Introduction

DEAH box helicase 15 (DHX15), which is a member of

the DEAH box RNA helicase family (1), is involved in several cellular

processes, such as splicing and ribosome biogenesis and facilitates

remodeling of large RNA-protein complexes (2–4). DHX15

was shown to carry out a role in antiviral immune response in

vivo (5). In RNA virus-induced

intestinal inflammation, DHX15 carries out a pivotal role in

controlling inflammation by sensing IFN-β and other cytokines

produced by RNA viruses (6).

Moreover, DHX15 is reported to be involved in tumorigenesis as a

tumor-promoting factor in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and cancer

of the lung, prostate or breast (7–10), but

it also acts as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma and

gastric cancer (11,12). Using gain- and loss-of-function

analyses, we previously revealed that DHX15 suppressed the

proliferation of glioma cell lines (13).

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common

type of cancer, with ~2 million cases diagnosed worldwide in 2020,

and the second most common cause of cancer-related mortality,

according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the

World Health Organization (14).

Repeat analyses of public single-cell sequence and bulk

transcriptome data revealed consistent upregulation of DHX15

expression in patients with CRC (15–17).

Analysis of the clinical pathological features of CRC samples from

the Cancer Gene Atlas and the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis

Consortium revealed that reduced expression of DHX15 mRNA

and DHX15 protein associated with poor CRC prognosis in terms of

survival, metastasis and recurrence (16). Furthermore, the overall survival

positively associated with DHX15 expression levels in CRC (18). Conversely, in a case report of a

patient with CRC harboring a KRAS p.G12D mutation, DHX15 was

implicated as a critical mediator of microbiota-driven pathogenesis

of CRC. Specifically, DHX15 was found to be highly expressed and

functioned as a receptor on tumor cells, facilitating the invasion

of Fusobacterium nucleatum into the nuclei of intestinal

epithelial cells (IECs), thereby promoting tumorigenesis (19). The present study examined the

effects of DHX15 overexpression using CRC cell lines with different

characteristics, including KRAS mutations (19).

Materials and methods

Human clinical samples

Human CRC samples and adjacent normal tissues were

obtained by surgical resection from ten patients with CRC; five

male, average age 60 years (51–65 years), five female, average age

75.6 years (60–91 years) at Juntendo University Hospital (Tokyo,

Japan) between April 2022-August 2025 and embedded in paraffin. The

diagnoses of the ten patients were based on clinical and

pathological examinations (Table

I). Cancer staging was carried out in accordance with the Union

for International Cancer Control TNM classification (20). All human tissues were obtained with

written informed consent and approval from the medical ethical

committee of Juntendo University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan; approval

no. E22-0079).

| Table I.DHX15 expression in human CRC tissues

and clinicopathological factors of the patients with CRC. |

Table I.

DHX15 expression in human CRC tissues

and clinicopathological factors of the patients with CRC.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DHX15

immuno-Histochemical staining |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex | Location | Stage | T | N | M | Histological

type | V | Ly | Adjacent

tissue | Cancer |

|---|

| 1 | 75 | W | C | IIIc | 4a | 2b | 0 | por | 0 | 1c | 48 | 58 |

| 2 | 62 | M | A | IIIb | 3 | 1a | 0 | tub2 | 1c | 0 | 34 | 56 |

| 3 | 82 | W | A | IIIb | 3 | 2a | 0 | tub2 | 1a | 1c | 17 | 74 |

| 4 | 60 | W | T | IIIb | 3 | 1b | 0 | tub1 | 0 | 1a | 47 | 76 |

| 5 | 51 | M | T | II | 3 | 0 | 0 | tub1 | 0 | 1a | 35 | 49 |

| 6 | 91 | W | S | IIIb | 3 | 1a | 0 | tub2 | 1b | 1a | 36 | 77 |

| 7 | 65 | M | S | IIIc | 4a | 3 | 0 | tub2 | 0 | 1a | 21 | 59 |

| 8 | 60 | M | S | II | 3 | 0 | 0 | tub1 | 1a | 0 | 14 | 48 |

| 9 | 62 | M | RS | IIa | 3 | 0 | 0 | tub1 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 57 |

| 10 | 70 | W | RS | II | 3 | 0 | 0 | tub2 | 1c | 1a | 49 | 69 |

Reagents, CRC cell lines, transfection

and cell sorting

Porcupine inhibitor C59 (cat. no. S7037) was

obtained from Selleck Chemicals and the NF-κB inhibitor IMD-0354

(cat. no. HY-10172) was obtained from MedChemExpress. The human CRC

cell lines HCT116 (21), SW480

(22) and Caco2 (23) (provided by Dr Akira Orimo, Juntendo

University, Tokyo, Japan) were cultured in low glucose DMEM

(Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and DLD1 cells (24) (provided by Dr Akira Orimo, Juntendo

University, Tokyo, Japan) were cultured in RPMI1640 (Nacalai

Tesque, Inc.); both culture media were supplemented with 10% FBS

(MilliporeSigma) and penicillin-streptomycin (MilliporeSigma). The

characteristics of the four CRC cell lines are summarized in

(Table SI) (25).

HCT116, SW480, Caco2 and DLD1 cells

(1.5×106 cells) were seeded on 10-cm plates (Nippon Gene

Co., Ltd.) and transfected using GeneJuice Transfection Reagent

(Cat. no. 70967-3CN; Merck KGaA) with a combination of the plasmids

pMXs-IP (control vector) or pMX-DHX15 and EGFP expression

(pCAG-EGFP), at DNA amounts of 0.03 µg for pCAG-EGFP and 0.21 µg

for pMXs-IP or pMX-DHX15 per well. The cells were harvested at 37°C

after 12 h of culture and EGFP-positive cells were collected using

a cell sorter (FACS ARIA III, BD Biosciences). Total RNA was

purified using Trizol® reagent (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

(RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was carried out as previously described

(26). The expression levels of the

transcripts of interest were normalized using GAPDH and

ACTB values. The respective forward and reverse primer

sequences were as follows: human ACTB:

5′-GAAGGAGATCACTGCCCTGG-3′ and 5′-ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC-3′;

GAPDH: 5′-ATTGCCCTCAACGACCACTT-3′ and

5′-TGGTCCAGGGGTCTTACTCC-3′; DHX15:

5′-TGCTGAACGTCTACCATGCTT-3′ and 5′-ATTCGAGATAGCTGCTGGCG-3′;

IRF1: 5′-AAGGGGTGTGGCCTTTTTAGA-3′ and

5′-TGTCCCTGTTCACCCCAAAG-3′; IRF3: 5′-CCTGCACATTTCCAACAGCC-3′

and 5′-AATCCATGCCCTCCACCAAG-3′: IRF7:

5′-GCTCCCCACGCTATACCATC-3′ and 5′-CAGGGAAGACACACCCTCAC-3′;

NFKB1: 5′-GTGAAGACCACCTCTCAGGC-3′ and

5′-CTGTCGCAGACACTGTCACT-3′; NFKB2:

5′-ACGCCTCTTGACCTCACTTG-3′ and 5′-GTGGCTCCATGGTGTTCTGA-3′;

RELA: 5′-GGACATGGACTTCTCAGCCC-3′ and

5′-AAAGTTGGGGGCAGTTGGAA-3′; and REL:

5′-TCCTTAGCCCAGCCATCTCT-3′ and 5′-GGCAGTCTCCGCTCATCTTT-3′.

Immunohistochemistry

DHX15 protein expression in human clinical samples

was examined by immunohistochemistry using an anti-DDX15 antibody

(H-4, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; cat. no. sc-271686).

Paraffin-embedded 3-µm sections were first deparaffinized with EZ

Prep (cat. no. 950-102) and subjected to antigen retrieval using

Cell Conditioner #2 (pH 9.0; cat. no. 950-223) on a BenchMark Ultra

automated stainer (Roche Tissue Diagnostics). After antigen

retrieval, the sections were incubated with the primary anti-DDX15

antibody at 37°C for 1 h.

Primary antibody signals were then detected using

the UltraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Roche Tissue

Diagnostics, cat. no. 760-500) under standard BenchMark Ultra

settings, including an 8-min incubation with the HRP-conjugated

multimer reagent, followed by DAB chromogen visualization.

Counterstaining was performed with Hematoxylin II for 8 min and

Bluing Reagent for 4 min at 37°C. Stained sections were observed

using a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss GmbH),

and images were acquired using ZEN software (version 3.12; Zeiss

GmbH).

Stained samples were observed using Zeiss Axio

Imager M2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss GmbH) and images were

acquired using ZEN software (ZEN3.12; Zeiss GmbH). For

quantification of DHX15 positive signals, we used ImageJ (version

1.54p; National Institutes of Health). The images were imported to

ImageJ and DAB signals were isolated using the color deconvolution

command of ImageJ. DAB images were converted to gray scale binary

images, and doublet cells were separated by the Watershed command

and positive and negative cells were counted. To quantify intensity

of the signals, the log10 value of mean of sample ROI vs. mean of

background ROI by using 8-bit index color was calculated.

Immunohistochemistry of the cultured cells was

carried out as described previously (27). The primary antibodies used were

mouse monoclonal antibodies against Ki67 (1:250; cat. no. 55060;

BD); LC3 (1:2,000; cat. no. M152-3; MEDICAL & BIOLOGICAL

LABORATORIES CO., LTD.); rabbit polyclonal antibody against active

Caspase-3 (AC3; 1:250; cat. no. 9664S; Promega Corporation); and

chicken polyclonal antibody against GFP (1:2,000; cat. no. ab13970;

Abcam). Appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa

Fluor 488 (1:500; cat. no. A11039; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

or Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500; cat. no. C10639; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) were used. The nuclei were visualized using DAPI.

Stained cells were observed using Zeiss Axio Imager I fluorescence

microscope (Zeiss GmbH) and images were acquired using ZEN software

(version, 3.12; Zeiss GmbH).

Luciferase reporter assay for

Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways

Luciferase reporter assays for the Wnt/β-catenin and

NF-κB signaling pathways were performed using TCF-luc (IFN minimal

promoter with 7× TCF-binding sites driving firefly luciferase) and

NFκB-luc (SV40 early promoter with 8× NF-κB-binding sites driving

firefly luciferase) (28). These

plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. K. Shimotono (Kyoto

University, Kyoto, Japan) and Dr. R. Tsuruta (University of Tokyo,

Tokyo, Japan), respectively. No 3′ UTR reporter constructs and no

miRNA mimics or inhibitors were used in this study. Cells were

transfected with the reporter plasmids using GeneJuice Transfection

Reagent (cat. no. 70967-3CN; MilliporeSigma) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase activity was measured 18 h

after transfection using a luminometer (Lumat LB9507;

Titertek-Berthold) and the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, cat.

no. E1500). Because only firefly luciferase reporters were used,

luciferase activity was analyzed without Renilla luciferase

normalization.

Cell proliferation assay

SW480 (1×104cell/well), Caco2

(1×104 cell/well), HCT116 (2×104 cells) and

DLD1 (2×104 cells) cells were plated on 48-well plates

(Corning, Inc.) and then transfected with a combination of plasmids

pMXs-IP (control vector) or pMX-DHX15 and pCAG-EGFP using GeneJuice

(cat. no. 70967-3CN; MilliporeSigma). After 1 h of incubation, the

plate was set on IncuCyte ZOOM (Sartorius AG). Live-cell images

were captured every 8 h and analyzed using IncuCyte Live-Cell

Imaging Software (v2024B).

To evaluate the time-dependent changes in the number

of GFP-positive cells after transfection, cells were monitored

using an Incucyte live-cell imaging system under standard culture

conditions (37°C; 5% CO2) at 8-h intervals immediately

after plating.

Cell proliferation was examined by incorporating

5-ethynyl 2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) using Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594

Imaging kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After transfecting

the cells as aforementioned, EdU was added to the culture at a

final concentration of 10 µM and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. For

inhibitor experiments, cells were treated with the Wnt inhibitor

C59 (10 µM) or the NF-κB inhibitor IMD-0354 (5 µM) at 37°C for 2 h

prior to EdU addition. The incorporated EdU signals were visualized

by immunostaining with a chicken polyclonal antibody against GFP

(cat. no. ab13970; 1:2,000; Abcam) at room temperature overnight

and a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 at room

temperature for 30 min (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

EGFP was immunostained with an anti-GFP antibody (1:2,000; cat. no.

ab13970; Abcam). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Stained cells were

observed using Zeiss Axio Imager I (Zeiss GmbH) and images were

acquired using ZEN software (Zeiss GmbH).

Western blotting

Cell lysates were collected from cell lines

(2×106 cells) and analyzed by western blotting, as

previously described (29). Protein

was extracted using RIPA buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), containing

50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium

deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS, supplemented with protease inhibitor

cocktail (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.).

Protein concentration was determined using the BCA

assay (Nacalai Tesque, Inc..) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Equal amounts of protein (3 µg per lane) were mixed with

4× Laemmli sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and boiled at 98°C

for 5 min before electrophoresis. Proteins were separated on 10%

SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes.

Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad) in

TBS-Tween (0.1%) at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were

incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, followed by

incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room

temperature. Signals were detected using Chemi-Lumi One Super

(Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). The primary antibodies used were mouse

monoclonal antibodies against ACTIN (1:1,000; cat. no. A4700;

MilliporeSigma) and DDX15 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-271686; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). The secondary antibody used was HRP-linked

secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. NA931; Cytiva).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was calculated by an

unpaired Student's t test (two tailed). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01. Experiments were conducted in triplicate. Data are

shown as mean ± standard deviation)

Results

DHX15 expression in human CRC

tissues

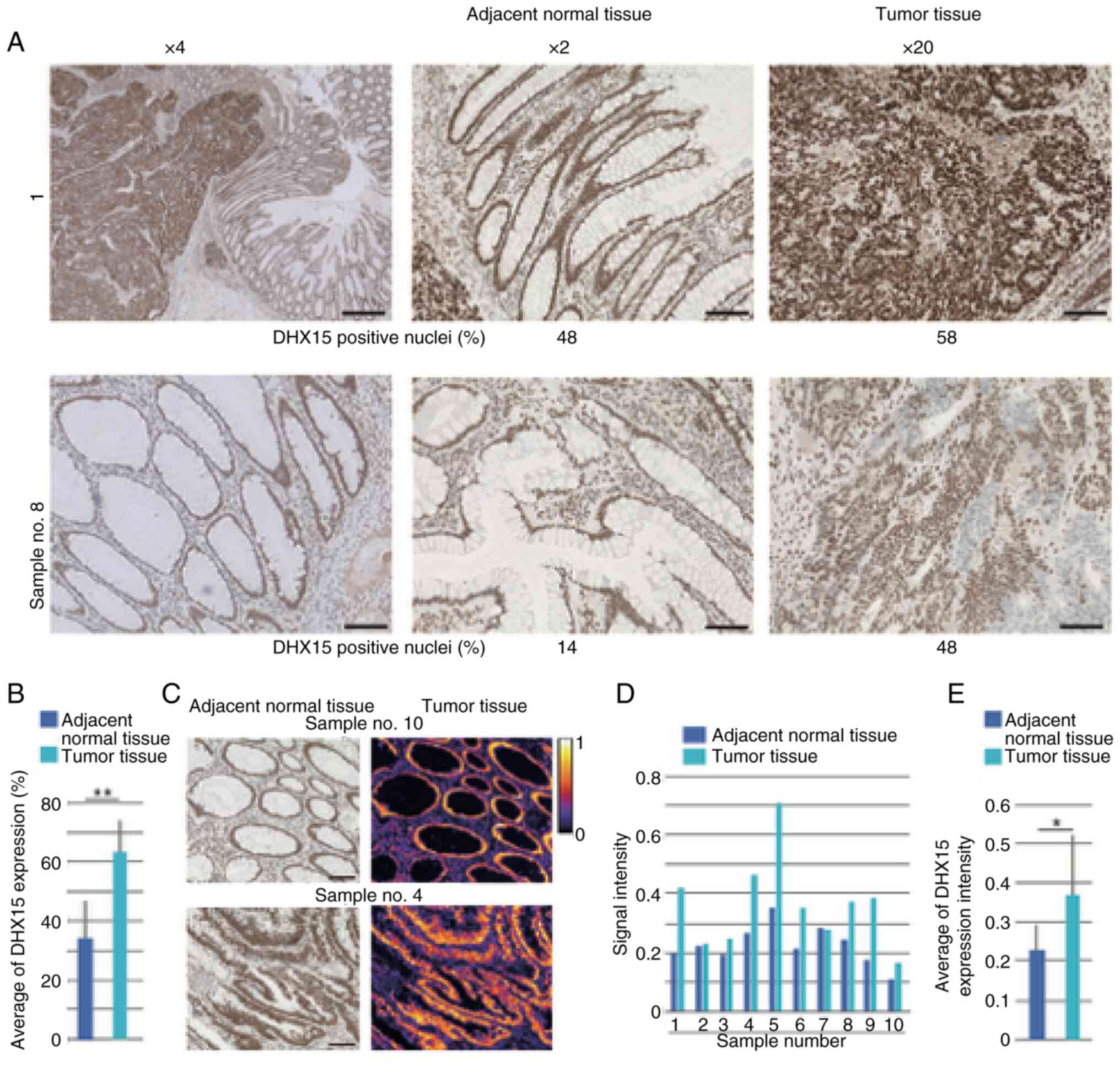

On examination of the clinical samples, DHX15

protein was detectable in the cell nuclei in both tumor and

adjacent normal tissues of all 10 patients (Fig. 1A). The evaluation values of DHX15

expression strength for all 10 samples are summarized (Table I). The average positive nuclei

staining of DHX15 in the ten tumor samples was increased compared

with that of adjacent tissue (Fig.

1B). Among the CRC tissues, four showed >60% of DHX15

positive signals in tumor tissues, but there was no correlation

between clinicopathological factors and DHX15 staining intensity

(Table I). Heat-map (Fig. 1C) represents intensity of DHX15

immunostaining of adjacent normal tissue and tumor tissue (Fig. 1D). Again, clear association between

pathological observation and signal intensity was not found, but

the average DHX15 expression intensity in the tumor region was

increased compared with that in adjacent tissue (Fig. 1E).

Effects of DHX15 overexpression on the

proliferation of CRC cell lines

DHX15 protein expression levels were first examined

in the CRC cell lines HCT116, SW480, Caco2 and DLD1 using western

blotting of whole protein. All cell lines express DHX15 with

expected size (Fig. S1A; upper

bands). Subsequently, the cells were co-transfected with

DHX15-expression vector or empty control vector together with

EGFP-expression plasmid and EGFP positive cells were purified by a

cell sorter after 12 h of culture. Overexpression of DHX15

transcripts was confirmed by RT-qPCR in all four cell lines

(Fig. S1B).

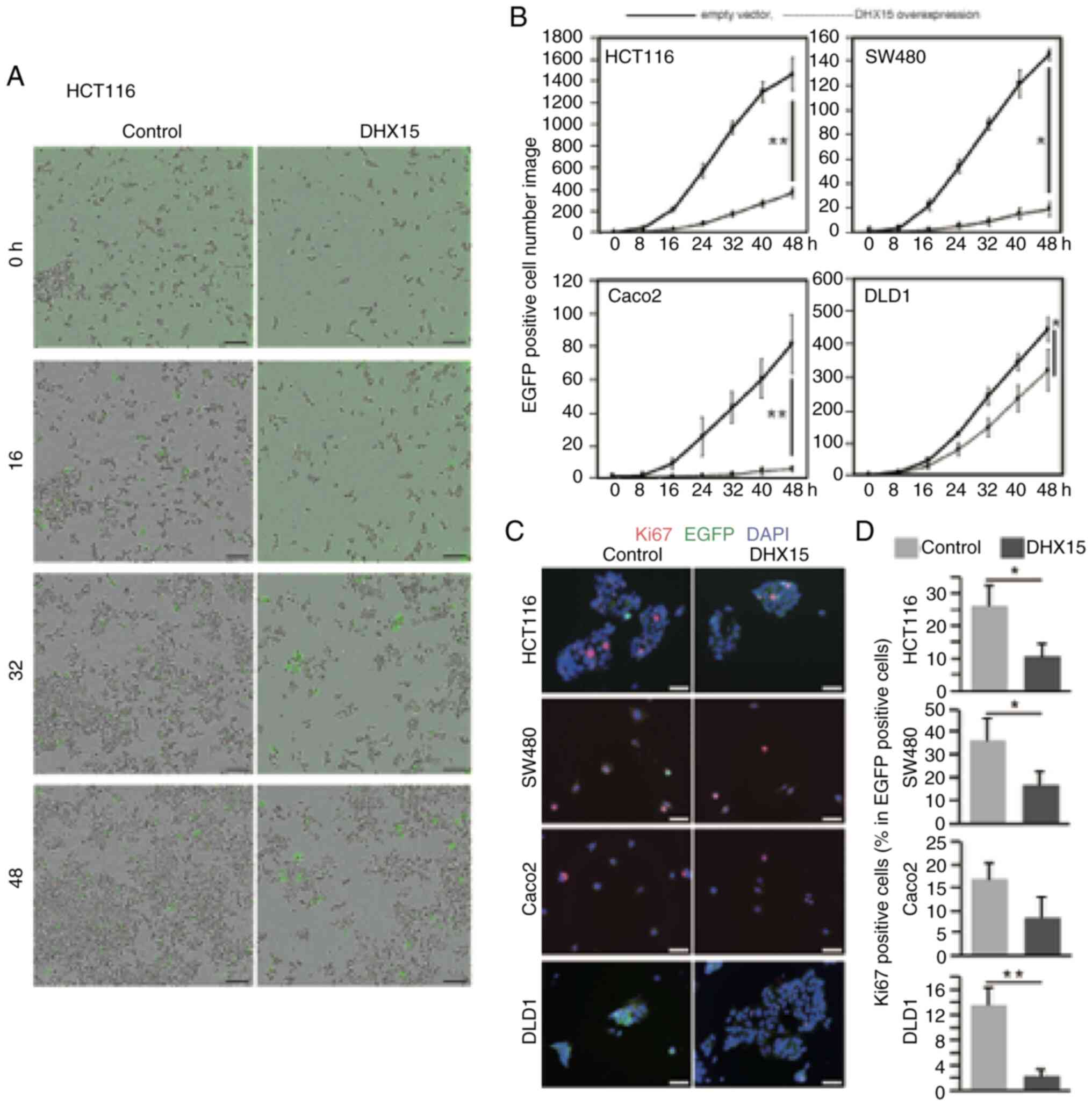

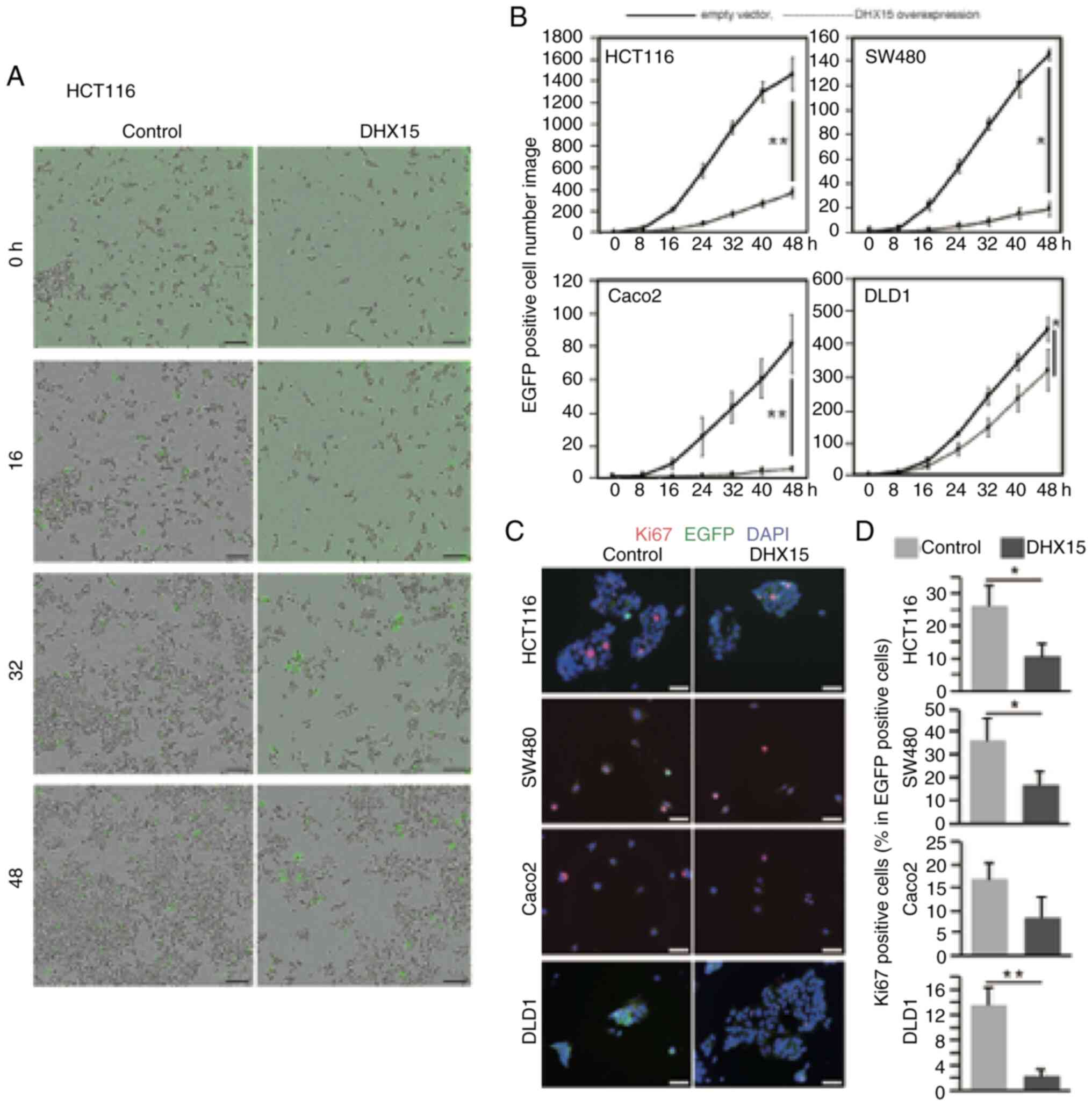

To examine the effects of DHX15 overexpression on

proliferation, the cells were cotransfected with DHX15-expressing

vector or empty control vector with EGFP-expression plasmid. The

transfected cells were cultured for 2 days, and the number of

EGFP-positive cells was counted over time using IncuCyte live-cell

imaging. The number of EGFP-positive cells is shown on Fig. 2A and B. Compared with the control

samples, samples with DHX15 overexpression had a significantly

reduced cell number in all the examined CRC cell lines (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that

DHX15 suppressed cell proliferation.

| Figure 2.Effects of DHX15 overexpression on

the proliferation of various CRC cell lines. The CRC cell lines

HCT116, SW480, Caco2 and DLD1 were transfected with

DHX15-expressing or empty vector with EGFP-expressing vector. The

cells were incubated in IncuCyte ZOOM, and live-cell images were

captured every 8 h. (A) The population of EGFP positive cells was

analyzed using IncuCyte Live-Cell Imaging Software. The captured

images of HCT116 of control and DHX15 overexpressed cells at 0, 16,

32 and 48 h after transfection. (B) Transition of number of EGFP

positive cells from 0 to 48 h after transfection of empty vector or

DHX15 overexpression vector. Cell proliferation was examined by

Ki67 immunostaining. Transfected cells were cultured for 24 h,

followed by immunostaining with an anti-Ki67 antibody. (C)

Representative images, DAPI (blue) shows nucleus. (D) Population of

Ki67 positive cells in total EGFP positive cells in the 4 cell

lines. Scale bar, 100 µm in A and C. Data are average of 3

independent samples with SEM. Statistical significance was

calculated by Student's t test (two tailed). *P<0.01;

**P<0.01. DHX15, DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-His) box helicase 15; CRC,

colorectal cancer. |

The number of Ki67-positive proliferating HCT116,

SW480 and DLD1 cells was significantly reduced after transfection

with DHX15 and EGFP-expression plasmid (Fig. 2C and D). The EdU incorporation assay

revealed that DHX15 overexpression significantly reduced the number

of EdU-positive cells in all four CRC cell lines (Fig. S2A and B). These results suggested

that DHX15 suppressed the proliferation of CRC cell lines.

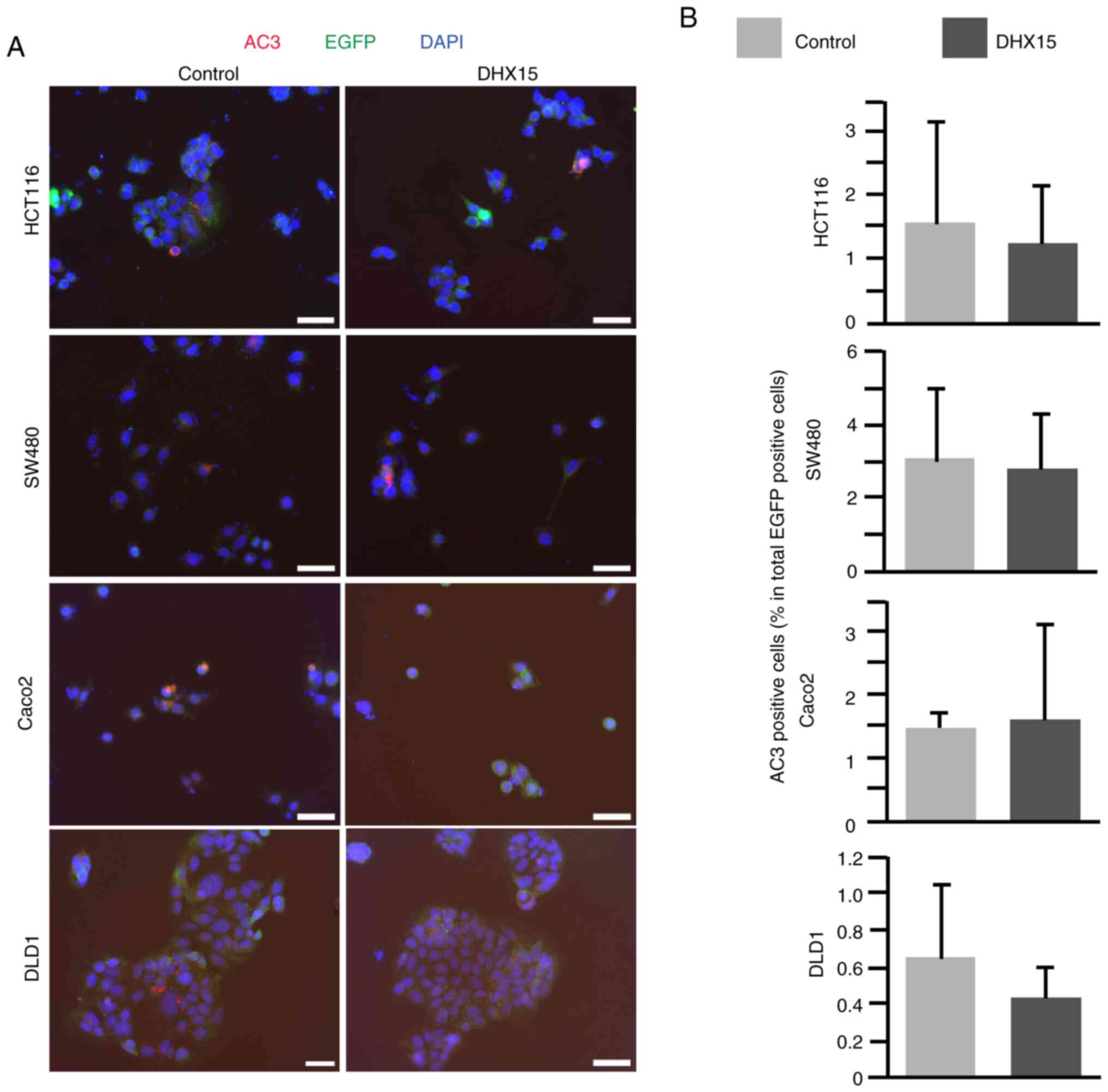

Next, the DHX15-overexpressing CRC cell lines were

investigated using the immunohistochemistry apoptosis marker AC3.

The cells were cotransfected with either the empty control or

DHX15-expressing vector with EGFP-expression plasmid and

immunostaining was carried out after 2 days of culture. The number

of AC3-positive apoptotic cells was comparable between the control

and DHX15-transfected cells in the four CRC cell lines, except

HCT116, which showed slight decrease in AC3-positive cells in the

DHX15 overexpression group, although this was not significant

(Fig. 3A and B). These results

indicated that DHX15 overexpression may not affect apoptosis in the

CRC cell lines.

Examination of the possible

involvement of Wnt, NF-κB and autophagy in DHX15-overexpressing

cells

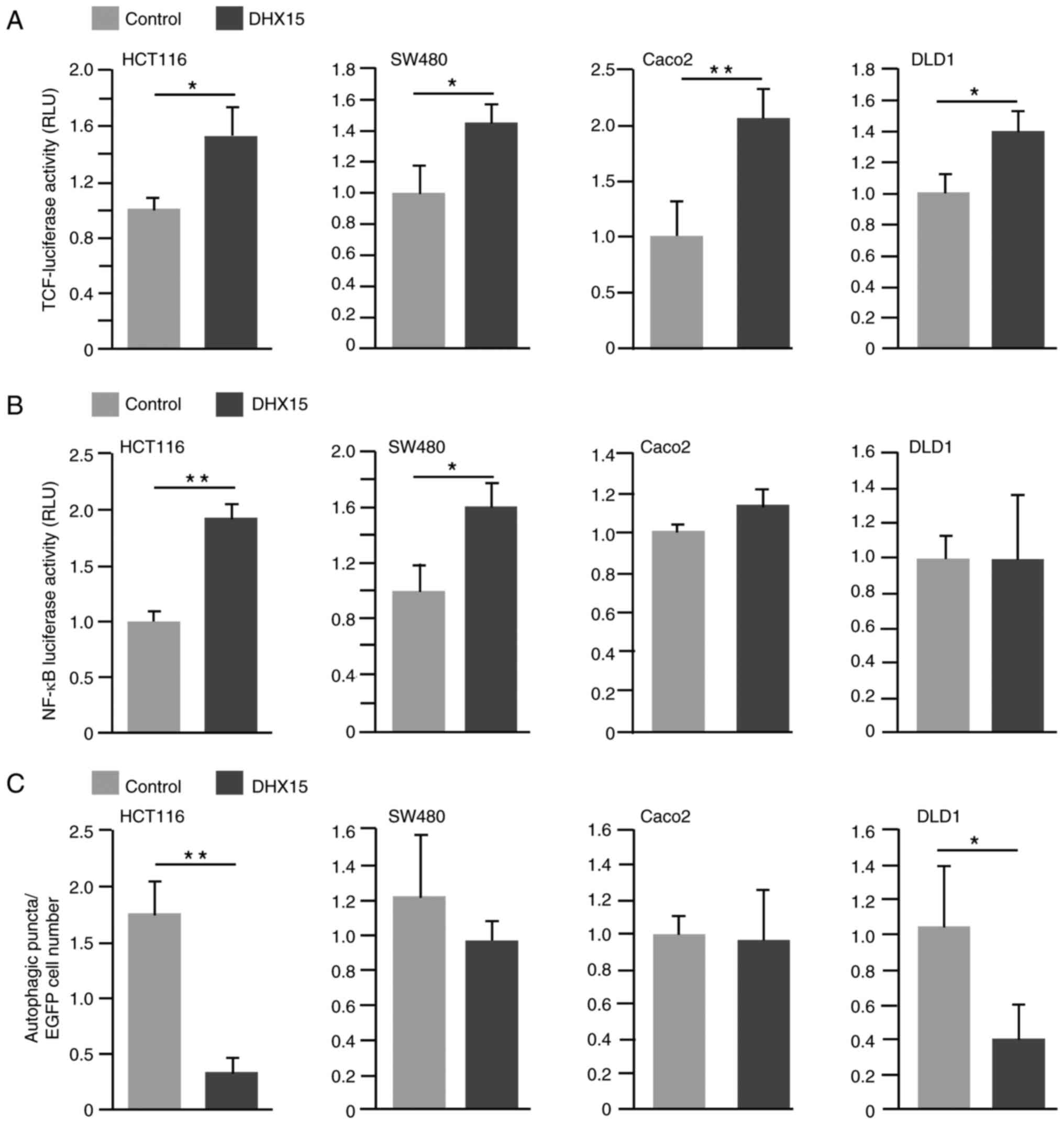

To investigate the potential mechanisms underlying

this finding, the involvement of the Wnt and NF-κB signaling

pathways were examined, as well as autophagy, in

DHX15-overexpressing cells. These pathways have previously been

reported to play key roles in the regulation of cell proliferation

(11,30,31).

Analysis revealed that DHX15 overexpression significantly induced

luciferase activities that were dependent on the TCF-binding motif

in all examined CRC cells (Fig.

4A). The effects of the Wnt signaling inhibitor C59 on the

proliferation of CRC cell lines with overexpressed DHX15 were

investigated using EdU incorporation assay. Analysis revealed a

tendency for higher EdU incorporation in HCT116 and SW480 cells

when compared with control cells (Fig.

S3A and B).

On examination of NF-κB signaling using a NF-κB

target site-dependent luciferase assay, DHX15 overexpression

enhanced luciferase activity in HCT116 and SW480 cells; however, in

Caco2 and DLD1 cells, luciferase activity was similar between the

control and DHX15-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4B). On examination of NF-κB-related

gene expression by RT-qPCR in HCT116 and SW480 cells, the control

and DHX15-overexpressing cells revealed similar transcript levels

of genes, except for IRF3 and REL in SW480 cells

(Fig. S4). Examination of the

effects of the NF-κB inhibitor IMD-0354 revealed that the number of

EdU-positive cells was not significantly different between

DHX15-transfected and IMD-0354 treated cells in all four CRC cell

lines (Fig. S5A and B).

The expression pattern of LC3 puncta, which is an

autophagy marker (32), was

subsequently examined. Upon counting the LC3-positive puncta in the

nuclei of control and DHX15-overexpressing cells, DHX15

overexpression led to a reduced number of LC3-positive signals in

HCT116 and DLD1 cells but not in SW480 and Caco2 cells (Figs. 4C and S6).

Discussion

The present study investigated the role of DHX15 in

CRC by examining DHX15 expression levels in clinical samples and

changes in DHX15 levels in CRC cell lines. In the clinical samples

from 10 patients with CRC, DHX15 expression levels varied. The

absence of a clear association between clinicopathological factors

and intensity of DHX15 expression was likely attributable to the

small sample size (n=10 patients). Further analysis of DHX15

expression using additional clinical samples may help clarify its

relationship with clinicopathological factors. Although the

relationship between DHX15 expression levels and tumor malignancy

remains inconclusive, the quantification of its expression may

provide a potential prognostic indicator, such as recurrence or

reduced survival in cases with low DHX15 expression. At present, to

the best of our knowledge, no association has been observed between

DHX15 expression and tumor stage. In addition, we hypothesize that

there is a possibility that the DHX15 expression patterns and

levels are associated with disease progression which may be

revealed by monitoring the condition of patients continuously and

carefully. Conversely, analysis revealed that DHX15 upregulation

hampered the proliferation activity of all examined CRC cell lines.

This result is consistent with a recent study which revealed that

DHX15 inhibits CRC progression, invasion and metastasis (18). In the present study, all CRC cell

lines examined exhibited endogenous DHX15 expression. Therefore,

further forced overexpression of DHX15 may have exceeded the

physiological threshold, leading to cytotoxicity. Such

supraphysiological expression levels could disrupt essential

cellular processes, ultimately resulting in growth suppression.

Mutation in the well-known protooncogene KRAS is found in

HCT116, SW480 and DLD1 cell lines but not in Caco2 cells;

therefore, the DHX15 effects observed in the present study were

likely not associated with KRAS mutation. However,

evaluation of DHX15 protein expression patterns and their

relationship with clinicopathological factors in hepatocellular

carcinoma revealed that DHX15 was markedly upregulated, and its

high expression associated with poor prognosis (33). Taken together with the reports of

other types of cancer, we hypothesize that the effects on DHX15

expression levels to cancer prognosis depend on the types of

cancer.

Among the various mechanisms of DHX15 activity, Wnt

involvement has been reported in different model systems. In one

study that analyzed the role of DHX15 in antibacterial responses in

IECs, mice with DHX15 deletion in IECs were susceptible to

infection with enteric bacteria because of low levels of α

defensin, which is an antimicrobial peptide; considering that α

defensin is induced by the TLR/Wnt pathways this study suggested

that DHX15 regulates TLR/Wnt signals (34). Another study revealed that DHX15

regulates zebrafish intestinal development through the Wnt

signaling pathway (35). The

present study revealed that DHX15 overexpression significantly

induced Wnt signaling in the four CRC cell lines; however,

inhibition of Wnt signaling did not prevent the suppressed

proliferation of DHX15-overexpressing cells. Furthermore, given its

well-known contribution to the development and progression of

various tumors (36,37), Wnt signaling was less likely to

participate in the suppression of cell proliferation by DHX15.

However, other physiological processes, such as metastasis, were

not analyzed in the present study and requires in vivo

clarification in future research.

DHX15 acts as an immune modulator through regulation

of NF-κB. Human DHX15 contributes to activation of the NF-κB, JNK

and p38 MAPK pathways in HeLa cells in response to the synthetic

double-stranded RNA analog poly(I:C) (5). In acute myeloid leukemia, DHX15 is

downregulated in disease remission or cell line differentiation

(7). Furthermore, knockdown of

DHX15 inhibits nuclear translocation and activation of the

NF-κB subunit P65 in leukemia cells (7). Positive feedback of NF-κB and DHX15

was reported in breast cancer cells (10). The present study revealed that DHX15

overexpression induced NF-κB signaling in HCT116 and SW480 cells,

but the expression levels of known downstream target genes of the

NF-κB pathway were not upregulated. Furthermore, NF-κB inhibition

by the IMD-0354 did not affect cell proliferation, suggesting the

need to clarify the signaling pathways and biological roles of

DHX15 using cell lines in the future.

Involvement of autophagy in cancer progression has

been reported in various types of cancer (38–41).

DHX15 negatively regulates autophagy in association with mTORC1

activation in hepatoma cells (11).

There have been several reports on KRAS-activating mutations

and autophagy. KRAS-activating mutations increase autophagy

and contribute to the survival of CRC cells under starvation

conditions (42). In addition,

autophagy was induced to different degrees, depending on mutations

of the KRAS allele (42). In

the present study, given the decreased number of LC3 puncta in

HCT116 and DLD1 cells, which have a KRASG13D/−

mutation, a relationship between KRAS mutation and autophagy

was suspected. However, the contribution of this pathway to cell

proliferation remains unclear. The effects of other signaling

pathway inhibitors were also explored using this experimental model

(data not shown). Preliminary experiments were performed with

various inhibitor concentrations, and cell proliferation was

assessed by EdU immunostaining. No significant differences were

observed between the groups. However, because the efficacy of the

inhibitor itself was not fully confirmed, these data are not

included in the present study. Experiments in which knockdown of

DHX15 is achieved by siRNA oligonucleotide are planned as future

work.

Although the present study did not yield fully

conclusive mechanistic results, it provides novel evidence that

DHX15 overexpression suppresses colorectal cancer cell

proliferation and highlights DHX15 as a previously under-recognized

regulator of tumor biology. These findings offer a foundation for

future mechanistic studies and suggest that DHX15 may serve as a

potential biomarker or therapeutic target in colorectal cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kanji Uchida

(Department of Anesthesiology, University of Tokyo Hospital, Tokyo,

Japan) for discussions and allowing the use of IncuCyte in their

department.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

YI and KoS performed the experiments, TI, SI, KoS,

KiS, KaS and SW designed the research, YI and SW wrote the

manuscript. SW contributed to the study conception, experimental

design, data interpretation, and provided critical revisions of the

manuscript. YI and SW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All human tissues were obtained with written

informed consent and approval from the medical ethical committee of

Juntendo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan (approval no.

E22-0079).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DHX15

|

DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-His) box helicase

15

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

IEC

|

epithelial cell

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

TCF-luc

|

TCF-binding site luciferase

|

|

NFκB-luc

|

NF-κB binding sites luciferase

|

References

|

1

|

Linder P: Dead-box proteins: A family

affair-active and passive players in RNP-remodeling. Nucleic Acids

Res. 34:4168–4180. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Arenas JE and Abelson JN: Prp43: An RNA

helicase-like factor involved in spliceosome disassembly. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 94:11798–11802. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Combs DJ, Nagel RJ, Ares M Jr and Stevens

SW: Prp43p is a DEAH-box spliceosome disassembly factor essential

for ribosome biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 26:523–534. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tanaka N, Aronova A and Schwer B: Ntr1

activates the Prp43 helicase to trigger release of lariat-intron

from the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 21:2312–2325. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mosallanejad K, Sekine Y,

Ishikura-Kinoshita S, Kumagai K, Nagano T, Matsuzawa A, Takeda K,

Naguro I and Ichijo H: The DEAH-box RNA helicase DHX15 activates

NF-κB and MAPK signaling downstream of MAVS during antiviral

responses. Sci Signal. 7:ra402014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xing J, Zhou X, Fang M, Zhang E, Minze LJ

and Zhang Z: DHX15 is required to control RNA virus-induced

intestinal inflammation. Cell Rep. 35:1092052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pan L, Li Y, Zhang HY, Zheng Y, Liu XL, Hu

Z, Wang Y, Wang J, Cai YH, Liu Q, et al: DHX15 is associated with

poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and regulates cell

apoptosis via the NF-kB signaling pathway. Oncotarget.

8:89643–89654. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yao G, Chen K, Qin Y, Niu Y, Zhang X, Xu

S, Zhang C, Feng M and Wang K: Long non-coding RNA JHDM1D-AS1

interacts with DHX15 protein to enhance non-small-cell lung cancer

growth and metastasis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 18:831–840. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jing Y, Nguyen MM, Wang D, Pascal LE, Guo

W, Xu Y, Ai J, Deng FM, Masoodi KZ, Yu X, et al: DHX15 promotes

prostate cancer progression by stimulating Siah2-mediated

ubiquitination of androgen receptor. Oncogene. 37:638–650. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zheng W, Wang X, Yu Y, Ji C and Fang L:

CircRNF10-DHX15 interaction suppressed breast cancer progression by

antagonizing DHX15-NF-κB p65 positive feedback loop. Cell Mol Biol

Lett. 28:342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao M, Ying L, Wang R, Yao J, Zhu L,

Zheng M, Chen Z and Yang Z: DHX15 inhibits autophagy and the

proliferation of hepatoma cells. Front Med (Lausanne).

7:5917362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zong Z, Li H, Ning Z, Hu C, Tang F, Zhu X,

Tian H, Zhou T and Wang H: Integrative bioinformatics analysis of

prognostic alternative splicing signatures in gastric cancer. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 11:685–694. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ito S, Koso H, Sakamoto K and Watanabe S:

RNA helicase DHX15 acts as a tumour suppressor in glioma. Br J

Cancer. 117:1349–1359. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lv X, Ma W, Miao X, Hu S and Xie H:

Navigating colorectal cancer prognosis: A Treg-related signature

discovered through single-cell and bulk transcriptomic approaches.

Environ Toxicol. 39:3512–3522. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lu P, Zhang Y, Cui Y, Liao Y, Liu Z, Cao

ZJ, Liu JE, Wen L, Zhou X, Fu W and Tang F: Systematic

characterization of full-length RNA isoforms in human colorectal

cancer at single-cell resolution. Protein Cell. 16:873–895. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tao Y, Li J, Pan J, Wang Q, Ke RW, Yuan D,

Wu H, Cao Y and Zhao L: Integration of scRNA-Seq and bulk RNA-Seq

identifies circadian rhythm disruption-related genes associated

with prognosis and drug resistance in colorectal cancer patients.

Immunotargets Ther. 14:475–489. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Fan L, Guo X, Zhang J, Wang Y, Wang J and

Li Y: Relationship between DHX15 expression and survival in

colorectal cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 115:234–240. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhu H, Li M, Bi D, Yang H, Gao Y, Song F,

Zheng J, Xie R, Zhang Y, Liu H, et al: Fusobacterium nucleatum

promotes tumor progression in KRAS p.G12D-mutant colorectal cancer

by binding to DHX15. Nat Commun. 15:16882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Huang SH and O'Sullivan B: Overview of the

8th edition TNM classification for head and neck cancer. Curr Treat

Options Oncol. 18:402017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rajput A, Martin ID, Rose R, Beko A, Levea

C, Sharratt E, Mazurchuk R, Hoffman RM, Brattain MG and Wang J:

Characterization of HCT116 human colon cancer cells in an

orthotopic model. J Surg Res. 147:276–281. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Verhagen MP, Xu T, Stabile R, Joosten R,

Tucci FA, van Royen M, Trerotola M, Alberti S, Sacchetti A and

Fodde R: The SW480 cell line as a model of resident and migrating

colon cancer stem cells. iScience. 27:1106582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sambuy Y, De Angelis I, Ranaldi G, Scarino

ML, Stammati A and Zucco F: The Caco-2 cell line as a model of the

intestinal barrier: Influence of cell and culture-related factors

on Caco-2 cell functional characteristics. Cell Biol Toxicol.

21:1–26. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dexter DL, Spremulli EN, Fligiel Z,

Barbosa JA, Vogel R, VanVoorhees A and Calabresi P: Heterogeneity

of cancer cells from a single human colon carcinoma. Am J Med.

71:949–956. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ahmed D, Eide PW, Eilertsen IA, Danielsen

SA, Eknæs M, Hektoen M, Lind GE and Lothe RA: Epigenetic and

genetic features of 24 colon cancer cell lines. Oncogenesis.

2:e712013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Saita K, Moriuchi Y, Iwagawa T, Aihara M,

Takai Y, Uchida K and Watanabe S: Roles of CSF2 as a modulator of

inflammation during retinal degeneration. Cytokine. 158:1559962022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Koso H, Yi H, Sheridan P, Miyano S, Ino Y,

Todo T and Watanabe S: Identification of RNA-binding protein LARP4B

as a tumor suppressor in glioma. Cancer Res. 76:2254–2264. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tsuruta L, Lee HJ, Masuda ES, Yokota T,

Arai N and Arai K: Regulation of expression of the IL-2 and IL-5

genes and the role of proteins related to nuclear factor of

activated T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 96:1126–1135. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kuribayashi H, Iwagawa T, Murakami A,

Kawamura T, Suzuki Y and Watanabe S: NMNAT1 is essential for human

iPS cell differentiation to the retinal lineage. Invest Ophthalmol

Vis Sci. 65:372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kabiri Z, Greicius G, Zaribafzadeh H,

Hemmerich A, Counter CM and Virshup DM: Wnt signaling suppresses

MAPK-driven proliferation of intestinal stem cells. J Clin Invest.

128:3806–3812. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jiao L, Jiang M, Liu J, Wei L and Wu M:

Nuclear factor-kappa B activation inhibits proliferation and

promotes apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. Vascular.

26:634–640. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Levine B and Kroemer G: Biological

functions of autophagy genes: A disease perspective. Cell.

176:11–42. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Xie C, Liao H, Zhang C and Zhang S:

Overexpression and clinical relevance of the RNA helicase DHX15 in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 84:213–220. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang Y, He K, Sheng B, Lei X, Tao W, Zhu

X, Wei Z, Fu R, Wang A, Bai S, et al: The RNA helicase Dhx15

mediates Wnt-induced antimicrobial protein expression in Paneth

cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 118:e20174321182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yao J, Cai Y, Chen Z, Wang X, Lai X, Pan

L, Li Y and Wang S: Dhx15 regulates zebrafish intestinal

development through the Wnt signaling pathway. Genomics.

115:1105782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yu F, Yu C, Li F, Zuo Y, Wang Y, Yao L, Wu

C, Wang C and Ye L: Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancers and targeted

therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:3072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ge X and Wang X: Role of Wnt canonical

pathway in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 3:332010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chang SH, Huang SW, Wang ST, Chung KC,

Hsieh CW, Kao JK, Chen YJ, Wu CY and Shieh JJ: Imiquimod-induced

autophagy is regulated by ER stress-mediated PKR activation in

cancer cells. J Dermatol Sci. 87:138–148. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Russell RC and Guan KL: The multifaceted

role of autophagy in cancer. EMBO J. 41:e1100312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jalali P, Shahmoradi A, Samii A,

Mazloomnejad R, Hatamnejad MR, Saeed A, Namdar A and Salehi Z: The

role of autophagy in cancer: From molecular mechanism to

therapeutic window. Front Immunol. 16:15282302025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Niu X, You Q, Hou K, Tian Y, Wei P, Zhu Y,

Gao B, Ashrafizadeh M, Aref AR, Kalbasi A, et al: Autophagy in

cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug

Resist Updat. 78:1011702025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Alves S, Castro L, Fernandes MS, Francisco

R, Castro P, Priault M, Chaves SR, Moyer MP, Oliveira C, Seruca R,

et al: Colorectal cancer-related mutant KRAS alleles function as

positive regulators of autophagy. Oncotarget. 6:30787–30802. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|