Introduction

Each year, more than 100,000 women die of ovarian

cancer worldwide (1). Epithelial

ovarian cancer (EOC) accounts for the majority of all ovarian

malignancies and is one of the most lethal among gynecologic

malignancies among women. In many cases, the diagnosis is delayed

due to its asymptomatic nature, and, as a consequence,

approximately two-thirds of patients with EOC have already

developed peritoneal carcinomatosis (2,3). The

prognosis of EOC patients is closely related to the stage at

diagnosis (4,5).

Most ovarian cancer patients are managed with

surgical resection, followed by systemic chemotherapies. Despite

recent advances in therapeutic agents, such as platinum-taxane

combination chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rate is still less

than 40% (6). EOC shows an

unfavorable oncologic outcome, based on its asymptomatic features

at an earlier clinical stage, and numerous intraperitoneal and/or

distant metastases. Despite the relatively high susceptibility of

EOC to paclitaxel plus platinum compounds, which are first-line

chemotherapeutic agents against EOC, the intrinsic or acquired

resistance of tumor cells to these chemotherapies makes the

treatment of EOC difficult. In order to overcome chemo-resistance,

various additional molecular-targeting therapies combined with

conventional anti-neoplastic agents have been developed. High-grade

serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), which is observed much more

frequently at an advanced stage, comprises approximately 60% of all

histological subtypes of EOC. Recent studies have revealed that

most cases of HGSOC carry TP53 mutations, in contrast to other

types of EOC, which have a much lower incidence of TP53 mutations

(7–9). A recent study using high-throughput

sequencing technology revealed that TP53 mutations occurred in 96%

of 316 HGSOC samples (10). This

suggests that somatic mutation of TP53 is a nearly universal event

in HGSOC.

TP53 is located on chromosome 17p and encodes the

p53 protein. Wild-type p53 functions predominately as a

transcriptional factor, with a potent tumor-suppressive function

via its multiple activities, including induction of cell cycle

arrest, apoptosis, differentiation and senescence (11). Recent studies have shown that

missense TP53 mutations not only eliminate their own

tumor-suppressive function, but also gain oncogenic properties that

promote tumor growth, termed gain-of-function (GOF) (12-14).

Furthermore, TP53 mutations may be associated with poor prognosis

and malignant phenotypes in several types of cancers, including EOC

(15–19). Considering the universality of the

TP53 mutation in EOC, several novel drugs restoring the p53 pathway

have been widely investigated to be utilized in cancer therapy.

PRIMA-1 (p53 reactivation and induction of massive

apoptosis) and its methylated form PRIMA-1MET are small

molecules that can convert mutant p53 to an active conformation,

which restores wild-type functions of p53 in several types of

cancers, such as breast, neck and thyroid cancer and melanoma

(20–23). PRIMA-1MET is one of the

most promising drugs for clinical use to restore wild-type

functions to mutant p53 (24).

Although PRIMA-1MET is the first compound of such drugs

evaluated in clinical trials, the antitumor effects of

PRIMA-1MET on EOC remain unclear.

In our present study, we investigated whether

PRIMA-1MET induces growth suppression and apoptosis in

EOC cells. Using EOC cells with either wild-type or mutant p53, and

with either chemo-sensitivity or chemo-resistance, we demonstrated

that PRIMA-1MET was able to effectively induce cell

death. Therefore, PRIMA-1MET can be a promising

therapeutic strategy to induce cytotoxic effects and reactivate the

p53 pathway in EOC, particularly in HGSOC.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human EOC lines, A2780, OVCAR-3, ES-2, SKOV-3,

CaOV-3, TOV21G and OV-90, were obtained from the American Type

Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). NOS2 and NOS3 cell

lines derived from serous EOC were previously established in our

institute (25). The NOS2CR and

NOS2TR cells with chronic resistance to cisplatin and paclitaxel

were previously established from the parental NOS2 cells in our

institute (26). Furthermore, we

recently established another two chronic

cisplatin/paclitaxel-resistant cell lines from the parental NOS3

cells: NOS3CR (cisplatin) and NOS3TR (paclitaxel). All EOC cell

lines were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640

medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS),

streptomycin (100 µg/ml), and penicillin (100 U/ml).

PRIMA-1MET was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc. PRIMA-1MET was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

to create a 50-mmol/l stock solution and stored at −20°C.

Antibodies to p53 (610184) were purchased from BD Pharmingen.

Antibodies to cleaved-PARP, PARP and β-actin were purchased from

Cell Signaling Technology.

Direct sequencing of TP53 mutations

Genomic DNA was extracted from the NOS2 and NOS3

cells using the Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI,

USA). The exons and flanking introns of TP53 were amplified by

polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The primers used are shown in

Table I. The resulting PCR products

were sequenced and the mutation status was confirmed.

| Table IThe specific primers used for direct

sequencing of the TP53 gene. |

Table I

The specific primers used for direct

sequencing of the TP53 gene.

| Primer | Sequence | Length (bp) |

|---|

| p53 | | |

| Exon 2–4 | F:

GTGTCTCATGCTGGATCCCCACT | 23 |

| R:

GGATACGGCCAGGCATTGAAGT | 22 |

| Exon 5–6 | F:

TGCAGGAGGTGCTTACGCATGT | 22 |

| R:

CCTTAACCCCTCCTCCCAGAGAC | 23 |

| Exon 7–9 | F:

ACAGGTCTCCCCAAGGCGCACT | 22 |

| R:

TTGAGGCATCACTGCCCCCTGAT | 23 |

| Exon 10 | F:

GTCAGCTGTATAGGTACTTGAAGTGCAG | 28 |

| R:

GCTCTGGGCTGGGAGTTGCG | 20 |

| Exon 11 | F:

CCTTAGGCCCTTCAAAGCATTGGTCA | 26 |

| R:

GTGCTTCTGACGCACACCTATTGCAAG | 27 |

RNA extraction

RNA extraction from the cells was undertaken using

the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit according to the manufacturer's

protocols. The cells were lysed in 250 µl of buffer RLT and

filtered through the filtration spin column. The samples were

applied to the RNeasy Mini spin column. Total RNA bound to the

membrane and contaminants were removed by washing consecutively

with buffers RW1 and RPE. RNA was eluted in RNase-free water.

Extracted RNA was immediately stored at −80°C. The RNA

concentration was determined with the NanoDrop 1000

spectrophotometer.

Reverse transcription

To obtain complementary DNA (cDNA), 1 µg of

RNA and 0.2 µg of random primers (Promega) were used. After

incubation at 72°C for 4 min, the mixture of RNA and random primers

were placed on ice for 4 min. M-MLV RT 1X reaction buffer, M-MLV

Reverse Transcriptase RNase Minus, and 10 mM dNTP (Promega) were

added to the mixture and then incubated at 42°C for 90 min,

followed by 70°C for 15 min. cDNA was stored at −20°C.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on the

Takara PCR thermal cycler using the SYBR Green detection system

(Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Cycling conditions consisted of a 3-min hot

start at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10

sec, annealing at 58–60°C for 10 sec, extension at 72°C for 10 sec,

and then a final inactivation at 95°C for 10 sec. Dissociation

curve analyses were carried out at the end of the cycling to

confirm that one specific product was measured in each reaction.

Relative quantification was performed using the ΔΔCT method

(27). Expression normalization was

conducted by the expression of GAPDH, a housekeeping gene shown to

have stable expression in cancer cell lines (28). The specific primers for each gene

are shown in Table II. All

experiments were performed in triplicate.

| Table IIThe specific primers used for

quantitative real-time RT-PCR. |

Table II

The specific primers used for

quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

| Primer | Sequence | Length (bp) |

|---|

| PRX3 | F:

GACGCTCAAATGCTTGATGA | 20 |

| R:

GATTTCCCGAGACTACGGTG | 20 |

| GPX1 | F:

AAGAGCATGAAGTTGGGCTC | 20 |

| R:

CAACCAGTTTGGGCATCAG | 19 |

| GAPDH | F:

TTGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTCA | 22 |

| R:

TGTCATCATATTTGGCAGGTT | 21 |

Protein extraction and western blot

analysis

Cultured ovarian cancer cells were washed with PBS

and lysed in RIPA buffer (Millipore). The cells were scrapped into

lysis buffer, centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min, and then

diluted in 2X sample buffer [125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 10%

glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, and 10% 2-mercaptoethanol]. Equal

amounts of protein (10 µg) were mixed with the 2X sample

buffer and were boiled at 95°C for 5 min. The samples were loaded

and separated by 7.5–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(PAGE) with running buffer. The separated proteins were transferred

to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were

blocked with 1% skim milk, incubated with each primary antibody

overnight at 4°C, washed with TBS-T buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4,

150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated with the secondary

antibodies. The proteins were visualized using enhanced

chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala,

Sweden).

Cell viability assay

The effect of PRIMA-1MET on the viability

of human EOC cells was evaluated with the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent

Cell Viability Assay (Promega), which quantifies living cells by

ATP signal intensity. The luminescent signal was determined with a

luminometer. Cells were seeded in triplicate in 96-well plates at a

density of 2,000 cells/well. After a 24-h culture, the cells were

treated with various concentrations of PRIMA-1MET, and

then incubated for 24–72 h. Control cells were treated with the

same concentration of DMSO as that of the

PRIMA-1MET-treated cells.

Detection of apoptosis by staining with

Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide

Cells (2×105) were cultured in 6-well

plates for 24 h before treatment with DMSO (control) or an

appropriate concentration of PRIMA-1MET for 24 h. The

cells were trypsinized, washed once with PBS, and then stained with

Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) to determine the

early/late apoptotic cell population (MBL, Japan).

Results

Protein expression of p53 and the TP53

status in EOC cells

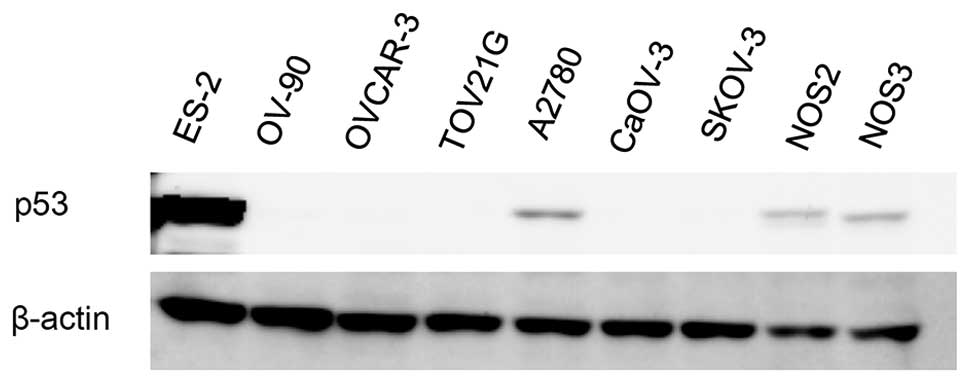

Firstly, we evaluated the levels of p53 protein

expression in the EOC cells by western immunoblot analysis. The

mutation status of TP53 in the EOC cells was acquired from previous

studies. The mutation status of TP53 of NOS2 and NOS3 cells was

evaluated by direct sequencing. The TP53 status of EOC cells is

shown in Table III. The protein

expression of p53 is shown in Fig.

1. EOC cells with wild-type p53, A2780 and NOS2, displayed a

basal expression of p53 to some extent. On the contrary, we could

not detect the protein expression of p53 in the EOC cells with

mutant p53, except for the ES-2 cells. This result demonstrates

that EOC cells bearing mutant p53 do not always express a higher

level of p53 than those bearing wild-type p53.

| Table IIITP53 status of the EOC cell

lines. |

Table III

TP53 status of the EOC cell

lines.

| Cancer cell

lines | p53 status |

|---|

| ES-2 | S241F |

| OV-90 | S215R |

| OVCAR-3 | R248Q |

| TOV21G | Wild-type |

| A2780 | Wild-type |

| CaOV-3 | Q136Term |

| SKOV-3 | Null |

| NOS2 | Wild-type |

| NOS3 | L257P |

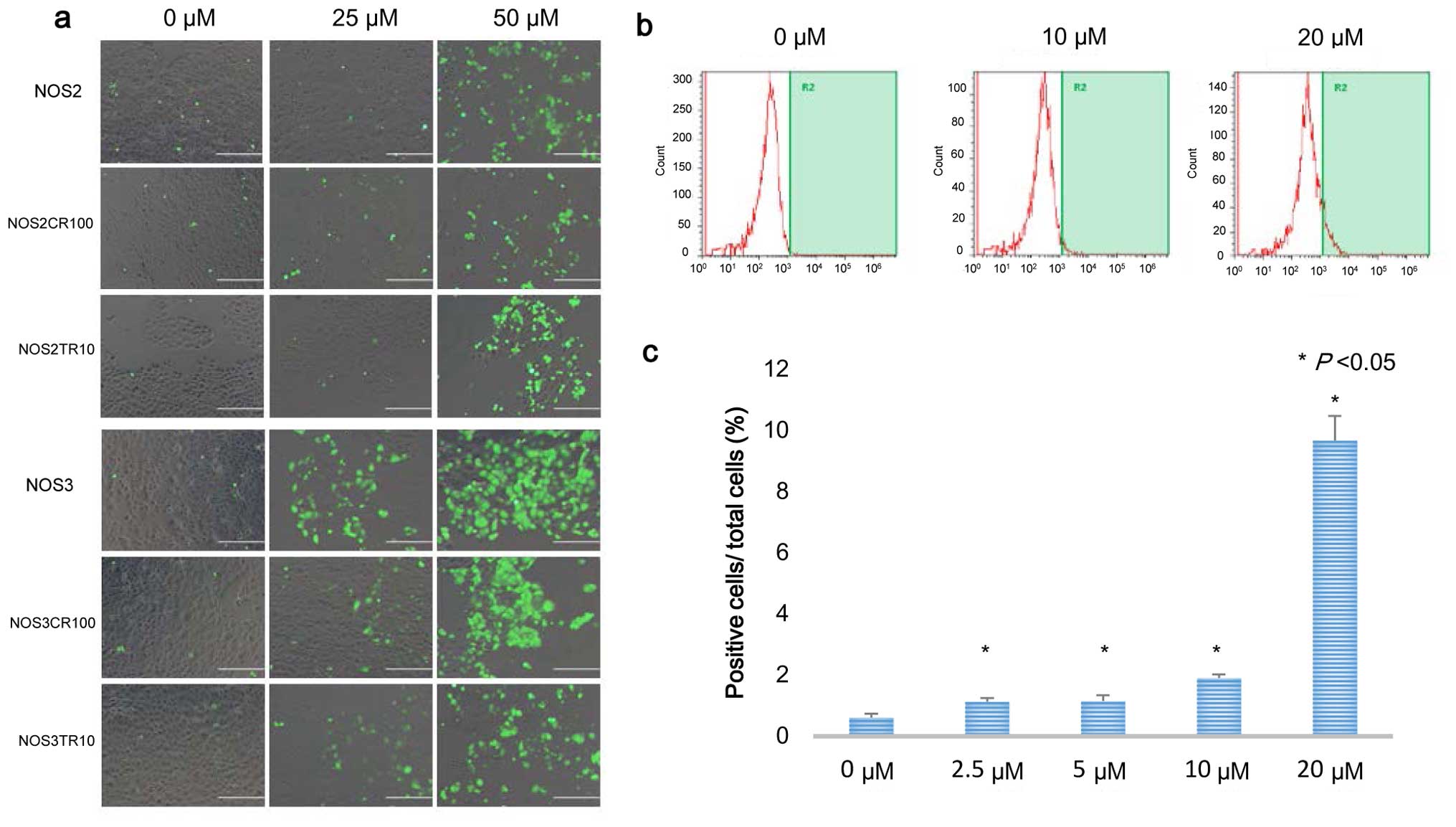

The effect of PRIMA-1MET on

cell death and apoptotic morphological changes in EOC cells

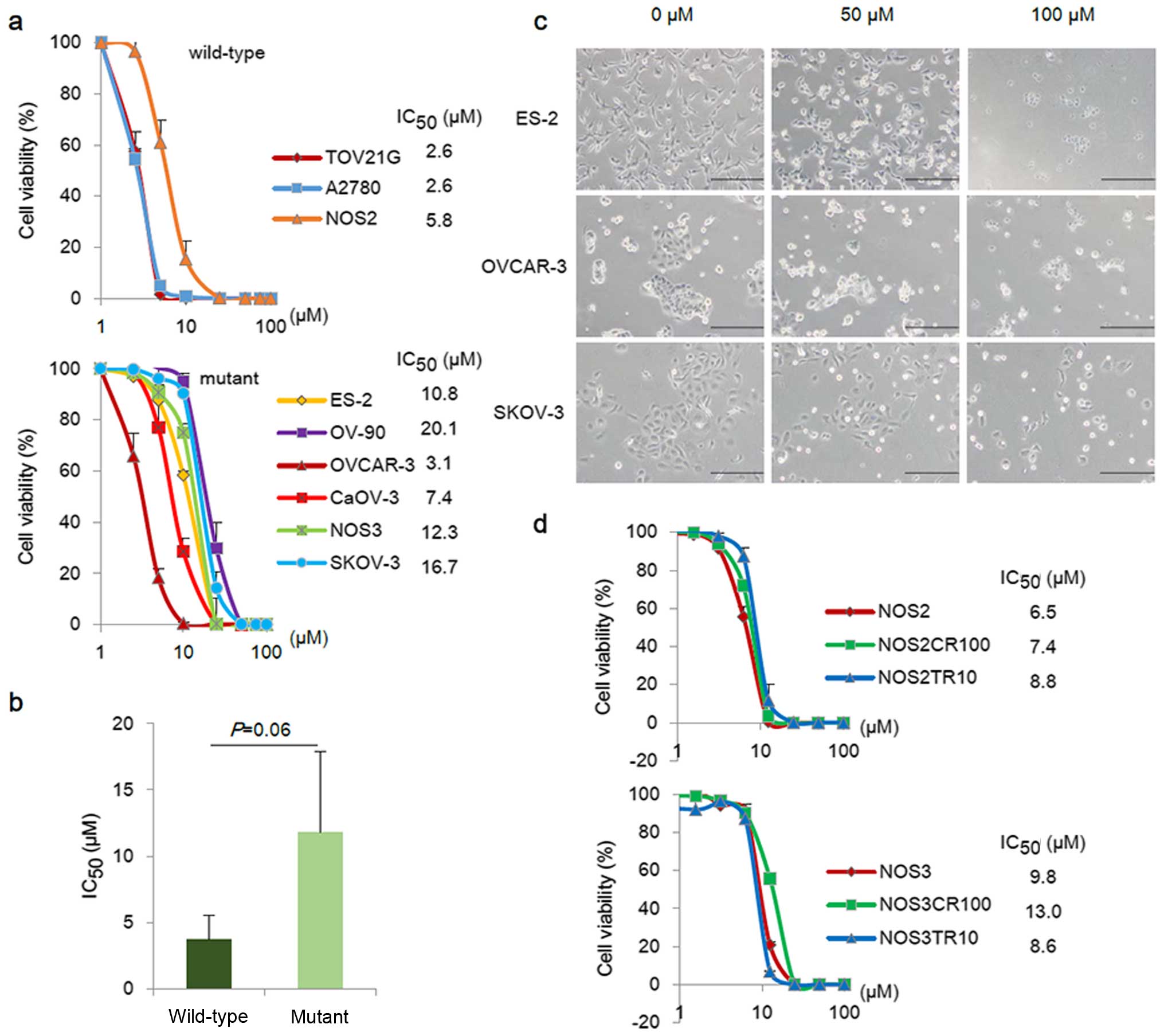

To assess the effect of PRIMA-1MET on EOC

cells, the anti-proliferative effects of various concentrations of

PRIMA-1MET (approximately 0–100 µM) were

determined in a total of 9 EOC cell lines: TOV21G, A2780, ES-2,

OV-90, OVCAR-3, CaOV-3, SKOV-3, NOS2 and NOS3. Fig. 2a shows the cell viability of

wild-type p53 cell lines (TOV21G, A2780, and NOS2) and mutant p53

cell lines (ES-2, OV-90, OVCAR-3, CaOV-3, NOS3 and SKOV-3) treated

with PRIMA-1MET for 48 h. PRIMA-1MET reduced

cell viability after 48 h in all EOC cell lines in a dose-dependent

manner. The IC50 values of PRIMA-1MET ranged

from 2.6 to 20.1 µM, which were independent of the mutation

status of TP53 (Fig. 2b).

Furthermore, PRIMA-1MET treatment induced a

morphological change which was consistent with the apoptotic change

within 6–24 h (Fig. 2c). We next

investigated whether PRIMA-1MET had sufficient effects

on cisplatin- and paclitaxel-resistant cell lines, which were

previously developed from the parental NOS2 and NOS3 cells (NOS2CR,

NOS2TR, NOS3CR, and NO3TR). Dose-responsive cell viability assays

with PRIMA-1MET were performed to evaluate the

sensitivities of the chemo-resistant cells. As shown in Fig. 2d, PRIMA-1MET displayed

anti-proliferative effects on both the parental and chemo-resistant

cells. The IC50 values of the NOS2, NOS2CR, and NOS2TR

cells were 6.5, 7.4, and 8.8 µM, respectively. The

IC50 value of the NOS3CR cells was slightly higher than

the values of the NOS3 and NOS3TR cells (not significant).

PRIMA-1MET had sufficient growth-suppressing activity

regardless of the mutation status of the TP53 and the

chemo-sensitivity in the EOC cells.

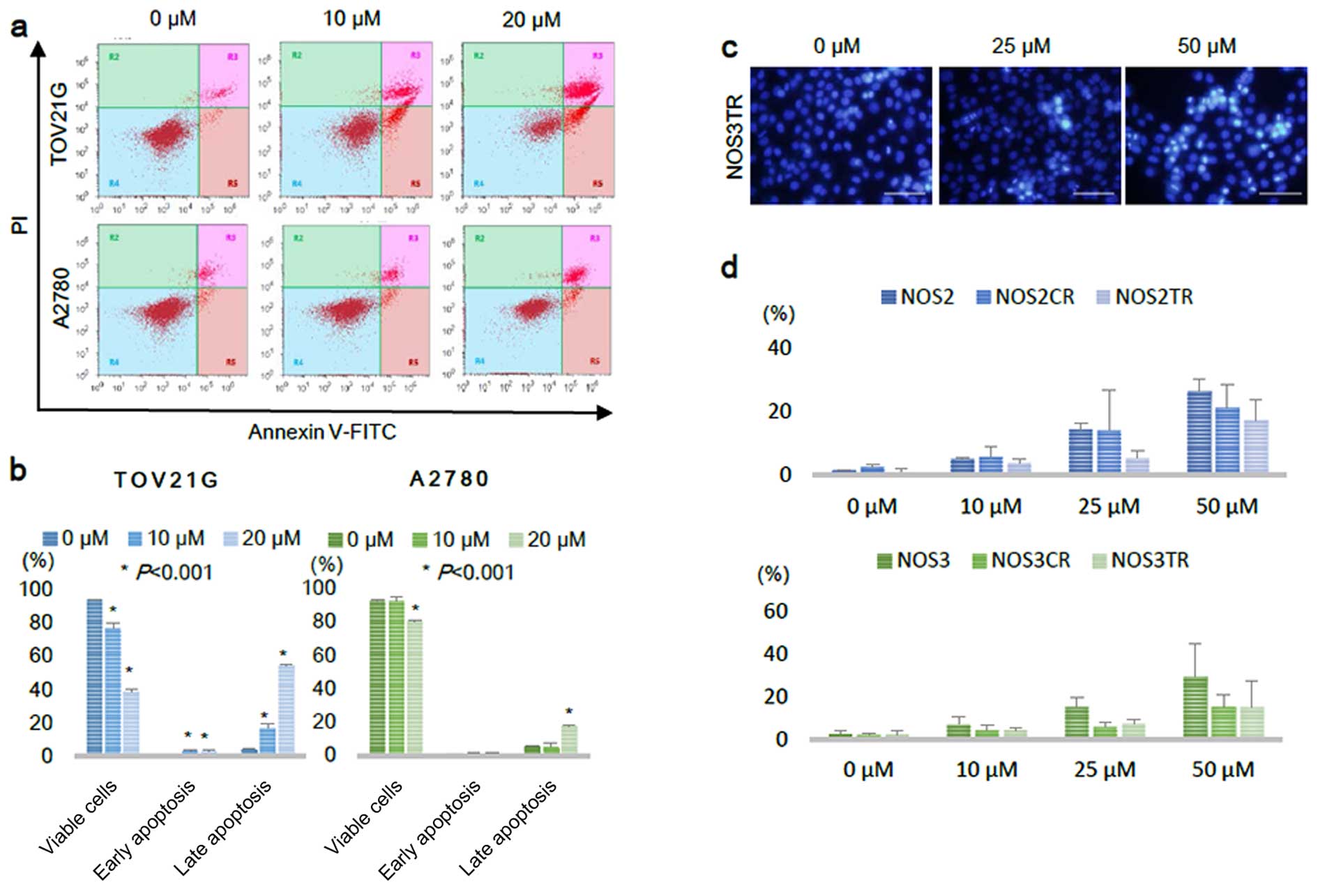

PRIMA-1MET induces apoptosis

in a dose-dependent manner in the EOC cells

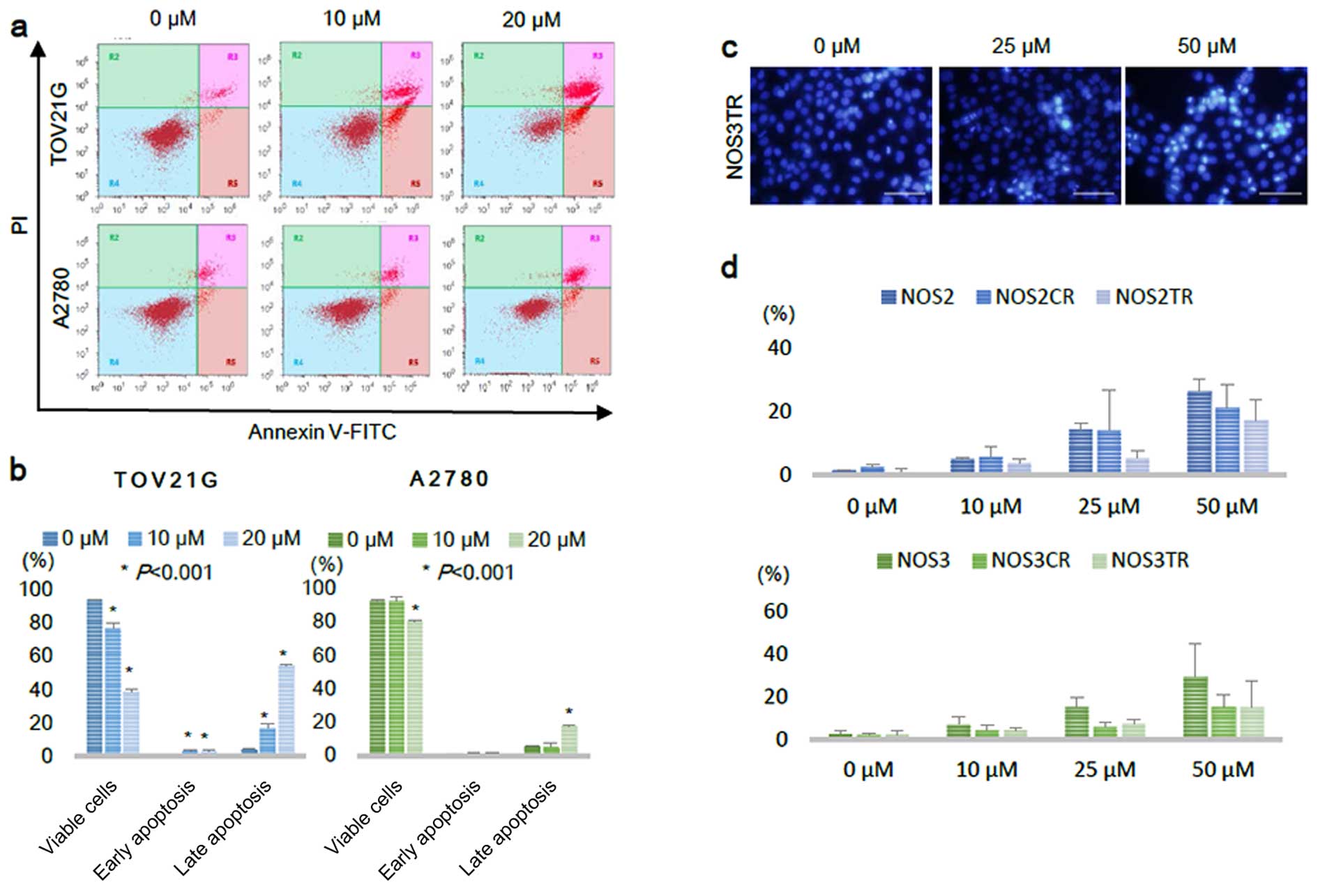

We next performed an Annexin V-FITC/PI staining

assay to investigate whether PRIMA-1MET actually induced

apoptosis in the EOC cells. Treatment with PRIMA-1MET

for 16 h against EOC cells, TOV21G and A2780, increased the

fraction of early and late apoptotic cells (Fig. 3a). In the TOV21G cells, the

fractions of early and late apoptotic cells were significantly

increased from 1.1 and 4.3% following control vehicle treatment to

3.3 and 54.5% following 20 µM of PRIMA-1MET

treatment, respectively (Fig. 3b).

In the A2780 cells, the proportion of late apoptotic cells was

significantly elevated from 5.3% following control vehicle

treatment to 17.6% following 20 µM treatment (Fig. 3b). To determine whether

PRIMA-1MET also induced apoptosis in chemo-resistant EOC

cells, we evaluated cell apoptosis in another manner using

fluorescence microscopy. The cells after a 24-h treatment with

PRIMA-1MET were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained

with Hoechst 33342, and then we identified apoptosis with

fluorescence microscopy. The cells which had fragmented or

condensed nuclei were defined as undergoing apoptosis and counted

manually with fluorescence microscopy (29). The representative images of

condensed nuclei are shown in Fig.

3c. PRIMA-1MET treatment significantly increased the

fractions of apoptotic cells with fragmented or condensed nuclei in

both parental cells and their chemo-resistant cells in a

dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3d).

These results indicate that PRIMA-1MET induces apoptotic

cell death in both chemo-sensitive and chemo-resistant EOC

cells.

| Figure 3PRIMA-1MET induces

apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in EOC cell lines. (a) TOV21G

and A2780 cells were treated with 0, 10, 20 µM of

PRIMA-1MET for 16 h, and then stained with Annexin

V-FITC and PI. The Annexin V-positive and PI-negative cells were

defined as early apoptotic, and the Annexin V-positive and

PI-positive cells were defined as late apoptotic (dead cells). (b)

Viable, early apoptotic, and late apoptotic cells were quantified

from triplicate samples. Asterisk indicates statistical

significance (P<0.001). Error bars represent standard

deviations. (c) Representative images of Hoechst 33342 staining of

NOS3TR cells after 24 h of PRIMA-1MET treatment.

Apoptotic cells were defined by their condensed and fragmented

nuclei with fluorescence microscopy (scale bar, 200 µm). (d)

Apoptosis levels of NOS2 and NOS3 cells, and their chemo-resistant

cells after 0, 10, 25, 50 µM 20 h PRIMA-1MET

treatment. Bars represent the percentages of apoptotic nuclei

counted in each treatment group and are expressed as the mean ±

SD. |

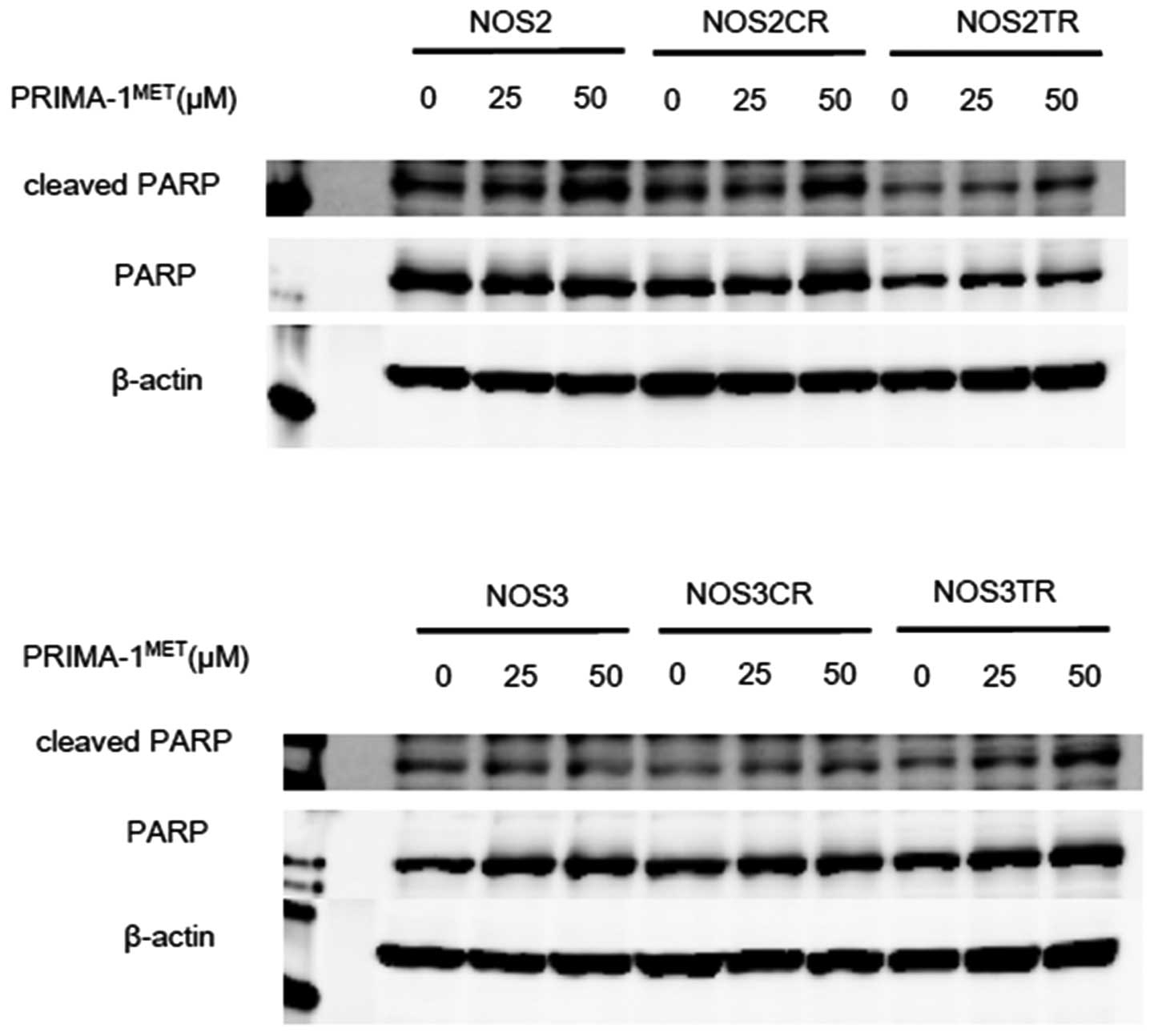

PRIMA-1MET activates PARP

cleavage

In order to confirm whether

PRIMA-1MET-induced cell death is apoptotic, we evaluated

the apoptosis-related protein levels after treatment with

PRIMA-1MET in EOC cells by western blot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis elucidated that PRIMA-1MET induced

dose-dependent PARP cleavage in the NOS2 and NOS3 cells and in

their chemo-resistant cells (Fig.

4). This result showed that PRIMA-1MET induces

apoptosis in EOC cells through PARP cleavage.

PRIMA-1MET increases

intracellular ROS in EOC cells

As it was reported that PRIMA-1MET

induces intracellular ROS accumulation, we investigated

intracellular ROS accumulation using

5–6-chloromethyl-2′7′-dichlorodihydroflorescein diacetate, acetyl

ester (CM-H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes Invitrogen,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) (20,30). PRIMA-1MET treatment for

24 h promoted intracellular ROS accumulation in the NOS2 and NOS3

cells, and their chemo-resistant cells (Fig. 5a). To quantify the proportion of

fluorescence-positive cells in the TOV21G cells after a 24-h

treatment with PRIMA-1MET, fluorescence activated cell

sorting (FACS) was performed. The proportion of

fluorescence-positive cells was increased in the cells treated with

PRIMA-1MET in a dose-dependent manner, and the increase

was significant (Fig. 5b and c).

These results demonstrate that PRIMA-1MET promotes

intracellular ROS accumulation in EOC cells.

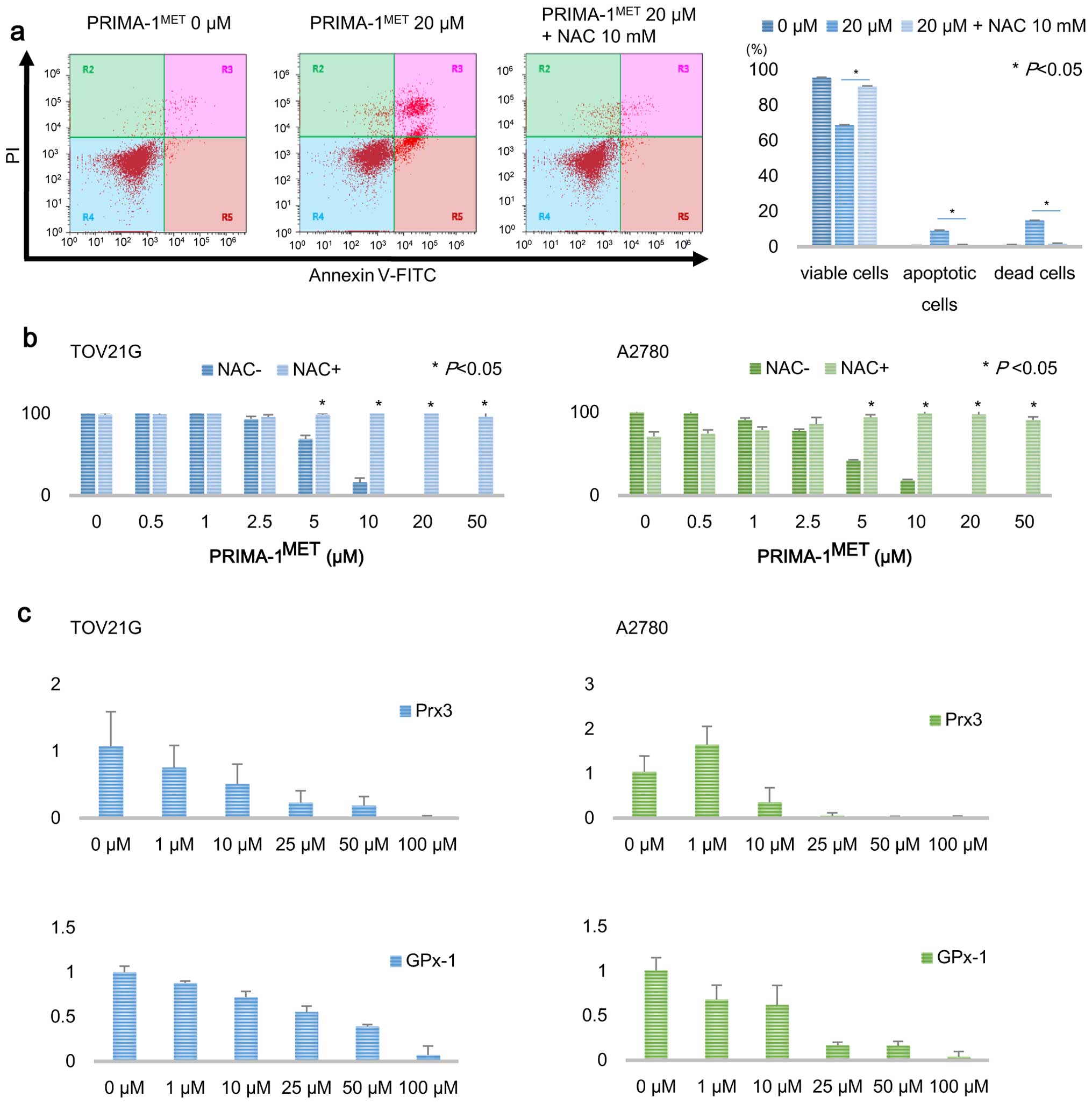

ROS scavenger rescues apoptosis induced

by PRIMA-1MET

To determine whether intracellular ROS accumulation

by treatment with PRIMA-1MET induces apoptosis, we used

a ROS scavenger N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). The compound NAC was added

to cultured cells with 20 µM PRIMA-1MET medium at

a final concentration of 10 mM. Sixteen hours after co-treatment

with PRIMA-1MET and NAC, apoptotic cells were assessed

by Annexin V-FITC and PI staining. The addition of NAC inhibited

apoptosis and the growth-suppressing effect induced by

PRIMA-1MET treatment (Fig.

6a and b). Furthermore, to examine the effect of

PRIMA-1MET on the expression of antioxidant enzymes

including Prx3 and GPx-1, which scavenge intracellular ROS to

sustain homeostasis, we treated TOV21G and A2780 cells with

PRIMA-1MET for 20 h and, thereafter, evaluated the mRNA

levels of antioxidant enzymes by real-time RT-PCR. The mRNA levels

of Prx3 and GPx-1 were significantly decreased after 20 h of

treatment with PRIMA-1MET in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 6c). Our results suggest that

the antitumor effects of PRIMA-1MET may be mediated by

intracellular ROS accumulation, and that the intracellular ROS

accumulation and the cytotoxic effect induced by

PRIMA-1MET may be due to downregulation of Prx3 and

GPx-1.

Discussion

Most EOC patients experience recurrent disease,

despite a high rate of complete clinical remission. Although

recurrent EOC patients frequently receive chemotherapy, they are

basically incurable due to the acquisition of chemo-resistance.

Resistance to cytotoxic agents is a major obstacle to complete

cure, and a number of attempts to overcome chemo-resistance have

been made in EOC (31,32). While much effort has been made to

restore chemo-sensitivity to resistant cells, no promising

molecules have been identified. Thus, there is a need to develop

novel therapeutics for EOC. Despite the fact that

PRIMA-1MET has been confirmed to exhibit

tumor-suppressing effects on various types of cancer cells, there

have been few reports on the effect of PRIMA-1MET on

chemo-resistant cells in EOC (33–35).

In our present study, we attempted to verify whether

PRIMA-1MET has antitumor effects on EOC cells.

PRIMA-1MET is a prodrug converted to MQ

with potential to bind to cysteine residues and change the

conformation of the core domain of mutant p53 (30). PRIMA-1/PRIMA-1MET has

been reported to synergize with cytotoxic agents to induce

apoptotic cell death (33,36,37).

Recently, Mohell et al reported that combined treatment with

APR-246 and platinum or other drugs could give rise to an improved

strategy for recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer (37). In this study, chemo-resistant cells

incubated with PRIMA-1MET exhibited apoptosis, which was

characterized by morphological features, such as chromosomal DNA

condensation and fragmentation. Furthermore, the effect of

PRIMA-1MET on cell viability of chemo-resistant cells

was similar to that of the parental cells with either wild-type p53

(NOS2) or mutant p53 (NOS3). These findings suggest that

PRIMA-1MET may have the possibility to be used for

patients with chemo-resistant EOC bearing not only mutant p53 but

also wild-type p53.

EOC cells easily spread to the peritoneal cavity and

form disseminated metastases with a large amount of ascites. During

this metastatic process, tumors may gradually acquire stem-like

properties and become chemo-resistant. To our knowledge, there has

been no report examining the efficacy of PRIMA-1MET in

cancer stem cells (or cancer stem-like cells). On the other hand, a

recent study suggested the possibility that PRIMA-1MET

may overcome the chemo-resistance of EOC cells (37). Indeed, PRIMA-1MET may be

able to target cancer stem cells with chemo-resistant properties

although additional studies are warranted.

In the present study, we investigated the efficacy

of PRIMA-1MET in the growth suppression and apoptosis

induction in ovarian cancer cell lines (n=9) in vitro. We

demonstrated that PRIMA-1MET suppressed cell viability

and induced massive apoptosis, regardless of the TP53 mutational

status. Furthermore, ovarian cancer cell lines carrying wild-type

p53 were slightly more sensitive than those carrying mutant p53

(not significant). To date, previous reports have shown that

PRIMA-1/PRIMA-1MET were more effective on pancreatic and

small cell lung cancer cells expressing mutant p53 than on those

expressing wild-type p53 or null (38,39).

Interestingly, despite the fact that there is evidence that

PRIMA-1MET restores the wild-type p53 function to mutant

p53, several recent studies have shown that PRIMA-1MET

displayed cytotoxic effects on Ewing sarcoma cells, acute myeloid

leukemia cells, and human myeloma cells irrespective of the TP53

mutational status (40–42). This controversy is because

PRIMA-1MET not only restores wild-type p53 function to

mutant p53, but also induces apoptosis in a p53-independent manner

through intracellular ROS accumulation and endoplasmic reticulum

(ER) stress (40,41). Indeed, in this study, we

demonstrated that incubation with PRIMA-1MET resulted in

an antitumor effect with intracellular ROS accumulation in ovarian

cancer cells, and co-treatment with PRIMA-1MET and an

ROS scavenger, NAC, blocked the cytotoxic effects, suggesting that

the effects of PRIMA-1MET are due to an intracellular

ROS increase in EOC cells. Our results were partly consistent with

previous reports, and support the antitumor effects of

PRIMA-1MET being universal irrespective of the TP53

mutational status in EOC cells. Unknown diverse mechanisms of

PRIMA-1MET may provide a convincing strategy for

overcoming chemo-resistance in not only EOC but also other

cancers.

ROS can generate oxidative stress in cells inducing

DNA damage, protein degradation, peroxidation of lipids, and

finally cell death at a high concentration. It is well known that

cancer cells are normally more tolerant to high levels of oxidative

stress than normal cells (43). One

of the underlying mechanisms of cancer cells to survive under high

oxidative condition is overexpression of antioxidant enzymes to

scavenge ROS (44). An inhibitor of

glutathione synthesis, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) was used in a

clinical situation (45). In the

present study, we demonstrated that PRIMA-1MET induced

intracellular accumulation and suppressed the expression of

antioxidant enzymes, Prx3 and GPx-1, in EOC cells. Prx3 is one of

the 2-Cys peroxiredoxin family (PRX 1–4), and operates as a

reductase to metabolize ROS (46).

Cunniff et al reported that knockdown of Prx3 increased

oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in malignant

mesothelioma cells, suggesting that Prx3 plays a critical role in

cell cycle progression and sustaining the mitochondrial structure

(47). Furthermore, a recent report

by Song et al showed that Prx3 was highly upregulated in

colon cancer stem cells, and that knockdown of Prx3 led to

decreased cellular viability (48).

In addition, several studies have already shown that GPx-1 protects

cancer cells upon exposure to severe oxidative stress (49,50).

According to our findings, PRIMA-1MET suppressed the

expression of both Prx3 and GPx-1, suggesting that it may induce an

intracellular ROS increase mediated by downregulation of Prx3 and

GPx-1.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have confirmed

intracellular ROS accumulation in benign tumor cells or normal

epithelial cells. In the present study, we did not evaluate whether

PRIMA-1MET induces intracellular ROS accumulation in

such non-malignant or normal cells. In the living body, the

majority of ROS generated by various stimulation can be degenerated

by a higher antioxidant capacity derived from intrinsic ROS

scavengers, resulting in weakened efficacy. We believe that the

actual effects may depend on the local balance between ROS and such

intrinsic scavengers. Certainly, PRIMA-1MET may induce

intracellular ROS accumulation in benign or normal cells as well as

tumor cells. We speculate that the carcinogenetic effect of

PRIMA-1MET in such cells may be minimal. However, we

cannot deny that administration of PRIMA-1MET may have

some risks. Therefore, further investigation concerning the effect

of PRIMA-1MET against benign or normal cells is

necessary when used clinically.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that

PRIMA-1MET exhibited antitumor effects on

chemo-resistant cells through intracellular ROS accumulation and

repressed antioxidant enzymes. To utilize PRIMA-1MET for

EOC patients including chemo-resistant cases, we need to

investigate further how PRIMA-1MET suppresses Prx3 and

GPx-1. PRIMA-1MET is a promising compound for further

development as a potential cytotoxic agent against EOC.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Kathleen Pishas for the

study and technical support.

References

|

1

|

Sankaranarayanan R and Ferlay J: Worldwide

burden of gynaecological cancer: The size of the problem. Best

Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 20:207–225. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Masoumi Moghaddam S, Amini A, Morris DL

and Pourgholami MH: Significance of vascular endothelial growth

factor in growth and peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer.

Cancer Metastasis Rev. 31:143–162. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Muñoz-Casares FC, Rufián S, Arjona-Sánchez

Á, Rubio MJ, Díaz R, Casado Á, Naranjo Á, Díaz-Iglesias CJ, Ortega

R, Muñoz-Villanueva MC, et al: Neoadjuvant intraperitoneal

chemotherapy with paclitaxel for the radical surgical treatment of

peritoneal carcinomatosis in ovarian cancer: A prospective pilot

study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 68:267–274. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chan JK, Tian C, Monk BJ, Herzog T, Kapp

DS, Bell J and Young RC; Gynecologic Oncology Group: Prognostic

factors for high-risk early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: A

Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 112:2202–2210. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chan JK, Teoh D, Hu JM, Shin JY, Osann K

and Kapp DS: Do clear cell ovarian carcinomas have poorer prognosis

compared to other epithelial cell types? A study of 1411 clear cell

ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 109:370–376. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J and

Thun MJ: Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 59:225–249.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bell D, Berchuck A, Birrer M, Chien J,

Cramer DW, Dao F, Dhir R, DiSaia P, Gabra H, Glenn P, et al Cancer

Genome Atlas Research Network: Integrated genomic analyses of

ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 474:609–615. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Havrilesky L, Darcy M, Hamdan H, Priore

RL, Leon J, Bell J and Berchuck A; Gynecologic Oncology Group

Study: Prognostic significance of p53 mutation and p53

overexpression in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic

Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 21:3814–3825. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, Rosen B,

Bradley L, Fan I, Tang J, Li S, Zhang S, Shaw PA, et al: Population

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: A

kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst.

98:1694–1706. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kang HJ, Chun SM, Kim KR, Sohn I and Sung

CO: Clinical relevance of gain-of-function mutations of p53 in

high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One. 8:e726092013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Giaccia AJ and Kastan MB: The complexity

of p53 modulation: Emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes

Dev. 12:2973–2983. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Di Agostino S, Strano S, Emiliozzi V,

Zerbini V, Mottolese M, Sacchi A, Blandino G and Piaggio G: Gain of

function of mutant p53: The mutant p53/NF-Y protein complex reveals

an aberrant transcriptional mechanism of cell cycle regulation.

Cancer Cell. 10:191–202. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Blandino G, Levine AJ and Oren M: Mutant

p53 gain of function: Differential effects of different p53 mutants

on resistance of cultured cells to chemotherapy. Oncogene.

18:477–485. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dong P, Karaayvaz M, Jia N, Kaneuchi M,

Hamada J, Watari H, Sudo S, Ju J and Sakuragi N: Mutant p53

gain-of-function induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through

modulation of the miR-130b-ZEB1 axis. Oncogene. 32:3286–3295. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Høgdall EV, Kjaer SK, Blaakaer J,

Christensen L, Glud E, Vuust J and Høgdall CK: P53 mutations in

tissue from Danish ovarian cancer patients: From the Danish

'MALOVA' ovarian cancer study. Gynecol Oncol. 100:76–82. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Concin N, Hofstetter G, Berger A,

Gehmacher A, Reimer D, Watrowski R, Tong D, Schuster E, Hefler L,

Heim K, et al: Clinical relevance of dominant-negative p73 isoforms

for responsiveness to chemotherapy and survival in ovarian cancer:

Evidence for a crucial p53-p73 cross-talk in vivo. Clin Cancer Res.

11:8372–8383. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Y, Helland A, Holm R, Skomedal H,

Abeler VM, Danielsen HE, Tropé CG, Børresen-Dale AL and Kristensen

GB: TP53 mutations in early-stage ovarian carcinoma, relation to

long-term survival. Br J Cancer. 90:678–685. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ueno Y, Enomoto T, Otsuki Y, Sugita N,

Nakashima R, Yoshino K, Kuragaki C, Ueda Y, Aki T, Ikegami H, et

al: Prognostic significance of p53 mutation in suboptimally

resected advanced ovarian carcinoma treated with the combination

chemotherapy of paclitaxel and carboplatin. Cancer Lett.

241:289–300. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bartel F, Jung J, Böhnke A, Gradhand E,

Zeng K, Thomssen C and Hauptmann S: Both germ line and somatic

genetics of the p53 pathway affect ovarian cancer incidence and

survival. Clin Cancer Res. 14:89–96. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Peng X, Zhang MQ, Conserva F, Hosny G,

Selivanova G, Bykov VJ, Arnér ES and Wiman KG:

APR-246/PRIMA-1MET inhibits thioredoxin reductase 1 and

converts the enzyme to a dedicated NADPH oxidase. Cell Death Dis.

4:e8812013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Issaeva N, Bozko P, Enge M, Protopopova M,

Verhoef LG, Masucci M, Pramanik A and Selivanova G: Small molecule

RITA binds to p53, blocks p53-HDM-2 interaction and activates p53

function in tumors. Nat Med. 10:1321–1328. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Russo D, Ottaggio L, Penna I, Foggetti G,

Fronza G, Inga A and Menichini P: PRIMA-1 cytotoxicity correlates

with nucleolar localization and degradation of mutant p53 in breast

cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 402:345–350. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Roh JL, Kang SK, Minn I, Califano JA,

Sidransky D and Koch WM: p53-Reactivating small molecules induce

apoptosis and enhance chemotherapeutic cytotoxicity in head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 47:8–15. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Lehmann S, Bykov VJ, Ali D, Andrén O,

Cherif H, Tidefelt U, Uggla B, Yachnin J, Juliusson G, Moshfegh A,

et al: Targeting p53 in vivo: A first-in-human study with

p53-targeting compound APR-246 in refractory hematologic

malignancies and prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 30:3633–3639. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Misawa T, Kikkawa F, Maeda O, Obata NH,

Higashide K, Suganuma N and Tomoda Y: Establishment and

characterization of acquired resistance to platinum anticancer

drugs in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 86:88–94.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Terauchi M,

Yamashita M, Ino K, Nawa A and Kikkawa F: Chemoresistance to

paclitaxel induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and enhances

metastatic potential for epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells. Int J

Oncol. 31:277–283. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kapitanović S, Cacev T, Antica M, Kralj M,

Cavrić G, Pavelić K and Spaventi R: Effect of indomethacin on

E-cadherin and beta-catenin expression in HT-29 colon cancer cells.

Exp Mol Pathol. 80:91–96. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sugiyama K, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Yuan H,

Kikkawa F and Senga T: Expression of the miR200 family of microRNAs

in mesothelial cells suppresses the dissemination of ovarian cancer

cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 13:2081–2091. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Nakahara T, Iwase A, Nakamura T, Kondo M,

Bayasula, Kobayashi H, Takikawa S, Manabe S, Goto M, Kotani T, et

al: Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibits

H2O2-induced granulosa cell apoptosis via the

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Fertil Steril. 98:1001.e1–1008.e1.

2012.

|

|

30

|

Lambert JM, Gorzov P, Veprintsev DB,

Söderqvist M, Segerbäck D, Bergman J, Fersht AR, Hainaut P, Wiman

KG and Bykov VJ: PRIMA-1 reactivates mutant p53 by covalent binding

to the core domain. Cancer Cell. 15:376–388. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Utsumi F, Kajiyama H, Nakamura K, Tanaka

H, Mizuno M, Ishikawa K, Kondo H, Kano H, Hori M and Kikkawa F:

Effect of indirect nonequilibrium atmospheric pressure plasma on

anti-proliferative activity against chronic chemo-resistant ovarian

cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 8:e815762013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Duan Z, Choy E and Hornicek FJ: NSC23925,

identified in a high-throughput cell-based screen, reverses

multidrug resistance. PLoS One. 4:e74152009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bykov VJ, Zache N, Stridh H, Westman J,

Bergman J, Selivanova G and Wiman KG: PRIMA-1(MET) synergizes with

cisplatin to induce tumor cell apoptosis. Oncogene. 24:3484–3491.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Supiot S, Zhao H, Wiman K, Hill RP and

Bristow RG: PRIMA-1(met) radiosensitizes prostate cancer cells

independent of their MTp53-status. Radiother Oncol. 86:407–411.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ali D, Jönsson-Videsäter K, Deneberg S,

Bengtzén S, Nahi H, Paul C and Lehmann S: APR-246 exhibits

anti-leukemic activity and synergism with conventional

chemotherapeutic drugs in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Eur J

Haematol. 86:206–215. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Nahi H, Lehmann S, Mollgard L, Bengtzen S,

Selivanova G, Wiman KG, Paul C and Merup M: Effects of PRIMA-1 on

chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells with and without hemizygous p53

deletion. Br J Haematol. 127:285–291. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mohell N, Alfredsson J, Fransson Å,

Uustalu M, Byström S, Gullbo J, Hallberg A, Bykov VJ, Björklund U

and Wiman KG: APR-246 overcomes resistance to cisplatin and

doxorubicin in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 6:e17942015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zandi R, Selivanova G, Christensen CL,

Gerds TA, Willumsen BM and Poulsen HS:

PRIMA-1Met/APR-246 induces apoptosis and tumor growth

delay in small cell lung cancer expressing mutant p53. Clin Cancer

Res. 17:2830–2841. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Izetti P, Hautefeuille A, Abujamra AL, de

Farias CB, Giacomazzi J, Alemar B, Lenz G, Roesler R, Schwartsmann

G, Osvaldt AB, et al: PRIMA-1, a mutant p53 reactivator, induces

apoptosis and enhances chemotherapeutic cytotoxicity in pancreatic

cancer cell lines. Invest New Drugs. 32:783–794. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tessoulin B, Descamps G, Moreau P, Maïga

S, Lodé L, Godon C, Marionneau-Lambot S, Oullier T, Le Gouill S,

Amiot M, et al: PRIMA-1Met induces myeloma cell death

independent of p53 by impairing the GSH/ROS balance. Blood.

124:1626–1636. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Russo D, Ottaggio L, Foggetti G, Masini M,

Masiello P, Fronza G and Menichini P: PRIMA-1 induces autophagy in

cancer cells carrying mutant or wild type p53. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1833:1904–1913. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Aryee DN, Niedan S, Ban J, Schwentner R,

Muehlbacher K, Kauer M, Kofler R and Kovar H: Variability in

functional p53 reactivation by PRIMA-1(Met)/APR-246 in Ewing

sarcoma. Br J Cancer. 109:2696–2704. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tong L, Chuang CC, Wu S and Zuo L:

Reactive oxygen species in redox cancer therapy. Cancer Lett.

367:18–25. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Landry WD and Cotter TG: ROS signalling,

NADPH oxidases and cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 42:934–938. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bailey HH, Mulcahy RT, Tutsch KD,

Arzoomanian RZ, Alberti D, Tombes MB, Wilding G, Pomplun M and

Spriggs DR: Phase I clinical trial of intravenous L-buthionine

sulfoximine and melphalan: An attempt at modulation of glutathione.

J Clin Oncol. 12:194–205. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cox AG, Peskin AV, Paton LN, Winterbourn

CC and Hampton MB: Redox potential and peroxide reactivity of human

peroxiredoxin 3. Biochemistry. 48:6495–6501. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cunniff B, Wozniak AN, Sweeney P, DeCosta

K and Heintz NH: Peroxiredoxin 3 levels regulate a mitochondrial

redox setpoint in malignant mesothelioma cells. Redox Biol.

3:79–87. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Song IS, Jeong YJ, Jeong SH, Heo HJ, Kim

HK, Bae KB, Park YH, Kim SU, Kim JM, Kim N, et al: FOXM1-induced

PRX3 regulates stemness and survival of colon cancer cells via

maintenance of mitochondrial function. Gastroenterology.

149:1006.e9–1016.e9. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Huang C, Ding G, Gu C, Zhou J, Kuang M, Ji

Y, He Y, Kondo T and Fan J: Decreased selenium-binding protein 1

enhances glutathione peroxidase 1 activity and downregulates HIF-1α

to promote hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness. Clin Cancer Res.

18:3042–3053. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gan X, Chen B, Shen Z, Liu Y, Li H, Xie X,

Xu X, Li H, Huang Z and Chen J: High GPX1 expression promotes

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invasion, migration,

proliferation and cisplatin-resistance but can be reduced by

vitamin D. Int J Clin Exp Med. 7:2530–2540. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|