Introduction

Thyroid cancer ranks among the malignancies with the

most rapidly increasing incidence. In the United States, its

age-standardized incidence rate nearly tripled from 1975–1979 to

2015–2019. This trend has been particularly prominent among female

patients in large urban areas, with the incidence among female

patients rising from 7.8 to 29.5/100,000 during the same period,

making it one of the most common cancer types in female patients

(1,2). Although early-stage thyroid cancer is

generally associated with favorable outcomes following timely

diagnosis and treatment, the 5-year relative survival rate is

~98.5%, advanced disease accompanied by local invasion and distant

metastasis remains a key challenge, often leading to poor prognosis

(3). Thus, elucidating the

molecular mechanisms underlying thyroid cancer progression and

identifying relevant biomarkers are key for the enhancement of

diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic strategies.

Folate receptor γ (FOLR3) is a key member of the

folate receptor family. FOLR3 belongs to a soluble receptor subtype

that serves a key role in the uptake and utilization of

extracellular folic acid (4).

Folate serves a dual role in cancer. On the one hand, folate may

help prevent the development of certain cancer types. Previous

studies have suggested that high folate intake is associated with a

reduced risk of breast, colorectal and ovarian cancer types, making

it a candidate for targeted cancer therapy (5–8). By

contrast, folate may also promote cancer progression, for example,

certain studies indicate that it might accelerate the development

of prostate cancer (9,10). Dietary folate promotes

hepatocellular carcinoma progression by hijacking methionine

metabolism through VCIP135-mediated stabilization of methionine

adenosyltransferase IIα, thereby coupling one-carbon and methionine

metabolic flux to fuel tumor growth (11). The abnormal expression of FOLR3 may

contribute to tumorigenesis and progression by interfering with

folate metabolism, affecting DNA synthesis, methylation and cell

proliferation. Furthermore, FOLR3 can exert antimicrobial and

antitumor effects by sequestering natural folate, thereby depriving

bacteria and tumor cells of this vital nutrient (12,13).

Although evidence suggests that FOLR3 is involved in cancer

pathogenesis, its specific function in thyroid cancer remains

poorly understood (14–17). Therefore, investigating the

expression level of FOLR3 in thyroid cancer and its association

with clinicopathological features may offer novel biomarkers for

early diagnosis and prognosis evaluation of thyroid cancer.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic analysis

Gene expression data for thyroid cancer were

obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA;

portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) database and the Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO; ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) dataset GSE250521 (18). From TCGA, the Thyroid Carcinoma

project dataset was downloaded via the Genomic Data Commons Data

Portal, which includes RNA-Seq data from tumor and adjacent normal

tissue. The combined dataset included clinical information for 572

individuals, comprising of 513 thyroid cancer cases and 59 normal

controls. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using

the ‘limma’ package in the R software (version 3.64.1; R

Development Core Team) (19), with

a significance threshold set at adjusted P<0.05 and

|log2FC|>2.5. Genes with log2FC >2.5

were considered upregulated, those with log2FC <-2.5

were classified as downregulated and genes with values between −2.5

and 2.5 were regarded as unchanged. Functional enrichment analyses,

including Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses were performed using the

‘clusterProfiler’ package (version 4.16.0) in R (20). Univariate Cox regression analysis

and multivariate Cox regression analysis were performed using the

‘survival’ (version 3.8–3) and ‘survminer’ packages (version 0.4.9)

in R (21). Furthermore, FOLR3

expression in thyroid cancer was evaluated using the GEPIA2.0

(gepia.cancer-pku.cn) and University of Alabama at Birmingham

Cancer data analysis Portal (ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html)

databases. For immune/stromal infiltration analysis, Cell-type

Identification by Estimating Relative Subsets of RNA Transcripts

(CIBERSORT) estimated immune cell proportions via deconvolution,

while ESTIMATE calculated immune and stromal scores from signature

gene sets (22,23). Together, they provide a

comprehensive tumor microenvironment (TME) composition profile.

The single-cell gene expression matrix was

preprocessed using the ‘Seurat’ R package (version 4.4.0) to ensure

data quality and prepare for downstream analyses (24). Cell filtering was performed by

retaining cells that met the following criteria: Detection of ≥500

genes, presence in ≥3 cells with non-zero unique molecular

identifier (UMI) counts and a mitochondrial UMI ratio <25%.

Genes detected in <3 cells were excluded. Highly variable genes

were selected for dimensionality reduction via principal component

analysis and the top 30 principal components were used for Uniform

Manifold Approximation and Projection to visualize high-dimensional

gene expression patterns in two dimensions. The Harmony algorithm

was applied to correct for batch effects and minimize technical

variability (25). Cell clustering

was performed using the ‘FindClusters’ function with a resolution

parameter of 0.7 to identify distinct cell populations.

Differential expression analysis across cell subpopulations was

conducted with the ‘FindAllMarkers’ function using the Wilcoxon

rank-sum test and P-values were adjusted for multiple analysis with

the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Cell-cell communication

analysis was carried out with the ‘CellChat’ package (version

1.6.1) to predict ligand-receptor interactions (26). Folate metabolism-related gene sets

were obtained from the Molecular Signatures database and pathway

activity scores were calculated using the ‘AddModuleScore’ function

(27). Cells were stratified into

high- and low-score groups based on the median pathway score, with

a cutoff of 0.108. Myeloid cell subpopulations were annotated using

the same workflow and analytical methods.

Clinical data

The present study included a total of 293 patients

with thyroid cancer who were treated at Chifeng Hospital of Inner

Mongolia (Chifeng, China) between January 2021 and June 2024. The

cohort comprised 51 male and 242 women, with ages ranging from 19

to 78 years. According to the histopathological diagnosis, there

were 287 cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), 3 cases of

follicular thyroid carcinoma and 3 cases of anaplastic thyroid

carcinoma. The collected clinical and pathological parameters

included sex, age, capsule invasion, perineural invasion, striated

muscle cell infiltration, pathological tumor (pT) stage, tumor

location, tumor focality, histological type, vascular infiltration

and pathological lymph node (pN) stage, assessed according to the

American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system (8th edition)

(28).

Construction of high-throughput

thyroid tumor tissue microarray

Tissue samples were sourced from the surgical

resection specimens of the 293 thyroid cancer patients. A manual

tissue microarrayer was used to mark the tumor regions on large

tissue sections. A 1 mm diameter core was extracted from each donor

block and transferred into a recipient paraffin block to construct

a high-throughput thyroid tumor tissue microarray. For each case,

one core was taken from the tumor invasion front and one from

adjacent normal thyroid tissue.

Immunohistochemical staining

(IHC)

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections

(thickness, 4 µm) were used. Tissue samples were fixed in 10%

neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for 24–48 h. Antigen

retrieval was performed using EnVision two-step method (95–100°C,

15–20 min). Sections were dewaxed, rehydrated through a descending

alcohol series (100, 95, 70% ethanol) to distilled water, and

endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen

peroxide for 10 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding was

blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature.

Normal serum was incubated with rabbit anti-human FOLR3 antibody

(1:100; cat. no. DF9519; Affinity Biosciences) overnight at 4°C.

After washing, EnVision HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary

antibody (1:100; Wuhan Proteintech, SA00001-2) was added for 30 min

at room temperature, and DAB staining was used for color

development. Hematoxylin re-dyeing for 2 min at room temperature.

Phosphate buffer, isotype rabbit IgG (1:100, Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology, Ltd.) instead of primary antibody were used

as a negative control. Images were acquired using a light

microscope (Olympus Corporation) at ×200 magnification. The

percentage of cells positive for FOLR3 in thyroid cancer tissue vs.

paired normal tissue was identified by QuPath software (version

0.4.4, QuPath) (29). The criteria

for cytosol staining intensity was as follows: Negative, <0.20;

1, 0.2–0.39; 2, 0.40–0.6 and 3+, >0.6 (30). IHC results were evaluated using

H-score method (31).

Cell culture

Human thyroid carcinoma TPC-1 cells (Abcells; cat.

no. AC153) were cultured in complete medium (Seven Biotech) at 37°C

in a 5% CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cells were passaged every 2–3 days to maintain exponential

growth.

Transfection

TPC-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and grown

to ~70% confluence. The human FOLR3 overexpression plasmid

(pcDNA3.1-hFOLR3-3XFLAG) and corresponding empty vector control

(pcDNA3.1) were synthesized by Beijing Likeli Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). Cells were transfected with 2.5 µg FOLR3 overexpression or

the empty control plasmid using 4 µl Lipo8000™ transfection reagent

(Beyotime Biotechnology, C0533), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The transfection complexes were added at 37°C. The

culture medium was not replaced post-transfection. Transfected

cells were harvested for subsequent experimentation 48 h

post-transfection. Transfected cells were divided into two groups:

Flag-FOLR3 group (FOLR3 overexpression) and the Flag-negative

control (NC) group.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from Flag-FOLR3 and NC

groups using the RNAprep pure cell kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.)

and reverse transcribed into cDNA with the PrimeScript™ RT reagent

kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). RT was performed at 37°C for 15 min,

followed by enzyme inactivation at 85°C for 5 sec. RT-qPCR was

using the Beyofast SYBR™ Green qPCR mix (Beyotime Biotechnology) on

a Fluorescent Quantitative PCR Instrument (Bio-Rad). Thermocycling

conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and

annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. The relative expression

level of FOLR3 and folate metabolism-related genes was normalized

to that of GAPDH, which served as the reference gene. All primers

were designed and synthesized by Beyotime Biotechnology and

quantification was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(data not shown; Table I) (32). Each experiment was performed three

times in duplicate.

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer sequences

(5′-3′ |

|---|

| FOLR3 | F:

CGCAAAGAGCGCATTCTGAAC |

|

| R:

CTGGGCTGAGTCAAACCACA |

| GAPDH | F:

ACGGATTTGGTCGTATGGG |

|

| R:

CGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTGAT |

| TYMS | F:

TGATGGTGTCAATCACTCTTTGC |

|

| R:

TGGGGCAGAATACAGAGATATGG |

| MTHFR | F:

GAGCGGCATGAGAGACTCC |

|

| R:

CCGGTCAAACCTTGAGATGAG |

| SLC19A1 | F:

CTCAGCTTCGTGTCGGTGT |

|

| R:

AGCGAGATGTAGTTGAGCGTG |

| PCFT | F:

GGCCCAGGGTTATGCCAAC |

|

| R:

GGACAATGGATCGGTGGTGAC |

| Cyclin D1 | F:

CAATGACCCCGCACGATTTC |

|

| R:

CATGGAGGGCGGATTGGAA |

| Bcl-2 | F:

GGTGGGGTCATGTGTGTGG |

|

| R:

CGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCATCC |

| c-FOS | F:

GGGGCAAGGTGGAACAGTTAT |

|

| R:

CCGCTTGGAGTGTATCAGTCA |

| c-Jun | F:

TCCAAGTGCCGAAAAAGGAAG |

|

| R:

CGAGTTCTGAGCTTTCAAGGT |

| VEGF | F:

AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAGT |

|

| R:

AGGGTCTCGATTGGATGGCA |

| MCL1 | F:

GTGCCTTTGTGGCTAAACACT |

|

| R:

AGTCCCGTTTTGTCCTTACGA |

Protein isolation and western

blotting

TPC-1 cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Beyotime

Biotechnology) supplemented with PMSF (Beyotime Biotechnology) and

homogenized mechanically until complete lysis was achieved. The

lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C to collect

the supernatant. Protein concentration was determined using the

Enhanced BCA Protein Assay Kit. Proteins (10 µg per lane) were

separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The

membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST at room

temperature for 1 h, the corresponding FOLR3 (1:2,000; Affinity

Biosciences; cat. no. DF9519) and GAPDH antibody (1:2,000; Wuhan

Boster Biological Technology, Ltd, BA1050) was added overnight at

4°C. The membrane was washed and then the HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5,000; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd, BM3874) was added for 1 h at room temperature. The

indicator proteins were assessed using a hypersensitive ECL

chemiluminescence kit (Seven Biotech) and the relative expression

level of FOLR3 was normalized to GAPDH. Each experiment was

performed three times in duplicate.

Scratch assay

After transfection, cells from the Flag-FOLR3 and NC

groups were seeded at 1×106 cells per well into 6-well

plate until they reached 100% confluence. A scratch was made in

each well using a sterile 200 µl pipette tip. Cells were washed and

cultured in RPMI-1640 (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.). Wound healing was observed and captured at 0, 24 and 48

h using an inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation). The migration

distance was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.53f;

National Institutes of Health). Each experiment was performed three

times in duplicate.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Transfected cells were seeded into 96-well plates.

After culturing for 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, enhanced CCK-8

(Beyotime Biotechnology) was added to each well. Following

incubation for 1.5 h, the optical density value at 450 nm was

measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), Each experiment was performed three times in duplicate.

Clone formation assay

Transfected cells were seeded at 1,000 cells/well

into 6-well plates and cultured for 14 days in a CO2

incubator at 37°C. Cells were fixed at room temperature with 4%

paraformaldehyde (Beyotime Biotechnology) for 20 min and stained

with 0.1% crystal violet solution (Beyotime Biotechnology) at room

temperature for another 20 min. Each experiment was performed three

times in duplicate.

Transwell invasion assay

The upper chamber of Transwell plates were

pre-coated with Matrigel™ Basement Membrane Matrix (Beyotime

Biotechnology) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. A cell suspension

containing 5×104 cells in 200 µl serum-free RPMI-1640

medium (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). was

added to the upper chamber and 600 µl TPC-1 complete medium

(Abcells) containing 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber.

Following incubation for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator, cells that had invaded through the membrane were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, stained

with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min and counted

under a microscope. Each experiment was performed three times in

duplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism (version 8.0.2; Dotmatics), ImageJ (version 1.53f; National

Institutes of Health) and SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM Corp.),

and R software (version 4.2.3). Data from the IHC analysis are

presented as mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant. In bioinformatic analyses, significance thresholds

were set at P<0.05 and a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05.

For functional experiments, group comparisons were conducted as

follows: the CCK-8 cell proliferation, scratch wound healing,

colony formation and Transwell invasion assays were analyzed using

unpaired Student's t-tests. Comparisons of FOLR3 expression between

paired tumor and adjacent normal tissue in IHC were analyzed using

paired Student's t-test. The associations between FOLR3 expression

and clinicopathological features (including age, sex, tumor

location, pT and pN stage, perineural and vascular invasion) were

evaluated using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test, as

appropriate. Independent prognostic factors were identified using

multivariate Cox regression analysis. All bioinformatic statistical

computations, data processing and visualizations were performed

using R software.

Results

Bioinformatics analysis of FOLR3

expression in thyroid cancer and normal adjacent tissue

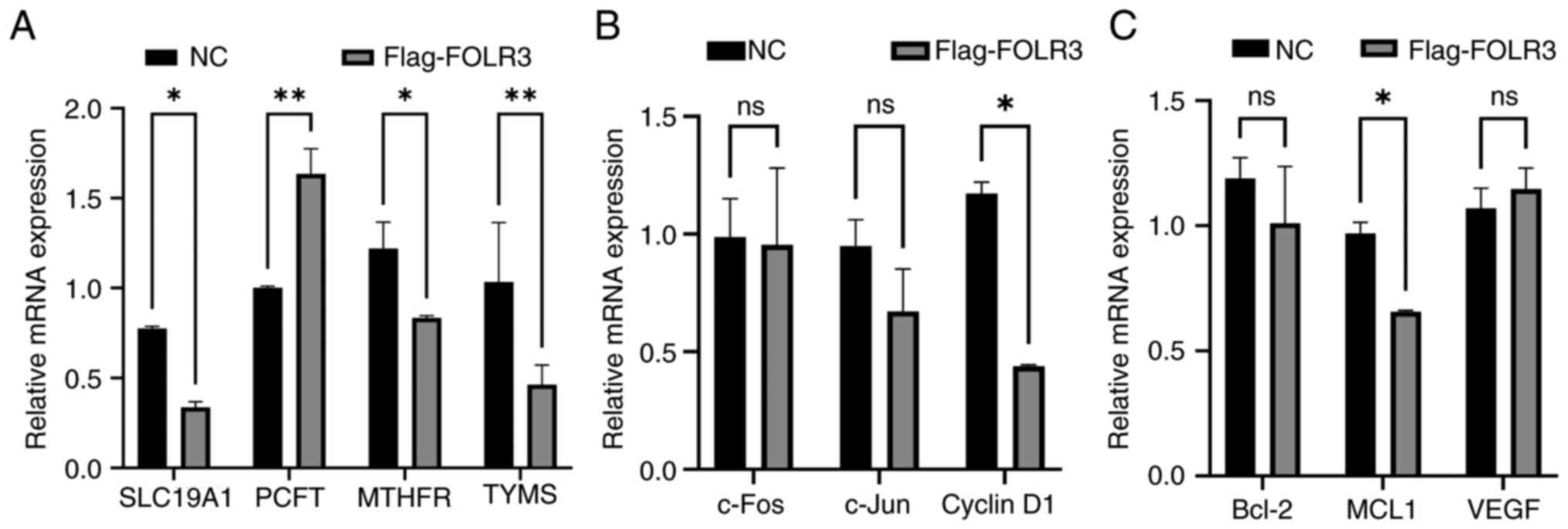

Expression profiling analysis of thyroid cancer data

from TCGA identified 520 differentially expressed genes (DEGs),

including 235 up- and 285 downregulated genes. The distribution of

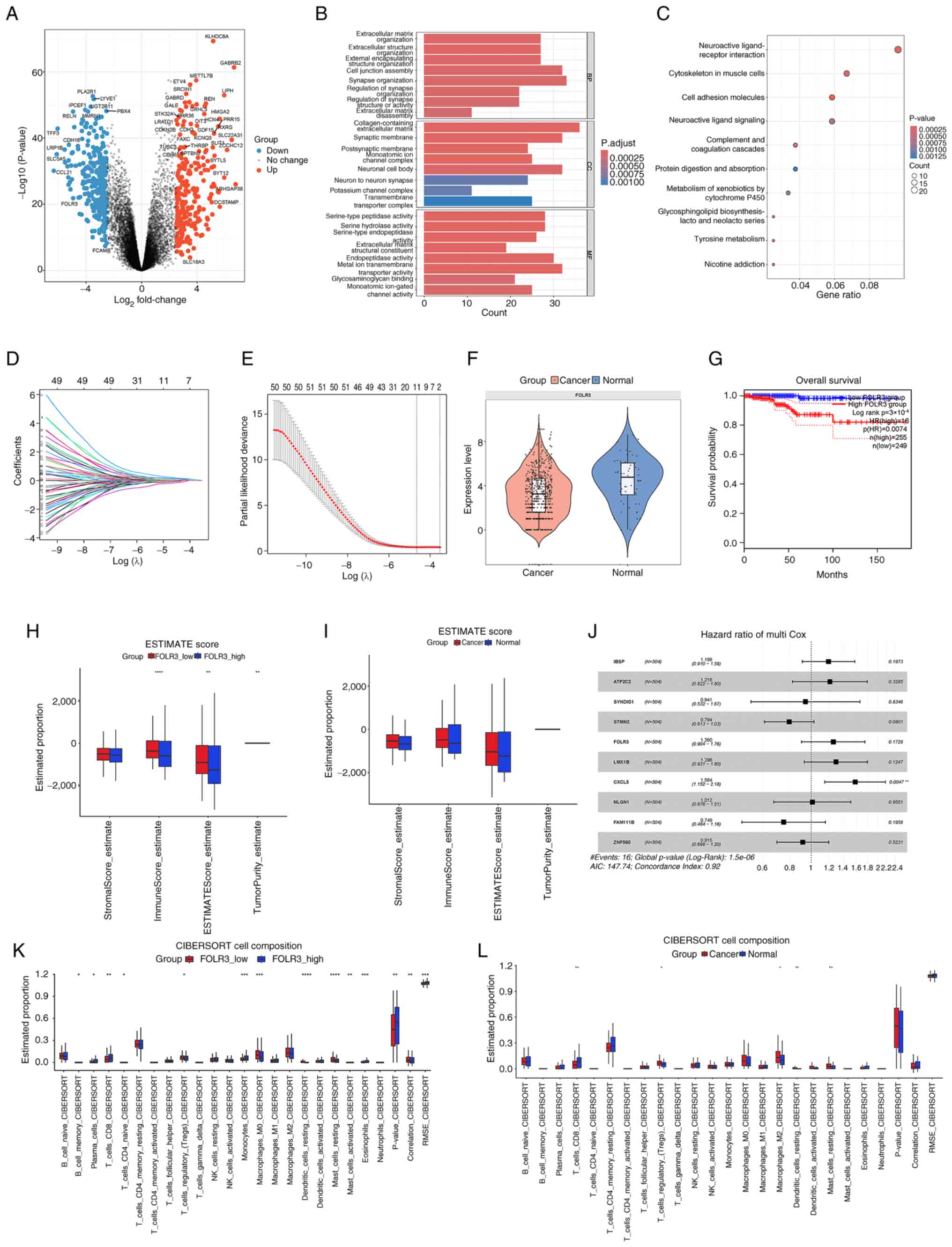

these DEGs is visually represented in the volcano plot (Fig. 1A). GO enrichment analysis identified

24 enriched terms in the three major categories: Biological

process, cellular component and molecular function, while KEGG

pathway analysis revealed 10 significantly enriched pathways

(P<0.01; Fig. 1B and C). GO

enrichment analysis was primarily associated with ‘neural

synapse-related functions’, ‘extracellular matrix remodeling’ and

‘ion channel activity’. KEGG pathway analysis highlighted processes

such as ‘cell adhesion molecules’, ‘tyrosine metabolism’, ‘protein

digestion and absorption’ and ‘complement and coagulation

cascades’.

| Figure 1.Analysis of FOLR3 expression and its

impact in thyroid cancer. (A) Volcano plot of DEGs (red,

upregulated; blue, downregulated). (B) GO enrichment analysis

demonstrating three major functional categories. (C) KEGG pathway

enrichment of DEGs. (D) LASSO regression model for feature

selection. (E) A 10-fold cross-validation curve for the LASSO

model. (F) FOLR3 expression levels in thyroid cancer vs. normal

tissue. (G) Survival analysis based on FOLR3 expression. (H)

ESTIMATE scores comparing high vs. low FOLR3 expression groups. (I)

ESTIMATE scores in thyroid cancer vs. normal tissues. (J)

Univariate Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors. (K)

CIBERSORT analysis of immune infiltration in high vs. low FOLR3

expression groups. (L) CIBERSORT analysis of immune infiltration in

thyroid cancer vs. normal tissues. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. FOLR3, folate receptor γ; GO,

Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes;

LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; CIBERSORT,

Cell-type Identification by Estimating Relative Subsets of RNA

Transcripts; DEGs, differentially expressed genes. |

Furthermore, a least absolute shrinkage and

selection operator (LASSO) regression model, developed using

machine learning techniques was employed to identify genes

associated with the progression and prognosis of thyroid cancer

(Fig. 1D). The resulting LASSO

regression model and the results of cross-validation results

selected 10 relevant genes (integrin-binding sialoprotein, ATPase

secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 2, synapse

differentiation induced gene 1, stathmin-2, FOLR3, LIM homeobox

transcription factor 1-β, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 5,

neuroligin-1, family with sequence similarity 111, member B and

zinc finger protein 560; Fig. 1E).

FOLR3 was selected as a research focus as it is one of the

significantly downregulated genes in thyroid cancer, and the LASSO

regression model identified it as one of the ten key genes

associated with disease progression and prognosis.

The present study results demonstrated that FOLR3

expression was significantly downregulated in thyroid cancer

tissues compared with normal tissues (P<0.001; Fig. 1F). Survival analysis indicated that

high expression level of FOLR3 was associated with significantly

worse overall survival in patients with thyroid cancer (P=0.0074;

Fig. 1G). Multivariate Cox

regression analysis identified CXCL5 as a significant independent

prognostic biomarker for thyroid cancer (P=0.0047; Fig. 1J). Comparative assessment of TME

profiles revealed distinct immune and stromal features associated

with FOLR3 expression levels and tissue status in thyroid cancer.

ESTIMATE algorithm revealed low FOLR3 expression was associated

with lower tumor purity (P<0.001) and higher immune scores (both

P<0.001) and ESTIMATE scores (P=0.0011; Fig. 1H). Similarly, thyroid cancer tissues

exhibited markedly lower immune and stromal infiltration overall

compared with normal tissues (Fig.

1I). CIBERSORT-based immune deconvolution further illustrated

divergent microenvironmental landscapes. High FOLR3 expression was

associated with increased infiltration of antitumor immune subsets,

including plasma cells (P=0.0415), CD8+ T cells

(P=0.0027). By contrast, low FOLR3 expression favored an

immunosuppressive milieu, characterized by elevated naïve

CD4+ memory T cells (P=0.043), M0 macrophages (P=0.0005)

and activated mast cells (P=0.0078) (Fig. 1K). Thyroid cancer tissues displayed

enriched infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, such as resting

Tregs (P=0.023), M2 macrophages (P=0.431), resting dendritic cells

(P=0.0042) and resting mast cells (P=0.0011), compared

with normal tissues, indicating an overall immunosuppressive TME

(P<0.001) (Fig. 1L). These

results collectively indicate that FOLR3 expression is closely

associated with immune-active microenvironment phenotypes, while

its downregulation may contribute to an immunosuppressive TME in

thyroid cancer.

Remodeling of the TME in PTC:

Metabolic reprogramming, immune activation and altered cellular

communication driven by folate-high M1 macrophages

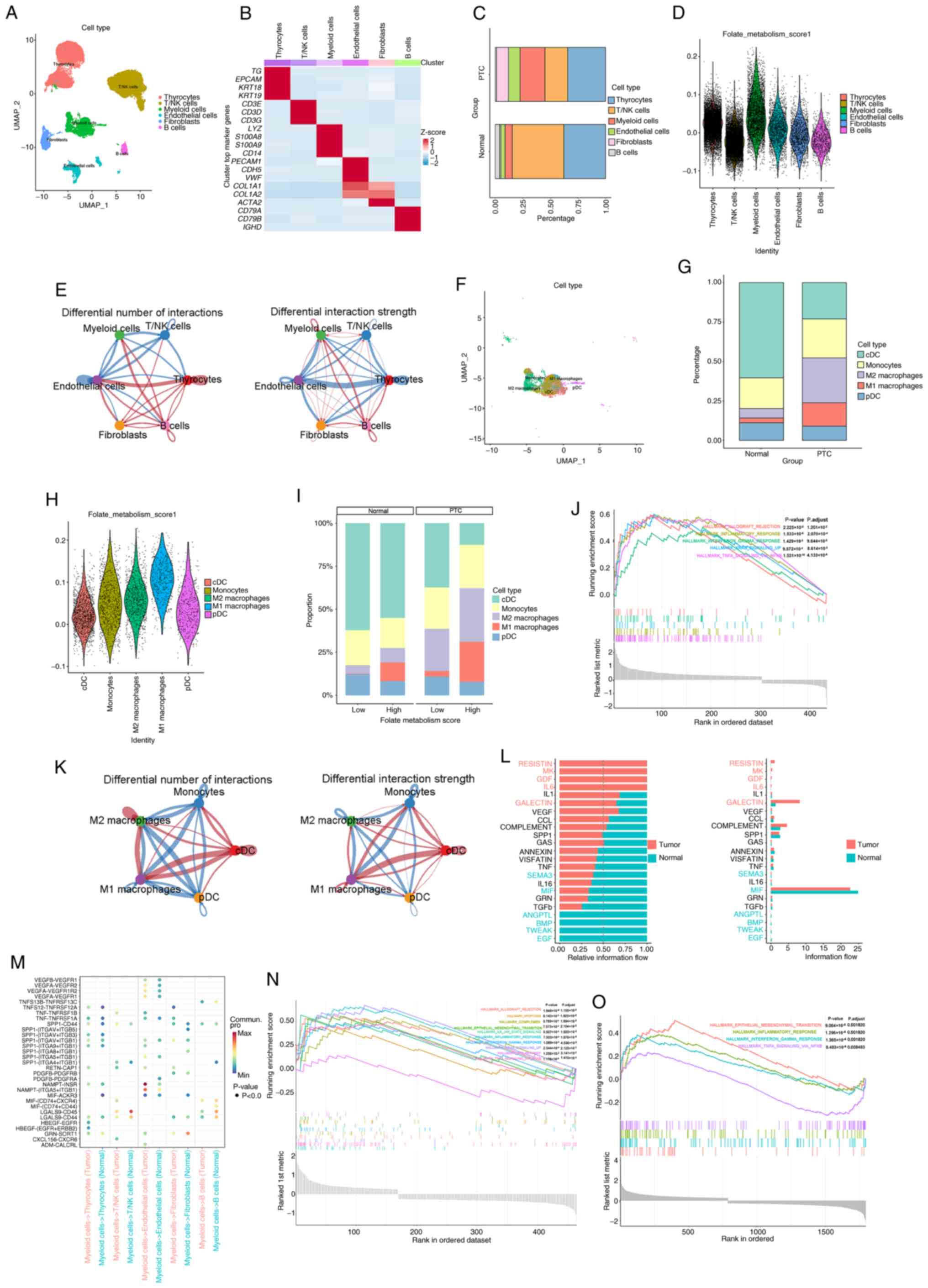

The present study comprehensively characterized the

TME of PTC through integrated analysis of single-cell

transcriptomic data and functional enrichment. The PTC dataset

GSE250521 was downloaded from the GEO database. After quality

control and normalization, the dataset contained 33,505 cells and

31,454 genes. Manual annotation of the main cell subsets revealed

six distinct populations: Thyrocytes [thyroglobulin (TG),

epithelial cell adhesion molecule, keratin (KRT) 18 and KRT19],

fibroblasts (collagen type I α 1 chain, collagen type I α 2 chain,

collagen type III α 1 chain and actin, α 2, smooth muscle),

endothelial cells (platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1,

CD34, cadherin 5 and von Willebrand factor), T/natural killer (NK)

cells (CD3D, CD3E, CD3G and CD247), B cells (CD79A, CD79B,

immunoglobulin heavy constant µ and immunoglobulin heavy constant

Δ) and myeloid cells (lysozyme, S100 calcium binding protein A8,

S100 calcium binding protein A9 and CD14) (Fig. 2A and B).

Key findings revealed extensive remodeling of the

TME in PTC, beginning with a marked shift in cellular composition:

The present study observed a marked decrease in thyrocytes and a

concurrent increase in myeloid cells, indicative of enhanced

stromal and immune infiltration accompanied by loss of functional

thyroid epithelium (Fig. 2C).

Further analysis identified elevated folate metabolism activity as

a hallmark of PTC, particularly within myeloid cells. Notably, M1

macrophages not only demonstrated the highest folate metabolic

score among all subsets but also constituted the majority of cells

within the high folate metabolism group (Fig. 2D, H and I). Sub-clustering of

myeloid cells confirmed the expansion of M1 macrophages in PTC

(Fig. 2F and G) and these cells

exhibited pronounced enrichment of immune-inflammatory pathways,

including TNF-α, IFN-γ, KRAS and NF-κB signaling, allograft

rejection, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and complement

activation (Fig. 2J, N and O). Cell

communication analysis revealed that M1 macrophages undergo the

most notable alterations in both the number and strength of

interactions, notably with T/NK cells and engage key

ligand-receptor axes such as secreted phosphoprotein 1-CD44,

TNF-TNF receptor superfamily, macrophage migration inhibitory

factor-(CD74+/CD44/C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4) and

IL6-IL6 receptor, which are key in inflammation, adhesion and

immune regulation (Fig. 2E, K and

M). In addition, signaling network inference highlighted

‘RESISTIN’, ‘MK’ and ‘GDF’ pathways as key mediators of

intercellular crosstalk within the TME (Fig. 2L). Collectively, these results

underscore the dual role of M1 macrophages in PTC, mechanistically

associating folate metabolism with pro-tumorigenic inflammation and

immune modulation and identifying them as pivotal regulators of TME

remodeling.

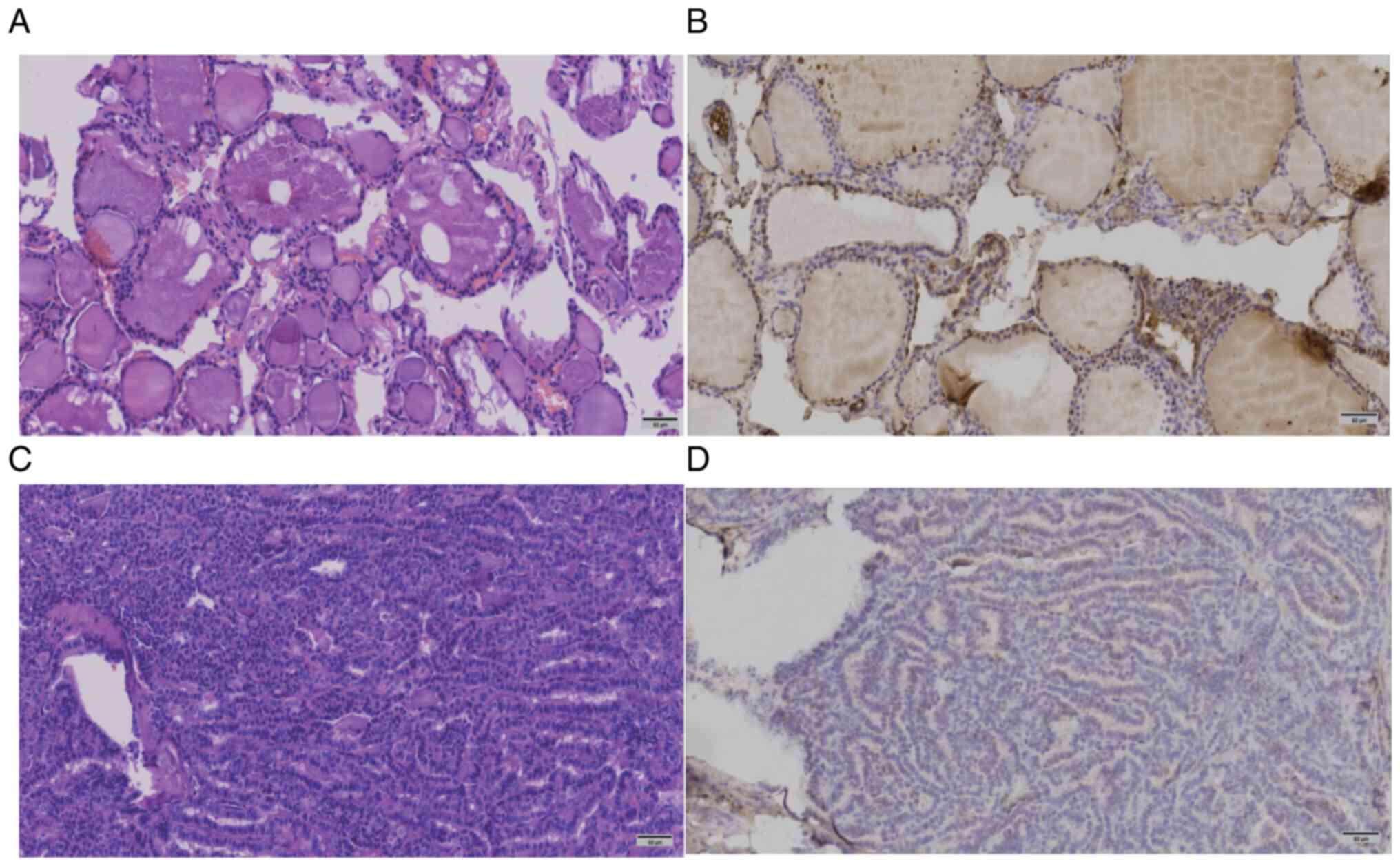

Expression of FOLR3 protein in thyroid

cancer and adjacent normal tissue

IHC revealed that FOLR3 expression was significantly

higher in normal thyroid tissues (H-score, 129.93±50.18) compared

with thyroid cancer tissues (H-score, 99.68±47.67) (Table II; Fig.

3). A paired t-test confirmed that this difference was

statistically significant (P<0.0001; Table II).

| Table II.H-scores of the patients (n=293). |

Table II.

H-scores of the patients (n=293).

| Patient no. | Normal thyroid

tissues | Thyroid cancer

tissues |

|---|

| 1 | 164.55 | 146.37 |

| 2 | 146.00 | 136.58 |

| 3 | 133.02 | 129.21 |

| 4 | 247.31 | 195.57 |

| 5 | 148.17 | 87.76 |

| 6 | 160.78 | 138.36 |

| 7 | 114.05 | 53.49 |

| 8 | 211.47 | 154.97 |

| 9 | 193.39 | 153.36 |

| 10 | 154.94 | 145.04 |

| 11 | 150.71 | 143.13 |

| 12 | 183.65 | 98.63 |

| 13 | 171.79 | 153.39 |

| 14 | 151.49 | 146.88 |

| 15 | 201.25 | 154.38 |

| 16 | 186.21 | 151.62 |

| 17 | 116.70 | 104.32 |

| 18 | 152.38 | 126.82 |

| 19 | 162.38 | 148.82 |

| 20 | 171.70 | 61.32 |

| 21 | 125.82 | 72.99 |

| 22 | 215.35 | 172.70 |

| 23 | 219.23 | 147.34 |

| 24 | 171.05 | 156.03 |

| 25 | 196.15 | 161.93 |

| 26 | 184.15 | 111.95 |

| 27 | 181.24 | 139.55 |

| 28 | 133.28 | 126.86 |

| 29 | 204.96 | 149.66 |

| 30 | 143.99 | 132.18 |

| 31 | 174.22 | 145.96 |

| 32 | 156.80 | 139.17 |

| 33 | 86.04 | 54.02 |

| 34 | 108.69 | 109.10 |

| 35 | 119.19 | 82.42 |

| 36 | 109.45 | 77.76 |

| 37 | 108.59 | 57.18 |

| 38 | 99.96 | 51.16 |

| 39 | 86.40 | 40.47 |

| 40 | 96.69 | 46.96 |

| 41 | 122.83 | 108.76 |

| 42 | 158.93 | 113.31 |

| 43 | 140.82 | 118.09 |

| 44 | 105.50 | 63.45 |

| 45 | 131.70 | 111.66 |

| 46 | 139.03 | 86.48 |

| 47 | 94.88 | 68.67 |

| 48 | 56.94 | 39.40 |

| 49 | 85.17 | 48.56 |

| 50 | 11.55 | 8.62 |

| 51 | 135.13 | 132.38 |

| 52 | 147.64 | 137.57 |

| 53 | 127.17 | 119.15 |

| 54 | 92.66 | 103.77 |

| 55 | 134.85 | 84.52 |

| 56 | 96.37 | 39.76 |

| 57 | 54.15 | 42.18 |

| 58 | 65.47 | 13.09 |

| 59 | 63.74 | 1.07 |

| 60 | 5.88 | 0.18 |

| 61 | 113.42 | 91.81 |

| 62 | 210.17 | 64.71 |

| 63 | 190.18 | 122.17 |

| 64 | 88.44 | 70.45 |

| 65 | 116.35 | 157.87 |

| 66 | 76.91 | 56.08 |

| 67 | 159.75 | 68.34 |

| 68 | 156.54 | 119.36 |

| 69 | 160.64 | 136.02 |

| 70 | 59.53 | 55.13 |

| 71 | 81.79 | 78.75 |

| 72 | 93.73 | 50.22 |

| 73 | 130.00 | 39.09 |

| 74 | 87.28 | 41.11 |

| 75 | 216.87 | 103.31 |

| 76 | 98.67 | 74.03 |

| 77 | 99.00 | 73.30 |

| 78 | 90.94 | 79.29 |

| 79 | 164.41 | 93.89 |

| 80 | 167.83 | 166.5 |

| 81 | 137.57 | 69.51 |

| 82 | 111.62 | 49.47 |

| 83 | 201.42 | 134.27 |

| 84 | 163.93 | 118.29 |

| 85 | 80.09 | 61.97 |

| 86 | 192.61 | 88.74 |

| 87 | 170.62 | 152.33 |

| 88 | 191.49 | 50.53 |

| 89 | 119.56 | 119.22 |

| 90 | 67.67 | 45.43 |

| 91 | 67.53 | 51.54 |

| 92 | 106.34 | 6.95 |

| 93 | 120.59 | 35.01 |

| 94 | 61.15 | 38.78 |

| 95 | 120.41 | 89.81 |

| 96 | 50.26 | 16.43 |

| 97 | 62.52 | 42.29 |

| 98 | 48.86 | 25.90 |

| 99 | 35.35 | 24.36 |

| 100 | 113.82 | 113.06 |

| 101 | 73.47 | 64.73 |

| 102 | 81.64 | 76.59 |

| 103 | 61.18 | 14.07 |

| 104 | 74.41 | 28.97 |

| 105 | 112.23 | 58.89 |

| 106 | 75.94 | 45.13 |

| 107 | 116.07 | 93.56 |

| 108 | 99.80 | 58.09 |

| 109 | 92.19 | 22.33 |

| 110 | 42.86 | 12.04 |

| 111 | 10.30 | 11.21 |

| 112 | 124.12 | 50.37 |

| 113 | 85.12 | 42.66 |

| 114 | 83.75 | 74.22 |

| 115 | 32.02 | 14.77 |

| 116 | 84.79 | 90.94 |

| 117 | 73.23 | 96.52 |

| 118 | 1.33 | 8.67 |

| 119 | 117.84 | 96.20 |

| 120 | 66.44 | 56.91 |

| 121 | 95.26 | 97.71 |

| 122 | 127.92 | 76.75 |

| 123 | 73.33 | 79.05 |

| 124 | 56.06 | 45.97 |

| 125 | 117.35 | 76.76 |

| 126 | 100.10 | 44.13 |

| 127 | 126.63 | 110.81 |

| 128 | 131.09 | 100.99 |

| 129 | 30.80 | 28.38 |

| 130 | 101.37 | 82.66 |

| 131 | 64.22 | 55.62 |

| 132 | 51.98 | 35.75 |

| 133 | 172.32 | 64.74 |

| 134 | 67.35 | 60.24 |

| 135 | 58.16 | 41.55 |

| 136 | 33.55 | 33.89 |

| 137 | 85.79 | 60.32 |

| 138 | 26.20 | 5.91 |

| 139 | 34.32 | 10.65 |

| 140 | 59.71 | 42.04 |

| 141 | 188.62 | 104.21 |

| 142 | 45.80 | 31.95 |

| 143 | 147.59 | 75.87 |

| 144 | 70.59 | 38.08 |

| 145 | 84.66 | 59.77 |

| 146 | 108.32 | 87.49 |

| 147 | 71.66 | 57.89 |

| 148 | 80.62 | 134.46 |

| 149 | 137.00 | 116.60 |

| 150 | 140.84 | 139.98 |

| 151 | 134.13 | 81.44 |

| 152 | 135.82 | 131.41 |

| 153 | 185.20 | 161.26 |

| 154 | 158.57 | 147.50 |

| 155 | 147.48 | 132.21 |

| 156 | 180.52 | 95.11 |

| 157 | 78.38 | 66.41 |

| 158 | 161.33 | 154.09 |

| 159 | 111.38 | 106.17 |

| 160 | 184.15 | 152.06 |

| 161 | 148.90 | 142.03 |

| 162 | 190.60 | 167.59 |

| 163 | 194.39 | 152.33 |

| 164 | 166.85 | 154.07 |

| 165 | 158.80 | 141.93 |

| 166 | 188.04 | 187.25 |

| 167 | 143.03 | 89.98 |

| 168 | 162.27 | 148.97 |

| 169 | 168.05 | 176.93 |

| 170 | 127.95 | 117.53 |

| 171 | 147.88 | 116.69 |

| 172 | 112.18 | 102.63 |

| 173 | 164.60 | 29.74 |

| 174 | 124.81 | 106.56 |

| 175 | 104.00 | 71.29 |

| 176 | 80.54 | 58.33 |

| 177 | 39.82 | 18.88 |

| 178 | 100.87 | 44.71 |

| 179 | 96.21 | 69.35 |

| 180 | 133.71 | 71.09 |

| 181 | 69.68 | 51.30 |

| 182 | 106.75 | 86.33 |

| 183 | 131.84 | 64.39 |

| 184 | 71.89 | 23.83 |

| 185 | 132.16 | 39.71 |

| 186 | 129.86 | 45.19 |

| 187 | 52.52 | 49.63 |

| 188 | 86.69 | 99.01 |

| 189 | 96.55 | 66.90 |

| 190 | 39.05 | 5.49 |

| 191 | 57.76 | 52.49 |

| 192 | 78.92 | 66.92 |

| 193 | 53.93 | 49.64 |

| 194 | 114.65 | 100.65 |

| 195 | 84.82 | 65.47 |

| 196 | 111.75 | 101.47 |

| 197 | 80.33 | 94.78 |

| 198 | 108.18 | 73.45 |

| 199 | 76.27 | 77.60 |

| 200 | 112.31 | 68.72 |

| 201 | 80.01 | 58.27 |

| 202 | 89.42 | 72.15 |

| 203 | 96.58 | 79.57 |

| 204 | 102.38 | 69.58 |

| 205 | 97.33 | 70.65 |

| 206 | 93.90 | 76.41 |

| 207 | 117.50 | 60.98 |

| 208 | 23.55 | 3.58 |

| 209 | 157.45 | 107.52 |

| 210 | 81.05 | 60.24 |

| 211 | 137.02 | 116.14 |

| 212 | 118.78 | 79.55 |

| 213 | 133.41 | 133.66 |

| 214 | 164.76 | 116.36 |

| 215 | 180.06 | 182.92 |

| 216 | 166.59 | 118.32 |

| 217 | 170.52 | 170.16 |

| 218 | 193.79 | 163.37 |

| 219 | 193.36 | 158.70 |

| 220 | 187.24 | 170.76 |

| 221 | 183.74 | 145.64 |

| 222 | 182.94 | 172.33 |

| 223 | 131.85 | 89.28 |

| 224 | 148.43 | 77.22 |

| 225 | 166.30 | 160.53 |

| 226 | 150.27 | 142.50 |

| 227 | 135.90 | 81.77 |

| 228 | 146.95 | 133.12 |

| 229 | 151.41 | 150.12 |

| 230 | 143.85 | 133.38 |

| 231 | 99.93 | 43.97 |

| 232 | 151.49 | 121.59 |

| 233 | 144.99 | 124.87 |

| 234 | 142.00 | 122.68 |

| 235 | 165.83 | 140.79 |

| 236 | 208.44 | 187.60 |

| 237 | 178.17 | 163.92 |

| 238 | 168.91 | 141.85 |

| 239 | 165.80 | 145.45 |

| 240 | 136.95 | 139.40 |

| 241 | 147.78 | 135.69 |

| 242 | 105.73 | 86.53 |

| 243 | 73.78 | 0.95 |

| 244 | 97.68 | 47.81 |

| 245 | 163.53 | 57.35 |

| 246 | 166.40 | 107.74 |

| 247 | 129.13 | 108.89 |

| 248 | 137.95 | 112.03 |

| 249 | 143.59 | 109.13 |

| 250 | 137.34 | 132.70 |

| 251 | 175.34 | 147.97 |

| 252 | 184.94 | 172.82 |

| 253 | 156.07 | 143.52 |

| 254 | 189.84 | 188.35 |

| 255 | 183.57 | 169.42 |

| 256 | 168.51 | 138.99 |

| 257 | 127.93 | 118.84 |

| 258 | 158.56 | 143.35 |

| 259 | 123.80 | 105.50 |

| 260 | 194.29 | 135.53 |

| 261 | 159.92 | 99.10 |

| 262 | 131.32 | 120.29 |

| 263 | 48.63 | 30.04 |

| 264 | 164.66 | 127.32 |

| 265 | 127.74 | 77.67 |

| 266 | 101.59 | 88.66 |

| 267 | 128.55 | 117.84 |

| 268 | 100.90 | 57.06 |

| 269 | 134.81 | 87.24 |

| 270 | 134.47 | 110.14 |

| 271 | 118.35 | 109.63 |

| 272 | 131.51 | 111.68 |

| 273 | 126.47 | 120.74 |

| 274 | 243.09 | 132.76 |

| 275 | 138.70 | 112.34 |

| 276 | 215.87 | 91.34 |

| 277 | 163.43 | 113.18 |

| 278 | 192.07 | 133.95 |

| 279 | 177.21 | 123.38 |

| 280 | 174.17 | 112.87 |

| 281 | 152.79 | 121.19 |

| 282 | 130.25 | 125.07 |

| 283 | 182.06 | 170.84 |

| 284 | 163.29 | 152.19 |

| 285 | 142.50 | 133.29 |

| 286 | 135.76 | 112.89 |

| 287 | 162.53 | 132.69 |

| 288 | 164.47 | 133.78 |

| 289 | 114.49 | 115.11 |

| 290 | 183.97 | 136.89 |

| 291 | 158.09 | 88.39 |

| 292 | 98.89 | 63.07 |

| 293 | 160.68 | 47.88 |

Association analysis of FOLR3 and

clinicopathological factors in thyroid cancer

The expression levels of FOLR3 were significantly

associated with capsule invasion, neurofibrillary invasion,

striated muscle cell invasion and pT stage (P<0.05) and there

was no significant association with sex, age, tumor location, tumor

focality, histological type, vascular invasion or pN stage

(P<0.05) (Table III). FOLR3

was commonly downregulated or absent in cases with capsule,

rhabdomyocyte invasion or larger tumor burden, suggesting that

FOLR3 could serve as an indicator of focal invasion in thyroid

cancer.

| Table III.Association between FOLR3 expression

and clinicopathological parameters in patients with thyroid cancer

(n=293). |

Table III.

Association between FOLR3 expression

and clinicopathological parameters in patients with thyroid cancer

(n=293).

|

|

| FOLR3

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathological

feature | No. of cases | Low, n | High, n | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.465 |

|

Male | 51 | 29 | 22 |

|

|

Female | 242 | 124 | 118 |

|

| Age, years |

|

|

| 0.165 |

|

≤65 | 282 | 145 | 137 |

|

|

>65 | 11 | 8 | 3 |

|

| Tumor location |

|

|

| 0.473 |

|

Unilateral | 255 | 129 | 126 |

|

|

Bilateral | 38 | 18 | 20 |

|

| Histological

type |

|

|

| 0.832 |

|

Papillary carcinoma | 287 | 145 | 142 |

|

|

Follicular carcinoma | 3 | 1 | 2 |

|

|

Anaplastic cancer | 3 | 1 | 2 |

|

| Tumor focality |

|

|

| 0.446 |

| Single

lesion | 165 | 80 | 85 |

|

|

Multiple lesions | 128 | 67 | 61 |

|

| Capsule

invasion |

|

|

| 0.042a |

| No | 102 | 45 | 57 |

|

|

Yes | 191 | 108 | 83 |

|

| Rhabdomyocyte

invasion |

|

|

| 0.006a |

|

Yes | 285 | 145 | 140 |

|

| No | 8 | 8 | 0 |

|

| pT stage |

|

|

| 0.047a |

| 1 | 272 | 141 | 131 |

|

| 2 | 14 | 5 | 9 |

|

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

|

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

|

| pN stage |

|

|

| 0.864 |

| 0 | 168 | 87 | 81 |

|

| 1 | 125 | 66 | 59 |

|

| Vascular

invasion |

|

|

| 0.123 |

| No | 287 | 148 | 139 |

|

|

Yes | 6 | 5 | 1 |

|

| Perineural

invasion |

|

|

| 0.025a |

| No | 284 | 145 | 139 |

|

|

Yes | 9 | 8 | 1 |

|

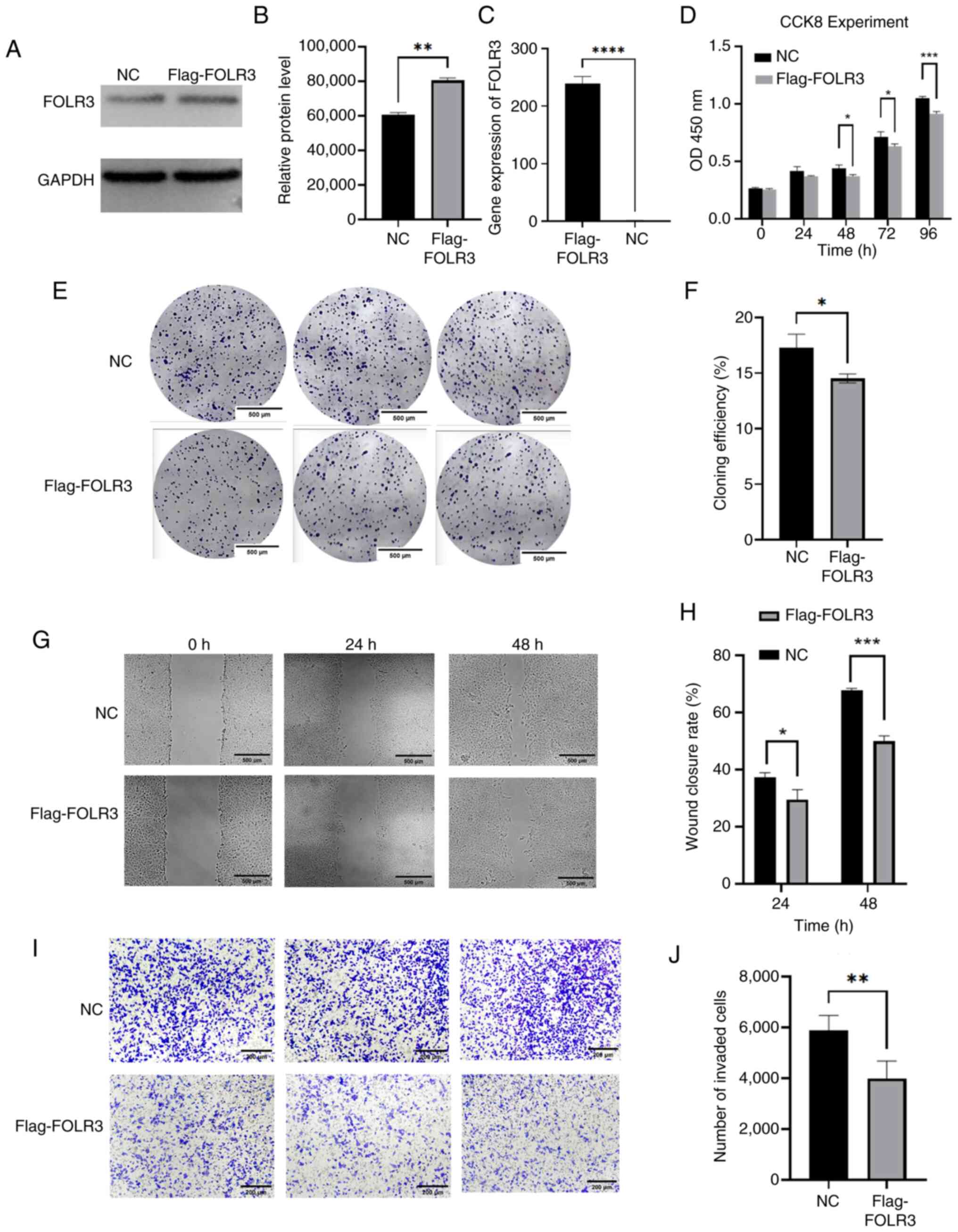

FOLR3 inhibits proliferation, invasion

and migration of thyroid cancer TPC-1 cells

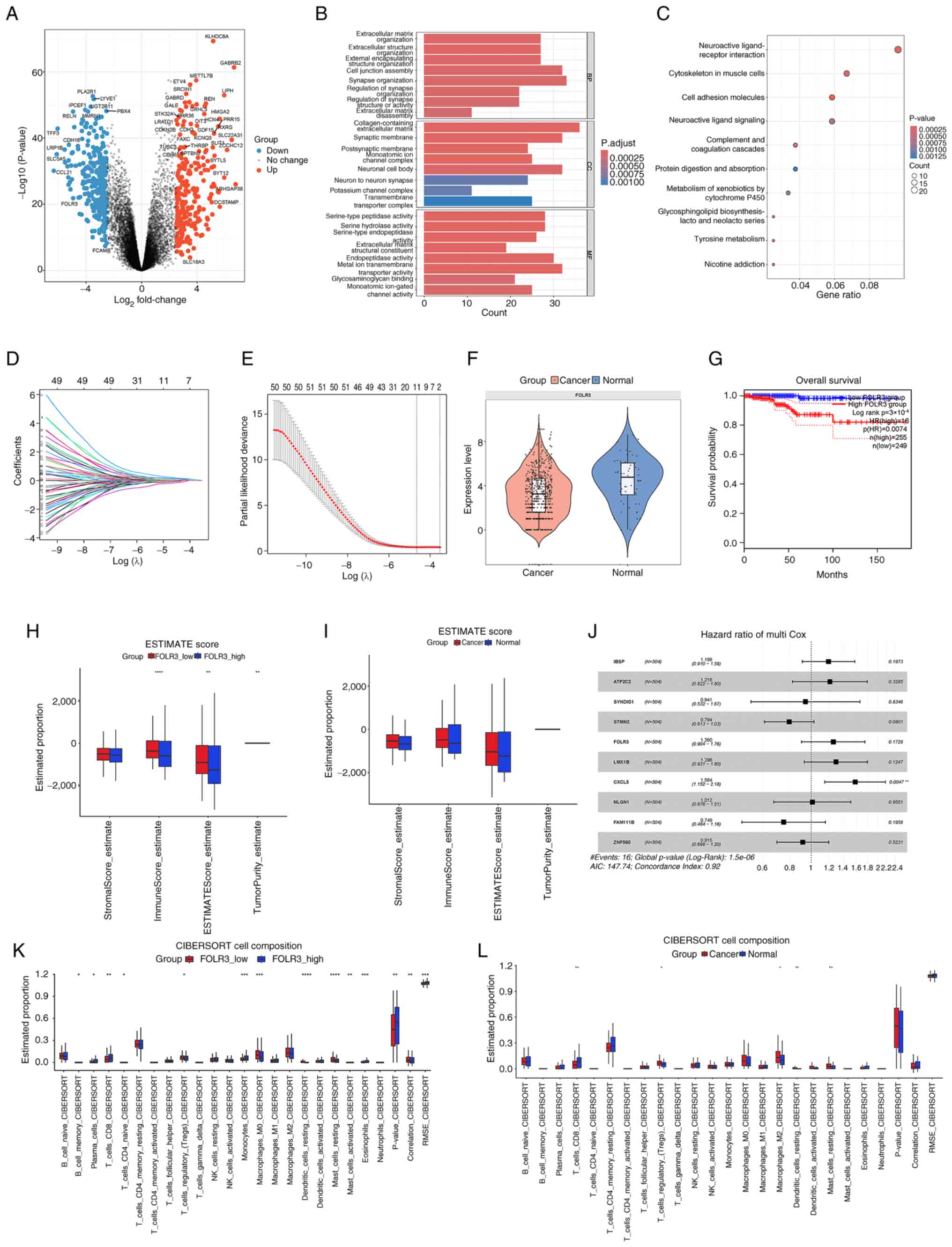

The western blotting analysis (Fig. 4A and B) confirmed successful

overexpression of FOLR3 protein in TPC-1 cells of the Flag-FOLR3

group compared with the NC (P<0.01). RT-qPCR results

demonstrated a significant upregulation of FOLR3 mRNA expression in

the Flag-FOLR3 group (P<0.0001; Fig.

4C). Colony formation assays demonstrated the clonogenic

ability of Flag-FOLR3 group was significantly lower compared with

that of NC group (P<0.05), indicating that FOLR3 overexpression

impaired the proliferative capacity of TPC-1 cells (Fig. 4E and F). The results of the scratch

assay demonstrated cell migration was significantly attenuated in

the Flag-FOLR3 group compared with the NC group at both 24

(P<0.05) and 48 h (P<0.001), confirming that FOLR3

overexpression suppresses the migratory ability of TPC-1 cells

(Fig. 4G and H). Similarly,

Transwell invasion assays indicated that the invasive capacity of

TPC-1 cells was significantly reduced in the Flag-FOLR3 group after

24 h (P<0.01), indicating that FOLR3 overexpression

significantly inhibits cell invasion (Fig. 4I and J). CCK-8 assays indicated that

TPC-1 cell proliferation was significantly inhibited at 48, 72 and

96 h after FOLR3 overexpression (P<0.05; Fig. 4D).

| Figure 4.Functional characterization of FOLR3

in thyroid cancer cells in vitro. (A) Protein expression

levels of FOLR3 assessed using western blotting and (B)

semi-quantification. (C) Relative mRNA relative expression levels

of FOLR3 by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (D) CCK-8 for

0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. (E) Colony forming ability evaluated using

colony formation assay and (F) quantification (magnification, ×4).

(G) Cell migratory capacity analyzed using a wound healing assay

and (H) quantification (magnification, ×20). (I) Invasive potential

determined using Transwell invasion assay and (J) quantification

(magnification, ×10). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. FOLR3, folate receptor γ; CCK-8, Cell Counting

Kit-8; NC, negative control. |

FOLR3 overexpression suppresses the

progression of thyroid cancer by inactivating the STAT3/MAPK

signaling pathways and subsequently reprogramming folate

metabolism

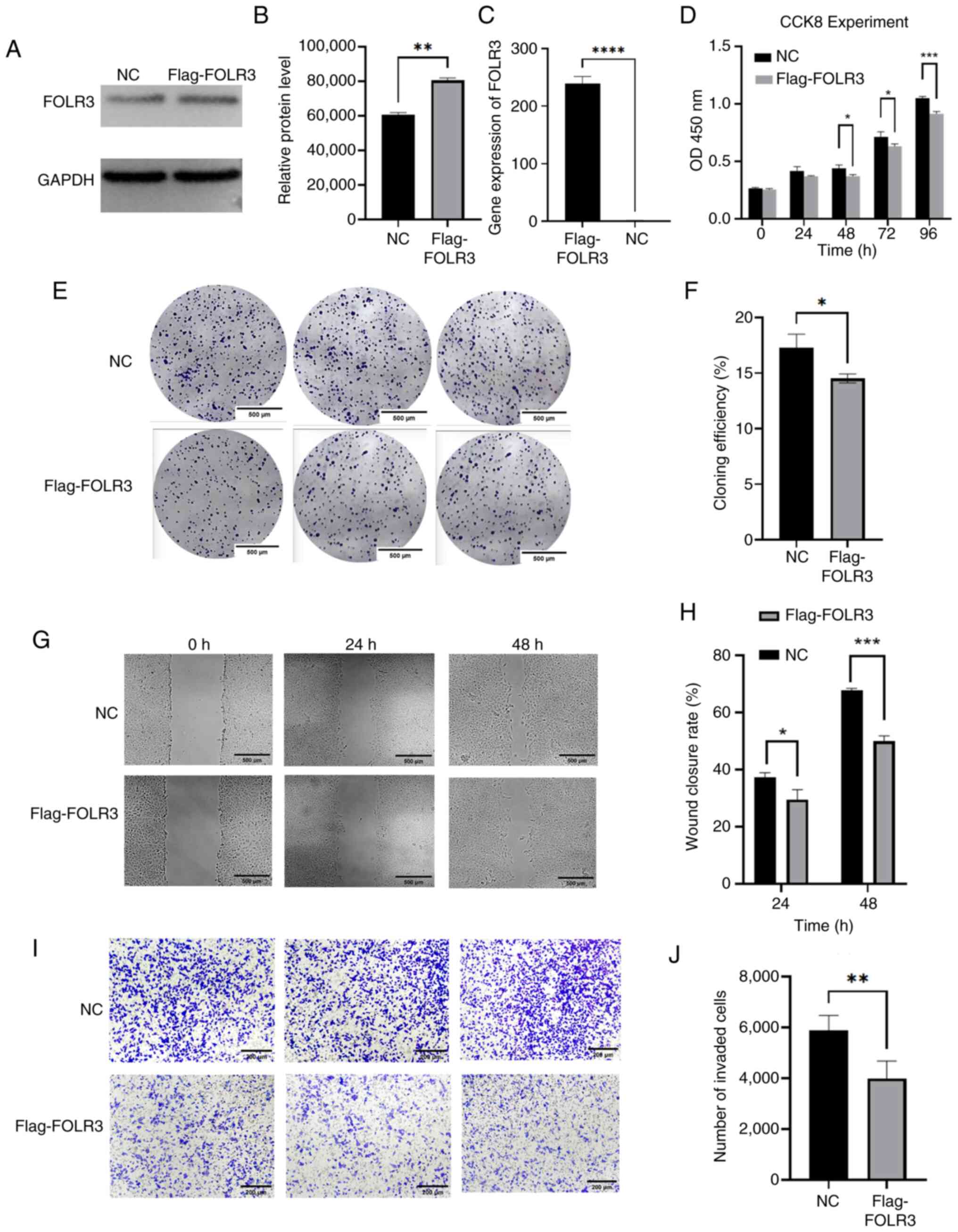

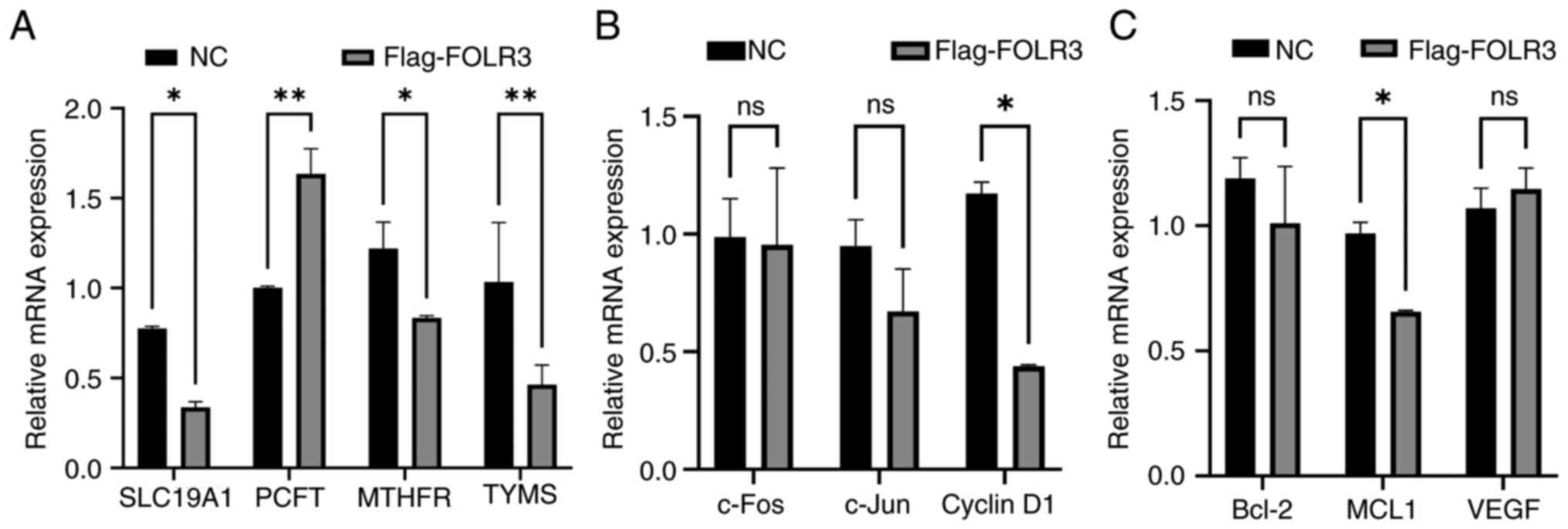

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the

tumor-suppressive role of FOLR3, the present study first

investigated its impact on folate metabolism using qPCR analysis.

Notably, FOLR3 overexpression significantly downregulated the mRNA

level of the folate transporter gene solute carrier family 19

member 1 and upregulated that of solute carrier family 46 member 1

(P<0.05). Concurrently, expression levels of key folate

metabolic enzyme genes, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and

thymidylate synthase, were significantly downregulated (P<0.05).

These results indicate that FOLR3 overexpression induces notable

reprogramming of folate metabolism in thyroid cancer cells

(Fig. 5A), which may contribute to

the inhibition of tumor progression.

| Figure 5.FOLR3 overexpression promotes folate

metabolism and activates oncogenic signaling pathways in thyroid

cancer cells. (A) mRNA expression levels of folate

metabolism-related genes (SLC19A1, PCFT, MTHFR and TYMS) after

FOLR3 overexpression. (B) mRNA expression levels of MAPK pathway

downstream genes (c-Fos, c-Jun and cyclin D1) after FOLR3

overexpression. (C) mRNA expression levels of STAT3 pathway

downstream genes after FOLR3 overexpression. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. ns, not significant; FOLR3, folate receptor γ; TYMS,

thymidylate synthase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase;

SLC19A1, solute carrier family 19 member 1; PCFT, proton-coupled

folate transporter; c-FOS, Fos proto-oncogenes, AP-1 transcription

factor subunit; MCL1, myeloid cell leukemia-1; NC, negative

control. |

The present study further examined whether FOLR3

modulates oncogenic signaling pathways by assessing the expression

levels of downstream effectors of STAT3 and MAPK signaling. RT-qPCR

revealed that overexpression of FOLR3 significantly downregulated

both mRNA and protein levels of myeloid cell leukemia-1 (MCL1), an

anti-apoptotic gene downstream of STAT3 (P<0.05). Similarly,

expression levels of cyclin D1, a key cell cycle regulator mediated

by the MAPK pathway, were also significantly suppressed (P<0.05;

Fig. 5B and C). These findings

demonstrated that FOLR3 overexpression effectively inhibits the

activity of both STAT3 and MAPK signaling pathways. Collectively,

the present study results suggest that FOLR3 constrains thyroid

cancer development through dual mechanisms: Inactivation of STAT3

and MAPK signaling pathways and concomitant reprogramming of folate

metabolism.

Discussion

Thyroid cancer is one of the fastest-growing

malignancies in recent years, with a notably higher incidence among

women (33,34). Despite the notable improvements in

early diagnosis and treatment, patients with advanced thyroid

cancer still face poor prognosis due to tumor invasiveness and

metastasis (35,36). Therefore, understanding the

molecular mechanisms underlying thyroid cancer and identifying

novel biomarkers are key to the improvement of diagnosis, treatment

and prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, the present study

investigated the expression level of FOLR3 in thyroid cancer and

its association with clinicopathological features, for the first

time. FOLR3, a member of the folate receptor family, has been

implicated in various cancer types (37–39).

In tongue cancer, FOLR3 is an upregulated immune-related target

associated with patient prognosis (37). Similarly, its expression is

upregulated in metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma compared to

primary tumors, suggesting a potential role in promoting metastatic

disease (38). Furthermore,

transcriptomic analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from

patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma revealed FOLR3

as one of the differentially expressed genes, indicating its

systemic involvement in cancer-related immune responses (39). The present bioinformatics analysis

and experimental data revealed that FOLR3 is significantly

downregulated in thyroid cancer tissues compared with normal tissue

and its high expression was associated with worse overall survival.

The seemingly contradictory link between FOLR3 expression and

clinical prognosis may be explained by its cell type-specific

functions within the tumor microenvironment. While FOLR3 is

typically downregulated in cancer cells (a tumor-suppressive

effect), its high overall levels in tumors mainly comes from

tumor-infiltrating immune cells such as macrophages. This

immune-derived FOLR3 enrichment is indicative of an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that promotes disease

progression and is associated with poorer patient survival.

Therefore, FOLR3 exhibits a dual function, acting as a putative

tumor suppressor within cancer cells while serving as a biomarker

and functional driver of an immune-favorable, pro-tumorigenic niche

(12,37–41).

Therefore, FOLR3 has the potential for targeted therapy.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed a

significant expansion of M1 macrophages with heightened folate

metabolism in the TME of PTC. These folate-high M1 macrophages

drive TME remodeling and promote pro-tumor inflammatory responses

through activation of immune-inflammatory pathways and enhanced

intercellular communication. Mechanistically, FOLR3 suppresses

thyroid cancer growth by inactivating the STAT3 and MAPK signaling

pathways through downregulation of their key downstream oncogenes,

MCL1 and cyclin D1, ultimately leading to reprogramming of folate

metabolism. Notably, FOLR3 has also been reported to influence

other cancer types. Recent studies have reported that FOLR3

undergoes hypomethylation in the blood of patients with non-small

cell lung cancer and lung adenocarcinoma, suggesting that FOLR3

hypomethylation could serve as an early diagnostic marker for these

cancers (12,40). Furthermore, high expression of FOLR3

in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma after

chemotherapy has been reported to influence subsequent treatment

strategies (41). These findings

across cancer types reinforce the biological and clinical relevance

of FOLR3 and support the present study results highlighting its

importance in thyroid cancer.

The human body expresses three isoforms of folate

receptors (FOLRs): FOLR1, FOLR2 and FOLR3, which have distinct

distributions, structures and functions. Both FOLR1 and FOLR2 are

glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane proteins that

lack transmembrane domains, whereas FOLR3 is secreted into

extracellular compartments, such as blood and breast milk, in a

soluble form due to the absence of a GPI-anchoring signal (42,43).

FOLR1 mainly facilitates folate endocytosis to support classical

folate-dependent proliferative pathways. Although FOLR1 is

upregulated in various types of cancers including ovarian cancer,

Non-Small Cell Lung cancer and rectal cancer, and is generally

associates with accelerated tumor progression and poor prognosis,

its specific role and mechanisms in thyroid cancer remain to be

elucidated in future studies (44–47).

Currently, most folate receptor-targeted drugs and diagnostic

technologies focus on FOLR1. High expression level of

membrane-bound FOLR1 is a recognized predictor of targeted therapy

sensitivity, while soluble FOLR3 levels may be associated with

treatment resistance (45,48). The present study identified reduced

expression levels of FOLR3 in thyroid cancer, which appears to

specifically reflect malignant progression. FOLR3 may influence

carcinogenesis through the folate metabolism-signaling axis and

modulate local folate availability via epigenetic regulation of

soluble folate pools. Further research could explore ‘metabolic

compensation’ strategies using FOLR3 for aggressive thyroid cancer

with poor prognosis, highlighting its therapeutic potential. Since

FOLR3 is secreted into the bloodstream, it may serve as a

non-invasive biomarker in liquid biopsies. For instance,

hypomethylation of FOLR3 in the blood of patients with lung cancer

suggests its utility as an early diagnostic marker (12).

However, whether FOLR3 can be used for thyroid

cancer diagnosis via liquid biopsy requires further validation.

Theoretically, blood-based FOLR3 levels may be associated with

tumor burden, metabolic activity or disease stage. While FOLR3

alone may not be sufficient for diagnosis, its combination with

other markers, such as CA-125, human epididymis protein 4 or

circulating tumor DNA mutations, could significantly enhance

diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity (49–51).

Although the present study provided evidence supporting the

tumor-suppressive role of FOLR3 in thyroid cancer, several

limitations should be acknowledged. The clinical samples, despite

having detailed pathological annotations, were obtained from a

single center with a limited cohort size (n=293). Validation in a

larger, multi-center cohort is warranted to enhance the statistical

power and generalizability of the association between FOLR3

expression and clinicopathological characteristics. Furthermore,

the lack of in vivo validation using animal models, such as

xenograft or orthotopic models, restricts the comprehensive

confirmation of its tumor-suppressive function within a more

complex physiological context. The present study primarily focused

on the role of FOLR3 in thyroid cancer itself, while its

interactions with the tumor immune microenvironment, stromal

components and other folate metabolism-related genes have not been

extensively investigated. In the future, FOLR3 may have the

potential to serve as a diagnostic biomarker and a novel

therapeutic target in thyroid cancer; however, further research is

warranted to explore its clinical applicability in both treatment

and prognosis assessment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Xiaokai Liu (Chi

Feng No. 2 Senior High School, Chifeng, China) for their assistance

in polishing the English language and grammar of the

manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Chifeng Municipal Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. SZR2023063).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JC, YL and LT conceptualized the present study; JC,

YL and XD devised the methodology. JC and XD; JC, YL and XD

validated the data. JC, LH, YL and LT analyzed data. JC, YL and BL

performed the experiments. YL and LT prepared the resources. JC, YL

and XD curated the data. JC, YL and XD visualized the data. JC, YL

and XD prepared the original draft of the manuscript. JC, YL, LH

and LT reviewed and edited the manuscript. LT supervised the

present study. YL and LT contributed to project administration. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript. JC and YL confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Scientific

Research Ethics Committee of Chifeng City Hospital (approval no.

CK2023037; approval on 20 April 2023; Chifeng, China). The present

study is retrospective in nature, and the informed consent

requirement was waived by the Ethics Committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence

tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate

content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Chen MM, Luu M, Sacks WL, Orloff L,

Wallner LP, Clair JM, Pitt SC, Ho AS and Zumsteg ZS: Trends in

incidence, metastasis, and mortality from thyroid cancer in the USA

from 1975 to 2019: A population-based study of age, period, and

cohort effects. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 13:188–195. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Boucai L, Zafereo M and Cabanillas ME:

Thyroid cancer: A review. JAMA. 331:425–435. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shen F, Wu M, Ross JF, Miller D and Ratnam

M: Folate receptor type gamma is primarily a secretory protein due

to lack of an efficient signal for glycosylphosphatidylinositol

modification: Protein characterization and cell type specificity.

Biochemistry. 34:5660–5665. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang HC, Huo YN and Lee WS: Folic acid

prevents the progesterone-promoted proliferation and migration in

breast cancer cell lines. Eur J Nutr. 59:2333–2344. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Moazzen S, Dolatkhah R, Tabrizi JS,

Shaarbafi J, Alizadeh BZ, de Bock GH and Dastgiri S: Folic acid

intake and folate status and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 37:1926–1934. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sadeghi Jam Z, Tafvizi F, Khodarahmi P,

Jafari P and Baghbani-Arani F: Cisplatin-loaded UiO-66-NH2

functionalized with folic acid enhances apoptotic activity and

antiproliferative effects in MDA-MB-231 breast and A2780 ovarian

cancer cells: An in vitro study. Heliyon. 11:e426852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Crider KS, Yang TP, Berry RJ and Bailey

LB: Folate and DNA methylation: A review of molecular mechanisms

and the evidence for Folate's role. Adv Nutr. 3:21–38. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Petersen LF, Brockton NT, Bakkar A, Liu S,

Wen J, Weljie AM and Bismar TA: Elevated physiological levels of

folic acid can increase in vitro growth and invasiveness of

prostate cancer cells. BJU Int. 109:788–795. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ullevig SL, Bacich DJ, Gutierrez JM,

Balarin A, Lobitz CA, O'Keefe DS and Liss MA: Feasibility of

dietary folic acid reduction intervention for men on active

surveillance for prostate cancer. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 44:270–275.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li JT, Yang H, Lei MZ, Zhu WP, Su Y, Li

KY, Zhu WY, Wang J, Zhang L, Qu J, et al: Dietary folate drives

methionine metabolism to promote cancer development by stabilizing

MAT IIA. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Qu Y, Zhang X, Qiao R, Di F, Song Y, Wang

J, Ji L, Zhang J, Gu W, Fang Y, et al: Blood FOLR3 methylation

dysregulations and heterogeneity in non-small lung cancer highlight

its strong associations with lung squamous carcinoma. Respir Res.

25:592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Holm J and Hansen SI: Characterization of

soluble folate receptors (folate binding proteins) in humans.

Biological roles and clinical potentials in infection and

malignancy. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 1868:1404662020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu MH, Luo JD, Wang WC, Chang TH, Hwang

WL, Lee KH, Liu SY, Yang JW, Chiou CT, Chang CH and Chiang WF: Risk

analysis of malignant potential of oral verrucous hyperplasia: A

follow-up study of 269 patients and copy number variation analysis.

Head Neck. 40:1046–1056. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hansen MF, Greibe E, Skovbjerg S, Rohde S,

Kristensen AC, Jensen TR, Stentoft C, Kjær KH, Kronborg CS and

Martensen PM: Folic acid mediates activation of the pro-oncogene

STAT3 via the Folate Receptor alpha. Cell Signal. 27:1356–1368.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ma Q, Geng K, Xiao P and Zeng L:

Identification and prognostic value exploration of radiotherapy

sensitivity-Associated genes in Non-Small-cell lung cancer. Biomed

Res Int. 2021:59638682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zee RY, Rose L, Chasman DI and Ridker PM:

Genetic variation of fifteen folate metabolic pathway associated

gene loci and the risk of incident head and neck carcinoma: The

Women's Genome Health Study. Clin Chim Acta. 418:33–36. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Liao T, Zeng Y, Xu W, Shi X, Shen C, Du Y,

Zhang M, Zhang Y, Li L, Ding P, et al: A spatially resolved

transcriptome landscape during thyroid cancer progression. Cell Rep

Med. 6:1020432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B and Wu D, Ritchie

ME, Phipson B and Wu D: Limma powers differential expression

analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids

Res. 43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2:1001412021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li X, Zhang L, Liu C, He Y, Li X, Xu Y, Gu

C, Wang X, Wang S, Zhang J and Liu J: Construction of mitochondrial

quality regulation genes-related prognostic model based on

bulk-RNA-seq analysis in multiple myeloma. Biofactors.

51:e21352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Huang X, Sun Y, Song J, Huang Y, Shi H,

Qian A, Cao Y, Zhou Y and Wang Q: Prognostic value of fatty acid

metabolism-related genes in colorectal cancer and their potential

implications for immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 14:13014522023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ning X, Li R, Zhang B, Wang Y, Zhou Z, Ji

Z, Lyu X and Chen Z: Immune score indicator for the survival of

melanoma patients based on tumor microenvironment. Int J Gen Med.

14:10397–10416. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhao AY, Unterman A, Abu Hussein NS,

Sharma P, Nikola F, Flint J, Yan X, Adams TS, Justet A, Sumida TS,

et al: Single-cell analysis reveals novel immune perturbations in

fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

210:1252–1266. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li Y, Li F, Xu L, Shi X, Xue H, Liu J, Bai

S, Wu Y, Yang Z, Xue F, et al: Single cell analyses reveal the PD-1

blockade response-related immune features in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Theranostics. 14:3526–3547. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, Chang

I, Ramos R, Kuan CH, Myung P, Plikus MV and Nie Q: Inference and

analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun.

12:10882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Huang A, Sun Z, Hong H, Yang Y, Chen J,

Gao Z and Gu J: Novel hypoxia- and lactate metabolism-related

molecular subtyping and prognostic signature for colorectal cancer.

J Transl Med. 22:5872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX,

Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR and Heimbach JK: Diagnosis,

staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice

guidance by the American association for the study of liver

diseases. Hepatology. 68:723–750. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Humphries MP, Maxwell P and Salto-Tellez

M: QuPath: The global impact of an open source digital pathology

system. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 19:852–859. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wen Z, Luo D, Wang S, Rong R, Evers BM,

Jia L, Fang Y, Daoud EV, Yang S, Gu Z, et al: Deep Learning-Based

H-Score quantification of immunohistochemistry-stained images. Mod

Pathol. 37:1003982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Siena S, Raghav K, Masuishi T, Yamaguchi

K, Nishina T, Elez E, Rodriguez J, Chau I, Di Bartolomeo M,

Kawakami H, et al: HER2-related biomarkers predict clinical

outcomes with trastuzumab deruxtecan treatment in patients with

HER2-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer: Biomarker analyses of

DESTINY-CRC01. Nat Commun. 15:102132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li M, Hu M, Jiang L, Pei J and Zhu C:

Trends in cancer incidence and potential associated factors in

China. JAMA Netw Open. 7:e24403812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Miranda-Filho A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bray

F, Cao B, Franceschi S, Vaccarella S and Dal Maso L: Thyroid cancer

incidence trends by histology in 25 countries: A population-based

study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9:225–234. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tao Z, Ding Z, Guo B, Fan Y and Deng X:

Influence factors and survival outcomes of different invasion sites

in locally advanced thyroid cancer and new site-based risk

stratification system. Endocrine. 88:501–510. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yu X, Deng Q, Gao X, He L, Hu D and Yang

L: A prognostic nomogram for distant metastasis in thyroid cancer

patients without lymph node metastasis. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 16:15237852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lv X and Yu X: Signatures and prognostic

values of related immune targets in tongue cancer. Front Surg.

9:9523892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Davidson B, Abeler VM, Førsund M, Holth A,

Yang Y, Kobayashi Y, Chen L, Kristensen GB, Shih IeM and Wang TL:

Gene expression signatures of primary and metastatic uterine

leiomyosarcoma. Hum Pathol. 45:691–700. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bin-Alee F, Arayataweegool A,

Buranapraditkun S, Mahattanasakul P, Tangjaturonrasme N, Hirankarn

N, Mutirangura A and Kitkumthorn N: Transcriptomic analysis of

peripheral blood mononuclear cells in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma patients. Oral Dis. 27:1394–1402. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Qiao R, Di F, Wang J, Wei Y, Xu T, Dai L,

Gu W, Han B and Yang R: Identification of FUT7 hypomethylation as

the blood biomarker in the prediction of early-stage lung cancer. J

Genet Genomics. 50:573–581. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li L, Wang R, He S, Shen X, Kong F, Li S,

Zhao H, Lian M and Fang J: The identification of induction

chemo-sensitivity genes of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and

their clinical utilization. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

275:2773–2781. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

O'Byrne MR, Au KS, Morrison AC, Lin JI,

Fletcher JM, Ostermaier KK, Tyerman GH, Doebel S and Northrup H:

Association of folate receptor (FOLR1, FOLR2, FOLR3) and reduced

folate carrier (SLC19A1) genes with meningomyelocele. Birth Defects

Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 88:689–694. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Grarup N, Sulem P, Sandholt CH,

Thorleifsson G, Ahluwalia TS, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjarnason H,

Gudbjartsson DF, Magnusson OT, Sparsø T, et al: Genetic

architecture of vitamin B12 and folate levels uncovered applying

deeply sequenced large datasets. PLoS Genet. 9:e10035302013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Nawaz FZ and Kipreos ET: Emerging roles

for folate receptor FOLR1 in signaling and cancer. Trends

Endocrinol Metab. 33:159–174. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Mai J, Wu L, Yang L, Sun T, Liu X, Yin R,

Jiang Y, Li J and Li Q: Therapeutic strategies targeting folate

receptor α for ovarian cancer. Front Immunol. 14:12545322023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Matsunaga Y, Yamaoka T, Ohba M, Miura S,

Masuda H, Sangai T, Takimoto M, Nakamura S and Tsurutani J: Novel

Anti-FOLR1 Antibody-drug conjugate MORAb-202 in breast cancer and

non-Small cell lung cancer cells. Antibodies (Basel). 10:62021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen CI, Li WS, Chen HP, Liu KW, Tsai CJ,

Hung WJ and Yang CC: High expression of folate receptor alpha

(FOLR1) is associated with aggressive tumor behavior, poor response

to chemoradiotherapy, and worse survival in rectal cancer. Technol

Cancer Res Treat. 21:153303382211417952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Varaganti P, Buddolla V, Lakshmi BA and

Kim YJ: Recent advances in using folate receptor 1 (FOLR1) for

cancer diagnosis and treatment, with an emphasis on cancers that

affect women. Life Sci. 326:121802M2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Medina JE, Annapragada AV, Lof P, Short S,

Bartolomucci AL, Mathios D, Koul S, Niknafs N, Noë M, Foda ZH, et

al: Early detection of ovarian cancer Using Cell-Free DNA

fragmentomes and protein biomarkers. Cancer Discov. 15:105–118.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Muinao T, Deka Boruah HP and Pal M:

Multi-biomarker panel signature as the key to diagnosis of ovarian

cancer. Heliyon. 5:e028262019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Heitz F, Lakis S, Harter P, Heikaus S,

Sehouli J, Talwar J, Menon R, Ataseven B, Bertrand M, Schneider S,

et al: Cell-free tumor DNA, CA125 and HE4 for the objective

assessment of tumor burden in patients with advanced high-grade

serous ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 17:e02627702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|