Introduction

Melanoma is one of the most aggressive types of skin

cancer, and is the most deadly cutaneous neoplasm (1). In Western populations, although it

accounts for less than 5% of all skin cancers, melanoma is one of

the most common cancers among young adults and is one of the most

common causes of death (2,3). Although melanoma is relatively rare,

the increasing incidence over the past two decades has raised a

major health concern, and once metastasis to distant organ occurs,

the prognosis becomes extremely poor. Metastatic melanoma is

resistant to many types of chemotherapeutic agents (4). To date, dacarbazine is considered to

be the reference single agent for the management of advanced

melanoma, and dacarbazine treatment exhibits effective responses in

~15–25% of patients (4). However,

in metastatic melanoma patients, the 6-year median survival rate is

extremely low (5).

The embryonic protein Nodal, belongs to the

transforming growth factor (TGF)-β family, and plays critical roles

in maintaining the self-renewal capacity and pluripotency of human

embryonic stem cells (hESCs) (6,7).

Emerging evidence has revealed its involvement in promoting the

growth and progression of various types of cancer, including

melanoma, glioma, breast, prostate and endometrial cancer (8–12). In

both melanoma and its CSC subpopulation, accounting for 0.5% of

melanoma cancer cells, activated Nodal/Activin signaling promotes

tumorigenicity and maintains self-renewal capacity (13). In most cases, Nodal induces signal

transduction after being cleaved by the proprotein convertases

Furin or Pace4 to remove an N-terminal prodomain from precursor

Nodal (proNodal) (14). A recent

report also revealed that proNodal, but not mature Nodal, induces

Nodal signaling transduction (15).

However, it is still unknown which forms of Nodal, proNodal or

mature Nodal regulates CSC properties.

Hypoxia, as one of the factors critical in the

biological processes of CSCs, plays crucial roles in the activation

of pathways involved in the maintenance of CSC functions (16,17),

and is implicated in the development of chemoresistance. It was

recently uncovered that hypoxia exposure converted non-cancer stem

cells to CSCs in the melanoma cancer cell line A375 (18). Furthermore, Quail et al found

that, in melanoma and breast cancer cells, hypoxia induced Nodal

expression and caused promotion of cell invasion and angiogenic

phenotypes, suggesting that Nodal may also be regulated by hypoxia

in pancreatic CSCs (19).

In the present study, we investigated the effect of

hypoxia exposure on Nodal expression and CSC properties in melanoma

cancer cells. Our study revealed that hypoxia-induced Nodal

enhanced CSC properties, including self-renewal capacity, sphere

forming ability and chemoresistance. Moreover, both proNodal and

mature Nodal induced by hypoxia exposure contributed to a higher

tumorigenic potential.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, sphere formation and

treatments

Human melanoma cancer cell line, A375, was purchased

from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA)

and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

For sphere formation, 2×105 cells were

seeded in each 6-well plate and cultured with DMEM-F12 (1:1) medium

containing human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 10 ng/ml;

PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), human epidermal growth factor

(EGF; 20 ng/ml; PeproTech) and 2% B27 (Life Technologies; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Every three days, the medium was

half-refreshed.

Hypoxic cultures were carried out in a humidified

hypoxia workstation Invivo2 400 model (Baker Ruskinn

Technology Ltd., Bridgend, UK). Briefly, medium was pre-exposed to

20% O2, 5% O2, 2% O2, 1%

O2, or 0.5% O2 balanced with nitrogen and 5%

CO2. Then, the cells were cultured in pre-treated medium

and maintained in corresponding conditions for 24 or 48 h.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with Laemmli sample buffer (50 mM

Tris pH 6.8, 1.25% SDS, 10% glycerol) and heated at 100°C for 15

min for denaturalization. SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (6–12% gradient)

was performed to fractionate total protein. Blots were then

incubated with the following primary antibodies purchased from

Abcam: CD44 (cat. no. ab157107), CD133 (cat. no. ab19898), Nanog

(cat. no. ab21624), Sox2 (cat. no. ab97959), β-actin (cat. no.

ab8226), cleaved Nodal (cat. no. ab81287), proNodal (cat. no.

ab109317), ALK4 (cat. no. ab109300), ALK7 (cat. no. ab111121),

Smad2/3 (cat. no. ab202445), p-Smad2 (cat. no. ab53100), p-Smad3

(cat. no. ab52903), HK-II (cat. no. ab104832), Glut-I (cat. no.

ab115730), PDK-1 (cat. no. 110025) and HIF-1α (cat. no. ab113642).

Primary antibodies were diluted at 1:1,000 in PBS and incubated

with the blotted membrane at room temperature for 2 h. After three

washes with PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 at room

temperature, goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (cat. no. ab97040)

(for β-actin, PDK-1 and HIF-1α) was used; for other antibodies,

goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat. no. ab7090) was used.

β-actin was used as a loading control. Proteins were detected using

ECL (Life Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

visualized on X-ray film (Kodak, Japan).

Lentivirus production and cell

infection

We obtained lentivirus-based shRNA constructs

targeting human Nodal (shNodal;

5′-CCGGGCGGTTTCAGATGGACCTATTCTCGAGAATAGGTCCATCTGAAACCGCTTTTTG-3′)

(LV-shNodal) as well as a control shRNA-expressing plasmid

(shScrambled;

5′-CCGGCTATGGACGCTCTTATGTACTGGCGCCAGTACATAAGAGCGTCCATAGTTTTTG-3′)

(LV-shScrambled). The oligonucleotides were cloned into the

shRNA-pGCL-GFP lentiviral vector (Shanghai Genchem, Shanghai,

China), respectively. Infectious viruses were produced by

contransfecting the lentiviral vectors and packaging constructs

(pHelper1.0 and pHelper2.0) into 293T cells using Lipofectamine™

reagent (Life Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The lentiviruses containing the Nodal coding

sequences (LV-Nodal) for overexpressing Nodal were produced by

Genomeditech Company (Shanghai, China), which were labeled with

RFP. Lentiviruses containing the empty vector (LV-vector) were used

as a negative control. Cells were transduced with the packaged

lentiviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:10

(cell:virus) (20) and 72-h later,

the transduced cells were subsequently collected for further

analysis.

Glucose uptake assay

For measuring glucose uptake, 1×106 cells

were plated in 6-well plates overnight for attaching. The cells

were incubated in glucose-free medium for 30 min at 37°C in a

CO2 incubator and then 2-[3H]deoxyglucose at

1 µCi was added into the medium for a 2-h incubation. The cells

were washed with ice-cold PBS three times, and transferred to

scintillation vials for counting as described previously (21,22).

Lactate measurements

Cells (1×106) were plated in 6-well

plates overnight and the medium was replaced with serum-free medium

for 12 h. The supernatant was collected and diluted with PBS. For

measuring lactate, the EnzyChrom™ L-Lactate assay kit (BioAssay

Systems, Hayward, CA, USA) was employed following the

manufacturer's instruction and was measured at 565 nm using a

microplate reader (Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader; BioTek,

Winooski, VT, USA).

ATP production

Cells (1×106) were plated in 6-well

plates and allowed to adhere overnight. ATP Lite assay kit

(PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was employed to measure ATP

production following the manufacturer's instruction.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

detection

Total intracellular ROS was assessed by flow

cytometry using the dichlorofluorescein (DCF) oxidation assay. The

intracellular ROS oxidizes cleaved DCFH-DA which enters into cells.

Target cells (5×105) were incubated with DCFH-DA (10 µM)

for 1 h at 37°C, followed by 3 washes with ice-cold PBS, and ROS

fluorescence was analyzed using 3 laser Navios flow cytometers

(Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) with green fluorescence channel

(FL1).

Cell death analysis

Cells (5×104) were collected, washed in

PBS and stained with 1 µg/ml PI for 30 min in darkness. The stained

cells were washed with ice-cold PBS for three times and analyzed by

flow cytometry using 3 laser Navios flow cytometers. PI-positive

cells were regarded as dead cells, and the percentage of dead cells

was determined.

Cell viability assay

Cells were grown in 96-well plates, and viable cell

numbers were determined with the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell

Viability Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the

manufacturer's guide.

Transwell cell invasion assays

Matrigel (Millipore Corp., Darmstadt, Germany) was

diluted 1:2 in DMEM/F-12 and 60 µl of diluted Matrigel was added to

the upper chamber of Transwell plates. Then, the chambers were

incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 2 h.

Single-cells were resuspended in DMEM/F-12 and seeded into the

upper chamber at a density of 2×104 cells/well.

Subsequently, 600 µl of DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 20 ng/ml EGF,

10 ng/ml bFGF and 2% B27 was added to the lower chamber. After a

24-h incubation, the inserts were collected, and the cells on the

lower surface were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with

crystal violet for 15 min. The cells in five random views were

counted under a X71 (U-RFL-T) fluorescence microscope (Olympus,

Melville, NY, USA).

Cloning of cleavage-resistant Nodal

precursor (mut-proNodal)

The expression vector for mut-proNodal has been

described (23) and the lentiviral

vector containing mut-proNodal coding sequence (LV-mut-proNodal)

was packaged as previously described (23).

Serial replating assay

Cells were replated at a clonal density (2,000

cells/well) and cultured in serum-free medium supplemented with 2%

B-27, 10 ng/ml EGF and 20 ng/ml bFGF. The medium was half-replaced

every 3 days. After 10 days, PBS-washed cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min

and washed again with PBS, and the colonies were counted. For

replating, the same amount of cells was plated in serum-free

medium. After 10 days, the same procedure was performed three

times.

Statistical analysis

All data were normalized to control values for each

assay and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Multigroup comparisons of the means were carried out by one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with post hoc contrasts by

Student-Newman-Keuls test. Significance was chosen as

P<0.05.

Results

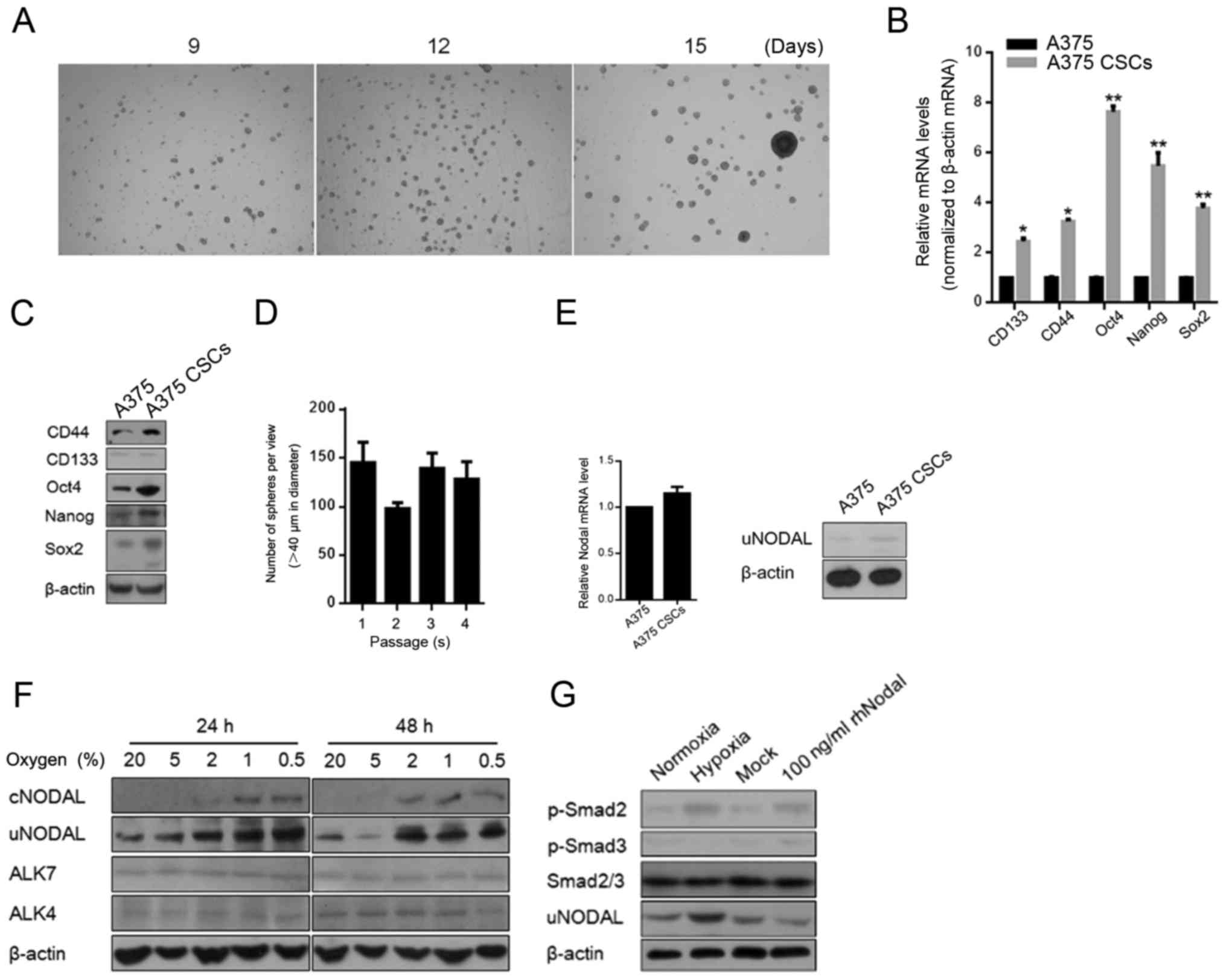

Hypoxia upregulates the expression of

Nodal protein in A375 CSCs

Serum-free medium culturing was used for enriching

the stem-like cells from A375 cells in this study. After 14 days of

culturing, spheres were completely formed and showed morphological

similarity with embryonic tissues (Fig.

1A). In order to characterize the stem-like characteristics of

the A375 subpopulation enriched using SFM culturing, we examined

the expression levels of several stem cell markers (CD133, CD44,

OCT4, Nanog and SOX2) and found that all were upregulated in the

A375 CSCs compared to levels in the A375 cells at both the mRNA and

protein levels (Fig. 1B and C). We

further used in vitro serial replating assay to examine the

self-renewal capacity of the A375 CSCs and the results confirmed

the stem-like property (Fig. 1D).

Nodal is reported to be restricted to embryonic tissues and hESCs,

and re-emerges during tumorigenesis in several types of cancers

(24). This promoted us to assess

the differential expression of Nodal in A375 and A375 CSCs.

Unexpectedly, compared to A375, no detectable difference in Nodal

was found in the A375 CSCs (Fig.

1E).

For detecting the regulatory factor of tumor

progression, hypoxia, which is an important environmental change in

many cancers, was employed to determine its effect on the

regulation of Nodal protein expression. We exposed A375 CSCs to

varying levels of O2 for 24 and 48 h. Uncleaved Nodal

protein (uncleaved NODAL, uNODAL, 39 kDa) and cleaved and secreted

Nodal protein (cleaved NODAL, cNODAL, 15 kDa) were detected in

whole cell lysate and in concentrated medium by ultrafiltration

individually. The data showed that exposure of A375 CSCs to varying

O2 concentrations (0.5–20% O2) for 24 and 48

h upregulated the Nodal protein level at concentrations ≤2%

O2 (Fig. 1F). We also

detected the expression pattern of Nodal receptor, ALK4/7, and no

detectable changes were observed (Fig.

1F). Surprisingly, hypoxic exposure undetectably disturbed

Nodal mRNA levels, indicating its post-transcriptional regulation

on Nodal (data not shown). We then investigated whether Nodal/Nodal

receptors are coupled to Smad signaling pathway by detecting

phosphorylated Smad2/3 in A375 CSCs. Western blot analysis showed

that Smad2, but not Smad3, was phosphorylated in A375 CSCs exposed

to hypoxia at oxygen concentration of 0.5% and co-incubated with

100 ng/ml rhNodal (as a positive control) (Fig. 1G).

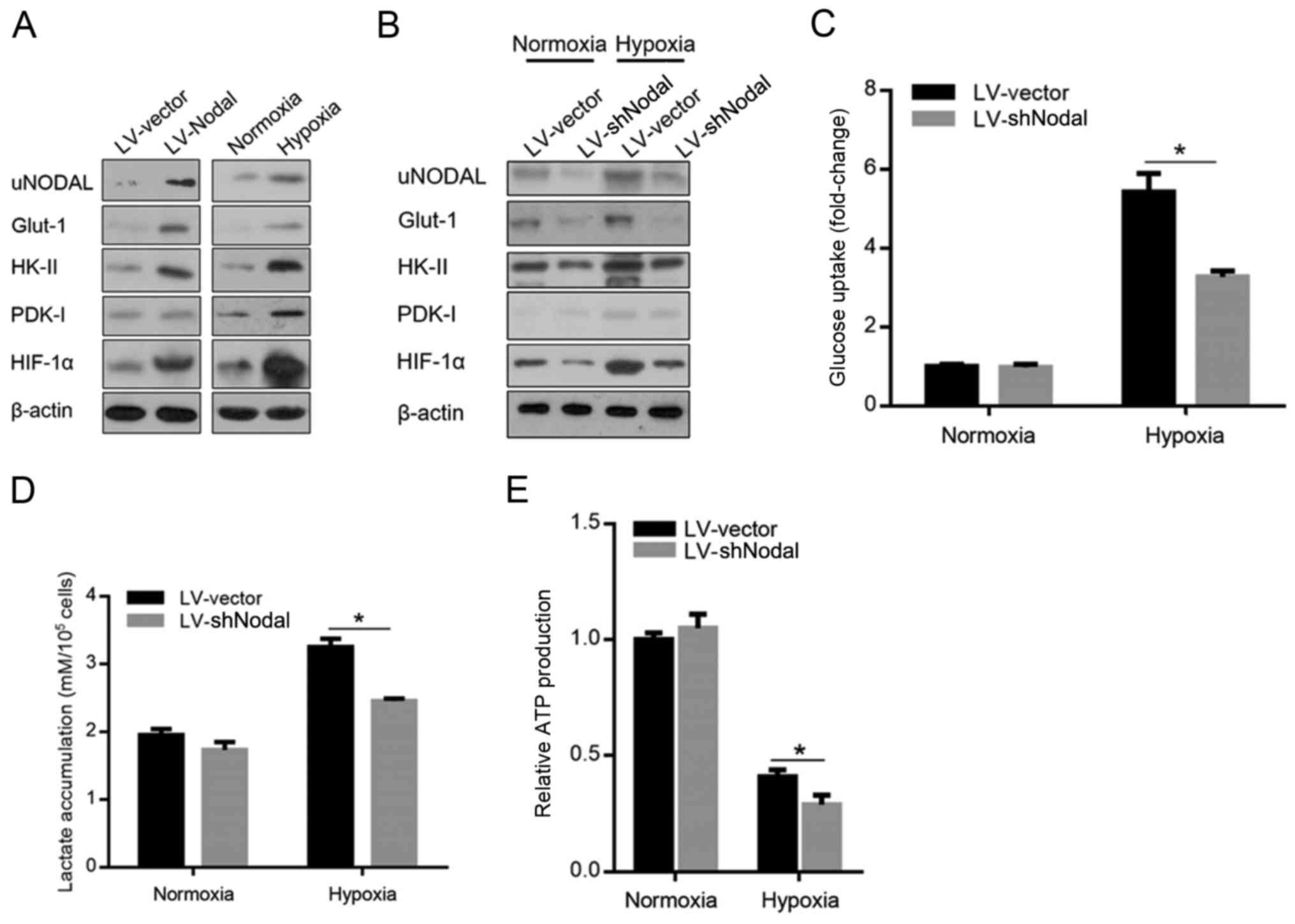

Hypoxic-induced Nodal enhances glucose

uptake and promotes glycolysis

Nodal protein expression was reported to be

positively correlated with hexokinase (HK)-II, glucose transporter

(Glut)-1 and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)-1 by activating

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, which is induced by hypoxic

exposure and directly regulates energy metabolism (25–27).

Firstly, by introducing Nodal, we confirmed the positive

correlation of Nodal with HK-II, Glut-1, PDK-1 and HIF-1α in A375

CSCs (Fig. 2A), and hypoxia

exposure exerted similar effects. For ascertaining whether

hypoxia-induced Nodal contributes to the upregulation of HIF-1α,

HK-II, Glut-1 and PDK-1, in hypoxia-induced A375 CSCs transfected

with Nodal shRNA, semi-quantitative western blotting was performed.

As shown in Fig. 2B, hypoxia

exposure markedly upregulated all these proteins, and Nodal

knockdown detectably attenuated their protein levels. In

hypoxic-exposed A375 CSCs, knockdown of Nodal significantly

decreased 2-[3H]deoxyglucose uptake (Fig. 2C) and lactate accumulation (Fig. 2D). We next assessed whether Nodal

contributes to the regulation of ATP production. As expected, Nodal

knockdown negatively affected ATP production (Fig. 2E).

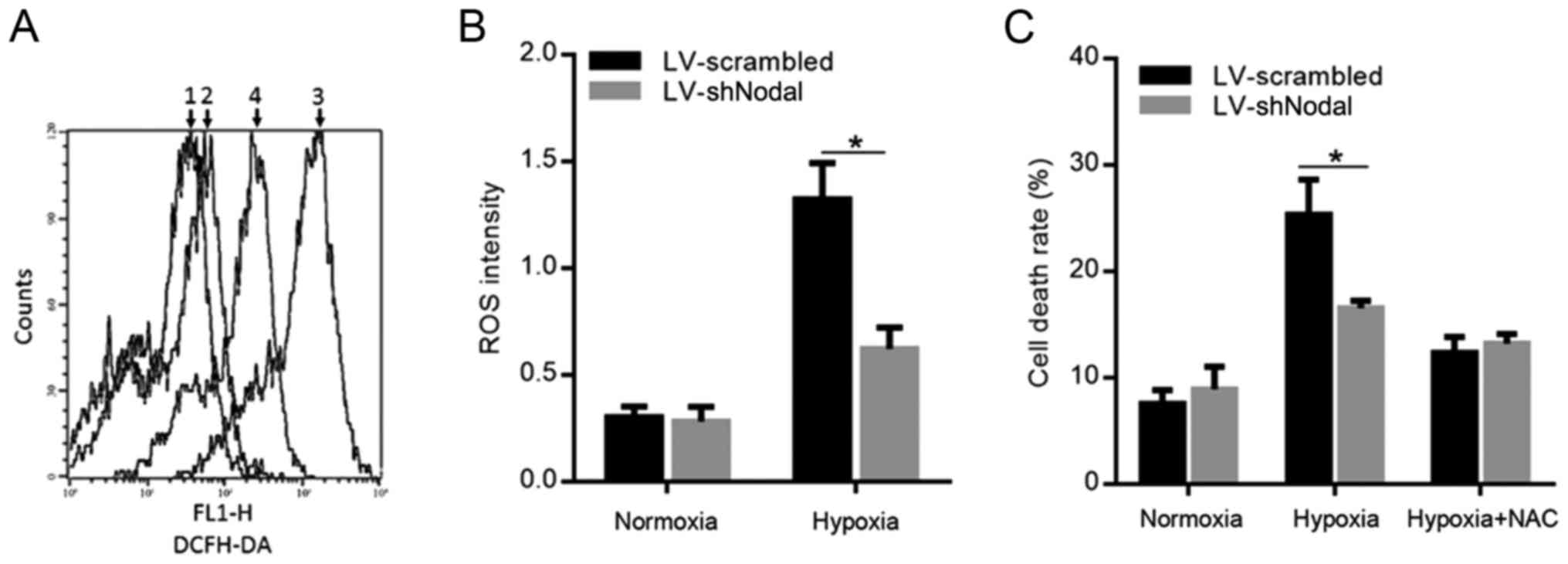

Nodal expression prevents excess ROS

production and apoptosis in A375 CSCs

It has been reported that promotion of glycolysis

prevents excess ROS production (28). Thus, we examined whether Nodal

expression regulates ROS production. As shown in Fig. 3A, hypoxia exposure promoted ROS

production and knockdown of Nodal markedly decreased accumulated

ROS, which was confirmed quantitatively (Fig. 3B). As ROS is important for

hypoxia-induced cell death, we analyzed whether Nodal modulates

ROS-induced cell death in A375 CSCs. Knockdown of Nodal expression

sensitized A375 CSCs against hypoxia-induced cell death, whereas

the addition of ROS scavenger, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) slightly

abolished the effect of Nodal, suggesting that Nodal enhances ROS

detoxification mechanisms (Fig.

3C).

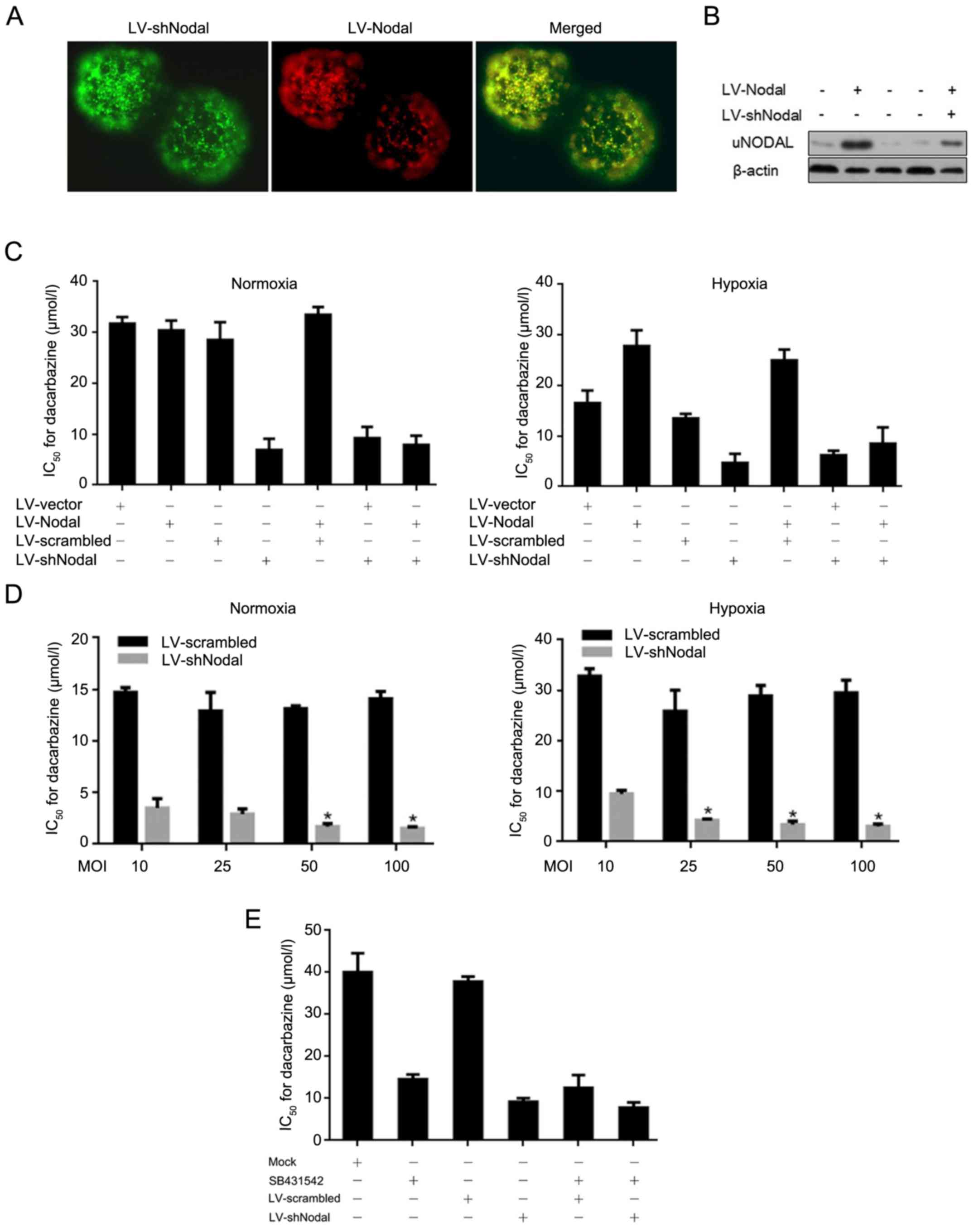

Hypoxic-induced Nodal partially

contributes to decarbazine resistance in A375 CSCs

For investigating the roles of Nodal in A375 CSCs,

we produced lentiviral particles coding for shRNA targeting the

Nodal mRNA (LV-shNodal and LV-scrambled) and for overexpressing

Nodal mRNA (LV-Nodal and LV-vector). The infectious efficacy and

Nodal protein levels were detected (Fig. 4A and B). A375 CSCs were infected

with LV-Nodal, LV-shNodal, or LV-Nodal/LV-shNodal to determine

their IC50 value for dacarbazine, respectively. As

expected, Nodal induced by hypoxic exposure and overexpressed by

lentiviral infection desensitized A375 CSCs to dacarbazine, and

knockdown of Nodal by LV-shNodal sensitized A375 CSCs to

dacarbazine, indicating the critical role of Nodal protein in

dacarbazine response (Fig. 4C). For

further confirm the necessity of Nodal on dacarbazine

desensitization, A375 CSCs were infected by LV-Nodal or LV-shNodal

at MOI 10, 25, 50 and 100 to determine their IC50. With

the decrease in Nodal protein, A375 CSCs presented more sensitivity

to dacarbazine (Fig. 4D). However,

in hypoxic-exposed A375 CSCs, upregulation of Nodal protein caused

no detectable changes in the sensitization to dacarbazine, possibly

because of its high endogenous level (data not shown). We then

blocked the Nodal signal by SB431542 treatment in A375 CSCs to

ascertain whether uncleaved precursor (proNodal) is involved in

dacarbazine response. Surprisingly, after SB431542 blockage,

knockdown of Nodal still sensitized hypoxic-exposed A375 CSCs to

dacarbazine, indicating that proNodal also contributes to

dacarbazine resistance in an undetermined manner (Fig. 4E).

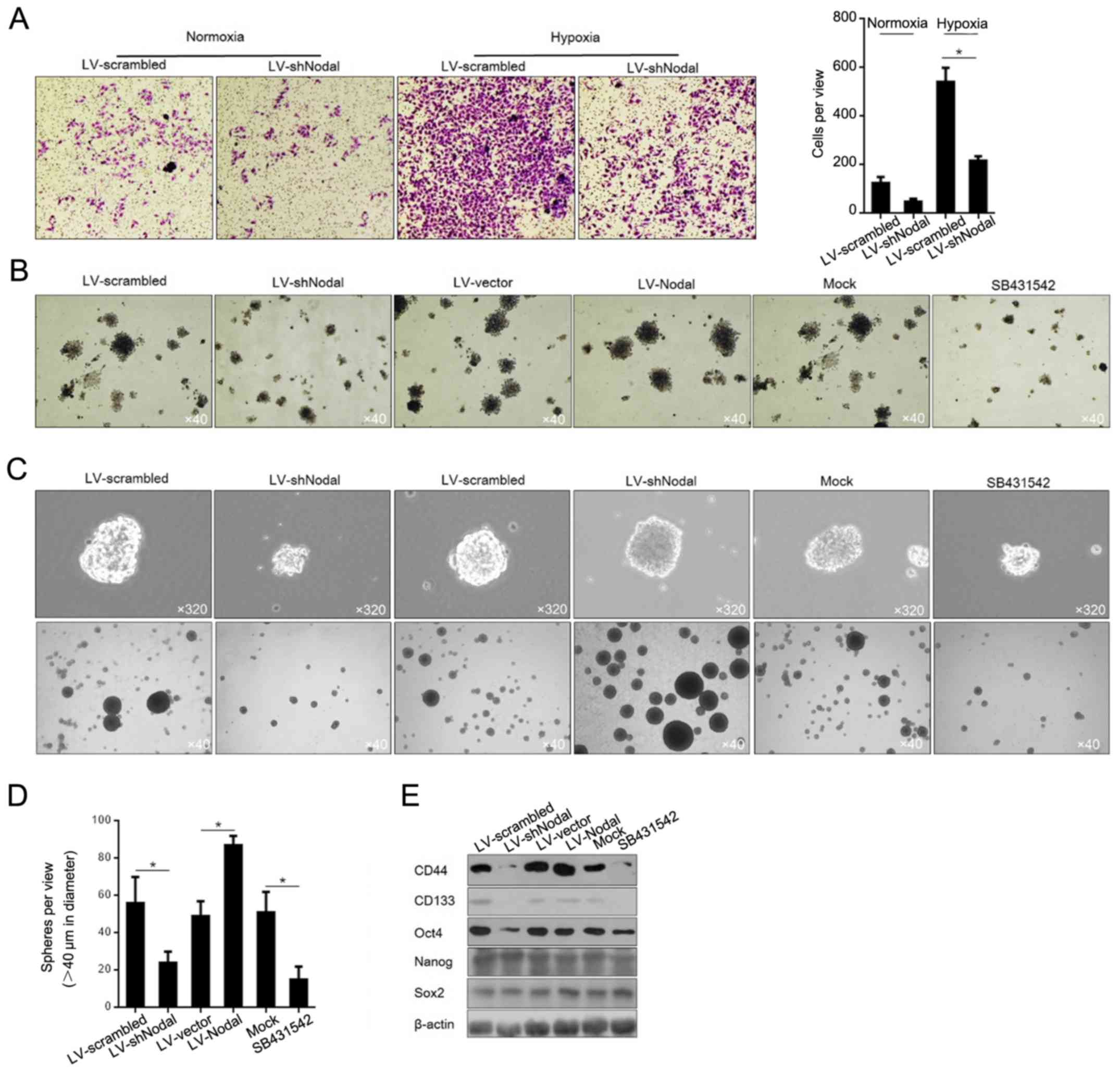

Hypoxic-induced Nodal promotes cell

invasion and maintains cell stemness, but not proliferation in A375

CSCs

Because of its tight association with malignancies

in cancer and CSCs (29,30), we assessed the effects of

hypoxic-induced Nodal on proliferation, invasion and preservation

of stemness. Hypoxia exposure slightly affected the distribution of

cell cycle phases and cell viability (data not shown), possibly due

to high endogenous Nodal protein level. Then, the invasiveness

affected by hypoxia exposure was detected, and the results showed

that hypoxia exposure promoted invasion via upregulation of Nodal

in A375 CSCs (Fig. 5A). For

evaluating the capacity of self-renewal properties in A375 CSCs,

colony formation and sphere formation assays were employed. The

colony formation results demonstrated that both knockdown of Nodal

expression and blockage by SB431542 in A375 CSCs apparently reduced

colony formation (Fig. 5B). To

further characterize the effects of hypoxia-induced Nodal on A375

CSCs, we overexpressed Nodal by lentiviral infection to simulate

upregulation of hypoxic-induced Nodal, and to determine the sphere

formation ability. Similarly, upregulated Nodal expression promoted

the formation of spheres in the A375 CSCs in SFM (Fig. 5C). Simultaneously, both knockdown of

Nodal expression and blockage by SB431542 in A375 CSCs caused

dissociation of spheres (Fig. 4C).

We counting the spheres ≥40 µm in diameter, and found that Nodal

expression promoted the sphere forming rate, and Nodal knockdown

and SB431542 exposure diminished the sphere forming rate (Fig. 5D). By considering the regulatory

roles of Nodal on stemness maintenance, we next evaluated its

effects on related genes, including CD44, CD133, Oct4, Nanog, and

Sox2. Without disturbing Nanog and Sox2 levels, expression of Nodal

was positively correlated with CD44, CD133 and Oct4 (Fig. 5E), which was consistent with its

effect on spheroid morphology.

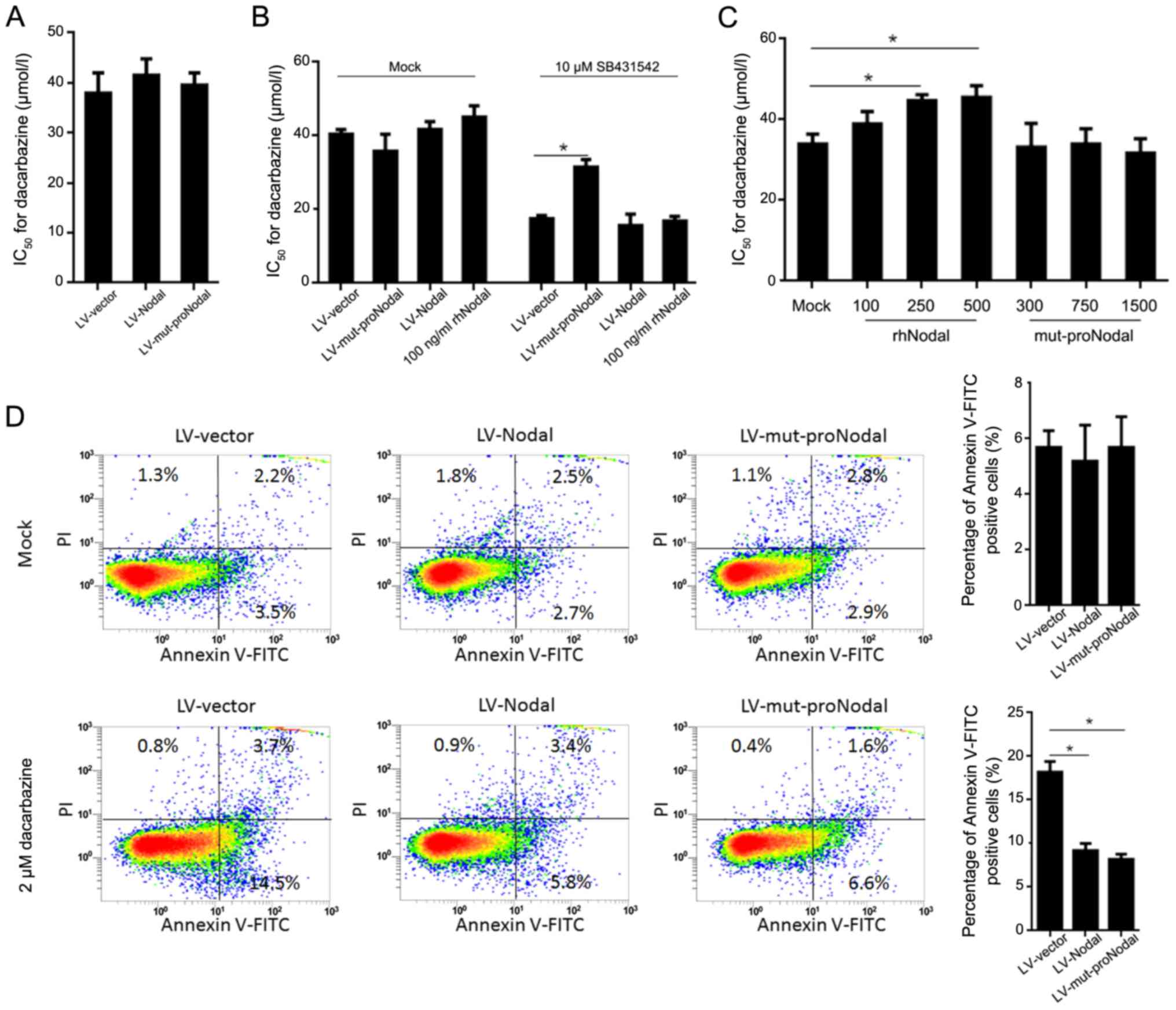

Both cleaved Nodal and proNodal

contribute to dacarbazine resistance in A375 CSCs

Nodal is secreted as a precursor protein by

endoproteolytic cleavage. It has been revealed that proNodal

displays a subset of activities at physiological concentrations

(31–33). By considering the potential

involvement of proNodal in physiological processes of A375 CSCs, we

investigated whether the precursor and/or cleaved Nodal contribute

to dacarbazine resistance. We first examined whether a recombinant

Nodal cleavage mutant (mut-proNodal) which is resistant to specific

cleavage can regulate dacarbazine sensitization in A375 CSCs. In

A375 CSCs infected with LV-mut-proNodal, dacarbazine resistance was

not disturbed, and SB431542-pretreated A375 CSCs were desensitized

to dacarbazine after LV-mut-proNodal infection (Fig. 6A and B). For ascertaining whether

mut-proNodal functions via recognizing the Nodal receptor, we

exposed A375 CSCs to purified mut-proNodal and found that, rhNodal

but not mut-proNodal exposure desensitized A375 CSCs to dacarbazine

and was reversed by SB431542 co-exposure (Fig. 6C). For further confirming the

apoptosis induced by dacarbazine treatment, Annexin V-PI staining

was analyzed by flow cytometry. The results showed that, after 2 µM

dacarbazine treatment for 24 h, introduction of mut-proNodal

significantly reduced the apoptotic rate, with a robustness similar

to that observed for LV-Nodal (Fig.

6D). Unexpectedly, introduction of mutant-proNodal failed to

regulate self-renewal capacity and sphere formation (data not

shown), indicating that proNodal might function via an independent

undetermined manner.

Discussion

In the present study, we report that hypoxia

exposure of A375 CSCs enhanced the CSC phenotype, tumor formation,

invasion and chemoresistance. Hypoxia exposure upregulated Nodal

protein and subsequently activated downstream signaling pathways.

Blockage of Nodal pathway using ALK-4/5/7 inhibitor (SB431542; 10

µM) inhibited the CSC properties of hypoxia-exposed A375 CSCs.

Moreover, it was revealed that hypoxic-induced Nodal enhanced

glucose uptake and promoted glycolysis, and subsequently exerted

protective effects on A375 CSCs via preventing ROS

accumulation.

Nodal plays essential roles in the processes of

embryonic development and maintains the pluripotent properties of

stem cells during embryogenesis (34,35).

Generally, Nodal expression is specifically expressed in embryonic

tissues and hESCs and is undetectable in most highly differentiated

tissues. However, it is found to be upregulated and contributes to

increasing cancer cell aggressiveness, tumorigenicity and

metastasis in several types of cancer, including melanoma, breast

cancer and melanoma (36–38). These findings indicate that the

abnormal expression of Nodal promotes cancer cell proliferation,

invasion and migration and inhibits apoptosis. It was reported that

hypoxia exposure induces Nodal expression predominantly mediated

via an HIF-1α-dependent pathway in melanoma cells. However, the

effect of hypoxia exposure on melanoma CSCs is still unknown. In

the present study, to further explore the regulatory effect of

hypoxia exposure on Nodal expression and CSC properties in A375

CSCs, we exposed A375 CSCs to hypoxia and found that Nodal was

induced after hypoxia exposure. Overexpression of Nodal increased

the number and size of spheroids and promoted colony formation. In

addition, semi-quantitative western blot analysis revealed that

induced Nodal protein resulted in increased expression of CD44,

CD133 and Oct4. For confirming whether induced Nodal expression by

hypoxia exposure was responsible for these changes in expression,

Nodal was knocked down using shNodal which subsequently resulted in

a reversal of CSC properties in A375 CSCs in regards to the

expression of CSC markers. ALK4/5/7 blockage using SB431542

presented similar effects on CSC properties of A375 CSCs with Nodal

knockdown, revealing that Nodal signaling was necessary for

regulating A375 CSC features.

Nodal is a member of the TGF-β superfamily of

secreted proteins that signals through the serine/threonine kinase

receptor family triggering the phosphorylation of Smad2 and 3

(6,7). It is worth testing the regulation of

Nodal induced by hypoxia on TGF-β in further studies. It was

reported that Nodal protein expression is positively correlated

with HK-II, Glut-I and PDK-1 via activation of HIF-1α (24,25).

Consistently, in the present study, it is found that, Nodal

upregulated by hypoxia exposure promoted HK-II, Glut-1, PDK-1 and

HIF-1α in A375 CSCs. Knockdown of Nodal remarkably attenuated

hypoxic-induced upregulation of glycolysis-associated genes,

indicating the critical role of Nodal in controlling glycolysis. By

promoting glycolysis, hypoxic-induced Nodal prevented ROS

accumulation and thus exerted protective effects on A375 CSCs.

Instead of imaging ROS staining in spheres, we quantified ROS

accumulation due to technical difficulty. However, it is still

unknown how Nodal regulates this process.

Nodal is widely known as an inducer for

mesendogermal genes and gastrulation movements within the epiblast

after being activated and secreted after cleavage (32,39).

It was also found that uncleaved Nodal (proNodal) governs the

expression of downstream target genes, including sonic hedgehog

(shh) and FGFR3 transcriptionally or post-transcriptionally,

indicating that proNodal is potentially involved in physiological

regulation (15). Processed Nodal

activates Nodal/Activin signaling to maintain quiescence and

chemoresistance in melanoma cancer stem cells (40), however, whether proNodal takes part

in these processes remains unknown. In the present study,

introduction of mut-proNodal desensitized A375 CSCs pretreated with

10 µM SB431542, indicating that it functions independent of the

ALK4/7 receptor. This was further confirmed by exposure of A375

CSCs to purified rhNodal or mut-proNodal, in which mut-proNodal

failed to influence the chemosensitivity of the A375 CSCs to

dacarbazine. By performing apoptotic analysis, introduction of

mut-proNodal significantly induced desensitization of A375 CSCs to

dacarbazine, and revealed it functions intracellularly independent

with cell surface receptor ALK4/7.

In conclusion, this study provides novel information

concerning the effects of hypoxia exposure on Nodal expression and

functions in A375 CSCs. Our results revealed that hypoxia exposure

upregulated Nodal expression and activated Nodal signal on Smad2/3,

contributed to maintain stemness and promotes malignanct potential,

including invasion, sphere formation and colony formation.

Importantly, uncleaved Nodal precursor, proNodal, desensitized A375

CSCs to dacarbazine, without disturbing self-renewal capacity and

sphere formation, independent of mature Nodal receptor ALK4/7.

Further research is required to reveal the novel mechanism. Taken

together, we revealed that hypoxia-induced Nodal promoted malignant

behavior and chemoresistance in melanoma cancer cell A375.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms H.M. Shi for English

editing.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are

available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

LH and CY conceived and designed the study. LH, CJJ,

WX, HE and ZZY performed the experiments. LH wrote the manuscript.

CY reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects

of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any

part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Cell lines were used in the study. No human tissues

were used nor animal studies were carried out and thus no ethical

approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of

interests.

References

|

1

|

Miller AJ and Mihm MC: Melanoma. N Engl J

Med. 355:51–65. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Godar DE: Worldwide increasing incidences

of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Skin Cancer. 2011:8584252011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Reed KB, Brewer JD, Lohse CM, Bringe KE,

Pruitt CN and Gibson LE: Increasing incidence of melanoma among

young adults: An epidemiological study in Olmsted County,

Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 87:328–334. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bedia C, Casas J, Andrieu-Abadie N,

Fabriàs G and Levade T: Acid ceramidase expression modulates the

sensitivity of A375 melanoma cells to decarbazine. J Biol Chem.

286:28200–28209. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mouawad R, Sebert M, Michels J, Bloch J,

Spano JP and Khayat D: Treatment for metastatic malignant melanoma:

Old drugs and new strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 74:27–39.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Brennan J, Norris DP and Robertson EJ:

Nodal activity in the node governs left-right asymmetry. Genes Dev.

16:2339–2344. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Takenaga M, Fukumoto M and Hori Y:

Regulated nodal signaling promotes differentiation of the

definitive endoderm and mesoderm from ES cells. J Cell Sci.

120:2078–2090. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Topczewska JM, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV,

Sam A, Hess AR, Wheaton WW, Nickoloff BJ, Topczewski J and Hendrix

MJ: Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal

signaling: Role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nat Med. 12:925–932.

2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lee CC, Jan HJ, Lai JH, Ma HI, Hueng DY,

Lee YC, Cheng YY, Liu LW, Wei HW and Lee HM: Nodal promotes growth

and invasion in human gliomas. Oncogene. 29:3110–3123. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lawrence MG, Margaryan NV, Loessner D,

Collins A, Kerr KM, Turner M, Seftor EA, Stephens CR, Lai J; APC

BioResource, ; et al: Reactivation of embryonic nodal signaling is

associated with tumor progression and promotes the growth of

prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 71:1198–1209. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Quail DF, Zhang G, Walsh LA, Siegers GM,

Dieters-Castator DZ, Findlay SD, Broughton H, Putman DM, Hess DA

and Postovit LM: Embryonic morphogen nodal promotes breast cancer

growth and progression. PLoS One. 7:e482372012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Papageorgiou I, Nicholls PK, Wang F,

Lackmann M, Makanji Y, Salamonsen LA, Robertson DM and Harrison CA:

Expression of nodal signalling components in cycling human

endometrium and in endometrial cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.

7:1222009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lonardo E, Hermann PC, Mueller MT, Huber

S, Balic A, Miranda-Lorenzo I, Zagorac S, Alcala S,

Rodriguez-Arabaolaza I, Ramirez JC, et al: Nodal/Activin signaling

drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer stem

cells and provides a target for combined drug therapy. Cell Stem

Cell. 9:433–446. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fuerer C, Nostro MC and Constam DB:

Nodal·Gdf1 heterodimers with bound prodomains enable

serum-independent nodal signaling and endoderm differentiation. J

Biol Chem. 289:17854–17871. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ellis PS, Burbridge S, Soubes S, Ohyama K,

Ben-Haim N, Chen C, Dale K, Shen MM, Constam D and Placzek M:

ProNodal acts via FGFR3 to govern duration of Shh expression in the

prechordal mesoderm. Development. 142:3821–3832. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cabarcas SM, Mathews LA and Farrar WL: The

cancer stem cell niche-there goes the neighborhood? Int J Cancer.

129:2315–2327. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhu H, Wang D, Liu Y, Su Z, Zhang L, Chen

F, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Yu M, Zhang Z and Shao G: Role of the

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha induced autophagy in the

conversion of non-stem pancreatic cancer cells into

CD133+ pancreatic cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Cell

Int. 13:1192013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Quail DF, Taylor MJ, Walsh LA,

Dieters-Castator D, Das P, Jewer M, Zhang G and Postovit LM: Low

oxygen levels induce the expression of the embryonic morphogen

Nodal. Mol Biol Cell. 22:4809–4821. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhou S, Kurt-Jones EA, Cerny AM, Chan M,

Bronson RT and Finberg RW: MyD88 intrinsically regulates CD4 T-cell

responses. J Virol. 83:1625–1634. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

dos Santos SC, Tenreiro S, Palma M, Becker

J and Sá-Correia I: Transcriptomic profiling of the

Saccharomyces cerevisiae response to quinine reveals a

glucose limitation response attributable to drug-induced inhibition

of glucose uptake. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 53:5213–5223. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Walsh MC, Smits HP, Scholte M and van Dam

K: Affinity of glucose transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is

modulated during growth on glucose. J Bacteriol. 176:953–958. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Constam DB and Robertson EJ: Regulation of

bone morphogenetic protein activities by prodomains and proprotein

convertases. J Cell Biol. 144:139–149. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Vo BT and Khan SA: Expression of nodal and

nodal receptors in prostate stem cells and prostate cancer cells:

Autocrine effects on cell proliferation and migration. Prostate.

71:1084–1096. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lai JH, Jan HJ, Liu LW, Lee CC, Wang SG,

Hueng DY, Cheng YY, Lee HM and Ma HI: Nodal regulates energy

metabolism in glioma cells by inducing expression of

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Neuro Oncol. 15:1330–1341. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL

and Denko NC: HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively

downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab.

3:187–197. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang F, Zhang GY, Xing T, Lu ZY, Li JH,

Peng C, Liu GH and Wang NS: Renalase contributes to the renal

protection of delayed ischaemic preconditioning via the regulation

of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. J Cell Mol Med. 19:1400–1409. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jian SL, Chen WW, Su YC, Su YW, Chuang TH,

Hsu SC and Huang LR: Glycolysis regulates the expansion of

myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing hosts through

prevention of ROS-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 8:e27792017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Elliott RL and Blobe GC: Role of

transforming growth factor beta in human cancer. J Clin Oncol.

23:2078–2093. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Glasgow E and Mishra L: Transforming

growth factor-beta signaling and ubiquitinators in cancer. Endocr

Relat Cancer. 15:59–72. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Beck S, Le Good JA, Guzman M, Ben Haim N,

Roy K, Beermann F and Constam DB: Extraembryonic proteases regulate

nodal signaling during gastrulation. Nat Cell Biol. 4:981–985.

2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ben-Haim N, Lu C, Guzman-Ayala M,

Pescatore L, Mesnard D, Bischofberger M, Naef F, Robertson EJ and

Constam DB: The nodal precursor acting via activing receptors

induces mesoderm by maintaining a source of its convertases and

BMP4. Dev Cell. 11:313–323. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Eimon PM and Harland RM: Effects of

heterodimerization and proteolytic processing on derriere and nodal

activity: Implications for mesoderm induction in xenopus.

Development. 129:3089–3103. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Strizzi L, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV,

Seftor EA, Abbott DE, Seftor RE, Salomon DS and Hendrix MJ:

Emerging roles of nodal and Cripto-1: From embryogenesis to breast

cancer progression. Breast Dis. 29:91–103. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shen MM: Nodal signaling: Developmental

roles and regulation. Development. 134:1023–1034. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Duan W, Li R, Ma J, Lei J, Xu Q, Jiang Z,

Nan L, Li X, Wang Z, Huo X, et al: Overexpression of nodal induces

a metastatic phenotype in pancreatic cancer cells via the Smad2/3

pathway. Oncotarget. 6:1490–1506. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Strizzi L, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV,

Lipavsky A, Gadiot J, Blank C, Seftor RE, Seftor EA and Hendrix MJ:

Nodal as a biomarker for melanoma progression and a new therapeutic

target for clinical intervention. Expert Rev Dermatol. 4:67–78.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Seftor EA,

Kirschmann DA, Lipavsky A, Wheaton WW, Abbott DE, Seftor RE and

Hendrix MJ: Human embryonic stem cell microenvironment suppresses

the tumorigenic phenotype of aggressive cancer cells. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 105:4329–4334. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Brennan J, Lu CC, Norris DP, Rodriguez TA,

Beddington RS and Robertson EJ: Nodal signaling in the epiblast

patterns the early mouse embryo. Nature. 411:965–969. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cioffi M, Trabulo SM, Sanchez-Ripoll Y,

Miranda-Lorenzo I, Lonardo E, Dorado J, Vieira Reis C, Ramirez JC,

Hidalgo M, Aicher A, et al: The miR-17-92 cluster counteracts

quiescence and chemoresistance in a distinct subpopulation of

pancreatic cancer stem cells. Gut. 64:1936–1948. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|