Introduction

In the clinic, breast cancer (BC) has been commonly

characterized by the absence or presence of three key proteins:

estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor) and the growth

factor receptor HER2 (1). This

information allows clinicians to choose specific treatment options

that target these receptors. BC that lacks the expression of all

three of these proteins is termed triple-negative breast cancer

(TNBC). In the case of TNBC, the drugs developed to target these

proteins are ineffective and standard chemotherapy is employed to

treat most patients. TNBC represents 15–20% of BC cases and it is

the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer with the lowest 5-year

survival rate (2). Gene expression

profiling provides an additional method to subtype BC into five

sub-groups according to their gene transcription patterns: Luminal

A, Luminal B, HER2, basal and normal-like (3). The basal subtype has significant

overlap with the TNBC subtype and its characteristics. TNBC will

frequently respond to chemotherapy initially but subsequently grow

back more aggressive and resistant to therapy. It is also more

likely to metastasize than other subtypes. Due to this re-growth

and metastasis after initial positive response to chemotherapy,

there is a need for safe and tolerable daily maintenance therapy

that can slow or prevent this re-growth.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare type of

BC accounting for 2–6% of all breast cancer cases, however, it

accounts for 10% of all BC deaths (4,5). IBC

is primarily characterized by its clinical presentation that

includes diffuse skin thickening known as peasu d'orange

phenomenon, edema, erythema, nipple abnormalities and swelling of

the breast (6,7). These characteristics typically have a

rapid onset within a six-month period, may or may not include a

palpable lump and can be readily mistaken for infection or other

breast conditions. These distinctive visible hallmarks of IBC are

caused by tumor emboli blocking lymphatic ducts. IBC is an

extremely aggressive type of BC that has frequently metastasized by

the time of diagnosis. Although IBC clinically presents differently

than other BC subtypes, it is still evaluated and categorized into

the above subtypes (e.g., TNBC) and these biomarkers used to guide

treatment options. Thus, a case of IBC may also be subtyped as

triple-negative, referred to here as TN-IBC. TN-IBC has the lowest

survival rate within the IBC classification, compared to ER+ and

HER2+ subtypes (8). The standard of

care for IBC is neoadjuvant chemotherapy (traditional or targeted,

depending on subtype), radical mastectomy and then radiation

post-mastectomy (4,9).

While progress has been made in identifying drugs

for TNBC, e.g., PARP and immune checkpoint inhibitors, there is

still a lack of therapies specifically targeting triple-negative

forms of breast cancer. Drug repurposing is the identification of

new clinical applications for existing, Food and Drug

Administration (FDA)-approved drugs, thereby reducing the time and

financial cost associated with the traditional drug discovery

process (10). In addition, due to

already known clinical and safety data reducing the need for

extensive preclinical testing, the repurposed drug may be less

expensive for the patient and healthcare system. In the cancer

field, drug repurposing can entail either the repurposing of cancer

drugs approved for a different type of cancer or the use of

non-oncology drugs (NODs). NODs are FDA-approved (or other

agencies) drugs that were originally approved for indications other

than cancer. Many NODs have been discovered to have activity

against specific cancers in vitro and in vivo

(10). These NODs hold the

potential to be less toxic than standard chemotherapy. These unique

NODs may be administered simultaneously with chemotherapy to

enhance efficacy or reduce the dose of the more toxic

chemotherapies.

We propose additional use of NODs with anti-cancer

activity. New therapies are needed to reduce the risk of relapses

and slow cancer re-growth/metastasis in the interval after standard

treatments have completed-thus providing constant therapy to the

patient. We propose that tolerable, low toxicity NODs with

anticancer activity may serve as maintenance therapy that could be

taken on a regular basis for the interval between standard of care

treatments or after they are completed. This maintenance therapy is

envisioned to reduce the risk of recurrence or slow cancer

re-growth and metastasis, attenuating disease progression in the

interval between standard of care treatments. NODs are especially

well suited for this purpose due to their much better safety and

tolerability profiles that may allow daily dosing, unlike toxic

chemotherapy agents.

In this report, we sought to identify NODs with

activity against TN-IBC and TNBC. We employed the SUM-149 cell line

grown in spheroid culture as a model assay for TN-IBC. We used this

assay to screen a collection of NODs identified and curated from a

published database based on the screen of drugs against standard

TNBC cell lines (among others), but not IBC cell lines. In

parallel, we also tested a subset of these NODs against other TNBC

cell lines grown in two-dimension (2-D) culture. We identified 15

NODs with activity against SUM-149. Eight of these were also tested

against a panel of TNBC cell lines grown in spheroid culture to

assess breadth of activity. Several drugs, including eltrombopag

and papaverine, may have potential for repurposing for these

aggressive cancers.

Materials and methods

Materials

Plasticware and general reagents, including dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO), were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Cell

culture media and supplements were obtained from ThermoFisher and

Hyclone (GE Healthcare). CellTox Green stock solution and the

CellTiter Glo (CTG) 2.0 cell viability reagent were purchased from

Promega. Paclitaxel and cycloheximide were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. The drugs were purchased from

SelleckChem with a stated purity of ≥97%. D300 Digital Dispenser

and T4 and T8 cassettes were purchased from Tecan.

Cell culture

The cell lines MDA-MB-231, HCC-1806 and Hs578T were

obtained from American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC). MDA-MB-231

and Hs578T were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS) and Hs578T media was further supplemented with 0.01

mg/ml insulin. HCC-1806 were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS.

SUM-149 and SUM-159 were obtained from BioIVT. These cell lines

were grown in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 5% FBS, 5

µg/ml insulin, 20 ng/ml EGF and 1 µg/ml hydrocortisone. The media

for all the cell lines were further supplemented with 2.5 mM

L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin. The

cells were grown in tissue-culture treated flasks in a humidified

incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 and cells were harvested

for assays with trypsin-EDTA (Versene). Cell lines were tested

periodically for mycoplasma using the MycoAlert kit (Lonza, Basel,

Switzerland) and they tested negative for mycoplasma. The cell

lines were obtained directly from the vendors which authenticated

the cell lines. ATCC uses STR profiling to authenticate their cell

lines. All cell lines were amplified and stored frozen within 2–3

passages from original cells provided by the vendor. Experiments

were performed with cells that were less than twenty passages from

the vendor supplied cells.

Spheroid growth and cytotoxicity

assays

For the initial single concentration screening of

the 48 drugs with SUM-149, we used a combination of real time

imaging using a real-time microscopic imaging instrument (Incucyte

S3, Sartorius) to monitor spheroid area and fluorescence from the

CellTox Green cytotoxicity dye and subsequently, CTG was employed

to detect viable cells by ATP detection. The cell lines were

harvested, counted with a Vi-Cell XR Cell Viability Analyzer

(Beckman Coulter) and then plated in 96-well plates (Sbio, Catalog

# MS-9096UZ) at 5,000 cells/well in 100 µl/well complete growth

media. The plate was centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 min and then put

in the incubator for 72 h for spheroid formation. Subsequently, the

drugs and dye were added the same day. CellTox Green dye was added

to all wells at 1:1,000 final dilution (100 nl) of the stock

solution using the D300 Digital Dispenser with T8 cassettes.

Immediately after dye addition, the D300 was used to directly

deliver compounds dissolved in DMSO or DMSO only (for solvent

control wells) to create single point tests or 8-point half-log

serial dilutions (for follow up concentration response assays). The

D300 was employed to adjust DMSO in all wells to the same final

DMSO concentration of 0.1% with T8 or T4 cassettes following the

manufacturer's protocol for the instrument. Subsequently, the assay

plates were put into the imaging instrument and monitored every 4

or 6 h. After 96 h, 50 or 100 µl of CTG was added to the wells,

plate shaken 5 min and then incubated at room temp for 30 min

covered by aluminum foil to protect from light before luminescence

detected by Pherastar (BMG) or GloMax Explorer (Promega) plate

readers. The Incucyte Spheroid (Sartorius) software module was used

to determine spheroid area by phase contrast and total green

fluorescence of the well. The initial measurement for spheroid area

(0 h) was subtracted from the final measurement for each well (96

h) to determine change in area of the spheroid for each well. This

change in area reflects spheroid growth during the assay, while the

total fluorescence reflected a change in accessible DNA which

reflects cytotoxicity. Time 0 fluorescence values were used to

check for autofluorescence of the compound that may be the source

of higher fluorescence. Change in area of each well (spheroid) was

normalized to the mean of the change in area of the DMSO only wells

(used as 100% growth) to obtain percent of control which reflected

growth of spheroid. Total fluorescence was normalized to ‘no cells’

(media only) wells and DMSO wells. Thus, values >100%

represented cytotoxicity. Similarly, luminescence from the CTG part

of the assay was normalized using the mean of ‘no cells’ wells (0%

viability) and DMSO control wells (100% viability). Known cytotoxic

drug paclitaxel (0.1 µM) and cycloheximide (10 µM; primarily an

inhibitor of cell proliferation) were used as controls to confirm

detection of cell death and inhibition of cell proliferation,

respectively. The CTG single concentration data was assessed for

statistical significance using unpaired t-test to identify active

hits, defined as significantly (P<0.05) less than 100% of

control.

For subsequent assays to calculate the concentration

of drug that produced 50% growth inhibition (GI50), only

the CTG assay was performed as above. To establish the signal

representing no cell proliferation, a zero-day control plate was

used where it was plated along with other plates and at the time of

drug treatment, this plate was developed with CTG. The mean of this

zero-day control plate was subtracted from each well and then this

value normalized to the mean of no cells and DMSO control wells to

calculate cell proliferation as a percentage of control. The

GI50 values were calculated from the normalized cell

proliferation data (as a percentage of control) vs. drug

concentration graphs using a four-parameter non-linear regression

curve fit with the bottom of the curve fixed to 0% (representing no

proliferation) using Prism (Graphpad) graphing software. Values

below zero represented cytotoxicity.

2-D cell proliferation screening and

GI50 assays

For the initial screening of the drugs in 2-D, we

employed the Incucyte imager to monitor cell confluency in a

96-well format. The harvested cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well

(90 µl) in a 96-well plate (Corning plate #3603) and incubated in

the biosafety cabinet for 45 min at room temperature before

transferring to an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2

atmosphere. After 24 h, cells were treated manually with compounds

diluted into growth media (10 µl) in duplicate wells and incubated

in the Incucyte imager for 72 h. The final DMSO in compound treated

wells was 0.1% and DMSO was used at 0.1% final concentration for

maximum signal control wells. Paclitaxel (0.1 µM) and cycloheximide

(10 µM) were used as positive controls. The relative cell growth

(increase in confluency) for every well was calculated by first

subtracting the confluency data obtained from the first Incucyte

read (0 h, representing initial cell area) from the final 72 h read

(72 h read-0 h read) to get a net confluency change for every well.

This net confluency of every well was then divided by the mean net

confluency of the DMSO control well then multiplied by 100 to get

relative cell proliferation. This data was plotted using GraphPad

Prism and assessed for statistical significance using unpaired

t-test to identify active hits, defined as significantly

(P<0.05) less than 100% of control and having a mean of at least

20% inhibition. For subsequent GI50 and cytotoxicity

assays, we employed the CellTox Green dye to also measure

cytotoxicity along with proliferation in a 384-well format. Hs578T,

MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 cells were seeded at 2,000, 1,500 and 600

cells/well (50 µl/well), respectively, in 384-well plates (Corning,

plate # 3764). The cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and 5%

CO2 and then treated with compound using a D300 digital

dispenser as triplicates for each compound concentration using an

8-point half-log or two-fold serial dilution scheme starting with

10 µM as the highest concentration. DMSO-only wells were used as a

solvent control representing maximal cell proliferation. All wells

were adjusted to a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO using the D300.

To measure cytotoxic activity, 50 nl of the DNA-binding fluorescent

dye CellTox Green stock solution was added to each well immediately

after compound addition, resulting in a 1:1,000 dilution from the

stock solution provided by the manufacturer. Cells were incubated

and monitored for 96 h in the Incucyte as above. To obtain relative

cell growth, the confluency data was analyzed by subtracting the

initial confluency from the 72 h confluency (72-0 h reads) to get

net confluency for each well and then normalizing to the mean net

confluency of the DMSO control wells using the same method as

above. The GI50 values were calculated as above where

the bottom was fixed to zero (representing no change in

confluency/growth). Relative cytotoxicity values were separately

calculated using a published method (11) where the percent green fluorescence

confluency values (area of green fluorescence) were divided by the

total brightfield confluency (area of cell monolayer), multiplied

by 100, where these values were generated by the Incucyte

software.

Statistical analysis

In all cases where statistical analysis was

performed, an unpaired t-test was employed with n=4 or 6 data

points aggregated from replicate experiments where the comparison

is between drug treated wells and control wells. An alpha level of

0.05 was used. Error bars on all graphs and variability (±)

provided with values represent standard deviation (SD).

Results

NOD screening approach

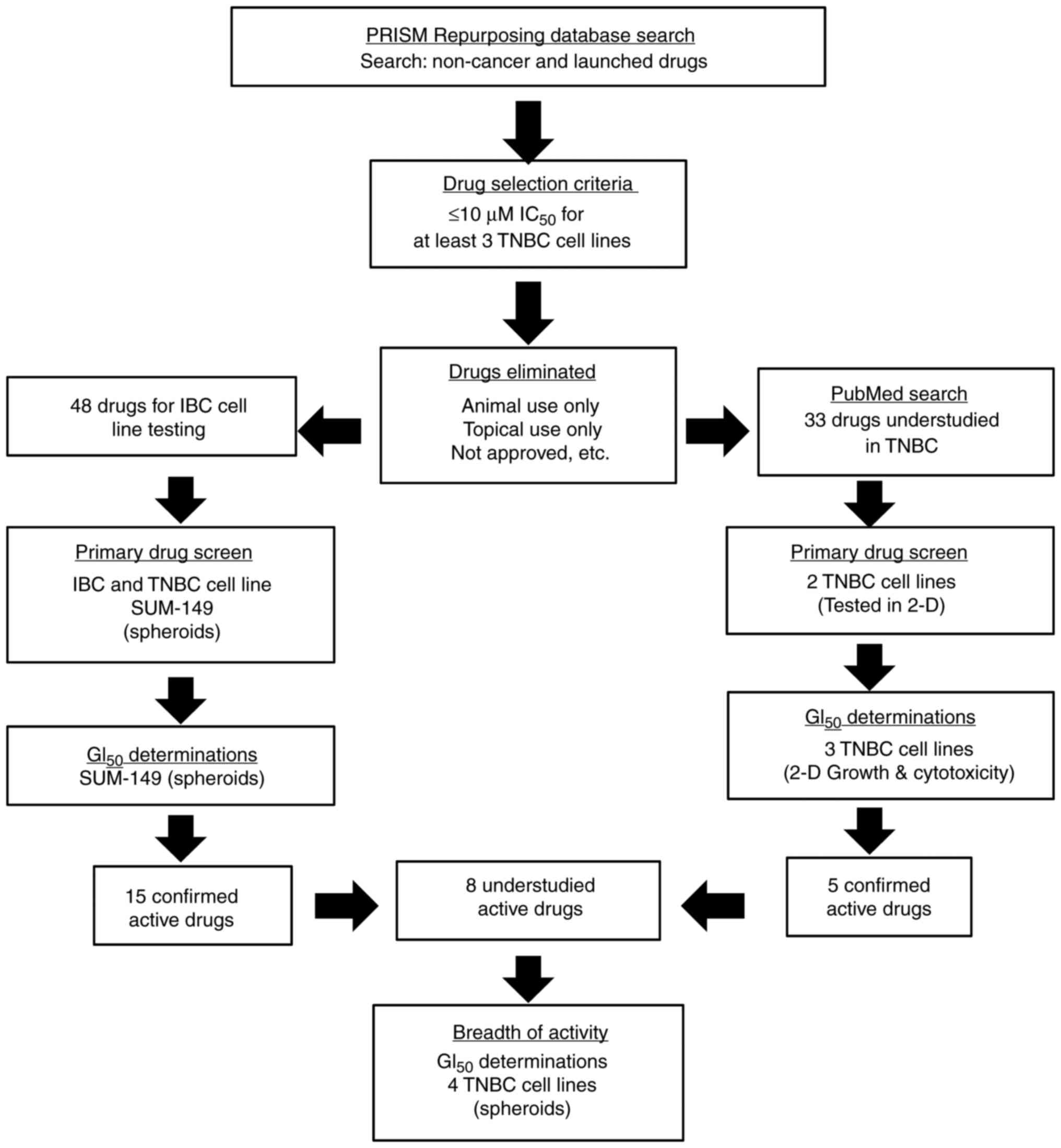

We sought to identify NODs with the potential to be

repurposed for TN-IBC, and TNBC in general as maintenance therapy.

As a first step towards this goal, we utilized the high throughput

screening data from Corsello et al (12) that is publicly available in the

PRISM database (https://depmap.org/repurposing). This group screened a

large collection of compounds and drugs using 578 different cancer

cell lines by testing drugs against multiple pools of 25

DNA-encoded cell lines mixed in a well in a highly multiplexed cell

viability/proliferation assay. We queried this database to obtain

all the activity data for non-cancer drugs and approved drugs

(Fig. 1). Further selection was

applied to those NODs with measurable IC50 values (≤10

µM) and with activity in at least three TNBC cell lines, as there

were no IBC cell lines in the original screen. These criteria

resulted in 100 candidate compounds. From this list, we eliminated

actives that were not applicable for direct drug repurposing since

they would require steps similar to de novo drug discovery, were

redundant or otherwise not of practical use (Fig. 1). Thus, drugs were eliminated that

were approved for topical use only, not genuinely approved drugs,

highly similar to cancer drugs, prodrugs of other drugs on the

list, controlled access drugs and those approved only for animal

use. We also chose just one member of highly selective drug classes

such as HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins). After this further

selection process, 48 drugs (Fig.

2) remained on our list and were sourced from vendors for

testing in our assays.

We screened these 48 NODs for cytotoxic and

anti-proliferative activity against the TN-IBC cell line SUM-149

grown as spheroids. In parallel, we also queried PubMed with the 48

NODs to identify those that have been understudied for TNBC, i.e.,

≤1 publication using the terms TNBC and the drug name. The

resulting 33 drugs were then screened for activity using two TNBC

cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159, grown in standard 2-D culture.

The 2-D assay was a more rapid screening method enabling the

initial screening using two different TNBC cell lines. Since the

resultant 2-D data cannot necessarily be directly compared to

spheroid data, the hits of highest interest in the 2-D assays were

re-tested in spheroid assays as well. Confirmed actives from the

SUM-149 and TNBC screens that were also identified as understudied

in IBC or TNBC were tested against a panel of TNBC cells grown as

spheroids to determine the breadth of activity. Representative

images of spheroids for each cell line at treatment time support

spheroid integrity (Fig. S1).

Prior to treatment, control wells were assessed for viability using

CTG and this value was also used to calculate cell proliferation as

a percentage of controls.

Initial screens for activity in NOD

collection

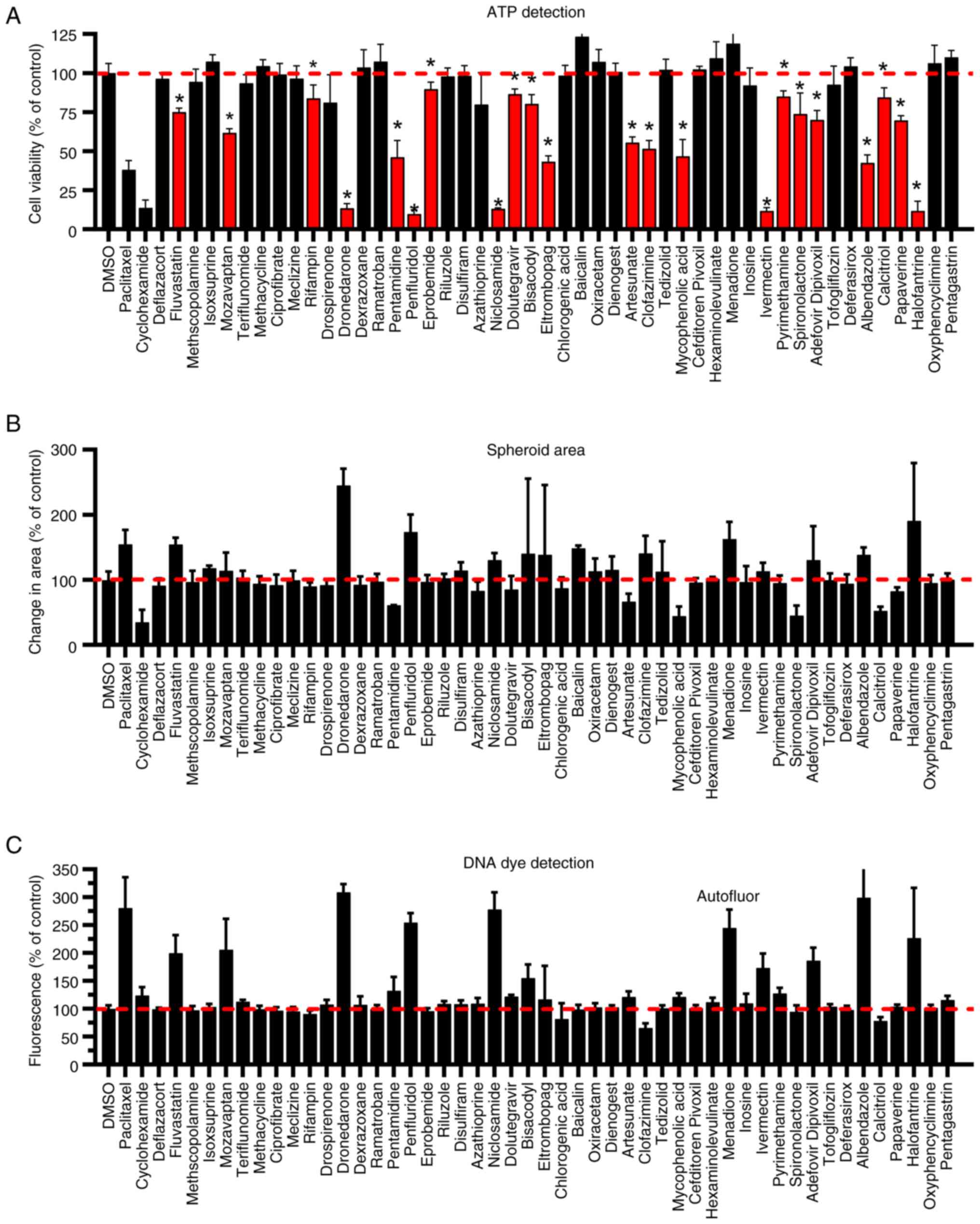

We screened the collection of 48 NODs at 10 µM drug

concentration using the SUM-149 spheroid growth assay in which we

measured three parameters as indicators of drug activity (Fig. 2). During the 96 h of drug exposure,

we monitored the spheroids with the Incucyte imaging system. After

the final reading in the Incucyte imager, we measured total cell

viability via ATP detection (CellTiter Glo) (Fig. 2A). We also determined the change in

area of the spheroid (Fig. 2B) and

cytotoxicity using CellTox Green dye (Fig. 2C) using the Incucyte software. This

dye is non-permeant to cells unless the membrane is compromised,

upon which the dye binds DNA and its fluorescence increases.

Therefore, higher fluorescence indicates cell death. The area of

the spheroid was decreased by some drugs and increased by other

drugs. An increase in size can be due to cytotoxicity resulting in

decreased cell-cell cohesion, reversing a tightly compacted

spheroid, resulting in increased total area of the spheroid

(13). This phenomenon was observed

with the known cytotoxic agent paclitaxel, used as a control in

this assay. Paclitaxel generated a mean of 155% change in area

compared to control, increased fluorescence and reduced signal in

the ATP assay, all consistent with a cytotoxic compound. A decrease

in size can be due to decreased cell proliferation during the 96 h

assay. For example, this was observed with cycloheximide, a

predominately anti-proliferative agent, which decreased mean area,

only slightly increased fluorescence and decreased ATP signal.

Based on the data, both types of spheroid area changes were

observed in this set of compounds. Of the 12 drugs that increased

the change in area by ≥125% of control, 9 also displayed an

increase in fluorescence in the CellTox Green assay, excluding

menadione which displayed autofluorescence and therefore unknown

cytotoxicity by this method. Baicalin and menadione, two of the

drugs that increased change in area but not fluorescence (baicalin)

or were autofluorescent (menadione), also increased the ATP content

over DMSO (solvent) control. Thus, these drugs appear to have

enhanced proliferation in this cell line. Clofazimine increased the

change in area relative to control, but showed no increase in

fluorescence, yet clearly inhibited cell proliferation/viability in

the ATP content assay. One drug, ivermectin, had no significant

effect on the spheroid area, but increased fluorescence and

dramatically decreased signal in the ATP assay. If area alone was

used in the screen, this drug would have been a false negative and

not detected. Thus, use of area alone may result in false positives

and false negatives when screening drugs for anti-cancer activity.

In another case, niclosamide increased the change in area by a mean

of 130%, while the signal in the ATP assay was inhibited by 87%,

the latter representing a more robust assay response. In the

cytotoxicity assay, 11 drugs (excluding menadione) produced

fluorescence >125% of control (DMSO). All these drugs were

present as a subset of the ATP assay hits. However, some drugs,

e.g., papaverine and spironolactone, were also detected with

activity in the ATP assay that showed no increase in fluorescence

suggesting they may be only anti-proliferative. Due to the lack of

specificity and sensitivity of the area measurement, the robustness

of the ATP assay and our interest in identifying both cytotoxic and

purely anti-proliferative drugs, the ATP detection assay was used

as the primary indicator of activity. Using the ATP assay, we

identified drugs that produced a signal significantly lower than

control (P<0.05) resulting in 22 drugs from this initial screen

(Fig. 2A) being selected for

confirmatory dose response studies.

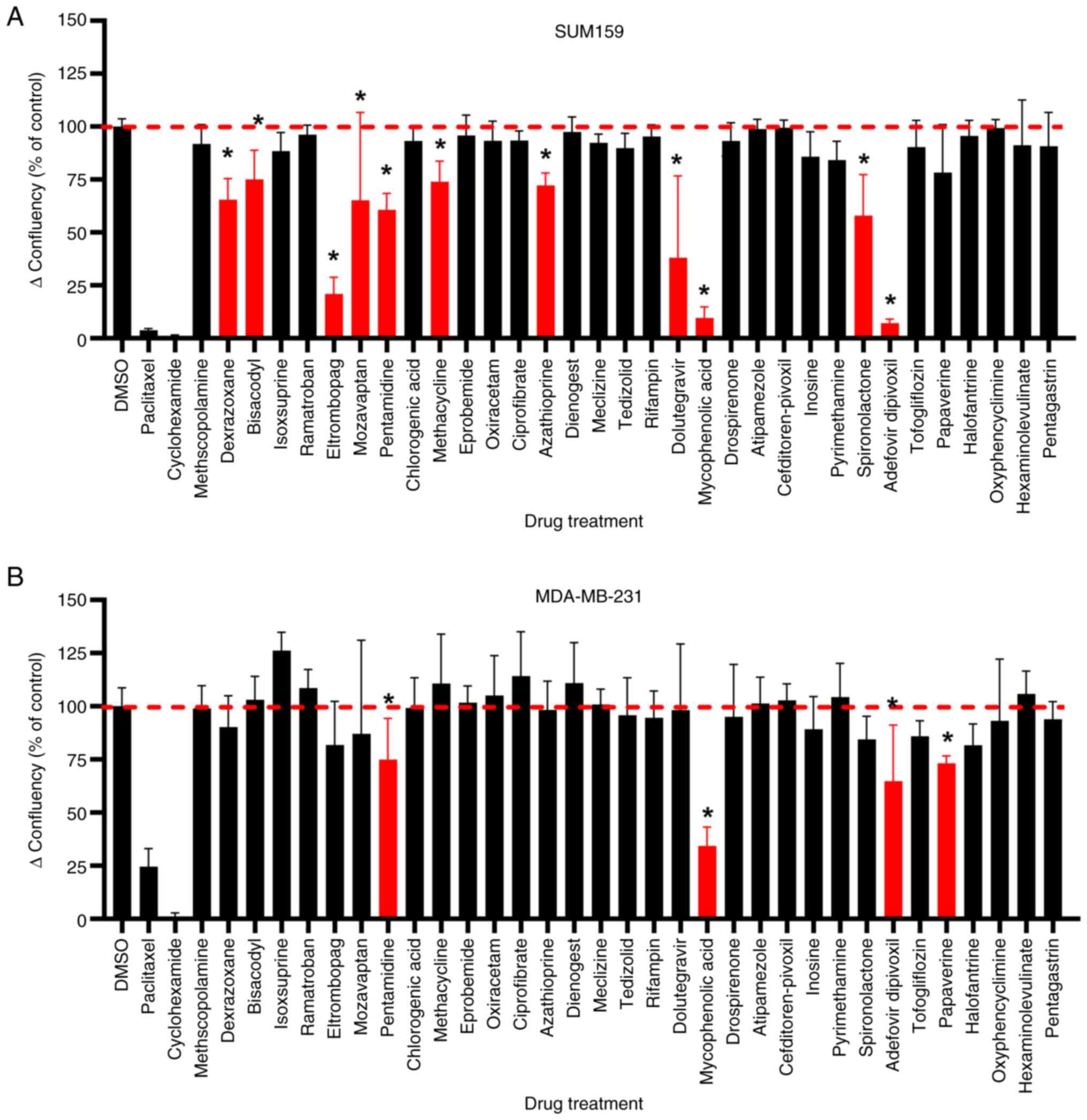

In a parallel study, we assessed a subset of 33

drugs (those from the set of 48 drugs with few literature

references) for their activity against non-IBC TNBC cell lines

SUM-159 and MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 3). A

standard 2-D cell culture model was employed, measuring change in

percent confluency as a measure of cell growth during the assay

using the Incucyte imaging system. The initial confluency at the

time of drug treatment (10 µM) was subtracted from the final

confluency to get an actual measure of cell proliferation

inhibition. Since there were too many drugs with p≤0.05 that had

minimal % inhibition (<10% inhibition) in the 2-D screen, we

added a percent inhibition cut-off to the 2-D screen hit criteria.

In this screen, 10 actives for SUM-159 and 4 actives for MDA-MB-231

were identified using a cut-off of ≥25% inhibition with P≤0.05

compared to DMSO control (Fig. 3).

One drug, mozavaptan, that showed unusually high variability in

activity against SUM-159, was also re-tested in potency assays. Due

to the inclusion of mozavaptan and significant overlap in actives,

the screen resulted in 12 unique drugs selected for confirmation

assays.

Confirmation concentration response

assays

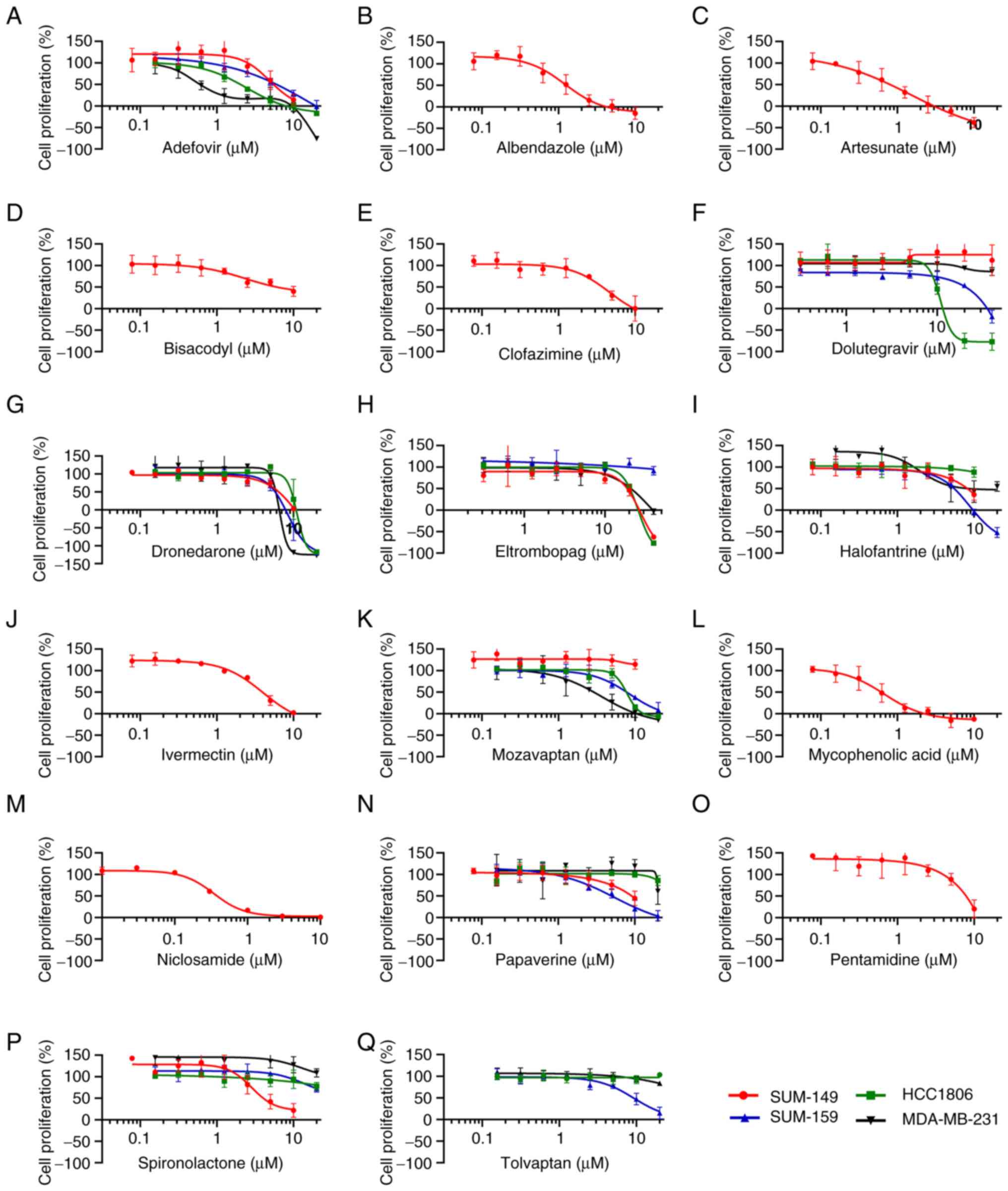

The active drugs from the SUM-149 spheroid screen

were tested in concentration response assays using the same format,

except that only the ATP assay was used as a measure of cell

viability and proliferation. An initial measure of luminescence

(‘day 0’ signal) allowed for subtraction of the signal derived from

plated cells and therefore, enabled the plotting of spheroid growth

relative to controls to derive a GI50. Thus, this method

allowed detection of both cytostasis and cytotoxicity since the

normalized 0 signal represents no cell growth and negative values

indicate cytotoxicity. GI50 was determined, rather than

simple IC50, since our interest was to identify

potential maintenance therapy, including drugs that only slowed

re-growth of cancer cells after standard of care treatment. Since

NODs were not originally designed as cytotoxic chemotherapy agents,

the expectation was that at clinical doses, many of these NODs may

only inhibit cell growth. Thus, NODs that are purely

anti-proliferative would still be of interest and we wanted to

accurately quantify this anti-proliferative activity. 15 drugs had

calculable GI50 values (reached at least 50% inhibition)

(Fig. 4 and Table I). The GI50 values ranged

from 0.17 to 14 µM and originated from various drug classes and

approved indications (Table I). At

the higher potency end of this collection of drugs (<2 µM

GI50), the anti-cancer activity of niclosamide

(GI50=0.17 µM), mycophenolic acid (GI50=0.51

µM), artesunate (GI50=0.69) and albendazole

(GI50=1.4 µM) have all been extensively described

(14). In addition to TNBC,

niclosamide has also been shown by others to have activity against

SUM-149 (15–17). While the activity of artesunate and

albendazole has been described for TNBC cell lines (18–21),

their activity against SUM-149 (or other IBC cell lines) does not

appear to have been previously reported.

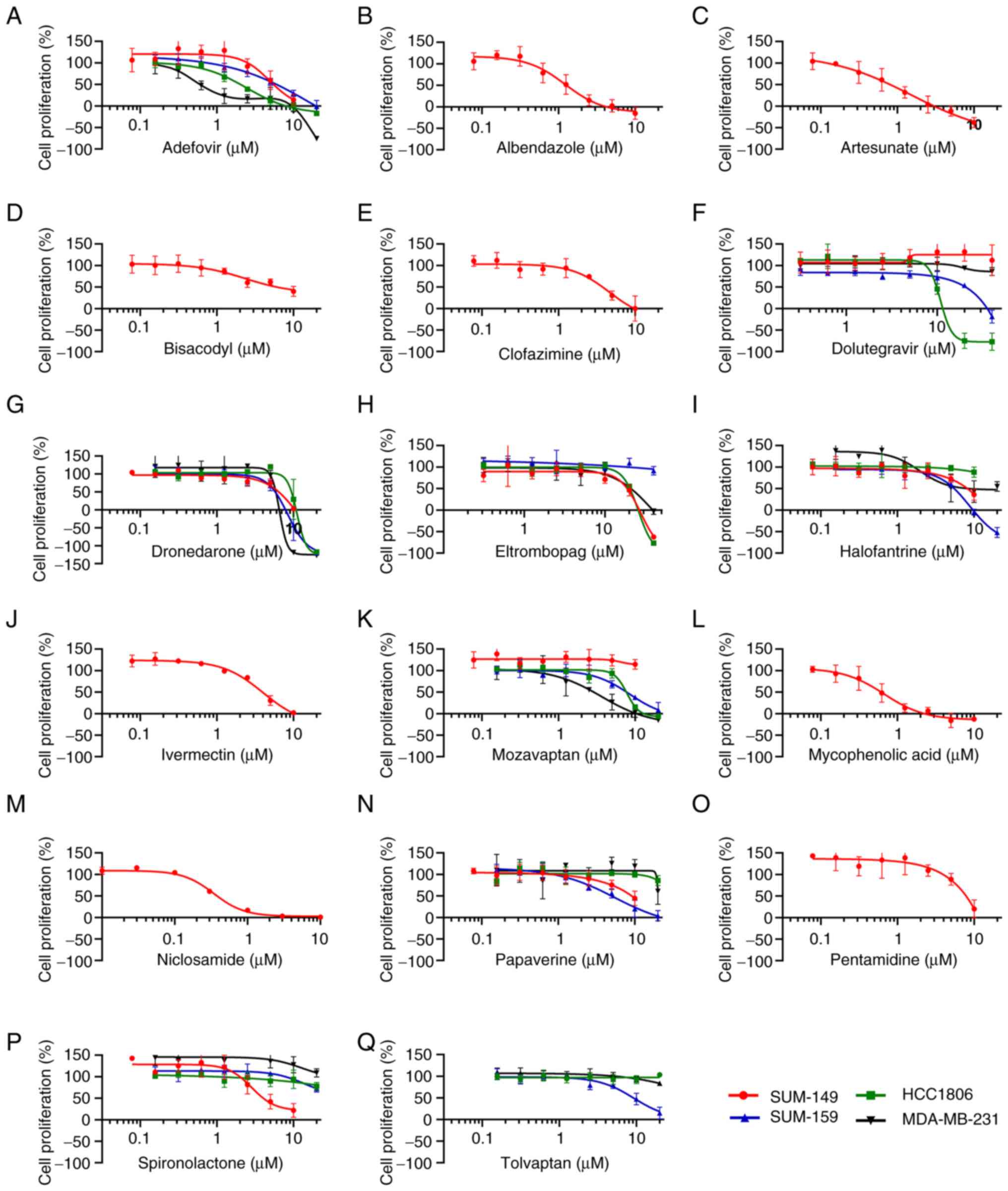

| Figure 4.GI50 determinations for

active drugs against SUM-149 and a panel of other TNBC cell lines

grown as spheroids. Relative cell proliferation (as a percentage of

controls) was determined in response to the indicated

concentrations of drugs tested against SUM-149. Selected compounds

were also profiled with an additional three TNBC cell lines,

SUM-159, HCC1806 and MDA-MB-231, as indicated. The concentration

response data was plotted for (A) adefovir, (B) albendazole, (C)

artesunate, (D) bisacodyl, (E) clofazimine, (F) dolutegravir, (G)

dronedarone, (H) eltrombopag, (I) halofantrine, (J) ivermectin, (K)

mozavaptan, (L) mycophenolic acid, (M) niclosamide, (N) papaverine,

(O) pentamidine, (P) spironolactone and (Q) tolvaptan. All cell

lines were grown in spheroid form for this assay with 96 h drug

treatment followed by viable cell number assessed by CellTiter Glo.

Relative cell proliferation (as opposed to total cells) was

calculated by subtracting mean 0-day plate values from all wells

and normalizing to controls such that a 0 value indicated no cell

proliferation during the course of the assay (same number of viable

cells as on day of treatment), while negative values indicated

cytotoxicity (fewer viable cells than on day of drug treatment).

Data shown are representative of n≥3 independent experiments and

the data points and error bars represent the mean ± standard

deviation of triplicate technical replicates. GI, growth

inhibition; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer. |

| Table I.GI50 values in the SUM-149

spheroid assay and pharmacological data for identified drugs. |

Table I.

GI50 values in the SUM-149

spheroid assay and pharmacological data for identified drugs.

| Drug | GI50

(µM)a | SD (µM) |

GI50:Cmax |

Cmaxb (µM) | Drug class or

MOA | Approved

indication |

|---|

|

Adefovir-dipivoxil | 4.8 | 0.2 | 18.5 | 0.26 | Nucleotide analog

reverse transcriptase inhibitor | Hepatitis B |

| Albendazole | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 5.70 | Tubulin

inhibitor | Parasitic worm

infections |

| Artesunate | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 8.00 | Generates free

radicals | Malaria |

| Bisacodyl | 6.6 | 2.7 | 26.4 | 0.25b | Stimulates

adenylate cyclase | Constipation |

| Clofazimine | 6.6 | 2.4 | 8.6 | 0.77 | Acts at bacterial

membranes | Leprosy |

| Dolutegravir | >40c | - | NA | 6.30 | Integrase

inhibitor | HIV-1 |

| Dronedarone | 5.7 | 0.6 | 19.0 | 0.30 | Multichannel

blocker | Atrial

fibrillation |

| Eltrombopag | 14.0d | 6.2 | 1.0 | 14.00 | Thrombopoietin

receptor agonist |

Thrombocytopenia |

| Halofantrine | 7.1 | 3.1 | 10.3 | 0.69 | Targets

ferritoporphyrin IX | Malaria |

| Ivermectin | 2.9 | 0.5 | 36.3 | 0.08 | Chloride ion

channels | Multiple

parasites |

| Mozavaptan | >10e | - | NA | Unk | Vasopressin

receptor antagonist |

Hyponatremiaf |

| Mycophenolic

acid | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 78.00 | IMPDH

inhibitor |

Immunosuppressant |

| Niclosamide | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.6 | 0.27 | Uncoupling of

electron transport | Tapeworm

infectionsg |

| Papaverine | 7.1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.90 | Nonxanthine PDE

inhibitor | Myocardial

infarction/angina |

| Penfluridol | 2.1 | 0.1 | 42.0 | 0.05 | Dopamine receptor

blocker |

Antipsychotich |

| Pentamidine | 6.7 | 2.1 | 10.6 | 0.63 | Unknown | Pneumocystis

pneumonia |

| Spironolactone | 3.5 | 0.1 | 10.0 | 0.35 | MR antagonist | Hypertension, heart

failure |

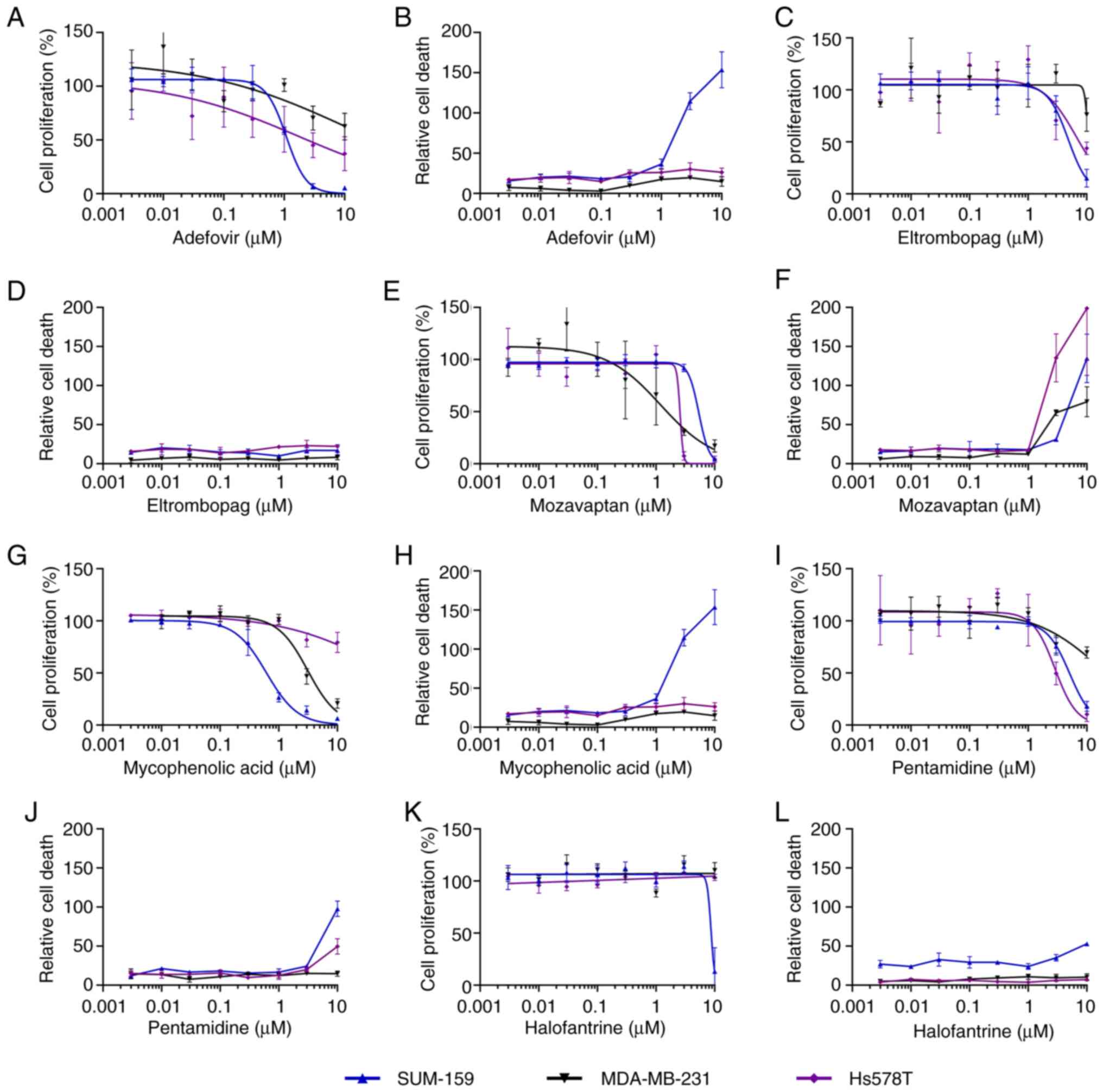

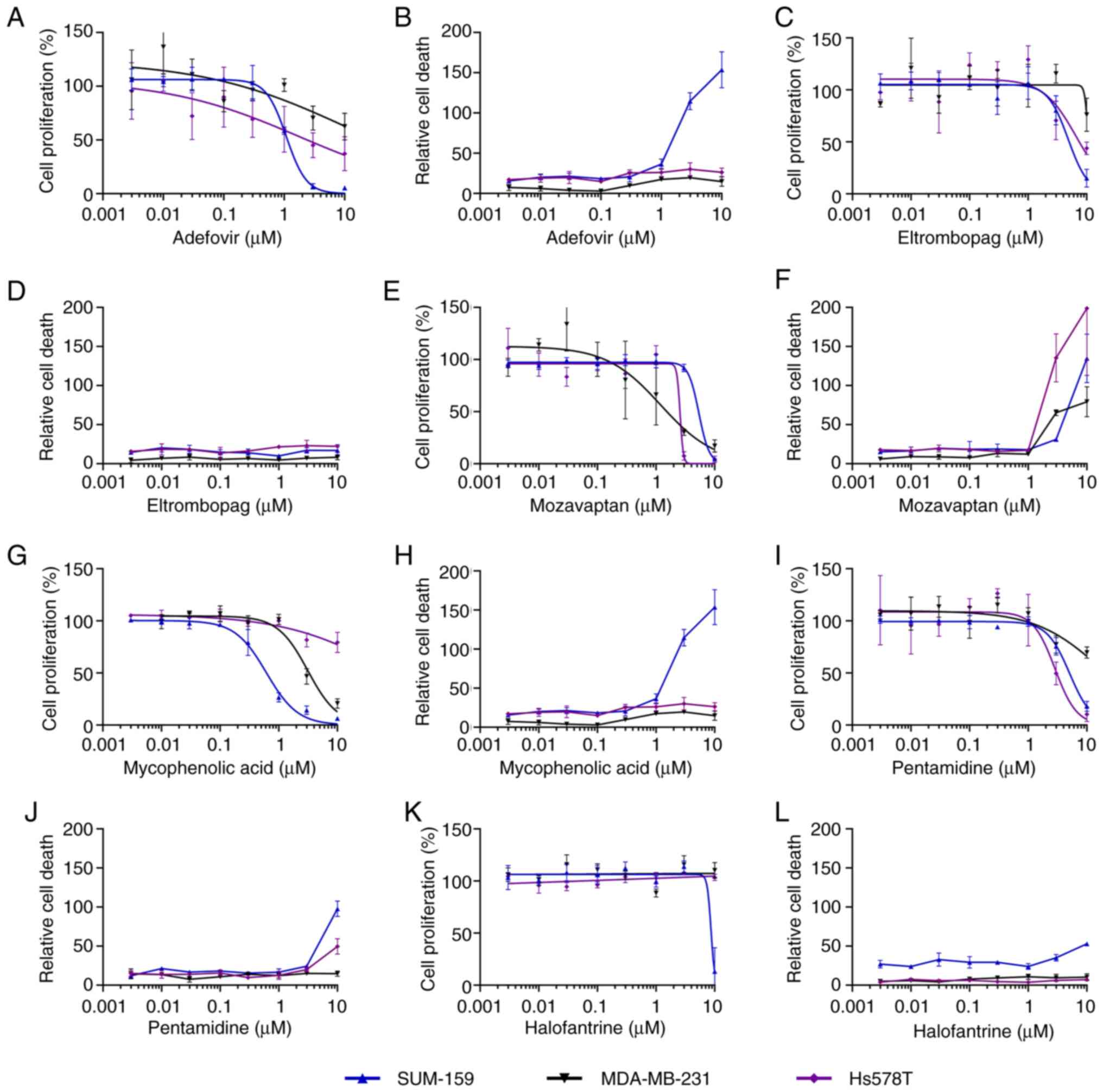

The active drugs from the TNBC 2-D screen were

tested in concentration response assays using the same format as

the initial screen, except that CellTox Green dye was used as a

measure of cytotoxicity, while confluency was used to measure cell

proliferation. All the actives were tested against three TNBC cell

lines: SUM-159, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T. Five drugs had confirmed

GI50 potencies of <10 µM for at least one cell line:

adefovir, eltrombopag, mozavaptan, mycophenolic acid and

pentamidine (Fig. 5 and Table II). Halofantrine was a sixth drug

that was also tested in this 2-D panel since it had borderline

activity against MDA-MB-231 and activity in the spheroid screen.

Mozavaptan was the only drug in this set that had activity against

all three cell lines with mean GI50 values of 2.2 to 4.6

µM. MDA-MB-231 appeared to be more drug resistant in general within

this panel than the other two cell lines since only two of these

drugs had calculatable GI50s against this cell line. The

most potent drugs were adefovir (mean GI50=1.2, 3.3 and

>10 µM) and mycophenolic acid (mean GI50=0.5, 3.1 and

>10 µM). Adefovir showed cytotoxicity only against SUM-159.

Mycophenolic acid has been extensively studied for its anti-cancer

activity, including against TNBC cell line MDA-MB-231 (22,23).

However, no studies to date have reported its activity against

SUM-149 or other IBC cell lines. A measure of cytotoxicity was

calculated by dividing the area of green fluorescence (from the

CellTox Green dye) by the area of confluency (from the brightfield

image) (Fig. 5). Mozavaptan was the

only drug that was cytotoxic against all three cell lines where it

generated cytotoxicity at concentrations above 1 µM. In contrast to

mozavaptan, the other drugs in this set that showed some

cytotoxicity only had cytotoxic activity against one cell line

(e.g. mycophenolic acid and adefovir) or weak cytotoxic activity

(only at 10 µM) against one or two cell lines (e.g. pentamidine and

halofantrine). Eltrombopag did not show cytotoxicity against any of

the cell lines and thus appeared to be purely anti-proliferative

under these 2-D conditions. Adefovir and mycophenolic acid were

only cytotoxic for SUM-159 at 3 µM and above.

| Figure 5.GI50 determination of

active drugs from 2-D screen against a panel of three TNBC cell

lines. Relative cell proliferation (as a percentage of controls)

and cytotoxicity was determined in response to the indicated

concentrations of drugs tested against SUM-159, HCC1806 and

MDA-MB-231, as indicated. All cell lines were grown in 2-D.

Immediately after drug treatment, confluency and CellTox Green dye

fluorescence (cytotoxicity) was monitored for 72 h with the

Incucyte. Relative cell proliferation was calculated by subtracting

the initial confluency (based the first read) from the final

confluency measurement for each well and normalized to controls.

Therefore, a 0% value indicates no change in confluency compared to

the start of the assay. Relative cell death after 72 h was

calculated by dividing the area of green dye fluorescence by the

total confluency area (based on brightfield imaging) and

multiplying by 100. Separate plots are provided for cell

proliferation and cytotoxicity for (A and B, respectively)

adefovir, (C and D, respectively) eltrombopag, (E and F,

respectively) mozavaptan, (G and H, respectively) mycophenolic

acid, (I and J, respectively) pentamidine and (K and L,

respectively) halofantrine. Data shown are representative of n≥3

independent experiments and the data points and error bars

represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate technical

replicates. GI, growth inhibition; TNBC, triple-negative breast

cancer; 2-D, two-dimension. |

| Table II.GI50 for drugs identified

in 2-D cell culture screen. |

Table II.

GI50 for drugs identified

in 2-D cell culture screen.

| Cell line | SUM-159 | MDA-MB-231 | Hs578T |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Drug | GI50

(µM)a | SD | GI50

(µM)a | SD | GI50

(µM)a | SD |

|---|

| Adefovir

dipivoxil | 1.2 | 0.3 | >10 | - | 3.3b | 1.5 |

| Eltrombopag | 8.1 | 1.0 | >10 | - | 5.3b | 1.3 |

| Halofantrine | 7.6 | 1.1 | >10 | - | >10 | - |

| Mozavaptan | 4.6 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| Mycophenolic

acid | 0.5 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.3 | >10 | - |

| Pentamidine | 7.4 | 1.8 | >10c | - | 2.0b | 0.9 |

Activity of understudied NODs in a

panel of TNBC cell lines

Since SUM-149 is the only commercially available

TN-IBC cell line, we were unable to test the active hits against

other TN-IBC cell lines. Therefore, we sought to test understudied

NODs from the SUM-149 screen against standard TNBC cell lines to

assess the breadth of activity. Of the 15 drugs that were confirmed

in the SUM-149 screen, 7 of them were assessed to be understudied

in TN-IBC/TNBC based on PubMed literature searches. Similarly, 5 of

the hits in the 2-D screen with TNBC cell lines had few studies

related to their activity in TNBC. We combined these sets of drugs,

resulting in 8 unique understudied drugs, due to high overlap in

the lists. Only mozavaptan was a novel hit in the 2-D screen

compared to the SUM-149 screen hits. Dolutegravir was understudied

in the literature but was highly variable in the SUM-149 potency

assays for unknown reasons, so we included it for testing against

this panel. We tested these eight drugs in concentration response

against TNBC cell lines SUM-159, HCC1806 and MDA-MB-231 grown in

the spheroid assay format with ATP detection as the measure of cell

viability and proliferation (Fig.

4, Table III and Fig. 6A). Since we performed a ‘Day 0’

plate to obtain the signal for the initial cell number at the time

of drug treatment, a negative cell proliferation value at the end

of drug treatment indicated fewer viable cells, i.e., cytotoxicity.

Hs578T failed to proliferate in the spheroid growth conditions

employed, so we used HCC1806 in its place. Eltrombopag and

dolutegravir were tested at higher max concentration (40 µM) due to

their higher Cmax values. Adefovir, an anti-hepatitis B

antiviral drug, and dronedarone, a multi-channel blocker for atrial

fibrillation, were the only drugs in this selected drug panel to

inhibit all four cell lines with a calculatable GI50

value. Adefovir produced mean GI50 values ranging from

1.3 to 4.8 µM and it appeared to be cytotoxic for MDA-MB-231 at 20

µM, but not for the other cell lines. Dronedarone produced

GI50 values in the range of 5.3 to 8.1 µM and was

cytotoxic at higher concentrations across the cell lines. Three of

the drugs had measurable GI50 values in three of the

four cell lines. These drugs and their GI50s for

SUM-149, HCC1806, SUM-159 and MDA-MB-231, respectively, included

eltrombopag (GI50=14, 16.8, >40 and 16.8 µM),

halofantrine (GI50=7.1, >20, 5.1, 10.2 µM) and

mozavaptan (GI50=>10, 6.7, 7.6, 3.3 µM). Since

mozavaptan is a vasopressin receptor antagonist, we sought to test

another member of this class, tolvaptan, for its activity (Table III, Fig. 4Q). Tolvaptan only had weak activity

against SUM-159 (GI50=12 µM) out of the three TNBC cell

lines tested. Eltrombopag was clearly cytotoxic only at 40 µM for

two (SUM149 and HCC1806) of the three sensitive cell lines.

Papaverine had activity against SUM-149 (GI50=7.1 µM)

and SUM-159 (4.2 µM), but minimal activity (GI50 >20

µM) against the other two cell lines. Dolutegravir exhibited

activity only against SUM-149 and HCC1806 and showed notable

cytotoxicity for HCC1806 at concentrations of 20 µM and above.

Spironolactone was the only drug in this subset of drugs that was

selective for SUM-149 (GI50=3.5 µM), with no activity

against the other three cell lines.

| Table III.Anti-proliferative activity of

selected drugs in a panel of cell lines grown as spheroids. |

Table III.

Anti-proliferative activity of

selected drugs in a panel of cell lines grown as spheroids.

| Cell line | SUM-149 | HCC-1806 | SUM-159 | MDA-MB-231 |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Drug | GI50

(µM)a | SD | GI50

(µM) | SD | GI50

(µM) | SD | GI50

(µM) | SD |

|---|

| Adefovir | 4.8 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Dolutegravir | >40b | - | 16.0 | 11.0 | 27 | 7.5 | >40 | - |

| Dronedarone | 5.7 | 0.6 | 8.1 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 3.9 |

| Eltrombopag | 14.0 | 6.2 | 16.8 | 5.2 | >40 | - | 16.8 | 6.1 |

| Halofantrine | 7.1 | 3.1 | >20c | - | 5.1 | 0.03 | 10.2 | 7.2 |

| Mozavaptan | >10d | - | 6.7 | 0.7 | 7.6 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 0.7 |

| Papaverine | 7.1 | 2.2 | >20c | - | 4.2 | 0.3 | >20c | - |

| Spironolactone | 3.5 | 0.05 | >20 | - | >20c | - | >20c | - |

| Tolvaptan | NT | - | >20 | - | 12.2 | 6.2 | >20 | - |

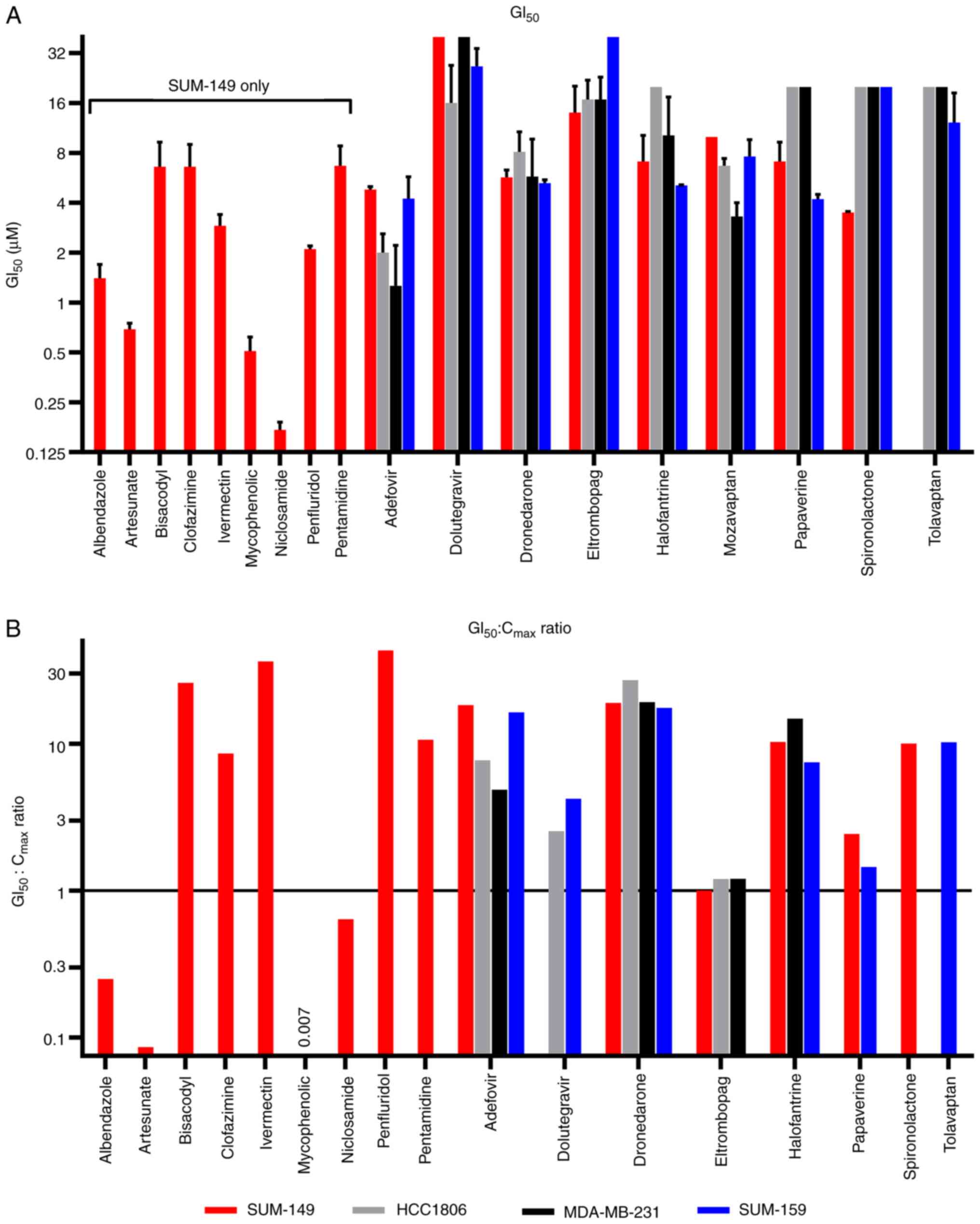

GI50 values are more informative when

viewed relative to the maximal concentration (Cmax)

achievable at clinical doses in humans. We obtained Cmax

values for the identified drugs using published Cmax

values from human clinical studies (Table I) (24–37).

By comparing the GI50 values from the SUM-149 data to

the Cmax values (Table I

and Fig. 6B), 9 drugs had

GI50 values that were 10-fold or more higher than the

Cmax (GI50:Cmax ratio of ≥10). One

drug, mozavaptan, had no published Cmax data. However,

there were 6 drugs that had GI50 values that ranged from

approximately twice their Cmax to 153-fold lower than

their Cmax. These drugs and their approximate

GI50:Cmax ratio included the following:

albendazole (GI50:Cmax=0.3), artesunate

(GI50:Cmax=0.09), mycophenolic acid

(GI50:Cmax=0.007), Niclosamide

(GI50:Cmax=0.6), eltrombopag

(GI50:Cmax=1) and papaverine

(GI50:Cmax=2). Eltrombopag and papaverine had

similar relative potencies (GI50:Cmax ratios)

for the other cell lines that were sensitive to them. Adefovir had

a Cmax of 0.2 µM and a GI50:Cmax of 18 for

SUM-149. However, in MDA-MB-231 cells, adefovir produced a

GI50 of 1.3 µM which is only 5-fold above

Cmax. Interestingly, this drug was inactive (>10 µM

GI50) in the 2-D potency assay with MDA-MB-231. This

contrasts with the results obtained with the same drug in SUM-159,

where the potency shifted almost 4-fold, indicating a less

sensitive response in the spheroid assay, suggesting a shift in

potency due to the spheroid culture conditions. It has been well

established that compound potency shifts can frequently happen when

comparing 2-D and 3-D cell culture, including many instances when

lower potency is observed in the 3-D culture (38,39).

In sum, we screened a collection of 48 NODs

identified through a published database for anti-proliferative

activity against the IBC cell line SUM-149 grown in spheroid

format. We identified 15 NODs with activity against SUM-149. A

subset of 33 NODs was also screened using two TNBC cell lines grown

in 2-D culture resulting in the identification of six drugs. There

was complete overlap in these sets of drugs, except for mozavaptan

which was only identified in the TNBC screen. In the SUM-149 assay,

the most potent drugs (<1 µM GI50) were artesunate,

mycophenolic acid, and niclosamide. Six of these drugs active

against SUM-149 (albendazole, artesunate, mycophenolic acid,

niclosamide, eltrombopag and papaverine) have potentially

clinically relevant GI50:Cmax ratios of ≤2.

Eight drugs were further tested against a panel of three non-IBC

TNBC cell lines grown in spheroid format. Selectivity varied from

two drugs (adefovir and dronedarone), which had activity against

all four cell lines, to one (spironolactone), which had activity

only against SUM-149. Eltrombopag and papaverine were identified as

having newly discovered activity against SUM-149, and we expanded

their activity profiling to multiple TNBC cell lines. In addition,

the eltrombopag and papaverine had GI50:Cmax

ratios of 1 and 2, respectively, indicating that they could reach

therapeutically relevant drug levels in vivo for anti-cancer

treatment.

Discussion

In this report, we screened a collection of NODs

based on a published database to identify NODs with activity

against TN-IBC and/or TNBC. Using the TN-IBC cell line SUM-149, we

identified 15 drugs with calculable GI50 values against

this cell line grown in spheroid form. In a parallel screening

approach, we tested a subset of these NODs for activity against two

other TNBC cell lines grown in 2-D. This second approach resulted

in a list of active drugs that overlapped with the SUM-149 hits,

except for mozavaptan which was uniquely active against SUM-149.

Rather than just using the absolute GI50 for assessing

their potential against TN-IBC, we also assessed these drugs in

terms of their potency (GI50) relative to their

Cmax reported in human studies. Many of these drugs

turned out to be well-known NODs that have many reports of their

anti-cancer activity. For example, the well-studied NODs,

albendazole (anti-parasitic), artesunate (anti-malarial),

niclosamide (for tapeworm infections) and mycophenolic acid

(immunosuppressant) have been extensively reported to have

anti-cancer activity against multiple types of cancers (10,14).

These drugs also have Cmax values in humans that are

above the GI50 reported here for SUM149 and hence may

have activity against IBC in patients. From the two screening

approaches, eight of these NODs were identified as being less

studied in TNBC, and so we tested these drugs against a panel of

other TNBC cell lines grown in spheroid format. Only two drugs

generated calculable GI50 values in all four cell lines:

adefovir (antiviral) and dronedarone (multichannel blocker for

atrial fibrillation). However, these drugs also had

GI50:Cmax ratios that were high, at

approximately 5- to 30-fold, and raises the question of how

effective they would be at clinical doses. The sensitivity to

adefovir varied between cell lines with MDA-MB-231 being the most

sensitive with a GI50 of 5-fold above Cmax.

Halofantrine (antimalarial) had activity in 3 of 4 cell lines, but

the GI50:Cmax values were all over 7-fold.

Dolutegravir (HIV drug) had activity against two cell lines (but

not SUM-149) with a GI50:Cmax of ~3-4-fold.

While this drug was reported to inhibit proliferation of BT-20, a

TNBC cell line, it was also found to increase metastasis in the 4T1

(mouse TNBC cell line) xenograft model (40). Two drugs, eltrombopag and papaverine

had GI50: Cmax ratios of 1 to 2 in sensitive

cell lines. These drugs have not been previously reported to have

activity in an IBC cell line.

A limitation of this study was the reliance on

SUM-149 as the sole TN-IBC model, since the observed drug activity

could be due to cell line-specific effects and not generalizable to

most TN-IBC. Hence, these drugs should be tested against other

TN-IBC cell lines. Suggestive evidence against unique SUM-149

effects is that most of the drugs active against SUM-149 were also

active against other TNBC cell lines. Another limitation of this

study was that the simple spheroid model does not fully

recapitulate IBC-specific in vivo mechanisms such as tumor

emboli formation and lymphangiogenesis. The use of Cmax in our data

analysis also has its limitations. Protein binding of drugs in

serum may alter the concentration of free drug in vivo

compared to 10% serum used in our in vitro studies. In

addition, the Cmax only reflects the concentration achieved in

blood, while the degree of tissue penetration may alter the

concentration of drug experienced by the tumor. In addition,

chronic dosing may increase the concentration of drug in the serum

and tumor. Thus, our use of Cmax in assessing the drugs is only a

rough guideline, but an improvement over ignoring the realities of

clinically achievable in vivo drug concentrations and how it

dramatically varies between drugs. The spheroids were not

characterized for properties described in the literature for

spheroid culture, including hypoxia, proliferation gradients and

necrotic centers. Therefore, validation of these properties in our

assays needs to be confirmed in future work.

Eltrombopag is a thrombopoietin receptor (TPOR)

agonist that is approved for treatment of thrombocytopenia. Despite

this originally designated target, eltrombopag has been

experimentally demonstrated to bind to multiple targets including

proteins such as BAK (41), TFEB

(42) and Syndecan-4 (43). Eltrombopag has also been reported to

directly inhibit BAX and prevent cell death (44). It has been reported to bind

double-stranded DNA (45), chelate

iron (46–48) and have anticancer activity in

multiple cell lines from many different tissue origins (49–52).

Despite low or undetectable TPOR in most tissues, eltrombopag has

been reported to inhibit cell growth in multiple different cancer

cell lines including breast cancer cell lines MCF-7, BT-474 and

TNBC cell line HCC1937 (50).

Eltrombopag has been reported as an inhibitor of the mRNA-binding

protein, HuR (human antigen R), which has been associated with poor

prognosis in multiple cancers (51,53,54).

In Zhu et al (53),

eltrombopag also inhibited cell proliferation in multiple cancer

cell lines, but no human TNBC cell lines were tested. In their

work, using the murine TNBC cell line 4T1, eltrombopag had an in

vitro IC50 of 13.5 µM, similar to our data with

human TN-IBC/TNBC cell lines. In a mouse allograft model using 4T1,

eltrombopag also had in vivo activity where it inhibited

tumor growth and metastasis and displayed anti-angiogenesis

activity (53,54). Our data adds to this body of

research since we demonstrated that eltrombopag had activity in 3

of 4 human TNBC cell lines grown in spheroid form, including a

TN-IBC cell line, with potencies similar to its Cmax. At

the highest concentration tested, 40 µM, eltrombopag was cytotoxic

in two of the four cell lines. The weak potency of eltrombopag

against SUM-159 (GI50 >40 µM) also suggests some TNBC

cancers may be resistant to this drug. According to RNAseq data

accessed through the Depmap portal (https://depmap.org), the expression level of the gene

for TPOR (MPL) is very low (close to undetectable) in all four cell

lines used in this study, which is consistent with undetectable

expression of MPL mRNA in 118 advanced or metastatic breast cancer

samples from patients (50).

However, TPOR expression in the cell lines used in this study needs

to be confirmed in future studies. Due to the many off-target

activities that have been ascribed to eltrombopag, it is not clear

which mechanism was producing the observed activity in our assays.

The Cmax of 14 µM cited herein was the result of a

single dose of 50 mg of eltrombopag in healthy adults (35). Another study dosed healthy adults

with up to 75 mg of eltrombopag per day for 10 days and concluded

that there were no significant adverse effects compared to placebo

(55). In this study, the 30-, 50-,

and 75-mg dose levels resulted in mean increases in platelet counts

of 24.1, 42.9, and 50.4%, respectively. The normal platelet count

in adults ranges from 150,000 to 450,000 platelets per microliter,

with counts exceeding 450,000 platelets per microliter defined as

thrombocytosis (56). Thus,

depending on an individual's baseline platelet count, even a 50%

increase in platelet count caused by eltrombopag treatment may

still be within normal range. A long-term study in patients with

chronic immune thrombocytopenia taking eltrombopag for up to 3

years (median daily dosing of 51.5 mg) found that the most common

adverse events were headache, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory

tract infection, and fatigue, but these were mostly mild (57). Of note, 13% of patients experienced

≥1 adverse event, leading to study withdrawal. Importantly, no new

or increased incidence of safety issues were identified in this

study and the authors concluded that long-term treatment with

eltrombopag was generally safe and well tolerated. Overall, our

data indicated that eltrombopag may have potential for repurposing

for TN-IBC and TNBC in general.

Papaverine, a vasodilator traditionally used to

treat vascular spasms, has been reported to primarily target the

phosphodiesterase PDE10A and, less potently, other

phosphodiesterases, leading to increased intracellular

concentrations of cAMP (58). In

MDA-MB-231, cell growth has been reported to be inhibited by agents

that elevate intracellular cAMP levels, i.e., 8-bromo-cAMP, cholera

toxin, forskolin, and papaverine (59,60).

Papaverine has also been reported to inhibit mitochondrial complex

1, reducing oxidative phosphorylation and oxygen consumption in

cells (61). This latter mechanism

has been proposed to explain papaverine's ability to enhance

radiation sensitivity of cancer cells, since higher oxygen levels

lead to more radiation damage. Papaverine has also been reported to

inhibit cell proliferation and migration of non-small cell lung

cancer cell lines through allosteric binding directly to CDK5 and

inhibiting its activity (62). This

drug has also been reported to inhibit a panel of human liver cell

lines with IC50 values ranging from 1.7 to 52 µM

(63). In a different report,

papaverine was reported to selectively inhibit the growth of human

prostate cancer cell line PC-3 and induce apoptosis (64). Papaverine was identified in a screen

for small molecules that sensitize tumor cells to glucose

starvation and this effect was confirmed with four different cell

lines (65). In a xenograft mouse

model using the DLD1 colon cell line, modest in vivo

anti-tumor activity of papaverine was observed, but a strong

combination effect was observed when combined with bevacizumab, an

inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (65). In another study, papaverine

demonstrated anti-proliferative activity for MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

breast cancer cell lines (66).

Notably, we are the first to report papaverine activity against an

IBC cell line and human TNBC cell lines other than MDA-MB-231. In

contrast, our data for papaverine showed weak to no activity

against MDA-MB-231 (>12 to >20 µM GI50) which may

be due to differing culture conditions-we employed spheroid growth

instead of traditional 2-D culture. It is well known that spheroid

growth can shift the potency of compounds compared to 2-D growth.

In follow-up mechanism studies, it will be important to determine

if there is a correlation between cAMP elevation or mitochondrial

inhibition in papaverine treated cells and cell line sensitivity to

this drug. There is an oral form of papaverine available and one

study using chronic dosing of oral papaverine reported no adverse

events associated with the drug (67). However, hepatotoxicity in some

patients taking oral papaverine has been reported (68).

Mozavaptan is a vasopressin V2 receptor (V2R)

antagonist that is primarily used for hyponatremia. In our study,

mozavaptan inhibited proliferation of 3 out of 4 TNBC cell lines

grown in spheroid form and Hs578T grown in 2-D with a range of

GI50s of 2.7–7.6 µM. Mozavaptan has been approved in

Japan, but not by the FDA, so we also tested another member of

vasopressin receptor antagonist family that is

FDA-approved-tolvaptan. Tolvaptan did not show the same

activity/potency as mozavaptan. For example, mozavaptan inhibited

MDA-MB-231 cells with a GI50 of 3.3 µM, but tolvaptan

was >20 µM. Tolvaptan has a reported IC50 of 0.2 nM

for its target in one cell-based assay (69) and mozavaptan has a reported

IC50 of 19 nM in a CHO V2R expression system (70). Thus, given (1) the high potency of mozavaptan and

tolvaptan for V2R in contrast to our relatively high

GI50 values and (2)

inconsistent activity between the two drugs in our study, our data

is highly suggestive that the antiproliferative activity of both

drugs in our study were due to off-target activity. According to

The Human Protein Atlas database (https://www.proteinatlas.org), the RNA level of the

V2R gene (AVPR2) was 0.0 normalized transcript per million (nTPM)

for MDA-MB-231, SUM-159 and HCC1806, while RNA level for SUM-149

was 1.3 nTPM. Thus, this data indicated a lack of correlation

between V2R RNA expression and sensitivity to mozavaptan since we

observed mozavaptan activity in the cell lines not expressing V2R

RNA, but no activity in SUM-149 that may express some level of V2R

RNA (but very low). This database also reports undetectable V2R

protein levels in MDA-MB-231 and HCC1806, with no data on the other

cell lines. In contrast, one study showed V2R expression in

MDA-MB-231 (and MCF-7 and mouse F3II mammary cell line) by

immunohistochemistry (71). This

same study demonstrated that a synthetic peptide agonist for V2R,

desmopressin, was cytostatic in proliferation assays using

MDA-MB-231 and reduced tumor growth and angiogenesis in mouse

models using MDA-MB-231 and F3II. However, tolvaptan and mozavaptan

are both potent antagonists of V2R and thus V2R antagonism as a

mechanism would be inconsistent with this prior study. One

hypothesis to explain all this data is that V2R does not play a

role in the mechanisms for these drugs in our assays and the broad

activity observed for mozavaptan is off-target activity for a

target not shared by tolvaptan (or same off-target, but

differential potency) due to structural differences between the

drugs. It was not possible to determine the potency of mozavaptan

relative to the Cmax since this data was not readily

available in the literature. Thus, it is difficult to assess the

potential for in vivo activity of mozavaptan at

physiological doses. In terms of adverse events, mozavaptan has

been reported to have no serious adverse events, with the most

common being dry mouth (72).

Spironolactone is a mineralocorticoid receptor

antagonist along with being a nonselective antagonist of androgen

and progesterone receptors (73).

It functions as a potassium-sparing diuretic that is used to treat

high blood pressure, heart failure and other conditions.

Spironolactone only had activity against the TN-IBC cell line

suggesting some unique target or pathway dependency in this cell

line compared to the other TNBC cell lines. Since spironolactone is

a weak antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR), it is possible

that this was the target in SUM-149. However, it has been reported

that SUM-149 does not express AR, but SUM-159 does (74), which does not fit our activity

results. Spironolactone has also been reported to be a nucleotide

excision repair (NER) inhibitor (75). This mechanism involves

spironolactone inducing degradation of the XPB helicase that is

part of the TFIIH transcription/repair complex involved in NER.

This group also reported no inhibition with 10 µM spironolactone in

four- or five-day cell viability assays using HeLa, A2780 and

HCT-116 cell lines. These cell lines along with MDA-MB-231, HCC1806

and SUM-159 have wild type BRCA1 (76–80).

Unique in our panel, SUM-149 has a BRCA1 frameshift mutation and

allele loss that may make it more dependent on remaining DNA repair

functions (76). Notably, only 3

out of 41 human breast cancer cell lines had BRCA1 mutations (with

allele loss), with SUM-149 being one of them. This DNA repair

defect may make SUM-149 more sensitive to inhibition of NER by

spironolactone. Thus, the SUM-149-specific sensitivity to

spironolactone may be due to a synthetic lethal type response in

this cell line and this would explain the unusual sensitivity of

SUM-149 to spironolactone. The spironolactone GI50 of

3.5 µM against SUM-149 is 10-fold higher than the Cmax

of 0.35 µM. Therefore, it is unclear if it would have any

significant activity in humans. Spironolactone has been reported to

have no significant impact on the risk of breast cancer in a

meta-analysis (81). However, one

recent study of younger women taking spironolactone indicated a

slight beneficial effect in terms of BC risk (82). If there is a positive impact for the

relatively rare IBC, then it would probably not be detectable

within a population of mostly non-IBC patients. The common adverse

event associated with long-term spironolactone use is menstrual

irregularities, which are dose-dependent and can be countered with

oral contraceptives or intrauterine devices (83). Other infrequent adverse events

include increased urination, lightheadedness, headaches, nausea,

vomiting, breast discomfort, and breast enlargement. Since it is a

potassium-retaining diuretic, elevated potassium level

(hyperkalemia) is another possible side effect, especially in

patients with renal dysfunction or heart failure.

The adverse effects of the other identified drugs

also provide insight into their potential for re-purposing. For

adefovir, the most common adverse events were similar to placebo,

except that headache and abdominal pain occurred more frequently

with adefovir but did not lead to discontinuation (84). Adefovir is associated with

dose-dependent increased risk of renal toxicity and thus,

monitoring would be important. For dolutegravir, the most common

adverse events reported were diarrhea, fatigue, and headache

(85). However, the majority of

these adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Based on a

recent analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database,

dolutegravir treatment decision should also include restrictions on

contraindicated populations (e.g. pregnant, hepatobiliary

disorders) (86). In a study with

healthy volunteers, no serious adverse events occurred during a

7-day study of dronedarone (87).

However, dronedarone can induce prolonged RR and QT intervals as a

function of dose, without effect on circadian patterns, which

suggests potential proarrhythmic risk (88). For the anti-malarial drug

halofantrine, clinical studies are short term in nature. The main

serious adverse effect associated with halofantrine use is QT

interval prolongation which prevents its use for long term

treatment at normal doses (89).

In summary, we identified eltrombopag and papaverine

as having anti-proliferative activity against SUM-149 and other

TNBC cell lines. Furthermore, these drugs had

GI50:Cmax ratios of 1–2 for sensitive cell

lines, suggesting that they are potent enough to potentially have

activity in vivo. Therefore, these drugs should be further

tested against patient-derived organoids (PDO) and xenograft models

of TN-IBC and TNBC to assess their activity alone and in

combination with other drugs.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The project described was partially supported by the National

Institutes of Health through the RCMI grant NIH/NIMHD (grant no.

U54MD012392). This project was also partially funded by internal

grants from BRITE at North Carolina Central University.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The dataset used in this

article to identify candidate non-oncology drugs has been

previously published (12) and is

publicly available in the PRISM database (https://depmap.org/repurposing).

Authors' contributions

SA performed spheroid-based cell

proliferation/cytotoxicity assays, analyzed the results and

interpreted the data. SK performed the 2-D cell

proliferation/cytotoxicity assays, analyzed the results and

interpreted the data. KPW contributed to the conception and design

and revision of the manuscript. JES contributed to the conception

and design, analysis of the results, interpretation of the data and

drafting of the manuscript. SA and SK confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Kevin P. Williams, ORCID: 0000000269304630; John E.

Scott, ORCID: 0000-0002-5987-9334.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BC

|

breast cancer

|

|

TNBC

|

triple-negative breast cancer

|

|

IBC

|

inflammatory breast cancer

|

|

TN-IBC

|

triple-negative inflammatory breast

cancer

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

GI

|

growth inhibition

|

|

CTG

|

CellTiter Glo

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

2-D

|

two-dimension

|

|

NOD

|

non-oncology drug

|

|

Cmax

|

maximal concentration

|

|

SD

|

standard deviation

|

|

ER

|

estrogen receptor

|

|

FDA

|

Food and Drug Administration

|

|

ATCC

|

American Type Tissue Collection

|

|

TPOR

|

thrombopoietin receptor

|

|

V2R

|

vasopressin V2 receptor

|

|

NER

|

nucleotide excision repair

|

|

AR

|

androgen receptor

|

References

|

1

|

Beňačka R, Szabóová D, Guľašová Z,

Hertelyová Z and Radoňák J: Classic and new markers in diagnostics

and classification of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14:54442022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lee J: Current treatment landscape for

early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). J Clin Med.

12:15242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Russnes HG, Lingjærde OC, Børresen-Dale AL

and Caldas C: Breast cancer molecular stratification: From

intrinsic subtypes to integrative clusters. Am J Pathol.

187:2152–2162. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Devi GR, Hough H, Barrett N, Cristofanilli

M, Overmoyer B, Spector N, Ueno NT, Woodward W, Kirkpatrick J,

Vincent B, et al: Perspectives on inflammatory breast cancer (IBC)

research, clinical management and community engagement from the

duke IBC consortium. J Cancer. 10:3344–3351. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Boussen H, Berrazaga Y, Sherif K, Manai M,

Berrada N, Mejri N, Siala I, Levine PH and Cristofanilli M:

Inflammatory breast cancer: Epidemiologic data and therapeutic

results. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 384:1–23. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Matro JM, Li T, Cristofanilli M, Hughes

ME, Ottesen RA, Weeks JC and Wong YN: Inflammatory breast cancer

management in the national comprehensive cancer network: The

disease, recurrence pattern, and outcome. Clin Breast Cancer.

15:1–7. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hester RH, Hortobagyi GN and Lim B:

Inflammatory breast cancer: Early recognition and diagnosis is

critical. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 225:392–396. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Biswas T, Efird JT, Prasad S, James SE,

Walker PR and Zagar TM: Inflammatory TNBC breast cancer: Demography

and clinical outcome in a large cohort of patients with TNBC. Clin

Breast Cancer. 16:212–216. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chainitikun S, Saleem S, Lim B, Valero V

and Ueno NT: Update on systemic treatment for newly diagnosed

inflammatory breast cancer. J Adv Res. 29:1–12. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Al Khzem AH, Gomaa MS, Alturki MS, Tawfeeq

N, Sarafroz M, Alonaizi SM, Al Faran A, Alrumaihi LA, Alansari FA

and Alghamdi AA: Drug repurposing for cancer treatment: A

comprehensive review. Int J Mol Sci. 25:124412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Szalai P and Engedal N: An image-based

assay for high-throughput analysis of cell proliferation and cell

death of adherent cells. Bio Protoc. 8:e28352018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Corsello SM, Nagari RT, Spangler RD,

Rossen J, Kocak M, Bryan JG, Humeidi R, Peck D, Wu X, Tang AA, et

al: Discovering the anti-cancer potential of non-oncology drugs by

systematic viability profiling. Nat Cancer. 1:235–248. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Culley J, Nagle PW, Dawson JC and

Carragher NO: Patient derived glioma stem cell spheroid reporter

assays for live cell high content analysis. SLAS Discov. 28:13–19.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pfab C, Schnobrich L, Eldnasoury S,

Gessner A and El-Najjar N: Repurposing of antimicrobial agents for

cancer therapy: What do we know? Cancers (Basel). 13:31932021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bhattacharya U, Kamran M, Manai M,

Cristofanilli M and Ince TA: Cell-of-origin targeted drug

repurposing for triple-negative and inflammatory breast carcinoma

with HDAC and HSP90 inhibitors combined with niclosamide. Cancers

(Basel). 15:3322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

da Silva Fernandes T, Gillard BM, Dai T,

Martin JC, Chaudhry KA, Dugas SM, Fisher AA, Sharma P, Wu R,

Attwood KM, et al: Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 (IMPDH2)

modulates response to therapy and chemo-resistance in triple

negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 15:10612025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kim JH, Park S, Jung E, Shin J, Kim YJ,

Kim JY, Sessler JL, Seo JH and Kim JS: A dual-action

niclosamide-based prodrug that targets cancer stem cells and

inhibits TNBC metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e23040811202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Greenshields AL, Fernando W and Hoskin DW:

The anti-malarial drug artesunate causes cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis of triple-negative MDA-MB-468 and HER2-enriched SK-BR-3

breast cancer cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 107:10–22. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zadeh T, Lucero M and Kandpal RP:

Artesunate-induced cellular effects are mediated by specific EPH

receptors and ephrin ligands in breast carcinoma cells. Cancer

Genomics Proteomics. 19:19–26. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu H, Sun H, Zhang B, Liu S, Deng S, Weng

Z, Zuo B, Yang J and He Y: 18F-FDG PET imaging for

monitoring the early anti-tumor effect of albendazole on

triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 27:372–380. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Priotti J, Baglioni MV, Garcia A, Rico MJ,

Leonardi D, Lamas MC and Menacho Márquez M: Repositioning of

anti-parasitic drugs in cyclodextrin inclusion complexes for

treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. AAPS PharmSciTech.

19:3734–3741. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kieliszek AM, Mobilio D, Bassey-Archibong

BI, Johnson JW, Piotrowski ML, de Araujo ED, Sedighi A, Aghaei N,

Escudero L, Ang P, et al: De novo GTP synthesis is a metabolic

vulnerability for the interception of brain metastases. Cell Rep

Med. 5:1017552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Benjanuwattra J, Chaiyawat P, Pruksakorn D

and Koonrungsesomboon N: Therapeutic potential and molecular

mechanisms of mycophenolic acid as an anticancer agent. Eur J

Pharmacol. 887:1735802020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Abdelwahab MT, Wasserman S, Brust JCM,

Gandhi NR, Meintjes G, Everitt D, Diacon A, Dawson R, Wiesner L,

Svensson EM, et al: Clofazimine pharmacokinetics in patients with

TB: Dosing implications. J Antimicrob Chemother. 75:3269–3277.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bullingham RE, Nicholls AJ and Kamm BR:

Clinical pharmacokinetics of mycophenolate mofetil. Clin

Pharmacokinet. 34:429–455. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ceballos L, Alvarez L, Lifschitz A and

Lanusse C: Ivermectin systemic availability in adult volunteers

treated with different oral pharmaceutical formulations. Biomed

Pharmacother. 160:1143912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Friedrich C, Richter E, Trommeshauser D,

de Kruif S, van Iersel T, Mandel K and Gessner U: Absence of

excretion of the active moiety of bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate

into human breast milk: An open-label, parallel-group,

multiple-dose study in healthy lactating women. Drug Metab

Pharmacokinet. 26:458–464. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Girard PM, Clair B, Certain A, Bidault R,

Matheron S, Regnier B and Farinotti R: Comparison of plasma

concentrations of aerosolized pentamidine in nonventilated and

ventilated patients with pneumocystosis. Am Rev Respir Dis.

140:1607–1610. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kouakou YI, Tod M, Leboucher G, Lavoignat

A, Bonnot G, Bienvenu AL and Picot S: Systematic review of

artesunate pharmacokinetics: Implication for treatment of resistant

malaria. Int J Infect Dis. 89:30–44. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Milton KA, Edwards G, Ward SA, Orme ML and

Breckenridge AM: Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in man: Effects

of food and dose size. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 28:71–77. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Naccarelli GV, Wolbrette DL, Levin V,

Samii S, Banchs JE, Penny-Peterson E and Gonzalez MD: Safety and

efficacy of dronedarone in the treatment of atrial

fibrillation/flutter. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 5:103–119. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ross LL, Song IH, Arya N, Choukour M, Zong

J, Huang SP, Eley T, Wynne B and Buchanan AM: No clinically

significant pharmacokinetic interactions between dolutegravir and

daclatasvir in healthy adult subjects. BMC Infect Dis. 16:3472016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Schulz M and Schmoldt A: Therapeutic and

toxic blood concentrations of more than 800 drugs and other

xenobiotics. Pharmazie. 58:447–474. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Schweizer MT, Haugk K, McKiernan JS,

Gulati R, Cheng HH, Maes JL, Dumpit RF, Nelson PS, Montgomery B,

McCune JS, et al: A phase I study of niclosamide in combination

with enzalutamide in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer.

PLoS One. 13:e01983892018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Williams DD, Peng B, Bailey CK, Wire MB,

Deng Y, Park JW, Collins DA, Kapsi SG and Jenkins JM: Effects of

food and antacids on the pharmacokinetics of eltrombopag in healthy

adult subjects: Two single-dose, open-label, randomized-sequence,

crossover studies. Clin Ther. 31:764–776. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Xu FG, Zhang ZJ, Dong HJ, Tian Y, Liu Y

and Chen Y: Bioequivalence assessment of two formulations of

spironolactone in Chinese healthy male volunteers.

Arzneimittelforschung. 58:117–121. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zou J, Di B, Zhang J, Dai L, Ding L, Zhu

Y, Fan H and Xiao D: Determination of adefovir by LC-ESI-MS-MS and

its application to a pharmacokinetic study in healthy Chinese

volunteers. J Chromatogr Sci. 47:889–894. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Abbas ZN, Al-Saffar AZ, Jasim SM and

Sulaiman GM: Comparative analysis between 2D and 3D colorectal

cancer culture models for insights into cellular morphological and

transcriptomic variations. Sci Rep. 13:183802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Filipiak-Duliban A, Brodaczewska K,

Kajdasz A and Kieda C: Spheroid culture differentially affects

cancer cell sensitivity to drugs in melanoma and RCC models. Int J

Mol Sci. 23:11662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li J, Lin J, Lin JR, Farris M, Robbins L,

Andrada L, Grohol B, Nong S and Liu Y: Dolutegravir inhibits