Introduction

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) is an

aggressive subtype of soft tissue sarcomas, characterized by a

limited response to therapy (1).

However, UPS shows higher immunogenicity compared to other sarcoma

subtypes, which supports the interest in immunotherapy for this

cancer (2). Immunotherapy has

changed oncological treatment in recent years, with several

patients now receiving it as a first-line therapy (3–6). A

number of these therapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors,

demonstrated notable outcomes for several patients (7). However, for numerous patients,

particularly those with solid tumors, immunotherapy still fails and

traditional therapeutic modalities, including cytotoxic

chemotherapy, need to be used in following therapy lines (8,9). In

addition, novel algorithms of oncological treatment may combine

multiple therapeutic approaches, such as chemotherapy and

immunotherapy or radiotherapy and immunotherapy (10,11).

However, despite the progress in the field, how therapeutic

combinations may affect each other and the overall therapeutic

efficacy remain to be elucidated. One of the key effector molecules

associated with immunotherapy is interferon γ (IFNγ) (12). This cytokine is primarily produced

by cytotoxic lymphocytes, including cytotoxic cluster of

differentiation(CD)8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells

and NK T cells, which serve a key role in eliminating cancer cells

(13,14). Thus, any treatment leading to the

effective removal of cancer cells by cytotoxic lymphocytes is

likely to be associated with the production of IFNγ and its

collateral impact not only on immune cells (15,16)

but also on other cells in the tumor microenvironment, including

cancer cells (17–19). Due to the impact of IFNγ on cancer

cells, it is difficult to determine how it can affect the efficacy

of individual therapeutic approaches or their combinations.

Previous studies have reported that IFNγ signatures, patterns of

genes, proteins or cellular changes that become activated in

response to this cytokine, are frequently associated with enhanced

responses to immunotherapy, and elevated IFNγ levels are typically

associated with immunotherapy efficacy (20,21).

Immunotherapy may sensitize tumors to subsequent chemotherapy

(22,23), yet it may also promote resistance to

chemotherapy (24,25). This duality implies that IFNγ

signatures may likewise exert dual, context-dependent roles across

these therapeutic modalities.

UPS is commonly linked to increased infiltration of

immune cells (26), which often

correlates with IFNγ signatures (27). However, the specific role of IFNγ in

UPS and its implications for immunotherapy and chemotherapy remain

unclear. To address this, the present study examined a recently

developed, primary tumor-derived, highly transformed, UPS cell line

termed JBT19 (28). The present

study further explored the mechanism by which prolonged exposure to

IFNγ influences the sensitivity of the cell line to cytotoxic

chemotherapy and antitumor immunity.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, cell culture and

IFNγ-mediated phenotype remodeling

The JBT19 cell line, which originated from a UPS,

high-grade soft tissue sarcoma, was established from the primary

tumor of a 65-year-old male patient, whose tumor was surgically

removed before any other therapeutic interventions and the cell

line was subsequently developed using tumor

fragmentation-dissociation techniques (28). After 30 passages and >30 months

in cell culture, the cell line already exhibited a high population

uniformity and was subsequently characterized (28). In the present study, the JBT19 cell

line and its green fluorescent protein (GFP)-transfected form

(JBT19-GFP) were used after 52 passages and after >35 months in

cell culture. The prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3 was used as an

epithelial-origin-derived tumor cell line model (29). Cells were adherently cultured (37°C;

5% CO2) in RPMI 1640-based FBS-containing complete

medium (KM+ medium). KM+ medium consisted of RPMI 1640 medium

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS

(non-heat-inactivated; HyClone™; Cytiva), 100 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin, 2 mM GlutaMax, 1 mM sodium pyruvate

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1 mM non-essential amino acid

mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in tissue culture flasks or

plates (TPP Techno Plastic Products AG or SARSTEDT AG & Co.

KG). The cells were passaged as previously described using

trypsin/EDTA solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and KM+

medium (28). To reprogram the

phenotype of JBT19 cells, the adherent cultured JBT19 cells were

supplemented with 200 ng/ml IFNγ (PeproTech, Inc.; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for the indicated times. Every 2–4 days, the

cells were supplemented with fresh KM+ medium and IFNγ (200 ng/ml).

To reverse the phenotype of IFNγ-reprogrammed cells, the cells were

extensively rinsed (>3 times) with fresh KM+ medium and cultured

for the indicated times. The cells were supplemented with fresh KM+

medium every 2–4 days and/or passaged.

Phenotypic characterization

To evaluate the expression levels of cell surface

markers in JBT19 cells, the cells were rinsed with PBS and

harvested using trypsin/EDTA solution and KM+ medium. The harvested

cells were rinsed with PBS supplemented with 2 mM EDTA (PBS/E) and

stained on ice for 30–60 min with the following fluorophore-labeled

antibodies: Anti-CD44-Phycoerythrin (PE; clone MEM-263; cat. no.

1P-341-T100; EXBIO Praha, a.s.), anti-CD47-allophycocyanin (APC;

clone CC2C6; cat. no. 323124; BioLegend, Inc.), anti-CD95 (Fas)-APC

(clone DX2; cat.# 305611; BioLegend, Inc.), anti-fibroblast

activation protein (FAP)-α-PE (clone 427819; cat.# FAB3715P-100;

R&D Systems, Inc.), anti-CD274 (PD-L1)-APC (clone MIH3; cat.#

374514; BioLegend, Inc.), anti-human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-ABC

[major histocompatibility complex (MHC)]-(I)-PE (clone W6/32; cat.#

311406; BioLegend, Inc.) and HLA-DP, DQ, DR (MHC-II)-APC (clone

Tü39; cat.# 361714; BioLegend, Inc.). The stained cells were rinsed

with PBS/E and supplemented with 100 ng/ml DAPI (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) shortly before cell analysis. To evaluate the

expression levels of intracellular cell markers, the harvested

cells were stained on wet ice using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead

Cell Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), fixed and overnight

permeabilized as previously described (30). Cells were then stained on wet ice

with the following fluorophore-labeled antibodies: Anti-Ki-67-PE

(clone Ki-67; cat. no. 1P-155-T100; EXBIO Praha, a.s.),

anti-multidrug resistance (MDR)-1-PE (CD243, clone UIC2; cat.#

1P-764-T100; EXBIO Praha, a.s.), anti-B-cell lymphoma (Bcl)-2-PE

(clone Bcl-2/100; cat.# 556535; Becton, Dickinson and Company) and

anti-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1-Alexa

Fluor 647 (clone 1/STAT1; cat.# 558560; Becton, Dickinson and

Company). After staining, cells were rinsed with PBS/E, and the

surface of the cells or intracellularly stained cells were analyzed

with a FACSAria II or FACSFortesa flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson

and Company). The acquired data were processed using FlowJo

software (version 10.10.0; FlowJo LLC; BD Biosciences). The gating

strategy used fluorescence minus one staining.

MTT assay, cell cycle assay and

annexin V analysis

The cytotoxic impact of treating the cell line with

docetaxel, doxorubicin (Selleck Chemicals) or mitomycin C

(MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA), was determined using the MTT assay

(MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). Briefly, flat-bottom 96-well-cultured

adherent JBT19 cells (5,000–20,000 cells/well) were treated with

the indicated concentrations of docetaxel, doxorubicin or mitomycin

C for 3 days. The cell cultures were then supplemented with 0.5

mg/ml MTT substrate (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA) and cultured for 3

h. The supernatant was removed, and the insoluble formazan

dissolved with acidified isopropanol (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA).

The absorbance was acquired at 570 nm and referenced at 630 nm. The

acquired data were processed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.2.0;

Dotmatics) to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration

(IC50). Cell cycle analysis was performed as described

previously using PI staining (31),

with the exception that the data were analyzed using the

Dean/Jett/Fox algorithm

(docs.flowjo.com/flowjo/experiment-based-platforms/cell-cycle-univariate/)

with FlowJo software (version 10.10.0; FlowJo LLC; BD Biosciences).

Annexin V staining was performed as described previously (32) using annexin V-FITC (cat. no.

EXB0024; EXBIO Praha, a.s.).

Preparation of JBT19-reactive

lymphocytes

The source cell material were buffy coats from 4

healthy blood donor volunteers obtained from the Institute of

Hematology and Blood Transfusion (Prague, Czech Republic). This

material was used to isolate and cryopreserve peripheral blood

mononuclear cells (PBMCs) as previously described (30,33).

The volunteers provided a prior signed written informed consent for

the use of the biological material for research. The research

adhered to the ethics standards of the institutional research

committee and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

University Hospital Motol in Prague (approval no. EK-602.4/22;

Prague, Czech Republic). The research was performed in compliance

with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The

JBT19-reactive lymphocytes were produced as described previously

(28) with minor modifications.

Briefly, the cryopreserved PBMCs were reconstituted overnight

(2–3×106 cells/ml) in RPMI 1640-based human

serum-containing complete medium [lympho medium (LM), consisting of

RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 5%

human serum (One Lambda, Inc.; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

other non-serum supplements as in KM+ medium] supplemented with

human IL-2 (500 IU/ml; PeproTech, Inc.; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The reconstituted cells were harvested, pelleted and

reconstituted in fresh LM with 500 IU/ml IL-2 at 4×106

cells/ml. The cells were then combined at a 1:1 ratio with

trypsin/EDTA-harvested and UV-inactivated (312 nm; 2.55

J/cm2) JBT19 cells that were previously treated or not

with 200 ng/ml human IFNγ for 7 days (1×106 cells/ml)

[final ratio, 4:1 (PBMC/JBT19)]. The combined cells were cultured

in a flat-bottom 48-well plate well (Nalgene; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). On days 3, 5 and 6, the cell cultures were

hemi-depleted and supplemented with fresh LM and 500 IU/ml IL-2. On

day 7, the cell cultures were transferred to a flat-bottom 12-well

plate well (Nalgene; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

supplemented with an equal volume of fresh LM and 500 IU/ml IL-2.

On days 10 and 11, the cell cultures were hemi-depleted and

supplemented with fresh LM and 500 IU/ml of IL-2. On day 12, the

cells were analyzed and/or cryopreserved.

Rapid expansion protocol (REP) for

JBT19-reactive lymphocytes

The 12-day cryopreserved cell cultures enriched with

lymphocytes reactive to JBT19 cells or IFNγ-treated JBT19 cells

were reconstituted as aforementioned in LM with 500 IU/ml IL-2. The

reconstituted cells were then large-scale expanded for 14 days

using an REP as previously described (34), with the exception that following the

initial IL-2 concentration of 4,000 IU/ml, the cells were next

cultured with 2,000 IU/ml IL-2. On day 14, the large-scale expanded

cells were analyzed and/or cryopreserved.

Analyses of JBT19-reactive

lymphocytes

The cultured lymphocytes (enriched or large-scale

expanded) were analyzed with small modifications using procedures

described previously (28).

Briefly, the cultured lymphocytes were harvested, pelleted and

resuspended in fresh LM with 500 IU/ml IL-2 at 4×106

cells/ml. The lymphocytes were then combined at a 1:1 ratio with

trypsin/EDTA-harvested JBT19 cells treated or not with 200 ng/ml

IFNγ for 7 days [1×106 cells/ml; final ratio, 4:1 of

lymphocytes (effector)/JBT19 (target)]. The combined cells were

then transferred to a U-bottom 96-well plate (Nalgene; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and cultured (stimulated) at 37°C in the

presence of 5% CO2. After 1 h, the cells were

supplemented with Brefeldin A (BioLegend, Inc.) to prevent cytokine

secretion from the cells and cultured for an additional 4 h. The

cells were transferred to a V-bottom 96-well plate (Nalgene; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), pelleted, rinsed with PBS/E and stained

on wet ice with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The stained cells were next fixed,

overnight permeabilized and stained on wet ice with

anti-CD3-peridinin-chlorophyll-protein-cyanine (Cy)5.5 (clone SK7;

cat. no. T9-173-T100), anti-CD4-PE-Cy7 (clone MEM-241; cat. no.

T7-359-T100), anti-CD8-Alexa Fluor 700 (clone MEM-31; cat. no.

A7-207-T100; EXBIO Praha, a.s.), anti-TNFα-APC (clone monoclonal

antibody 11; cat.# 562084) and anti-IFNγ-PE (clone B27; cat.#

559327; Becton, Dickinson and Company) antibodies. The stained

cells were pelleted, rinsed with PBS/E and analyzed by flow

cytometry as aforementioned. Reactive cell frequency was calculated

as the difference between the proportion of IFNγ- and/or

TNFα-producing cells in the JBT19 cell-stimulated sample and the

corresponding vehicle-stimulated control from the same sample. In

certain experiments, lymphocytes were pretreated for 30 min with 20

µg/ml anti-MHC-I (clone W6/32; cat. no. 311428; BioLegend, Inc.) or

anti-MHC-II (clone Tü39; cat.# 555556; Becton, Dickinson and

Company) blocking antibodies in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and then stimulated in the presence or

absence of 10 µg/ml antibodies in LM. The flow cytometry was

performed as aforementioned.

Analysis of the cell-mediated

cytotoxic impact on JBT19-GFP cells

JBT19-GFP cells were generated as previously

described (28). The cytotoxic

impact of lymphocytes (enriched or large-scale expanded) on

JBT19-GFP cells treated or not with 200 ng/ml IFNγ for 7 days was

assessed using a previously described protocol with a small

modification (28,35). Briefly, 0.1×106 JBT19-GFP

cells (target) were passaged into a flat-bottom 48-well plate well

and cultured for 1 day. Upon supernatant removal, the wells were

supplemented with 1.0 ×106 lymphocytes (effector) in 1

ml LM with IL-2 (500 IU/ml). After lymphocyte sedimentation for 10

min, the fluorescence of JBT19-GFP cells in the wells was acquired

with a fluorescence microscope and the mean fluorescence intensity

(MFI) at day 0 was calculated using image analysis with ImageJ

1.44p (National Institutes of Health) as previously described

(36). The cells were cocultured

for 3 days and MFIs were determined as on day 0.

Statistical analysis

Values were calculated from the n sample size

using GraphPad Prism 10.2.0 (GraphPad; Dotmatics). Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM of ≥3 independent experimental repeats.

Differences between groups were determined with the indicated

paired or unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test or with one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference, unless

indicated otherwise.

Results

IFNγ abrogates in vitro proliferation

of JBT19 cells, increases their expression levels of CD44, CD47 and

CD95 (FAS) and induces docetaxel resistance

IFNγ is a cytokine produced by activated NK cells

and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (13). These cells are key effector cells

responsible for cancer cell elimination (14,37)

and their presence in tumors is often associated with improved

prognosis of the disease (38,39).

However, once released in the tumor microenvironment, its chronic

impact can also modulate cancer cells. Therefore, the present study

used the recently established UPS sarcoma cell line JBT19 (28) and investigated the long-term

(chronic) impact of this cytokine on the proliferation and

phenotype of JBT19 cells. The rationale for using this cell line

was based on the observation that, although

two-dimensional-cultured JBT19 cells exhibited little-to-no surface

expression levels of MHC-II molecules, as determined by flow

cytometry, supplementation of the culture medium with IFNγ for 3

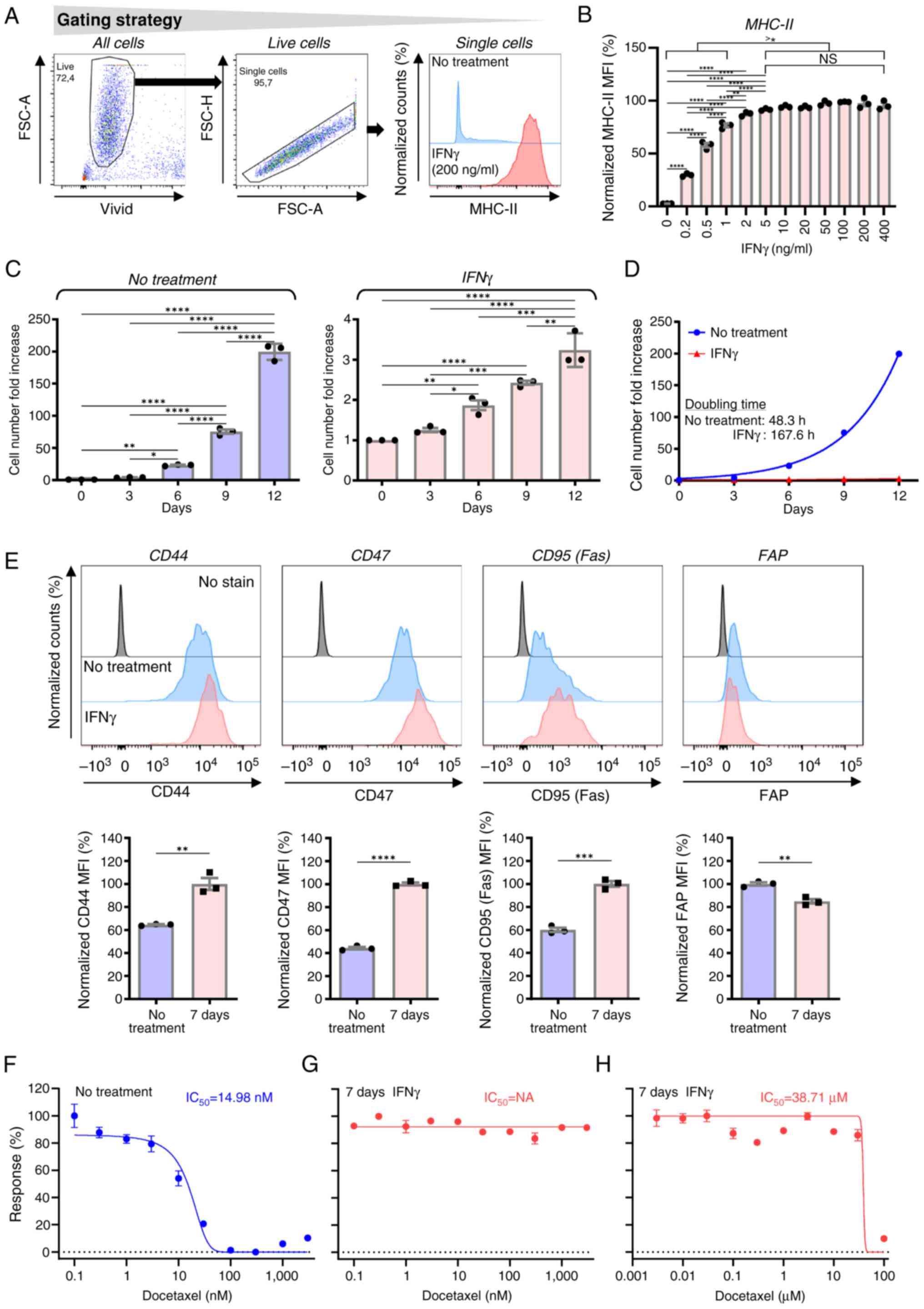

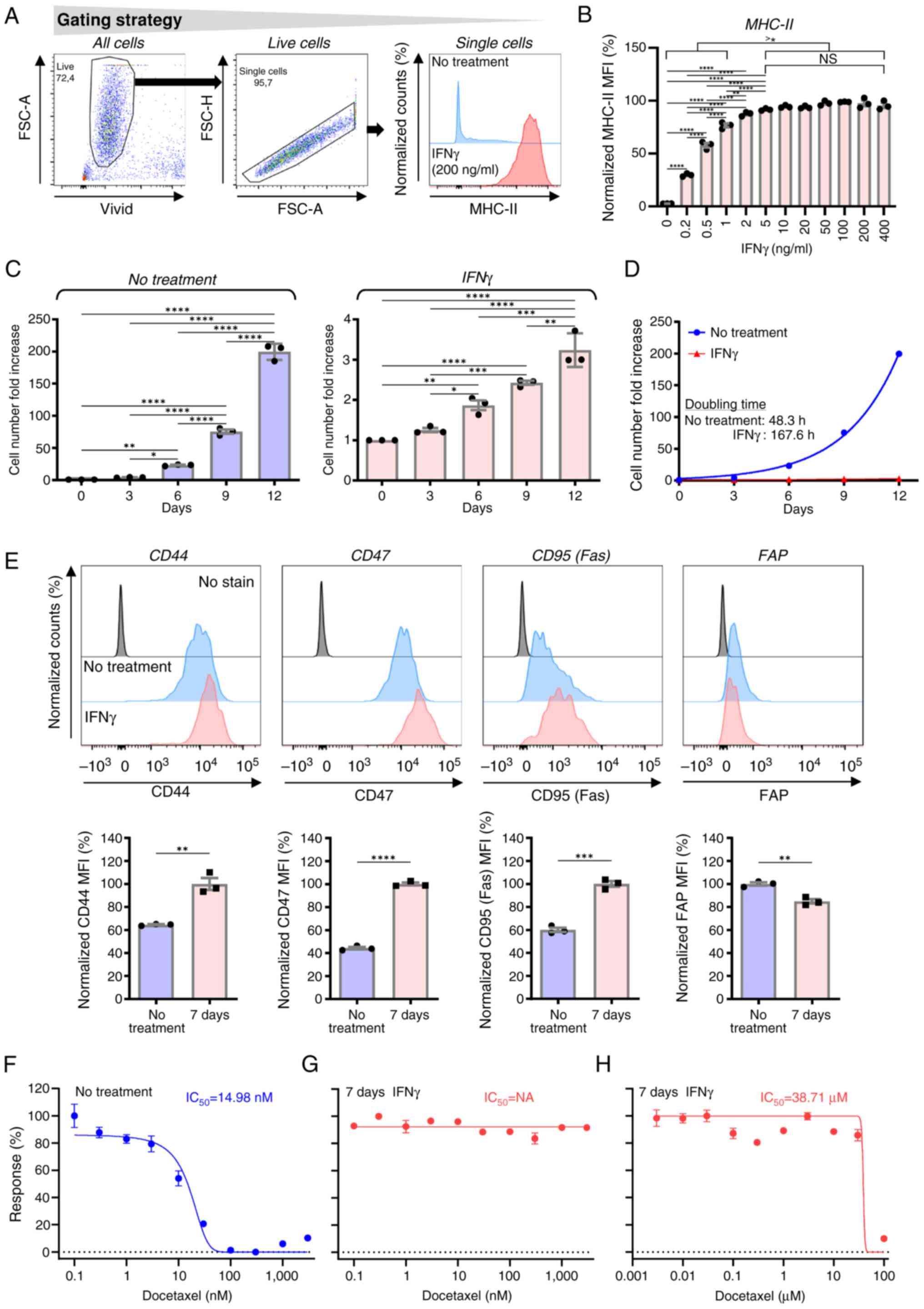

days induced robust surface expression levels of MHC-II (Fig. 1A). This response was concentration

dependent, reaching a plateau at concentrations >5 ng/ml

(Fig. 1B). Furthermore, IFNγ

supplementation reduced the proliferation of JBT19 cells. To

further investigate this effect, JBT19 cells were cultured in the

presence of 200 ng/ml IFNγ for 7 days, ensuring a robust and stable

response within the plateau range and cell proliferation was

subsequently evaluated in the presence or absence of the cytokine.

After the initial delay in the cell proliferation in the first 3

days, presumably due to a transient adverse impact of the passaging

procedure on cell proliferation, IFNγ markedly suppressed the

proliferation of JBT19 cells, increasing their doubling time

>3-fold, from ~2 to >6 days (Fig.

1C and D). This suppression led to a marked decrease in the

proliferation of the cell culture. Whereas the non-treated cell

culture exhibited a 150–200-fold increase in cell numbers in 12

days, cells treated with IFNγ expanded 3-4-fold.

| Figure 1.Impact of IFNγ on the in vitro

proliferation of JBT19 cells and their expression levels of MHC-II,

CD44, CD47 and CD95 (Fas), and their sensitivity to docetaxel. (A)

Gating strategy of flow cytometry data. (B) Extracellular MHC-II

staining of 3-day treated JBT19 cells with the indicated

concentrations of IFNγ. (C) Cell number fold increase in

vehicle-treated JBT19 cells (No treatment, left panel) or 7-day

pre-treated and then cultured with IFNγ (200 ng/ml; IFNγ, right

panel). The evaluated are represented as means ± SEM. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001; n=3 independent

experiments; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). (D)

Calculated proliferation curves and pertinent doubling times from

the data shown in panel C. (E) Extracellular staining of 7-day

vehicle-treated (No treatment) or 7-day IFNγ-treated (IFNγ, 200

ng/ml) JBT19 cells. The cells were stained with specific antibodies

against CD44, CD47, CD95 (Fas) or FAP. In the top panels,

representative histograms are shown and the control (No stain) for

individual fluorochromes refers to staining with vehicle alone. In

the bottom panels, the evaluated data presented as means ± SEM are

shown and statistically significant differences between the groups

are indicated. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. MTT

assay of (F) vehicle-treated JBT19 cells (No treatment), or (G and

H) 7-day IFNγ-treated (IFNγ, 200 ng/ml) JBT19 cells (7 days IFNγ)

exposed to docetaxel at the indicated concentrations for 3 days.

The calculated IC50 from three independent experiments

is shown. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MHC, major

histocompatibility complex; nM, nanomolar; FAP, fibroblast

activation protein. |

Next, the present study investigated how this marked

decrease in JBT19 cell proliferation affected the expression levels

of cell surface markers, which are reported to be possibly

associated with modulated resistance of cancer cells to the immune

system and chemotherapeutics. Among these markers were CD44 (which

is associated with cancer cell stemness), CD47 (a receptor

inhibiting phagocytosis by macrophages and its expression in

multiple cancer types, such as in ovarian and gastric cancer, is

associated with chemoresistance and poor prognosis) (40–42)

and CD95 (Fas; a death receptor inducing apoptosis) (43). As shown in Fig. 1E, 7-day treatment of JBT19 cells

with IFNγ increased the surface expression levels of CD44, CD47 and

CD95 (Fas) in JBT19 cells. By contrast, the surface expression

levels of FAP were reduced. These results demonstrated that IFNγ

suppressed the proliferation of JBT19 cells but induced a phenotype

that could possibly affect JBT19 cell resistance to cytotoxic

chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

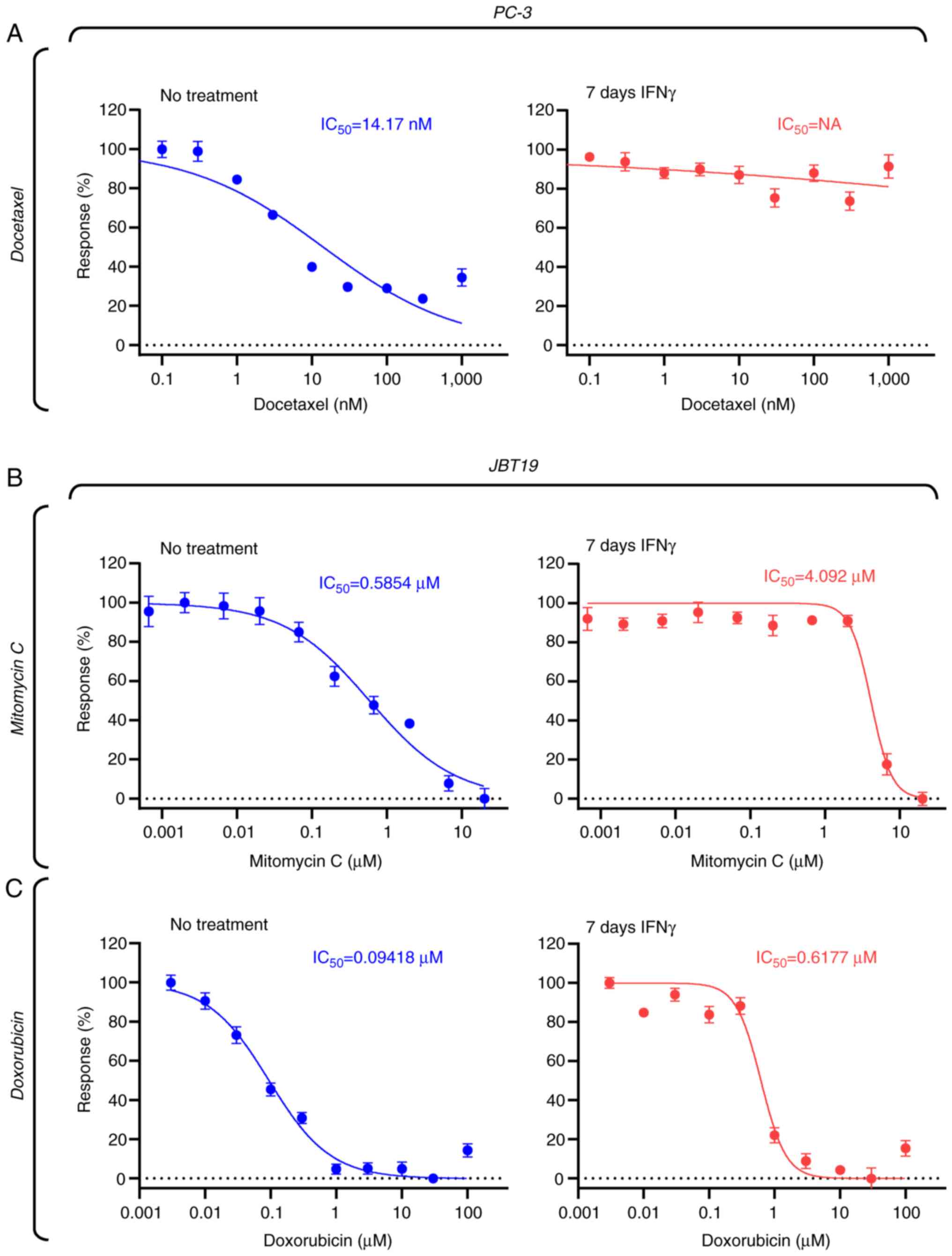

The IFNγ-mediated inhibition of JBT19 cell

proliferation suggested that these cells may develop resistance to

chemotherapeutic agents that primarily target dividing cells

(44). Therefore, the present study

next examined the cytotoxic effects of docetaxel on IFNγ-treated

JBT19 cells. Docetaxel is a commonly used chemotherapy drug

(45) that targets dividing cells

by inhibiting the depolymerization of microtubules, causing mitotic

arrest and subsequent apoptosis (46). JBT19 cells were sensitive to

docetaxel at nanomolar (nM) concentrations (IC50=14.98

nM) as determined by MTT assay (Fig.

1F). However, 7-day treatment of these cells with IFNγ made

these cells highly resistance to docetaxel (Fig. 1G), decreasing their sensitivity by

>2,000-fold (IC50=38.71 µM; Fig. 1H). These results demonstrated that,

albeit IFNγ nearly blocked the proliferation of JBT19 cells, this

was associated with the acquisition of chemoresistance to a widely

used drug such as docetaxel, to which JBT19 cells were otherwise

sensitive at nM concentrations.

IFNγ changes the cell cycle, does not

induce apoptosis and increases STAT1 expression without inducing

the surface expression levels of multidrug resistance protein 1

(MDR-1) or enhancing the expression levels of Bcl-2 in JBT19

cells

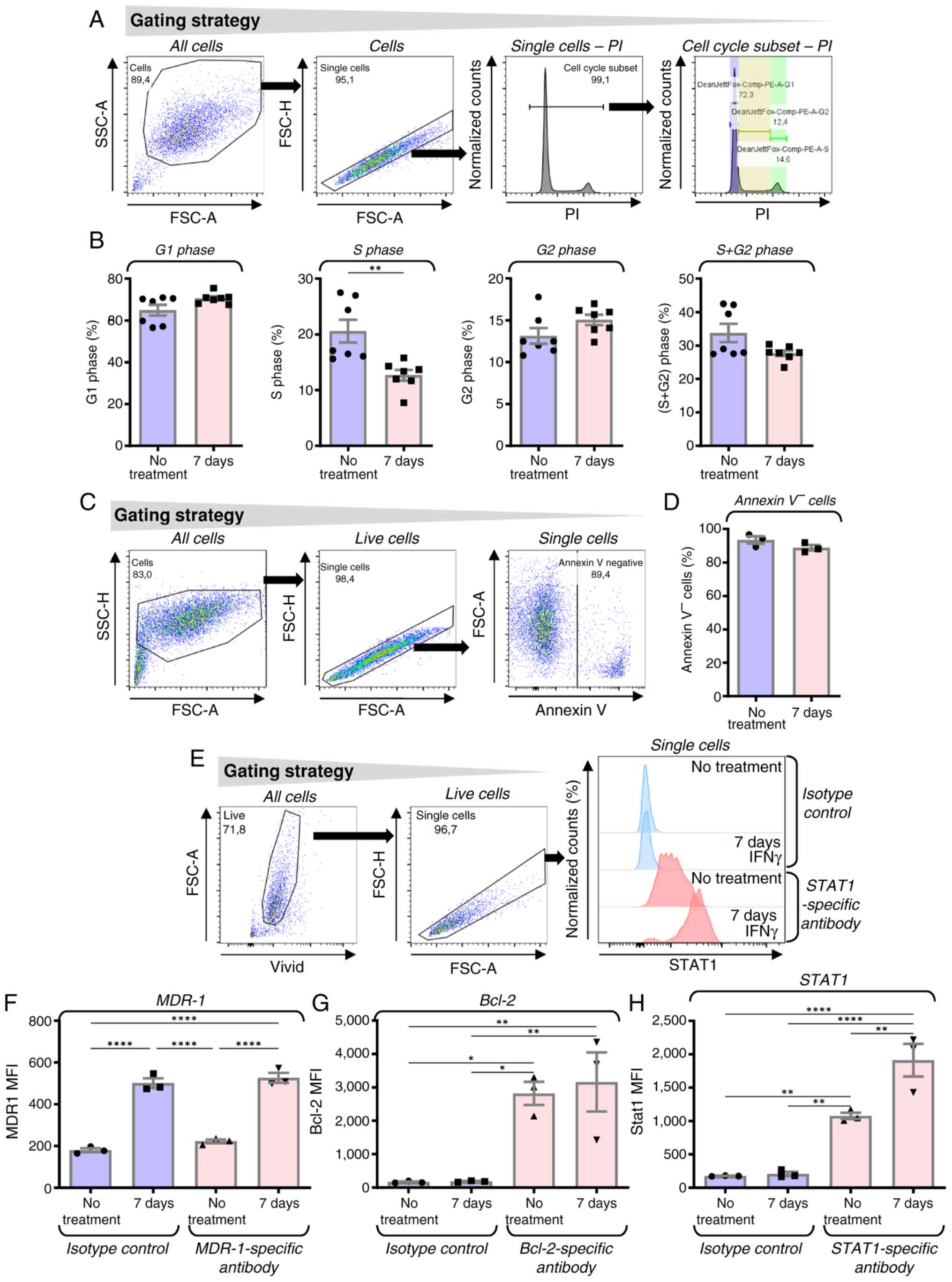

IFNγ treatment is known to impact the cell cycle

(47); therefore, it was next

examined how the 7-day IFNγ treatment affected the cell cycle of

JBT19 cells. The results revealed a trend toward increased

frequencies of cells in G1 and G2 phases and

a decreased frequency in the combined G2 + S population.

Notably, IFNγ treatment induced a significant reduction in the

proportion of cells in S phase (Fig. 2A

and B). This pattern of IFNγ-mediated cell cycle changes was

consistent with observations in other cell types (48,49).

The treatment of JBT19 cells with IFNγ was not associated with

increased apoptosis, expression levels of MDR-1 receptor (50) or modulation of the expression levels

of the antiapoptotic signaling molecule Bcl-2 (51) (Fig.

2C-G). However, sustained exposure to IFNγ for 7 days enhanced

the expression levels of the STAT1 signaling molecule (Fig. 2H), a response previously reported in

multiple cell types (52–55).

IFNγ decreases the expression levels

of Ki-67 and increases the expression levels of PD-L1 and MHC-II in

JBT19 cells

The marked impact of IFNγ on the performance of

JBT19 cells towards chemoresistance was associated with long-term

(7-day) exposure of JBT19 cells to this cytokine. The present study

next evaluated a shorter exposition of JBT19 cells to this cytokine

and investigated a possible reversibility of its effect on their

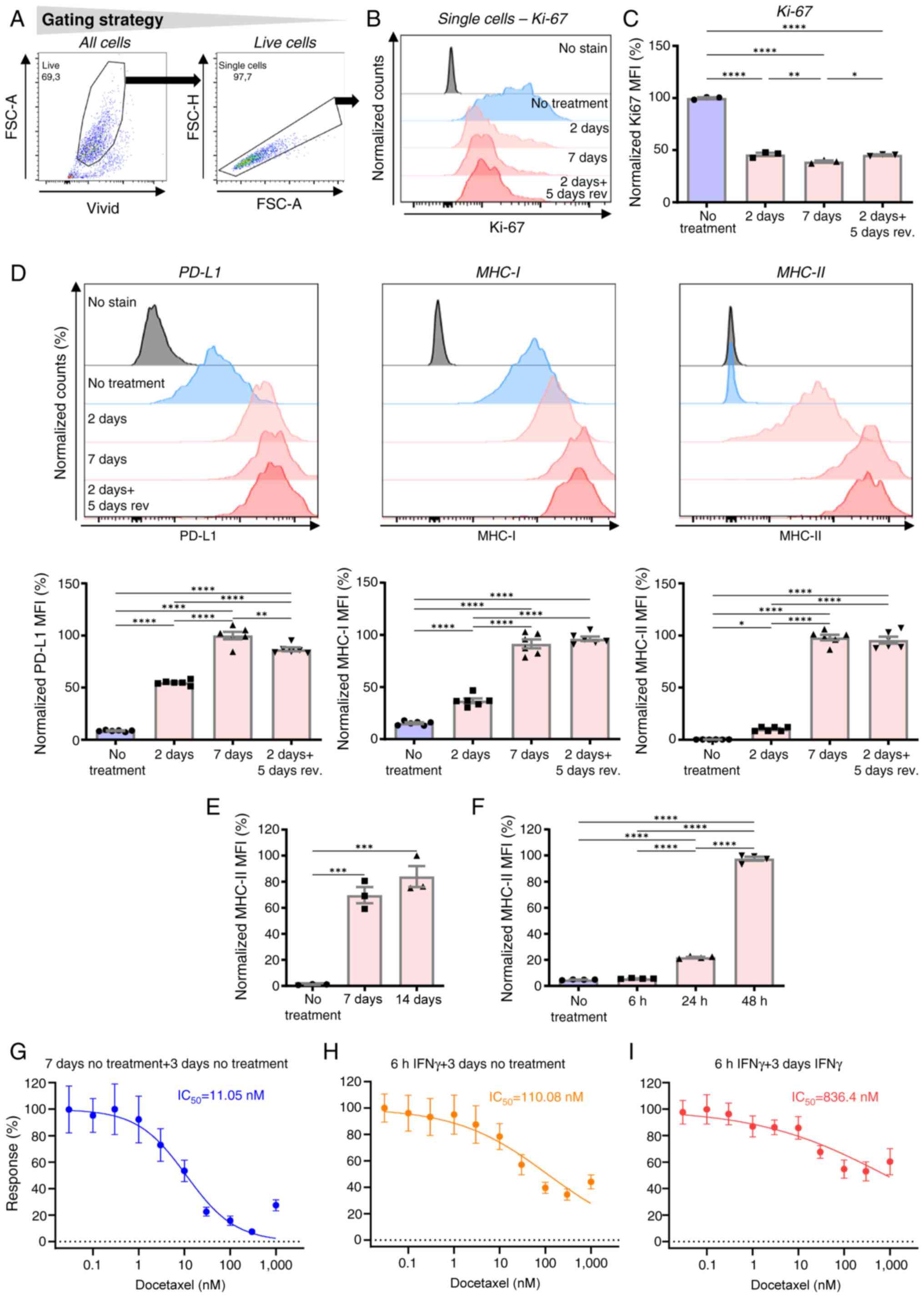

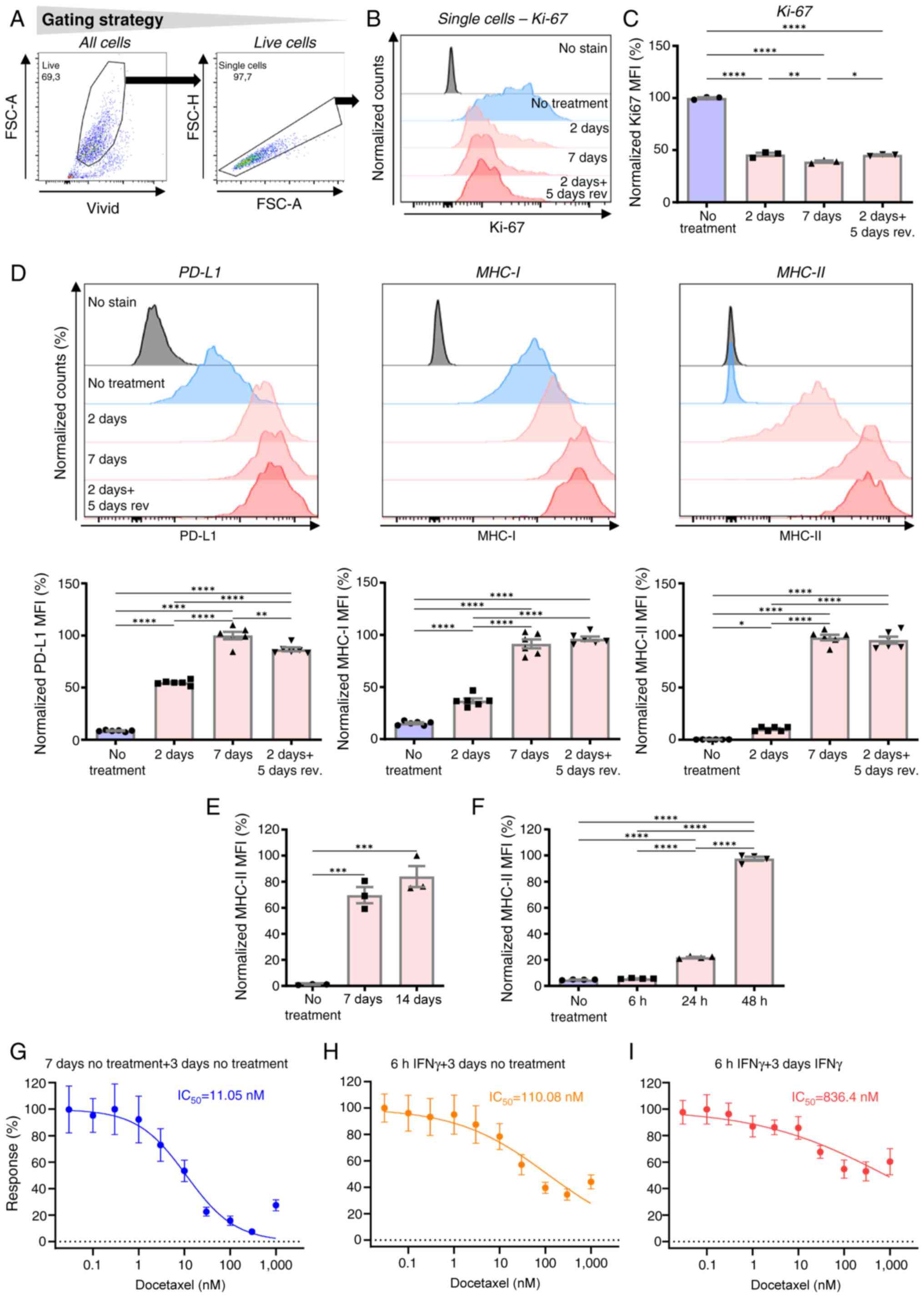

proliferation. To do that, Ki-67 was used as a surrogate marker of

cell proliferation (56). Ki-67

expression was analyzed in JBT19 cells treated with IFNγ (200

ng/ml) for 7 days, 2 days or 2 days followed by its extensive

removal and additional 5-day cell culture. As shown in Fig. 3A-C, 2-day IFNγ treatment decreased

the levels of Ki-67 nearly to the levels observed in 7-day treated

cells. Furthermore, these levels were sustained even after the

following 5 days of cell culture in the absence of IFNγ. These

findings demonstrated that the anti-proliferative impact of IFNγ on

JBT19 cells was induced after a shorter time exposure but was not

reversed even 5 days later.

| Figure 3.In JBT19 cells, IFNγ decreases the

intracellular expression levels of Ki-67, increases the

extracellular expression levels of PD-L1 and MHC-I and enhances the

expression levels of MHC-II. (A) Gating strategy of flow cytometry

data. (B) Intracellular staining with anti-Ki-67-specific antibody

in vehicle-treated (No treatment), 2-day treated (2 d) or 7-day

treated (7 d) JBT19 cells with IFNγ (200 ng/ml). Alternatively, the

cells were treated for 2 days with IFNγ (200 ng/ml) and the

cytokine was then extensively removed, while the cells were

cultured in vehicle alone for additional 5 days (2d + 5d rev). As

control (No stain) for individual fluorochromes, staining with

vehicle alone was used. (C) Evaluation of the MFI staining in panel

B. (D) Histograms of extracellular staining with anti-PD-L1-,

MHC-I- or MHC-II-specific antibodies in samples treated as in panel

B. The control (No stain) for individual fluorochromes was staining

with vehicle alone. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001;

C, n=3 (Ki-67) independent experiments. D, n=6. (E) Extracellular

MHC-II staining of 14-day vehicle-treated (No treatment), 7-day or

14-day IFNγ-treated (IFNγ, 200 ng/ml) JBT19 cells. (F)

Extracellular MHC-II staining of 48-h vehicle-treated or 6-, 24- or

48-h IFNγ-treated (IFNγ, 200 ng/ml) JBT19 cells. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001; E, n=3 independent

experiments. F, n=4 independent experiments. Panels E and F,

one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. MTT assay of (G)

vehicle-treated JBT19 cells or (H and I) JBT19 cells treated for 6

h with IFNγ (200 ng/ml). Next, the treated JBT19 cells were rinsed

and exposed to docetaxel at the indicated concentrations for 3 days

in the (G and H) absence (no treatment + 3 d no treatment, 6 h

IFNγ+3 d no treatment) or (I) presence of IFNγ (200 ng/ml). The

calculated IC50 from n=3 independent experiments is

shown. IFNγ, interferon γ; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; d,

days; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; MHC, major

histocompatibility complex; nM, nanomolar. |

The sustained IFNγ-mediated inhibition of JBT19 cell

proliferation suggested that their phenotype could also be

maintained in the absence of IFNγ. However, since the IFNγ-induced

differences in the surface expression levels of the previously

investigated markers [CD44, CD47, CD95 (Fas) and FAP] were not

extensive, the investigation next focused on other possible markers

whose expression was previously reported to be sensitive to IFNγ

treatment, including PD-L1 (19),

MHC-I (57) and MHC-II (58). The first two markers were cell

surface-expressed in JBT19 cells and the expression levels of

MHC-II were found to be significantly expressed after IFNγ

treatment in the present study. In these experiments, JBT19 cells

were treated with IFNγ as for the Ki-67 analyses and the cell

surface expression levels of PD-L1, MHC-I and MHC-II was

determined. As shown, although JBT19 cells were previously reported

to be PD-L1+ (28), the

increase in PD-L1 expression after treatment with IFNγ was robust

(Fig. 3D). Similar to Ki-67, the

expression levels of PD-L1 was the highest after 7 days of

treatment. However, notable differences were observed compared with

the impact on Ki-67 expression. Specifically, 5 days after 2-day

IFNγ treatment, PD-L1 expression was considerably higher compared

with that in cells treated for 2 days and nearly reached the levels

observed in 7-day-treated cells (Fig.

3D). These results indicated that, after 2-day IFNγ treatment,

the removal of the cytokine did not prevent the cells from further

increasing the expression levels of PD-L1. These findings were also

observed in the expression levels of MHC-I (Fig. 3D). However, the most notable finding

was observed upon the evaluation of the surface expression levels

of MHC-II: JBT19 cells that were negative or weakly positive for

this molecule became positive after 2-day treatment with IFNγ and

the levels were largely enhanced after 7-day treatment with IFNγ

(Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the

expression levels of MHC-II followed the same pattern as PD-L1 and

MHC-I molecules; namely, the levels of MHC-II in cells cultured for

5 days after 2-day IFNγ treatment were markedly higher compared

with the levels in 2-day-treated cells and nearly reached the

levels of 7-day-treated cells. With an extended exposure to

14-day-treatment, the levels of MHC-II did not exhibit any further

notable increase, which indicated that the IFNγ-elicited phenotypic

changes were reaching their plateau within this length of treatment

(Fig. 3E).

Onset of IFNγ-induced phenotypic

remodeling and docetaxel resistance occurs shortly after exposure

to IFNγ

IFNγ induces a signaling pathway that results in

changes in the gene expression pattern within hours after the

stimulation (52,55). Using the expression levels of MHC-II

as a marker of the IFNγ-elicited phenotypic remodeling, it was

identified that MHC-II expression was significantly enhanced after

24-h treatment with IFNγ (Fig. 3F).

However, it was revealed that 6-h treatment with IFNγ enhanced

their resistance to docetaxel by ~10-fold when IFNγ was

subsequently removed during MTT assay (Fig. 3G and H). When IFNγ was present (not

removed) during the subsequent 3-day MTT assay, their resistance to

docetaxel increased ~100-fold (Fig. 3G

and I). These findings indicated that the onset of

JBT19-induced functionality changes (chemoresistance) occurred

within hours after their exposure to IFNγ and continued to be

enhanced with ongoing exposure.

IFNγ-induced phenotypic remodeling and

docetaxel resistance is sustained for extended time but is

reversible

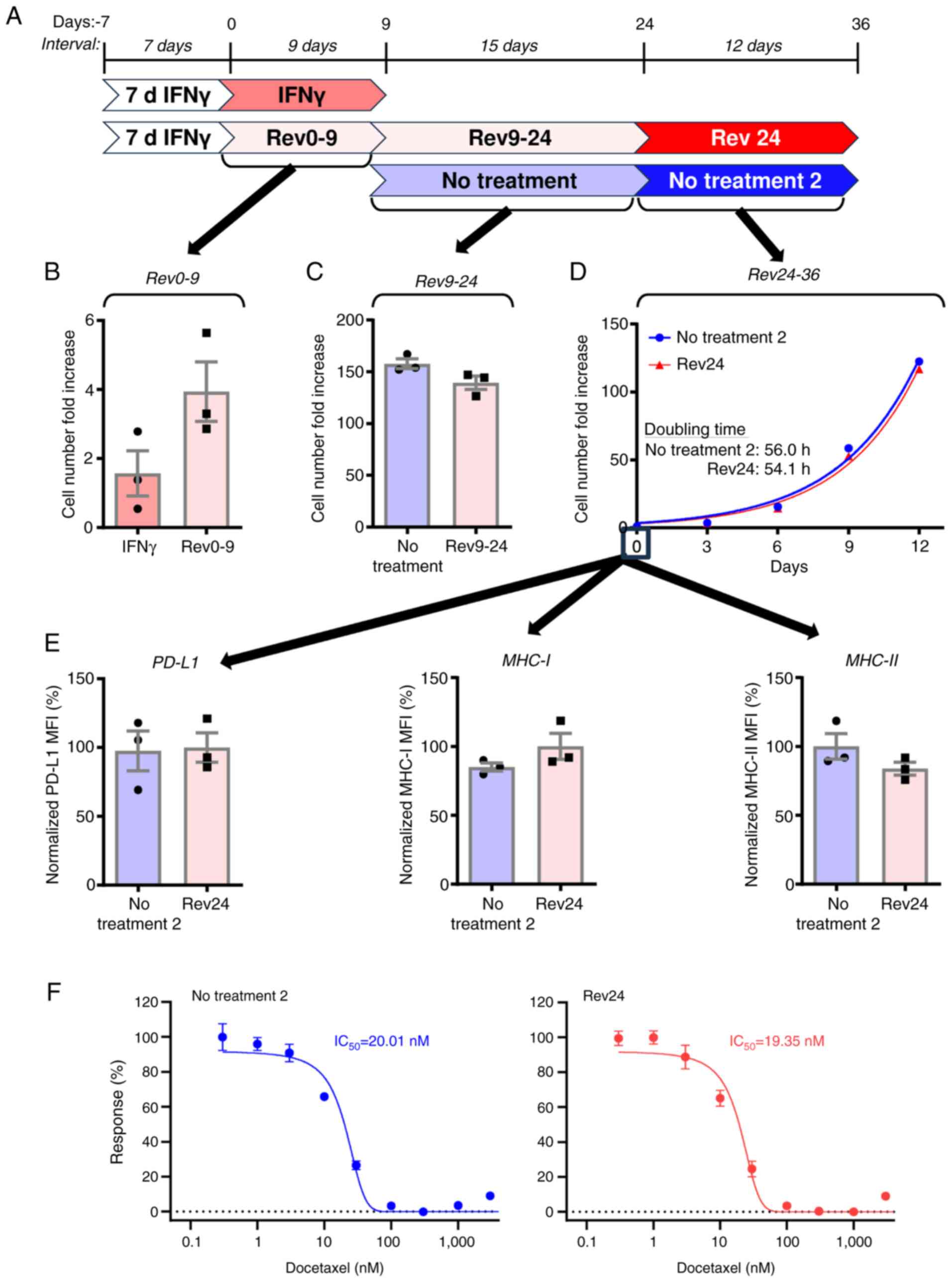

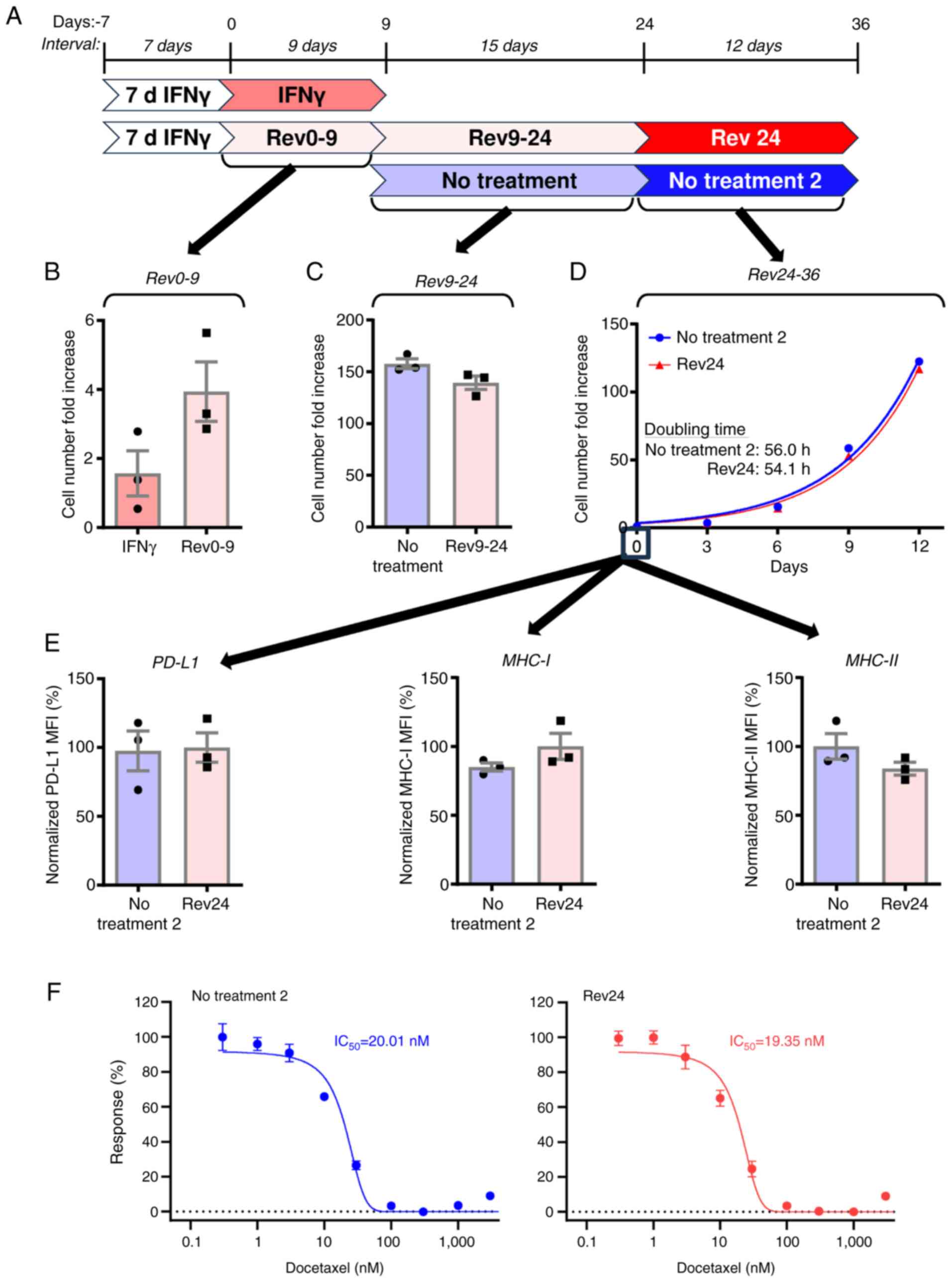

The results in Fig.

3 indicated that the impact of IFNγ on JBT19 cells was

sustained and possibly irreversible, potentially causing permanent

changes in JBT19 cells. To investigate this, 7-day treated JBT19

cells were further cultured in the absence of IFNγ for 9 days

(Fig. 4A, Rev0-9) and their

proliferation rate was compared with that of cells cultured in the

presence of IFNγ (Fig. 4A, IFNγ).

Removal of IFNγ from the cells revealed a tendency to accelerate

cell proliferation (Fig. 4B); the

9-day cell number fold increase accelerated from ~2- to 4-fold

increase. Therefore, 9 days after cytokine removal, the cells were

again passaged and cultured for subsequent 15 days and their

proliferation rate (Fig. 4A,

Rev9-24) was compared with that of IFNγ non-treated JBT19 cells

(Fig. 4A, No treatment). The

proliferation rates of the treated (Rev9-24) and control cells (No

treatment) were comparable (Fig.

4C). To confirm that JBT19 cells regained the same

proliferation rate after 24 days of culture without IFNγ, doubling

times were determined for both treated (Fig. 4, Rev24) and control cells (Fig. 4, No treatment 2). The expansion of

the previously treated JBT19 cells was now similar to that of their

non-treated counterpart and both cell groups demonstrated

comparable doubling times (Fig.

4D). Thus, the impact of IFNγ on cell proliferation was

completely reversed 24 days after IFNγ removal.

| Figure 4.IFNγ-induced phenotypic remodeling

and docetaxel resistance are sustained for an extended time but are

reversible. (A) Schematic representation of the times of the

experiment. (B) JBT19 cells were 7-day treated with IFNγ (200

ng/ml). The cells were then passaged and cultured for 9 days in the

presence (IFNγ; dark pink) or absence (Rev0-9; No treatment, light

pink) of IFNγ (200 ng/ml) and cell number fold increase was

determined. (C) The Rev0-9 sample of JBT19 cells from panel B

(Rev9-24, light pink) or JBT19 cells not treated with IFNγ (No

treatment, light blue) were passaged and cultured in the absence of

IFNγ for 15 days and the cell number fold increase was determined.

(D) Rev9-24 sample of JBT19 cells from C (Rev24, light pink) and

vehicle-treated sample of JBT19 cells from C (No treatment, light

blue) were passaged and cultured for 12 days. Next, the cell number

fold increase was determined at the indicated days and

proliferation curves and pertinent doubling times were calculated.

(E) Evaluation of the mean fluorescence intensities of

extracellular staining with anti-PD-L1-, MHC-I- or MHC-II-specific

antibodies in the Rev24 sample of JBT19 cells at day 0 from panel D

(Rev24, light pink) and vehicle-treated sample of JBT19 cells at

day 0 (No treatment 2, light blue). (F) Results of MTT assay of No

treatment 2 (blue) and Rev24 (red) samples at day 0 from panel D.

Cells were exposed to docetaxel at the indicated concentrations for

3 days. The calculated IC50 are shown (n=3 independent

experiments). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units);

IFNγ, interferon γ; nM, nanomolar; PD-L1, programmed cell

death-ligand 1; MHC, major histocompatibility complex. |

Next, the present study investigated cell

proliferation recovery also translated into the reversion of the

cell surface markers PD-L1, MHC-I and MHC-II. As shown, the

expression levels of PD-L1, MHC-I and MHC-II returned to the levels

of the IFNγ non-treated cells (Fig.

4E).

To evaluate whether the extended cell

culture-elicited reversion also translated into resensitization of

the cells to docetaxel, the cells were analyzed by MTT assay. The

previously treated JBT19 cells regained the same sensitivity to

docetaxel as their non-treated counterparts (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these results

demonstrated that the changes elicited by IFNγ were sustained but

not permanent because the treated JBT19 cells could regain back the

phenotypic and functional properties of the non-treated cells.

IFNγ-elicited chemoresistance is not

JBT19 cell-restricted and can be mitigated by mitomycin C or

doxorubicin in JBT19 cells

The JBT19 cell line was established from soft tissue

sarcoma (28), which is a tumor of

mesenchymal origin (59). To

determine whether IFNγ induced docetaxel resistance in

epithelial-derived tumors, the prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3

was utilized (29). Similar to

JBT19 cells, 7-day IFNγ treatment induced resistance to docetaxel

in PC-3 cells (Fig. 5A). indicating

that the mechanism observed in JBT19 cells also takes place in cell

lines of distinct histological origin.

Docetaxel is a chemotherapeutic agent that primarily

targets rapidly dividing cells (60,61).

The present study results indicated that IFNγ treatment markedly

reduced the proliferation rate of JBT19 cells, suggesting that this

decrease in proliferation could be the main mechanism underlying

JBT19 cell resistance to docetaxel. To determine whether

chemotherapeutics capable of targeting slowly dividing cells could

overcome IFNγ-induced resistance, mitomycin C (62,63)

and doxorubicin (64) were

evaluated. The results revealed that both agents effectively

targeted JBT19 cells at submicromolar concentrations (Fig. 5B and C) and that these agents were

still effective against IFNγ-treated JBT19 cells, albeit their

effective concentrations increased ~10-fold for mitomycin C and

6-fold for doxorubicin (Fig. 5B and

C). Nevertheless, their performance was markedly improved

compared with that of docetaxel, for which the effective

concentration increased >2,000-fold following IFNγ treatment, as

aforementioned. These results thus suggested that the IFNγ-elicited

decrease in the proliferation of JBT19 cells could be the

underlying mechanisms of the observed docetaxel resistance.

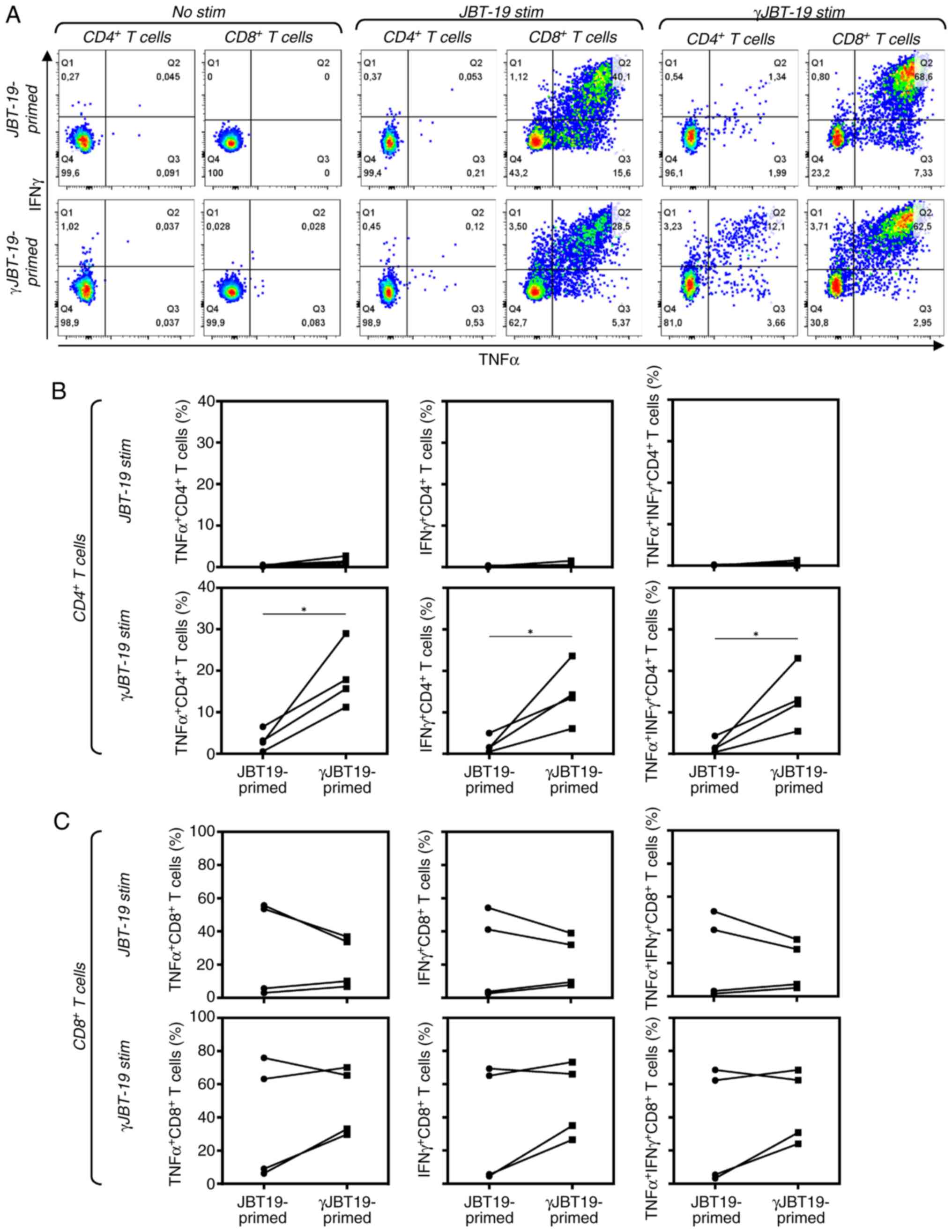

IFNγ treatment of JBT19 cells has no

impact on in vitro antitumor adaptive immune response

The IFNγ-induced chemoresistance of JBT19 cells may

limit the treatment options once similarly behaving cancer cells

are present in tumors of the patients. To investigate whether IFNγ

treatment could also limit the ability of the immune system to

elicit a specific adaptive immune response, JBT19-reactive

lymphocytes were in vitro produced as described previously

(28), using either non-treated

JBT19 cells (JBT19-primed, to produce JBT19-reactive lymphocytes)

or 7-day IFNγ-treated JBT19 cells (γJBT19-primed, to produce

γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes) to stimulate and enrich cell cultures

with reactive lymphocytes. As shown in Fig. S1A and B, the enriched cell cultures

were viable and the majority of cells were T cells exhibiting

tendencies to increased frequencies of CD4+ and

CD8+ populations in the γJBT19-primed cell cultures. The

produced JBT19- or γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes were then stimulated

with either JBT19 or γJBT19 cells and their reactivity was

evaluated through the expression levels of IFNγ and TNFα in the

treated lymphocytes, as determined by intracellular staining and

flow cytometry analyses. As shown in Fig. 6, CD8+ T cells of the

produced JBT19-primed or γJBT19-primed lymphocytes reacted with

both JBT19 or γJBT19 cells (Fig. 6A and

C). Although there were no differences in the reactivity of

CD8+ T cells between JBT19-primed and γJBT19-primed

cultures in high-responder donors, γJBT19-primed lymphocyte

cultures demonstrated enhanced enrichment, with reactive

CD8+ T cells in the low-responder donors, indicating

that IFNγ treatment of JBT19 cells promoted their potential to

increase lymphocyte reactivity and cell culture enrichment with

reactive CD8+ T cells in low-responder donors,

presumably through enhanced cell surface expression levels of MHC-I

(Fig. 6C).

A significant effect of JBT19 cell treatment with

IFNγ was identified for CD4+ T cells. As shown in

Fig. 6, CD4+ T cells

became stimulated only with γJBT19 cells and only significantly in

the γJBT19-primed lymphocytes, while only a negligible stimulation

was observed in JBT19-primed lymphocytes (Fig. 6A and B). These results demonstrated

that IFNγ treatment of JBT19 cells had no negative impact on the

in vitro stimulation of JBT19/γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes

and that the IFNγ-induced de novo expression levels of

MHC-II on the surface of JBT19 cells subsequently enriched the

reactive lymphocytes with γJBT19-reactive CD4+ T cells,

thus providing evidence of the immune functionality of IFNγ-induced

MHC-II on the surface of JBT19 cells.

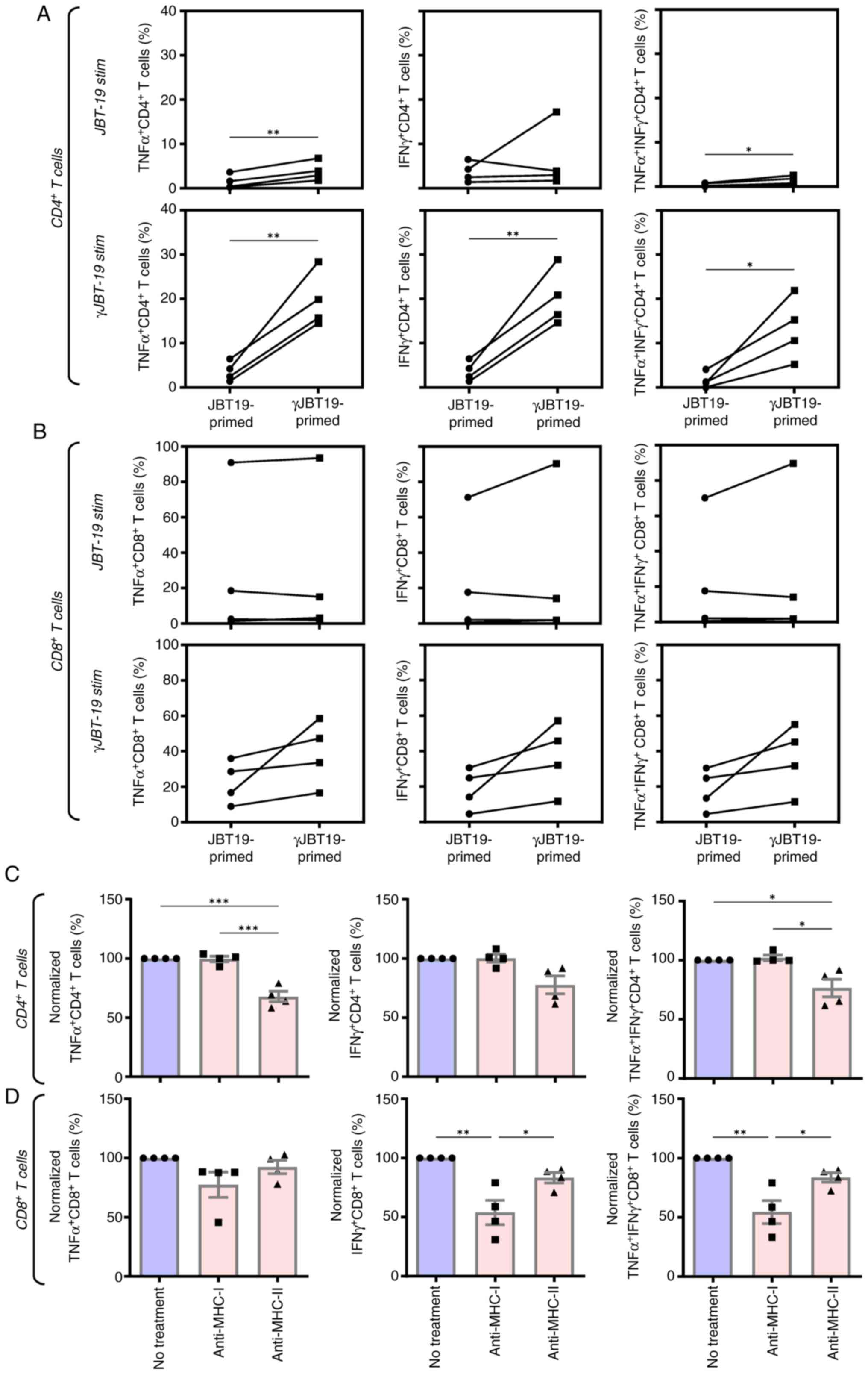

IFNγ treatment of JBT19 cells does not

prevent in vitro amplification of antitumor-elicited adaptive

immune response

Effective antitumor immunity is dependent on its

amplification through a large-scale cell number expansion of

antitumor-reactive lymphocytes. To evaluate whether IFNγ treatment

of JBT19 cells used for stimulation and enrichment with

γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes could limit their later amplification,

the in vitro-enriched γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes were

large-scale expanded using a modified REP previously described for

the expansion of virus antigen-specific lymphocytes (34). Using this protocol, JBT19- or

γJBT19-primed cell cultures could be in vitro expanded with

enriched JBT19/γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes by ~2,000-fold (Fig. S1C). The large-scale expanded cell

cultures were viable and nearly exclusively contained T cells,

including their CD4+ and CD8+ populations

(Fig. S1D and E). Similar to the

enriched cell cultures, the CD8+ T cells of the expanded

cell cultures contained a significant population of JBT19- or

γJBT19-reactive cells (Fig. 7B). In

addition, within the limited number of donors, the expanded cell

cultures enriched through γJBT19 (γJBT19-primed) demonstrated a

notable tendency to enhanced frequencies of the γJBT19-reactive

population compared with the JBT19-primed cell cultures (Fig. 7B). By contrast, the frequencies of

JBT19-reactive CD8+ T cells varied between the donors,

revealing two high responders and two low responders (Fig. 7B). Regardless, the results

demonstrated that IFNγ treatment of JBT19 cells had no detrimental

effects on the ability of cells to induce and amplify a targeted

CD8+ T cell-based immune response against these cells or

their non-treated counterparts.

The reactivity pattern of CD4+ T cells

was similar to the pattern observed with the enriched cell

cultures. CD4+ T cells became stimulated only with

γJBT19 cells and only significantly in the γJBT19-primed and

expanded lymphocytes, while negligible stimulation was observed in

the JBT19-primed and expanded lymphocytes (Fig. 7A). Collectively, these results

indicated that treatment of JBT19 cells with IFNγ did not prevent

adaptive immunity to elicit and amplify a specific CD4+

and CD8+ T cell-based adaptive immune response against

treated JBT19 cells.

Next, the present study investigated whether MHC-T

cell receptor interactions on expanded lymphocytes contributed to

their activation. Using MHC-I and MHC-II blocking antibodies, a

significant reduction was observed in T cell response for TNFα- and

TNFα/IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7C) and for IFNγ- and

TNFα/IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7D). A notable fraction of reactive T

cells remained responsive despite the presence of blocking

antibodies, suggesting either incomplete blockade or the

involvement of bystander stimulation (65).

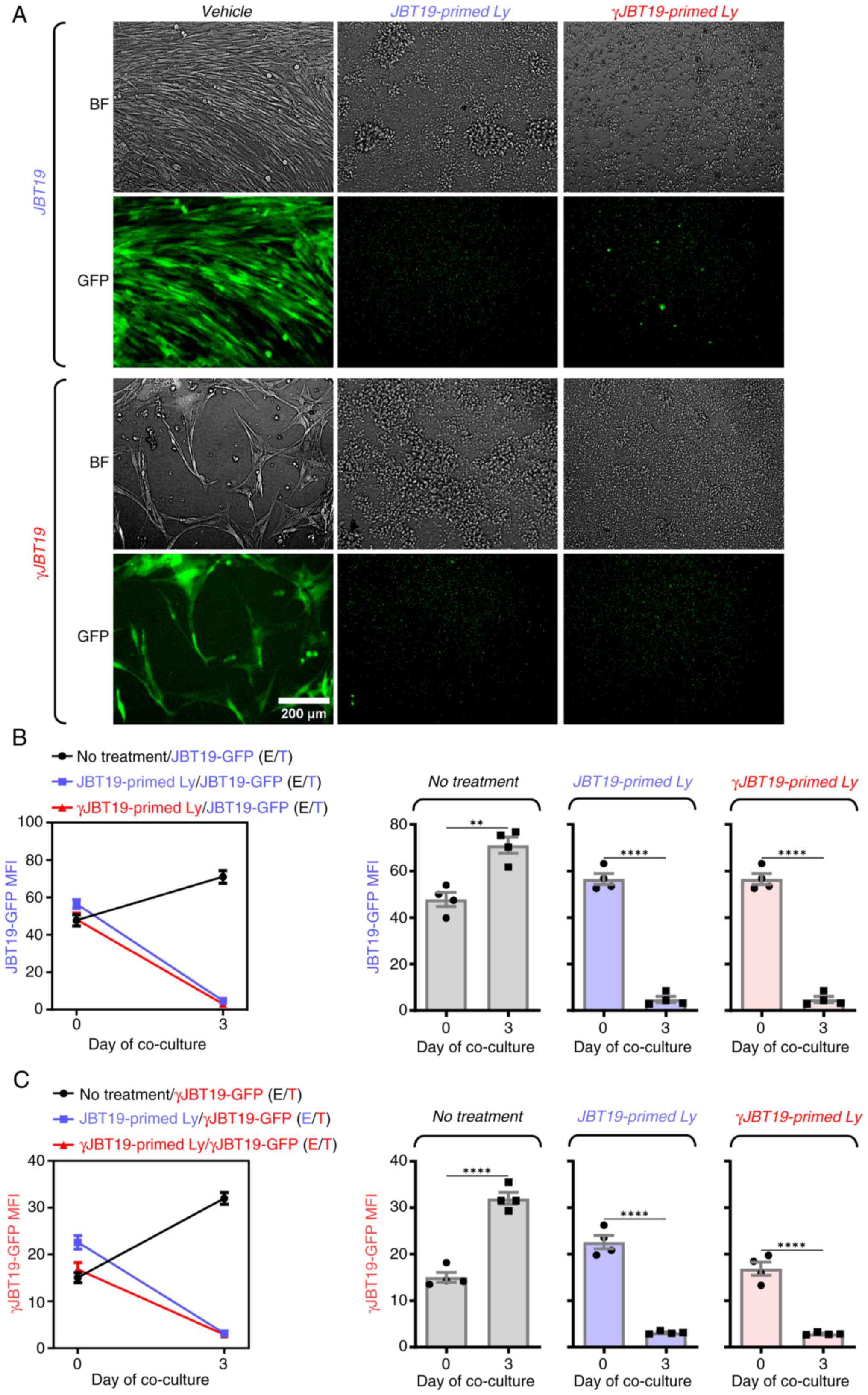

In vitro large-scale expanded

JBT19-reactive lymphocytes are efficient in eliminating

IFNγ-induced docetaxel-resistant JBT19 cells

The finding that IFNγ treatment of JBT19 cells did

not translate into impaired adaptive immune response suggested that

IFNγ-induced chemoresistance could be overcome by targeted adaptive

immunity. To investigate whether this targeted adaptive immunity

could also be effective in eliminating cancer cells, the present

study evaluated whether the JBT19- or γJBT19-primed and large-scale

expanded cell cultures with enriched JBT19/γJBT19-reactive

lymphocytes could eliminate cultured JBT19 or γJBT19 cells. For

this purpose, GFP-expressing JBT19 cells (JBT19-GFP) that the

present study group had previously established were used (28). As shown in Fig. 8, regardless of whether JBT19- or

γJBT19-primed and large-scale expanded cell cultures were used,

both cell culture types were able to efficiently eliminate

IFNγ-treated (γJBT19-GFP) and non-treated (JBT19-GFP) JBT19-GPF

cells. Thus, these results revealed that, although IFNγ treatment

produced docetaxel-resistant JBT19 cells, these docetaxel-resistant

cells were not in vitro resistant to targeted adaptive

immune response.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated a dual impact of IFNγ

on the sensitivity of a UPS cell line, JBT19, to the widely used

chemotherapeutic docetaxel and the ability of this cell line to

in vitro elicit and amplify a targeted immune response.

IFNγ-elicited changes in JBT19 cells were identified to be

sustained but not permanent, since the cells were able to regain

their original phenotype and behavior prior to treatment with IFNγ.

However, reconstitution of this phenotype and behavior took >3

weeks, revealing that IFNγ markedly, yet still reversibly, change

the propensity of cancer cells for extended periods of time and

thus modulate their long-term behavior and resilience towards other

therapeutic interventions.

The tumor microenvironment serves a key role in

determining the behavior of the tumor and its resilience to

elimination by multiple therapeutic approaches, including

immunotherapy and chemotherapy (66,67).

The long-term (chronic) effects of this microenvironment on immune,

stromal and cancer cells can differ notably from short-term (acute)

effects, which may affect mast cell and T cell stimulation as well

as tumor cell metabolism (30,68–73).

Any intervention targeting the tumor microenvironment can alter

tumor behavior. Such changes may either make the tumor more

sensitive to therapy or cause it to develop resistance (74–76).

IFNγ is a cytokine that is a key component of the cell-mediated

response to cancer cells (13,15,77).

The present study confirmed its large production by the in

vitro-produced JBT19-reactive CD8+ T cells once

these cells were exposed to JBT19 cells. Therefore, under immune

attack, cancer cells are likely to be first exposed to this

cytokine before they become eliminated by reactive cytotoxic

lymphocytes. Using the cell line JBT19 as a model, the present

study demonstrated that this exposure could markedly change the

propensity of cancer cells under a presumable immune attack.

IFNγ-exposed JBT19 cells nearly stopped proliferating and started

to express multiple molecules that are associated with worse

disease prognosis, immunoresistance, metastatic behavior, cancer

cell stemness and cancer development [namely, CD44 (78), CD47 (41,79),

PD-L1 (80–82) and CD95 (Fas) (43,83,84)].

However, one of the expressed molecules triggered by IFNγ in JBT19

cells could have an ambiguous functional role towards antitumor

immunity: MHC-II. The expression levels of MHC-II are largely

associated with professional antigen-presenting cells, where it is

responsible for the stimulation of CD4+ T cells.

However, this molecule can also be expressed in other cell types

such as tumor-associated fibroblasts or cancer cells (85). The cancer cell expression levels of

MHC-II in murine tumor models is mostly associated with slower

tumor growth, improved tumor rejection and increased tumor

infiltration with immune cells (86,87).

Furthermore, previous studies reported that MHC-II expression in

tumor cells was associated with improved disease prognosis and

response to immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs) (88–91). However, MHC-II expression in cancer

cells can also drive resistance to immunotherapy (92), which can promote cancer cell

metastasis (93). Using an

IFNγ-JBT19-based study system, the present study findings could

recapitulate and explain several of these contrasting findings

associated with the expression levels of MHC-II in cancer cells.

The expression levels of MHC-II in JBT19 cells were a consequence

of long-term exposure to IFNγ, which also caused a notable decrease

in the speed of proliferation of JBT19 cells. Furthermore, in

vitro-enriched and -expanded JBT19-reactive lymphocytes

produced IFNγ after their stimulation with JBT19 cells. Therefore,

a close-by antitumor activity in vivo upon which cytotoxic

lymphocytes attack cancer cells could be the source of IFNγ, which

may induce MHC-II expression in the not-yet attacked cancer cells.

As such, the expression levels of MHC-II in cancer cells could be

thus viewed as a marker sensing ongoing antitumor immune activity

in the vicinity of cancer cells. There, it could be considered that

the expression levels of MHC-II in cancer cells of tumors could

serve as a surrogate predictive marker for the efficacy of ICIs

(anti-PD-1, anti-PDL-1), as this efficacy is increased in inflamed

tumors (94). Similar conclusions

could be inferred from the expression levels of PD-L1 in

IFNγ-treated JBT19 cells, the expression levels of which are often

enhanced in inflamed tumors, where IFNγ could be present at high

levels in the tumor milieu, regulating, alongside other cytokines

(IL-27, IL-1α) (95), the

expression levels of PD-L1 in cancer cells (96). However, whether other cytokines in

the tumor milieu could promote PD-L1 or MHC-II expression in JBT19

cells, remains to be further investigated in follow-up in

vivo models using JBT19 cells and pertinent therapeutic

interventions in the future.

Antitumor immune activity is key to tumor

elimination. This activity is boosted or elicited by immunotherapy.

As immunotherapy has become the first-line treatment in numerous

oncological diagnoses, such as advanced non-small cell lung and

advanced head and neck cancer or metastatic melanoma (3–6),

antitumor immunity serves a key role in therapy-naïve tumors and

changes their behavior, which can cause cancer cell immune evasion

and resistance to immunotherapy (92,97,98).

Although the present study indicated that IFNγ-treated JBT19 cells

were in vitro efficiently eliminated by JBT19- or

γJBT19-reactive lymphocytes, this scenario may not hold in

vivo, where not all cancer cells often become readily and

entirely eliminated (99). These

cells may migrate to distant locations away from the tumor and

exhibit their IFNγ-induced characteristics. One possible

interaction could involve novel expression levels of MHC-II, which

in turn may lead to the activation of regulatory CD4+ T

cells in lymph nodes (93). The

present study demonstrated that γJBT19 cells in vitro

induced the enrichment and expansion of γJBT19-reactive

CD4+ T cells, the reactivity of which was presumably

dependent on the expression and functionality of MHC-II, since no

enrichment or expansion of γJBT19-reactive CD4+ T cells

was observed in IFNγ non-treated JBT19 cells. However, whether

these γJBT19-reactive CD4+ T cells hold or could later

acquire (92) a regulatory

potential remains to be further elucidated. Nevertheless, the

IFNγ-induced reversible but sustained reprogramming of cancer cells

not only indicates the cancer cell plasticity that can be

responsible for the disease resistance to immunotherapy and

possible promotion of metastatic behavior (100–102), but may also have notable

implications for other therapeutic modalities, including cytotoxic

chemotherapy.

The robustness of the novel IFNγ-JBT19-based system

helped demonstrate the marked impact of IFNγ on the proliferation

of JBT19 cells and their expansion in cell culture. IFNγ treatment

not only nearly stopped the expansion of JBT19 cells in the cell

culture, but also made them resistant to the chemotherapeutic agent

docetaxel, which is one of the widely used anticancer drugs

(45). Immunotherapy that elicits

or promotes an immune attack on tumors may indicate a therapeutic

impact leading to the elimination of cancer cells; by contrast, it

can also produce cancer cell immunoresistance. Therefore, although

IFNγ is often considered a marker of effective immunotherapy,

promoting both immune and cancer cells by increasing antigen

presentation and recruiting more cancer cell-targeting immune cells

to tumors, it can also exhibit the opposite role in the responses

of patients to immunotherapy by contributing to the development of

mechanisms associated with the acquisition of resistance to

immunotherapy, including resistance to ICIs (72,103).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is, however, the

first to demonstrate that IFNγ can elicit resistance beyond

immunotherapy, impacting chemotherapy.

The present study indicated that chronic exposure of

JBT19 cells to IFNγ significantly slowed down their proliferation.

This suggested that the cell line could become resistant to

chemotherapeutics effective against dividing cells such as

docetaxel (46). The choice to

study docetaxel confirmed this expectation, as an increased

resistance to the drug was observed. However, the extent of this

acquired resistance was unexpected; a cell line that was initially

sensitive to nM concentrations of the drug became nearly resistant

to this drug after prolonged exposure to IFNγ. A similar

observation was made in PC-3 cells, suggesting that this mechanism

of resistance is not limited to sarcomas but may also be relevant

in carcinoma cell lines (59). This

finding contrasted with previous research, which demonstrated that

IFNγ sensitized cancer cells to chemotherapy in a model of

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (104). However, this sensitization was

based on 40-fold lower concentrations of IFNγ, 5 ng/ml vs. 200

ng/ml in the present study and only 2-day treatment vs. 7-day

treatment. Furthermore, the cytotoxic effect was investigated in a

combination with recombinant human TNF-related apoptosis inducing

ligand (TRAIL), a molecule that serves a key role in the ability of

the immune system to selectively induce apoptosis (programmed cell

death) in cancer cells (105).

TRAIL receptor expression or functionality is enhanced by IFNγ,

which associates this modulation to both chemoresistance and

immunoresistance (106,107). Therefore, the conditions of the

present study were more robust concerning the IFNγ concentration

and exposure time, absence of the contributing TRAIL ligand/TRAIL

receptor-mediated cytotoxicity and presumably were more closely

mimicking in vivo conditions under which local

concentrations of IFNγ at sites of an ongoing and concentrated

attack on cancer cells by cytotoxic lymphocytes could be increasing

and the exposure time could be chronic.

Analysis of chemotherapeutics that target

non-dividing or slowly dividing cells via multiple mechanisms, such

as mitomycin C (108,109) and doxorubicin (110,111), further supports the notion that

downregulation of cell proliferation could be a key mechanism

underlying IFNγ-induced resistance. One potential driver of this

mechanism is the observed upregulation of STAT1 in IFNγ-treated

JBT19 cells. Upregulation of STAT1 has been associated not only

with chemoresistance, including resistance to docetaxel (112,113), but also to mechanisms that can be

mitigated by targeting the STAT signaling pathway (114,115). The detailed mechanism that

underpins this drug resistance acquisition warrants further

investigation, as well as its existence in other cell lines, its

performance in 3D-culture/co-culture models or in vivo

animal models and its potential interaction with other

chemotherapeutics, particularly those whose cytotoxic impact is not

as much cell proliferation-dependent, such as alkylating drugs,

proteasome inhibitors and autophagy inhibitors (116,117). Conducting these validation studies

will be key to determine the extent to which immune mechanisms

drive drug resistance. Regardless of the scope of this mechanism

that needs to be addressed in follow-up studies, the use of JBT19

cells in the present study enabled to describe a novel IFNγ-driven

mechanism that provides evidence of the interplay between

immunotherapy and cancer cell chemoresistance.

This novel mechanism could have notable

implications for immunotherapy and other treatment options

(targeted therapy) where IFNγ signatures can serve a notable role

(118). IFNγ signatures are

frequently associated with improved responses to immunotherapy

(20,21,72,119).

However, these responses are often insufficient to fully prevent

disease progression. After immunotherapy failure, chemotherapy

commonly remains a standard treatment option (120,121). In certain cases, the chemotherapy

outcome is greater than expected in the absence of prior

immunotherapy (22,23). In certain instances, chemotherapy

efficacy is not improved (122).

However, there are also studies indicating that chemotherapy can be

less effective following failed immunotherapy compared with

treatment-naïve conditions (24,25).

The present study revealed a novel mechanism that

may underline the immunotherapy-induced acquisition of transient

chemotherapy resistance, which could be associated with enhanced

IFNγ signatures often associated with immunotherapy (20,21,72,119).

The present study demonstrated that this IFNγ-mediated resistance

differentially impacted chemotherapeutic agents, rendering cancer

cells either completely resistant to certain drugs (such as

docetaxel) or partially resistant to others (such as mitomycin C

and doxorubicin). From a clinical perspective, these findings

suggested that therapeutic decision-making after immunotherapy

failure should account for this mechanism when selecting subsequent

chemotherapeutic regimens. Furthermore, similar considerations

should be applied during the design of next-generation

therapeutics, such as antibody-drug conjugates or nanoparticle-drug

conjugates, particularly when choosing the chemotherapeutic

payloads to maximize efficacy (123).

The present study reported a robust system based on

a novel UPS cell line, JBT19, through which a dual identity of IFNγ

towards chemoresistance and immunostimulation was demonstrated

in vitro. This dual identity materialized through sustained

but reversible phenotypical and functional changes in IFNγ-impacted

JBT19 cells, and produced chemoresistance on one side, and enhanced

immunostimulatory potential on the other. Although this dual

identity could be cell line- and condition-specific, its engagement

under specific disease conditions and therapy could markedly affect

the outcome of therapy. Therefore, these findings could have

potentially notable implications for combined therapies, namely for

the combinations of immunotherapy and chemotherapy in the

future.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the

present study revealed for the first time the ‘dual role’ in

chronic IFNγ exposure, leading to both chemoresistance and

immunosensitivity. This may have key implications for the interplay

between the effectiveness of cytotoxic chemotherapy and

immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Czech

Republic (grant no. NU23-08-00071).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PT and DSt performed cell culture, viability and

flow cytometry analyses. DSt performed cytotoxic analyses. PT and

DSm conceived and designed the present study. DSm supervised the

present study. DSt contributed to the present study design. DSm

wrote the manuscript. PT and DSt wrote the manuscript and confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the

ethics standards of the institutional, national research committee

(Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Motol in Prague;

approval no. EK-602.4/22; Prague, Czech Republic). All experiments

were performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki

and its later amendments or comparable ethics standards. All

volunteers included in the present study signed an informed consent

form for the use of their blood-derived products in future

research.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sun H, Liu J, Hu F, Xu M, Leng A, Jiang F

and Chen K: Current research and management of undifferentiated

pleomorphic sarcoma/myofibrosarcoma. Front Genet. 14:11094912023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wu JT, Nowak E, Imamura J, Leng J, Shepard

D, Campbell SR, Scott J, Nystrom L, Mesko N, Schwartz GK and Burke

ZDC: Immunotherapy in the treatment of undifferentiated pleomorphic

sarcoma and myxofibrosarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 26:891–909.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang J and Wu L: First-line immunotherapy

for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Current progress and

future prospects. Cancer Biol Med. 21:117–124. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Reardon S: First cell therapy for solid

tumours heads to the clinic: What it means for cancer treatment.

Nature. Mar 11–2024.doi: 10.1038/d41586-024-00673-w (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

5

|

Huang Y, Zhou H, Zhao G, Wang M, Luo J and

Liu J: Immune checkpoint inhibitors serve as the First-line

treatment for advanced head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope.

134:749–761. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lamba N, Ott PA and Iorgulescu JB: Use of

First-line immune checkpoint inhibitors and association with

overall survival among patients with metastatic melanoma in the

Anti-PD-1 Era. JAMA Netw Open. 5:e22254592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yau T, Galle PR, Decaens T, Sangro B, Qin

S, da Fonseca LG, Karachiwala H, Blanc JF, Park JW, Gane E, et al:

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus lenvatinib or sorafenib as

first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

(CheckMate 9DW): An Open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet.

405:1851–1864. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Diker O and Olgun P: Salvage chemotherapy

in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer after prior

immunotherapy: Aa retrospective, real-life experience study.

Anticancer Drugs. 33:752–757. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Assi HI, Zerdan MB, Hodroj M, Khoury M,

Naji NS, Amhaz G, Zeidane RA and El Karak F: Value of chemotherapy

post immunotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Oncotarget. 14:517–525. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sordo-Bahamonde C, Lorenzo-Herrero S,

Gonzalez-Rodriguez AP, Martínez-Pérez A, Rodrigo JP, García-Pedrero

JM and Gonzalez S: Chemo-immunotherapy: A new trend in cancer

treatment. Cancers (Basel). 15:29122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang Z, Liu X, Chen D and Yu J:

Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: The dawn of cancer

treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:2582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ni L and Lu J: Interferon gamma in cancer

immunotherapy. Cancer Med. 7:4509–4516. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Castro F, Cardoso AP, Goncalves RM, Serre

K and Oliveira MJ: Interferon-gamma at the crossroads of tumor

immune surveillance or evasion. Front Immunol. 9:8472018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Martinez-Lostao L, Anel A and Pardo J: How

do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clin Cancer Res.

21:5047–5056. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bhat P, Leggatt G, Waterhouse N and Frazer

IH: Interferon-γ derived from cytotoxic lymphocytes directly

enhances their motility and cytotoxicity. Cell Death Dis.

8:e28362017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mazet JM, Mahale JN, Tong O, Watson RA,

Lechuga-Vieco AV, Pirgova G, Lau VWC, Attar M, Koneva LA, Sansom

SN, et al: IFNgamma signaling in cytotoxic T cells restricts

anti-tumor responses by inhibiting the maintenance and diversity of

intra-tumoral stem-like T cells. Nat Commun. 14:3212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jorgovanovic D, Song M, Wang L and Zhang

Y: Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: A review.

Biomark Res. 8:492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jing ZL, Liu GL, Zhou N, Xu DY, Feng N,

Lei Y, Ma LL, Tang MS, Tong GH, Tang N and Deng YJ: Interferon-γ in

the tumor microenvironment promotes the expression of B7H4 in

colorectal cancer cells, thereby inhibiting cytotoxic T cells. Sci

Rep. 14:60532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Abiko K, Matsumura N, Hamanishi J,

Horikawa N, Murakami R, Yamaguchi K, Yoshioka Y, Baba T, Konishi I

and Mandai M: IFN-γ from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and

promotes progression of ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 112:1501–1509.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wong CW, Huang YY and Hurlstone A: The

role of IFN-γ-signalling in response to immune checkpoint blockade

therapy. Essays Biochem. 67:991–1002. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Reijers ILM, Rao D, Versluis JM, Menzies

AM, Dimitriadis P, Wouters MW, Spillane AJ, Klop WMC, Broeks A,

Bosch LJW, et al: IFN-γ signature enables selection of neoadjuvant

treatment in patients with stage III melanoma. J Exp Med.

220:e202219522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Casadei B, Argnani L, Morigi A, Lolli G,

Broccoli A, Pellegrini C, Nanni L, Stefoni V, Coppola PE, Carella

M, et al: Effectiveness of chemotherapy after anti-PD-1 blockade

failure for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Med.

9:7830–7836. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Saleh K, Daste A, Martin N, Pons-Tostivint

E, Auperin A, Herrera-Gomez RG, Baste-Rotllan N, Bidault F, Guigay

J, Le Tourneau C, et al: Response to salvage chemotherapy after

progression on immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with

recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and

neck. Eur J Cancer. 121:123–129. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Goldinger SM, Buder-Bakhaya K, Lo SN,

Forschner A, McKean M, Zimmer L, Khoo C, Dummer R, Eroglu Z,

Buchbinder EI, et al: Chemotherapy after immune checkpoint

inhibitor failure in metastatic melanoma: A retrospective

multicentre analysis. Eur J Cancer. 162:22–33. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Black M, Barsoum IB, Truesdell P,

Cotechini T, Macdonald-Goodfellow SK, Petroff M, Siemens DR, Koti

M, Craig AW and Graham CH: Activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune

checkpoint confers tumor cell chemoresistance associated with

increased metastasis. Oncotarget. 7:10557–10567. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lazcano R, Barreto CM, Salazar R, Carapeto

F, Traweek RS, Leung CH, Gite S, Mehta J, Ingram DR, Wani KM, et

al: The immune landscape of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Front Oncol. 12:10084842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wei X, Ruan H, Zhang Y, Qin T, Zhang Y,

Qin Y and Li W: Pan-cancer analysis of IFN-gamma with possible

immunotherapeutic significance: A verification of single-cell

sequencing and bulk omics research. Front Immunol. 14:12021502023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Taborska P, Lukac P, Stakheev D,

Rajsiglova L, Kalkusova K, Strnadova K, Lacina L, Dvorankova B,

Novotny J, Kolar M, et al: Novel PD-L1- and collagen-expressing

patient-derived cell line of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma

(JBT19) as a model for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Rep. 13:190792023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kaighn ME, Narayan KS, Ohnuki Y, Lechner

JF and Jones LW: Establishment and characterization of a human

prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3). Invest Urol. 17:16–23.

1979.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Taborska P, Stakheev D, Svobodova H,

Strizova Z, Bartunkova J and Smrz D: Acute conditioning of

Antigen-expanded CD8+ T cells via the GSK3β-mTORC axis

differentially dictates their immediate and distal responses after

antigen rechallenge. Cancers (Basel). 12:37662020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Smrž D, Kim MS, Zhang S, Mock BA, Smrzová

S, DuBois W, Simakova O, Maric I, Wilson TM, Metcalfe DD and

Gilfillan AM: mTORC1 and mTORC2 differentially regulate homeostasis

of neoplastic and non-neoplastic human mast cells. Blood.

118:6803–6813. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Smrž D, Dráberová L and Dráber P:

Non-apoptotic phosphatidylserine externalization induced by

engagement of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. J

Biol Chem. 282:10487–10497. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Taborska P, Bartunkova J and Smrz D:

Simultaneous in vitro generation of human CD34+-derived dendritic

cells and mast cells from non-mobilized peripheral blood

mononuclear cells. J Immunol Methods. 458:63–73. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Taborska P, Lastovicka J, Stakheev D,

Strizova Z, Bartunkova J and Smrz D: SARS-CoV-2 spike

glycoprotein-reactive T cells can be readily expanded from COVID-19

vaccinated donors. Immun Inflamm Dis. 9:1452–1467. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Stakheev D, Taborska P, Kalkusova K,

Bartunkova J and Smrz D: LL-37 as a powerful molecular tool for

boosting the performance of ex vivo-Produced human dendritic cells

for cancer immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics. 14:27472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Stakheev D, Taborska P, Strizova Z,

Podrazil M, Bartunkova J and Smrz D: The WNT/β-catenin signaling

inhibitor XAV939 enhances the elimination of LNCaP and PC-3

prostate cancer cells by prostate cancer patient lymphocytes in

vitro. Sci Rep. 9:47612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Molgora M, Cortez VS and Colonna M:

Killing the invaders: NK cell impact in tumors and Anti-tumor

therapy. Cancers (Basel). 13:5952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang S, Liu W, Hu B, Wang P, Lv X, Chen S

and Shao Z: Prognostic significance of Tumor-infiltrating natural

killer cells in solid tumors: A systematic review and

Meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 11:12422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sun YP, Ke YL and Li X: Prognostic value

of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T cells in patients with breast cancer:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Lett. 25:392023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yaghobi Z, Movassaghpour A, Talebi M,

Abdoli Shadbad M, Hajiasgharzadeh K, Pourvahdani S and Baradaran B:

The role of CD44 in cancer chemoresistance: A concise review. Eur J

Pharmacol. 903:1741472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang H, Tan M, Zhang S, Li X, Gao J, Zhang

D, Hao Y, Gao S, Liu J and Lin B: Expression and significance of

CD44, CD47 and c-met in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int J Mol

Sci. 16:3391–3404. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yoshida K, Tsujimoto H, Matsumura K,

Kinoshita M, Takahata R, Matsumoto Y, Hiraki S, Ono S, Seki S,

Yamamoto J and Hase K: CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and a

therapeutic target in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 4:1322–1333.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Peter ME, Hadji A, Murmann AE, Brockway S,

Putzbach W, Pattanayak A and Ceppi P: The role of CD95 and CD95

ligand in cancer. Cell Death Differ. 22:549–559. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tilsed CM, Fisher SA, Nowak AK, Lake RA

and Lesterhuis WJ: Cancer chemotherapy: Insights into cellular and

tumor microenvironmental mechanisms of action. Front Oncol.

12:9603172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Montero A, Fossella F, Hortobagyi G and

Valero V: Docetaxel for treatment of solid tumours: A systematic

review of clinical data. Lancet Oncol. 6:229–239. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Imran M, Saleem S, Chaudhuri A, Ali J and

Baboota S: Docetaxel: An update on its molecular mechanisms,

therapeutic trajectory and nanotechnology in the treatment of

breast, lung and prostate cancer. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol.

602020.

|

|

47

|

Sangfelt O, Erickson S and Grander D:

Mechanisms of interferon-induced cell cycle arrest. Front Biosci.

5:D479–D487. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kulkarni A, Scully TJ and O'Donnell LA:

The antiviral cytokine interferon-gamma restricts neural

stem/progenitor cell proliferation through activation of STAT1 and

modulation of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci

Res. 95:1582–1601. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Xaus J, Cardo M, Valledor AF, Soler C,

Lloberas J and Celada A: Interferon gamma induces the expression of

p21waf-1 and arrests macrophage cell cycle, preventing induction of

apoptosis. Immunity. 11:103–113. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Bossennec M, Di Roio A, Caux C and

Menetrier-Caux C: MDR1 in immunity: Friend or foe? Oncoimmunology.

7:e14993882018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Cao ZH, Zheng QY, Li GQ, Hu XB, Feng SL,

Xu GL and Zhang KQ: STAT1-mediated down-regulation of Bcl-2

expression is involved in IFN-γ/TNF-α-induced apoptosis in NIT-1

cells. PLoS One. 10:e01209212015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Cheon H and Stark GR: Unphosphorylated

STAT1 prolongs the expression of Interferon-induced immune

regulatory genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:9373–9378. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Morrow AN, Schmeisser H, Tsuno T and Zoon

KC: A novel role for IFN-stimulated gene factor 3II in IFN-γ

signaling and induction of antiviral activity in human cells. J

Immunol. 186:1685–1693. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Clark DN, O'Neil SM, Xu L, Steppe JT,

Savage JT, Raghunathan K and Filiano AJ: Prolonged STAT1 activation

in neurons drives a pathological transcriptional response. J

Neuroimmunol. 382:5781682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yuasa K, Masubuchi A, Okada T, Shinya M,

Inomata Y, Kida H, Shyouji S, Ichikawa H, Takahashi T, Muroi M and

Hijikata T: Interferon-dependent expression of the human STAT1 gene

requires a distal regulatory region located approximately 6 kb

upstream for its autoregulatory system. Genes Cells. 30:e131882025.