Introduction

Gastric cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related

death, ranking fifth in incidence and third in mortality worldwide.

In 2020, there were ~1.1 million new cases and ~769,000 deaths

globally, with the highest rates observed in East Asia, Eastern

Europe and South America (1). China

accounts for nearly half of the global burden, with particularly

high incidence in rural provinces such as Gansu and Henan. Despite

a decline in the age-standardized incidence rate (annual change of

−0.41%), the absolute number of new cases has risen due to

population aging and growth (2).

Together, these trends reflect the need for improved prevention and

treatment, especially in high-burden regions.

Deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) is a key molecular

feature of gastric cancer, often associated with microsatellite

instability (MSI)-high (MSI-H) status, resulting in genomic

instability and a high tumor mutation burden (TMB) (3). This, in turn, increases tumor

immunogenicity and enhances the likelihood of immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs) treatment response (4). In advanced gastric cancer, dMMR

accounts for 7–10% of cases, most frequently in gastric body

adenocarcinoma or elderly patients (5). Compared with proficient mismatch

repair (pMMR), dMMR is generally linked with a better prognosis but

reduced sensitivity to standard chemotherapy (5).

Clinical studies have confirmed that patients with

dMMR gastric cancer respond better to ICIs compared with

traditional treatments. Indeed, programmed death-1

(PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors have been

reported to markedly improve objective response rates (ORR) and

pathological complete response (pCR) rates (6). In one trial, the pCR rate was 57.9% in

patients receiving neoadjuvant immunotherapy, compared with 0.0% in

the chemotherapy group (7). In

addition, combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy has been

reported to prolong progression-free survival (PFS) (8). Consequently, dMMR and MSI-H have been

established as key predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy and have

received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for guiding

treatment decisions (9).

Nevertheless, a subset of patients with dMMR gastric

cancer still fail to benefit from immunotherapy. Factors such as

the tumor microenvironment, genetic mutations, loss of neoantigens

and acquired resistance may contribute to treatment failure.

Notably, the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) has emerged as a

critical determinant of immunotherapy success. Research suggests

that tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) within the tumor can

enhance response to ICIs by improving antigen presentation and

activating T and B cells (10,11).

Therefore, deciphering the immune microenvironment may help explain

variability in patient responses and guide more effective treatment

strategies.

The present study describes the clinical case of a

patient with dMMR gastric cancer who, despite receiving a

combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy, had suboptimal

treatment outcomes. Through analysis of the TIME before and after

treatment, coupled with bioinformatics analysis of patients with

dMMR gastric cancer, the present study aimed to identify factors

influencing immunotherapy efficacy and explore how these insights

can optimize future treatment strategies for patients with dMMR

gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

Case source

The present case was sourced from the Department of

Oncology at Southern University of Science and Technology Hospital

(Shenzhen, China). The initial consultation date of the patient was

in April 2022. The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Southern University of Science and Technology Hospital

[approval no. 2023(12)], and the patient signed an informed consent

form, agreeing that case information and test results from pre- and

post-treatment specimens may be used for academic reporting. The

standard treatment protocol strictly adhered to the 2021 Chinese

Clinical Oncology Society Guidelines for the Diagnosis and

Treatment of Gastric Cancer (12).

EBER in situ hybridization

EBER in situ hybridization was performed

using the EBER Probe kit (Roche Diagnostics, cat. no. 05997704001)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded sections (4 µm, fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin at room temperature for 24 h) were first subjected to

permeabilization with kit-supplied protease K (20 µg/ml in 1×PBS,

room temperature, 5 min), followed by post-fixation with 1×PBS

(room temperature, 1 min, 2 washes). Pre-hybridization was

conducted with kit-provided buffer (without probe) at 37°C for 30

min; then, hybridization was performed using the kit probe (diluted

1:50 in hybridization buffer, final concentration 2 ng/µl, 20 µl

per section) in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 16 h. Excess probe

was removed via sequential washes with 2×SSC, 0.5×SSC, and 0.2×SSC

(all at 48°C, 5 min per wash). Post-hybridization steps included

blocking with 5% BSA (cat. no. A7906; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA;

room temperature, 10 min), incubation with anti-digoxigenin primary

antibody (Roche Diagnostics, cat. no. 11093274910, 1:100 dilution,

37°C, 30 min) and biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary

antibody (Roche Diagnostics, cat. no. 11093074910, 1:200 dilution,

room temperature, 20 min). Detection was carried out with DAB

chromogenic substrate (Roche Diagnostics, cat. no. 11718096001,

room temperature, 10 min), and images were captured using an

Olympus BX53 light microscope (×200 magnification).

Immune microenvironment detection

methods pre- and post-treatment

Multiplex immunofluorescence staining was performed

by D Medicines (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The primary antibodies included

CD8, CD4, FoxP3, M1/M2 macrophage markers, and PD-L1; imaging was

conducted with a Leica DM6 B microscope at ×200 magnification.

Scanned images of each slide were subsequently overlaid to generate

a single composite image. The fluorescence images were then

imported into the AP-TIME software (0.3.6; 3D Biotech Ltd.) for

analysis. Pan-CK staining was used to distinguish between tumor

parenchyma and stroma. The number of different cell populations was

quantified by the number of stained cells/mm2 and the

percentage of positively stained cells among all nucleated cells.

In the TIME Profiling (TIME-PRO) test, ‘marge1’ and ‘marge2’ refer

to two different panoramic views or heat maps, illustrating the

distribution and state of immune cells within the tumor

microenvironment, and providing rich information concerning the

immune landscape of the tumor.

Data sources and analysis methods

Non-immune treatment cohort

The gastric adenocarcinoma dataset was downloaded

from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database [TCGA-stomach

adenocarcinoma (STAD)] (13),

comprising 440 patients (portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). After filtering

for cases with available MSI status, 383 cases were retained. RNA

sequencing data in transcripts per million format was extracted.

Among these cases, 75 were classified as MSI-H, 52 as MSI-low

(MSI-L) and 256 as microsatellite stability (MSS).

Immune treatment cohorts

A total of three cohorts were analyzed: i) Kim

cohort: Data was sourced from the Harvard Tumor Immune Dysfunction

and Exclusion database (,including 61 patients with gastric cancer

undergoing immunotherapy. After filtering for MSI status, 45 cases

were retained: 5 MSI-H, 1 MSI-L and 39 MSS (14); ii) Peking University Cancer Hospital

(PUCH) cohort: Data was obtained from the literature, comprising 39

patients with gastric cancer treated with immunotherapy (15); and iii) Esophagogastric

Cancer-Memorial Sloan Kettering (EGC-MSK)-2017 cohort: Data was

sourced from the aforementioned literature, including 30 patients

with gastric cancer receiving immunotherapy (16). After filtering for MSI status, 28

cases were included: 5 MSI-H and 23 MSS.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables (such as MSI subtype

distribution in different stages and immunotherapy response between

different MSI types) are summarized as frequencies (n), and the

χ2 test was used to assess intergroup comparisons. For

continuous variables (such as TMB and neoantigen load), the

Shapiro-Wilk test assessed normality. Subsequently, the normally

distributed variables were evaluated using the unpaired t-test

while non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the

Mann-Whitney U-test for two-group data. For multiple-group data,

ANOVA was used followed by Tukey's post hoc test for normally

distributed data, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used followed by

Dunn's multiple comparisons test as a non-parametric test. The

abundance of TIME-related indicators was calculated using the

CIBERSORT tool. Survival curves were generated using the

Kaplan-Meier method, and intergroup survival differences were

compared using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were

performed using R software (The R Foundation; version 4.4.1).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Case report

Patient information and

intervention

The patient, a 74-year-old man presented to the

Southern University of Science and Technology Hospital (Shenzhen,

China) in April 2022 with complaints of epigastric discomfort and

anorexia for 2 months. CT revealed diffuse gastric wall lesions

accompanied by multiple enlarged lymph nodes around the stomach,

suggesting the possibility of infiltrative gastric cancer (data not

shown). In April 2022, gastroscopy identified a large ulcer near

the pylorus that bled easily upon palpation. Biopsy confirmed a

diagnosis of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. In May 2022,

following further examinations including contrast-enhanced

thoracoabdominal computed tomography gastroscopy with biopsy, the

patient underwent a radical gastrectomy. Post-surgical pathology

analysis revealed a moderately-to-poorly differentiated gastric

adenocarcinoma, categorized as diffuse type according to Lauren's

classification (17). Cancer emboli

were observed in blood vessels, and nerve involvement was also

noted. Both surgical margins were negative for cancer; however,

lymph node metastasis was found in the surrounding adipose tissue

(3/16). Metastases were observed in the 8th lymph node

group (1/1), and the 1st and 3rd groups (3/5), while no metastases

were observed in the 9th group (0/3). The immunohistochemistry

results in accordance with standard clinical diagnostic protocols

were as follows: MutL homolog 1 (−, deletion), postmeiotic

segregation increased (S. Cerevisiae) 2 (−, deletion), MutS

homolog (MSH)2 (+, no deletion), MSH6 (+, no deletion), CK7 (+),

CK20 (−), C-erb-2 (0, negative) and EBER in situ

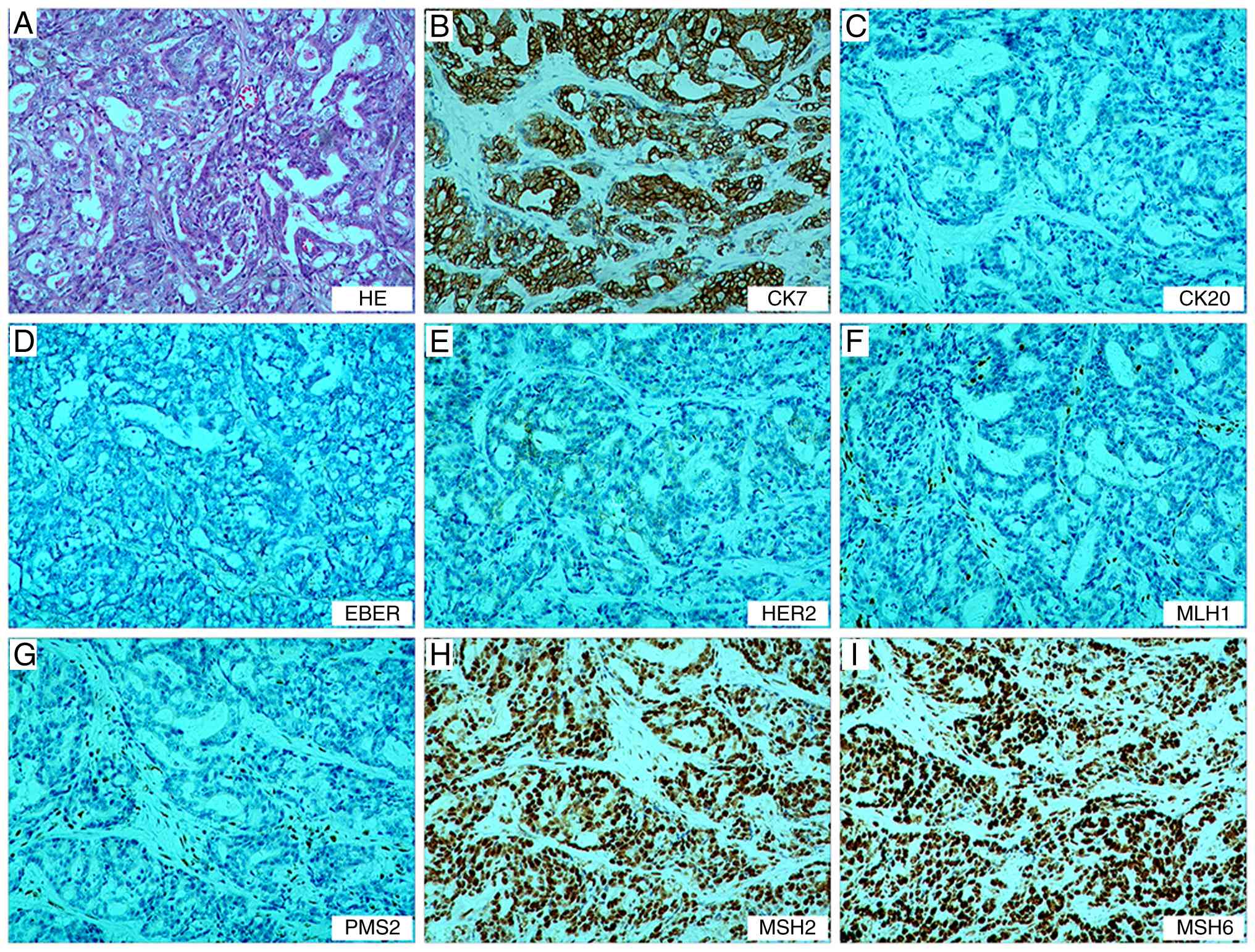

hybridization (−), (Fig. 1; data

for CK and Ki-67 are not shown)

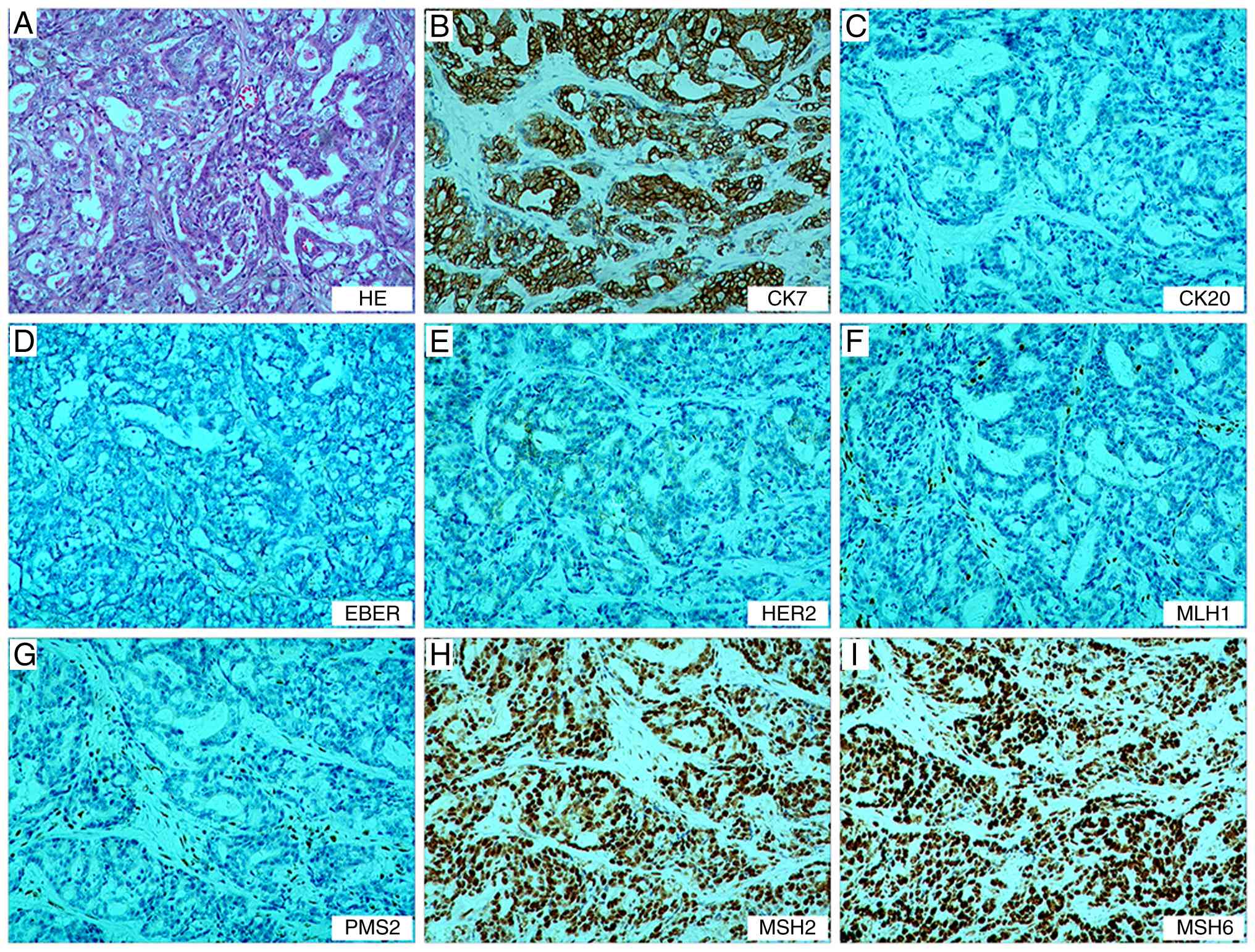

| Figure 1.Postoperative pathological findings

of the gastric tumor. (A) Tumor cells show diffuse/sheet-like

growth with focal glandular differentiation, increased

nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and hyperchromatic nuclei.

Immunohistochemistry demonstrates (B) CK7 (+), (C) CK20 (−), (D)

EBER (−), (E) C-erbB-2 (0), (F) MLH1 (−), (G) PMS2 (−), (H) MSH2

(+) and (I) MSH6 (+), confirming deficient mismatch repair status.

Magnification, ×100. MLH1, MutL homolog; PMS2, postmeiotic

segregation increased (S. Cerevisiae) 2; MSH, MutS

homolog. |

The tumor was staged as pT4bN3aM0 according to the

8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging

system (18). Postoperatively, the

patient received three cycles administered every three weeks

(length of each cycle: 21 days) of chemotherapy of the TS regimen

[docetaxel 75 mg/m2 + tegafur 60 mg twice a day (bid)].

During treatment, the patient developed grade IV bone marrow

suppression with infection, which improved after active management.

Due to the advanced age of the patient and refusal of further

aggressive chemotherapy, the patient was switched to single-agent

tegafur (60 mg bid) for five cycles (length of each cycle: 21

days). administered every 3 weeks. The treatment was

well-tolerated, and follow-up CT revealed no disease

progression.

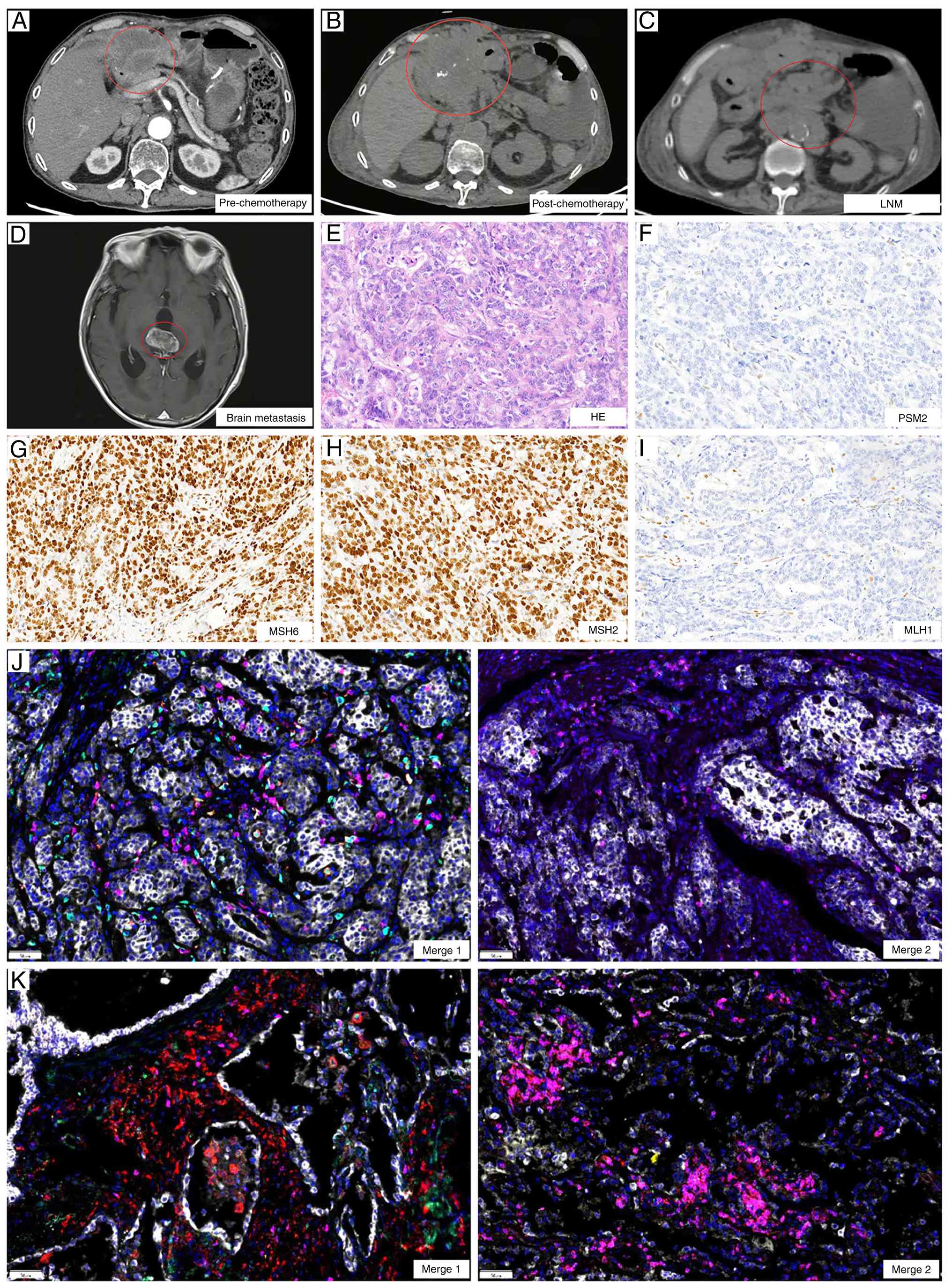

In January 2023, CT revealed abdominal metastases

involving the peritoneum and lymph nodes (Fig. 2A and C), indicating disease

progression. Therefore, 8 days later, the patient began treatment

with oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2) and capecitabine (1.5 g

bid) in combination with the PD-1 inhibitor toripalimab. During the

completion of two cycles administered every three weeks (length of

each cycle: 21 days) of treatment, the patient experienced reduced

appetite. Follow-up CT demonstrated continued lesion enlargement

compared with January 2023 and disease progression was confirmed as

per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.1 criteria

(Fig. 2A and B) (19). Although patients with dMMR gastric

cancer typically respond favorably to immunotherapy (20) the treatment outcome of the patient

in the present case was suboptimal, raising questions about whether

tumor heterogeneity or other factors contributed to the poor

response.

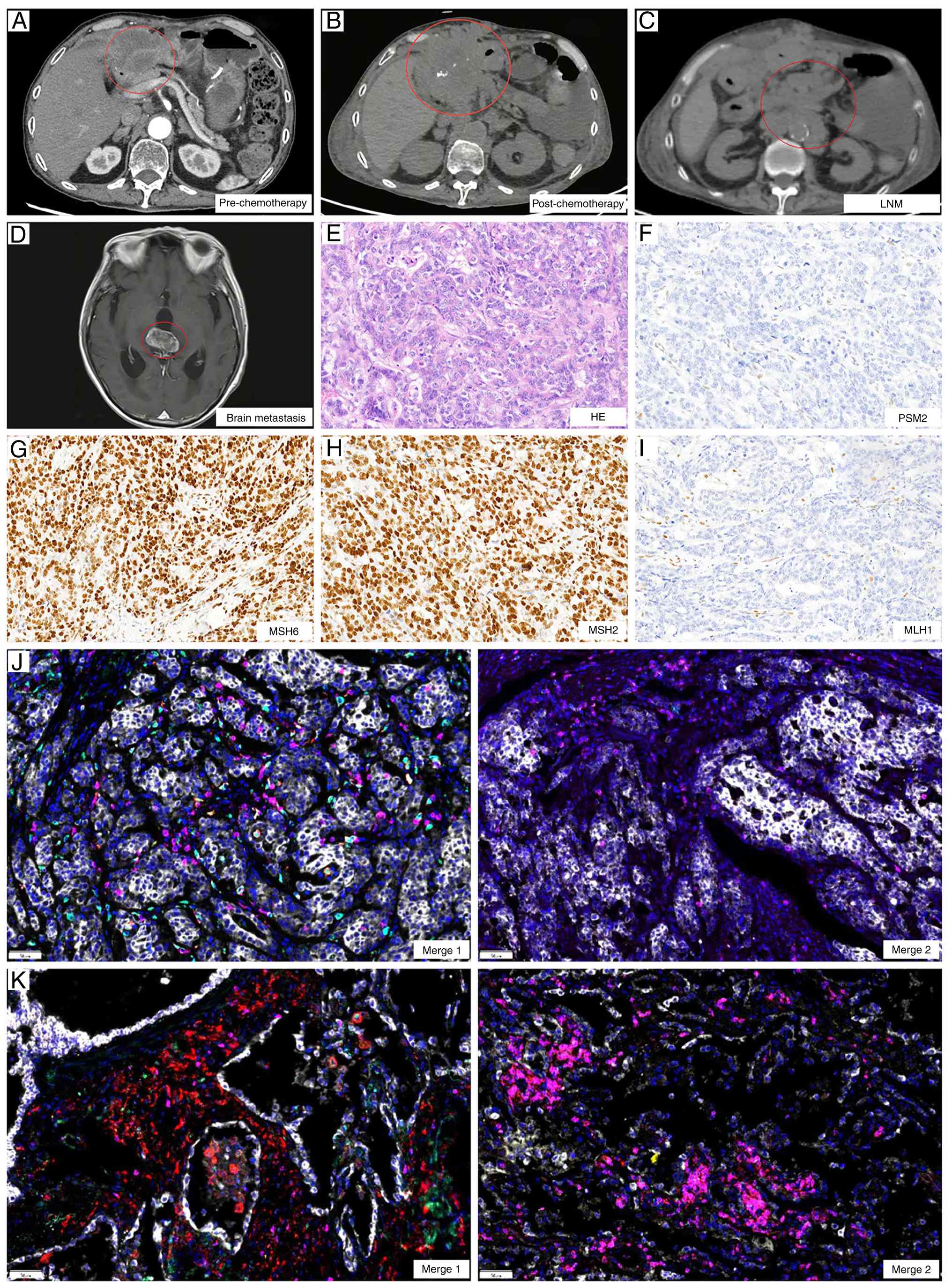

| Figure 2.Imaging and immune microenvironment

changes before and after treatment. CT images (A) before and (B)

after treatment. (C) Lymph node metastases after treatment. (D)

Brain metastases. Pathological examination of peritoneal puncture

lesions, showing (E) HE staining and (F) PMS2, (G) MSH6, (H) MSH2

and (I) MLH1 protein detection, consistent with postoperative

specimens (magnification, ×100). Tumor immune microenvironment

fusion images of (J) pre-treatment and (K) post-treatment

(magnification, ×200). Merge 1 shows PD-1 in green, programmed

death-ligand 1 in yellow, CD8 in pink, CD68 in cyan and CD163 in

red. Merge 2 shows CD3 in pink, CD4 in red, CD20 in green, CD56 in

cyan and forkhead box P3 in yellow. PMS2, postmeiotic segregation

increased (S. Cerevisiae) 2; MSH, MutS homolog; MLH1, MutL

homolog. |

The abdominal metastases were located near the

abdominal wall, and following patient consent, a biopsy of the

lesions was performed to further characterize them. The biopsy

results confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma and dMMR status,

consistent with baseline findings (Fig.

2E-I). To assess the potential underlying factors, both the

postoperative pathological specimen and the post-treatment biopsy

specimen underwent TIME-PRO assay.

TIME detection results

Before treatment, the TIME of the patient was deemed

‘immune cold’, characterized by low densities of CD3+ T

cells (19.4 cells/mm2) and CD8+ T cells

(19.32 cells/mm2), indicating a scarcity of total and

effector T cells, well below the threshold for a strong immune

response (CD8+ T cell density, ≥330.1

cells/mm2) (21). M1

macrophage density was also low (57.78 cells/mm2) and

forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), TLS

and CD20+ B cell counts were minimal, further confirming

the low immune reactivity (Table I,

Table II, Table III; Fig. 2J).

| Table I.Immune microenvironment assessment

results summary: Immune checkpoint expression levels. |

Table I.

Immune microenvironment assessment

results summary: Immune checkpoint expression levels.

| A,

Pre-treatment |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

Count/mm2, % |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Test index | Tumor

parenchyma | Stroma | TPS, % | CPS |

|---|

| PD-1 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | - | - |

| PD-L1 | - | - | <1 | <1 |

|

| B,

Post-treatment |

|

|

|

Count/mm2, % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Test

index | Tumor

parenchyma | Stroma | TPS, % | CPS |

|

| PD-1 | 0.53 (0.01) | 1.53 (0.02) | - | - |

| PD-L1 | - | - | <1 | <1 |

| Table II.Immune microenvironment assessment

results summary: Tumor immune microenvironment cell

composition. |

Table II.

Immune microenvironment assessment

results summary: Tumor immune microenvironment cell

composition.

| A,

Pre-treatment |

|---|

|

|---|

|

|

Count/mm2, % |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Test index | Tumor

parenchyma | Stroma |

|---|

| T cell-related |

|

|

|

CD3 | 19.40 (0.19) | 83.40 (0.85) |

|

CD3+CD4+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

CD8 | 19.32 (0.19) | 5.39 (0.08) |

|

FoxP3 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

PD-1+CD8+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

CD3+CD4+FoxP3+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

Macrophage-related |

|

|

|

CD68+CD163+ | 4.14 (0.04) | 1.71 (0.02) |

|

CD68+CD163− | 57.78 (0.55) | 57.59 (0.83) |

|

PD-L1+

CD68+ | 2.24 (0.02) | 3.11 (0.04) |

| NK

cell-related |

|

|

|

CD56bright | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

CD56dim | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| B Cell-related |

|

|

|

CD20 | 0.02 (0.00) | 2.38 (0.02) |

|

| B,

Post-treatment |

|

|

|

Count/mm2, % |

|

|

|

| Test

index | Tumor

parenchyma | Stroma |

|

| T cell-related |

|

|

|

CD3 | 439.29 (5.45) | 292.43 (3.59) |

|

CD3+CD4+ | 95.06 (1.18) | 54.84 (0.67) |

|

CD8 | 6.68 (0.10) | 3.00 (0.04) |

|

FoxP3 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.18 (0.00) |

|

PD-1+CD8+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

CD3+CD4+FoxP3+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

Macrophage-related |

|

|

|

CD68+CD163+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

CD68+CD163− | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

PD-L1+

CD68+ | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| NK

cell-related |

|

|

|

CD56bright | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

|

CD56dim | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| B cell-related |

|

|

|

CD20 | 17.07 (0.21) | 0.86 (0.01) |

| Table III.Immune microenvironment assessment

results summary: Tertiary lymphoid structure. |

Table III.

Immune microenvironment assessment

results summary: Tertiary lymphoid structure.

| Group |

Count/mm2 |

µm2/mm2 |

|---|

| Pre-treatment | 0.06 | 6,854.22 |

| Post-treatment | 0.00 | 0.00 |

After treatment, marked changes were observed.

Although PD-L1 remained negative [tumor proportion score, <1%;

combined positive score (CPS), <1], CD3+ T cell

density increased to 439.29 cells/mm2, primarily due to

CD3+CD4+ T cells (95.06

cells/mm2), while CD8+ T cells remained low

(6.68 cells/mm2), indicating a predominantly regulatory

immune response. FoxP3+ T cell density was 0.18

cells/mm2, suggesting potential immune suppression.

Meanwhile, B cell infiltration did not notably increase

(CD20+ B cells, 17.07 cells/mm2) and TLS

remained absent. Overall, despite increased T cell infiltration,

immune escape mechanisms and a suppressive microenvironment

continued to limit effective antitumor immune responses,

potentially compromising treatment efficacy (Table I, Table

II, Table III; Fig. 2K).

Follow-up

In March 2023, the patient developed changes in

mental status, such as bradyphrenia and irrelevant answers to

questions. Brain MRI revealed metastatic lesions (Fig. 2D), indicating poor disease control.

The patient was provided with optimal nutritional support but died

in April 2023 with an overall survival (OS) of 11.6 months

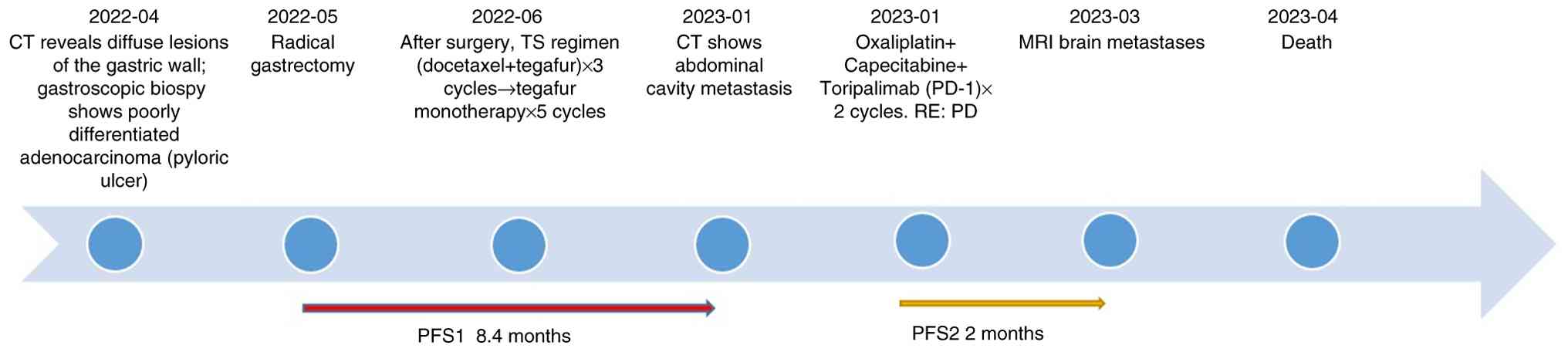

(Fig. 3).

Bioinformatics results

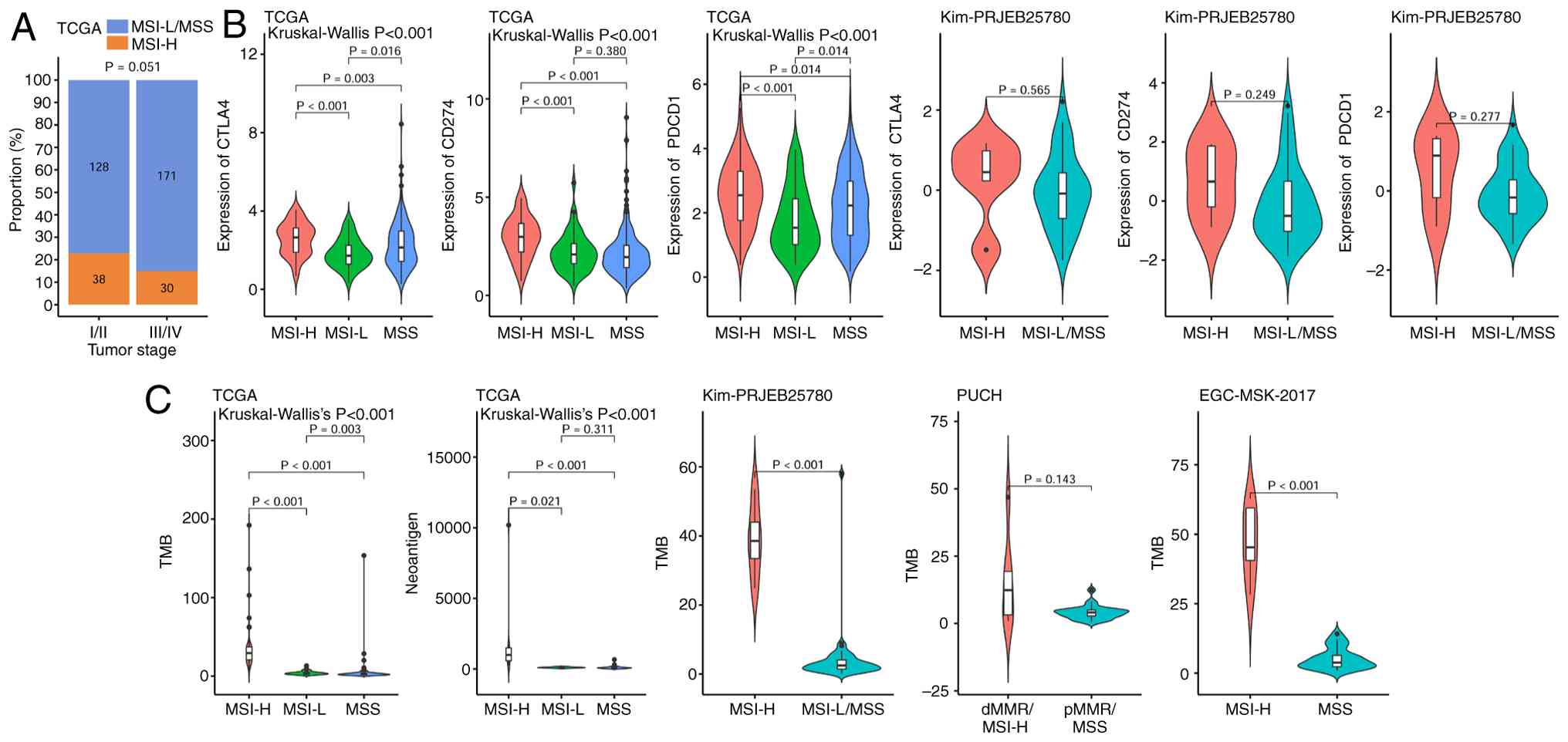

Association between MSI and clinical

Features

Table IV summarizes

the age distribution of patients with gastric cancer stratified by

MSI status across different cohorts. In the EGC-MSK-2017 cohort,

patients in the MSI-H group were significantly older than those in

the MSS group, while in the PUCH and TCGA cohorts, the age

difference between the MSI-H and MSS groups was not significant

Furthermore, the proportion of MSI-H patients with in gastric

cancer stages I/II was notably higher compared with those with

stages III/IV; however, statistical analysis revealed no

significant difference between the groups (Fig. 4A).

| Table IV.Age distribution by MS status in

different cohorts. |

Table IV.

Age distribution by MS status in

different cohorts.

| A, EGC-MSK-2017

cohort |

|---|

|

|---|

| MSI status | n | Minimum | Quartile 1 | Median | Mean | Quartile 3 | Maximum |

|---|

| MSI-H | 5 | 52.34 | 68.66 | 69.43 | 69.45 | 71.10 | 85.72 |

| MSS | 23 | 22.00 | 45.18 | 57.00 | 55.40 | 69.73 | 76.21 |

|

| B, PUCH

cohort |

|

| MSI

status | n | Minimum | Quartile

1 | Median | Mean | Quartile

3 | Maximum |

|

| MSI-H | 6 | 55.00 | 60.75 | 64.00 | 63.33 | 65.00 | 72.00 |

| MSS | 25 | 23.00 | 56.00 | 62.00 | 59.60 | 65.00 | 76.00 |

|

| C, TCGA

cohort |

|

| MSI

status | n | Minimum | Quartile

1 | Median | Mean | Quartile

3 | Maximum |

|

| MSI status | n | Minimum | Quartile 1 | Median | Mean | Quartile 3 | Maximum |

| MSI-H | 75 | 44.89 | 64.57 | 71.32 | 70.40 | 75.97 | 90.00 |

| MSI-L | 52 | 30.02 | 59.56 | 67.99 | 65.69 | 72.13 | 83.42 |

| MSS | 256 | 34.50 | 57.18 | 66.19 | 64.93 | 72.71 | 90.00 |

Association between MSI and immune

checkpoints

In TCGA gastric cancer cohort, the expression levels

of the immune checkpoint markers cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated

protein 4 (CTLA4), CD274 and programmed cell death protein 1

(PDCD1) were significantly higher in the MSI-H population compared

with in the MSI-L and MSS populations. Similarly, in the Kim

immunotherapy cohort, these markers were also notably elevated in

the MSI-H group compared with in the MSS group, although the

differences were not statistically significant, likely due to the

small sample size of only five patients with MSI-H (Fig. 4B).

Association between MSI, TMB and

neoantigen load

In TCGA gastric cancer cohort, the MSI-H group had a

significantly higher TMB and neoantigen load than the MSI-L and MSS

groups. Consistently, in the Kim and EGC-MSK-2017 immunotherapy

cohorts, patients with MSI-H also showed a significantly higher TMB

compared with those with MSI-L/MSS. Only the PUCH cohort

demonstrated no significant difference in TMB between groups,

possibly due to the small sample size (Fig. 4C).

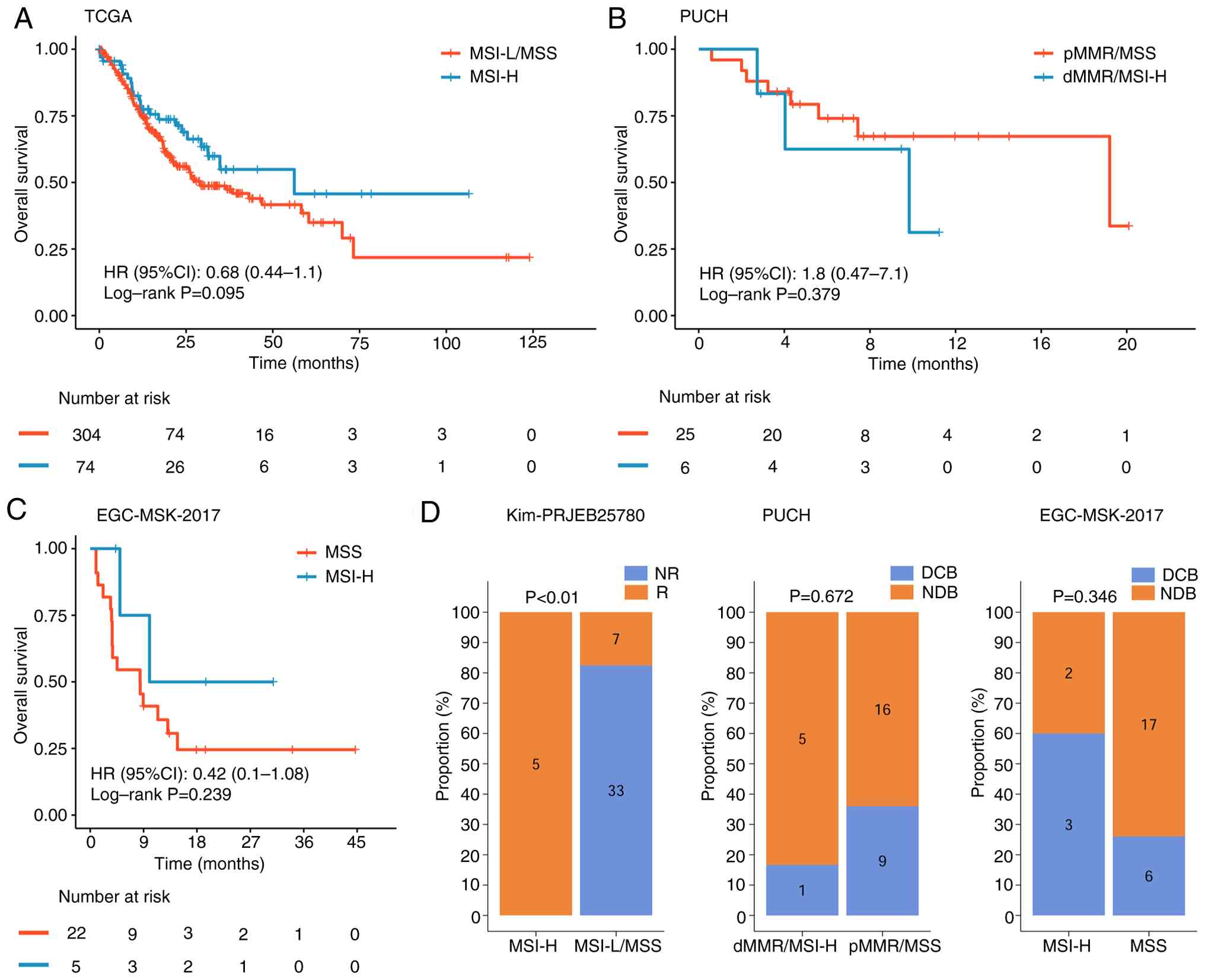

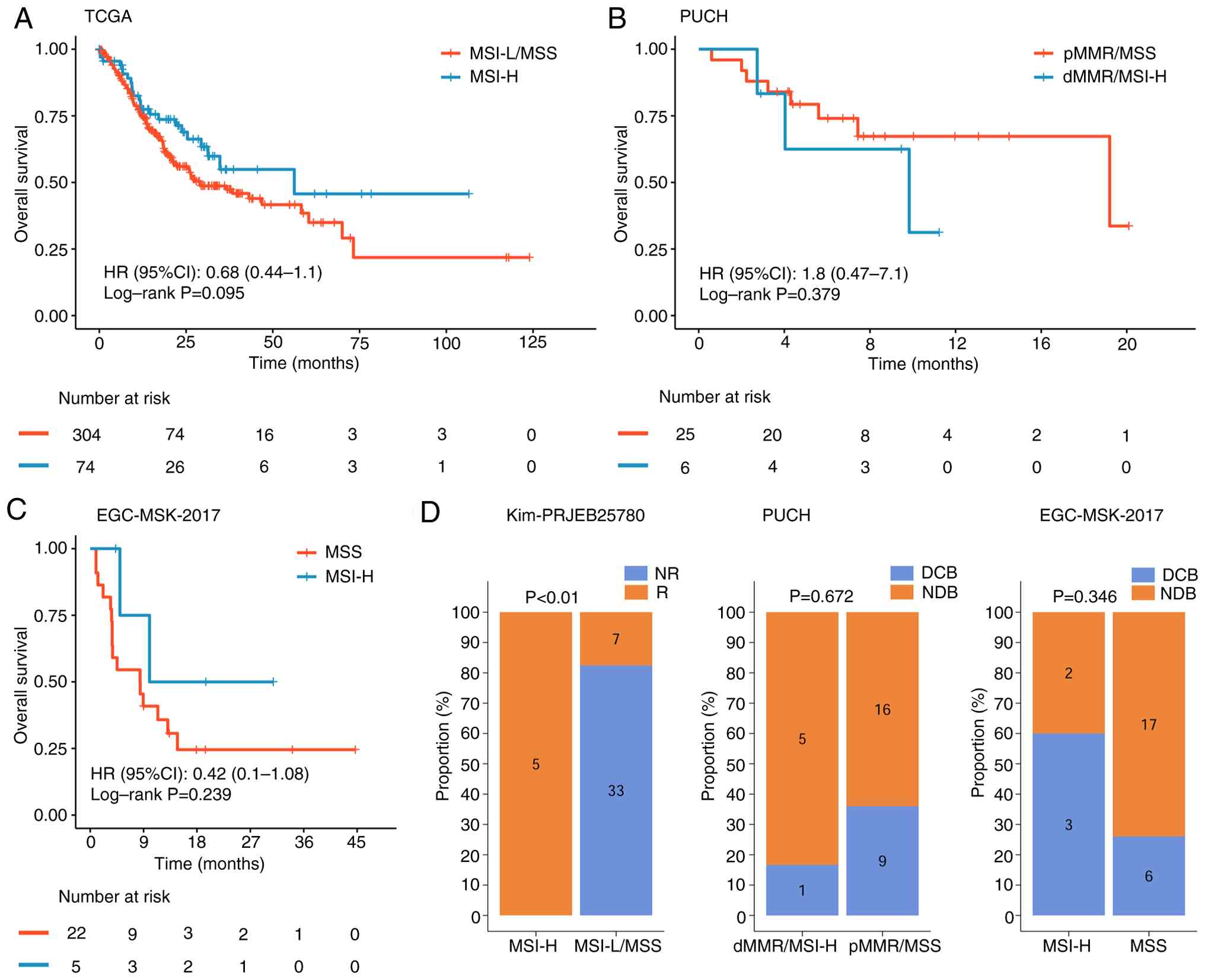

Prognostic differences between MSI-H

and MSS

In TCGA gastric cancer cohort, the MSI-H population

showed a trend toward improved OS, with a hazard ratio (HR) of

0.68; however, the difference between the MSI-H and MSI-L/MSS

populations was not statistically significant. In the PUCH

immunotherapy cohort, OS did not differ significantly between MSI-H

and MSS populations (HR, 1.8; log-rank P=0.379). Similarly, in the

EGC-MSK-2017 cohort, patients with MSI-H exhibited a trend toward

improved OS (HR, 0.42), but the difference was not statistically

significant (log-rank P=0.239) (Fig.

5A-C).

| Figure 5.Prognostic differences between MSI-H

and MSS groups across different databases. Survival analysis

performed in the (A) TCGA, (B) PUCH and (C) EGC-MSK-2017 cohorts.

(D) Immunotherapy response rates of patients with MSI-H in the Kim,

PUCH and EGC-MSK-2017 cohorts. NR, not reported; R, response; MSI,

microsatellite instability; H, MSI-high; MSS, microsatellite

stability; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; HR, hazard ratio; CI,

confidence interval; dMMR, deficient mismatch repair; MSI-L,

MSI-low; pMMR proficient mismatch repair; DCB, Durable Clinical

Benefit; NDB, Non-Durable Benefit. |

Differences in immunotherapy response

between MSI-H and MSS

Analysis of the Kim cohort demonstrated a

significant difference in immunotherapy response between the MSI-H

and MSS cohorts. By contrast, no significant difference was

observed in the PUCH cohort between the dMMR/MSI-H and pMMR/MSS

groups. In the EGC-MSK-2017 cohort, the MSI-H group exhibited a

markedly higher durable clinical benefit rate, but this difference

was not statistically significant compared with the MSS group

(Fig. 5D).

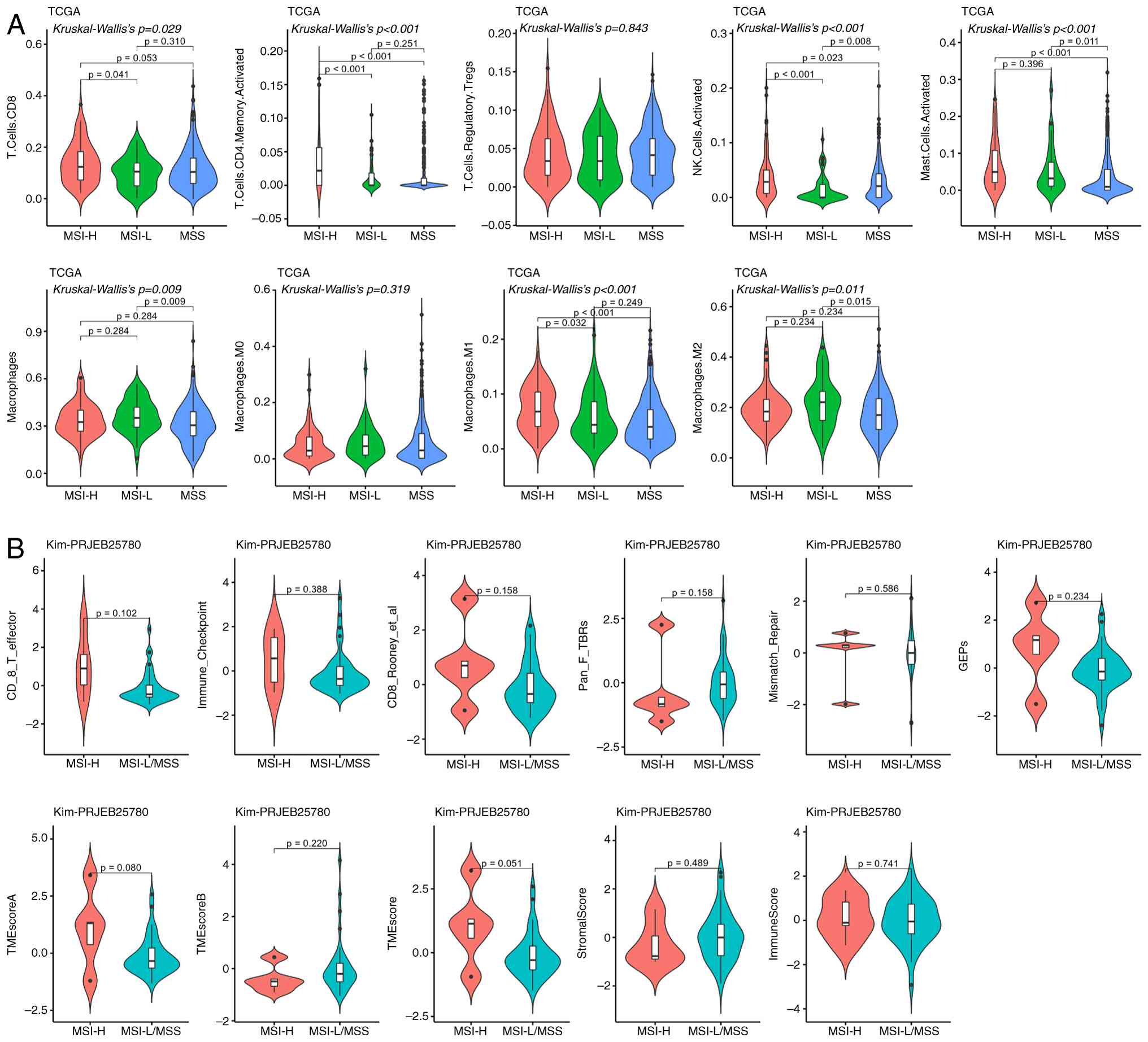

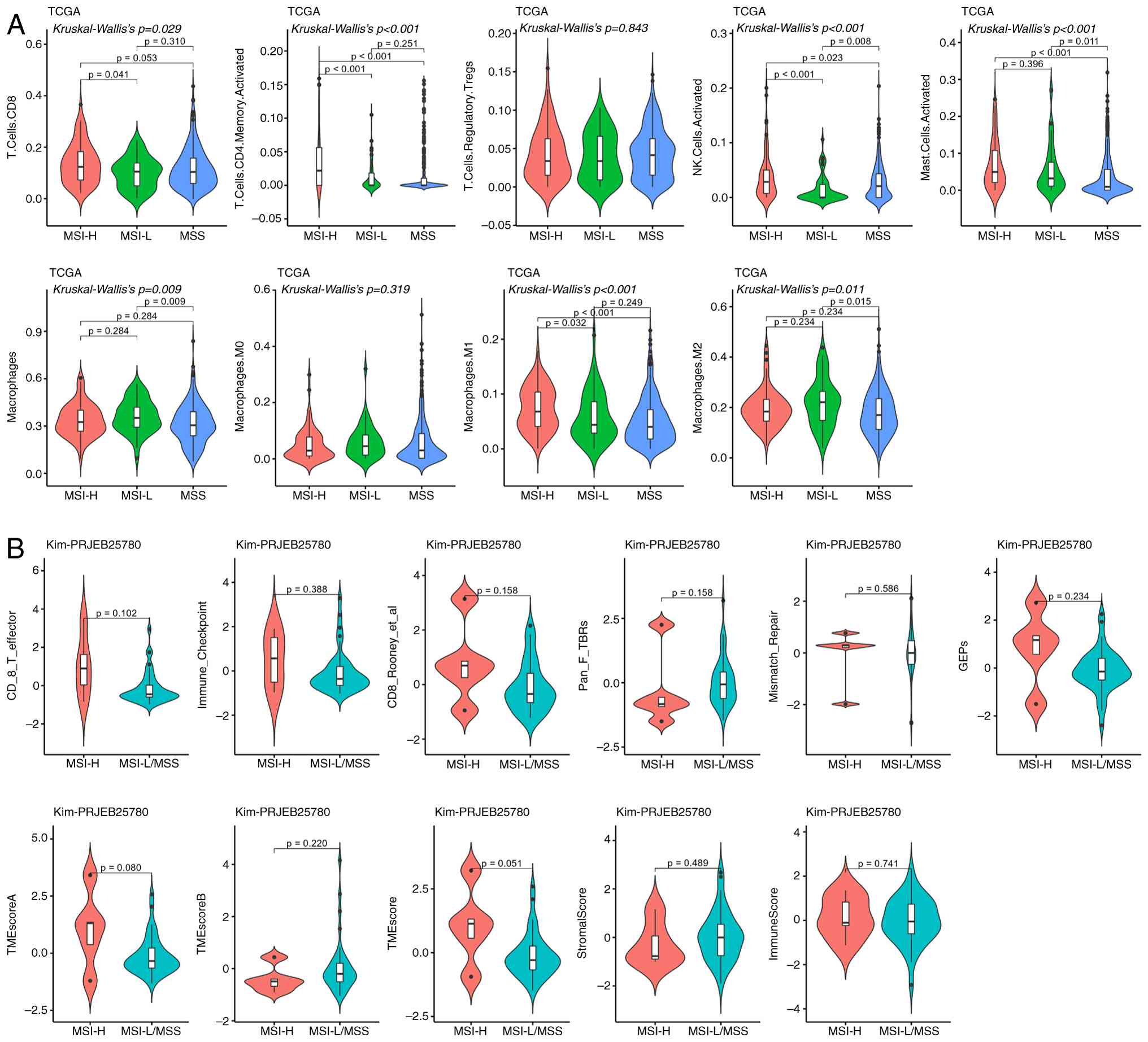

Immune microenvironment differences

between MSI-H and MSS

TCGA cohort revealed that, compared with the MSS

population, patients with MSI-H had a significantly higher

proportion of CD4+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells,

mast cells and M1 macrophages. For CD8+ T cells, a

significant difference was only observed between MSI-H and MSI-L

groups, with no difference detected between MSI-H and MSS groups

(Fig. 6A). In the Kim cohort, no

significant differences between MSI-H and MSS/LMSS groups were

demonstrated for any of the detected immune-related indicators

(Fig. 6B).

| Figure 6.Differences in the immune

microenvironment between MSI-H and MSS. (A) TCGA analysis

demonstrated that patients with MSI-H exhibited significantly

higher infiltration of memory-activated CD4+ T cells,

activated NK cells, mast cells and M1 macrophages than those with

MSS; CD8+ T cells showed a similar significant

difference between the MSI-H and MSI-L groups (P<0.05). (B) Kim

cohort analysis demonstrated no significant differences in detected

immune-related indicators between MSI-H and MSS/MSI-L (P>0.05).

MSI, microsatellite instability; MSI-H, MSI-high; MSS,

microsatellite stability; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; NK,

natural killer; MSI-L, MSI-low; NK, natural killer; TME, tumor

microenvironment; M1, type 1 macrophages. |

Discussion

The present study evaluated a patient with gastric

cancer with dMMR features who did not respond to immunotherapy, by

integrating multi-cohort bioinformatics data to elucidate the

complex role of the immune microenvironment in treatment responses.

Despite exhibiting a dMMR/MSI-H molecular profile, the tumor

microenvironment displayed characteristics of a ‘cold tumor’, with

very low PD-L1 expression (<1%), sparse tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes (TILs) and a modest accumulation of FoxP3+

Treg cells. This suggests that although MSI-H status is typically

considered a marker for sensitivity to immunotherapy, an

immunosuppressive microenvironment can undermine its

effectiveness.

In general, patients with dMMR gastric cancer tend

to have a high TMB and a rich load of tumor neoantigens, which

makes them more responsive to immune therapies (22). In TCGA and EGC-MSK-2017 cohorts,

patients with MSI-H demonstrated a significantly higher TMB;

however, this difference was not observed in the PUCH cohort,

likely due to sample size limitations. In TCGA cohort, the MSI-H

group generally displayed elevated expression of immune checkpoint

markers (such as CTLA4, CD274 and PDCD1) as well as increased

immune cell infiltration (such as CD8+ T and NK cells),

which could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting

immunotherapy outcomes.

Furthermore, despite the dMMR features of the tumor

in the presented case, the immune microenvironment exhibited clear

signs of immune inactivity, as demonstrated by low TIL levels and

extremely low PD-L1 expression (<1%), indicating the presence of

immune evasion mechanisms. Following treatment, although the number

of CD3+ T cells increased, there was no significant

enhancement in CD8+ T cell activity, and the

accumulation of FoxP3+ Treg cells in the tumor stroma

further supported the notion that the immunosuppressive environment

constrains effective immune responses (23). Furthermore, although there was an

increase in CD20+ B cells, their antitumor immune

effects did not show notable enhancement. The marked accumulation

of Treg cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), along

with antigen presentation deficiencies, may have impaired the

function of CD8+ T cells, leading to an overall lack of

immune activation (24). Moreover,

the low expression of PD-L1 could contribute to the poor response

to immunotherapy (25).

High TMB and dMMR status are typically considered

strong predictors of immunotherapy response (20), yet the present case, together with

the cohort data, revealed considerable heterogeneity between these

molecular features and clinical outcomes. Although the MSI-H cohort

in TCGA study exhibited elevated immune checkpoint expression, the

patient in the presented case had low PD-L1 expression, and

variability observed in the Kim cohort suggests that the level of

immune checkpoint expression may have an individual threshold

effect. Only when this threshold (such as CPS ≥1) was surpassed did

MSI-H features translate into therapeutic benefit. Therefore,

personalized treatment strategies should account for immune

microenvironment features and incorporate targeted therapies and

chemotherapy to enhance immune responses.

The present case stands in contrast to the

‘pro-inflammatory’ phenotype (increased M1 macrophages) observed in

the MSI-H group of TCGA cohort, suggesting functional heterogeneity

within the MSI-H population regarding immune infiltration. While

certain patients exhibit predominant immune infiltration by

effector cells, others, such as the patient in the presented case,

may experience immune suppression driven by regulatory cells,

resulting in treatment resistance.

The Keynote-062 study reported that patients with

dMMR have a markedly higher ORR (55%) compared with patients with

pMMR (25%) (26). Moreover, in the

Keynote-158 study, patients with dMMR reported an ORR of 50%

(including a complete response of 15% and a partial response of

34%), while patients with pMMR had an ORR of 7%. In addition, the

median PFS for patients with dMMR was 13.1 months, compared with

2.1 months for patients with pMMR (27). Nonetheless, 20–30% of patients with

dMMR do not respond to immune therapy (28). The present case represents a

‘non-responder’, in which the immune microenvironment (low PD-L1

and high Treg/MDSCs) deviates from the general trends observed in

the MSI-H cohort of TCGA study, yet aligns with reports of immune

evasion mechanisms documented in other studies (29,30).

This discrepancy may result from the interplay of several factors.

On the one hand, dysregulated WNT/β-catenin pathway activation can

impair neoantigen presentation, rendering high TMB tumors

non-immunogenic. Notably, activated β-catenin stemming from

dysregulated WNT pathways in dMMR tumors also suppresses TLS

formation via downstream effects on the tumor microenvironment,

specifically by modulating target molecules (such as c-Myc and

cyclin D1) or interfering with the Wnt/TCF/lymphoid enhancer factor

signaling axis (which regulates B cell chemokines such as chemokine

(C-X-C motif) ligand 13, critical for TLS assembly) (31). This explains the sparse TILs

observed in such cases. On the other hand, suppressive cells may

directly inhibit CD8+ T cell function through the

secretion of factors such as TGF-β and IL-10 (32,33).

Based on these findings, future predictive models should integrate

genomic features such as MSI status and TMB, immune

microenvironment composition such as CD8+ T cell/Treg

ratios, and dynamic functional indicators such as changes in PD-L1

expression, rather than relying on a single biomarker.

The present study highlights the importance of

individualized TIME evaluation. While traditional biomarkers, such

as dMMR and high TMB, predict the effectiveness of immune

therapies, immunosuppressive mechanisms within the microenvironment

may lead to treatment failure. Therefore, future strategies should

explore combined approaches based on TIME characteristics and

genomic profiles, such as novel antigen vaccines, adoptive T cell

therapy, anti-VEGF drugs (such as bevacizumab) or Claudin

18.2-targeted monoclonal antibodies (such as zolbetuximab) that

could reverse immune suppression and enhance efficacy (34,35).

Claudin 18.2, a tight junction protein aberrantly expressed in

30–50% of gastric cancers, has emerged as a promising target for

combination therapy with immunotherapy (33). This potential is further supported

by data from two phase III clinical trials, SPOTLIGHT and GLOW,

which reported that zolbetuximab in combination with chemotherapy

markedly improved PFS and OS in patients with gastric cancer

(36,37). However, as this agent was

unavailable at the time of treatment, the patient in the presented

case did not receive Claudin 18.2-targeted therapy, which may have

contributed to the suboptimal response.

However, the present study has certain limitations,

specifically the small number of cases included in the analysis may

restrict the generalizability of the observed results regarding

immune markers. Furthermore, the present study focused on

descriptive associations between immune markers and clinical

outcomes, without exploring the underlying biological mechanisms

linking these markers to immunotherapeutic sensitivity in

dMMR/MSI-H gastric cancer. Future studies should expand the study

population to include a larger and more diverse cohort, and

integrate functional experiments to elucidate the mechanistic

basis, thereby identifying more optimal immune markers for clinical

application.

In conclusion, the key conclusions of the present

study are as follows: First, in dMMR/MSI-H gastric cancer

(traditionally a subgroup with high TMB/neoantigen load favoring

immunotherapy), TIME with low CD8+ T cell infiltration,

high FoxP3+ Treg accumulation, absent TLS and low PD-L1

expression (<1%) is a critical indicator of immunotherapy

resistance. This is exemplified by the presented non-responsive

dMMR case. Second, cross-cohort analyses (TCGA-STAD, Kim, PUCH and

EGC-MSK-2017) indicate that despite the generally favorable

immunological features of MSI-H gastric cancers (such as higher

TMB, CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages and immune

checkpoints), their immunotherapy outcomes remain heterogeneous.

Third, dMMR/MSI-H status alone is insufficient to predict

immunotherapy responses; instead, individualized TIME evaluation

(integrating CD8+ T cell/Treg ratios, TLS presence and

PD-L1 expression) is necessary for precise treatment guidance.

Ultimately, combining genomic profiling (MSI and TMB) with TIME

assessment may address treatment heterogeneity in dMMR/MSI-H

gastric cancer and support exploring combined therapies (such as

Claudin 18.2-targeted agents and anti-VEGF drugs) to reverse

immunosuppression in non-responders.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research was funded by the Major Science and

Technology Project of Nanshan District Health and Wellness System

(grant no. NSZD2024067).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LW contributed to the study conception and design,

bioinformatics analyses, manuscript drafting, and integrated

clinical bioinformatics data interpretation. XZ and MD contributed

to clinical data acquisition and verification, clinical-molecular

feature association analysis, and drafting of the clinical section

of the manuscript. WD contributed to pathological data provision

and pathology-molecular subtype association interpretation. LW and

WD confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Ethical Review Committee of Southern University of Science and

Technology Hospital [approval no. 2023(12)]. The patient provided

written informed consent for the use of their samples and data in

the present study.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of this manuscript, including the use of any

potentially identifiable data and images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

MMR

|

mismatch repair

|

|

dMMR

|

deficient MMR

|

|

pMMR

|

proficient MMR

|

|

TMB

|

tumor mutational burden

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

TILs

|

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed death-ligand 1

|

|

Treg

|

regulatory T cells

|

|

MDSC

|

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

MSI-H

|

MSI-high

|

|

MSS

|

microsatellite stability

|

|

NK

|

natural killer

|

|

VEGF

|

vascular endothelial growth factor

|

|

CPS

|

combined positive score

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN Estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang TC, Chen H, Yin X, He Q, Man J, Yang

X and Lu M: Changing trends of disease burden of gastric cancer in

China from 1990 to 2019 and its predictions: Findings from Global

Burden of Disease Study. Chin J Cancer Res. 33:11–26. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang J, Xiu J, Farrell A, Battaglin F,

Arai H, Millstein J, Soni S, Zhang W, Shields A, Grothey A, et al:

Genomic landscapes to characterize mismatch-repair deficiency

(dMMR)/microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) gastrointestinal

(GI) cancers stratified by tumor mutation burden (TMB). J Clin

Oncol. 41 (16 Suppl):S2618. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H,

Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et

al: Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to

PD-1 blockade. Science. 357:409–413. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Petrelli F, Antista M, Marra F, Cribiù F,

Rampulla V, Pietrantonio F, Dottorini L, Ghidini M, Luciani A,

Zaniboni A and Tomasello G: Adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy

for MSI early gastric cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 16:1948–1957. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Takei S, Kawazoe A and Shitara K: The new

era of immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Cancers (Basel).

14:10542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang P and Gou H: Immunotherapy-based

therapy versus chemotherapy for the neoadjuvant treatment of

locally advanced dMMR/MSI-H gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 42

(16_suppl):e161212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Mou P, Ge Q, Sheng R, Zhu T, Liu Y and

Ding K: Research progress on the immune microenvironment and

immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 14:12911172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Marcus L, Lemery S, Keegan P and Pazdur R:

FDA approval summary: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of

microsatellite Instability-High solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res.

25:3753–3758. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hu L, Li T, Deng S, Gao H, Jiang Y, Chen

Q, Chen H, Xiao Z, Shuai X and Su Z: Tertiary lymphoid structure

formation induced by LIGHT-engineered and photosensitive

nanoparticles-decorated bacteria enhances immune response against

colorectal cancer. Biomaterials. 314:1228462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fridman W, Sibéril S, Pupier G, Soussan S

and Sautès-Fridman C: Activation of B cells in Tertiary Lymphoid

Structures in cancer: Anti-tumor or anti-self? Semin Immunol.

65:1017032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang FH, Zhang XT, Li YF, Tang L, Qu XJ,

Ying JE, Zhang J, Sun LY, Lin RB, Qiu H, et al: Clinical guidelines

for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer. Cancer Commun.

41:747–795. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Nature. 513:202–209. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kim ST, Cristescu R, Bass AJ, Kim KM,

Odegaard JI, Kim K, Liu XQ, Sher X, Jun H, et al: Comprehensive

molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition

in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat Med. 24:1449–1458. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jiao X, Wei X, Li S, Liu C, Chen H, Gong

J, Li J, Zhang X, Wang X, et al: A genomic mutation signature

predicts the clinical outcomes of immunotherapy and characterizes

immunophenotypes in gastrointestinal cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol.

5:362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Janjigian YY, Sanchez-Vega F, Jonsson P,

Chatila WK, Hechtman JF, Ku GY, Riches JC, Tuvy Y, Kundra R,

Bouvier N, et al: Genetic predictors of response to systemic

therapy in esophagogastric cancer. Cancer Discov. 8:49–58. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lauren P: The two histological main types

of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type

carcinoma. An attempt at a Histo-clinical classification. Acta

Pathol Microbiol Scand. 64:31–49. 1965. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC),

. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edition. Edge SB, Byrd DR,

Compton CC, et al: New York: Springer; 2017

|

|

19

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

André T, Tougeron D, Piessen G, de la

Fouchardière C, Louvet C, Adenis A, Jary M, Tournigand C, Aparicio

T, Desrame J, et al: Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab and

adjuvant nivolumab in localized deficient mismatch

Repair/Microsatellite Instability-high gastric or esophagogastric

junction adenocarcinoma: The GERCOR NEONIPIGA Phase II study. J

Clin Oncol. 41:255–265. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Obeid J, Hu Y, Erdag G, Leick K and

Slingluff C: The heterogeneity of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells

in metastatic melanoma distorts their quantification: How to manage

heterogeneity? Melanoma Res. 27:211–217. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ma W, Pham B and Li T: Cancer neoantigens

as potential targets for immunotherapy. Clin Exp Metastasis.

39:51–60. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hugo W, Zaretsky J, Sun L, Song C, Moreno

B, Hu-Lieskovan S, Berent-Maoz B, Pang J, Chmielowski B, Cherry G,

et al: Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to Anti-PD-1

therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 165:35–44. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N,

Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L,

et al: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 372:2018–2028. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

De Fátima Aquino Moreira-Nunes C, De Souza

Almeida Titan Martins C, Feio D, Lima IK, Lamarão LM, de Souza CRT,

Costa IB, da Silva Maués JH, Soares PC, de Assumpção PP and Burbano

RMR: PD-L1 expression associated with Epstein-Barr virus status and

Patients' survival in a large cohort of gastric cancer patients in

northern brazil. Cancers (Basel). 13:31072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shitara K, Van Cutsem E, Bang YJ, Fuchs C,

Wyrwicz L, Lee KW, Kudaba I, Garrido M, Chung HC, Lee J, et al:

Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus

chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone for patients With First-line,

advanced gastric cancer: The KEYNOTE-062 phase 3 randomized

clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6:1571–1580. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

O'Malley DM, Bariani GM, Cassier PA,

Marabelle A, Hansen AR, Acosta AJ, Miller WH Jr, Safra T, Italiano

A, Mileshkin L, et al: Pembrolizumab in microsatellite

instability-high/mismatch repair deficient (MSI-H/dMMR) and

non-MSI-H/non-dMMR advanced endometrial cancer: Phase 2 KEYNOTE-158

study results. Gynecol Oncol. 193:130–135. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi

S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, Desai J, Hill A, Axelson M, Moss RA, et al:

Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient

or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate

142): An open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol.

18:1182–1191. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zeng D, Wu J, Luo H, Li Y, Xiao J, Peng J,

Ye Z, Zhou R, Yu Y, Wang G, et al: Tumor microenvironment

evaluation promotes precise checkpoint immunotherapy of advanced

gastric cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 9:e0024672021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li N and Li Y, Li J, Tang S, Gao H and Li

Y: Correlation of the abundance of MDSCs, Tregs, PD-1, and PD-L1

with the efficacy of chemotherapy and prognosis in gastric cancer.

Lab Med. 56:259–270. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kim Y, Bae YJ, Kim JH, Kim H, Shin SJ,

Jung DH and Park H: Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a key signaling

pathway to trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer cells. BMC

Cancer. 23:9222023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bernal M, Ruiz-Cabello F, Concha A,

Paschen A and Garrido F: Implication of the β2-microglobulin gene

in the generation of tumor escape phenotypes. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 61:1359–1371. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Moaaz M, Lotfy H, Elsherbini B, Motawea M

and Fadali G: TGF-β enhances the Anti-inflammatory effect of

Tumor-infiltrating CD33+11b+HLA-DR Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

in gastric cancer: A possible relation to MicroRNA-494. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 21:3393–3403. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Niu Q, Liu J, Luo X, Su B and Yuan X:

Future of targeted therapy for gastrointestinal cancer: Claudin

18.2. Oncol Transl Med. 17:P102–P107. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang D, Huang G, Liu J and Wei W:

Claudin18.2-targeted cancer theranostics. Am J Nucl Med Mol

Imaging. 13:64–69. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shitara K, Lordick F, Bang YJ, Enzinger P,

Ilson D, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, Xu RH, Aprile G, Xu J, et al:

Zolbetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with CLDN18.2-positive,

HER2-negative, untreated, locally advanced unresectable or

metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma

(SPOTLIGHT): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3

trial. Lancet. 401:1655–1668. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Shah MA, Shitara K, Ajani JA, Bang YJ,

Enzinger P, Ilson D, Lordick F, Van Cutsem E, Gallego Plazas J,

Huang J, et al: Zolbetuximab plus CAPOX in CLDN18.2-positive

gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: The

randomized, phase 3 GLOW trial. Nat Med. 29:2133–2141. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|