Introduction

Bladder cancer is the seventh most commonly

diagnosed cancer in men worldwide and the tenth most common in both

sexes, with ~550,000 new cases each year (1–4). The

most common location of cancer in the urinary tract is the bladder.

Histologically, urothelial carcinoma is the most common type of

bladder cancer. According to the European Association of Urology,

urothelial carcinoma accounts for >90% of all bladder cancer

cases (1). Bladder cancer is a

heterogeneous disease and represents a spectrum of lesions with

varying degrees of malignancy. Urothelial bladder cancer is more

common in developed countries. Additionally, mortality rates are

the highest in certain parts of Europe and North Africa, and lowest

in Asia, Central America and Central Africa (1–3).

Urothelial bladder cancer is known to be linked to several major

risk factors, such as cigarette use, infections with the parasite

Schistosoma haematobium and occupational contact with

chemicals such as aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons (1–3). After radical treatment of bladder

cancer, metastases are diagnosed in up to 50% of patients and are

typically found within the first 2–3 years after surgery. Local and

distant recurrences have a poor prognosis (1,3–7).

Penile metastasis is extremely rare and is typically considered a

late sign of disease dissemination (3–7). The

primary source of penile metastasis is typically the genitourinary

tract, and less commonly the gastrointestinal tract (4–7).

Case report

A 65-year-old man visited the oncology clinic of the

Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology in

Warsaw (Poland) in January 2024 due to periodic bleeding from a

suspicious lesion on the foreskin and glans penis near the external

urethral orifice. The lesion was noticed and observed by the

patient for ~6 months. The patient was chronically treated for type

2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, CNS vascular dementia and irritable

bowel syndrome. The patient was taking two permanent medications:

Betaserc (24 mg once a day_ for the treatment of vertigo and

Metformax (500 mg twice a day) to manage diabetes mellitus.

Historically, the patient had undergone an appendectomy. As for the

family history, it was found that the patient's sister had died of

colon cancer.

The patient had presented to a urology clinic in

Prof. Witold Orłowski Clinical Hospital (Warsaw, Poland) due to

hematuria 15 years earlier. According to the medical history

provided by the patient, from 2019 the patient underwent multiple

transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) procedures due to

recurrent urothelial non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Due to the

patient receiving treatment at another hospital, it is not possible

to determine the exact number of TURBT procedures performed or the

location of the resected lesions during the procedures. Due to

recurrent pTa low-grade bladder cancer, the patient was offered and

subsequently qualified for Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

live-attenuated bacteria intravesical vaccine (so called BCG

therapy), which ultimately failed and resulted in recurrence. After

another TURBT, the histopathological examination revealed pTa

high-grade (HG) bladder cancer, leading to the discontinuation of

infusions. Meanwhile, in 2019 and at the same urology clinic, with

the use of a transrectal biopsy, the patient was diagnosed with

Gleason 6 (3+3) cT1c prostate cancer, according to the Union for

International Cancer Control, Tumor, Node, Metastasis

classification (8). For this

reason, the patient underwent active surveillance. Due to the lack

of response to BCG therapy, the concurrent diagnosis of prostate

cancer and a marked functional impairment of the bladder manifested

by increased lower urinary tract symptoms that originated from poor

tolerance to BCG therapy, the patient qualified for

cystoprostatectomy.

In October 2020, a radical cystoprostatectomy with

urinary diversion using Bricker's method was performed at the

urology center in Prof. Witold Orłowski Clinical Hospital. The

histopathology result following this procedure revealed pTa HG N0

R0 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and Gleason 7 (3+4) pT2 N0

R0 prostate cancer. The patient did not undergo urethrectomy during

cystoprostatectomy due to the lack of previously diagnosed tumor

in situ. Additionally, the documentation provided by the

patient did not describe the location of the lesions in the bladder

neck and prostatic urethra, which would be an indication for

ureterectomy. During the follow-up after bladder and prostate

removal surgery, no recurrence was found via imaging studies up to

36 months post-surgery. During a visit to an oncologist at the

Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology

(Warsaw, Poland) in October 2023, a computed tomography (CT) of the

chest, abdomen and pelvis was performed, which indicated no signs

of local recurrence or metastatic changes in the abdominal cavity

and pelvis. Hyperdense fatty tissue in the penile region was

observed and it was noted that further diagnosis by magnetic

resonance imaging should be considered. No lymphadenopathy was

found. The patient only provided a description of the examination

and therefore images are not shown here. At the urology visit

scheduled by the oncologist in October 2023 at the Maria

Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, the

patient was in good general condition, with good circulatory and

respiratory function and no enlarged peripheral lymph nodes. The

urostomy was draining normal urine. Red exophytic lesions suspected

of malignancy were found on the foreskin and anterior surface of

the penile glans. The patient was not diagnosed with phimosis.

There were no enlarged palpable lymph nodes in the inguinal area on

either side.

After a urological consultation at Maria

Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology in

February 2024, due to the macroscopic appearance of the lesions on

the glans penis, the patient qualified for and underwent a partial

penectomy. The surgical specimen was fixed in 10% neutrally

buffered formalin at room temperature (20–30°C) for 24 h. Then, the

representative samples were paraffin-embedded, sliced into 4 µm

thick sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Mar-Four) at

room temperature for 6–10 min and examined using conventional light

microscopy. Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed,

paraffin-embedded tissue sections (3 µm). Slides were

deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol to

water. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was carried out using

EnVision™ FLEX Target Retrieval Solution on a Dako Omnis or

Autostainer Link 48 platform with PT Link (preheat/cool 65°C,

incubation 20 min at 97°C; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) or

Cell Conditioning 1 buffer for 64 min at 95°C on a BenchMark ULTRA

automated stainer (Roche Tissue Diagnostics), according to the

manufacturers' protocols. Endogenous peroxidase activity was

blocked with the system-specific peroxidase-blocking reagent, then

ready-to-use or diluted primary antibodies were applied and

incubated at room temperature (list of markers; clones, dilutions

and suppliers are summarized in Table

I). Antibody binding was visualized using a polymer-based

HRP/DAB detection system (EnVision™ FLEX, Dako, Agilent

Technologies, Inc. or UltraView DAB IHC Detection Kit, Roche Tissue

Diagnostics). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (~5 min),

dehydrated, cleared and mounted in a permanent, non-aqueous medium.

All immunostained slides were evaluated using conventional light

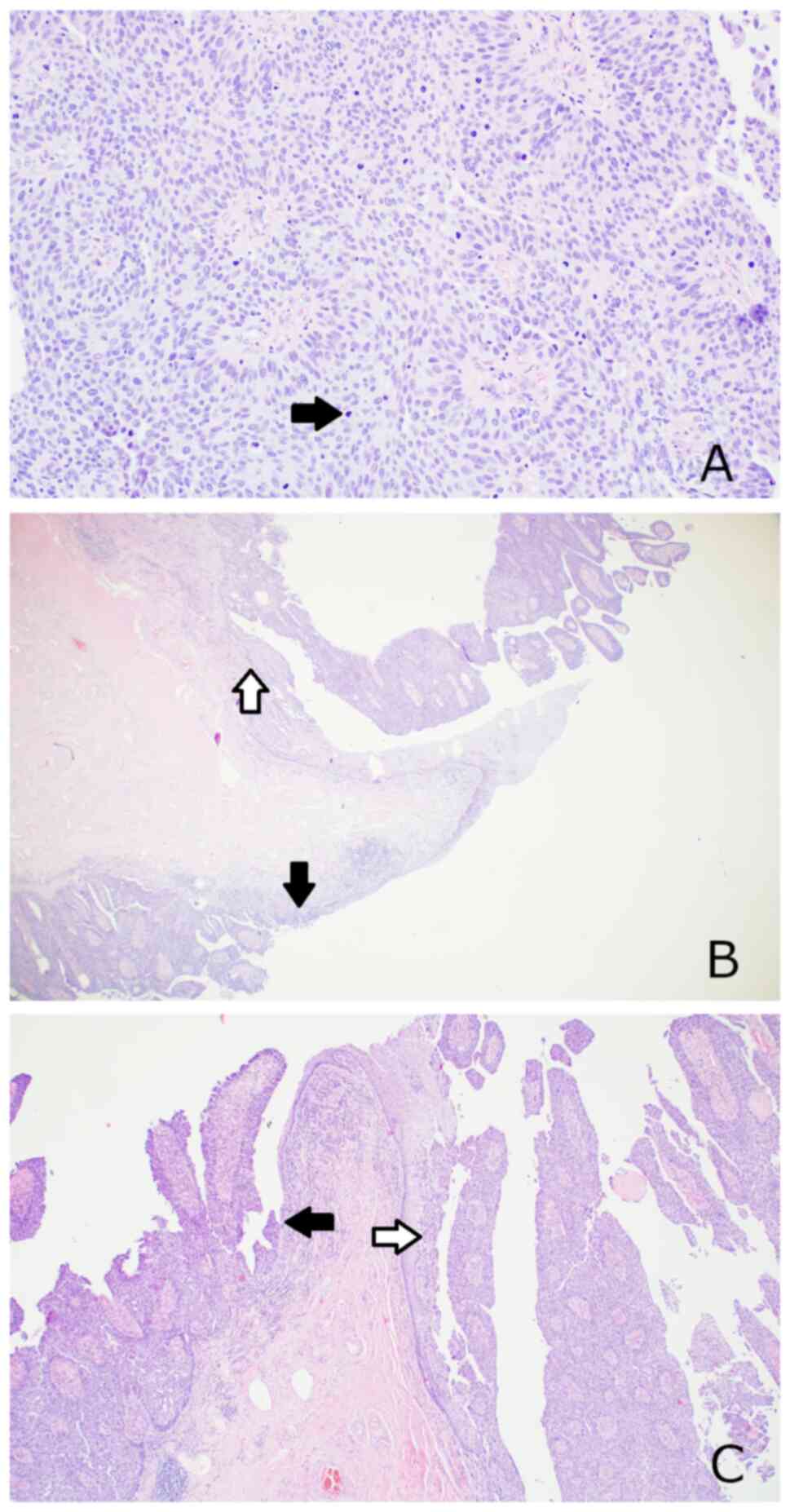

microscopy. The pathology report demonstrated high-grade urothelial

carcinoma (papillary configuration and architectural disorder and

enlarged pleomorphic oval shaped hyperchromatic nuclei, with

prominent nucleoli and frequent mitotic figures) of the urethra

with focal underlying connective tissue invasion (Fig. 1A and B). There was no direct

connection between the squamous epithelium lesion and the urethral

tumor (Fig. 1C). No angioinvasion

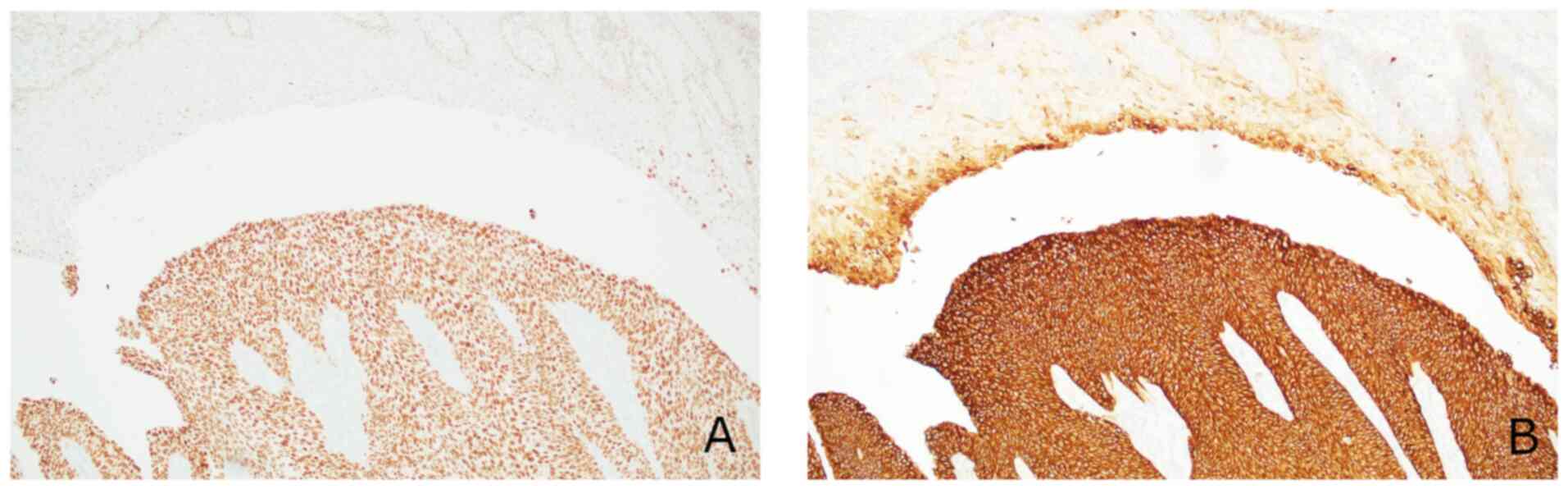

or perineural invasion was identified. Immunohistochemically, tumor

cells showed strong diffuse expression of GATA binding protein 3

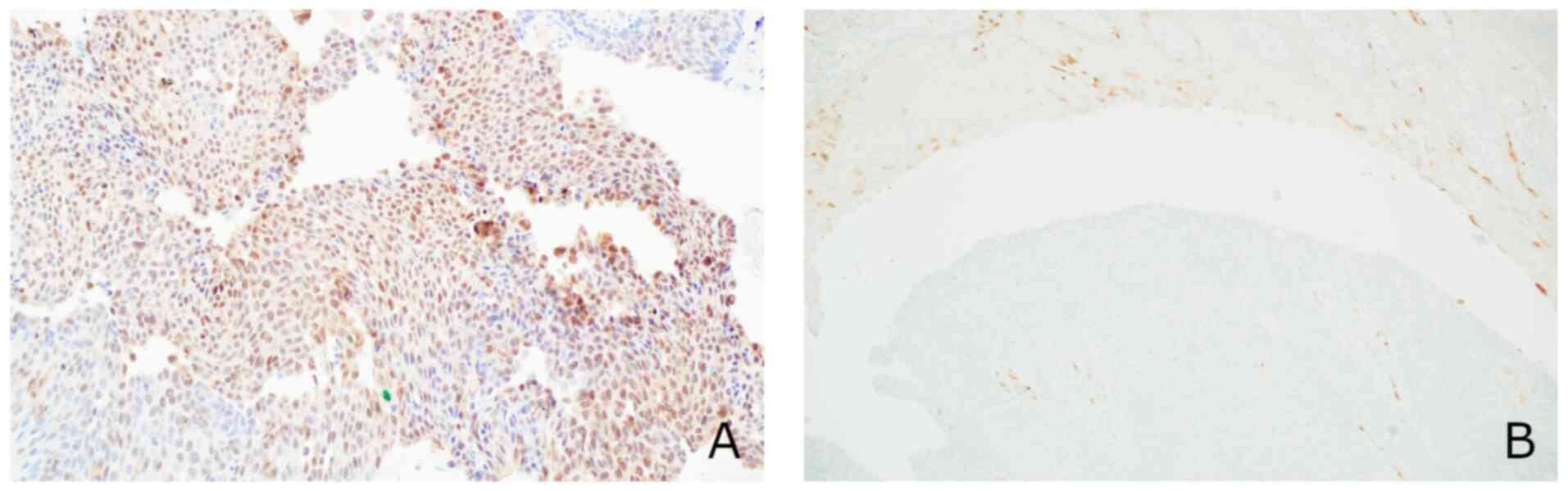

and cytokeratin 7 (Fig. 2), focal

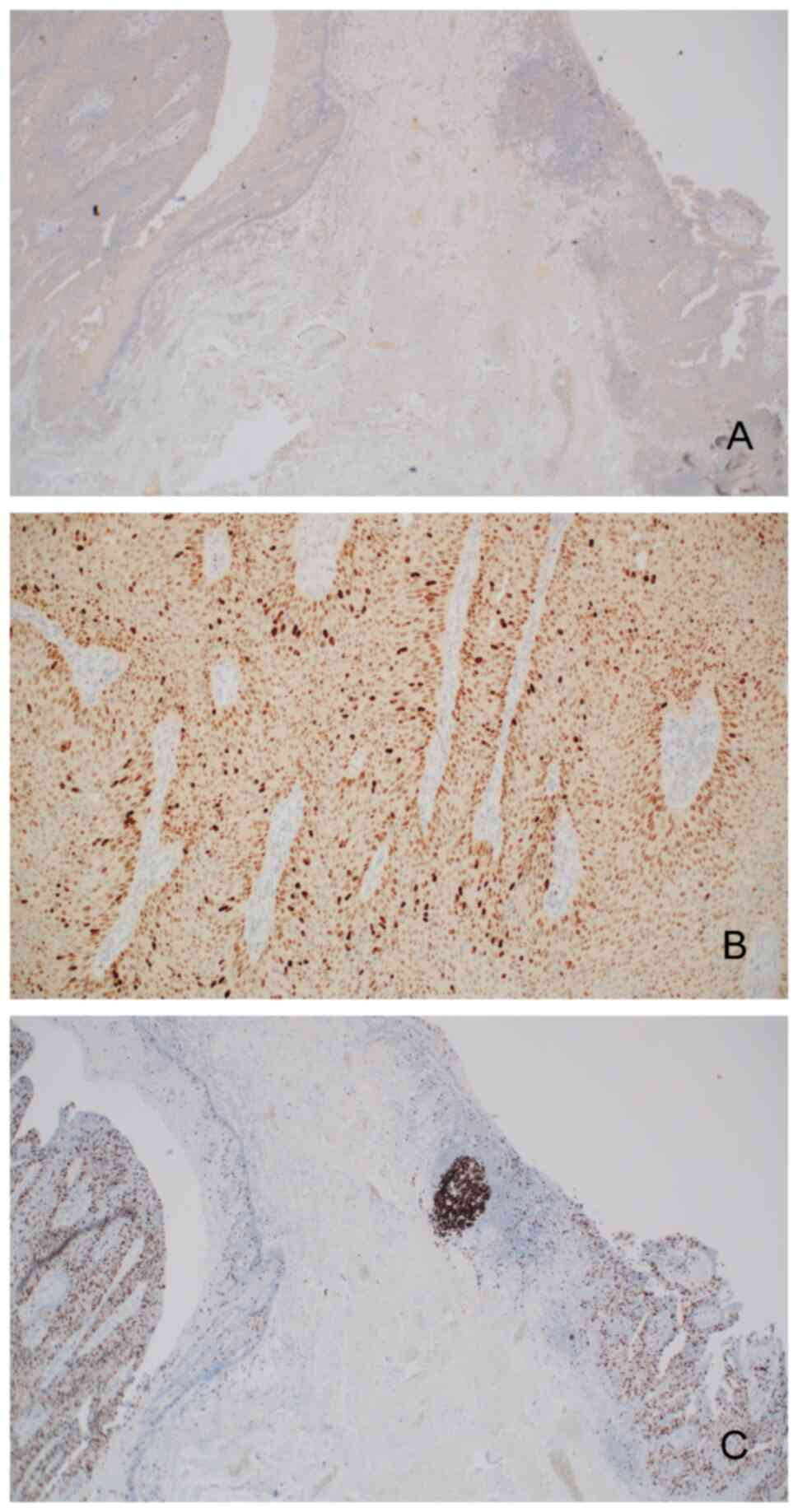

expression of S100 calcium binding protein P (Fig. 3A), no expression of p16 (Fig. 3B) or cytokeratin 20 (Fig. 4A) and upregulation of p53 (Fig. 4B). The proliferation index defined

by the expression of Ki-67 (MIB-1) was high (in ~70% of tumor

cells) (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, a

field of non-invasive carcinoma was found within the glans and

foreskin epithelium, presenting the same morphology and

immunohistochemical profile as the urethral tumor. We consider that

the aforementioned microscopic description should be interpreted as

urothelial carcinoma implantation into the glans and foreskin

epithelium, most likely due to the migration of neoplastic cells

originating from the bladder or urethra tumor via urine.

| Table I.Details of immunohistochemical

staining. |

Table I.

Details of immunohistochemical

staining.

| Protein | Cat. no. | Clone | Dilution | Supplier | Platform |

|---|

| CK7 | IR619 | OV-TL 12/30 | Ready to use | Dako (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) | Autostainer |

| GATA3 | 7107749001 | L50-823 | Ready to use | Roche

Diagnostics | Ventana

BenchMark |

| S100P | 06523935001 | 16/f5 | 1:500 | Roche

Diagnostics | Manual |

| Ki-67 | GA626 | MIB-1 | Ready to use | Dako (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) | Omnis |

| p53 | M7001 | D-07 | Ready to use | Dako (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) | Omnis |

| p16 | 06695248001 | E6H4 | Ready to use | Roche

Diagnostics | Ventana

BenchMark |

| CK20 | IR777 | Ks20.8 | Ready to use | Dako (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) | Autostainer |

After receiving the histopathology results, the

patient qualified for urethroscopy and diagnostic dissemination. On

April 10, 2024, the patient underwent a follow-up urethroscopy,

during which the urethra was found to be normal. Therefore, no

specimens were collected for histopathology examination.

Macroscopically, the physical examination also showed no suspicious

changes in the penile stump. CT scans of the chest, abdomen and

pelvis revealed no lesions of recurrent disease or distant

metastases. The patient had three follow-up visits by August 2025

during which no recurrence of the disease was found.

Discussion

Urothelial carcinoma is a major histological subtype

that accounts for nearly 90% of the diagnosed cases of bladder

cancer (1–3). The incidence and prevalence of

urothelial carcinoma increases with age, peaking in the eighth

decade of life (1). Risk factors

for developing urothelial carcinoma include age, sex (men are 3–4

times more likely than women to develop this type of cancer),

smoking (which accounts for at least half of all cases), exposure

to environmental toxins, inflammation and infection of the bladder,

genetic predisposition and exposure to radiation and chemotherapy

(1–4). The main symptom of urothelial

carcinoma is gross hematuria (especially with clots) or hematuria.

Less common symptoms include bladder inflammation, difficulty

urinating or frequent urination. Some urothelial carcinomas are

detected incidentally on imaging studies, such as ultrasound or CT,

performed for unrelated reasons. The prognosis of urothelial

carcinoma varies and depends on a number of factors, such as tumor

size, number of lesions found by cystoscopy, T category in the TNM

staging, tumor grade and coexisting carcinoma in situ

(1). Patients undergoing cystectomy

require long-term monitoring for recurrence. Distant spread of

bladder cancer typically occurs through lymphatic pathways. The

finding of metastasis in the lymph nodes serves as a key element in

establishing the survival prognosis of patients and dictates the

requirement for treatment (1,4). The

basic mechanisms by which metastases can spread to the skin include

direct invasion from an underlying tumor, implantation from a

surgical scar and spreading via the lymphatic system or blood

vessels (1,5–7,9–13).

Distant relapse affects ~50% of patients and is generally detected

within 24 months following operation. The most frequent sites for

these recurrences are the lymph nodes located above the aortic

split, the pulmonary tissue, the hepatic system and the bones

(1,5,9).

The occurrence of metastatic lesions in the penile

region is a very rare phenomenon and is typically associated with

the spread of cancer via the blood vessels. Typically, the first

symptom of penile metastatic lesions is a palpable penile lump or

mass (51%), priapism (27%), lower urinary tract symptoms (27%),

penile pain (17%), urinary retention (13%) and skin changes such as

redness or ulceration on the penis (11%) (5–7,9,14).

Although penile metastasis can be a late sign of cancer progression

and spread, systemic treatment (chemotherapy and immunotherapy) can

improve the prognosis of patients (6,8,9,14).

Other therapeutic options for lesions located on the penis include

conservative treatment, partial or total penectomy, radiation

therapy or systemic treatment. In most cases, due to local

advancement and/or evidence of spread, chemotherapy or palliative

care is the only treatment option for these patients (5,7,9,14).

In cases of uncontrolled local symptoms, such as untreatable pain

or bleeding, palliative surgery (partial or total penectomy) may be

advised (14).

It is possible for urothelial carcinoma cells to

implant along the urinary tract during micturition (10,12);

however, implantation of the tumor into the foreskin and the

epithelium of the glans is extremely rare (5). The uniqueness of the present case lies

not only in this rare localization, but also in the fact that the

patient had undergone cystoprostatectomy and therefore no longer

had a bladder. In such circumstances, any implantation with urine

should be located in the Bricker loop or urostomy. An alternative

hypothesis for the neoplastic changes that occurred in the

patient's urethra and foreskin may be the iatrogenic transfer of

cancer cells to the glans penis via surgical instruments or gloves.

However, we consider this unlikely in the present case due to the

high standards of sterility maintained during the procedures and

the 3-year period from cystoprostatectomy until the tumor

recurrence was confirmed. The lack of CT images and pathology from

the diagnosis and treatment of the patient prior to the occurrence

of metastases to the glans penis may be considered a limitation of

the present case report. However, recurrence of the disease

associated with the transfer of tumor cells within urine therefore

confirms the high malignancy of urothelial carcinoma and the need

for close observation of patients after radical treatment to detect

disease recurrence or dissemination. In terms of the upper urinary

tract, there is a hypothesis that cancer cells located in the upper

sections, such as the renal pelvis or ureter, may nest in the

bladder while not being present in the lower parts of the ureter

(1,4). To the best of our knowledge, there is

no data to suggest that the presence of a tumor in the distal part

of the urethra guarantees the presence of a tumor in the proximal

part of the urethra; however, in each case, the entire urethra

should be examined. In patients who have undergone

cystoprostatectomy or cystectomy with Bricker urinary diversion for

oncological reasons, a physical examination of the penis should not

be overlooked. In cases where the tumor location in the preceding

TURBT was in the bladder neck or near the proximal part of the

urethra, it would be reasonable to consider performing follow-up

urethroscopy for more accurate monitoring of the oncological

disease. This would improve the detection of potential urothelial

cancer recurrences and the patient's quality of life. At present,

increasingly more treatments are available for the disease in the

generalized stage, prolonging the lives of patients and enabling

them to achieve long-term remissions. Although the location of

metastatic lesions in the penis is encountered occasionally, any

occurrence of urethral bleeding should be diagnosed and the penis

should be evaluated to exclude this location of metastatic lesions.

Men with a history of bladder cancer should be aware of the

possibility of penile metastasis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PK wrote the manuscript, collected data, and made

substantial contributions to the conception and design of the

study. PK and TK performed the operation, provided tissues that

could be used as material for the study and were involved in the

acquisition of data. OKS and RR carried out the histopathological

and microscopic examinations of the tissue, acquired data and made

substantial contributions to data interpretation. PK and TD made

significant contributions to the conception and content of the

manuscript. PN and BGN made substantial contributions to the

discussion section, and were responsible for the analysis and

interpretation of the data presented in the case report. TK and TD

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The patient provided written informed consent for

participation in the study. The informed consent procedures were in

compliance with The Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of any data and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

van der Heijden AG, Bruins HM, Carrion A,

Cathomas R, Compérat E, Dimitropoulos K, Efstathiou JA, Fietkau R,

Kailavasan M, Lorch A, et al: EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and

Metastatic Bladder Cancer. European Association of Urology

Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer:

Summary of the 2025 Guidelines. Eur Urol. 87:582–600. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chavan S, Bray F, Lortet-Tieulent J,

Goodman M and Jemal A: International variations in bladder cancer

incidence and mortality. Eur Urol. 66:59–73. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mari A, Campi R, Tellini R, Gandaglia G,

Albisinni S, Abufaraj M, Hatzichristodoulou G, Montorsi F, van

Velthoven R, Carini M, et al: Patterns and predictors of recurrence

after open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: A comprehensive

review of the literature. World J Urol. 36:157–170. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Polanco-Pujol L, Caño-Velasco J,

Moralejo-Garate M, Bataller-Monfort V, Subirá-Ríos D and Hernández

FC: Penile metastasis from urothelial carcinoma: Review of

literature. Arch Esp Urol. 74:208–214. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yu T, Cui X, Liang N, Wu S and Lin C:

Postoperative metachronous metastasis of bladder cancer to penis: A

case report. Arch Esp Urol. 76:622–626. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sönmez NC, Coşkun B, Arisan S, Güney S and

Dalkılıç A: Early penile metastasis from primary bladder cancer as

the first systemic manifestation: A case report. Cases J.

2:72812009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK and

Wittekind C: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 8th edition.

John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; Oxford: 2017

|

|

9

|

Guvel S, Kilinc F, Torun D, Egilmez T and

Ozkardes H: Malignant priapism secondary to bladder cancer. J

Androl. 24:499–500. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Weeratunga GN: Cutaneous metastatic

implantation of ureteric urothelial carcinoma to the glans and

prepuce. Urol Case Rep. 47:1023392023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ogiso S, Maeno A, Yamashita M, Souma T,

Nakamura K and Okuno H: Micturitional disturbance due to labial

adhesion as a cause of vaginal implantation of bladder urothelial

carcinoma. Int J Urol. 13:1454–1455. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Makino T, Kitagawa Y and Namiki M:

Metastatic urothelial carcinoma of the prepuce and glans penis:

Suspected implantation of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer via

urine. Case Rep Oncol. 7:509–512. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Miyamoto T, Ikehara A, Araki M, Akaeda T

and Mihara M: Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma of the penis:

Suspected metastasis implantation from a bladder tumor. J Urol.

163:15192000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

European Association of Urology (EAU), .

ASCO Guidelines on Penile Cancer. EAU Central Office; Arnhem: 2025,

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/penile-cancerAugust

8–2025

|