Introduction

Lung cancer remains a global health crisis, which

ranks as the second most common malignancy worldwide by incidence

and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality (1,2). In

China, lung cancer holds the highest incidence and mortality rates

among all cancer types (1,2). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),

which accounts for ~85% of lung cancer cases, is characterized by

its insidious onset and lack of early symptoms, which results in

>70% of patients being diagnosed at advanced stages when

surgical resection is no longer feasible (3). For these patients, multimodal

therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy,

immunotherapy and anti-angiogenic agents form the cornerstone of

treatment (4).

The gemcitabine-cisplatin (GP) regimen is a

first-line chemotherapy option for advanced NSCLC. However, the

long-term application of GP is limited by cumulative toxicity and

variable efficacy, which underscores the need for safer and more

effective therapeutic strategies (4). Tislelizumab, a humanized monoclonal

antibody targeting programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), has

emerged as a potential immunotherapeutic agent. PD-1, expressed on

activated T cells, binds to its ligands programmed death ligand

(PD-L)1 and PD-L2, which are often upregulated on tumor cells and

other cells within the tumor microenvironment, such as

antigen-presenting cells including macrophages and dendritic cells

(5). This interaction delivers an

inhibitory signal that dampens T-cell effector functions, such as

cytokine production and cytotoxicity, which allows cancer cells to

evade immune destruction (5,6). By

blocking PD-1-mediated immunosuppression, tislelizumab prevents

this inhibitory signaling, thereby unleashing antitumor T-cell

activity and potentiating tumor cell apoptosis. Initially approved

for relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma, tislelizumab has demonstrated

efficacy in gastrointestinal cancer types, esophageal carcinoma and

NSCLC, which offers potential survival benefits (7). Ongoing research continues to explore

the efficacy of tislelizumab in diverse cancer types and

combination strategies, which aim to further optimize its clinical

application and patient outcomes (8).

Serum biomarkers such as CEA, CA125 and cytokeratin

19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) serve key roles in cancer monitoring

(9). CEA, a glycoprotein associated

with epithelial malignancies, is elevated in 30–60% of NSCLC cases,

and has been associated with tumor burden and progression (10). CA125, traditionally associated with

ovarian cancer, is also aberrantly expressed in NSCLC, which

reflects pleural involvement or metastatic spread (11). CYFRA21-1, a structural component of

epithelial cell cytokeratins, facilitates tumor cell detachment and

metastasis by disrupting intercellular adhesion (12). These biomarkers collectively provide

a non-invasive tool for the assessment of therapeutic response and

prognosis.

Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was

to compare the efficacy, long-term survival and safety of

tislelizumab + GP chemotherapy against GP chemotherapy alone in

patients with advanced NSCLC. As a secondary objective, the present

study sought to address the gap in monitoring tools by analyzing

the predictive value of a combined panel of serum CEA, CA125 and

CYFRA21-1 to evaluate the short-term efficacy of the

tislelizumab-based regimen.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present study protocol was approved by the

Ethics Committee of Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical

University (approval no. HRB-2020-23; Harbin, China) and was

performed in accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki. Written

informed consent was obtained from all study subjects before

enrollment. Sample size was estimated based on an anticipated 20%

improvement in objective response rate (ORR) with the addition of

tislelizumab (from 25 to 45%), which required ≤42 patients per

group to achieve 80% power at a two-sided α level of 0.05. To

account for potential dropouts, 45 patients per group were enrolled

in the present study.

A total of 90 patients diagnosed with advanced NSCLC

between January 2021 and December 2024 were enrolled in the present

study. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either

the study group (n=45) or the control group (n=45) using a

computer-generated randomization sequence. Allocation concealment

was ensured by the Investigational Drug Service pharmacy of the

Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, which

dispensed the study drugs according to the computer-generated

randomization sequence. Inclusion criteria required patients to

meet the diagnostic standards for NSCLC outlined in the Chinese

Clinical Guidelines for Radiotherapy of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

(2020 Edition) (13), confirmed

through lung biopsy and imaging studies. Eligible patients had TNM

stage (14) IIIa-IIIc disease

without surgical indications, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

performance status (15) of 0 or 1

and were candidates for chemotherapy, and exhibited no

contraindications to tislelizumab, gemcitabine or cisplatin.

Additional criteria included an expected survival period of >3

months and provision of written informed consent. Exclusion

criteria encompassed severe infections, concurrent primary

malignancies, notable organ dysfunction (for example, heart, liver

or kidney failure), cognitive impairments affecting treatment

compliance, prior chemotherapy exposure, treatment interruptions

during the present study, loss to follow-up, hematopoietic or

systemic dysfunction, and pregnancy or lactation.

Interventions

The control group received the GP chemotherapy

regimen. Gemcitabine hydrochloride (0.2 g/vial; Harbin Yulian

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was administered intravenously at 1.2

g/m2 diluted in 100 ml 0.9% sodium chloride on days 1

and 8 of a 21-day cycle. Cisplatin (10 ml/10 mg; Guangdong Lingnan

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was administered intravenously at 75

mg/m2 diluted in 500 ml 0.9% sodium chloride on day 1 of

each cycle. Treatment continued for 4–6 cycles (3–4.5 months, with

biomarker assessment after 3 months as planned).

The study group received tislelizumab combined with

the same GP regimen. Tislelizumab (10 ml/100 mg; Boehringer

Ingelheim Biopharmaceuticals) was administered at 200 mg per dose,

diluted in 100 ml 0.9% sodium chloride, via intravenous infusion

every 3 weeks. The treatment duration and chemotherapy protocol

matched those of the control group.

Outcome measures

Short-term efficacy was evaluated according to the

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1)

(16), referenced alongside the

Chinese Expert Consensus on PD-L1 Immunohistochemical Testing in

NSCLC (17). Complete response (CR)

was defined as the disappearance of all target lesions maintained

for ≤4 weeks, while partial response (PR) referred to a ≥30%

reduction in the sum of diameters of target lesions. Stable disease

(SD) indicated neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor

sufficient increase to qualify for PD, and progressive disease (PD)

was characterized by ≥20% increase in the sum of diameters of

target lesions or the appearance of novel metastases. ORR (%) and

disease control rate [DCR (%)] were calculated as (CR + PR)/total

cases ×100 and (CR + PR + SD)/total cases ×100, respectively.

Long-term efficacy outcomes included

progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from

randomization to disease progression or death from any cause, and

overall survival (OS), defined as the time from randomization to

death from any cause. Patients were followed up every 3 months. The

data cut-off date for the present analysis was May 31, 2025.

Serum levels of CEA, CA125 and CYFRA21-1 were

measured pre-treatment and 3 months post-treatment. Fasting venous

blood (4 ml) was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at room

temperature and serum was analyzed via electrochemiluminescence

using the Cobas e601 immunoassay analyzer and corresponding kits

(Elecsys CEA Immunoassay, cat. no. YDLC-15737; Elecsys CA125 II

Immunoassay, cat. no. YDLC-15799; Elecsys CYFRA 21-1 Immunoassay,

cat. no. YDLC-9257; all from Shanghai Yuduo Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). Each biomarker was evaluated in triplicate, with means

recorded. Positive thresholds were defined as >5 ng/ml for CEA,

>35 U/ml for CA125 and >3.3 ng/ml for CYFRA21-1.

Adverse events (AEs) were classified using the

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events by the National

Cancer Institute (version 5.0) (18). Receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve analysis evaluated the predictive value of biomarkers

for short-term therapeutic efficacy.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp.) was employed for data

analysis. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed

as the mean ± SD and compared using unpaired Student's t-test,

while non-normally distributed variables were reported as the

median (interquartile range) and analyzed using Mann-Whitney U

test. Categorical data were described as frequencies (%) and

assessed via χ2 or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate.

PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and

differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% CIs were calculated using Cox

proportional hazards models. ROC curves determined sensitivity,

specificity and area under the curve (AUC) for biomarkers. The

DeLong test was used to assess the statistical significance of the

differences between the AUC of the combined biomarker panel and

those of the individual markers. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the two

groups

No statistically significant differences were

observed between the study and control groups in terms of age, sex,

smoking history, alcohol consumption, clinical stage or

histological subtypes (P>0.05), as detailed in Table I. The mean age was 53.23±8.03 years

in the control group vs. 53.09±8.76 years in the study group

(t=−0.079; P=0.937). Male/female ratios were comparable (31/14 vs.

33/12; χ2=0.216; P=0.642), as were smoking (12 vs. 14)

and alcohol consumption (9 vs. 13) rates. Both groups exhibited

similar distributions of advanced-stage disease (Stage III, 17 vs.

16; Stage IV, 28 vs. 29) and histological classifications (squamous

carcinoma, 16 vs. 14; adenocarcinoma, 29 vs. 31). Tumor

localization and laterality (left lung, 19 vs. 17; right lung, 24

vs. 27; bilateral, 2 vs. 1) also demonstrated no significant

differences (P>0.05 for all comparisons).

| Table I.Comparison of general patient

characteristics between the two groups. |

Table I.

Comparison of general patient

characteristics between the two groups.

| Characteristic | Control group

(n=45) | Study group

(n=45) |

t/χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 53.23±8.03 | 53.09±8.76 | −0.079 | 0.937 |

| Male/female sex,

n | 31/14 | 33/12 | 0.216 | 0.642 |

| Smoking, n | 12 | 14 | 0.216 | 0.642 |

| Alcohol

consumption, n | 9 | 13 | 0.963 | 0.326 |

| Clinical stage (I),

n |

|

| 0.048 | 0.827 |

| Stage

III | 17 | 16 |

|

|

| Stage

IV | 28 | 29 |

|

|

| Pathological type,

n |

|

| 0.200 | 0.655 |

|

Squamous carcinoma | 16 | 14 |

|

|

|

Adenocarcinoma | 29 | 31 |

|

|

| Primary site,

n |

|

| 0.563 | 0.905 |

| Upper

lobe | 5 | 6 |

|

|

| Middle

lobe | 24 | 26 |

|

|

| Lower

lobe | 7 | 5 |

|

|

|

Overlap | 9 | 8 |

|

|

| Tumor location,

n |

|

| - | 0.745a |

| Left

lung | 19 | 17 |

|

|

| Right

lung | 24 | 27 |

|

|

|

Bilateral | 2 | 1 |

|

|

Short-term efficacy outcomes

The study group demonstrated numerically higher ORR

(33.33 vs. 22.22%) and DCR (77.78 vs. 60.00%) compared with the

control group; however, these differences did not reach statistical

significance (P=0.239 and P=0.069, respectively) (Table II). In the study group, 5 patients

achieved CR and 10 demonstrated PR, whereas the control group had 3

CR and 7 PR cases. SD was observed in 20 patients in the study

group vs. 17 in the control group, and PD occurred in 10 patients

in the study group vs. 19 in the control group, which favored the

tislelizumab combination regimen.

| Table II.Comparison of short-term treatment

efficacy between the two groups. |

Table II.

Comparison of short-term treatment

efficacy between the two groups.

| Outcome

measure | Control group

(n=45) | Study group

(n=45) |

t/χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| CR, n | 3 | 5 |

|

|

| PR, n | 7 | 10 |

|

|

| SD, n | 17 | 20 |

|

|

| PD, n | 19 | 10 |

|

|

| ORR, n (%) | 10 (22.22) | 15 (33.33) | 1.385 | 0.239 |

| DCR, n (%) | 27 (60.00) | 35 (77.78) | 3.318 | 0.069 |

Predictive value of serum biomarkers

for short-term therapeutic efficacy

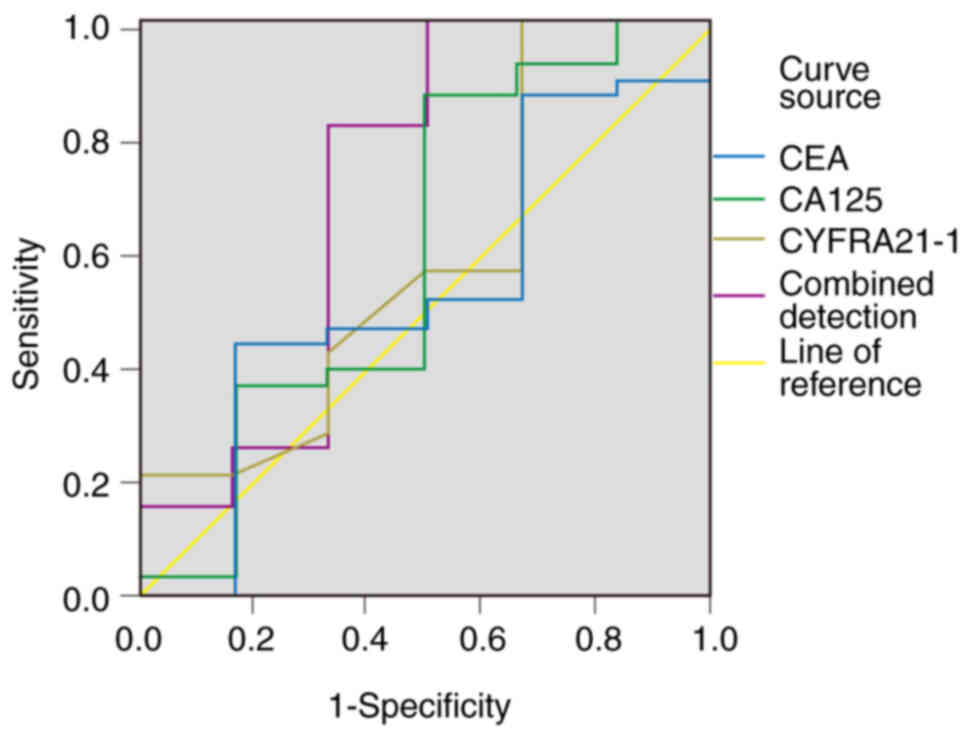

ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the combination

of CEA, CA125 and CYFRA21-1 levels provided notable predictive

performance for evaluating the short-term efficacy of tislelizumab

+ GP chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC, compared with

individual biomarkers (Table III;

Fig. 1). The combined model

achieved the highest AUC (0.705; 95% CI, 0.411–0.999), sensitivity

(87.16%) and specificity (88.35%), which significantly outperformed

individual markers (χ2=9.021; P<0.05). By contrast,

no significant differences were observed among the individual

biomarkers: i) CEA demonstrated an AUC of 0.530 (95% CI,

0.269–0.791), sensitivity of 73.23%, specificity of 68.79% at a

cut-off of 89.15 pg/ml; ii) CA125 demonstrated an AUC of 0.594 (95%

CI, 0.297–0.891), sensitivity of 76.56%, specificity of 70.67% at

31.4 U/ml; iii) CYFRA21-1 demonstrated an AUC of 0.583 (95% CI,

0.312–0.855), sensitivity of 74.64%, specificity of 69.67% at 19.05

ng/ml.

| Table III.Evaluation of the efficacy of CEA,

CA125, CYFRA21-1 levels and combined detection for the short-term

treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with tislelizumab combined

with gemcitabine-cisplatin chemotherapy. |

Table III.

Evaluation of the efficacy of CEA,

CA125, CYFRA21-1 levels and combined detection for the short-term

treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with tislelizumab combined

with gemcitabine-cisplatin chemotherapy.

| Factor | AUC (95% CI) | Key value | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % |

|---|

| CEA, pg/ml | 0.530

(0.269–0.791) | 89.15 | 73.23 | 68.79 |

| CA125, U/ml | 0.594

(0.297–0.891) | 31.4 | 76.56 | 70.67 |

| CYFRA21-1,

ng/ml | 0.583

(0.312–0.855) | 19.05 | 74.64 | 69.67 |

| Combined

detection | 0.705

(0.411–0.999) | - | 87.16 | 88.35 |

Long-term efficacy outcomes

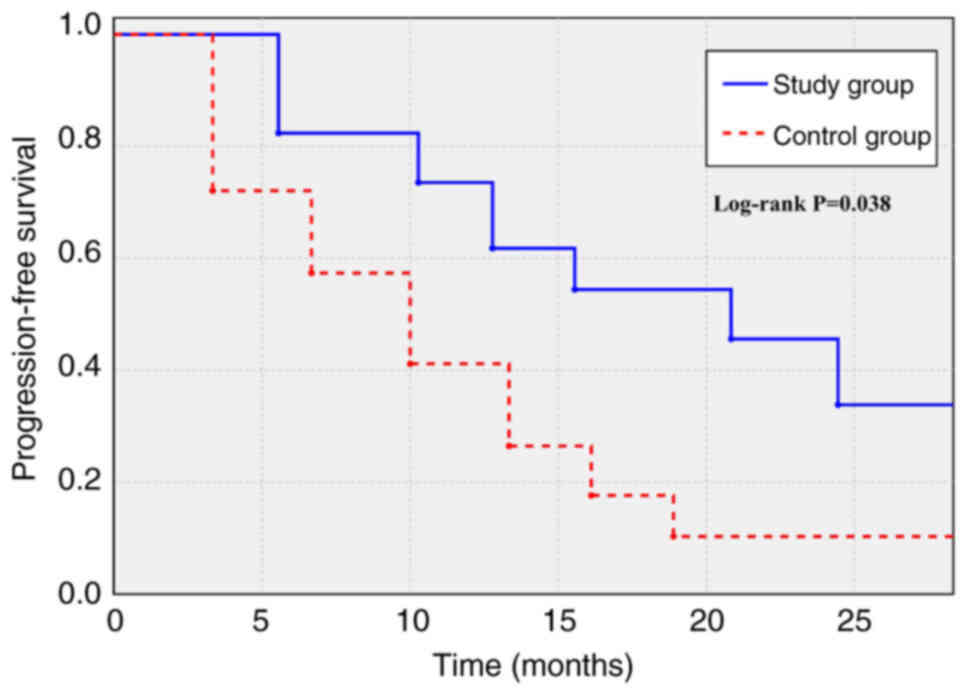

The median follow-up duration for the entire cohort

was 23.5 months (range, 5.0–52.0 months). Long-term follow-up data

revealed notable survival outcomes in the study group compared with

those in the control group. As shown in the Kaplan-Meier analysis

for PFS (Fig. 2), the median PFS

(the time at which 50% of patients were progression-free) was

significantly longer in the study group (20.8 months; 95% CI,

13.6–25.4) compared with in the control group (10.0 months; 95% CI,

7.1–12.9) (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.43–0.98; log-rank P=0.038).

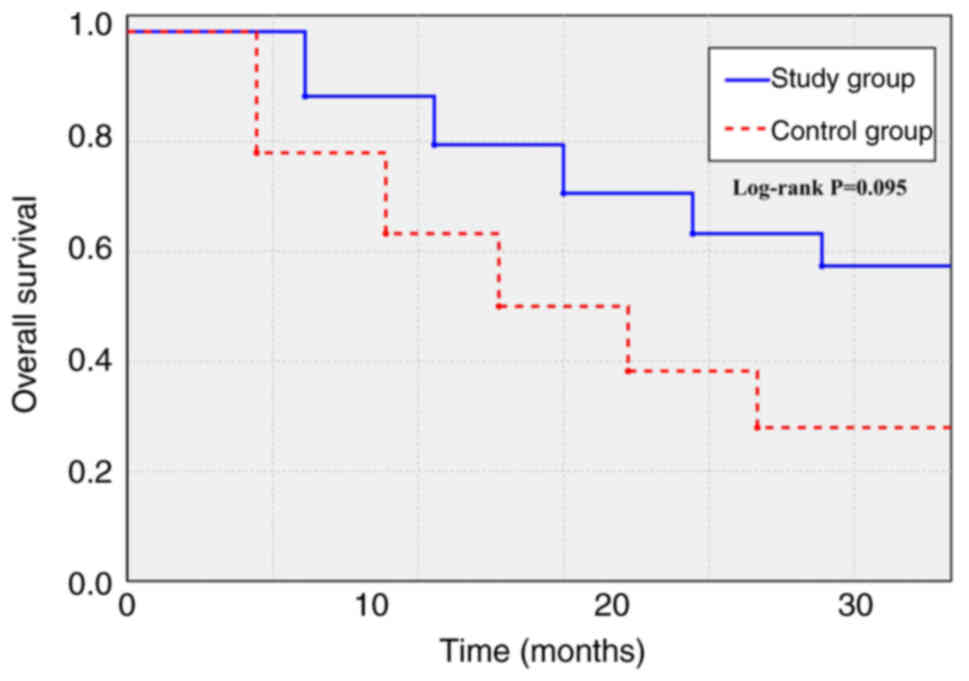

Regarding OS (Fig. 3), the study

group demonstrated a trend towards improvement, with a median OS

(the time at which 50% of patients remained alive) that was not

reached (95% CI, 19.8-not reached) compared with 16.0 months (95%

CI, 13.5–18.5) in the control group (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.47–1.07;

log-rank P=0.095).

Serum biomarker levels

Pretreatment levels of CEA, CA125 and CYFRA21-1 were

comparable between groups (P>0.05) (Table IV). At 3 months post-treatment, the

study group exhibited significantly lower biomarker levels compared

with the control group for CEA [4.02±0.82 ng/ml vs. 4.61±0.89 ng/ml

(t=−3.270; P=0.002)], CA125 [42.18±5.82 U/ml vs. 49.76±5.66 U/ml

(t=−6.263; P<0.001)] and CYFRA21-1 [3.42±0.43 ng/ml vs.

4.39±0.56 ng/ml (t=9.216; P<0.001)].

| Table IV.Comparison of CEA, CA125 and

CYFRA21-1 levels between the two groups. |

Table IV.

Comparison of CEA, CA125 and

CYFRA21-1 levels between the two groups.

| A, CEA, ng/ml |

|---|

|

|---|

| Time | Control group

(n=45) | Study group

(n=45) | t | P-value |

|---|

| Before treatment (1

day) | 6.23±0.94 | 6.19±0.97 | −0.199 | 0.843 |

| 3 months after

treatment | 4.61±0.89 | 4.02±0.82 | −3.270 | 0.002 |

|

| B, CA125,

U/ml |

|

| Time | Control group

(n=45) | Study group

(n=45) | t | P-value |

|

| Before treatment (1

day) | 63.98±5.32 | 64.23±5.86 | 0.212 | 0.833 |

| 3 months after

treatment | 49.76±5.66 | 42.18±5.82 | −6.263 | <0.001 |

|

| C, CYFRA21-1,

ng/ml |

|

| Time | Control group

(n=45) | Study group

(n=45) | t | P-value |

|

| Before treatment (1

day) | 6.34±0.76 | 6.29±0.81 | −0.302 | 0.763 |

| 3 months after

treatment | 4.39±0.56 | 3.42±0.43 | −9.216 | <0.001 |

Comparison of AEs

The incidence of AEs in the study group was

numerically lower compared with that in the control group, although

no statistically significant differences were observed (P>0.05

for all comparisons) (Table V).

Grade I anemia occurred in 4 patients in the control group vs. 2

patients in the study group (χ2=0.714; P=0.398), whereas

Grade II anemia was reported in 2 vs. 1 cases (χ2=0.322;

P=0.570). Neutropenia rates were similarly comparable: Grade I (3

vs. 2; χ2=0.212; P=0.645) and Grade II (2 vs. 1;

χ2=0.345; P=0.557). Elevated alkaline phosphatase levels

also indicated no significant intergroup differences, with similar

numbers of Grade I (3 vs. 2) and Grade II (2 vs. 1) events.

Cutaneous reactions such as Grade I maculopapular rash (1 vs. 0;

χ2=1.011; P=0.315) and gastrointestinal toxicities,

including Grade I nausea (12 vs. 8; χ2=1.029; P=0.310),

Grade II nausea (8 vs. 11; χ2=0.600; P=0.439) and Grade

I vomiting (9 vs. 5; χ2=1.353; P=0.245), were marginally

reduced in the study group but did not reach statistical

significance.

| Table V.Comparison of adverse reactions

between the control (n=45) and study (n=45) groups. |

Table V.

Comparison of adverse reactions

between the control (n=45) and study (n=45) groups.

| Adverse event | Control group

(n=45) | Study group

(n=45) | P-value |

|---|

| Anemia |

|

|

|

| Grade

I | 4 | 2 | 0.438ª |

| Grade

II | 2 | 1 | 0.616ª |

| Neutropenia |

|

|

|

| Grade

I | 3 | 2 | 0.695ª |

| Grade

II | 2 | 1 | 0.616ª |

| Alkaline

phosphatase elevation |

|

|

|

| Grade

I | 3 | 2 | 0.695ª |

| Grade

II | 2 | 1 | 0.616ª |

| Grade I rash | 1 | 0 | 0.494ª |

| Nausea |

|

|

|

| Grade

I | 12 | 8 | 0.294b |

| Grade

II | 8 | 11 | 0.439b |

| Grade I

vomiting | 9 | 5 | 0.245b |

Discussion

NSCLC is a highly aggressive malignancy

characterized by insidious onset, rapid progression and a lack of

effective early diagnostic methods. Most patients are diagnosed at

advanced stages (III or IV) with local or distant metastases,

resulting in a poor prognosis, with the 5-year survival rate for

distant-stage disease being ~7% (19). Currently, the GP chemotherapy

regimen remains a common first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC.

While it improves local control rates, survival rates and reduces

distant metastases to some extent, its efficacy is limited by

factors such as tumor sensitivity, drug resistance, dose-limiting

toxicity and compromised patient performance status (20). Furthermore, chemotherapy-induced

toxicities, such as damage to germ, gastrointestinal epithelial and

immune cells (for example, lymphocytes and hematopoietic cells)

exacerbate immune dysfunction, impair antitumor responses and

accelerate disease progression (21).

Recent advances in immunotherapy, particularly

immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1/PD-L1, have

revolutionized NSCLC management (22–24).

Tumor cells evade immune surveillance by expressing PD-L1, which

binds to PD-1 on T cells, suppressing their activity. ICIs block

this interaction, which restores T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity

and inhibits cancer progression (25). Tislelizumab, a novel PD-1 monoclonal

antibody developed in China, exhibits enhanced antitumor activity

compared with traditional PD-1 inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab

and nivolumab, due to structural modifications in its

crystallizable fragment (Fc) region, which minimizes binding to Fcγ

receptors on macrophages, thereby reducing antibody-dependent

phagocytosis of T cells (26). It

demonstrates lower IC50 values, higher binding affinity

and improved safety profiles, particularly reduced incidences of

capillary hyperplasia, compared with other agents such as

camrelizumab. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness of tislelizumab

compared with imported PD-1 inhibitors (for example, pembrolizumab

and atezolizumab) enhances patient accessibility (25,27).

The combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy

is founded on several potential synergistic mechanisms.

Chemotherapy can induce immunogenic cell death, which releases

tumor antigens (such as CALR and HMGB1) and damage-associated

molecular patterns (including ATP and Hsp70/90) that can prime and

enhance antitumor T-cell responses (28). Furthermore, chemotherapy may

modulate the tumor microenvironment by reducing the numbers of

immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells and

myeloid-derived suppressor cells and by upregulating PD-L1

expression on tumor cells, potentially sensitizing them to PD-1

blockade (29). Tislelizumab, by

invigorating the T-cell response, can then more effectively target

and eliminate tumor cells rendered vulnerable by chemotherapy.

Although chemotherapy alone can induce some level of immunogenic

cell death, its clinical success is limited because this effect is

often transient and insufficient to overcome the highly

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Tumors employ multiple

escape mechanisms, of which the chief mechanism is the upregulation

of checkpoint proteins such as PD-L1, which actively inhibit T-cell

function and lead to T-cell exhaustion. Therefore, even if

chemotherapy enhances antigen presentation, the responding T cells

remain suppressed. This limitation highlights the rationale for

combination therapy: Chemotherapy acts to increase tumor

immunogenicity, while tislelizumab simultaneously blocks the

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory axis, thereby unleashing a potent and durable

antitumor T-cell response that neither agent could achieve alone

(30).

The present study findings regarding short-term

efficacy (ORR and DCR) exhibited numerically higher rates in the

tislelizumab-GP group; however, these differences were not

statistically significant. This lack of statistical significance

might be attributed to the relatively small sample size. However,

the observed trend, coupled with the significant improvement in

median PFS (11.8 vs. 8.7 months; P=0.038) and the positive trend in

OS (median 23.5 vs. 18.2 months; P=0.095) at a median follow-up of

23.5 months, suggested a clinically meaningful benefit from the

addition of tislelizumab to GP chemotherapy. This aligns with

findings from several large-scale trials but also highlights the

ongoing debate, as outcomes can vary based on study design, patient

populations and treatment regimens. For example, Santoro et

al (31) evaluated

spartalizumab and various chemotherapy backbones in a

PD-L1-unselected metastatic NSCLC population, and provided a

relevant comparison. Their gemcitabine/cisplatin group (Group A)

reported a higher ORR (57.6%) compared with the present study

(33.33%); however, the median PFS (7.5 months) was shorter compared

with 11.8 months from the present study results, which suggests

potential differences in drug-specific activity or patient

characteristics. By contrast, a meta-analysis by Zhou et al

(32) offers a different

perspective, which focused on the neoadjuvant setting for

resectable NSCLC. It concluded that the addition of adjuvant

immunotherapy to a neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy regimen did not

improve PFS or OS; however, this previous study had a different

clinical question and setting compared with the focus of the

present study on first-line treatment for advanced, unresectable

disease. Furthermore, Mathew et al (33) outlined the preclinical rationale for

these combinations in a review article, but did not provide

comparative clinical trial data. A notable comparison is the

EMPOWER-Lung 3 trial by Makharadze et al (34), which evaluated cemiplimab +

chemotherapy in first-line, advanced NSCLC irrespective of PD-L1

status. This previous study reported an ORR of 43.6% and a median

PFS of 8.2 months (HR, 0.55), with a median OS of 21.1 months.

Although the ORR in this previous study was higher, the present

study exhibited a more favorable median PFS (11.8 months), a

difference that might be attributed to the specific GP regimen,

regional population differences or other unmeasured patient

factors. Finally, Zhu et al (35) also evaluated a distinct setting:

Neoadjuvant toripalimab + chemotherapy in resectable stage II–III

NSCLC. Its primary endpoints were the major pathological response

rate (55.6%) and R0 resection rate (100%), which are not applicable

to the palliative-intent treatment of the advanced-stage cohort in

the present study. This highlights the key importance of treatment

setting when comparing efficacy outcomes.

Serum biomarkers such as CEA, CA125 and CYFRA21-1

are key for monitoring therapeutic efficacy. The present study

corroborated findings from Strum et al (36) and Clevers et al (37), which reported markedly reduced

post-treatment levels of all three biomarkers in the

tislelizumab-GP group (P<0.05). These reductions are considered

clinically relevant as they may reflect a decrease in tumor burden.

The ROC analysis in the present study further revealed that the

multi-biomarker panel outperformed individual markers in the

prediction of short-term therapeutic outcomes, which underscores

their clinical utility for early response assessment.

Safety is a key consideration. In the present study

cohort, AEs were manageable and comparable between groups, which

supports the tolerability of the combination regimen. This

practical implication, that the addition of tislelizumab does not

markedly exacerbate toxicity, makes it a viable option for patients

who can tolerate standard chemotherapy. Despite these potential

synergies, the widespread adoption of tislelizumab and other ICIs

faces challenges. A primary concern is the occurrence of

immune-related AEs (irAEs), which can affect any organ system and

include pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis and endocrinopathies.

Although often manageable, these irAEs can be severe or even

life-threatening, which requires vigilant monitoring and

specialized management, with fatal outcomes reported particularly

for pneumonitis, hepatitis, colitis and myocarditis (38). Furthermore, a notable portion of

patients exhibit primary or acquired resistance to ICI therapy,

which limits its long-term benefit, with resistance rates varying

markedly between monotherapies (for example, ~30% for PD-1

inhibitors) and combination therapies (for example, 60–70% for

CTLA-4 inhibitors or combinations) (39). The modest predictive power of

biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression indicates that patient

selection remains suboptimal due to the lack of reliable biomarkers

(39,40). These factors, combined with the high

cost of immunotherapy, contribute to the complexities of its

integration into routine clinical practice (39).

The present study had several limitations. Firstly,

the sample size was relatively small, which may have limited the

statistical power to detect significant differences in some

secondary outcomes, such as ORR, DCR and 2-year survival rates, and

may have affected the generalizability of the findings. Secondly,

it was a single-center study, which potentially introduced

selection bias. Thirdly, while the present study incorporated

long-term follow-up for PFS and OS, further follow-up would have

been beneficial to ascertain the durability of the observed

survival benefits. Finally, PD-L1 expression status was not

uniformly assessed or associated with outcomes. Future multicenter

studies with larger sample sizes and comprehensive biomarker

analyses are warranted.

In conclusion, the addition of tislelizumab to GP

chemotherapy markedly improved PFS and exhibited a favorable trend

towards improved OS in advanced NSCLC, with a manageable safety

profile. The combined assessment of serum CEA, CA125 and CYFRA21-1

provides robust predictive value for short-term therapeutic

monitoring. These findings advocate for the consideration of

tislelizumab-based combinations in NSCLC, which offers a more

effective therapeutic option, while the biomarker panel can

potentially aid in early clinical decision-making in the

future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LW conceptualized the study, designed the

methodology and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. TG

performed data acquisition and analysis, and contributed to the

preparation of the original draft. YC performed data analysis and

data visualization. ML provided supervision and performed the

statistical analyses using the appropriate software. YW contributed

to the development of the methodology, and also reviewed and edited

the manuscript. LW and TG confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study protocol was approved by the

relevant Ethics Committee of Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin

Medical University (approval no. HRB-2020-23; Harbin, China). The

study was performed in accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki

and written informed consent was obtained from all of the present

study subjects before enrollment.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Riely GJ, Wood DE, Ettinger DS, Aisner DL,

Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, et

al: Non-small cell lung cancer, version 4.2024, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:249–274. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley

W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, D'Amico

TA, et al: Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN

clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

20:497–530. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Miao D, Zhao J, Han Y, Zhou J, Li X, Zhang

T, Li W and Xia Y: Management of locally advanced non-small cell

lung cancer: State of the art and future directions. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 44:23–46. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Guan H, He Y, Wei Z, Wang J, He L, Mu X

and Peng X: Assessment of induction chemotherapy regimen TPF vs GP

followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced

nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study of 160

patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 45:274–279. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dermani FK, Samadi P, Rahmani G, Kohlan AK

and Najafi R: PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint: Potential target for

cancer therapy. J Cell Physiol. 234:1313–1325. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K,

Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne

MC, et al: Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a

novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte

activation. J Exp Med. 192:1027–1034. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jiang C, McKay RM, Lee SY, Romo CG,

Blakeley JO, Haniffa M, Serra E, Steensma MR, Largaespada D and Le

LQ: Cutaneous neurofibroma heterogeneity: Factors that influence

tumor burden in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Invest Dermatol.

143:1369–1377. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Abushanab AK, Mustafa MT, Mousa MT,

Qawaqzeh RA, Alqudah GN and Albanawi RF: Efficacy and safety of

tislelizumab for malignant solid tumor: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of phase III randomized trials. Expert Rev Clin

Pharmacol. 16:1153–1161. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wu S: Value of Combined Detection of

CYFRA21-1, CA125, CEA, NSE and SCCA Serum in the Diagnosis of Lung

Cancer. Guide China Med. 22:47–50. 2024.(In Chinese).

|

|

10

|

Kobayashi K, Ono Y, Kitano Y, Oba A, Sato

T, Ito H, Mise Y, Shinozaki E, Inoue Y, Yamaguchi K, et al:

Prognostic impact of tumor markers (CEA and CA19-9) on patients

with resectable colorectal liver metastases stratified by tumor

number and size: Potentially valuable biologic markers for

preoperative treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 30:7338–7347. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang ZH, Han YW, Liang H and Wang LM:

Prognostic value of serum CYFRA21-1 and CEA for non-small-cell lung

cancer. Cancer Med. 4:1633–1638. 2015. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen F and Zhang X: Predictive value of

serum SCCA and CYFRA21-1 levels on radiotherapy efficacy and

prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Biotechnol

Genet Eng Rev. 40:4205–4214. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Radiation Oncology Branch of Chinese

Medical Association, Radiation Oncologist Branch of Chinese Medical

Doctor Association Professional Committee on Radiation Oncology,

China Anti-Cancer Association Experts Committee on Radiation

Oncology and Radiation Oncologist Branch of Chinese Society of

Clinical Oncology, . Clinical practice guideline for radiation

therapy in small cell lung cancer (2020 version). Chin J Radiat

Oncol. 29:608–614. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

14

|

Fleming ID: AJCC/TNM cancer staging,

present and future. J Surg Oncol. 77:233–236. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chinese Anti-Cancer Association, Lung

Cancer Study Group of Committee of Oncopathology, Chinese Society

of Lung Cancer and Expert Group on PD-L1 Testing Consensus, .

Chinese Expert Consensus on Standards of PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry

Testing for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Chin J Lung Cancer.

23:733–740. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

18

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE)

version 5.0, 2017. https://dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-5×7.pdfJune

15–2025

|

|

19

|

Spitaleri G, Trillo Aliaga P, Attili I,

Del Signore E, Corvaja C, Corti C, Crimini E, Passaro A and de

Marinis F: Sustained improvement in the management of patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring ALK translocation:

where are we running? Curr Oncol. 30:5072–5092. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lv P and Liu M: Meta-analysis of the

clinical effect of Kanglaite injection-assisted gemcitabine plus

cisplatin regimen on non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Transl Res.

15:2999–3012. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wakelee H: Chemotherapy and immunotherapy

in early-stage NSCLC: Neoadjuvant vs adjuvant therapy. Clin Adv

Hematol Oncol. 21:648–651. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Olivares-Hernández A, González Del

Portillo E, Tamayo-Velasco Á, Figuero-Pérez L, Zhilina-Zhilina S,

Fonseca-Sánchez E and Miramontes-González JP: Immune checkpoint

inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: From current perspectives

to future treatments-a systematic review. Ann Transl Med.

11:3542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mizuno T, Katsuya Y, Sato J, Koyama T,

Shimizu T and Yamamoto N: Emerging PD-1/PD-L1 targeting

immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: Current status and

future perspective in Japan, US, EU, and China. Front Oncol.

12:9259382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lim SM, Hong MH and Kim HR: Immunotherapy

for non-small cell lung cancer: Current landscape and future

perspectives. Immune Netw. 20:e102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jackson M, Ahmari N, Wu J, Rizvi TA,

Fugate E, Kim MO, Dombi E, Arnhof H, Boehmelt G, Düchs MJ, et al:

Combining SOS1 and MEK inhibitors in a murine model of plexiform

neurofibroma results in tumor shrinkage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther.

385:106–116. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang T, Song X, Xu L, Ma J, Zhang Y, Gong

W, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Wang Z, Wang Y, et al: The binding of an

anti-PD-1 antibody to FcγRI has a profound impact on its biological

functions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 67:1079–1090. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kresbach C, Dottermusch M, Eckhardt A,

Ristow I, Paplomatas P, Altendorf L, Wefers AK, Bockmayr M,

Belakhoua S, Tran I, et al: Atypical neurofibromas reveal distinct

epigenetic features with proximity to benign peripheral nerve

sheath tumor entities. Neuro Oncol. 25:1644–1655. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Galluzzi L, Buqué A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L

and Kroemer G: Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious

disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 17:97–111. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Poon E, Mullins S, Watkins A, Williams GS,

Koopmann JO, Di Genova G, Cumberbatch M, Veldman-Jones M,

Grosskurth SE, Sah V, et al: The MEK inhibitor selumetinib

complements CTLA-4 blockade by reprogramming the tumor immune

microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 5:632017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liang X, Chen X, Li H and Li Y:

Tislelizumab plus chemotherapy is more cost-effective than

chemotherapy alone as first-line therapy for advanced non-squamous

non-small cell lung cancer. Front Public Health. 11:10099202023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Santoro A, Pilar G, Tan DSW, Zugazagoitia

J, Shepherd FA, Bearz A, Barlesi F, Kim TM, Overbeck TR, Felip E,

et al: Spartalizumab in combination with platinum-doublet

chemotherapy with or without canakinumab in patients with

PD-L1-unselected, metastatic NSCLC. BMC Cancer. 24:13072024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhou Y, Li A, Yu H, Wang Y, Zhang X, Qiu

H, Du W, Luo L, Fu S, Zhang L and Hong S: Neoadjuvant-adjuvant vs

neoadjuvant-only PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors for patients with

resectable NSCLC: An indirect meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open.

7:e2412852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mathew M, Enzler T, Shu CA and Rizvi NA:

Combining chemotherapy with PD-1 blockade in NSCLC. Pharmacol Ther.

186:130–137. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Makharadze T, Gogishvili M, Melkadze T,

Baramidze A, Giorgadze D, Penkov K, Laktionov K, Nemsadze G,

Nechaeva M, Rozhkova I, et al: Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus

chemotherapy alone in advanced NSCLC: 2-year follow-up from the

phase 3 EMPOWER-lung 3 part 2 trial. J Thorac Oncol. 18:755–768.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhu X, Sun L, Song N, He W, Xie B, Hu J,

Zhang J, Yang J, Dai J, Bian D, et al: Safety and effectiveness of

neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor (toripalimab) plus chemotherapy in stage

II–III NSCLC (LungMate 002): An open-label, single-arm, phase 2

trial. BMC Med. 20:4932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Strum S, Vincent M, Gipson M, McArthur E

and Breadner D: Assessment of serum tumor markers CEA, CA-125, and

CA19-9 as adjuncts in non-small cell lung cancer management.

Oncotarget. 15:381–388. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Clevers MR, Kastelijn EA, Peters BJM,

Kelder H and Schramel FMNH: Evaluation of serum biomarker CEA and

Ca-125 as immunotherapy response predictors in metastatic non-small

cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 41:869–876. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S,

Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, Das S, Beckermann KE, Ha L, et al: Fatal

Toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 4:1721–1728. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Naing A, Hajjar J, Gulley JL, Atkins MB,

Ciliberto G, Meric-Bernstam F and Hwu P: Strategies for improving

the management of immune-related adverse events. J Immunother

Cancer. 8:e0017542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Imai H, Kaira K and Kagamu H: Advanced

research on immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Clin Med.

11:53922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|