Introduction

Peritoneal metastases (PM), typically originating

from colorectal cancer (1), gastric

cancer (2,3), ovarian cancer (4), pancreatic cancer (5) and other abdominal tumors, are

typically regarded as the terminal stage of cancer (6). Uncontrolled malignant ascites (MA) is

the main complication of PM, leading to abdominal distension,

abdominal pain, dyspnea, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and

decreased mobility, which seriously affects quality of life

(7). The effectiveness of existing

treatment methods for PM, including extended frequent high-volume

puncture drainage, peritoneal venous shunt, diuretics, systemic

chemotherapy, intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy and immunotherapy,

remains limited and does not meet the needs of patients. Given the

significantly higher incidence of renal injury observed in the

cisplatin group in the present study, clinicians should be cautious

about nephrotoxicity when considering this agent for high-risk

patients with PM.

Hyperthermic IP chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a

specialized treatment method that targets and directly eliminates

malignant cells within the abdominal cavity by circulating heated

chemotherapy drugs within the peritoneal cavity, especially in

patients who have experienced systemic therapy failure (8,9). This

technique aims to eliminate free cancer cells, fibrin and other

cellular debris by flushing these substances out of the body, which

can reduce adhesion. Additionally, HIPEC can enhance the absorption

and sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy drugs, increasing

the penetration of chemotherapy at the peritoneal surface,

resulting in efficient tumor cell death for advanced peritoneal

cavity cancers (10). In 1980,

Spratt first reported (11) the use

of HIPEC specifically for the treatment of abdominal and pelvic

malignant tumors, and residual tumors, and this technique has

proven to be a promising treatment modality (12). HIPEC is used to treat

gastrointestinal cancer, ovarian cancer, pseudomyxoma peritonei and

other peritoneal cancer types (13,14).

However, this technology is currently underdeveloped, and there are

no clear guidelines for drug selection.

Endostar is a vascular endothelial growth factor

(VEGF) inhibitor that has been shown to significantly reduce

visible ascites formation and tumor burden (15). VEGF overexpression is commonly

observed in malignant cancer metastases affecting the abdominal

region (16). Prospective

multicenter clinical studies have confirmed the efficacy of

Endostar and cisplatin injections for controlling malignant pleural

effusions (17,18). In recent years, docetaxel has also

been reported to control MA (19).

In addition, hyperthermia is known to enhance tumor perfusion and

increase drug penetration after IP delivery (20).

The present study retrospectively assessed the

effectiveness and adverse effects of HIPEC using

docetaxel/cisplatin, combined with IP Endostar injections, for

treating MA in patients who had failed at least two rounds of

systemic chemotherapy regimens. The findings provide valuable

insights for improving and developing new therapies for this

condition.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

The present retrospective study involved patients

treated between July 2019 and December 2020 at the Sandun Campus of

Zhejiang Hospital (Hangzhou, China). The eligibility criteria were

as follows: i) Patients must have been diagnosed with a malignant

tumor, with evidence of cytology or tumor cells in an ascites cell

block; ii) patients must have previously undergone systemic

chemotherapy of second line or higher, and not undergone a HIPEC

procedure in the past 6 months; iii) patients must not have

received docetaxel, cisplatin or Endostar before receiving the

protocol under investigation; iv) hemoglobin level must be ≥90 g/l

(normal range, 120–160 g/l for women and 130–170 g/l for men); v)

absolute neutrophil count must be ≥1.5×109/l (normal

range, 1.8–7.7×109/l); vi) white blood cell count must

be >3.5×109/l (normal range,

4.0–10.0×109/l); vii) platelet count must be

≥85×109/l (normal range, 150–400×109/l);

viii) total bilirubin must be ≤1.5 times the upper limit of normal

(ULN) (normal range, 3.4–20.5 µmol/l or 0.2–1.2 mg/dl); ix)

aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase must both

be ≤2.5 times the ULN (normal range for AST, 8–40 U/l; normal range

for ALT, 7–56 U/l); x) patients must have an expected survival time

of >3 months; and xi) patients should have failed at least two

rounds of systemic chemotherapy regimens. The exclusion criteria

were: i) Uncontrolled central nervous system metastases with

manifestations of intracranial hypertension; ii) bleeding tendency,

especially marked gastrointestinal bleeding within the past 4

weeks, or currently undergoing thrombolytic or anticoagulant

therapy; iii) prior IP infusion of docetaxel, cisplatin or Endostar

within 6 months, or concurrent participation in other clinical

studies; iv) myocardial infarction within the past 6 months, or

current unstable angina pectoris or cardiac insufficiency; v)

severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and/or respiratory

failure, or severe intestinal adhesions; vi) currently uncontrolled

severe infection; vii) known allergy to the investigational drug(s)

or their excipients; viii) fertile patients unwilling to adopt

contraception, and pregnant or lactating women; ix) poor compliance

or diagnosed with significant psychiatric disorders causing lack of

self-control.

All patients provided written informed consent prior

to catheterization and underwent HIPEC via abdominal puncture as

part of routine clinical treatment for malignant ascites. This

study was approved by the Scientific Research Board of Zhejiang

Hospital, who waived the requirement for informed patient consent

for study participation.

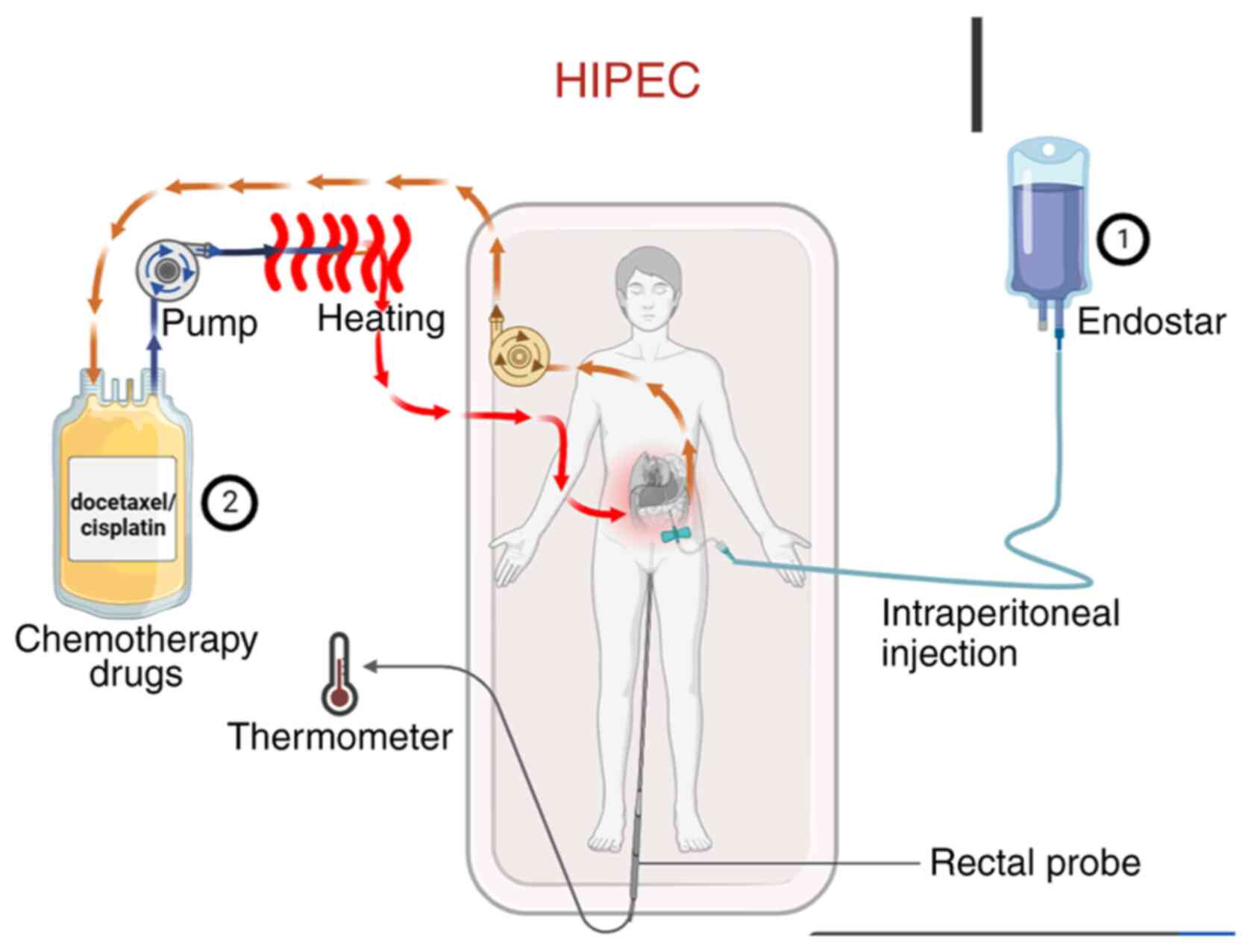

Treatment procedure

Abdominal circumference was measured in all patients

before and after treatment. The treatment protocol is outlined in

Fig. 1. First, the volume of

ascites was assessed via abdominal ultrasonography. Under

ultrasound guidance, a single-lumen central venous catheter or an

external drainage catheter (6F or 8F) was percutaneously inserted

into the abdominal cavity for continuous drainage. Ascites was

drained slowly over 1–3 days with the flow regulated not to exceed

1,000 ml/h to prevent complications. Endostar was administered by

intraperitoneal injection on days 1, 4 and 7 of the treatment

cycle. On day 4, HIPEC was performed immediately following the

Endostar injection. The chemotherapeutic agent (docetaxel or

cisplatin) was prepared in a perfusion solution, which was then

circulated through a closed-loop system equipped with a pump and a

heating module. The solution was heated to the target therapeutic

temperature (42–43°C) and infused into the abdominal cavity; it was

maintained in circulation for the prescribed duration to allow for

continuous hyperthermic perfusion of the peritoneal surface, before

being returned to the system for reheating and recirculation. Core

body temperature was monitored in real-time throughout the HIPEC

procedure using a rectal temperature probe. Ascites drainage

statistics were collected. HIPEC was administered using a

thermochemotherapy perfusion device (RHL-2000A; Jilin Maida Medical

Device Co., Ltd.) with careful temperature control of the body

between 43 and 45°C. Prior to chemotherapeutic drug infusion, the

abdominal cavity was effectively rinsed with 1,000-2,000 ml of warm

normal saline.

All patients received IP injections of Endostar (60

mg) on days 1, 4 and 7 of a 21-day cycle, for a total of two

cycles. The Endostar timing was decided based on the vascular

normalization window principle, as recombinant human endostatin can

temporarily normalize the structure and function of the tumor

vasculature, with this optimal window typically occurring between 3

to 5 days after administration. Therefore, the concurrent IP

administration of Endostar and HIPEC chemotherapeutic agents on day

4 was designed to leverage this transient window to reduce

interstitial pressure and promote the deep and uniform penetration

of chemotherapeutic drugs into the tumor tissues, achieving

spatiotemporal synergism. This regimen aligns with the

recommendations of the Expert Consensus on the Clinical Application

of Recombinant Human Endostatin for the Treatment of Malignant

Serous Cavity Effusions (21) and

has been validated as effective in multiple clinical studies

(22–25). As well as Endostar, 25 patients in

the docetaxel group received 60 mg/m2 docetaxel

intraperitoneally on day 4 as circulating hyperthermic perfusion

chemotherapy, with 21 days per cycle, for a total of two cycles.

Oral administration of 4 mg dexamethasone tablets was started the

day before docetaxel treatment, for a total of 3 days. In the

cisplatin group, 23 patients received 60 mg/m2 cisplatin

on day 4 as IP circulating hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy,

with 21 days per cycle, for a total of two cycles. During the

course of treatment, diuresis and albumin supplementation were

administered as supportive treatments according to specific

conditions, routine blood tests were performed, liver and kidney

functions were monitored, and adverse reactions were observed.

The selection of the treatment approach was not

randomized. Within Zhejiang Hospital, patients with gastric,

ovarian and pancreatic cancer are recommended either cisplatin or

docetaxel treatment, while for patients with colon cancer, only

cisplatin is used. These recommendations are based on clinical

practice guidelines and individual patient characteristics.

Moreover, in line with standard clinical practice to avoid

cisplatin-associated nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, patients

with renal insufficiency (eGFR <60 ml/min) or neuropathy

received docetaxel rather than cisplatin.

Outcomes

The ascites control time was defined as the duration

from achieving a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR)

until the first documented evidence of progressive disease (PD) and

was calculated from the end of the second cycle of treatment. The

abdominal circumference was measured twice a week, and follow-up

examinations were conducted at the hospital 4 weeks after the end

of treatment, followed by collection of abdominal circumference

measurements by telephone. The World Health Organization evaluation

standard (26) classifies ascites

that has completely subsided for >4 weeks as a CR, ascites that

has decreased by >50% and been maintained for >4 weeks as a

PR, ascites that has decreased by <50% or increased by <25%

and been maintained for >4 weeks as SD, and ascites that has

increased by >25% as PD. Objective response rate (ORR)=(CR +

PR)/total number of cases ×100. Disease control rate (DCR)=(CR + PR

+ SD)/total number of cases ×100. If the ascites reached PD,

follow-up was terminated after 90 days. During the follow-up

period, there were no deaths or patients lost to follow-up.

The changes in Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)

score before and after treatment were evaluated according to the

Karnofsky scoring standard (27).

After treatment, a KPS increase of ≥10 points was evaluated as an

improvement in quality of life (QOL), a change of <10 points was

evaluated as stable and a decrease of ≥10 points was evaluated as

decreased QOL (28).

According to the National Cancer Institute Common

Toxic Reaction Standard CTC V4.0, the toxicity grading standard is

divided into grades 1–5, of which grades 1–2 are low-grade

reactions, grades 3–4 are severe reactions and grade 5 indicates

death (29).

Follow-up

The follow-up protocol was defined as follows: Once

PD was reached, the endpoint was determined. Further intensive

follow-up was therefore unnecessary for scientific reasons, and

also to reduce the burden on patients. Follow-up was terminated 90

days after PD, or earlier if the patient died or was lost to

follow-up, while patients without PD were followed until death,

loss to follow-up or study end.

Statistical analysis

Statistical software SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp.)

was used for the data analysis. The ascites control time was

defined as the duration from achieving a CR or PR until the first

documented evidence of PD and was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier

method and differences between groups were compared using the

log-rank test. Normally distributed continuous variables (as

assessed using quantile-quantile plots) are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation and compared using an unpaired t-test, while

non-normally distributed variables are presented as the median

(interquartile range) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum

test. Count data were compared between the groups using the

χ2 test or Fisher's exact probability method. P<0.05

is considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

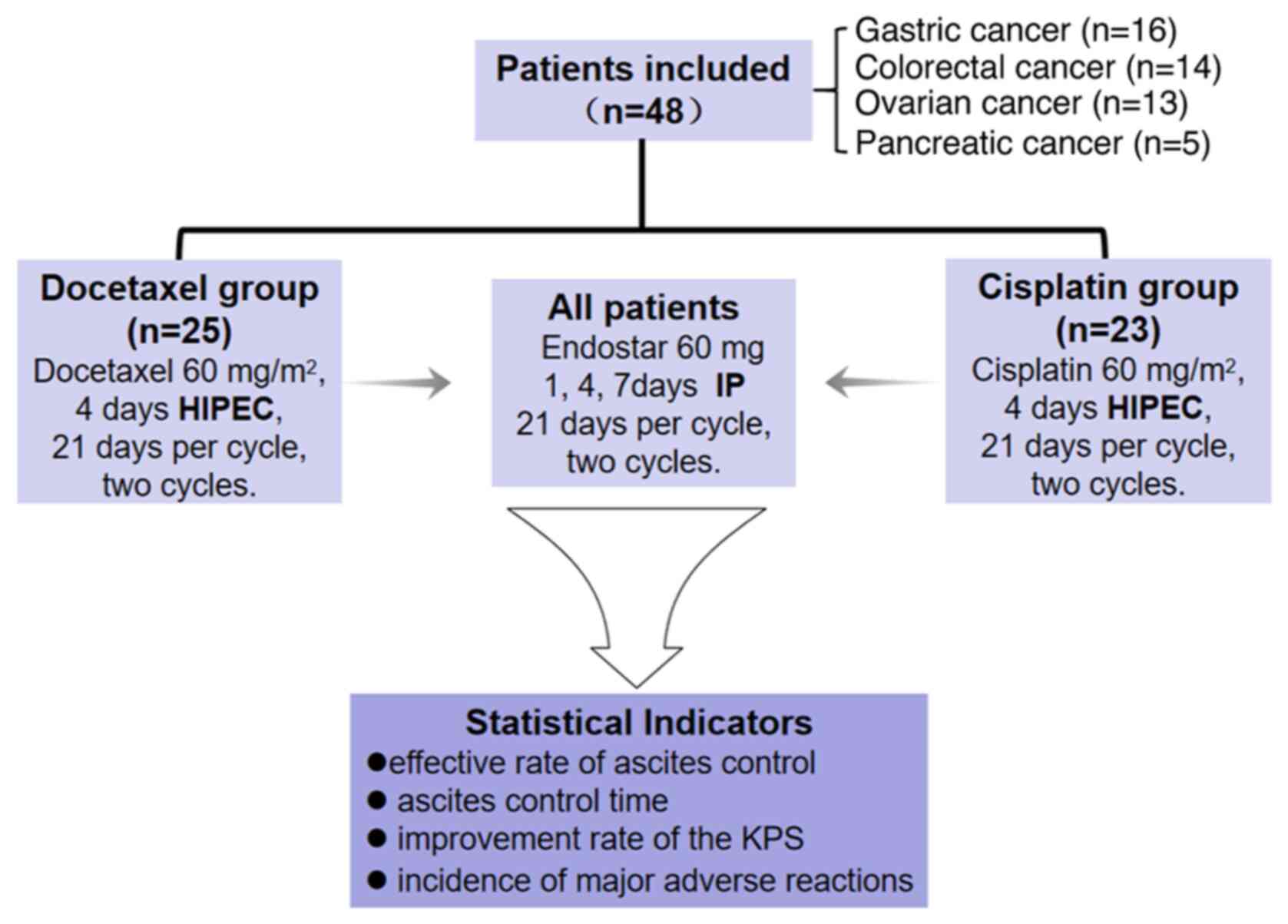

Results

Patient's basic characteristics

As illustrated in Fig.

2, a collective total of 48 patients were included in this

research, with 16 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer, 14

patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer, 13 patients diagnosed

with ovarian cancer and 5 patients diagnosed with pancreatic

cancer. Comparing the cisplatin and docetaxel groups, the age

(55.9±15.4 vs. 55.5±13.8 years; t=0.350; P=0.927), sex [male: 11

(47.8%) vs. 10 (40.0%); χ2=0.298; P=0.585], primary

tumor type (the most common type was gastric cancer: 8 (34.8%) vs.

8 (32.0%); χ2=0.480; P=0.923), KPS score [≥60 points: 14

(60.9%) vs. 16 (64.0%); χ2=0.050; P=0.823], ascites

volume [<3,000 ml: 10 (43.5%) vs. 9 (36.0%);

χ2=0.280; P=0.597] and previous treatment option

[second-line: 9 (39.1%) vs. 8 (32.0%); χ2=0.266;

P=0.606] of the two groups were evenly distributed and the results

were comparable (Table I).

| Table I.Comparison of general conditions

between the docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups. |

Table I.

Comparison of general conditions

between the docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups.

| Variables | Docetaxel

group | Cisplatin

group |

χ2/t | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

| 0.298 | 0.585 |

|

Male | 10 (40.0) | 11 (47.8) |

|

|

|

Female | 15 (60.0) | 12 (52.2) |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.350 | 0.927 |

| Average

age | 55.5±13.8 | 55.9±15.4 |

|

|

| Age

distribution | 28-78 | 30-78 |

|

|

| KPS, n (%) |

|

| 0.050 | 0.823 |

|

≥60 | 16 (64.0) | 14 (60.9) |

|

|

|

<60 | 9 (36.0) | 9 (39.1) |

|

|

| Ascites volume, n

(%) |

|

| 0.280 | 0.597 |

|

<3,000 ml | 9 (36.0) | 10 (43.5) |

|

|

| ≥3,000

ml | 16 (64.0) | 13 (56.5) |

|

|

| Prior treatment, n

(%) |

|

| 0.266 | 0.606 |

|

Second-line | 8 (32.0) | 9 (39.1) |

|

|

|

>Second-line | 17 (68.0) | 14 (60.9) |

|

|

| Primary tumor, n

(%) |

|

| 0.480 | 0.923 |

| Gastric

cancer | 8 (32.0) | 8 (34.8) |

|

|

|

Colorectal cancer | 8 (32.0) | 6 (26.1) |

|

|

| Ovarian

cancer | 6 (24.0) | 7 (30.4) |

|

|

|

Pancreatic cancer | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.7) |

|

|

Objective efficacy evaluation

In Table II, among

the participants in the docetaxel group, 3 patients achieved a CR,

13 achieved a PR, 7 were stable and 2 exhibited PD, with an ORR of

64.0% and a DCR of 92.0%. In the cisplatin group, 2 patients

achieved a CR, 11 achieved a PR, 8 were stable and 2 exhibited PD,

with an ORR of 56.5% and a DCR of 91.3%. There were no

statistically significant differences between the two groups in

terms of either ORR (χ2=0.280, P=0.597) or DCR

(P>0.999, Fisher's exact test).

| Table II.Comparison of curative effects

between the docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups. |

Table II.

Comparison of curative effects

between the docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups.

| Response | Docetaxel

group | Cisplatin

group | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| CR, n (%) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.7) |

|

|

| PR, n (%) | 13 (52.0) | 11 (47.8) |

|

|

| SD, n (%) | 7 (28.0) | 8 (34.8) |

|

|

| PD, n (%) | 2 (8.0) | 2 (8.7) |

|

|

| ORR, n (%) | 16 (64.0) | 13 (56.5) | 0.280 | 0.597 |

| DCR, n (%) | 23 (92.0) | 21 (91.3) | - |

>0.999a |

QOL of patients

KPS scores were utilized to gauge the QOL. As shown

in Table III, KPS improvement

rates were 48.0 and 43.5% for the docetaxel and cisplatin groups,

respectively. There was no significant difference in the QOL

between the two groups (χ2=0.967;

P=0.617).

| Table III.Improvement of quality of life

between the docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups. |

Table III.

Improvement of quality of life

between the docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups.

| Status | Docetaxel

group | Cisplatin

group | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Improvement, n

(%) | 12 (48.0) | 10 (43.5) |

|

|

| Stabilization, n

(%) | 11 (44.0) | 9 (39.1) |

|

|

| Declined, n

(%) | 2 (8.0) | 4 (17.4) | 0.967 | 0.617 |

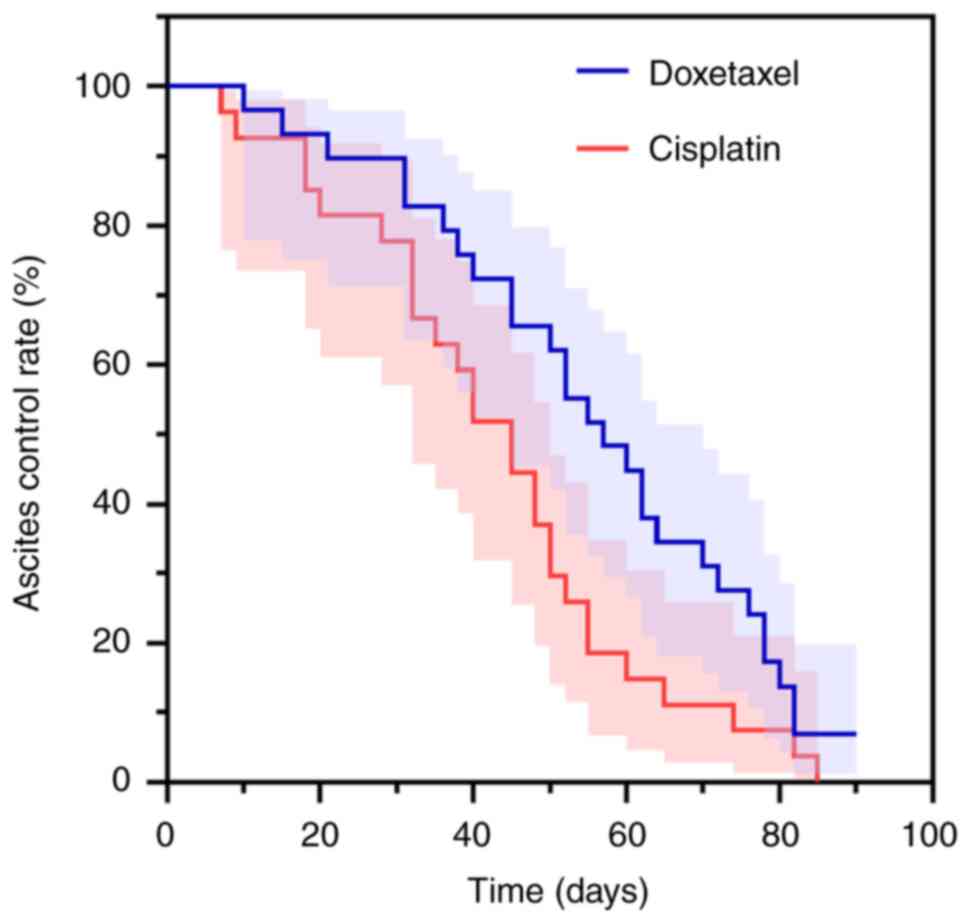

The median ascites control time was 55 days (95% CI:

46.892–63.108) in the docetaxel group and 46 days (95% CI:

34.261–57.739) in the cisplatin group. When comparing the control

time between the two groups, the difference was not statistically

significant (log-rank χ2=0.934; P=0.334)

(Fig. 3).

Security analysis

There were no significant differences between the

two groups in terms of the incidence of leukopenia

(χ2=0.680; P=0.712), anemia

(χ2=0.473; P=0.789), thrombocytopenia

(χ2=0.762; P=0.683), nausea and vomiting

(χ2=1.451; P=0.484), anorexia

(χ2=0.309; P=0.857), fatigue

(χ2=0.071; P=0.965), constipation

(χ2=0.371; P=0.573), abdominal pain and diarrhea

(χ2=0.285; P=0.867), hepatic damage

(χ2=0.084; P=0.772), or palpitation/chest

tightness (χ2=0.084; P=0.772). However, the

incidence of kidney damage was significantly higher in the

cisplatin group than in the docetaxel group

(χ2=6.194; P=0.045). Additionally, there was a

significant difference between the two groups with regard to the

elevation of blood pressure (χ2=5.135; P=0.023)

(Table IV).

| Table IV.Adverse reactions between the

docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups. |

Table IV.

Adverse reactions between the

docetaxel (n=25) and cisplatin (n=23) groups.

| Variables | Docetaxel

group | Cisplatin

group | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Leukopenia, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 6 (24.0) | 4 (17.4) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.3) | 0.680 | 0.712 |

| Anemia, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 5 (20.0) | 4 (17.4) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.473 | 0.789 |

| Thrombopenia, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 4 (16.0) | 6 (26.1) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.762 | 0.683 |

| Nausea and

vomiting, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 4 (16.0) | 5 (21.7) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1.451 | 0.484 |

| Anorexia, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 8 (32.0) | 9 (39.1) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 2 (8.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.309 | 0.857 |

| Fatigue, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 14 (56.0) | 12 (52.2) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.3) | 0.071 | 0.965 |

| Constipation, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 6 (24.0) | 4 (17.4) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.371 | 0.573 |

| Abdominal pain and

diarrhea, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 4 (16.0) | 5 (21.7) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 2 (8.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.285 | 0.867 |

| Hepatic damage, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 4 (16.0) | 3 (13.0) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.084 | 0.772 |

| Kidney damage, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 1 (4.0) | 5 (21.7) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 6.194 | 0.045 |

| Palpitation/chest

tightness, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 4 (16.0) | 3 (13.0) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.084 | 0.772 |

| Elevation of blood

pressure, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 5 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

|

III–IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5.135 | 0.023 |

Discussion

Advanced tumor PM can result in the development of

MA, which significantly impairs patient survival and QOL (30). The development of MA is a

multifaceted and intricate physiological process that is

intricately linked to the impediment of lymphatic drainage, tumor

angiogenesis and alterations in microvascular permeability

(31). VEGF stimulates tumor cells

and mesothelial cells, causing vascular growth factors such as

TNF-α, TGF-β, VEGF and IL-8 to increase in malignant effusions

(32). The VEGF level of MA is

significantly higher than that of benign ascites and VEGF levels

are correlated with a worse prognosis (33). The ‘peritoneal-plasma barrier’

restricts macromolecular drug absorption via the peritoneum, which

enables a high drug concentration in the abdominal cavity while

maintaining low peripheral blood drug levels (34). HIPEC, a recent therapeutic strategy,

promotes deep tissue penetration of chemotherapeutic drugs,

enhancing their concentration in tumor cells, and achieving a

positive therapeutic effect.

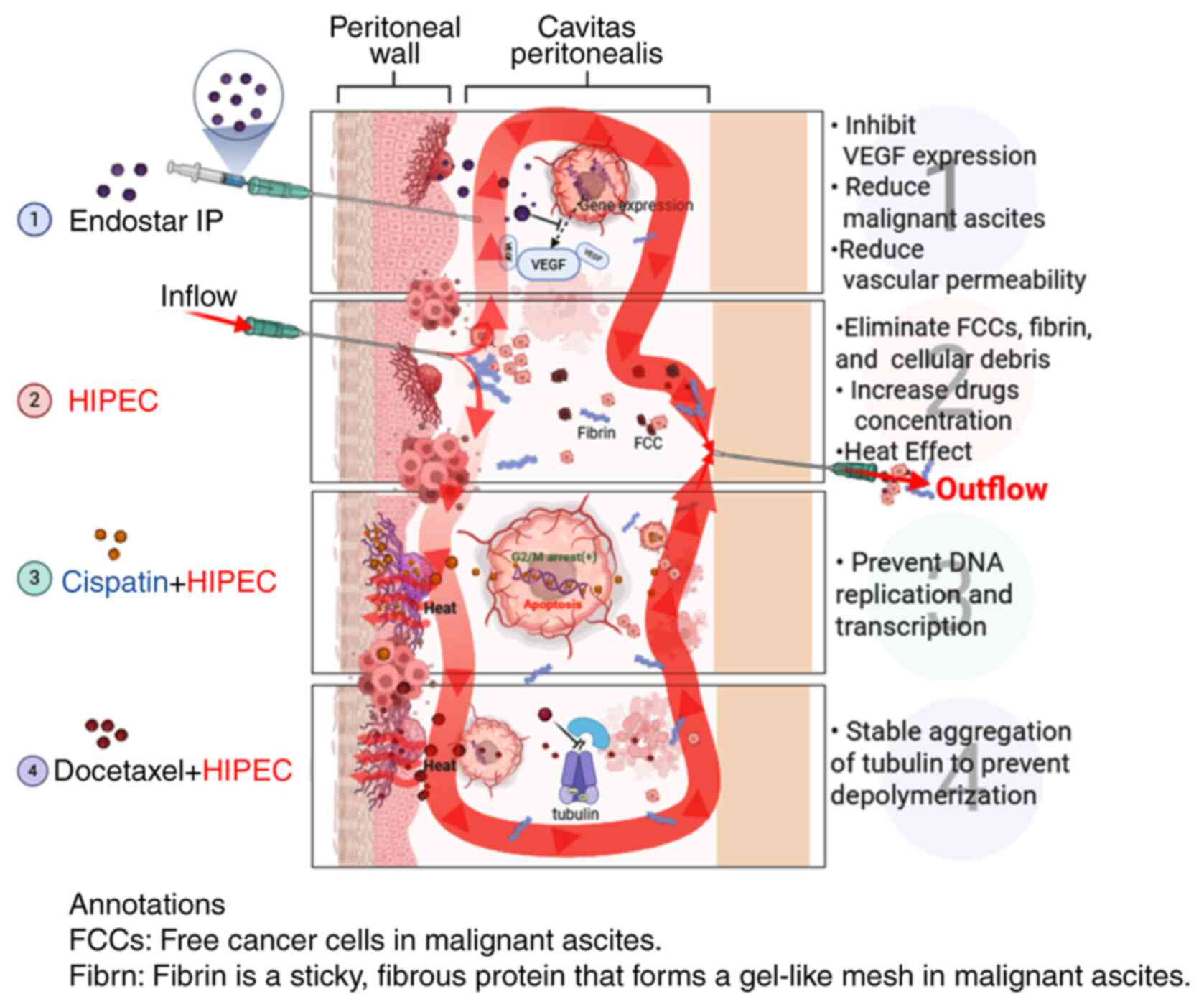

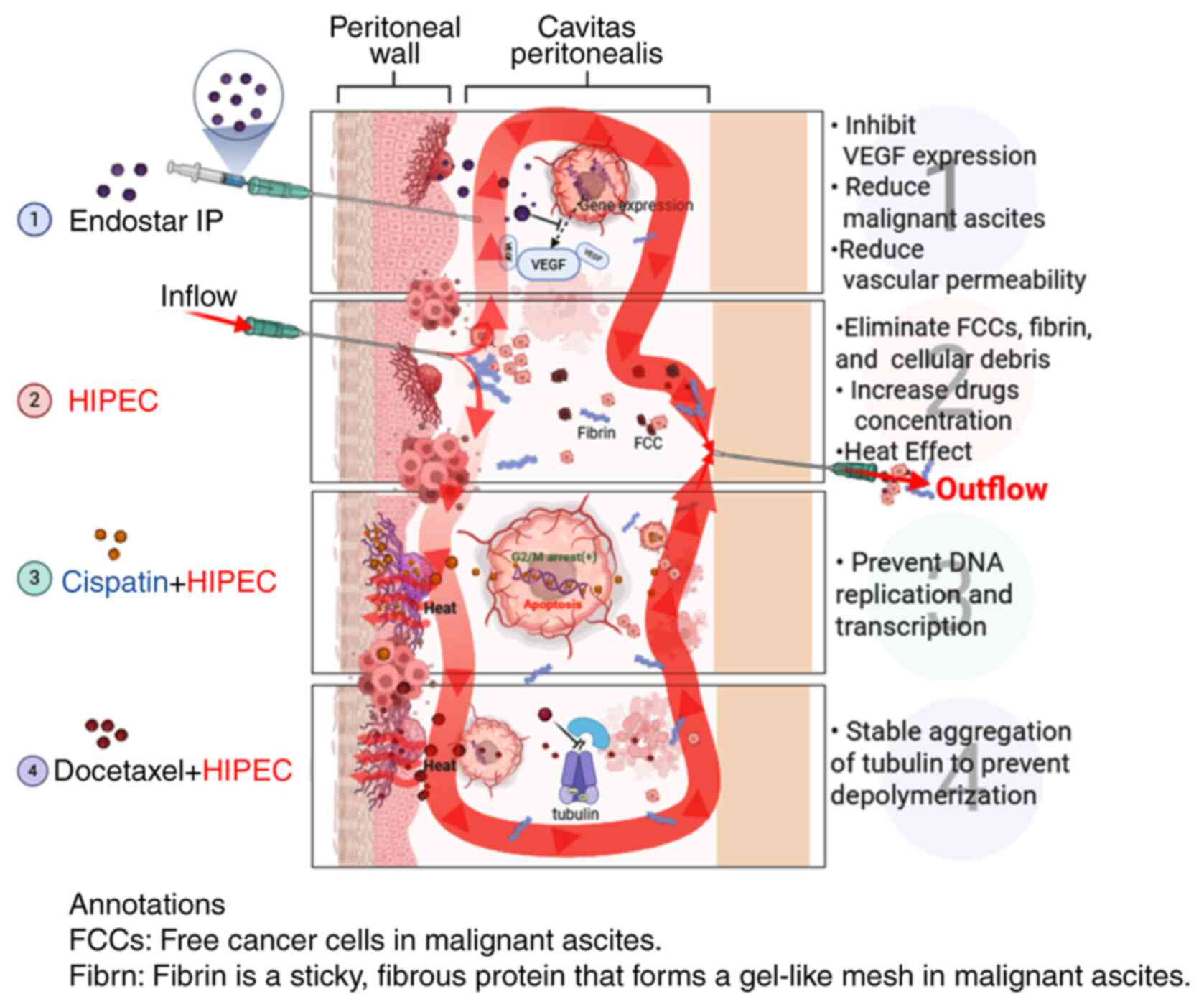

As shown in Fig. 4,

the general mechanism of Endostar combined with docetaxel/cisplatin

HIPEC in the treatment of MA may be as follows: i) Endostar

inhibits vascular endothelium proliferation, differentiation and

migration, reducing blood vessel filtration area and permeability,

reducing material exudation and controlling MA osmotic pressure,

thereby reducing effusion (7,35,36).

ii) HIPEC treatment kills MA tumor cells by repeated washing,

causing anoikis and tumor cell detachment. Heat changes the tumor

cell membrane and vascular permeability, reducing drug metabolism

and increasing drug concentration (37,38).

Heat shock protein activation by heat can induce an autoimmune

attack on tumor cells, block angiogenesis and cause protein

denaturation (39). iii) Cisplatin

can directly enter the tumor cell nucleus to prevent DNA

replication and transcription to achieve the purpose of killing

tumor cells (40). iv) Docetaxel

binds to tubulin subunits after entering the body, stably

accumulates tubulin, prevents depolymerization and inhibits tumor

cell proliferation (41).

| Figure 4.Mechanisms of docetaxel/cisplatin

HIPEC combined with IP Endostar in the treatment of MA. As shown in

point 1, the IP Endostar injection inhibits VEGF expression,

reduces MA and reduces vascular permeability. A shown in point 2,

when HIPEC is performed, drug concentration and temperature

increase. As shown in points 3 and 4, the addition of cisplatin can

prevent DNA replication and transcription, while the addition of

docetaxel can stabilize the aggregation of tubulin and prevent

depolymerization. MA, malignant ascites; IP, intraperitoneal;

HIPEC, hyperthermic IP chemotherapy; FCC, free cancer cell. Created

in BioRender, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/64297f7a20eede8ed30124a8?slideId=3d6d849d-02c8-4b18-b5ee-18396b8d452e. |

Cisplatin and Endostar are both commonly used drugs

for HIPEC and have various indications for use. Cisplatin is

conventionally indicated for peritoneal malignancies, particularly

ovarian cancer (42), whereas

Endostar is commonly employed in the management of malignant

ascites (43). Zhao et al

(35) reported that the disease

control rate was 87.0% for pleural effusion and ascites using

Endostar combined with cisplatin, while Fu et al (44) showed that patients who received

HIPEC with cisplatin plus docetaxel had a longer median overall

survival time compared with those who received cisplatin plus

mitomycin. A previous study revealed that detectable cisplatin

concentrations persisted for at least 6 h post-HIPEC (45), while Endostar was proven effective

for reducing the expression of VEGF and other factors, including

fibroblast growth factor-2, transforming growth factor-β1, and

platelet-derived growth factor-B (46). However, the major side effects of

cisplatin include acute and chronic nephrotoxicity, both systemic

and IP. Hakeam et al (47)

reported that 3.7% of patients experienced acute kidney injury

after HIPEC with cisplatin, while Gómez-Ruiz et al (48) showed that 7.2% of patients developed

acute renal dysfunction after HIPEC. Cisplatin can induce early

proximal tubular injury, leading to acute or subacute tubular

necrosis. In addition, cisplatin can cause a gradual and

irreversible decline in the long-term filtration capacity of the

glomerulus, leading to chronic renal failure. This toxicity is the

main reason for limiting the IP injection of cisplatin (37). Previous studies showed that the

incidence of acute renal failure after HIPEC combined with

cisplatin was from 1.3 to 40.4%, and 8.5% developed into grade 3–4

kidney injury; moreover, these acute or chronic renal failures

contributed to 4.3% of long-term dialysis patients (49,50),

which seriously affected subsequent consolidation therapy with

other anticancer drugs or further treatment after recurrence. In

the present study, the incidence of renal impairment in the

cisplatin group was 30.4%, which is similar to that reported in the

aforementioned previous studies. Docetaxel is a semi-synthetic

taxoid drug that is widely used to treat non-small cell lung,

breast, gastric and ovarian cancer (51). Studies have shown that the area

under the curve (AUC) of peritoneal injection is nearly 1,000 times

higher than that of intravenous injection, and the peak

concentration in the peritoneum is ~200 times higher than that in

the plasma, making docetaxel a suitable drug for HIPEC application

(52,53). The present study retrospectively

evaluated the efficacy and safety of docetaxel/cisplatin combined

with Endostar for the treatment of MA. The objective remission rate

(64.0 vs. 56.5%), DCR (92.0 vs. 91.3%), improvement in the KPS

score (48 vs. 43.5%) and median control time of ascites (55 days

vs. 46 days) in the two groups were similar. However, in terms of

the occurrence of adverse reactions, the cisplatin group had higher

renal toxicity; 5 patients had grade 1–2 renal damage, and after

symptomatic treatments such as diuresis and kidney protection (such

as reduced glutathione Bailing capsule use), the renal function

recovered to normal. Overall, 2 patients had grade 3–4 renal

damage, and 1 patient developed chronic renal failure and received

hemodialysis maintenance treatment. The incidence of renal

impairment was much lower in the docetaxel group than in the

cisplatin group, and the underlying reason could be associated with

the different metabolism of the two drugs. Miller et al

(54) reported that cisplatin is

primarily excreted through the kidneys and may lead to the damage

and necrosis of renal tubular epithelial cells (54). Meanwhile, docetaxel is primarily

metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system and

has low direct toxicity to the kidneys (55). A more direct comparison was shown in

the study performed by Kurokawa et al (56), where increased creatinine levels

were only observed in patients receiving cisplatin plus S-1, while

patients with docetaxel plus S-1 exhibited normal creatinine levels

(56).

Other adverse effects were similar between the two

groups in the present study, and there was no significant

difference in efficacy. In comparison to cisplatin, the treatment

of MA with docetaxel combined with HIPEC can improve patients' QOL,

induce minimal adverse effects on renal function and display fewer

adverse reactions. Notably, psychological and social factors are

also important for patients' QOL, while the KPS score used in the

present study focuses more on physical function. In future studies,

the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (57), Symptom Checklist 90 (58) and other tools should also be

evaluated.

The present study had several limitations. Firstly,

the sample size was relatively small, with only 48 participants

included in the final analysis. This limited number resulted in

insufficient statistical power, which may have reduced the ability

to detect true differences in ORR, improvement of KPS scores and

ascites control time between the two groups. Furthermore, although

an attempt was made to perform multivariable analyses to adjust for

potential confounding factors, these models failed to converge due

to data sparsity issues, which was a direct consequence of the

small sample size, therefore yielding no reliable results.

Consequently, these findings require rigorous examination in future

large-scale cohorts. Secondly, key potential confounders such as

the peritoneal cancer index, baseline renal function and specific

details of personalized treatment plans were not available for

inclusion in the analysis. Thirdly, the retrospective nature of the

study means that treatment methods were non-randomly determined

based on established guidelines, patients' medical history and

current clinical status; therefore, the results remain susceptible

to indication bias, emphasizing the necessity for future randomized

controlled trials to further validate the findings. Finally, the

study relied solely on the KPS score for QOL evaluation. Future

studies should employ more comprehensive, multidimensional QOL

assessment tools to better capture the full spectrum of patients'

psychological and social wellbeing.

In conclusion, the present retrospective study

revealed that HIPEC with docetaxel and Endostar exhibited

comparable efficacy to a cisplatin-based regimen for controlling

MA, but with a significantly more favorable safety profile,

particularly with a lower incidence of nephrotoxicity. This

indicates that docetaxel may be a preferable agent for MA; however,

the finding warrants investigation in future prospective

trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Zhibing Wu

(Department of Oncology, Affiliated Zhejiang Hospital, Hangzhou,

China) for their suggestions on study design.

Funding

This study was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science

Nation of China (grant no. LQN25H290003), the Medical Science and

Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2023RC124), the

Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of

Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2023ZR061), the Medical Science and

Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2024KY594) and

the Zhejiang Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine for

Chinese Medicine Expert's Wan Xiaoging Inheritance Studio Project

(grant no. GZS2021028).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JW was responsible for conceptualization, data

curation (lead), formal analysis (preliminary) and writing the

original draft (lead). JQ and YZ performed data curation

(collecting and organising clinical data) (supporting) and

validation, and helped to review and edit the manuscript

(supporting). DY performed the formal analysis (lead, conducted

final statistical analysis) and was in involved with the

methodology (statistical). GZ contributed to the study

conceptualization and design, and the analysis and interpretation

of data, provided critical revision of the manuscript for important

intellectual content and approved the final version to be

published. Additionally, GZ led the project administration and

supervision, and secured funding; they are responsible for the

communication and integrity of the work. YW was responsible for

conceptualization, interpretation (clinical data) and reviewing and

editing the manuscript (supporting). JW, YW and GZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was performed in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association.

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant

guidelines. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee

of Zhejiang Hospital (Hangzhou, China; approval no. 2021-41K).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants for the HIPEC

treatment, and informed consent to participate in the study was

waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Soliman F, Ye L, Jiang W and Hargest R:

O17: Hyaluronic acid dependent adhesion in colorectal cancer

peritoneal metastasis. Br J Surg. 108 (Suppl 1):znab117.017. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhu L, Xu Z, Wu Y, Liu P, Qian J, Yu S,

Xia B, Lai J, Ma S and Wu Z: Prophylactic chemotherapeutic

hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion reduces peritoneal

metastasis in gastric cancer: A retrospective clinical study. BMC

Cancer. 20:8272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhu L, Xu Y, Shan Y, Zheng R, Wu Z and Ma

S: Intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy and whole abdominal

hyperthermia using external radiofrequency following radical D2

resection for treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Int J

Hyperthermia. 36:403–407. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mei S, Chen X, Wang K and Chen Y: Tumor

microenvironment in ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Cancer

Cell Int. 23:112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Avula LR, Hagerty B and Alewine C:

Molecular mediators of peritoneal metastasis in pancreatic cancer.

Cancer Metastasis Rev. 39:1223–1243. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Roth L, Russo L, Ulugoel S, Freire Dos

Santos R, Breuer E, Gupta A and Lehmann K: Peritoneal metastasis:

Current status and treatment options. Cancers (Basel). 14:602021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hu L, Hofmann J, Holash J, Yancopoulos GD,

Sood AK and Jaffe RB: Vascular endothelial growth factor trap

combined with paclitaxel strikingly inhibits tumor and ascites,

prolonging survival in a human ovarian cancer model. Clin Cancer

Res. 11:6966–6971. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y, Wu Y, Wu J and Wu C: Direct and

indirect anticancer effects of hyperthermic intraperitoneal

chemotherapy on peritoneal malignancies (Review). Oncol Rep.

45:232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Karimi M, Shirsalimi N and Sedighi E:

Challenges following CRS and HIPEC surgery in cancer patients with

peritoneal metastasis: A comprehensive review of clinical outcomes.

Front Surg. 11:14985292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jung H: Interaction of thermotolerance and

thermosensitization induced in CHO cells by combined hyperthermic

treatments at 40 and 43 degrees C. Radiat Res. 91:433–446. 1982.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Spratt JS, Adcock RA, Muskovin M, Sherrill

W and McKeown J: Clinical delivery system for intraperitoneal

hyperthermic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 40:256–260. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cortes-Guiral D and Glehen O: Expanding

uses of hipec for locally advanced colorectal cancer: A European

perspective. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 33:253–257. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Braam HJ, Schellens JH, Boot H, van

Sandick JW, Knibbe CA, Boerma D and van Ramshorst B: Selection of

chemotherapy for hyperthermic intraperitoneal use in gastric

cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 95:282–296. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

de Bree E and Michelakis D: An overview

and update of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian

cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 21:1479–1492. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ding Y, Wang Y, Cui J and Si T: Endostar

blocks the metastasis, invasion and angiogenesis of ovarian cancer

cells. Neoplasma. 67:595–603. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shaheen RM, Davis DW, Liu W, Zebrowski BK,

Wilson MR, Bucana CD, McConkey DJ, McMahon G and Ellis LM:

Antiangiogenic therapy targeting the tyrosine kinase receptor for

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibits the growth of

colon cancer liver metastasis and induces tumor and endothelial

cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 59:5412–5416. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hu Y, Zhou Z and Luo M: Efficacy and

safety of endostar combined with cisplatin in treatment of

non-small cell lung cancer with malignant pleural effusion: A

meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 101:e322072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Biaoxue R, Xiguang C, Hua L, Wenlong G and

Shuanying Y: Thoracic perfusion of recombinant human endostatin

(Endostar) combined with chemotherapeutic agents versus

chemotherapeutic agents alone for treating malignant pleural

effusions: A systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer.

16:8882016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Guchelaar NAD, Noordman BJ, Koolen SLW,

Mostert B, Madsen EVE, Burger JWA, Brandt-Kerkhof ARM, Creemers GJ,

de Hingh IHJT, Luyer M, et al: Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for

unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies. Drugs. 83:159–180.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chia DKA, Demuytere J, Ernst S, Salavati H

and Ceelen W: Effects of hyperthermia and hyperthermic

intraperitoneal chemoperfusion on the peritoneal and tumor immune

contexture. Cancers (Basel). 15:43142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology

Antitumor Drug Safety Management Expert Committee and Chinese

Society of Clinical Oncology Vascular Targeted Therapy Expert

Committee, . Expert consensus on the clinical application of

recombinant human endostatin for the treatment of malignant serous

effusions. Chinese Clinical Oncology. 25:849–856. 2020.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ning T, Jiang M, Peng Q, Yan X, Lu ZJ,

Peng YL, Wang HL, Lei N, Zhang H, Lin HJ, et al: Low-dose

endostatin normalizes the structure and function of tumor

vasculature and improves the delivery and anti-tumor efficacy of

cytotoxic drugs in a lung cancer xenograft murine model. Thorac

Cancer. 3:229–238. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lv Y, Jiang R, Ma C, Li J, Wang B, Sun L

and Mu N: Clinical observation of recombinant human vascular

endostatin durative transfusion combined with window period

arterial infusion chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced lung

squamous carcinoma. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 18:500–504. 2015.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lin MI and Sessa WC: Antiangiogenic

therapy: Creating a unique ‘window’ of opportunity. Cancer Cell.

6:529–531. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang XD, Dai P, Qiao Y, Wu J, Song DA and

Li SQ: Clinical study on the recombinant human endostatin regarding

improving the blood perfusion and hypoxia of non-small-cell lung

cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 14:437–443. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M and

Winkler A: Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer.

47:207–214. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Karnofsky DA and Burchenal JH: The

clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. MacLeod

CM: Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University

Press; New York: pp. 191–205. 1949

|

|

28

|

Schag CC, Heinrich RL and Ganz PA:

Karnofsky performance status revisited: Reliability, validity, and

guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2:187–193. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

US Department of Health and Human

Services, National Institutes of Health and National Cancer

Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

Version 4.0. 2009.

|

|

30

|

Deraco M, Kusamura S, Virzì S, Puccio F,

Macrì A, Famulari C, Solazzo M, Bonomi S, Iusco DR and Baratti D:

Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy

as upfront therapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer:

Multi-institutional phase-II trial. Gynecol Oncol. 122:215–220.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Matsusaki K, Aridome K, Emoto S, Kajiyama

H, Takagaki N, Takahashi T, Tsubamoto H, Nagao S, Watanabe A,

Shimada H and Kitayama J: Clinical practice guideline for the

treatment of malignant ascites: Section summary in clinical

practice guideline for peritoneal dissemination (2021). Int J Clin

Oncol. 27:1–6. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Horikawa N, Abiko K, Matsumura N,

Hamanishi J, Baba T, Yamaguchi K, Yoshioka Y, Koshiyama M and

Konishi I: Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in

ovarian cancer inhibits tumor immunity through the accumulation of

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 23:587–599.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhan N, Dong WG and Wang J: The clinical

significance of vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant

ascites. Tumour Biol. 37:3719–3725. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chiva LM and Gonzalez-Martin A: A critical

appraisal of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in

the treatment of advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol

Oncol. 136:130–135. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhao WY, Chen DY, Chen JH and Ji ZN:

Effects of intracavitary administration of Endostar combined with

cisplatin in malignant pleural effusion and ascites. Cell Biochem

Biophys. 70:623–628. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wei H, Qin S, Yin X, Chen Y, Hua H, Wang

L, Yang N, Chen Y and Liu X: Endostar inhibits ascites formation

and prolongs survival in mouse models of malignant ascites. Oncol

Lett. 9:2694–2700. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Laplace N, Kepenekian V, Friggeri A,

Vassal O, Ranchon F, Rioufol C, Gertych W, Villeneuve L, Glehen O

and Bakrin N: Sodium thiosulfate protects from renal impairement

following hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) with

cisplatin. Int J Hyperthermia. 37:897–902. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Goodman MD, McPartland S, Detelich D and

Saif MW: Chemotherapy for intraperitoneal use: A review of

hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy and early post-operative

intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 7:45–57.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu P, Wu Y, Xu X, Fan X, Sun C, Chen X,

Xia J, Bai S, Qu L, Lu H, et al: Microwave triggered

multifunctional nanoplatform for targeted photothermal-chemotherapy

in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nano Res. 16:9688–9700.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Li Y, Köpper F and Dobbelstein M:

Inhibition of MAPKAPK2/ MK2 facilitates DNA replication upon cancer

cell treatment with gemcitabine but not cisplatin. Cancer Lett.

428:45–54. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Pu YS, Huang CY, Wu HL, Wu JH, Su YF, Yu

CTR, Lu CY, Wu WJ, Huang SP, Huang YT and Hour TC: EGFR-mediated

hyperacetylation of tubulin induced docetaxel resistance by

downregulation of HDAC6 and upregulation of MCAK and PLK1 in

prostate cancer cells. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 40:23–34. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K,

Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Schreuder HWR, Hermans RHM, de Hingh IHJT,

van der Velden J, Arts HJ, Massuger LFAG, et al: Hyperthermic

intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med.

378:230–240. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhan ZW, Wang XJ, Yu JM, Zheng JX, Zeng Y,

Sun MY, Peng L, Guo ZQ and Chen BJ: Intraperitoneal Infusion of

Recombinant Human Endostatin Improves Prognosis in Gastric Cancer

Ascites. Future Oncol. 18:1259–1271. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Fu YB, Yang R, Su YD, Ma R, Wei T, Yu Y,

Li B and Li Y: Cisplatin + docetaxel improves survival over

cisplatin + mitomycin C in hyperthermic intraperitoneal

chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei: A retrospective study

based on propensity score matching. Int J Hyperthermia.

42:24672962025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Harlev C, Bue M, Petersen EK, Jørgensen

AR, Bibby BM, Hanberg P, Schmedes AV, Petersen LK and Stilling M:

Dynamic assessment of local abdominal tissue concentrations of

cisplatin during a HIPEC procedure: Insights from a porcine model.

Ann Surg Oncol. 32:3804–3813. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang Y and Ren H: Multi-omics sequencing

revealed endostar combined with cisplatin treated non small cell

lung cancer via anti-angiogenesis. BMC Cancer. 24:1872024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hakeam HA, Breakiet M, Azzam A, Nadeem A

and Amin T: The incidence of cisplatin nephrotoxicity post

hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) and cytoreductive

surgery. Ren Fail. 36:1486–1491. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Gómez-Ruiz ÁJ, González-Gil A, Gil J,

Alconchel F, Navarro-Barrios Á, Gil-Gómez E, Martínez J, Nieto A,

García-Palenciano C and Cascales-Campos PA: Acute renal disease in

patients with ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with

cytoreduction and HIPEC: The influence of surgery and the

cytostatic agent used. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 406:2449–2456. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ye J, Ren Y, Wei Z, Peng J, Chen C, Song

W, Tan M, He Y and Yuan Y: Nephrotoxicity and long-term survival

investigations for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis using

hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with cisplatin: A

retrospective cohort study. Surg Oncol. 27:456–461. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Sin EI, Chia CS, Tan GHC, Soo KC and Teo

MC: Acute kidney injury in ovarian cancer patients undergoing

cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intra-peritoneal

chemotherapy. Int J Hyperthermia. 33:690–695. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Koemans WJ, van der Kaaij RT, Wassenaar

ECE, Grootscholten C, Boot H, Boerma D, Los M, Imhof O, Schellens

JHM, Rosing H, et al: Systemic exposure of oxaliplatin and

docetaxel in gastric cancer patients with peritonitis

carcinomatosis treated with intraperitoneal hyperthermic

chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 47:486–489. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Morgan RJ Jr, Doroshow JH, Synold T, Lim

D, Shibata S, Margolin K, Schwarz R, Leong L, Somlo G, Twardowski

P, et al: Phase I trial of intraperitoneal docetaxel in the

treatment of advanced malignancies primarily confined to the

peritoneal cavity: Dose-limiting toxicity and pharmacokinetics.

Clin Cancer Res. 9:5896–5901. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Marchettini P, Stuart OA, Mohamed F, Yoo D

and Sugarbaker PH: Docetaxel: Pharmacokinetics and tissue levels

after intraperitoneal and intravenous administration in a rat

model. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 49:499–503. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G and

Reeves WB: Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel).

2:2490–2518. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Clarke SJ and Rivory LP: Clinical

pharmacokinetics of docetaxel. Clin Pharmacokinet. 36:99–114. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kurokawa Y, Matsuyama J, Nishikawa K,

Takeno A, Kimura Y, Fujitani K, Kawabata R, Makari Y, Terazawa T,

Kawakami H, et al: Docetaxel plus S-1 versus cisplatin plus S-1 in

unresectable gastric cancer without measurable lesions: A

randomized phase II trial (HERBIS-3). Gastric Cancer. 24:428–434.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Alyami MM and Alasmari AA: Exploratory and

confirmatory factor analysis of the arabic medical outcomes

study-social support Survey-6 among Saudi adults. Saudi J Med Med

Sci. 13:197–204. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Derogatis LR, Rickels K and Rock AF: The

SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report

scale. Br J Psychiatry. 128:280–289. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|