Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the most common

malignancies in women, ranking fourth in high-income countries and

sixth globally, with ~417,000 new cases diagnosed worldwide in

2020. Its incidence has increased by >130% over the past three

decades, with ~97,370 mortalities reported worldwide in 2020

(1). Risk factors for EC include

obesity, a high glycaemic index diet, early menarche, late

menopause, advanced age, diabetes, the use of oestrogen,

nulliparity, polycystic ovary syndrome and a sedentary lifestyle

(2–4). Prolonged exposure to unopposed

oestrogen, particularly through hormone replacement therapy without

concomitant progestin, increases the risk of developing EC by

4.5-8.0-fold (2). The pathogenesis

of EC is categorised into two primary subtypes in a study by

Bokhman (5). Type I is associated

with oestrogen and offers a more favourable prognosis, whereas type

II represents a high-grade variant with a poorer prognosis,

typically observed in older individuals (aged 55–60 years)

(6).

According to the Human Genome Project, >90% of

the genome is considered to be transcribed (7). Research indicates that only 2% of

these synthesised transcripts can encode proteins, while >75%

consists of non-protein-coding RNAs (8). Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are classified

into two categories based on their size, namely long ncRNAs

(lncRNAs) and small ncRNAs. These categories can be further divided

based on size, cellular localisation or function (9). In particular, lncRNAs and microRNAs

(miRs) serve crucial roles in epigenetic regulation, control of

gene expression levels and the regulation of cellular processes

including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion and the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (9–13).

Previous studies demonstrate an association between the expression

of ncRNA and various pathological conditions, including

neurological, cardiological and cancer-related diseases (12–14).

lncRNAs are generally longer than 200 nucleotides.

They are considered to contribute to carcinogenesis by binding to

transcription factors or repressors, acting as signalling molecules

to activate or inhibit the expression of genes and engaging with

protein complexes and cofactors (13). Moreover, lncRNAs also serve a role

in post-transcriptional regulation by participating in mRNA

processing. Additionally, lncRNAs function as sponges, preventing

miR from binding to their target mRNA (15).

The study by Rinn et al (14) was the first to report and

characterize Hox antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) as a lncRNA.

Studies demonstrate that HOTAIR helps regulate gene activity, which

has led to investigations on its potential connection to various

types of cancer, including lung, gastric, glioma, pancreatic,

cervical (16–20) and EC (21,22).

The expression of HOTAIR increases in patients with EC, and its

elevation is associated with advanced disease, metastasis and drug

resistance (16,17,22).

However, the molecular effects of HOTAIR in EC and the potential

clinical application of its serum levels have not been fully

elucidated.

miRs are small ncRNA sequences, ~22 nucleotides in

length, involved in regulating processes such as development, cell

differentiation, apoptosis and proliferation. Their primary

function is gene silencing (23).

miRs can act as either tumour suppressors or oncogenes under

specific conditions (24). While

oncogenic miRs enhance the tumour cell phenotype, tumour suppressor

miRs diminish it (25). The

abundant presence of miRs in faeces, sputum, pleural effusion and

urine suggests that alterations in miR expression levels are

readily detectable.

Previous studies indicate that miR-646 is linked to

various types of cancer, including lung (26), laryngeal (27), clear cell carcinoma (28), retinoblastoma (29) and osteosarcoma (30), with a notable role in

gastrointestinal (31) and

gynaecological tumours (32). It is

hypothesized to function as a tumour suppressor in these

malignancies, and in EC, it primarily reduces tumorigenic potential

through the downregulation of nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) (32,33).

In vitro studies by Zhou et al (33) demonstrates that HOTAIR increases

NPM1 levels by suppressing the expression of miR-646, which

promotes cancer cell proliferation, invasion and migration.

At present, there is not a reliable non-invasive

biomarker that is routinely used for the diagnosis or monitoring of

EC. HOTAIR is a potential biomarker candidate due to its

overexpression and association with advanced stages of the disease

(33). Additionally, miR-646 may

also serve as a detectable marker in body fluids (34). Experimental evidence from Zhou et

al (33) suggests a possible

regulatory interaction between HOTAIR and miR-646; however, this

association is yet to be confirmed in clinical serum samples.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the serum

expression levels of HOTAIR and miR-646 in patients with EC and

investigated their potential as non-invasive diagnostic or

prognostic biomarkers.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study population consisted of women aged ≥18

years with histologically confirmed EC, diagnosed by endometrial

biopsy and managed surgically. All participants provided written

informed consent prior to inclusion. Patients with biopsy-proven EC

of any histopathological subtype who underwent hysterectomy with

surgical staging and subsequent histopathological evaluation of the

surgical specimens were included. The control group included women

who attended the general gynaecology outpatient clinic for

non-malignant gynaecological conditions and who had no history of

malignancy. Patients were excluded if they declined to provide

informed consent, were medically inoperable, refused surgical

treatment, had a final pathology not confirming EC, had synchronous

or other primary malignancies, had recurrent disease, or had

received prior oncologic treatments such as chemotherapy,

radiotherapy or immunotherapy. The present study examined the

association between HOTAIR and miR-646 gene expression levels and

the development of EC. Additionally, the association between

prognostic factors of EC, such as grade and clinical T stage, and

the expression of HOTAIR and miR-646 was investigated. In total, 71

patients that were admitted to the Department of Obstetrics,

Gynaecology-Oncology Division, Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul

University (Istanbul, Turkey) and diagnosed with EC based on biopsy

results, were included in the present study. Additionally, 62

healthy women who sought services at the Department of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology, Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, for

routine gynaecological examination or benign conditions were

included in the control group. Patients and healthy control

individuals were enrolled in the present study between August 2021

and March 2023. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Istanbul

University (Istanbul, Turkey; approval no. 272576; approval date,

01.07.2021). Sample collection and experimental analyses were

completed by June 2023. Blood samples were collected after both the

patients and control individuals were informed verbally and in

writing.

Patients and controls were matched based on age,

body mass index (BMI) and smoking status. An individual was classed

as a smoker if they had a minimum of 10 packs/year. An individual

was classed as a non-smoker if they had either quit smoking more

than a year before the present study or had never smoked. All

participants in both groups were female. The median ages were 57

years (range, 29–81 years) in the patient group and 54 years

(range, 34–77 years) in the control group. The mean age ± standard

deviation (SD) was 57.7±11.0 years for the patient group and

54.8±10.1 years for the control group. Tumour stage and grade were

determined according to surgical staging. In the present study, EC

was classified as low grade [International Federation of Gynecology

and Obstetrics (FIGO) grades 1–2 endometrioid)] and high grade

(FIGO grade 3 endometrioid and non-endometrioid types), which was

consistent with accepted dichotomy in the literature (35). Previous studies define high-grade EC

to include grade 3 endometrioid tumours, serous, clear cell,

undifferentiated and carcinosarcoma subtypes (6,36,37).

These tumours are characterized by more aggressive biological

behaviour, a poorer prognosis compared with low-grade (FIGO grade

1–2 endometrioid) endometrial carcinomas and as high risk by major

clinical guidelines, including the European Society of

Gynaecological Oncology, the European Society for Radiotherapy and

Oncology, and the European Society of Pathology guidelines for EC

(2021) (38) and the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in

Oncology: Uterine Neoplasms (version 3.2025) (39). Stages IA and IB were regarded as

early stages, while stages II–IV were considered advanced stages.

Additionally, cancer antigen 125 (CA125) levels, menopausal status,

hypertension, diabetes mellitus, recurrence, lymph node

involvement, disease-free survival, overall survival and

cancer-related mortality were evaluated.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

For RNA extraction, venous blood samples were

allowed to clot for 30 min, and were then centrifuged at 1,500 × g

for 10 min at 4°C. The separated serum samples were stored at −80°C

until further analysis. RNA isolation was carried out using the

miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Advanced kit (cat. no. 217204; Qiagen GmbH).

The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA samples were

evaluated using an Eon Biotek instrument. Following measurement,

RNA samples were stored at −80°C. For miRNA expression level

analysis, reverse transcription was carried out using the miRCURY

LNA RT kit (cat. no. 339340; Qiagen GmbH) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The reaction was carried out at 42°C for 1

h, followed by enzyme inactivation at 95°C for 5 min. For lncRNA

expression level analysis, cDNA synthesis was conducted using the

RT2 PreAMP cDNA Synthesis kit (cat. no. 330451; Qiagen

GmbH) following the manufacturer's protocol. The reverse

transcription step was carried out at 37°C for 1 h, followed by

enzyme inactivation at 95°C for 5 min. RT-qPCR was carried out on a

Rotor-Gene Q Real-Time PCR System (Qiagen GmbH) using the miRCURY

LNA SYBR Green PCR kit (cat. no. 339345; Qiagen GmbH) for the

detection of hsa-miR-646, and the RT2 SYBR Green ROX

FAST Mastermix kit (cat. no. 330620; Qiagen GmbH) for the analysis

of lncRNA HOTAIR expression levels. PCR amplification was carried

out according to the manufacturer's protocols. For lncRNA, initial

denaturation was carried out at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 1 min. For miR, initial

denaturation was carried out at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 56°C for 1 min.

The primers used in the present study were obtained

from Qiagen GmbH. They included the following: RT2 qPCR

Assay for GAPDH (cat. no. PPH00150F), RT2 lncRNA qPCR

Assay for HOTAIR (cat. no. LPH07360A), miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR Assay

for hsa-miR-646 (cat. no. YP00204546) and miRCURY LNA™ miRNA PCR

Assay for hsa-U6 (cat. no. YP02119464). The exact sequences of

these primers are proprietary and not publicly available from the

manufacturer. Gene expression levels were quantified using the

2−ΔΔCq method (40).

Relative expression levels were normalized to GAPDH for lncRNA and

to U6 for miR, in accordance with previously published studies

(22,27,41–43).

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp.) was used for data

analysis. The distribution of data in the present study was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables with normal

distribution were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by the

Bonferroni post hoc test, while non-normally distributed variables

were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. In the present data,

‘age’ had a normal distribution, whereas ‘BMI’ did not follow a

normal distribution. The Chi-square test was used to analyse the

association between qualitative data. Spearman's correlation test

was used to investigate the association between two datasets.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was carried

out to determine whether an independent variable could distinguish

between cases of EC and healthy controls. The ROC curve was used to

identify the optimal predictive value and to calculate the

sensitivity and specificity of the predictive value. The

Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare survival between groups.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

There were no significant differences between the

control group and patients with EC in terms of age, BMI, smoking,

hypertension or diabetes mellitus status. Among the patients, 46

cases (64.8%) had low-grade tumours (grades 1 and 2), while 25

cases (35.2%) had high-grade tumours (grade 3), of which 2 cases

(8%) were of non-endometrioid histology (1 case had serous

carcinoma and another case had clear cell carcinoma). Early-stage

disease (stages IA and B) was present in 84.5% of the patients,

whereas 15.5% had advanced-stage disease. Tumour recurrence was

observed in 14.1% of cases, and lymph node involvement was

identified in 87.3% of patients. Mean disease-free survival and

overall survival were 30.06±10.42 and 32.18±7.98 months,

respectively, while cancer-related mortality was 10.2% (Table I).

| Table I.Comparison of demographic and

clinical characteristics between the control and patient

groups. |

Table I.

Comparison of demographic and

clinical characteristics between the control and patient

groups.

| Parameter | Healthy control

individuals (n=62) | Patients with

endometrial cancer (n=71) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years (mean ±

SD) | 54.77±10.09 | 57.64±11.03 | 0.118 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 31.20±6.37 | 32.24±8.36 | 0.261 |

| CA125, median

(min-max) | - | 13.0

(5.0-745.0) |

|

| Smoking status, N

(%) |

|

| 0.249 |

|

Non-smoker | 39 (63.9) | 52 (73.2) |

|

|

Smoker | 22 (36.1) | 19 (26.8) |

|

| Menopause status, N

(%) |

|

| - |

|

Premenopausal | - | 24 (33.8) |

|

|

Postmenopausal | - | 47 (66.2) |

|

| Tumour grade, N

(%) |

|

| - |

| Low

grade (grades 1 and 2) | - | 46 (64.8) |

|

| High

grade (grade 3 endometrioid and non-endometrioid histology

types) | - | 25 (35.2) |

|

| Stage, N (%) |

|

| - |

| Early

stage (IA and B) | - | 60 (84.5) |

|

|

Advanced stage (II–IV) | - | 11 (15.5) |

|

| Recurrence, N

(%) |

|

| - |

| No | - | 61 (85.9) |

|

|

Yes | - | 10 (14.1) |

|

| Lymph node

involvement, N (%) |

|

| - |

|

Yes | - | 62 (87.3) |

|

| No | - | 9 (12.7) |

|

| Hypertension, N

(%) |

|

| 0.070 |

|

Yes | 13 (21.0) | 25 (35.2) |

|

| No | 49 (79.0) | 46 (64.8) |

|

| Diabetes mellitus,

N (%) |

|

| 0.150 |

|

Yes | 8 (12.9) | 16 (22.5) |

|

| No | 54 (87.1) | 55 (77.5) |

|

| Disease-free

survival, months (mean ± SD) | - | 30.06±10.42 | - |

| Overall survival,

months (mean ± SD) | - | 32.18±7.98 | - |

| Cancer-related

mortality, N (%) |

|

| - |

| No | - | 53 (89.9) |

|

|

Yes | - | 6 (10.2) |

|

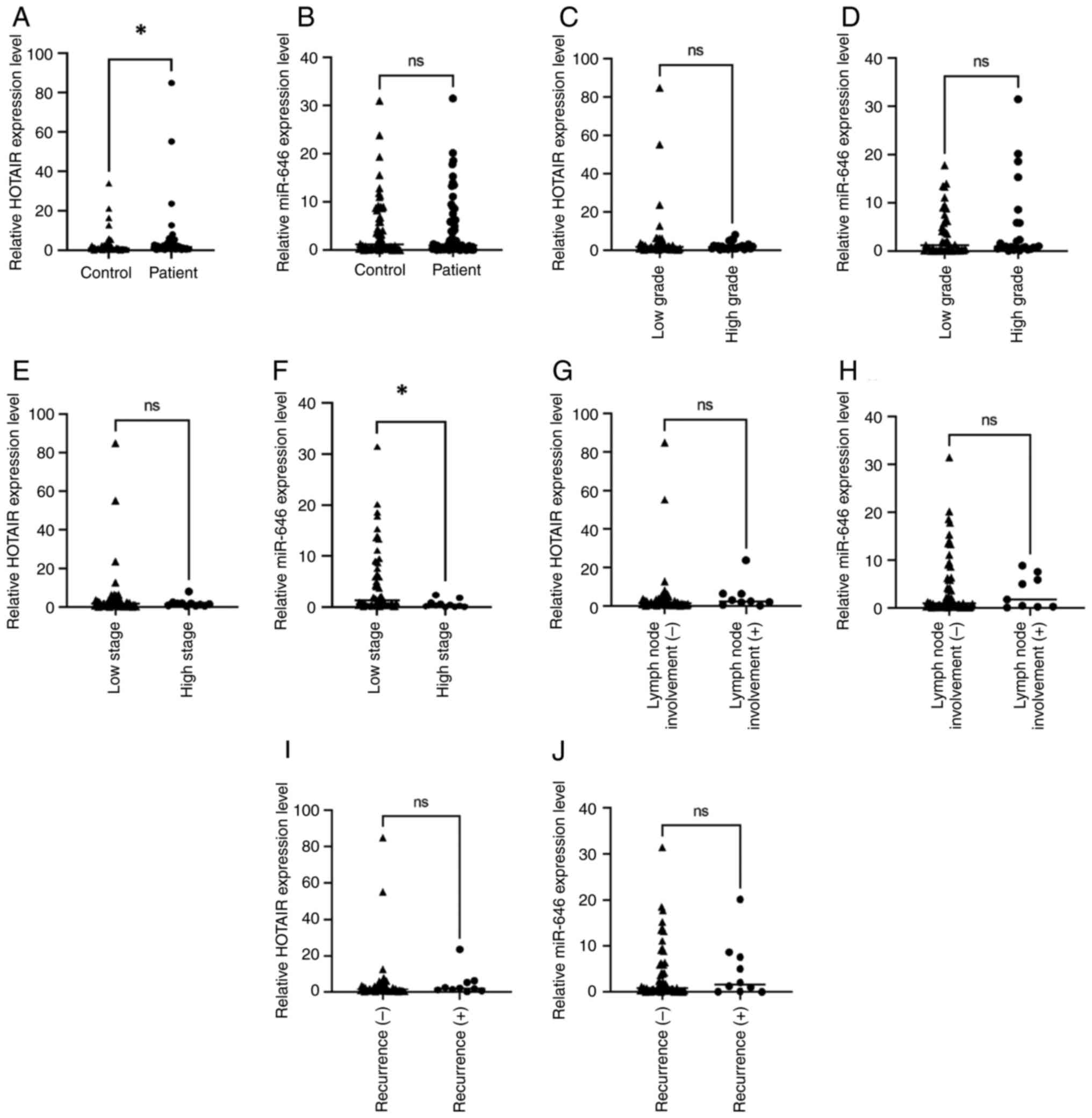

The expression of HOTAIR was significantly increased

in patients with EC compared with the control group (P=0.020).

However, the expression of miR-646 did not differ significantly

between the patient and the control groups (P=0.579). Additionally,

no significant differences in HOTAIR or miR-646 expression levels

were revealed between low- and high-grade tumours (P=0.230 and

P=0.377, respectively). The HOTAIR expression levels did not vary

significantly between low and high clinical tumour stages

(P=0.466). However, the miR-646 expression level was significantly

reduced in the high tumour stage group compared with the low tumour

stage group (P=0.045). Recurrence status and lymph node involvement

showed no significant association with the expression levels of

HOTAIR (P=0.321 and P=0.192, respectively) or miR-646 (P=0.741 and

P=0.942, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Spearman's correlation analysis did not demonstrate a significant

association between serum miR-646 and HOTAIR expression levels

(Table II). Furthermore, there

were no significant correlations between the miR-646 or HOTAIR

expression levels and CA125 concentrations (Table III).

| Table II.Spearman correlation between HOTAIR

and miR-646. |

Table II.

Spearman correlation between HOTAIR

and miR-646.

| Parameter |

| r-value | P-value |

|---|

| HOTAIR | miR-646 | 0.105 | 0.212 |

| Table III.Spearman correlation of HOTAIR and

miR-646 with CA125. |

Table III.

Spearman correlation of HOTAIR and

miR-646 with CA125.

|

| Correlation with

CA125 |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Parameter | r-value | P-value |

|---|

| HOTAIR | 0.091 | 0.288 |

| miR-646 | 0.053 | 0.385 |

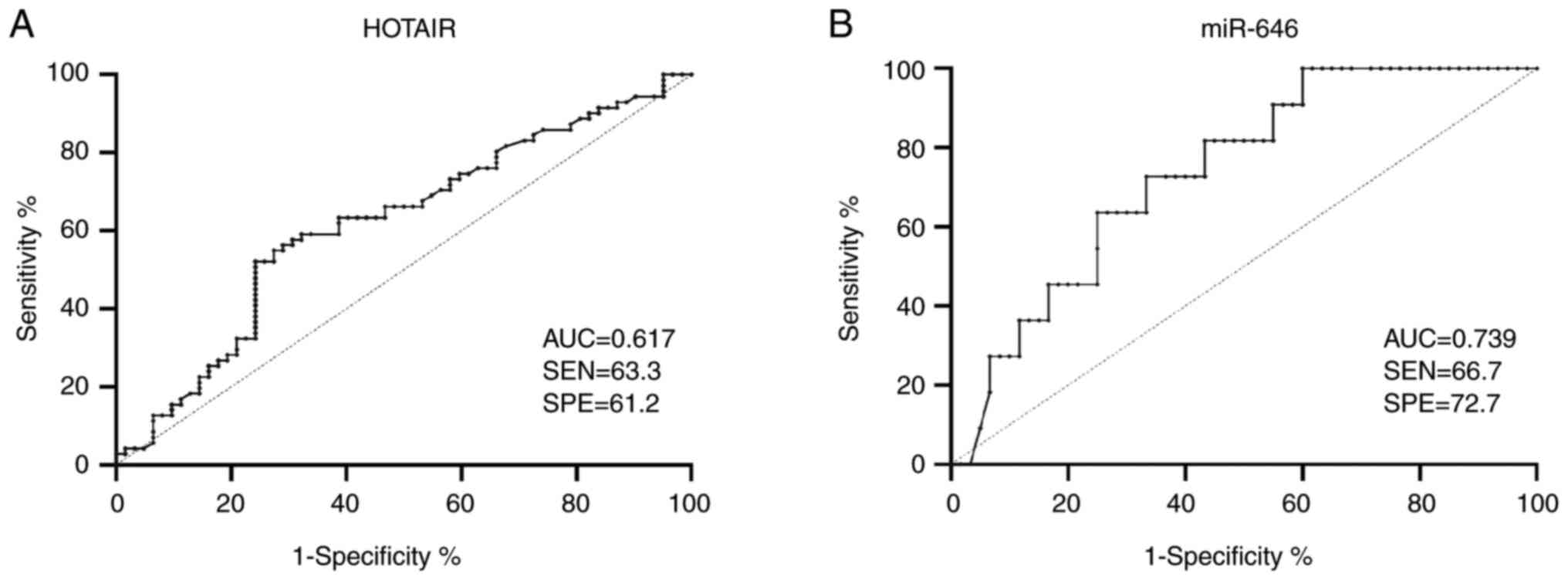

ROC analysis was carried out to investigate the

optimal cut-off values for serum HOTAIR and miR-646 expression

levels to distinguish between patients with EC and the healthy

controls. For HOTAIR, an expression level threshold of 1.08 was

revealed to differentiate between patients with EC and healthy

controls, with a sensitivity of 63.3% and a specificity of 61.2%.

Therefore, patients were classified as being HOTAIR-positive (with

a value of ≥1.08) or HOTAIR-negative (with a value of <1.08).

For miR-646, an expression level cut-off value of 0.655 was

demonstrated to distinguish between patients with advanced-stage

and early-stage EC, with a sensitivity of 66.7% and a specificity

of 72.7%. Therefore, patients were categorized as being

miR-646-positive (≥0.655) or miR-646-negative (<0.655). These

classification criteria are presented in Fig. 2.

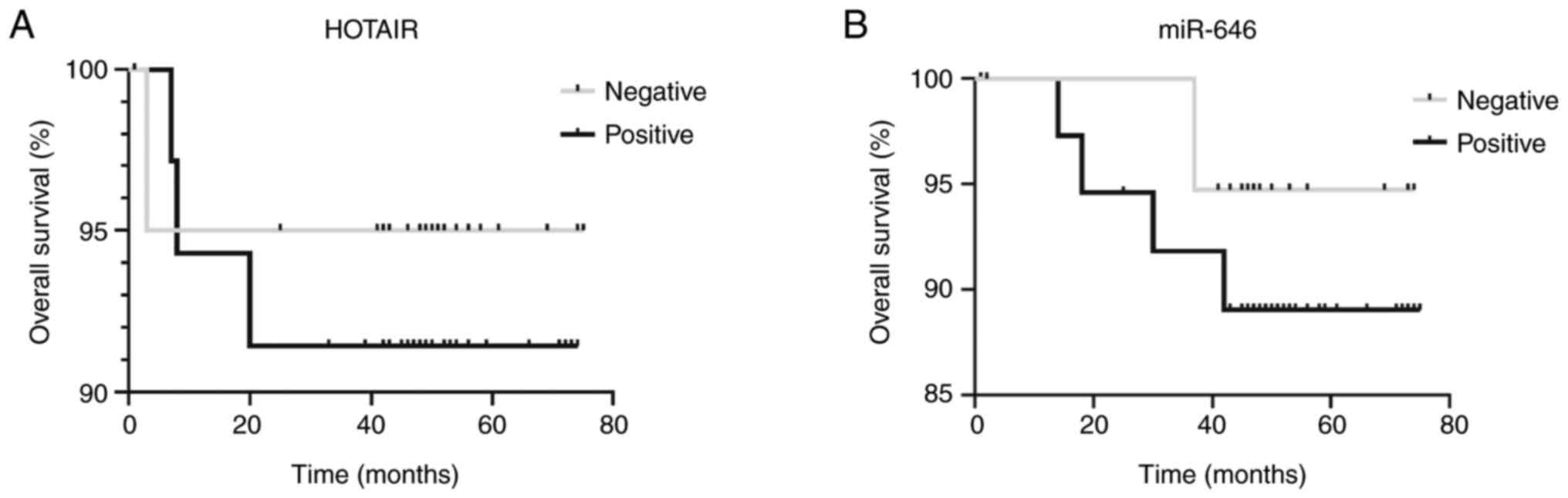

No statistically significant differences in overall

survival (in months) were observed between the HOTAIR-positive and

-negative groups or between the miR-646-positive and -negative

groups (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Although the incidence rate of EC has increased by

>130% over the past three decades, with >417,000 new cases

and ~97,370 mortalities reported worldwide in 2020 (1), reliable non-invasive diagnostic

biomarkers are still unavailable. Advancing diagnostic methods and

therapeutic strategies depends on elucidating the molecular

pathways involved in this disease. ncRNAs, including lncRNAs and

miRs, have garnered attention as potential biomarkers across

various types of cancer such as breast, gastric and gynaecological

cancer (29–32). While numerous studies have

investigated the expression of HOTAIR and miR-646 in EC tissue

samples, information regarding their circulating levels in serum is

still insufficient (33,34).

ncRNA species, such as miRs, lncRNAs and circular

RNAs (circRNAs), serve crucial roles in the positive and negative

regulation of the expression of genes. Over the past two decades,

numerous studies highlight the involvement of ncRNAs in various

aspects of cell biology, particularly in cancer development,

progression and drug resistance (43–48).

These molecules participate in virtually all cellular processes and

have fundamental roles at every stage of tumorigenesis. Altered

expression levels of mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and miRs are reported

in numerous types of cancer, such as triple-negative and oestrogen

receptor-positive breast cancer, serving as potential biomarkers

for diagnosis and therapeutic targets (43,47–50).

Furthermore, ncRNAs have been studied as promising biomarkers for

early detection and prognostic evaluation in various malignancies,

including lung (26), gastric

(31), breast (43), prostate (51), liver (52), colorectal (53), bladder (54), pancreatic (55) and haematological disorders (56). This evidence suggests that

circulating lncRNAs in peripheral blood may potentially serve as

non-invasive biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and monitoring.

The expression of miR is tissue-specific and serves

a key role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Their stability in

circulation and cancer-specific expression patterns have led to

their investigation as promising non-invasive biomarkers in various

malignancies including breast, lung, colorectal and prostate cancer

(57–61). Although the majority of studies

focus on other types of cancer, such as ovarian, breast and

colorectal cancer (59–61), evidence suggests that specific miRs

and lncRNAs exhibit altered expression profiles in EC tissues

compared with normal endometrium, indicating potential roles in

diagnosis and prognosis (62).

HOTAIR is an important prognostic biomarker that is

overexpressed in various types of cancer including breast, ovarian,

colorectal and lung cancer (16–20).

Its increased expression level is linked to higher levels of

suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12), a gene involved in epigenetic

regulation (63). This suggests

that HOTAIR may serve a role in modifying chromatin structure in

tumours (64,65). HOTAIR may also mediate genome-wide

epigenetic changes by recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes such

as the polycomb repressive complex 2 (containing enhancer of zeste

homolog 2, SUZ12 and embryonic ectoderm development), which

catalyses histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation, and the lysine

specific demethylase 1/corepressor for element-1-silencing

transcription factor/RE1-silencing transcription factor complex,

which demethylates the active histone hallmark histone H3 lysine 4

trimethylation (63,66). This mechanism may explain its

overexpression in breast, colorectal, hepatocellular,

gastrointestinal and pancreatic tumours (66). Located within the HOXC gene cluster,

HOTAIR enhances tumour invasiveness and metastasis (63). Furthermore, Bhan et al

(67) reports that the expression

of HOTAIR is transcriptionally regulated by oestradiol. HOTAIR is

similarly upregulated in EC in tumour tissues compared with normal

endometrium. The expression of HOTAIR is associated with higher

tumour grades, lymph node metastasis and poor clinical prognosis

(21,22,68).

Functional studies demonstrate that downregulation of HOTAIR can

inhibit cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and in

vivo (68,69). Furthermore, HOTAIR contributes to

chemoresistance by promoting cisplatin resistance by regulating

autophagy pathways in EC cells (70).

In the present study, serum HOTAIR expression levels

were significantly increased in patients with EC compared with the

control group. Although this difference was statistically

significant, its diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity)

was modest, limiting its immediate clinical applicability. In

contrast to previous studies on tumour tissue (17,22,33,68–70)

the results of the present study demonstrated no correlation

between serum HOTAIR expression levels and disease stage, tumour

grade or lymph node metastasis. Additionally, survival analysis

revealed no significant association with patient outcomes. These

discrepancies may be attributed to differences in the patient

populations, or they may indicate that tissue-level associations

may not be fully captured in serum-based assessments.

miR-646 is associated with numerous types of cancer

including non-small cell lung, clear cell renal, retinoblastoma,

laryngeal squamous cell, colorectal, gastric and breast cancer and

is generally downregulated in malignancies, where it contributes to

tumour growth, metastasis and invasion (25–31).

By contrast, its upregulation suppresses these processes. Previous

studies by Liu et al (32)

and Zhou et al (33)

demonstrate that miR-646 inhibits the expression of NPM1 and exerts

tumour-suppressive effects in EC cell lines including HEC-1A and

Ishikawa. The study by Zhou et al (33) demonstrates that miR-646 expression

levels are reduced in both EC tissues and cancer cell lines

compared with normal endometrial tissues and cells, respectively.

Furthermore, HOTAIR reduces miR-646 expression levels in

vitro, and a positive association between HOTAIR and NPM1,

alongside a negative association between NPM1 and miR-646, is

observed in EC tissues (32,33).

The results of the present study found no

statistically significant difference in serum miR-646 expression

levels between patients with EC and healthy controls. Additionally,

miR-646 expression levels were not demonstrated to be associated

with tumour grade, recurrence, lymph node metastasis or overall

survival. However, patients with advanced-stage EC exhibited

significantly lower miR-646 levels compared with those with

early-stage EC. This suggested a possible association between

miR-646 downregulation and disease progression, which may be

potentially mediated through the NPM1 pathway. However, the

expression of NPM1 was not assessed in the present

investigation.

The associations between serum levels of HOTAIR and

miR-646 with CA-125 were further investigated; however, no

significant associations were revealed. ROC curve analysis of

HOTAIR revealed an area under the curve of 0.617, with an optimal

threshold value of 1.08, sensitivity of 63.3% and specificity of

61.2%. This suggested a modest diagnostic accuracy. Although these

values indicated a modest diagnostic accuracy, they fall below the

commonly accepted criteria for clinical applicability (AUC

>0.80; sensitivity and specificity >80%) (71), which suggested that serum HOTAIR

alone was insufficient for diagnostic use; however, it may serve as

a potential adjunct biomarker. Future research focusing on exosomal

HOTAIR expression levels may enhance diagnostic performance.

Regarding miR-646, ROC analysis differentiating

early from advanced stages of EC demonstrated an optimal cut-off

value of 0.655, with sensitivity and specificity values of 66.7 and

72.7%, respectively. Although these metrics were below the levels

required for a clinically useful diagnostic test, they suggested

that miR-646 may have a potential utility in disease staging,

particularly if exosomal miR-646 expression levels are investigated

in future studies. Although there was not a significant association

between HOTAIR or miR-646 levels and tumour grade, lymph node

metastasis or recurrence status, these findings should be

interpreted cautiously. It is possible that serum-based assessments

do not accurately reflect the tumour microenvironment, or that the

small sample size of the present study limited the ability of the

present study to detect these associations. The novelty of the

present study was the evaluation of serum-based expression levels

of HOTAIR and miR-646 as potential non-invasive biomarkers in EC,

which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously

reported in clinical patient samples.

The present study had several limitations. Firstly,

in the present study, the expression of HOTAIR or miR-646 in

exosomes was not assessed, which may provide a more accurate

reflection of tumour-derived ncRNAs. Secondly, the small number of

patients with lymph node metastasis and recurrence limited the

possibility of conducting subgroup analyses. Thirdly, the absence

of associations between miR-646 and certain clinicopathological

features may be due to the characteristics of the cohort used in

the present study or the lack of exosomal data. Finally, the use of

GAPDH and U6 as endogenous controls for normalization may represent

another limitation of the present study. Although these reference

genes are used in serum-based analyses of lncRNA and miR to ensure

comparability with previous studies, their stability in circulation

is not absolute and may introduce technical variability. Future

studies should incorporate spike-in controls, such as synthetic

cel-miR-39 or Universal spike-in oligonucleotides, for both HOTAIR

and miR-646 to monitor RNA extraction and reverse transcription

efficiency (72), and use stable

endogenous RNAs (such as U6 for miR-646 (73) and GAPDH or 18S ribosomal RNA for

HOTAIR (74) to improve

normalisation and enhance the reproducibility of results. In

conclusion, the results of the present study reinforced the

relevance of HOTAIR and miR-646 in EC. Serum HOTAIR may contribute

to diagnosis, while serum miR-646 may reflect disease stage.

However, both biomarkers require validation in larger, more diverse

patient cohorts and studies incorporating exosomal analysis in

order to clarify their clinical applicability in the diagnosis,

monitoring and prognosis of EC. In addition to their potential use

as biomarkers, the findings of the present study suggested that

both HOTAIR and miR-646 may serve as targets for new treatment

strategies in EC. The increased expression of HOTAIR could possibly

be reduced by drugs that block its function, and the decreased

expression of miR-646 in advanced stages may possibly be restored

using miR-646 mimics. The results of the present study may be

useful not only for diagnosis and prognosis but also for the

development of novel therapies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Istanbul University

Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (BAP) (grant no.

TYL-2021-38002).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RH, HK, YM, HS, ST, CK and AFA conceived and

designed the experiments. RH, HK, YM, HS, ST, CK and AFA confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. RH, HK, YM, HS, ST, CK and

AFA performed the experiments, including literature database

searching where applicable, conducted data analysis, prepared

figures and tables, and contributed to the drafting of the

manuscript and its critical revision for important intellectual

content. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University

(approval date, 01.07.2021; approval no. 272576; Istanbul, Turkey).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and

the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

ORCID IDs: Rızki Harismunandar, https://orcid.org/0009-0004-9966-9595;

Hande Karpuzoğlu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9603-5838; Yağmur

Minareci, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1420-9318; Hamdullah

Sözen, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1894-1688; Samet Topuz,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9069-0185; Canan

Küçükgergin, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1797-5889; A. Fatih Aydın,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3336-4332.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Baker-Rand H and Kitson SJ: Recent

advances in endometrial cancer prevention, early diagnosis and

treatment. Cancers (Basel). 16:10282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zaino RJ: Introduction to endometrial

cancer. Molecular Pathology of Gynecologic Cancer. Giordano A,

Bovicelli A and Kurman RJ: Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: pp. 51–72.

2007, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Patni R: Current concepts in endometrial

cancer. Endometrial Carcinoma: Evolution and Overview. Patni R:

Springer; Singapore: pp. 1–10. 2017

|

|

4

|

Pokharna S: Epidemiology and prevention of

endometrial carcinoma. Current Concepts in Endometrial Cancer.

Patni R: Springer; Singapore: pp. 11–18. 2017, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Bokhman JV: Two pathogenetic types of

endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 15:10–17. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wilczyński M, Danielska J and Wilczyński

JR: An update of the classical Bokhman's dualistic model of

endometrial cancer. Menopause Rev. 15:63–68. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Collins FS and Mansoura MK: The human

genome project. Cancer. 91:221–225. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jarroux J, Morillon A and Pinskaya M:

History, discovery, and classification of lncRNAs. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1008:1–46. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wu M, Fu P, Qu L, Liu J and Lin A: Long

noncoding RNAs: New critical regulators in cancer immunity. Front

Oncol. 10:5509872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mattick JS and Makunin IV: Non-coding RNA.

Hum Mol Genet. 15(Spec No 1): R17–R29. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bhattacharjee R, Prabhakar N, Kumar L,

Bhattacharjee A, Kar S, Malik S, Kumar D, Ruokolainen J, Negi A,

Jha NK and Kesari KK: Crosstalk between long noncoding RNA and

microRNA in cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 46:885–908. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Slack FJ and Chinnaiyan AM: The role of

non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell. 179:1033–1055. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mercer TR, Dinger ME and Mattick JS: Long

non-coding RNAs: Insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet.

10:155–159. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL,

Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E and

Chang HY: Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin

domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 129:1311–1323.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang X, Wang W, Zhu W, Dong J, Cheng Y,

Yin Z and Shen F: Mechanisms and functions of long non-coding RNAs

at multiple regulatory levels. Int J Mol Sci. 20:55732019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hajjari M and Salavaty A: HOTAIR: An

oncogenic long non-coding RNA in different cancers. Cancer Biol

Med. 12:1–9. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rajagopal T, Talluri S, Akshaya RL and

Dunna NR: HOTAIR lncRNA: A novel oncogenic propellant in human

cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 503:1–18. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Qu X, Alsager S, Zhuo Y and Shan B: HOX

transcript antisense RNA (HOTAIR) in cancer. Cancer Lett.

454:90–97. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu Y, Zhang L, Wang Y, Li H, Ren X, Wei F,

Yu W, Wang X, Zhang L, Yu J and Hao X: Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR

involvement in cancer. Tumour Biol. 35:9531–9538. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mozdarani H, Ezzatizadeh V and Rahbar

Parvaneh R: The emerging role of the long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in

breast cancer development and treatment. J Transl Med. 18:1522020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Vallone C, Rigon G, Gulia C, Baffa A,

Votino R, Morosetti G, Zaami S, Briganti V, Catania F, Gaffi M, et

al: Coding RNAs and endometrial cancer. Genes (Basel). 9:1872018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

He X, Bao W, Li X, Chen Z, Che Q, Wang H

and Wan XP: The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR is upregulated in

endometrial carcinoma and correlates with poor prognosis. Int J Mol

Med. 33:325–332. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Romano G, Veneziano D, Acunzo M and Croce

C: Small non-coding RNA and cancer. Carcinogenesis. 38:485–491.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen Y, Fu LL, Wen X, Liu B, Huang J, Wang

JH and Wei YQ: Oncogenic and tumor suppressive roles of microRNAs

in apoptosis and autophagy. Apoptosis. 19:1177–1189. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Peng Y and Croce CM: The role of microRNAs

in human cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 1:150042016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pan Y, Chen Y, Ma D, Ji Z, Cao F, Chen Z,

Ning Y and Bai C: miR-646 is a key negative regulator of EGFR

pathway in lung cancer. Exp Lung Res. 42:286–295. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zang Y, Li J, Wan B and Tai Y: circRNA

circ-CCND1 promotes the proliferation of laryngeal squamous cell

carcinoma via elevating CCND1 expression by interacting with HuR

and miR-646. J Cell Mol Med. 24:2423–2433. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li W, Liu M, Feng Y, Xu YF, Huang YF, Che

JP, Wang GC, Yao XD and Zheng JH: Downregulated miR-646 in clear

cell renal carcinoma correlated with tumour metastasis by targeting

the nin one binding protein (NOB1). Br J Cancer. 111:1188–1200.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhang L, Wu J, Li Y, Jiang Y, Wang L, Chen

Y, Lv Y, Zou Y and Ding X: Circ_0000527 promotes the progression of

retinoblastoma by regulating miR-646/LRP6 axis. Cancer Cell Int.

20:3012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yang L, Liu G, Xiao S, Wang L, Liu X, Tan

Q and Li Z: Long noncoding MT1JP enhanced the inhibitory effects of

miR-646 on FGF2 in osteosarcoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm.

35:371–376. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang P, Tang WM, Zhang H, Li YQ, Peng Y,

Wang J, Liu GN, Huang XT, Zhao JJ, Li G, et al: miR-646 inhibits

cell proliferation and EMT-induced metastasis by targeting FOXK1 in

gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 117:525–534. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu Y, Chen S, Zong ZH, Guan X and Zhao Y:

CircRNA WHSC1 targets the miR-646/NPM1 pathway to promote the

development of endometrial cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 24:6898–6907.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhou YX, Wang C, Mao LW, Wang YL, Xia LQ,

Zhao W, Shen J and Chen J: Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR mediates the

estrogen-induced metastasis of endometrial cancer cells via the

miR-646/NPM1 axis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 314:C690–C701. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang WT, Zhao YN, Yan JX, Weng MY, Wang Y,

Chen YQ and Hong SJ: Differentially expressed microRNAs in the

serum of cervical squamous cell carcinoma patients before and after

surgery. J Hematol Oncol. 7:62014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Murali R, Davidson B, Fadare O, Carlson

JA, Crum CP, Gilks CB, Irving JA, Malpica A, Matias-Guiu X,

McCluggage WG, et al: High-grade endometrial carcinomas:

Morphologic and immunohistochemical features, diagnostic challenges

and recommendations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 38:40–63. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhang C and Zheng W: High-grade

endometrial carcinomas: Morphologic spectrum and molecular

classification. Semin Diagn Pathol. 39:176–186. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Oliva E and Soslow RA: High-grade

endometrial carcinomas. Surg Pathol Clin. 4:199–241. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, Cibula

D, Mirza MR, Marnitz S, Lederman S, Bosse T, Chargari C, Fagotti A,

et al: ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients

with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 31:12–39. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in

Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), . Uterine Neoplasms. Version 3.2025.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network; Plymouth Meeting, PA:

2025

|

|

40

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mohamad N, Khedr AMB, Shaker OG and Hassan

M: Expression of long noncoding RNA, HOTAIR, and MicroRNA-205 and

their relation to transforming growth factor β1 in patients with

alopecia Areata. Skin Appendage Disord. 9:111–120. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang B, Sun Q, Ye W, Li L and Jin P: Long

non-coding RNA CDKN2B-AS1 enhances LPS-induced apoptotic and

inflammatory damages in human lung epithelial cells via regulating

the miR-140-5p/TGFBR2/Smad3 signal network. BMC Pulm Med.

21:2002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

İlhan B, Kuraş S, Kılıç B, Tilgen

Yasasever C, Oğuz Soydinç H, Alsaadoni H, Öztan G, Adamnejad

Ghafour A, Ucuncu M, Kunduz E and Bademler S: Exploratory analysis

of circulating serum miR-197-3p, miR-1236, and miR-1271 expression

in early breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 26:89442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Melton C, Reuter JA, Spacek DV and Snyder

M: Recurrent somatic mutations in regulatory regions of human

cancer genomes. Nat Genet. 47:710–716. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Egranova SD, Hua Q, Lina C and Yanga L:

lncRNAs as tumor cell intrinsic factors that affect cancer

immunotherapy. RNA Biol. 17:1625–1627. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bhan A, Soleimani M and Mandal SS: Long

noncoding RNA and cancer: A new paradigm. Cancer Res. 77:3965–3981.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kansara S, Pandey V, Lobie PE, Sethi G,

Garg M and Pandey AK: Mechanistic involvement of long noncoding

RNAs in oncotherapeutics resistance in triple-negative breast

cancer. Cells. 9:15112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Basak P, Chatterjee S, Bhat V, Su A, Jin

H, Lee-Wing V, Liu Q, Hu P, Murphy LC and Raouf A: Long non-coding

RNA H19 acts as an estrogen receptor modulator that is required for

endocrine therapy resistance in ER+ breast cancer cells. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 51:1518–1532. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Anastasiadou E, Jacob LS and Slack FJ:

Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:5–18. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Whitfield ML, George LK, Grant GD and

Perou CM: Common markers of proliferation. Nat Rev Cancer.

6:99–106. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ding L, Wang R, Shen D, Cheng S, Wang H,

Lu Z, Zheng Q, Wang L, Xia L and Li G: Role of noncoding RNA in

drug resistance of prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 12:5902021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chen N, Li Y and Li X: Dynamic role of

long noncoding RNA in liver diseases: Pathogenesis and diagnostic

aspects. Clin Exp Med. 25:1602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lin Y, Zhao W, Pu R, Lv Z, Xie H, Li Y and

Zhang Z: Long non coding RNAs as diagnostic and prognostic

biomarkers for colorectal cancer (Review). Oncol Lett. 28:4862024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li S, Zhao Y and Chen X: Microarray

expression profile analysis of circular RNAs and their potential

regulatory role in bladder carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 45:239–253. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kawai M, Fukuda A, Otomo R, Obata S,

Minaga K, Asada M, Umemura A, Uenoyama Y, Hieda N, Morita T, et al:

Early detection of pancreatic cancer by comprehensive serum miRNA

sequencing with automated machine learning. Br J Cancer.

131:1158–1168. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wong NK, Huang CL, Islam R and Yip SP:

Long non-coding RNAs in hematological malignancies: Translating

basic techniques into diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. J

Hematol Oncol. 11:1312018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ludwig N, Leidinger P, Becker K, Backes C,

Fehlmann T, Pallasch C, Rheinheimer S, Meder B, Stähler C, Meese E

and Keller A: Distribution of miRNA expression across human

tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:3865–3877. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A,

Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M,

et al: A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA

library sequencing. Cell. 129:1401–1414. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Valihrach L, Androvic P and Kubista M:

Circulating miRNA analysis for cancer diagnostics and therapy. Mol

Aspects Med. 72:1008262020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chung YW, Bae HS, Song JY, Lee JK, Lee NW,

Kim T and Lee KW: Detection of microRNA as novel biomarkers of

epithelial ovarian cancer from the serum of ovarian cancer

patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 23:673–679. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Iorio MV and Croce CM: microRNA

dysregulation in cancer: Diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics.

EMBO Mol Med. 4:143–159. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Donkers H, Bekkers R and Galaal K:

Diagnostic value of microRNA panel in endometrial cancer: A

systematic review. Oncotarget. 11:2010–2023. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings

HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al: Long

non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer

metastasis. Nature. 464:1071–1076. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ayers D: Long non-coding RNAs: Novel

emergent biomarkers for cancer diagnostics. J Cancer Res Treat.

1:31–35. 2013.

|

|

65

|

Akman HB and Bensan AE: Noncoding RNAs and

cancer. Turk J Biol. 38:817–828. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Beckedorff FC, Amaral MS,

Deocesano-Pereira C and Verjovski-Almeida S: Long noncoding RNAs

and their implications in cancer epigenetics. Biosci Rep.

33:701–713. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Bhan A, Hussain I, Ansari KI, Kasiri S,

Bashyal A and Mandal SS: Antisense transcript long noncoding RNA

(lncRNA) HOTAIR is transcriptionally induced by estradiol. J Mol

Biol. 425:3707–3722. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Huang J, Ke P, Guo L, Wang W, Tan H, Liang

Y and Yao S: Lentivirus-mediated RNA interference targeting the

long noncoding RNA HOTAIR inhibits proliferation and invasion of

endometrial carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 24:635–642. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Shao Y, Yue X, Chu Y,

Yang C and Chen D: LncRNA HOTAIR down-expression inhibits the

invasion and tumorigenicity of epithelial ovarian cancer cells by

suppressing TGF-β1 and ZEB1. Discov Oncol. 14:2282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Sun MY, Zhu JY, Zhang CY, Zhang M, Song

YN, Rahman K, Zhang LJ and Zhang H: Autophagy regulated by lncRNA

HOTAIR contributes to the cisplatin-induced resistance in

endometrial cancer cells. Biotechnol Lett. 39:1477–1484. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Çorbacıoğlu ŞK and Aksel G: Receiver

operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy

studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value.

Turk J Emerg Med. 23:195–198. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Roest HP, IJzermans JNM and van der Laan

LJW: Evaluation of RNA isolation methods for microRNA

quantification in a range of clinical biofluids. BMC Biotechnol.

21:482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Peltier HJ and Latham GJ: Normalization of

microRNA expression levels in quantitative RT-PCR assays:

Identification of suitable reference RNA targets in normal and

cancerous human solid tissues. RNA. 14:844–852. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Aerts JL, Gonzales MI and Topalian SL:

Selection of appropriate control genes to assess expression of

tumor antigens using real-time RT-PCR. BioTechniques. 36:84–86.

8890–101. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|