Introduction

Melanoma, a malignancy arising from melanocytes,

demonstrates a rising global incidence, although a concurrent

decline in mortality has been observed in recent years (1). Histopathologically, melanomas have

been classically categorized into three main subtypes based on the

presence of a radial growth phase: Nodular melanoma, superficial

spreading melanoma and lentigo maligna melanoma (2).

Melanomas were divided into those etiologically

related to sun exposure and those that are not, as determined by

their mutational signatures, anatomic site and epidemiology.

Melanomas on the sun-exposed skin were further divided by the

histopathologic degree of cumulative solar damage (CSD) of the

surrounding skin, into low and high CSD, on the basis of degree of

associated solar elastosis. Low-CSD melanomas include superficial

spreading melanomas and high-CSD melanomas incorporate lentigo

maligna and desmoplastic melanomas. The ‘nonsolar’ category

includes acral melanomas, some melanomas in congenital nevi,

melanomas in blue nevi, Spitz melanomas, mucosal melanomas and

uveal melanomas (3).

Furthermore, an increased number of melanocytic nevi

and the presence of atypical nevi are established risk factors for

melanoma development. Notably, the presence of multiple atypical

nevi is associated with a six-fold increase in the risk of melanoma

formation, a stronger association compared to the presence of a

single atypical nevus (4).

Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for

early-stage disease. However, melanoma is highly aggressive and

prone to distant metastasis. For patients with stage IV melanoma,

where the disease is generally no longer amenable to curative

surgical resection, systemic therapy thus becomes particularly

crucial. Currently approved first-line regimens for advanced

melanoma include programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitors

as monotherapy, nivolumab plus relatlimab, and ipilimumab combined

with nivolumab, and for patients with BRAF mutation, combination

BRAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK) inhibitor

therapy (5). Nevertheless, the

efficacy of targeted therapy is often compromised by the emergence

of drug resistance. For instance, resistance to BRAF inhibitors,

such as PLX4720 (an analog of vemurafenib) and dabrafenib, can

reduce their efficacy (6).

Additionally, in the context of combined BRAF and MEK inhibition,

studies using the well-characterized mutant V600E BRAF model have

demonstrated that acquired resistance can develop. Specifically,

continuous treatment with the combination of PLX4720 and PD0325901

(Mirdametinib) for >77 days led to the development of acquired

resistance, evidenced by the regrowth of three

combination-resistant tumors (7).

Furthermore, several novel treatment modalities under

investigation, such as oncolytic viruses (OVs) and neoadjuvant

therapy, hold notable promise. The present study describes the case

of a young male patient with early-stage cutaneous melanoma who

developed widespread systemic metastases and acquired resistance to

targeted therapy 3 years after surgery. The present case highlights

the key need for rigorous postoperative follow-up and emphasizes

the urgency of developing strategies to potentially overcome

resistance to targeted agents in the future.

Case report

In November 2024, a 24-year-old man was admitted to

Binzhou People's Hospital (Binzhou, China), due to epigastric pain

and discomfort lasting for 10 days. In January 2021, approximately

3 years prior to this, the patient had presented with black papules

on the anterior chest that had been present for over a decade,

which were initially excised in an outpatient setting at Binzhou

People's Hospital (Binzhou, China) under the diagnosis of a dermal

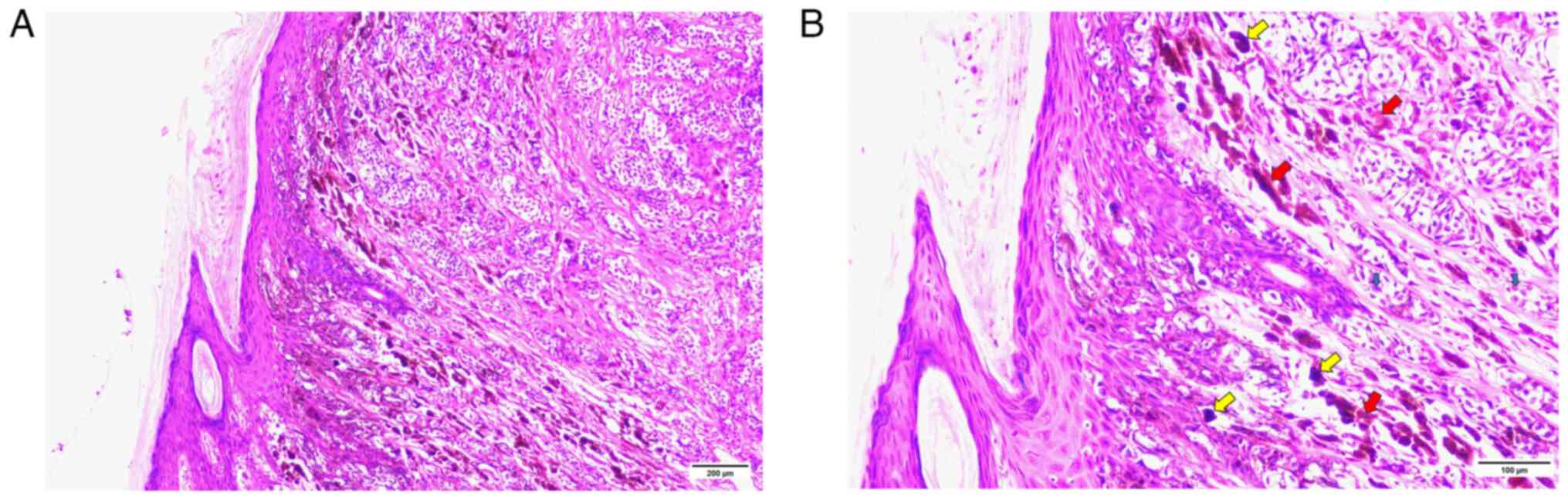

melanocytic nevus. Postoperative pathology revealed cutaneous

epithelioid malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.75 mm

and no ulceration (Fig. 1). In

January 2021, the patient underwent wide local excision of the

anterior thoracic lesion, along with sentinel lymph node biopsy of

the left supraclavicular region under general anesthesia. Pathology

from this procedure revealed acute and chronic inflammation of the

skin and subcutaneous tissues without evidence of tumor cells

(according to pathology report; data not shown). The

histopathological analysis was performed according to standard

procedures. None of the nine lymph nodes examined contained

metastatic tumor. Based on these findings and the American Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, Eighth Edition

(2017), the patient was classified as having T1aN0M0, stage IA

disease (8). No adjuvant therapy

was administered postoperatively. Follow-up imaging, including

chest (Fig. S1A and B) and

abdominal (Fig. S1C and D) CT, and

ultrasounds of the submandibular (Fig.

S2A and B), cervical supraclavicular (Fig. S2C and D), axillary (Fig. S2E and F) and inguinal (Fig. S2G and H) regions, conducted 6

months and 1 year after surgery, demonstrated no abnormalities. In

January 2022, the patient underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy for

acute appendicitis; intraoperative exploration at that time

revealed no notable visceral abnormalities.

Upon the current admission in November 2024, the

patient presented with a cachectic appearance but was otherwise

without notable comorbidities. Hematological tests were within

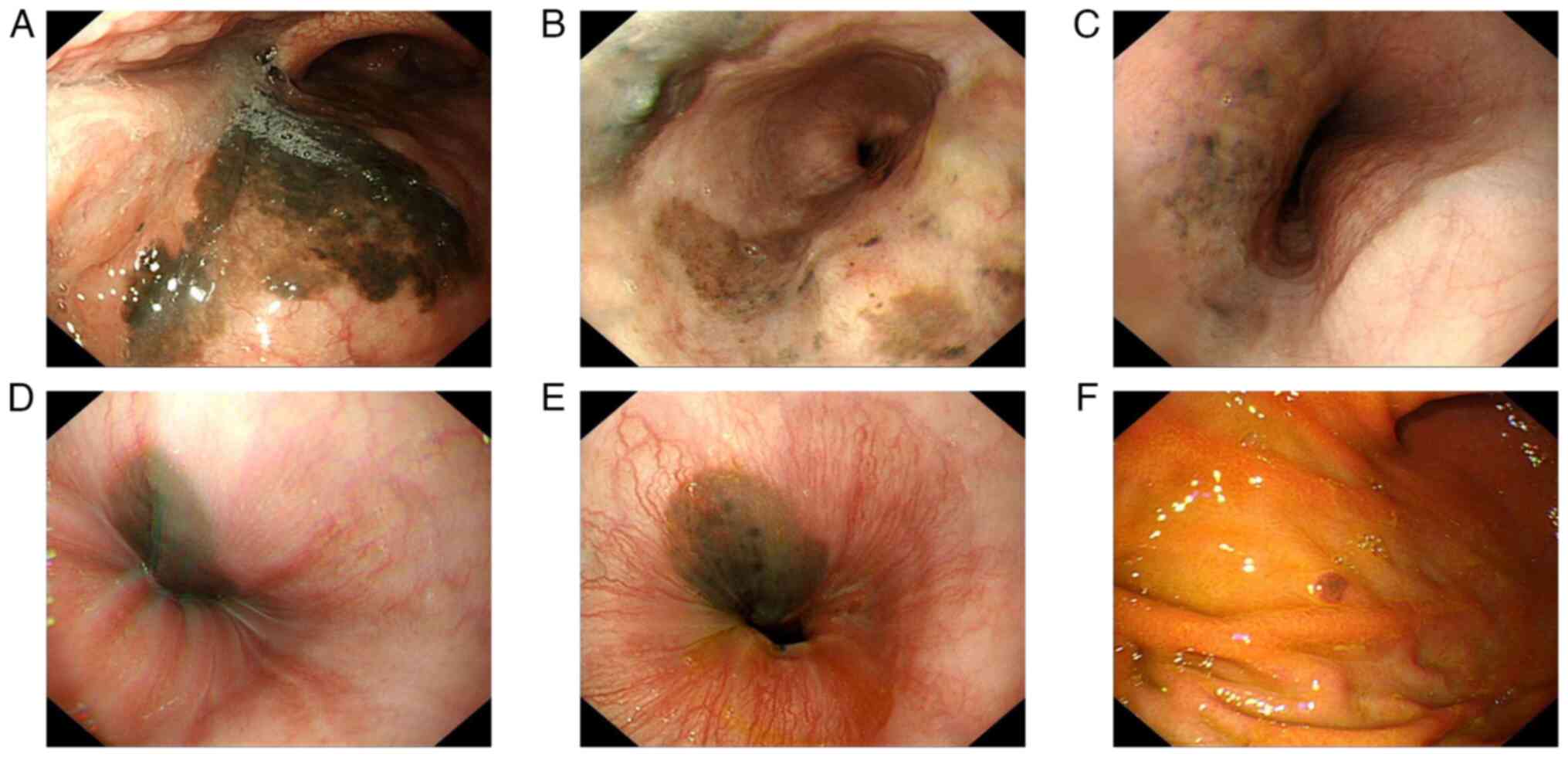

normal limits. Gastroscopy, however, revealed extensive melanosis

throughout the upper gastrointestinal tract, involving the pharynx

(Fig. 2A) and the entire esophagus

(Fig. 2B-E). This diffuse black

mucosal appearance is consistent with the endoscopic presentation

of melanoma metastasis (9,10). A pigmented protruding lesion, ~0.5

cm in diameter, in the gastric body (Fig. 2F) was biopsied and confirmed as

metastatic melanoma. These findings not only explained the

abdominal pain of the patient but also indicated advanced disease.

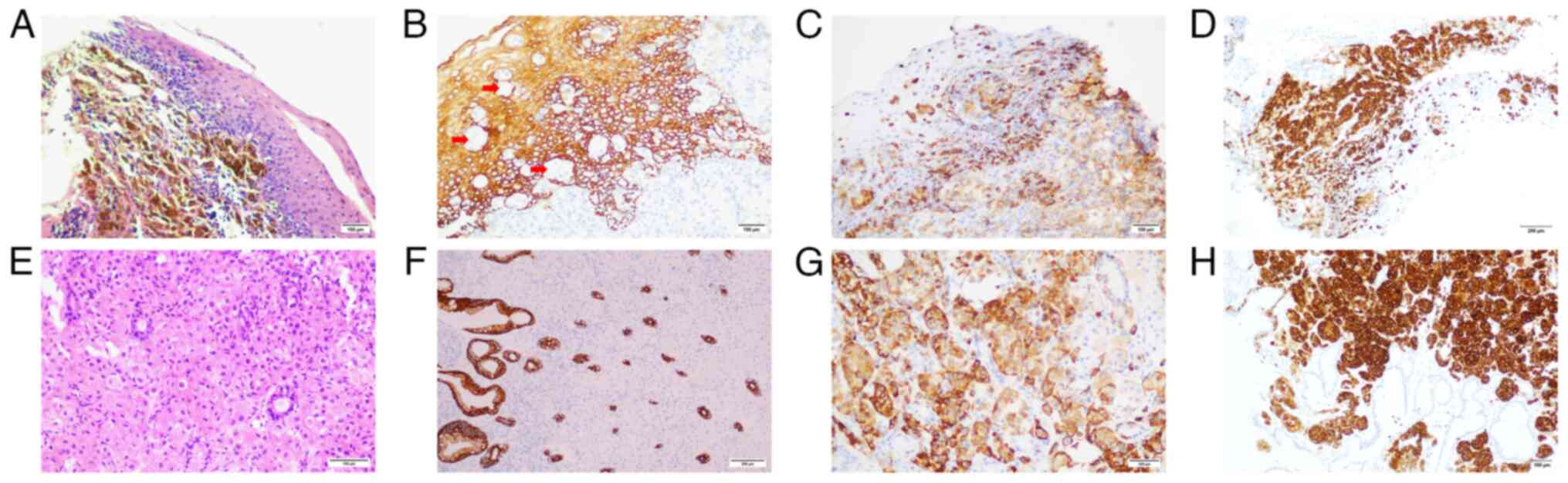

Immunohistochemistry was key in confirming the diagnosis: Lesional

cells from both esophageal (Fig.

3A-D) and gastric (Fig. 3E-H)

sites were negative for the epithelial marker pan-cytokeratin

(CKpan) (Fig. 3B and F), but

positive for the melanocytic markers human melanoma black 45

(HMB45) (Fig. 3C and G) and

melanoma antigen A (Melan-A) (Fig. 3D

and H), confirming metastatic melanoma. Tissue specimens were

fixed in 3.7% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 12

h and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut to a thickness of 4

µm. The blocking reagent used was 3% H2O2,

applied at room temperature for 10 min. The primary antibodies, all

ready-to-use, were obtained from Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology

Development Co., Ltd., and incubated at 37°C for 30 min (CKpan:

Rabbit polyclonal, cat. no. RAB-0050; HMB45: Mouse monoclonal, cat.

no. MAB-0360; Melan-A: Mouse monoclonal, cat. no. MAB-0275). The

MaxVision™ Detection Kit (HRP-conjugated, ready-to-use;

cat. no. KIT-5010) from Fuzhou Maixin was used as the secondary

reagent, with incubation at 37°C for 15 min. A BRAF mutation was

also identified, providing a molecular basis for targeted therapy.

The BRAF mutation was identified using the Human Braf Gene Mutation

Detection Kit (PCR fluorescent probe method) from DoGene Inc., with

amplification and detection performed on an ABI 7500 real-time PCR

instrument, strictly following the manufacturer's instructions.

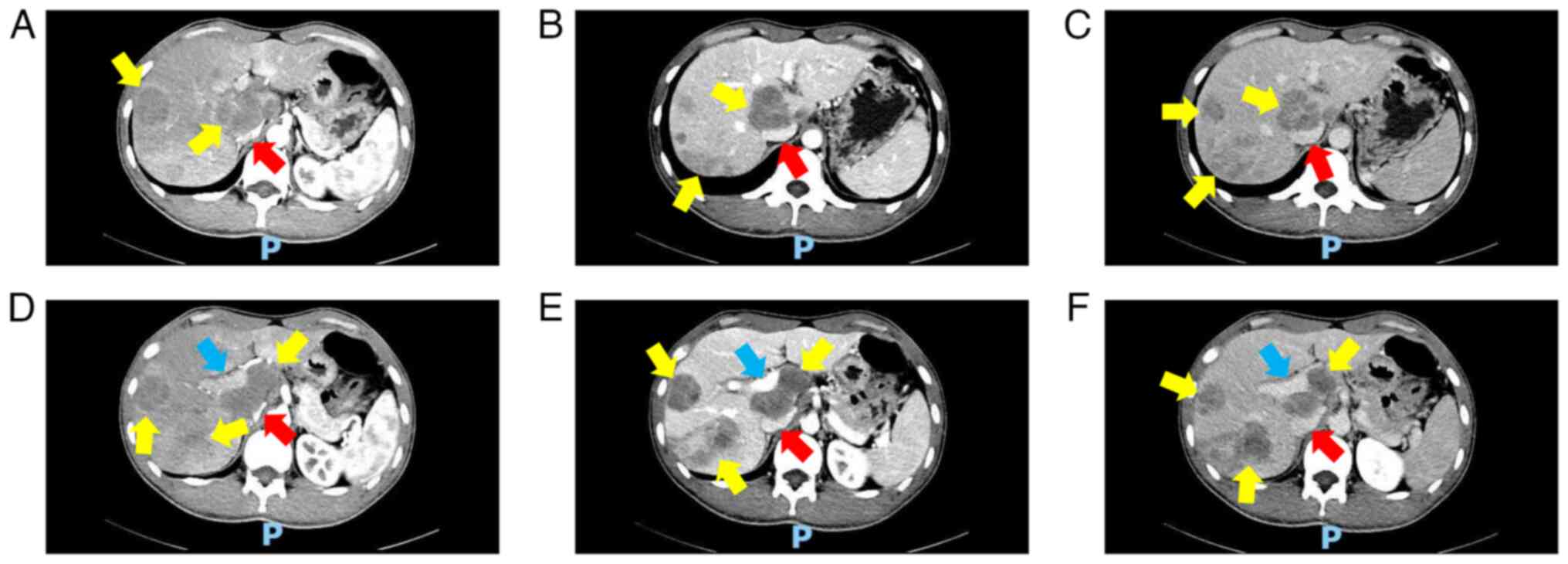

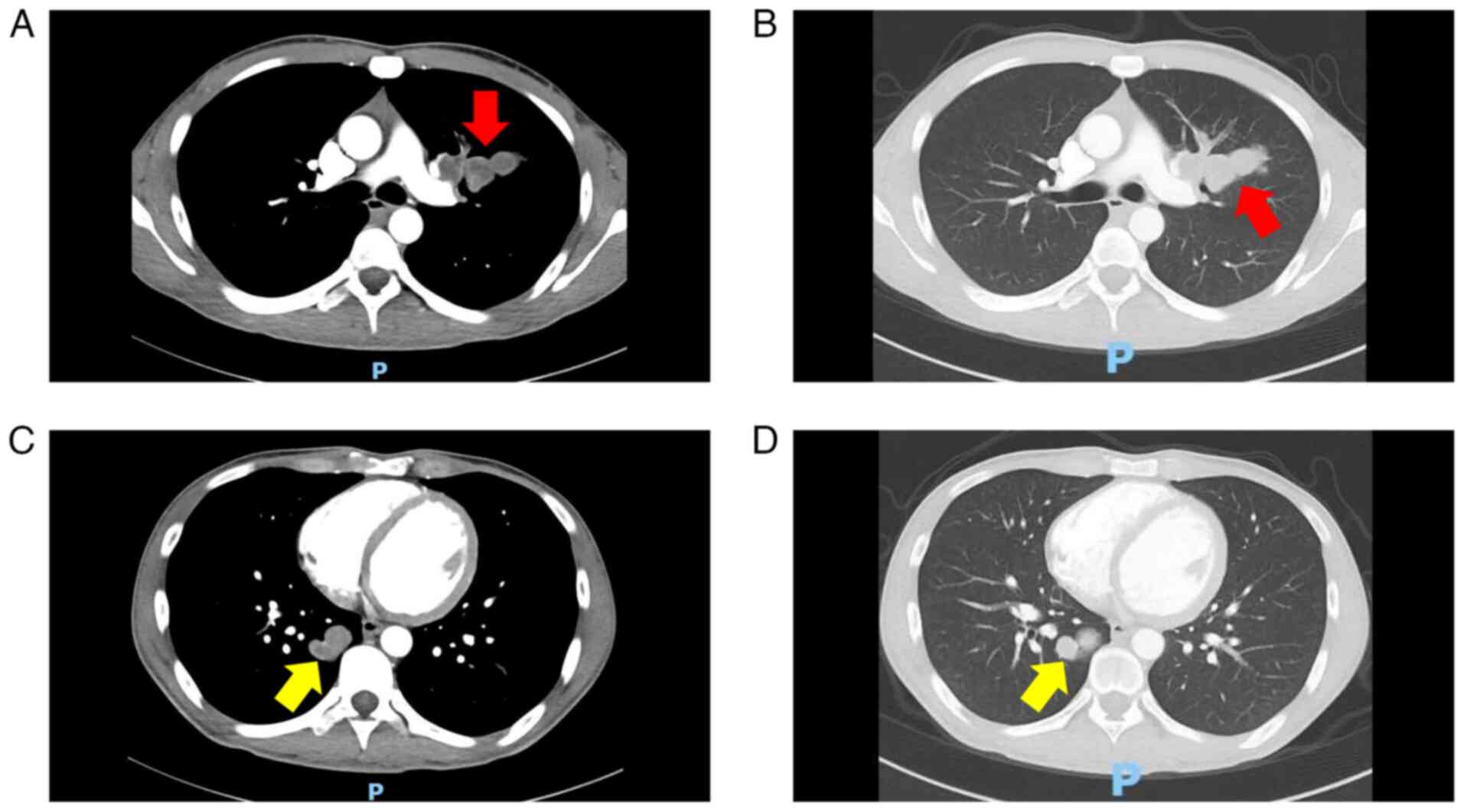

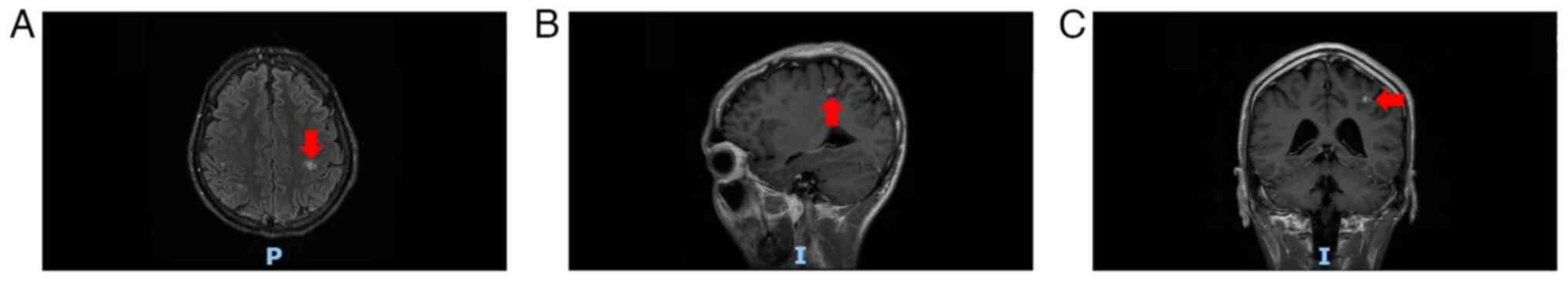

Abdominal CT (Fig. 4) exhibited

numerous metastatic lesions throughout the liver, including a large

irregular mass in the porta hepatis compressing the portal vein and

inferior vena cava. Chest CT (Fig.

5) and cranial MRI (Fig. 6)

further revealed multiple metastases in the lungs and intracranial

cavity, respectively. A final diagnosis of stage IV melanoma was

established. Due to the extensive metastatic burden, the patient

was not a candidate for surgery and the prognosis was considered to

be poor. Following a multidisciplinary team discussion in November

2024, combined targeted therapy with dabrafenib (150 mg orally

twice daily, administered as two 75-mg tablets per dose) and

trametinib (2 mg orally once daily, administered as one 2-mg

tablet) was initiated.

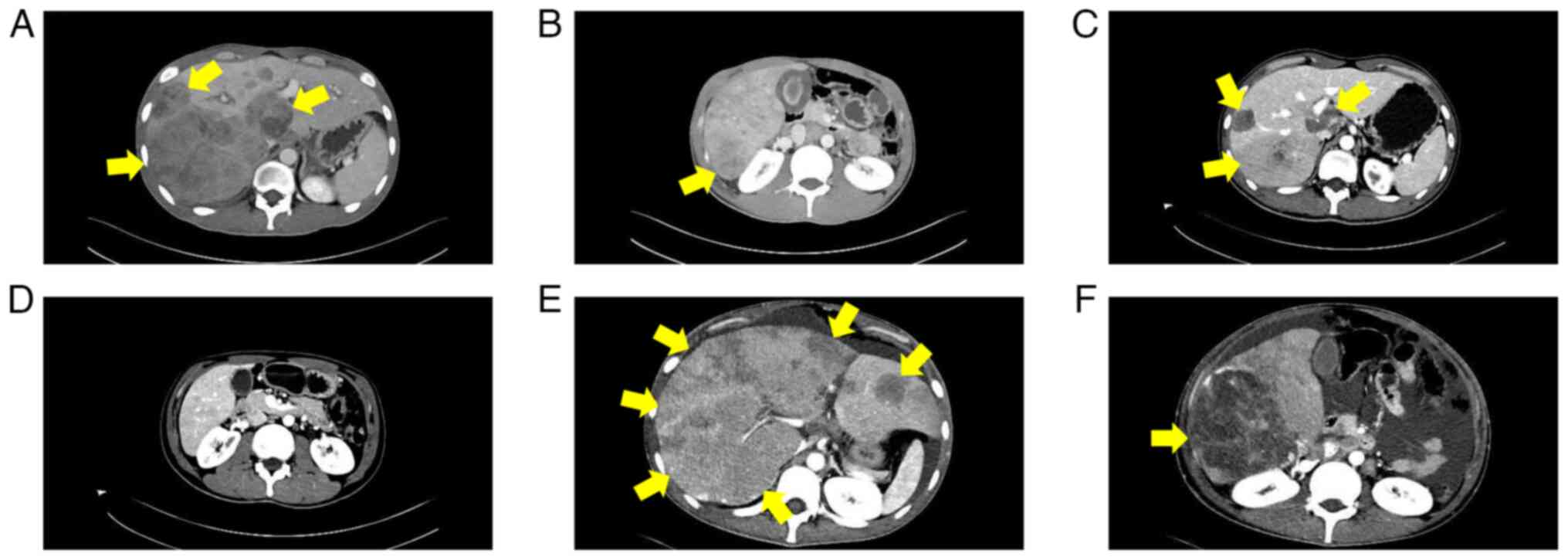

Serial abdominal CT scans documented the clinical

course, illustrating both initial treatment response and subsequent

resistance (Fig. 7). Abdominal CT

scans in January 2025 (Fig. 7B and

E) revealed marked reduction in liver metastases compared with

the first follow-up scan obtained 1 week after treatment initiation

(November 2024; Fig. 7A and D),

indicating a partial response. However, in early February 2025, the

patient suffered a rupture of a liver metastasis, which was managed

with emergency transcatheter arterial chemoembolization at Binzhou

People's Hospital. Subsequent follow-up imaging in late February

2025 (Fig. 7C and F) revealed

notable regrowth of the liver lesions, demonstrating acquired

resistance to targeted therapy. Laboratory tests from the same date

indicated acute liver failure, with elevated transaminases [alanine

transaminase, 523 U/l (reference range, 0–50 U/l); aspartate

aminotransferase, 1,541 U/l (reference range, 17–59 U/l)],

hyperbilirubinemia [total bilirubin, 115.7 µmol/l (reference range,

3–22 µmol/l)] and coagulopathy [prothrombin time, 29.9 sec

(reference range 8.8–13.8 sec)].

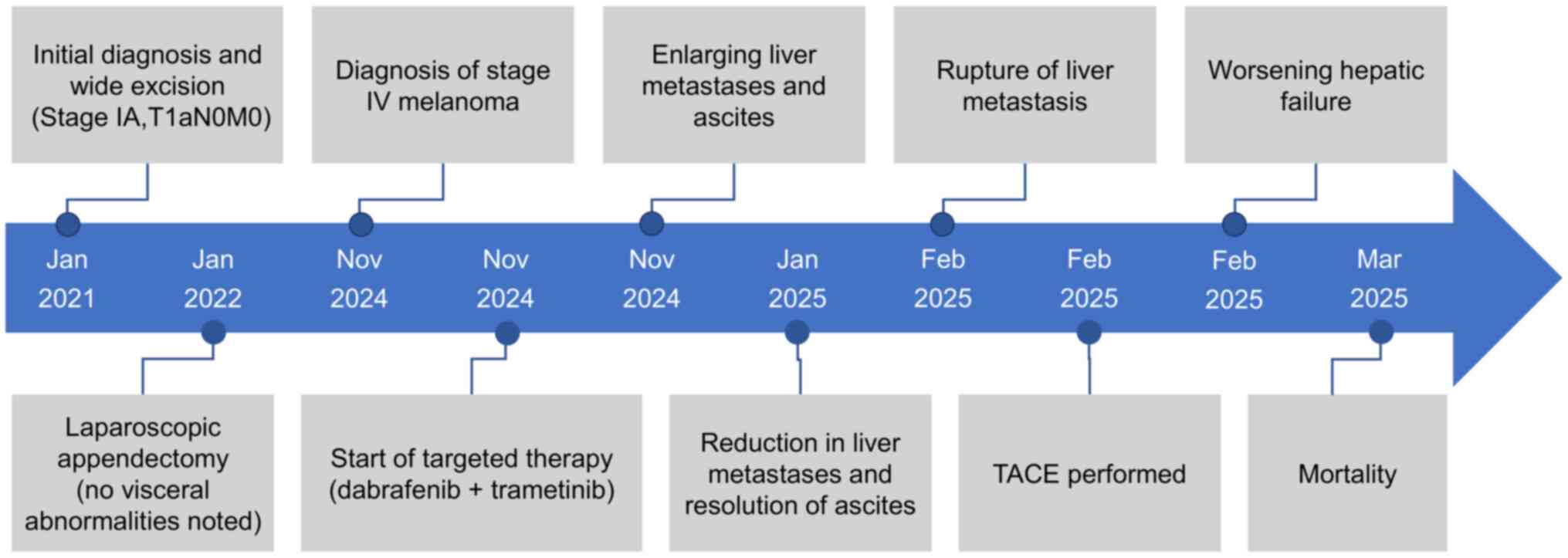

The patient succumbed to the disease in March 2025,

due to liver failure and multiple organ failure. The overall

survival from stage IV diagnosis to mortality was 4 months.

Fig. 8 provides a visual timeline

summarizing this rapid and complex clinical course, from diagnosis

and initial treatment response to disease progression and

mortality.

Discussion

Melanoma ranks among the most serious forms of skin

cancer. According to GLOBOCAN 2022 estimates, there were ~331,722

new melanoma cases globally, accounting for ~21% of all skin cancer

diagnoses (11). Despite this

comparatively lower incidence, melanoma was responsible for ~58,667

annual deaths, resulting in a case-fatality rate of ~17.7%. For

context, non-melanoma skin cancers, which comprise ~79% of all skin

cancer cases, resulted in an estimated 69,416 deaths in the same

period (12). This disparity

underscores the disproportionate lethality of melanoma relative to

its incidence. In the United States, an estimated 104,960 novel

cases of cutaneous melanoma and 8,430 associated mortalities are

projected for 2025. Between 2015 and 2021, the 5-year relative

survival rate was 94.7% (13).

Furthermore, the 5-year relative survival rate for cutaneous

melanoma across all ethnic groups in the United States has

demonstrated a consistent upward trend from 1975 to 2019 (1). Survival outcomes are strongly

influenced by the stage at diagnosis. Specifically, patients with

localized melanoma exhibit a 5-year survival rate of ~100%, whereas

those with regional lymph node involvement or distant metastases

exhibit 5-year relative survival rates of 75.7 and 34.6%,

respectively (13).

Malignant cutaneous melanoma occurs more frequently

in Caucasian populations (14). In

Europe, North America and Oceania, the trunk is the most common

site of occurrence in men (31–58%), whereas women more commonly

develop melanoma on the lower limbs and hips (26–40%). In

South-East Asia, both men (41–58%) and women (37–60%) demonstrate a

higher incidence of melanoma on the lower limbs and hips (15). Epidemiological studies report that

primary melanomas of the head, neck and trunk demonstrate a male

predominance (16,17), whereas melanomas of the lower limbs

show a female predominance (18).

Data from a study of 1,177 patients with stage I–II melanoma

identified the head and neck as a high-risk primary site. Head and

neck melanomas were overrepresented in metastatic cohorts,

accounting for 35 of 108 (32.4%) lymphatic metastases and 37 of 108

(34.3%) hematogenous metastases. Survival analysis further

confirmed this elevated risk, demonstrating a 5-year hematogenous

metastasis-free survival of 78.9%-the lowest of all sites- and a

5-year lymphatic metastasis-free survival of 84.7%, which was only

marginally higher than that for acral melanomas. Consequently, head

and neck melanomas feature high aggressiveness, frequent recurrence

and a significantly worse overall survival profile (19). Melanoma incidence is generally

higher in men, with a rate ~1.6 times higher compared with that in

women (20). Nevertheless, melanoma

remains one of the most common cancer types in young adults aged

25–29 years, particularly among young women (21,22).

In European populations, among adolescents and young adults (aged

15–39 years), the incidence is higher in women (8.99%) compared

with that in men (4.86%) (23).

According to Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results data from

2018–2022, the highest proportion of primary cutaneous melanoma

cases occurred in individuals aged 65–74 years (27.4%), followed by

those aged 55–64 years (21.5%). By contrast, only 4.4% of cases

were diagnosed in patients <34 years of age (13). Overall, the risk of developing

melanoma increases with age (22).

Melanomas have a pronounced tendency to metastasize

to distant sites, with trunk melanomas exhibiting a particularly

high risk of distant spread. The most common first site of distant

metastasis is the skin (38%), followed by the lungs (36%), liver

(20%) and brain (20%) (24). Median

survival time varies according to the number of metastatic sites,

with 7 months recorded for patients with one distant metastasis

site, 4 months for those with two sites and only 2 months for those

with three or more sites (24).

However, the clinical features of the present case

are markedly divergent from the aforementioned epidemiological

statistics, highlighting its distinctive value as a cautionary

case. While epidemiological data indicate that primary cutaneous

melanoma most frequently occurs in the age group of 65–74 years

(13), the present patient was 21

years old at initial diagnosis, representing a considerably younger

demographic for this disease. More notably, the primary lesion was

located on the chest, with a Breslow thickness of only 0.75 mm,

absence of ulceration, no evidence of metastasis and pathological

characteristics generally associated with a favorable prognosis.

According to the AJCC 8th edition staging system, the patient was

classified as stage IA (T1aN0M0) (8). Based on current epidemiological

statistics, such patients would be expected to have a 5-year

survival rate of 100% (12).

However, the patient in the present case developed widespread

systemic metastases within 3 years of surgery, with merely 4 years

elapsing from the initial stage IA diagnosis to mortality from

stage IV disease. This rapid and fatal progression in a patient

with initially favorable pathological staging revealed the

limitations of relying solely on conventional pathological staging

for prognosis prediction. Therefore, for young patients with

melanoma, even those with lesions suggesting a favorable prognosis,

enhanced post-operative health education and improved follow-up

compliance should be implemented in the future. Furthermore,

individualized surveillance strategies should be considered,

potentially including shortened follow-up intervals or increased

imaging frequency, to achieve early detection and timely

intervention of tumor recurrence.

Risk factors for cutaneous melanoma are broadly

classified as exogenous or endogenous. Exogenous factors include

solar and artificial ultraviolet (UV) radiation, specific lifestyle

habits and immunosuppression. Endogenous factors comprise skin

color, hair color, eye color, the number of melanocytic nevi, the

presence of atypical nevi, sex, medical history, hereditary factors

and genetic susceptibility (25–27).

Among these, UV radiation represents the most notable environmental

risk factor for all types of skin cancer (28). The number of common and atypical

nevi is also a key independent predictor of melanoma risk. A

previous study indicated that patients with a high number of nevi

(n=101-120) have a risk ~7 times greater compared with those with

few nevi (n=0-15) (4).

Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for

early-stage melanoma. However, high-risk patients treated with

surgery alone have only a 40–60% probability of remaining

disease-free at 5 years and numerous patients may eventually

experience locoregional or distant recurrence (29). According to the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, preferred adjuvant

therapy options for patients with stage IIB-IV cutaneous melanoma

include anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4)

agents and anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), or for

patients with BRAF mutations, targeted therapy. In addition,

several emerging immunotherapies and neoadjuvant regimens are

becoming viable options for patients with melanoma. Systemic

therapies, particularly ICIs (such as ipilimumab, pembrolizumab,

atezolizumab and relatlimab) and BRAF-targeted treatments (such as

dabrafenib and trametinib), have markedly improved the prognosis of

patients with metastatic (stage III and IV) cutaneous melanoma and

have also demonstrated notable benefit in early-stage (IIB/C)

primary melanoma (30). Although

melanoma incidence continues to rise, mortality has been declining

by an average of ~4% annually since 2015. This trend reflects major

advances in the treatment of advanced and metastatic disease,

largely attributable to progress in immunotherapy and targeted

agents (31).

ICIs comprise CTLA-4 inhibitors (such as

ipilimumab), PD-1 inhibitors (such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab),

programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors (such as

atezolizumab) and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) inhibitors

(such as relatlimab). CTLA-4 and PD-1 inhibitors enhance the

ability of T cells to eliminate cancer cells by blocking CTLA-4

immune checkpoint molecules and PD-1/PD-L1 interactions,

respectively (32). By contrast,

LAG-3 inhibitors bind to the LAG-3 receptor and disrupt its

interaction with ligands, thereby alleviating LAG-3

pathway-mediated immunosuppression and promoting T-cell

proliferation. Checkpoint immunotherapy is indicated for patients

with both BRAF mutant-type and wild-type melanoma (33). A previous study reported that 15.5%

of patients with unresectable stage IV melanoma achieved a complete

response after first-line ICI treatment, with 5-year

progression-free survival and overall survival rates of 79 and 83%,

respectively, among those achieving a complete response (34).

Ipilimumab, the first ICI approved for advanced

melanoma, demonstrated a significant survival benefit in stage IV

disease by increasing the median overall survival to 10.1 months,

compared to 6.4 months with the glycoprotein 100 (gp100) peptide

vaccine alone (35). Due to the

high immunogenicity of melanoma, anti-PD-1 inhibitors are

particularly effective in this malignancy (36). Although randomized clinical trials

[CheckMate 238 with nivolumab (37,38);

KEYNOTE-054 (39)/716 (40,41)

with pembrolizumab] have demonstrated that adjuvant PD-1 inhibitors

improve recurrence-free survival in patients with resectable stage

IIB-IV melanoma, an overall survival benefit has not been observed

to date (42). Ongoing first-line

clinical trials are evaluating PD-1 inhibitors in combination with

multiple classes of agents, including histone deacetylase

inhibitors (HDAC6i Nexturastat A) (43), novel immunotherapies (NT-I7)

(44), vaccines (IDO/PD-L1

targeting peptide vaccine) (45)

and toll-like receptor 9 agonist (Nelitolimod) (46). For patients with metastatic melanoma

harboring BRAF V600E/K mutations, the combination of ipilimumab and

nivolumab is considered a preferred first-line treatment regardless

of mutation status, establishing ICI as a primary therapeutic

option (5). In a previous study by

Hodi et al (47), 945

patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma received either

ipilimumab plus nivolumab, nivolumab monotherapy or ipilimumab

alone. The 4-year overall survival rate was 53% in the combination

group, compared with 46% in the nivolumab group and 30% in the

ipilimumab group. Among patients with mutant-type BRAF, the 4-year

overall survival rates were 62, 50 and 33% for the combination,

nivolumab and ipilimumab groups, respectively; corresponding rates

for patients with wild-type BRAF were 49, 45 and 28%. These results

suggested that combination therapy may offer enhanced benefit

compared with nivolumab monotherapy, particularly in patients with

BRAF-mutations.

LAG-3 inhibitors represent the first class of LAG-3

protein inhibitors worldwide. On March 18, 2022, the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) approved the fixed-dose combination of

relatlimab and nivolumab for the treatment of adult and pediatric

patients aged ≥12 years with unresectable or metastatic melanoma.

This combination acts through simultaneous inhibition of LAG-3 and

PD-1, and has demonstrated efficacy in previously untreated

metastatic or unresectable melanoma (48). For most patients with metastatic

melanoma, anti-PD-1-based therapy combined with either ipilimumab

or relatlimab offers the potential for long-term survival and

possibly a cure (49).

Targeted therapies are designed to specifically

address molecular abnormalities or target key pathways essential

for melanoma cell proliferation and survival (32). BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib,

dabrafenib and encorafenib) and MEK inhibitors (trametinib and

cobimetinib) represent the main classes of agents used in this

approach. The BRAF serine/threonine kinase, an isoform of the Raf

family, functions within the MAPK pathway, which serves a key role

in regulating cell proliferation (50). BRAF mutations occur most frequently

in malignant melanoma (51), with

the V600E variant accounting for >80% of all BRAF mutations

(50). It has been reported that

~50% of patients with metastatic melanoma harbor a BRAF V600

mutation. MEK also serves a key function within the MAPK cascade.

In patients with metastatic melanoma (stage IV or unresectable

stage III), dabrafenib monotherapy resulted in a median

progression-free survival (PFS) time of 5.1 months (52). A previous study by Long et al

(53) reported that combination

therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib in treatment-naive patients

with BRAF V600 mutation-positive metastatic melanoma yielded a

median overall survival time of >2 years, with ~20% of patients

remaining progression-free at 3 years. These findings indicated

that the combination was associated with prolonged survival and

durable responses in a subset of individuals. In addition, compared

with vemurafenib monotherapy, dabrafenib combined with trametinib

significantly improved overall survival in previously untreated

patients with BRAF V600E or V600K metastatic melanoma, without

increasing overall toxicity (54).

Due to its generally acceptable safety profile, adjuvant dabrafenib

plus trametinib is now considered a reasonable option for patients

with advanced resectable BRAF-mutated melanoma (55). Overall, concurrent BRAF and MEK

inhibition has been reported to yield notably improved clinical

outcomes compared with BRAF inhibitor monotherapy.

In 2022, Corrie et al (56) demonstrated that combination

therapies outperform monotherapy in BRAF-mutated unresectable or

metastatic melanoma. Among these, the

atezolizumab/vemurafenib/cobimetinib triple therapy and the

encorafenib/binimetinib combination exhibited the most favorable

efficacy profiles. Furthermore, encorafenib/binimetinib

demonstrated an enhanced safety profile compared with all other

combination regimens, including triple therapy. In 2023, results

from a phase III trial reported by Haist et al (57) indicated that triple combination

therapy, comprising an ICI, a BRAF inhibitor and a MEK inhibitor,

prolonged response duration and enabled long-term PFS. However,

most of these trials did not meet their primary endpoints and

therefore do not support the routine first-line use of triple

therapy in patients with BRAF V600-mutant melanoma. That said,

subgroup analyses and preliminary data in patients with melanoma

brain metastases suggested that patients with higher disease burden

or rapidly progressing disease may derive greater benefit from such

regimens. The addition of atezolizumab to the targeted therapy

combination of vemurafenib and cobimetinib was reported to be safe

and tolerable, and significantly improved PFS in patients with

advanced melanoma harboring BRAF V600 mutations (58). For most patients with BRAF

V600-mutant metastatic melanoma, the preferred treatment sequence

involves initial therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, followed

by BRAF and MEK inhibitors if required (59).

Beyond the established approaches of ICI and

targeted therapy, the potential benefits of several emerging

immunotherapies and neoadjuvant treatments for patients with

melanoma warrant further research in the future.

OVs represent one of the most novel and promising

forms of intratumoral immunotherapy. The first OV approved for

melanoma treatment was talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), a modified

herpes simplex virus type 1, indicated for recurrent melanoma after

initial surgery (60). Previous

studies indicated that T-VEC combined with ipilimumab had a

manageable safety profile and appeared to yield notably increased

efficacy compared with either agent alone (61). For patients with regional or distant

metastatic melanoma, including those with visceral involvement,

T-VEC in combination with ICIs may represent a promising novel

therapeutic alternative (61).

Neoadjuvant therapy refers to induction treatment

administered to reduce tumor burden before primary treatment,

typically surgery (62). This

approach includes both neoadjuvant immunotherapy and neoadjuvant

targeted therapy; it serves a particularly key role in locally

advanced, resectable stage III–IV or borderline resectable

melanoma. In such settings, neoadjuvant therapy may facilitate

early eradication of micrometastases within a more immunologically

responsive microenvironment, potentially offering enhanced curative

potential compared with adjuvant therapy, while also reducing the

need for extensive surgery, achieving microscopic R0 resection,

decreasing the risk of distant metastasis and providing key

biomarker information to potentially guide subsequent adjuvant

treatment in the future (29).

Patel et al (63) reported

that, in patients with high-risk, resectable stage III–IV melanoma,

the 2-year event-free survival rate in the neoadjuvant-adjuvant

group was ~23% higher compared with that in the adjuvant-only

group. Patients receiving pembrolizumab both before and after

surgery exhibited significantly longer event-free survival times

compared with those receiving adjuvant pembrolizumab alone. Amaria

et al (64) demonstrated

that neoadjuvant treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib in

patients with resectable stage IIIB-IV BRAF-mutant cutaneous

melanoma significantly improved progression-free survival rate at a

median follow-up time of 18.6 months. However, neoadjuvant therapy

carries the risk of disease progression during treatment, which may

render initially resectable tumors unresectable or lead to distant

spread (65).

According to the NCCN guidelines, first-line

systemic therapy for advanced BRAF-mutant melanoma includes either

combined immunotherapy or combined targeted therapy (66). However, the choice of optimal

first-line treatment remains a subject of debate. BRAF/MEK

inhibitors typically induce a strong and rapid initial response,

yet disease progression remains almost inevitable. By contrast,

ICIs may exhibit a lower initial response rate, possibly due to the

time required for immune activation, but can provide more durable

long-term clinical benefits (67,68).

For patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma with active brain

metastases, several BRAF/MEK inhibitors have demonstrated notable

activity with manageable safety profiles and can lead to marked

tumor regression (69–71). By contrast, ipilimumab tends to be

more effective when brain metastases are small and asymptomatic

(72). Furthermore, a previous

study indicated that, although dabrafenib plus trametinib resulted

in PFS and overall response rates similar to those of nivolumab

plus ipilimumab, dabrafenib plus trametinib was associated with

significantly shorter treatment duration and lower healthcare costs

(73). In the present case, the

poor performance status of the patient and rapid progressive

disease necessitated swift disease control to minimize early risks.

After multidisciplinary discussion and detailed communication with

the patient and family, combined targeted therapy was selected as

the first-line regimen, based on its faster onset of action and

higher rates of tumor regression. The present case underscores that

the optimal first-line strategy for advanced melanoma should be

individualized based on a comprehensive evaluation of multiple

clinical and patient-specific factors.

Although BRAF/MEK inhibitors demonstrate high

efficacy in BRAF-mutant melanoma, their clinical benefits are

frequently constrained by intrinsic, adaptive and acquired

resistance mechanisms. Intrinsic resistance may result from

loss-of-function mutations in PTEN (74,75)

and neurofibromatosis type 1 (76,77),

leading to activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. Adaptive

resistance often involves upregulation of receptor tyrosine kinases

(78), which can reactivate ERK

signaling and thereby drive treatment resistance. The most

prevalent form, acquired resistance, primarily involves MAPK

pathway reactivation through various molecular alterations,

including MEK mutations (79), BRAF

alternative splicing (80) and BRAF

amplification (81). These

mechanisms collectively contribute to the development of treatment

resistance and diminished therapeutic efficacy. To address these

challenges, various combination regimens involving inhibitors have

been developed. Among these, the combination of BRAF and MEK

inhibitors has been reported to yield notably increased overall

survival compared with BRAF inhibitor monotherapy (54). Based on this evidence, the

dabrafenib plus trametinib combination received FDA approval for

patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma harboring BRAF

V600E/K mutations. In the present case, the observed pattern of

initial tumor regression followed by rapid progression strongly

suggests the emergence of acquired resistance, possibly driven by

one or more of the aforementioned molecular events. Thus, the

present case highlights the current limitations of combination

targeted therapy and supports the need for future research into

strategies that can potentially overcome or reverse resistance.

Melanoma exhibits a notable tendency for distant

metastasis. Standardized postoperative follow-up is essential for

patients with early-stage disease who have undergone surgical

resection. According to NCCN guidelines, patients with stage IA

melanoma should undergo history and physical examination (H&P)

(with emphasis on nodes and skin) every 6–12 months for the first 5

years after surgery, while routine laboratory tests and imaging

studies are not recommended (66).

However, in the present case, suboptimal adherence to scheduled

follow-up visits was noted. Furthermore, clinical experience

indicates that disease progression can be markedly rapid in certain

young patients following recurrence. Therefore, we propose a dual

approach: i) Establishing a structured patient education and

follow-up system to ensure consistent implementation of

guideline-recommended evaluations through regular reminders; and

ii) formulating personalized, risk-adapted surveillance strategies

for young patients with high-risk features. This strategy aims to

avoid excessive medical intervention while enabling early detection

and timely management of recurrent disease.

Dacarbazine served as the key metastatic melanoma

treatment for decades; however, its use has declined with the

emergence of more effective options such as targeted therapy and

immunotherapy (32). Current

systemic treatments for advanced melanoma primarily include ICIs

and targeted therapies. Anti-PD-1 therapy is now a standard option

for resected stage IIB-IV disease, while BRAF-targeted therapy is

the standard for resected stage III–IV melanoma. Both modalities

have been associated with a 35–50% relative improvement in

recurrence-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival

rates, although neither has demonstrated a notable overall survival

benefit (82). Although combination

therapies generally outperform monotherapies, the optimal

combination strategy for maximizing patient benefit requires

further investigation. In addition, emerging treatments such as OVs

and neoadjuvant regimens demonstrate notable promise and may

represent future advances in the management of advanced

melanoma.

In conclusion, the present report describes the case

of a 24-year-old male patient with early-stage cutaneous melanoma

who developed multiple systemic metastases 3 years after radical

resection and who succumbed 4 months after the diagnosis of

metastatic disease. The present case underscores the importance of

establishing a strict post-operative education and follow-up system

for patients with early-stage melanoma, and developing a

personalized risk-monitoring strategy. Treatment selection for

advanced melanoma should not be restricted to ICIs or targeted

therapy alone; however, a judicious integration of multiple

modalities may yield improved outcomes. Novel approaches such as

oncolytic virotherapy and neoadjuvant strategies also represent

promising treatment options in the future. The field of advanced

melanoma treatment continues to present numerous opportunities,

innovations and challenges. Novel optimized treatment strategies

may become available that potentially prolong patient survival in

the future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DX and PW conceptualized and designed the present

case report and provided overall supervision of the research. XH

performed a comprehensive literature search, conducted analysis and

interpretation of the clinical course, and drafted the initial

manuscript. LZ and DX collected and assembled all clinical data,

including imaging studies and laboratory results, and confirm the

authenticity of all raw data. LZ prepared the figures. DX

critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present case report was approved by the Binzhou

People's Hospital Clinical Trial Ethics Committee (Binzhou, China;

approval no. YXKYLL-20251101). Written informed consent was

obtained from the patient. The present case report complied with

the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Written consent for the publication of data and any

related images was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC), . WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. Elder DE,

Massi D, Scolyer RA and Willemze R: 11. 4th Edition. IARC; Lyon:

2018

|

|

3

|

Elder DE, Bastian BC, Cree IA, Massi D and

Scolyer RA: The 2018 World Health Organization classification of

cutaneous, mucosal, and uveal melanoma: Detailed analysis of 9

distinct subtypes defined by their evolutionary pathway. Arch

Pathol Lab Med. 144:500–522. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini

P, Abeni D, Boyle P and Melchi CF: Meta-analysis of risk factors

for cutaneous melanoma: I. Common and atypical naevi. Eur J Cancer.

41:28–44. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Switzer B, Piperno-Neumann S, Lyon J,

Buchbinder E and Puzanov I: Evolving management of stage IV

melanoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 43:e3974782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang T, Xiao M, Ge Y, Krepler C, Belser E,

Lopez-Coral A, Xu X, Zhang G, Azuma R, Liu Q, et al: BRAF

inhibition stimulates melanoma-associated macrophages to drive

tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res. 21:1652–1664. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sanchez IM, Purwin TJ, Chervoneva I, Erkes

DA, Nguyen MQ, Davies MA, Nathanson KL, Kemper K, Peeper DS and

Aplin AE: In vivo ERK1/2 reporter predictively models response and

resistance to combined BRAF and MEK inhibitors in melanoma. Mol

Cancer Ther. 18:1637–1648. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

American Joint Committee on Cancer, . AJCC

Cancer Staging Manual. 6th Edition. Springer New York; NY: 2002

|

|

9

|

Taal BG, Westerman H, Boot H and Rankin

EM: Clinical and endoscopic features of melanoma metastases in the

upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 50:261–263. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu H, Yan Y and Jiang CM: Primary

malignant melanoma of the esophagus with unusual endoscopic

findings: A case report and literature review. Medicine

(Baltimore). 95:e34792016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer and Global Cancer Observatory, Cancer Today Globocan 2022, .

Melanoma of Skin. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/16-melanoma-of-skin-fact-sheet.pdfApril

29–2025

|

|

12

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer, Global Cancer Observatory and Cancer Today Globocan 2022, .

Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/17-non-melanoma-skin-cancer-fact-sheet.pdfApril

29–2025

|

|

13

|

National Cancer Institute Surveillance and

Epidemiology, End Results Program, . Cancer Stat Facts: Melanoma of

the Skin. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.htmlMay

7–2025

|

|

14

|

Karimkhani C, Dellavalle RP, Coffeng LE,

Flohr C, Hay RJ, Langan SM, Nsoesie EO, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE,

Silverberg JI, et al: Global skin disease morbidity and mortality:

An update from the global burden of disease study 2013. JAMA

Dermatol. 153:406–412. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Di Carlo V, Eberle A, Stiller C, Bennett

D, Katalinic A, Marcos-Gragera R, Girardi F, Larønningen S, Schultz

A, Lima CA, et al: Sex differences in survival from melanoma of the

skin: The role of age, anatomic location and stage at diagnosis: A

CONCORD-3 study in 59 countries. Eur J Cancer. 217:1152132025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jayasinghe D, Nufer KL, Betz-Stablein B,

Soyer HP and Janda M: Body site distribution of acquired

melanocytic naevi and associated characteristics in the general

population of caucasian adults: A scoping review. Dermatol Ther

(Heidelb). 12:2453–2488. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lallas K, Kyrgidis A, Chrysostomidis A,

Vakirlis E, Apalla Z and Lallas A: Clinical, dermatoscopic,

histological and molecular predictive factors of distant melanoma

metastasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 202:1044582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Olsen CM, Thompson JF, Pandeya N and

Whiteman DC: Evaluation of sex-specific incidence of melanoma. JAMA

Dermatol. 156:553–560. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Calomarde-Rees L, García-Calatayud R,

Requena Caballero C, Manrique-Silva E, Traves V, García-Casado Z,

Soriano V, Kumar R and Nagore E: Risk factors for lymphatic and

hematogenous dissemination in patients with stages I to II

cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 155:679–687. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Waseh S and Lee JB: Advances in melanoma:

Epidemiology, diagnosis, and prognosis. Front Med (Lausanne).

10:12684792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, .

Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. National Cancer Institute (US);

Bethesda, MD, USA: 2025

|

|

22

|

American Cancer Society, . Key Statistics

for Melanoma Skin Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.htmlMay

7–2025

|

|

23

|

Indini A, Didoné F, Massi D, Puig S,

Casadevall JR, Bennett D, Katalinic A, Sanvisens A, Ferrari A,

Lasalvia P, et al: Incidence and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma in

European adolescents and young adults (AYAs): EUROCARE-6

retrospective cohort results. Eur J Cancer 1990.

213:1150792024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Balch CM, Soong SJ, Murad TM, Smith JW,

Maddox WA and Durant JR: A multifactorial analysis of melanoma. IV.

Prognostic factors in 200 melanoma patients with distant metastases

(stage III). J Clin Oncol. 1:126–134. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gordon R: Skin cancer: An overview of

epidemiology and risk factors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 29:160–169. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wunderlich K, Suppa M, Gandini S, Lipski

J, White JM and Del Marmol V: Risk factors and innovations in risk

assessment for melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell

carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 16:10162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Conforti C and Zalaudek I: Epidemiology

and risk factors of melanoma: A review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 11

(Suppl 1):e2021161S2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Raimondi S, Suppa M and Gandini S:

Melanoma Epidemiology and Sun Exposure. Acta Derm Venereol.

100:57462020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rutkowski P and Mandala M: Perioperative

therapy of melanoma: Adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment. Eur J Surg

Oncol. 50:1079692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Maher NG, Vergara IA, Long GV and Scolyer

RA: Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in melanoma. Pathology.

56:259–273. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ernst M and Giubellino A: The current

state of treatment and future directions in cutaneous malignant

melanoma. Biomedicines. 10:8222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Russano F, Rastrelli M, Dall'Olmo L, Del

Fiore P, Gianesini C, Vecchiato A, Mazza M, Tropea S and Mocellin

S: Therapeutic treatment options for in-transit metastases from

melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 16:30652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM,

Gershenwald JE and Scolyer RA: Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet.

402:485–502. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chatziioannou E, Leiter U, Thomas I, Keim

U, Seeber O, Meiwes A, Boessenecker I, Gonzalez SS, Torres FM,

Niessner H, et al: Features and long-term outcomes of stage IV

melanoma patients achieving complete response under anti-PD-1-based

immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 24:453–467. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW,

Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel

JC, et al: Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with

metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 363:711–723. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Brandlmaier M, Hoellwerth M, Koelblinger

P, Lang R and Harrer A: Adjuvant PD-1 checkpoint inhibition in

early cutaneous melanoma: Immunological mode of action and the role

of ultraviolet radiation. Cancers (Basel). 16:14612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ascierto PA, Del Vecchio M, Mandalá M,

Gogas H, Arance AM, Dalle S, Cowey CL, Schenker M, Grob JJ,

Chiarion-Sileni V, et al: Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in

resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma (CheckMate 238): 4-Year

results from a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21:1465–1477. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Larkin J, Del Vecchio M, Mandalá M, Gogas

H, Arance Fernandez AM, Dalle S, Cowey CL, Schenker M, Grob JJ,

Chiarion-Sileni V, et al: Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in

resected stage III/IV melanoma: 5-year efficacy and biomarker

results from CheckMate 238. Clin Cancer Res. 29:3352–3361. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bührer E, Kicinski M, Mandala M, Pe M,

Long GV, Atkinson V, Blank CU, Haydon A, Dalle S, Khattak A, et al:

Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III

melanoma (EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054): Long-term, health-related

quality-of-life results from a double-blind, randomised,

controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 25:1202–1212. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Long GV, Luke JJ, Khattak MA, de la Cruz

Merino L, Del Vecchio M, Rutkowski P, Spagnolo F, Mackiewicz J,

Chiarion-Sileni V, Kirkwood JM, et al: Pembrolizumab versus placebo

as adjuvant therapy in resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma

(KEYNOTE-716): Distant metastasis-free survival results of a

multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

23:1378–1388. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Luke JJ, Rutkowski P, Queirolo P, Del

Vecchio M, Mackiewicz J, Chiarion-Sileni V, de la Cruz Merino L,

Khattak MA, Schadendorf D, Long GV, et al: Pembrolizumab versus

placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC

melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 399:1718–1729. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ochenduszko S, Puskulluoglu M,

Pacholczak-Madej R and Ruiz-Millo O: Adjuvant anti-PD1

immunotherapy of resected skin melanoma: An example of

non-personalized medicine with no overall survival benefit. Crit

Rev Oncol Hematol. 202:1044432024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Knox T, Sahakian E, Banik D, Hadley M,

Palmer E, Noonepalle S, Kim J, Powers J, Gracia-Hernandez M,

Oliveira V, et al: Selective HDAC6 inhibitors improve anti-PD-1

immune checkpoint blockade therapy by decreasing the

anti-inflammatory phenotype of macrophages and down-regulation of

immunosuppressive proteins in tumor cells. Sci Rep. 9:61362019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Phoon YP, Wolfarth AA, Funchain P, Ko JS,

Choi D, Dedkova E, Bateman DD, Corvin J, Melenhorst JJ and Gastman

BR: NT-I7, a novel long-acting interleukin-7, promotes anti-PD-1

efficacy in an autologous humanized melanoma model. Sci Rep.

15:379502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lorentzen CL, Kjeldsen JW, Ehrnrooth E,

Andersen MH and Marie Svane I: Long-term follow-up of anti-PD-1

naïve patients with metastatic melanoma treated with IDO/PD-L1

targeting peptide vaccine and nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer.

11:e0067552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ribas A, Milhem MM, Hoimes CJ, Amin A, Lao

CD, Conry RM, Hunt JP, Daniels GA, Almubarak M, Shaheen M, et al:

Phase 2, open-label, multicenter study of nelitolimod in

combination with pembrolizumab in anti-PD-1 treatment-Naïve

advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 31:4070–4078. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hodi FS, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R,

Grob JJ, Rutkowski P, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Wagstaff J,

Dummer R, et al: Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone

versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067):

4-Year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 19:1480–1492. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Mullick N and Nambudiri VE:

Relatlimab-nivolumab: A practical overview for dermatologists. J Am

Acad Dermatol. 89:1031–1037. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Chan PY and Corrie PG: Curing stage IV

melanoma: Where Have we been and where are we? Am Soc Clin Oncol

Educ Book. 44:e4386542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Smalley KSM: Understanding melanoma

signaling networks as the basis for molecular targeted therapy. J

Invest Dermatol. 130:28–37. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Garnett MJ and Marais R: Guilty as

charged: B-RAF is a human oncogene. Cancer Cell. 6:313–319. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary

T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, Rutkowski P, Blank CU, Miller WH Jr,

Kaempgen E, et al: Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma:

A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial.

Lancet. 380:358–365. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Long GV, Weber JS, Infante JR, Kim KB,

Daud A, Gonzalez R, Sosman JA, Hamid O, Schuchter L, Cebon J, et

al: Overall survival and durable responses in patients with BRAF

V600-mutant metastatic melanoma receiving dabrafenib combined with

trametinib. J Clin Oncol. 34:871–878. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J,

Rutkowski P, Mackiewicz A, Stroiakovski D, Lichinitser M, Dummer R,

Grange F, Mortier L, et al: Improved overall survival in melanoma

with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 372:30–39.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sierra-Davidson K and Boland GM: Advances

in adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for melanoma. Hematol Oncol

Clin North Am. 38:953–971. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Corrie P, Meyer N, Berardi R, Guidoboni M,

Schlueter M, Kolovos S, Macabeo B, Trouiller JB and Laramée P:

Comparative efficacy and safety of targeted therapies for

BRAF-mutant unresectable or metastatic melanoma: Results from a

systematic literature review and a network meta-analysis. Cancer

Treat Rev. 110:1024632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Haist M, Stege H, Kuske M, Bauer J, Klumpp

A, Grabbe S and Bros M: Combination of immune-checkpoint inhibitors

and targeted therapies for melanoma therapy: The more, the better?

Cancer Metastasis Rev. 42:481–505. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Gutzmer R, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H,

Robert C, Lewis K, Protsenko S, Pereira RP, Eigentler T, Rutkowski

P, Demidov L, et al: Atezolizumab, vemurafenib, and cobimetinib as

first-line treatment for unresectable advanced BRAFV600

mutation-positive melanoma (IMspire150): Primary analysis of the

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 395:1835–1844. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Atkins MB, Lee SJ, Chmielowski B, Tarhini

AA, Cohen GI, Truong TG, Moon HH, Davar D, O'Rourke M, Stephenson

JJ, et al: Combination dabrafenib and trametinib versus combination

nivolumab and ipilimumab for patients with advanced BRAF-mutant

melanoma: The DREAMseq trial-ECOG-ACRIN EA6134. J Clin Oncol.

41:186–197. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ziogas DC, Martinos A, Petsiou DP,

Anastasopoulou A and Gogas H: Beyond immunotherapy: Seizing the

momentum of oncolytic viruses in the ideal platform of skin

cancers. Cancers (Basel). 14:28732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Puzanov I, Milhem MM, Minor D, Hamid O, Li

A, Chen L, Chastain M, Gorski KS, Anderson A, Chou J, et al:

Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab in

previously untreated, unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma. J Clin

Oncol. 34:2619–2626. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Gorry C, McCullagh L, O'Donnell H, Barrett

S, Schmitz S, Barry M, Curtin K, Beausang E, Barry R and Coyne I:

Neoadjuvant treatment for stage III and IV cutaneous melanoma.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1:CD0129742023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Patel SP, Othus M, Chen Y, Wright GP Jr,

Yost KJ, Hyngstrom JR, Hu-Lieskovan S, Lao CD, Fecher LA, Truong

TG, et al: Neoadjuvant-adjuvant or adjuvant-only pembrolizumab in

advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 388:813–823. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Amaria RN, Prieto PA, Tetzlaff MT, Reuben

A, Andrews MC, Ross MI, Glitza IC, Cormier J, Hwu WJ, Tawbi HA, et

al: Neoadjuvant plus adjuvant dabrafenib and trametinib versus

standard of care in patients with high-risk, surgically resectable

melanoma: A single-centre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial.

Lancet Oncol. 19:181–193. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Amaria RN, Menzies AM, Burton EM, Scolyer

RA, Tetzlaff MT, Antdbacka R, Ariyan C, Bassett R, Carter B, Daud

A, et al: Neoadjuvant systemic therapy in melanoma: Recommendations

of the international neoadjuvant melanoma consortium. Lancet Oncol.

20:e378–e389. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Swetter SM, Johnson D, Albertini MR,

Barker CA, Bateni S, Baumgartner J, Bhatia S, Bichakjian C, Boland

G, Chandra S, et al: NCCN guidelines® insights:

Melanoma: Cutaneous, version 2.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:290–298. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Spagnolo F, Ghiorzo P, Orgiano L,

Pastorino L, Picasso V, Tornari E, Ottaviano V and Queirolo P:

BRAF-mutant melanoma: Treatment approaches, resistance mechanisms,

and diagnostic strategies. OncoTargets Ther. 8:157–168. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Haugh AM and Johnson DB: Management of

V600E and V600K BRAF-mutant melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol.

20:812019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Long GV, Trefzer U, Davies MA, Kefford RF,

Ascierto PA, Chapman PB, Puzanov I, Hauschild A, Robert C, Algazi

A, et al: Dabrafenib in patients with Val600Glu or Val600Lys

BRAF-mutant melanoma metastatic to the brain (BREAK-MB): A

multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13:1087–1095.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Dummer R, Goldinger SM, Turtschi CP,

Eggmann NB, Michielin O, Mitchell L, Veronese L, Hilfiker PR,

Felderer L and Rinderknecht JD: Vemurafenib in patients with

BRAF(V600) mutation-positive melanoma with symptomatic brain

metastases: Final results of an open-label pilot study. Eur J

Cancer. 50:611–621. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, Grob JJ,

Flaherty KT, Arance A, Chiarion-Sileni V, Thomas L, Lesimple T,

Mortier L, et al: Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with

BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): A

multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

18:863–873. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Margolin K, Ernstoff MS, Hamid O, Lawrence

D, McDermott D, Puzanov I, Wolchok JD, Clark JI, Sznol M, Logan TF,

et al: Ipilimumab in patients with melanoma and brain metastases:

An open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13:459–465. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Jensen IS, Zacherle E, Blanchette CM,

Zhang J and Yin W: Evaluating cost benefits of combination

therapies for advanced melanoma. Drugs Context. 5:2122972016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Paraiso KHT, Xiang Y, Rebecca VW, Abel EV,

Chen YA, Munko AC, Wood E, Fedorenko IV, Sondak VK, Anderson AR, et

al: PTEN loss confers BRAF inhibitor resistance to melanoma cells

through the suppression of BIM expression. Cancer Res.

71:2750–2760. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Xing F, Persaud Y, Pratilas CA, Taylor BS,

Janakiraman M, She QB, Gallardo H, Liu C, Merghoub T, Hefter B, et

al: Concurrent loss of the PTEN and RB1 tumor suppressors

attenuates RAF dependence in melanomas harboring (V600E)BRAF.

Oncogene. 31:446–457. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Whittaker SR, Theurillat JP, Van Allen E,

Wagle N, Hsiao J, Cowley GS, Schadendorf D, Root DE and Garraway

LA: A genome-scale RNA interference screen implicates NF1 loss in

resistance to RAF inhibition. Cancer Discov. 3:350–362. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Nissan MH, Pratilas CA, Jones AM, Ramirez

R, Won H, Liu C, Tiwari S, Kong L, Hanrahan AJ, Yao Z, et al: Loss

of NF1 in cutaneous melanoma is associated with RAS activation and

MEK dependence. Cancer Res. 74:2340–2350. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Ye Q, Viale A,

Sander C, Solit DB and Rosen N: (V600E)BRAF is associated with

disabled feedback inhibition of RAF-MEK signaling and elevated

transcriptional output of the pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

106:4519–4524. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Shi H, Moriceau G, Kong X, Koya RC,

Nazarian R, Pupo GM, Bacchiocchi A, Dahlman KB, Chmielowski B,

Sosman JA, et al: Preexisting MEK1 exon 3 mutations in V600E/KBRAF

melanomas do not confer resistance to BRAF inhibitors. Cancer

Discov. 2:414–424. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M,

Kong X, Ng C, Moriceau G, Shi H, Atefi M, Titz B, Gabay MT, et al:

RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly

spliced BRAF(V600E). Nature. 480:387–390. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Shi H, Moriceau G, Kong X, Lee MK, Lee H,

Koya RC, Ng C, Chodon T, Scolyer RA, Dahlman KB, et al: Melanoma

whole-exome sequencing identifies (V600E)B-RAF

amplification-mediated acquired B-RAF inhibitor resistance. Nat

Commun. 3:7242012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Augustin RC and Luke JJ: Rapidly evolving

pre- and post-surgical systemic treatment of melanoma. Am J Clin

Dermatol. 25:421–434. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|