Introduction

Erlotinib is an oral, small-molecule targeting

therapy that inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

of tyrosine kinase, blocking signal transduction pathways

implicated in the proliferation and survival of cancer cells

(1). EGFR is associated with

cellular processes leading to tumorigenesis (2,3). Data

exist concerning erlotinib administration for malignant tumors,

mainly pancreatic cancer, in combination with another cytotoxic

agent, as well as for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in a large

number of patients as a second-line treatment (4). Erlotinib has provided a survival

benefit for advanced NSCLC patients (5,6). The

data reported by two Phase III studies led to US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) approval for the use of erlotinib in NSCLC

patients after first-line chemotherapy failure. A survival benefit

was demonstrated in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer when

erlotinib was combined with gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine alone

(7). A survival benefit was even

shown in several subsets of NSCLC patients such as those with

squamous cell carcinoma, smokers and males, where gefitinib did not

appear to be active (5).

Serious adverse reactions are uncommon. The most

common side effects are skin rash and serious grade 3–4 anorexia

followed by fatigue, vomiting and stomatitis which were reported to

be less than 1%. Grade 3–4 diarrhea was also less than 1% (6).

The present study involves erlotinib monotherapy in

pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC. The primary objective was

to determine the response rate and survival in pretreated patients,

and the secondary objective was to determine toxicity.

Materials and methods

Patient eligibility

Eligibility for the study involved histologically or

cytologically confirmed NSCLC, disease staging and a defined

inoperable stage IIIB or IV. Stage IIIA was only included in case

of chronic respiratory insufficiency which did not permit surgery.

A requirement was that patients had to have undergone one or two

lines of prior chemotherapy. Radiation therapy was not excluded as

a previous treatment. Bidimensionally measurable disease criteria

were: physical examination, X-rays, computed tomography (CT), World

Health Organization (WHO) performance status 0–2, expected survival

≥12 weeks, adequate bone marrow reserves (leukocyte count ≥3,500

μl−1, platelet count ≥100,000 μl−1 and

hemoglobin ≥10 g dl−1), adequate renal function (serum

creatinine ≤1.5 mg/dl−1 and serum transaminases ≤3 times

the upper normal limit or ≤5 times the upper normal limit in cases

of liver metastases) and age ≥18 years. In cases of central nervous

system involvement or any secondary malignancy, patients were

excluded. The study was conducted with the approval of our

institutional review boards, and all patients gave their written

informed consent before enrollment.

Treatment

Erlotinib was administered at a dose of 150 mg (1

tablet) per day. In case of adverse reactions, treatment was either

reduced to 100 mg or interrupted for a maximum of two weeks.

Otherwise, treatment was continued until disease progression,

intolerable toxicity or refusal to continue.

Previous treatment

Before entering the study, patients had received

chemotherapy based on cisplatin (44 patients) or carboplatin (5

patients). The second agent of the combination was paclitaxel (40

patients), vinorelbine (4 patients), gemcitabine (3 patients) or

etoposide (2 patients). Eleven patients underwent second-line

chemotherapy 3–9 months after the end of the first-line treatment.

The agents administered for the second-line chemotherapy included

docetaxel, pemetrexed or etoposide. Five patients received a

combination of the first two aforementioned agents and 6 received a

single treatment of one of the three agents (Table I).

| Table IPatient characteristics. |

Table I

Patient characteristics.

| n (%) |

|---|

| Patients

enrolled | 54 (100) |

| Patients

assessable | 54 (100) |

| Gender |

| Male | 38 (70.37) |

| Female | 16 (29.63) |

| Age |

| Median | 65 |

| Range | 37–81 |

| WHO performance

status |

| 0 | 5 (9.26) |

| 1 | 43 (79.63) |

| 2 | 6 (11.11) |

| Disease stage |

| IIIB | 25 (46.30) |

| IV | 29 (53.70) |

| Histology |

| Adenocarcinoma | 25 (46.29) |

| Squamous cell

carcinoma | 19 (35.19) |

|

Undifferentiated | 10 (18.52) |

| Prior treatment |

| First-line |

|

Cisplatin-paclitaxel | 40 (74.07) |

|

Cisplatin-vinorelbine | 4 (7.41) |

|

Carboplatin-gemzar | 3 (5.56) |

|

Carboplatin-etoposide | 2 (3.70) |

| Second-line |

|

Docetaxel-gemcitabine | 3 (27.27) |

|

Carboplatin-etoposide | 2 (18.18) |

| Docetaxel | 3 (27.27) |

| Vinorelbine | 1 (9.09) |

| Pemetrexed | 2 (18.18) |

Baseline and treatment assessment and

evaluation

Before enrollment, the patients underwent physical

examination, tumor measurement and evaluation, WHO performance

status, electrocardiogram, full blood count, renal and liver

function tests and urinalysis. Staging was determined by chest and

abdominal CT scans, bone scan and occasional magnetic resonance

imaging. Blood counts, blood urea and serum creatinine were

measured before each treatment administration and every 3 weeks

thereafter. During the treatment period, radiologic tests were

conducted: a chest X-ray once every 3 weeks and CT once every 2

months, or whenever there were signs of disease progression.

Imaging-based evaluation was used to assess response. A complete

response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all measurable

disease, confirmed at 4 weeks at the earliest. A partial response

(PR) was defined as a 30% decrease, confirmed at 4 weeks at the

earliest. In stable disease (SD), neither PR nor progressive

disease (PD) criteria were met; PD involved a 20% increase in tumor

burden but no CR, PR or SD before increased disease. Response data

were based on the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

(8). A two-step deterioration in

performance status, a >10% loss in pretreatment weight or

increasing symptoms did not by themselves constitute progression of

the disease. However, the appearance of these signs was followed by

a new evaluation of the extent of the disease. Responses had to be

maintained for at least 4 weeks and to be confirmed by two

independent radiologists and two experienced oncologists.

Statistical design

This was an expected two-step Phase II study and an

intent-to-treat analysis. According to the trial design, 30

patients were to be enrolled during the first part of the study and

if an objective response rate of <15% was achieved, the

treatment would have been abandoned; otherwise, 20 additional

patients were to be enrolled. The primary objective of the study

was to determine the efficacy of the regimen with respect to

response and survival, and the secondary objective was to determine

the toxicity. Survival was calculated from the day of enrollment

until death or the end of the study. The median probability of

survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method; confidence

intervals (CIs) for response rates were calculated using methods

for the exact binomial CI.

Results

From April 2007 to December 2008, 54 patients with

advanced or metastatic NSCLC were enrolled in the present trial.

The patients were considered evaluable for response, toxicity and

survival. Patient characteristics at baseline are shown in Table I. The median age was 65 years (range

37–81) and their WHO performance status was 0–2. All patients had

undergone prior chemotherapy mainly based on cisplatin or a

carboplatin combination. Eleven of the 54 patients had undergone

second-line chemotherapy before entering the present trial. The

first- and second-line treatment is shown in Table I. The median duration of treatment

was 4 months (range 1.5–18); 40 patients (70.07%) underwent 4–18

months of treatment.

Response

Of the 54 assessable patients, an objective response

rate was observed in 10 (18.52%) patients, while the median

duration of response was 6 months (range 3–8). Stable disease was

observed in 40 patients (74.07%) and disease progression in 4

patients (7.41%). The response data are documented in Table II.

| Table IIResponse rate. |

Table II

Response rate.

| n (%) |

|---|

| Partial response | 10 (18.52) |

| Stable disease | 40 (74.07) |

| Disease

progression | 4 (7.41) |

Survival data

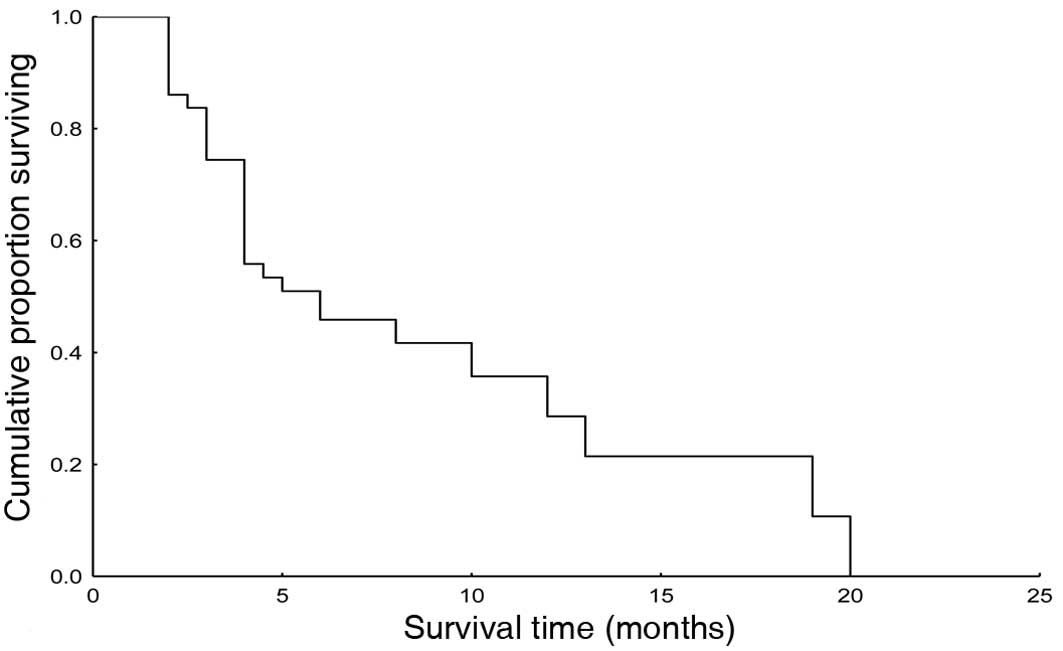

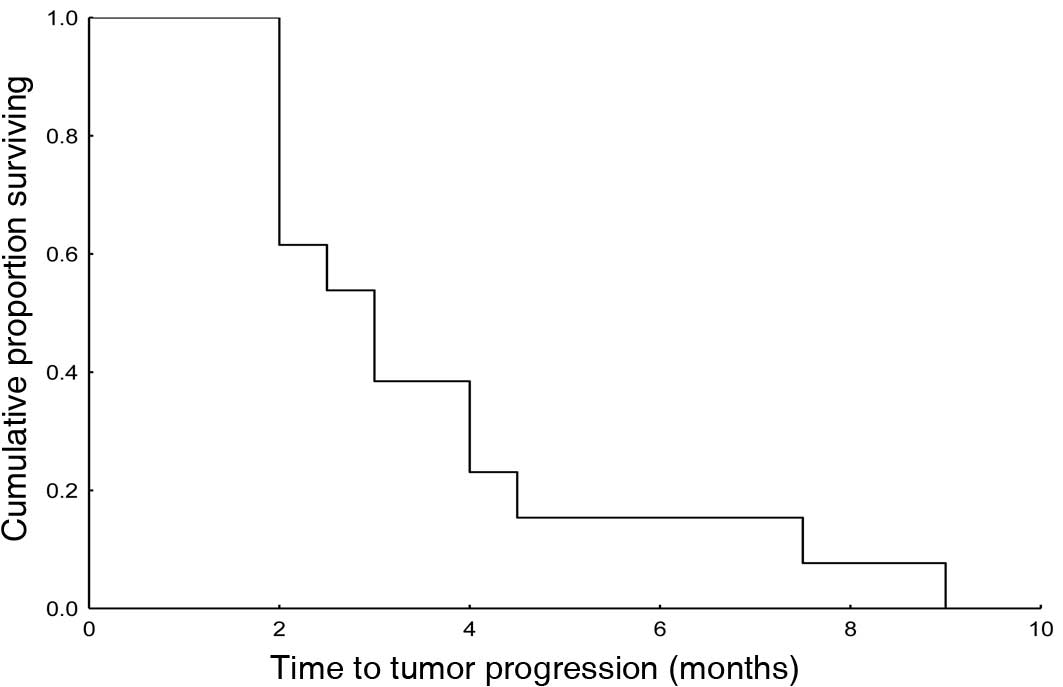

At the end of the study, 15 of the 54 patients were

still alive (27.77%). The median follow-up was 8 months (range

3–20). The median survival time was 6 months (95% CI 1.7–10.3).

Fig. 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier

survival curve. The median time to tumor progression (TTP) was 3

months (95% CI 1.9–4.1). TTP is shown in Fig. 2 (Kaplan-Meier).

Toxicity

Grade 1–2 skin rash was the main adverse reaction

observed in 53 of the 54 patients (98.15%). Grade 3 skin rash was

observed in 2 patients (3.70%) and this proved to be intolerable.

Thus, the dose of erlotinib was decreased from 150 to 100 mg. Other

non-hematologic toxicities were grade 1–2 diarrhea in 9 patients

(16.66%), nausea and vomiting in 4 (7.41%) and gastritis in 2

(3.70%). Hematologic toxicity (leukopenia and thrombocytopenia) was

not observed in 50 of the 54 patients (92.59%).

Discussion

One of the first growth factors discovered was the

epidermal growth factor (EGF) (9).

It is a protein which binds to a cell surface growth factor

receptor, the EGFR. In binding to the receptor, EGF either induces

cell proliferation or differentiation in mammalian cells (10).

The binding of a ligand to the EGFR induces

conformational changes within the receptor that increases the

catalytic activity of its intrinsic tyrosine kinase, resulting in

autophosphorylation which is necessary for biological activity

(11,12). Protein tyrosine kinase activity

plays a key role in the regulation of cell proliferation and

differentiation (13). A large

number of deletions of the EGFR in RNA have been observed in a

number of neoplasias such as glioblastoma in non-small cell lung

carcinomas, breast cancer, pediatric gliomas, medulloblastomas and

ovarian carcinomas (13).

Overexpression of mRNA and/or the protein encoded by the EGFR gene

has been observed in many types of human malignancies (14), including breast (15), gastric, colorectal (16) and bladder cancer (17). In NSCLC, EGFR expression at

percentages varying from 30 to 70% has been reported (18,19).

Erlotinib is an anti-EGFR targeting agent; studies have already

been performed and reports concerning its value have been

documented (20,21). However, despite the fact that

targeting therapy has been administered in a considerable number of

clinical trials over the recent years, there are many unanswered

questions related to the failure to achieve the expected success

and to explain certain adverse reactions or complications. Tumors

are likely to express variable but excessive numbers of HER1/EGFRs.

Unless all receptors are effectively inhibited from initiating

signaling, there is likely to be sufficient residual tumorigenic

activity to maintain disease (22).

Evidence, although unconfirmed, suggests that cancer types become

dependent on one or more specific elements of the cell signaling

circuit, requiring their continued presence in order to remain

malignant (23).

The results of the present trial showed that the

response rate is higher than that of the 8.5 and 9.5% reported in

previous studies (5,6). Of note is the high disease stability

(74.07%) and the median TTP of 4 months. Three other studies

reported a) a response rate of 13%, a SD rate of 54% and a

progression-free survival (PFS) of 9.7 weeks in 3,338 patients

(24); b) PR 9%, SD 67% and PFS

12.3 weeks in 4,002 patients (25);

and c) PR 12%, SD 56% and PFS 14.3 weeks in 6,809 patients

(26).

Erlotinib may be an eligible second-line treatment

for NSCLC patients. The majority of patients tolerate the treatment

and adverse reactions. Low toxicity increases the tendency to

support the use of erlotinib in pretreated NSCLC patients.

References

|

1

|

Baselga J and Arteaga CL: Critical update

and emerging trends in epidermal growth factor receptor targeting

in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 23:2445–2459. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jänne PA, Engelman JA and Johnson BE:

Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung

cancer: implications for treatment and tumor biology. J Clin Oncol.

23:3227–3234. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Swinson DE, Cox G and O’Byrne KJ:

Coexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor with related

factors is associated with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung

cancer. Br J Cancer. 91:1301–1307. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Comis RL: The current situation: erlotinib

(tarceva) and gefitinib (iressa) in non-small cell lung cancer.

Oncologist. 10:467–470. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Byoung C-C, Im C-K, Park M-S, et al: Phase

II study of erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer after

failure of gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 25:2528–2533. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shepherd FA, Pereira JR, Ciuleanu T, et

al: Erlotinib in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. N

Engl J Med. 353:123–132. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al:

Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in

patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a Phase III trial of the

National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin

Oncol. 25:1960–1966. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhawer EA, et

al: New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid

tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:205–216. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cohen S: The epidermal growth factor

(EGF). Cancer. 51:1787–1791. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yarolen Y and Schlessinger J: Epidermal

growth factor induces rapid reversible aggregation of the purified

epidermal growth factor receptor. Biochemistry. 26:1443–1451. 1987.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hsuan JJ: Oncogene regulation by growth

factors. Anticancer Res. 13:2521–2522. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Soler C, Beguinot L and Carpenter G:

Individual epidermal growth factor receptor autophosphorylation

sites do not stringently define association motifs for several SH-2

containing proteins. J Biol Chem. 269:12320–12324. 1994.

|

|

13

|

Voldborg RB, Damstrup L, Spang-Thomsen M,

et al: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and EGFR mutations,

function and possible role in clinical trials. Ann Oncol.

8:1197–1206. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ann J-H, Kim S-W, Hong S-M, et al:

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression in operable

non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 19:529–535. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sainsbury JRC, Nicholson S, Angus B, et

al: Epidermal growth factor receptor status of histological

sub-types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 58:458–460. 1988.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yasui W, Sumiyoshi H, Hata J, et al:

Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in human gastric and

colonic carcinomas. Cancer Res. 48:137–141. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Smith K, Fenelly JA, Neal DE, et al:

Characterization and quantitation of the epidermal growth factor

receptor in invasive and superficial bladder tumors. Cancer Res.

49:5810–5815. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Veale D, Kerr N, Gibson GJ, et al:

Characterization of epidermal growth factor receptor in primary

human non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 49:1313–1317.

1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fujino S, Enokibori T, Tezuka N, et al: A

comparison of epidermal growth factor receptor levels and other

prognostic parameters in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer.

32A:2070–2074. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hortobagyi GN and Santer G: Challenges and

opportunities for erlotinib (tarceva). What does the future hold?

Semin Oncol. 30(Suppl 7): 47–53. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Arteaga CL: The epidermal growth factor

receptor: from mutant oncogene in nonhuman cancers to therapeutic

target in human neoplasias. J Clin Oncol. 19:S32–S40.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Perez-Soler R: HER1/EGFR targeting:

refining the strategy. Oncologist. 9:58–67. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Weinstein IB: Addiction to oncogenes – the

Achilles heal of cancer. Science. 297:63–64. 2002.

|

|

24

|

Crino L, Eberhardt W, Boyer M, et al:

Erlotinib as second-line therapy in patients (PTS) with advanced

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and good performance status:

interim analyses from the TRUST Study. In: Abstract Book 33rd ESMO

Congress; (Suppl 8): pp. 2642008

|

|

25

|

Groen H, Barata F, McDermott R, et al:

Efficacy of erlotinib in >4000 patients (PTS) with advanced

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): analysis of the European

subpopulation on the TRUST Study. In: Abstract Book 33rd ESMO

Congress; (Suppl 8): pp. 2662008

|

|

26

|

Reck M, Mali P, Arrieta O, et al: Global

efficacy and safety results from the TRUST study of erlotinib

monotherapy in >7000 patients (PTS) with non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC). In: Abstract Book 33rd ESMO Congress; (Suppl 8):

pp. 2622008

|