Introduction

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), also known as

cylindroma, is a rare malignant tumour that accounts for 1% of all

head and neck cancer (HNSC) and 10% of salivary gland malignancies

(1). Salivary glands are the most

common site of ACC, but tumours may also occur in the lacrimal

glands (2), breast (3), nasal cavity and paranasal sinus

(4) vulva (5) and skin (6). ACC occurring in the vulvar region

predominantly arises from the Bartholin's gland. Although

characterized by indolent growth, this malignancy commonly exhibits

perineural invasion (7). The age of

onset is between 18 and 90 years; however, no notable differences

have been identified between the sexes (8,9). At

present, the common treatment is surgery with or without

radiotherapy, as no approved systemic therapy exists. ACC of the

head and neck progresses relatively slowly and indolently,

resulting in 5- and 10-year patient survival rates of ~85 and 67%,

respectively (8). However,

long-term outcomes have revealed a decline in the 20-year overall

survival rate of ~20% (10), which

is primarily associated with nerve invasion, local control failure

and distant metastasis (11). Due

to the complexity of its clinical biological behaviour and the

challenges in clinical treatment, ACC requires further

investigation.

NDC80 kinetochore complex component (NUF2) is the

gene encoding the protein cell division cycle associated 1, which

serves a key role in ensuring proper chromosomal segregation and is

a key component of the NDC80/NUF2 complex (12,13).

Previous studies have reported that the expression level of the

NUF2 gene increases in various cancer tissues and it is closely

associated with tumorigenesis and progression, including

hepatocellular carcinoma, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, gastric

and breast cancer (13–17). It has been reported that in ovarian

cancer, lung adenocarcinoma and breast cancer, downregulating the

expression level of the NUF2 gene not only inhibits cell

proliferation and colony formation, but also promotes apoptosis

(18–20). These studies support the possible

role of NUF2 in tumorigenesis.

Collectively, the high recurrence rate (50%)

(21) and distant metastasis of ACC

underscore the need for novel molecular targets. The established

role of NUF2 in proliferation and migration positions it as a

plausible contributor to ACC aggressiveness. However, to the best

of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the function of NUF2

in ACC, leaving its therapeutic potential unexplored. Therefore,

the aim of the present study was to screen the hub genes

distinguishing ACC from normal tissues by the application of

bioinformatics techniques. The present study identified the key

role of NUF2 in ACC by analysing public datasets and further

validated these findings using functional experiments.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

ACC tissues and paired adjacent normal tissue

samples were obtained from patients with ACC undergoing surgery at

Suzhou Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing

University (Suzhou, China) between October 2021 and December 2024

for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and western blotting analysis. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Age, 18–80 years; ii)

postoperative pathological confirmation of adenoid cystic

carcinoma; and iii) availability of complete clinical data. The

exclusion criterion was a history of prior radiotherapy or

chemotherapy. Due to the low incidence of ACC at Suzhou Hospital,

Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, only 2

patients met the inclusion criteria during the present study

period. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Suzhou Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing

University (approval no. IRB2020094; Suzhou, China). Included

patients signed a consent form that authorized the use of their

tissues in the present study.

ACC dataset

In the present study, datasets were obtained from

the GEO data repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The GSE88804

dataset contained 13 surgical samples of ACC with 7 normal samples

(22). The GSE153002 dataset was

composed of 30 ACC samples and 7 normal samples (23). The GSE36820 dataset included 11 ACC

samples and 3 normal samples (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE36820).

The GSE88804 and GSE153002 datasets were merged and normalized

utilizing the ‘sva’ R package (version no. 3.58.0; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/sva.html;

R Development Core Team; Bioconductor) and the normalized data were

used for subsequent study. The GSE36820 dataset was utilized for

verification.

Differentially expressed genes

(DEGs)

The R package ‘limma’ (version 3.58.1; https://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/limma/; R Development

Core Team; Bioconductor) was used for the merged dataset. The

fold-change (FC) was calculated using false discovery and the

Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to adjust the original P-values

(24). Based on adjusted P<0.05

and log2FC >1, the present study identified the DEGs

in the merged dataset with the ‘limma’ package. Subsequently, a

volcano plot and heatmap were generated to visualize the

results.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network construction and hub gene exploration

The Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting

Genes/Proteins (STRING) database (https://cn.string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=bXmYsv7CnUrH&input_page_active_form=multiple_identifiers)

displayed the relationships between proteins in the form of network

graphs. In the present study, the DEGs were uploaded to the STRING

website to construct a PPI network for the prediction of vital

genes with a confidence score >0.4 and the organism was set to

Homo sapiens. The network data were exported and imported to

Cytoscape software (version 3.9.0) for analysis and visualization

of the molecular interaction diagrams. Subsequently, ‘cytoHubba’, a

plugin tool in Cytoscape (25), was

used to separately identify the first hub genes based on three

topological analysis methods, including degree, maximum clique

centrality (MCC) and maximum network connectivity (MNC). The

intersection of these genes were subsequently visualized.

Expression and validation analysis of

NUF2

Tumour Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) 2.0 is a

database that utilizes RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) expression profile

data to analyse differential gene expression in tumours (http://timer.cistrome.org/). The differences in NUF2

expression between normal and cancer tissues in different cancer

types were determined using the TIMER 2.0 database (26). In the present study, NUF2 was

inputted into the ‘Gene_DE’ module (https://compbio.cn/timer2/) of the TIMER 2.0 database

and the difference in NUF2 expression between normal and cancer

tissues from different tumours in The Cancer Genome Atlas database

was analysed (27).

The present study used box plots to depict the

differential expression level of NUF2 in normal and tumour tissues

using the combined dataset, after which the present study validated

the differential expression level of NUF2 in the GSE36820

dataset.

Functional enrichment analysis

Based on the median expression levels of NUF2 in

tumour tissues, the two groups were divided into high- and

low-expression groups and the differences were analysed using the

‘limma’ package. LogFC >1 and adjusted P<0.05 were set as the

cut-off point for the DEGs. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis

of the DEGs was performed with the ‘ClusterProfiler’ (version

4.10.0; http://yulab-smu.top/biomedical-knowledge-mining-book/)

and ‘org.Hs.eg.db’ (version 3.22; http://bioconductor.org/packages/org.Hs.eg.db)

package. Subsequently, the results were visualized using a bubble

diagram.

Immune infiltration analysis

TIMER is a web server used to analyse the level of

immune infiltration in different cancer types. In the TIMER

database, specific algorithms were used to analyse the immune

infiltration level. In the present study, the relationship between

NUF2 and immune cells in HNSC was discussed.

To assess differences in immune cell infiltration,

single sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) was performed

on RNA-seq data from the NUF2 high- and low-expression groups.

IHC

The tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral

formalin at room temperature for 24 h. IHC staining was performed

on 4-µm-thick paraffin-embedded tissue sections. The sections were

deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using a graded ethanol

series to water. Antigen retrieval was carried out in citrate

buffer (pH 6.0) at 121°C for 120 sec using a pressure cooker. To

quench endogenous peroxidase activity, the sections were incubated

in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution protected from light for 25 min at

room temperature. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with

rabbit serum (concentrated; cat. no. G1209; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at room temperature. The sections

were then incubated with primary antibody [rabbit polyclonal

antibodies against NUF2 (1:500; cat. no. 15731-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.)] overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber.

Subsequently, the sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 50 min.

Colour development was performed using a DAB substrate kit

according to the manufacturer's instructions (cat. no. G1212; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature, followed by

counterstaining with haematoxylin for ~3 min. Lastly, the stained

sections were imaged under a light microscope. Each section was

evaluated by two blinded, independent pathologists. Discrepancies

between the two pathologists were resolved by a joint re-evaluation

and discussion until a consensus was reached. The percentages of

positive tumour cells were as follows: i) 1–25%; ii) 26–50%; iii)

51–75%; and iv) 76–100%. The immunoreaction intensity was

classified as 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), 3 (strong). The

final staining scores were calculated as the sum of the intensity

and positive rates scores and was graded as follows: 0 score,

negative (−); 1–3 scores, weakly positive (+); 4–5 scores, moderate

positive (++) or 6–7 scores, strongly positive (+++) (28).

Western blotting analysis

Proteins were isolated from human ACC tissues and

paired adjacent normal tissues using RIPA buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The protein concentration was

determined by the BCA method. Subsequently, 30 µg of protein was

loaded onto an 10% SDS-PAGE gel and then transferred to PVDF

membranes. The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% milk at room

temperature for 1 h and then incubated with the primary antibody

against NUF2 (1:800; cat. no. 15731-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

and GAPDH (1:10,000; cat. no. 10494-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS-0.1% Tween 20, the

membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (HRP-conjugated

Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG; 1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature. Lastly, the bands were

detected using an ECL substrate (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions and an

Amersham™ Imager 680 system (Cytiva).

Cell culture

The human salivary ACC (SACC)-83 cell line (cat. No.

FH0798; http://www.fudancell.com/sys-pd/?pid=3836) was

purchased from Shanghai Fuheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The SACC-83

cell line was cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and

10% FBS (cat. no. FH100-900; Shanghai Fuheng Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) and

transfection

siRNAs targeting human the NUF2 gene and negative

control siRNA (si-NC) were purchased from Guangzhou RiboBio Co.,

Ltd. SACC-83 cells were transfected with si-NC (cat. no.

siN0000001-1-5) or siNUF2 (Table

SI) using Lipofectamine® 3000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The

cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of

2×105 cells/well before transfection and cultured until

they reached a confluency of 60–70%. Transfected cells were

incubated at 37°C for 72 h and then were collected for Cell

Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay and wound healing assay.

CCK-8

After 72 h target gene suppression, the cells were

seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1.5×103

cells/well. A control group cultured with medium alone was

established in parallel. At 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, 10 µl of CCK-8

solution (MedChemExpress) was added to each well under

light-protected conditions. After a 2 h incubation, the absorbance

at 450 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer (Tecan

Biotechnology).

Wound healing assay

SACC-83 cells transfected with NUF2 siRNA were

seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1.5×105

cells/well and cultured overnight to reach 80–90% confluence.

Linear wounds were generated using a 1,000 µl pipette tip held

orthogonal to the plate surface. After the cells were washed with

post-scratch PBS, cellular debris was removed and 2 ml of

serum-free RPMI-1640 was added to mitigate the effects on

proliferation. Cell migration was observed under an inverted

microscope at 0 and 24 h post-culture. Quantification was conducted

using ImageJ software. The wound area at 0 and 24 h was first

measured, after which the wound closure rate was calculated. Wound

closure was defined as the percentage reduction in wound area at 24

h relative to the initial wound area at 0 h. Each group included

three independent biological replicates, and all data were

presented as mean ± SD.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate immune infiltrates, TIMER 2.0 employs

partial Spearman's correlation, controlling for tumour purity, to

assess the association between the estimated levels of immune

infiltration and NUF2 expression. Data obtained from the CCK-8

assay were analysed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni

post-hoc test. The wound healing assay was analysed using an

unpaired t-test. All statistical tests were two-tailed. CCK-8 and

wound healing assay were performed in triplicate. The efficiency of

NUF2 knockdown by each specific siRNA (si-1, si-2, and si-3) was

evaluated via Western blot. Quantitative data were compared to the

negative control group (si-NC) using one-way ANOVA, followed by the

Bonferroni post-hoc test. Statistical analyses were performed with

GraphPad Prism (version 10; Dotmatics). For comparisons between two

groups of independent samples, such as tumour samples vs. normal

control samples from different individuals in the GEO datasets, the

Mann-Whitney U test was used. For comparisons involving paired

samples with sufficient sample size (n≥5), the Wilcoxon signed-rank

test was employed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Screening of DEGs

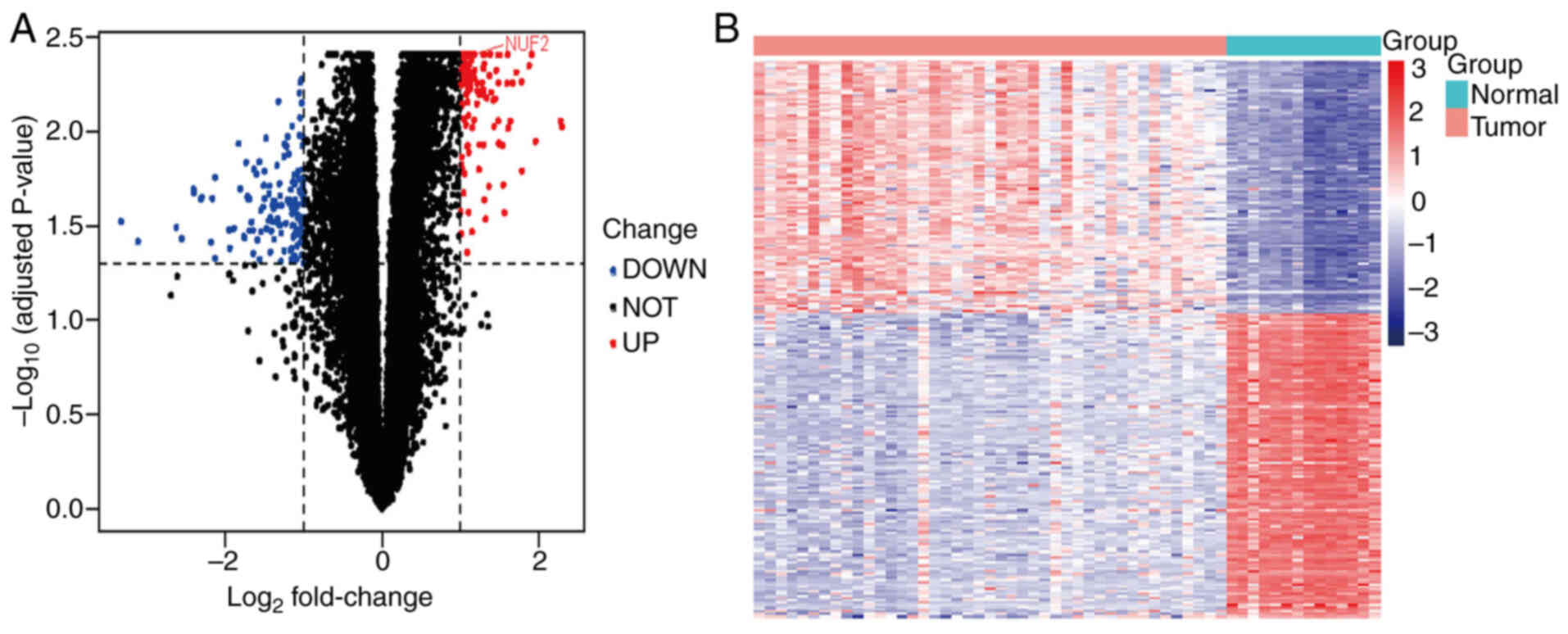

In the present study, three gene expression

datasets, GSE88804, GSE153002 and GSE36820, were downloaded from

the GEO database. A total of 54 ACC with 17 normal salivary gland

tissues data were obtained. In the merged GSE88804 and GSE153002

datasets, the present study applied the rectified data for

differential expression analysis and obtained 248 DEGs, including

113 upregulated genes and 135 downregulated genes (Fig. 1A and B).

PPI network and module analysis

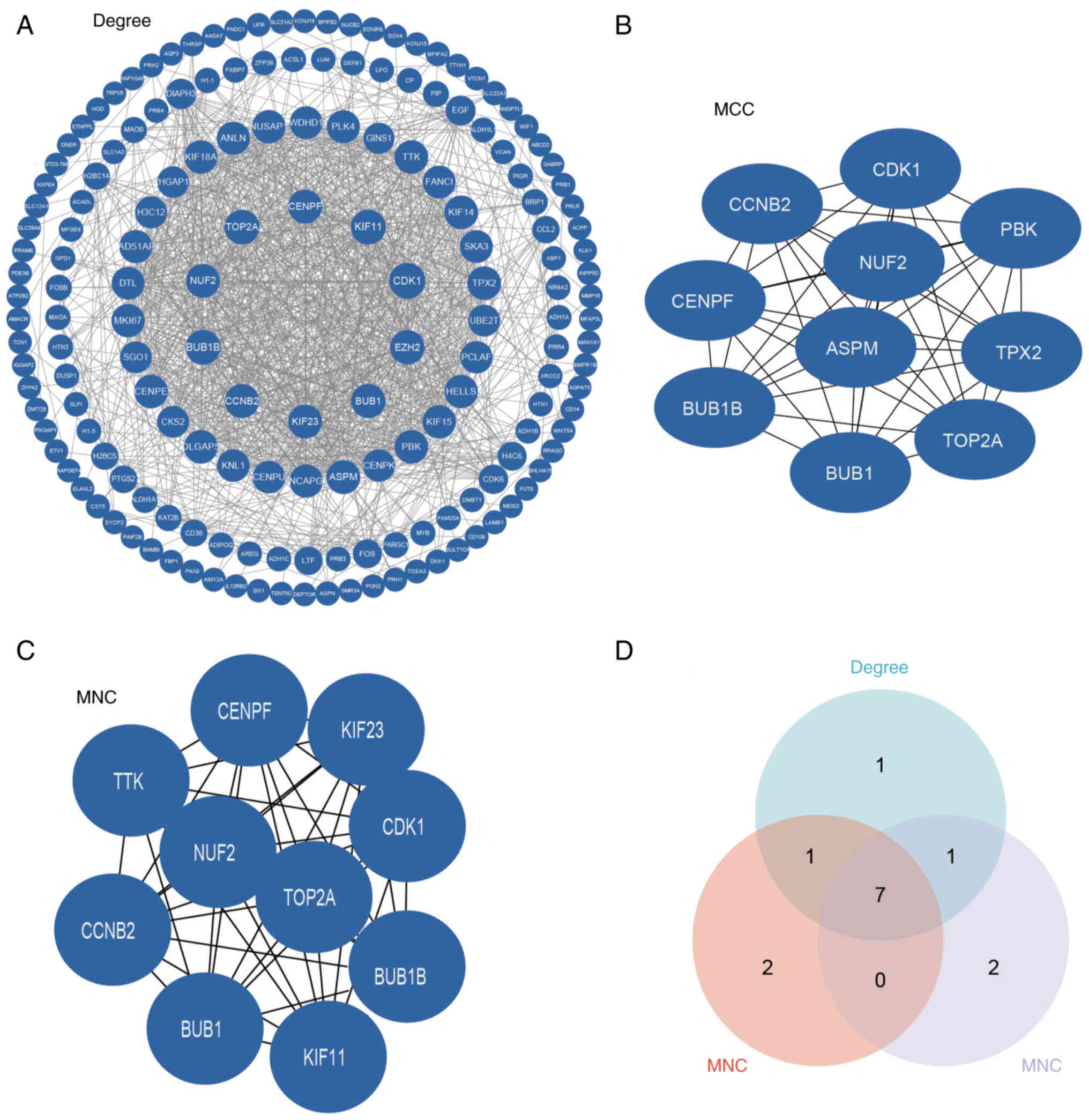

To identify functionally pivotal interactions, an

established DEG-associated PPI network was constructed using the

STRING database and analysed using Cytoscape software. Based on

network degree centrality analysis, the present study identified

the top 10 hub genes with the highest connectivity for further

investigation (Fig. 2A).

Subsequently, the present study implemented the MCC and MNC

algorithms to enhance the robustness of hub gene identification.

The top 10 highest-scoring genes from each method were obtained

(Fig. 2B and C). To identify key

genes, the present study first selected the top 10 candidates from

each method (degree, MCC and MNC) and then performed intersection

analysis to identify seven high-confidence hub genes (CDK1, budding

uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine

kinase B, DNA topoisomerase II α, cyclin B2, NUF2, budding

uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 and centromere protein F; Fig. 2D). The role of NUF2 in ACC remains

unexplored; a PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) search using the

keywords ‘NUF2’ and ‘adenoid cystic carcinoma’ yielded no relevant

publications.

Expression and verification of

NUF2

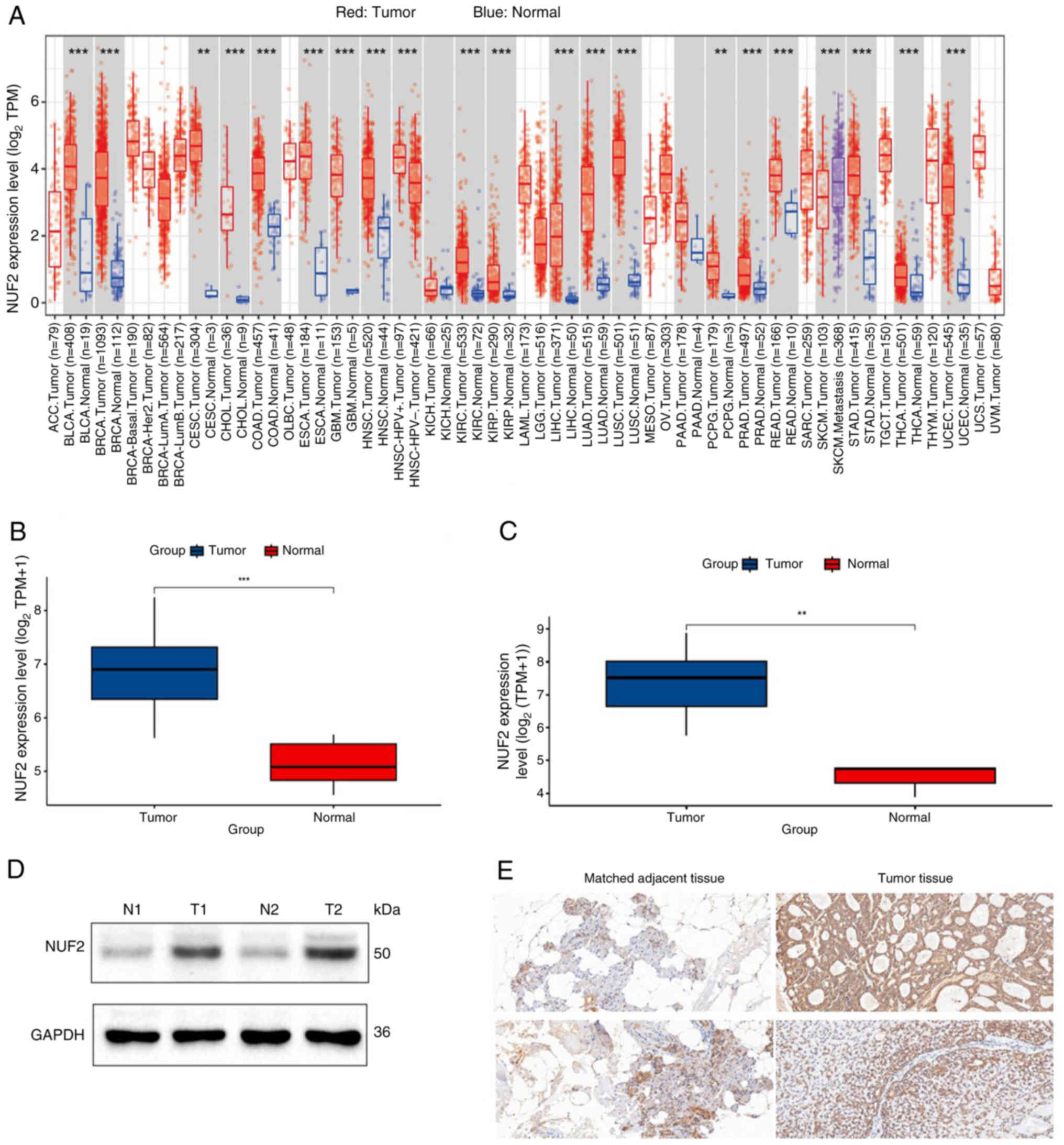

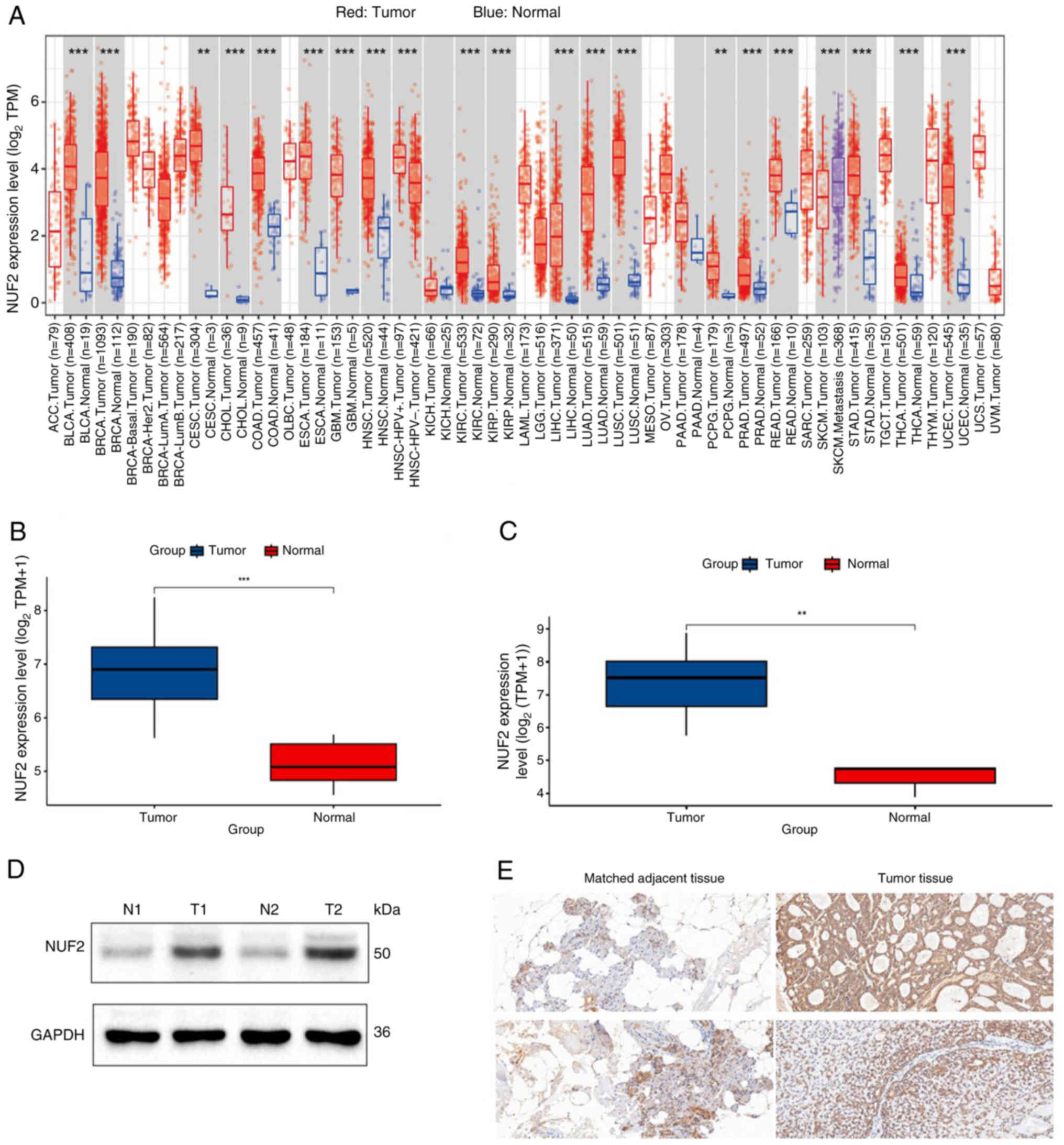

Analysis of the TIMER database using the ‘Gene_DE’

module demonstrated that NUF2 was significantly highly upregulated

in a variety of tumours compared with normal tissues, such as liver

hepatocellular carcinoma, oesophageal carcinoma, stomach

adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma multiforme, breast invasive carcinoma

and colon adenocarcinoma (P<0.001; Fig. 3A). In the combined and standardized

datasets (GSE88804 and GSE153002), the expression levels of NUF2

were also significantly higher in tumour tissue samples compared

with normal tissue samples (P<0.001; Fig. 3B). Similarly, NUF2 expression was

significantly upregulated in ACC within the GSE36820 validation set

(P<0.01; Fig. 3C). These results

were also supported by western blotting analysis, which revealed a

marked increase in NUF2 protein levels in ACC tissues (Fig. 3D). IHC analysis of a preliminary set

of paired samples (n=2) showed a trend of higher NUF2 expression in

ACC tissues (IHC scores, 6 and 6) compared with their matched

adjacent tissues (IHC scores, 3 and 4) (Fig. 3E).

| Figure 3.Expression level of NUF2 and

immunohistochemistry. (A) Expression levels of NUF2 were analysed

with the TIMER database. (B) Expression levels of NUF2 were

verified with a merged dataset (GSE88804 and GSE153002). (C)

Expression levels of NUF2 were verified by the GSE36820 dataset.

(D) Expression levels of NUF2 in two ACC tissues and adjacent

normal tissues assessed using western blotting. (E)

Immunohistochemical staining results demonstrated that both tumour

tissue samples received a final score of 6, indicating strong NUF2

expression. By contrast, the matched adjacent tissues demonstrated

lower expression levels, with the upper adjacent tissue scoring 3

and the lower adjacent tissue scoring 4. Magnification, ×200.

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. siRNA, small interfering RNA; NUF2,

NDC80 kinetochore complex component; TIMER, Tumour Immune

Estimation Resource; GSE, Gene Set Enrichment; ACC, adenoid cystic

carcinoma; TPM, transcripts per million; N, normal; T, tumour. |

GO enrichment analysis of DEGs

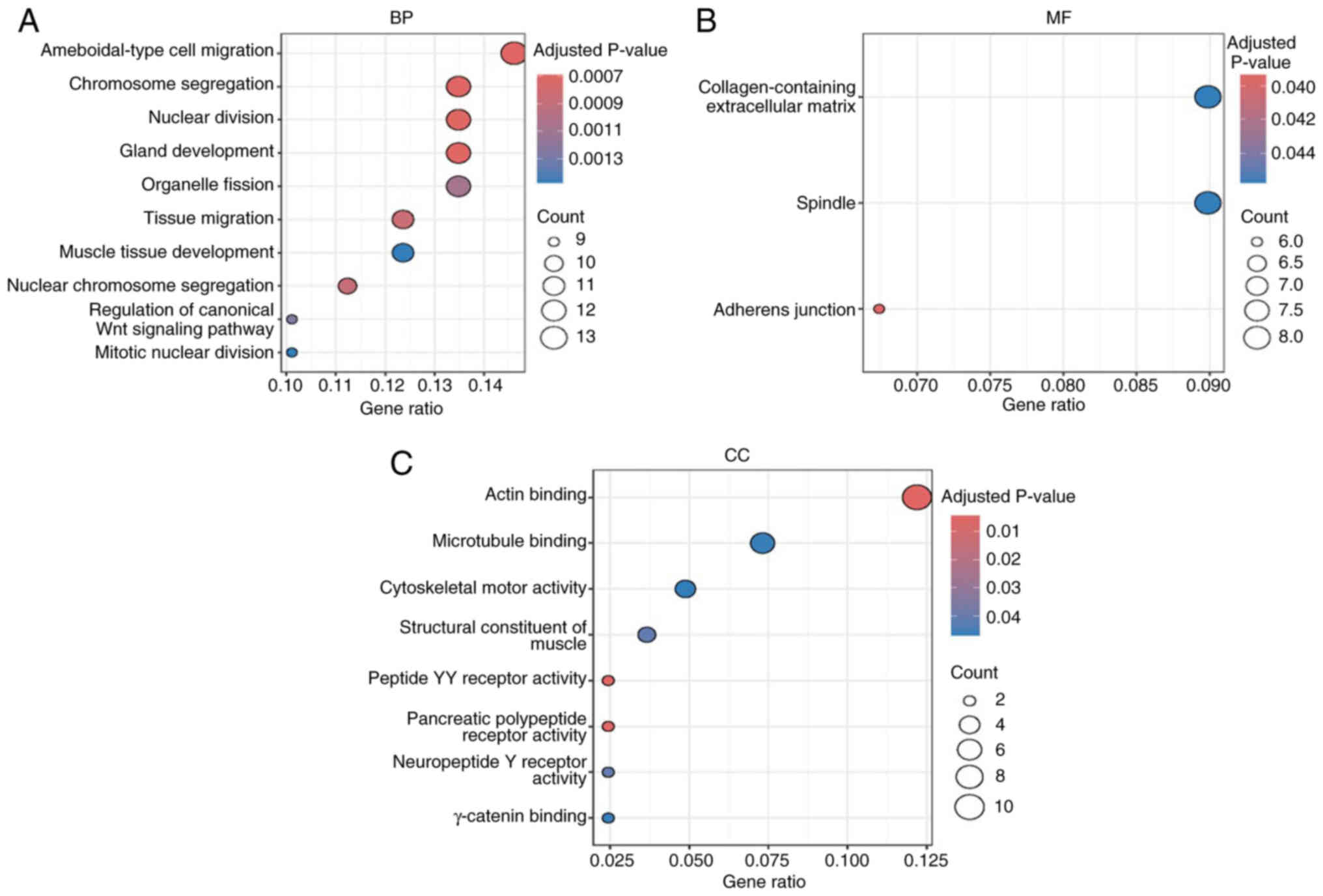

In the present study, NUF2-related genes were

significantly enriched in ‘ameboidal-type cell migration’,

‘chromosome segregation’, ‘nuclear division’ (P<0.01) in

biological processes and ‘collagen-containing extracellular matrix’

(P<0.05) in molecular functions and ‘actin binding’ (P<0.05)

in cellular components (Fig. 4A-C),

suggesting its potential role in ACC cell metastasis and

proliferation.

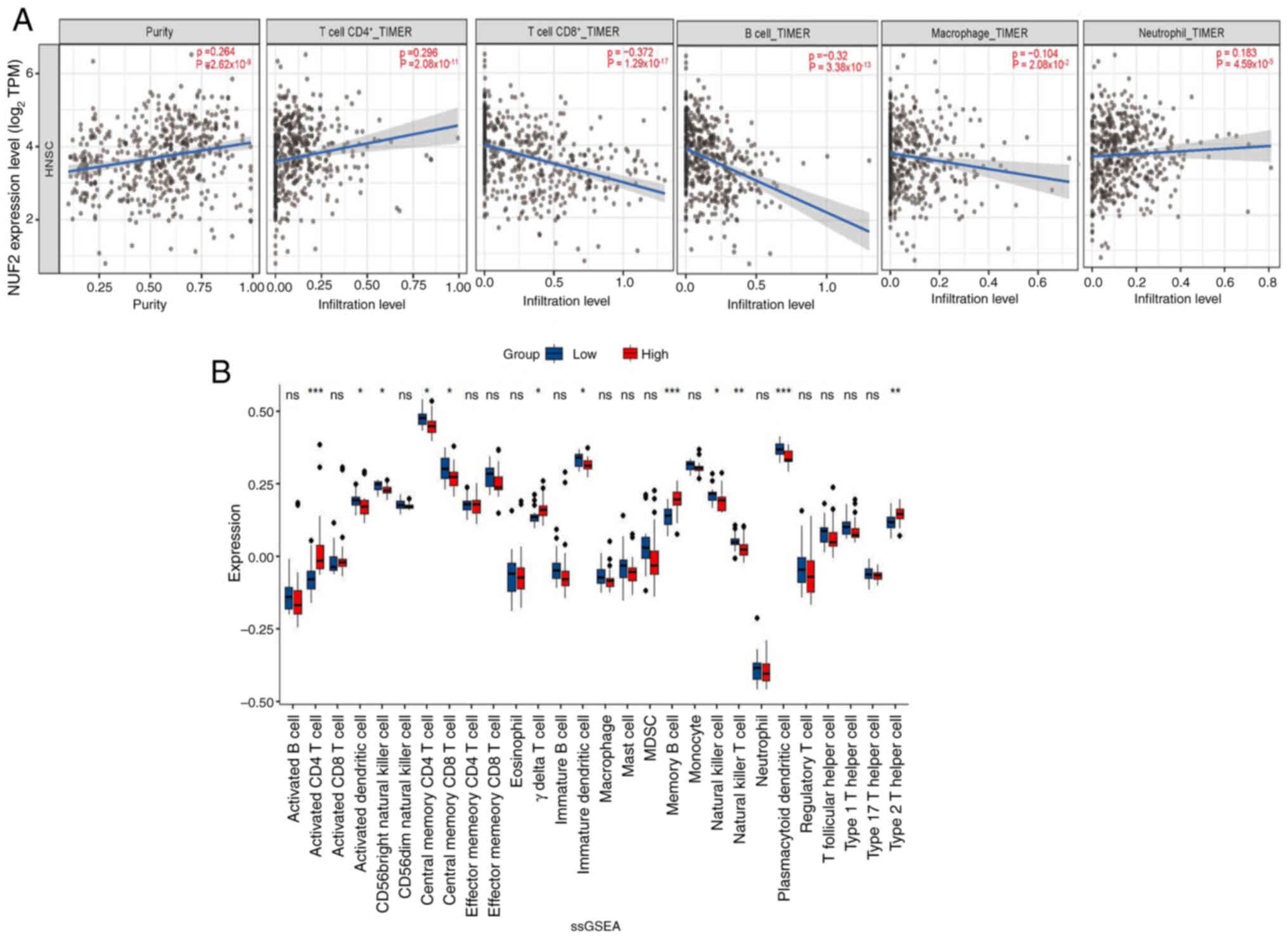

Correlations between immune cells and

the expression levels of NUF2 in ACC

To analyse the relationship between NUF2 expression

and the state of tumour-infiltrating immune cells, the TIMER

database was used to assess the association in HNSC tissues. The

present study identified that NUF2 expression showed a significant

but weak positive association with the infiltration levels of

CD4+ T cells (ρ=0.296; P=2.08×10−11),

neutrophils (ρ=0.183; P=4.59×10−05). By contrast, NUF2

expression was negatively correlated with the infiltration of

CD8+ T cells (ρ=−0.372; P=1.29×10−17) and B

cells (ρ=−0.32; P=3.38×10−13), with the correlation to

CD8+ T cells being moderate. Only a very weak negative association

was observed between NUF2 expression and macrophage infiltration

(ρ=−0.104; P=2.08×10−02; Fig. 5A).

Subsequently, ssGSEA was used to evaluate the

infiltration of 28 immune cells in each patient with ACC. The

results demonstrated that in the group with higher NUF2, activated

CD4+ T cells, γΔT cells, memory B cells and type 2 T

helper cells were significantly more abundant in infiltration

(P<0.05). The group with lower NUF2 expression demonstrated

significantly increased infiltration (P<0.05) of activated

dendritic cells, CD56 bright natural killer cells, central memory

CD4+ T cells, central memory CD8+ T cells,

immature dendritic cells, natural killer cells, natural killer T

cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (Fig. 5B).

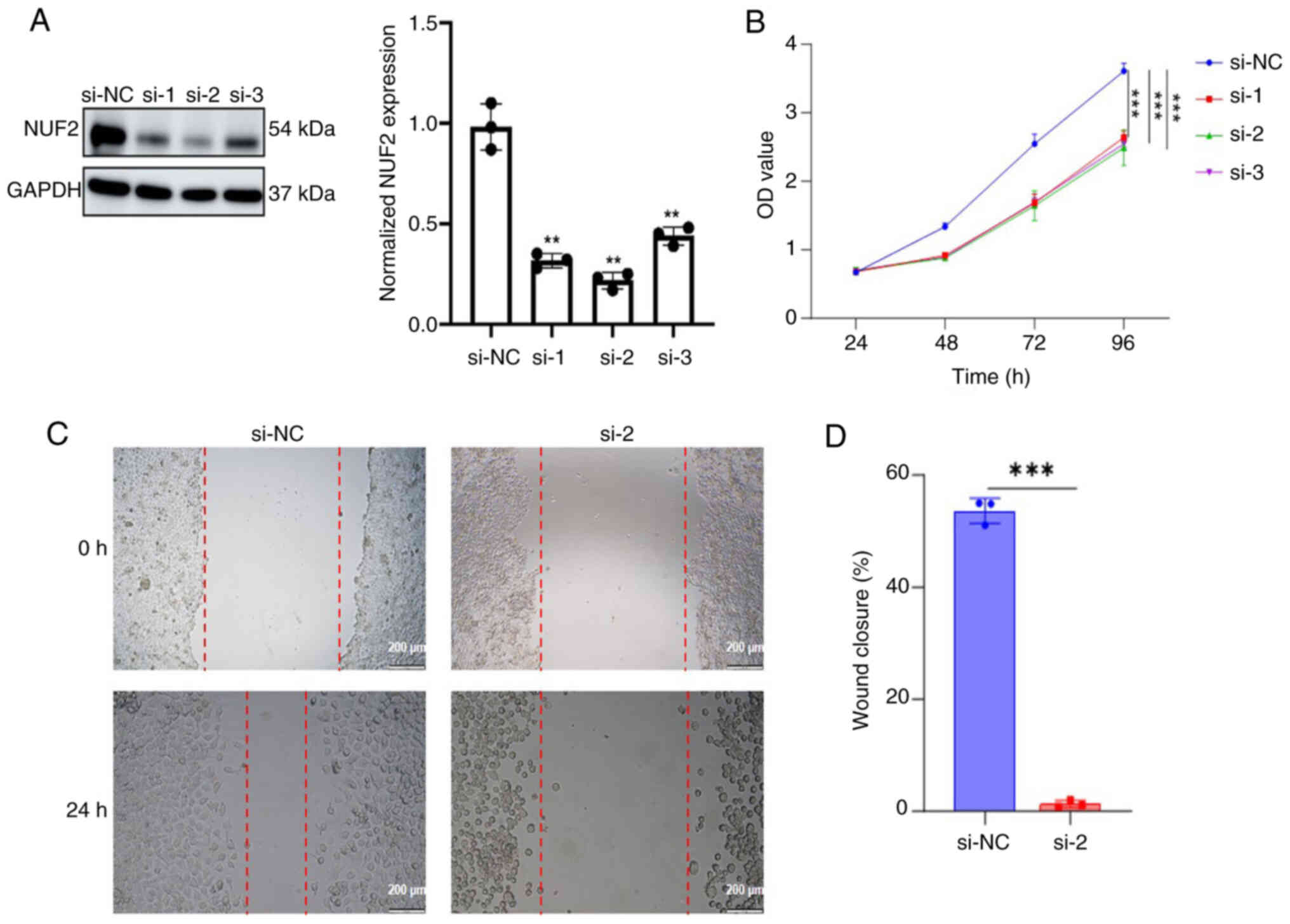

NUF2 promotes ACC cell proliferation

and migration in vitro

To assess the biological effect of NUF2 in ACC

cells, SACC-83 cells were transfected with siRNAs to silence NUF2

compared with the si-NC group. Western blotting was subsequently

used to evaluate the transfection efficiency. The siRNA with the

highest silencing efficiency, si-2, was selected for subsequent

functional studies (Fig. 6A).

In the present study, a CCK-8 assay was performed in

ACC cells. The downregulation of NUF2 expression significantly

inhibited (P<0.0001) the proliferation of ACC cells (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, the present study

explored the role of NUF2 in the migration of ACC cells using a

wound healing assay. The results revealed that knockdown of NUF2

significantly diminished (P=0.0004) the migration capacity of ACC

cells (Fig. 6C and D).

Discussion

As a result of the high risk of local recurrence and

delayed distant metastases, the treatment outcomes for ACC remain

suboptimal (29). Further research

on the molecular mechanisms of ACC may offer potentially effective

therapeutic strategies or promising biomarkers in the future.

However, the sensitivity and specificity of these methods are

limited. Increasing evidence suggests that NUF2 serves key roles in

the development and progression of several tumours, such as ovarian

cancer, multiple myeloma and hepatocellular carcinoma (20,30,31).

However, the role of NUF2 in ACC remains to be elucidated and

further research is warranted.

In the present study, the GEO database, western

blotting and IHC analysis were used for gene expression analysis.

The high expression level of NUF2 in tumour tissues and its low

expression in normal tissues are consistent with previous findings

(14,15,30).

Furthermore, several studies have reported that NUF2 upregulation

is associated with clinical stage and poor prognosis in

adrenocortical cancer, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, kidney

renal papillary cell carcinoma and multiple myeloma (30,31).

Fundamental research and clinical trials are needed to further

validate NUF2 as a therapeutic target in ACC.

Several studies have reported that targeted

regulation of NUF2 can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and

migration. Liu et al (32)

reported that silencing NUF2 expression could slow cell

proliferation in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Furthermore,

downregulation of NUF2 expression reduced the migratory ability of

lung adenocarcinoma cells (18),

which is consistent with the present study finding. In the present

study, the GO analysis results revealed that NUF2 is potentially

involved in regulating both proliferation and migration processes

in ACC.

Malignant tumours are composed of tumour cells,

immune cells and non-immune cells. Immune and non-immune cells

constitute the tumour microenvironment (TME), which includes

components such as fibroblasts, nerves, immune cells and various

cytokines and vascular systems (33). Increasing research has highlighted

the key role of the TME in the genesis and progression of several

malignancies such as laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, brain

metastasis (33–36) and liver cancer (37). Based on the status and distribution

of immune cells, tumours are categorized into three immune

phenotypes, including immune-desert (‘cold’ tumours),

immune-exclusive and immune inflammatory (‘hot’ tumours) (38). ‘Hot’ tumours are characterized by

abundant T-cell infiltration and exhibit good response to immune

checkpoint inhibitors (39).

Immunotherapy for numerous types of cancer has made notable

progress. Immunotherapy is now a main therapeutic choice for

advanced melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and renal cell carcinoma

and is regarded as a promising method for cancer therapy (40–42).

However, the expression levels of programmed death-ligand 1,

cytotoxic T-cell antigen 4 and programmed death receptor 1 are low

in the environment of ACC (43).

Furthermore, several studies on the use of immunotherapy in ACC

have reported unsatisfactory results (44,45).

Li et al (46) identified

that NUF2 is associated with the immune infiltration of certain

immune cells, such as CD8+ T Cells, B cells, natural

killer cells and neutrophils. and has a major function in the

regulation of cancer immunology. The present study results

regarding the immune microenvironment suggested that elevated NUF2

expression in ACC is correlated with the infiltration of activated

CD4+ T cells, memory B cells and type 2 T helper cells.

Further characterization indicated that high NUF2 expression was

associated with increased infiltration of activated CD4+

T cells, memory B cells and type 2 T helper cells, but decreased

infiltration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, activated dendritic

cells and natural killer T cells. These findings suggest that the

expression levels of NUF2 may influence the recruitment or activity

of immune cells within the TME.

The present study had certain limitations. First, a

notable limitation to consider is that HNSC and salivary gland

cancer are distinct pathological entities. Consequently,

extrapolating immune-related findings from this HNSCC cohort to ACC

should be interpreted with caution. Second, the observed

correlation between NUF2 expression and immune cell infiltration

was inferred solely using in silico analysis using the

ssGSEA algorithm. Immune correlations derived from bulk RNA-seq

data can be susceptible to confounding factors such as tumour

purity and stromal contamination (47). Additionally, the correlation

analyses between NUF2 and immune cells derived from the TIMER

database, particularly those involving CD4+ T cells,

neutrophils and macrophages, demonstrated weak associations, and

their biological relevance remains to be determined. Third, the

present study had a limited sample size. Therefore, to overcome

these constraints, the collection of additional ACC specimens and

the use of multiplex IHC coupled with flow cytometry in future

studies may be used to validate the present study findings.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, the

present study provides the first analysis of the expression pattern

of NUF2 in ACC. The present study results demonstrated that NUF2 is

upregulated in ACC compared with that of adjacent tissues and NUF2

expression is correlated with immune cell infiltration. These

findings may be potentially translated into effective clinical

interventions in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XY and LL conceived the present study and provided

financial support. SH, YL, JZ, JH and HC performed the experiments,

collected the data and prepared the figures. XY and LL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The collection of tumour samples and patient

information was approved by the Ethics Committee of Suzhou

Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University

(approval no. IRB2020094; Suzhou, China). All patients signed

informed consent for the retention and analysis of their tissues

for research purposes.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ,

Vander Poorten V, Triantafyllou A, Hunt JL, Strojan P, Rinaldo A,

Haigentz M Jr, Takes RP, et al: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the

head and neck-An update. Oral Oncol. 51:652–661. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Duarte AF, Alpuim Costa D, Cacador N,

Boavida AM, Afonso AM, Vilares M and Devoto M: Adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland-case report

and literature review. Orbit. 41:605–610. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gou WB, Yang YQ, Song BW and He P: Solid

basal adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast: A case report and

literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 103:e370102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lee TH, Kim K, Oh D, Yang K, Jeong HS,

Chung MK and Ahn YC: Clinical outcomes in adenoid cystic carcinoma

of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinus: A comparative analysis of

treatment modalities. Cancers (Basel). 16:12352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gural Z, Yucel S and Agaoglu F:

Bartholin's gland adenoid cystic carcinoma: Report of three cases

and the review of literature. Indian J Cancer. 61:346–349. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Schembri-Wismayer D, Gupta S and Erickson

LA: Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc.

99:1017–1018. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Baker GM, Selim MA and Hoang MP: Vulvar

adnexal lesions: A 32-year, single-institution review from

Massachusetts General Hospital. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 137:1237–1246.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Atallah S, Casiraghi O, Fakhry N, Wassef

M, Uro-Coste E, Espitalier F, Sudaka A, Kaminsky MC, Dakpe S, Digue

L, et al: A prospective multicentre REFCOR study of 470 cases of

head and neck Adenoid cystic carcinoma: Epidemiology and prognostic

factors. Eur J Cancer. 130:241–249. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

de Morais EF, da Silva LP, Moreira DGL,

Mafra RP, Rolim LSA, de Moura Santos E, de Souza LB and de Almeida

Freitas R: Prognostic factors and survival in adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the head and neck: A retrospective clinical and

histopathological analysis of patients seen at a cancer center.

Head Neck Pathol. 15:416–424. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dodd RL and Slevin NJ: Salivary gland

adenoid cystic carcinoma: A review of chemotherapy and molecular

therapies. Oral Oncol. 42:759–769. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ellington CL, Goodman M, Kono SA, Grist W,

Wadsworth T, Chen AY, Owonikoko T, Ramalingam S, Shin DM, Khuri FR,

et al: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: Incidence and

survival trends based on 1973–2007 surveillance, epidemiology, and

end results data. Cancer. 118:4444–4451. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nabetani A, Koujin T, Tsutsumi C,

Haraguchi T and Hiraoka Y: A conserved protein, Nuf2, is implicated

in connecting the centromere to the spindle during chromosome

segregation: A link between the kinetochore function and the

spindle checkpoint. Chromosoma. 110:322–334. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xie X, Jiang S and Li X: Nuf2 is a

prognostic-related biomarker and correlated with immune infiltrates

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 11:6213732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Jiang W, Chen Y,

Shan J, Li X and Wu X: NUF2 regulated the progression of

hepatocellular carcinoma through modulating the PI3K/AKT pathway

via stabilizing ERBB3. Transl Oncol. 44:1019332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zheng B, Wang S, Yuan X, Zhang J, Shen Z

and Ge C: NUF2 is correlated with a poor prognosis and immune

infiltration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Urol.

23:822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhu X, Zou Y, Wu T, Ni J, Tan Q, Wang Q

and Zhang M: ANP32E contributes to gastric cancer progression via

NUF2 upregulation. Mol Med Rep. 26:2752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhai X, Yang Z, Liu X, Dong Z and Zhou D:

Identification of NUF2 and FAM83D as potential biomarkers in

triple-negative breast cancer. PeerJ. 8:e99752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jiang F, Huang X, Yang X, Zhou H and Wang

Y: NUF2 expression promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression and is

associated with poor prognosis. Front Oncol. 12:7959712022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lv S, Xu W, Zhang Y, Zhang J and Dong X:

NUF2 as an anticancer therapeutic target and prognostic factor in

breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 57:1358–1367. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ren M, Zhao H, Gao Y, Chen Q, Zhao X and

Yue W: NUF2 promotes tumorigenesis by interacting with HNRNPA2B1

via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res.

16:172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yuce Sari S, Yazici G, Elmali A, Bayatfard

P, Koc I, Kiratli H and Cengiz M: Radiotherapy for adenoid cystic

carcinoma of the lacrimal gland: Study on twelve patients. Cancer

Radiother. 29:1046442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Andersson MK, Afshari MK, Andren Y, Wick

MJ and Stenman G: Targeting the oncogenic transcriptional regulator

MYB in adenoid cystic carcinoma by inhibition of IGF1R/AKT

signaling. J Natl Cancer Inst. 109:djx0172017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Persson M, Andersson MK, Sahlin PE, Mitani

Y, Brandwein-Weber MS, Frierson HF Jr, Moskaluk C, Fonseca I,

Ferrarotto R, Boecker W, et al: Comprehensive molecular

characterization of adenoid cystic carcinoma reveals tumor

suppressors as novel drivers and prognostic biomarkers. J Pathol.

261:256–268. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hochberg Y and Hochberg Y: Controlling the

false discovery rate a practical and powerful approach to multiple

testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B. 57:289–300. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT and

Lin CY: cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from

complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 8 (Suppl 4):S112014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:W509–W514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hutter C and Zenklusen JC: The cancer

genome atlas: Creating lasting value beyond its data. Cell.

173:283–285. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lin J, Chen X, Yu H, Min S, Chen Y, Li Z

and Xie X: NUF2 drives clear cell renal cell carcinoma by

activating HMGA2 transcription through KDM2A-mediated H3K36me2

demethylation. Int J Biol Sci. 18:3621–3635. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Stawarz K, Durzynska M, Galazka A,

Gorzelnik A, Zwolinski J, Paszkowska M, Bieńkowska-Pluta K and

Misiak-Galazka M: Current landscape and future directions of

therapeutic approaches for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary

glands (Review). Oncol Lett. 29:1532025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang Y, Chen L, Luo Y, Shen J and Zhou S:

Predictive value of NUF2 for prognosis and immunotherapy responses

in pan-cancer. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 45:137–149. 2025.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang S, Zhang L, Cai L, Chen H, Wang Y,

Yuan Y, Zhang H and Wei X: NUF2 overexpression predicts poor

outcomes in multiple myeloma. Genes Dis. 12:1012682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu Q, Dai SJ, Li H, Dong L and Peng YP:

Silencing of NUF2 inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis in

human hepatocellular carcinomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

15:8623–8629. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Elhanani O, Ben-Uri R and Keren L: Spatial

profiling technologies illuminate the tumor microenvironment.

Cancer Cell. 41:404–420. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan

V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI,

Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, et al: Understanding the tumor

immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med.

24:541–550. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rodrigo JP, Sanchez-Canteli M, Lopez F,

Wolf GT, Hernández-Prera JC, Williams MD, Willems SM, Franchi A,

Coca-Pelaz A and Ferlito A: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the

tumor microenvironment of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 9:4862021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

de Visser KE and Joyce JA: The evolving

tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic

outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41:374–403. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Affo S, Yu LX and Schwabe RF: The role of

cancer-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis in liver cancer. Annu

Rev Pathol. 12:153–186. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen DS and Mellman I: Elements of cancer

immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 541:321–330.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xu Q, Hu J, Wang Y and Wang Z: The role of

tumor types in immune-related adverse events. Clin Transl Oncol.

27:3247–3260. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Garg P, Pareek S, Kulkarni P, Horne D,

Salgia R and Singhal SS: Next-Generation immunotherapy: Advancing

clinical applications in cancer treatment. J Clin Med. 13:65372024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu B, Zhou H, Tan L, Siu KTH and Guan XY:

Exploring treatment options in cancer: Tumor treatment strategies.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:1752024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Waldman AD, Fritz JM and Lenardo MJ: A

guide to cancer immunotherapy: From T cell basic science to

clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol. 20:651–668. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wolkow N, Jakobiec FA, Afrogheh AH, Kidd

M, Eagle RC, Pai SI and Faquin WC: PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression

levels are low in primary and secondary adenoid cystic carcinomas

of the orbit: Therapeutic implications. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr

Surg. 36:444–450. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mosconi C, de Arruda JAA, de Farias ACR,

Oliveira GAQ, de Paula HM, Fonseca FP, Mesquita RA, Silva TA,

Mendonça EF and Batista AC: Immune microenvironment and evasion

mechanisms in adenoid cystic carcinomas of salivary glands. Oral

Oncol. 88:95–101. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sato R, Yamaki H, Komatsuda H, Wakisaka R,

Inoue T, Kumai T and Takahara M: Exploring immunological effects

and novel immune adjuvants in immunotherapy for salivary gland

cancers. Cancers (Basel). 16:12052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li X, Zhang L, Yi Z, Zhou J, Song W, Zhao

P, Wu J, Song J and Ni Q: NUF2 is a potential immunological and

prognostic marker for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Immunol Res.

2022:11619312022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E,

Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW,

Levine DA, et al: Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune

cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 4:26122013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|