Introduction

The treatment of metastatic, locally unresectable

renal cell carcinoma (RCC) remains a challenge for urologists; one

reason is the poor response rate of the disease to many therapeutic

approaches, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Although targeted

molecular approaches including vascular endothelial growth factor

monoclonal antibodies, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and mammalian

target of rapamycin inhibitors that have shown promising results,

the overall response rates remain low (1). Thus, drugs targeting new signal

transduction pathways are desired.

Ubenimex (Bestatin) is a low-molecular-weight

dipeptide molecule that enhances the function of immunocompetent

cells and has diverse effects on the production of cytokines. It is

also known as an inhibitor of aminopeptidase N (APN), which is

identical to the cell surface molecule CD13 (2). APN is involved in various cellular

processes, including cell cycle control, cell differentiation and

motility, angiogenesis, cellular attachment and invasion/metastasis

of various malignancies (3).

Previous studies have shown that ubenimex has antitumor activity.

It inhibits the invasion of human metastatic tumor cells and

induces apoptosis in lung cancer and leukemic cell lines (4–6). In

tumor-bearing mice, ubenimex inhibits metastasis or tumor growth

and prolongs survival (7,8). In clinical studies, the drug has shown

beneficial effects in the treatment of leukemia, non-small cell

lung cancer, gastric cancer and cervical cancer (9–12). A

potential therapeutic effect of ubenimex in RCC is suggested by the

5-year remission in a case of residual lymph node metastasis of

RCC, following postoperative single administration of ubenimex

(13). However, there is little

data concerning the mechanism of ubenimex in suppressing tumor

cells in RCC. The purpose of the present study was to determine the

effects of ubenimex on the proliferation, migration and invasion of

RCC cells and the possible mechanism.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The 786-O and OS-RC-2 RCC cell lines were purchased

from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Cells were

maintained in RPMI-1640 (HyClone Biotechnology, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin and 10% FBS. The cells

were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2.

Western blotting

To determine the expression of APN, proteins were

extracted from the cells or tissues by suspension in RIPA buffer.

Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min and the

supernatants were recovered for analysis. The protein

concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein method

and the BCA protein assay kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein

(40 μg) was electrophoresed on a pre-cast Bis-Tris polyacrylamide

gel (8%) and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membranes

were blotted with rabbit anti-APN (1:1,000; Epitomics

Biotechnology, Burlingame, CA, USA), rabbit anti-LC3B (1:1,000;

Sigma) rabbit anti-Caspase3 (1:1,000, Abgent; San Diego, CA, USA)or

mouse anti-GAPDH (1:3,000 TA08; ZsBio), followed by horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000; ZB2306

and ZB2301; both from ZsBio, Beijing, China). Immunoblots were

visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (LAS4000).

Enzyme activity assay

The APN activity in the RCC cells was detected

spectrophotometrically using L-leucine-p-nitroanilide (Peptide

Institute, Inc., Osaka, Japan) as an APN substrate. Cells

(5×104) were incubated in a 96 well microtiter plate

with 0.1, 0.25 or 0.5 mg/ml ubenimex at 37°C for 24 h. After

culture, the medium was aspirated, the cells were washed with PBS

and then 200 μl of 1 mM alanine-p-nitroanilide was added per well.

Each well was then incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The APN enzyme

activity was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm using

a microplate reader (Labsystems, Multiskan Bichromatic, Helsinki,

Finland).

Growth curve analysis

Cells were trypsinized and 1.0×104 cells

were plated in individual wells of a 24-well plate containing

RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. Cells were treated with 0.1, 0.25 or 0.5

mg/ml ubenimex. Every 24 h, the medium was removed, adherent cells

were trypsinized and the total number of adherent cells in each

well was quantified using a hematocytometer. The cell counts for 3

wells/time-point were averaged for each group and the data were

used to draw growth curves.

WST-8 cell proliferation assay

Cells in an exponential phase of growth were

harvested and seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3,000

cells/well in RPMI-1640 supplemented with different concentrations

of ubenimex. After a 24 or 48 h culture, a 10 μl WST-8 solution

(WST-8 cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assay kit; Dojindo,

Kumamoto, Japan) was added into each well. Plates were then

incubated for an additional 1 h at 37°C and the absorbance was

determined using a microplate reader (EL340 Bio-Tek Instruments,

Hopkinton, MA, USA) at 450 nm.

Wound healing migration assays

The RCC cells were plated in 6-well culture plates

and grown to ~100% confluency before scratching with a sterile P200

pipette tip across the monolayer. The cell debris were removed by

being washed with PBS and the cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 and

2% FBS supplemented with different concentrations of ubenimex. The

area of the scratch was measured at 0, 12 and 18 h and

quantification was performed by measuring the area of cell

migration at different time points compared to the scratch area at

0 h. Each experiment was repeated 3 times.

Matrigel invasion assay

Invasion assays were performed using Transwell

chambers that were pre-coated with 40 μl of 1 mg/ml Matrigel matrix

(BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA, USA). Control untreated cells or cells

treated with ubenimex (0.25 mg/ml for 24 h) were trypsinized and

1.0×105 cells were plated in the upper wells in a

serum-free medium, while medium with 10% FBS was added to the lower

well as a stimuli. After 12 h of incubation, the cells on the

Matrigel side of the chambers were removed with a cotton swab. The

inserts were fixed in methanol and stained with H&E staining.

The number of the invading cells attached to the other side of the

inserts was counted under a light microscope using 8 random fields

at ×200 magnification. The experiment was performed in

triplicate.

LDH cytotoxicity assay

The levels of LDH release were assessed as a method

for determining the extent of cell death irrespectively of the type

of death. A 200 μl volume of cell suspension in complete medium

(5×103 cells/well) was dispensed in each well of a

96-well plate. Ubenimex (0.25 or 0.5 mg/ml), 3-MA (2 mM) and/or

rapamycin (0.1 μM) was added for 24 h. The 96-well plates were

centrifuged for 5 min at 400 × g and then 120 μl of the supernatant

from each well was transferred to a new plate. The plates were

incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark and then the

absorbance was spectrophotometrically measured at a wavelength of

560 nm.

Electron microscopy

The RCC cells were treated with 0.25 mg/ml ubenimex

for 12 h. They were then fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde and 2%

paraformaldehyde in a 0.1 M PBS buffer for 30 min, postfixed with

1% osmium tetroxide for 1.5 h, washed and stained in 3% aqueous

uranyl acetate for 1 h, then dehydrated in an ascending series of

ethanol and acetoned and embedded in Araldite. Ultrathin sections

were cut on a Reichert ultramicrotome, double stained with 0.3%

lead citrate and examined on a JEOL-1200EX electron microscope

(Jeol, Tokyo, Japan).

Human tissues

RCC tissues were obtained from 76 patients diagnosed

with RCC (median age, 63.8 years; range, 19–85) who were treated by

radical nephrectomy at Shandong Provincial Hospital (Jinan, China)

between July 2009 and January 2011. Formalin-fixed and

paraffin-embedded specimens were used in our analysis. Ten

specimens of non-neoplastic renal tissues were also obtained from

these patients. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Shandong Provincial Hospital.

Construction of tissue microarray blocks

and immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays were constructed using a manual

tissue arrayer (Beecher, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Three cylindrical

core biopsies (0.6-mm in diameter) were taken from different sites

of each tumor and precisely arrayed using a recipient paraffin

tissue microarray block. Ten specimens of the non-neoplastic renal

tissues were also resected from adjacent regions of the RCCs and

analyzed for comparison. To assess APN expression, 4-μm tissue

microarray sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and

subsequently incubated with monoclonal rabbit antibodies targeting

human APN (1:500; Epitomics Biotechnology). Hematoxylin served as a

counter-stain. Incubation without the primary antibody was used as

a negative control. The expression of APN was evaluated by two

independent assessors at ×200 magnification and scored as follows:

−, negative; +, weak; ++, moderate and +++, strong.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed statistically by the Student’s

t-test, χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test and analysis was

performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS

for Windows package release 10.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

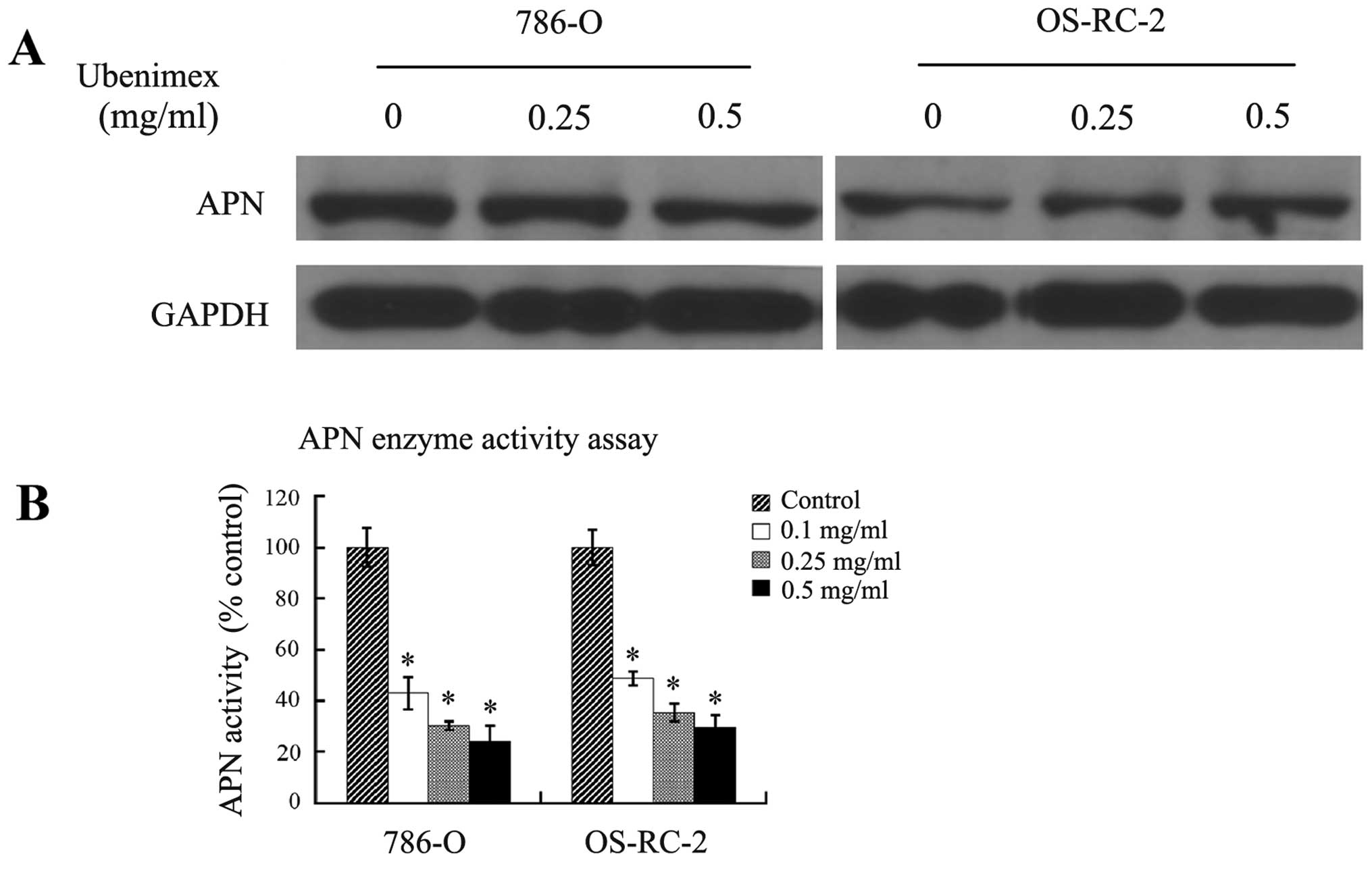

Ubenimex inhibits APN activity in RCC

cells without reducing expression

Ubenimex is known as an inhibitor of APN, which is

identical to the cell surface molecule CD13 (2). To confirm the expression of APN in two

RCC cell lines, 786-O and OS-RC-2, and to evaluate the effects of

ubenimex on APN expression and activity, we performed western

blotting and enzymatic activity assays. Both cell lines expressed

APN, although expression appeared to be consistently higher in the

786-O cells. Furthermore, the expression remained high after a 24-h

treatment with ubenimex (Fig. 1A).

Conversely, APN activity was reduced by ubenimex in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B).

These results verify that APN is expressed in the RCC cells and

suggest that ubenimex targets the activity, but not the expression

of APN.

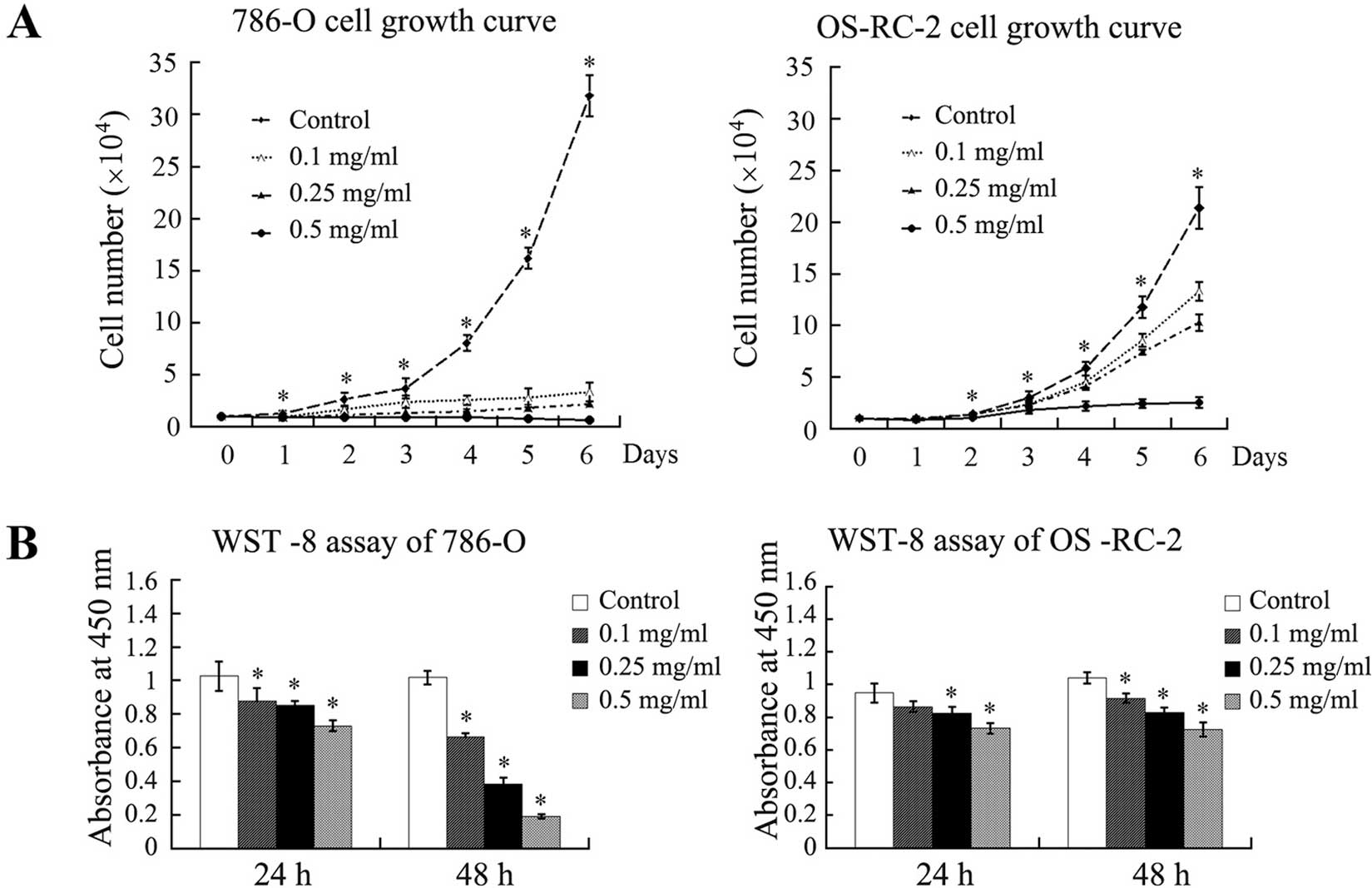

Ubenimex inhibits proliferation,

migration and invasion of the RCC cell lines

To examine the effects of ubenimex on the

proliferation of RCC cells, the 786-O and OS-RC cells were treated

with a range of concentrations of ubenimex and the cell growth was

assessed over a 6-day time course. The cell growth was

significantly decreased for both the cell lines in a

concentration-dependent manner, although the effect was more

obvious in the 786-O cells (Fig.

2A). These results were verified by the WST-8 assay after a 24-

and 48-h exposure to ubenimex (Fig.

2B).

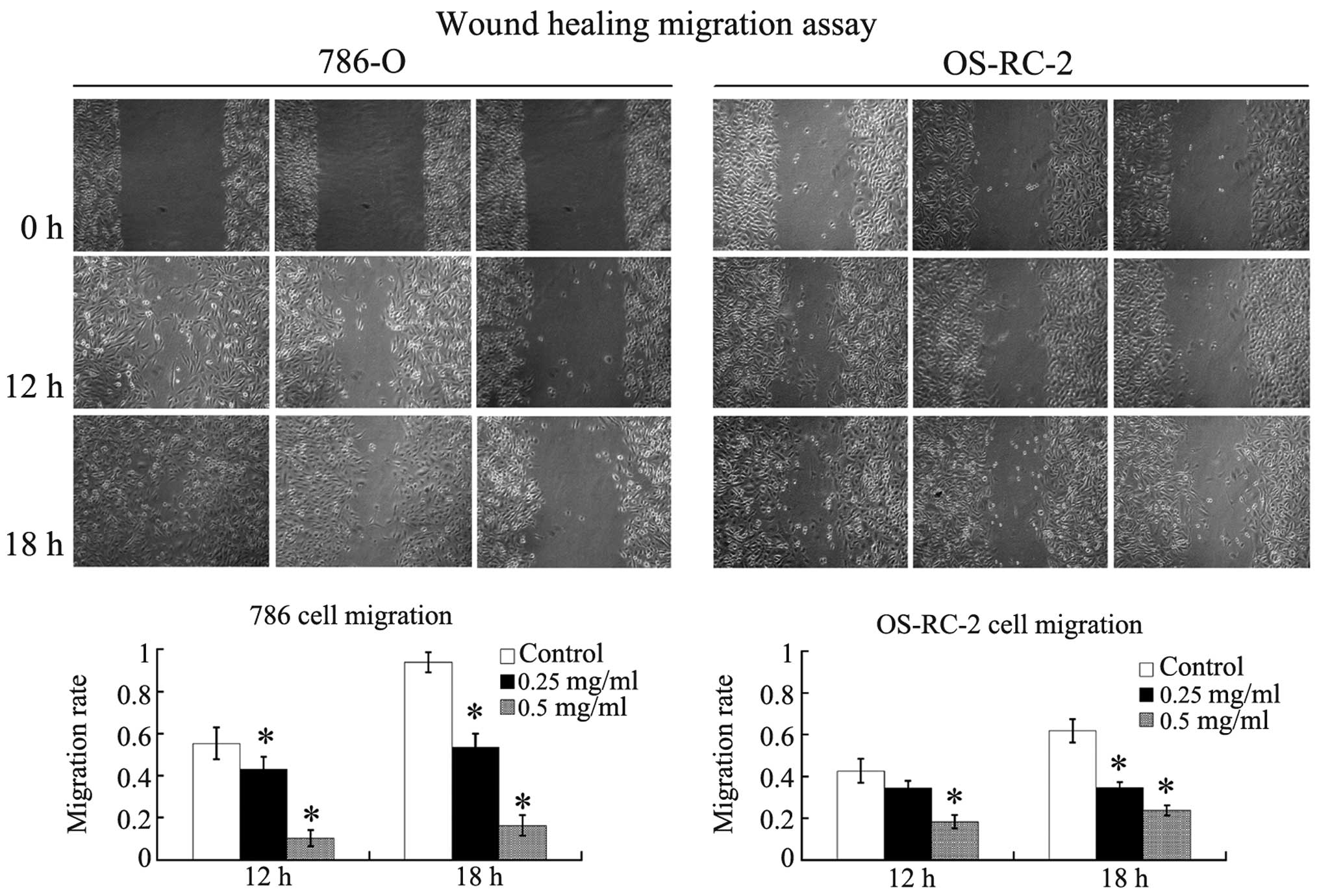

To determine whether ubenimex affects the migratory

ability of RCC cells, we performed scratch wound-healing migration

assays. The migratory abilities of the 786-O and OS-RC-2 cells were

significantly suppressed by ubenimex in a concentration-dependent

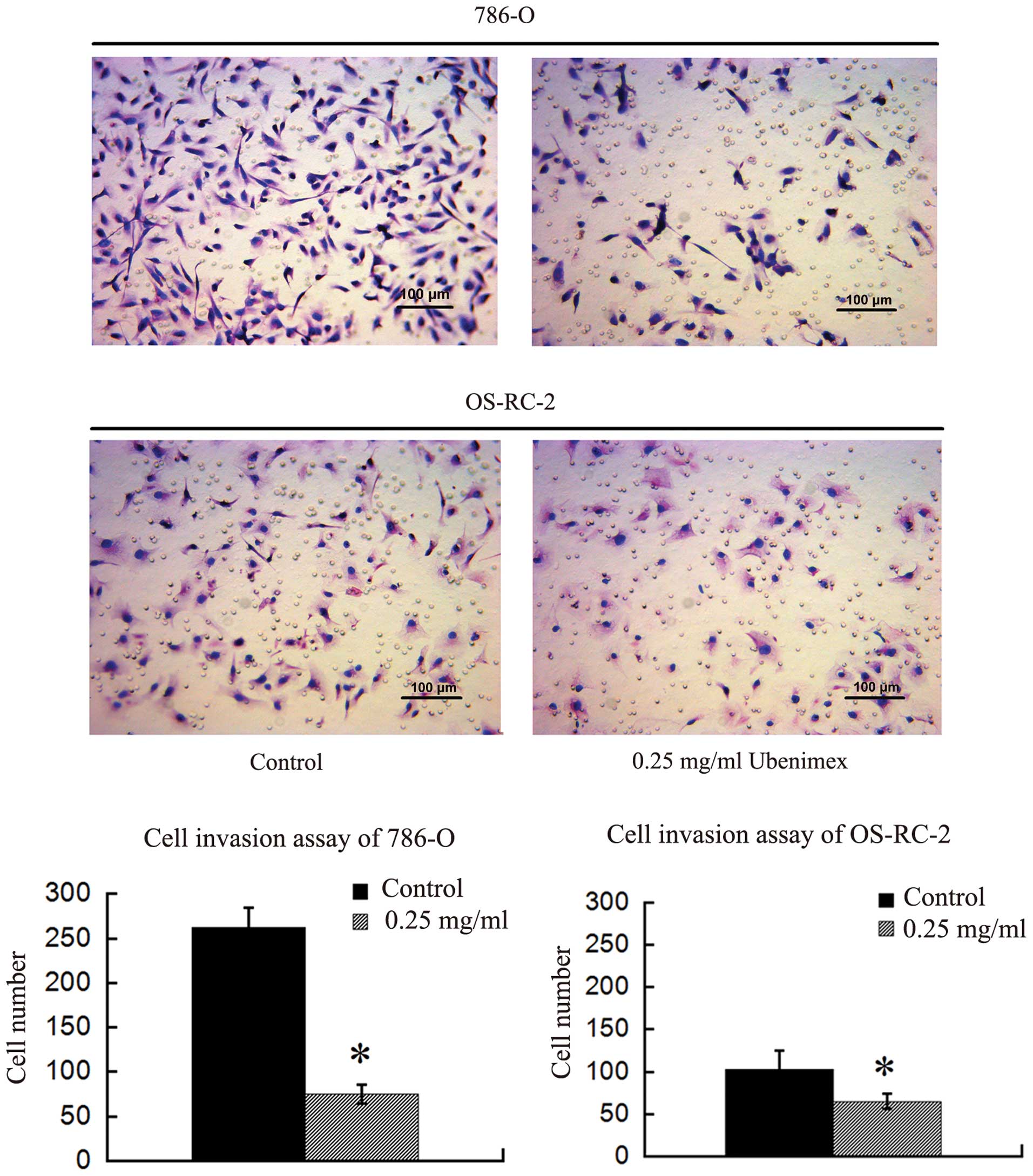

manner after a 12- or 18-h exposure (Fig. 3). We further examined the effect of

ubenimex on the invasion activity of RCC cells using Matrigel

invasion assays. Pretreatment of ubenimex markedly inhibited the

invasive abilities of the 786-O and OS-RC-2 cells, although once

again, the effects appeared more dramatic in the 786-O cells

(Fig. 4). Collectively, these

results suggest that ubenimex inhibits the tumorigenic properties

of RCC cells, including proliferation, migration and invasion of

RCC cells, although the extent of the effect may vary according to

the RCC cell line.

Ubenimex induces autophagic death of RCC

cells

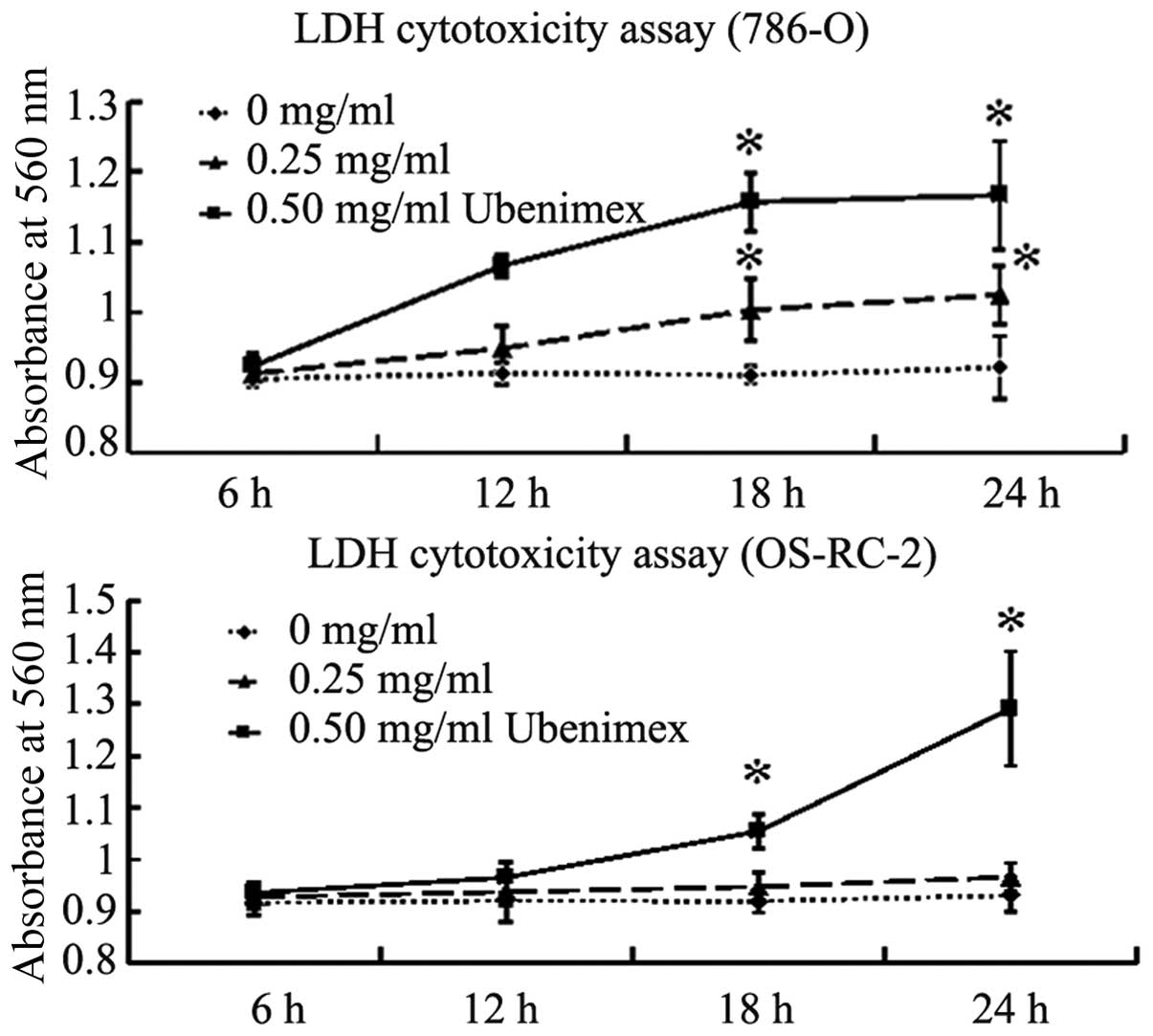

To determine whether ubenimex induces the cell death

of RCC cells, we performed LDH cytotoxicity assays following

ubenimex treatment. The LDH assay determines the extent of cell

death irrespectively of the type of cell death. The mortality of

both the RCC cells was significantly increased after treatment with

0.5 mg/ml ubenimex for 18 or 24 h; the mortality of the 786-O cells

was also significantly increased after treatment with 0.25 mg/ml

ubenimex for 18 or 24 h (Fig.

5).

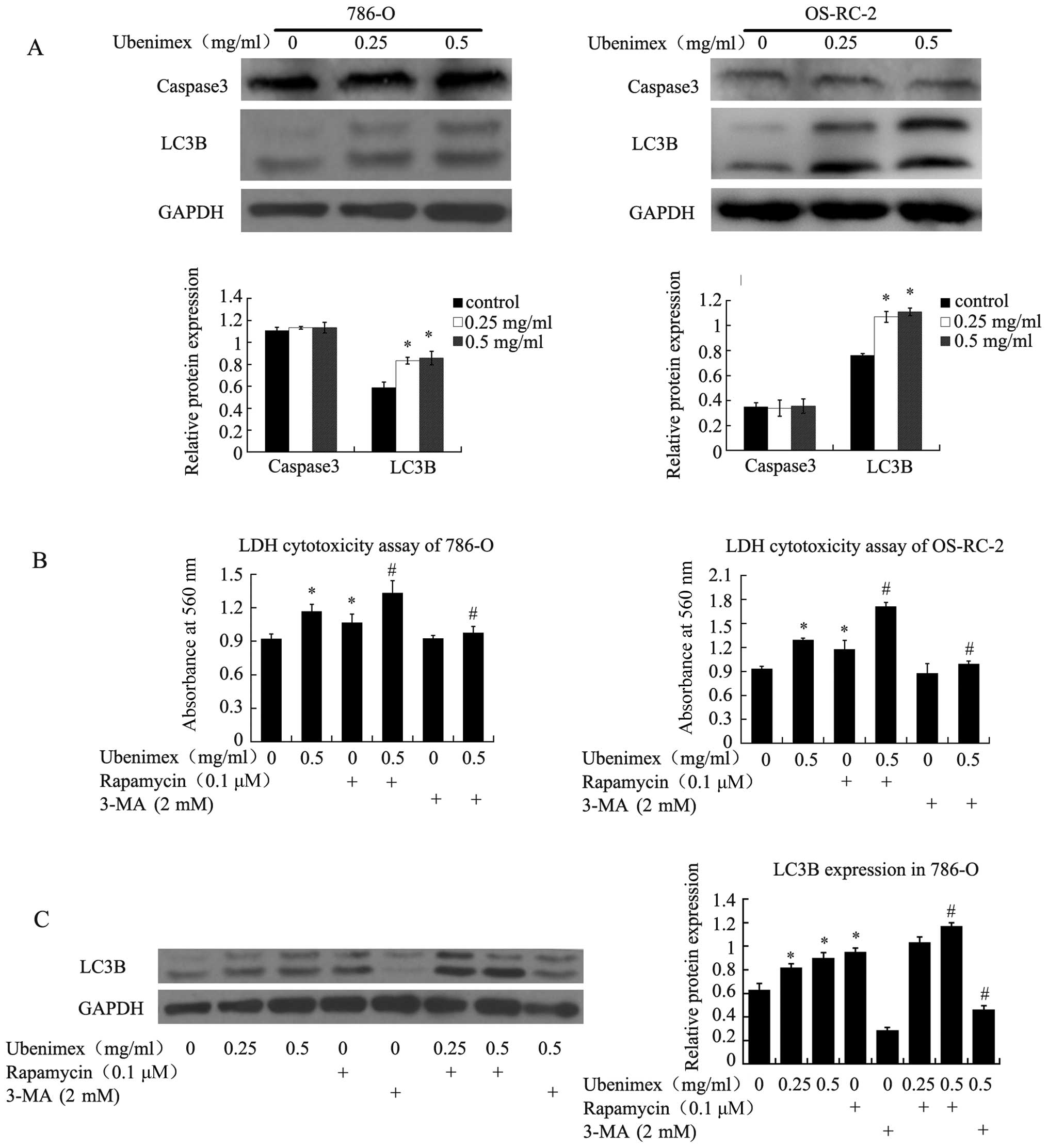

To investigate the mechanism of this effect, we

assessed the levels of an apoptosis marker (Caspase3) and an

autophagy marker (LC-3B). LC-3B expression increased after ubenimex

treatment, while the expression of Caspase3 remained unchanged

(Fig. 6A) These results indicated

that autophagic cell death, rather than apoptotic cell death may be

the predominate mode of ubenimex-induced RCC cell cytotoxicity. To

verify this hypothesis, an LDH cytotoxicity assay was performed

after pretreating the RCC cells with rapamycin (an inducer of

autophagy) or 3-methyladenine (an inhibitor of autophagy).

Rapamycin enhanced the levels of ubenimex-induced cell death while

3-methyladenine reversed the effect in both cell lines (Fig. 6B). Western blotting confirmed the

relationship between ubenimex and autophagy in 786-O cells

(Fig. 6C). These results indicate

that ubenimex promotes significant levels of cell death in RCC

cells and that the death occurs via an autophagic mechanism.

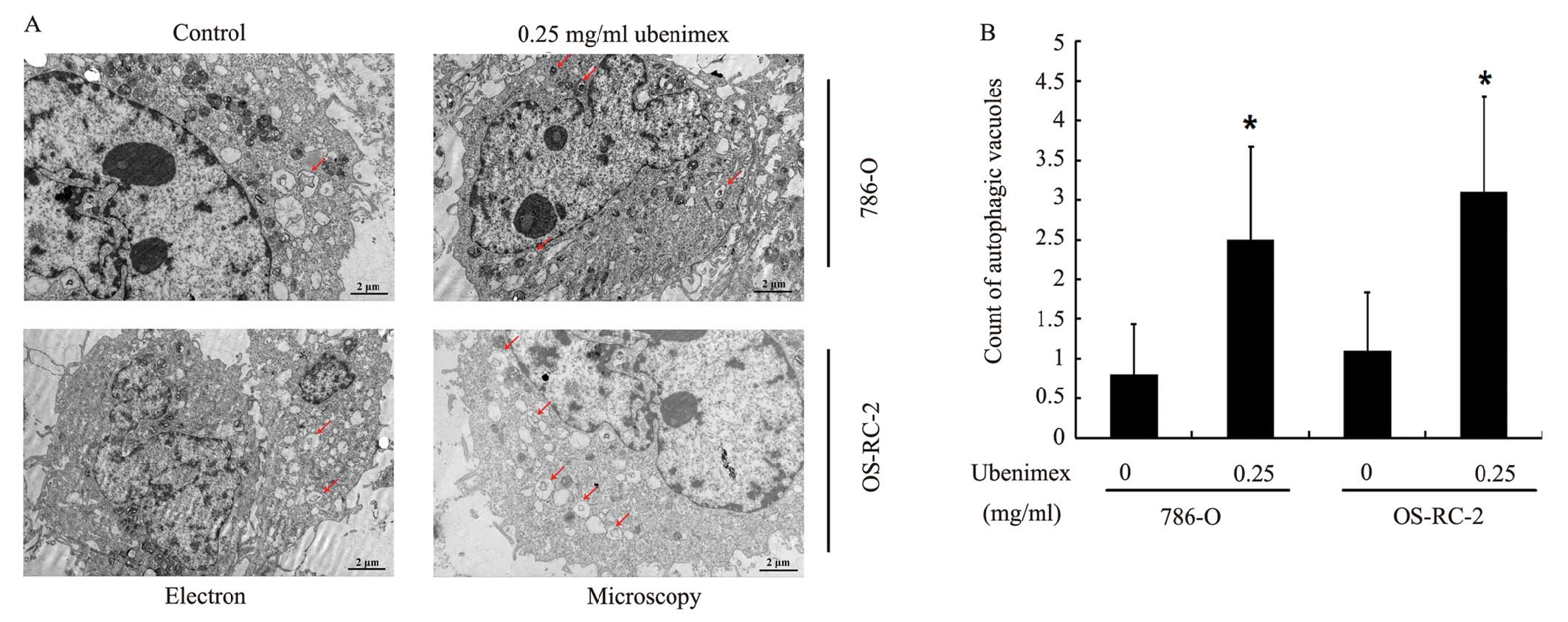

In order to confirm this theory, electron microscopy

was used to visualize the cell morphology after both cell lines

were treated with ubenimex compared to the control cells. Ubenimex

treatment increased the presence of autophagosomes filled with

debris in both the cell lines; only a few vacuoles were observed in

the control cells (Fig. 7A).

Quantification of the autophagosomes indicated higher autophagy

levels after ubenimex treatment (Fig.

7B).

APN is expressed in patient RCC tissues

at reduced levels

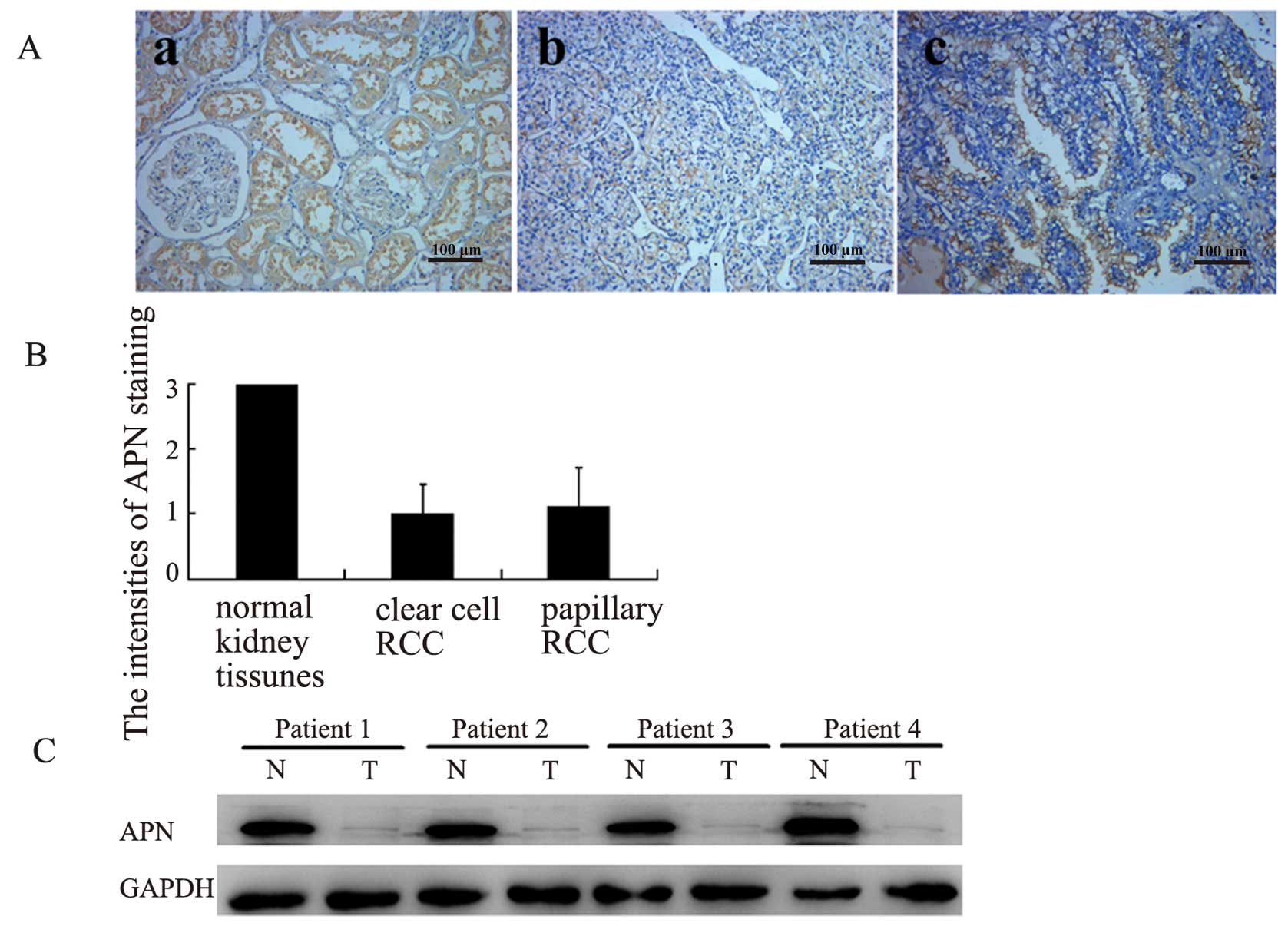

Immunohistochemical analysis showed strong

expression of APN in the epithelial cells of the renal proximal

tubules of the normal kidney tissue. Most of the RCC tumor tissues

(59/76, 77.6%) also showed positive staining, although the staining

was comparably weak (Fig. 8A and

B). Reduced expression of APN in the RCC tissue was verified by

western blotting of 4 representative normal adjacent kidney

tissues/RCC tissue pairs (Fig. 8C).

The intensity of APN was not significantly different between the

clear cells and the papillary RCC and was not associated with tumor

size grade or stage (Table I).

These results suggest that APN was expressed in the RCC, but the

levels of expression was reduced as compared to the normal tissues.

The differential expression of APN may be suggestive of a function

of this protein in RCC. Furthermore, the expression of APN in some

RCC tumors provides a rationale for considering ubenimex for the

treatment of those tumors that express APN, although the extent of

expression may limit the efficacy.

| Table IImmunohistochemistry of APN in RCC

tissue microarray blocks. |

Table I

Immunohistochemistry of APN in RCC

tissue microarray blocks.

| | Intensity of APN

expression | |

|---|

| |

| |

|---|

| No. of patients | − | + | ++ | +++ | P-value |

|---|

| Histological

type |

| Clear cell | 67 | 15 | 37 | 15 | − | |

| Papillary | 9 | 2 | 4 | 3 | − | 0.576 |

| Tumor grade |

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 1 | − | |

| 2 | 54 | 14 | 27 | 13 | − | |

| 3,4 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 4 | − | 0.264 |

| Tumor stage |

| 1 | 40 | 9 | 19 | 10 | − | |

| 2 | 18 | 5 | 11 | 2 | − | |

| 3,4 | 18 | 3 | 11 | 4 | − | 0.565 |

| Tumor diameter

(cm) |

| ≤4 | 21 | 4 | 11 | 6 | − | |

| >4 and ≤7 | 28 | 9 | 14 | 5 | − | |

| >7 |

Discussion

Previous studies indicate that APN plays an

important role in the control of the growth and differentiation of

cancer cells (3). Inhibition of APN

expression or activity reduces the proliferation of various types

of cells (2). Here, we gained

insight into the effect of ubenimex treatment and the role of APN

activity in the growth and development of RCC cells.

Our data demonstrated that treatment of the 786-O

and OS-RC-2 cells with ubenimex had no effect on the APN expression

level, but decreased the APN enzyme activity. We also demonstrated

that ubenimex treatment significantly inhibited the RCC cell

growth, proliferation, migration and invasion, which may explain

its antitumorigenic properties. The effect of ubenimex was more

pronounced in the 786-O cells, which express higher amounts of APN.

These results suggest that the inhibitory effects of ubenimex may

be associated with its ability to block APN enzyme activity.

The role of APN in the cell motility and metastasis

of cancer cells is suggested to involve the degradation of

neuropeptides, cytokines and immunomodulatory peptides, as well as

angiotensins (6). Inhibition of APN

suppresses the progressive potential in many malignant solid tumor

cells (7,14–16).

The present study demonstrated that ubenimex inhibited RCC cell

migration and invasion, which is consistent with the role of APN in

these processes. The invasion activity of the RCC cell line SKRC-1,

which expresses moderate amounts of the APN, may also be suppressed

by ubenimex (17). Thus, these

results suggest that the APN may play a role in the metastasis of

RCC.

We also showed that ubenimex induced a

concentration-dependent cytotoxicity of the RCC cells. Several

studies have demonstrated a function of ubenimex in inducing cancer

cell apoptosis through activating Caspase3 (11,18,19);

however, in the present study, ubenimex had no significant effect

on the Caspase3 expression. Instead, LC-3B, which is a key protein

marker of autophagy-dependent cell death (20), was upregulated after ubenimex

treatment; the cytotoxic effect of ubenimex was attenuated after

blocking autophagy with 3-MA, indicating that ubenimex induces the

autophagic cell death of RCC cells; furthermore, the autophagy

occured after ubenimex treatment in both RCC lines, as evidenced by

electron microscopy. To our knowledge, this is the first

demonstration that ubenimex induces the autophagy in RCC cells.

Autophagy plays a significant role in tumorigenesis and it is the

basis of alternative trials evaluating the effectiveness of other

drug regimes (20–23). In many cases, the expression of

autophagy-related genes in cancer cells can inhibit cell

proliferation (24). Reduced levels

of autophagy liberate cancer cells from suppression and may further

accelerate their proliferation rate (25,26).

Therefore, our data are consistent with the possibility that growth

inhibition by ubenimex may partly be caused by autophagy.

To assess the feasibility of using ubenimex to treat

primary human RCC, we also assessed the APN levels in the RCC

tissues from patients undergoing nephrectomy. Immunohistochemistry

and western blotting showed that APN was expressed in most RCC

tumors, but at lower levels than in the surrounding tissues.

Although we did not observe any correlations between APN expression

and the clinicopathological parameters, downregulation of APN in

the tumor tissues compared with normal kidney tissues may suggest a

potential role for APN in RCC development. Studies concerning

several other cancer types indicate that APN functions in a highly

cell type- and context-specific manner: high expression is an

adverse prognostic factor for non-small cell lung cancer,

pancreatic and colon cancer (27–29),

but low APN expression is associated with aggressive disease in

meningioma, gastric cancer and prostate cancer (17,30,31).

Further studies are needed to determine the physiological effects

of APN down-regulation in RCC and the potential efficacy of the

ubenimex in treating RCC.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

ubenimex inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of RCC

cells. Ubenimex may induce autophagy, which may partly explain its

effect on growth arrest and cell death. Further studies on APN

function and the effect of ubenimex treatment in RCC will provide

insight into the mode of action of ubenimex in RCC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Science and

Technology Development Plan Project of Shandong Province, P.R.

China.

References

|

1

|

Su D, Stamatakis L, Singer EA and

Srinivasan R: Renal cell carcinoma: molecular biology and targeted

therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 26:321–327. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hitzerd SM, Verbrugge SE, Ossenkoppele G,

Jansen G and Peters GJ: Positioning of aminopeptidase inhibitors in

next generation cancer therapy. Amino Acids. 46:793–808. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wickström M, Larsson R, Nygren P and

Gullbo J: Aminopeptidase N (CD13) as a target for cancer

chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 102:501–508. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ishii K, Usui S, Sugimura Y, Yoshida S,

Hioki T, Tatematsu M, Yamamoto H and Hirano K: Aminopeptidase N

regulated by zinc in human prostate participates in tumor cell

invasion. Int J Cancer. 92:49–54. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fontijn D, Duyndam MC, van Berkel MP,

Yuana Y, Shapiro LH, Pinedo HM, Broxterman HJ and Boven E:

CD13/Aminopeptidase N overexpression by basic fibroblast growth

factor mediates enhanced invasiveness of 1F6 human melanoma cells.

Br J Cancer. 94:1627–1636. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mina-Osorio P: The moonlighting enzyme

CD13: old and new functions to target. Trends Mol Med. 14:361–371.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Terauchi M, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Ino K,

Nawa A, Mizutani S and Kikkawa F: Inhibition of APN/CD13 leads to

suppressed progressive potential in ovarian carcinoma cells. BMC

Cancer. 7:1402007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Martin-Padura I, Marighetti P, Agliano A,

Colombo F, Larzabal L, Redrado M, Bleau AM, Prior C, Bertolini F

and Calvo A: Residual dormant cancer stem-cell foci are responsible

for tumor relapse after antiangiogenic metronomic therapy in

hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts. Lab Invest. 92:952–966. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ichinose Y, Genka K, Koike T, Kato H,

Watanabe Y, Mori T, Iioka S, Sakuma A and Ohta M: NK421 Lung Cancer

Surgery Group: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of

bestatin in patients with resected stage I squamous-cell lung

carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 95:605–610. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wakita A, Ohtake S, Takada S, Yagasaki F,

Komatsu H, Miyazaki Y, Kubo K, Kimura Y, Takeshita A, Adachi Y,

Kiyoi H, Yamaguchi T, Yoshida M, Ohnishi K, Miyawaki S, Naoe T,

Ueda R and Ohno R: Randomized comparison of fixed-schedule versus

response-oriented individualized induction therapy and use of

ubenimex during and after consolidation therapy for elderly

patients with acute myeloid leukemia: the JALSG GML200 Study. Int J

Hematol. 96:84–93. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tsukamoto H, Shibata K, Kajiyama H,

Terauchi M, Nawa A and Kikkawa F: Aminopeptidase N (APN)/CD13

inhibitor, Ubenimex, enhances radiation sensitivity in human

cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 8:742008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xu JW, Li CG, Huang XE, Li Y and Huo JG:

Ubenimex capsule improves general performance and chemotherapy

related toxicity in advanced gastric cancer cases. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 12:985–987. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sugano O, Muto A, Kato M and Ono K: A case

of renal cell carcinoma with lymph node metastasis keeping

remission for five years by adjuvant immunotherapy with ubenimex.

Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 30:1519–1522. 2003.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Saitoh Y, Koizumi K, Minami T, Sekine K,

Sakurai H and Saiki I: A derivative of aminopeptidase inhibitor

(BE15) has a dual inhibitory effect of invasion and motility on

tumor and endothelial cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 29:709–712. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mawrin C, Wolke C, Haase D, Krüger S,

Firsching R, Keilhoff G, Paulus W, Gutmann DH, Lal A and Lendeckel

U: Reduced activity of CD13/aminopeptidase N (APN) in aggressive

meningiomas is associated with increased levels of SPARC. Brain

Pathol. 20:200–210. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Inagaki Y, Tang W, Zhang L, Du G, Xu W and

Kokudo N: Novel aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) inhibitor 24F can

suppress invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells as well as

angiogenesis. Biosci Trends. 4:56–60. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ishii K, Usui S, Sugimura Y, Yamamoto H,

Yoshikawa K and Hirano K: Inhibition of aminopeptidase N (AP-N) and

urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) by zinc suppresses the

invasion activity in human urological cancer cells. Biol Pharm

Bull. 24:226–230. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sekine K, Fujii H and Abe F: Induction of

apoptosis by bestatin (ubenimex) in human leukemic cell lines.

Leukemia. 13:729–734. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sekine K, Fujii H, Abe F and Nishikawa K:

Augmentation of death ligand-induced apoptosis by aminopeptidase

inhibitors in human solid tumor cell lines. Int J Cancer.

94:485–491. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Eum KH and Lee M: Crosstalk between

autophagy and apoptosis in the regulation of paclitaxel-induced

cell death in v-Ha-ras-transformed fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem.

348:61–68. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Natsumeda M, Aoki H, Miyahara H, Yajima N,

Uzuka T, Toyoshima Y, Kakita A, Takahashi H and Fujii Y: Induction

of autophagy in temozolomide treated malignant gliomas.

Neuropathology. 31:486–493. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Evangelisti C, Ricci F, Tazzari P,

Tabellini G, Battistelli M, Falcieri E, Chiarini F, Bortul R,

Melchionda F, Pagliaro P, Pession A, McCubrey JA and Martelli AM:

Targeted inhibition of mTORC1 and mTORC2 by active-site mTOR

inhibitors has cytotoxic effects in T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Leukemia. 25:781–791. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Crowley LC, Elzinga BM, O’Sullivan GC and

McKenna SL: Autophagy induction by Bcr-Abl-expressing cells

facilitates their recovery from a targeted or nontargeted

treatment. Am J Hematol. 86:38–47. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K,

Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H and Levine B: Induction of autophagy and

inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 402:672–676. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM,

Bray K, Degenhardt K, Chen G, Jin S and White E: Autophagy

suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability.

Genes Dev. 21:1367–1381. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Karantza-Wadsworth V, Patel S, Kravchuk O,

Chen G, Mathew R, Jin S and White E: Autophagy mitigates metabolic

stress and genome damage in mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev.

21:1621–1635. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hashida H, Takabayashi A, Kanai M, Adachi

M, Kondo K, Kohno N, Yamaoka Y and Miyake M: Aminopeptidase N is

involved in cell motility and angiogenesis: its clinical

significance in human colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 122:376–386.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ikeda N, Nakajima Y, Tokuhara T, Hattori

N, Sho M, Kanehiro H and Miyake M: Clinical significance of

aminopeptidase N/CD13 expression in human pancreatic carcinoma.

Clin Cancer Res. 9:1503–1508. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tokuhara T, Hattori N, Ishida H, Hirai T,

Higashiyama M, Kodama K and Miyake M: Clinical significance of

aminopeptidase N in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

12:3971–3978. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kawamura J, Shimada Y, Kitaichi H, Komoto

I, Hashimoto Y, Kaganoi J, Miyake M, Yamasaki S, Kondo K and

Imamura M: Clinicopathological significance of aminopeptidase

N/CD13 expression in human gastric carcinoma.

Hepatogastroenterology. 54:36–40. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sørensen KD, Abildgaard MO, Haldrup C,

Ulhøi BP, Kristensen H, Strand S, Parker C, Høyer S, Borre M and

Ørntoft TF: Prognostic significance of aberrantly silenced ANPEP

expression in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 108:420–428. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|