Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common

cancer in female patients worldwide, with an estimated incidence of

662,301 novel cases and 348,874 deaths in 2022 (1,2). It

has been reported that ~90% of CC deaths occur in low- and

middle-income countries and are primarily associated with delayed

diagnosis and failure to deliver guideline-concordant treatment in

the advanced stages of CC (3).

According to the International Federation of

Gynecology and Obstetrics classification system, the treatment of

invasive CC depends on clinical evaluation and histopathological

characteristics of tumors (4).

However, some patients do not respond to the treatment chosen based

on these criteria, highlighting the need to find predictive

biomarkers to lower the risk of disease recurrence or metastasis

(5). Furthermore, the

identification of genetic and epigenetic alterations associated

with therapy resistance may increase survival in patients with

locally advanced (LA)CC (5).

SET domain-containing protein 2 (SETD2) is a tumor

suppressor associated with the trimethylation of lysine 36 on

histone 3 (H3K36me3), a histone mark primarily associated with

actively transcribed regions. Loss of function of SETD2 due to

deletion or mutation is frequently detected in hematological and

solid tumors, such as renal, lung, colon and breast cancer and CC

(6). Furthermore, SETD2 mutations

are associated with acquired chemoradiotherapy (CRT) resistance and

poor survival due to alterations in mechanisms associated with DNA

damage repair and tumor heterogeneity mediated by chromatin

instability (7).

The increased risk of CRT resistance associated with

the loss of SETD2 is associated with the increased activity of the

hedgehog (Hh) and Wnt/β-catenin pathways in patients with brain

cancer and osteosarcoma, respectively (7,8).

Additionally, abnormal Hh signaling is detected in multiple human

malignant tumors (9). In CC,

alterations in Hh signaling are frequently associated with an

increased risk of developing CRT, which may be associated with

tumor hypoxia (10–13). Furthermore, increased expression of

the glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (GLI1) protein, a

transcriptional activator of the Hh pathway, is associated with

chemoresistance in gynecological cancer (14). To the best of our knowledge,

however, the relationship between SETD2 and GLI1 protein levels has

not been investigated and their potential role as prognostic

markers in patients with LACC remains unknown.

The present study explored the relationship between

SETD2 and GLI1 based on their localization and protein levels using

immunohistochemical assays. In addition, the immunoreactivity

scores (IS) of SETD2 and GLI1, as well as the pathological

characteristics of tumors and survival indicators, were evaluated

to determine their potential utility as prognostic biomarkers in

patients with LACC.

Materials and methods

Patients and sample collection

The present retrospective study included 84

patients, aged 25–81 years, with histological results of squamous

cell cervical carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (ADC) and

adenosquamous cell carcinoma (ASC) who received treatment between

January 2016 and December 2018 at the National Cancer Institute

(México City, México). The inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Patients with a diagnosis of LACC [stage IB1-IVA; International

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2009] (15); ii) patients who underwent biopsy;

iii) patients who did not receive treatment before biopsy

(chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy or hormonal therapy) and

iv) patients who received concurrent treatment with cisplatin 40

mg/m2 weekly with external beam radiation therapy of 45

Gy. Patients with incomplete treatment schemes or other types of

primary cancer were excluded from the present study.

Treatment response was evaluated according to the

Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST; version 1.1)

(16). Patients with complete and

partial responses were defined as responders, whereas those with

stable or progressive disease were designated as

non-responders.

Sociodemographic and clinicopathological data were

collected from the medical files. Smoking was defined as

consumption of ≥2 cigarettes/week for ≥1 year at any point in their

lifetime; alcohol consumption was defined as alcohol intake >1

drink/day on average.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC staining was performed using formalin-fixed

tissue as described previously (17). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

tumor blocks were obtained from the Institutional Pathology Tissue

Bank between January 2024 and March 2024. Polyclonal antibodies

directed at the C-terminus of SETD2 (cat. no. HPA042451; 1:50;

Millipore Sigma) and GLI-1/GLI1 (cat no. C1; 1:50; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) were used for the IHC assays. The conditions

and antibody concentrations were previously validated in colon

adenocarcinoma tissue for GLI1 and in the human small intestine for

the SETD2 protein.

Two observers specializing in gynecological oncology

at the National Institute of Cancer independently evaluated and

scored immunoreactivity in a blinded manner. SETD2 and GLI1

expression were analyzed according to a previously described IS

(18). The percentage of

tumor-positive cells was graded as follows: 0, <5%; 1, 6–25%; 2,

26–50%; 3, 51–75% and 4, 76–100%. Positive cells (5%) were used as

the cut-off to define negative tumors. The intensity of the

immunoreactivity was scored as follows: 1, weak; 2, moderate and 3,

strong. The percentage of positive cells and intensity values were

multiplied to obtain the IS. Localization was categorized as

membranous, cytoplasmic, nuclear or a combination.

DNA extraction and human

papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from the tumor tissue

using the QIAamp DNA FFPE tissue kit (cat. no. 56404, Qiagen GmbH)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The integrity of

extracted DNA was evaluated by PCR amplification of the β-globin

gene using specific primers (forward: 5′GAAGAGCCAAGGACAGGTAC3′;

reverse: 5′CAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC3′ as described previously (19). Primers were synthesized at

Integrated DNA Technologies (San Diego, Ca, USA).

HPV sequences were detected and typed using the E6

nested multiplex PCR protocol (Table

SI) (20). PCR products were

analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels stained with GelRed

(Biotium, Inc.) and visualized using the iBright FL1500

documentation system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The HPV type

was determined by assessing the size of the amplified fragments.

DNA samples from HPV-positive HeLa and CaSki cell lines (American

Type Culture Collection), cultured in DMEM-F12 medium (GIBCO-BRL)

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5%

CO2 was used as positive controls, while a mixture

without DNA was used as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software (version 22; IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics are

presented as mean ± SD of ≥2 independent experimental repeats for

normally distributed values and median (25th and 75th percentiles)

for skewed variables. The unpaired Student's t-test, Mann-Whitney U

and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess quantitative

variables. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to evaluate

the correlation between SETD2 and GLI1 levels. Fisher's exact test

was used to evaluate differences between categorical variables.

Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were

estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method according to IS categories.

Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate the

hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs of the variables with OS and DFS.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Characteristics of the study

population

The overall sociodemographic characteristics of the

patients are shown in Table SII.

The median age was 46 years (range, 25–81 years). According to the

BMI, 52.4% (44/84) of participants were overweight or obese.

Alcohol and tobacco consumption were reported in 15.5% (13/84) and

27.4% (23/84) of patients, respectively. Hormonal contraception was

reported in 20.2% (17/84) of patients. According to

histopathological classification, 89.3% (75/84) of patients had

SCC, 7.1% (6/84) had ADC and 3.6% (3/84) had ASC (Table SIII). Based on the RECIST criteria,

the overall response rate was 92.9% (78/84). Additional

clinicopathological characteristics of the patients, such as the

FIGO classification, lymph node status and tumor differentiation,

are provided in Table SIII.

The distribution of the sociodemographic and

histopathological characteristics, categorized by SCC and non-SCC

(ADC + ASC) groups, revealed a significant difference in tumor

differentiation (Table SIV). Most

patients in the SCC group had moderately differentiated tumors

(68.0%; 51/75), whereas those in the non-SCC group primarily had

poorly differentiated tumors (55.6%; 5/9).

Expression and localization of SETD2

and GLI1

The overall positivity of SETD2 and GLI1 proteins

was detected in 90.5% (76/84) and 82.1% (69/84) of tumors,

respectively (Table SV; Fig. S1). Samples positive for SETD2

revealed a consistent nuclear (n) staining pattern, whereas GLI1

protein localization indicated nGLI1 and both n and cytoplasmic

(c)GLI1 staining in 59.4% (41/69) and 40.6% (28/69) of samples,

respectively. According to the histological classification, the

positivity and localization of SETD2 and GLI1 were not

significantly different between the SCC and non-SCC groups

(Table SV).

Expression of SETD2 and GLI1 was compared using IS

values. Analysis of SETD2 and GLI1 IS values according to the

sociodemographic and histopathological characteristics of the

patients revealed that increased nGLI1 levels were significantly

associated with a history of hormonal contraceptive use (Table I). Tumors positive for HPV18 or

other genotypes demonstrated significantly increased levels of

nSETD2 compared with those positive for HPV16 (Table I). Differences in clinical outcomes

were not significantly associated with changes in nGLI1, ncGLI1 or

nSETD2 levels. However, an increasing trend was observed in ncGLI1

levels in overweight/obese patients (Table I).

| Table I.GLI1 and SETD2 cellular localization

in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. |

Table I.

GLI1 and SETD2 cellular localization

in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

|

| Cellular

localization |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | nGLI1 (n=41) | P-value | ncGLI1 (n=29) | P-value | nSETH2 (n=76) | P-value |

|---|

| BMIa, kg/m2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Normal

(<25.0) | 8 (2–9) | 0.793 | 8 (8–12) | 0.098 | 4 (2–8) | 0.838 |

|

Overweight (≥25.0) | 8 (6–8) |

| 12 (8–12) |

| 2 (1–8) |

|

| Tobacco

consumptiona |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 7 (4–9) | 0.772 | 12 (8–12) | 0.533 | 4 (2–8) | 0.286 |

|

Yes | 7 (2–8) |

| 8 (8–12) |

| 4 (1–6) |

|

| Alcohol

consumptiona |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 8 (4–8) | 0.957 | 8 (8–12) | 0.842 | 4 (2–8) | 0.681 |

|

Yes | 6 (4–9) |

| 10 (8–12) |

| 3 (1–8) |

|

| Hormonal

contraceptiona |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 8 (6–8) | 0.029c | 8 (4–12) | 0.365 | 4 (3–5) | 0.957 |

|

Yes | 9 (8–9) |

| 8 (8–12) |

| 4 (1–8) |

|

| FIGO

classificationb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| II | 8 (6–8) | 0.247 | 8 (8–12) | >0.999 | 4 (1–8) | 0.400 |

|

III | 8 (4–8) |

| 10 (8–12) |

| 4 (1–6) |

|

| IV | 5 (1–8) |

| - |

| 4 (3–8) |

|

| Tumor

differentiationb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Well | 6 (4–12) | 0.897 | 6 (4–8) | 0.149 | 5 (2–11) | 0.232 |

|

Moderately | 8 (6–8) |

| 12 (8–12) |

| 3 (1–6) |

|

|

Poorly | 7 (5–8) |

| 8 (6–10) |

| 5 (4–8) |

|

| Lymph node

statusa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 | 8 (6–9) | 0.327 | 8 (8–12) | 0.872 | 4 (1–8) | 0.968 |

| N1 | 6 (4–8) |

| 10 (8–12) |

| 4 (2–8) |

|

| HPV

genotypeb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16 | 8 (4–8) | 0.734 | 10 (6–12) | 0.587 | 3 (1–4) | 0.031c |

| 18 | 5 (4–8) |

| 8 (4–8) |

| 5 (3–8) |

|

|

Other | 8 (6–9) |

| 8 (8–8) |

| 8 (1–9) |

|

| Clinical

responsea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Responder | 6 (4–8) | 0.289 | 12 (8–12) | 0.416 | 4 (1–6) | 0.694 |

|

Non-responder | 8 (8–12) |

| 10 (8–12) |

| 7 (2–8) |

|

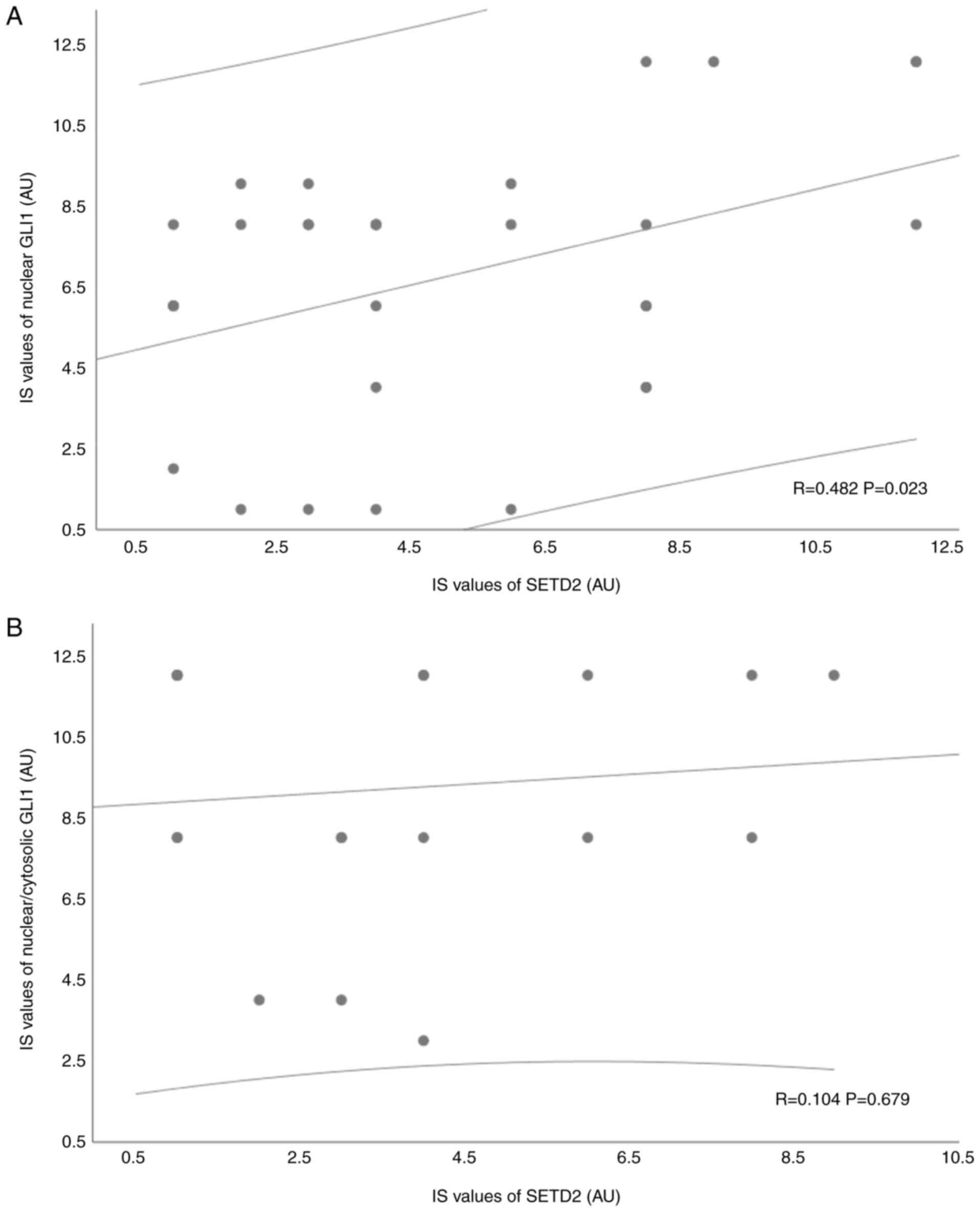

Relationship between SETD2 and GLI1

expression levels

The relationship between SETD2 and GLI1 expression

was evaluated based on tumor positivity and IS values. The

distribution of samples positive for nSETD2 revealed no

statistically significant differences between the nGLI1 (50.0%;

38/76) and ncGLI1 (31.6%; 24/76) groups (Table SVI). However, a positive

correlation was detected between nSETD2 and nGLI1 levels based on

IS values (R=0.428; Fig. 1A). No

significant association was found between nSETD2 and ncGLI1

expression (Fig. 1B).

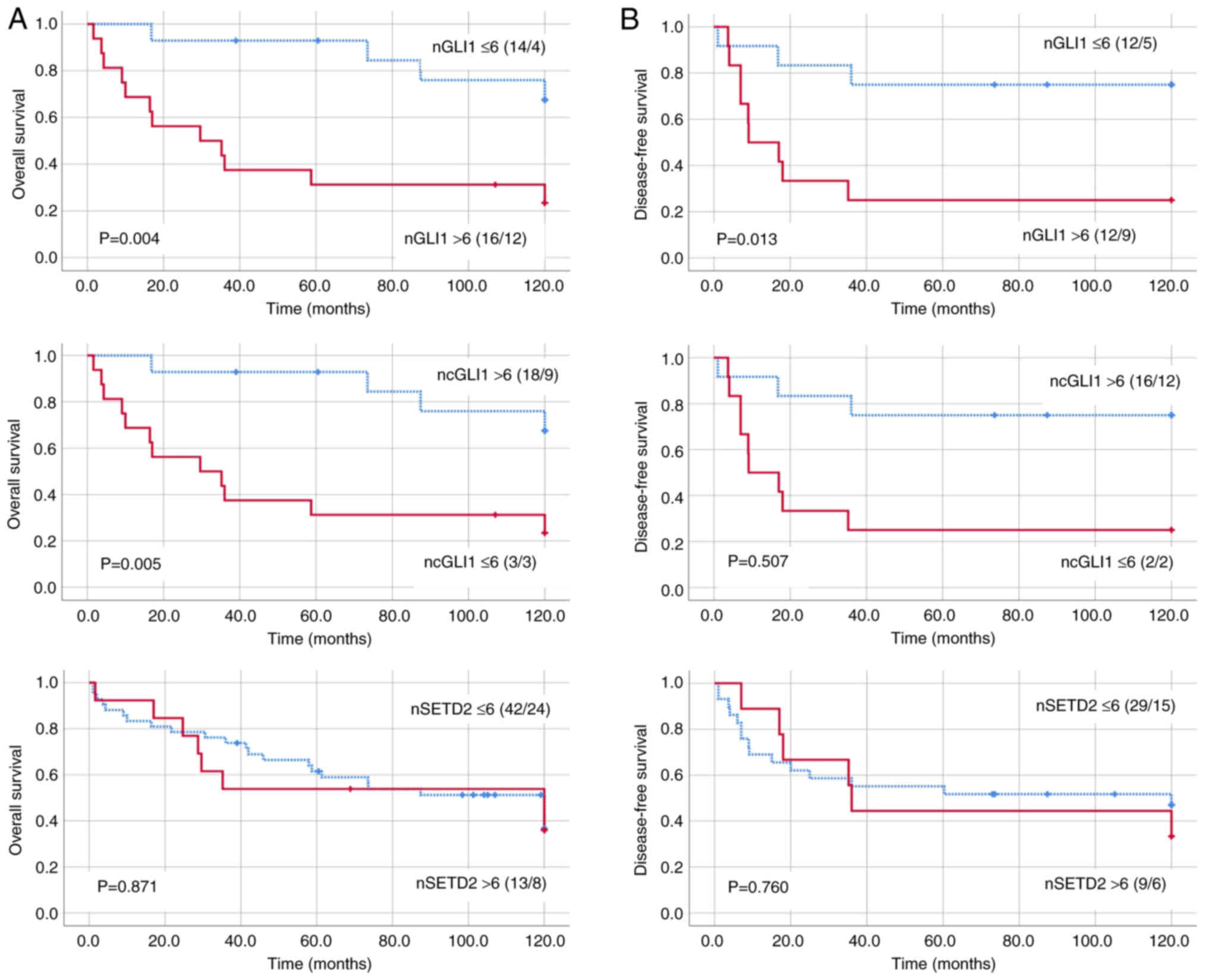

Prognostic utility of SETD2 and GLI1

IS values

The median follow-up period was 53 months (range,

1–120 months). Patients positive for GLI1 or SETD2 demonstrated no

significant differences in OS and DFS rates compared with those

negative for these proteins (Fig.

S2). The predictive values of SETD2 and GLI1 for OS and DFS

were evaluated by categorizing the IS values according to cell

positivity >50% in combination with moderate or strong

immunoreactivity (IS >6; Figs

S3 and S4). Increased GLI1 and

SETD2 expression (IS >6) was observed in 65.2% (45/69) and 26.3%

(20/76) of cases, respectively. Patients with nGLI1 IS >6 had

significantly worse OS and DFS rates compared with those with nGLI1

IS ≤6 (Fig. 2). Conversely,

patients with ncGLI1 IS >6 exhibited improved OS compared with

those with ncGLI1 IS ≤6. No significant differences were observed

in the OS or DFS between the categories for nSETD2.

The univariate analysis revealed an increased

probability of lower OS associated with nGLI IS >6 (HR, 1.50;

95% CI, 1.44–14.13) and ncGLI1 IS ≤6 (HR, 1.86; 95% CI,

1.42–29.55), whereas a lower probability of DFS was significantly

correlated with nGLI IS >6 (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23–17.49).

However, no significant association between nGLI1 and ncGLI1 and

clinicopathological characteristics was detected in the

multivariate analysis (Table

II).

| Table II.Uni- and multivariate Cox regression

analysis of survival rates in patients with locally advanced

cervical cancer. |

Table II.

Uni- and multivariate Cox regression

analysis of survival rates in patients with locally advanced

cervical cancer.

| A, Overall

survival |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| nGLI IS ≤6 | Reference |

|

|

|

| 0.437 |

| nGLI IS >6 | 1.507 | 1.44–14.13 | 0.010 | 0.953 | 0.23–28.70 |

|

| ncGLI IS >6 | Reference |

|

|

|

| 0.988 |

| ncGLI1 IS ≤6 | 1.869 | 1.42–29.55 | 0.016 | 7.15 | 0.00–16.27 |

|

| Hormonal

contraception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 0.431 | 0.57–4.14 | 0.394 |

|

|

|

| BMI,

kg/m2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Normal

(<25.0) | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight/obese (≥25.0) | 0.155 | 0.60–2.25 | 0.645 |

|

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SCC | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-SCC | −0.089 | 0.32–2.56 | 0.866 |

|

|

|

| FIGO

classification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| II | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

III | 0.344 | 0.72–2.74 | 0.311 |

|

|

|

| IV | 0.129 | 0.47–2.70 | 0.771 |

|

|

|

| Lymph node

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

| N1 | −0.145 | 0.42–1.78 | 0.694 |

|

|

|

|

| B, Disease-free

survival |

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| nGLI IS ≤6 | Reference |

|

|

|

| 0.514 |

| nGLI IS >6 | 1.535 | 1.23–17.49 | 0.023 | 1.032 | 0.12–61.92 |

|

| ncGLI1 IS

>6 | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

| ncGLI1 IS ≤6 | 0.750 | 0.21–20.49 | 0.517 |

|

|

|

| Hormonal

contraception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 0.017 | 0.34–3.02 | 0.976 |

|

|

|

| BMI,

kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Normal

(<25.0) | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight/obese (≥25.0) | −0.061 | 0.44–2.01 | 0.874 |

|

|

|

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SCC | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-SCC | 0.496 | 0.62–4.28 | 0.311 |

|

|

|

| FIGO

classification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| II | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

III | 0.152 | 0.52–2.60 | 0.710 |

|

|

|

| IV | 0.405 | 0.57–3.87 | 0.404 |

|

|

|

| Lymph node

status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 | Reference |

|

|

|

|

|

| N1 | 0.395 | 0.67–3.28 | 0.330 |

|

|

|

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the utility of IS in

evaluating the prognostic impact of SETD2 and GLI1 expression in

patients with LACC. Evaluation of IS values according to cellular

localization revealed a significant correlation between increased

levels of nSETD2 and nGLI1 proteins. Furthermore, increased nGLI1

levels were associated with oral estrogen consumption. The present

results demonstrated the prognostic value of changes in the

expression of nGLI1 and ncGLI1 on OS and DFS and their clinical

value in predicting a higher likelihood of mortality.

Previous studies have suggested that chemotherapy

resistance associated with upregulation or mutation of SETD2 in

several malignancies, such as prostate, renal cancer, and gastric

cancer, may be associated with alterations in Wnt/β-catenin and Hh

signaling pathways (21–23). Furthermore, abnormal function of

SETD2 and GLI1 is associated with CRT resistance in advanced CC

(10,13,24).

Therefore, this interaction has been proposed as a potential

candidate for synthetic lethality in patients with a high

probability of recurrence following chemoradiation (5). However, the causal relationship

between alterations in SETD2 and GLI1 during cervical

carcinogenesis remains unknown. In the overall study cohort, a

significant association between increased nSETD2 and nGLI1 was

reported, which indicated that their interactions were associated

with nuclear accumulation. Consistent with previous studies

(11,13), the frequency of increased GLI1

expression (65.2%; 45/69) was notably higher compared with SETD2

upregulation (26.3%; 20/76). Although increased GLI1 expression is

associated with epidermoid tumors (25), no significant differences were

detected in GLI1 positivity according to histological

classification in the present study. These results suggested that

abnormal SETD2 expression was associated with increased nuclear

accumulation and transcriptional activity of GLI1. Further studies

are warranted to determine the mechanisms underlying this

interaction.

The abnormal functionality of SETD2 in CC is

associated with the maintenance of the productive replicative cycle

during HPV infection, particularly in high-risk genotypes (26). According to Gautam et al

(26), upregulation of SETD2 in

cervical epithelial cells is associated with the ability of E7

oncoproteins to prolong protein half-life, which is key to sustain

H3K36me3 levels in the early region of the viral genome. The

present results demonstrated that tumors positive for HPV18 and

other HPV genotypes (HPV6, 11, 31, 43, 42, 45 and 58) significantly

increased nSETD2 levels compared with samples positive for the

HPV16 genotype. This is consistent with previous findings that

cells harboring HPV31 maintain higher levels of SETD2 compared with

those with HPV16 infection (26).

Thus, these findings support the hypothesis that HPV oncoproteins

differentially modify the activity of target proteins during

malignant transformation depending on the cellular environment.

Further studies are required to elucidate whether differences in

SETD2 protein levels associated with HPV genotypes affect

therapeutic strategies that target SETD2 in cancer.

The long-term consumption of oral contraceptives

(OCs) is associated with an increased risk of developing CC,

particularly glandular origin and HPV-positive tumors (HR,

1.77–3.3; CI 95%, 1.4–2.24) (27,28).

Although findings regarding the role of steroid hormones in CC are

controversial, the deleterious effects are primarily associated

with enhanced transcriptional activity of HPV oncogenes (28,29).

Similarly, the risk of invasive CC increases according to the

duration of OC consumption (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.69–2.13),

in addition to being associated with a lower OS time (30,31).

The role of OCs in regulating non-HPV proteins implicated in

cervical carcinogenesis and treatment responses remains poorly

understood. In the present study, significantly higher nGLI1 levels

were observed in patients who used OCs. This finding is consistent

with those of previous studies reporting crosstalk between androgen

stimulation and Hh signaling in prostate cancer, particularly the

association between epithelial-mesenchymal transition and GLI1

upregulation (32,33). Furthermore, estrogenic stimulation

in gynecological cancer is associated with the upregulation and

nuclear translocation of GLI1 via the inhibition of glycogen

synthase kinase-3β (34). Thus, the

present results supported the hypothesis that long-term OC use

contributes to CC progression by stimulating upregulation and

nuclear translocation of GLI1.

Although 90.5% (76/84) of patients with LACC were

SETD2-positive, exhibiting increased expression in 26.3% of cases,

no notable associations were found between SETD2 and OS and DFS. In

malignant neoplasia such as lung and endometrial cancer and CC, the

abnormal function of SETD2 is associated with mutations that modify

gene expression patterns, increasing the risk of CRT resistance and

decreasing survival rates (4,5,19).

According to The Cancer Genome Atlas Program, endocervical ADC

presents the highest rate of SETD2 mutations (7%) (6). In the present study, SETD2 expression

exhibited no difference between histological groups, which may be

associated with the lower proportion of tumors of glandular origin.

Further studies are warranted to clarify the association between

the expression and the mutation rate of SETD2. Rate of SETD2

mutations may increase following treatment with neoadjuvant

chemotherapy (platinum + paclitaxel) in patients with LACC and is

associated with a lack of response (19). This suggests it is necessary to

integrate both expression and mutational analyses when determining

the prognostic and predictive value of SETD2 in LACC.

The Hh signaling cascade serves a key role in the

proliferation, metastasis, recurrence, invasion and CRT resistance

of CC (10). Nevertheless, the

prognostic and predictive value depend on the target protein

analyzed and the criteria employed for evaluation (13,18,35).

Consistent with previous studies, the present study analyzed the

prognostic utility of GLI1 by categorizing the IS; by contrast with

other studies, the present study evaluated the differences

according to cellular localization (18,36).

This revealed that increased nGLI levels may predict a higher

probability of mortality, associated with lower OS and DFS. By

contrast, an increased probability of OS was associated with

increased ncGLI1 levels. These results suggested that the

prognostic and predictive utility of GLI1 depends on the analysis

of proteins according to their cellular localization. Furthermore,

this supports the hypothesis that the role of GLI1 in CRT

resistance is determined by its nuclear translocation, which may

markedly affect the probability of survival (11).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first to investigate the association between the expression and

localization of SETD2 and GLI1 proteins and their role in the

outcome of patients with LACC. A prior study on members of the Hh

pathway in CC established an increase in their expression using

IHC. However, the aforementioned analyses did not include

associations with pathological characteristics or clinical outcomes

(37). Furthermore, epigenetic

dysregulation is associated with several types of cancer including

breast, liver cancer, prostate cancer, and small-cell bladder

cancer (38). Histone

methyltransferases are frequently mutated or deleted in human

tumors (39,40); however, whether alterations in

histone methyltransferases are associated with disease progression

and response to treatment remains unknown. Despite the positive

outcomes, the present study had limitations. The retrospective

study design, with a limited sample size, based on FFPE samples,

limited access to fresh biological material for functional assays

of GLI1 and SETD2 proteins. However, the consistency of sensitivity

analysis results suggested that sample size was not a notable

limitation.

The outcomes in patients with LACC are poor because

they present high rates of resistance to treatment (41). Therefore, the identification of

patients at increased risk of recurrence who may benefit from more

aggressive treatment strategies and the identification of novel

therapeutic targets are key. The interactions of the Hh pathway in

tumor cells are complex and the present study provided insight into

the positive correlation between the expression of SETD2 and the

transcription factor GLI1, which may represent a novel mechanism of

epigenetic regulation involved in the clinical outcome of patients

with LACC. The present data suggested that GLI1 was a valid and

effective therapeutic target in patients with LACC who undergo

chemoradiation.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Alejandro

Lopez-Saavedra (Advanced Microscopy Applications Unit, Mexico City,

Mexico) for technical assistance with capturing the images.

Funding

The present study was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y

Tecnología (grant CF-2019-263979), Proyecto Nacional de

Investigación e Incidencia-7 Virus y Cancer (grant no. 303044),

Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (grant nos. 015/039/IBI,

CEI/998/15, 018/051/IBI and CEI/1294/18) and Consejo de Ciencia y

Tecnología del estado de Tabasco (grant nos. PRODECTI-2023-01/090

and PRODECTI-REICTI-012).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ML conceived the study. ACo and EC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. ACo, EC and ML wrote the

manuscript. ACo and ML acquired funding. ACo conceptualized the

study. GM, LC and ACa designed the methodology. AA and MR

constructed figures. JC and LC supervised the study. JC, AA, EC and

MR analyzed data. ACo, EC and ML edited the manuscript. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics and

Scientific Institutional Review Board (approval no.

INCAN/CEI577/15) of the National Cancer Institute (Mexico City,

México), and written informed consent was obtained from all

participating patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer Statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M,

Colombet M, Mery L, et al: Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today.

Lyon, France, International Agency for Research on Cancer.

2024.https://gco.iarc.who.int/today

|

|

3

|

Hull R, Mbele M, Makhafola T, Hicks C,

Wang S, Reis R, Mehrotra R, Mkhize-Kwitshana Z, Kibiki G, Bates DO

and Dlamini Z: Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries

(Review). Oncol Lett. 20:2058–2074. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sehnal B, Kmoníčková E, Sláma J, Tomancová

V and Zikán M: Current FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix

uteri and treatment of particular stages. Klin Onkol. 32:224–231.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lizano M, Carrillo-García A, De La

Cruz-Hernández E, Castro-Muñoz LJ and Contreras-Paredes A:

Promising predictive molecular biomarkers for cervical cancer

(Review). Int J Mol Med. 53:502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lu M, Zhao B, Liu M, Wu L, Li Y, Zhai Y

and Shen X: Pan-cancer analysis of SETD2 mutation and its

association with the efficacy of immunotherapy. NPJ Precis Oncol.

5:512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zeng Z, Zhang J, Li J, Li Y, Huang Z, Han

L, Xie C and Gong Y: SETD2 regulates gene transcription patterns

and is associated with radiosensitivity in lung adenocarcinoma.

Front Genet. 13:9356012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Viaene AN, Santi M, Rosenbaum J, Li MM,

Surrey LF and Nasrallah MP: SETD2 mutations in primary central

nervous system tumors. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 6:1232018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jing J, Wu Z, Wang J, Luo G, Lin H, Fan Y

and Zhou C: Hedgehog signaling in tissue homeostasis, cancers and

targeted therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3152023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu C and Wang R: The roles of hedgehog

signaling pathway in radioresistance of cervical cancer. Dose

Response. 17:15593258198852932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu Z, Huang C, Li R, Li H, Lu H and Lin Z:

PRKCI mediates radiosensitivity via the Hedgehog/GLI1 pathway in

cervical cancer. Front Oncol. 12:8871392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Huang C, Lu H, Li J, Xie X, Fan L, Wang D,

Tan W, Wang Y, Lin Z and Yao T: SOX2 regulates radioresistance in

cervical cancer via the hedgehog signaling pathway. Gynecol Oncol.

151:533–541. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chaudary N, Pintilie M, Hedley D, Fyles

AW, Milosevic M, Clarke B, Hill RP and Mackay H: Hedgehog pathway

signaling in cervical carcinoma and outcome after chemoradiation.

Cancer. 118:3105–3115. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chai JY, Sugumar V, Alshanon AF, Wong WF,

Fung SY and Looi CY: Defining the Role of GLI/Hedgehog signaling in

Chemoresistance: Implications in therapeutic approaches. Cancers

(Basel). 13:47462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gennigens C, De Cuypere M, Hermesse J,

Kridelka F and Jerusalem G: Optimal treatment in locally advanced

cervical cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 21:657–671. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vázquez-Ulloa E, Ramos-Cruz AC, Prada D,

Avilés-Salas A, Chávez-Blanco AD, Herrera LA, Lizano M and

Contreras-Paredes A: Loss of nuclear NOTCH1, but not its negative

regulator NUMB, is an independent predictor of cervical malignancy.

Oncotarget. 9:18916–18928. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bohr Mordhorst L, Ahlin C and Sorbe B:

Prognostic impact of the expression of Hedgehog proteins in

cervical carcinoma FIGO stages I–IV treated with radiotherapy or

chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 135:305–311. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lizano M, De la Cruz-Hernández E,

Carrillo-García A, García-Carrancá A, Ponce de Leon-Rosales S,

Dueñas-González A, Hernández-Hernández DM and Mohar A: Distribution

of HPV16 and 18 intratypic variants in normal cytology,

intraepithelial lesions, and cervical cancer in a Mexican

population. Gynecol Oncol. 102:230–235. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sotlar K, Diemer D, Dethleffs A, Hack Y,

Stubner A, Vollmer N, Menton S, Menton M, Dietz K, Wallwiener D, et

al: Detection and typing of human papillomavirus by e6 nested

multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 42:3176–3184. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kumar A, Kumari N, Gupta V and Prasad R:

Renal cell carcinoma: Molecular aspects. Indian J Clin Biochem.

33:246–254. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jiang C, He C, Wu Z, Li F and Xiao J:

Histone methyltransferase SETD2 regulates osteosarcoma cell growth

and chemosensitivity by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 502:382–388. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen R, Zhao WQ, Fang C, Yang X and Ji M:

Histone methyltransferase SETD2: A potential tumor suppressor in

solid cancers. J Cancer. 11:3349–3356. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li W, Huang Y, Xiao M, Zhao J, Du S, Wang

Z, Hu S, Yang L and Cai J: PBRM1 presents a potential ctDNA marker

to monitor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cervical cancer.

iScience. 27:1091602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vishnoi K, Mahata S, Tyagi A, Pandey A,

Verma G, Jadli M, Singh T, Singh SM and Bharti AC: Cross-talk

between Human Papillomavirus Oncoproteins and hedgehog signaling

synergistically promotes stemness in cervical cancer cells. Sci

Rep. 6:343772016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gautam D, Johnson BA, Mac M and Moody CA:

SETD2-dependent H3K36me3 plays a critical role in epigenetic

regulation of the HPV31 life cycle. PLoS Pathog. 14:e10073672018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Asthana S, Busa V and Labani S: Oral

contraceptives use and risk of cervical cancer-A systematic review

& meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 247:163–175.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gadducci A, Cosio S and Fruzzetti F:

Estro-progestin contraceptives and risk of cervical cancer: A

debated issue. Anticancer Res. 40:5995–6002. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wei X, Hong L, Liang H, Ren K, Man W, Zhao

Y and Guo P: Estrogen and viral infection. Front Immunol.

16:15567282025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gashu C, Tasfa B, Alemu C and Kassa Y:

Assessing survival time of outpatients with cervical cancer: At the

university of Gondar referral hospital using the Bayesian approach.

BMC Womens Health. 23:592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

International Collaboration of

Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer, . Appleby P, Beral V,

Berrington de González A, Colin D, Franceschi S, Goodhill A, Green

J, Peto J, Plummer M and Sweetland S: Cervical cancer and hormonal

contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data for

16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical

cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 370:1609–1621.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yamamichi F, Shigemura K, Behnsawy HM,

Meligy FY, Huang WC, Li X, Yamanaka K, Hanioka K, Miyake H, Tanaka

K, et al: Sonic hedgehog and androgen signaling in tumor and

stromal compartments drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition in

prostate cancer. Scand J Urol. 48:523–532. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lubik AA, Nouri M, Truong S, Ghaffari M,

Adomat HH, Corey E, Cox ME, Li N, Guns ES, Yenki P, et al:

Paracrine sonic hedgehog signaling contributes significantly to

acquired steroidogenesis in the prostate tumor microenvironment.

Int J Cancer. 140:358–369. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kaushal JB, Sankhwar P, Kumari S, Popli P,

Shukla V, Hussain MK, Hajela K and Dwivedi A: The regulation of

Hh/Gli1 signaling cascade involves Gsk3β-mediated mechanism in

estrogen-derived endometrial hyperplasia. Sci Rep. 7:65572017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Cui Y, Cui CA, Yang ZT, Ni WD, Jin Y and

Xuan YH: Gli1 expression in cancer stem-like cells predicts poor

prognosis in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Mol

Pathol. 102:347–353. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sinicrope FA, Ruan SB, Cleary KR, Stephens

LC, Lee JJ and Levin B: Bcl-2 and p53 oncoprotein expression during

colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 55:237–241. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Xuan YH, Jung HS, Choi YL, Shin YK, Kim

HJ, Kim KH, Kim WJ, Lee YJ and Kim SH: Enhanced expression of

hedgehog signaling molecules in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine

cervix and its precursor lesions. Mod Pathol. 19:1139–1147. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yu X, Zhao H, Wang R, Chen Y, Ouyang X, Li

W, Sun Y and Peng A: Cancer epigenetics: From laboratory studies

and clinical trials to precision medicine. Cell Death Discov.

10:282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tinsley E, Bredin P, Toomey S, Hennessy BT

and Furney SJ: KMT2C and KMT2D aberrations in breast cancer. Trends

Cancer. 10:519–530. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Na F, Pan X, Chen J, Chen X, Wang M, Chi

P, You L, Zhang L, Zhong A, Zhao L, et al: KMT2C deficiency

promotes small cell lung cancer metastasis through DNMT3A-mediated

epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Cancer. 3:753–767. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Niu Y, Du C, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Guo Q and

Zhou H: A comparative analysis of survival outcomes and adverse

effects between preoperative brachytherapy with radical surgery and

concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced

cervical cancer. Front Oncol. 15:15117482025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|