Introduction

With increasing life expectancy, the morbidity of

prostate cancer (PCa) has risen rapidly. According to data from the

American Center for Cancer Research, PCa is now the most common

malignancy with 29% incidence rate and the second leading cause of

cancer-associated mortality with 11% death rate among men in the

United States in 2024 (1). Its

incidence is also increasing rapidly in China, where PCa has become

the fastest-growing malignancy with an incidence rate of 0.02% in

2022 among men (2). Effective

treatments such as ablative radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy

can markedly prolong survival (3).

Antiandrogen drugs can also effectively treat locally advanced and

metastatic PCa (4). By decreasing

androgen receptor (AR) expression (5), these drugs alleviate clinical symptoms

such as bone pain, difficulty with urinating and extend survival

(6). However, drug resistance

inevitably develops and the mechanisms underlying antiandrogen

resistance remain to be elucidated.

Antiandrogen therapy reduces androgen activity

through drugs (7), such as

bicalutamide (BIC), enzalutamide (ENZ) and apalutamide (APN)

(8). BIC is a non-steroidal

antiandrogen that inhibits the binding of testicular and adrenal

androgens to AR (9). ENZ prevents

nuclear translocation of activated AR, binding to androgen response

elements and coactivator recruitment, thereby suppressing PCa

proliferation (10). APN, another

non-steroidal antiandrogen, binds directly to the AR ligand-binding

domain and inhibits AR translocation, DNA binding and AR-mediated

transcription (11). These drugs

can inhibit PCa progression by decreasing AR expression. Although

these drugs provide clinical benefit, resistance eventually

develops and the underlying mechanisms require further study.

Genetic alterations are increasingly recognized as

key contributors to both PCa development and drug resistance. For

instance, microseminoprotein-β expression changes may influence PCa

risk in obese individuals (12),

while alterations in cyclin B1 and golgin A8 family member B have

been associated with chemotherapy resistance (13,14).

Bcl-2-binding component 3 mutations contribute to olaparib

resistance (15) and CDK6

dysregulation has been associated with ENZ resistance (16). Collectively, these studies

underscore the key role of genetic changes in PCa development and

therapeutic resistance, suggesting that additional genetic factors

may contribute to antiandrogen resistance.

The present study attempted to use bioinformatic

methods to find the hub genes which are important for PCa

resistance to antiandrogen drugs and verified their function using

different types of PCa cell lines. RNA-sequencing data of lymph

node carcinoma of the prostate (LNCaP) cells resistant to BIC, ENZ

and APN (GSE211781 dataset) were obtained to find the hub genes.

RNA-sequence data from public databases such as Gene Expression

omnibus (GEO), The Cancer Genome Atlast (TCGA) and Chinese Prostate

Cancer Genome and Epigenome Atlas (CPGEA) were used to analyze the

function of hub genes in affecting PCa progression and prognosis.

Finally, the role of hub genes in influencing PCa cells sensitive

to antiandrogen drugs were verified in two types of PCa cell lines:

LNCaP and C4-2.

Materials and methods

Data source

The GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) is a publicly available

repository containing microarray data for various diseases

(17). Meanwhile, TCGA (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) is a large public

database that provides sequencing and clinical data for multiple

cancer types (18). Gene expression

data for prostate adenocarcinoma in TCGA database (TCGA-PRAD) was

searched. The Chinese Prostate Cancer Genome and Epigenome Atlas

(CPGEA; http://www.cpgea.com/) includes

microarray data from Chinese patients with PCa (19). Gene expression and clinical data

were obtained from these databases.

Data handling

The GSE211781 dataset (20) consists of RNA-sequencing data from

LNCaP PCa cells resistant to antiandrogen drugs, including BIC, ENZ

and APN, and was used to identify DEGs associated with drug

resistance. In addition, the GSE136129 and GSE81796 datasets

(21,22), which contain RNA-sequencing data

from C4-2 PCa cells resistant to ENZ, were also collected. TCGA

provides clinical information and microarray data from 497 patients

with PCa and 52 healthy controls. The CPGEA database contains

microarray data from 136 paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues

from Chinese patients with PCa. All primary data from these public

databases were normalized using the R package ‘limma’ (version,

3.40.2; R Development Core Team) (23).

Survival analysis

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

(GEPIA; http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) an

online tool, was used to evaluate the effects of genes on patient

survival based on TCGA data (24).

Disease-free survival (DFS) was assessed using GEPIA.

Identifying antiandrogen drug

resistance genes (ADRGs) and constructing the PPI network

ADRGs in the GSE211781 dataset were identified based

on the following criteria: i) Adjusted P<0.05 and

log2 fold-change (FC) >1; and ii) expression changes

observed in response to all three antiandrogen drugs.

A PPI network of these ADRGs was constructed using

the STRING database. Raw PPI data were downloaded from STRING

(http://string-db.org/) (25) and reconstructed with Cytoscape

(version, 3.9.1; http://cytoscape.org/) software (26). Hub genes were identified as those

exhibiting the highest connectivity within the network (16).

Cell culture and transduction

The C4-2 and LNCaP PCa cell lines were purchased

from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank. Cell culture and

transduction were performed as previously described (27). Briefly, cells were maintained in

RPMI 1640 medium (cat. no. R8758; MilliporeSigma) supplemented with

10% FBS (cat. no. 10091; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C.

Antibiotics were not used and cells were passaged when density

reached 80%. All lines were tested using a mycoplasma detection kit

(cat. no. C0298; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) to confirm

that the cells are free of mycoplasma contamination (cat. no.

MP0030; MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA).

Cell transduction

To generate PCa cells with MYH11 knockdown, the 2nd

generation system was utilized comprising the packaging plasmids

pMD2.G (plasmid cat. no. 12259; Addgene, Inc.) and psPAX2 (plasmid

cat. no. 12260; Addgene, Inc.). For each 6-well plate, 5.5 µg

pLVX-shMYH11 and 2.0 µg pMD2.G was used to transfect cells for 12 h

at 37°C by Lipofectamine™ 2000 (cat. no. 11668019; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and polyethyleneimine (PEI; cat. no. 408700;

MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA), according to the manufacturers'

protocol. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting MYH11 and a negative

control (shControl) lentivirus were constructed by Hebei Youze

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Lentiviral packaging plasmids were

transduced into 293T cells using PEI for 12 h at 37°C. The culture

medium was replaced at 24 h post-transduction and supernatants were

collected at 48 h. These were then used to infect PCa cells with

multiplicity of infection of 2 at 37°C for 48 h. Following

transduction, cells exhibiting stable integration were selected

using puromycin (cat. no. P8833; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 1.0

µg/ml for 5 days. The shMYH11 sequences were sense (S),

5′-GCAAATTCATCCGCATCAACT-3′ and antisense (AS),

3′-AGTTGATGCGGATGAATTTGC-5′, and the shControl sequences were S,

5′-GCTCACACGGATGTAGG-3′ and AS, 3′-CCTACATCCGTGTGAGCA-5′, which do

not affect gene expression in these cells.

Drug treatment

BIC (cat. no. S1190) and ENZ (cat. no. S1250) were

purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Untreated C4-2 and LNCaP cells

were exposed to 40 µM BIC or ENZ for 10 days before subsequent

experiments. After transduction with lentivirus, cells were treated

with 80 µM BIC or ENZ for 4 days at 37°C for further experiments.

In addition, the control cells were treated with 0.5% DMSO for 4

days at 37°C.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation experiments were performed 48 h

after transduction, as previously described (26). Proliferation was assessed using the

Cell Counting Kit-8 kit (CCK-8; cat. no. CA1210; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Cells were seeded in 96-well

plates (3,000 cells/well) and cultured in 200 µl RPMI 1640 medium

supplemented with 10% FBS for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. The cells were

treated with BIC or ENZ at 40 or 80 µM according to experimental

requirements. After incubation, cells were treated with CCK-8

reagent for 1 h following the manufacturer's instructions and

absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a multimode reader (cat.

no. LB942; Titertek-Berthold).

Western blotting

Western blotting experiments were performed as

previously described (28). Total

proteins were extracted from samples and cell lines using RIPA

lysis buffer with a protease inhibitor cocktail (MilliporeSigma;

Merck KGaA). Then, the protein concentration was detected by BCA

using a BCA kit (cat. no. P0012; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Then, protein samples were handled by Dual Color

Protein Loading Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal

amounts of protein (24 µg per lane) were added and separated via

SDS-PAGE (7.5 and 10% gels) and then transferred to nitrocellulose

membranes (cat. no. 71078; Merck KGaA). Membranes were blocked with

Protein-Free Rapid Blocking Buffer at 37°C for 1 h (cat. no. 37584;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies against MYH11 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab124679;

Abcam) and GAPDH (1:1,000; cat. no. ab9482; Abcam). The next day,

membranes were washed three times for 10 min each with 1X TBST with

0.1% Tween, then incubated at room temperature for 1 h with a

matched secondary antibody HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Human IgG (H+L)

(cat nos. A0216 and A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Signals were visualized using X-ray exposure (Abcam). Protein band

intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (version no.

1.54h; National Institutes of Health) and bar charts were generated

to present the results.

Statistical analysis

Data were obtained from at least three independent

experiments and are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between two

groups were assessed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test

and differences among ≥3 groups were analyzed with one-way ANOVA

followed by the Scheffe post hoc test to account for unequal group

sizes. The box plots were made using an online tool: Sangerbox

(http://sangerbox.com/index.html). All

statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 22.0; IBM

Corp.) and data from public databases were analyzed using R

software (version 4.0.3; R Development Core Team) with appropriate

packages. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

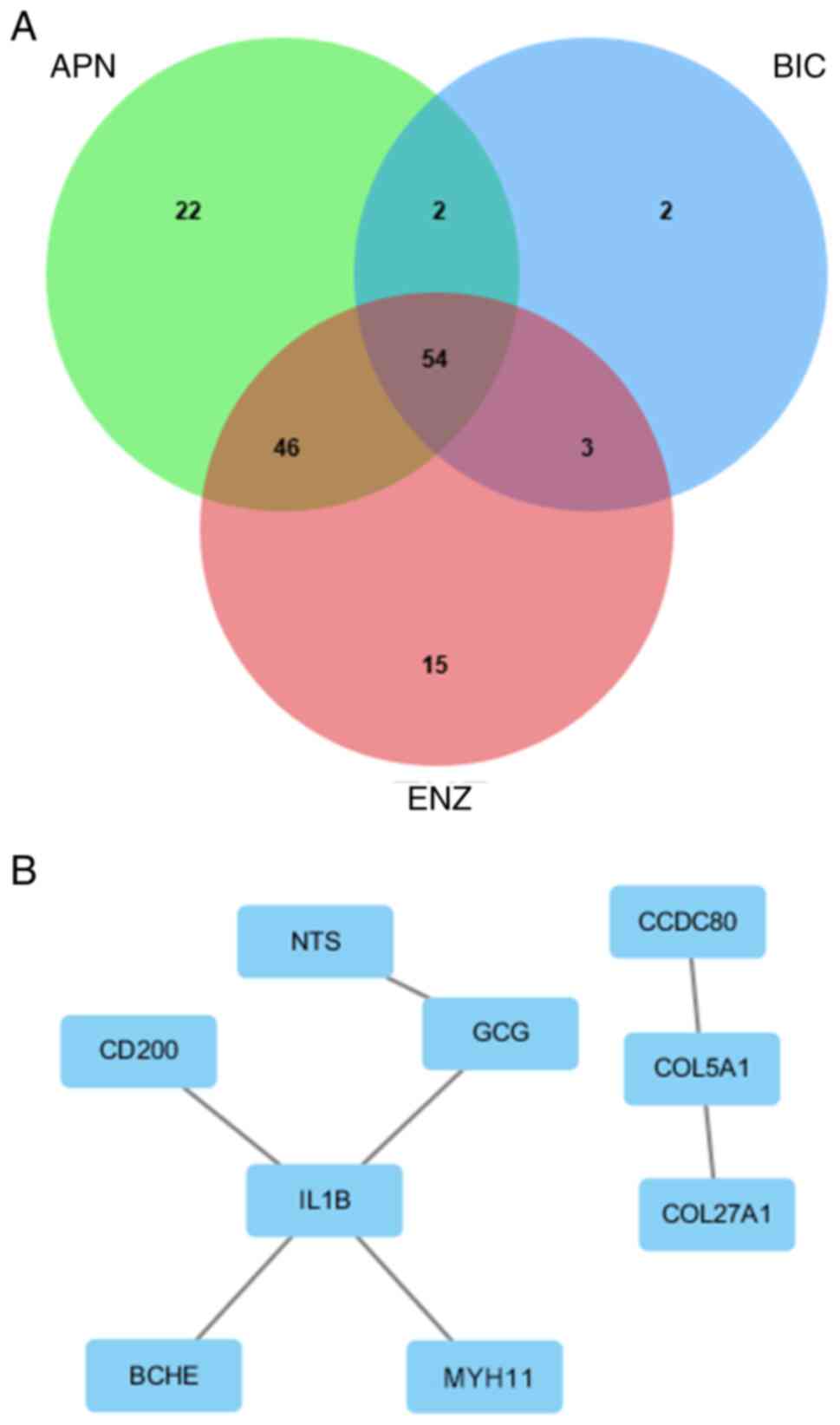

Identifying nine hub genes among 54

ADRGs from the GSE211781 dataset

The present study first analyzed the GSE211781

dataset to identify genes key for PCa resistance to antiandrogen

drugs. RNA-sequencing data from LNCaP cells resistant to BIC, ENZ

and APN were examined. In APN-resistant cells, 68 genes were

upregulated and 56 were downregulated. In BIC-resistant cells, 34

genes were upregulated and 27 were downregulated. In ENZ-resistant

cells, 70 genes were upregulated and 48 were downregulated.

Altogether, 54 genes were differentially expressed across all three

resistant cell lines, which were classified as ADRGs in the present

study (Fig. 1A). Table I summarizes the expression levels of

the nine hub genes identified among these 54 ADRGs and complete

expression data for all genes are presented in Table SI. A PPI network generated with

Cytoscape further revealed nine hub genes (NTS, GCG, CD200,

IL1B, BCHE, MYH11, CCDC80, COL5A1 and COL27A1) among

these ADRGs, each demonstrating strong connectivity with other

genes in the network (Fig. 1B).

| Table I.Hub genes of 54 ADRGs among BIC, ENZ

and APN in GSE211781 dataset. |

Table I.

Hub genes of 54 ADRGs among BIC, ENZ

and APN in GSE211781 dataset.

|

| BIC | ENZ | APN |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gene name | Log2

FC | P-value | Log2

FC | P-value | Log2

FC | P-value |

|---|

| CD200 | 2.0458783 |

5.93×10−19 | 1.59821854 |

4.63×10−12 | 3.0572163 |

9.50×10−21 |

| GCG | 1.3191416 |

5.76×10−14 | 1.11484425 |

1.26×10−8 | 3.9088046 |

4.55×10−12 |

| NTS | 2.7808322 |

3.18×10−10 | 3.02708496 |

8.10×10−7 | 2.7487693 |

2.77×10−10 |

| IL1B | −2.409564 |

8.70×10−8 | −1.6599581 |

1.08×10−5 | −1.1746371 |

1.38×10−8 |

| CCDC80 | −1.814258 |

5.51×10−6 | −1.9233845 |

1.06×10−4 | −1.6778532 |

3.09×10−7 |

| BCHE | 1.3011477 |

2.06×10−4 | 2.91307066 |

8.68×10−4 | 2.4957071 |

7.11×10−6 |

| MYH11 | 1.4286021 |

6.93×10−4 | 1.08698911 |

3.41×10−3 | 2.3045734 |

4.55×10−5 |

| COL5A1 | −3.935565 |

1.43×10−3 | −3.6223903 |

5.24×10−3 | −1.5384003 |

1.06×10−4 |

| COL27A1 | −1.532002 |

2.39×10−3 | −1.1766088 |

1.06×10−2 | −2.6972333 |

2.81×10−4 |

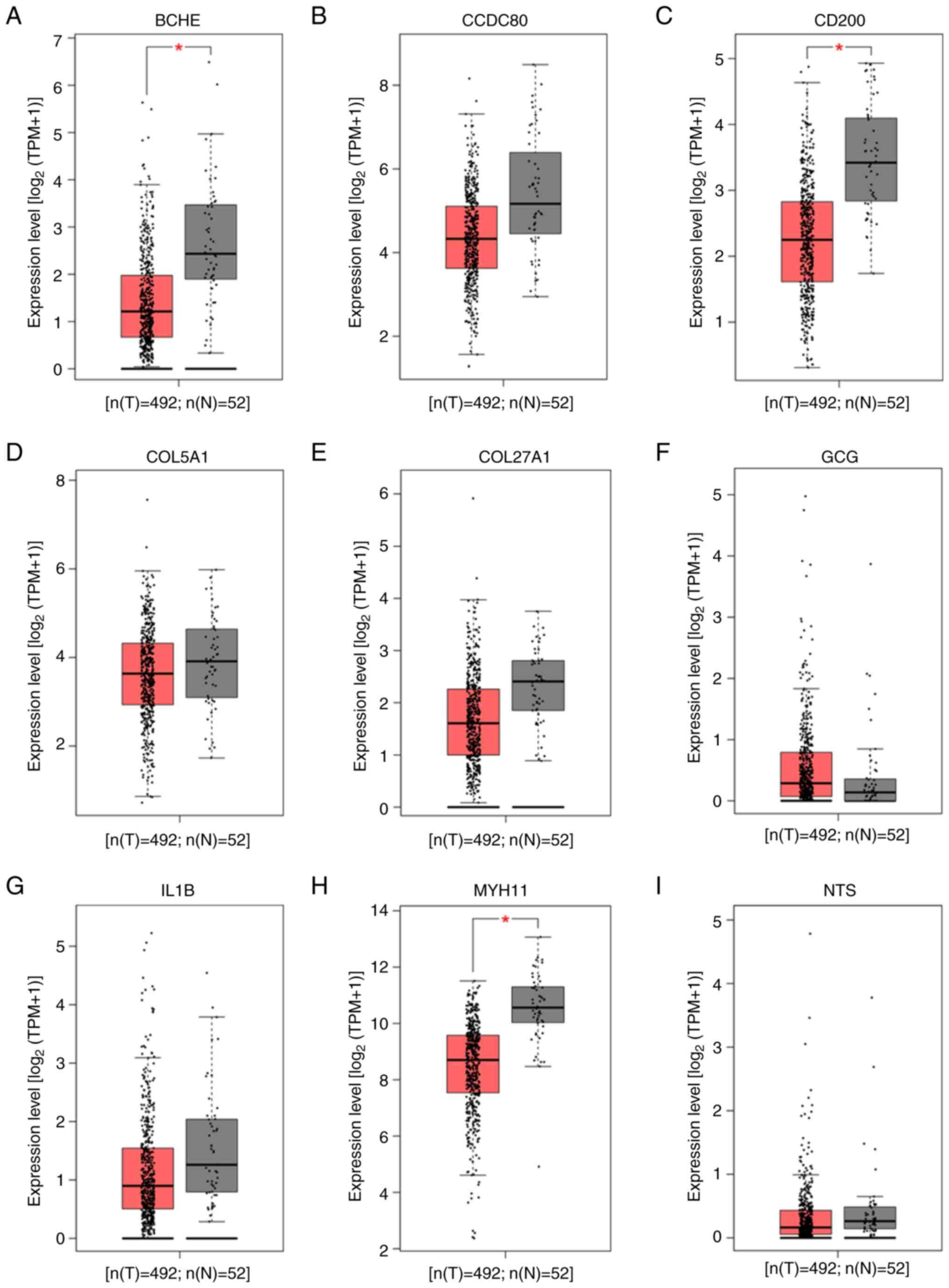

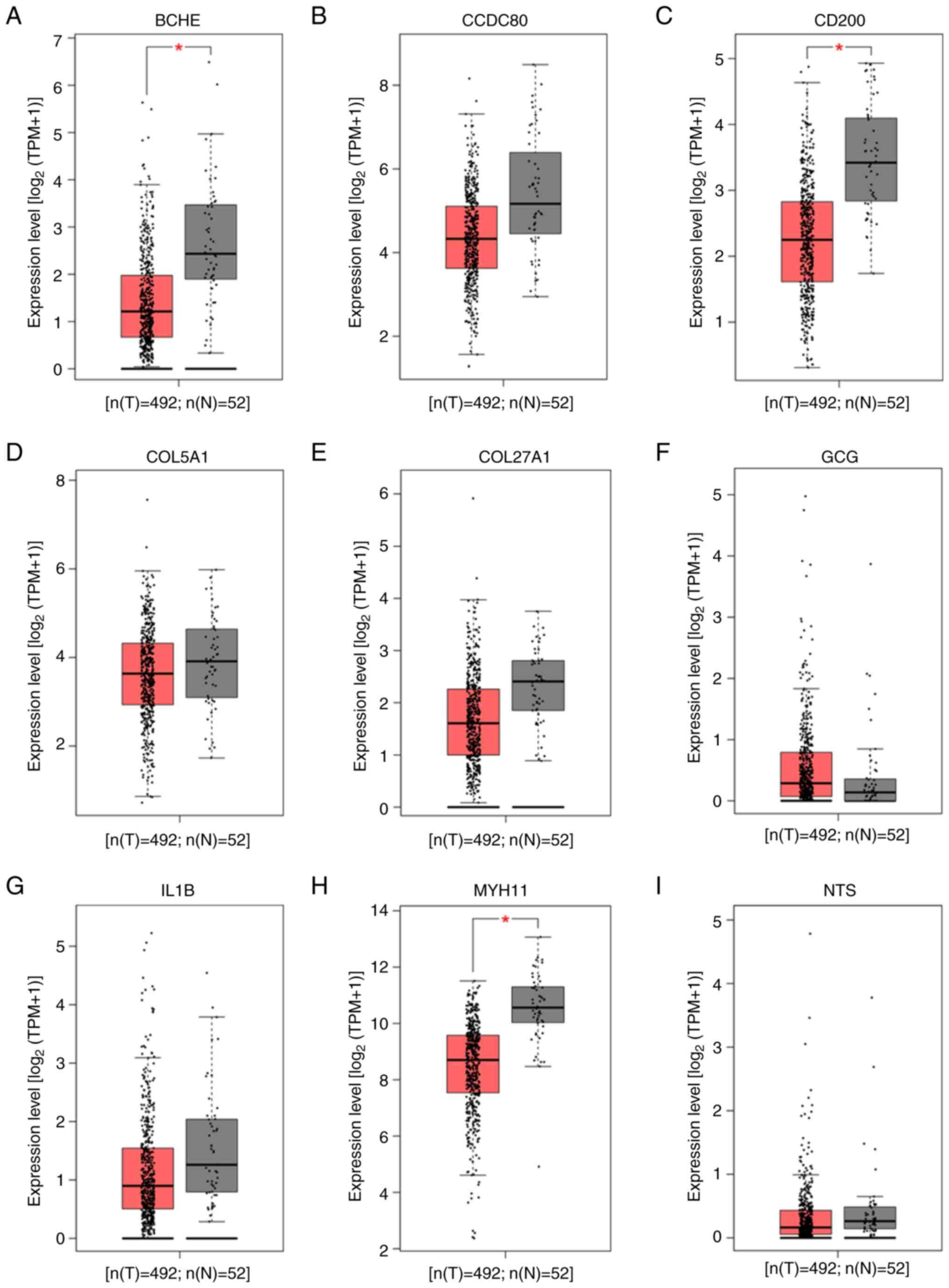

Hub genes from ADRGs influence PCa

occurrence

The present study next investigated whether these

nine hub genes were associated with PCa occurrence. GEPIA analysis

of TCGA-PRAD data was used to compare hub gene expression between

PCa samples and healthy prostate tissues. Among the nine hub genes,

BCHE (P=2.3×10−12), CD200

(P=5.8×10−17) and MYH11 (P=2.3×10−17)

were significantly downregulated in PCa samples compared with

healthy tissues (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Expression levels of nine hub genes

from ADRGs in PCa tissues and healthy prostate tissues analyzed

using the GEPIA online tool based on TCGA. Expression levels of (A)

BCHE, (B) CCDC80, (C) CD200, (D) COL5A1, (E) COL27A1, (F) GCG, (G)

IL1B, (H) MYH11 and (I) NTS. *P<0.05. ADRGs, antiandrogen drug

resistance genes; PCa, prostate cancer; GEPIA, Gene Expression

Profiling Interactive Analysis; TGCA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

CD200, cluster of differentiation 200; BCHE, butyrylcholinesterase;

CCDC80, coiled-coil domain containing 80; COL5A1, collagen type V α

1 chain; COL27A1, collagen type XXVII α 1 chain; GCG, glucagon;

IL1B, interleukin 1β; MYH11, myosin heavy chain 11; NTS,

neurotensin; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; T, tumor; N,

normal. |

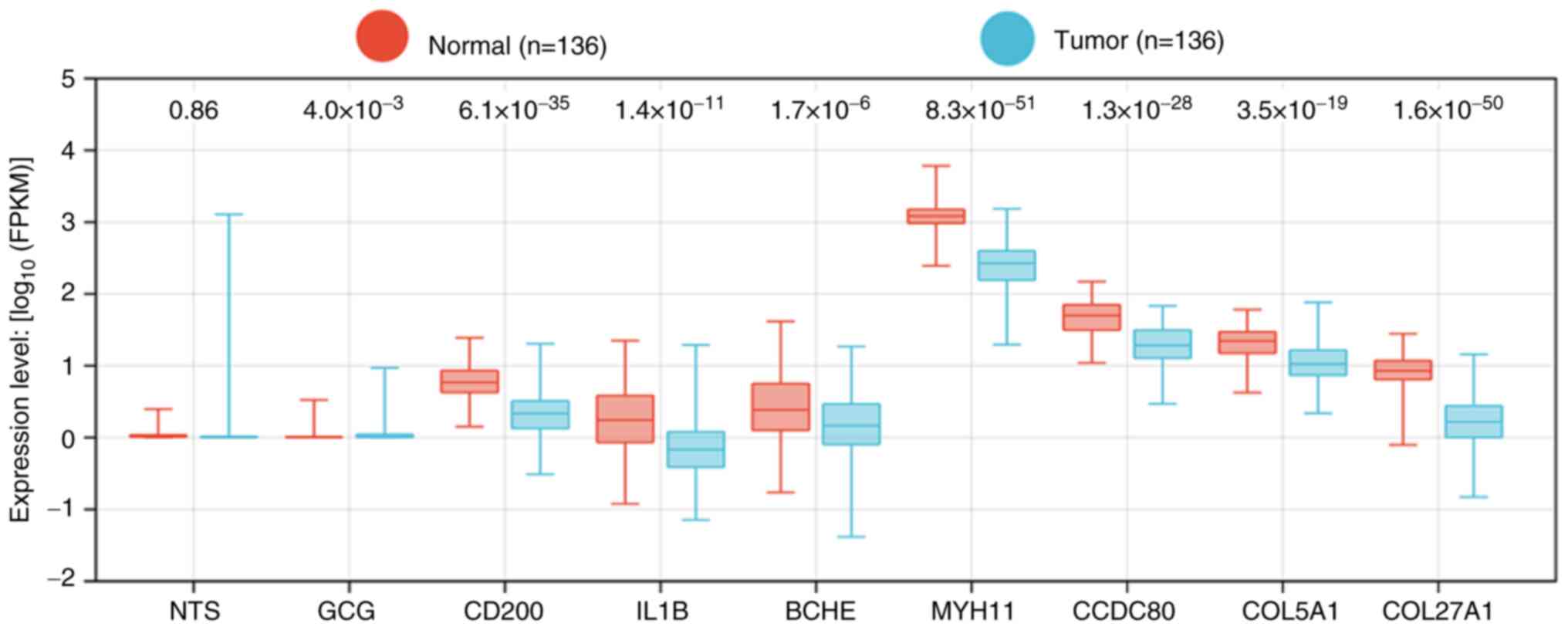

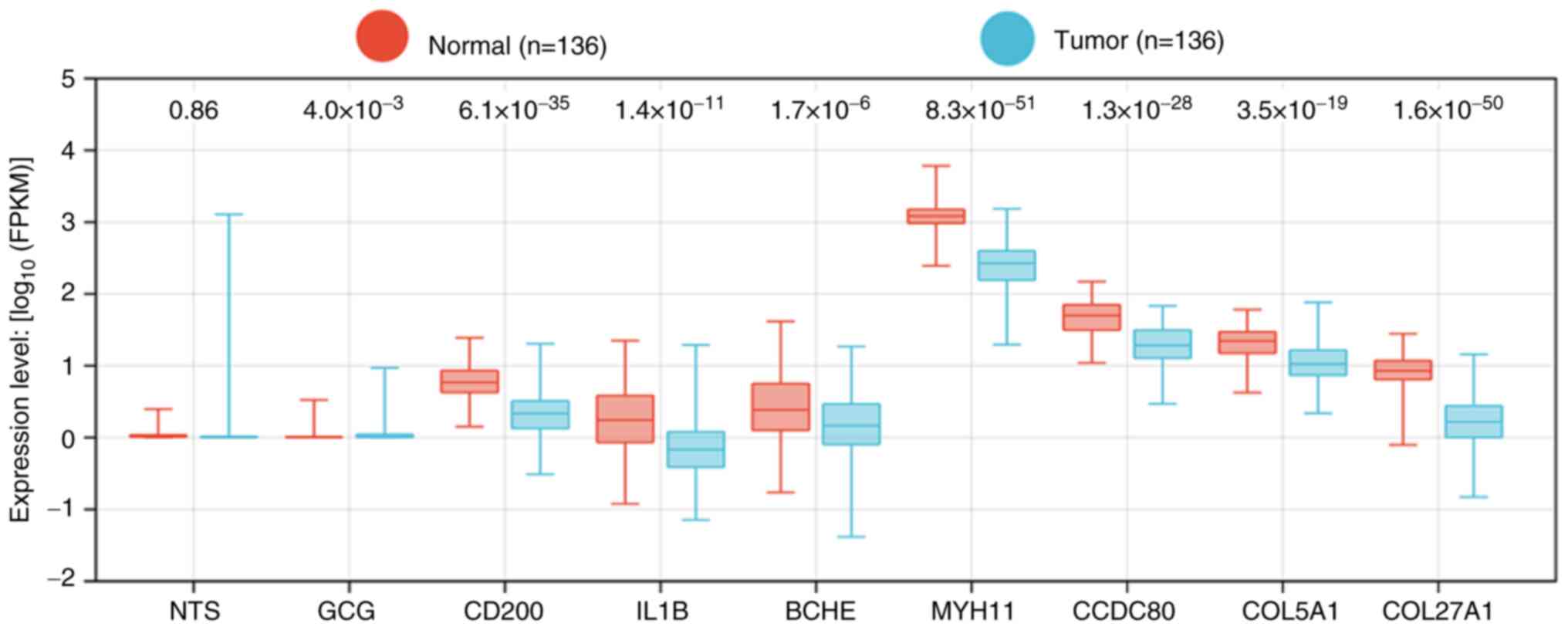

Hub genes influence PCa occurrence in

Chinese patients

Since TCGA predominantly represents Western

populations, the present study also investigated gene expression in

a Chinese cohort using microarray data from the CPGEA database.

Furthermore, 8 out of the 9 hub genes (excluding NT; P=0.86)

were significantly differentially expressed in Chinese patients

with PCa (Fig. 3). These findings

suggested that the identified hub genes are key to PCa occurrence

in Chinese populations.

| Figure 3.Expression levels of nine hub genes

from ADRGs in the CPGEA database. CPGEA, Chinese Prostate Cancer

Genome and Epigenome Atlas; ADRGs, antiandrogen drug resistance

genes; NTS, neurotensin; GCG, glucagon; IL1B, interleukin 1β; BCHE,

butyrylcholinesterase; CCDC80, coiled-coil domain containing 80;

COL5A1, collagen type V α 1 chain; COL27A1, collagen type XXVII α 1

chain; MYH11, myosin heavy chain 11; CD200, cluster of

differentiation 200. |

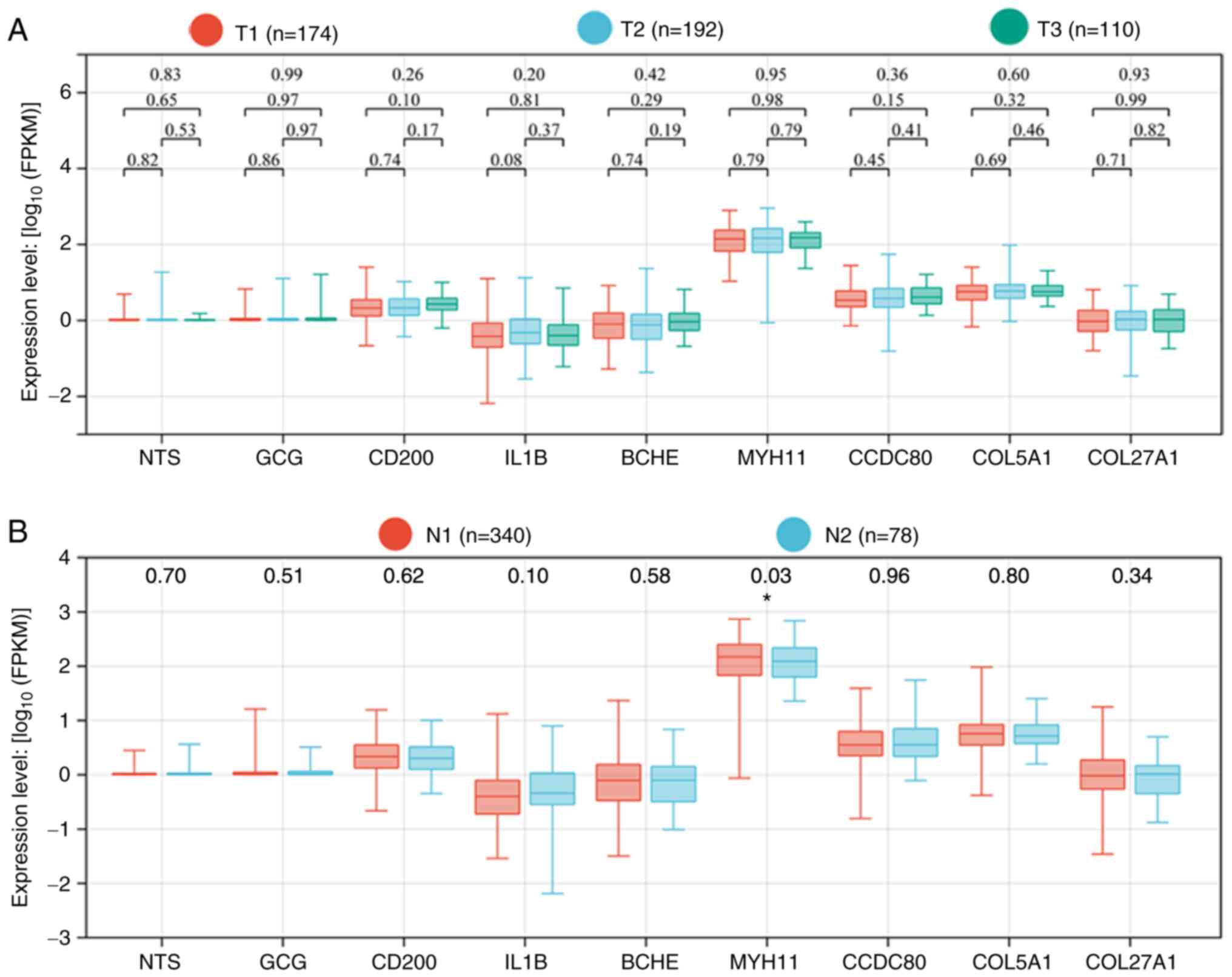

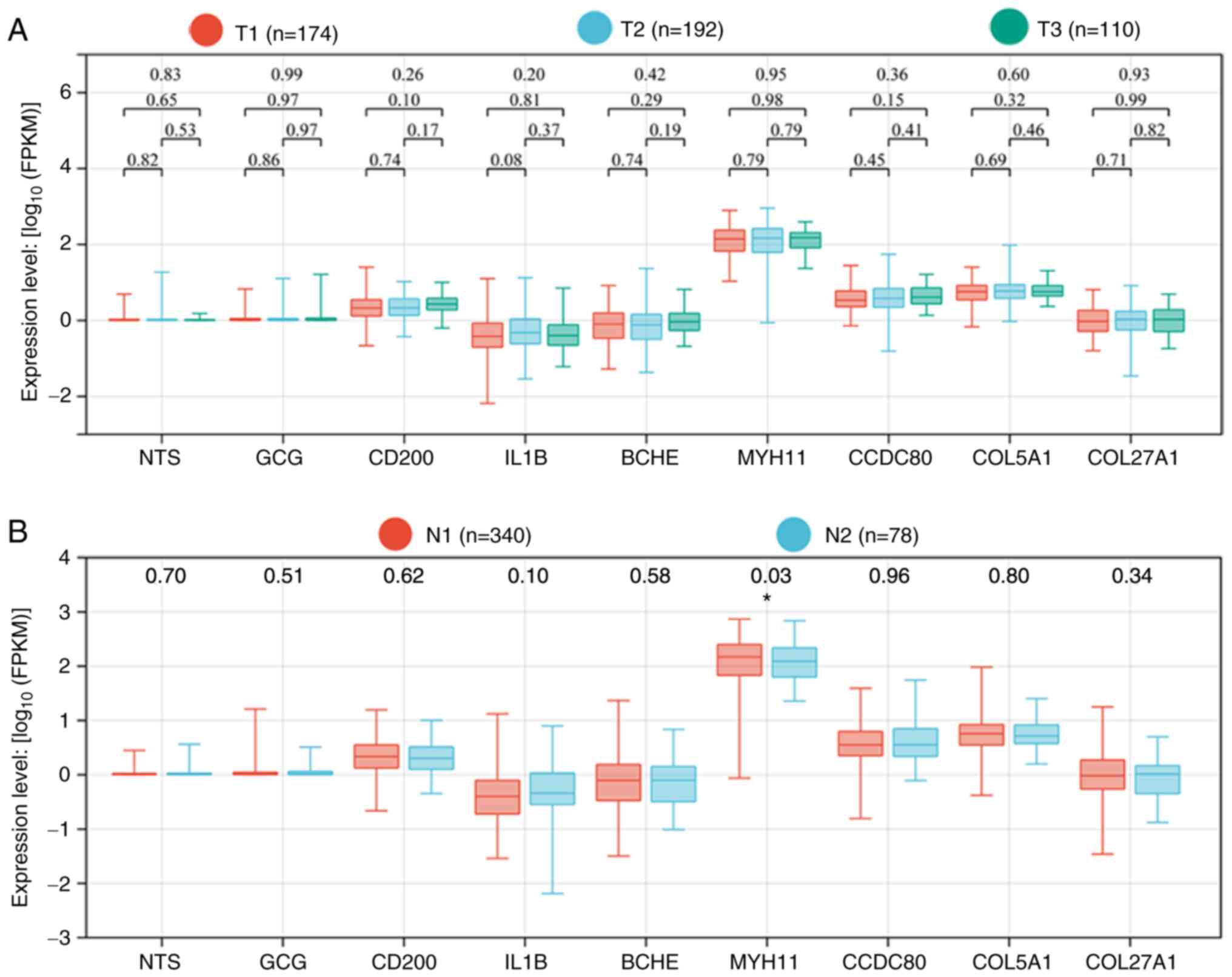

Hub genes influence PCa

progression

Tumor, lymph node, metastasis (TNM) staging is

widely used to evaluate tumor severity (29). Therefore, the present study examined

whether hub genes associated with antiandrogen resistance also

influenced PCa progression. RNA-sequencing data and clinical

information were obtained from TCGA. Since metastasis data were

unavailable for most patients, only T and N stages were analyzed.

Hub gene expression was not associated with the T stage (Fig. 4A). However, MYH11 expression

was significantly reduced in patients with lymph node metastasis

(P=0.03; Fig. 4B). Thus, in

addition to its role in PCa occurrence, MYH11 also appears to

affect disease progression.

| Figure 4.Expression levels of nine hub genes

from ADRGs in patients with PCa and different tumor stages (data

from TGCA). (A) T stage (B) N stage. *P<0.05. ADRGs,

antiandrogen drug resistance genes; PCa, prostate cancer; TGCA, The

Cancer Genome Atlas; T, tumor; N, lymph node; NTS, neurotensin;

GCG, glucagon; IL1B, interleukin 1β; BCHE, butyrylcholinesterase;

CCDC80, coiled-coil domain containing 80; COL5A1, collagen type V α

1 chain; COL27A1, collagen type XXVII α 1 chain; MYH11, myosin

heavy chain 11; CD200, cluster of differentiation 200. |

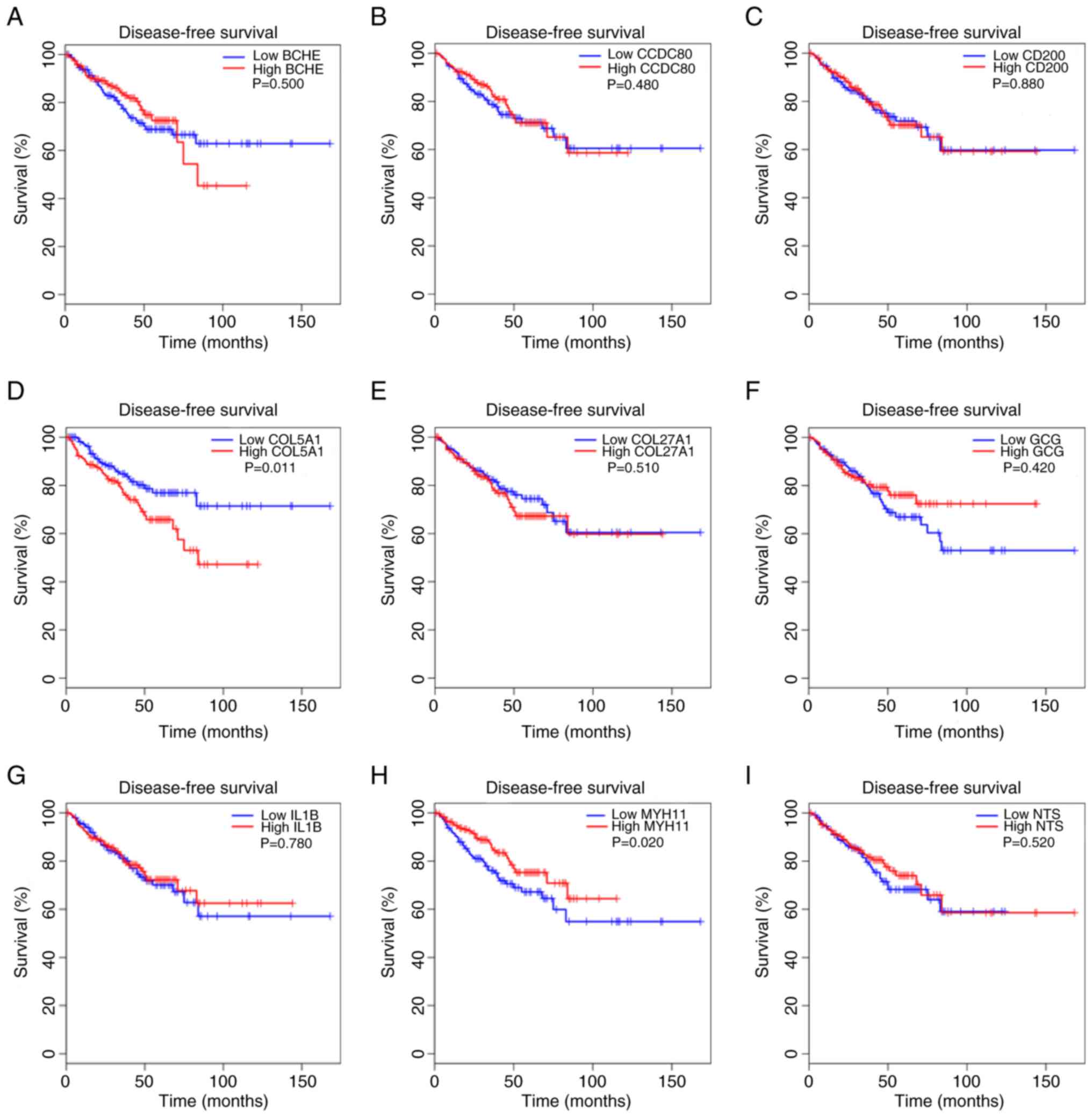

MYH11 influences DFS in patients with

PCa

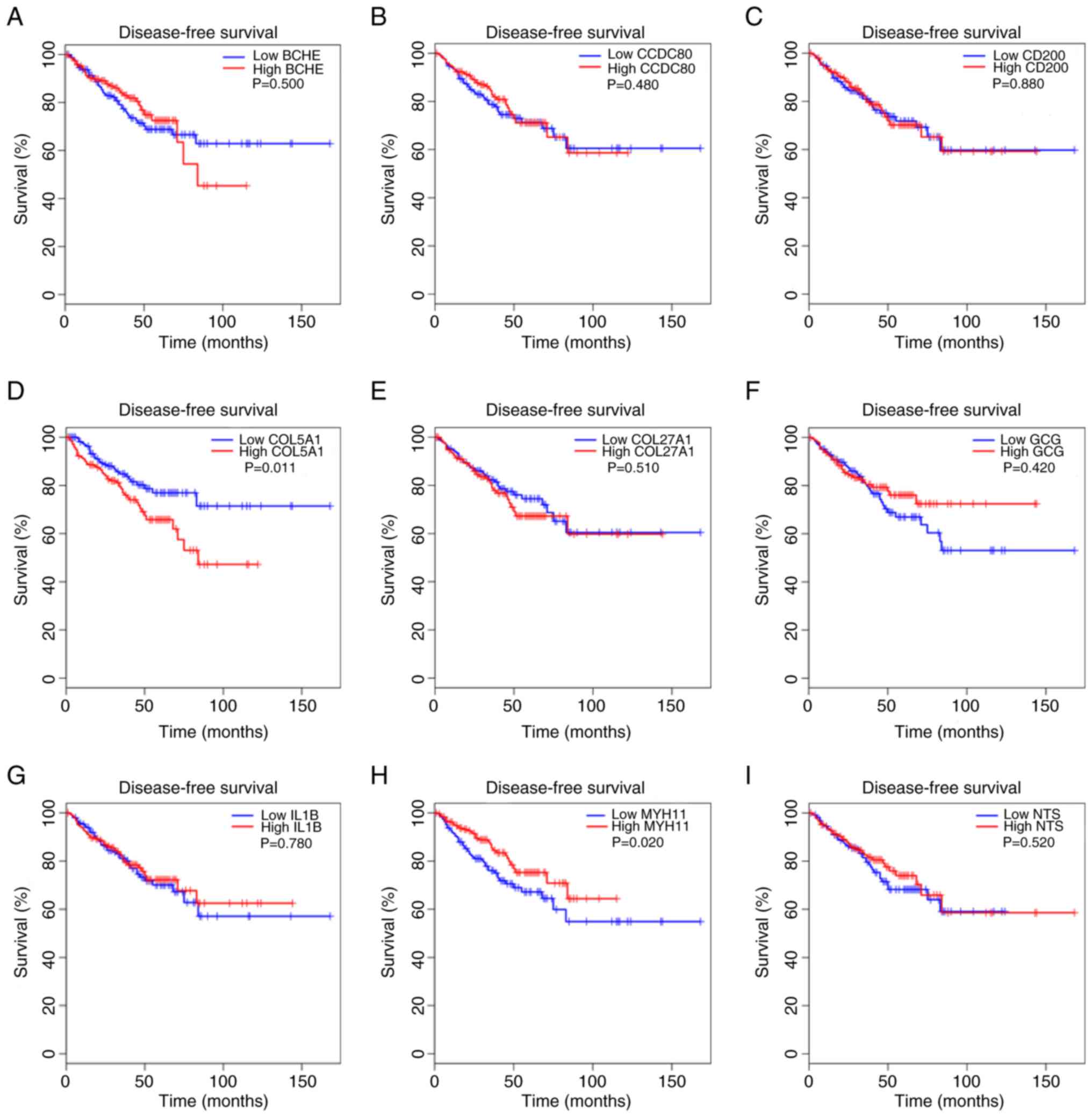

Next, the present study evaluated whether hub genes

were associated with patient survival. GEPIA analysis of TCGA data

was used to assess correlations between hub gene expression and

DFS. Only COL5A1 (P=0.011) and MYH11 (P=0.02)

expression significantly influenced DFS in patients with PCa

(Fig. 5). These results indicated

that MYH11 impacts both PCa progression and patient

survival.

| Figure 5.Association between the expression

levels of nine hub genes from ADRGs and DFS status from the GEPIA

online tool based on TCGA. (A) BCHE (B) CCDC80 (C) CD200 (D) COL5A1

(E) COL27A1 (F) GCG (G) IL1B (H) MYH11 (I) NTS. DFS, disease-free

survival; ADRGs, antiandrogen drug resistance genes; GEPIA, Gene

Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; TGCA, The Cancer Genome

Atlas; CD200, cluster of differentiation 200; BCHE,

butyrylcholinesterase; CCDC80, coiled-coil domain containing 80;

COL5A1, collagen type V α 1 chain; COL27A1, collagen type XXVII α 1

chain; GCG, glucagon, IL1B, interleukin 1 β; MYH11, myosin heavy

chain 11; NTS, neurotensin. |

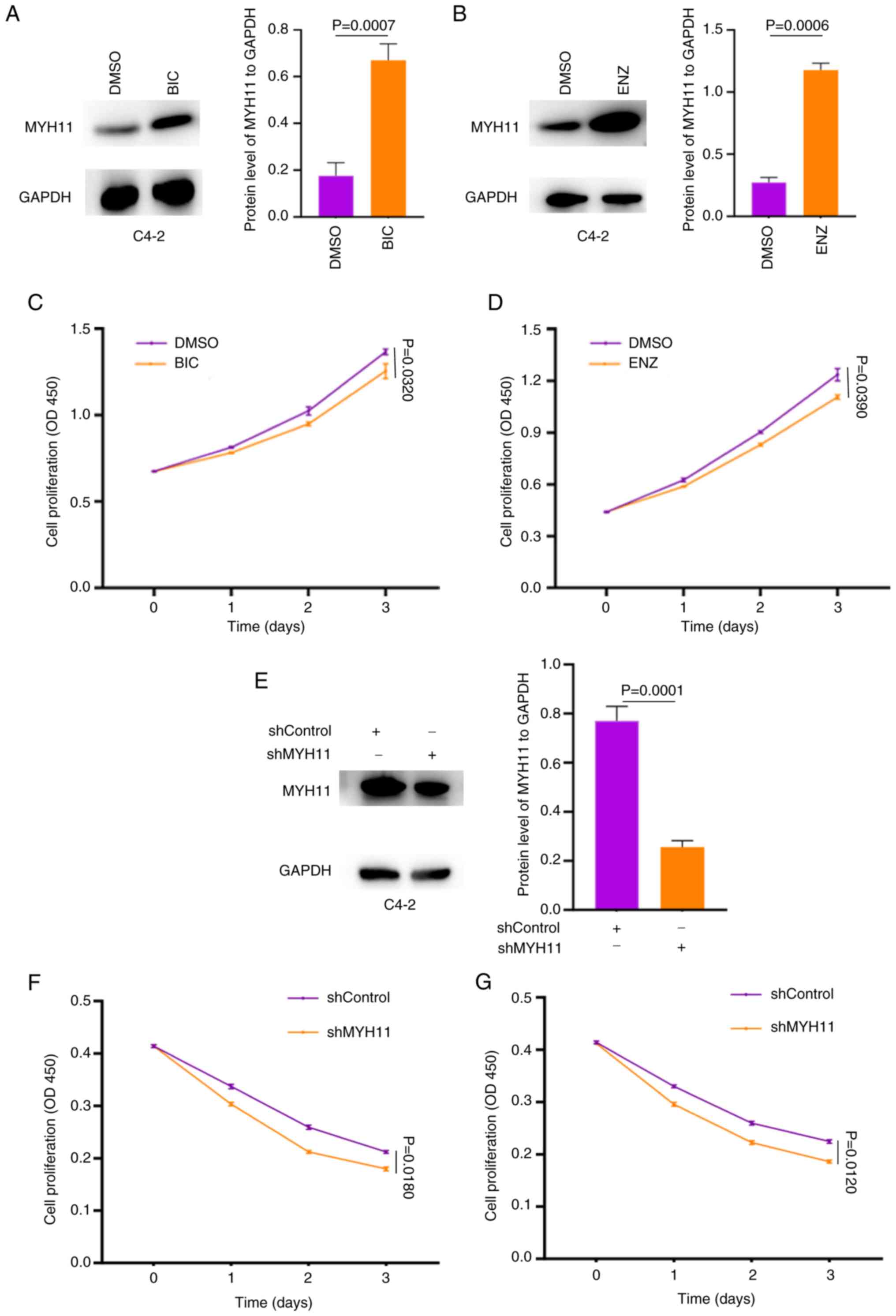

MYH11 is central to PCa cells

resistance to antiandrogen drugs in vitro

The present study observed that MYH11 was

upregulated in LNCaP cells resistant to BIC, ENZ and APN, and that

it influenced PCa occurrence, progression, and prognosis based on

multiple databases. Therefore, we hypothesized that MYH11

serves a key role in PCa development and resistance to antiandrogen

drugs. To further investigate this, the present study collected two

additional datasets, GSE189129 and GSE81796, which include

RNA-sequencing data from C4-2 cells resistant to ENZ. Consistent

with results from LNCaP cells, MYH11 expression was also

significantly increased in ENZ-resistant C4-2 cells (GSE136129;

P=5.47×10−7 and GSE81796; P=0.0274; Fig. S1). These findings suggested that

MYH11 may be key in mediating resistance to antiandrogen

drugs in PCa cells.

The present study next validated this function

experimentally. A shMYH11 lentivirus was constructed and transduced

into C4-2 cells, which were then treated with BIC or ENZ. First,

the present study identified MYH11 expression significantly

increased rapidly in C4-2 cells exposed to 40 µM BIC or ENZ for 10

days (BIC group, P=0.0007; ENZ group, P=0.006; Fig. 6A and B). Proliferation assays

demonstrated a significant reduction in cell proliferation after

treatment with different drugs (BIC group, P=0.0320; ENZ group,

P=0.0390; Fig. 6C and D). Knockdown

with shMYH11 lentivirus significantly reduced MYH11 protein

expression in C4-2 cells compared with shControl cells (P=0.0001;

Fig. 6E). When these cells were

subsequently treated with 80 µM BIC or ENZ, became more sensitive

to the drugs, indicating higher rates of cell death compared with

the cells treated by DMSO (BIC group, P=0.0160; ENZ group,

P=0.0120; Fig. 6F and G). Since

MYH11 was initially identified from LNCaP cells and these differ

biologically from C4-2 cells, the present study also performed

parallel analyses in LNCaP cells. In LNCaP cells, treatment with

BIC or ENZ significantly increased MYH11 expression and reduced

proliferation (BIC group, P=0.0001; ENZ group, P=0.0001; Fig. S2A-D). The shMYH11 lentivirus also

significantly decreased MYH11 expression in LNCaP cells (P=0.0001;

Fig. S2E), while shMYH11 knockdown

sensitized cells to drug treatment (BIC group, P=0.0180; ENZ group,

P=0.0160; Fig. S2F and G).

Together, these results indicate that MYH11 is key to determining

PCa cell sensitivity to antiandrogen drugs.

Discussion

The increasing life expectancy of men has

contributed to rising PCa morbidity (30). Improvements in health awareness and

the widespread use of prostate-specific antigen screening have

facilitated early detection (31).

Nonetheless, aggressive treatment is warranted to achieve improved

therapeutic effects. Among the available treatments, androgen

deprivation therapy (ADT), which lowers androgen levels or

decreases AR expression, has demonstrated therapeutic efficacy and

can prolong survival (6). However,

most patients (86%) develop resistance to ADT ≤2 years (32), highlighting the need to elucidate

the mechanisms underlying antiandrogen drug resistance.

BIC, ENZ and APN are three antiandrogen drugs with

confirmed therapeutic benefits in PCa (8). These agents markedly prolong median

survival in patients (33–35); however, resistance eventually

develops and the mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Genetic

alterations are considered to be a key contributing factor. For

example, loss of the chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 1

gene has been associated with antiandrogen resistance (36). Furthermore, changes in neuregulin 1

expression may alter the tumor microenvironment and promote

resistance (37). Collectively,

these findings emphasize the importance of genetic alterations in

driving resistance to antiandrogen drugs.

Due to the role of genetic alterations in

resistance, the present study aimed to identify potential hub genes

involved in this process. RNA-sequencing analysis of the GSE211781

dataset identified nine hub genes among 54 ADRGs that may be key

for resistance. Further analysis indicated that several of these

genes also serve roles in PCa occurrence. MYH11 emerged as a

particularly key gene associated with PCa occurrence, progression

and prognosis. Two PCa cell lines, LNCaP and C4-2, were

subsequently used to examine whether MYH11 could influence

cellular sensitivity to antiandrogen drugs. Since C4-2 cells were

derived from bone metastasis of LNCaP in nude mice, they represent

a castration-resistant line with distinct biological features

(38). Here, the present study

found that although the rate of cell proliferation slowed down

slightly in the cells of MYH11 knockdown compared with the

normal control, there were still statistically significant

differences for C4-2 cells (BIC group, P=0.016; ENZ group, P=0.012)

and LNCaP cells (BIC group, P=0.018; ENZ group, P=0.016). So, the

present study identified that MYH11 modulated the

sensitivity of both LNCaP and C4-2 cells to BIC and ENZ, suggesting

that MYH11 can be an indicator for predicting PCa to

antiandrogen drugs resistance. However, the present study verified

the function of MYH11 only in vitro and did not investigate

underlying mechanisms. Due to the complexity of drug resistance,

including the possibility of acquired mechanisms, these results

require additional confirmation in future studies.

MYH11, encoded by the MYH11 gene, is a smooth

muscle myosin belonging to the myosin heavy chain family (39). Mutations in MYH11 have been

implicated in the development of several cancer types (40). For example, MYH11

hypermethylation promotes gastric cancer progression (41) and the gene is key in acute myeloid

leukemia (42,43). MYH11 also serves as a

biomarker for the prediction of lung cancer prognosis (39). Furthermore, MYH11 has been

associated with PCa development: Somatic mutations in MYH11

contribute to PCa occurrence and predict disease progression

(44,45).

In the present study however, some unexpected

phenomenon were observed: First, MYH11 was downregulated in

the tissues of patients with PCa but demonstrated increased

expression in PCa cells treated with antiandrogen drugs. Several

factors may explain this discrepancy. First, biological complexity

and interindividual variability can produce different results in

tissues compared with cell lines. Second, drug treatment can alter

gene expression patterns. For instance, previous studies have

reported that antiandrogen drugs initially suppress AR expression

but eventually increase it through cellular adaptation (5,46). A

similar mechanism may underlie the regulation of MYH11. Another

phenomenon noted in the present study is that the cells without

MYH11 knockdown would still proliferate after treatment with

BIC or ENZ but exhibited decreased proliferation after MYH11

knockdown. This could be because in PCa cells with MYH11

expression, proteins such as AR which affect the function of BIC or

ENZ still have normal expression but after MYH11 knockdown,

the expression of these proteins may decrease. After a protein such

as AR decreases, the cells would be more sensitive to antiandrogen

drugs and proliferate at a decreased rate. Although, to the best of

our knowledge, no direct studies have reported an association

between MYH11 and AR in PCa, a previous study in penile tissue

identified such a relationship (47), suggesting a possible association in

other tissues. In the present study, drugs that inhibited AR

expression also affected MYH11 expression, supporting the idea of a

regulatory association between MYH11 and AR in PCa. Cells with

MYH11 knockdown decreased after treated by BIC or ENZ which

further indicated that MYH11 may influence AR expression in PCa

cells. These findings suggest that MYH11 could be a therapeutic

target for drug-resistant PCa.

However, the present study had several limitations.

First, the present study identified 54 ADRGs as potentially key for

resistance to antiandrogen drugs in PCa and PPI network analysis

highlighted nine hub genes. The functional roles of the remaining

ADRGs, however, remain to be elucidated. Second, the present

examined gene expression using RNA-sequencing data from different

databases; however, these findings were not validated in clinical

samples. The mechanism of MYH11 in PCa therefore requires further

experimental investigation in the future. Third, although

MYH11 expression was generally lower in patients with PCa,

higher MYH11 expression patients were associated with

improved DFS compared with patients with low MYH11 level.

This apparent contradiction warrants additional study. Lastly, the

present functional analysis was performed using bioinformatics

approaches and the mechanisms by which these genes influence PCa

development and drug resistance remain to be elucidated.

Additional experiments should be carried out in the

future to investigate the mechanism of MYH11, including its

interactions with AR signaling. For example, one group of C4-2

cells may be treated with shMYH11 lentivirus and another group with

ENZ to make these cells resistant to ENZ. Subsequently,

RNA-sequencing could be performed and the differentially expressed

genes could be obtained. A pathway analysis could be performed to

identify the genes associated with both BIC and ENZ resistance.

After identifying these genes, basic experiments such as PCR,

western blotting should be performed to further identify the

association of potential genes with MYH11. Furthermore, validation

in additional PCa cell lines such as 22Rv1 and vertebral-cancer of

the prostate is necessary to strengthen the generalizability of the

findings in the future. Despite these limitations, the present

study suggests that MYH11 serves a key role in resistance to

antiandrogen drugs and may potentially serve as a predictive

indicator for PCa development and therapeutic response in the

future.

In summary, the present study identified nine hub

genes among 54 ADRGs from the GSE211781 dataset, with MYH11

emerging as a key indicator for the prediction of PCa occurrence,

progression and also key for PCa cells resistant to antiandrogen

drugs.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LP and JS designed the study and got the data from

public databases. LP and ZL analyzed the data from pubic databases

and wrote the paper. GX and CC conducted all the experiments

including cell culture, western blot and CCK-8 assay. CC

contributed to the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript.

CC and LP confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fu ZT, Guo XL, Zhang SW, Zheng RS, Zeng

HM, Chen R, Wang SM, Sun KX, Wei WW and He J: Statistical analysis

of incidence and mortality of prostate cancer in China, 2015.

Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 42:718–722. 2020.(In Chinese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sekhoacha M, Riet K, Motloung P, Gumenku

L, Adegoke A and Mashele S: Prostate cancer review: Genetics,

diagnosis, treatment options, and alternative approaches.

Molecules. 27:57302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Debes JD and Tindall DJ: Mechanisms of

androgen-refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 351:1488–1490.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Watson PA, Arora VK and Sawyers CL:

Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors

in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:701–711. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ross RW, Xie W, Regan MM, Pomerantz M,

Nakabayashi M, Daskivich TJ, Sartor O, Taplin ME, Kantoff PW and Oh

WK: Efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with

advanced prostate cancer: Association between Gleason score,

prostate-specific antigen level, and prior ADT exposure with

duration of ADT effect. Cancer. 112:1247–1253. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Garje R, Chennamadhavuni A, Mott SL,

Chambers IM, Gellhaus P, Zakharia Y and Brown JA: Utilization and

outcomes of surgical castration in comparison to medical castration

in metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer.

18:e157–e166. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Patke R, Harris AE, Woodcock CL, Thompson

R, Santos R, Kumari A, Allegrucci C, Archer N, Gudas LJ, Robinson

BD, et al: Epitranscriptomic mechanisms of androgen signalling and

prostate cancer. Neoplasia. 56:1010322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kolvenbag GJ and Nash A: Bicalutamide

dosages used in the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate.

39:47–53. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Scott LJ: Enzalutamide: A review in

Castration-resistant prostate cancer. Drugs. 78:1913–1924. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Clegg NJ, Wongvipat J, Joseph JD, Tran C,

Ouk S, Dilhas A, Chen Y, Grillot K, Bischoff ED, Cai L, et al:

ARN-509: A novel antiandrogen for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer

Res. 72:1494–1503. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen X, Li H, Liu B, Wang X, Zhou W, Wu G

and Xu C: Identification and validation of MSMB as a critical gene

for prostate cancer development in obese people. Am J Cancer Res.

13:1582–1593. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen X, Ma J, Wang X, Zi T, Qian D, Li C

and Xu C: CCNB1 and AURKA are critical genes for prostate cancer

progression and castration-resistant prostate cancer resistant to

vinblastine. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:11061752022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li H, Wang X, Zhai M, Xu C and Chen X:

Exploration of the influence of GOLGA8B on prostate cancer

progression and the resistance of castration-resistant prostate

cancer to cabazitaxel. Discov Oncol. 15:1522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ma J, Qin X, Le W, Chen X, Wang X and Xu

C: Identification of BBC3 as a novel indicator for predicting

prostate cancer development and olaparib resistance. Discov Oncol.

15:4962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen X, Wu Y, Wang X, Xu C, Wang L, Jian

J, Wu D and Wu G: CDK6 is upregulated and may be a potential

therapeutic target in Enzalutamide-resistant castration-resistant

prostate cancer. Eur J Med Res. 27:1052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P,

Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH,

Sherman PM, Holko M, et al: NCBI GEO: Archive for functional

genomics data sets-update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D991–D995. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Blum A, Wang P and Zenklusen JC: SnapShot:

TCGA-Analyzed tumors. Cell. 173:5302018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li J, Xu C, Lee HJ, Ren S, Zi X, Zhang Z,

Wang H, Yu Y, Yang C, Gao X, et al: A genomic and epigenomic atlas

of prostate cancer in Asian populations. Nature. 580:93–99. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chawla S, Rockstroh A, Lehman M, Ratther

E, Jain A, Anand A, Gupta A, Bhattacharya N, Poonia S, Rai P, et

al: Gene expression based inference of cancer drug sensitivity. Nat

Commun. 13:56802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

He Y, Wei T, Ye Z, Orme JJ, Lin D, Sheng

H, Fazli L, Jeffrey Karnes R, Jimenez R, Wang L, et al: A

noncanonical AR addiction drives enzalutamide resistance in

prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 12:15212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shah S, Carriveau WJ, Li J, Campbell SL,

Kopinski PK, Lim HW, Daurio N, Trefely S, Won KJ, Wallace DC, et

al: Targeting ACLY sensitizes castration-resistant prostate cancer

cells to AR antagonism by impinging on an ACLY-AMPK-AR feedback

mechanism. Oncotarget. 7:43713–43730. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: Limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C and

Zhang Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:W98–W102.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M,

Wyder S, Simonovic M, Santos A, Doncheva NT, Roth A, Bork P, et al:

The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled Protein-protein

association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res.

45:D362–D368. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chen X, Ma J, Xu C, Wang L, Yao Y, Wang X,

Zi T, Bian C, Wu D and Wu G: Identification of hub genes predicting

the development of prostate cancer from benign prostate hyperplasia

and analyzing their clinical value in prostate cancer by

bioinformatic analysis. Discov Oncol. 13:542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen X, Li H, Xu C, Wang X, Wu G, Li C and

Wu D: CYP19A1 is downregulated by BRD4 and suppresses

castration-resistant prostate cancer cell invasion and

proliferation by decreasing AR expression. Am J Cancer Res.

13:4003–4020. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Paner GP, Stadler WM, Hansel DE, Montironi

R, Lin DW and Amin MB: Updates in the eighth edition of the

Tumor-Node-Metastasis staging classification for urologic cancers.

Eur Urol. 73:560–569. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, Mariotto A, Szabo

A, Falcon S, Wegelin J, DiTommaso D, Karnofski K, Gulati R, Penson

DF and Feuer E: Quantifying the role of PSA screening in the US

prostate cancer mortality decline. Cancer Causes Control.

19:175–181. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Arsov C, Winter C, Rabenalt R and Albers

P: Current second-line treatment options for patients with

castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) resistant to docetaxel.

Urol Oncol. 30:762–771. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fradet Y: Bicalutamide (Casodex) in the

treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 4:37–48.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Armstrong AJ, Azad AA, Iguchi T,

Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Alcaraz A,

Alekseev B, Shore ND, et al: Improved survival with enzalutamide in

patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 40:1616–1622. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, Oudard S,

Hadaschik BA, Graff JN, Olmos D, Mainwaring PN, Lee JY, Uemura H,

et al: Apalutamide treatment and Metastasis-free survival in

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 378:1408–1418. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang Z, Zhou C, Li X, Barnes SD, Deng S,

Hoover E, Chen CC, Lee YS, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al: Loss of CHD1

Promotes heterogeneous mechanisms of resistance to AR-Targeted

therapy via chromatin dysregulation. Cancer Cell. 37:584–598.e11.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang Z, Karthaus WR, Lee YS, Gao VR, Wu

C, Russo JW, Liu M, Mota JM, Abida W, Linton E, et al: Tumor

Microenvironment-derived NRG1 promotes antiandrogen resistance in

prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 38:279–296.e9. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Spans L, Helsen C, Clinckemalie L, Van den

Broeck T, Prekovic S, Joniau S, Lerut E and Claessens F:

Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses of LNCaP and C4-2B

prostate cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 9:e900022014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Nie MJ, Pan XT, Tao HY, Xu MJ, Liu SL, Sun

W, Wu J and Zou X: Clinical and prognostic significance of MYH11 in

lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 19:3899–3906. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Islam T, Rahman R, Gov E, Turanli B,

Gulfidan G, Haque A, Arga KY and Haque Mollah N: Drug targeting and

biomarkers in head and neck cancers: Insights from systems biology

analyses. OMICS. 22:422–436. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang J, Xu P, Hao Y, Yu T, Liu L, Song Y

and Li Y: Interaction between DNMT3B and MYH11 via hypermethylation

regulates gastric cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 21:9142021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cho BS, Min GJ, Park SS, Park S, Jeon YW,

Shin SH, Yahng SA, Yoon JH, Lee SE, Eom KS, et al: Prognostic

values of D816V KIT mutation and Peri-transplant CBFB-MYH11 MRD

monitoring on acute myeloid leukemia with CBFB-MYH11. Bone Marrow

Transplant. 56:2682–2689. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ishikawa Y, Kawashima N, Atsuta Y, Sugiura

I, Sawa M, Dobashi N, Yokoyama H, Doki N, Tomita A, Kiguchi T, et

al: Prospective evaluation of prognostic impact of KIT mutations on

acute myeloid leukemia with RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11. Blood

Adv. 4:66–75. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Alhopuro P, Karhu A, Winqvist R, Waltering

K, Visakorpi T and Aaltonen LA: Somatic mutation analysis of MYH11

in breast and prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 8:2632008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Huang Y, Cao Q, Song Z, Ruan H, Wang K,

Chen K and Zhang X: The identification of key gene expression

signature in prostate cancer. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr.

30:153–168. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Aurilio G, Cimadamore A, Mazzucchelli R,

Lopez-Beltran A, Verri E, Scarpelli M, Massari F, Cheng L, Santoni

M and Montironi R: Androgen receptor signaling pathway in prostate

cancer: From genetics to clinical applications. Cells. 9:26532020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Okumu LA, Bruinton S, Braden TD, Simon L

and Goyal HO: Estrogen-induced maldevelopment of the penis involves

down-regulation of myosin heavy chain 11 (MYH11) expression, a

biomarker for smooth muscle cell differentiation. Biol Reprod.

87:1092012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|