Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma is one of the most common

malignancies and has been ranked as the sixth leading cause of

cancer-related death worldwide (1–4).

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), accounting for

approximately 90% of all esophageal carcinoma cases, is more

predominant in Asian countries (5).

In the past decades, although tremendous strides have been made in

therapeutic strategies including surgical resection, radiotherapy

and chemotherapy, tumor invasion and metastasis still invariably

heralds a poor prognosis and a low 5-year survival rate in ESCC

patients (6–8). Therefore, a better understanding of

the molecular mechanisms involved in tumor invasion and metastasis

and discovery of a more effective target for anticancer therapy may

help to prolong the survival and improve the life quality of

patients with ESCC.

The a disintegrin and metalloproteases (ADAMs), a

family of zinc-dependent transmembrane proteins, contain a

metalloprotease and a disintegrin-like domain (9–11) and

are closely associated with the degradation of the basement

membrane, cell migration, cell fusion and signal transduction

(12,13), thus playing important roles in the

tumorigenesis, proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, invasion

and metastasis of cancers (14–16).

To date, approximately 40 ADAM members have been identified in this

family, however only 21 are thought to function in humans (10). ADAM10 is an important

proteolytically active member of this family (17). Emerging evidence suggests that

ADAM10 is overexpressed in a variety of cancers and is associated

with the tumor progression of breast cancer (18), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

(19), nasopharyngeal carcinoma

(20), oral squamous cell carcinoma

(21,22) tongue squamous cell carcinoma

(23), hepatocellular carcinoma

(24,25), gastric cancer (26), colon cancer (27), pancreatic carcinoma (28), bladder cancer (29) and renal cell carcinoma (30). Proteolytically active ADAM10 acts as

an ectodomain-sheddase, which can release the extracellular domain

of membrane-bound proteins, such as adhesion molecules, growth

factors, cytokines, chemokines and receptors; through these actions

they are able to disrupt the tumor microenvironment and modulate

key processes involved in tumor cell proliferation, migration and

angiogenesis (31,32). E-cadherin is a transmembrane

molecule that functions as an adhesion molecule, and is reported as

an ADAM10 substrate (33,34). ADAM10 activity could lead to

elevated shedding of E-cadherin and loss of cell-cell contact

(35), further enhancing migratory

and metastatic behavior (36).

However, to date there has been no related study concerning the

role of ADAM10 in the tumorigenesis, invasion and metastasis of

ESCC. Moreover, whether the potential mechanism by which ADAM10

promotes tumor progression is associated with E-cadherin shedding

is still unclear.

Herein, in the present study, we first detected

expression of ADAM10 protein in ESCC tissues in vivo and

compared it to E-cadherin expression and clinicopathological

parameters associated with tumor invasion and metastasis, including

tumor differentiation, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis and

TNM stage. In addition, ADAM10 expression in ESCC cell lines was

examined in vitro and compared to cell invasion and

migration ability. Furthermore, we inhibited the expression of

ADAM10 in ESCC cell lines by using ADAM10 siRNA and analyzed the

effect of the downregulation of ADAM10 on cell proliferation,

invasion and migration and the expression levels of E-cadherin

in vitro.

Materials and methods

Statement of ethics

This study was performed according to ethical

protocol approved by the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou

University, Henan, China. All of the clinical tissue samples used

in this study were collected after obtaining written informed

consents. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Tissue specimens

A total of 122 ESCC tissue specimens and 60 adjacent

normal esophageal mucosa were obatined from patients (73 male and

49 female) who underwent surgical resection at The First Affiliated

Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Henan, China. None of the

patients had previously received neoadjuvant radiotherapy,

chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Tissue sections were cut at a

thickness of 4 µm for in situ hybridization (ISH) and

immunohistochemistry (IHC). Clinical features of all the samples

are listed in Table I. The

diagnosis of ESCC was reconfirmed by two board-certified

pathologists.

| Table IProtein and mRNA expression of ADAM10

and E-cadherin in ESCC tissues and corresponding normal esophageal

mucosa. |

Table I

Protein and mRNA expression of ADAM10

and E-cadherin in ESCC tissues and corresponding normal esophageal

mucosa.

| n | ADAM10

| χ2 | P-value | E-cadherin

| χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| − | + | − | + |

|---|

| Protein |

| Normal mucosa | 60 | 49 | 11 | 37.164 | 0.000 | 7 | 53 | 51.120 | 0.000 |

| ESCC | 122 | 41 | 81 | | | 83 | 39 | | |

| mRNA |

| Normal mucosa | 60 | 51 | 9 | 31.550 | 0.000 | 0 | 60 | 59.946 | 0.000 |

| ESCC | 122 | 50 | 72 | | | 73 | 49 | | |

In situ hybridization (ISH) and

evaluation of ISH staining

Paraffin-embedded slides were deparaffinized,

rehydrated, and immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide. Then the slides

were digested in pepsin solution, and incubated with

pre-hybridization solution and hybridization solution sequentially.

After visualization of ISH using BCIP/NBT, the slides were

counter-stained with Nuclear Fast Red. The digoxin-labeled probe

sequences used in this study were as follows: ADAM10 forward

primer, 5-GAGGAGTGTACGTGTGCCAGTT-3 and reverse primer,

5-GACCACTGAAGTGCCTACTCCA-3; E-cadherin forward primer,

5-AAAGGCCCATTTCCTAAAAACCT-3 and reverse primer,

5-TGCGTTCTCTATCCAGAGGCT-3. ADAM10- and E-cadherin-positive staining

was viewed as kyano-purple granule-like material that was located

in the cytoplasm. The staining index was calculated by adding the

scores for the percentage of positively stained cells (1, 0–10%; 2,

>10–30%; 3, >30–70%; and 4, >70%) and the staining

intensity (1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong). A score of 0–2 was

designated as a negative score (−), and ≥3 as a positive score (+).

All of the staining analyses were independently performed by two

pathologists.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and evaluation

of IHC staining

Paraffin-embedded slides were deparaffinized,

rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval by using a microwave

oven. Then the slides were incubated with primary antibodies

anti-ADAM10 (1:200, Abcam, USA) or anti-E-cadherin (1:100, Santa

Cruz, CA, USA) respectively, and subsequently incubated with

biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. After

visualization of the immunoreactivity using DAB, the slides were

counterstained with hematoxylin. ADAM10-and E-cadherin-positive

staining was viewed as brown-yellow granule-like material that was

located in the membrane and/or cytoplasm. The staining index was

calculated by adding the scores for the percentage of positively

stained cells (1, 0–10%; 2, >10–50%; and 3, >50%) and the

staining intensity (1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong). A score

of 0–2 was designated as a negative score (−), and ≥3 as a positive

score (+). All of the staining analyses were independently

performed by two pathologists.

Cell lines and culture

Human ESCC cell line EC-1 was supplied by Professor

Shihua Cao (Hong Kong University). Eca109 and TE-1 cells were

maintained in the Key Laboratory of Tumor Pathology of Zhengzhou

University. Normal esophageal epithelial cells (NEECs) of primary

culture were obtained from fresh biopsies of esophageal mucosal

tissues, during our previous experiment. All cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS),

100 µg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin, in a

humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Additionally, 1.0 ng/ml of epidermal growth factor (EGF) was added

to the medium for the NEECs.

ADAM10 siRNA transfection of EC-1

cells

The sequences of ADAM10 siRNA and the control

nonspecific siRNA were as follows: sense strand,

AAAGGAUUCCCAUACUGAC and antisense strand, GUCAGUAUGGGAAUCCUUU for

ADAM10; sense strand, AUCUUGAUCUUCAUUGUGC and antisense strand,

GCACAAUGAAGAUCAAGAU for the nonspecific control. EC-1 cells grown

until 80–90% confluency were transfected with 100 nM ADAM10 siRNA

using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. EC-1 cells untreated or

transfected with the nonspecific siRNA were used as control. The

cells were cultured for an additional 48 h in a humidified

incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C before being

harvested for further assays.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription

(RT) and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells

using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Two micrograms of total RNA was used for

cDNA synthesis using the HiScript II RT kit (Vazyme, Nanjing,

China). To evaluate ADAM10 and E-cadherin mRNA expression,

real-time PCR was performed using a PRISM 7300 Sequence Detection

system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). β-actin was

selected as an internal control. The primer sequences were as

follows: forward, 5-CACGAGAAGCTGTGATTGCC-3 and reverse,

5-ATTCCGGAGAAGTCTGTGGTC-3 for ADAM10; forward,

5-TGATTCTGCTGCTCTTGCTG-3 and reverse, 5-CAAAGTCCTGGTCCTCTTCTCC-3

for E-cadherin; forward, 5-TTCGAGCAAGAGTGGCCA-3 and reverse,

5-AGGTAGTTTCGTGGATGCCA-3 for β-actin. ADAM10 and E-cadherin

expression levels were normalized to β-actin and analyzed by using

the 2−0394ΔCt method (37). All experiments were carried out in

triplicate.

Protein extraction and western blot

analysis

Protein was extracted from the cultured cells using

RIPA lysis buffer (Well, Shanghai, China) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The protein concentration was determined

using the BCA kit (Bioss, Beijing, China). For western blot

analysis, 50 µg of protein extract from each cell line was

separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. After

blocking with 5% non-fat milk in PBST for 1 h at room temperature,

the membrane was incubated with the primary antibody (ADAM10,

1:500, 84 kDa; E-cadherin, 1:200, 120 kDa) at 4°C overnight.

β-actin (1:5,000, 43 kDa) was selected as a loading control.

Protein bands were detected with the ECL system (Well, Shanghai,

China) and exposed to X-ray film. Quantification was performed by

using ImageJ analysis tool. All experiments were carried out in

triplicate.

Matrigel invasion assay

Tumor cell invasion ability was analyzed using an

invasion chamber (Corning®, Corning, NY, USA). Briefly,

a polycarbonate membrane with 8-µm pores was coated with

Matrigel and dried at room temperature for 1 h in a 24-well plate.

Cells in serum-free medium were seeded into the upper chamber of

the wells and RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS was added into the lower

chamber as a chemoattractant. Following incubation at 37°C in 5%

CO2 for 24 h, cells on the upper surface of the membrane

were scrubbed away by a cotton swab. Cells invading through the

membrane and adhering to the lower surface of the membrane were

fixed with 95% alcohol, stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 1 h,

and quantitated by measuring the number of stained cells in five

individual fields at a ×400 magnification under a light

micro-scope. All experiments were carries out in triplicate.

Scratch wound healing assay

Cell migration ability was measured by a scratch

wounding healing assay. Cells were seeded into 12-well plates and

incubated in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS medium. Following incubation

for 24 h, a scratch would was made across the center of the

monolayer cells by using a sterile 200-µl pipette tip.

Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS to remove the detached

cells and incubated with serum-free medium for an additional 48 h.

Images of the cells that had migrated into the cell-free scratch

wound area were acquired at a ×200 magnification under a reversed

light microscope. Cell migration ability was quantitated by

measuring the width of the wounds in at least five representative

fields and is expressed as 1 minus the average percent of the wound

closure compared with the initial wound area measured. All

experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation ability was measured by Cell

Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. Briefly, the cells were seeded into

96-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well and

incubated for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively. At different time

intervals, 10 µl of CCK-8 solution (Sangon, Shanghai, China)

was added to the corresponding wells and incubated for an

additional 4 h. The staining intensity in the medium was measured

by determining the absorbance (OD values) at 450 nm to obtain cell

growth curves. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0

statistical package. The difference in counted data was examined by

the χ2 test. Meanwhile, quantitative data are expressed

as mean ± SD, and differences in quantitative data were examined by

the t-test. A P-value <0.05 was defined as indicating a

statistically significant result.

Results

ADAM10 expression is elevated and

E-cadherin expression is reduced in ESCC tissues

Emerging evidence suggests that ADAM10 is

overexpressed in a variety of cancers and participates in tumor

progression (18–30). Thus, IHC was initially performed to

determine the protein expression level of ADAM10 in ESCC tissues

and corresponding normal esophageal mucosal tissues.

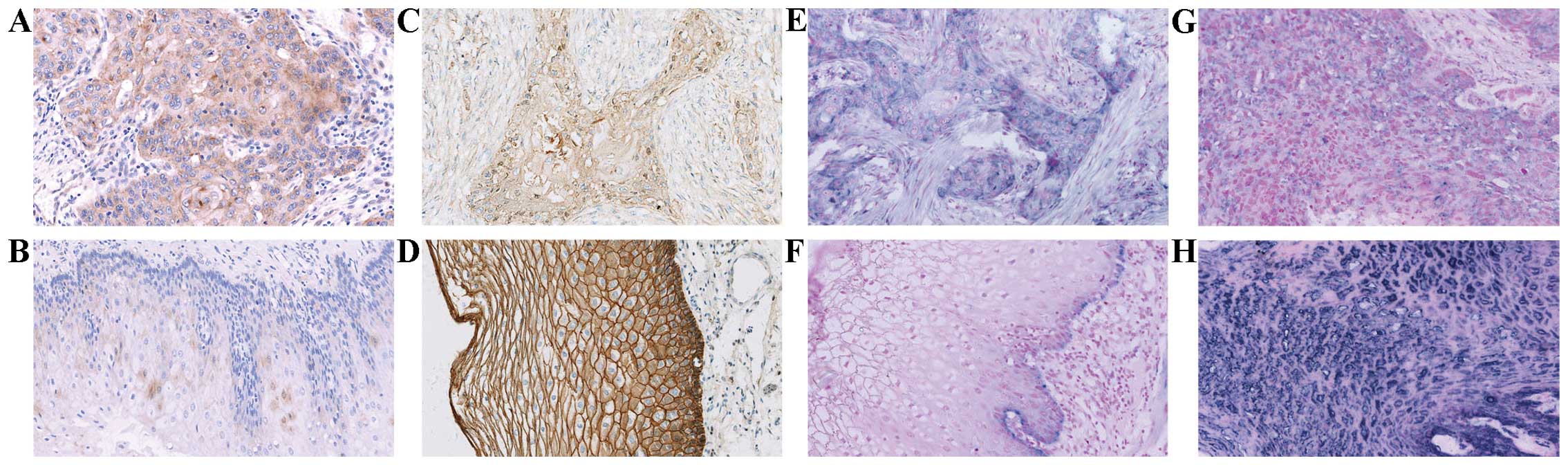

ADAM10-positive signals showed brown-yellow granules in the

membrane and/or cytoplasm (Fig. 1A and

B). Cytoplasmic expression of ADAM10 protein was strong in the

ESCC tissues (Fig. 1A), but weak in

the normal esophageal mucosa (Fig.

1B). The positive rate of ADAM10 was 66.4% (81/122) in the ESCC

tissues, significantly higher than that in the corresponding normal

esophageal mucosa [18.3% (11/60); P=0.000) (Table I).

Since ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and

regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion (33), we next detected the expression level

of E-cadherin in the ESCC tissues and the corresponding normal

esophageal mucosa tissues. E-cadherin-positive signals were

presented as brown-yellow granules in the membrane and/or cytoplasm

(Fig. 1C and D). Membranal and/or

cytoplasmic expression of E-cadherin protein was negative or

moderate (Fig. 1C) in the ESCC

tissues, but strong in the normal esophageal mucosa (Fig. 1D). The positive rate of E-cadherin

was 32.0% (39/122) in the ESCC tissues, significantly lower than

that in the corresponding normal esophageal mucosa [88.3% (53/60);

P=0.000) (Table I).

Furthermore, in situ hybridization (ISH) was

used to detect the mRNA expression levels of ADAM10 and E-cadherin

in the ESCC tissues and corresponding normal esophageal mucosa

tissues. ADAM10-and E-cadherin-positive signals both showed

kyano-purple granule in cytoplasm (Fig.

1E–H). Expression of ADAM10 mRNA was strong in the ESCC tissues

(Fig. 1E), but was present only in

the basement of the normal esophageal mucosa (Fig. 1F). Expression of E-cadherin mRNA was

negative or weak (Fig. 1G) in the

ESCC tissues, but strong in the normal esophageal mucosa (Fig. 1H). The positive rates of ADAM10 and

E-cadherin were 59.0 (72/122) and 40.2% (49/122) in the ESCC

tissues, and 15.0 (9/60) and 100.0% (60/60) in the corresponding

normal mucosa, respectively. Moreover, the expression of ADAM10

mRNA in the ESCC tissues was significantly higher than that in the

corresponding normal esophageal mucosa (P=0.000), whereas contrary

results were observed in the expression of E-cadherin mRNA

(P=0.000) (Table I).

Taken together, the above data demonstrated that

overexpression of ADAM10 contributes to carcinogenesis of ESCC and

this action may be attributable to ADAM10-mediated E-cadherin

shedding.

Elevated ADAM10 and reduced E-cadherin

protein levels are associated with tumor progression in ESCC

tissues

To investigate the clinical significance of ADAM10

and E-cadherin in ESCC tissues, we analyzed the correlation of

their protein expression levels with clinicopathological features

including histological grade, depth of invasion, lymph node

metastasis and TNM stage. As shown in Table II, ADAM10 expression was positively

correlated with depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis and TNM

stage (P<0.05, respectively), but not correlated with

histological grade (P>0.05). On the contrary, E-cadherin

expression was negatively correlated with histological grade, depth

of invasion, lymph node metastasis and TNM stage (P<0.05,

respectively). These data demonstrated that in the ESCC tissues

elevated ADAM10 and reduced E-cadherin levels play a pivotal role

in tumor progression, such as invasion and metastasis.

| Table IICorrelation of ADAM10 and E-cadherin

proteins with clinicopathological parameters in the ESCC

tissues. |

Table II

Correlation of ADAM10 and E-cadherin

proteins with clinicopathological parameters in the ESCC

tissues.

| n | ADAM10

| χ2 | P-value | E-cadherin

| χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| − | + | − | + |

|---|

| Gender |

| Male | 73 | 44 | 29 | 0.015 | 0.904 | 48 | 25 | 0.434 | 0.510 |

| Female | 49 | 29 | 20 | | | 35 | 14 | | |

| Age (years) |

| ≥60 | 77 | 46 | 31 | 0.001 | 0.977 | 52 | 25 | 0.024 | 0.877 |

| <60 | 45 | 27 | 18 | | | 31 | 14 | | |

| Histological

grade |

| I | 33 | 16 | 17 | 4.510 | 0.105 | 16 | 17 | 7.981 | 0.018 |

| II | 51 | 14 | 37 | | | 38 | 13 | | |

| III | 38 | 11 | 27 | | | 29 | 9 | | |

| Depth of

invasion |

| Superficial

muscularis | 19 | 11 | 8 | 6.014 | 0.049 | 8 | 11 | 7.360 | 0.025 |

| Deep

muscularis | 46 | 14 | 32 | | | 32 | 14 | | |

| Fibrous

membrane | 57 | 16 | 41 | | | 43 | 14 | | |

| Lymph node

metastasis |

| No | 74 | 34 | 40 | 12.835 | 0.000 | 44 | 30 | 6.357 | 0.012 |

| Yes | 48 | 7 | 41 | | | 39 | 9 | | |

| TNM stage |

| I | 17 | 11 | 6 | 8.920 | 0.012 | 7 | 10 | 6.790 | 0.034 |

| II | 44 | 14 | 30 | | | 33 | 11 | | |

| III | 61 | 16 | 45 | | | 43 | 18 | | |

Negative correlation of ADAM10 and

E-cadherin protein levels in ESCC tissues

To explore the role of active ADAM10 involving

E-cadherin in ESCC progression, we further studied the correlation

of ADAM10 protein expression with E-cadherin in the ESCC tissues.

As shown in Table III, ADAM10

protein expression was significantly negatively correlated with

E-cadherin (r=−0.554, P=0.000), implying ADAM10 may control the

invasion and metastasis of ESCC through E-cadherin shedding.

| Table IIICorrelation of ADAM10 with E-cadherin

protein in the ESCC tissues. |

Table III

Correlation of ADAM10 with E-cadherin

protein in the ESCC tissues.

| E-cadherin | ADAM10

| r | P-value |

|---|

| + | − |

|---|

| + | 11 | 28 | −0.554 | 0.000 |

| − | 70 | 13 | | |

ADAM10 is overexpressed in ESCC cell

lines and high expression of ADAM10 is correlated with increased

cell invasion and migration in vitro

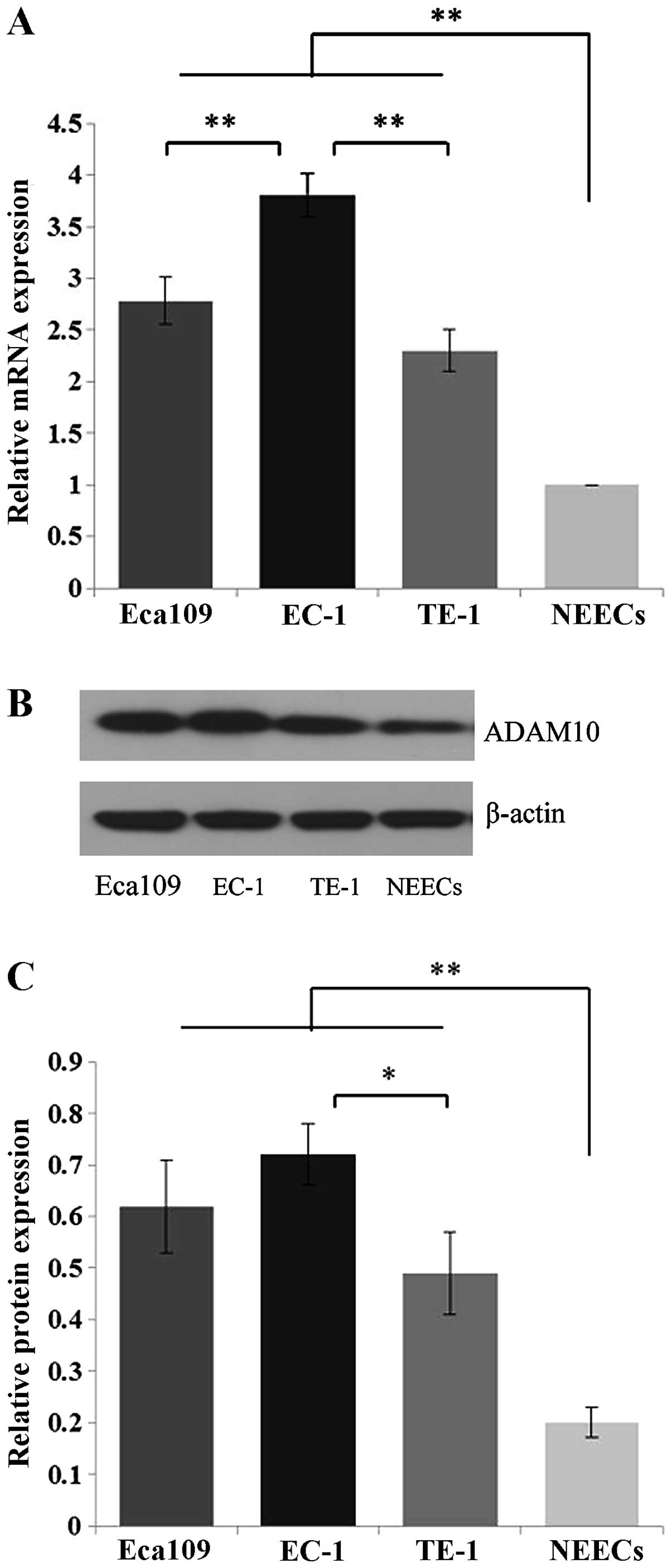

To further investigate the potential biological

roles of ADAM10 in ESCC, cell experiments were carried out. We

first used quantitative real-time PCR and western blot analysis to

detect the expression levels of ADAM mRNA and protein in ESCC

Eca109, EC-1 and TE-1 cells. Compared to the NEECs, Eca109, EC-1

and TE-1 cells showed significant overexpression of ADAM10 at both

the mRNA and protein levels (P<0.01) (Fig. 2). Moreover, this increased

expression was more apparent in the EC-1 cells than that in the

Eca109 and TE-1 cells at the mRNA level (P<0.01), and than that

in the TE-1 cells at the protein level (P<0.05) (Fig. 2).

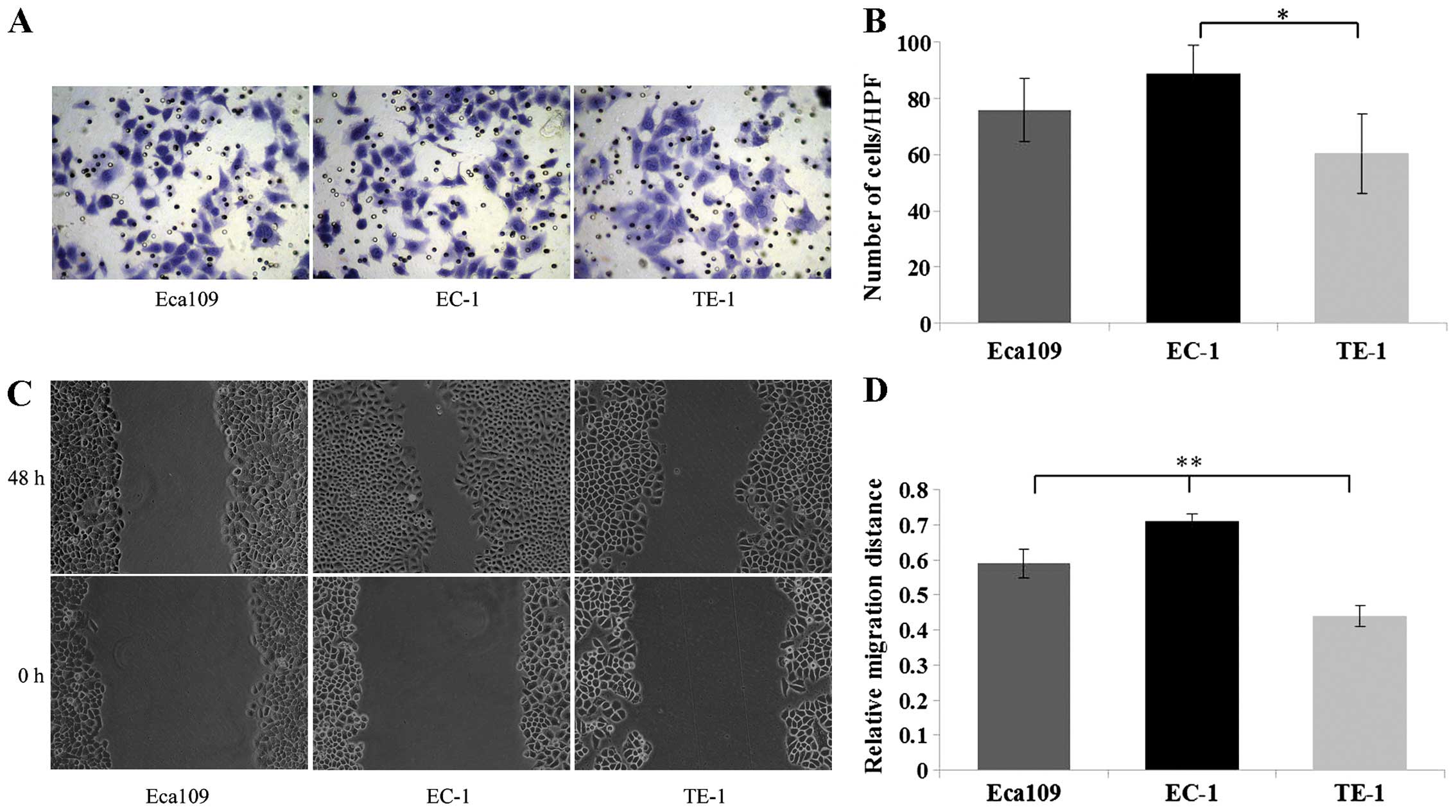

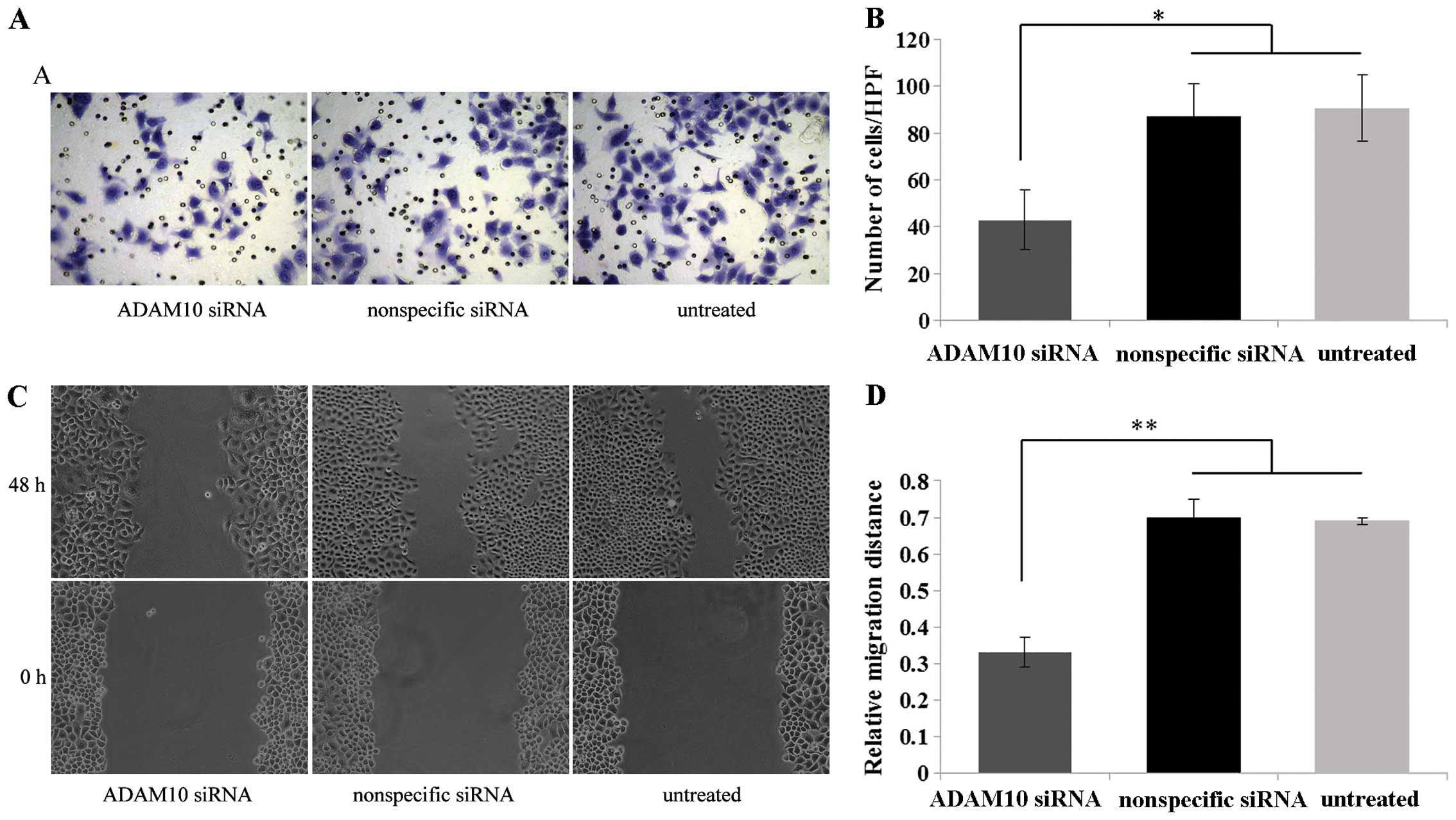

Based on the above clinical correlation analysis in

the ESCC tissues, it is reasonable to hypothesize that ADAM10 plays

an important role in promoting the invasion and migration of ESCC

cells. Therefore, we next detected the invasion and migration

ability of the ESCC cells using Matrigel invasion and scratch wound

healing assays, respectively. The invasion assay demonstrated that

the EC-1 cells exhibited a significant increase in the number of

cells that traversed the membrane toward a chemoattractant as

compared with the TE-1 cells (P<0.05) (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, the scratch

assay demonstrated that EC-1 cells showed a significant increase in

the tumor cell migration distance as compared with the Eca109 and

TE-1 cells (P<0.01) (Fig. 3C and

D).

| Figure 3Matrigel invasion and scratch wound

healing assays were used to detect the invasion and migration

ability of ESCC cells. (A) For the Matrigel invasion assay, 3 ESCC

cell lines (Eca109, EC-1, TE-1) in serum-free medium were seeded

into the upper chamber and incubated for 24 h, respectively;

subsequently cells invading through the Matrigel were fixed,

stained and photographed under a light microscope at a ×400

magnification. (B) EC-1 cells exhibited a significant increase in

the number of traversed cells as compared with the TE-1 cells. (C)

For the scratch wound healing assay, 3 ESCC cell lines (Eca109,

EC-1, TE-1) were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated in medium

containing 10% FBS for 24 h, respectively. Subsequently the wounds

were made, and the cells were incubated in serum-free medium for an

additional 48 h and photographed under a reversed light microscope

at a ×200 magnification. (D) The bar graph shows that the EC-1 cell

migration was more rapid than the rate noted in the TE-1 cells.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. |

In line with the aberrant ADAM10 in these 3 types of

ESCC cell lines, EC-1 cells with high ADAM10 expression

demonstrated higher invasion and migration ability, whereas TE-1

cells with low ADAM10 expression demonstrated poor invasion and

migration ability, suggesting that high ADAM10 expression is

consistent with increased cell invasion and migration ability.

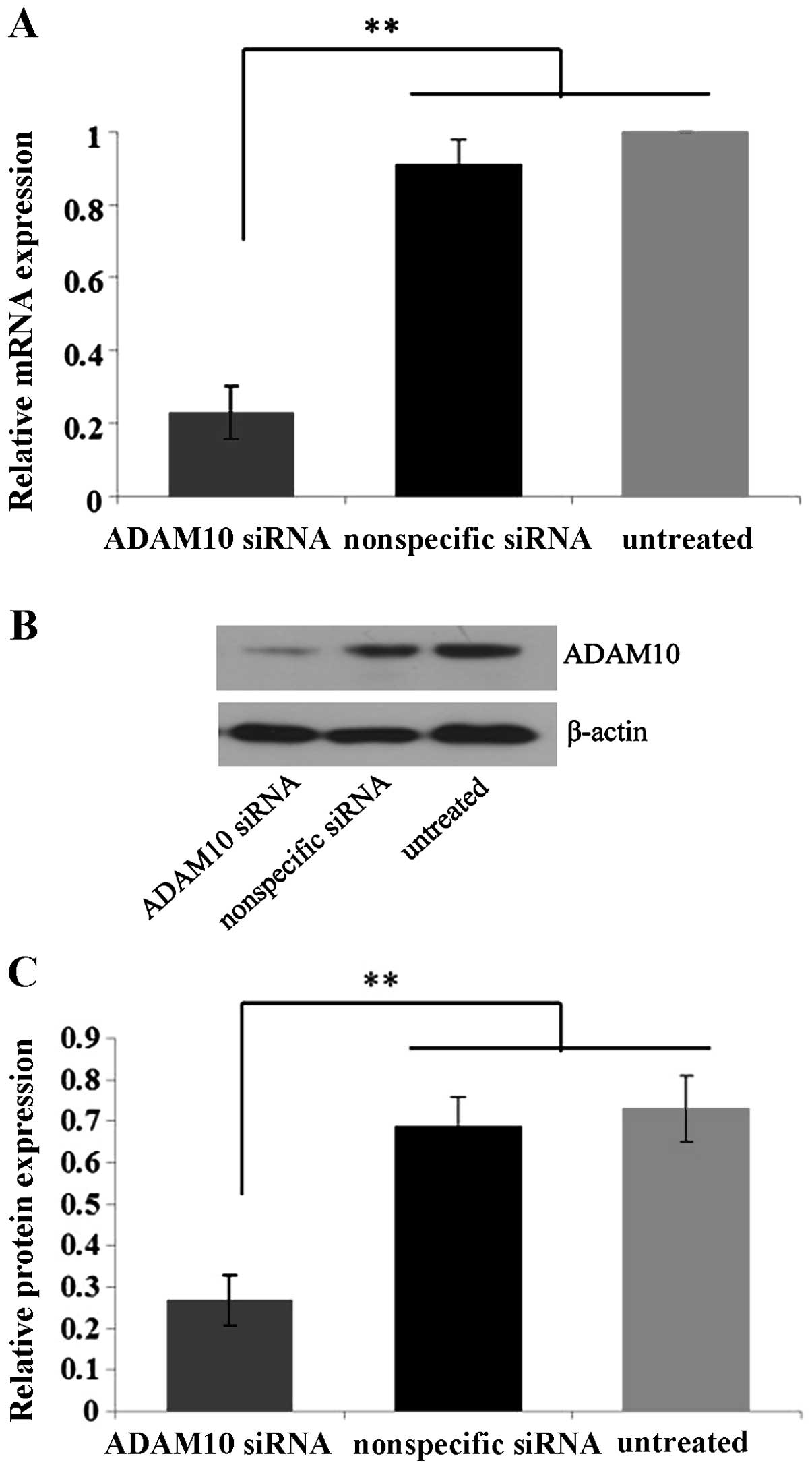

Specific blockage of ADAM10 by ADAM10

siRNA in EC-1 cells in vitro

In order to detect the knockdown efficiency of

ADAM10 by ADAM10 siRNA, EC-1 cells were selected due to their

elevated ADAM10 expression and enhanced invasion and migration

ability compared to the Eca109 and TE-1 cell lines. Quantitative

real-time PCR and western blot analysis showed that the expression

levels of ADAM10 mRNA and protein in the ADAM10 siRNA-transfected

cells were suppressed by ~75 and 60%, significantly lower than

those in the control nonspecific siRNA-transfected and untreated

cells (P<0.01) (Fig. 4),

confirming the specific and efficient blockage of ADAM10 by ADAM10

siRNA in the EC-1 cells in vitro.

Knockdown of ADAM10 inhibits the invasion

and migration of EC-1 cells in vitro

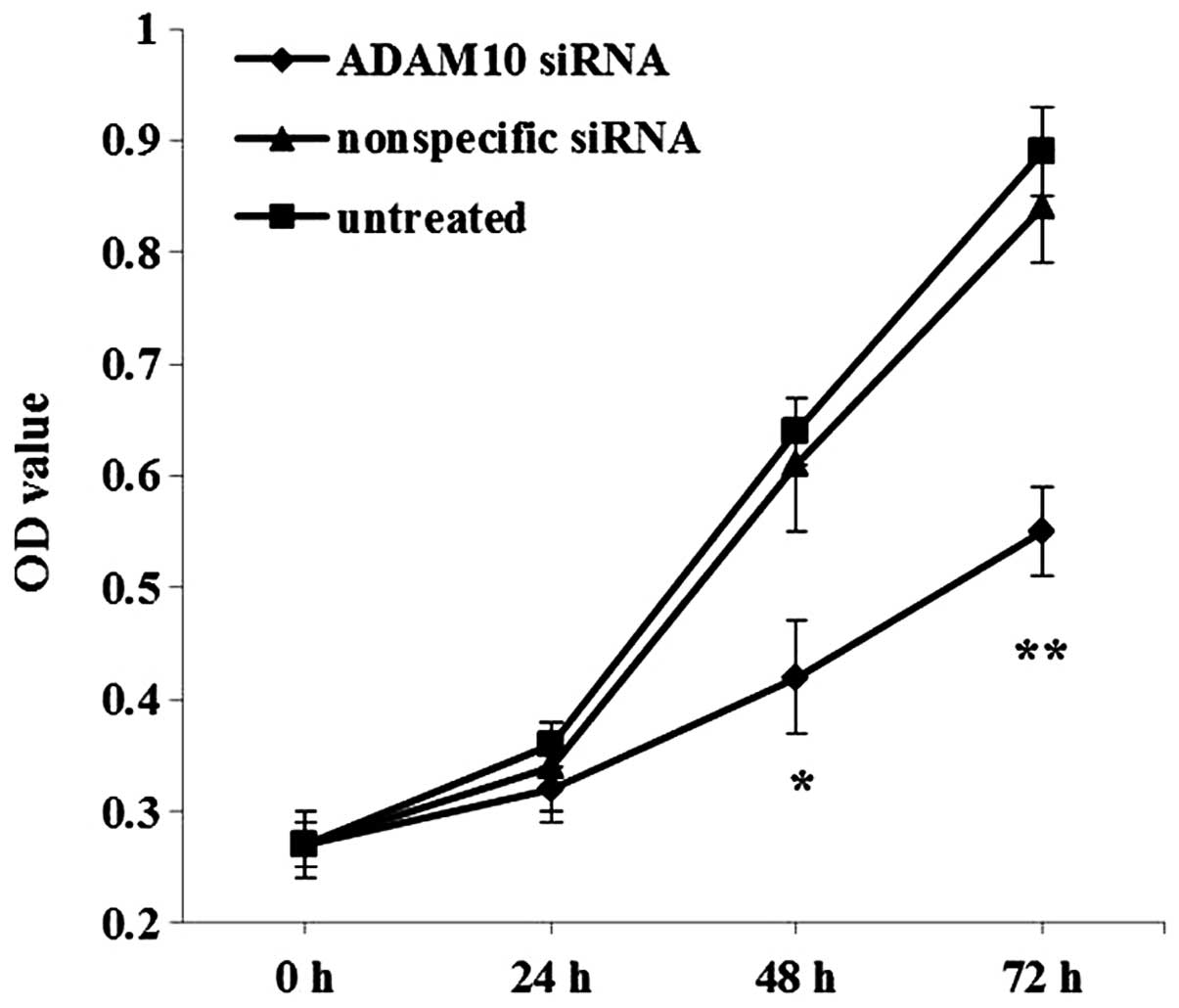

We examined the effect of ADAM10 knockdown on EC-1

cell invasion and migration using a Matrigel invasion and scratch

wound healing assays. Matrigel invasion assay demonstrated that

EC-1 cells transfected with the ADAM10 siRNA exhibited a

significant decrease in the number of cells that traversed the

membrane toward a chemoattractant as compared with the control

nonspecific siRNA-transfected and untreated cells (P<0.05)

(Fig. 5A and B). Furthermore, the

scratch wound healing assay demonstrated that the EC-1 cells

transfected with the ADAM10 siRNA resulted in a significant

decrease in the tumor cell migration distance in comparison to the

control nonspecific siRNA-transfected and untreated cells

(P<0.01) (Fig. 5C and D). These

data indicated that downregulation of ADAM10 inhibited the invasion

and migration of the EC-1 cells in vitro.

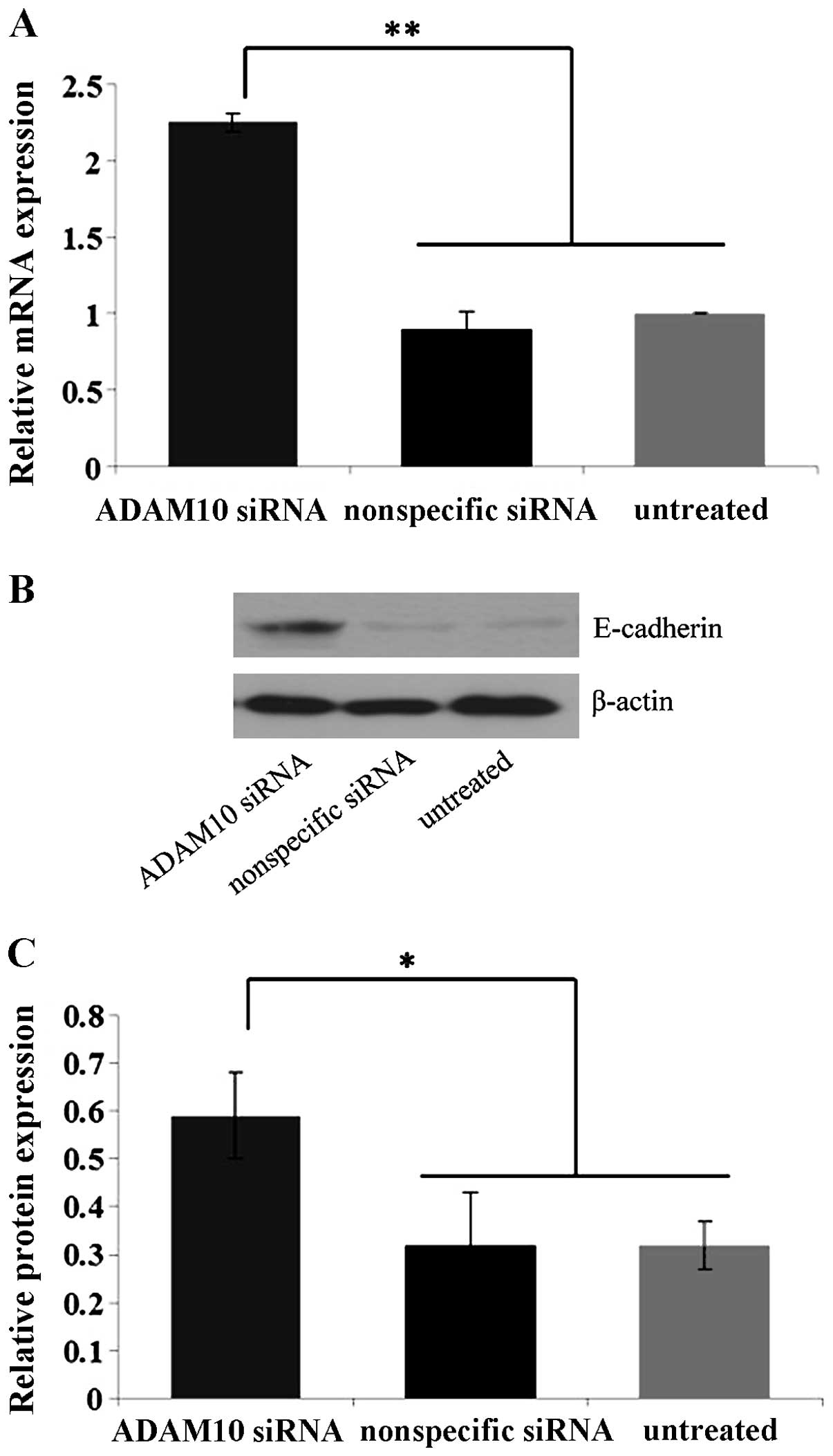

Knockdown of ADAM10 inhibits

proliferation of EC-1 cells in vitro

To evaluate the effect of ADAM10 knockdown on EC-1

cell proliferation, CCK-8 assay was carried out. Compared with the

control nonspecific siRNA-transfected and untreated cells, the EC-1

cells transfected with the ADAM10 siRNA showed significantly

decreased OD values after incubation for 48 (P<0.05) and 72 h

(P<0.01) (Fig. 6), suggesting

that downregulation of ADAM10 inhibited EC-1 cell growth in

vitro.

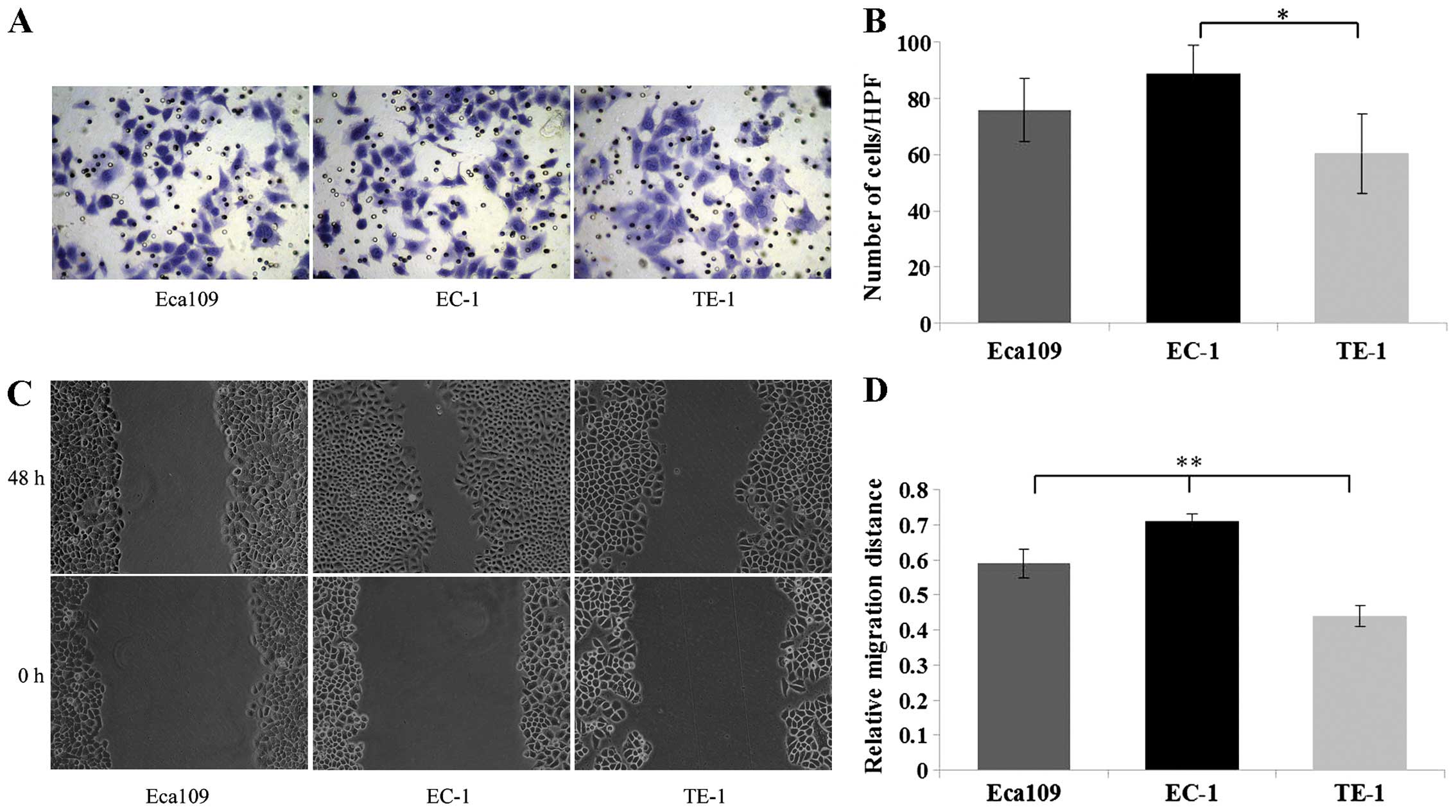

Knockdown of ADAM10 suppresses E-cadherin

expression in EC-1 cells in vitro

As described previously, expression levels of ADAM10

and E-cadherin were inversely correlated in the ESCC tissues. To

further characterize the intrinsic relationship between ADAM10 and

E-cadherin expression and explore the possible impact that ADAM10

exerts on the invasion and metastasis of ESCC, the expression

changes in E-cadherin mRNA and protein in the EC-1 cells

transfected with ADAM10 siRNA were determined by quantitative

real-time PCR and western blot analysis assays. As shown in

Fig. 7, downregulation of ADAM10 by

ADAM10 siRNA dramatically increased E-cadherin mRNA and protein in

the ADAM10 siRNA-transfected EC-1 cells as compared with the

control nonspecific siRNA-transfected and untreated cells

(P<0.05). These results demonstrated that ADAM10 is essentially

involved in E-cadherin cleavage in EC-1 cells in vitro.

Discussion

The role of ADAM10 has been clarified in a variety

of important biological processes, such as cell adhesion (33), cell migration (38), immunoreaction regulation (39,40)

and apoptosis control (41).

However recently, it has emerged as a major and key player in human

diseases. ADAM10 is considered to contribute to Alzheimer's disease

(42) and chronic inflammatory

diseases (43) such as lung

inflammation (44) and eczematous

dermatitis (45); most importantly,

it is overexpressed in many cancers and participates in tumor

progression (18–30). Guo et al (19) demonstrated that ADAM10 protein

expression is significantly increased in human NSCLC tissues,

particularly in metastatic tissues; furthermore, downregulation of

ADAM10 by ADAM10 shRNA reduced the invasion and migration of NSCLC

cells. Consistent with this result, Gaida et al (28) also found that ADAM10 mRNA and

protein were overexpressed in pancreatic carcinoma compared to

normal pancreatic tissues, and ADAM10 silencing markedly reduced

the invasiveness and migration of the tumor cells. However, the

role of ADAM10 in ESCC is not yet well understood.

In the present study, we first examined the

expression levels of ADAM10 mRNA and protein in human ESCC tissues

and cells. As expected, ADAM10 mRNA and protein were both

dramatically elevated in the ESCC tissues and cells in comparison

to these levels in the normal esophageal epithelial mucosa tissues

and cells, suggesting that aberrant activation of ADAM10 plays a

fundamental role in the carcinogenesis of ESCC. Subsequently, the

correlation of ADAM10 with tumor invasion and metastasis was

analyzed. In ESCC tissues, ADAM10 expression was positively

correlated with depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis and high

TNM stage of the cancers; in addition, in ESCC cells, EC-1 with

high ADAM10 expression exhibited higher invasion and migration

ability, whereas TE-1 with low ADAM10 expression exhibited poor

invasion and migration ability. Since EC-1 cells possessed a higher

level of ADAM10 expression and markedly enhanced invasion and

migration ability compared to the Eca109 and TE-1 cells, EC-1 cells

were chosen to perform follow-up experiments to ascertain the

effect of ADAM10 silencing on cell invasion and migration. After

the knockdown of ADAM10 using ADAM10 siRNA, the EC-1 cells

exhibited a significant decrease in the number of invasive cells,

cell migration distance and cell proliferation in comparison to the

control nonspecific siRNA-transfected and untreated cells. All

these above results demonstrated that aberrant ADAM10 is associated

with tumor cell invasion, migration, metastasis and proliferation

in ESCC in vitro and in vivo.

A large body of evidence has shown that tumor

invasion, metastasis and proliferation are associated with the

shedding activity of ADAM10. Nevertheless, the precise mechanism

ADAM10 exerts in the course of ESCC progression is still poorly

understood. ADAM10 promotes tumor progression through the cleavage

of its substrates, such as adhesion molecules (22). E-cadherin, an adhesion molecule, has

been known as an ADAM10 substrate (33). ADAM10 has been implicated in the

shedding of E-cadherin in response to Helicobacter (H.)

pylori infection in gastric cancer cell lines (46). H. pylori infection was found

to correlate with increased ADAM10 expression in gastric cancer

patient samples and to induce ADAM10 expression in gastric cancer

cell lines (47). Indeed, chemical

inhibition or shRNA-mediated knockdown of ADAM10 resulted in

decreased soluble E-cadherin generation in response to H.

pylori infection, suggesting that induction of ADAM10 by H.

pylori in gastric cancer promotes E-cadherin cleavage (46). In the present study, we analyzed the

correlation of ADAM10 with E-cadherin in ESCC tissues and found a

significantly negative correlation between them, suggesting that

ADAM10 promotes the progression of ESCC via E-cadherin shedding.

Accordingly, we next detected the effect of ADAM10 silencing on the

shedding of E-cadherin in EC-1 cells in vitro. The data

showed that the knockdown of ADAM10 dramatically promoted

E-cadherin mRNA and protein in the ADAM10 siRNA-transfected cells

as compared with the control nonspecific siRNA-transfected and

untreated cells, indicating that ADAM10 is critically involved in

the proteolytic processing of E-cadherin in EC-1 cells in

vitro and ADAM10-mediated cleavage of E-cadherin represents a

potent mechanism for regulating invasion, migration, and

proliferation of EC-1 cells. ADAM10 could shed the extracellular

domain of E-cadherin, and allow β-catenin to translocate to the

nucleus (33). Nuclear

translocation of β-catenin further contributes to the activation

and transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation such as

c-myc and cyclin D1 (48). In

addition to enhanced cell proliferation, E-cadherin shedding was

found to simultaneously weaken cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion

and promote dissociation of potentially invasive and metastatic

cells located in primary cancers; moreover, such dissociation could

directly place malignant cells on their pathway to metastasis

(10).

In conclusion, the present study suggests that

ADAM10 is a key regulator in the invasion and metastasis of ESCC,

and may control invasion and metastasis at least in part through

the regulation of E-cadherin activity. Disruption of ADAM10

expression may provide a possible route for therapeutic

intervention for ESCC.

Acknowledgments

This project was financially supported by the

Education Program of Henan Province, China (grant no.

12A310014).

References

|

1

|

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D,

Mathers C and Parkin DM: Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in

2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 127:2893–2917. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhu YH, Fu L, Chen L, Qin YR, Liu H, Xie

F, Zeng T, Dong SS, Li J, Li Y, et al: Downregulation of the novel

tumor suppressor DIRAS1 predicts poor prognosis in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 73:2298–2309. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J and Pisani P:

Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 55:74–108. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Parkin DM, Bray FI and Devesa SS: Cancer

burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer. 37(Suppl

8): S4–S66. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tsai ST, Wang PJ, Liou NJ, Lin PS, Chen CH

and Chang WC: ICAM1 is a potential cancer stem cell marker of

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 10:e01428342015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shimada H, Shiratori T, Okazumi S,

Matsubara H, Nabeya Y, Shuto K, Akutsu Y, Hayashi H, Isono K and

Ochiai T: Have surgical outcomes of pathologic T4 esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma really improved? Analysis of 268 cases

during 45 years of experience. J Am Coll Surg. 206:48–56. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Radisky ES and Radisky DC: Matrix

metalloproteinase-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in

breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 15:201–212. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F and Ferlay J:

Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int J

Cancer. 83:18–29. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Primakoff P and Myles DG: The ADAM gene

family: surface proteins with adhesion and protease activity.

Trends Genet. 16:83–87. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Duffy MJ, Mullooly M, ODonovan N, Sukor S,

Crown J, Pierce A and McGowan PM: The ADAMs family of proteases:

new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer? Clin Proteomics.

8:92011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wolfsberg TG, Primakoff P, Myles DG and

White JM: ADAM, a novel family of membrane proteins containing a

disintegrin and metalloprotease domain: multipotential functions in

cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. J Cell Biol. 131:275–278.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Walker JL, Fournier AK and Assoian RK:

Regulation of growth factor signaling and cell cycle progression by

cell adhesion and adhesion-dependent changes in cellular tension.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16:395–405. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mazzocca A, Coppari R, De Franco R, Cho

JY, Libermann TA, Pinzani M and Toker A: A secreted form of ADAM9

promotes carcinoma invasion through tumor-stromal interactions.

Cancer Res. 65:4728–4738. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mochizuki S and Okada Y: ADAMs in cancer

cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Sci. 98:621–628. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Klein T and Bischoff R: Active

metalloproteases of the a disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM)

family: biological function and structure. J Proteome Res.

10:17–33. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lu X, Lu D, Scully M and Kakkar V: ADAM

proteins - therapeutic potential in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug

Targets. 8:720–732. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Serneels L,

Craessaerts K, Herreman A, Annaert W, Umans L, Lübke T, Lena Illert

A, von Figura K, et al: The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is

essential for Notch signalling but not for alpha-secretase activity

in fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet. 11:2615–2624. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lendeckel U, Kohl J, Arndt M, Carl-McGrath

S, Donat H and Röcken C: Increased expression of ADAM family

members in human breast cancer and breast cancer cell lines. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 131:41–48. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Guo J, He L, Yuan P, Wang P, Lu Y, Tong F,

Wang Y, Yin Y, Tian J and Sun J: ADAM10 overexpression in human

non-small cell lung cancer correlates with cell migration and

invasion through the activation of the Notch1 signaling pathway.

Oncol Rep. 28:1709–1718. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

You B, Shan Y, Shi S, Li X and You Y:

Effects of ADAM10 upregulation on progression, migration, and

prognosis of naso-pharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 106:1506–1514.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jones AV, Lambert DW, Speight PM and

Whawell SA: ADAM 10 is over expressed in oral squamous cell

carcinoma and contributes to invasive behaviour through a

functional association with αvβ6 integrin. FEBS Lett.

587:3529–3534. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ko SY, Lin SC, Wong YK, Liu CJ, Chang KW

and Liu TY: Increase of disintergin metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10)

expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 245:33–43.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shao Y, Sha XY, Bai YX, Quan F and Wu SL:

Effect of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 gene silencing on

the proliferation, invasion and migration of the human tongue

squamous cell carcinoma cell line TCA8113. Mol Med Rep. 11:212–218.

2015.

|

|

24

|

Yue Y, Shao Y, Luo Q, Shi L and Wang Z:

Downregulation of ADAM10 expression inhibits metastasis and

invasiveness of human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. BioMed

Res Int. 2013:4345612013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang W, Liu S, Liu K, Wang Y, Ji B, Zhang

X and Liu Y: A disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM)10 is highly

expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and is associated with tumour

progression. J Int Med Res. 42:611–618. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang YY, Ye ZY, Li L, Zhao ZS, Shao QS and

Tao HQ: ADAM 10 is associated with gastric cancer progression and

prognosis of patients. J Surg Oncol. 103:116–123. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gavert N, Sheffer M, Raveh S, Spaderna S,

Shtutman M, Brabletz T, Barany F, Paty P, Notterman D, Domany E, et

al: Expression of L1-CAM and ADAM10 in human colon cancer cells

induces metastasis. Cancer Res. 67:7703–7712. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gaida MM, Haag N, Günther F, Tschaharganeh

DF, Schirmacher P, Friess H, Giese NA, Schmidt J and Wente MN:

Expression of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 in pancreatic

carcinoma. Int J Mol Med. 26:281–288. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fu L, Liu N, Han Y, Xie C, Li Q and Wang

E: ADAM10 regulates proliferation, invasion, and chemoresistance of

bladder cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 35:9263–9268. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Doberstein K, Pfeilschifter J and Gutwein

P: The transcription factor PAX2 regulates ADAM10 expression in

renal cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 32:1713–1723. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Turner SL, Blair-Zajdel ME and Bunning RA:

ADAMs and ADAMTSs in cancer. Br J Biomed Sci. 66:117–128.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Woods N, Trevino J, Coppola D, Chellappan

S, Yang S and Padmanabhan J: Fendiline inhibits proliferation and

invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by interfering with ADAM10

activation and β-catenin signaling. Oncotarget. 6:35931–35948.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Maretzky T, Reiss K, Ludwig A, Buchholz J,

Scholz F, Proksch E, de Strooper B, Hartmann D and Saftig P: ADAM10

mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell

adhesion, migration, and beta-catenin translocation. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 102:9182–9187. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dittmer A, Hohlfeld K, Lützkendorf J,

Müller LP and Dittmer J: Human mesenchymal stem cells induce

E-cadherin degradation in breast carcinoma spheroids by activating

ADAM10. Cell Mol Life Sci. 66:3053–3065. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lee SB, Schramme A, Doberstein K, Dummer

R, Abdel-Bakky MS, Keller S, Altevogt P, Oh ST, Reichrath J, Oxmann

D, et al: ADAM10 is upregulated in melanoma metastasis compared

with primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 130:763–773. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Bánkfalvi A, Krassort M, Buchwalow IB,

Végh A, Felszeghy E and Piffkó J: Gains and losses of adhesion

molecules (CD44, E-cadherin, and beta-catenin) during oral

carcinogenesis and tumour progression. J Pathol. 198:343–351. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Mancia F and Shapiro L: ADAM and Eph: how

Ephrin-signaling cells become detached. Cell. 123:185–187. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hasegawa-Ishii S, Shimada A, Inaba M, Li

M, Shi M, Kawamura N, Takei S, Chiba Y, Hosokawa M and Ikehara S:

Selective localization of bone marrow-derived ramified cells in the

brain adjacent to the attachments of choroid plexus. Brain Behav

Immun. 29:82–97. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Gibb DR, Saleem SJ, Chaimowitz NS, Mathews

J and Conrad DH: The emergence of ADAM10 as a regulator of

lymphocyte development and autoimmunity. Mol Immunol. 48:1319–1327.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schulte M, Reiss K, Lettau M, Maretzky T,

Ludwig A, Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Janssen O and Saftig P: ADAM10

regulates FasL cell surface expression and modulates FasL-induced

cytotoxicity and activation-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ.

14:1040–1049. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Endres K and Fahrenholz F: The role of the

anti-amyloidogenic secretase ADAM10 in shedding the APP-like

proteins. Curr Alzheimer Res. 9:157–164. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Crawford HC, Dempsey PJ, Brown G, Adam L

and Moss ML: ADAM10 as a therapeutic target for cancer and

inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 15:2288–2299. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dreymueller D, Uhlig S and Ludwig A:

ADAM-family metalloproteinases in lung inflammation: potential

therapeutic targets. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

308:L325–L343. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Maretzky T, Scholz F, Köten B, Proksch E,

Saftig P and Reiss K: ADAM10-mediated E-cadherin release is

regulated by proinflammatory cytokines and modulates keratinocyte

cohesion in eczematous dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol.

128:1737–1746. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Schirrmeister W, Gnad T, Wex T,

Higashiyama S, Wolke C, Naumann M and Lendeckel U: Ectodomain

shedding of E-cadherin and c-Met is induced by Helicobacter pylori

infection. Exp Cell Res. 315:3500–3508. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yoshimura T, Tomita T, Dixon MF, Axon AT,

Robinson PA and Crabtree JE: ADAMs (a disintegrin and

metalloproteinase) messenger RNA expression in Helicobacter

pylori-infected, normal, and neoplastic gastric mucosa. J Infect

Dis. 185:332–340. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Balzer EM and Konstantopoulos K:

Intercellular adhesion: mechanisms for growth and metastasis of

epithelial cancers. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 4:171–181.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|