Introduction

Liver cancer remains one of the leading causes of

cancer-related mortality globally (865,269 new cases and 757,948

deaths in 2022), with a high incidence in regions affected by

chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B and C infection

(1–3). Despite advances in early detection and

treatment strategies, the prognosis for patients with liver cancer

remains poor, mainly due to the aggressive nature of the tumor,

including its ability to metastasize and develop resistance to

conventional therapies, such as surgical resection, ablation

therapy and transarterial chemoembolization (4). Therefore, there is a key need to

identify novel biomarkers and mechanistic regulators of liver

cancer that may inform future therapeutic development.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are small non-coding RNAs

that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression and are

involved in several biological processes, including cell

proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and metabolism (5,6). In

cancer, miRNAs can function as either oncogenes or tumor

suppressors, depending on their target genes and the cellular

context (7). miR-448 has been

identified as a tumor suppressor in several types of cancer,

including breast, gastric and liver cancer, where it is implicated

in the regulation of cell proliferation, migration and invasion

(8–11). However, the precise molecular

mechanisms underlying its role in liver cancer progression remain

to be elucidated.

One of the hallmarks of cancer cells is altered

metabolism, with a particular emphasis on the reprogramming of

glucose metabolism. The Warburg effect, characterized by the

upregulation of glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen, is a

common metabolic shift observed in several types of cancer,

including liver cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer and

non-small cell lung cancer (12–15).

This metabolic alteration supports the high energy demands of

rapidly proliferating cancer cells, and facilitates tumor

progression and metastasis (16).

Previous studies have suggested that miRNAs, including miR-448,

miR-126-3p and miR-423-5p, may modulate glycolysis as well as lipid

and amino acid metabolism, although the direct association between

miR-448 and glycolytic regulation in liver cancer remains to be

elucidated (17–19).

Ras-related protein Rab-7a (RAB7A), a member of the

small GTPase family, serves a key role in vesicular trafficking and

endosomal maturation. It has been reported to regulate numerous

cellular processes, including autophagy, metabolism and cell

migration (20). Furthermore, RAB7A

has been shown to be upregulated in several types of cancer,

including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma

and colon adenocarcinoma, and its elevated expression is associated

with poor prognosis and aggressive tumor behavior (21–23).

Recent studies have suggested that RAB7A may influence glycolytic

metabolism in cancer cells, although its role in liver cancer

glycolysis is yet to be fully elucidated (24,25).

It was hypothesized in the present study that

exosomal miR-448 (EXO-miR-448) suppresses liver cancer progression

by directly targeting RAB7A and inhibiting glycolytic metabolism.

Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the expression levels

of RAB7A and miR-448 in liver cancer and normal liver cell lines,

to explore the relationship between EXO-miR-448 and RAB7A, and to

evaluate the effects of EXO-miR-448 on proliferation, migration,

invasion and glycolytic activity in liver cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

All cell lines (HepG2, Hep3B, SK-HEP-1 and THLE-2)

were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The

identity of all cell lines was confirmed by the supplier using

short tandem repeat profiling. In addition, all cell lines were

routinely cultured for <10 passages and tested negative for

mycoplasma contamination using PCR-based assays prior to use. Cells

were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2 using DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution. The use of commercially

obtained human cell lines was approved by the Ethics Committee of

The Second Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University

(Haikou, China) and all procedures were performed in accordance

with institutional guidelines.

Exosome isolation and

identification

Exosomes were isolated from HepG2 cell culture

supernatants using ultracentrifugation. Briefly, the cell culture

supernatant was sequentially centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at

4°C, 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C

to remove cells and debris, followed by ultracentrifugation at

100,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C to pellet exosomes. Exosomes were

identified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL, Ltd.),

nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA; ZetaView®; Particle

Metrix GmbH), and western blotting of exosomal markers and a

negative control (CD63: 1:500, cat. no. ab68418, Abcam; CD9: 1:500,

cat. no. WL06408, Wanleibio Co., Ltd.; calnexin:1:500, cat. no.

WL03062, Wanleibio Co., Ltd.). For TEM analysis, isolated exosomes

were examined without fixation, embedding or sectioning. A 10 µl

exosome suspension was placed onto a carbon-coated copper grid and

allowed to adsorb for 10 min at 25°C. Excess liquid was removed

with filter paper, followed by negative staining with 2%

phosphotungstic acid for 2 min at 25°C. The grids were then air

dried and examined using TEM. For NTA, the sample chamber was first

rinsed with deionized water, and the instrument was calibrated

using 110 nm polystyrene microspheres. The chamber was then washed

with PBS, and exosome samples were diluted 1:200 in PBS before

measurement using the ZetaView instrument.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells (THLE-2,

SK-HEP-1, Hep3B and HepG2) or isolated exosomes using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For mRNA

analysis, RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a

PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc.), whereas

for miRNA analysis, cDNA was synthesized using a miRNA First-Strand

cDNA Synthesis Kit (Tailing Reaction) (cat. no. B532451; Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturers' protocols.

Subsequently, qPCR was performed on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). miRNA

expression was analyzed using 2X Fast Taq Plus PCR Master Mix

(Biosharp Life Sciences) supplemented with SYBR Green (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) under the following

conditions: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 20

sec, 60°C for 20 sec and 70°C for 10 sec, with melting curve

analysis performed at the end of amplification. mRNA expression was

analyzed using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II

(Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol, with

the following thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C

for 34 sec. The relative expression levels of miR-448 were

normalized to U6, whereas those of RAB7A, sphingosine-1-phosphate

phosphatase 1 (SGPP1), vasohibin 2 (VASH2), mitochondrial pyruvate

carrier 1 (MPC1) and thymosin β 4 X-linked (TMSB4X) were normalized

to β-actin using the 2−ΔΔCq method (26). Primer sequences for mRNA targets and

β-actin were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. and are listed

in Table I. The forward primer for

hsa-miR-448 was synthesized by General Biotech (Anhui) Co., Ltd.

The reverse primer for miR-448 and the U6 primer were supplied as

built-in components of the miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis

Kit.

| Table I.Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| RAB7A | F:

GACTGCTGCGTTCTGGT |

|

| R:

CCTCCGTTTCCTGCTTA |

| β-actin | F:

GGCACCCAGCACAATGAA |

|

| R:

TAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGG |

| hsa-miR-448 | F:

TTGCATATGTAGGATGTCCCAT |

| SGPP1 | F:

CTCCATTCATCATCATCGGGCTTC |

|

| R:

CTAGTATCTCGGCTGTGTCTCCTC |

| VASH2 | F:

AGGAACGCCGCCTTCTTGG |

|

| R:

CATGTAATTCTGGATCGCCTGGAG |

| MPC1 | F:

TGCCCTCTGTTGCTATTCTTTGAC |

|

| R:

AGCCGCCCTCCCTGGATG |

| TMSB4X | F:

CTGACAAACCCGATATGGCTGAG |

|

| R:

GCCTGCTTGCTTCTCCTGTTC |

RNase A and Triton X-100 treatment for

verification of EXO-miR-448

To determine whether miR-448 in the culture

supernatant was encapsulated within exosomes, the conditioned

medium of HepG2 cells was collected and centrifuged at 300 × g for

10 min and 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cells and cellular

debris. The supernatants were then treated with RNase A (100 µg/ml)

at 37°C for 60 min to degrade free extracellular miRNA, or with

RNase A (100 µg/ml) plus Triton X-100 (1%) at 37°C for 30 min to

disrupt vesicle membranes and degrade encapsulated miRNA.

Subsequently, the levels of miR-448 in the supernatants were

determined by RT-qPCR using the aforementioned procedure.

Preparation and verification of

miR-448 enriched exosomes

HepG2 cells were used as donor cells to generate

miR-448 enriched exosomes. HepG2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates

at a density of 2×105 cells/well. Cells were transfected

with miR-448 mimics or control mimics (mimics NC) (JTS Scientific

Co., Ltd.) using Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), with 75 pmol mimics/well in a final

volume of 2.5 ml, and incubated at 37°C for 48 h according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The sequences were as follows: miR-448

mimics, sense 5′-UUGCAUAUGUAGGAUGUCCCAU-3′, antisense

5′-GGGACAUCCUACAUAUGCAAUU-3′; And mimics NC, sense

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′, antisense 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′.

After 48 h, the culture supernatant was collected and exosomes were

isolated by differential ultracentrifugation (300 × g for 10 min,

2,000 × g for 10 min, 10,000 × g for 30 min and 100,000 × g for 70

min, all at 4°C). Exosomes derived from miR-448 mimic-transfected

donor cells and mimics NC-transfected donor cells were designated

EXO-miR-448 and EXO-NC, respectively. For functional assays, HepG2

cells were treated with EXO-miR-448 or EXO-NC (25 µg/ml) at 37°C.

Cells were analyzed at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h for the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay, whereas for EdU, migration and invasion

assays, cells were analyzed after 48 h of exosome treatment. To

confirm the successful enrichment of miR-448 in exosomes, total RNA

was extracted from the isolated exosomes, and RT-qPCR was performed

to quantify miR-448 expression levels.

Western blot analysis

Cells (THLE-2, SK-HEP-1, Hep3B and HepG2) or

isolated exosomes were lysed using RIPA buffer (Beyotime

Biotechnology) containing protease inhibitors and protein

concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein samples

(40 µg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 5% stacking gel, and 8

or 13% separating gels, and transferred onto PVDF membranes

(MilliporeSigma). Subsequently, the membranes were blocked with 5%

skim milk at 37°C for 2 h, and were incubated overnight at 4°C with

the following primary antibodies: RAB7A (1:1,000; cat. no. A12308;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), CD63, CD9, calnexin and β-actin

(1:1,000; cat. no. WL01372; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.). The membranes

were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (goat

anti-rabbit IgG-HRP; 1:5,000; cat. no. WLA023; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.)

at 37°C for 2 h. Protein bands were visualized using the Clarity™

Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and were

analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.54; National Institutes

of Health).

Transfection and siRNA knockdown

assays

HepG2 cells were seeded at a density of

~2×105 cells/well in 6-well plates and transfected with

RAB7A small interfering (si)RNAs (si-RAB7A-1, si-RAB7A-2 and

si-RAB7A-3) or NC siRNA using Lipofectamine 3000. The final

concentration of siRNAs in each well was 50 nM, and transfection

was performed at 37°C for 48 h according to the manufacturer's

instructions. After 48 h, transfection efficiency was confirmed

using RT-qPCR and western blotting. The siRNA with the highest

knockdown efficiency was selected for subsequent experiments and

termed si-RAB7A. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table II.

| Table II.Sequences of siRNAs used for RAB7A

knockdown. |

Table II.

Sequences of siRNAs used for RAB7A

knockdown.

| siRNA | Sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| siRNA NC | S:

UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT |

|

| AS:

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

| RAB7A siRNA-1 | S:

CACAAUAGGAGCUGACUUUTT |

|

| AS:

AAAGUCAGCUCCUAUUGUGTT |

| RAB7A siRNA-2 | S:

UUAUCAUCCUGGGAGAUUCTT |

|

| AS:

GAAUCUCCCAGGAUGAUAATT |

| RAB7A siRNA-3 | S:

CAGUAUGUGAAUAAGAAAUTT |

|

| AS:

AUUUCUUAUUCACAUACUGTT |

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The 3′-UTR fragment of RAB7A containing the putative

miR-448 binding site (wild-type; WT) and the corresponding mutant

(MUT) were cloned into the pmirGLO dual-luciferase reporter vector

(Promega Corporation). HepG2 cells were co-transfected with pmirGLO

constructs and either miR-448 mimics or mimics NC, as

aforementioned, using Lipofectamine 3000. After 48 h, luciferase

activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

System (Promega Corporation) and normalized against Renilla

luciferase activity.

Cell viability and proliferation

assays

HepG2 cell viability and proliferation were assessed

using CCK-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) and EdU incorporation

assays (Beyotime Biotechnology). For CCK-8, absorbance was measured

at 450 nm at the indicated time points (0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h).

For the EdU assay, cells were incubated with EdU at a final

concentration of 10 µM at 37°C for 2 h. Cells were then fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde at 25°C for 15 min and permeabilized with PBS

containing 0.3% Triton X-100 at 25°C for 15 min. EdU staining was

performed using the Click reaction cocktail at 25°C for 30 min in

the dark, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI at 25°C for 3

min, followed by three washes with PBS (5 min each).

EdU+ cells were observed and counted under a

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation) according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Cell migration and invasion

assays

Migration and invasion were evaluated using 24-well

Transwell chambers (pore size, 8 µm; Corning, Inc.) coated with or

without Matrigel (BD Biosciences), respectively. For the invasion

assay, Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was thawed at 4°C overnight and

diluted on ice, and 50 µl was added to the upper chamber and

allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were harvested and

resuspended in serum-free medium, and 1×105 cells in 200

µl were seeded into the upper chamber per well, whereas the lower

chamber was filled with 800 µl DMEM containing 10% FBS. The

chambers were then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48

h, after which, the Transwell chambers were washed with PBS, fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 25°C and stained with 0.5%

crystal violet for 5 min at 25°C. Images of the cells were then

captured and the cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation) at ×200 magnification.

Measurement of glycolysis-related

metabolites

HepG2 cells were homogenized in PBS, followed by

centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants

were then collected, kept on ice and subsequently used for lactate

measurement with an L-lactate assay kit (cat. no. A019-2-1; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Intracellular ATP levels were determined using an ATP

assay kit (cat. no. S0026; Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Glucose uptake was assessed using a

fluorescent glucose analog

[2-N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose

(2-NBDG); Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.]. Cells were

incubated with 2.5 µg/ml 2-NBDG for 30 min at 37°C, washed with PBS

and analyzed using a NovoCyte flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). Data were processed using NovoExpress software (version

1.5.0; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Measurement of extracellular

acidification rate (ECAR)

The ECAR, as an indicator of glycolytic activity,

was measured using a Seahorse XF8 extracellular flux analyzer

(Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Briefly, HepG2 cells from the

different treatment groups were seeded into XF8 cell culture

microplates at a density of 1×104 cells/well and allowed

to adhere for 12 h. The culture medium was then replaced with

Seahorse XF assay medium according to the manufacturer's

instructions, and cells were incubated at 37°C in a

non-CO2 incubator for 60 min to allow equilibration.

After baseline measurements were recorded, glucose (10 mM),

oligomycin (1 µM) and 2-deoxy-D-glucose (50 mM) were sequentially

injected at the indicated time points by the analyzer, and ECAR was

continuously monitored. ECAR data were analyzed using Wave software

(version 2.6; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and used to evaluate

glycolytic function.

Rescue experiment

To validate that RAB7A mediates the effects of

miR-448, HepG2 cells were seeded to reach 70–80% confluence and

transfected with a RAB7A overexpression (OE) plasmid (RAB7A OE) or

the corresponding empty vector based on the pcDNA3.1 backbone

(Changsha Zeqiong Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) using Lipofectamine 3000

according to the manufacturer's instructions at 37°C. After 24 h of

transfection, cells were treated with EXO-miR-448 (25 µg/ml) at

37°C. After a further 48 h, cell proliferation, migration, invasion

and glycolytic activity were re-assessed as described in the

aforementioned methods.

Bioinformatics analysis

RAB7A expression in HCC tissues compared with that

in normal tissues was analyzed using The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA)-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma dataset (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). RNA-seq TPM

expression data from a total of 424 tumor samples and 50 adjacent

normal tissue samples were assessed. Among these samples, 50 normal

samples were paired with their corresponding tumor samples, whereas

the remaining tumor samples were unpaired. Potential downstream

target genes of miR-448, as well as the predicted miR-448 binding

site within the 3′-UTR of RAB7A, were identified using the

TargetScanHuman database (version 8.0; http://www.targetscan.org). Genes with high context

++ scores were selected for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism software (version 9.0; Dotmatics). All data are presented as

the mean ± SD from ≥3 independent experiments. For paired data, a

paired Student's t-test was used. Unpaired Student's t-test or

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for

comparison among groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

miR-448 expression is downregulated in

liver cancer cells and enriched in exosomes

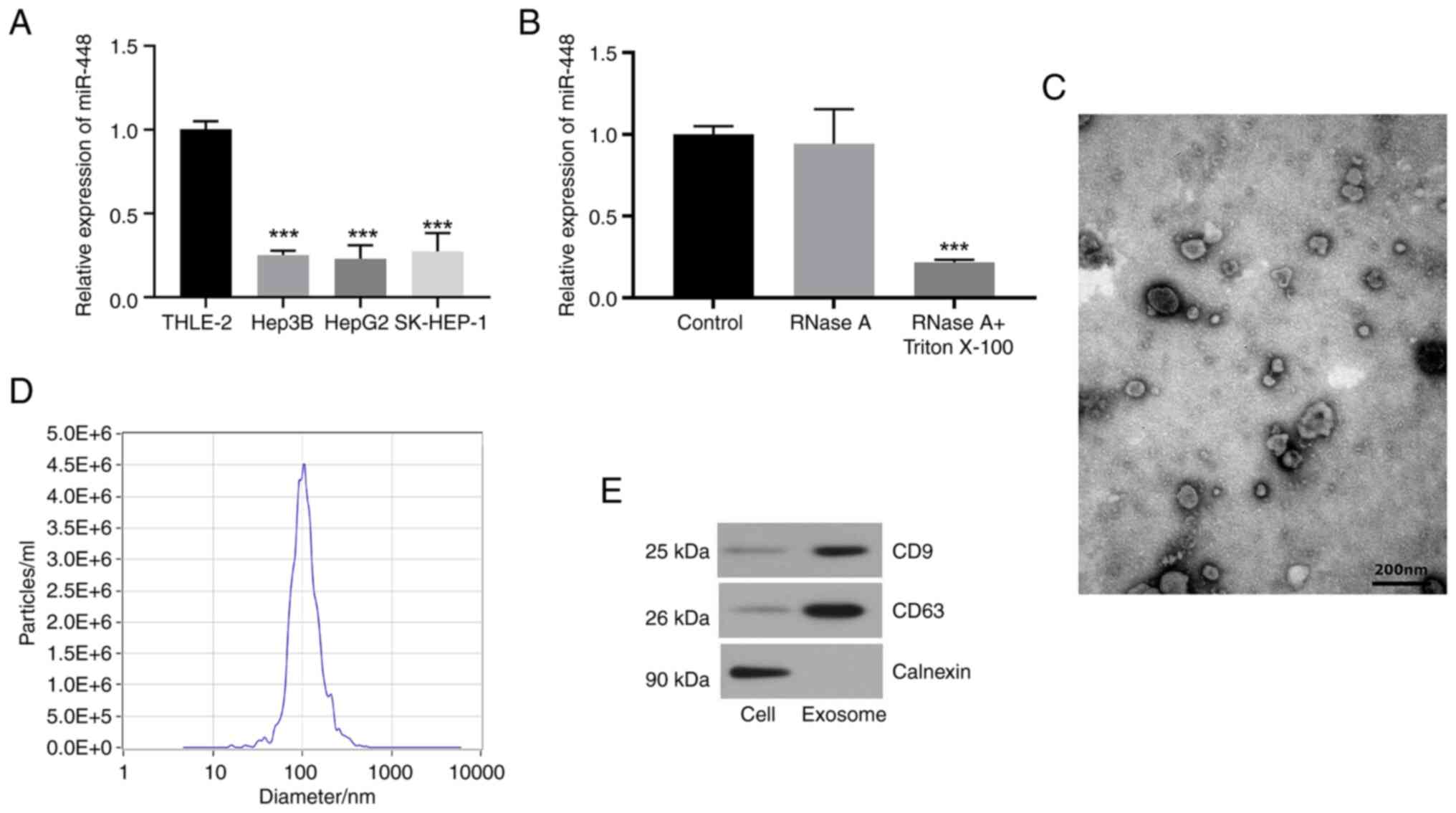

RT-qPCR analysis revealed that miR-448 expression

was significantly downregulated in liver cancer cell lines (HepG2,

Hep3B and SK-HEP-1) compared with in normal THLE-2 liver cells

(Fig. 1A). Subsequent experiments

involving RNase A treatment of the supernatant of HepG2 cells

revealed no significant alteration in miR-448 expression levels;

however, treatment with both RNase A and Triton X-100 resulted in a

significant reduction of miR-448 levels (Fig. 1B). These findings indicated that

miR-448 was predominantly contained within exosomes, rather than

being directly released into the extracellular milieu. Furthermore,

exosomes were isolated from the culture medium of HepG2 cells and

characterized by TEM and NTA, confirming their typical cup-shaped

morphology and a median particle size of ~104 nm, consistent with

the expected range for exosomes (Fig.

1C and D). Western blotting demonstrated successful exosome

isolation by detecting the exosomal markers CD63 and CD9, with

calnexin serving as a negative control (Fig. 1E). These results suggested that

miR-448 is not only downregulated in liver cancer cells but also

exists in exosomes, potentially serving a role in cell-to-cell

communication within the tumor microenvironment.

EXO-miR-448 inhibits liver cancer cell

proliferation, migration and invasion

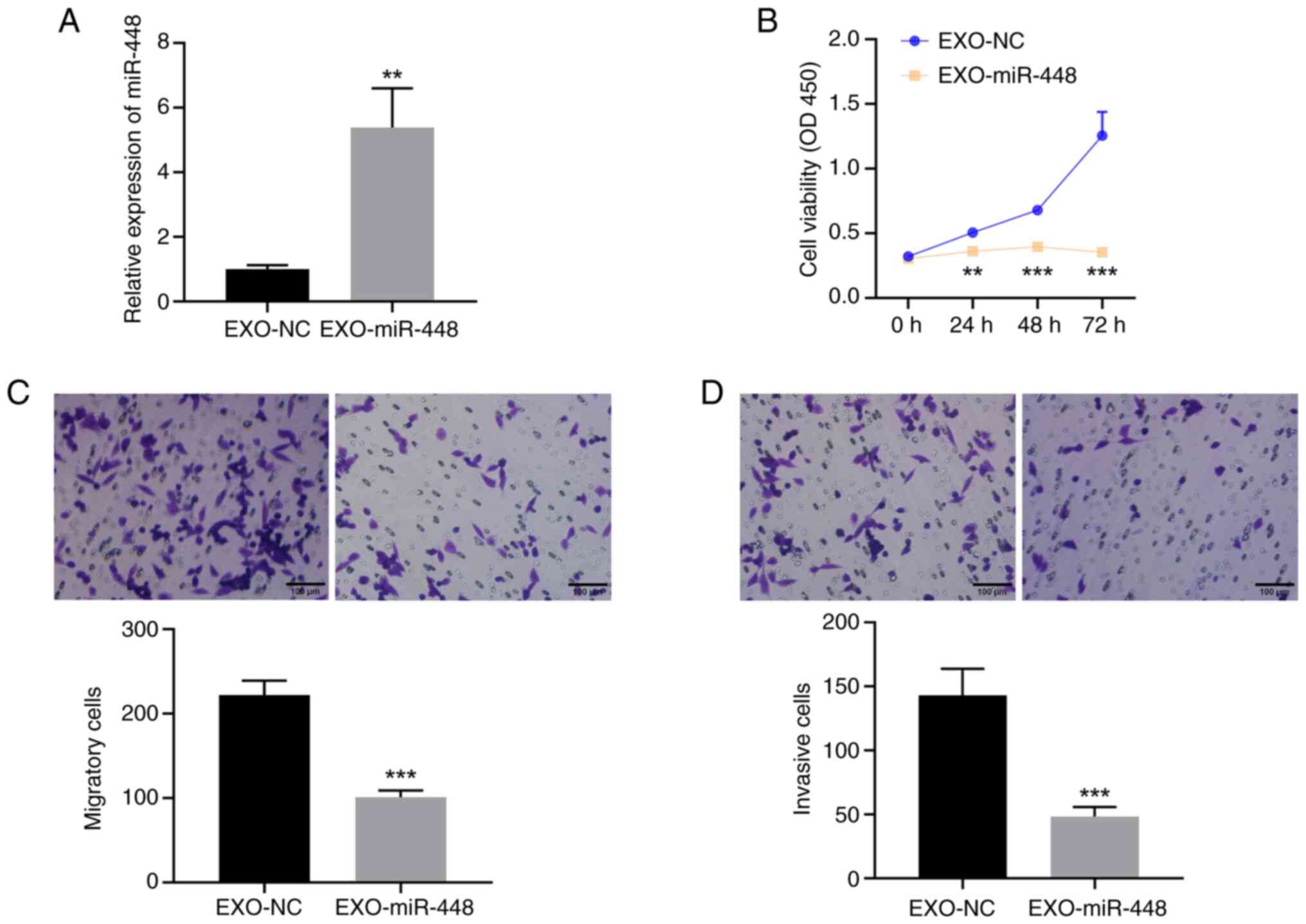

To explore the functional role of miR-448 in liver

cancer, HepG2 cells were transfected with either miR-448 mimics or

mimics NC, and exosomes were collected and named EXO-miR-448 and

EXO-NC, respectively. The enrichment of miR-448 in exosomes was

confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A). To

evaluate the biological effects of EXO-miR-448, cell viability,

migration and invasion were assessed in HepG2 cells treated with

EXO-miR-448 or EXO-NC. The CCK-8 assay (Fig. 2B) demonstrated that EXO-miR-448

significantly reduced cell viability compared with EXO-NC.

Furthermore, Transwell migration (Fig.

2C) and invasion assays (Fig.

2D) revealed that EXO-miR-448 treatment led to a significant

decrease in both migration and invasion of HepG2 cells compared

with those in the EXO-NC group. These results suggested that

EXO-miR-448 effectively inhibits the proliferation, migration and

invasion of liver cancer cells.

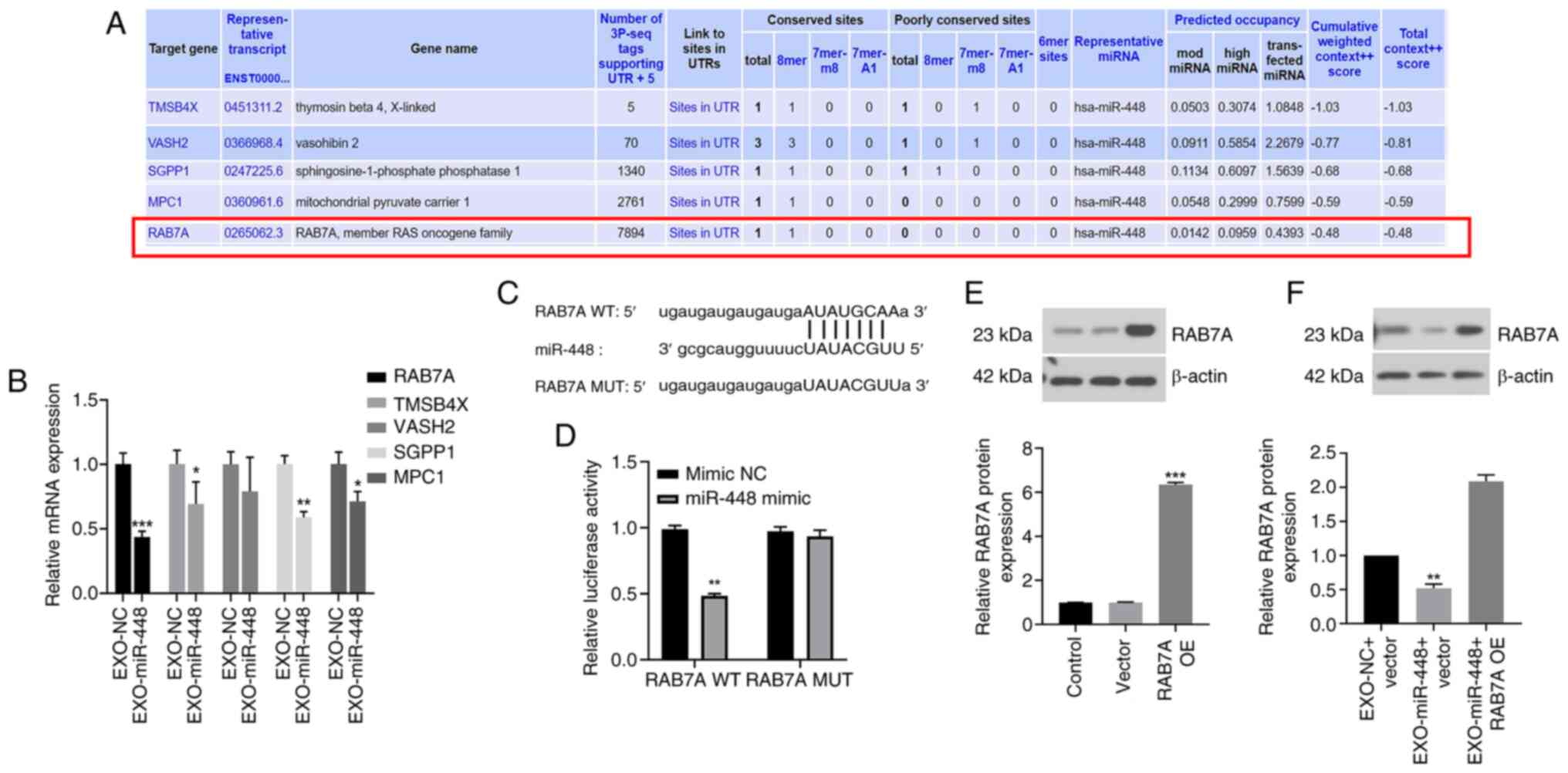

RAB7A is a direct downstream target of

EXO-miR-448 in liver cancer cells

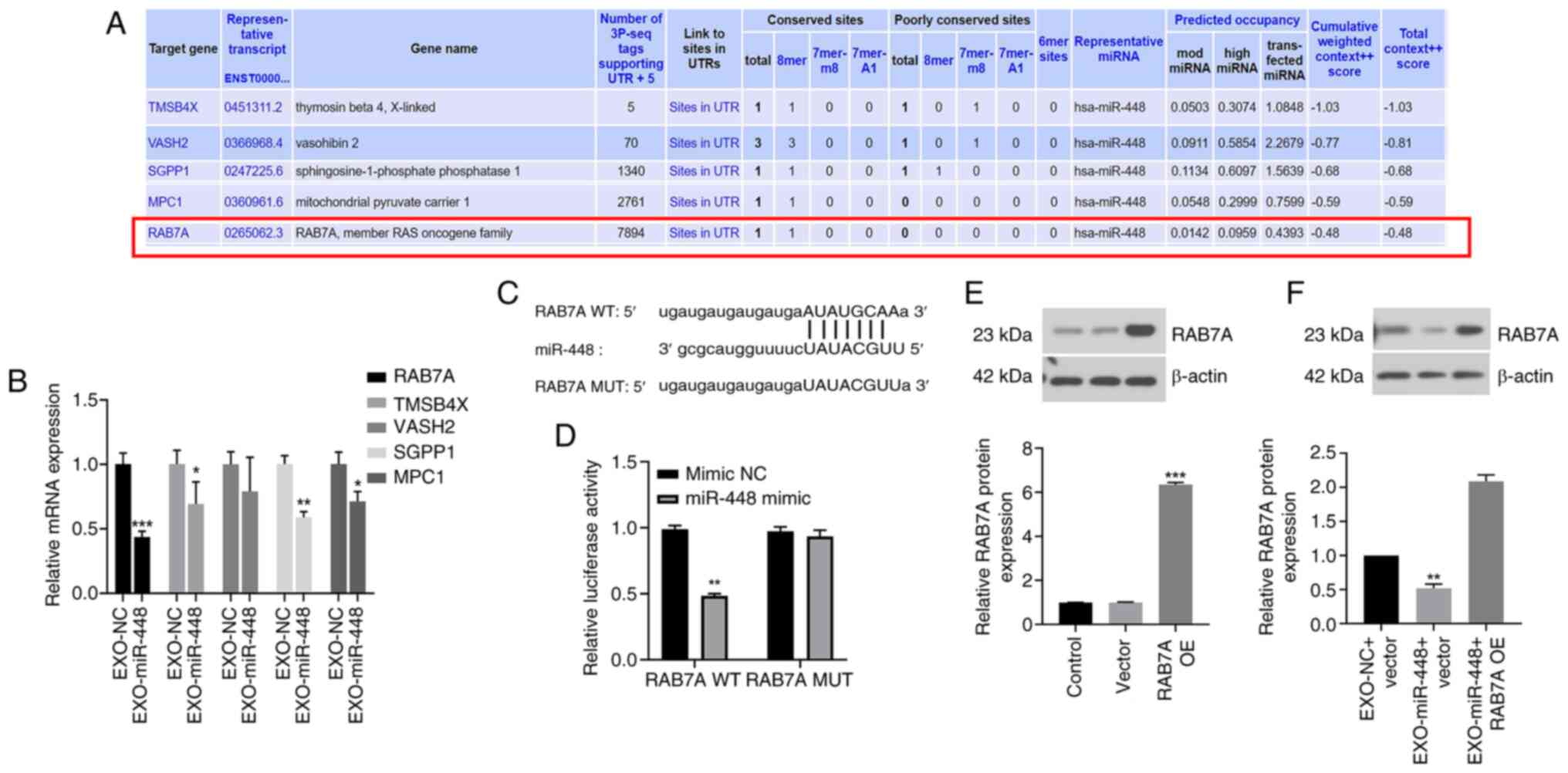

To identify the downstream targets of miR-448,

bioinformatics analysis was performed and several potential target

genes were predicted, including RAB7A, TMS4BX, VASH2, SGPP1 and

MPC1, all of which exhibited relatively high binding scores

(Fig. 3A). To further concentrate

the candidates, RT-qPCR was performed in liver cancer cells treated

with EXO-miR-448 or EXO-NC to evaluate the mRNA expression levels

of these predicted targets. Although all five genes showed a modest

decrease following EXO-miR-448 treatment, RAB7A demonstrated the

most significant downregulation (Fig.

3B). According to previous studies, RAB7A is associated with

exosome trafficking, suggesting its potential functional relevance

(20,27,28).

Based on these findings, RAB7A was selected as the putative target

of miR-448 for further investigation. The predicted binding site of

miR-448 on the 3′-UTR of RAB7A is presented in Fig. 3C. A dual-luciferase reporter assay

demonstrated that transfection with miR-448 mimics significantly

decreased the luciferase activity of the RAB7A WT reporter

construct, indicating a direct interaction between miR-448 and

RAB7A (Fig. 3D). To confirm the

efficiency of RAB7A OE, western blot analysis was performed in

cells transfected with the RAB7A OE construct alone. The results

demonstrated a significant increase in RAB7A protein levels

compared with those in the vector group (Fig. 3E), confirming successful

transfection. Furthermore, treatment with EXO-miR-448 suppressed

RAB7A protein expression compared with that in the EXO-NC + vector

group (Fig. 3F).

| Figure 3.RAB7A as a direct downstream target

of miR-448 in liver cancer. (A) Bioinformatics analysis predicted

potential downstream targets of miR-448, including RAB7A, TMSB4X,

VASH2, SGPP1 and MPC1. (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of

candidate targets in HepG2 cells treated with EXO-miR-448 or

EXO-NC, assessed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC. (C) Predicted

binding sites of miR-448 in the 3′-UTR of RAB7A (WT and MUT). (D)

Dual-luciferase reporter assay validating the interaction between

miR-448 and RAB7A. **P<0.01 vs. mimic NC. (E) Western blotting

showing markedly increased RAB7A protein levels in HepG2 cells

transfected with the RAB7A OE construct alone. ***P<0.001 vs.

vector. (F) Western blotting showing reduced RAB7A protein levels

in HepG2 cells after EXO-miR-448 treatment. **P<0.01 vs. EXO-NC

+ vector. EXO, exosomal; miR, microRNA; MPC1, mitochondrial

pyruvate carrier 1; MUT, mutant; NC, negative control; OE,

overexpression; RAB7A, Ras-related protein Rab-7a; SGPP1,

sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphatase 1; TMSB4X, thymosin β 4

X-linked; VASH2, vasohibin 2; WT, wild-types. |

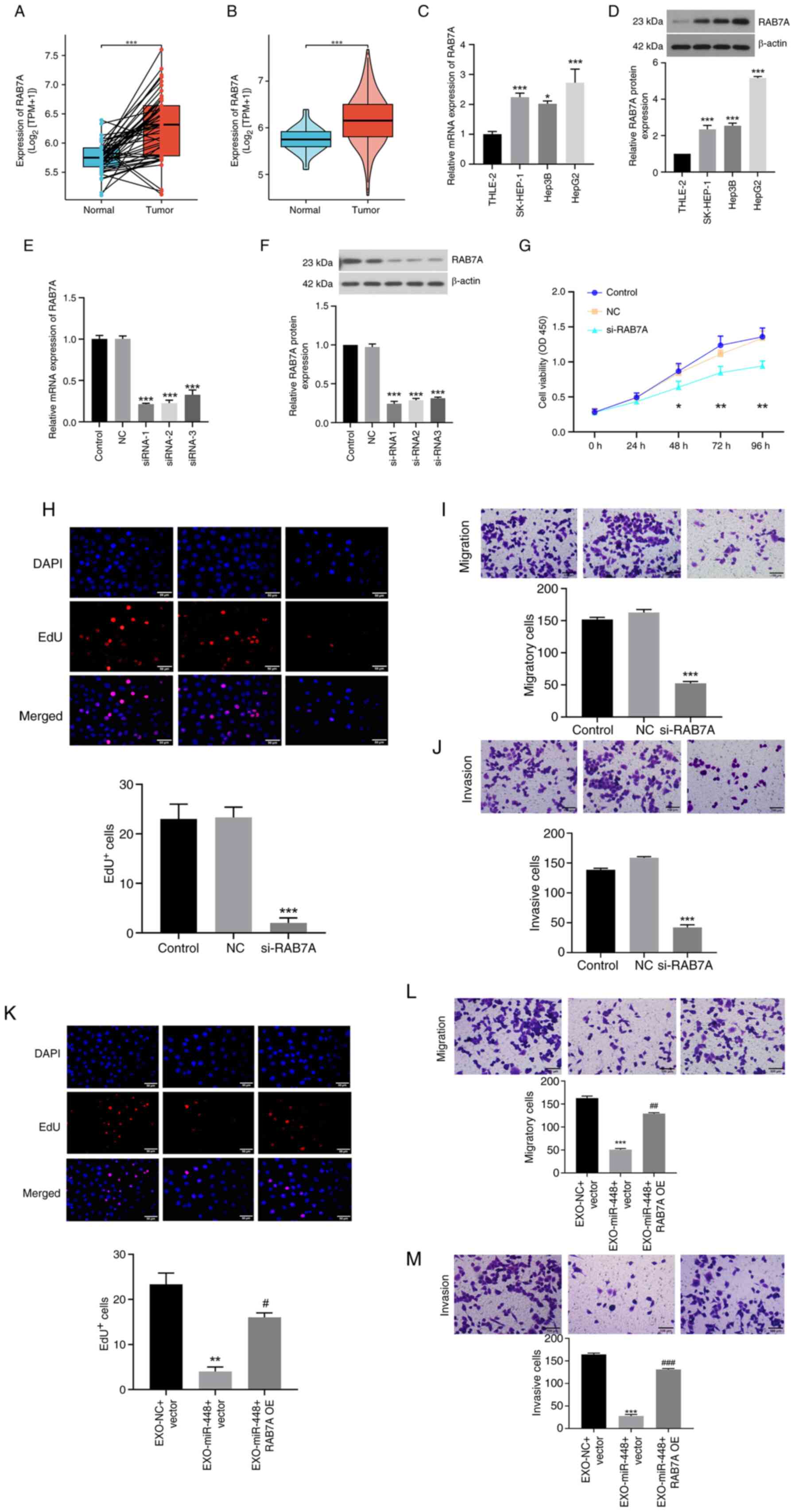

EXO-miR-448 inhibits liver cancer cell

proliferation, migration and invasion by targeting RAB7A

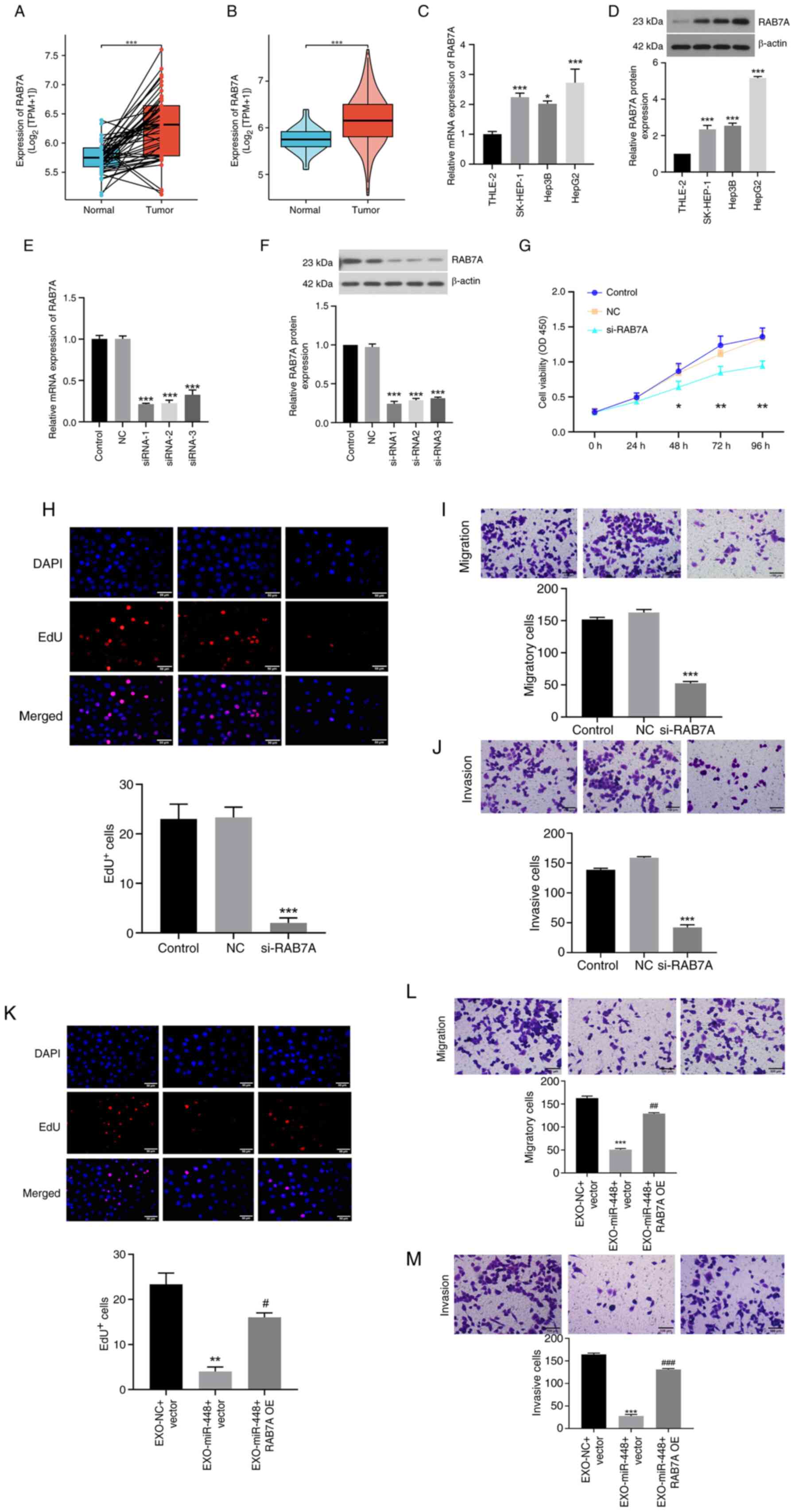

To further assess the functional role of EXO-miR-448

in liver cancer, its downstream target gene RAB7A was analyzed.

Data from TCGA indicated that RAB7A expression was significantly

higher in HCC tissues compared with that in normal liver tissues,

consistent with the present hypothesis that RAB7A serves a key role

in liver cancer progression (Fig. 4A

and B). Furthermore, western blotting and RT-qPCR analysis

demonstrated that RAB7A expression was significantly upregulated in

different liver cancer cells compared with in THLE-2 normal liver

cells (Fig. 4C and D). To assess

this, RAB7A expression was silenced in liver cancer cells using

siRNA targeting RAB7A, and successful knockdown was confirmed using

RT-qPCR and western blotting (Fig. 4E

and F). Subsequently, the biological effects of RAB7A silencing

on liver cancer cells were evaluated. The results revealed that

RAB7A knockdown significantly reduced cell proliferation, migration

and invasion, as assessed using CCK-8, EdU and Transwell migration

and invasion assays, respectively (Fig.

4G-J).

| Figure 4.EXO-miR-448 inhibits liver cancer

cell proliferation, migration and invasion by targeting RAB7A. (A)

Paired comparison of RAB7A expression between HCC tumor tissues and

their matched adjacent normal tissues (n=50 pairs). ***P<0.001.

(B) Unpaired comparison of all HCC tumor samples (n=424) vs. normal

liver tissues (n=50). ***P<0.001. (C) RAB7A mRNA expression in

normal liver cells (THLE-2) and liver cancer cell lines (HepG2,

Hep3B and SK-HEP-1). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. THLE-2. (D)

RAB7A protein expression in normal liver cells (THLE-2) and liver

cancer cell lines (HepG2, Hep3B and SK-HEP-1). ***P<0.001 vs.

THLE-2. (E) Validation of RAB7A knockdown efficiency in HepG2 cells

using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. ***P<0.001 vs. NC.

(F) Validation of RAB7A knockdown efficiency in HepG2 cells using

western blotting. ***P<0.001 vs. NC. (G) Cell Counting Kit-8

assay showing reduced proliferation of HepG2 cells after RAB7A

knockdown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. NC. (H) EdU assay showing

reduced proliferation of HepG2 cells after RAB7A knockdown (scale

bar, 50 µm). ***P<0.001 vs. NC. (I) Transwell migration assay

showing suppressed migratory ability of HepG2 cells following RAB7A

knockdown (scale bar, 100 µm). ***P<0.001 vs. NC. (J) Transwell

invasion assay showing suppressed invasive ability of HepG2 cells

following RAB7A knockdown (scale bar, 100 µm). ***P<0.001 vs.

NC. (K) Rescue experiment showing that RAB7A OE reverses the

inhibitory effect of EXO-miR-448 on HepG2 cell proliferation. scale

bar, 50 µm. **P<0.01 vs. EXO-NC + vector; #P<0.05

vs. EXO-miR-448 + vector. (L) Rescue experiment showing that RAB7A

OE reverses the inhibitory effect of EXO-miR-448 on HepG2 cell

migration. Scale bar, 100 µm. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC + vector;

##P<0.01 vs. EXO-miR-448 + vector. (M) Rescue

experiment showing that RAB7A OE reverses the inhibitory effect of

EXO-miR-448 on HepG2 cell invasion. Scale bar, 100 µm.

***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC + vector; ###P<0.001 vs.

EXO-miR-448 + vector. EXO, exosomal; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma;

miR, microRNA; NC, negative control; OE, overexpression; RAB7A,

Ras-related protein Rab-7a; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TPM,

transcripts per million. |

To further explore the impact of EXO-miR-448 on

RAB7A-regulated cell behavior, RAB7A was overexpressed in liver

cancer cells and the results demonstrated that RAB7A OE rescued the

inhibitory effects of EXO-miR-448 on cell proliferation, migration

and invasion (Fig. 4K-M). These

findings suggested that EXO-miR-448 may suppress liver cancer cell

proliferation, migration and invasion by directly targeting

RAB7A.

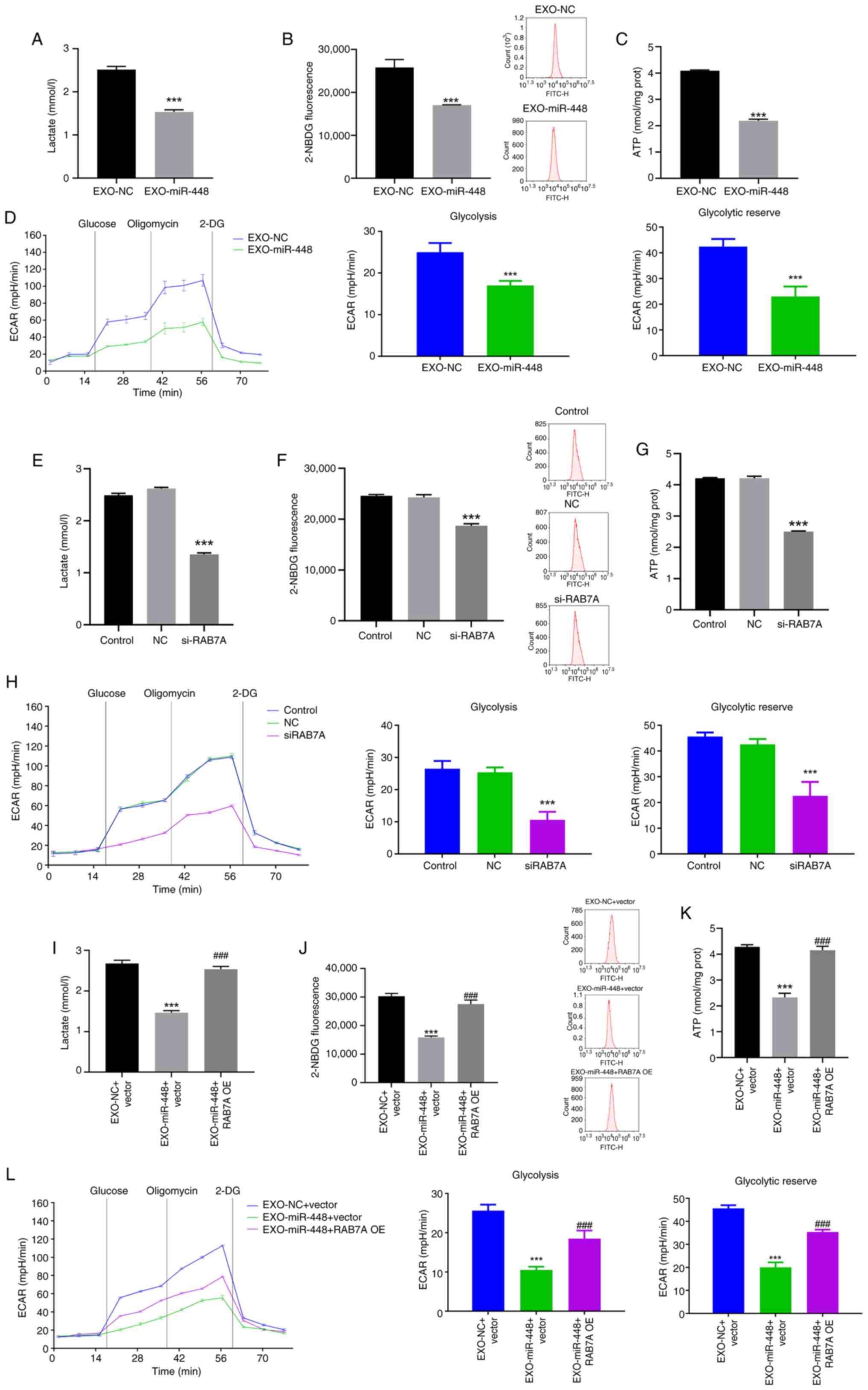

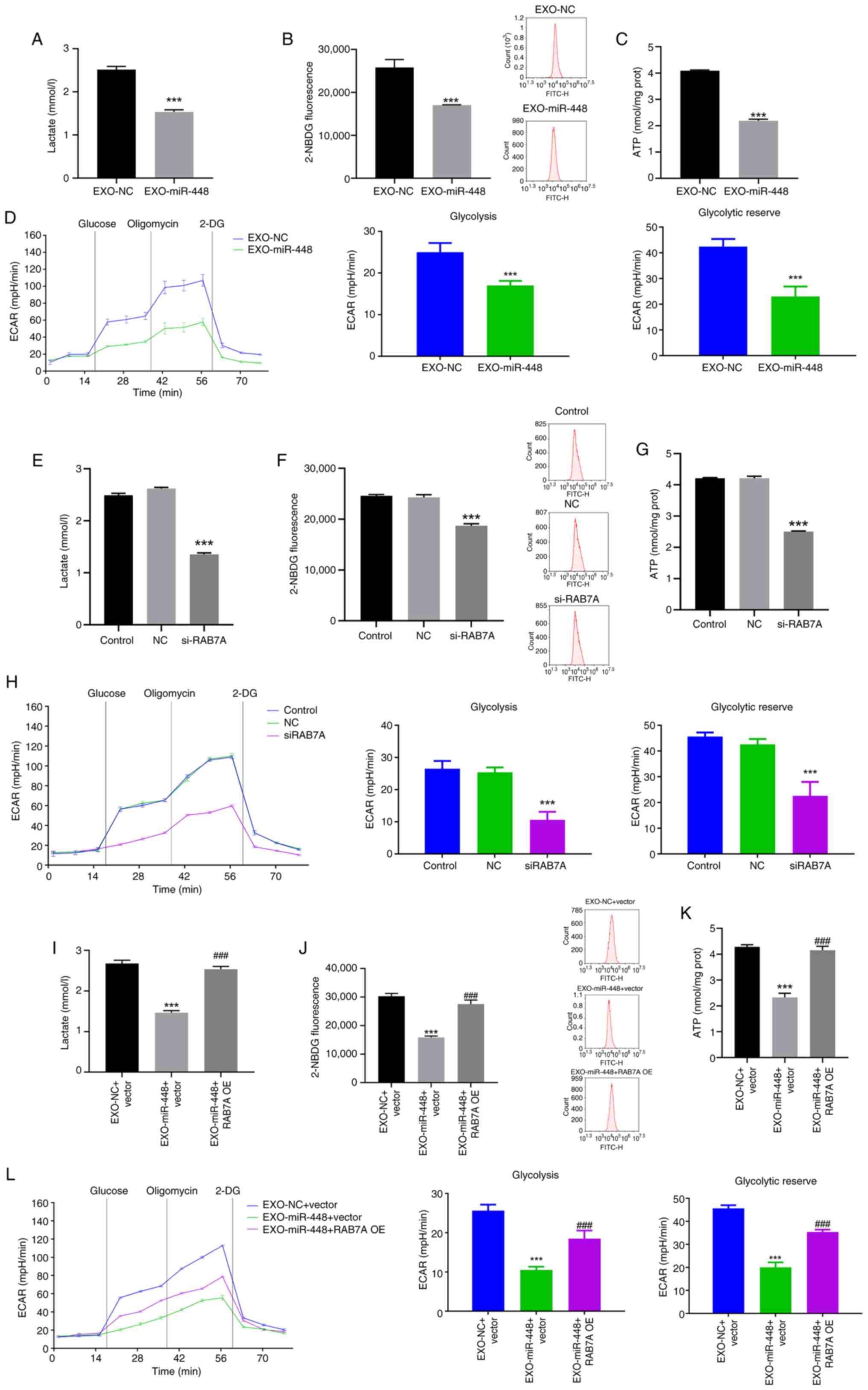

EXO-miR-448 inhibits glycolysis in

liver cancer cells by targeting RAB7A

To further investigate the mechanism through which

EXO-miR-448 affects liver cancer progression, the potential role of

RAB7A in regulating glycolysis was explored in liver cancer cells.

Glycolysis is a key metabolic pathway that is often upregulated in

cancer cells, including liver cancer, to support rapid cell

proliferation and metastasis (29,30).

To evaluate the effect of EXO-miR-448 on glycolysis in liver cancer

cells, HepG2 cells were treated with EXO-miR-448.

Glycolysis-associated indicators, including lactate production,

glucose uptake and ATP levels, were significantly decreased

following EXO-miR-448 treatment (Fig.

5A-C). Furthermore, ECAR, an indicator of glycolytic activity

and capacity, was markedly reduced upon EXO-miR-448 exposure

(Fig. 5D), further supporting the

inhibitory effect of EXO-miR-448 on glycolysis in liver cancer

cells. Furthermore, silencing RAB7A expression using siRNA resulted

in a similar decrease in glycolytic activity, including

significantly reduced lactate production, ATP levels, glucose

uptake and ECAR, suggesting that RAB7A is involved in the

regulation of glycolysis (Fig.

5E-H). Notably, RAB7A OE reversed the inhibitory effects of

EXO-miR-448 on glycolysis, as demonstrated by the significant

restoration of lactate production, glucose uptake, ATP levels and

ECAR (Fig. 5I-L). Overall, the

findings indicated that EXO-miR-448 may regulate glycolysis in

liver cancer cells through the direct targeting of RAB7A and this

mechanism may contribute to the antitumor effects of miR-448 in

liver cancer.

| Figure 5.EXO-miR-448 suppresses liver cancer

progression by targeting RAB7A to inhibit glycolysis. (A) Lactate

production in HepG2 cells treated with EXO-miR-448 or EXO-NC,

determined by a colorimetric assay. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC. (B)

Glucose uptake in HepG2 cells treated with EXO-miR-448 or EXO-NC,

assessed using the 2-NBDG assay. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC. (C)

Intracellular ATP levels in HepG2 cells treated with EXO-miR-448 or

EXO-NC, determined using an ATP assay kit. ***P<0.001 vs.

EXO-NC. (D) ECAR in HepG2 cells treated with EXO-miR-448 or EXO-NC,

measured using a Seahorse XF Analyzer. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC.

(E) Lactate production in HepG2 cells transfected with si-RAB7A or

control siRNA. ***P<0.001 vs. NC. (F) Glucose uptake in HepG2

cells transfected with si-RAB7A or control siRNA. ***P<0.001 vs.

NC. (G) Intracellular ATP levels in HepG2 cells transfected with

si-RAB7A or control siRNA. ***P<0.001 vs. NC. (H) ECAR in HepG2

cells transfected with si-RAB7A or control siRNA. ***P<0.001 vs.

NC. (I) Lactate production in HepG2 cells following EXO-miR-448

treatment with or without RAB7A OE. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC +

vector; ###P<0.001 vs. EXO-miR-448 + vector. (J)

Glucose uptake in HepG2 cells following EXO-miR-448 treatment with

or without RAB7A OE. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC + vector;

###P<0.001 vs. EXO-miR-448 + vector. (K) ATP levels

in HepG2 cells following EXO-miR-448 treatment with or without

RAB7A OE. ***P<0.001 vs. EXO-NC + vector;

###P<0.001 vs. EXO-miR-448 + vector. (L) ECAR

analysis showing glycolytic activity in HepG2 cells following

EXO-miR-448 treatment with or without RAB7A OE. ***P<0.001 vs.

EXO-NC + vector; ###P<0.001 vs. EXO-miR-448 + vector.

miR, microRNA; NC, negative control; ECAR, extracellular

acidification rate; si, small interfering RNA; RAB7A, Ras-related

protein Rab-7a; NBDG,

N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose; EXO,

exosomal; OE, overexpression; 2-DG, 2-deoxy-D-glucose. |

Discussion

Liver cancer remains one of the most aggressive

malignancies. As HCC accounts for 75–85% of primary liver cancer

cases, its clinical characteristics largely define the behavior of

liver cancer. Notably, the 5-year recurrence rate of HCC after

curative resection reaches 40–70%, and long-term survival remains

poor, underscoring its high recurrence, metastatic potential and

resistance to therapy (31–33). Despite advancements in targeted

therapies, prognosis remains poor due to the complexity of its

pathogenesis and the lack of effective early detection methods

(34,35). Altered metabolism, particularly the

upregulation of glycolysis (the Warburg effect), is a hallmark of

cancer cells and enables them to meet the bioenergetic and

biosynthetic demands of rapid proliferation and metastasis, a

feature particularly prominent in liver cancer (36). The aim of the present study was to

assess the role of EXO-miR-448 in liver cancer progression,

focusing on its potential to target RAB7A and regulate

glycolysis.

The results of the present study demonstrated that

miR-448 was significantly downregulated in liver cancer cell lines

compared with in normal liver cells, consistent with previous

studies demonstrating reduced miR-448 expression in HCC tissues and

its association with hepatocarcinogenesis (9,37).

miRNAs can be actively exported via extracellular vesicles, with

exosomes serving as predominant carriers for intercellular transfer

of bioactive molecules (38).

Aberrant expression levels of exosomal miRNAs have been implicated

in multiple malignancies, including lung, breast, colorectal,

liver, gastric and pancreatic cancer, where they regulate key

tumor-associated processes such as proliferation, angiogenesis,

metastasis and chemoresistance (39). The present study revealed that

miR-448 was markedly packaged into exosomes derived from HepG2

cells. Functionally, miR-448 has been recognized as a tumor

suppressor in several cancer types (40,41),

including non-small-cell lung cancer, where it targets sirtuin 1 to

inhibit proliferation, migration and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (42). Consistently, the

results of the present study indicated that EXO-miR-448 may

suppress the proliferation, migration and invasion of liver cancer

cells.

A key finding of the present study was that miR-448

targets RAB7A, a small GTPase involved in endosomal maturation,

autophagy and intracellular trafficking. Beyond its role in

vesicular trafficking and autophagy, RAB7A has been reported to

promote tumor metastasis through multiple mechanisms in different

malignancies. In HCC, RAB7A OE activates the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway and induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition, thereby

enhancing migration and invasion (43). In breast cancer, RAB7A knockdown

significantly suppresses proliferation, migration and xenograft

tumor growth, confirming its essential contribution to metastatic

behavior (44). In melanoma, RAB7A

interacts with the endolysosomal channel two pore segment channel 2

to modulate the GSK-3β/β-catenin/microphthalmia-associated

transcription factor axis, which drives invasive growth and distant

metastasis (45). In colon

adenocarcinoma, elevated RAB7A expression has been reported to be

associated with increased tumor size, invasion depth, lymph node

metastasis and poor overall survival (22). Furthermore, RAB7A upregulation by

oncogenic miR-3200 has been reported to promote telomere remodeling

and activate mTOR and autophagy-associated pathways, further

supporting its role as a facilitator of malignant progression and

dissemination in liver cancer (46). Using dual-luciferase reporter

assays, the results of the present study demonstrated that miR-448

can bind to the 3′-UTR of RAB7A, and EXO-miR-448 treatment was

further shown to significantly reduce RAB7A mRNA and protein

expression. Functional assays further revealed that RAB7A knockdown

significantly suppressed cell proliferation, migration and

invasion, whereas RAB7A OE rescued the inhibitory effects of

EXO-miR-448, indicating that suppression of RAB7A is a key

mechanism by which EXO-miR-448 exerts its tumor-suppressive effects

in liver cancer.

Notably, the present study revealed that EXO-miR-448

may inhibit glycolysis in liver cancer cells, as demonstrated by

significantly reduced lactate production, glucose uptake, ATP

levels and ECAR. Consistently, a previous study reported that

miR-448 suppresses HCC cell viability and glycolytic activity by

directly targeting insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, leading

to decreased glucose uptake, lactate production and ATP generation

(47). In the present study,

silencing RAB7A produced similar effects, supporting its role as a

mediator of EXO-miR-448 driven metabolic suppression. Furthermore,

RAB7A OE reversed the inhibitory effects of EXO-miR-448 on

glycolysis, restoring lactate production, glucose uptake, ATP

levels and ECAR, thereby further demonstrating the functional

association between miR-448 and RAB7A in regulating cancer cell

metabolism. These findings are further supported by previous

studies that demonstrated RAB7A enhances aerobic glycolysis and

yes-associated protein 1-driven transcriptional activity to promote

HCC growth and metastasis (25,48,49).

Furthermore, mechanistic evidence from lipopolysaccharide-activated

macrophages indicates that phosphorylation of RAB7A at Ser72

disrupts EGFR endocytosis and sustains glycolytic flux via the

pyruvate kinase M2/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α pathway, while

disruptions in vesicular trafficking have similarly been reported

to alter cellular energy metabolism (50). Notably, RAB7A dysregulation among

autophagy-associated genes affected by vacuolar protein sorting 51

deficiency can lead to enhanced glycolysis and impaired oxidative

phosphorylation (51). Overall, the

ability of RAB7A to coordinate vesicular trafficking, autophagy,

nutrient sensing and metabolic stress adaptation may underlie its

dual regulatory roles in tumor metabolism and metastatic

progression (23,52,53).

Recent studies have further highlighted the

intersection of glycolysis, exosome biology and RAB7A in cancer.

Lactate accumulation has been reported to drive HCC metastasis by

enhancing exosome biogenesis via RAB7A lactylation, thereby

associating glycolytic metabolism with RAB7A-mediated vesicular

trafficking (54). Furthermore,

bone marrow stromal cell-derived exosomal miR-196a-5p has been

reported to suppress glycolysis and leukemia progression by

targeting 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3,

underscoring the role of exosome-delivered miRNAs in metabolic

regulation (55). The findings of

the present study fit within this framework, identifying miR-448 as

a novel regulator that inhibits RAB7A-mediated glycolysis via

exosomal delivery, thereby attenuating liver cancer.

Nevertheless, the present study had certain

limitations. For example, it is limited by its exclusive use of

in vitro assays. While RAB7A OE rescue experiments

strengthen the functional interpretation of the miR-448/RAB7A axis,

the lack of in vivo validation precludes direct conclusions

regarding therapeutic efficacy. Future research should incorporate

animal models or patient-derived xenografts to confirm in

vivo relevance and explore the translational potential of

miR-448 mimics or RAB7A inhibitors in liver cancer.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

revealed that EXO-miR-448 may inhibit glycolysis and suppress

malignant phenotypes in liver cancer cells by directly targeting

RAB7A. These findings provide novel mechanistic insights into

miRNA-mediated metabolic regulation in liver cancer and suggest

that modulation of the miR-448/RAB7A axis could be a potential

therapeutic approach, pending validation in in vivo models

in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82260125), the Zhongyuan Thousand

Talent Program-Youth Outstanding Talent (grant no. 2018), the

Research Program of the Education Department of Henan Province

(grant no. 21A320001), the Research Program of the Health

Commission of Henan Province (grant no. YXKC2020043) and the Hainan

Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos.

822QN473, 822MS181 and 823RC591).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC, ZW, FC and WL contributed to the present study

conception and design, prepared materials, collected and analyzed

the data. YC and QW wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and QW

also participated in data organization and statistical analysis.

HW, TZ and MN substantially contributed to the acquisition,

analysis and interpretation of experimental data. ZW and WL confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The use of commercially obtained human cell lines

was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated

Hospital of Hainan Medical University (Haikou, China) and all

procedures were performed in accordance with institutional

guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Marengo A, Rosso C and Bugianesi E: Liver

cancer: Connections with obesity, fatty liver, and cirrhosis. Annu

Rev Med. 67:103–117. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hoshida Y, Fuchs BC, Bardeesy N, Baumert

TF and Chung RT: Pathogenesis and prevention of hepatitis C

virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 61 (Suppl

1):S79–S90. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Alawyia B and Constantinou C:

Hepatocellular carcinoma: A narrative review on current knowledge

and future prospects. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 24:711–724. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Khameneh SC, Razi S, Lashanizadegan R,

Akbari S, Sayaf M, Haghani K and Bakhtiyari S: MicroRNA-mediated

metabolic regulation of immune cells in cancer: An updated review.

Front Immunol. 15:14249092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

He L and Hannon GJ: MicroRNAs: Small RNAs

with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 5:522–531. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Target recognition

and regulatory functions. Cell. 136:215–233. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xu X, Li Y, Zhang R, Chen X, Shen J, Yuan

M, Chen Y, Chen M, Liu S, Wu J and Sun Q: Jianpi Yangzheng

decoction suppresses gastric cancer progression via modulating the

miR-448/CLDN18.2 mediated YAP/TAZ signaling. J Ethnopharmacol.

311:1164502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhu H, Zhou X, Ma C, Chang H, Li H, Liu F

and Lu J: Low expression of miR-448 induces EMT and promotes

invasion by regulating ROCK2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 36:487–498. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lin Z, Zhu Y and Liu Y: The role of

miR-448 in cancer progression and its potential therapeutic

applications. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 143:679–687. 2017.

|

|

11

|

Jiang X, Zhou Y, Sun AJ and Xue JL: NEAT1

contributes to breast cancer progression through modulating miR-448

and ZEB1. J Cell Physiol. 233:8558–8566. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou Y, Lin F, Wan T, Chen A, Wang H,

Jiang B, Zhao W, Liao S, Wang S, Li G, et al: ZEB1 enhances Warburg

effect to facilitate tumorigenesis and metastasis of HCC by

transcriptionally activating PFKM. Theranostics. 11:5926–5938.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang J, Ouyang F, Gao A, Zeng T, Li M, Li

H, Zhou W, Gao Q, Tang X, Zhang Q, et al: ESM1 enhances fatty acid

synthesis and vascular mimicry in ovarian cancer by utilizing the

PKM2-dependent Warburg effect within the hypoxic tumor

microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 23:942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jing Z, Liu Q, He X, Jia Z, Xu Z, Yang B

and Liu P: NCAPD3 enhances Warburg effect through c-myc and E2F1

and promotes the occurrence and progression of colorectal cancer. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:1982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Peng L, Zhao Y, Tan J, Hou J, Jin X, Liu

DX, Huang B and Lu J: PRMT1 promotes Warburg effect by regulating

the PKM2/PKM1 ratio in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis.

15:5042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Paul S, Ghosh S and Kumar S: Tumor

glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer

Biol. 86:1216–1230. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lan F, Qin Q, Yu H and Yue X: Effect of

glycolysis inhibition by miR-448 on glioma radiosensitivity. J

Neurosurg. 132:1456–1464. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Luce A, Lombardi A, Ferri C, Zappavigna S,

Tathode MS, Miles AK, Boocock DJ, Vadakekolathu J, Bocchetti M,

Alfano R, et al: A proteomic approach reveals that miR-423-5p

modulates glucidic and amino acid metabolism in prostate cancer

cells. Int J Mol Sci. 24:6172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chu M, Zhao Y, Feng Y, Zhang H, Liu J,

Cheng M, Li L, Shen W, Cao H, Li Q and Min L: MicroRNA-126

participates in lipid metabolism in mammary epithelial cells. Mol

Cell Endocrinol. 454:77–86. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Guerra F and Bucci C: Role of the RAB7

protein in tumor progression and cisplatin chemoresistance. Cancers

(Basel). 11:10962019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ju L, Luo Y, Cui X, Zhang H, Chen L and

Yao M: CircGPC3 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression and

metastasis by sponging miR-578 and regulating RAB7A/PSME3

expression. Sci Rep. 14:76322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shan Z, Chen X, Chen H and Zhou X:

Investigating the impact of Ras-related protein RAB7A on colon

adenocarcinoma behavior and its clinical significance. Biofactors.

51:e700062025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu Q, Bai Y, Shi X, Guo D, Wang Y, Wang

Y, Guo WZ and Zhang S: High RAS-related protein Rab-7a (RAB7A)

expression is a poor prognostic factor in pancreatic

adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 12:174922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Güleç Taşkıran AE, Hüsnügil HH, Soltani

ZE, Oral G, Menemenli NS, Hampel C, Huebner K, Erlenbach-Wuensch K,

Sheraj I, Schneider-Stock R, et al: Post-transcriptional regulation

of Rab7a in lysosomal positioning and drug resistance in

nutrient-limited cancer cells. Traffic. 25:e129562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang JY, Zhu X, Liu Y and Wu X: The

prognostic biomarker RAB7A promotes growth and metastasis of liver

cancer cells by regulating glycolysis and YAP1 activation. J Cell

Biochem. 125:e306212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget

I, Raposo G, Savina A, Moita CF, Schauer K, Hume AN, Freitas RP, et

al: Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome

secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 12:19–30. 1–13. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mulligan RJ and Winckler B: Regulation of

endosomal trafficking by Rab7 and its effectors in neurons: Clues

from charcot-marie-tooth 2B disease. Biomolecules. 13:13992023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Feng J, Li J, Wu L, Yu Q, Ji J, Wu J, Dai

W and Guo C: Emerging roles and the regulation of aerobic

glycolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

39:1262020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wen T, Jin C, Facciorusso A, Donadon M,

Han HS, Mao Y, Dai C, Cheng S, Zhang B, Peng B, et al:

Multidisciplinary management of recurrent and metastatic

hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: An international expert

consensus. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 7:353–371. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Abdelhamed W and El-Kassas M:

Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence: Predictors and management.

Liver Res. 7:321–332. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shin H and Yu SJ: A concise review of

updated global guidelines for the management of hepatocellular

carcinoma: 2017–2024. J Liver Cancer. 25:19–30. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal

AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J and

Finn RS: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:62021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yang F, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Shaha A, Wang

Y, Wang X, Deng Y, Lai J and Kang N: Metabolic reprogramming and

its clinical implication for liver cancer. Hepatology.

78:1602–1624. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Katayama Y, Maeda M, Miyaguchi K, Nemoto

S, Yasen M, Tanaka S, Mizushima H, Fukuoka Y, Arii S and Tanaka H:

Identification of pathogenesis-related microRNAs in hepatocellular

carcinoma by expression profiling. Oncol Lett. 4:817–823. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pegtel DM and Gould SJ: Exosomes. Annu Rev

Biochem. 88:487–514. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li B, Cao Y, Sun M and Feng H: Expression,

regulation, and function of exosome-derived miRNAs in cancer

progression and therapy. FASEB J. 35:e219162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wu X, Tang H, Liu G, Wang H, Shu J and Sun

F: miR-448 suppressed gastric cancer proliferation and invasion by

regulating ADAM10. Tumour Biol. 37:10545–10551. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Bamodu OA, Huang WC, Lee WH, Wu A, Wang

LS, Hsiao M, Yeh CT and Chao TY: Aberrant KDM5B expression promotes

aggressive breast cancer through MALAT1 overexpression and

downregulation of hsa-miR-448. BMC Cancer. 16:1602016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Qi H, Wang H and Pang D: miR-448 promotes

progression of non-small-cell lung cancer via targeting SIRT1. Exp

Ther Med. 18:1907–1913. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liu Y, Ma J, Wang X, Liu P, Cai C, Han Y,

Zeng S, Feng Z and Shen H: Lipophagy-related gene RAB7A is involved

in immune regulation and malignant progression in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 158:1068622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xie J, Yan Y, Liu F, Kang H, Xu F, Xiao W,

Wang H and Wang Y: Knockdown of Rab7a suppresses the proliferation,

migration, and xenograft tumor growth of breast cancer cells.

Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201804802019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Abrahamian C, Tang R, Deutsch R, Ouologuem

L, Weiden EM, Kudrina V, Blenninger J, Rilling J, Feldmann C, Kuss

S, et al: Rab7a is an enhancer of TPC2 activity regulating melanoma

progression through modulation of the GSK3β/β-Catenin/MITF-axis.

Nat Commun. 15:100082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Song S, Xie S, Liu X, Li S, Wang L, Jiang

X and Lu D: miR-3200 accelerates the growth of liver cancer cells

by enhancing Rab7A. Noncoding RNA Res. 8:675–685. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Y, Chen X, Yao N, Gong J, Cao Y, Su

X, Feng X and Tao M: MiR-448 suppresses cell proliferation and

glycolysis of hepatocellular carcinoma through inhibiting IGF-1R

expression. J Gastrointest Oncol. 13:355–367. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Qi C, Zou L, Wang S, Mao X, Hu Y, Shi J,

Zhang Z and Wu H: Vps34 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma invasion

by regulating endosome-lysosome trafficking via Rab7-RILP and

Rab11. Cancer Res Treat. 54:182–198. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yang CC, Meng GX, Dong ZR and Li T: Role

of Rab GTPases in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma.

8:1389–1397. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang X, Chen C, Ling C, Luo S, Xiong Z,

Liu X, Liao C, Xie P, Liu Y, Zhang L, et al: EGFR tyrosine kinase

activity and Rab GTPases coordinate EGFR trafficking to regulate

macrophage activation in sepsis. Cell Death Dis. 13:9342022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Aygun D and Yücel Yılmaz D: From gene to

pathways: Understanding novel Vps51 variant and its cellular

consequences. Int J Mol Sci. 26:57092025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Edinger AL, Cinalli RM and Thompson CB:

Rab7 prevents growth factor-independent survival by inhibiting

cell-autonomous nutrient transporter expression. Dev Cell.

5:571–582. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Deffieu MS, Cesonyte I, Delalande F,

Boncompain G, Dorobantu C, Song E, Lucansky V, Hirschler A,

Cianferani S, Perez F, et al: Rab7-harboring vesicles are carriers

of the transferrin receptor through the biosynthetic secretory

pathway. Sci Adv. 7:eaba78032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Jiang C, He X, Chen X, Huang J, Liu Y,

Zhang J, Chen H, Sui X, Lv X, Zhao X, et al: Lactate accumulation

drives hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through facilitating

tumor-derived exosome biogenesis by Rab7A lactylation. Cancer Lett.

627:2176362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Fan B, Wang L, Hu T, Zheng L and Wang J:

Exosomal miR-196a-5p secreted by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

inhibits ferroptosis and promotes drug resistance of acute myeloid

leukemia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 42:933–953. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|