Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs)

remain a significant cause of morbidity worldwide, with as many as

466,831 and 168,368 cases diagnosed in 2008 among men and women,

respectively (1–3). HNSCC patients with early clinical

stage disease (stages I and II) have similar survival rates, with a

5-year survival rate between 70 and 90%, independent of the

sublocation or the treatment (surgery vs. radiotherapy) (4). In contrast, HNSCC patients with

advanced clinical stage disease (stages III and IV) display

different survival rates depending on the histological type of the

tumor and its sublocation (4,5). In

this group, the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy allows

for a better local-regional control rate of up to 65% (6,7).

However, the obvious benefit of chemotherapy is associated with

higher (grade III and IV) toxicity and mortality (8). It is, therefore, crucial to predict

which patients will not benefit from concomitant chemoradiotherapy

(CCR).

During the last 30 years, we have observed a clear

increase in the incidence of carcinomas arising from the oral

cavity and the oropharynx in the United States and in Europe,

whereas the incidence of laryngeal carcinoma has been stable or has

decreased slightly (9). This

observation led us to propose that human papillomavirus (HPV)

infection is a new risk factor for HNSCC in younger, non-smoking

and non-drinking patients. In this subpopulation of HNSCC patients,

HPV+ tumors occur more frequently in the oropharynx than

in other sites and appear to have a more favorable prognosis than

HPV− carcinomas (10,11).

The better prognosis of HPV+ tumors was also reported

for advanced oropharyngeal carcinomas treated by CCR (12–20).

However, HPV-associated tumors have a different pathogenesis with

less chromosomal aberrations than tumors caused by alcohol and

tobacco abuse. In Belgium, the situation is more complex since our

HNSCC patients present with a higher incidence of HPV positivity

associated with alcohol and tobacco abuse. In this context, we

recently described that oral cavity HPV+ carcinomas are

associated with a worse prognosis that of HPV−

carcinomas (21). The aim of the

present study was to assess the impact of HPV positivity on the

response to CCR in a series of 72 HNSCC patients.

Materials and methods

Histopathological and clinical data

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded HNSCC specimens

were obtained from 72 patients (57 males, 15 females) who underwent

concomitant chemoradiotherapy at the Saint-Pieter Hospital

(Brussels) and Epicura (Baudour). The clinical data collected from

this series of 72 HNSCC patients are described in Table I. This prospective and retrospective

study was approved by the Institutional Review Board

(AK/09-09-47/3805AD).

| Table IClinical data of the HNSCC

patients. |

Table I

Clinical data of the HNSCC

patients.

| Variable | Patients

(n=72) |

|---|

| Gender |

| Male | 57 |

| Female | 15 |

| Age (years) |

| Mean | 57.9 |

| Range | 42–83 |

| Localization |

| Oral cavity | 19 |

| Oropharynx | 29 |

| Hypopharynx | 12 |

| Larynx | 12 |

| Grade

(differentiation) |

| Well | 29 |

| Moderate | 15 |

| Poor | 13 |

| In

situ | 2 |

| Not recorded | 13 |

| TNM stage |

| T1N2 | 4 |

| T1N3 | 1 |

| T2N0 | 1 |

| T2N1 | 3 |

| T2N2 | 5 |

| T3N0 | 8 |

| T3N1 | 9 |

| T3N2 | 10 |

| T4N0 | 5 |

| T4N1 | 6 |

| T4N2 | 19 |

| T4N3 | 1 |

| TNM stage I–IV |

| I | 0 |

| II | 1 |

| III | 20 |

| IV | 51 |

| Risk factors |

| Tobacco |

| Smoker | 54 |

| Non-smoker | 12 |

| Former

smoker | 6 |

| Alcohol |

| Drinker | 55 |

| Non-drinker | 7 |

| Former

drinker | 10 |

| Treatment |

| Cisplatin 100

mg/m2 (Day 1–21–42) |

| Two doses | 12 |

| Three doses | 23 |

| Cisplatin 40

mg/m2 (weekly) | 7 |

| Carboplatin

(weekly) | 7 |

| Cisplatin 100

mg/m2 (1 cycle) and carboplatin 40 mg/m2

(weekly) | 2 |

| Erbitux | 18 |

| Erbitux (2 cycles)

and cisplatin 40 mg/m2 (weekly) | 1 |

| Carboplatin +

5FU | 1 |

| Cisplatin 100

mg/m2 (2 cycles) and erbitux (1 cycle) | 1 |

| Radiotherapy

(n=70) |

| 70 Gy | 66 |

| >70 Gy | 1 |

| <70 Gy | 3 |

| Responders |

| Yes | 38 |

| No | 34 |

| Lymph node

dissection |

| Yes | 10 |

| Positive node | 3 |

| Negative node | 7 |

| No | 62 |

| Recurrence |

| Local | 10 |

| Nodal | 5 |

| Distant

metastases | 4 |

| Local + distant

metastases | 1 |

| Nodal + distant

metastases | 1 |

| Follow-upa |

| Range

(months) | 1–106 |

| Mean (months) | 30 |

DNA extraction

The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples

(n=72) were sectioned (10×5 μm), de-paraffinized and digested with

proteinase K by overnight incubation at 56°C. DNA was purified

using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Benelux, Belgium) according

to the manufacturer's recommended protocol.

Detection of HPV by polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) amplification

HPV detection was performed using PCR with

GP5+/GP6+ primers (synthesized by Eurogentec,

Liege, Belgium). The GP5+/GP6+ primers

amplify a consensus region located within the L1 region of the HPV

genome. The PCR amplification of the HPV-L1 DNA was performed in a

25-μl reaction mixture containing 2 μl of extracted DNA, 2.5 μl 1X

PCR buffer, 0.025 U Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany),

200 μM DNTPs and 0.5 pmol of each primer. The cycling conditions

for the PCR were as follows: denaturation was performed at 94°C for

1 min, annealing was performed at 55°C for 1 min and 30 sec, and

extension was performed at 72°C for 2 min, for a total of 45

amplification cycles. The first cycle was preceded by a 7-min

denaturation step at 94°C, and the last cycle was followed by an

additional 10-min extension step at 72°C. Aliquots (10 μl) of each

PCR product were electrophoresed through a 1.8% agarose gel and

stained with ethidium bromide to visualize the amplified HPV-L1 DNA

fragments.

Real-time quantitative PCR amplification

of the HPV type-specific DNA

All DNA extracts were tested for the presence of 18

different HPV genotypes using TaqMan-based real-time quantitative

PCR that targeted type-specific sequences of the following viral

genes: 6 E6, 11 E6, 16 E7, 18 E7, 31 E6, 33 E6, 35 E6, 39 E7, 45

E7, 51 E6, 52 E7, 53 E6, 56 E7, 58 E6, 59 E7, 66 E6, 67 L1 and 68

E7 (22). For the various real-time

quantitative PCR assays, the analytical sensitivity ranged from 1

to 100 copies and was calculated using standard curves generated

with plasmids containing the entire genome of the different HPV

types (23). Real-time quantitative

PCR for the detection of β-globin was performed in each PCR assay

to verify the quality of DNA in the samples and to measure the

amount of input DNA (23,24). The following HPV types tested were

considered high-risk (HR): 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53,

56, 58, 59 and 66.

Results

HPV status in our clinical series of

HNSCC patients treated by CCR

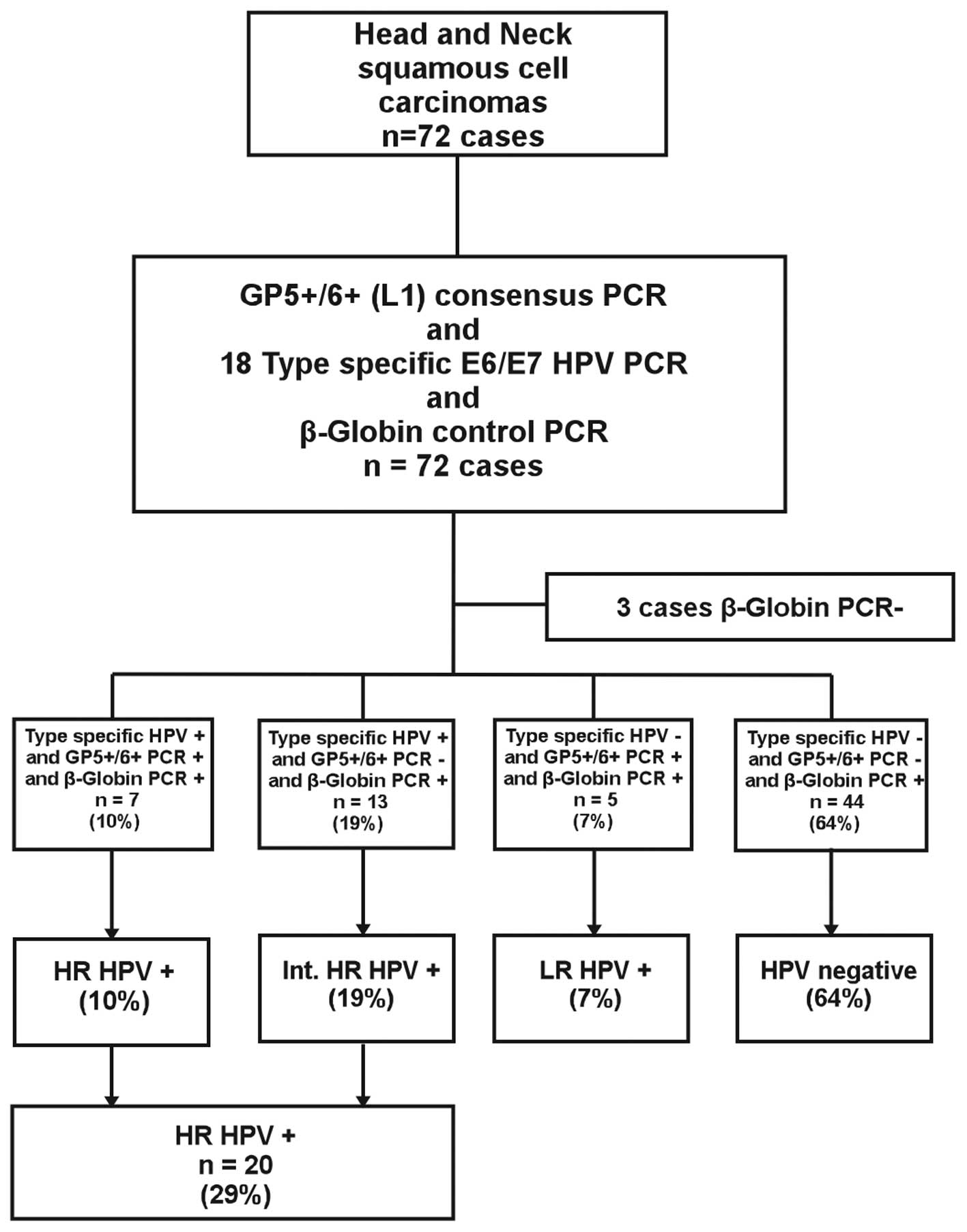

Of the 72 cases, three were excluded from further

analysis since β-globin could not be amplified (Fig. 1). Ultimately, 69 β-globin

PCR-positive specimens were typed by quantitative real-time PCR

using primers for 18 different HPV types. We identified 20 (29%)

patients whose tumors tested positive for the following HR HPV

types: 16 (15 cases), 59 (2 cases), 53 (2 cases), 58 (1 case), 66

(1 case) and 67 (1 case). One patient was infected with multiple

types of HR HPV (HPV 59 E7 and HPV 33, 52, 58, 67 L1). Among the 20

patients with HR HPV+ tumors, 7 tumors were both

GP5+/GP6+ positive (L1 detection) and

type-specific HPV positive (HR HPV+ group). However, 13

tumors were GP5+/GP6+ negative and

type-specific HPV positive, corresponding to an integrated

HPV+ group (int. HR HPV+). In the HR

HPV-negative group (n=49), 5 patients tested positive for HPV using

the GP5+/GP6+ consensus primers and were

considered to be infected with low-risk (LR) HPV types. Forty-four

tumors (64%) were negative for both GP5+/GP6+

and type-specific HPV upon PCR analysis (Fig. 1).

Correlation between HPV detection and

clinical data

The HPV+ group was composed of more men

(n=20, 77%) than women (n=6, 23%). The age ranged from 43 to 78

years, and most patients had stage IV disease (4 had stage III and

22 had stage IV). There was a clear predominance of smokers (n=19,

73%) or former smokers (n=6, 23%) and drinkers (n=23, 88%) or

former drinkers (n=1, 4%) compared to patients who did not consume

tobacco (n=1, 4%) or alcohol (n=2, 8%) (Table I). However, no statistical

correlation was found between the HPV status and the following

clinical data: gender, smoking status, alcohol status, sublocation,

differentiation, T and N stage.

Correlation between HPV detection and of

response rate to CCR

When analyzing the impact of HPV positivity on the

rate of response and non-response to CCR, we tested the potential

correlation using the two tests (GP5+/GP6+

PCR and qPCR) separately and also in combination. We investigated

whether one of these two tests or their combination could predict

the response to CCR. Interestingly, using the PCR

GP5+/GP6+ as a tool for HPV detection, the

rate of response to CCR was statistically lower, with 23% of

responders in the HPV+ group against 59% in the

HPV− group (P=0.02, Fisher's exact test). There was no

statistical correlation between the type of chemotherapy

administered and the number of responders according to HPV status

determined through consensus PCR or qPCR. Using the qPCR for HPV

detection, no statistical correlation was observed, and the rate of

response was lower in the HPV+ group (50%) than in the

HPV− group (57%).

Correlation between HPV infection and

prognosis in HNSCC patients

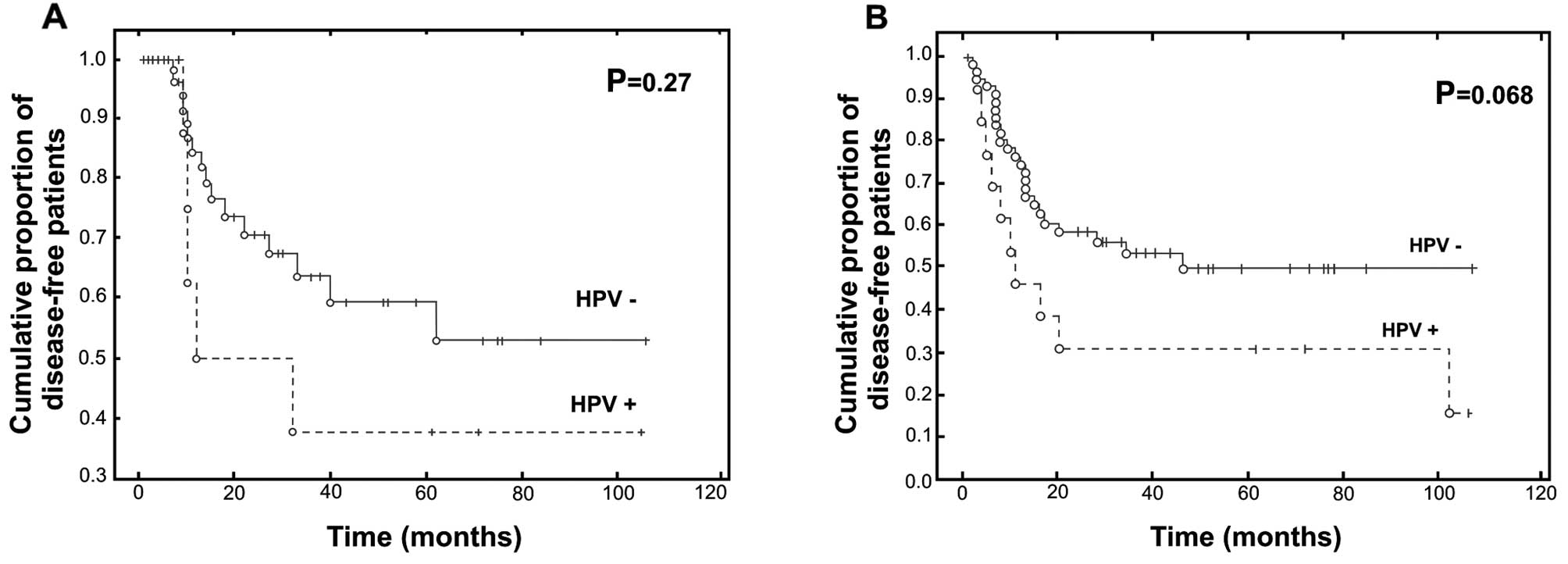

Based on the GP5+/GP6+ PCR

detection, we observed that the HPV+ group exhibited a

worse prognosis in terms of survival. In fact, the recurrence rate

was higher in patients with HPV+ carcinomas, at 38%,

while it reached only 27% among patients with HPV−

carcinomas (log-rank test, P=0.27) (Fig. 2A). However, the treatment did not

influence the recurrence rate; there was no significant difference

between patients who received platin or erbitux. Therefore, the

disease-free survival rate at 5 years was 57% for patients with

HPV− carcinoma vs. 23% for patients with HPV+

carcinoma (Gehan-Wilcoxon test, P=0.068) (Fig. 2B).

The percentages shown in the two curves do not

represent the total number of patients. The follow-up of several

patients was shorter than the first event of recurrence or

death.

Discussion

In the early 2000s, with the advent of CCR, we

observed a clear increase in the 5-year disease-free survival of

HNSCC stage IV patients, from 45 to 66% (25). However, CCR was also associated with

significant morbidity and mortality (notably, a higher incidence of

dysphonia and dysphagia) (26).

Therefore, clinicians are searching for new reliable prognostic

markers of CCR response and are considering the growing interest in

HPV infection in the biology of HNSCC. We decided to investigate

whether a correlation exists between HPV positivity and the

response to CCR in a series of 72 HNSCC patients with a history of

tobacco and alcohol use (in more than 90% of our population).

In our study, the prevalence of HPV positivity

reached 36%, with 29% of samples containing HR HPV DNA and 7% of

samples containing LR HPV DNA. Moreover, we observed that the rate

of response was statistically lower in the HPV+ group.

Several studies have reported that HPV DNA detection was closely

correlated to a more favorable prognosis in HNSCC patients treated

with CCR (Table II) (12–20).

| Table IIStudies that found a positive

correlation between HPV and response to chemoradiotherapy in

HNSCCs. |

Table II

Studies that found a positive

correlation between HPV and response to chemoradiotherapy in

HNSCCs.

| Authors (ref.) | No. of

patients | HPV prevalence

(%) | Anatomical

site | Smokers (n) | Drinkers (n) | Detection

methods |

|---|

| Kumar et

al(12) | 42 | 64 | Oropharynx | 34 | Not listed | qPCR |

| Chung et

al(17) | 46 | 50 | Oropharynx | Not listed | Not listed | PCR in situ

hybridization |

| Nichols et

al(18) | 44 | 61 | Oropharynx | Not listed | Not listed | In situ

hybridization |

| Fallai et

al(20) | 22 | 23 | Oropharynx | Not listed | Not listed | qPCR |

| de Jong et

al(19) | 75 | 49 | Pharynx

Oral cavity | Not listed | Not listed | Genetic

signature |

| Rischin et

al(13) | 172 | 65 | Oropharynx | 111 | Not listed | PCR in situ

hybridization |

| Hong et

al(15) | 35 | 24 | Head and neck

squamous cell carcinomas | Not listed | Not listed | qPCR |

| Lill et

al(14) | 29 | 38 | Head and neck

squamous cell carcinomas | Not listed | Not listed | PCR in situ

hybridization |

We recently revealed, in a large clinical series of

162 oral cavity carcinoma patients, that HPV+ tumors

were significantly associated with a poorer prognosis (27). The association between HPV

positivity and poor prognosis was also previously reported in two

Swedish studies in which oral HPV infection was associated with a

dramatically increased risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)

development (28,29). Clayman et al also showed that

HPV+ carcinomas were significantly correlated with a

decreased survival rate (30). In

fact, our results could be explained by the fact that our series

was mainly composed of smokers and/or drinkers (Table I), which is contrary to the majority

of studies describing a favorable prognosis for patients with

HPV+ tumors (Table II).

It should also be emphasized that HPV+ tumors related to

tobacco and alcohol consumption constitute a distinct biological

and clinical entity from HPV+ tumors without classical

risk factors, which are associated with a better outcome. In this

regard, trends in smoking behavior in Europe present some

significant differences (31). A

greater decline in smoking habits was observed among Norwegian,

Finnish and Dutch populations, highlighting that individuals in

Northern European countries are less exposed to classical risk

factors than those residing in Southern European countries

(31). Therefore, all studies

investigating the HPV status in HNSCC need to be interpreted with

caution since many are small clinical series without information on

the alcohol consumption and smoking status of their patients.

Moreover, our clinical series was composed of patients with an

extremely long-term follow-up (ranging from 0 to 106 months), which

is a crucial point for assessing the prognostic implications of HPV

infection.

A persistent HPV infection that can lead to the

development of epithelial cancer requires immune tolerance. Thus,

HPV has also developed several mechanisms to avoid detection by the

host immune defense system, such as downregulation of INF-α and

toll-like receptor 9, production of TGF-β and maintenance of low

viremia (viral protein synthesis is confined to keratinocytes

without an increase in cell death) (32–34).

In the absence of cell lysis, there is little or no release of the

pro-inflammatory cytokines that are crucial for the activation and

migration of dendritic cells (32,35).

There are limited data describing the interaction between the host

immune system during HPV infection in the context of HNSCC, which

means that the role of innate and adaptive immunity in this context

is largely unknown. As mentioned previously, in several studies,

HPV+ HNSCC was associated with an unfavorable outcome.

From these results, some authors supported the hypothesis that

immunosuppression favors HPV infection and that a failing immune

response may be negative in terms of prognosis for HPV+

HNSCC. In fact, Tung et al reported the presence of HPV-16

or HPV-18 and the Epstein Barr virus in 80% of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma samples (36). Another

study showed that herpes simplex virus-2 infection was associated

with an increased risk of HPV infection (37). In 2004, Kreimer et al

demonstrated that tonsillar HPV infection was strongly associated

with HIV co-infection and immunosuppression (38). More recently, we studied different

markers of the immune system in a large series of 110 HNSCC cases

(36 HPV+ cases vs. 74 HPV− cases) to study

the involvement of HPV infection in the alterations of the immune

system in a population of smokers and drinkers. We observed a

significant decrease in the number of natural killer cells and

dendritic cells in HPV+ samples compared to

HPV− samples (unpublished data).

In conclusion, we showed for the first time, in a

clinical series of 72 HNSCC patients, that the rate of response to

CCR was statistically lower in the HPV+ group. Notably,

the association between HPV positivity and an unfavorable prognosis

was discovered in a population of smokers and drinkers with HNSCC.

Our study also highlights the need for prospective, controlled

studies with larger numbers of patients, a detailed history of

tobacco and alcohol use among patients, and homogeneous treatments

and anatomical sites in order to confirm the impact of HPV

infection in HNSCCs treated with CCR.

Acknowledgements

Anaëlle Duray and Géraldine Descamps are PhD

students supported by a grant from the FNRS (Bourse Televie).

Christine Decaestecker is a Senior Researcher of the Belgian

National Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS, Brussels,

Belgium).

References

|

1

|

World Health Organization. International

Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan. 2008, Available from:

http://globocan.iarc.fr/.

|

|

2

|

Grandis JR, Pietenpol JA, Greenberger JS,

Pelroy RA and Mohla S: Head and neck cancer: meeting summary and

research opportunities. Cancer Res. 64:8126–8129. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shah JP and Patel SG: Head and Neck

Surgery and Oncology. 3rd edition. Mosby; New York: pp. 232–236.

352. 2003

|

|

4

|

Forastiere AA and Trotti A: Radiotherapy

and concurrent chemotherapy: a strategy that improves locoregional

control and survival in oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst.

91:2065–2066. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al: Final

results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy

Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with

concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx

carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 22:69–76. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Stenson KM, Kunnavakkam R, Cohen EE, et

al: Chemoradiation for patients with advanced oral cavity cancer.

Laryngoscope. 120:93–99. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Milano MT, Vokes EE, Kao J, et al:

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy in advanced head and neck

patients treated with intensive chemoradiotherapy: preliminary

experience and future directions. Int J Oncol. 28:1141–1151.

2006.

|

|

8

|

Hu M, Ampil F, Clark C, Sonavane K,

Caldito G and Nathan CA: Comorbid predictors of poor response to

chemoradiotherapy for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Laryngoscope. 122:565–571. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sturgis EM and Cinciripini PM: Trends in

head and neck cancer incidence in relation to smoking prevalence:

an emerging epidemic of human papillomavirus-associated cancers?

Cancer. 110:1429–1435. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dahlstrand H, Nasman A, Romanitan M,

Lindquist D, Ramqvist T and Dalianis T: Human papillomavirus

accounts both for increased incidence and better prognosis in

tonsillar cancer. Anticancer Res. 28:1133–1138. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Reimers N, Kasper HU, Weissenborn SJ, et

al: Combined analysis of HPV-DNA, p16 and EGFR expression to

predict prognosis in oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Cancer.

120:1731–1738. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, et al:

Response to therapy and outcomes in oropharyngeal cancer are

associated with biomarkers including human papillomavirus,

epidermal growth factor receptor, gender, and smoking. Int J Radiat

Oncol Biol Phys. 69:109–111. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Rischin D, Young RJ, Fisher R, et al:

Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in

patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III

trial. J Clin Oncol. 28:4142–4148. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lill C, Kornek G, Bachtiary B, et al:

Survival of patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer after

radiochemotherapy is significantly enhanced. Wien Klin Wochenschr.

123:215–221. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hong AM, Dobbins TA, Lee CS, et al: Human

papillomavirus predicts outcome in oropharyngeal cancer in patients

treated primarily with surgery or radiation therapy. Br J Cancer.

103:1510–1517. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sedaghat AR, Zhang Z, Begum S, et al:

Prognostic significance of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal

squamous cell carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 119:1542–1549. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chung YL, Lee MY, Horng CF, et al: Use of

combined molecular biomarkers for prediction of clinical outcomes

in locally advanced tonsillar cancers treated with

chemoradiotherapy alone. Head Neck. 31:9–20. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nichols AC, Faquin WC, Westra WH, et al:

HPV-16 infection predicts treatment outcome in oropharyngeal

squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 140:228–234.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

de Jong MC, Pramana J, Knegjens JL, et al:

HPV and high-risk gene expression profiles predict response to

chemoradiotherapy in head and neck cancer, independent of clinical

factors. Radiother Oncol. 95:365–370. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fallai C, Perrone F, Licitra L, et al:

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy or

radiochemotherapy: prognostic role of TP53 and HPV status. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 75:1053–1059. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pim D, Collins M and Banks L: Human

papillomavirus type 16 E5 gene stimulates the transforming activity

of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncogene. 7:27–32.

1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Depuydt CE, Benoy IH, Bailleul EJ,

Vandepitte J, Vereecken AJ and Bogers JJ: Improved endocervical

sampling and HPV viral load detection by Cervex-Brush Combi.

Cytopathology. 17:374–381. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Depuydt CE, Boulet GA, Horvath CA, Benoy

IH, Vereecken AJ and Bogers JJ: Comparison of MY09/11 consensus PCR

and type-specific PCRs in the detection of oncogenic HPV types. J

Cell Mol Med. 11:881–891. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Arbyn M, Benoy I, Simoens C, Bogers J,

Beutels P and Depuydt C: Prevaccination distribution of human

papillomavirus types in women attending at cervical cancer

screening in Belgium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 18:321–330.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Filleul O, Preillon J, Crompot E, Lechien

J and Saussez S: Incidence of head and neck cancers in Belgium:

comparison with worldwide and French data. Bulletin du Cancer.

98:1173–1183. 2011.

|

|

26

|

Saussez S: Cancer of the upper

aero-digestive tract: elevated incidence in Belgium, new risk

factors and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Mem Acad R Med Belg.

165:453–461. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Duray A, Descamps G, Decaestecker C, et

al: Human papillomavirus DNA strongly correlates with a poorer

prognosis in oral cavity carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 122:1558–1565.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Rosenquist K, Wennerberg J, Annertz K, et

al: Recurrence in patients with oral and oropharyngeal squamous

cell carcinoma: human papillomavirus and other risk factors. Acta

Otolaryngol. 127:980–987. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hansson BG, Rosenquist K, Antonsson A, et

al: Strong association between infection with human papillomavirus

and oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a

population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Acta

Otolaryngol. 125:1337–1344. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Clayman GL, Stewart MG, Weber RS,

el-Naggar AK and Grimm EA: Human papillomavirus in laryngeal and

hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Relationship to survival. Arch

Otolaryngol. 120:743–748. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Giskes K, Kunst AE, Benach J, et al:

Trends in smoking behavior between 1985 and 2000 in nine European

countries by education. J Epidemiol Community Health. 59:395–401.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Stanley MA: Immune responses to human

papillomaviruses. Indian J Med Res. 130:266–276. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hasan UA, Bates E, Takeshita F, et al:

TLR9 expression and function is abolished by the cervical

cancer-associated human papillomavirus type 16. J Immunol.

178:3186–3197. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lepique AP, Daghastanli KR, Cuccovia IM

and Villa LL: HPV16 tumor associated macrophages suppress antitumor

T cell responses. Clin Cancer Res. 15:4391–4400. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Stanley MA: Immune responses to human

papillomavirus. Vaccine. 24:16–22. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tung YC, Lin KH, Chu PY, Hsu CC and Kuo

WR: Detection of human papillomavirus and Epstein Barr virus DNA in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma by polymerase chain reaction. Kaohsiung J

Med Sci. 15:256–262. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Moscicki AB, Hills N, Shiboski S, et al:

Risks for incident human papillomavirus infection and low-grade

squamous intraepithelial lesion development in young females. JAMA.

285:2995–3002. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kreimer AR, Alberg AJ, Daniel R, et al:

Oral human papillomavirus infection in adults is associated with

sexual behavior and HIV serostatus. J Infect Dis. 189:686–698.

2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|