Introduction

In vitro pharmacological and pathological

models serve as indispensable tools in antitumor drug discovery and

development. In vitro tumor cell culture not only enables

the investigation of specific tumor cell behaviors such as growth

state, metastasis, differentiation, signal transduction, gene

expression and other key processes (1) but also offers the advantages of high

efficiency and cost-effectiveness. In comparison, tumor animal

models have limitations that restrict their application, including

high costs, lengthy experimental duration, low controllability,

high vulnerability to internal and external environmental

variables, species-specific differences that compromise accurate

prediction of human drug responses and the inability to construct

all human tumor models (2).

Collectively, these attributes establish the in vitro method

as a foundational platform for antitumor drug development and

screening (3). Cell culture models

can generally be categorized into two main categories:

Two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) cell models. As

research on cell culture models progresses, several limitations of

2D cell models have been revealed, including low cell viability,

susceptibility to cell morphology damage and the absence of actual

tissue structure (4). This

structural deficiency restricts cell-cell and cell-extracellular

matrix (ECM) interactions, thus failing to mimic the in vivo

tumor microenvironment. Therefore, 2D models prove inadequate for

accurately replicating the actual growth characteristics of tumors

in vivo (5). By supporting

cell proliferation and interactions within a 3D space, 3D cell

models facilitate the 3D structural formation of cell populations

(6). This system better simulates

and replicates in vivo cell biology, resulting in enhanced

culture efficiency, increased yields of cytokines, antibodies and

other biomolecules, and improved overall cell proliferation

(7). Current 3D models for studying

tumor cells can be classified into two principal categories based

on scaffold utilization: Scaffold and scaffold-free models. To

systematically evaluate these culture modalities, Table I provides a comprehensive framework

that delineates their respective technical boundaries and

translational potential, thereby guiding researchers in selecting

the most appropriate model for specific research objectives. Among

these, scaffold-based models have emerged as a central platform in

cutting-edge translational applications such as 3D bioprinting and

organ-on-a-chip technologies, due to the marked diversity and

tunability of their biomaterial components (8–10).

Therefore, the present review first outlines fundamental research

progress on scaffold-based models, followed by an examination of

the core mechanisms underlying scaffold-free systems. Building upon

this foundation, the present review integrates and discusses the

potential of various in vitro 3D models for drug-screening

and clinical applications. Lastly, the present review offers a

forward-looking perspective on bridging the gap between model

systems and clinical practice in the future.

| Table I.Scaffold-based vs. scaffold-free

culture methods. |

Table I.

Scaffold-based vs. scaffold-free

culture methods.

| A, Scaffold

model |

|---|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Subtype | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

Applications/examples | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Alafnan, 2022 | Solid porous

scaffolds | Polymers (for

example, PEGDA) with porous structures for cell support and drug

delivery | Simple fabrication,

high permeability and uniform density | Limited dynamic

microenvironment simulation | Gemcitabine-loaded

microneedles for inflammatory breast cancer | (14) |

| Fu, 2024 | Hydrogel

scaffolds | Natural/artificial

hydrogels (for example, fibrin and agarose) mimicking ECM

properties | High

biocompatibility, nutrient diffusion and structural

flexibility | Variable nutrient

transport depending on material composition | Breast tumor drug

resistance studies | (23) |

| Kim, 2019 | Non-hydrogel

scaffolds | Natural materials

(collagen and chitosan) for controlled drug release | Biodegradable and

supports sustained/controlled drug delivery | Lower mechanical

strength compared with synthetic scaffolds | Glioblastoma drug

resistance screening | (33) |

| Liu, 2021 | Fibrous

scaffolds | Silk/chitosan-based

scaffolds with web-like structures for cell adhesion | High surface area

and promotes gas/nutrient exchange | Complex fabrication

and high cost | Photothermal

therapy for post-surgical tumor ablation | (34) |

| Xu, 2023 | Microfluidic

chips | Nano/microchannels

for cell culture and analysis | Precise fluid

control, mimics vascular dynamics and high-throughput

screening | High manufacturing

complexity | CTC isolation with

90% purity | (40) |

| Hen and Jv,

2023 | Microsphere

scaffolds | Spherical carriers

(for example, alginate) loaded with cytokines/nutrients | Adjustable porosity

and enhances mass transfer | Challenges in

uniformity control | HepG2 spheroid

formation for drug testing | (44) |

| Liu, 2023 | 3D bioprinting | Customized

scaffolds using biocompatible materials | High precision and

tailored mechanical properties | High cost and

technical complexity | 3D-printed

microfluidics concentration gradient chip and a paper chip | (46) |

|

| B, Scaffold-free

models |

|

| First author,

year | Subtype |

Description |

Advantages |

Limitations |

Applications/examples | (Refs.) |

|

| Safari, 2021 | Hanging drop

culture | Cells aggregate in

liquid droplets via surface tension | Simple and limited

equipment is required | Limited droplet

volume (<50 µl) and inappropriate for large-scale use | Prostate cancer

co-culture model | (55) |

| Wang, 2019 | Spheroid

culture | Cells self-assemble

into 3D spheres in non-adherent conditions | Retains stemness

and mimics tumor heterogeneity | Variable

sphere-forming efficiency across cell types | Pancreatic CSC

enrichment | (61) |

| Kumar, 2024 | Rotary cell

culture | Simulates

microgravity via rotational motion | Low shear stress

and promotes tissue-like structures | Equipment-dependent

and parameter optimization required | Pancreatic cancer-β

cell interaction studies | (64) |

| Du, 2022 | Ultra-low

adsorption | Cells form

spheroids on non-adhesive surfaces | Easy operation and

no specialized tools | High cost of

culture plates | Effect of umbilical

cord mesenchymal stem cell supernatant on esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma spheres | (69) |

| Calamak, 2020 | Bioreactor

culture | Controlled

environment (temperature and fluid dynamics) for large-scale

culture | High

reproducibility and scalable | Complex setup and

maintenance | HCT-116 colorectal

cancer cells in a peristaltic continuous flow bioreactor to

simulate physiological hemodynamics | (71) |

| Jaganathan,

2014 | Magnetic

suspension | Magnetic

nanoparticles guide 3D cell assembly | Precise spatial

control and scaffold-free | Requires magnetic

particle integration | Magnetic suspension

coculture system for breast cancer cells and fibroblasts | (78) |

| Zhang, 2020 | Agarose

coating | Agarose gel

prevents cell adhesion and promotes spheroid formation | Non-toxic and

simple protocol | Lacks cell-matrix

interaction | HepG2

spheroid-based drug screening | (80) |

Scaffold models

Scaffolds are the most extensively used materials in

3D cell culture, acting as an artificial matrix that replicates the

complex 3D structure and key characteristics of living tissues. The

primary function of scaffolds encompasses providing structural

support for cells and serving as a medium for the diffusion of

soluble factors, thereby facilitating key cellular processes such

as adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation and

long-term survival, which collectively lead to the formation of

tissues and organs (11). The

various types of scaffolds utilized in 3D cell culture include

solid porous scaffolds, hydrogel scaffolds, non-hydrogel scaffolds,

fibrous scaffolds, microfluidic chips, microsphere scaffolds and 3D

printing techniques. Advances in enabling technologies, such as 3D

printing and microfluidic chips, are rapidly expanding the

applications of scaffold-based 3D culture systems, making them

invaluable tools for cancer research, high-throughput drug

screening and clinical translation.

Solid porous scaffolds

Solid porous scaffolds can be prepared using simple

processes (12) with materials

exhibiting good permeability and uniform density (13). Furthermore, high-performance solid

composite materials exist that are suitable in manufacturing

scaffolds that meet the requirements of diverse cell culture

systems.

Alafnan et al (14) fabricated microneedle patches using a

polyethylene glycol diacrylate diphenyl phosphine oxide polymer,

which were then coated with gemcitabine and sodium carboxymethyl

cellulose to establish an in vitro drug delivery system for

inflammatory breast cancer treatment. In a separate study, Bai

et al (15) created a

stimulus-responsive scaffold by incorporating graphene oxide (GO)

into a copolymer of polyacrylium-g-polylactic acid. When integrated

with polycaprolactone (PCL) and gambogic acid (GA), this composite

scaffold demonstrated a selective response to tumors and exhibited

notable accumulation of GO/GA in breast tumor cells under acidic

conditions in vitro, with only minor effects on normal cells

at physiological pH. This previous study suggested that

pH-responsive photothermal combination therapy is more effective in

inhibiting tumor growth compared with independent treatments.

Dettin et al (16)

engineered a novel 3D culture scaffold through the conjugation of

hyaluronic acid with ion-complementary self-assembling peptides,

which effectively promoted the proliferation of HCC1569 and

MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell lines. This platform was

successfully implemented for evaluating electroporation efficacy,

demonstrating that the 3D scaffold culture system may advance brain

tumor electroporation research compared with conventional 2D

models, providing a reliable platform for the validation of novel

electroporation-based drug delivery protocols (17).

Hydrogel scaffolds

Hydrogel scaffolds are porous 3D structures that

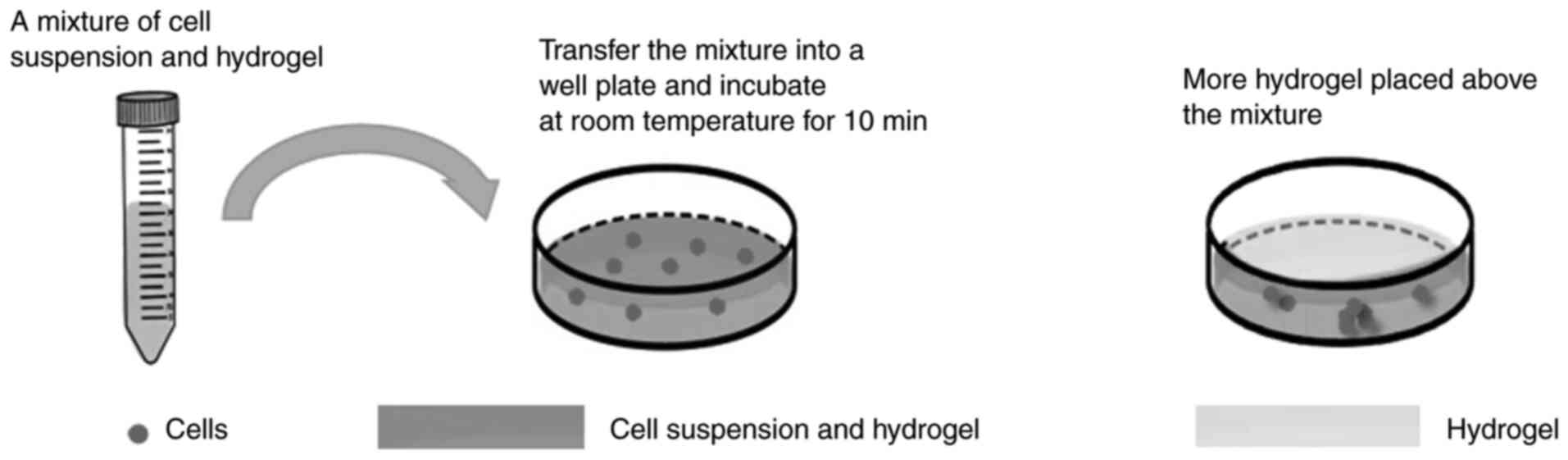

support cell adhesion, proliferation and migration. As shown in

Fig. 1, the process of hydrogel

scaffold-based 3D cell culture involves mixing the cell suspension

with hydrogel followed by incubation for in vitro 3D

cultivation. In tumor cell culture, naturally derived hydrogel

scaffolds sourced from the ECM have demonstrated notable support,

plasticity and biocompatibility (18,19),

whereas hydrogels derived from artificial tissue culture have also

been extensively implemented (18).

The selection of appropriate scaffold materials is key to 3D

culture and materials optimal for cell viability, proliferation,

observation, detection and other pertinent aspects should be used

(20). Prompted by these

considerations, researchers have developed a series of 3D hydrogel

scaffold materials through systematic comparison of diverse culture

methodologies, which are now extensively employed in 3D cultivation

of tumor cells (11,21). Hydrogels exhibit physical properties

resembling human tissues, including softness, elasticity and

permeability, which enable them to provide structural support for

cells, facilitate nutrient diffusion and assist in metabolite

transport. However, hydrogel scaffolds have certain limitations;

for example, variations in material composition may impede nutrient

influx and distribution, adversely affecting cell culture (22). Commonly used gel-forming materials

include fibrin, agarose, polyethylene and ethylene glycol. Fu et

al (23) developed a

fiber-hydrogel composite scaffold loaded with platelet-rich plasma,

which combined efficient material transport with enhanced cell

adhesion and exhibited an elastic modulus similar to that of breast

tumor tissue, thereby promoting cell aggregation and reducing

resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Therefore, this composite

scaffold provides a valuable platform for in vitro oncology

research and antitumor drug efficacy prediction. Quazi et al

(24) constructed a polypeptide

drug delivery carrier using stepwise functionalization of a

nano-DNA hydrogel scaffold, which was loaded with a

cell-penetrating anticancer peptide via electrostatic adsorption to

achieve light-triggered drug delivery. This delivery system

demonstrated safety, specificity and high efficiency, establishing

an ideal platform for anticancer peptide administration and

offering a promising strategy for future cancer treatment. By

integrating a microfluidic system with a soft hydrogel, Jiang et

al (25) established a 3D in

vitro model mimicking the in vivo lung gland

microenvironment. Analysis of cancer cell morphology, proliferation

and invasion within this model provided key insights into the

invasive mechanisms of in vivo lung cancer cells.

Engineering of PCL into nano-porous PCL (NP-PCL)

yields an emerging biomaterial characterized by an extensive

nanoporous network structure, which provides chondrocytes with an

improved growth environment and markedly enlarged adsorption

surface area. Furthermore, NP-PCL exhibits notable mechanical

properties and closely mimics the structural characteristics of

native bone, thereby markedly enhancing chondrocyte adhesion and

proliferation (26).

Non-hydrogel scaffolds

Natural scaffolds, fabricated from biological

substances including collagen, chitosan, polysaccharides, seaweed

salts, ECM components and other materials (27), exhibit high biocompatibility and

biodegradability. However, their structural strength is typically

inferior to that of synthetic alternatives. The development of

novel drug delivery systems has facilitated the engineering of

chitosan-based targeted formulations for sustained and controlled

release, and targeted delivery, which offer notable advantages for

enhanced drug absorption, improved bioavailability and reduced

adverse effects. A key example is folic acid-modified

nanoparticles, synthesized by conjugating folic acid onto chitosan

nanoparticles (28). Upon loading

with chemotherapeutic agents, such as paclitaxel and fluorouracil

(29), they can be internalized

into tumor cells via endocytosis, thereby enabling the recognition

and elimination of an extensive range of cancer cells (30). Paclitaxel demonstrates marked

efficacy in the treatment of colon cancer. It exerts its

therapeutic effect by interfering with microtubule dynamics, which

are essential for cancer cell division, thereby inhibiting cell

proliferation and ultimately inducing apoptosis (31).

Chaicharoenaudomrung et al (32) demonstrated that human glioblastoma

cells cultured in 3D calcium-alginate scaffolds exhibited reduced

proliferation, enhanced tumor sphere formation, upregulation of

stemness-associated genes (CD133, Sox2, Nestin and Musashi-1) and

increased expression of differentiation-related markers (glial

fibrillary acidic protein and β-tubulin III) compared with those

under 2D conditions. Further investigation into the cellular

response to anticancer agents, including doxorubicin and

cordycepin, revealed that cells in the 3D scaffold system developed

markedly stronger drug resistance. These findings support the

utility of 3D calcium-alginate cultures as a valuable platform for

anticancer drug-screening and resistance mechanism analysis. In a

related study, Kim et al (33) employed 3D matrix scaffolds to

culture two bladder cancer cell lines, SBT31A and T24, both

expressing cyclin D1b mRNA, and evaluated the antitumor effects of

cyclin D1b knockdown via small interfering RNA. Their results

indicated that suppression of cyclin D1b expression promoted

apoptosis, attenuated cancer stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) and therefore, suppressed malignant phenotypes in

bladder cancer cells.

Fibrous scaffolds

Fibrous scaffold materials offer notable advantages

due to their fibrillar architecture, which provides extensive

surface area for cell attachment, proliferation and

differentiation. These scaffolds feature a dense, spiderweb-like

pore network within a pliable 3D structure, facilitating nutrient

exchange and gas transport. They are primarily categorized into

natural fiber scaffolds (for example, silk fibroin and chitosan)

and synthetic fiber scaffolds (for example, PCL).

Liu et al (34) constructed a core-shell fibrous

scaffold by uniformly coating 3D-printed alginate-gelatin scaffolds

first with PCL and subsequently with polydopamine to impart a

pronounced photothermal effect, thereby achieving on-demand drug

release triggered by near-infrared irradiation. The released

doxorubicin, in combination with photothermal therapy, demonstrated

effective liver cancer suppression and ablation both in

vitro and in vivo. This scaffold presents a promising

strategy for localized tumor therapy and tissue regeneration,

particularly in patients with cancer post-surgery. It can be

implanted at the resection site to eliminate residual or recurrent

cancer cells while promoting the repair of surgically induced

tissue defects.

Microfluidic chips

Microfluidic chips are technological platforms

fabricated by etching microscale to even nanoscale channels and

analytical detection units on substrates such as glass and silicon

(35). Functioning as a miniature

technological system, these devices enable diverse applications

including microscale sample analysis, cell culture and signal

transduction (36). Their internal

architecture resembles a miniaturized chemical laboratory,

incorporating fluidic channels, reaction platforms, analytical

detection modules and separation components, with dimensional

characteristics comparable to those of human capillaries (37). This technology demonstrates multiple

advantages, including precise fluid flow control, minimized reagent

consumption, enhanced detection efficiency and reduced processing

times, while simultaneously enabling comprehensive simulation of

in vivo microenvironments and supporting 3D tumor cell

culture (38).

Microfluidics technology demonstrates unique

advantages in modulating the physicochemical properties that govern

drug release behavior. A previous study by Matsuura-Sawada et

al (39) revealed that both

lipid concentration and flow rate ratio markedly influenced

liposome structure and drug release profiles. When the lipid

concentration was maintained at ≥50 mmol/l with a flow rate ratio

of 3, multilamellar liposomes were predominantly formed. The

barrier effect conferred by their bilayer lipid membranes markedly

reduced the drug release rate, resulting in a cumulative release of

<58% over 72 h. By contrast, under conditions of low lipid

concentration (10 mmol/l) or a high flow rate ratio (flow rate

ratio=9), unilamellar liposomes became the dominant structure,

leading to a comparatively faster drug release. By flexibly

adjusting these two key parameters, liposomes with varying

structures can be engineered and their proportions controlled,

thereby enabling precise regulation of drug release kinetics. Xu

et al (40) developed an

integrated microfluidics chip for online labeling, separation and

enrichment of rare circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from blood

samples, followed by analysis via inductively coupled plasma mass

spectrometry (ICP-MS). Using HepG2 cells as a model, the team

combined single-cell ICP-MS to quantitatively analyze

asialoglycoprotein receptors on individual cells.

Lanthanide-labeled anti-asialoglycoprotein monoclonal antibodies

and anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule-modified magnetic beads

were prepared as signal probes and magnetic probes, respectively,

enabling specific cellular recognition. Using the application of

targeted magnetic separation techniques for aggregation and sorting

within a designated separation zone, both the average cell recovery

rate and purity of HepG2 cells were observed to be notably high.

This methodology was thus established as a viable strategy for the

absolute quantification of asialoglycoprotein on individual liver

cancer cells, providing an efficient analytical platform to

investigate targeted drug delivery in cancer therapeutics.

Microsphere scaffolds

Microsphere scaffolds, characterized by spherical

structures with particle sizes ranging between 10 and 100 µm,

contain cytokines and nutrients key to stimulating cell

proliferation and division (41).

By adjusting preparation parameters or incorporating bioactive

components such as hepatic decellularized matrix (42), the mass transfer efficiency of these

scaffolds can be markedly enhanced, thereby further mimicking the

in vivo microenvironment, and promoting the proliferation

and invasion of tumor cells.

Qiu et al (43) achieved efficient separation of

CTC-like particles using an acoustic fluidic chip coupling system,

utilizing carboxylic acid-functionalized polystyrene microspheres

encapsulating aminated mesoporous acoustic particles to simulate

CTCs. Hen et al (44)

prepared uniformly sized methacrylated alginate microspheres via

microfluidic technology combined with online UV-induced

crosslinking and subsequently fabricated large-pore microspheres

using freeze-drying techniques. Evaluation using HepG2 cells as a

model system demonstrated that these microspheres supported cell

aggregation into spheroids with viability >85% and promoted

cellular proliferation, indicating their suitability as 3D cell

culture scaffolds. The results confirmed that these scaffolds

sustained anticancer drug release and effectively suppressed cancer

cell proliferation in vitro, suggesting their potential

applications in cancer research and drug screening in the

future.

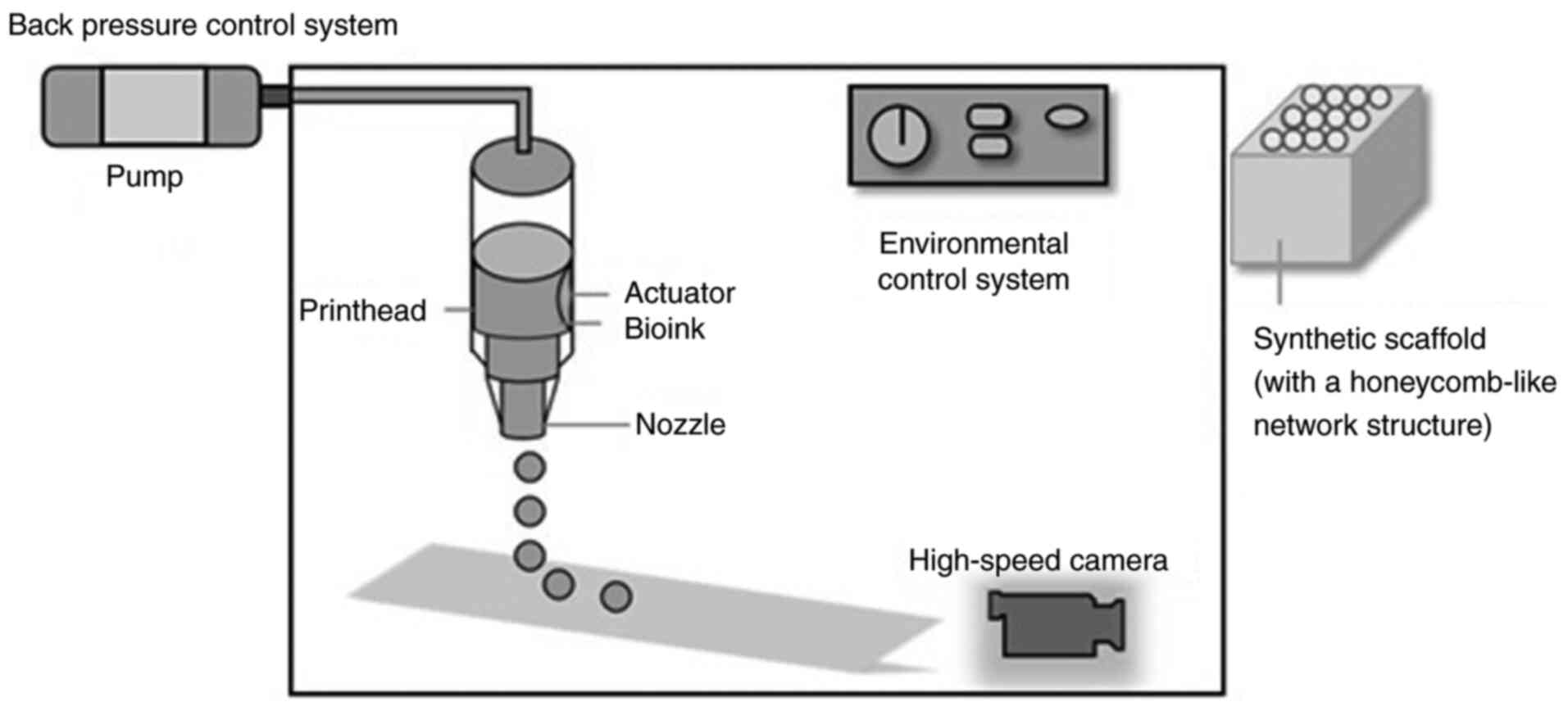

3D bioprinting

3D bioprinting is an advanced manufacturing

technique that fabricates solid structures through the integration

of computer-aided design, systematic analysis of target scaffold

characteristics (including material properties, geometry and

dimensions) and programmed processing procedures. Fig. 2 illustrates the control system

components for 3D bioprinting, including the pump, printhead,

actuator, bioink, nozzle, environmental control system and

high-speed camera, along with the resulting honeycomb-like scaffold

model produced after printing. The integration of 3D bioprinting

with alternative scaffold materials for tumor cell culture and

viability assessment offers distinct advantages, particularly in

achieving enhanced mechanical strength and toughness along with

demonstrated non-cytotoxic properties. However, this special

culture method imposes strict requirements on both computers and

printers, and its high cost combined with these equipment demands

currently limits its application (45).

Liu et al (46) developed an integrated platform

comprising a 3D-printed microfluidics concentration gradient chip

and a paper chip to investigate the effects of hydrogen sulfide on

tumor cells and intracellular signaling molecules, demonstrating

that sustained exposure to low concentrations effectively induced

apoptosis and suppressed proliferation in malignant cells. Jin

et al (47) constructed a

concentric cylindrical tetra-culture model containing gallbladder

carcinoma (GBC) and endothelial cells, fibroblasts and macrophages

using 3D bioprinting technology, and validated the model

characteristics by combining hematoxylin and eosin staining,

immunofluorescence labeling and single-cell RNA sequencing. Using

comparative transcriptomics analysis, this model was reported to

effectively recapitulate key features of the tumor microenvironment

and heterogeneity, induce more aggressive tumor cell phenotypes and

provide a high-fidelity platform for GBC biological studies and

antitumor drug development.

Scaffold-free culture

Scaffold-free cell culture approaches fundamentally

promote the self-assembly of tumor cells into 3D spheroid-like

aggregates through autonomous cellular processes (48). Established methodologies encompass

hanging drop cultures, spheroid formation techniques, the rotary

cell culture system (RCCS), ultra-low adsorption cell culture,

bioreactor cultures, magnetic suspension culture and agarose

coating protocols (49). Cellular

models derived from these platforms demonstrate advantages of

reduced experimental costs, operational simplicity and suitability

for industrial production (50),

rendering them particularly suitable for high-throughput

drug-screening applications. However, its extensive implementation

faces challenges including prolonged culture durations, high

equipment investment and limited imaging penetration, which makes

it difficult to ensure the uniformity of experimental results

(51).

Hanging drop culture

The hanging drop method involves depositing cell

suspension onto the bottom surface of a culture dish or plate,

forming hanging drops via liquid surface tension. The vessel is

then inverted, enabling cells to aggregate at the bottom of the

drops under gravity through intercellular adhesion, thereby forming

3D structures (52). While this

technique offers notable advantages in generating homogeneous

spheres with controllable size and shape (53), it presents technical challenges for

subsequent drug treatment procedures and morphological analysis,

thereby limiting its practical applicability for large-scale

cultivation.

Rodoplu et al (54) demonstrated a notable increase in

both the percentage area and total length of tumor

angiogenesis-associated blood vessels following a 6-day co-culture

of embryonic bodies and tumor spheroids on a microfluidic

hanging-drop platform, which establishes this methodology as a

straightforward and efficient approach for generating co-cultured

cell spheroids. Safari et al (55) employed the hanging drop technique to

establish a 3D co-culture model of prostate cancer cells, revealing

that conditioned medium derived from human amniotic mesenchymal

stromal cells exhibited potent anticancer activity, a finding that

provides compelling evidence supporting the therapeutic potential

of stem cell-based strategies in suppressing prostate cancer

progression.

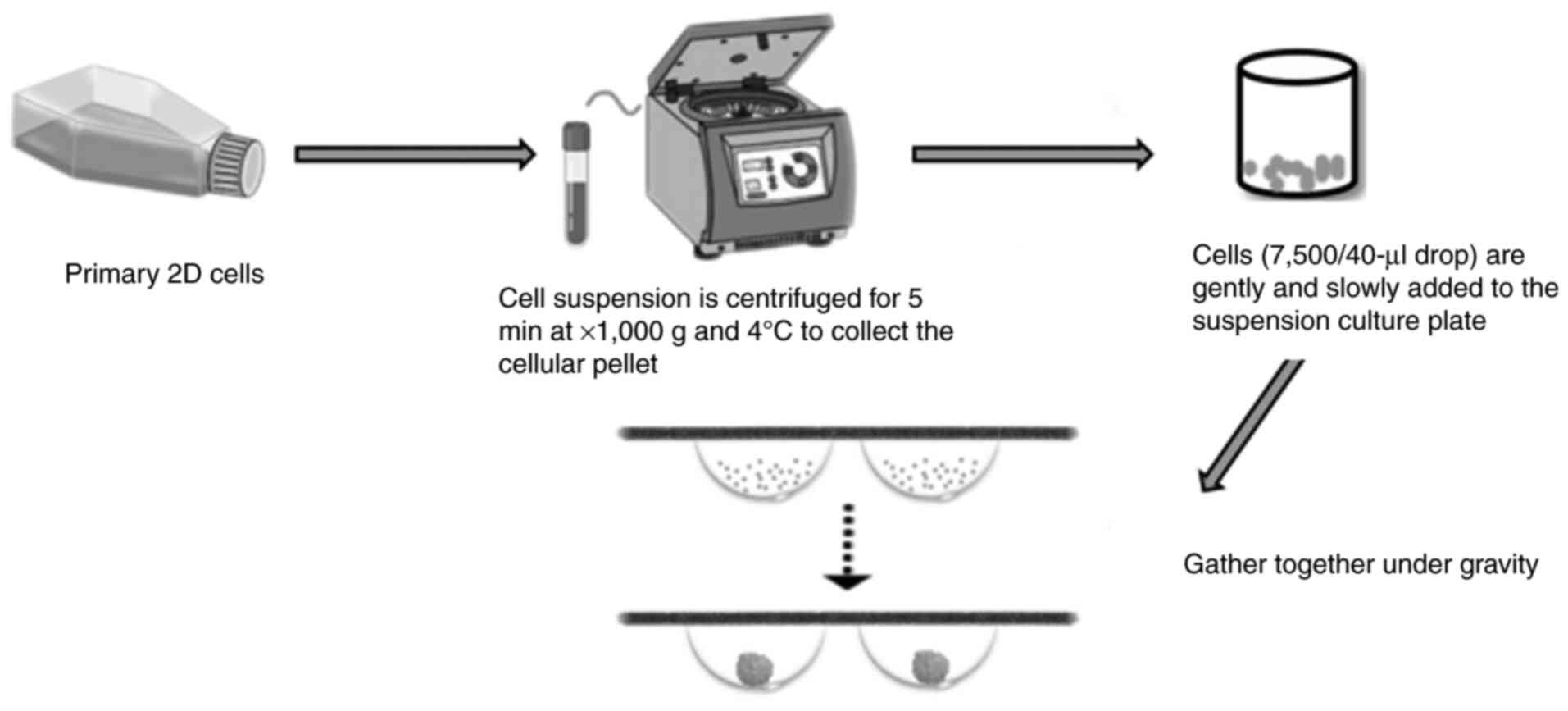

Spheroid culture

The spheroid culture method refers to a technique

wherein cells aggregate to form clump-like cellular assemblages

that subsequently develop into spherical structures through 3D

cultivation (56). Fig. 3 illustrates the process of forming

3D cell spheroids: 2D cultured cells are first grown to the

logarithmic phase, then centrifuged. The harvested cells are

diluted to create a cell suspension, which is uniformly dispensed

into multi-well plates. Under gravity, the cells aggregate to form

3D spheroids. For cancer stem cells (CSCs), their sphere-forming

capacity serves as a key diagnostic parameter in evaluating the

self-renewal potential of individual cells under specific growth

conditions (57). While tumor cells

such as glioma and breast carcinoma cells demonstrate relatively

high sphere-forming rates, epithelial-derived tumor cells including

hepatocellular and colorectal carcinoma cells tend to exhibit

comparatively lower sphere-forming rates (58). Therefore, when investigating the

growth potential of these tumor cell types, culture conditions

should prevent adherent growth while allowing tumor cells to form

spherical aggregates in specialized media. While this method is

relatively low-cost, the thickness of the formed spheroids and

their inherent light scattering/absorption properties markedly

affect imaging quality, thus requiring more sophisticated optical

instruments and advanced analytical algorithms to achieve accurate

data interpretation.

Xue et al (59) cultivated spheroids in specialized

culture plates and demonstrated that silica stimulation induced an

anti-apoptotic phenotype in myofibroblasts through activation of

the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/Bax pathway. Sun

et al (60) conducted

comparative assessment of 22 liver injury-positive and 5 liver

injury-negative compounds using lung cancer cells cultured in

spheroid or 2D systems, revealing that the spheroid culture

markedly enhanced model sensitivity in detecting compound

cytotoxicity compared with conventional 2D culture. Wang et

al (61) demonstrated that

pancreatic CSCs enriched via spheroid culture methods exhibited

higher co-expression levels of stemness-related genes CD24 and CD44

compared with conventional 2D cell culture systems, thus

establishing spheroid culture as a suitable platform in maintaining

pancreatic CSCs under in vitro conditions. Raggi et

al (62) employed spheroid

culture to enrich stem-like subpopulations in human intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma and via extracellular flux analysis using

Seahorse technology coupled with high-resolution respiratory

measurements, the study established that the respiratory phenotype

of cholangiocarcinoma cells in the spheroid culture was markedly

more efficient compared with that in the monolayer culture. The

spheroid culture platform enabled direct microscopic visualization

of morphological characteristics and growth status within

individual wells, while simultaneously facilitating relatively

straightforward environmental control during experimental

manipulations, such as reagent addition and medium replacement,

thereby offering particular advantages for implementation in

small-scale laboratory settings.

RCCS

The RCCS simulates microgravity conditions by

inducing rotational motion of cells, tissues and culture medium in

a state approximating free fall (63), which effectively promotes cellular

proliferation and differentiation while facilitating intercellular

signaling transduction. Operating without propellers or mechanical

agitators, the system generates minimal shear stress that poses

negligible cellular damage, with additionally adjustable rotation

speeds enabling controlled reduction of sedimentation rates as

cellular aggregates develop.

Utilizing a 785 nm semiconductor laser for cellular

stimulation and Raman spectra acquisition, Kumar et al

(64) established a 3D RCCS to

co-culture multiple pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cell

lines with MIN6 pancreatic β-cells, while systematically

investigating morphological characteristics and viability using

integrated time-lapse imaging, confocal and scanning electron

microscopy, and immunohistochemical analysis. This methodology

successfully generated a co-culture platform capable of forming 3D

PDAC spheroids and β-cell aggregates (pseudo-islets), with cellular

surface morphology and growth patterns closely recapitulating the

in vivo microenvironment, while further demonstrating the

propensity of PDAC cells to surround and invade the pseudo-islet

structures. Belloni et al (65) cultured bone marrow stromal cells

with tumor cells in a RCCS, revealing that this 3D culture model

effectively recapitulated tumor-mesenchymal transition processes

and provided a physiologically relevant platform for drug-screening

applications.

Ultra-low adsorption cell culture

The ultra-low adsorption cell culture method offers

operational simplicity without requiring additional equipment,

employing only round-bottomed vessels coated with inert,

non-adhesive surfaces to prevent cellular attachment to vessel

walls, thereby promoting cell aggregation and adhesion into 3D

spheroids. However, the high cost of these specialized culture

dishes or plates restricts their widespread implementation

(66).

Using ultra-low adsorption plates, Malhão et

al (67) generated

multicellular aggregates from four breast cell lines and

characterized them using morphometric analysis, qualitative

cytology and quantitative immunohistochemistry, revealing that

while each cell line formed homogeneous multicellular aggregates,

distinct structural heterogeneity existed between different lines.

In another experimental study (68), the team employed this ultra-low

adsorption approach to cultivate 3D spheroids, observing compact

structural integrity, robust cellular viability and straightforward

procedural implementation. In a separate study, Du et al

(69) demonstrated that culture

supernatants from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells markedly

enhanced spheroid formation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

cultures prepared using ultra-low adsorption plates.

Bioreactor culture

Bioreactors represent specialized cultivation

systems engineered to accommodate specific culture methodologies,

with key parameters, including temperature, humidity, pressure,

nutrient supply, CO2 concentration, and physical or

chemical stimuli, mimicking in vivo conditions with high

fidelity. This configuration enables more precise regulation and

enhanced controllability compared with alternative culture

environments while facilitating streamlined tumor cell cultivation,

thereby finding extensive applications in biomedical research

(70).

Calamak et al (71) cultured HCT-116 colorectal cancer

cells in a peristaltic continuous flow bioreactor to simulate

physiological hemodynamics, and demonstrated that this system

induces reprogramming of cancer cells toward a mesenchymal niche

while accurately replicating circulatory conditions. These findings

established that hemodynamic forces alter membrane composition and

morphological characteristics in malignant cells, providing notable

insights in the development of novel cancer therapeutics. Huo et

al (72) investigated a 3D

perfusion bioreactor that maintained neuroblastoma tissue

architecture and cellular matrix integrity for 7 days, enabling

continuous drug response monitoring using isothermal

microcalorimetry. This platform additionally incorporated 56

metabolic assessment methods with rapid detection and high

sensitivity to advance personalized treatment for neuroblastoma.

Bober et al (73) designed a

bioreactor-based 3D culture system combining non-invasive proton

magnetic resonance (MR) relaxation time measurements at 1.5 Tesla

with immunohistochemical analysis to evaluate trastuzumab delivery

efficiency in breast cancer cells (CRL2314) vs. normal controls

(HTB-125). The results revealed notably reduced relaxation times in

both treated and untreated CRL2314 cells compared with HTB-125

cells, validating MR relaxation time analysis as an effective

approach in assessing drug responses and cellular viability in 3D

culture models.

Magnetic suspension culture

Magnetic suspension culture employs a hydrogel

medium composed of bacteriophages and magnetic iron oxide particles

to establish 3D cultures, enabling spatial control over cellular

aggregates through magnetic manipulation to achieve multicellular

organization in coculture systems (74). Nevertheless, this technique presents

several limitations: The magnetic beads are costly, potentially

cytotoxic at elevated concentrations and enable limited aggregate

yield (75). By integrating

quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics with magnetic

suspension culture, Vu et al (76) characterized proteomic alterations in

squamous cell carcinoma cells, demonstrating that the absence of

xenogenic protein scaffolds permits integrated analysis of cells

with their endogenous ECM. Magnetic suspension has thus been

demonstrated as a valuable methodology in elucidating proteomic

dynamics underlying 3D tissue architecture. Qin et al

(77) identified circadian rhythms

in tumor cells maintained in suspension culture, advancing drug

delivery strategies through stage-specific pharmacological

interventions. Jaganathan et al (78) developed a magnetic suspension

coculture system for breast cancer cells and fibroblasts,

quantifying tumor size and cellular density while comparing

phenotypic characteristics with in vivo tumors and examining

matrix protein composition. Their results confirmed that this

approach can facilitate precise control over tumor cell composition

and density, rapidly generating large-scale breast tumor models

within 24 h that markedly recapitulate the in vivo tumor

microenvironment for antitumor drug evaluation.

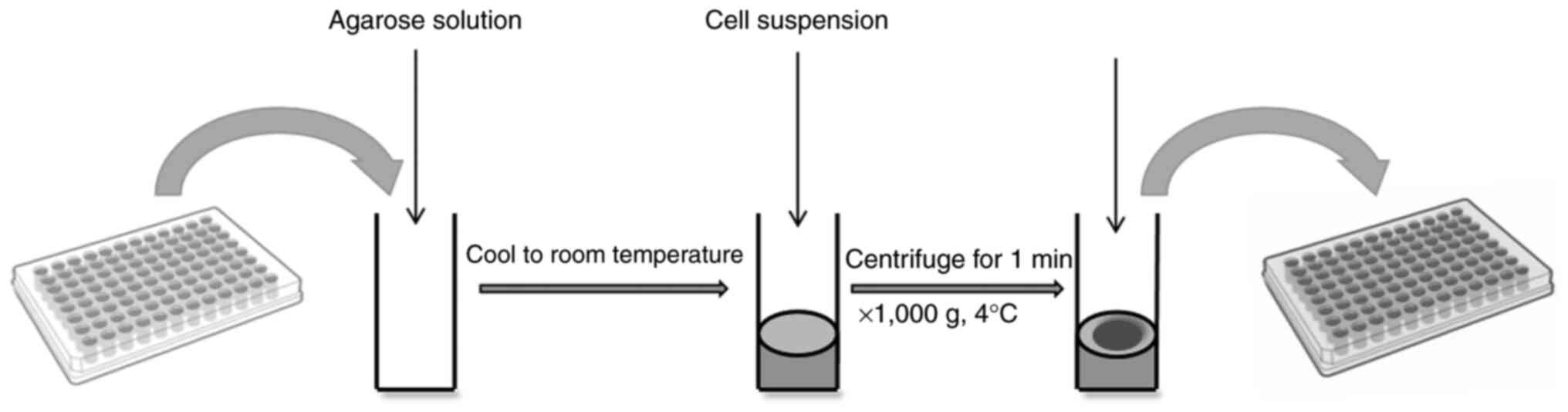

Agarose coating

Agarose, a polysaccharide extracted from marine

algae, dissolves in boiling aqueous solution and solidifies into

non-cytotoxic gels upon cooling. These resultant gels inherently

lack cell adhesion motifs, thereby effectively preventing the

attachment of human and animal cells (79). Fig.

4 illustrates the following procedure: A quantified agarose

solution is dispensed into a 96-well plate, cooled to room

temperature and subsequently supplemented with a quantified cell

suspension for culture. Ultimately, the formation of clustered cell

spheroids is observed.

Zhang et al (80) established a 3D HepG2 cell model

using 96-well flat-bottom plates combined with agarose gel,

observing that well-defined cellular spheroids formed on the

agarose surface when seeding densities were maintained between

1.975×103 and 1×104 cells/well. With

increasing cell inoculation numbers, spheroid volumes expanded

progressively, demonstrating a strong linear association within the

density range of 1.975–6.667×103 cells per well. Chen

et al (81) systematically

investigated the effects of primary components of tea polyphenols

on breast CSCs cultured via the agarose-coating method. Using

integrated experimental approaches including cell migration assays,

scratch tests and cellular repair assessments among other

techniques, the research team established that transcriptional

downregulation of key EMT genes effectively suppressed invasive

phenotypes in breast CSCs, diminished transcriptional activation of

breast cancer marker genes, thus preventing manifestation of

self-renewal characteristics. These findings markedly expand the

potential pharmacological applications of primary tea polyphenol

components in anticancer therapeutic development. Capitalizing on

the unique thermally-responsive properties of agarose that undergo

physical cross-linking at 35–40°C, Gong et al (82) employed agarose as a gelatin

substitute for 3D bioprinting at both 10 and 24°C. Comparative

evaluation revealed that structures fabricated using agarose

pre-gelation methods exhibited notably enhanced dimensional

precision, structural stability and mechanical rigidity compared

with those produced using gelatin pre-gelation approaches.

Application of 3D culture technique for

tumor cells

3D cell culture models have demonstrated marked

potential in both assessing drug safety and efficacy, and modeling

diverse pathological conditions (83). This 3D culture technology serves as

a versatile platform for culturing tumor cells in vitro,

enabling systematic investigation of oncogenesis, metastatic

progression, invasive behavior, recurrence patterns and therapeutic

strategies, while simultaneously facilitating drug discovery and

screening applications (84).

Biological behavior of tumors

3D tumor cell culture technology enables more

accurate simulation of the authentic in vivo growth

environment under in vitro conditions (85), demonstrating unique advantages and

profound implications for investigating diverse tumor biological

behaviors, therapeutic interventions and drug-screening processes

(86). For example,

CD271+ uveal melanoma stem cells may undergo

vasculogenic mimicry in 3D Matrigel culture (87). Another previous study revealed that

nicastrin, a novel type I transmembrane glycoprotein, is associated

with breast cancer stem cell properties, as determined using

Matrigel culture (88).

Tumor angiogenesis

Vascular endothelial growth factor serves as a key

regulator of pathological angiogenesis in tumors, activating

endothelial cells to migrate, develop tip cells and ultimately

anastomose into nascent blood vessels (89). To access the circulatory system,

malignant cells must reside in proximity to the vasculature, due to

their fundamental dependence on oxygen and nutrient supply for

survival and proliferation. This complex process necessitates

coordinated interactions among cells, extracellular matrices and

signaling networks. 3D tumor cell culture systems can generate

neovascular networks that closely mirror native vascular

architecture, thereby establishing an advanced platform for

investigating tumor migration and invasion mechanisms in

vitro (90). Methods to

vascularize various tissue/organ types using several synthetic and

naturally occurring biomaterials have already been established. For

example, Lazzari et al (91)

constructed a poly-HEMA-based 3D tumor model by co-culturing

PANC-1, MRC-5 and human umbilical vein endothelial cells to

synthesize vascularized tumor spheroids of pancreatic cancer

cells.

Tumor microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment comprises multiple

cellular components, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts,

pericytes, adipocytes and immune cells, which collectively

contribute to tumor initiation, progression and metastasis

(92). Through dynamic

intercellular interactions, signal transduction and cellular

communication, it provides key support for tumor survival and

growth, while simultaneously modulating key processes such as

immune responses, angiogenesis and drug resistance (93). Furthermore, the tumor

microenvironment facilitates proto-oncogene expression and

tumor-promoting protein production while impairing immune cell

functionality. Due to the bidirectional regulatory interplay

between tumors and their microenvironment, elucidating these

complex mechanisms carries notable importance in understanding

tumor biology, and advancing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies

(94). Amaral et al

(95) employed two different 3D

cell culture techniques, the hanging drop and the forced floating

with ultra-low attachment plates, to form human bladder cancer RT4

spheroids. These models are gaining popularity, given their ability

to reproduce key aspects of the tumor microenvironment, concerning

the 3D tumor architecture, as well as the interactions of tumor

cells with the extracellular matrix and surrounding non-tumor cells

(86).

CSCs

CSCs, which are characterized by self-renewal

capacity, differentiation potential, high tumorigenicity and

enhanced drug resistance, can withstand non-specific treatments

including radiotherapy and chemotherapy, while serving key roles in

tumor initiation, metastatic progression, drug resistance

development and disease recurrence (96). The self-renewal capability and

unlimited proliferative potential of these cells represent

fundamental mechanisms sustaining tumor cell population viability,

and their migratory activity may initiate tumor cell dissemination

(97). When maintained in prolonged

dormant states, CSCs harbor diverse drug-resistant molecules and

demonstrate reduced sensitivity to exogenous physicochemical agents

that typically eliminate tumor cells, such as anthracyclines,

taxanes, anti-metabolites and alkylating agents (98) In recent years, the identification of

novel targets specifically present in CSCs has emerged as a

promising direction in the development of innovative antitumor

therapeutics (99–101). CSCs grown in 3D model assays offer

marked potential in understanding therapy response rates. Such

cells have already been successfully isolated from a 3D model of

human osteosarcoma treated with epirubicin. In this manner, 3D CSC

models have provided novel insights into tumor drug resistance

(102).

Development and screening of antitumor

drugs

The field of anticancer drug development continues

to grow with increasing demand for specifically targeted

therapeutics (103). However,

conventional 2D culture-based drug-screening platforms exhibit

notable limitations, as antineoplastic efficacy observed in

vitro frequently fails to translate to clinical settings

(104). This translational gap

primarily originates from the inherent inability of 2D systems to

replicate key features of the native tumor microenvironment

(105), which serves a key role in

driving tumor progression, metastatic dissemination and drug

resistance mechanisms. Therefore, developing 3D culture models that

more accurately mimic tumor cell interactions with ECM components

is of key importance. Such advanced models provide vital platforms

for precisely evaluating chemotherapeutic performance and cytotoxic

responses, thereby markedly enhancing the predictive capacity of

high-throughput screening for anticancer compounds.

To address this challenge, researchers have

developed a 3D ex vivo tumor model system utilizing the

AXTEX-4D™ platform (106). This

system is characterized by its capacity to generate physiologically

relevant microenvironments through self-assembly of endogenously

secreted matrix components without requiring exogenous scaffolding

materials, thereby spontaneously establishing biochemical gradients

that better approximate in vivo conditions. In

immuno-oncology applications, the platform has demonstrated

efficacy in evaluating therapeutic outcomes through monitoring key

parameters, including immune cell proliferation, migration,

infiltration, cytokine secretion and tumor-specific cytotoxicity

(107). As a highly integrated

physiomimetic system, it serves as a robust platform for

high-throughput screening of immunotherapeutic agents, markedly

enhancing the predictive accuracy and translational relevance of

preclinical drug evaluation (105).

Rosendahl et al (108) established 3D coculture models of

MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell lines within

2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine 1-oxyl cellulose nanofibril

(TEMPO-CNF) scaffolds, observing multilayered tumor growth with

distinct morphological patterns, while demonstrating that these

TEMPO-CNF scaffolds upregulated the expression of stem cell marker

CD44 and migration markers Vimentin/SNAI1 in MCF7 cells compared

with 2D culture systems, thereby establishing TEMPO-CNF as a

promising biomaterial in developing 3D culture platforms applicable

to anticancer drug screening.

Significance and prospects

Technical challenges requiring

resolution

Notwithstanding their enhanced physiological

relevance, the broad implementation of 3D models faces constraints

from several key technical hurdles.

First, operational expenses markedly exceed those of

conventional 2D systems, primarily due to dependence on specialized

and costly components such as commercial basement membrane extracts

and sophisticated bioreactor systems designed for extended culture

maintenance and perfusion requirements. Furthermore,

high-resolution imaging of 3D specimens typically necessitates

advanced instrumentation including confocal or light sheet

microscopy, representing considerable additional investment. These

cumulative costs restrict accessibility for resource-constrained

laboratories and thereby reduce implementation scalability in

high-throughput screening campaigns.

Second, reproducibility and standardization issues

present notable obstacles. Batch-to-batch variations in scaffold

materials introduce considerable experimental variables that

compromise result reliability (109), while manual production methods in

scaffold-free models frequently generate spheroids with inadequate

size uniformity that consequently demonstrate elevated data

variability (110). The field

currently lacks unified culture protocols, standardized analytical

criteria and clearly defined efficacy endpoints, thus preventing

direct comparison and integration of experimental data across

different laboratories.

Furthermore, the intrinsic 3D architecture of these

models creates notable challenges for imaging procedures and

subsequent data interpretation. From an optical perspective, light

scattering and absorption phenomena restrict both imaging depth and

resolution, particularly in specimens >200 µm in thickness,

often necessitating specialized methodologies such as tissue

clearing methods or light sheet fluorescence microscopy (111). From an analytical standpoint,

extracting quantitative parameters from 3D images, including

cellular viability, morphological characteristics and spatial

heterogeneity in protein expression, proves markedly more complex

compared with corresponding 2D analyses (112). This process requires sophisticated

computational algorithms and artificial intelligence capabilities

to execute tasks involving 3D cell segmentation, structural

reconstruction and phenotypic characterization (113), thereby demanding enhanced

computational resources and specialized technical expertise.

Future directions and innovation

To address these challenges and facilitate clinical

translation of 3D tumor models, future investigations should

concentrate on the following key domains.

Technological integration and

automation

i) 3D bioprinting. Bioprinting technology serves as

a robust methodology to address standardization challenges by

enabling precise and reproducible deposition of cellular components

and biomaterials. Through the layered assembly of multiple cell

types with gradient biofactors, this approach facilitates the

construction of highly biomimetic and structurally controllable

tumor microenvironment models (114). These advanced systems prove

particularly valuable for investigating complex pathological

processes including tumor invasion and metastatic progression

(114). Long-term perspectives

encompass applications in vascular regeneration and cartilage

repair, with potential clinical translation toward surgical

reconstruction of blood vessels and cartilage tissues, alongside

the development of personalized drug delivery platforms (115).

ii) Organ-on-a-chip platforms. The integration of 3D

tumor models with microfluidics technology enables the development

of organ-on-a-chip systems. These platforms dynamically simulate

physiological parameters including hemodynamic flows, mechanical

stresses and inter-tissue interactions, thereby achieving more

accurate recapitulation of in vivo drug distribution and

metabolic processing. Such technological synergy provides an

innovative framework for enhancing the physiological relevance of

preclinical drug evaluation methodologies (116).

Data integration and intelligent

analysis

i) Multi-omics data integration. Integrating

phenotypic readouts from 3D models with subsequent multi-omics

analyses enables elucidation of underlying molecular mechanisms

(117), where this model-to-omics

strategy establishes a key bridge connecting observed phenotypic

responses with their mechanistic drivers, while facilitating

identification of novel therapeutic targets and predictive

biomarkers.

ii) Artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Targeting artificial intelligence to process complex 3D imaging and

multi-omics datasets allows identification of patterns

imperceptible through conventional analysis (118), enabling automated high-content

phenotypic screening and supporting development of robust

predictive models in evaluating therapeutic efficacy and patient

prognosis.

Defining clinical translation

pathways

Future research endeavors should prioritize

systematic validation of 3D models by rigorously establishing

associations between their predictive accuracy and clinical

outcomes. Advancing standardization of technologies, such as 3D

bioprinting and organ-on-a-chip systems, while integrating them

comprehensively with multi-omics analyses and artificial

intelligence will enable the development of more predictive tumor

models. These advancements will not only improve the fundamental

understanding of cancer biology but also expedite the development

of innovative anticancer therapies, ultimately propelling the field

of precision oncology toward novel frontiers.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was funded by the Scientific Research Project

of the Department of Education of Liaoning Province (grant no.

LQ2020021).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

SD and HL conceptualized and designed the present

review. SD, HW, DX, JY and SM drafted the manuscript, and prepared

the tables and figures. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Madrid MF, Mendoza EN, Padilla AL,

Choquenaira-Quispe C, de Jesus Guimarães C, de Melo Pereira JV,

Barros-Nepomuceno FWA, Lopes Dos Santos I, Pessoa C, de Moraes

Filho MO, et al: In vitro models to evaluate multidrug resistance

in cancer cells: Biochemical and morphological techniques and

pharmacological strategies. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev.

28:1–27. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Faber MN, Sojan JM, Saraiva M, van West P

and Secombes CJ: Development of a 3D spheroid cell culture system

from fish cell lines for in vitro infection studies: Evaluation

with Saprolegnia parasitica. J Fish Dis. 44:701–710. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Langhans SA: Using 3D in vitro cell

culture models in Anti-cancer drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug

Discov. 16:841–850. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lu X, Liu X, Zhong H, Zhang W, Yu S and

Guan R: Progress on Three-dimensional cell culture technology and

their application. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi.

40:602–608. 2023.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sugimoto M, Kitagawa Y, Yamada M, Yajima

Y, Utoh R and Seki M: Micropassage-embedding composite hydrogel

fibers enable quantitative evaluation of cancer cell invasion under

3D coculture conditions. Lab Chip. 18:1378–1387. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang T, Zhang KN and Ke CX: Research

progress of three-dimensional cell culture in bladder cancer. J Med

Res. 50:16–18. 2021.

|

|

7

|

Zhang C, Yang Z, Dong DL, Jang TS, Knowles

JC, Kim HW, Jin GZ and Xuan Y: 3D culture technologies of cancer

stem cells: Promising ex vivo tumor models. J Tissue Eng.

11:20417314209334072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jovanović Stojanov S, Grozdanić M, Ljujić

M, Dragičević S, Dragoj M and Dinić J: Cancer 3D Models: Essential

tools for understanding and overcoming drug resistance. Oncol Res.

33:2741–2785. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lonkwic KM, Zajdel R and Kaczka K:

Unlocking the potential of spheroids in personalized medicine: A

systematic review of seeding methodologies. Int J Mol Sci.

26:64782025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kaur N, Savitsky MJ, Scutte A, Mehta R,

Dridi N, Sogbesan T, Savannah A, Lopez D, Yang D and Ali J:

Navigating cancer treatment: A journey from 2D to 3D cancer models

and nanoscale therapies. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 8:3773–3800.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Abuwatfa WH, Pitt WG and Husseini GA:

Scaffold-based 3D cell culture models in cancer research. J Biomed

Sci. 31:72024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang X, Kawazoe N and Chen G: Interaction

of immune cells and tumor cells in gold nanorod-gelatin composite

porous scaffolds. Nanomaterials (Basel). 9:13672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang X, Zhang J, Li J, Chen Y, Kawazoe N

and Chen G: Bifunctional scaffolds for the photothermal therapy of

breast tumor cells and adipose tissue regeneration. J Mater Chem B.

6:7728–7736. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Alafnan A, Seetharam AA, Hussain T, Gupta

MS, Rizvi SMD, Moin A, Alamri A, Unnisa A, Awadelkareem AM,

Elkhalifa AO, et al: Development and characterization of PEGDA

microneedles for localized drug delivery of gemcitabine to treat

inflammatory breast cancer. Materials (Basel). 15:76932022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bai G, Yuan P, Cai B, Qiu X, Jin R, Liu S,

Li Y and Chen X: Stimuli-responsive scaffold for breast cancer

treatment combining accurate photothermal therapy and adipose

tissue regeneration. Adv Funct Mater. 29:19044012019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Dettin M, Sieni E, Zamuner A, Marino R,

Sgarbossa P, Lucibello M, Tosi AL, Keller F, Campana LG and Signori

E: A Novel 3D scaffold for cell growth to asses electroporation

efficacy. Cells. 8:14702019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fang Z, Chen L, Moser MA, Zhang W, Qin Z

and Zhang B: Electroporation-based therapy for brain tumors: A

review. J Biomech Eng. 143:1008022021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lou J and Mooney DJ: Chemical strategies

to engineer hydrogels for cell culture. Nat Rev Chem. 6:726–744.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Radulescu DM, Neacsu IA, Grumezescu AM and

Andronescu E: New insights of scaffolds based on hydrogels in

tissue engineering. Polymers (Basel). 14:7992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang C, Ye X, Zhao Y, Bai L, He Z, Tong Q,

Xie X, Zhu H, Cai D, Zhou Y, et al: Cryogenic 3D printing of porous

scaffolds for in situ delivery of 2D black phosphorus nanosheets,

doxorubicin hydrochloride and osteogenic peptide for treating tumor

resection-induced bone defects. Biofabrication. 12:0350042020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang X, Wang Y, Mao T, Wang Y, Liu R, Yu L

and Ding J: An oxygen-enriched thermosensitive hydrogel for the

relief of a hypoxic tumor microenvironment and enhancement of

radiotherapy. Biomater Sci. 9:7471–7482. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang A, Bai Y, Dong X, Ma T, Zhu D, Mei L

and Lv F: Hydrogel/nanoadjuvant-mediated combined cell vaccines for

cancer immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 133:257–267. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fu SJ, Liu XX, Hu MB, Li CJ, Wang FJ and

Wang L: Preparation and characterization of fiber-hydrogel

composite scaffolds for three-dimensional culture of breast

tumorcells. J Donghua Univ (Nat Sci). 50:11–19. 2024.

|

|

24

|

Quazi MZ and Park N: DNA Hydrogel-based

nanocomplexes with Cancer-targeted delivery and Light-triggered

peptide drug release for Cancer-specific therapeutics.

Biomacromolecules. 24:2127–2137. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang R, Huang J, Sun X, Chu X, Wang F,

Zhou J, Fan Q and Pang L: Construction of in vitro 3-D model for

lung cancer-cell metastasis study. BMC Cancer. 22:4382022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yao J, Li J, Du G and Zhao JM: Effect of

nano-microporous polycaprolactone combined with bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells on cartilage injury in rabbits. Guangdong

Med J. 35:3307–3309. 2014.

|

|

27

|

Mahendiran B, Muthusamy S, Selvakumar R,

Rajeswaran N, Sampath S, Jaisankar SN and Krishnakumar GS:

Decellularized natural 3D cellulose scaffold derived from Borassus

flabellifer (Linn.) as extracellular matrix for tissue engineering

applications. Carbohydr Polym. 272:1184942021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nemati M, Bani F, Sepasi T, Zamiri RE,

Rasmi Y, Kahroba H, Rahbarghazi R, Sadeghi MR, Wang Y, Zarebkohan A

and Gao H: Unraveling the effect of breast cancer patients' plasma

on the targeting ability of folic acid-modified chitosan

nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 18:4341–4353. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tian XH: Preparation of pH-responsive

Chitosan Anticancer Drug Carriers and Their Application. Jinzhou

Medical University; 2019

|

|

30

|

De Araújo JT, Tavares Junior AG, Di

Filippo LD, Duarte JL, Ribeiro TD and Chorilli M: Overview of

chitosan-based nanosystems for prostate cancer therapy. Eur Polymer

J. 160:1108122021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Pham DT, Saelim N and Tiyaboonchai W:

Paclitaxel loaded EDC-crosslinked fibroin nanoparticles: A

potential approach for colon cancer treatment. Drug Deliv Transl

Res. 10:413–424. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chaicharoenaudomrung N, Kunhorm P,

Promjantuek W, Heebkaew N, Rujanapun N and Noisa P: Fabrication of

3D calcium-alginate scaffolds for human glioblastoma modeling and

anticancer drug response evaluation. J Cell Physiol.

234:20085–20097. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kim CJ, Terado T, Tambe Y, Mukaisho KI,

Sugihara H, Kawauchi A and Inoue H: Anti-oncogenic activities of

cyclin D1b siRNA on human bladder cancer cells via induction of

apoptosis and suppression of cancer cell stemness and invasiveness.

Int J Oncol. 52:231–240. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu C, Wang Z, Wei X, Chen B and Luo Y: 3D

printed hydrogel/PCL core/shell fiber scaffolds with NIR-triggered

drug release for cancer therapy and wound healing. Acta Biomater.

131:314–325. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Niculescu AG, Chircov C, Bîrcă AC and

Grumezescu AM: Fabrication and applications of microfluidic

devices: A review. Int J Mol Sci. 22:20112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Modena MM, Chawla K, Misun PM and

Hierlemann A: Smart cell culture systems: Integration of sensors

and actuators into microphysiological systems. ACS Chem Biol.

13:1767–1784. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Parihar A and Mehta PP: Lab-on-a-chip

devices for advanced biomedicines: Laboratory scale engineering to

clinical ecosystem. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2024, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hakim M, Khorasheh F, Alemzadeh I and

Vossoughi M: A new insight to deformability correlation of

circulating tumor cells with metastatic behavior by application of

a new deformability-based microfluidic chip. Anal Chim Acta.

1186:3391152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Matsuura-Sawada Y, Maeki M, Uno S, Wada K

and Tokeshi M: Controlling lamellarity and physicochemical

properties of liposomes prepared using a microfluidic device.

Biomater Sci. 11:2419–2426. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Xu Y, Chen B, He M, Cui Z and Hu B:

All-in-One microfluidic chip for online labeling, separating, and

focusing rare circulating tumor cells from blood samples followed

by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry detection. Anal

Chem. 95:14061–14067. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhu YH, Chen S, Zhang CF, Ikoma T, Guo HM,

Zhang XY, Li X and Chen W: Novel microsphere-packing synthesis,

microstructure, formation mechanism and in vitro biocompatibility

of porous gelatin/hydroxyapatite microsphere scaffolds. Ceramics

Int. 47:32187–32194. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Allu I, Sahi AK, Koppadi M, Gundu S and

Sionkowska A: Decellularization techniques for tissue engineering:

Towards replicating native extracellular matrix architecture in

liver regeneration. J Funct Biomater. 14:5182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Qiu H, Wang H, Yang X and Huo F: High

performance isolation of circulating tumor cells by acoustofluidic

chip coupled with ultrasonic concentrated energy transducer.

Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 222:1131382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hen SK and Jv XJ: Preparation of open

macroporous alginate microspheres for Three-dimensional cell

culture. Polymer Materials Sci Engine. 39:126–133. 2023.

|

|

45

|

Song JQ, Chen HL and Yang FW: Research and

Application of 3D Bioprinting Technology in Medical Field. Chin Med

Equipment. 36:151–165. 2021.

|

|

46

|

Liu P: Construction and Application of

3D-printed microfluidic chip cell analysis platform. Shandong

Normal University; 2023

|

|

47

|

Jin Y, Zhang J, Xing J, Li Y, Yang H,

Ouyang L, Fang ZY, Sun LJ, Jin B, et al: Multicellular 3D

bioprinted human gallbladder carcinoma forin vitromimicry of tumor

microenvironment and intratumoral heterogeneity. Biofabrication.

16:0450282024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mai P, Hampl J, Baca M, Brauer D, Singh S,

Weise F, Borowiec J, Schmidt A, Küstner JM, Klett M, et al:

MatriGrid® based biological morphologies: Tools for 3D

cell culturing. Bioengineering (Basel). 9:2202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jubelin C, Muñoz-Garcia J, Griscom L,

Cochonneau D, Ollivier E, Heymann MF, Vallette FM, Oliver L and

Heymann D: Three-dimensional in vitro culture models in oncology

research. Cell Biosci. 12:1552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ayvaz I, Sunay D, Sariyar E, Erdal E and

Karagonlar ZF: Three-dimensional cell culture models of

hepatocellular carcinoma-a review. J Gastrointest Cancer.

52:1294–1308. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

De Pieri A, Rochev Y and Zeugolis DI:

Scaffold-free cell-based tissue engineering therapies: Advances,

shortfalls and forecast. NPJ Regen Med. 6:182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Czaplinska D, Elingaard-Larsen LO, Rolver

MG, Severin M and Pedersen SF: 3D multicellular models to study the

regulation and roles of acid-base transporters in breast cancer.

Biochem Soc Trans. 47:1689–1700. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kelm JM, Timmins NE, Brown CJ, Fussenegger

M and Nielsen LK: Method for generation of homogeneous

multicellular tumor spheroids applicable to a wide variety of cell

types. Biotechnol Bioeng. 83:173–180. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Rodoplu D, Matahum JS and Hsu CH: A

microfluidic hanging drop-based spheroid co-culture platform for

probing tumor angiogenesis. Lab Chip. 22:1275–1285. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Safari F, Shakery T and Sayadamin N:

Evaluating the effect of secretome of human amniotic mesenchymal

stromal cells on apoptosis induction and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition inhibition in LNCaP prostate cancer cells based on 2D

and 3D cell culture models. Cell Biochem Funct. 39:813–820. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Heinrich MA, Huynh NT and Heinrich Prakash

J: Understanding glioblastoma stromal barriers against NK cell

attack using tri-culture 3D spheroid model. Heliyon. 10:e248082024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Bahmad HF, Cheaito K, Chalhoub RM, Hadadeh

O, Monzer A, Ballout F, EL-Hajj A, Mukherji D, Liu YN, Daoud G and

Abou-Kheir W: Sphere-formation assay: Three-dimensional in vitro

culturing of prostate cancer stem/progenitor sphere-forming cells.

Front Oncol. 8:3472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Ferreira SM: Effect of normal and tumor

extracellular matrix in cancer stem Cell-Like properties.

Universidade do Porto (Portugal); 2019

|

|

59

|

Xue W, Wang J, Hou Y, Wu D, Wang H, Jia Q,

Jiang Q, Wang Y, Song C, Wang Y, et al: Lung decellularized

matrix-derived 3D spheroids: Exploring silicosis through the impact

of the Nrf2/Bax pathway on myofibroblast dynamics. Heliyon.

10:e335852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sun B, Liang Z, Wang Y, Yu Y, Zhou X, Geng

X and Li B: A 3D spheroid model of quadruple cell co-culture with

improved liver functions for hepatotoxicity prediction. Toxicology.

505:1538292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang J, Kong Y and Deng FS: Enrichment of

pancreatic cancer stem cells by sphere-forming culture. Anhui Med

J. 40:1303–1305. 2019.

|

|

62

|

Raggi C, Taddei ML, Sacco E, Navari N,

Correnti M, Piombanti B, Pastore M, Campani C, Pranzini E, Iorio J,

et al: Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism contributes to a cancer

stem cell phenotype in cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 74:1373–1385.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Topal U and Zamur C: Microgravity, stem

cells, and cancer: A new hope for cancer treatment. Stem Cells Int.

2021:55668722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kumar V, Sethi B, Staller DW, Shrestha P

and Mahato RI: Gemcitabine elaidate and ONC201 combination therapy

for inhibiting pancreatic cancer in a KRAS mutated syngeneic mouse

model. Cell Death Discov. 10:1582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Belloni D, Ferrarini M, Ferrero E,

Guzzeloni V, Barbaglio F, Ghia P and Scielzo C: Protocol for

generation of 3D bone marrow surrogate microenvironments in a

rotary cell culture system. STAR Protoc. 3:1016012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Naser Al Deen N, Atallah Lanman N,

Chittiboyina S, Lelièvre S, Nasr R, Nassar F, Dohna H, AbouHaidar M

and Talhouk R: A risk progression breast epithelial 3D culture

model reveals Cx43/hsa_circ_0077755/miR-182 as a biomarker axis for

heightened risk of breast cancer initiation. Sci Rep. 11:26262021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Malhão F, Macedo AC, Ramos AA and Rocha E:

Morphometrical, morphological, and immunocytochemical

characterization of a tool for cytotoxicity research: 3D cultures

of breast cell lines grown in Ultra-low attachment plates. Toxics.

10:4152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Yang JY, Liu D, Li L, Li DH and Wang HF:

Effect of propofol on pyroptosis of lung cancer A549 cells by

NLRP3/ASC/caspase-1 pathway. J China Med Univ. 53:132–141.

2024.

|

|

69

|

Du M, Liu ZJ, Zou F, Cai HH, Li JY and

Zhou BMJ: Effect of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell

supernatant on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma spheres. Chin J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 31:634–637. 2022.

|

|

70

|

Liu B, Han S, Modarres-Sadeghi Y and Lynch

ME: Multiphysics simulation of a compression-perfusion combined

bioreactor to predict the mechanical microenvironment during bone

metastatic breast cancer loading experiments. Biotechnol Bioeng.

118:1779–1792. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Calamak S, Ermis M, Sun H, Islam S, Sikora

M, Nguyen M, Hasirci V and Steinmetz LM: A circulating bioreactor

reprograms cancer cells toward a more mesenchymal niche. Adv

Biosyst. 4:e19001392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Huo Z, Bilang R, Supuran CT, von der Weid

N, Bruder E, Holland-Cunz S, Martin I, Muraro MG and Gros SJ:

Perfusion-based bioreactor culture and isothermal microcalorimetry

for preclinical drug testing with the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor

SLC-0111 in Patient-derived neuroblastoma. Int J Mol Sci.

23:31282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Bober Z, Podgórski R, Aebisher D, Cieślar

G, Kawczyk-Krupka A and Bartusik-Aebisher D: Cellular 1H MR

relaxation times in healthy and cancer Three-dimensional (3D)

breast cell culture. Int J Mol Sci. 24:47352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Anil-Inevi M, Yilmaz E, Sarigil O, Tekin

HC and Ozcivici E: Single cell densitometry and weightlessness