Introduction

In 2020, the global number of deaths from head and

neck cancer (HNC), which includes cancer of different regions, such

as the salivary glands, lips and oral cavity, larynx, hypopharynx,

nasopharynx and oropharynx, reached 440,000 (1,2). Head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), the predominant

histological type of HNC, originates from the mucosal epithelia of

the buccal cavity, pharynx and larynx, and accounts for >90% of

all cases of HNC (3,4). HNSCC can be categorized as human

papillomavirus (HPV)-positive or HPV-negative. The biological

characteristics of HNSCC notably differ between patients owing to

the impact of HPV (5). In a

previous study, patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

who tested positive for HPV had a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate

of 81.1%, while those with HPV-negative malignancies had a survival

rate of 39.7% (6).

The treatment of HNSCC is complicated by the

resistance of cancerous cells to chemotherapy. Resistance to

chemotherapy is primarily attributed to the inefficacy of most

chemotherapy medications for inducing cell death in resistant tumor

cells. This inefficacy is influenced by several factors, including

DNA damage repair, cell cycle regulation, immune invasion, tumor

progression, tumor recurrence induced by the impact of severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-mediated triggering of various

intracellular signaling axes, the presence of tumor-associated stem

cells, autophagy, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and the

effects of efflux pumps and metabolic rewiring (7–13).

Therefore, it is essential to develop new strategies to predict

clinical outcomes, and to design personalized treatment strategies

for patients with HNSCC, especially HPV-negative HNSCC.

In recent decades, several new non-apoptotic methods

of controlled cell death have been identified, such as pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, necroptosis, alkaliptosis and cuproptosis. These are

potentially useful tools in the context of cancer therapy (14–18).

Each of these processes has distinct biological mechanisms and

pathological characteristics. Ferroptosis, which was first proposed

by Dixon et al (19), is an

iron-dependent form of cell death that is characterized by the

intracellular generation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Previous studies have shown that there are marked differences

between ferroptosis and other forms of cell death, such as

apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy, in terms of morphology (for

example, shrunken mitochondria with increased membrane density),

biochemistry (iron-mediated lethal lipid ROS accumulation and no

ATP depletion), and genetics (governed by unique genes such as

ribosomal protein L8 and iron responsive element binding protein 2,

independent of Bax/Bak) (19,20).

Ferroptotic agents could provide an effective

approach to address the inefficacy of apoptosis-inducing

chemotherapeutics, since ferroptosis differs completely from

apoptosis in terms of its mechanism for inducing cell death

(19). The importance of

ferroptosis in the development and advancement of diverse diseases

has been recognized such as in malignancies, neurodegenerative

conditions and ischemia-reperfusion damage (21). There has been an increased focus on

the potential applications of ferroptosis in cancer therapy for

improving prognosis and overcoming drug resistance (18,22,23).

In HNSCC cells, ferroptosis can decrease or reverse tumor cell

resistance to chemotherapy (24–26).

The immune system controls the therapeutic response of cancer and

impedes progression, infiltration and metastasis. Immune

surveillance functions as a mechanism to detect, regulate and

eradicate malignant cells (27–29).

In vivo, treatment with programmed death-ligand 1 blockers

and glutathione (GSH) elimination can induce ferroptosis in tumor

cells and activate the antitumor activity of T lymphocytes

(30). A previous study

demonstrated that immunological B cells triggered an immune

response that suppressed tumor growth and was associated with

ferroptosis by increasing the dendritic cell count in patients with

oral cancer (31). Thus,

stimulating ferroptosis in tumor cells could be an effective

approach to tumor treatment.

To date, most studies have primarily focused on the

differences in ferroptosis between healthy individuals and patients

with HNSCC (31,32). However, the potential differences

between HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC in terms of

ferroptosis-related genes (FRGs) have received little attention.

Furthermore, previous studies (31,32)

have merely focused on verifying the molecular characteristics of

genes from the incorporated prognostic models, without an in-depth

analysis to determine their regulatory role in the ferroptosis of

HNSCC cells. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify the

FRGs with significant involvement in HPV-negative HNSCC (which has

a particularly poor prognosis), to develop a predictive model using

the FRG signatures of HPV-negative HNSCC and to explore the

associations of these FRGs with the immune microenvironment (IME).

The present study also aimed to verify the specific functions of

the most promising FRGs based on the prognostic model. The

successful identification of such genes is expected to assist

prognosis predictions and enable targeted treatment, thereby

enhancing the clinical outcomes of patients with HPV-negative

HNSCC.

Materials and methods

Data sources

The source of the clinical data was a publication by

Hoadley et al (33). The

HNSCC datasets containing the transcript data were attained from

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) on February 17, 2024.

There were 487 HNSCC samples, including 415 HPV-negative and 72

HPV-positive samples, included in the TCGA-HNSCC dataset. Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and hallmark datasets from the Molecular

Signatures Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/) were

utilized to identify relevant genes and pathways. The database used

for researching ferroptosis and FRGs is available at http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb. Genes associated

with ferroptosis, including driver, suppressor and marker genes,

were downloaded to avoid omission. Additionally, GSE83519 (34) data were downloaded from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

Identification of FRGs

First, the FRG expression matrix was obtained using

R software (RStudio 2022.07.2). The ‘limma’ package of R (version

3.52.4) was used to identify differences in the expression of FRGs

between the HPV-negative and HPV-positive samples from the

TCGA-HNSCC group.

Consensus clustering

Consensus clustering was conducted using the

k-means method in the ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ package of R

(version 1.60.0) to identify distinct patterns related to the FRGs.

The clustering accuracy was confirmed using Uniform Manifold

Approximation and Projection (UMAP) in the ‘ggplot2’ package of R

(version 3.3.6).

Identification and validation of

prognostic signatures based on the FRGs

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator

(LASSO) regression analysis was conducted using the ‘glmnet’

package of R (version 4.1.4) to identify genes associated with

survival. Next, 10-fold cross-validation was used to determine the

penalty regularization value (λ). The key genes and their

accompanying coefficients were then determined using multivariate

Cox regression analysis. In total, 10 FRGs were selected as risk

signatures based on the optimal λ values and their corresponding

coefficients. The following formula was used to determine the risk

score for each patient using the new FRG signature:

Riskscore=Σexpi × βi where β and exp

represent the coefficient and the expression level of the

corresponding gene in the multivariate Cox regression model,

respectively.

For external validation, it was found that most Gene

Expression Omnibus datasets either lacked explicit HPV status

annotations or did not include paired prognostic information,

making them unsuitable for validating the constructed

HPV-subtype-specific prognostic model. Thereafter, comprehensive

internal validation on the TCGA-HNSC cohort was performed by

randomly partitioning the data into three independent subsets:

Training, testing and combined cohorts. The predictive performance

of the model was assessed through time-dependent receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve analyses, and the area under the curve

(AUC) was defined as the area enclosed by the ROC curve and the

coordinate axes. Additionally, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

curves were generated. The ROC curve and Kaplan-Meier survival

analyses were performed using R software (RStudio 2022.07.2)

through ‘timeROC’ (version 0.4) and ‘survival’ (version 3.4.0) R

packages, respectively.

Construction and examination of the

predictive nomogram

The nomogram was generated based on risk scores and

clinicopathological features. Internal validation of accuracy was

performed using a calibration curve. The predictive performance of

the nomogram was evaluated using the time C-index. To assess the

net clinical benefit, decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed

(35).

Associations between immune cell

infiltration and risk score

The quantification of infiltrated immune cell

percentages was conducted using both the CIBERSORT R script and the

single sample GSEA R script following previously reported methods

(36). The distributions of immune

cell types among the groups were compared using CIBERSORT R. Each

sample showed an aggregated inferred score of 1 for the immune cell

types. Score 1 indicates that the sum of the relative proportions

of all immune cell types inferred in the sample equals 1, which is

equivalent to 100%. Furthermore, Spearman's rank correlation

analysis was used to ascertain the associations between the

infiltration of immune cells and risk scores.

Drug sensitivity analysis

For determining how effectively a patient responded

to treatment, drug sensitivity, also known as the half maximum

inhibitory concentration (IC50), was an essential

statistic. Through the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer

database, the IC50 measurements were utilized to

demonstrate the sensitivity of each drug to each sample. The R

package known as ‘oncoPredict’ (37) was utilized to make predictions

regarding the response of anticancer treatments for each HNSCC

sample that was differentiated into the low-risk and high-risk

groups. All statistical analyses are represented using the

‘ggplot2’ R package (version 3.3.6).

Cell culture

The HNSCC CAL27 (HPV-negative) and UPCI-SCC-090

(HPV-positive) cell lines were obtained from Procell Life Science

& Technology Co. Ltd., and Zhejiang Meisen Cell Technology Co.,

Ltd., respectively. CAL27 cells were cultured in high-glucose

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Procell Life Science

& Technology Co. Ltd.) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Procell Life Science & Technology Co. Ltd.), while UPCI-SCC-090

cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 (Zhejiang Meisen Cell Technology

Co., Ltd.) with 10% FBS. The cells were maintained at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from CAL27 and UPCI-SCC-090

cells using the Total RNA extraction kit (cat. no. R1200; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and reverse

transcribed into complementary DNA using the reverse transcription

kit (cat. no. 11141ES60; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

following the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed using

Realtime PCR fluorescence quantitative kit (Hieff® qPCR

SYBR Green Master Mix; cat. no. 11201ES08; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and a Real-time Fluorescence Quantitative

PCR Instrument (Suzhou Molarray Co., Ltd.) and the following

thermocycler conditions: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at

95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 20 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. The primer

sequences are shown in Table SI.

The 2−ΔΔCq method was used to calculate relative gene

expression (38). GAPDH was used as

an internal control to normalize the expression levels of target

genes, correcting for variations in RNA input and RT

efficiency.

Cell transfection of Tribbles

pseudokinase 3 (TRIB3) small interfering RNA (siRNA)

CAL27 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (cat. no.

F603201-9001; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) at a density of

1.5×105 cells/ml, with 2 ml in each well, 24 h before

transfection. The siRNA was purchased from OBiO Technology

(Shanghai) Corp., Ltd. and Lipofectamine™ 3000 (cat. no. L3000008;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for transfection. The

final concentration of the siRNA knockdown reagent (siTRIB3) and

siRNA negative control reagent was 20 pmol/µl, and the experimental

volume used for each was 5 µl. The cells were divided into the

blank control, negative control and knockdown groups. The blank

control group was cells + complete medium, the negative control

group was cells + complete medium + transfection reagent + negative

control siRNA and the knockdown group was cells + complete medium +

transfection reagent + target siRNA. Next, the cells were placed

into a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for further culture. The

three TRIB3 siRNAs were transfected separately and the siRNA

resulting in the most significant knockdown was selected for

subsequent experiments. After culturing for 48 h, RT-qPCR was

performed to examine the transfection efficiency and the most

efficient siRNA was chosen for the next experiment. The siRNA

sequences are displayed in Table

SII.

Cell transfection for TRIB3

overexpression

UPCI-SCC-090 cells were digested and seeded into a

6-well plate 24 h prior to transfection at a density of

2×105 cells/ml, with 2 ml in each well. The

overexpression plasmid [pcDNA3.1(+)-EGFP] was purchased from SYNBIO

Technology (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. (Suzhou Hongxun Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). Lipofectamine™ 3000 (cat. no. L3000008; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was used to transfect the cells. The final

concentration of the overexpression plasmid and empty plasmid was 1

µg/µl, and the experimental volume used for each was 2 µl. The

cells were divided into the blank control, negative control and

overexpression groups. The blank control group was cells + complete

medium, the negative control group was cells + complete medium +

transfection reagent + empty vector plasmid, and the overexpression

group was cells + complete medium + transfection reagent +

overexpression plasmid. Next, the cells were incubated at 37°C in a

5% CO2 incubator. After 5 h, the medium was replaced

with 10% FBS-DMEM, and the cells were cultured for another 48 h

before subsequent experiments. The transfection efficiency was

verified by RT-qPCR.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from the HNSCC cells.

For protein extraction, RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B;

Beyotime Biotechnology) was combined with a protease/phosphatase

inhibitor (cat. no. P1045; Beyotime Biotechnology) cocktail at a

1:100 ratio, and the mixture was used immediately. Next, for the

quantification of protein concentration, a BCA protein assay kit

(cat. no. PC0020; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) was employed, following the manufacturer's recommended

protocol. For electrophoresis, the processed samples were loaded

onto the gel with a total mass of 20 µg protein per well. Following

separation using 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis, the extracted proteins were transferred onto

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (cat. no. IPVH00010;

MilliporeSigma). Subsequently, the membranes were blocked using 5%

non-fat milk for 3 h on a shaker at room temperature and incubated

overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies targeting GAPDH (cat. no.

10494-1-AP; 1:5,000; Proteintech Group Inc.), TRIB3 (cat. no.

DF7844; 1:1,000; Affinity Biosciences, Ltd.) and acyl-CoA

synthetase long chain family member 1 (ACSL1; cat. no. GTX112430;

1:1,000; GeneTex, Inc.). The secondary antibody was a

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (cat. no.

bs-0295G-HRP; 1:5,000; BIOSS), which was incubated with the

membrane on a horizontal shaker at room temperature for 1.5 h.

Images were acquired with the Automated Chemiluminescent Image

Analysis System (Tanon 5200; Tanon Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) following ECL (cat. no. P0018S-2; Beyotime Biotechnology)

substrate incubation. Lastly, the intensity of the protein bands

was semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.53; National

Institutes of Health).

Quantification of ROS

ROS were quantified using the ROS fluorometric assay

kit (cat. no. E-BC-K138-F, Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. CAL27 cells

(1×106 cells/well) were cultured in 6-well plates.

Cultured or transfected cells were treated in the dark with the ROS

solution for 20 min at 37°C, then the fluorescence intensity was

evaluated by an inverted fluorescence microscope [XD-RFL; Sunny

Optical Technology (Group) Co., Ltd.].

Measurement of intracellular Fe2+

content. The intracellular Fe2+ concentration was

quantified using Cell Ferrous Iron Colorimetric assay reagent (cat.

no. E-BC-K881-M; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Briefly, the cultured or transfected cells (1×106) were

mixed with 0.2 ml reagent 1 and incubated in an ice bath for 10 min

to facilitate lysis, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for

10 min at room temperature. For further analysis, the absorbance of

the supernatants at 593 nm was measured using a microplate reader

(Synergy H4; BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Measurement of cellular GSH

The GSH concentration in CAL27 cells was measured

using the Reduced GSH Colorimetric Assay Kit (cat. no. E-BC-K030-M;

Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) following the

manufacturer's protocol. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured

using a microplate reader (Synergy H4; BioTek; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.).

Measurement of cellular

malondialdehyde (MDA)

Cellular MDA was quantified using the

Malondialdehyde Colorimetric Assay Kit (cat. no. E-BC-K028-M; Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's

instructions. Transfected cells were harvested using an extraction

solution. The test samples, blank tubes and standard tubes were

incubated at 100°C for 40 min and then cooled to room temperature

in a water bath. The resulting samples were centrifuged in

Eppendorf (EP) tubes at 1,078 × g for 10 min at room temperature

and 0.25 ml supernatant was transferred to the enzyme-labeled

plate. The absorbance of each well was measured at 532 nm using a

microplate reader (Synergy H4; BioTek; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.).

Flow cytometry

CAL27 cells (1×106) were cultured in

6-well plates. After transfection with siTRIB3, the cells were

incubated for 24 h before being treated with propidium iodide

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at

37°C. Subsequently, the cell cycle distribution was analyzed by

flow cytometry (NL-CLC3000; Cytek Biosciences, Inc.) and FlowJo

software (10.8.1), with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy

CAL27 cells (both the control group and those

transfected with siTRIB3 together with the culture medium) were

subjected to centrifugation at 42-107 × g for 5 min at room

temperature, followed by careful removal of the resulting

supernatant with 1 ml remaining. The CAL27 cell pellet was gently

resuspended in the remaining media and transferred to a 1.5-ml EP

tube. After allowing the mixture to settle for 1 h, the supernatant

was meticulously extracted and 1 ml pre-chilled 2.5% glutaraldehyde

was gradually added to the tube along the periphery for fixation.

The tube was then placed in a refrigerator at 4°C for at least 2 h.

The cells were subsequently fixed in 1% osmic acid at 4°C for 2 h.

Following fixation, the cells were detached from the plastic

surface and dehydrated using ethanol and acetone, respectively. The

specimens were embedded in EPON812 embedding solution (SPI-Pon 812

Kit; cat. no. 02663-AB; SPI Supplies; Structure Probe, Inc.) for

2–3 h at 37°C and sectioned to 70 nm. Thereafter, double staining

was carried out: First with 2% uranyl acetate (staining time: 15–20

min at room temperature) and then with lead citrate (staining time:

10–15 min in a CO2-free environment to avoid

precipitation), ensuring sufficient contrast for ultrastructural

observation. The sections were then analyzed using an HT7800 (80

kV) transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Ltd.).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Samples from patients with primary HNSCC (with or

without comorbidities) who had undergone surgery at the Department

of Pathology, Heping Hospital Affiliated to Changzhi Medical

College (Changzhi, China) from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2022

were included. The patient samples for IHC were used

retrospectively. All patients were aged >18 years and had not

undergone any other prior treatment (including radiation and

chemotherapy). Patients with a history of prior treatments

(radiotherapy or chemotherapy) or those with recurrent HNSCC were

excluded from the study. In accordance with the predefined

inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 179 eligible cases

were eventually enrolled. Among these patients, the age range was

38 to 87 years, with a mean age of 63.2 years. Regarding sex

distribution, 121 patients were men (accounting for 67.6% of the

total) and 58 were women (representing 32.4%).

For paraffin-embedded slides (0.4 µm), first the

sections were baked in a 60–65°C preheated oven for 15–20 min to

melt the surface paraffin. Then, the sections were sequentially

immersed in xylene to completely remove residual paraffin, followed

by gradual rehydration via gradient ethanol solutions (from high to

low concentration) and finally transitioned to an aqueous

environment. After antigen retrieval of paraffin sections (EDTA

buffer, 95–100°C, 20 min) and subsequent cooling to room

temperature followed by 2–3 washes with PBS (3–5 min each),

permeabilization was performed by immersing the sections in a

paraffin section-compatible permeabilization reagent (0.3% Triton

X-100 in PBS) for 10–15 min. Next, the sections were blocked with

10% bovine serum albumin (cat. no. C0221; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 30 min and then

incubated with primary antibodies against TRIB3 (cat. no. bs-7538R;

1:300; BIOSS) and p16 (cat. no. HA721415; 1:200; HUABIO) at 4°C

overnight. Next, the samples were incubated with goat anti-rabbit

IgG/biotin secondary antibody (cat. no. SHB134; 1:200; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 2 h at 37°C.

Hematoxylin was used to counterstain the nucleus (1 min, room

temperature). Finally, the sections were incubated with 0.05–0.1%

3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (containing 0.01%

H2O2, dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer) at room

temperature for 3–10 min to allow brown precipitates to form at the

target antigen-binding sites, followed by terminating the staining

reaction with distilled water. Then, the sections were scanned

using a panoramic slice scanner. The present study was approved by

the Human Ethical Committee of Heping Hospital Affiliated to

Changzhi Medical College [Changzhi, China; approval no. 2023(027)].

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the committee as

the risks involved in the study were very low and did not cause

significant harm to the participants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism (version 10.0.3; Dotmatics) and R (version 4.2.1). The

results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Two-group

comparisons were performed using the unpaired t-test, while

multiple-group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and

Tukey's HSD post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

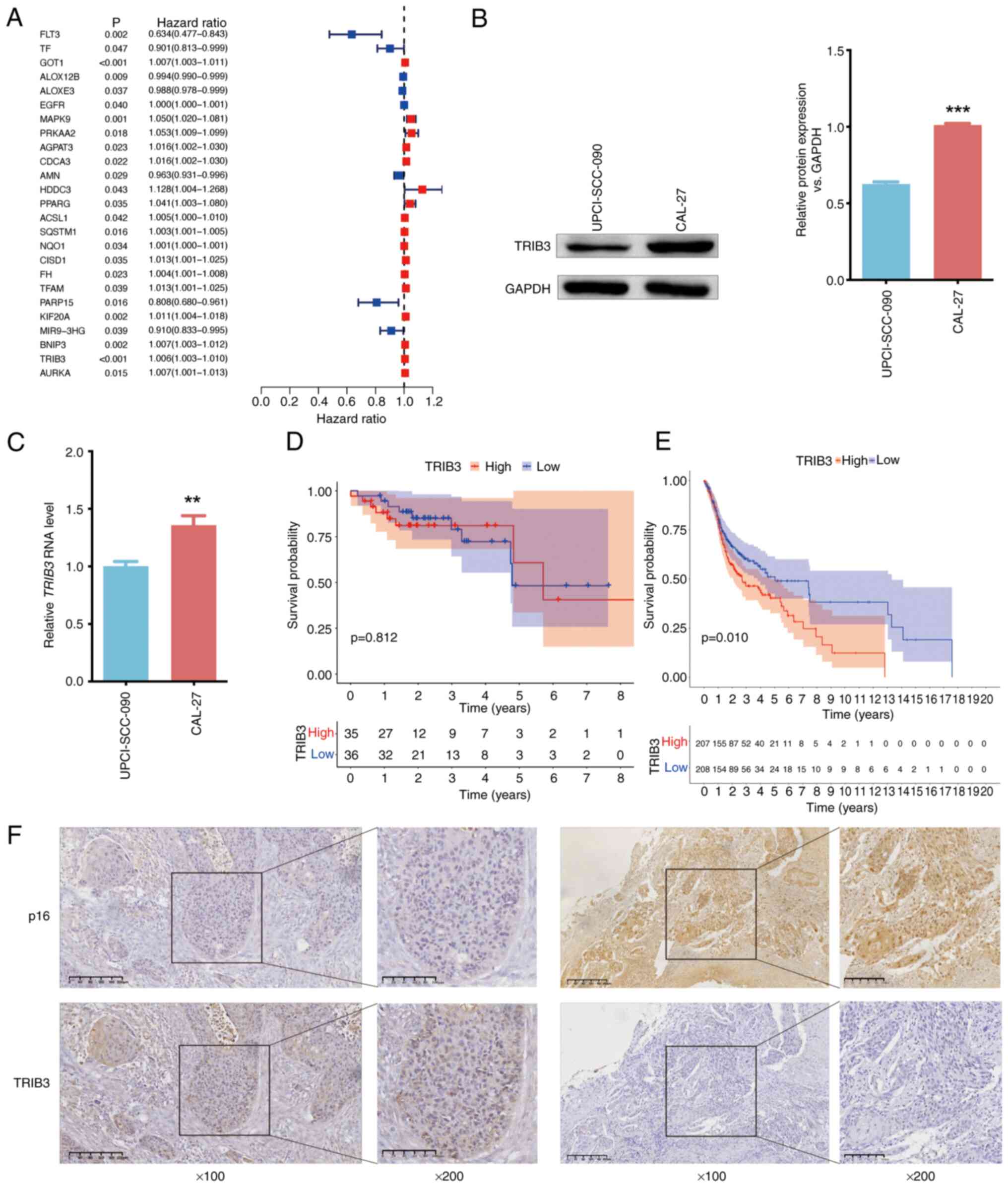

Identification of FRGs associated with

prognosis

In total, 845 FRGs were identified in the

ferroptosis database. A comparison between HPV-negative and

HPV-positive samples identified 299 differentially expressed FRGs

from TCGA-HNSC. When HPV-negative was compared with HPV-positive

samples, 208 genes were downregulated, and 91 genes were

upregulated in the HPV-negative samples (Table SIII). Univariate Cox regression

analysis indicated that 25 of the 300 FRGs had a significant

association with survival, as depicted in the forest plot

(P<0.05; Fig. 1A). TRIB3

was significantly elevated in HNSCC samples according to the

results of TCGA-HNSCC (Fig. S1)

and GSE83519 (Fig. S2) analyses.

TRIB3 was also more upregulated in HPV-negative samples than

in HPV-positive samples (Table

SIII and Fig. S3), suggesting

that it may be particularly important in HPV-negative HNSCC.

Western blotting (Fig. 1B) and

RT-qPCR (Fig. 1C) confirmed that

the difference in TRIB3 expression between HNSCC CAL27 (HPV

negative) and UPCI-SCC-090 (HPV positive) cells aligned with the

results of the bioinformatics analysis. Additionally, ACSL1

expression was also upregulated in HPV-negative cells (Fig. S4). TRIB3 was associated with

the prognostic outcome of patients with HPV-negative HNSCC, but not

with that of patients with HPV-positive HNSCC (Fig. 1D and E). The immunohistochemistry

results from paraffin-embedded slides of TRIB3 were consistent with

those of western blotting and RT-qPCR from cell culture experiments

(Fig. 1F).

Consensus clustering of the 25 FRGs in

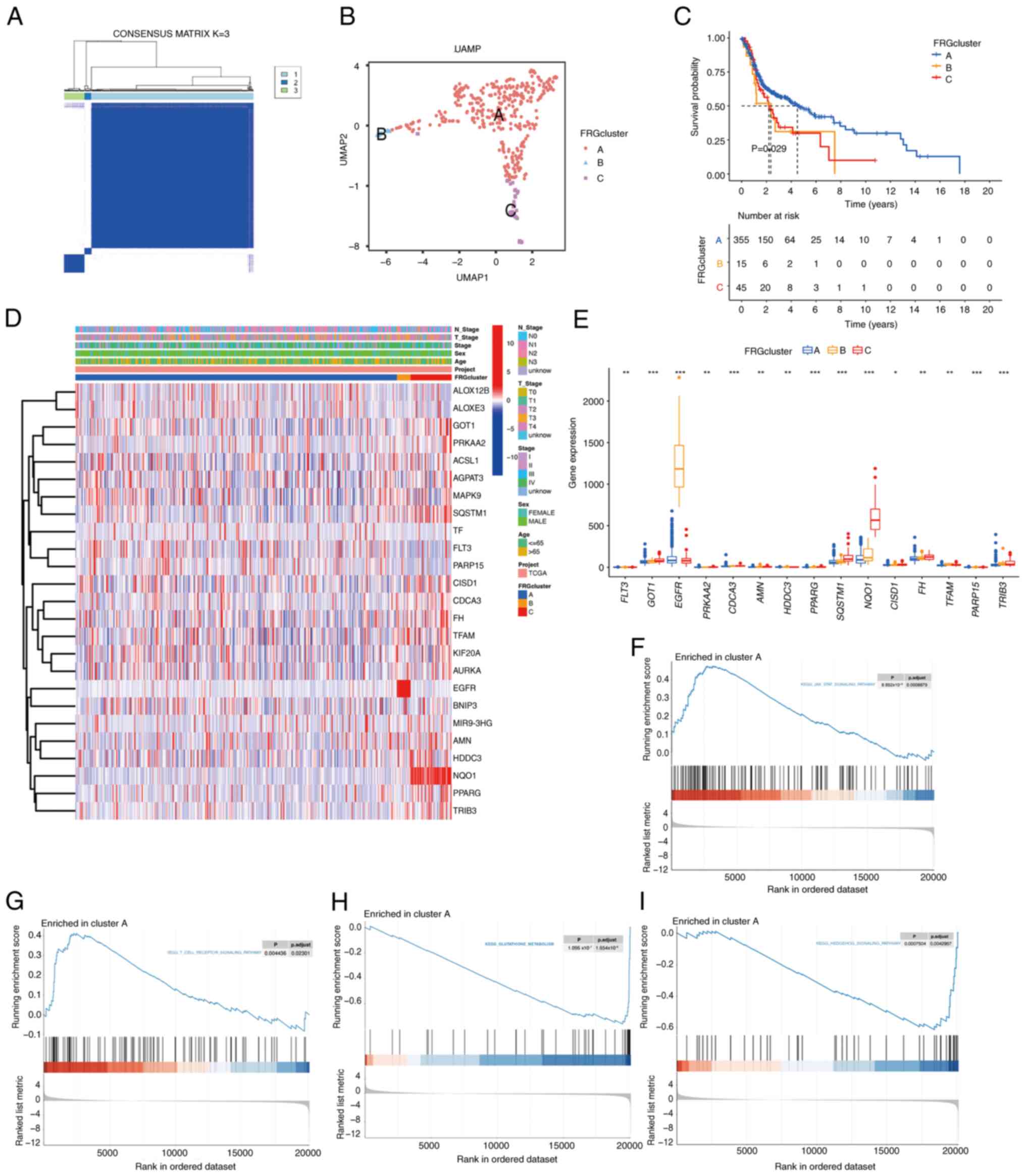

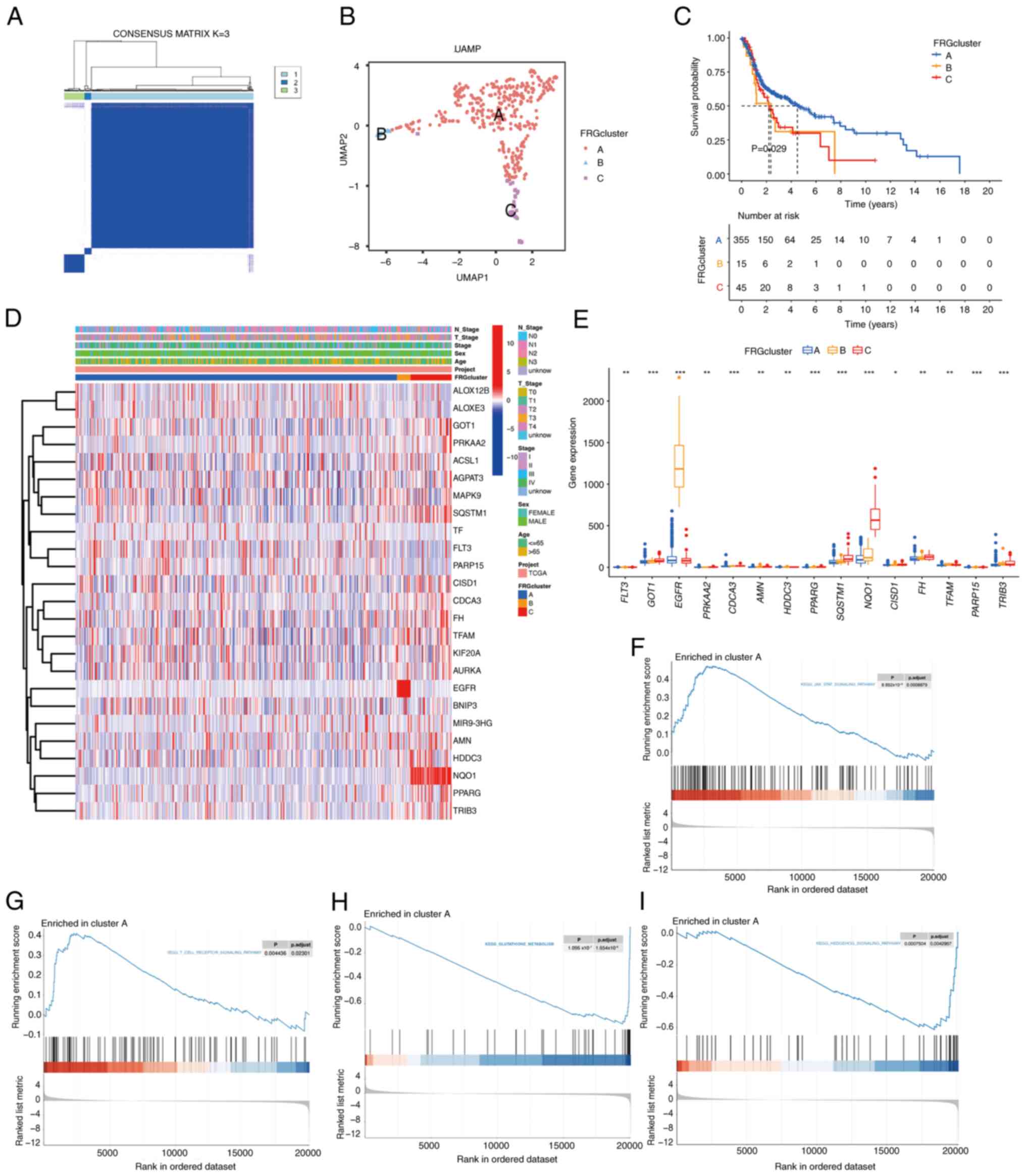

HPV-negative HNSCC

To understand the significance of the FRGs in

HPV-negative HNSCC, consensus clustering on the 25

prognosis-associated FRGs was conducted using the

‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ package in R software. The HPV negative

TCGA-HNSC cohort was classified into three clusters at K=3

(Fig. 2A). Following this, UMAP was

used to verify the accuracy of the clustering, which indicated that

the three clusters were accurately distinguished at K=3 (Fig. 2B). The OS analysis revealed

significant variations in prognoses among the three subgroups and

cluster A had a favorable prognosis (P=0.029; Fig. 2C). The heatmap in Fig. 2D illustrates the expression of the

FRGs and the respective clinicopathological features of the three

clusters. For example, epidermal growth factor receptor

(EGFR) was significantly upregulated in cluster B, and T3

stage. Furthermore, the transcription patterns of the FRGs in the

three subgroups were depicted using boxplots. The expression levels

of EGFR and transcription factor A, mitochondrial were

markedly higher in cluster B than in clusters A and C, while the

expression levels of NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1, TRIB3,

glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1, Sequestosome 1, CDGSH iron

sulfur domain 1 and fumarate hydratase were higher in cluster C

than in clusters A or B (Fig. 2E).

Therefore, these differentially expressed FRGs may serve as

important determinants for estimating the prognosis of patients

with HNSCC, and based on their association with OS, they may be

potentially useful therapeutic targets. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis performed

using the GSEA package revealed different enrichment pathways

between clusters A and B. This analysis was performed to identify

significantly enriched pathways in clusters A and to clarify the

unique activation or inhibition of metabolic, signal transduction,

disease-related and other pathways in clusters A (Fig. 2F-I). Cluster A displayed significant

involvement in critical pathways, such as

‘KEGG_JAK_STAT_SIGNALING_PATHWAY’,

‘KEGG_T_CELL_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY’,

‘KEGG_GLUTATHIONE_METABOLISM’ and

‘KEGG_HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING_PATHWAY’, all of which play essential

roles in tumorigenesis.

| Figure 2.FRG-related subgroups of HPV-negative

HNSCC samples from TCGA. (A) Consensus clustering. The consensus

matrix of K=3 was obtained. (B) UMAP identified three clusters

according to FRG expression. (C) Overall survival in the three

clusters (P=0.029). (D) Heatmap of the clinicopathological

characteristics and FRG expression associated with the three

clusters. (E) The expression of FRGs in the three clusters.

Comparative KEGG pathway enrichment between clusters A and B, as

evaluated by GSEA. Cluster A displayed significant involvement in

(F) KEGG_JAK_STAT_SIGNALING_PATHWAY, (G)

KEGG_T_CELL_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY, (H)

KEGG_GLUTATHIONE_METABOLISM and (I)

KEGG_HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING_PATHWAY. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. FRGs, ferroptosis related genes; HPV, human

papillomavirus; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; TCGA,

The Cancer Genome Atlas; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and

Projection; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GSEA,

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. |

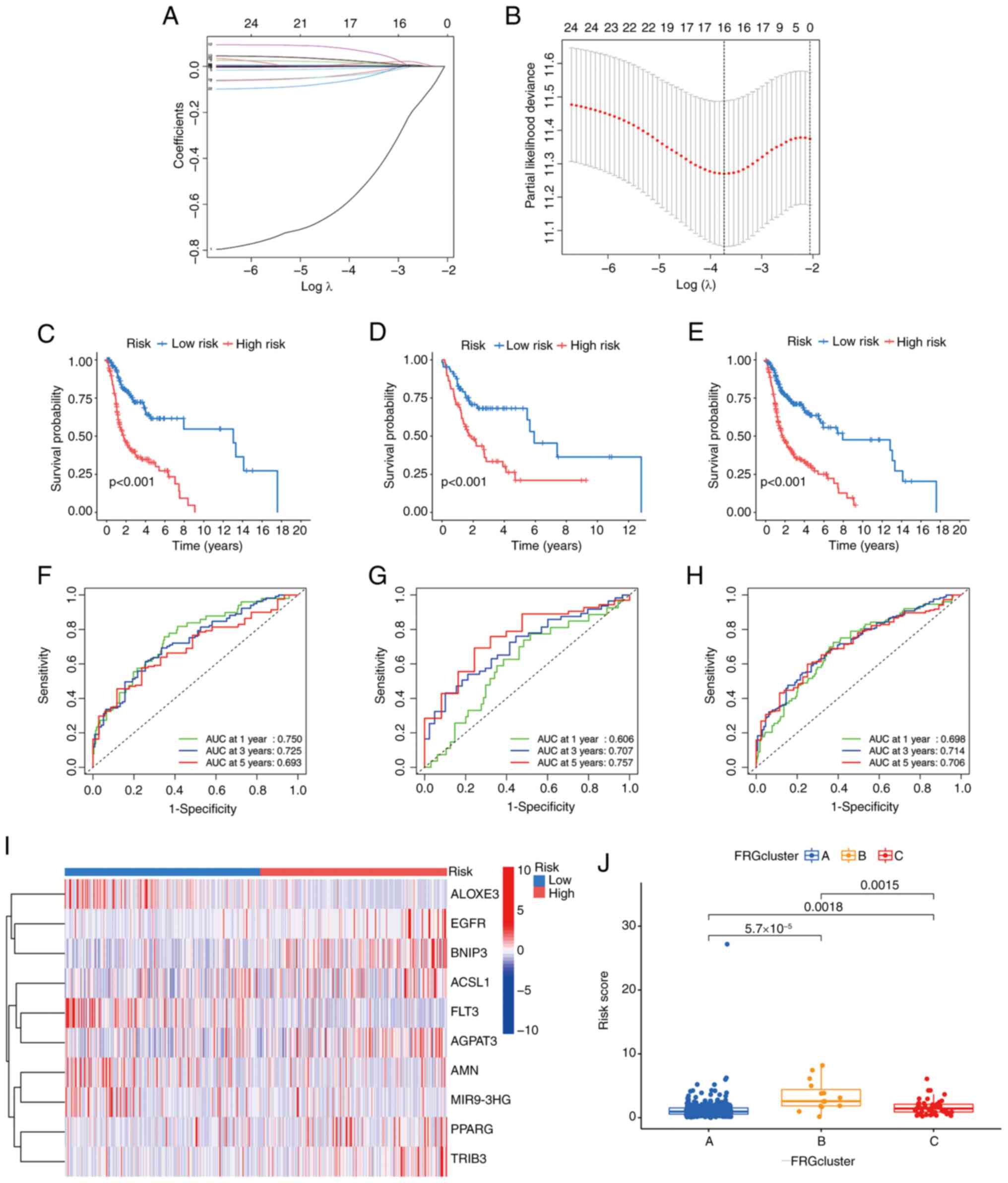

Identification of prognostic FRG

signatures using the FRG score model

The clinical utility of the 25 FRGs was evaluated

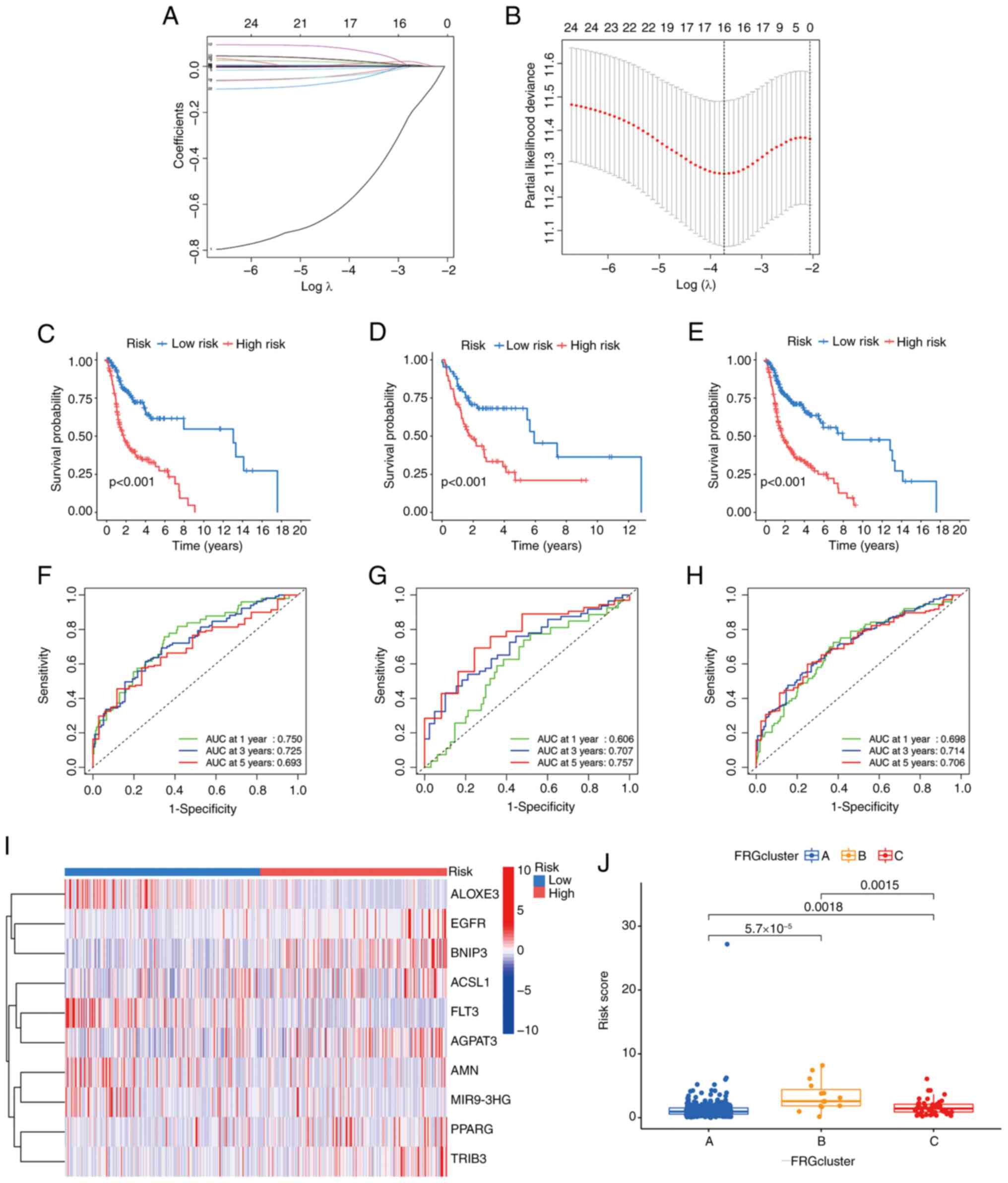

using the LASSO-penalized Cox analysis (Fig. 3A and B). Following the core steps of

LASSO Cox-based gene selection: First, non-zero coefficient FRGs

(that is FRGs contributing to survival prediction and free of

multicollinearity) were initially extracted from the 25 candidates;

second, these non-zero coefficient FRGs were further filtered by

prioritizing those with larger absolute regression coefficients. In

total, 10 prognostic FRGs, including TRIB3, EGFR,

1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 3

(AGPAT3), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

(PPARG), lipoxygenase-3 (ALOXE3), BCL2-interacting

protein 3 (BNIP3), ACSL1, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3

(FLT3), amnion associated transmembrane protein (AMN)

and MIR9-3 host gene (MIR9-3HG) were obtained from these 25

FRGs. The association coefficients are presented in Table SIV, and the final risk score

derived from the 10 FRG signatures is referred to as the

‘FRGscore.’ The prognostic index (FRGscore) was calculated

according to the following formula: (0.00078 × EGFR

expression) + (0.028 × AGPAT3 expression) + (0.043 ×

PPARG expression) + (0.006 × ACSL1 expression) +

(0.007 × BNIP3 expression) + (0.004 × TRIB3

expression)-(0.02 × ALOXE3 expression)-(0.798 × FLT3

expression)-(0.05 × AMN expression)-(0.098 × MIR9-3HG

expression). According to the FRGscore, the training, testing and

combined cohorts were divided into high- and low-risk groups.

Individuals or cases with scores above the median score were

categorized as high-risk, and those below or equal to the median

score as low-risk. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated that

the prognoses of the training, testing and combined cohorts in the

high-risk group were poor (Fig.

3C-E). Using the FRGscore model, the time-dependent ROC curves

exhibited notable predictive efficacy by evaluating OS at 1-, 3-

and 5-year intervals. This was demonstrated by the AUC being

>0.7, except the AUC at 1 year in the testing (0.606) and

combined (0.698) cohorts (Fig.

3F-H). This supports the reliability of the predictive model

for assessing the predefined outcomes. The heatmap shown in

Fig. 3I illustrates the expression

of the FRGs across various risk scores: ALOXE3, FLT3, AMN

and MIR903GH showed greater expression levels in the

high-risk group, whereas EGFR, BNIP3, ACSL1, AGPAT3, PPARG

and TRIB3 exhibited higher expression in the low-risk group.

Additionally, the risk scores of the previously established three

clusters varied significantly from each other (Fig. 3J).

| Figure 3.Determination of the prognostic FRGs

in HPV-negative HNSCC samples from TCGA. (A) 10 prognostic FRGs

were determined by the LASSO regression analysis and validated by

10-fold cross-validation. (B) The graph of the coefficient profile

illustrated 10 prognostic FRGs. Kaplan-Meier survival curves

showing the prognoses of the different risk groups in the (C)

training, (D) testing and (E) combined cohorts. Time-dependent ROC

curves were generated for OS at 1, 3 and 5 years using the (F)

training, (G) testing and (H) combined cohorts. (I) The heatmap of

the 10 hub FRGs for both risk groups. (J) Evaluation of the risk

scores among the three previously established clusters. FRGs,

ferroptosis related genes; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; LASSO,

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator; ROC, receiver

operating characteristic; HPV, human papillomavirus; ALOXE3,

lipoxygenase-3; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; BNIP3,

BCL2-interacting protein 3; ACSL1, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain

family member 1; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; AGPAT3,

1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 3; AMN, amnion

associated transmembrane protein; MIR9-3HG, MIR9-3 host gene;

PPARG, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; TRIB3,

tribbles pseudokinase 3. |

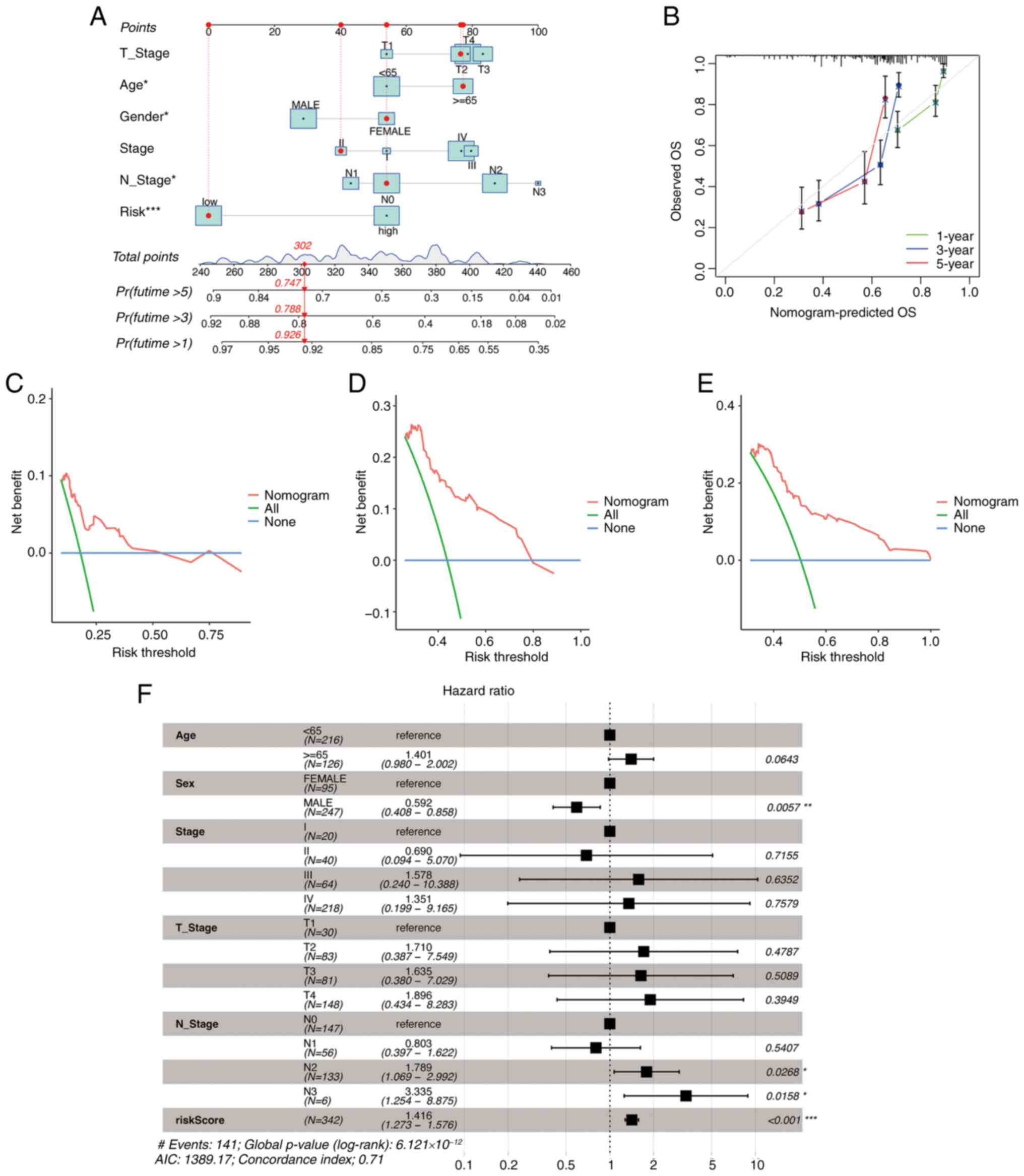

Development of a prognostic nomogram

for patients with HPV-negative HNSCC

For the nomogram integrating FRGscore and clinical

data, the impact of clinicopathological variables was considered by

first screening prognosis-related variables (such as age and tumor

stage) via univariate Cox regression, then validating their

independent prognostic value by multivariate Cox regression and

including significant variables (P<0.05) together with FRGscore,

and finally assigning each variable a prognostic weight-based score

scale to quantify contributions for multi-dimensional outcome

prediction (Fig. 4A). The accuracy

of the nomogram was verified through a calibration curve (Fig. 4B). DCA determines the possible

patient benefit of clinical prediction models, diagnostic

procedures and molecular markers (35). The reliability of the nomogram for

estimating the short- and long-term survival of patients with HNSCC

was confirmed by the DCA (Fig.

4C-E). The multivariable Cox regression analysis showed that

the primary influencing factors in the nomogram were sex, N stage

and risk score (Fig. 4F). The

constructed nomogram may thus be valuable for the prediction of

clinical prognosis.

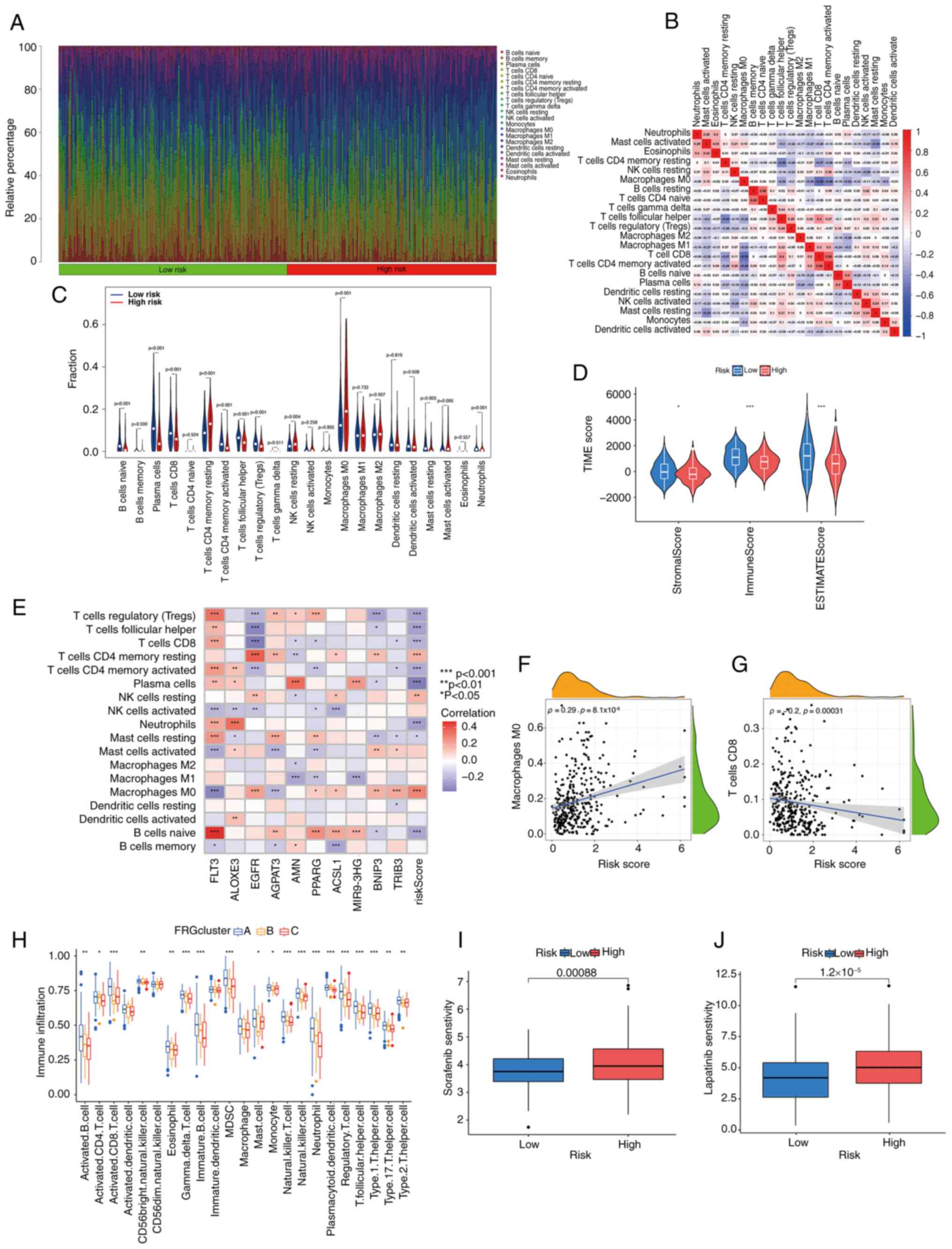

Immune infiltration in patients with

HPV-negative HNSCC

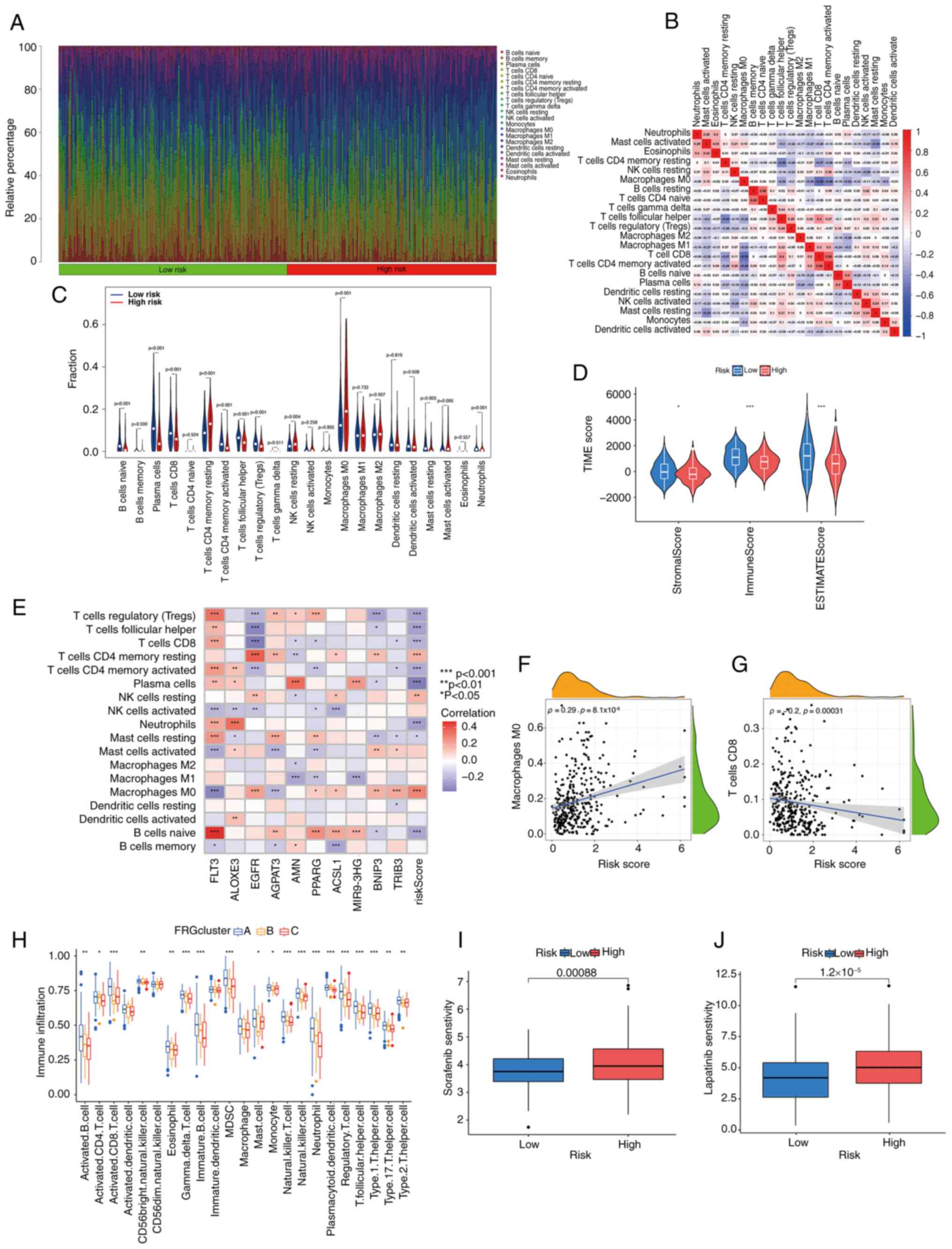

Both tumor progression and the efficacy of

immunotherapy are influenced by the IME. To distinguish between the

risk groups of patients with HPV-negative HNSCC, the tumor IME was

investigated in more detail. The CIBERSORT R script was used to

assess the percentages of infiltrating immune cell types.

HPV-negative HNSCC tumors were ranked based on the risk score, and

associations between the immune cell types and risk scores were

observed (Fig. 5A). The low-risk

group represented a higher proportion of T cells, B cells and NK

cells, whereas the high-risk group represented a higher proportion

of macrophages, mast cells, eosinophils and neutrophils. The

correlations among immune cells in patients with HNSCC are

displayed in Fig. 5B. T cells CD4

memory activated was positively associated with T cells CD8

(r=0.58), while T cells CD8 was negatively associated with

macrophages M0 (r=−0.53). This may provide insights into the

specific IME associated with certain tumor types. In patients with

low-risk HNSCC without HPV infection, M0 macrophages accounted for

a lower proportion of immune cell components, as well as

CD8+ T cells, T cells CD4 memory activated, NK cells

resting and mast cells activated (Fig.

5C).

| Figure 5.Exploring the immune microenvironment

of HPV-negative HNSCC based on the various risk scores and clusters

in HPV-negative HNSCC samples from TCGA. (A) Different proportions

of infiltrating immune cells with distinct risk scores. (B) The

associations among immune cells. (C) Comparison of immune cell

components between the risk groups. (D) The predicted score of the

gene expression patterns in both risk groups. (E) The connection

between immune cells and the 10 main ferroptosis-related genes.

Associations of (F) the number of M0 macrophages and (G) the number

of CD8+ T cells in HNSCC-negative tissues with risk

scores. (H) The variation in the extent of immune cell infiltration

across the three FRG clusters. The susceptibility of both risk

groups to (I) sorafenib and (J) lapatinib. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HPV,

human papillomavirus; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TME, tumor

microenvironment; FRG, ferroptosis related gene; FLT3, FMS-like

tyrosine kinase 3; ALOXE3, lipoxygenase-3; EGFR, epidermal growth

factor receptor; AGPAT3, 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate

O-acyltransferase 3; AMN, amnion associated transmembrane protein;

PPARG, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; ACSL1,

acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 1; MIR9-3HG, MIR9-3

host gene; BNIP3, BCL2-interacting protein 3; TRIB3, tribbles

pseudokinase 3. |

Subsequently, the stromal and immune scores for both

risk groups were determined using the estimated score of the

expression profile. The core purpose of calculating stromal and

immune scores for both risk groups is to link the ‘FRGscore-based

molecular risk stratification’ with ‘tumor microenvironment

characteristics’, which not only provides TME-level support for the

mechanism by which FRGscore affects prognosis but also offers a

basis for formulating subsequent intervention strategies (such as

immunotherapy) for different risk groups. The StromalScore,

ImmuneScore and ESTIMATEScore represented a significant difference

between the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, the infiltration of

various immune cell types was relatively significantly correlated

with the 10 FRGs that were used to develop the FRGscore model

(Fig. 5E). Elevated risk scores

were linked to a greater number of M0 macrophages (Ρ=0.29; Fig. 5F) but fewer CD8+ T cells

(Ρ=−0.2; Fig. 5G). Furthermore,

there was notable variation in the extent of immune cell

infiltration across the three FRG clusters (Fig. 5H). Cluster B showed fewer activated

CD8 cells, MDSCs, mast cells, type 1 T helper cells and type 2 T

helper cells than the other two clusters, while cluster C showed

fewer activated B cells, activated CD4 T cells, gd T, immature B

cells, natural killer T cells, neutrophils, plasmacytoid dendritic

cells, regulatory T cells and type 17 T helper cells. The

‘pRRophetic’ package in R was used to assess therapeutic drug

susceptibility in the different risk groups. A significant

association was observed between the risk score and the

responsiveness to various drugs, for example, samples with high

risk were more sensitive to the two drugs sorafenib and lapatinib

(Fig. 5I and J).

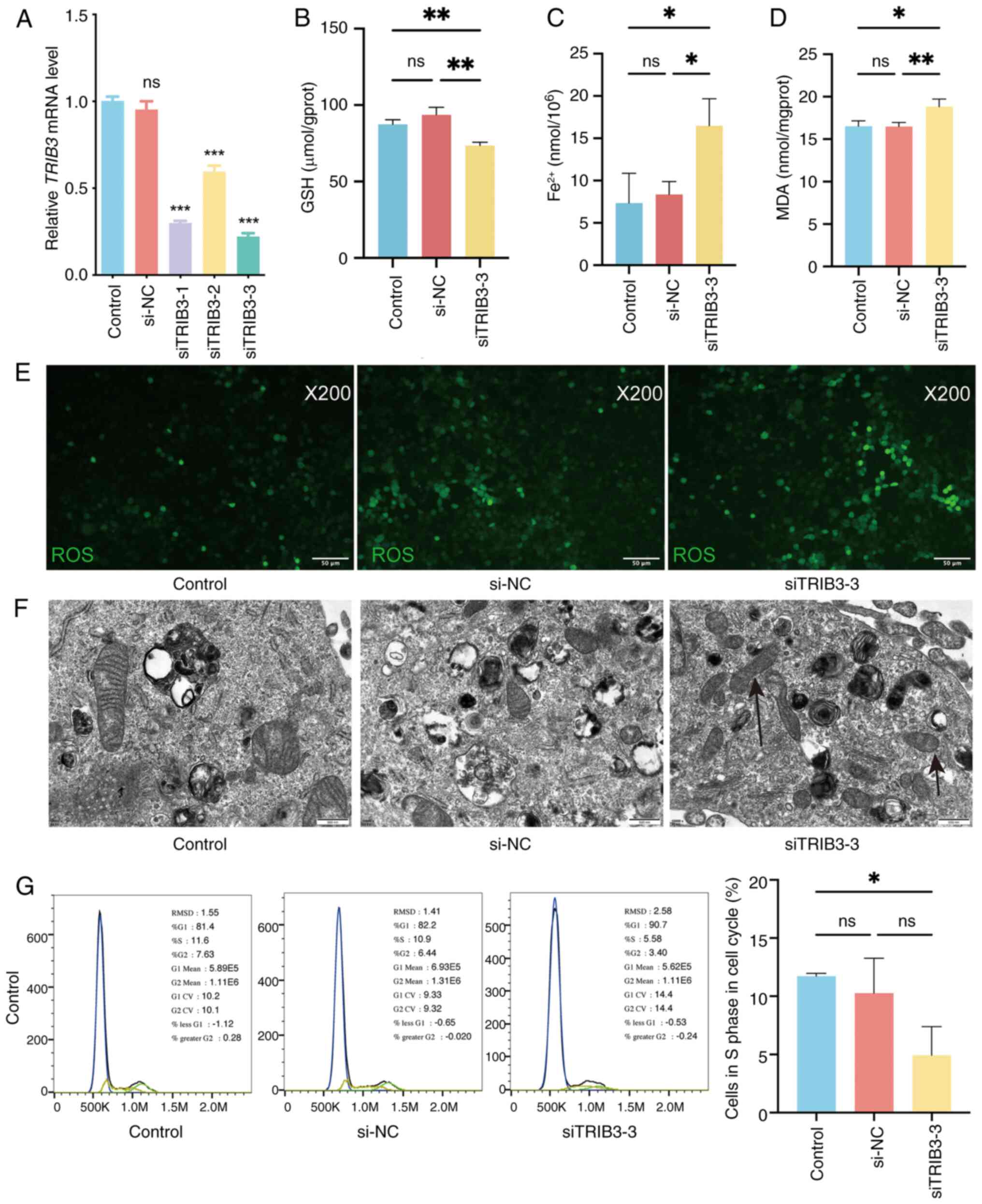

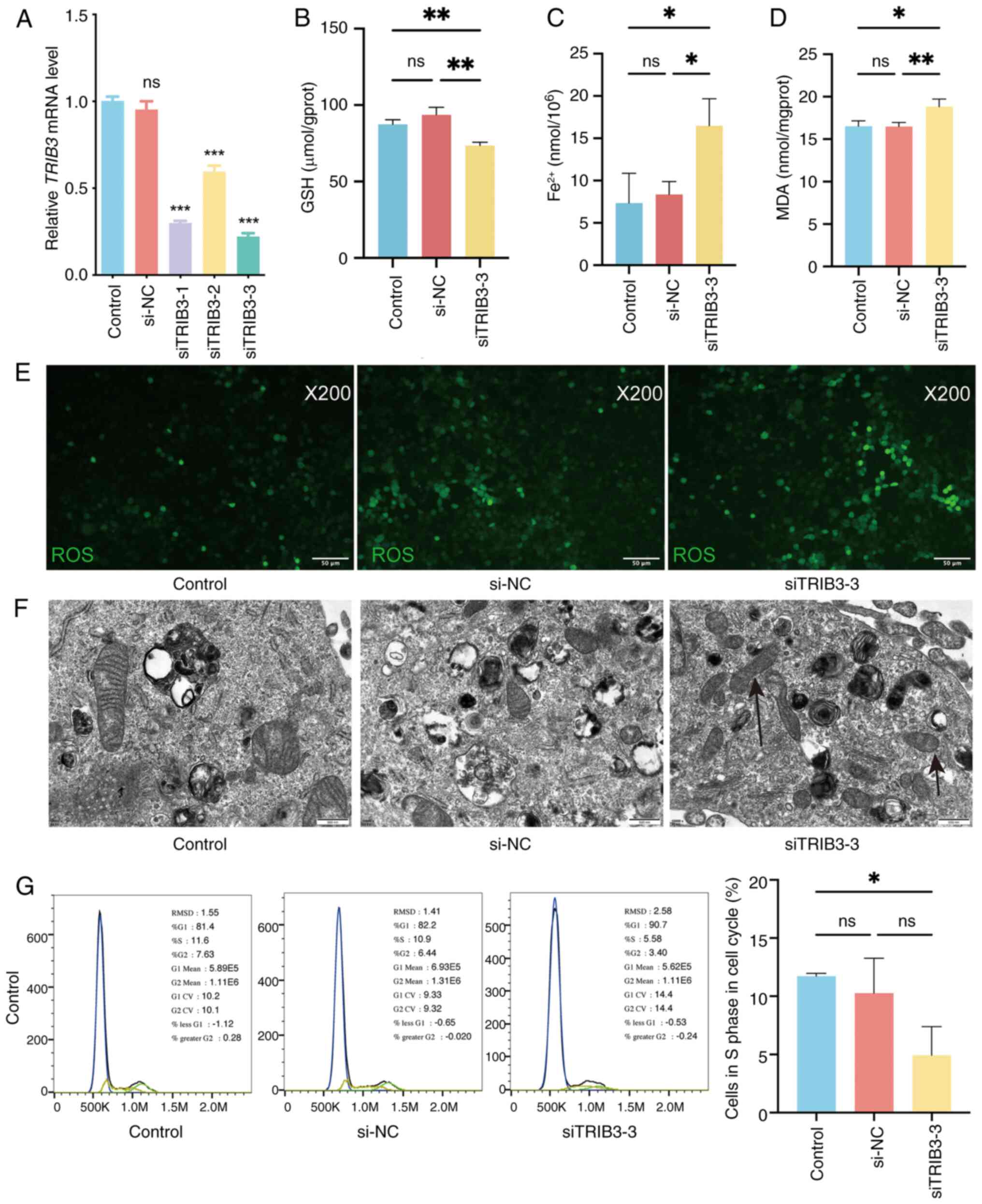

TRIB3 knockdown induces ferroptosis in

HPV-negative HNSCC cells

To determine whether TRIB3 mediated

ferroptosis in HPV-negative HNSCC cells, TRIB3 was knocked

down in CAL27 cells using three different siRNA sequences. RT-qPCR

revealed that TRIB3 mRNA expression significantly decreased

after TRIB3 siRNA transfection (Fig. 6A), indicating successful

TRIB3 knockdown in CAL27 cells. Transfection with

TRIB3 siRNA-3 induced the largest effect. Therefore,

TRIB3 siRNA-3 was selected for further studies. The cellular

content of Fe2+, GSH and MDA, which can reflect the

ferroptosis state, were quantified, while the level of ROS (another

indicator of ferroptosis) was visualized via imaging; these

analyses were performed to investigate whether TRIB3 inhibits

ferroptosis in HNSCC cells. Upon TRIB3 knockdown in cancer

cells (CAL27), the concentration of GSH decreased (Fig. 6B), while the concentrations of

Fe2+ and MDA increased (Fig.

6C and D). Furthermore, intracellular ROS were upregulated

after TRIB3 knockdown, indicating ferroptosis induction

(Fig. 6E). Moreover, in CAL27 cells

with siRNA, transmission electron microscopy elucidated a

discernible decrease or complete absence of mitochondrial ridges,

concomitant with elevated mitochondrial membrane density (Fig. 6F). Finally, cell cycle analysis was

performed by flow cytometry, indicating that TRIB3 knockdown

decreased the population of cells in the S phase (Fig. 6G). These findings suggest that

TRIB3 knockdown may promote ferroptosis in HPV-negative

HNSCC cells.

| Figure 6.Knockdown of TRIB3 promotes

ferroptosis in HPV-negative HNSCC cells. (A) Relative TRIB3

mRNA expression in CAL27 cells in the different groups measured by

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction after

siRNA transfection. (B) The intracellular GSH concentration was

measured using the reduced GSH Colorimetric Assay Kit. (C) The

intracellular Fe2+ concentration was measured using the

Cell Ferrous Iron Colorimetric Assay Kit. (D) The intracellular MDA

concentration was measured using the Cell Malondialdehyde

Colorimetric Assay Kit. (E) ROS (green fluorescence) were measured

in the cells. (F) Observation of the cells under transmission

electron microscopy. (G) Cell cycle distribution analysis using

flow cytometry. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ns,

non-significant; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; GSH,

glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

HPV, human papillomavirus; TRIB3, tribbles pseudokinase 3; si,

small interfering (RNA); NC, negative control. |

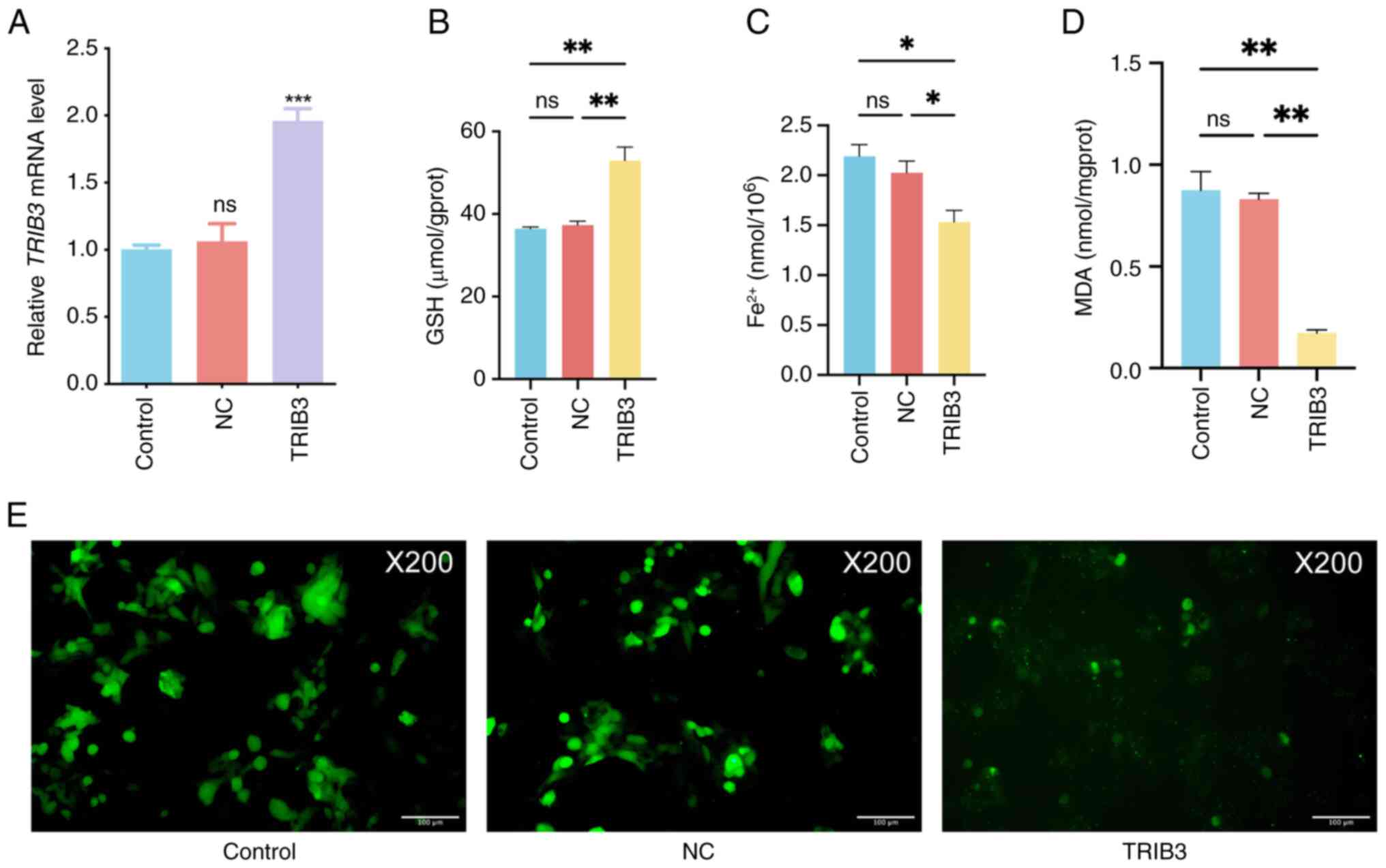

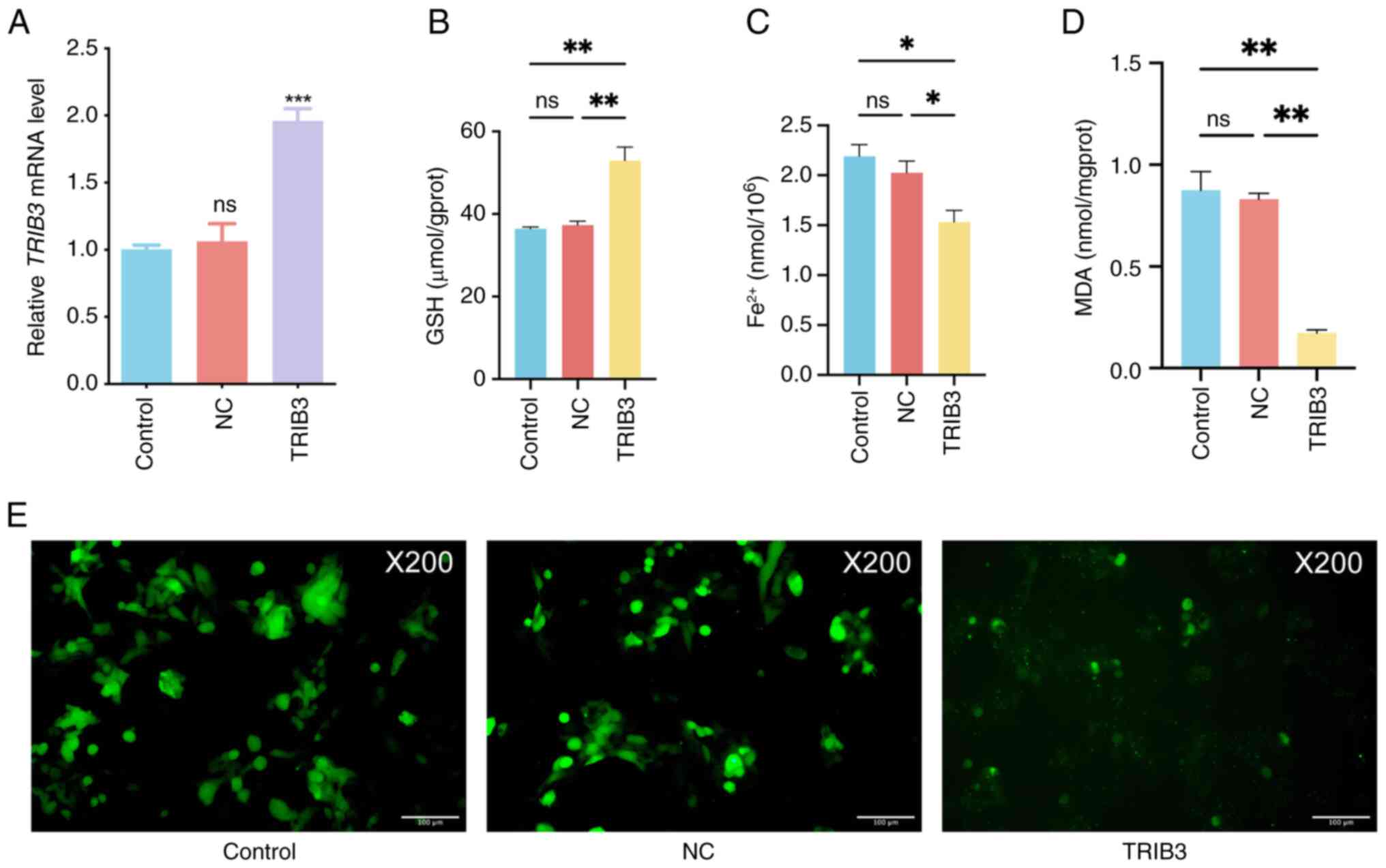

TRIB3 overexpression inhibits

ferroptosis in HPV-positive HNSCC cells

To determine whether TRIB3 mediates

ferroptosis in HPV-positive HNSCC cells, TRIB3 was

overexpressed in UPCI-SCC-090 cells. RT-qPCR revealed that

TRIB3 mRNA expression significantly increased after

TRIB3 transfection (Fig.

7A), indicating successful TRIB3 overexpression in

UPCI-SCC-090 cells. Furthermore, the concentrations of

Fe2+, GSH and MDA were quantified while the level of ROS

was visualized via imaging; these analyses were conducted to assess

the potential induction of ferroptosis by TRIB3 in HPV-positive

HNSCC cells. TRIB3 overexpression in HPV positive HNSCC cancer

cells (UPCI-SCC-090) led to an increase in the GSH concentration

(Fig. 7B), accompanied by a

decrease in the Fe2+ and MDA concentrations (Fig. 7C and D). Moreover, there was a

noticeable decline in intracellular ROS following TRIB3

overexpression, indicating ferroptosis suppression (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that TRIB3

expression may inhibit ferroptosis in HPV-positive HNSCC cells.

| Figure 7.TRIB3 overexpression inhibits

ferroptosis in HPV-positive HNSCC cells. (A) Relative TRIB3

mRNA expression in the different groups measured by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (B) The

intracellular GSH concentration was measured using the reduced GSH

Colorimetric Assay Kit. (C) The intracellular Fe2+

concentration was measured using the Cell Ferrous Iron Colorimetric

Assay Kit. (D) The intracellular MDA concentration was measured

using the Cell Malondialdehyde Colorimetric Assay Kit. (E) ROS

(green fluorescence) were measured in the cells. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ns, non-significant; HPV, human

papillomavirus; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; GSH,

glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

TRIB3, tribbles pseudokinase 3; NC, negative control. |

Discussion

Ferroptosis is a unique form of cell death (23) and a previous study demonstrated an

association between ferroptosis and HNC treatment: In murine

models, ferroptosis inducers and specific antitumor drugs, such as

cisplatin, have shown synergistic effects in suppressing the

progression of HNC (25). Although

a number of studies have compared FRGs between healthy tissues and

HNSCC tissues (31,32), the differences in FRG expression

between HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC have not yet been well

reported. However, it has been demonstrated that HPV16 integration

confers ferroptosis resistance in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

via the c-Myc/microRNA-142-5p/Homeobox A5/solute carrier family 7

member 11 axis (39). Additionally,

HPV status has been identified as a key determinant of ferroptosis

sensitivity in HNSCC, with HPV E6/E7 interfering with NFE2-like

BZIP transcription factor 2 pathways in HPV-positive cases and

HPV-negative HNSCC relying more on glutathione peroxidase

4-dependent defense (40).

Additionally, a cross-tumor analysis has confirmed distinct

ferroptosis-related metabolic signatures between HPV subtypes,

including enhanced ROS detoxification in HPV-positive HNSCC and

pro-oxidative pathways with immune suppression in HPV-negative

patients (41). Collectively, these

findings, from the mechanistic regulation of ferroptosis by HPV

oncogenes and the subtype-specific ferroptosis sensitivity mediated

by HPV status, to the distinct ferroptosis-related metabolic

profiles, provide compelling evidence that FRG expression differs

between HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC, highlighting the

necessity of stratifying HNSCC by HPV status when investigating

ferroptosis-associated mechanisms and therapeutic strategies.

In the present study, the expression of FRGs in

HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC were investigated, given the

known biological differences between these two subtypes of HNSCC,

specifically in terms of etiopathogenesis, molecular genetic

characteristics, clinicopathologic presentation and prognosis

(5). To develop a prognostic model

for the HPV-negative group, 10 FRGs were specifically identified

(ALOXE3, ACSL1, TRIB3, FLT3, EGFR, AGPAT3, AMN, PPARG,

MIR9-3HG and BNIP3) as per their efficacy in the LASSO

Cox regression analysis. According to the findings, this model

could function as a reliable prognostic indicator for patients with

HPV-negative HNSCC. Furthermore, the RT-qPCR, western blotting and

immunohistochemistry analyses performed in the present study

demonstrated that among the 10 FRGs, TRIB3 exhibited higher

expression in HPV-negative samples than in HPV-positive

samples.

TRIB3, which belongs to the Tribbles-related

family, has been found to have biological associations with a range

of cancer types including oral squamous cell carcinoma, breast

cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal

cancer and glioblastoma, and it can act as either an oncogene or a

tumor suppressor (42–47). TRIB3 is involved in various

biological processes, including lipid and glucose metabolism,

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, cell proliferation,

differentiation and the cellular stress response (46,48,49).

As lipid peroxidation and iron overload are the main metabolic

characteristics of ferroptosis (50), whether TRIB3 regulated

ferroptosis in HPV-positive and HPV-negative cells was evaluated in

the present study. It was found that TRIB3 knockdown impeded

the survival of HPV-negative HNSCC cells. Moreover, TRIB3

knockdown led to elevated intracellular Fe2+, MDA and

ROS levels, along with a decrease in GSH. Conversely, TRIB3

overexpression in HPV-positive HNSCC cells yielded contrasting

outcomes. Additionally, after TRIB3 knockdown, transmission

electron microscopy revealed a notable reduction or complete loss

of mitochondrial ridges, along with a notable increase in

mitochondrial membrane density. The downregulation of TRIB3

resulting in the occurrence of ferroptosis in HPV-negative HNSCC

cells was thus highlighted by the results of the present study.

TRIB3 may become a new target that can trigger ferroptosis

in both HPV-positive and HPV-negative cancer cells. Nevertheless,

further investigation is necessary to understand the mechanism by

which TRIB3 influences ferroptosis. Additionally, in the

present study, the Kaplan-Meier analysis and prognostic model

demonstrated that TRIB3 had a more significant clinical

impact in patients with HPV-negative HNSCC compared with

HPV-positive. Furthermore, compared with HPV-positive HNSCC cells,

TRIB3 expression is upregulated in HPV-negative HNSCC. Given the

biological disparities between these two subtypes, the upregulation

of TRIB3 is not merely a quantitative elevation, but rather a

qualitative alteration intimately linked to their distinct

oncogenic drivers and regulatory mechanisms, which implies that

multiple distinct pathways may underlie this upregulation and, in

turn, modulate ferroptosis. Finally, despite TRIB3 mediating

ferroptosis in both HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC cells, the

underlying mechanism of this effect remains unknown. Whether

TRIB3 functions through the same pathway in these two

subtypes of HNSCC requires further investigation.

Aside from TRIB3, the prognostic model

constructed in the present study included 9 other genes: EGFR,

AGPAT3, PPARG, ACSL1, BNIP3, ALOXE3, FLT3, AMN and

MIR9-3HG. EGFR, a promoter of HNSCC growth and

development, is upregulated in >90% of cases of HNSCC (51). Moreover, EGFR reduces

N6-methyladenosine and protects against ferroptosis in glioblastoma

by promoting ALKBH5 nuclear retention (52). ACSL1, which encodes an

essential enzyme involved in the modulation of lipid metabolism,

increases ferroptosis resistance and antioxidant capacity in

ovarian cancer by regulating the myristoylation of AIF family

member 2 (53). ACSL1 was also

observed to be upregulated in HPV-negative HNSCC in the present

study; however, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet

investigated the relationship between ACSL1 and HPV infection. In

addition, ALOXE3, a YAP-TEAD target gene, is associated with

YAP-induced ferroptosis and significantly increases the risk of

death induced by ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells when

overexpressed (54). PPARG,

which encodes a nuclear receptor associated with the modulation of

lipid metabolism, mediates the ferroptosis of dendritic cells,

limiting antitumor immunity in mice (55). Moreover, research on

FLT3-mediated ferroptosis is primarily focused on

FLT3-mutant leukemia (56,57).

Bioinformatics analyses have also reported that BNIP3, AMN

and MIR9-3HG are involved in ferroptosis during

carcinogenesis (58–60). However, there is currently no

research on AGPAT3 and its role in mediating ferroptosis,

making this a novel finding of the present study.

The immune system modulates the response to therapy

and inhibits tumor growth, invasion and metastasis. Immune

surveillance provides a method for identifying, controlling and

eliminating tumor cells (27–29).

Lipid mediators may be generated by ferroptotic cells as

recognition signals to recruit antigen-presenting cells and other

immune cells into the microenvironment of the ferroptosis tumor

(61). However, the relationship

between infiltrating immune cells and ferroptosis in HNSCC remains

unclear. In the present study, increased infiltrating immune cells,

such as quiescent dendritic cells, plasma cells, mast cells,

regulatory T cells and naïve B cells, were found in the low-risk

group, while the high-risk group demonstrated elevated infiltration

of neutrophils, activated CD4+ T cells and mast cells.

Moreover, a significant correlation was observed among the 10 hub

FRGs, the risk score and various immune cell types. Thus, these 10

FRGs may induce ferroptosis and thus regulate immunological

therapy, positioning them as potential new targets in patients with

HPV-negative HNSCC. However, even when the scale of the

confirmation has been estimated, CIBERSORT predictions remain

limited. This is because deconvolution of bulk RNA-sequencing data

can be noisy, an issue that is particularly pronounced in

heterogeneous tumors. Experimental verification is needed to

confirm these results, and such validation could first extend to

prospective multicenter cohorts of patients with HPV-negative HNSCC

to verify the robustness of the 10-FRG-based prognostic model

across diverse populations, addressing the current reliance on

retrospective TCGA data.

The present study has some limitations that should

be considered. First, the prognostic model was developed by

analyzing publicly available datasets. Therefore, the findings

still require verification in prospective multicenter cohorts.

Second, the in vitro validation of TRIB3, was limited to

single HPV-negative (CAL27) and HPV-positive (UPCI-SCC-090) HNSCC

cell lines, risking biological variability-related confounding

factors. These results will be followed by experiments expanding

the cell panel to additional HPV-negative (such as SCC-25 and HN6)

and HPV-positive (such as SCC-47) cell lines and incorporating

patient-derived primary cells to verify the function of TRIB3 and

reduce variability. Third, only TRIB3, one of the risk

signature genes, was evaluated in vitro. More studies are

required to evaluate the functions of EGFR, AGPAT3, PPARG,

ACSL1, BNIP3, ALOXE3, FLT3, AMN and MIR9-3HG in the

pathogenesis and development of HNSCC. Moreover, studying the

mechanisms by which the identified FRGs regulate ferroptosis is

essential for comprehending their roles and potential implications

in cellular functions and disease processes. Last, the present

study is limited by the absence of in vivo data. Given that

in vivo validation is critical to verifying the biological

function of a target gene and evaluating its clinical translation

potential, future work should prioritize investigating the function

of TRIB3 in in vivo models to confirm its utility for

clinical translation.

In conclusion, the present study identified 10 hub

genes associated with ferroptosis, including TRIB3, EGFR,

AGPAT3, PPARG, ACSL1, BNIP3, ALOXE3, FLT3, AMN and

MIR9-3HG. A prognostic model was developed for the

HPV-negative patient group using these 10 hub FRGs. Thus, these 10

FRGs may serve as prognostic markers for patients with HPV-negative

HNSCC. TRIB3 expression was higher in HPV-negative clinical

samples than in HPV-positive clinical samples. TRIB3

knockdown resulted in increased intracellular Fe2+, MDA

and ROS, reduced GSH and the diminishment or absence of

mitochondrial ridges in HPV-negative HNSCC cells. Conversely,

TRIB3 overexpression resulted in decreased intracellular

Fe2+, MDA and ROS, but increased GSH in HPV-positive

HNSCC cells. These results indicate a novel association between

TRIB3 and ferroptosis in both HPV-positive and -negative

HNSCC cells. TRIB3 had a more significant clinical impact in

the HPV-negative HNSCC group than in the HPV-positive HNSCC group,

thereby providing a direction to improve clinical outcomes for

patients with HPV-negative HNSCC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JL, NAR, SM and GY were responsible for conception.

JL and GY performed the interpretation and analysis of data. JL

prepared the manuscript. JL, NAR, SM and GY revised the manuscript

for important intellectual content. The study was supervised by GY.

JL and GY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval for this retrospective study using

de-identified data was granted by the Human Ethical Committee of

Heping Hospital Affiliated to Changzhi Medical College [Changzhi,

China; approval no. 2023(027)]. The committee also waived the

requirement for informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Reid PA, Wilson P, Li Y, Marcu LG and

Bezak E: Current understanding of cancer stem cells: Review of

their radiobiology and role in head and neck cancers. Head Neck.

39:1920–1932. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui

VWY, Bauman JE and Grandis JR: Head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 6:922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mody MD, Rocco JW, Yom SS, Haddad RI and

Saba NF: Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 398:2289–2299. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chi AC, Day TA and Neville BW: Oral cavity

and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma-an update. CA Cancer J

Clin. 65:401–421. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wuerdemann N, Wittekindt C, Sharma SJ,

Prigge ES, Reuschenbach M, Gattenlöhner S, Klussmann JP and Wagner

S: Risk factors for overall survival outcome in surgically treated

human Papillomavirus-Negative and positive patients with

oropharyngeal cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 40:320–327. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yu W, Chen Y, Putluri N, Osman A, Coarfa

C, Putluri V, Kamal AHM, Asmussen JK, Katsonis P, Myers JN, et al:

Evolution of cisplatin resistance through coordinated metabolic

reprogramming of the cellular reductive state. Br J Cancer.

128:2013–2024. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Azharuddin M, Roberg K, Dhara AK, Jain MV,

Darcy P, Hinkula J, Slater NKH and Patra HK: Dissecting multi drug

resistance in head and neck cancer cells using multicellular tumor

spheroids. Sci Rep. 9:200662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hu H, Li B, Wang J, Tan Y, Xu M, Xu W and

Lu H: New advances into cisplatin resistance in head and neck

squamous carcinoma: Mechanisms and therapeutic aspects. Biomed

Pharmacother. 163:1147782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mackenzie IC: Stem cell properties and

epithelial malignancies. Eur J Cancer. 42:1204–1212. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Norouzi A, Liaghat M, Bakhtiyari M,

Noorbakhsh Varnosfaderani SM, Zalpoor H, Nabi-Afjadi M and Molania

T: The potential role of COVID-19 in progression, chemo-resistance,

and tumor recurrence of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Oral

Oncol. 144:1064832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kang SH, Oh SY, Lee KY, Lee HJ, Kim MS,

Kwon TG, Kim JW, Lee ST, Choi SY and Hong SH: Differential effect

of cancer-associated fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles on

cisplatin resistance in oral squamous cell carcinoma via

miR-876-3p. Theranostics. 14:460–479. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Usman S, Waseem NH, Nguyen TKN, Mohsin S,

Jamal A, The MT and Waseem A: Vimentin is at the heart of

epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) mediated metastasis.

Cancers (Basel). 13:49852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gong Y, Fan Z, Luo G, Yang C, Huang Q, Fan

K, Cheng H, Jin K, Ni Q, Yu X and Liu C: The role of necroptosis in

cancer biology and therapy. Mol Cancer. 18:1002019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hsu SK, Li CY, Lin IL, Syue WJ, Chen YF,

Cheng KC, Teng YN, Lin YH, Yen CH and Chiu CC: Inflammation-related

pyroptosis, a novel programmed cell death pathway, and its

crosstalk with immune therapy in cancer treatment. Theranostics.

11:8813–8835. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu J, Kuang F, Kang R and Tang D:

Alkaliptosis: A new weapon for cancer therapy. Cancer Gene Ther.

27:267–269. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W,

Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X and Shi S: Targeting cell death pathways for

cancer therapy: Recent developments in necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, and cuproptosis research. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y and Guo R:

Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: A novel approach to reversing drug

resistance. Mol Cancer. 21:472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun

X, Kang R and Tang D: Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death

Differ. 23:369–379. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Conrad M and Pratt DA: Publisher

correction: The chemical basis of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol.

16:223–224. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis turns 10:

Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic

applications. Cell. 185:2401–2421. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xue Y, Jiang X, Wang J, Zong Y, Yuan Z,

Miao S and Mao X: Effect of regulatory cell death on the occurrence

and development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biomark

Res. 11:22023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kim EH, Shin D, Lee J, Jung AR and Roh JL:

CISD2 inhibition overcomes resistance to sulfasalazine-induced

ferroptotic cell death in head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett.

432:180–190. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Roh JL, Kim EH, Jang HJ, Park JY and Shin

D: Induction of ferroptotic cell death for overcoming cisplatin

resistance of head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 381:96–103. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ye J, Jiang X, Dong Z, Hu S and Xiao M:

Low-Concentration PTX And RSL3 inhibits tumor cell growth

synergistically by inducing ferroptosis in mutant p53

hypopharyngeal squamous carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 11:9783–9792.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dersh D, Hollý J and Yewdell JW: A few

good peptides: MHC class I-based cancer immunosurveillance and

immunoevasion. Nat Rev Immunol. 21:116–128. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mohme M, Riethdorf S and Pantel K:

Circulating and disseminated tumour Cells-mechanisms of immune

surveillance and escape. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:155–167. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zou W: Immunosuppressive networks in the

tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer.

5:263–274. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy

PD, Johnson JK, Liao P, Lang X, Kryczek I, Sell A, et al:

CD8+ T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer

immunotherapy. Nature. 569:270–274. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li C, Wang X, Qin R, Zhong Z and Sun C:

Identification of a ferroptosis gene set that mediates the

prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Front

Genet. 12:6980402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lu W, Wu Y, Huang S and Zhang D: A

Ferroptosis-related gene signature for predicting the prognosis and

drug sensitivity of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front

Genet. 12:7554862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hoadley KA, Yau C, Hinoue T, Wolf DM,

Lazar AJ, Drill E, Shen R, Taylor AM, Cherniack AD, Thorsson V, et

al: Cell-of-Origin patterns dominate the molecular classification

of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell. 173:291–304.e6.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Martens-de Kemp SR BB, Smeets S, Voorham

Q, Rustenburg F, de Boer VD, Brink A, van Wieringen WN and

Brakenhoff RH: GEO accession number [GSE83519]. NCBI(GEO) (ed.), .

2017.

|

|

35

|

Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Elkin EB and Gonen

M: Extensions to decision curve analysis, a novel method for

evaluating diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular

markers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 8:532008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ,

Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M and Alizadeh AA: Robust enumeration

of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods.

12:453–457. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Maeser D, Gruener RF and Huang RS:

oncoPredict: An R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient

drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief

Bioinform. 22:bbab2602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen XJ, Guo CH, Yang Y, Wang ZC, Liang

YY, Cai YQ, Cui XF, Fan LS and Wang W: HPV16 integration regulates

ferroptosis resistance via the c-Myc/miR-142-5p/HOXA5/SLC7A11 axis

during cervical carcinogenesis. Cell Biosci. 14:1292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang J and Gu Z: Ferroptosis in head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma: From pathogenesis to treatment. Front

Pharmacol. 15:12834652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hamid S, Khan MS, Khan MA, Muhammad N,

Singh M, Al-Shabeeb Akil AS, Bhat AA and Macha MA: Human papilloma

virus infection drives unique metabolic and immune profiles in head

and neck and cervical cancers: Implications for targeted therapies

and prognostic markers. Discov Oncol. 16:6762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Shen P, Zhang TY and Wang SY: TRIB3

promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma cell proliferation by

activating the AKT signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 21:3132021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wennemers M, Bussink J, Scheijen B,

Nagtegaal ID, van Laarhoven HW, Raleigh JA, Varia MA, Heuvel JJ,

Rouschop KM, Sweep FC and Span PN: Tribbles homolog 3 denotes a

poor prognosis in breast cancer and is involved in hypoxia

response. Breast Cancer Res. 13:R822011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhou H, Luo Y, Chen JH, Hu J, Luo YZ, Wang

W, Zeng Y and Xiao L: Knockdown of TRB3 induces apoptosis in human

lung adenocarcinoma cells through regulation of Notch 1 expression.

Mol Med Rep. 8:47–52. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hong B, Zhou J, Ma K, Zhang J, Xie H,

Zhang K, Li L, Cai L, Zhang N, Zhang Z and Gong K: TRIB3 promotes

the proliferation and invasion of renal cell carcinoma cells via

activating MAPK signaling pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 15:587–597.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Mimori K, Takatsuno Y,

Kim H, Hirose H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y and Mori M: Abnormal expression

of TRIB3 in colorectal cancer: A novel marker for prognosis. Br J

Cancer. 101:1664–1670. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Tang Z, Chen H, Zhong D, Wei W, Liu L,

Duan Q, Han B and Li G: TRIB3 facilitates glioblastoma progression

via restraining autophagy. Aging (Albany NY). 12:25020–25034. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Izrailit J, Jaiswal A, Zheng W, Moran MF

and Reedijk M: Cellular stress induces TRB3/USP9×-dependent Notch

activation in cancer. Oncogene. 36:1048–1057. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hua F, Mu R, Liu J, Xue J, Wang Z, Lin H,

Yang H, Chen X and Hu Z: TRB3 interacts with SMAD3 promoting tumor

cell migration and invasion. J Cell Sci. 124:3235–3246. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang XD, Liu ZY, Wang MS, Guo YX, Wang

XK, Luo K, Huang S and Li RF: Mechanisms and regulations of

ferroptosis. Front Immunol. 14:12694512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhu X, Zhang F, Zhang W, He J, Zhao Y and

Chen X: Prognostic role of epidermal growth factor receptor in head

and neck cancer: A meta-analysis. J Surg Oncol. 108:387–397. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Lv D, Zhong C, Dixit D, Yang K, Wu Q,

Godugu B, Prager BC, Zhao G, Wang X and Xie Q: EGFR promotes ALKBH5

nuclear retention to attenuate N6-methyladenosine and protect

against ferroptosis in glioblastoma. Mol Cell. 83:4334–4351.e7.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhang Q, Li N, Deng L, Jiang X, Zhang Y,

Lee LTO and Zhang H: ACSL1-induced ferroptosis and platinum

resistance in ovarian cancer by increasing FSP1 N-myristylation and

stability. Cell Death Discov. 9:832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Qin Y, Pei Z, Feng Z, Lin P, Wang S, Li Y,

Huo F, Wang Q, Wang Z, Chen ZN, et al: Oncogenic activation of YAP

signaling sensitizes ferroptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via

ALOXE3-mediated lipid peroxidation accumulation. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:7515932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Han L, Bai L, Qu C, Dai E, Liu J, Kang R,

Zhou D, Tang D and Zhao Y: PPARG-mediated ferroptosis in dendritic

cells limits antitumor immunity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

576:33–39. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Sabatier M, Birsen R, Lauture L, Mouche S,

Angelino P, Dehairs J, Goupille L, Boussaid I, Heiblig M, Boet E,

et al: C/EBPα confers dependence to fatty acid anabolic pathways

and vulnerability to lipid oxidative Stress-induced ferroptosis in

FLT3-Mutant leukemia. Cancer Discov. 13:1720–1747. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Cui Z, Fu Y, Yang Z, Gao Z, Feng H, Zhou

M, Zhang L and Chen C: Comprehensive analysis of a ferroptosis

pattern and associated prognostic signature in acute myeloid

leukemia. Front Pharmacol. 13:8663252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Meng J, Du H, Lu J and Wang H:

Construction and validation of a predictive nomogram for

ferroptosis-related genes in osteosarcoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

149:14227–14239. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhang J, Deng Y, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Jin X,

Xuan Y, Zhang Z and Ma X: Single-cell RNA-Seq analysis reveals

ferroptosis in the tumor microenvironment of clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 24:90922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Jiang W, Song Y, Zhong Z, Gao J and Meng

X: Ferroptosis-related long Non-Coding RNA signature contributes to

the prediction of prognosis outcomes in head and neck squamous cell

carcinomas. Front Genet. 12:7858392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Friedmann Angeli JP, Krysko DV and Conrad

M: Ferroptosis at the crossroads of Cancer-acquired drug resistance

and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:405–414. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|