACCESS DOI: http://doi.org/10.21417/SC012019) (25). Meanwhile, the TCR data of

tumor-bearing mice treated with the combination of RT and

anti-CTLA-4/anti-PD-1 therapy were downloaded from different

sources

[https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/pub/rudqvist-2017cancerimmunology-research,

immune ACCESS DOI: https://doi.org/10.21417/B7H34S (26) and

https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/pub/dovedi-2017-clincancerres,

immune ACCESS DOI: https://doi.org/10.21417/B7TS67 (27)]. The T cell repertoires in 45 samples

(9, 16 and 20 samples from mice exposed to different radiation

doses, mice treated with RT and anti-CTLA-4 therapy for breast

cancer and mice treated with RT and anti-PD-1 therapy for colon

cancer, respectively) were analyzed. TCRβ sequencing was performed

on peripheral blood samples exhibiting the highest levels of

donor-derived T lymphocyte reconstitution. Based on the percentage

of T lymphocytes, the top samples were chosen from the following

groups: 11–15% (HSCs exposed to 0 mGy), 4–13% (HSCs exposed to 10

mGy) and 3.5–10% (HSCs exposed to 100 mGy). The yield of unique

TCRβ rearrangements was extremely low in 1 NSG mouse reconstituted

with 100 mGy-irradiated HSCs, which exhibited a low T-cell

frequency of merely 3.5% among leukocytes. Thus, these mice were

classified as outliers based on the Hubert and Vandervieren test

and excluded from subsequent analyses (25). The original research had obtained

ethical approval.

DNA extraction, TCRβ immunosequencing

and data analysis

The experimental procedures, sample collection, DNA

extraction and TCRβ immunosequencing were previously described in

the original study (26), while

data analysis based on process data was conducted as part of the

present study. Briefly, blood samples were collected from mice 6

months after receiving HSC transplants with radiation doses of 0,

10 and 100 mGy. Additionally, breast cancer and colon cancer

tissues were obtained from mice treated with RT combined with anti

CTLA-4, RT combined with anti PD-1 and untreated mice. The mouse

blood samples and the untreated and treated tumor samples had been

subjected to TCRβ CDR3 immunosequencing using the ImmunoSEQ™ assay

(28,29). A synthetic immune receptor library

was used to identify and reduce PCR biases and computational

techniques were applied to remove any remaining biases after

sequencing and ensure the quantitative accuracy of the ImmunoSEQ™

detection kit (29). PCR bias

assessed the total amplification bias by computing the following

two metrics for the amplification bias of each template compared

with the mean: The dynamic range (maximum bias divided by minimum

bias) and the sum of squared logarithmic bias values. The process

of altering primer concentrations was repeated until improvements

ceased (29). In the

biased-controlled multiplex PCR experiment, the extracted DNA was

amplified using 54 forward primers targeting V genes and 13 reverse

primers targeting J genes. High-throughput sequencing was then

performed. The raw data were processed and analyzed with an

ImmunoSEQ™ analyzer (http://www.adaptivebiotech.com/immunoseq). Then, a

reanalysis of the data from the original study was performed in the

present study. Subsequently, correction of sequencing errors and

PCR amplification bias was performed with MiTCR (http://mitcr.milaboratory.com/) (30). The international ImMunoGeneTics

database (www.imgt.org) provided gene definitions

for the TCRβ V, D and J genes. As the CDR3 sequence can be

generated by various pathways, it cannot directly provide the

probability distribution of hidden recombination events (31,32).

Consequently, TCR nucleotide sequence probabilities were calculated

using the existing recombination model (33). According to the probability model,

specific sequences of CDR3 may be generated based on the original

recombination process. This enables the annotation of the V(N)D(N)J

genes for each distinctive CDR3 and the determination of the amino

acid sequence for each gene. Furthermore, the combat function in

the sva package (R version 4.4.1) was used to address batch effects

across different datasets. Next, TCR data were subjected to various

bioinformatics analyses based on the R statistical programming

language (R version 4.4.1), which encompassed the diversity of TCRβ

repertoire, usage of V/J gene, V-J gene pairing, length

distribution of CDR3 and vDeletion, d3Deletion, d5Deletion,

jDeletion, n1Insertion and n2Insertion distribution (14,34–37).

These analyses were evaluated using previously published research

(14,34,37).

The D50 index, Gini index, inverse Simpson index, Shannon index and

Simpson index were used to calculate the TCR repertoire diversity

(38,39). Shared TCR repertoires between

species were quantified using overlap coefficients of |X and Y|/min

(|X|, |Y|). The TCRβ overlap was calculated based on the number of

common nucleotide sequences in each sharing category (summed across

all subjects in which this sequence was found)-[Percentage

(n)=number of common nucleotide sequences appeared in ≥n

subjects/total number of nucleotide sequences in sample]. In

addition, principal coordinate analysis (PCA) was used to perform

cluster analysis on the V/J genes of mice in the radiation exposure

group and healthy control (HC) group.

Statistical analysis

Means between two groups were compared using the

unpaired t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. One-way ANOVA or

Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare group means across three or

more groups and Bonferroni was used to correct for multiple

comparisons. Additionally, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test

was used. Data are represented as mean ± SD or percentages (%). All

statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 20; IBM

Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

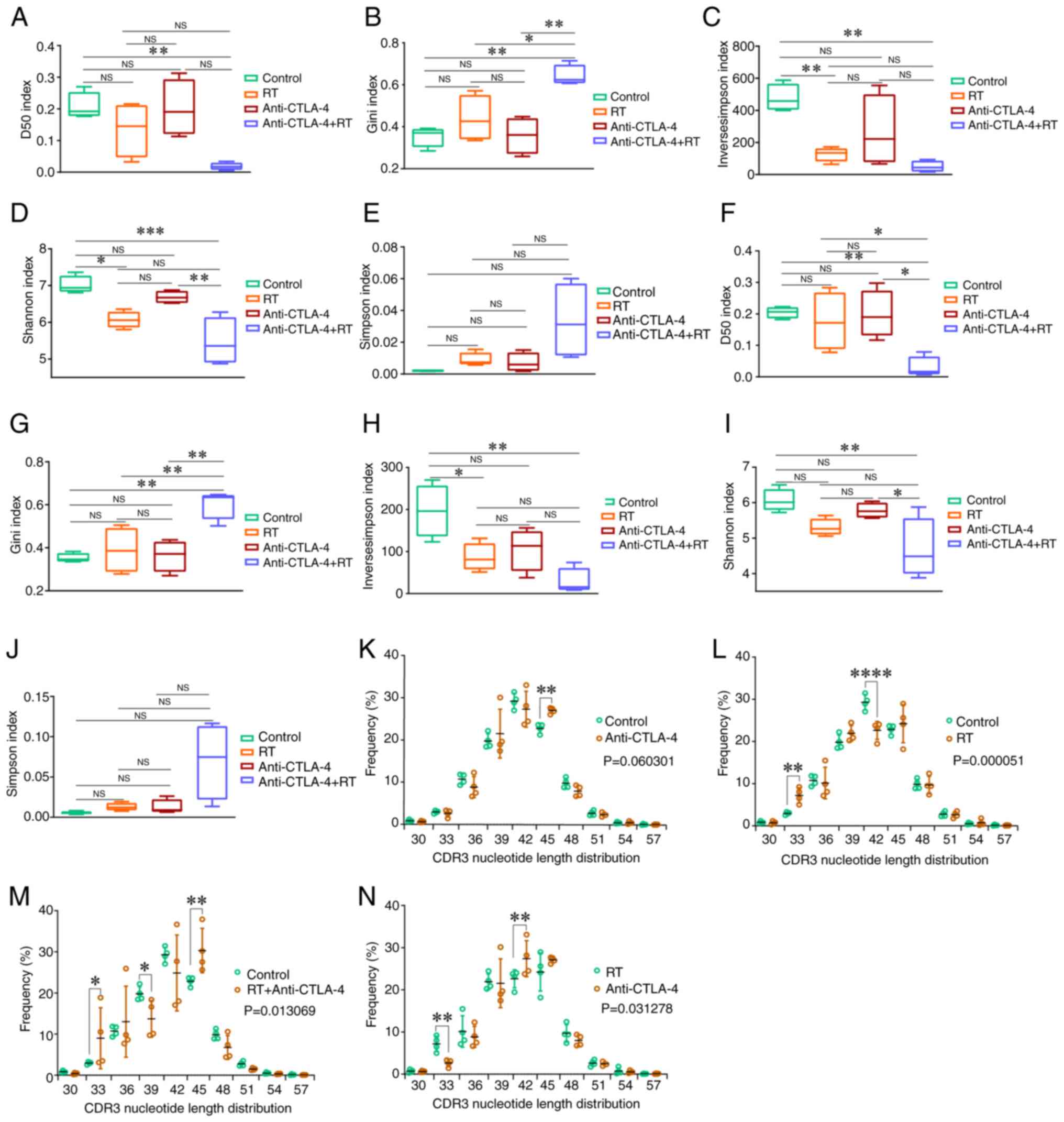

RT and anti-CTLA-4 therapy alters the

TCR repertoire

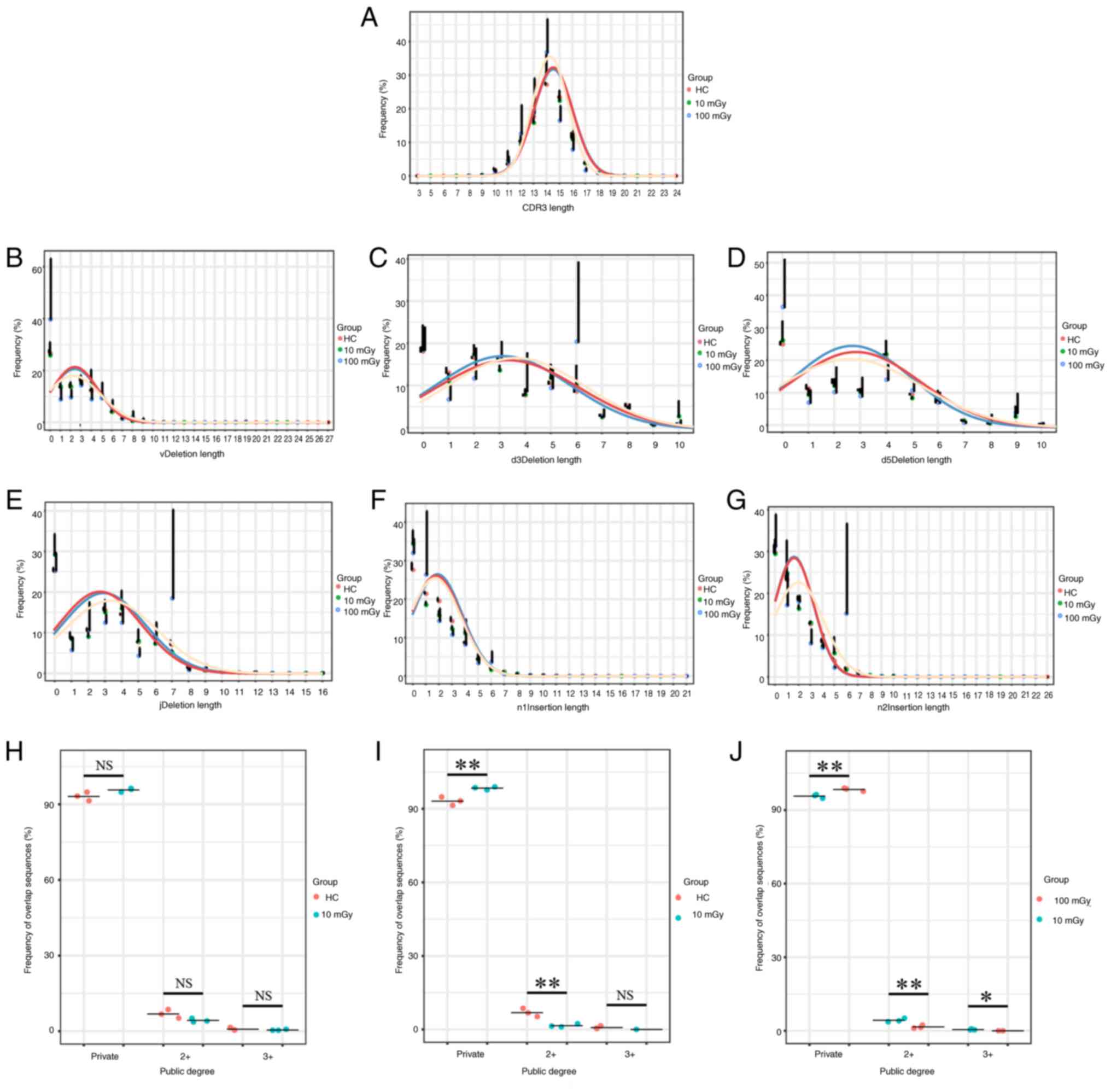

Alterations in TCRβ repertoire diversity

The TCRβ repertoires of T cells sorted from tumors

of the untreated (control), RT, anti-CTLA-4 and anti-CTLA-4 + RT

groups were analyzed. The diversity indices were determined based

on D50, Gini, inverse Simpson, Shannon and Simpson indices

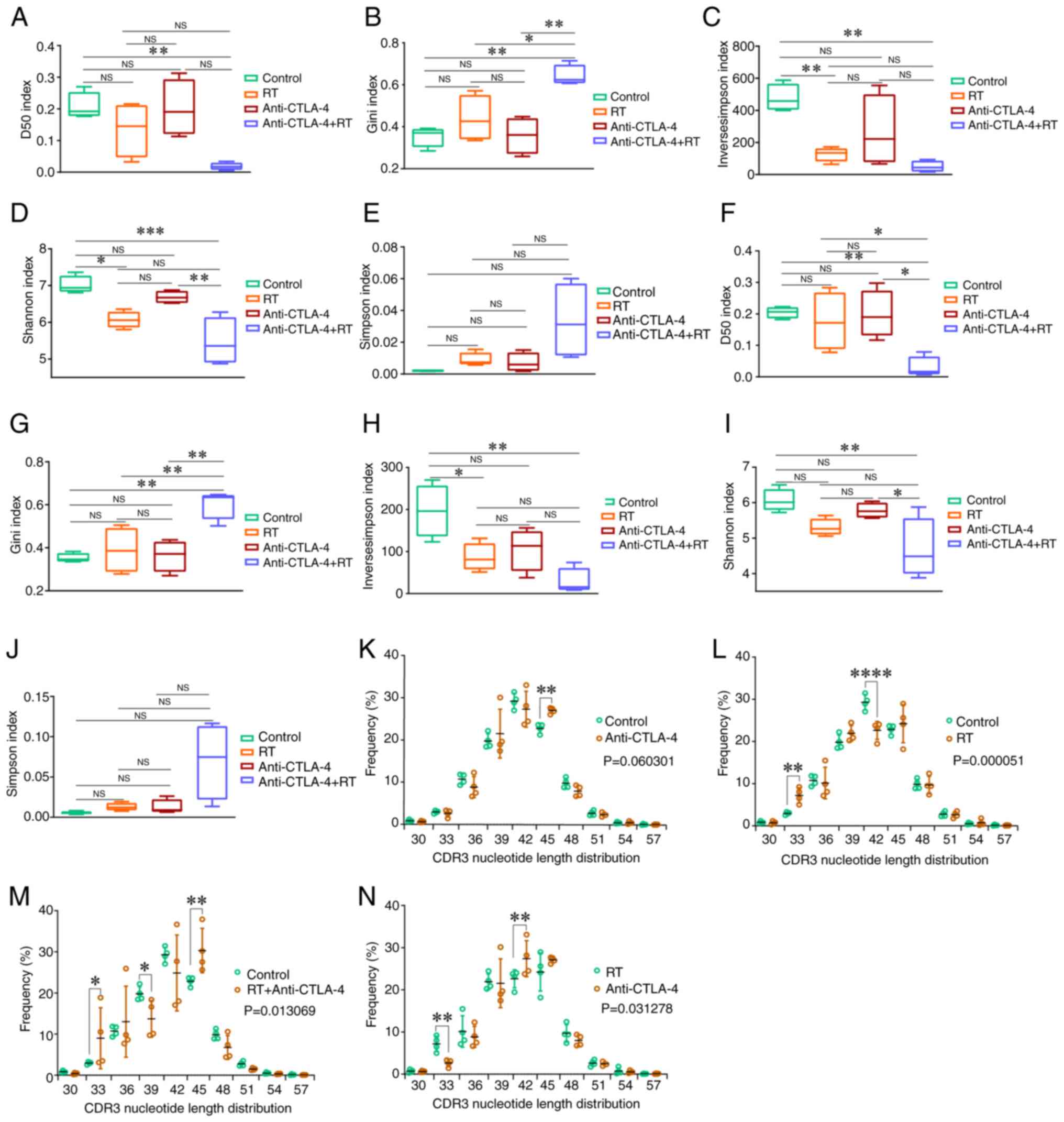

(Fig. 1). When considering the Gini

or Simpson indexes, a smaller value is associated with a higher

CDR3 diversity. The greater the index, the more diverse the CDR3,

when it comes to the D50, Shannon and inverse Simpson diversity

indices. In the post-selection repertoire (in-frame sequences;

Fig. 1A-E), the D50 index in the

anti-CTLA-4 + RT group was lower than that in the control

(P<0.01; Fig. 1A). The Gini

index in the anti-CTLA-4 + RT group was higher than that in the

control (P<0.01), RT (P<0.05) and anti-CTLA-4 (P<0.01)

groups (Fig. 1B). The inverse

Simpson index in the RT and the anti-CTLA-4 + RT groups was lower

than that in the control group (both P<0.01; Fig. 1C). The Shannon index in the RT group

(P<0.05) and anti-CTLA-4 + RT (P<0.001) groups was lower than

that in the control group, furthermore, it was also significantly

lower in the anti-CTLA-4 + RT group compared with that in the

anti-CTLA-4 group (Fig. 1D). Other

parameters were not significantly different between the control and

treatment groups. Furthermore, similar trends were observed in the

pre-selection repertoire (out-of-frame TCRβ sequences; Fig. 1F-J). In summary, the diversity of

the TCRβ CDR3 amino acid sequence in the treatment group

(especially in the RT + anti-CTLA-4 group) was lower than that in

the control group.

| Figure 1.CDR3 nucleotide length distribution

and diversity analysis of the TCRβ repertoire in mice with RT and

anti-CTLA-4 therapy, and the control group. The TCRβ CDR3 diversity

in the post-selection repertoire (in-frame sequences) was estimated

by (A) the D50 index, (B) Gini index, (C) Inverse Simpson index,

(D) Shannon index and (E) Simpson index. (F-J) The TCRβ CDR3

diversity in the pre-selection repertoire (out-of-frame sequences)

was estimated by the aforementioned five diversity indices. Data

are presented as the mean ± SD; comparisons were made using one-way

ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test and corrected for multiple comparisons

using Bonferroni. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. (K-N)

The comparison of CDR3 length between the different groups. All of

the CDR3 lengths that differed significantly (P<0.05) between

treatment group mice and controls are presented. Data are presented

as the mean ± SD; the overall differences of the CDR3 length

distribution (ten length categories) between groups were compared

using two-way ANOVA, and Tukey's test was performed after the

two-way ANOVA to compare the differences in each CDR3 length

between groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. CDR3, complementarity-determining region 3; TCRβ,

T-cell receptor β-chain; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated

antigen-4; RT, radiotherapy; NS, not significant. |

Alterations in CDR3 length

distribution

To further understand the changes in the TCRβ

repertoire induced by radiation and anti-CTLA-4 treatment, the

length distribution of the CDR3 nucleotide sequences was examined.

The overall difference in CDR3 length between the anti-CTLA-4 group

and the control group did not reach statistical significance

(P>0.05), but the CDR3 length was longer at 45-nucleotides

compared with the control group (P<0.01) (Fig. 1K). The CDR3 length in the RT group

was lower than that in the control group (P<0.001; Fig. 1L). Additionally, the CDR3 length

distribution was significantly different between the RT +

anti-CTLA-4 and control groups (P<0.05, Fig. 1M). Furthermore, the CDR3 length in

the anti-CTLA-4 group was higher than that in the RT group

(P<0.05; Fig. 1N).

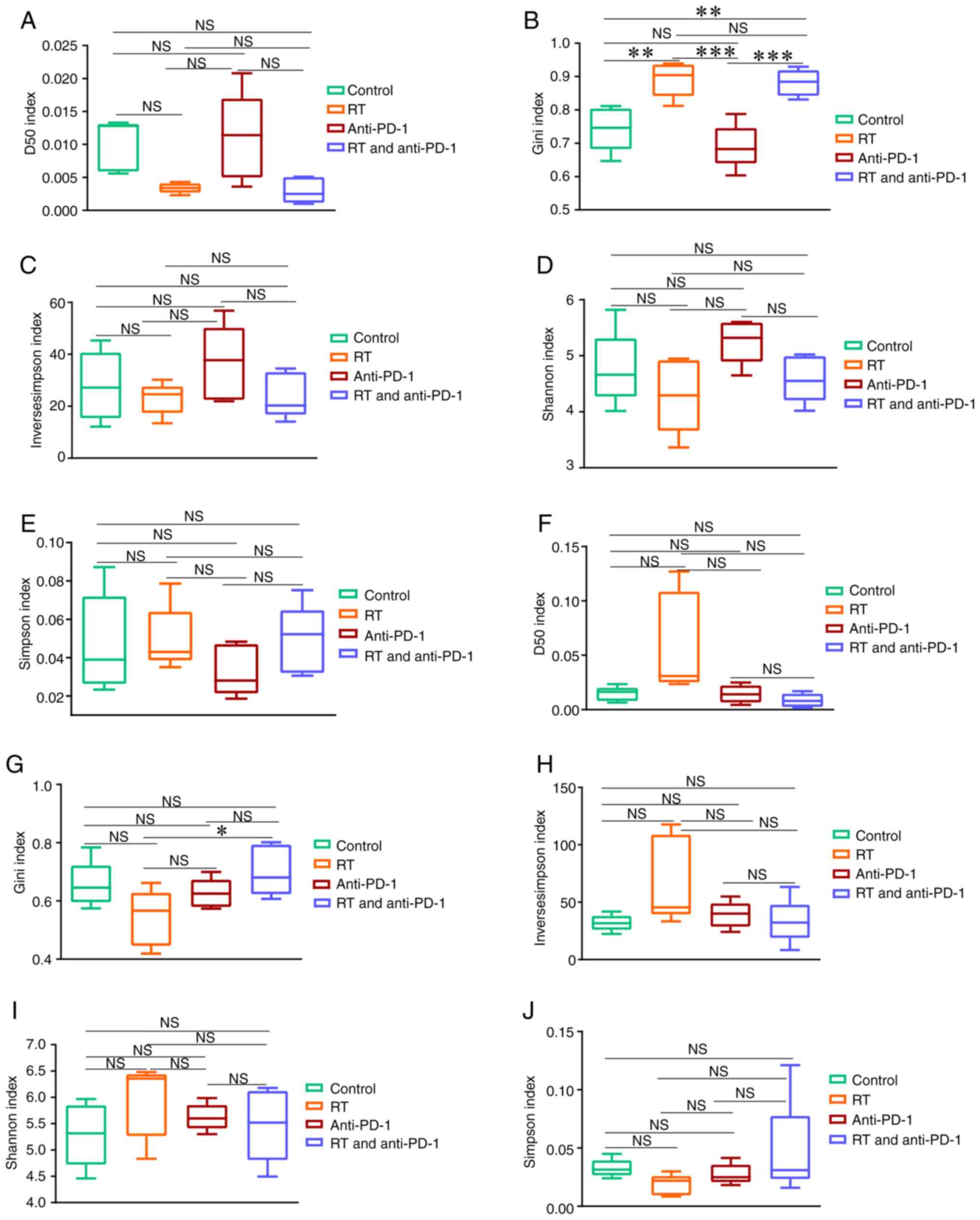

RT and anti-PD-1 therapy alters the

TCR repertoire

Alterations in TCRβ repertoire diversity

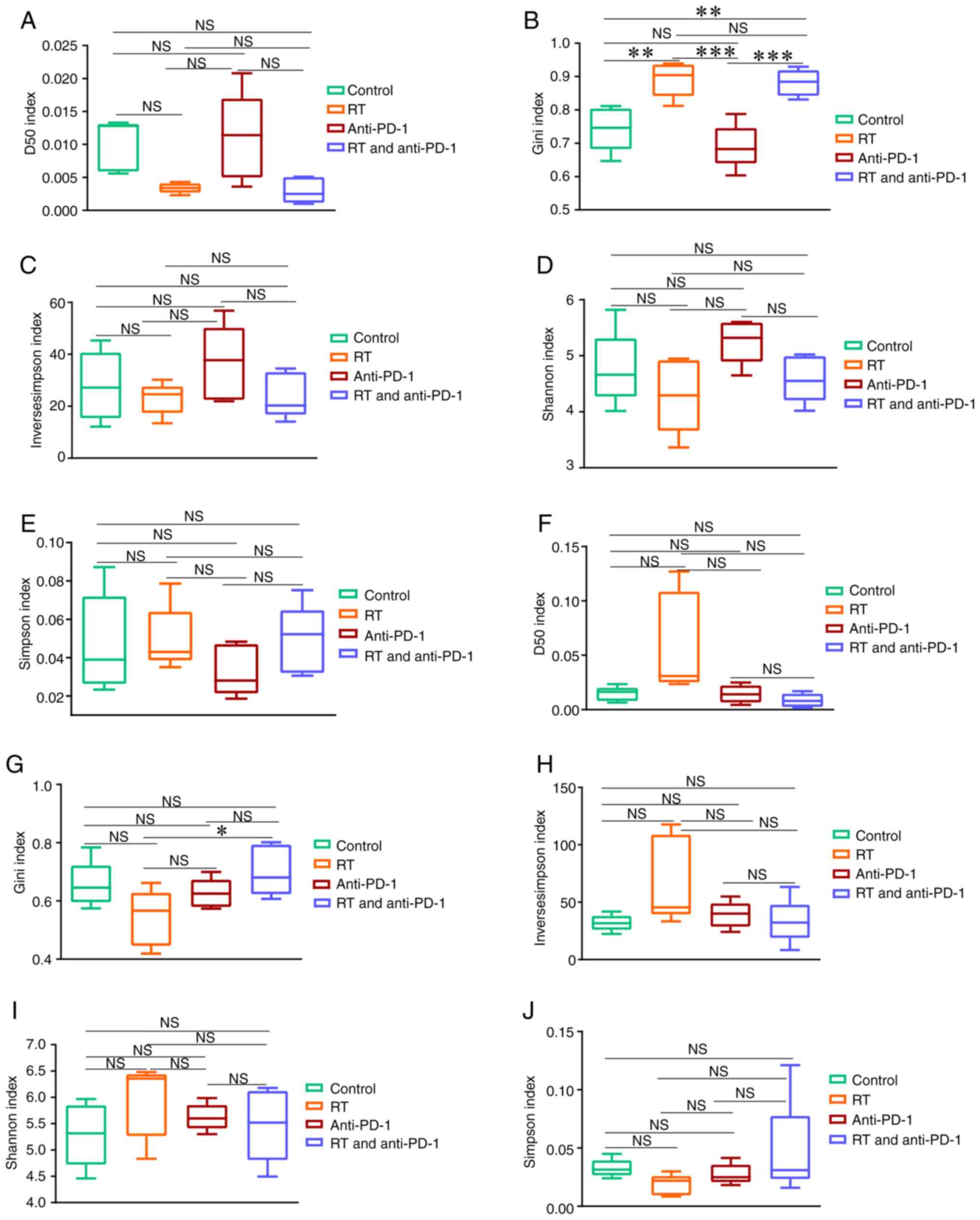

Next, the present study examined the TCRβ diversity

and complexity after RT and/or anti-PD-1 treatment. The D50, Gini,

inverse Simpson, Shannon and Simpson indices were used to evaluate

the TCRβ amino acid sequence diversity in the control, RT,

anti-PD-1 and RT + anti-PD-1 groups. The diversity of the in-frame

TCRβ sequences was first examined (Fig.

2). As shown in Fig. 2B, within

the radiation field (radiation irradiated tumors), the Gini index

in the RT and RT + anti-PD-1 groups was higher than that in the

control group (both P<0.01). Additionally, the Gini index in the

RT and RT + anti-PD-1 groups was higher than that in the anti-PD-1

group (both P<0.01). Additionally, although changes in other

parameters were observed between the treatment group and the

control group, these differences did not reach statistical

significance (P>0.05; Fig. 2A and

C-E). Next, the diversity of TCRβ outside the radiation field

(tumors that have not been irradiated with radiation) was examined.

The Gini index in the RT + anti-PD-1 group was higher than that in

the RT group (P<0.05; Fig. 2G).

Similar to within the radiation field, although changes in other

parameters between the treatment group and the control group could

be observed outside the radiation field, these differences did not

reach statistical significance (P>0.05; Fig. 2F and H-J). The differences in TCRβ

diversity in the post-selection repertoire were similar to those in

the pre-selection repertoire (Fig.

S1).

| Figure 2.Diversity indexes of the

post-selection repertoire in mice with RT and anti-PD-1 therapy,

and the control group. The diversity of the treatment area was

measured by (A) the D50 index, (B) Gini index, (C) Inverse Simpson

index, (D) Shannon index and (E) Simpson index. (F) The D50 index,

(G) Gini index, (H) Inverse Simpson index, (I) Shannon index and

(J) Simpson index were all used to evaluate the diversity of the

outside the RT field. Data are presented as the mean ± SD;

comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA corrected for multiple

comparisons using Bonferroni. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 (two-tailed). PD-1, programmed cell death-1; NS, not

significant; RT, radiotherapy. |

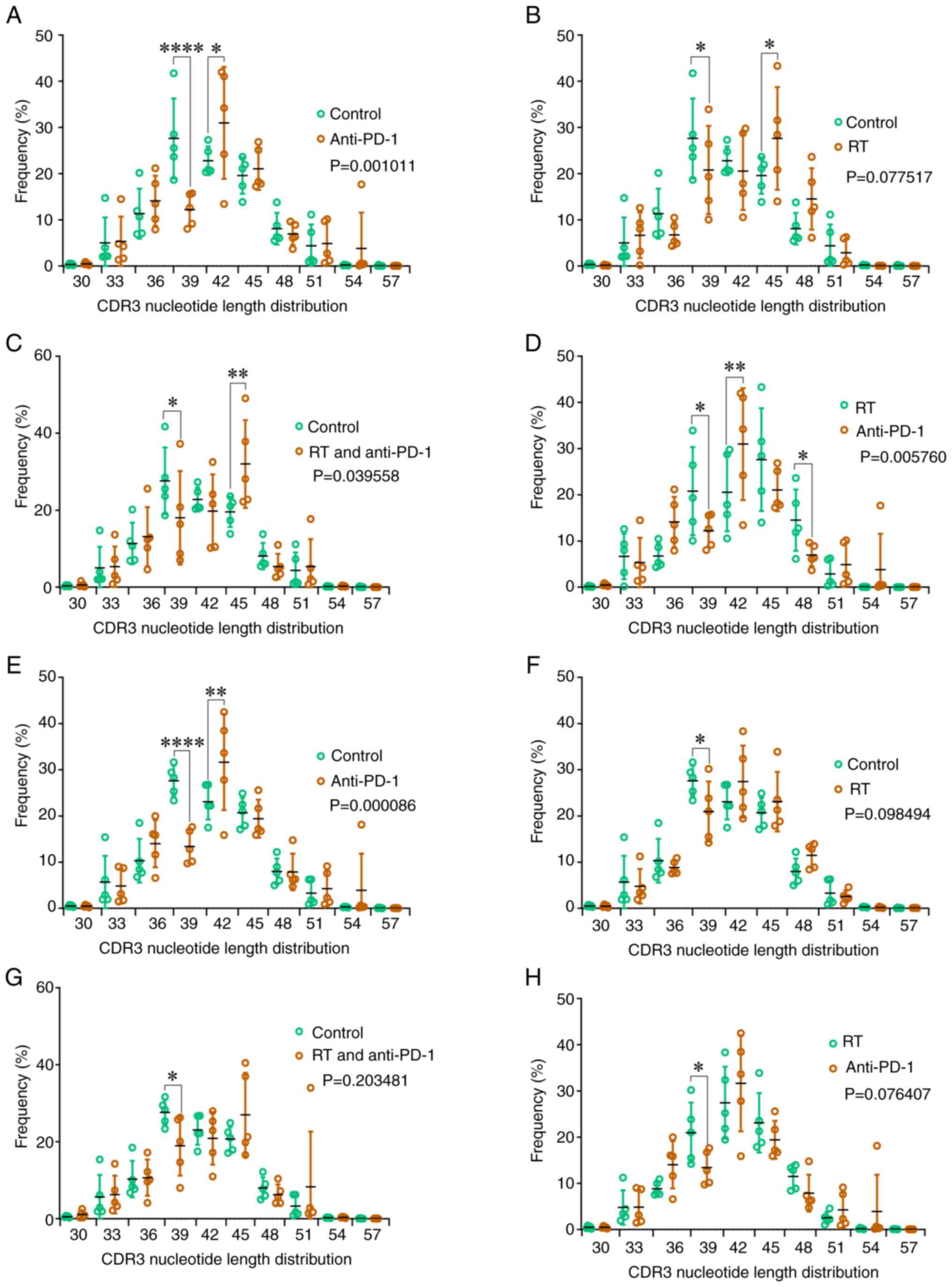

Alterations in CDR3 length

distribution

The CDR3 length distribution within and outside the

radiation area was examined. The TCRβ CDR3 length within the

radiation area in the anti-PD-1 and RT + anti-PD-1 groups was

significantly longer than that in the control group (P<0.05;

Fig. 3A and C). Additionally, the

CDR3 length of the anti-PD-1 group was shorter than that of the RT

group (P<0.01; Fig. 3D). The

CDR3 length outside the radiation area in the anti-PD-1 group was

longer than that in the control group (P<0.001; Fig. 3E). In addition, whether within or

outside the radiation field, the difference in CDR3 length between

the RT group and the control group did not reach statistical

significance (P>0.05; Fig. 3 and

F). Furthermore, it was also observed that the CDR3 length was

similar outside the radiation field between the RT + anti-PD-1

group and the control group, as well as between the RT group and

the anti-PD-1 group (P>0.05; Fig. 3G

and H).

Analysis of the TCR profile of T cells

differentiated from the HSCs of mice exposed to various radiation

doses

The findings of the present study indicated that the

RT-immunotherapy combination decreased CDR3 diversity and altered

the CDR3 length. However, the potential reasons for these

alterations were not elucidated. Hence, the changes in the TCR

repertoire in the peripheral blood samples of NSG mice 6 months

after the transplantation of HSCs derived from

CBA/HmCherry mice exposed to different radiation doses

for 7 days were next investigated.

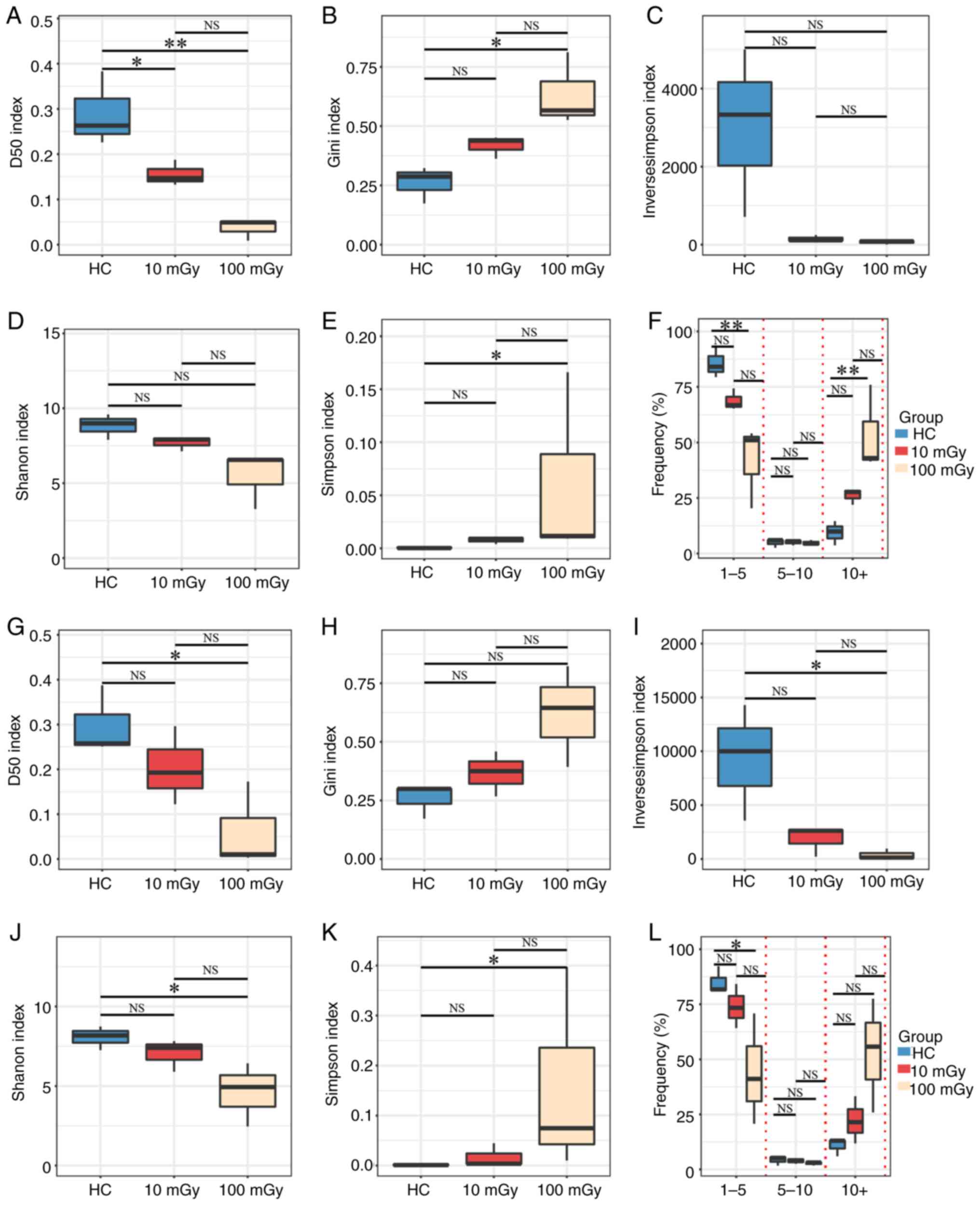

Diversity of the TCRβ repertoire

varies under different radiation doses

The D50 index, Gini index, inverse Simpson index,

Shannon index and Simpson index were examined to assess the impact

of different radiation doses on TCRβ diversity and nucleotide

sequence clonal expansion in the peripheral blood of NSG mice

following the aforementioned treatment. As shown in Fig. 4, the highest diversity was observed

in the HC group. The TCR diversity in the radiation (10 or 100

mGy)-exposed groups was lower than that in the HC group in both

post-selection (Fig. 4A-E) and

pre-selection repertoires (Fig.

4G-K). Additionally, a trend towards decreased TCR diversity

with increasing radiation dose was observed, although this trend

did not reach statistical significance.

Based on the read frequencies of unique TCRβ

nucleotide sequences (after correction), the TCRβ sequences were

categorized into the following three groups: Low-abundance (1–5

reads), medium-abundance (5–10 reads) and high-abundance (>10

reads) sequences, represented as percentages of the total sequences

for each TCRβ [Fig. 4F (in-frame)

and Fig. 4L (out-of-frame)]. The

average percentages of low-abundance and medium-abundance TCRβ

sequences were the highest in the HC group, followed by the 10

mGy-exposed and 100 mGy-exposed groups. Meanwhile, the average

percentage of high-abundance TCRβ sequences was the highest in the

100 mGy-exposed group, followed by the 10 mGy-exposed and HC

groups. However, the differences were not always significant

(P>0.05), particularly between the HC group and the 10

mGy-exposed group, and between the 10 mGy-exposed and 100

mGy-exposed groups. These results indicate that the HC group

exhibits the highest TCRβ diversity and the lowest clonality,

whereas the 100 mGy-exposed group exhibits the lowest TCRβ

diversity and the highest clonality.

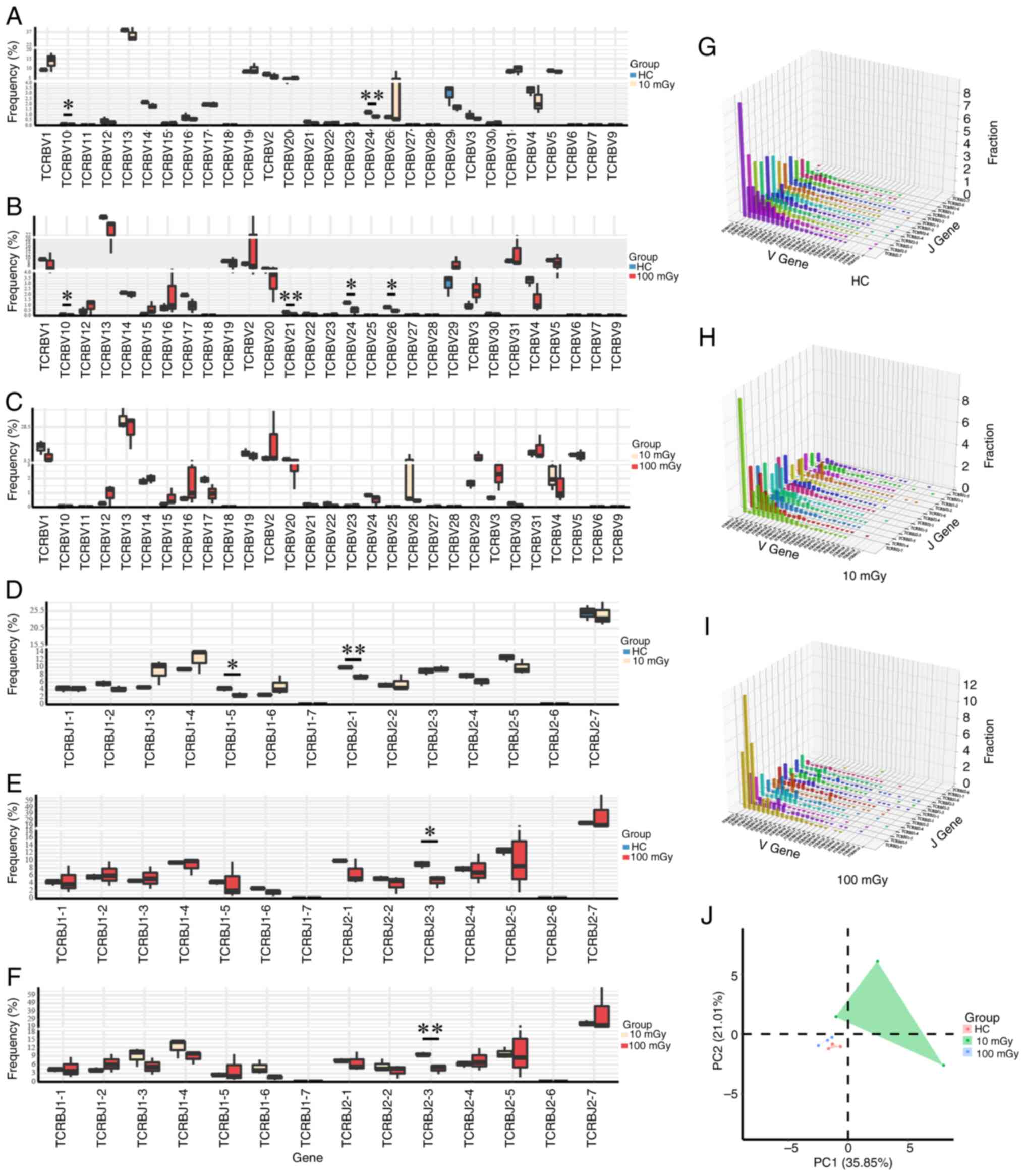

Length distribution and overlap degree

of TCRβ CDR3

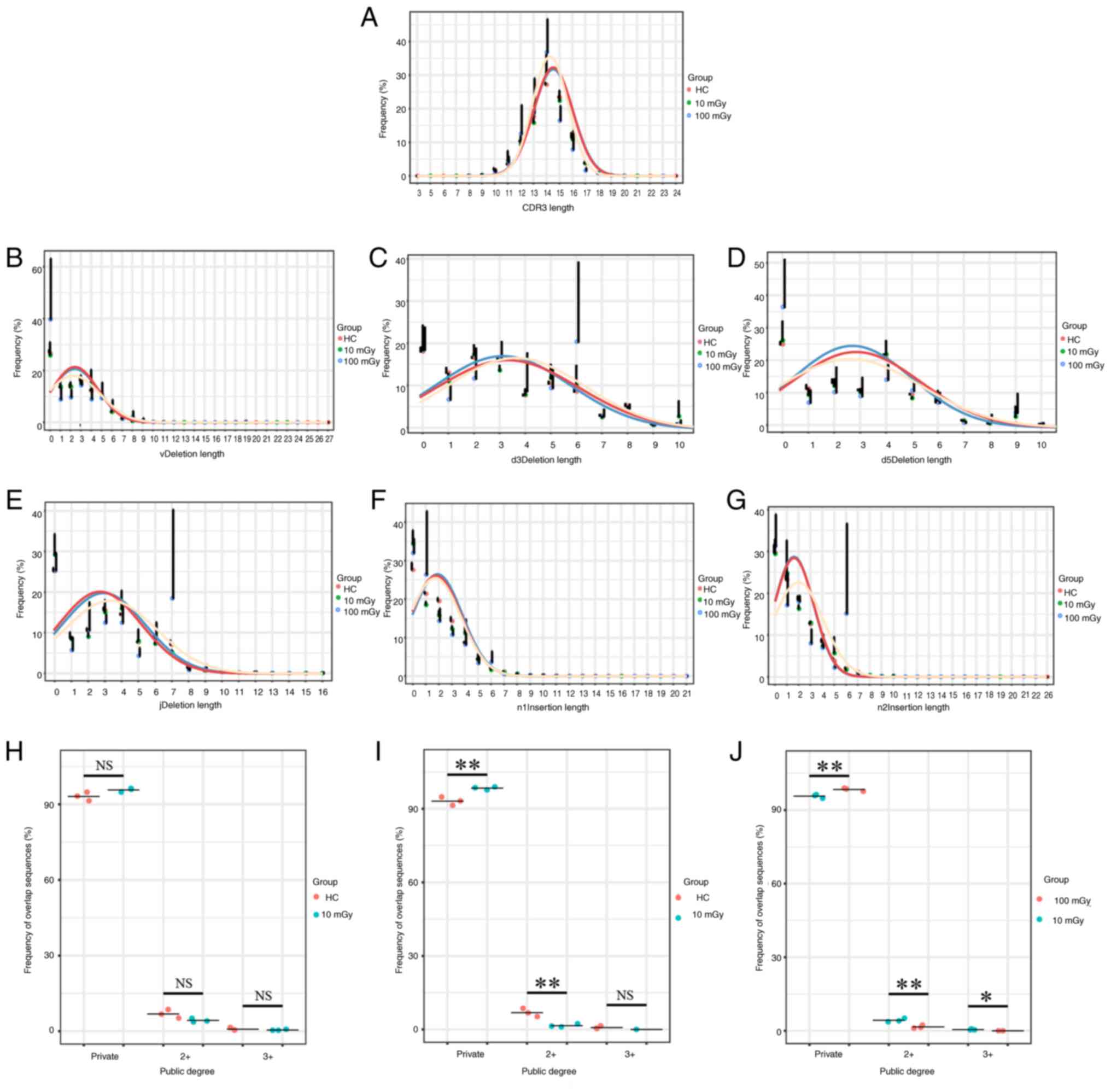

In the present study, the CDR3 length distribution

in the 10 mGy-exposed and 100 mGy-exposed groups was not

significantly different from that in the HC group, although some

changes were observed (Fig. 5A). To

understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of

radiation on TCRs, six recombination positions (vDeletion,

d3Deletion, d5Deletion, jDeletion, n1Insertion and n2Insertion) for

both in-frame and out-of-frame insertion/deletion (InDels) events

were analyzed. The length distributions for the six recombination

events (indels) were similar between the 100 mGy-exposed and HC/10

mGy-exposed groups in the post-selection (Fig. 5B-G) and pre-selection repertoires

(Fig. S2). A previous study has

demonstrated that the TCRβ CDR3 length has been associated with the

degree of sequence sharing (34).

Thus, the overlap indices of TCRβ nucleotide sequences were

calculated for each group. Based on the shared degree of amino acid

sequences between samples, the samples were divided into the

following three groups: Private, co-owned by ≥2 and co-owned by ≥3

samples. The results indicated that, as the radiation dose

increased, the percentage of private sequences was significantly

increased and the degree of overlap was significantly decreased

(Fig. 5H-J).

| Figure 5.Altered CDR3 length distribution,

InDel patterns and public degree in the RT group. (A) The changes

in the CDR3 length in the radiation group mice from the 10 and 100

mGy groups were compared with those of the HC group. (B-G) TCRβ

CDR3 sequences from the radiotherapy and HC groups in the

post-selection repertoire were analyzed for the frequency of

clonotypes with a specific number of InDels at each of the six

rearrangement sites: (B) vDdel, (C) d3Del, (D) d5Del, (E) jDel, (F)

n1Ins and (G) n2Ins. (H-J) Overlap indices were calculated from 9

HC, 9 mice with 10 mGy and 9 mice with 100 mGy, where (H) is the

comparison between HC group mice and mice receiving 10 mGy

radiation, (I) is the comparison between HC group mice and mice

receiving 100 mGy radiation and (J) is the comparison between mice

receiving 10 mGy radiation and mice receiving 100 mGy radiation.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD and the means between the two

groups were compared using the unpaired t-test or the Mann-Whitney

U test. One-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare

group means across three or more groups and corrected for multiple

comparisons using Bonferroni. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. TCRβ,

T-cell receptor β-chain; CDR3, complementarity-determining region

3; InDel, insertions and deletions; NS, not significant; HC,

healthy control. |

Radiation alters the usage frequency

of the TCRβ chain variable (TRBV) and TCRβ chain joining (TRBJ)

gene segments

To identify whether there was a skewed and

restricted VDJ segment usage following radiation, the usage

frequency of the TRBV and TRBJ genes in the radiation-exposed group

was compared with that in the HC group in both the post-selection

(Fig. 6A-F) and pre-selection

(Fig. S3A-F) repertoires. For the

post-selection repertoire, the usage frequency of TRBV10 and TRBV24

in the radiation-exposed groups was significantly lower than that

in the HC group. For the pre-selection repertoires, the usage

frequencies of TRBJ1-2, TRBJ1-5 and TRBJ1-6 in the

radiation-exposed groups were lower than that in the HC group, but

not all showed statistical differences. Furthermore, through PCA,

the radiation-exposed mice can be distinguished from the HC mice

based on the usage of TRBV genes, in the post-selection (Fig. 6J) and pre-selection (Fig. S3J) repertoires. Furthermore, the

three-dimensional landscapes of TRBV and TRBJ gene usage were

plotted. In the post-selection (Fig.

6G-I) repertoires, the top three V-J combinations in the 10

mGy-exposed group were TRBV13-TRBJ2-7, TRBV13-TRBJ1-4 and

TRBV13-TRBJ2-5, while those in the 100 mGy-exposed group were

TRBV13-TRBJ2-7, TRBV2-TRBJ2-7 and TRBV31-TRBJ2-7. The top three V-J

combinations in the HC group were TRBV13-TRBJ2-7, TRBV13-TRBJ2-5

and TRBV13-TRBJ2-1 (Fig. 6G).

Additionally, in the pre-selection (Fig. S3G-I) repertoires, the top three V-J

combinations in the 10 mGy-exposed group were TRBV31-TRBJ2-4,

TRBV13-TRBJ2-7 and TRBV13-TRBJ2-1, while those in the 100

mGy-exposed group were TRBV13-TRBJ2-7, TRBV5-TRBJ1-4 and

TRBV13-TRBJ2-4. The top three V-J combinations in the HC group were

TRBV13-TRBJ2-7, TRBV4-TRBJ2-7 and TRBV13-TRBJ2-5 (Fig. S3G).

Discussion

At present, cancer remains a primary public health

problem. According to the International Agency for Research on

Cancer, 19.88 million new global cancer cases and 9.74 million

cancer-related deaths were reported in 2022 (3). RT is one of the most important

treatment strategies for cancer (40). The clinical application of various

immunomodulatory drugs has contributed to the field of cancer

immunotherapy, achieving notable progress in the design of

effective immunotherapy regimens. According to relevant research

reports, there is a correlation between neoantigen burden and

clinical benefits when using CTLA-4 blocking monoclonal antibodies

to treat patients with melanoma (41,42),

and similar associations have also been reported in patients with

lung cancer receiving anti-PD-1 treatment (43). However, to the best of our

knowledge, there is currently no systematic understanding of the

heterogeneity in immune cells following the use of these treatment

methods for cancer. The present study analyzed the TCRβ repertoire

from a public dataset of tumor tissues from mice treated with RT

and/or anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 therapies, as well as in peripheral

blood mononuclear cells of NSG mice 6 months after transplantation

with HSCs isolated from CBA/HmCherry mice exposed to

radiation doses of 0, 10 and 100 mGy for 7 days.

Analyses of the TCRβ repertoire of the RT and

anti-CTLA-4 treated cancer samples revealed that the diversity of

the TCRβ repertoire in the RT and RT + anti-CTLA-4 groups was

significantly lower than that in the control group, especially in

the RT + anti-CTLA-4 group. Although not all differences were

significant, some changes were observed. This may be due to the

synergistic inhibitory effects of RT and anti-CTLA-4 therapy on T

cells. The arrest of T cells in contact with tumor cells is

dependent on major histocompatibility complex class I (44). A previous study indicated that the

TCRβ repertoire diversity is positively associated with the

polymorphism of human leukocyte antigen class I loci (45) and the present study findings further

confirmed these conclusions. Furthermore, a short biased TCRβ CDR3

length may lead to an increased degree of sequence sharing as short

sequences (with limited variability in sequence combinations)

increase the probability of two TCRβ CDR3 sequences being

coincidentally identical. The present study results are contrary to

those presented by Rudqvist et al (26), who reported that the overlap between

mice receiving RT combined with anti-CTLA-4 therapy was

significantly reduced compared with mice receiving RT alone.

TCR diversity is key for neoantigen recognition

(46,47). In the present study, compared with

the control group, the TCRβ repertoire diversity of the in-field

tumors was lower in the RT and RT + anti-PD-1 groups, although not

all differences were statistically significant. However, the TCRβ

repertoire diversity in the anti-PD-1 group was comparable with

that in the control group. Additionally, analysis of the diversity

of the TCRβ repertoire in the out-of-field tumors revealed that the

TCRβ repertoire diversity in the RT group was higher than that in

the control and RT + anti-PD-1 groups. RT can enhance the mobility

of T cells toward the localized treatment site of tumors and

augment existing anticancer T cell responses. The combination of RT

and anti-PD-1 therapy facilitates the regression of both local and

distant tumor lesions (27). A

recent study reported that the combination of RT and anti-PD-1

therapy can promote the circulation of T cell clones between the

peripheral blood and tumor tissues (48). Peripheral blood serves as a

reservoir for T cell clones, which contributes to the diversity of

the TCR repertoire of tumor tissue. We hypothesize that the

diversity of the TCR in the in-field tumors of the RT and RT +

anti-PD-1 groups was lower than that in the control group due to

the RT-induced potent local inflammatory response against tumor

tissue. This leads to an enhanced antitumor immune response and

increased utilization of the TCR. Additionally, the antitumor

immune response of off-site tumors may be slightly delayed compared

with on-site tumors. A key feature of the TCRβ repertoire is the

distribution of the CDR3 length. Epitope-specific T cell

repertoires often have a bias in CDR3 length (37,49,50).

Compared with the control group, the clonotypes in the in-field

tumors of the anti-PD-1 and the RT + anti-PD-1 groups shifted

toward longer clonotypes. However, the CDR3 length in the RT group

was comparable with that in the control group. Consistent with the

CDR3 length in some in-field tumors, the CDR3 length in the

anti-PD-1 group was longer than that in the control group in the

out-of-field tumors. These results may be due to the random

insertion of a large number of nucleotides into the CDR3 region in

the presence of terminal deoxynucleotidase after cancer treatment,

which increases CDR3 length (16).

The diverse TCRs provide protection to the human

body, shielding it from various external pathogens and internal

cancer cells (51). However, in the

present study, further investigation of the TCRβ repertoire

characteristics in mice exposed to different radiation doses

revealed that, as the radiation dose increased, the TCRβ diversity

in mice decreased while the degree of clonal expansion increased.

This may be associated with immune system damage caused by reduced

TCRβ diversity after radiation exposure, further confirming the

findings by Hollingsworth et al (52), in which it was reported that

radiation damage leads to impaired immune response and a decrease

in T cell repertoire diversity. Additionally, in the present study,

the CDR3 length and InDel length distribution were not

significantly different between the radiation-exposed and HC

groups. Furthermore, as the radiation dose increased, the

percentage of private sequences was significantly increased and the

degree of overlapping sequences was significantly decreased. The

shared TCRβ clonotypes among individuals is associated with

enhanced cross-reactivity toward potentially related antigens,

which is considered key for pathogen-specific responses and

infection control (53–56). Furthermore, in the present study,

the usage frequencies of TRBV/J segments significantly varied

between the radiation-exposed and HC groups in both the

pre-selection and post-selection repertoires. The biased usage of

TRBV/J segments may result from radiation-induced DNA rearrangement

(57). Upon radiation exposure,

activated T cells undergo clonal expansion to maintain

physiological functions. However, immune cell composition remains

stable. An increase in the number of dominant T cells can suppress

the proliferation of other T cells (58). Therefore, radiation exposure may

have increased the proportions of some TRBV/J genes but decreased

the proportion of other genes.

The results of the present study indicated that

different treatments decreased the TCRβ repertoire diversity of

mice. RT may be the main factor contributing to this decreased

diversity of the TCRβ repertoire. The decreased TCRβ diversity may

weaken the ability of the immune system to recognize and clear

tumor cells, affecting treatment efficacy. RT may affect the

diversity of TCRβ repertoire through different mechanisms. First,

radiation may directly damage and kill the lymphocytes in the TME,

reduce the number of T cells and consequently decrease TCRβ

diversity (59). Second, radiation

may affect thymic function. The thymus is the site for T cell

development and maturation. RT-induced thymic tissue damage can

adversely affect T cell production and TCRβ rearrangement, which

decreases TCRβ diversity (60).

Third, RT may induce alterations in the TME, such as eliciting

inflammatory responses and increasing the number of

immunosuppressive cells. These changes may adversely affect the

infiltration and function of T cells, indirectly decreasing the

diversity of TCRβ (61,62). Future studies should consider

reducing the negative impact of RT on TCRβ diversity through the

optimization of RT. Radiation dose may be decreased to a level that

minimizes direct damage to lymphocytes without compromising

treatment efficacy (63). A

previous study has demonstrated that fractionated low-dose RT is

efficacious for the activation of the immune system, mitigating the

negative impact on TCRβ diversity (63). Furthermore, adoptive T cell therapy

can be used after RT. Adoptive T cell therapy involves re-infusing

tumor-specific T cells expanded in vitro into the body of

the patient to enhance TCRβ diversity and antitumor activity

(64). The management of TCRβ

diversity is dependent on multiple factors, such as tumor type,

staging and patient immune status. Thus, different strategies can

be employed to overcome these issues. For example, thymus function

can be enhanced. The thymus is a key organ for T cell development

and diversification. The improvement of the thymic microenvironment

(such as supplementing IL-7, growth hormone and thymosin) or the

suppression of age-related thymic atrophy will promote the

generation of initial T cells and the maintenance of TCR repertoire

diversity (65–67). Furthermore, strategies can be

adopted to regulate gut microbiota. The gut microbiota affects T

cell differentiation by modulating the immune microenvironment

(68). For example, probiotics or

fecal transplantation may indirectly enrich the TCR repertoire

through antigen cross-reactivity (69). Treatment effectiveness may vary

depending on the type of tumor, individual patient and treatment

plan, highlighting the importance of developing personalized

treatment plans. Treatment plans for patients with cancer can be

personalized to achieve optimal therapeutic effects using two

strategies: i) TCR sequencing technology can be used to analyze the

TCRβ diversity of the patient and evaluate their immune status

(70,71); and ii) the identification of

biomarkers associated with TCRβ diversity can be used to predict

the efficacy of RT and immunotherapy (72,73).

The present study has several limitations. The

sample size was small; hence, the conclusions of the present study

need to be validated using a larger sample size. Additionally, the

types of cancer involved in the present study are limited and

future research needs to be conducted on more categories of cancer

samples to confirm the conclusions. Furthermore, this was a

cross-sectional study that evaluated the TCRβ repertoire at a

specific time point. The dynamic changes of the TCRβ repertoire

during treatment should be evaluated in the future, which will aid

in the identification of the optimal treatment window. Finally, TCR

sequencing, which was used to determine TCR rearrangement, does not

fully represent the functionality of T cells. Therefore, future

research needs to combine more functional experiments, such as i)

Cytokine release experiments: detecting the types and quantities of

cytokines released by T cells after stimulation to evaluate the

activation status of T cells; and ii) cytotoxicity assay: Evaluate

the ability of T cells to kill tumor cells.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

the TCRβ repertoire may serve as an ideal predictive biomarker for

the efficacy of combination therapies. In the future, further

research should be conducted on: i) The molecular mechanisms by

which the CDR3 length is significantly shorter under RT and

significantly longer under immunotherapy, as well as the role of

changes in CDR3 length in tumor treatment and prognosis; and ii)

identifying methods that can be used to maintain and improve the

diversity of TCR profiles in RT and immunotherapy. Future studies

may explore and evaluate the potential mechanisms underlying

antitumor immune responses to address key challenges in clinical

treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the Guangxi

Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2024GXNSFAA 010096),

Innovation Training Program for College Students (grant nos.

202410601013 and S202410601182), Guilin Science Research and

Technology Development Project (grant nos. 20210218-2 and

20220139-13-2) and Guangxi Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunology and

Microenvironmental Regulation (grant nos. 2023KF006, 3030302213 and

2021KF001).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XY and WW curated the data, performed the formal

analysis, prepared and wrote the original draft and analyzed and

interpreted the data. XY and WW confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. ZF, BZ, YL and FY participated in data analysis and

reviewed and edited the manuscript. CZ and MO reviewed and edited

the manuscript as well as supervised and conceptualized the present

study. SL conceptualized the present study, performed the formal

analysis, designed the present study methodology and supervised and

aided with the visualization of data. XH conceptualized the present

study, performed the formal analysis, obtained funding, designed

methodology and supervised and conceived the present study. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

RT

|

radiotherapy

|

|

TCRβ

|

T-cell receptor β chain

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

CDR3

|

complementarity-determining region

3

|

|

CTLA-4

|

cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated

antigen-4

|

|

PD-1

|

programmed cell death-1

|

|

HSC

|

hematopoietic stem cell

|

|

NSG

|

NOD scid γ

|

|

TRBV

|

TCR β chain variable gene

|

|

TRBJ

|

TCR β chain joining gene

|

References

|

1

|

Chen Z, Ma Y, Hua J, Wang Y and Guo H:

Impacts from economic development and environmental factors on life

expectancy: A comparative study based on data from both developed

and developing countries from 2004 to 2016. Int J Environ Res

Public Health. 18:85592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tchkonia T, Palmer AK and Kirkland JL: New

horizons: Novel approaches to enhance healthspan through targeting

cellular senescence and related aging mechanisms. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 106:e1481–e1487. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cao W, Qin K, Li F and Chen W:

Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality: An

analysis of GLOBOCAN 2022. Chin Med J (Engl). 137:1407–1413. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM and Jemal A:

Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends-an update.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 25:16–27. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K,

Chen R, Li L, Wei W and He J: Cancer incidence and mortality in

China, 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2:1–9. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N and Chen WQ:

Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A

secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J

(Engl). 134:783–791. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bhattacharya S and Asaithamby A:

Repurposing DNA repair factors to eradicate tumor cells upon

radiotherapy. Transl Cancer Res. 6 (Suppl 5):S822–S839. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mortezaee K and Najafi M: Immune system in

cancer radiotherapy: Resistance mechanisms and therapy

perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 157:1031802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Watanabe T, Sato GE, Yoshimura M, Suzuki M

and Mizowaki T: The mutual relationship between the host immune

system and radiotherapy: Stimulating the action of immune cells by

irradiation. Int J Clin Oncol. 28:201–208. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hoffman RM: Back to the future: Are

tumor-targeting bacteria the next-generation cancer therapy?

Methods Mol Biol. 1317:239–260. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang Y and Zhang Z: The history and

advances in cancer immunotherapy: Understanding the characteristics

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic

implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 17:807–821. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N,

Dewyngaert JK, Babb JS, Formenti SC and Demaria S: Fractionated but

not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal

effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res.

15:5379–5388. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Verbrugge I, Hagekyriakou J, Sharp LL,

Galli M, West A, McLaughlin NM, Duret H, Yagita H, Johnstone RW,

Smyth MJ and Haynes NM: Radiotherapy increases the permissiveness

of established mammary tumors to rejection by immunomodulatory

antibodies. Cancer Res. 72:3163–3174. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hou X, Yang Y, Chen J, Jia H, Zeng P, Lv

L, Lu Y, Liu X and Diao H: TCRβ repertoire of memory T cell reveals

potential role for Escherichia coli in the pathogenesis of primary

biliary cholangitis. Liver Int. 39:956–966. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hou XL, Wang L, Ding YL, Xie Q and Diao

HY: Current status and recent advances of next generation

sequencing techniques in immunological repertoire. Genes Immun.

17:153–164. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hou X, Lu C, Chen S, Xie Q, Cui G, Chen J,

Chen Z, Wu Z, Ding Y, Ye P, et al: High throughput sequencing of T

cell antigen receptors reveals a conserved TCR repertoire. Medicine

(Baltimore). 95:e28392016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hou X, Wang M, Lu C, Xie Q, Cui G, Chen J,

Du Y, Dai Y and Diao H: Analysis of the repertoire features of TCR

beta chain CDR3 in human by high-throughput sequencing. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 39:651–667. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zvyagin IV, Pogorelyy MV, Ivanova ME,

Komech EA, Shugay M, Bolotin DA, Shelenkov AA, Kurnosov AA,

Staroverov DB, Chudakov DM, et al: Distinctive properties of

identical twins' TCR repertoires revealed by high-throughput

sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:5980–5985. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Larimore K, McCormick MW, Robins HS and

Greenberg PD: Shaping of human germline IgH repertoires revealed by

deep sequencing. J Immunol. 189:3221–3230. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Robins HS, Campregher PV, Srivastava SK,

Wacher A, Turtle CJ, Kahsai O, Riddell SR, Warren EH and Carlson

CS: Comprehensive assessment of T-cell receptor beta-chain

diversity in alphabeta T cells. Blood. 114:4099–4107. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Robins HS, Srivastava SK, Campregher PV,

Turtle CJ, Andriesen J, Riddell SR, Carlson CS and Warren EH:

Overlap and effective size of the human CD8+ T cell receptor

repertoire. Sci Transl Med. 2:47ra642010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang J, Ji Z and Smith KN: Analysis of

TCR β CDR3 sequencing data for tracking anti-tumor immunity.

Methods Enzymol. 629:443–464. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li S, Sun J, Allesøe R, Datta K, Bao Y,

Oliveira G, Forman J, Jin R, Olsen LR, Keskin DB, et al: RNase

H-dependent PCR-enabled T-cell receptor sequencing for highly

specific and efficient targeted sequencing of T-cell receptor mRNA

for single-cell and repertoire analysis. Nat Protoc. 14:2571–2594.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Baumeister SH, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G and

Sharpe AH: Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Annu

Rev Immunol. 34:539–573. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Candéias SM, Mika J, Finnon P, Verbiest T,

Finnon R, Brown N, Bouffler S, Polanska J and Badie C: Low-dose

radiation accelerates aging of the T-cell receptor repertoire in

CBA/Ca mice. Cell Mol Life Sci. 74:4339–4351. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rudqvist NP, Pilones KA, Lhuillier C,

Wennerberg E, Sidhom JW, Emerson RO, Robins HS, Schneck J, Formenti

SC and Demaria S: Radiotherapy and CTLA-4 blockade shape the TCR

repertoire of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Cancer Immunol Res.

6:139–150. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dovedi SJ, Cheadle EJ, Popple AL, Poon E,

Morrow M, Stewart R, Yusko EC, Sanders CM, Vignali M, Emerson RO,

et al: Fractionated radiation therapy stimulates antitumor immunity

mediated by both resident and infiltrating polyclonal T-cell

populations when combined with PD-1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res.

23:5514–5526. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Robins H, Desmarais C, Matthis J,

Livingston R, Andriesen J, Reijonen H, Carlson C, Nepom G, Yee C

and Cerosaletti K: Ultra-sensitive detection of rare T cell clones.

J Immunol Methods. 375:14–19. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Carlson CS, Emerson RO, Sherwood AM,

Desmarais C, Chung MW, Parsons JM, Steen MS,

LaMadrid-Herrmannsfeldt MA, Williamson DW, Livingston RJ, et al:

Using synthetic templates to design an unbiased multiplex PCR

assay. Nat Commun. 4:26802013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bolotin DA, Shugay M, Mamedov IZ,

Putintseva EV, Turchaninova MA, Zvyagin IV, Britanova OV and

Chudakov DM: MiTCR: Software for T-cell receptor sequencing data

analysis. Nat Methods. 10:813–814. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Elhanati Y, Sethna Z, Callan CG Jr, Mora T

and Walczak AM: Predicting the spectrum of TCR repertoire sharing

with a data-driven model of recombination. Immunol Rev.

284:167–179. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Pogorelyy MV, Minervina AA, Chudakov DM,

Mamedov IZ, Lebedev YB, Mora T and Walczak AM: Method for

identification of condition-associated public antigen receptor

sequences. Elife. 7:e330502018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Murugan A, Mora T, Walczak AM and Callan

CG Jr: Statistical inference of the generation probability of

T-cell receptors from sequence repertoires. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

109:16161–16166. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gomez-Tourino I, Kamra Y, Baptista R,

Lorenc A and Peakman M: T cell receptor β-chains display abnormal

shortening and repertoire sharing in type 1 diabetes. Nat Commun.

8:17922017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hou X, Zeng P, Chen J and Diao H: No

difference in TCRβ repertoire of CD4+ naive T cell between patients

with primary biliary cholangitis and healthy control subjects. Mol

Immunol. 116:167–173. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hou X, Zeng P, Zhang X, Chen J, Liang Y,

Yang J, Yang Y, Liu X and Diao H: Shorter TCR β-chains are highly

enriched during thymic selection and antigen-driven selection.

Front Immunol. 10:2992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Huang C, Li X, Wu J, Zhang W, Sun S, Lin

L, Wang X, Li H, Wu X, Zhang P, et al: The landscape and diagnostic

potential of T and B cell repertoire in immunoglobulin A

nephropathy. J Autoimmun. 97:100–107. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu Y, Zhu H, Zhang Q and Zhao Y: Clonal

analysis of peripheral blood T cells in patients with hashimoto's

thyroiditis at different stages using TCR sequencing.

Immunobiology. 230:1528902025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Venturi V, Kedzierska K, Turner SJ,

Doherty PC and Davenport MP: Methods for comparing the diversity of

samples of the T cell receptor repertoire. J Immunol Methods.

321:182–195. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang Z, Tang Y, Tan Y, Wei Q and Yu W:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts in radiotherapy: Challenges and new

opportunities. Cell Commun Signal. 17:472019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla

SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, Sucker A, Hillen U, Foppen MHG, Goldinger

SM, et al: Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in

metastatic melanoma. Science. 9:207–211. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chan TA, Wolchok JD and Snyder A: Genetic

basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl

J Med. 12:19842015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg

P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, et al: Cancer

immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1

blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 3:124–128. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ruocco MG, Pilones KA, Kawashima N, Cammer

M, Huang J, Babb JS, Liu M, Formenti SC, Dustin ML and Demaria S:

Suppressing T cell motility induced by anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy

improves antitumor effects. J Clin Invest. 122:3718–3730. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Krishna C, Chowell D, Gönen M, Elhanati Y

and Chan TA: Genetic and environmental determinants of human TCR

repertoire diversity. Immun Ageing. 17:262020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Riaz N, Havel JJ, Makarov V, Desrichard A,

Urba WJ, Sims JS, Hodi FS, Martín-Algarra S, Mandal R, Sharfman WH,

et al: Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy

with nivolumab. Cell. 171:934–949.e916. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hebeisen M, Allard M, Gannon PO, Schmidt

J, Speiser DE and Rufer N: Identifying individual T cell receptors

of optimal avidity for tumor antigens. Front Immunol. 6:5822015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yan C, Ma X, Guo Z, Wei X, Han D, Zhang T,

Chen X, Cao F, Dong J, Zhao G, et al: Time-spatial analysis of T

cell receptor repertoire in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

patients treated with combined radiotherapy and PD-1 blockade.

Oncoimmunology. 11:20256682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Pickman Y, Dunn-Walters D and Mehr R: BCR

CDR3 length distributions differ between blood and spleen and

between old and young patients, and TCR distributions can be used

to detect myelodysplastic syndrome. Phys Biol. 10:0560012013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu S, Hou XL, Sui WG, Lu QJ, Hu YL and

Dai Y: Direct measurement of B-cell receptor repertoire's

composition and variation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes

Immun. 18:22–27. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Weng NP: Numbers and odds: TCR repertoire

size and its age changes impacting on T cell functions. Semin

Immunol. 69:1018102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hollingsworth BA, Aldrich JT, Case CM Jr,

DiCarlo AL, Hoffman CM, Jakubowski AA, Liu Q, Loelius SG, PrabhuDas

M, Winters TA and Cassatt DR: Immune dysfunction from radiation

exposure. Radiat Res. 200:396–416. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Price DA, Asher TE, Wilson NA, Nason MC,

Brenchley JM, Metzler IS, Venturi V, Gostick E, Chattopadhyay PK,

Roederer M, et al: Public clonotype usage identifies protective

Gag-specific CD8+ T cell responses in SIV infection. J Exp Med.

206:923–936. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Venturi V, Quigley MF, Greenaway HY, Ng

PC, Ende ZS, McIntosh T, Asher TE, Almeida JR, Levy S, Price DA, et

al: A mechanism for TCR sharing between T cell subsets and

individuals revealed by pyrosequencing. J Immunol. 186:4285–4294.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhao Y, Nguyen P, Ma J, Wu T, Jones LL,

Pei D, Cheng C and Geiger TL: Preferential use of public TCR during

autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 196:4905–4914. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Hou X, Wang G, Fan W, Chen X, Mo C, Wang

Y, Gong W, Wen X, Chen H, He D, et al: T-cell receptor repertoires

as potential diagnostic markers for patients with COVID-19. Int J

Infect Dis. 113:308–317. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Forrester HB and Radford IR: Ionizing

radiation-induced chromosomal rearrangements occur in

transcriptionally active regions of the genome. Int J Radiat Biol.

80:757–767. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Sui W, Hou X, Zou G, Che W, Yang M, Zheng

C, Liu F, Chen P, Wei X, Lai L and Dai Y: Composition and variation

analysis of the TCR β-chain CDR3 repertoire in systemic lupus

erythematosus using high-throughput sequencing. Mol Immunol.

67:455–464. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kuehm LM, Wolf K, Zahour J, DiPaolo RJ and

Teague RM: Checkpoint blockade immunotherapy enhances the frequency

and effector function of murine tumor-infiltrating T cells but does

not alter TCRβ diversity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 68:1095–1106.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Valença-Pereira F, Sheridan RM, Riemondy

KA, Thornton T, Fang Q, Barret B, Paludo G, Thompson C, Collins P,

Santiago M, et al: Inactivation of GSK3β by Ser(389)

phosphorylation prevents thymocyte necroptosis and impacts Tcr

repertoire diversity. Cell Death Differ. 32:880–898. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Kershaw MH, Devaud C, John LB, Westwood JA

and Darcy PK: Enhancing immunotherapy using chemotherapy and

radiation to modify the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology.

2:e259622013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Huang J and Li JJ: Multiple dynamics in

tumor microenvironment under radiotherapy. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1263:175–202. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

D'Alonzo RA, Keam S, Gill S, Rowshanfarzad

P, Nowak AK, Ebert MA and Cook AM: Fractionated low-dose

radiotherapy primes the tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy in

a murine mesothelioma model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 74:442025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Pituch KC, Miska J, Krenciute G, Li G,

Panek WK, Gottschalk S and Balyasnikova IV: P06.01 Functional

analysis of IL13Rα2-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells in

immunocompetent mouse of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 19:iii48–iii49.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Hsieh J, Ng S, Bosinger S, Wu JH, Tharp

GK, Garcia A, Hossain MS, Yuan S, Waller EK and Galipeau J: A GMCSF

and IL7 fusion cytokine leads to functional thymic-dependent T-cell

regeneration in age-associated immune deficiency. Clin Transl

Immunology. 4:e372015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Savino W, Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Lepletier A

and Dardenne M: Hormonal control of T-cell development in health

and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 12:77–89. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Besman M, Zambrowicz A and Matwiejczyk M:

Review of thymic peptides and hormones: From their properties to

clinical application. International Journal of Peptide Research and

Therapeutics. 31:102024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Kim KS: Regulation of T cell repertoires

by commensal microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

12:10043392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Bessell CA, Isser A, Havel JJ, Lee S, Bell

DR, Hickey JW, Chaisawangwong W, Glick Bieler J, Srivastava R, Kuo

F, et al: Commensal bacteria stimulate antitumor responses via T

cell cross-reactivity. JCI Insight. 5:e1355972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Fang M, Miao Y, Zhu L, Mei Y, Zeng H, Luo

L, Ding Y, Zhou L, Quan X, Zhao Q, et al: Age-related dynamics and

spectral characteristics of the tcrβ repertoire in healthy

children: Implications for immune aging. Aging Cell. 24:e144602025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chen M, Su Z and Xue J: Targeting T-cell

aging to remodel the aging immune system and revitalize geriatric

immunotherapy. Aging Dis. 15:10.14336/AD.2025.0061. 2025.

|

|

72

|

Han J, Duan J, Bai H, Wang Y, Wan R, Wang

X, Chen S, Tian Y, Wang D, Fei K, et al: TCR repertoire diversity

of peripheral PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells predicts clinical outcomes

after immunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancer Immunol Res. 8:146–154. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wang J, Bie Z, Zhang Y, Li L, Zhu Y, Zhang

Y, Nie X, Zhang P, Cheng G, Di X, et al: Prognostic value of the

baseline circulating T cell receptor β chain diversity in advanced

lung cancer. Oncoimmunology. 10:18996092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|