Introduction

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed

malignant tumor and a major cause of cancer-related death globally

(1). Non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC) constitutes >85% of all lung cancer cases, which can be

further classified as lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), large cell

carcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) (2,3). In

recent years, surgery, chemotherapy and medication have been the

main treatment strategies for lung cancer, but the prognosis for

patients with this disease remains poor (3). To improve patient survival, the

development of new anticancer drugs with lower toxicity and fewer

side effects are required for the treatment of lung cancer.

Tanshinone IIA (TSIIA) is a natural extract derived

from Danshen (Salviae miltiorrhizae Bunge). Sodium TSIIA

sulfate (STS) is an aqueous solution of TSIIA after sulfonation and

is the sodium sulfate salt form of TSIIA. Compared with the

lipophilic properties of TSIIA, the introduction of the sulfate

group in STS enhances its solubility in aqueous media, which

improves its absorption and distribution within the body. Despite

the structural differences between the molecules, STS, as a

derivative of TSIIA, retains certain pharmacological activities of

TSIIA, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antitumor effects

(4). As previously reported, TSIIA

exerts antitumor effects on various malignant tumors, such as

esophageal, colorectal, prostate and gastric cancer (4,5).

Notably, the therapeutic effects of TSIIA on lung cancer have been

reported, and TSIIA markedly decreases NSCLC cell viability and

colony formation (6). In addition,

STS treatment has been shown to reduce LUAD cell malignant

behaviors (7). However, the precise

mechanism by which TSIIA functions in lung cancer remains

unclear.

Histone acetylation is a specific type of

modification in which the lysine residue at the tail of a histone

is acetylated and deacetylated by histone acetyltransferase (HAT)

and histone deacetylase (HDAC), respectively (8). Alterations in histone acetylation are

closely related to cancer progression (9). For instance, upregulation of histone

H3 lysine 18 acetylation (H3K18ac) inhibits lung cancer cell

viability, colony formation and migration (10). Additionally, celestrol inhibits lung

cancer growth by inducing histone acetylation and synergistically

acting with a HDAC inhibitor (11).

As previously reported, TSIIA protects against cerebral ischemia

reperfusion injury by upregulating H3K18ac and H4K8ac (12). Therefore, it could be suggested that

TSIIA may inhibit lung cancer development by upregulating H3K18ac

and H4K8ac.

RING finger protein 123 (RNF123), also known as

KPC1, is an E3 ubiquitin ligase component of the

ubiquitin-proteasome system that controls certain important cancer

pathways and processes (13). The

tumor suppressor functions of RNF123 have been previously reported

(13). RNF123 is expressed at low

levels in glioblastoma tumors and its low expression is a

predictive factor for poor overall survival (14). Nevertheless, at present, the role of

RNF123 in lung cancer is not well understood. To address this gap,

the present study aimed to identify a possible novel therapy for

lung cancer and elucidate its mechanism of action by investigating

RNF123 expression in LUAD and LUSC and assessing the potential role

of promoter histone acetylation (H3K18ac, H4K8ac and H3K27ac) in

regulating its transcription using bioinformatic methods.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

The A549, H1975, H1299, H460 and PC-9 lung cancer

cell lines and the BEAS-2B normal human bronchial epithelial cell

line were obtained from ATCC. All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) comprising 10% FBS (Gibco

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 5% CO2 at 37°C. For STS

treatment, A549 and H1975 cells were incubated with 0, 5, 10, 20,

40 and 80 µM STS (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 24 h.

Cell transfection

The short hairpin RNAs [shRNAs; sh-negative control

(NC) sense, 5′-GTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′ and antisense,

5′-ACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAAC-3′; sh-RNF123 sense,

5′-CCCTCAAAGATGACCTTGCTT-3′ and antisense,

5′-AAGCAAGGTCATCTTTGAGGG-3′; and sh-lysine acetyltransferase 2B

(KAT2B) sense, 5′-GCTGGGACAATTTCATACAA-3′ and antisense,

5′-TTGTATGAAATTGTCCCAGC-3′], the overexpression (oe) plasmids

(oe-RNF123 and oe-KAT2B), pCDNA3.1-CMV-RNF123 (human)-GFP-Neo and

pCDNA3.1-CMV-KAT2B (human)-GFP-Neo, and their respective negative

controls (empty pCDNA3.1 vector) were purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. The overexpression vectors and shRNAs were

transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly, 2.5 µg of nucleic acid was used

per well of a 6-well plate. Transfection complexes were formed at

room temperature for 15 min and then added to cells, which were

incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were incubated for

48 h post-transfection before subsequent experimentation. In

addition to sh-NC and oe-NC controls, mock-transfected control

cells (cultured in parallel with transfection reagent only, without

nucleic acid) were included in all assays to serve as the baseline

control group.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from A549 and H1975 cells

using TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). cDNA

synthesis was carried out using the SuperScript™ IV

First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed using

the PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time

PCR System with the following thermocycling conditions: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for

15 sec and 60°C for 1 min, with a final melting curve analysis from

65°C to 95°C.GAPDH was employed as the reference gene. The data

were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (15). The primers used in the present study

were as follows: RNF123 forward (F), 5′-TCTTTCTCCCGCAAGAGCTAT-3′

and reverse (R), 5′-AACTGGTCCAAATGTTCTGGC-3′; KAT2B F,

5′-CGAATCGCCGTGAAGAAAGC-3′ and R, 5′-CTTGCAGGCGGAGTACACT-3′; and

GAPDH F, 5′-AGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTT-3′ and R,

5′-TGACGGTGCCATGGAATTTG-3′.

Western blotting

For nuclear extraction, cells were lysed in

hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM

MgCl2, 0.1% NP-40, protease inhibitors) on ice for 15

min, nuclei were pelleted at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, washed

once with hypotonic buffer without NP-40 and then extracted with

high-salt buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM

MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, protease inhibitors)

for 30 min at 4°C with rotation. A BCA kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure the proteins after they had

been isolated using RIPA (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The

total protein (10 µg per lane) was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and

transferred to a PVDF membrane (MilliporeSigma). The membranes were

blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Amresco, LLC; cat. no. GRM1254-500G)

in TBST (0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated

overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies purchased from Abcam

against RNF123 (cat. no. ab221877; 1:1,000), H3 (cat. no. ab1791;

1:10,000), H4 (cat. no. ab31830; 1:5,000), H3K18ac (cat. no.

ab40888; 1:500), H4K8ac (cat. no. ab45166; 1:500), H3K27ac (cat.

no. ab4729; 1:1,000), KAT2B (cat. no. ab96510; 1:1,000), E-cadherin

(cat. no. ab227639; 1:2,000), Vimentin (cat. no. ab92547; 1:1,000)

and GAPDH (cat. no. ab9485; 1:5,000). The membranes were then

incubated with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit

secondary antibody (cat. no. ab7090; Abcam; 1:5,000) and anti-mouse

secondary antibody (cat. no. ab97023; Abcam; 1:5,000) for 60 min at

room temperature. The protein bands were visualized using ECL (cat.

no. P10060; NCM Biotech; Suzhou Xinsaimei Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

and semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.80; National

Institutes of Health). For normalization, the ratio of the

grayscale value of the target protein to that of the loading

control was calculated for each sample. The relative expression

level of the target protein was determined using the following

formula: Relative expression (%)=(target protein grayscale

value/loading control grayscale value) ×100.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cells were cultured in 24-well plates

(1×104 cells/well) for 24 h. Cells were then treated for

3 h with 10 µl CCK-8 solution (Yeason Biotechnology). Subsequently,

the absorbance at 450 nm was measured.

5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine (EdU)

assay

Cells were seeded into confocal plates

(1×106 cells/well) and incubated with 50 µM EdU buffer

for 2 h (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.). Cells were then fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and

permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at room

temperature. After adding EdU solution to the culture, the nuclei

were stained with Hoechst for 15 min at room temperature in the

dark. The samples were imaged using an Olympus fluorescence

microscope. EdU-positive cells were quantified using ImageJ

software.

Transwell assay

DMEM (cat. no. 11965092; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) containing 1×104 cells (500 µl) was added to the

upper chamber of a Transwell plate precoated with Matrigel (1:8

ratio; Corning, Inc.) at 37°C for 4 h for invasion assays.

Migration assays were performed using uncoated Transwell plates.

Complete DMEM (1,000 µl) was added to the lower chamber. Cells in

the upper chamber were removed after incubation at 37°C for 12 h,

while cells in the lower chamber were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and stained with

0.5% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. An Olympus

light microscope was used to image the cells. DMEM was selected

instead of RPMI 1640 as A549 and H1975 cells exhibited optimal

growth and migration in DMEM based on preliminary optimization.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

Using a pre-prepared confluent 10 cm dish

(~107 cells), the cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde

for 5 min at room temperature to induce DNA-protein cross-linking.

Cell lysate was then sonicated on ice for 15 min (30 sec on/30 sec

off cycles at 20% amplitude) to produce chromatin fragments and

incubated overnight with anti-H3K18ac (cat. no. ab40888; 1:500;

Abcam), anti-H4K8ac (cat. no. ab45166; 1:200; Abcam), anti-KAT2B

(cat. no. ab96510; 1:100; Abcam) or anti-IgG (cat. no. ab172730;

1:100; Abcam) antibodies. Pierce protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.; 30 µl bead slurry per reaction) were

incubated with the chromatin-antibody mixture for 4 h at 4°C with

rotation. Beads were collected on a magnetic rack and washed

sequentially at 4°C with 1 ml each of low-salt buffer (20 mM

Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100),

high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1%

Triton X-100), LiCl buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 1

mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate) and TE buffer (10 mM

Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). Each wash step included rotation for 5

min at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 1 min at

4°C. The chromatin-antibody complexes were eluted by incubating the

beads in 200 µl elution buffer (1% SDS, 100 mM NaHCO3)

at 65°C for 30 min with frequent vortexing. DNA was purified using

the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (cat. no. 28106; Qiagen

Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions and

analyzed using RT-qPCR with primers specific for the RNF123

promoter region (forward: 5′-GCATCTGTGTGGTCCTGACA-3′; and reverse:

5′-TCTTGAGCACAGCTGGGAAG-3′).

Data retrieval and statistical

analysis

The StarBase database (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) was used to retrieve and

analyze the expression levels of RNF123 and KAT2B in LUAD and LUSC.

The method used was as follows: i) Select the pan-cancer option,

then click on the Gene Differential Expression option and finally

search for the target gene in the search box; ii) select the chart

type, box plot; iii) select the data scale method, log2(FPKM +

0.01); and iv) select the cancer name on the pan-cancer table to

browse the corresponding differential profile. It should be noted

that the StarBase database does not provide patient demographic

data, which is a limitation of the present study. All data was

obtained from three separate trials. The enrichment of histone

acetylation marks on H3K18ac, H4K8ac and H3K27ac within gene

promoter regions was analyzed using the UCSC Genome Browser

(https://genome.ucsc.edu/) and the human genome

assembly GRCh38/hg38 (GSE16256) (16). The promoter region was defined as 2

kb upstream to 500 bp downstream of the transcription start site

for each gene of interest.

The statistical data, which were reported as the

mean ± SD, were examined using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0;

Dotmatics). The differences between two groups were investigated

using paired and unpaired Student's t-tests. One-way ANOVA was

performed to compare differences between >2 groups, followed by

Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test to determine which

specific group means were significantly different from each other.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

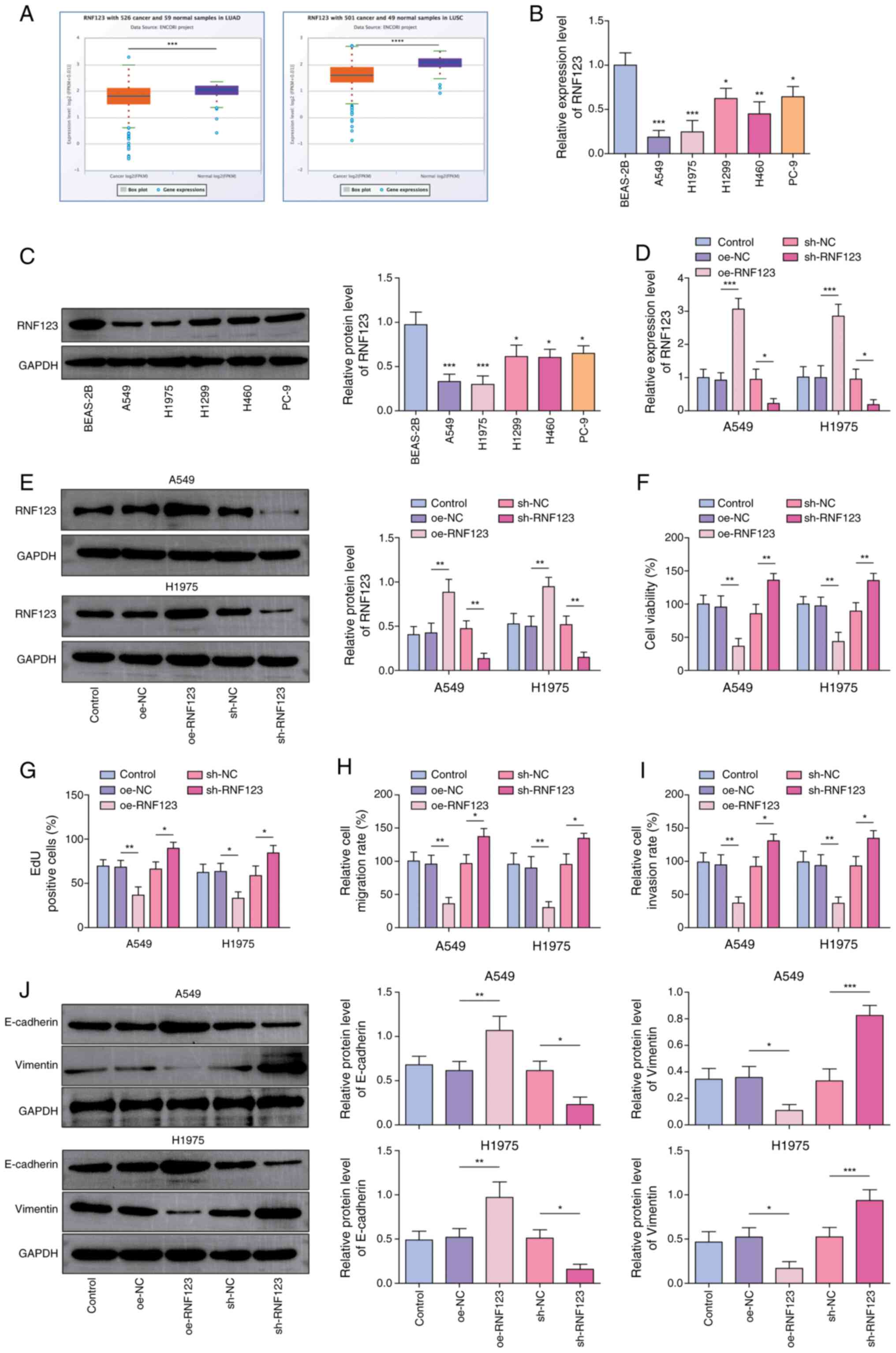

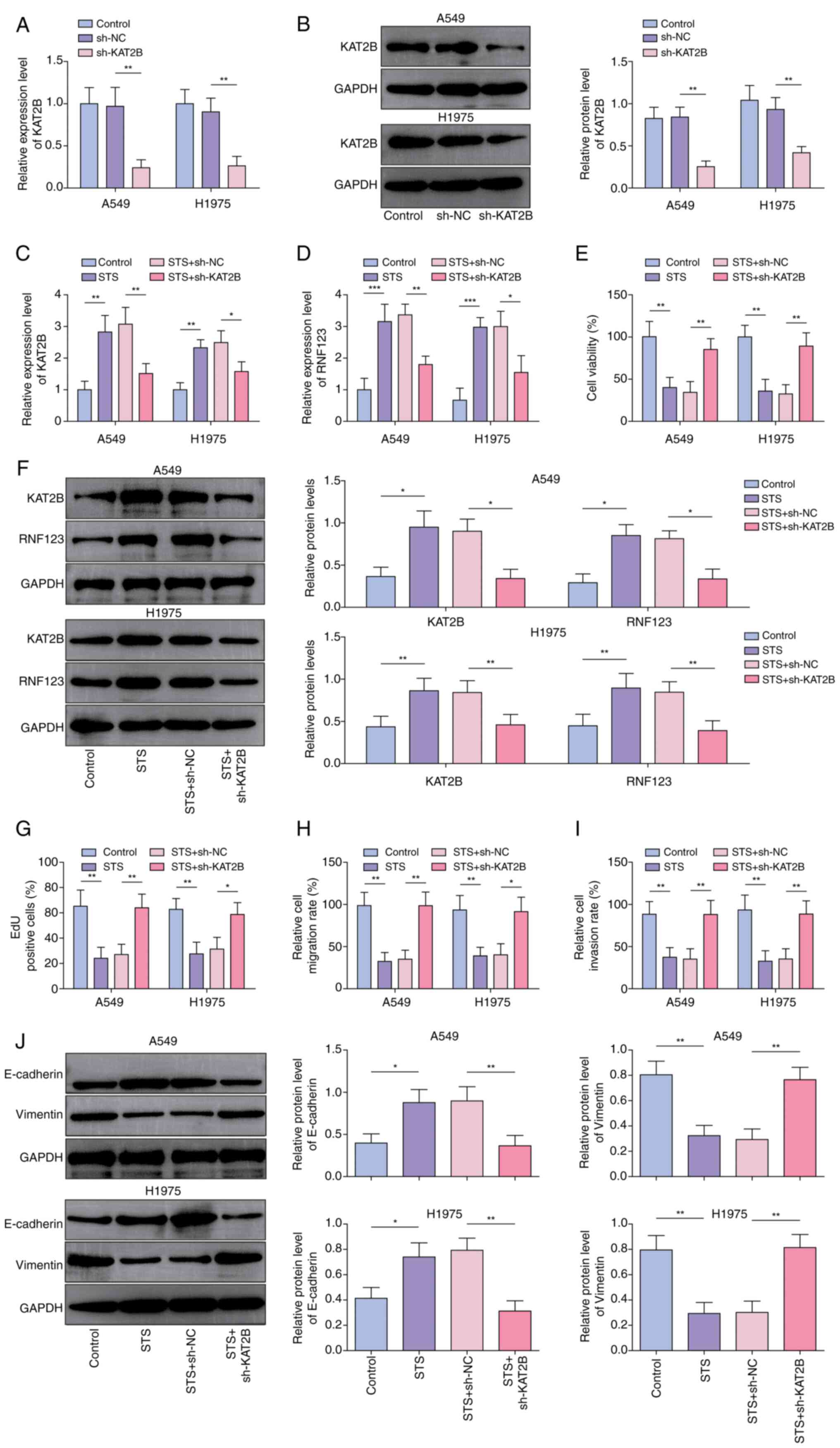

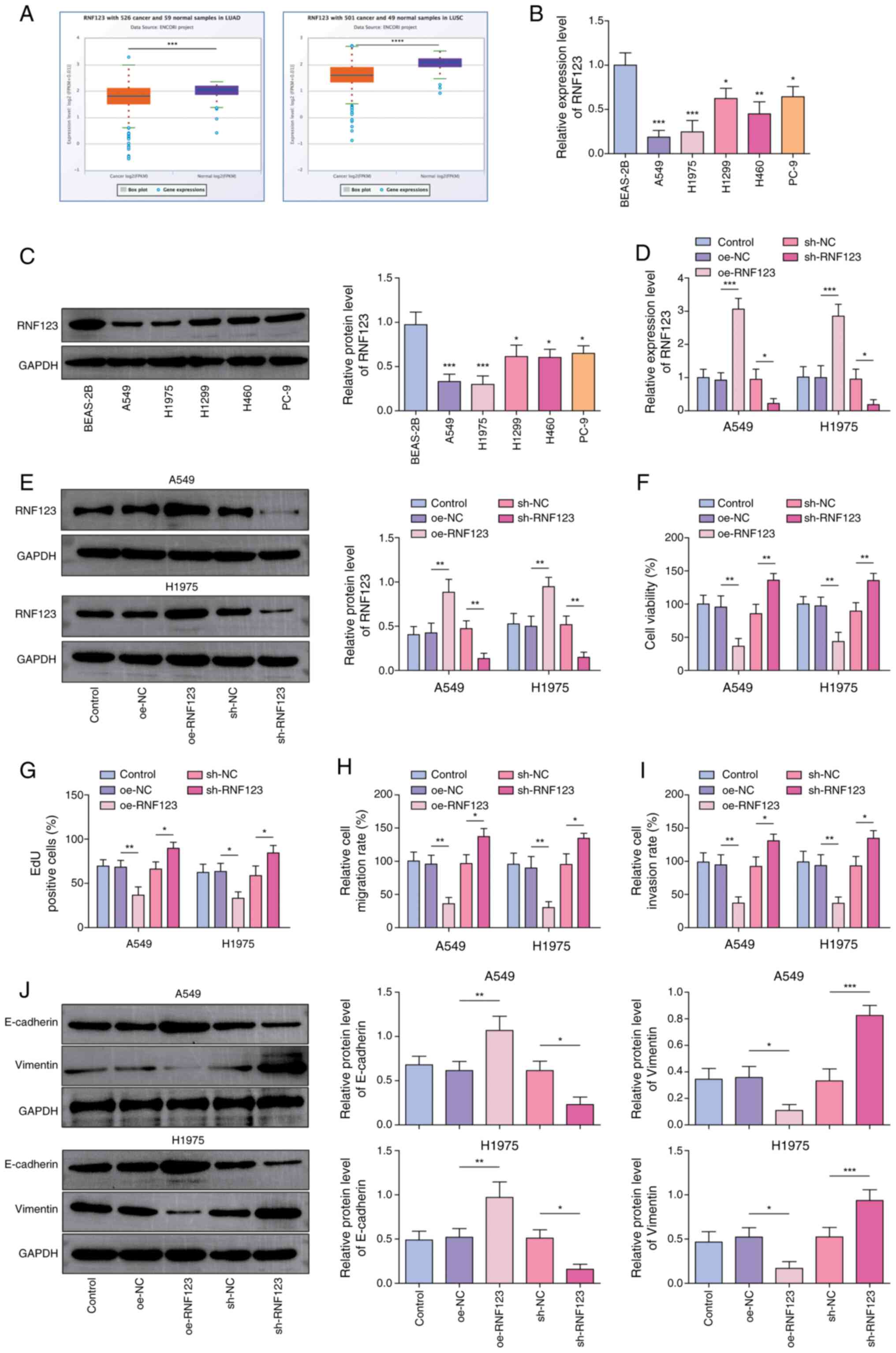

RNF123 is a critical mediator of NSCLC

cell proliferation

The starBase database projected that RNF123 was

weakly expressed in LUAD and LUSC samples (Fig. 1A). Concurrently, it was observed

that RNF123 was significantly downregulated in lung cancer cells

compared with BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 1B

and C). Among the lung cancer cell lines, the RNF123 expression

levels exhibited the most pronounced changes in A549 and H1975

cells, hence these two cell lines were chosen for subsequent

investigation. To elucidate the role of RNF123 in controlling lung

cancer cell malignant behaviors, RNF123 overexpression and

knockdown were induced in A549 and H1975 cells. oe-RNF123 and

sh-RNF123 transfection significantly elevated and reduced RNF123

expression in both A549 and H1975 cells, respectively (Fig. 1D and E). Functional experiments

showed that RNF123 overexpression markedly inhibited A549 and H1975

cell viability (Fig. 1F),

proliferation (Figs. 1G and

S1A), migration (Figs. 1H and S1B) and invasion (Figs. 1I and S1C), while RNF123 knockdown had the

inverse effects. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a

process linked to cancer metastasis (17). During EMT, the reciprocal loss of

E-cadherin (an adhesion molecule maintaining epithelial integrity

via cell-cell junctions) and gain of Vimentin (a mesenchymal

cytoskeletal protein promoting motility and invasive morphology)

creates an inverse profile that serves as a hallmark of EMT and a

key biomarker for tumor metastasis (18). RNF123 upregulation decreased

Vimentin expression levels and elevated E-cadherin expression

levels in lung cancer cells, while RNF123 downregulation had the

opposite effect (Fig. 1J).

Collectively, RNF123 upregulation suppressed lung cancer cell

malignant behaviors.

| Figure 1.RNF123 is a critical mediator of

non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation, migration and

invasion. (A) RNF123 expression in LUAD and LUSC was predicted

using the starBase database. The mRNA and protein expression levels

of RNF123 in lung cancer cells (A549, H1975, H1299, H460 and PC-9

cells) and the normal human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B

cells) were detected by (B) RT-qPCR and (C) western blotting,

respectively. A549 and H1975 cells were transfected with

oe-RNF123/sh-RNF123 or oe-NC/sh-NC. The mRNA and protein expression

levels of RNF123 in cells were detected by (D) RT-qPCR and (E)

western blotting, respectively. (F) Cell viability was examined

using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. (G) The EdU assay was

performed to determine cell proliferation. Cell (H) migration and

(I) invasion were assessed using the Transwell assay in cells with

RNF123 knockdown (sh-RNF123) or overexpression (oe-RNF123). Results

are expressed as percentages relative to the control group (set as

100%). (J) E-cadherin and Vimentin protein expression levels in

cells were measured by western blotting. Data are expressed as mean

± SD (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. RNF123, RING finger protein 123; LUAD, lung

adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; oe, overexpression; sh,

short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control; EdU,

5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine. |

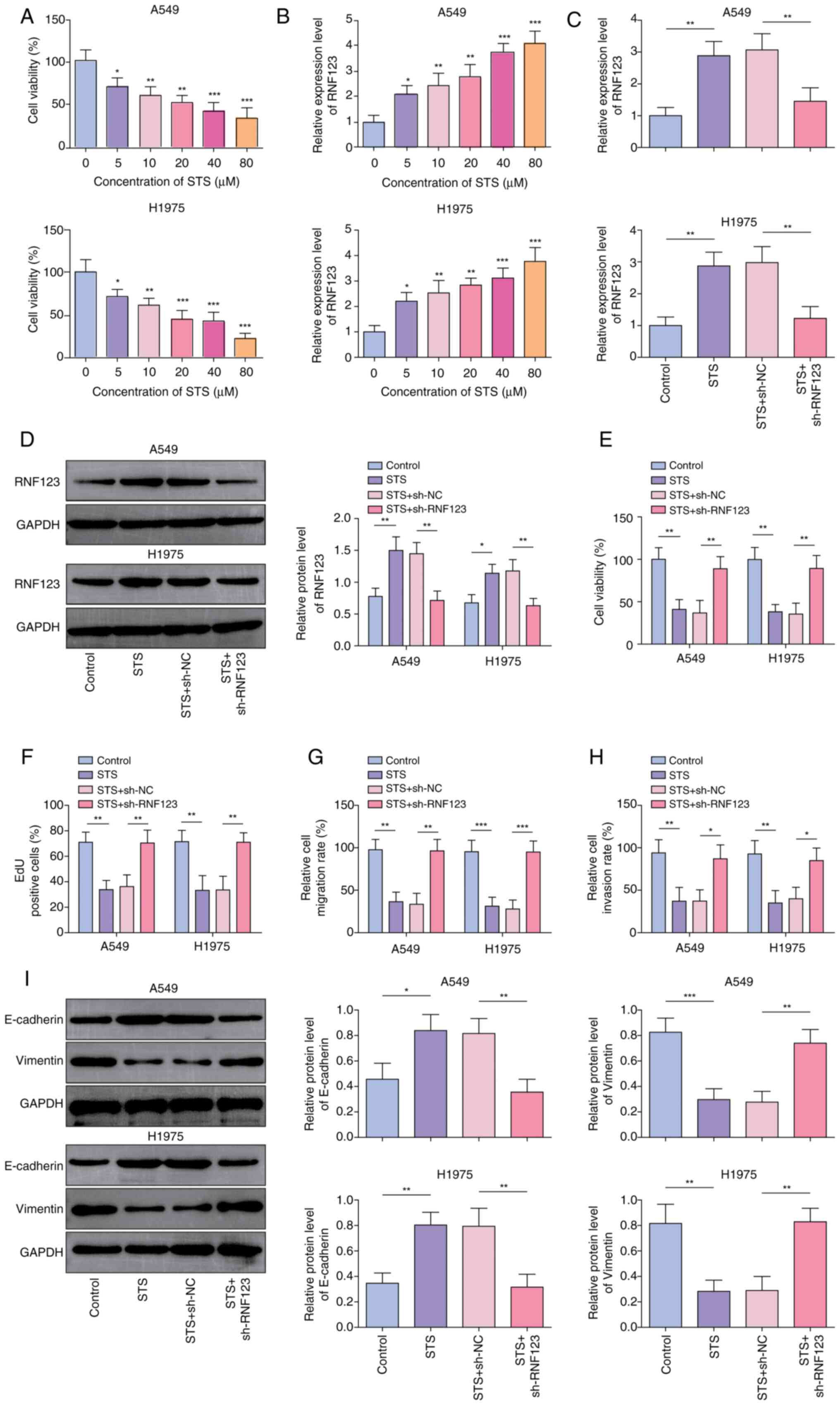

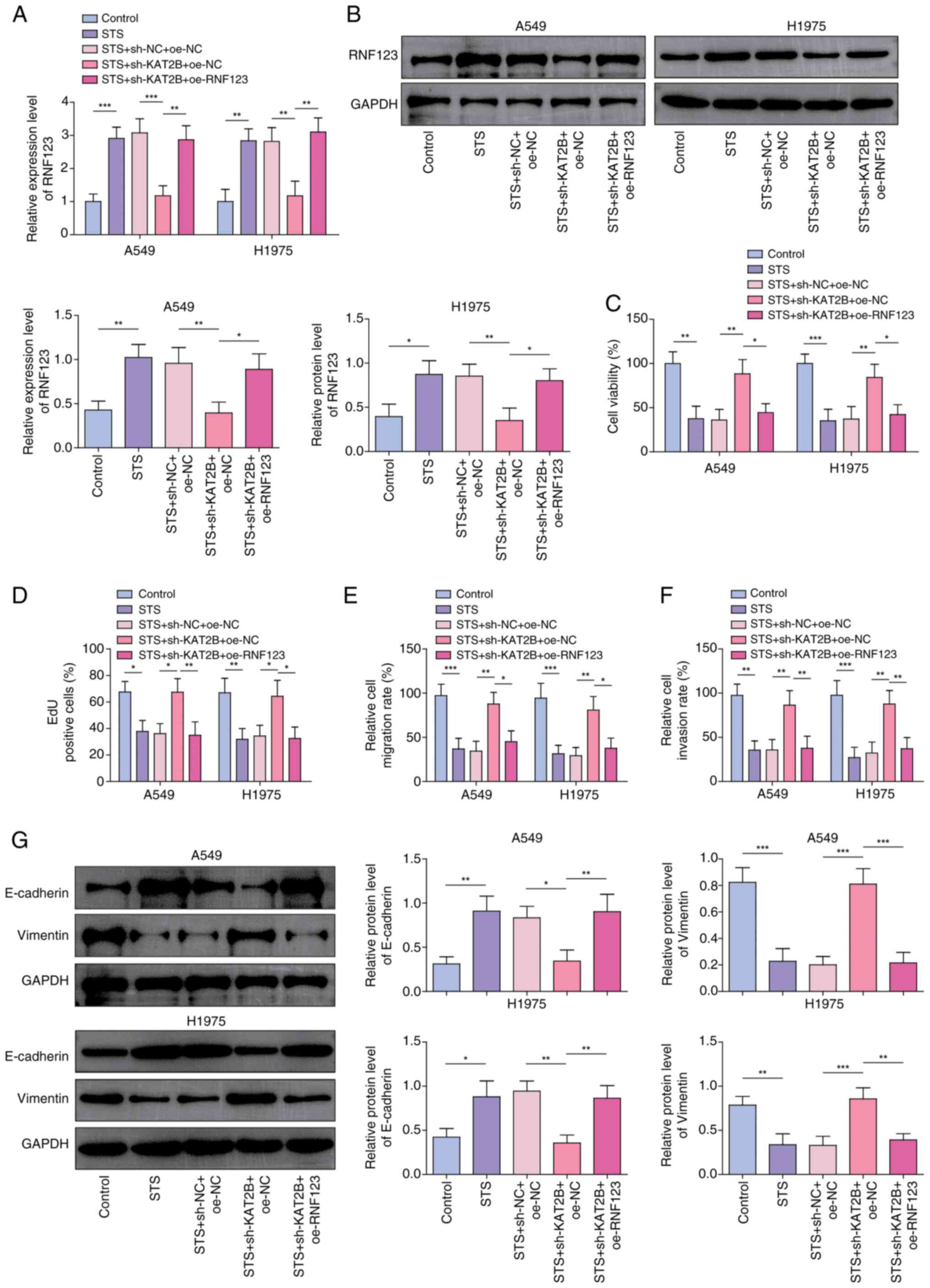

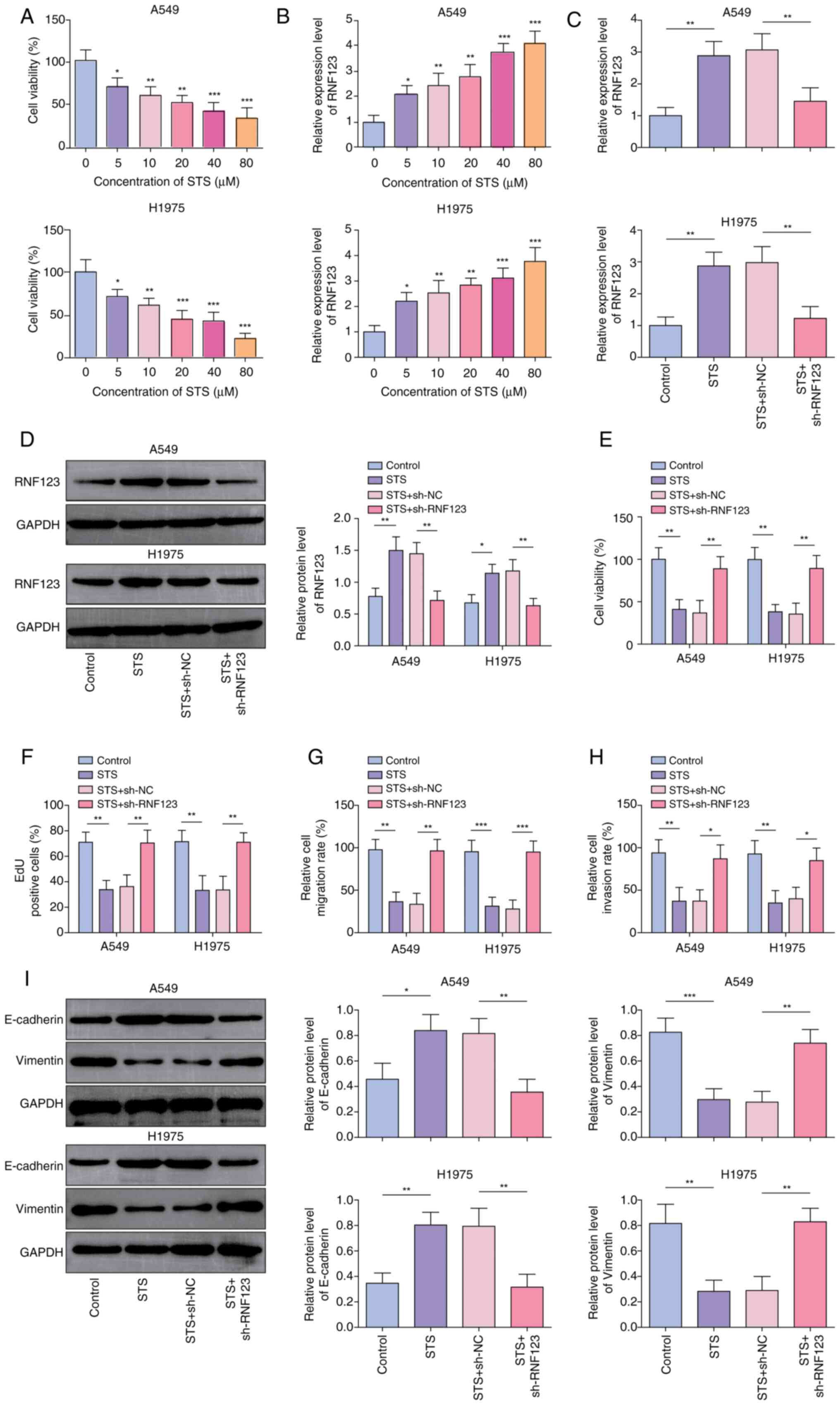

RNF123 knockdown reverses the

inhibitory effects of STS on NSCLC cells

STS, a water-soluble derivative of TSIIA with a

relative molecular mass of 396.39, dose-dependently reduced lung

cancer cell viability, as determined using the CCK-8 assay

(Fig. 2A). Additionally, STS

elevated RNF123 expression levels in lung cancer cells in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). A

concentration 40 µM STS was chosen for use in subsequent

experiments due to its ability to reduce cell viability by ~50%.

STS significantly upregulated RNF123 expression levels in A549 and

H1975 cells; however, this effect was abrogated by sh-RNF123

transfection (Fig. 2C and D). In

addition, STS treatment significantly reduced A549 and H1975 cell

viability (Fig. 2E), proliferation

(Figs. 2F and S2A), migration (Figs. 2G and S2B) and invasion (Figs. 2H and S2C), while RNF123 knockdown reversed

these effects. Moreover, STS reduced Vimentin protein expression

levels and elevated E-cadherin protein expression levels in A549

and H1975 cells. These changes in protein expression levels were

reversed by RNF123 knockdown (Fig.

2I). Collectively, STS inhibited lung cancer cell malignant

phenotypes potentially by upregulating RNF123 expression.

| Figure 2.RNF123 knockdown reverses the

inhibitory effects of STS on non-small cell lung cancer cells. A549

and H1975 cells were treated with 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 µM STS for

24 h. (A) CCK-8 assay was employed to detect cell viability. (B)

RT-qPCR was conducted to examined RNF123 mRNA expression level in

cells. A549 and H1975 cells were treated with 40 µM STS for 24 h

combined with sh-NC or sh-RNF123 transfection. The mRNA and protein

expression levels of RNF123 in cells were detected by (C) RT-qPCR

and (D) western blotting, respectively. (E) Cell viability was

measured by CCK-8 assay. (F) EdU assay was performed to determine

cell proliferation. Cell (G) migration and (H) invasion were

detected by Transwell assay. Results are expressed as percentages

relative to the control group (set as 100%). (I) Western blotting

was performed to examine E-cadherin and Vimentin protein expression

levels in cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. RNF123, RING finger protein 123; STS,

sodium tanshinone IIA sulfate; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; sh, short hairpin RNA; NC,

negative control; EdU, 5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine. |

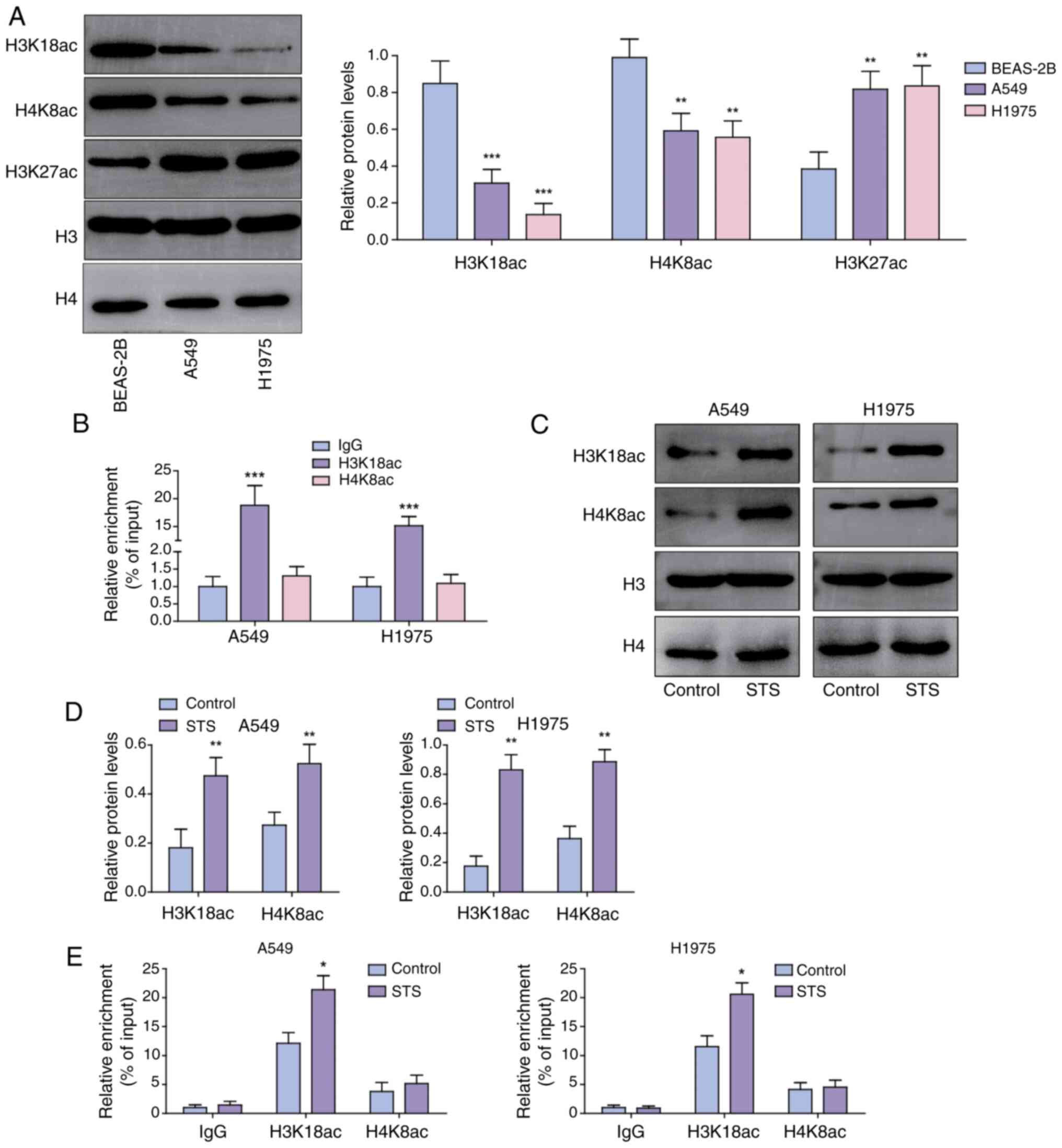

STS promotes H3K18ac modification of

RNF123 in NSCLC cells

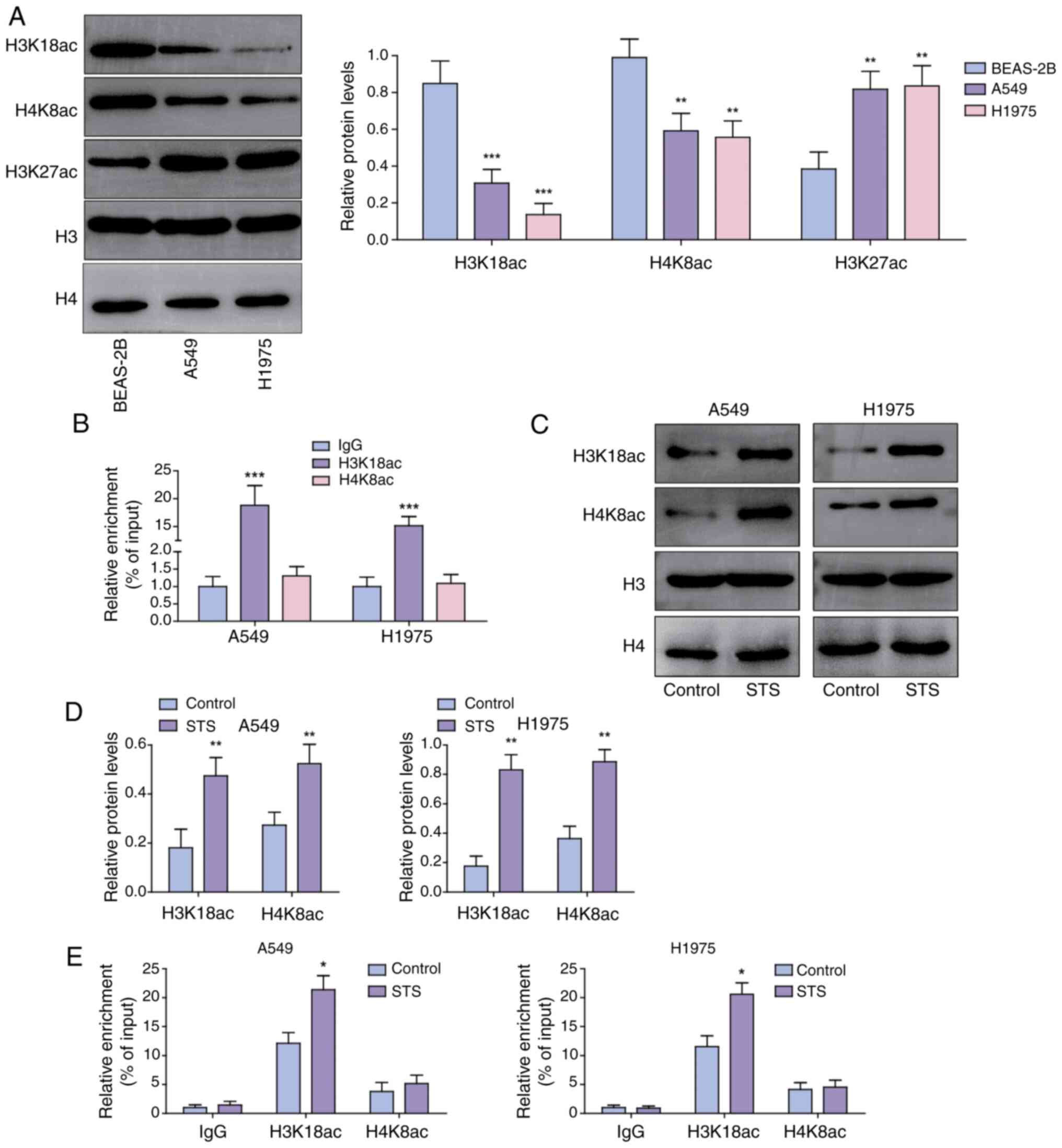

Histone acetylation alterations are linked to cancer

progression (9). H3K18ac and H4K8ac

expression levels were significantly reduced and H3K27ac expression

levels were elevated in A549 and H1975 cells compared with BEAS-2B

cells (Fig. 3A). As predicted by

the UCSC database, H3K18ac, H4K8ac and H3K27ac were enriched in the

RNF123 promoter region (Fig. S3).

Given the pivotal role of histone acetylation in promoting gene

transcription and the synchronous downregulation of RNF123, H3K18ac

and H4K8ac expression levels in lung cancer cells, it was

hypothesized that RNF123 may be modified by H3K18ac and H4K8ac.

ChIP assay results demonstrated that H3K18ac was enriched in the

RNF123 promoter, whereas enrichment of H4K8ac was not detected

(Fig. 3B). Moreover, STS treatment

significantly elevated H3K18ac and H4K8ac expression levels in A549

and H1975 cells (Fig. 3C). As

confirmed by the ChIP assay results, STS promoted H3K18ac

enrichment in the RNF123 promoter region but did not facilitate

H4K8ac enrichment in the RNF123 promoter region (Fig. 3D). These results suggested that STS

may increase the transcriptional activity of RNF123 through

promoting H4K8ac enrichment in the RNF123 promoter.

| Figure 3.STS promotes H3K18ac modification of

chromatin at the RNF123 locus in non-small cell lung cancer cells.

(A) H3K18ac, H4K8ac and H3K27ac levels in A549, H1975 and BEAS-2B

cells were assessed using western blotting. (B) The enrichment of

H3K18ac and H4K8ac in the RNF123 promoter was analyzed by ChIP

assay. A549 and H1975 cells were treated with 40 µM STS for 24 h.

(C) H3K18ac and H4K8ac protein expression levels in cells were

examined using western blotting and (D) semi-quantified. Histone

acetylation signals were normalized to total histone H3 or H4

levels, respectively. (E) H3K18ac and H4K8ac enrichment in the

RNF123 promoter was analyzed by ChIP assay. Data are expressed as

mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. STS,

sodium tanshinone IIA sulfate; RNF123, RING finger protein 123;

H3K18ac, histone H3 lysine 18 acetylation; H4K8ac, histone H4

lysine 8 acetylation; H3K127ac, histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation;

ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation. |

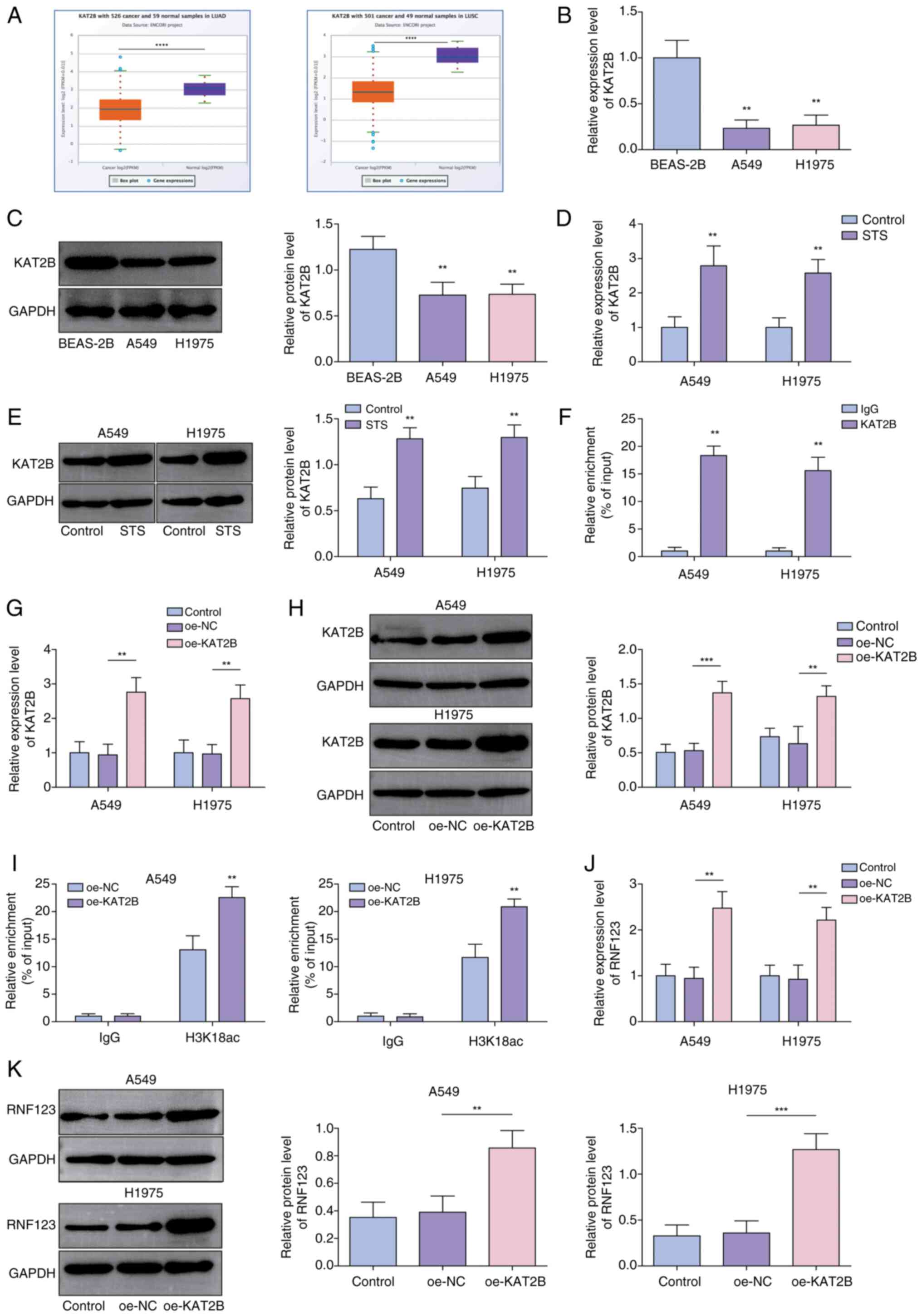

STS promotes the H3K18ac modification

and expression of RNF123 by upregulating the expression of

KAT2B

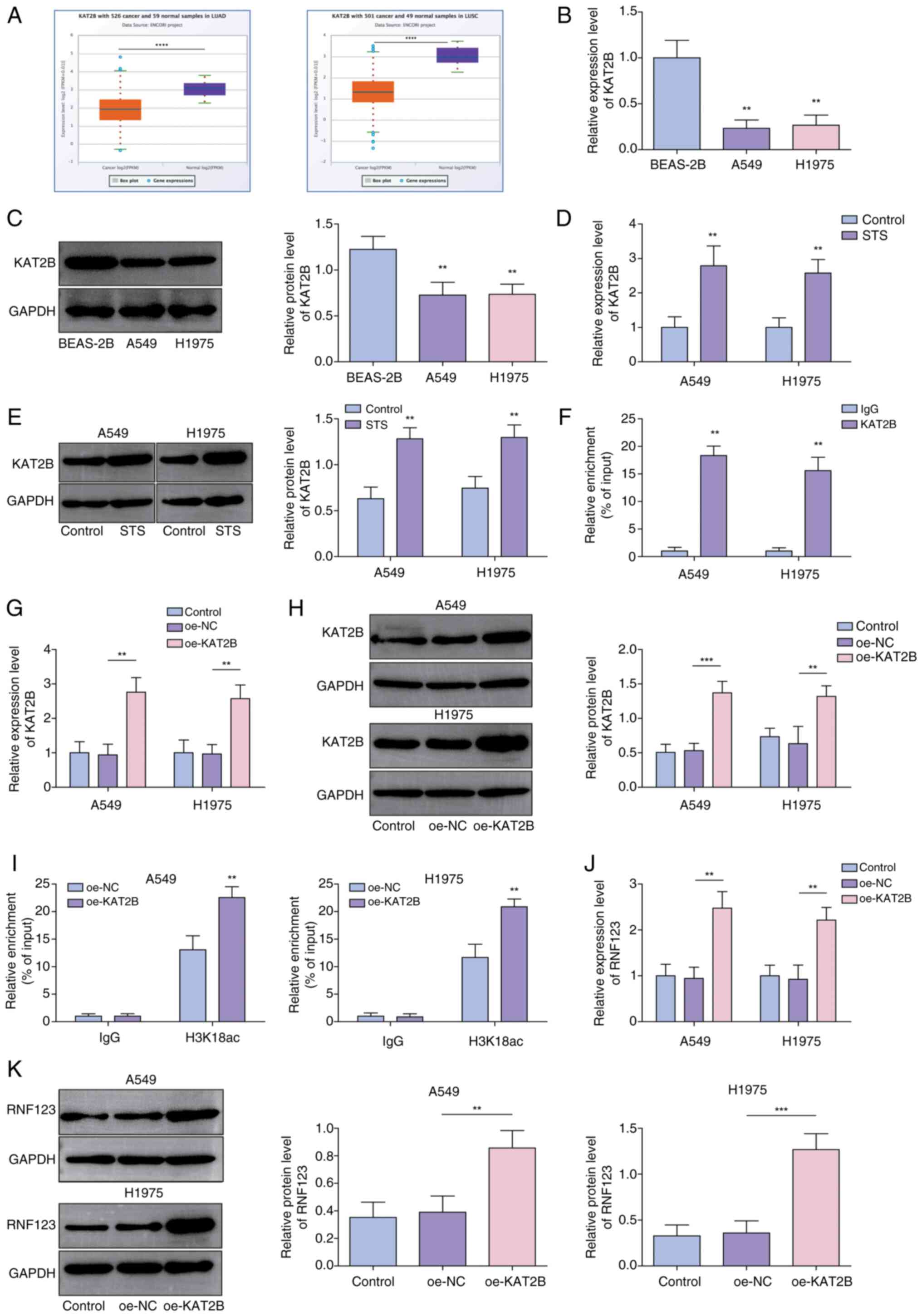

KAT2B, an essential HAT epigenetic factor, serves as

a biomarker for predicting prognosis in NSCLC (19,20).

Herein, it was demonstrated that KAT2B was expressed at low levels

in LUAD and LUSC using the starBase database (Fig. 4A). KAT2B expression levels were

lower in A549 and H1975 cells compared with BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 4B and C). Notably, KAT2B expression

in lung cancer cells was significantly increased by STS treatment

(Fig. 4D and E). Furthermore, it

was demonstrated that KAT2B was enriched in the RNF123 promoter

region (Fig. 4F). Next, A549 and

H1975 cells were transfected with oe-NC or oe-KAT2B, and the

subsequent RT-qPCR and western blotting results showed that

oe-KAT2B transfection significantly elevated the KAT2B expression

levels (Fig. 4G and H).

Additionally, KAT2B overexpression facilitated H3K18ac enrichment

in the RNF123 promoter region (Fig.

4I). Moreover, KAT2B overexpression significantly elevated

RNF123 expression levels in lung cancer cells (Fig. 4J and K). In conclusion, STS promoted

RNF123 expression in lung cancer cells potentially by increasing

the H3K18ac enrichment in the RNF123 promoter through upregulating

KAT2B.

| Figure 4.STS promotes the H3K18ac modification

and expression of RNF123 by upregulating the expression of KAT2B.

(A) KAT2B expression in LUAD and LUSC was predicted using the

starBase database. The mRNA and protein expression levels of KAT2B

in A549, H1975 and BEAS-2B cells were detected by (B) RT-qPCR and

(C) western blotting, respectively. The mRNA and protein expression

levels of KAT2B in A549 and H1975 cells after STS treatment were

detected by (D) RT-qPCR and (E) western blotting, respectively. (F)

The interaction between KAT2B and RNF123 promoter was analyzed by

ChIP assay. A549 and H1975 cells were transfected with oe-NC or

oe-KAT2B. The mRNA and protein expression levels of KAT2B in cells

were detected by (G) RT-qPCR and (H) western blotting,

respectively. (I) H3K18ac enrichment in the RNF123 promoter was

analyzed by ChIP assay. The mRNA and protein levels of RNF123 in

cells were detected by (J) RT-qPCR and (K) western blotting,

respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. STS, sodium tanshinone IIA sulfate;

RNF123, RING finger protein 123; H3K18ac, histone H3 lysine 18

acetylation; KAT2B, lysine acetyltransferase 2B; LUAD, lung

adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; ChIP, chromatin

immunoprecipitation; oe, overexpression; NC, negative control. |

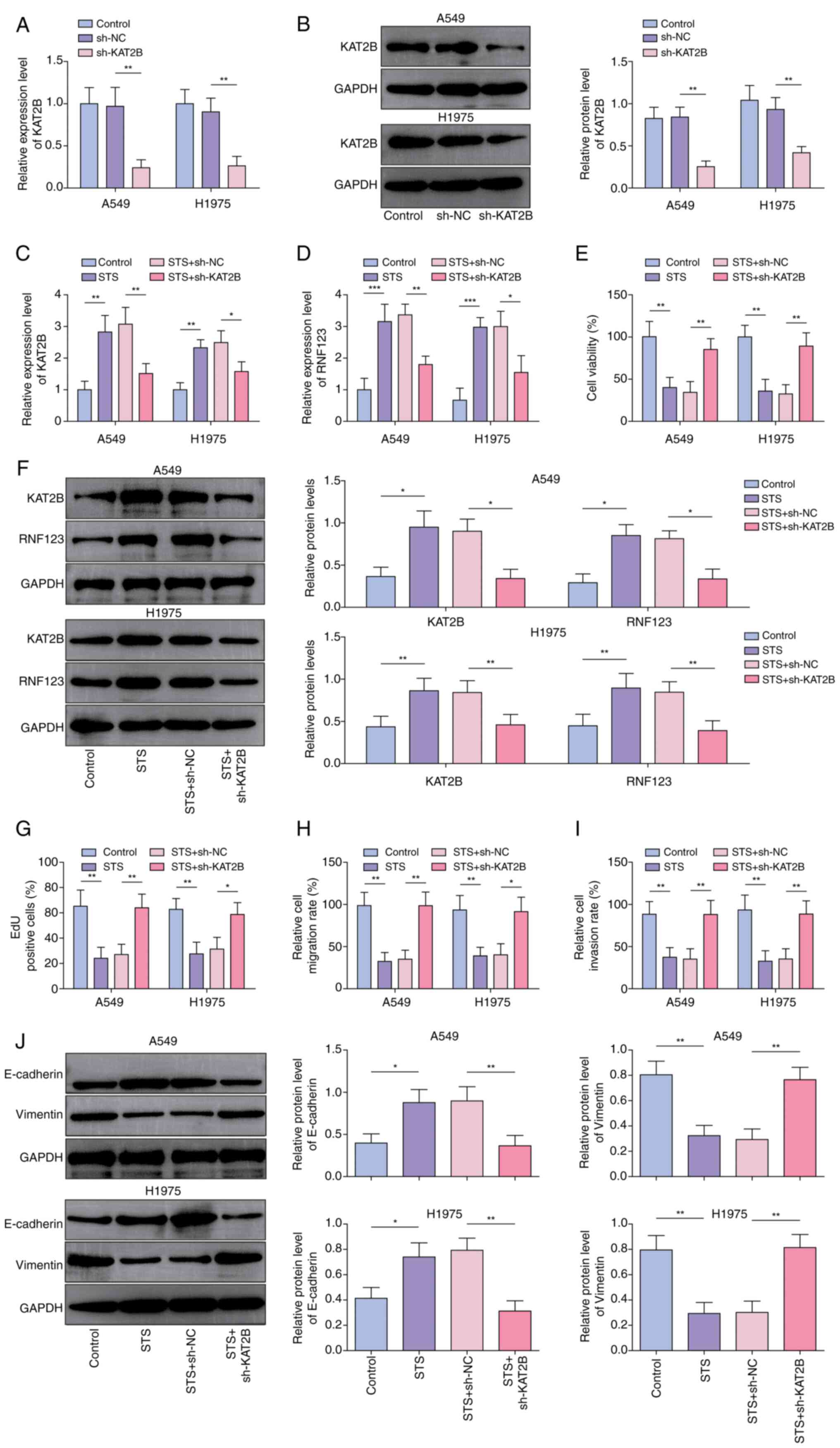

KAT2B knockdown reverses the

inhibitory effects of STS on the malignant phenotypes of NSCLC

cells

A549 and H1975 cells were subjected to STS treatment

combined with sh-KAT2B or sh-NC transfection to elucidate the role

of KAT2B in the STS-mediated anticancer effects. Initially, it was

demonstrated that sh-KAT2B transfection significantly downregulated

the KAT2B expression levels in A549 and H1975 cells (Fig. 5A and B). KAT2B expression levels in

lung cancer cells were also significantly increased by STS

administration and this upregulation was reversed by KAT2B

knockdown (Fig. 5C-E). Furthermore,

the knockdown of KAT2B counteracted the inhibitory effects of STS

on cell viability (Fig. 5F),

proliferation (Figs. 5G and

S4A), migration (Figs. 5H and S4B) and invasion (Figs. 5I and S4C). It was also demonstrated that the

promoting effect of STS on E-cadherin expression levels and the

inhibitory effect on Vimentin expression levels in lung cancer

cells were abolished following KAT2B knockdown (Fig. 5J). In summary, KAT2B knockdown

neutralized the inhibitory effects of STS on the malignant

phenotypes of lung cancer cells.

| Figure 5.KAT2B knockdown reverses the

inhibitory effects of STS on the malignant phenotypes of non-small

cell lung cancer cells. KAT2B knockdown was induced in STS-treated

A549 and H1975 cells. The mRNA and protein expression levels of

KAT2B in A549 and H1975 cells after sh-NC or sh-KAT2B transfection

were detected by (A) RT-qPCR and (B) western blotting,

respectively. A549 and H1975 cells were treated with 40 µM STS for

24 h combined with sh-NC or sh-KAT2B transfection. The mRNA

expression levels of (C) KAT2B and (D) RNF123 in cells were

detected by RT-qPCR. (E) Cell viability was measured by Cell

Counting Kit-8 assay. (F) The protein expression levels of RNF123

and KAT2B in cells were detected by western blotting. (G) EdU assay

was performed to determine cell proliferation. Cell (H) migration

and (I) invasion were detected by Transwell assay. Results are

expressed as percentages relative to the control group (set as

100%). (J) E-cadherin and Vimentin protein levels in cells were

examined by western blotting. Data are expressed as mean ± SD

(n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. KAT2B, lysine

acetyltransferase 2B; STS, sodium tanshinone IIA sulfate; sh, short

hairpin RNA; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NC,

negative control; RNF123, RING finger protein 123; EdU,

5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine. |

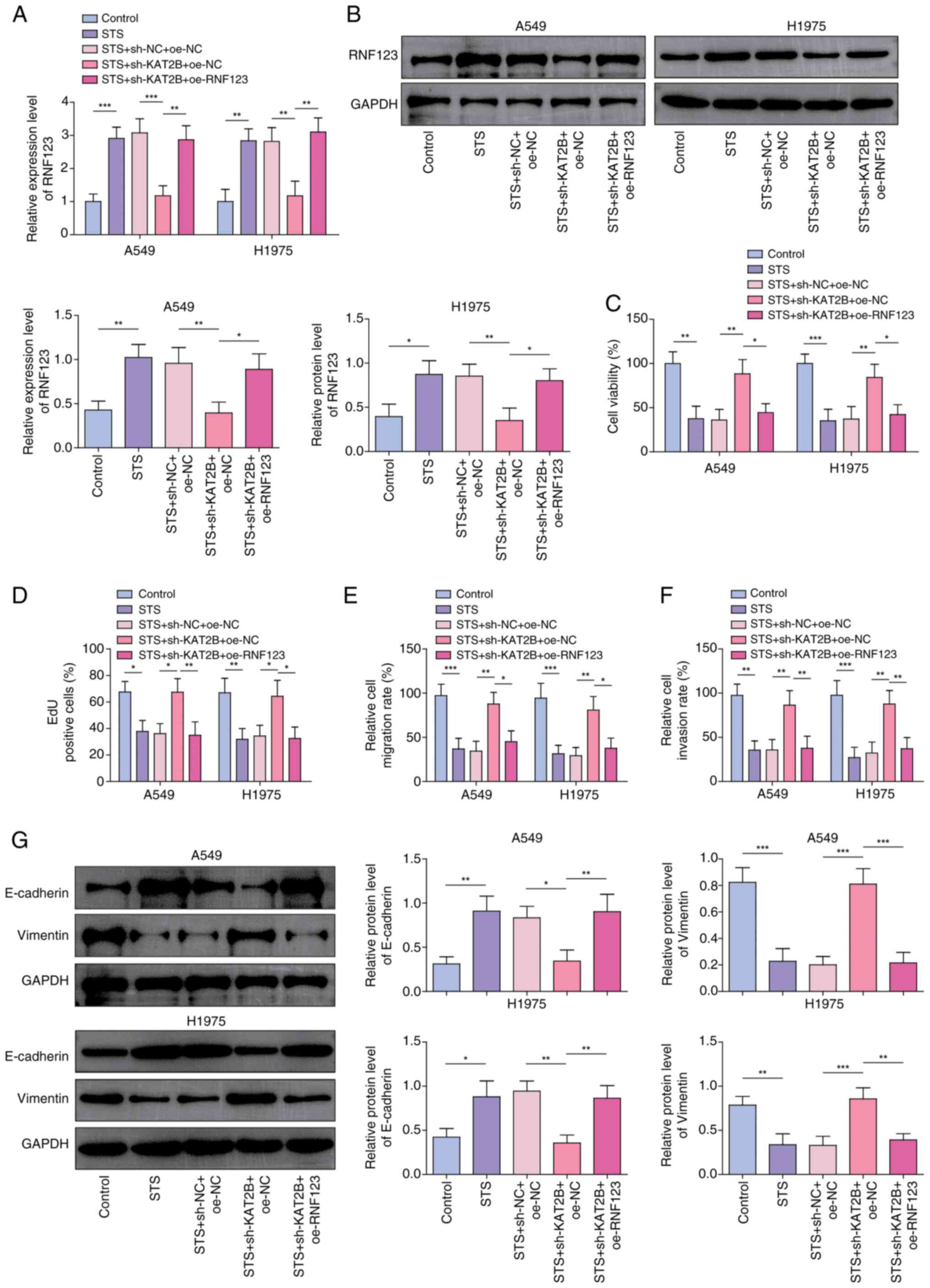

RNF123 overexpression reverses the

effects of KAT2B knockdown on the STS-treated NSCLC cell malignant

phenotypes

To investigate the interaction between KAT2B and

RNF123 in the STS-mediated anticancer effects, A549 and H1975 cells

treated with STS were co-transfected with RNF123 overexpression and

KAT2B knockdown constructs. Co-transfection with oe-RNF123 rescued

the suppressive effect of KAT2B knockdown on RNF123 expression

levels in STS-treated A549 and H1975 cells (Fig. 6A and B). Additionally, RNF123

overexpression mitigated the sh-KAT2B-induced enhancement of the

viability (Fig. 6C), proliferation

(Figs. 6D and S5A), migration (Figs. 6E and S5B) and invasion (Figs. 6F and S5C) of STS-treated A549 and H1975 cells.

Moreover, KAT2B knockdown reduced E-cadherin protein expression

levels and elevated Vimentin expression levels in STS-treated A549

and H1975 cells, whereas RNF123 upregulation restored these effects

(Fig. 6G). In conclusion, STS

inhibited the lung cancer cell malignant phenotypes via modulating

the KAT2B/RNF123 axis.

| Figure 6.RNF123 overexpression reverses the

effects of KAT2B knockdown on the malignant phenotypes of non-small

cell lung cancer cells treated with STS. Both RNF123 overexpression

and KAT2B knockdown were induced in STS-treated A549 and H1975

cells. The mRNA and protein expression levels of RNF123 in cells

were detected by (A) RT-qPCR and (B) western blotting,

respectively. (C) Cell viability was examined using Cell Counting

Kit-8 assay. (D) EdU assay was performed to determine cell

proliferation. Cell (E) migration and (F) invasion were assessed

using Transwell assay. Results are expressed as percentages

relative to the control group (set as 100%). (G) E-cadherin and

Vimentin protein levels in cells were measured by western blotting.

Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P< 0.001. STS, sodium tanshinone IIA sulfate; RNF123, RING

finger protein 123; KAT2B, lysine acetyltransferase 2B; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NC, negative control; sh,

short hairpin RNA; oe, overexpression; EdU,

5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine. |

Discussion

Lung cancer is a major challenge to global health.

According to global cancer statistics, there were 2.481 million new

cases of lung cancer in 2022, accounting for 12.4% of all new

cancer cases globally (1).

Historically, the prognosis for patients with lung cancer has been

poor (9). Over the past decade,

significant advancements have been made in the field of lung cancer

treatment, particularly in the areas of molecular targeted therapy

and immunotherapy. For instance, targeted therapy against ROS

proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase (ROS1) gene fusions have

provided a new option for precision treatment for patients with

advanced NSCLC. ROS1-positive patients tend to be younger (median

onset ~50 years) and are frequently non-smoking women with

adenocarcinoma (3). However,

despite these advancements, lung cancer remains the leading cause

of cancer-related mortality (21).

As a result, the discovery of novel therapeutic options to improve

the survival of patients with lung cancer is required. The findings

of the present study indicate that TSIIA suppresses lung cancer

cell malignant phenotypes in vitro by increasing RNF123

expression levels through promoting KAT2B-mediated H3K18ac

modification.

TSIIA, the predominant diterpenoid quinone derived

from Salvia miltiorrhiza, has been utilized in China for

>2,000 years to treat cardiovascular disorders (22). In the past decade, research interest

in the protective effects of TSIIA on cancer has increased. TSIIA

suppresses EMT and migration in colorectal and gastric cancer cells

(23,24), inhibits NSCLC proliferation through

VEGF/VEGFR2 downregulation (25)

and triggers SCLC apoptosis by upregulating Bax/Bcl-2 and reducing

mitochondrial membrane potential (26). It has been previously shown that STS

has potential in anticancer research as STS can effectively inhibit

the cell viability and colony formation of NSCLC cells (6,7).

Furthermore, STS has been reported to exert antitumor effects in

the treatment of colorectal cancer (5). By targeting specific proteins and

signaling pathways, STS may inhibit tumor proliferation and

metastasis (25,27). However, the role of STS or TSIIA in

controlling lung cancer migration, invasion and EMT is not well

understood. The findings of the present study showed that STS

treatment significantly inhibited lung cancer cell viability,

proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT. TSIIA, a drug with

multiple pharmacological effects, has a high efficiency, low

toxicity and a natural source compared with chemotherapy drugs, and

has significant potential clinical value (27). These findings provide a further

foundation for TSIIA as a potential anti-lung cancer drug.

EMT is a critical process by which cancer cells

acquire invasive and metastatic capabilities (17,18).

In the present study, it was observed that treatment with STS

significantly reduced the expression of the EMT marker, Vimentin,

and increased the expression of E-cadherin in NSCLC cells. This

suggests that STS may inhibit the invasiveness and metastatic

potential of NSCLC cells by suppressing the EMT process. In recent

years, EMT has been increasingly recognized not only as a

biological process but also as a potential ‘ecological process’.

According to the nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology theory proposed

by Luo (28), cancer can be viewed

as a multidimensional spatiotemporal ‘unity of ecology and

evolution’ pathological ecosystem. Within this ecosystem, cancer

cells interact dynamically with the tumor microenvironment and

these interactions not only influence the biological behavior of

cancer cells but may also shape tumor heterogeneity and

invasiveness through ecological selection and evolutionary

processes. During EMT, cancer cells exhibit mesenchymal

characteristics, such as increased migratory and invasive

abilities, which enable them to better adapt and survive in the

competitive and resource-limited tumor microenvironment. This

adaptive change can be seen as an ecological strategy that helps

cancer cells gain a survival advantage (28). Moreover, EMT-associated cancer cells

may interact dynamically with surrounding stromal cells (such as

cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells) through the

secretion of cytokines and exosomes, thereby further promoting

tumor progression (17,28).

Ubiquitin E3 ligases serve a key role in normal

human cells by regulating protein ubiquitination and degradation,

which is a necessary metabolic activity for life (29). The E3-ligase, RNF123, has been

reported to act as a tumor suppressor (13). Iida et al (30) demonstrated that RNF123 reduces

melanoma proliferation by processing NF-κB1 p105 into p50.

Furthermore, RNF123 is downregulated in aggressive glioblastoma and

its downregulation is associated with a poor prognosis (14). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the potential mechanism of action of RNF123 in lung

cancer has not been previously reported. The results of the present

study showed that RNF123 was expressed at low levels in lung cancer

cells and its overexpression inhibited the lung cancer cell

malignant phenotypes. Notably, it was also demonstrated that STS

increased the RNF123 expression levels in lung cancer cells and

RNF123 knockdown abolished the STS-induced inhibition of lung

cancer cell malignant phenotypes. Collectively, the results

suggested that STS inhibited lung cancer cell malignant phenotypes

by increasing RNF123 expression levels.

Histone acetylation is an important component of

transcriptional regulation, which depends on the balance of HAT and

HDAC activities (31). The

dysregulation of histone acetylation modifications promotes the

development of human malignant tumors (9). The findings of the present study

demonstrated that the H3K18ac and H4K8ac expression levels were

significantly reduced and the H3K27ac expression levels were

elevated in lung cancer cells. Moreover, H3K18ac and H4K8ac were

enriched in the RNF123 promoter. As previously reported, TSIIA

prevents cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury by regulating H3K18ac

and H4K8ac (12). In the present

study, STS increased the H3K18ac and H4K8ac expression levels in

lung cancer cells. Additionally, STS facilitated H3K18ac enrichment

in the RNF123 promoter. Collectively, the results of the present

study indicated that STS increased RNF123 expression levels in lung

cancer cells by promoting H3K18ac enrichment in the RNF123

promoter. KAT2B is a HAT that acetylates specific lysine residues

in histones and therefore primarily serves a role in regulating

chromatin remodeling, which is a key regulatory factor in signal

transduction during the occurrence of numerous diseases, including

cancer (32). KAT2B is an immune

infiltration-associated biomarker that predicts prognosis in

patients with NSCLC (20). The

findings of the present study showed that KAT2B was expressed at

low levels in lung cancer and STS increased KAT2B expression levels

in lung cancer cells. Notably, KAT2B increased RNF123 expression

levels in lung cancer cells by increasing the H3K18ac modification

in chromatin at the RNF123 locus. Furthermore, KAT2B knockdown

reversed the STS-induced inhibition of lung cancer cell malignant

phenotypes. Moreover, RNF123 upregulation abrogated the effects of

KAT2B knockdown on STS-treated lung cancer cell malignant

phenotypes. These findings may be significant for NSCLC treatment

as RNF123 was shown to suppress NSCLC proliferation and cellular

activity in A549 and H1975 NSCLC cell lines, potentially emerging

as a new target for treatment. STS inhibited NSCLC by upregulating

RNF123 expression through the KAT2B/H3K18ac pathway, presenting a

potential new treatment strategy. The low toxicity and lack of side

effects of STS make it a promising therapy, potentially improving

patient outcomes (27). The present

study may offer valuable insights and highlight the clinical

potential of this treatment against NSCLC.

However, there are a number of limitations of the

present study. At present, the hypothesis that Tanshinone IIA

targets RNF123 to inhibit NSCLC cell proliferation, migration and

invasion via KAT2B-mediated H3K18ac modification has only been

preliminarily verified at the cellular level and further

confirmation requires animal and clinical experiments.

Additionally, it was demonstrated that STS has effects on the

H3K18ac acetylation modification level; however, whether it also

affects other acetylation modification levels and whether it is

regulated by other acetylases requires further investigation.

Although the present study preliminarily revealed that STS inhibits

EMT by regulating RNF123 expression through KAT2B-mediated H3K18ac

modification, the detailed molecular mechanisms still need further

investigation. Specifically, whether TSIIA regulates other

epigenetic modifications or signaling pathways to influence the EMT

process should be explored. Moreover, the lack of patient

demographic data from StarBase is a limitation of the present

study, as it restricts the comprehensive understanding of the

clinical relevance of RNF123 and KAT2B in lung cancer. By

integrating the tumor ecology theory proposed by Luo (28), future studies could employ

multidimensional approaches (such as single-cell sequencing and

spatial transcriptomics) to comprehensively analyze the

spatiotemporal dynamics of the EMT process within the tumor

ecosystem. This will help us better understand the complexity of

tumors and provide new insights for developing precision medicine

strategies.

Taken together, the results of the present study

demonstrated that STS inhibited the lung cancer cell malignant

phenotypes by upregulating RNF123 through promoting KAT2B-mediated

H3K18ac modification of chromatin at the RNF123 locus. TSIIA may

have potential for the treatment of lung cancer in the future and

RNF123 may serve as an important target for the anticancer actions

of TSIIA.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Work was funded by the grant provided by the China Medicine

Education Association named ‘Construction of three-generation

sequencing database and data analysis platform’ (grant no.

2022KTZ017).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

The study and figures were designed by YH and KC. YH

and YZ conducted the experiments and interpreted the results with

JZ. YH, KC and JZ supervised the study. Bioinformatics analysis was

performed by YH. Funding was obtained by KC. YH wrote the

manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript. YH, YZ, JZ and KC confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

LUSC

|

lung squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

TSIIA

|

tanshinone IIA

|

|

STS

|

sodium TSIIA sulfate

|

|

HAT

|

histone acetyltransferase

|

|

HDAC

|

histone deacetylase

|

|

RNF123

|

RING finger protein 123

|

|

KAT2B

|

lysine acetyltransferase 2B

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

EdU

|

5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine

|

|

ChIP

|

chromatin immunoprecipitation

|

|

H3K18ac

|

acetylation of histone H3 lysine 18

site

|

|

H4K8ac

|

acetylation of histone H4 lysine 8

site

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:7–33. 2022.

|

|

2

|

Feng J, Li J, Qie P, Li Z, Xu Y and Tian

Z: Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) PGM5P4-AS1 inhibits lung cancer

progression by up-regulating leucine zipper tumor suppressor

(LZTS3) through sponging microRNA miR-1275. Bioengineered.

12:196–207. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bade BC and Dela Cruz CS: Lung cancer

2020: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med.

41:1–24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang LJ, Jeng CJ, Kung HN, Chang CC, Wang

AG, Chau GY, Don MJ and Chau YP: Tanshinone IIA isolated from

Salvia miltiorrhiza elicits the cell death of human

endothelial cells. J Biomed Sci. 12:347–361. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu L, Gao H, Wen T, Gu T, Zhang S and

Yuan Z: Tanshinone IIA attenuates AOM/DSS-induced colorectal

tumorigenesis in mice via inhibition of intestinal inflammation.

Pharm Biol. 59:89–96. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gao F, Li M, Liu W and Li W: Inhibition of

EGFR signaling and activation of mitochondrial apoptosis contribute

to tanshinone IIA-mediated tumor suppression in non-small cell lung

cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 13:2757–2769. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang B, Zou F, Xin G, Xiang BL, Zhao JQ,

Yuan SF, Zhang XL and Zhang ZH: Sodium tanshinone IIA sulphate

inhibits angiogenesis in lung adenocarcinoma via mediation of

miR-874/eEF-2K/TG2 axis. Pharm Biol. 61:868–877. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dawson MA and Kouzarides T: Cancer

epigenetics: From mechanism to therapy. Cell. 150:12–27. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Guo P, Chen W, Li H, Li M and Li L: The

histone acetylation modifications of breast cancer and their

therapeutic implications. Pathol Oncol Res. 24:807–813. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cheng Z, Li X, Hou S, Wu Y, Sun Y and Liu

B: K-Ras-ERK1/2 accelerates lung cancer cell development via

mediating H3K18ac through the MDM2-GCN5-SIRT7 axis.

Pharm Biol. 57:701–709. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen G, Zhu X, Li J, Zhang Y, Wang X,

Zhang R, Qin X, Chen X, Wang J, Liao W, et al: Celastrol inhibits

lung cancer growth by triggering histone acetylation and acting

synergically with HDAC inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 185:1064872022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ma H, Hu ZC, Long Y, Cheng LC, Zhao CY and

Shao MK: Tanshinone IIA microemulsion protects against cerebral

ischemia reperfusion injury via regulating H3K18ac and H4K8ac in

vivo and in vitro. Am J Chin Med. 50:1845–1868. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gulei D, Drula R, Ghiaur G, Buzoianu AD,

Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Tomuleasa C and Ciechanover A: The tumor

suppressor functions of ubiquitin ligase KPC1: From cell-cycle

control to NF-κB regulator. Cancer Res. 83:1762–1767. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang X, Bustos MA, Zhang X, Ramos RI, Tan

C, Iida Y, Chang SC, Salomon MP, Tran K, Gentry R, et al:

Downregulation of the ubiquitin-E3 ligase RNF123 promotes

upregulation of the NF-κB1 target SerpinE1 in aggressive

glioblastoma tumors. Cancers (Basel). 12:10812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD,

Kheradpour P, Stark A, Harp LF, Ye Z, Lee LK, Stuart RK, Ching CW,

et al: Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global

cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. 459:108–112. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hashemi M, Arani HZ, Orouei S, Fallah S,

Ghorbani A, Khaledabadi M, Kakavand A, Tavakolpournegari A, Saebfar

H, Heidari H, et al: EMT mechanism in breast cancer metastasis and

drug resistance: Revisiting molecular interactions and biological

functions. Biomed Pharmacother. 155:1137742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Serrano-Gomez SJ, Maziveyi M and Alahari

SK: Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition through

epigenetic and post-translational modifications. Mol Cancer.

15:182016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hou YS, Wang JZ, Shi S, Han Y, Zhang Y,

Zhi JX, Xu C, Li FF, Wang GY and Liu SL: Identification of

epigenetic factor KAT2B gene variants for possible roles in

congenital heart diseases. Biosci Rep. 40:BSR201917792020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhou X, Wang N, Zhang Y, Yu H and Wu Q:

KAT2B is an immune infiltration-associated biomarker predicting

prognosis and response to immunotherapy in non-small cell lung

cancer. Invest New Drugs. 40:43–57. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Megyesfalvi Z, Gay CM, Popper H, Pirker R,

Ostoros G, Heeke S, Lang C, Hoetzenecker K, Schwendenwein A,

Boettiger K, et al: Clinical insights into small cell lung cancer:

Tumor heterogeneity, diagnosis, therapy, and future directions. CA

Cancer J Clin. 73:620–652. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xu S and Liu P: Tanshinone II-A: New

perspectives for old remedies. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 23:149–153.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Song Q, Yang L, Han Z, Wu X, Li R, Zhou L,

Liu N, Sui H, Cai J, Wang Y, et al: Tanshinone IIA inhibits

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through hindering β-arrestin1

mediated β-catenin signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Front

Pharmacol. 11:5866162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yuan F, Zhao ZT, Jia B, Wang YP and Lei W:

TSN inhibits cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT

through regulating miR-874/HMGB2/β-catenin pathway in gastric

cancer. Neoplasma. 67:1012–1021. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Xie J, Liu J, Liu H, Liang S, Lin M, Gu Y,

Liu T, Wang D, Ge H and Mo SL: The antitumor effect of tanshinone

IIA on anti-proliferation and decreasing VEGF/VEGFR2 expression on

the human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell line. Acta Pharm Sin

B. 5:554–563. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cheng CY and Su CC: Tanshinone IIA may

inhibit the growth of small cell lung cancer H146 cells by

up-regulating the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and decreasing mitochondrial

membrane potential. Mol Med Rep. 3:645–650. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fang ZY, Zhang M, Liu JN, Zhao X, Zhang YQ

and Fang L: Tanshinone IIA: A review of its anticancer effects.

Front Pharmacol. 11:6110872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Luo W: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology

theory: Cancer as multidimensional spatiotemporal ‘unity of ecology

and evolution’ pathological ecosystem. Theranostics. 13:1607–1631.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Berndsen CE and Wolberger C: New insights

into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

21:301–307. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Iida Y, Ciechanover A, Marzese DM, Hata K,

Bustos M, Ono S, Wang J, Salomon MP, Tran K, Lam S, et al:

Epigenetic regulation of KPC1 ubiquitin ligase affects the NF-κB

pathway in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 23:4831–4842. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Shvedunova M and Akhtar A: Modulation of

cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23:329–349. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li L, Zhang J and Cao S: Lysine

acetyltransferase 2B predicts favorable prognosis and functions as

anti-oncogene in cervical carcinoma. Bioengineered. 12:2563–2575.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|