Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 9th most common and the 13th

most fatal type of cancer worldwide (1). Approximately 75% of patients with

bladder cancer have non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and

~25% have muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) or metastatic

disease at the time of initial diagnosis (2,3). Different

molecular subtypes of bladder cancer have unique clinical

characteristics and therapeutic responses. For instance, patients

with ‘basal’ subtype of MIBC are known to have shorter

disease-specific survival and overall survival rate (4,5). MIBC is a

highly lethal disease and its overall five-year survival rate is

30–50%, whereas that for metastatic bladder cancer is 5% (3,6).

The tumor microenvironment (TME) consists

predominantly of tumor cells, stroma and infiltrating immune cells.

Immune cells in the TME may exert either tumor-suppressive or

tumor-promoting effects. CD8+ T cells and natural killer

cells (NKs) mediate antitumor functions, whereas tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) serves as

tumor-promoting agents (7,8). As an important component of the innate

and adaptive immunity, macrophages may polarize into different

functional phenotypes, such as the classically activated M1 and the

alternatively activated M2 macrophages, depending on the external

stimulus (9). Increasing evidence

suggests that M2 macrophages could perform immunosuppressive

functions and promote tumor progression and metastasis (7,10–12). It is therefore speculated that the M2

macrophages may have potential as immunotherapy targets (7).

Recently, immunotherapy based on immune checkpoint

inhibitors has achieved satisfactory results in the treatment of

bladder cancer. However, this outcome was limited to only a subset

of patients, since others failed to respond to this therapy

(13). Hence, it is important to

determine the essential immune components and relevant mechanisms

that affect tumor progression in order to improve the immunotherapy

of bladder cancer.

The majority of previous studies on the TME

associated with bladder cancer have mainly focused on a few types

of immune cells and were performed on small numbers of samples

(14,15). There is no large-scale data based on

big numbers of samples to identify important immune components in

bladder cancer. To the best of our knowledge, the molecular

mechanisms of immune activities in the bladder cancer

microenvironment have not been sufficiently researched.

The present study aimed to explore the predominant

tumor-infiltrating immune cell subsets in the bladder cancer

microenvironment and the signals recruiting them. Bioinformatics

methods were employed to analyze the immune infiltration profile

and revealed that M2 macrophage infiltration levels were associated

with the histologic grade, pathologic stage, and worse survival in

bladder cancer. Bladder cancer-specific genomic alterations, such

as gene mutation and copy number alterations, may be important

drivers of M2 macrophage infiltration.

Materials and methods

Gene expression datasets

The gene expression dataset (426 samples) and

microRNA (miRNA) mature strand expression dataset (429 samples),

based on RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) bladder urothelial carcinoma cohort, were downloaded from

the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) xena browser

(https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/).

The gene expression data were presented as log2(x+1)-transformed

RNA-seq by expectation maximization (RSEM)-normalized count values

derived from TCGA level 3 data, and miRNA mature strand expression

data were presented as log2(RPM+1)-transformed reads-per-million

(RPM) values derived from TCGA level 3 data. The gene expression

validation datasets were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and European

Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) ArrayExpress (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/). The expression

dataset of 224 samples in GSE32894, expression dataset of 142

samples in GSE48277, and dataset of 85 samples in E-MTAB-1803 were

analyzed to confirm the results derived from the analyses of TCGA

dataset in the present study. All expression data was provided as

normalized data, after performing log2 conversion on GSE32894 and

E-MTAB-1803 datasets.

Clinical data

Clinical data of TCGA dataset were downloaded from

the UCSC Xena browser, including histologic grade, pathologic stage

and survival information for patients with bladder cancer. The

molecular subtype information of TCGA samples was obtained from the

supplementary file of the MIBC Molecular Characterization reported

by Robertson et al (3).

Clinical data for GSE32894, GSE48277 and E-MTAB-1803 datasets were

obtained from GEO and EBI ArrayExpress. The clinical data

associated with the GSE32894 and E-MTAB-1803 datasets contained the

molecular subtype information for each sample.

Mutation and copy number alteration

data

The mutation and copy number alteration data of TCGA

samples were obtained from the supplementary file of the study

reported by Robertson et al (3). The mutation data of E-MTAB-1803 and

GSE48277 were obtained from the detailed sample information.

Data processing

Gene expression data, miRNA mature strand expression

data, clinical data, mutation and copy number alteration data were

integrated according to sample ID using Perl script. Values of

GSE48277 dataset were log2 transformed by R script. The GSE32894,

GSE48277 and E-MTAB-1803 datasets were further processed by R

script. This included matching gene symbols, probes, calculating

mean expression value for the gene symbol when several probes

corresponded to one gene symbol, and defining mean value as the

expression level of the gene symbol.

Immune infiltration analysis based on

single-sample geneset enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) scores

To investigate the immune infiltration landscape of

bladder cancer, ssGSEA was performed to assess the level of immune

infiltration (recorded as ssGSEA score) in a sample according to

the expression levels of immune cell-specific marker genes. Marker

genes for most immune cell types were obtained from the article

published by Bindea et al (16). Marker genes for M1 macrophages, M2

macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Tregs

were obtained from published studies (10,14,17–25).

The ssGSEA analysis was performed based on GenePattern environment

(26). To run ssGSEA online analysis

(https://cloud.genepattern.org), gene

expression dataset file (GCT file), immune marker gene set file

(GMT file), and other parameters were uploaded as a set. Finally,

the ssGSEA scores, representing infiltration levels of immune cells

for individual samples, were presented in the output file.

Immune infiltration analysis based on

cell type identification by estimating relative subsets of known

RNA transcripts (CIBERSORT) method

The CIBERSORT analytical tool was developed to

analyze the 22 distinct leukocyte subsets in the tumors based on

bulk transcriptome data (27).

CIBERSORT (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/) was employed to

analyze the immune landscape of bladder cancer microenvironment

based on the TCGA RNA-seq dataset. The TCGA RNA-seq dataset was

used as the gene expression input and LM22 (22 immune cell types)

was set as the signature gene file. The analysis was conducted with

1,000 permutations. The CIBERSORT values generated were defined as

immune cell infiltration fraction per sample.

RNA-seq analysis

A previous study from our group has used RNA-seq

analysis of 10 tumor samples from patients with bladder cancer to

identify novel prognostic biomarkers (28). These RNA-seq data were re-analyzed in

the present study to investigate the TME, as aforementioned.

Primary sequencing data (raw reads) were subjected to quality

control and aligned to hg19 human genome. Reads per kilobase

million (RPKM)-normalized values were computed to quantify gene

expression levels. RNA-seq analysis and data processing was

conducted by Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China).

Subsequently, the normalized data was analyzed by ssGSEA to

quantify the immune infiltration levels in the tissue samples.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) assay

Formalin-fixed (10% formalin at room temperature for

24 h), paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were collected from 48

patients with bladder cancer (including the 10 patients enrolled in

the aforementioned RNA sequencing analysis) diagnosed at Changhai

Hospital, Shanghai, China, from December 2011 to June 2017. Written

informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to surgery.

The deparaffinized sections (4 µm thickness) were incubated in

Tris/EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) for antigen retrieval. Subsequently,

blocking of endogenous peroxidase and non-specific epitopes were

performed using the UltraSensitive IHC kit (cat. no. KIT-9710;

Fuzhou Maixin Biotech. Co., Ltd.). The slides were incubated with

primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, then with biotin-conjugated

secondary antibodies at 37°C for 30 min and with

streptavidin-peroxidase at room temperature for 10 min, using the

UltraSensitive IHC kit. Immunostaining of slides was performed with

3,3′ diaminobenzidine followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin,

dehydrating, and mounting. All mounted specimens were scanned into

high resolution digital slides through slide scanners

NanoZoomer-S60 (Hamamatsu Photonics). The primary antibodies were

as follows: Monoclonal mouse anti-CD68 antibody (cat. no. M0876;

1:100 dilution; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), monoclonal

rabbit anti-CD163 antibody (cat. no. ab182422; 1:500 dilution;

Abcam) and monoclonal rabbit anti-CD31 antibody (cat. no. ab207090;

1:2,000 dilution; Abcam).

The IHC results for CD68 and CD163 were analyzed via

a combination of the scores based on the percentage of positively

stained cells (0, negative; 1, <15%; 2, 15–50%; 3, >50%) and

the scores based on the color intensity (0, negative staining; 1+,

weak staining, light yellow; 2+, moderate staining, yellow brown;

and 3+, strong staining, brown). Samples with IHC score ≤3 were

defined as low expression, while samples with IHC score >3 were

defined as high expression. Microvessels were evaluated by CD31 IHC

staining, as described previously (29). Slides were first observed at ×100

magnification to identify hotspots with the highest density of

microvessels and each hotspot was then evaluated at ×400

magnification. Any brown-staining endothelial cell or cell cluster

was considered a countable microvessel.

Statistical analysis

For ssGSEA scores, CIBERSORT values, miRNA

expression values and microvessel counts, comparison between two

groups was conducted using the Mann-Whitney test for data with

abnormal distribution and Student's t-test for data with normal

distribution. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier

curves and log-rank test. IHC results (scores) for CD68 and CD163

were analyzed by Chi-square test. Pearson correlation analysis was

used to estimate the consistency between ssGSEA scores and IHC

scores in assessing M2 macrophage infiltration, and between miRNA

expression values and ssGSEA scores of M2 macrophage. Statistical

analysis was performed using SPSS pack 13.0 statistical software

(SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad

Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Immune landscape related to

histopathologic characteristics of bladder cancer

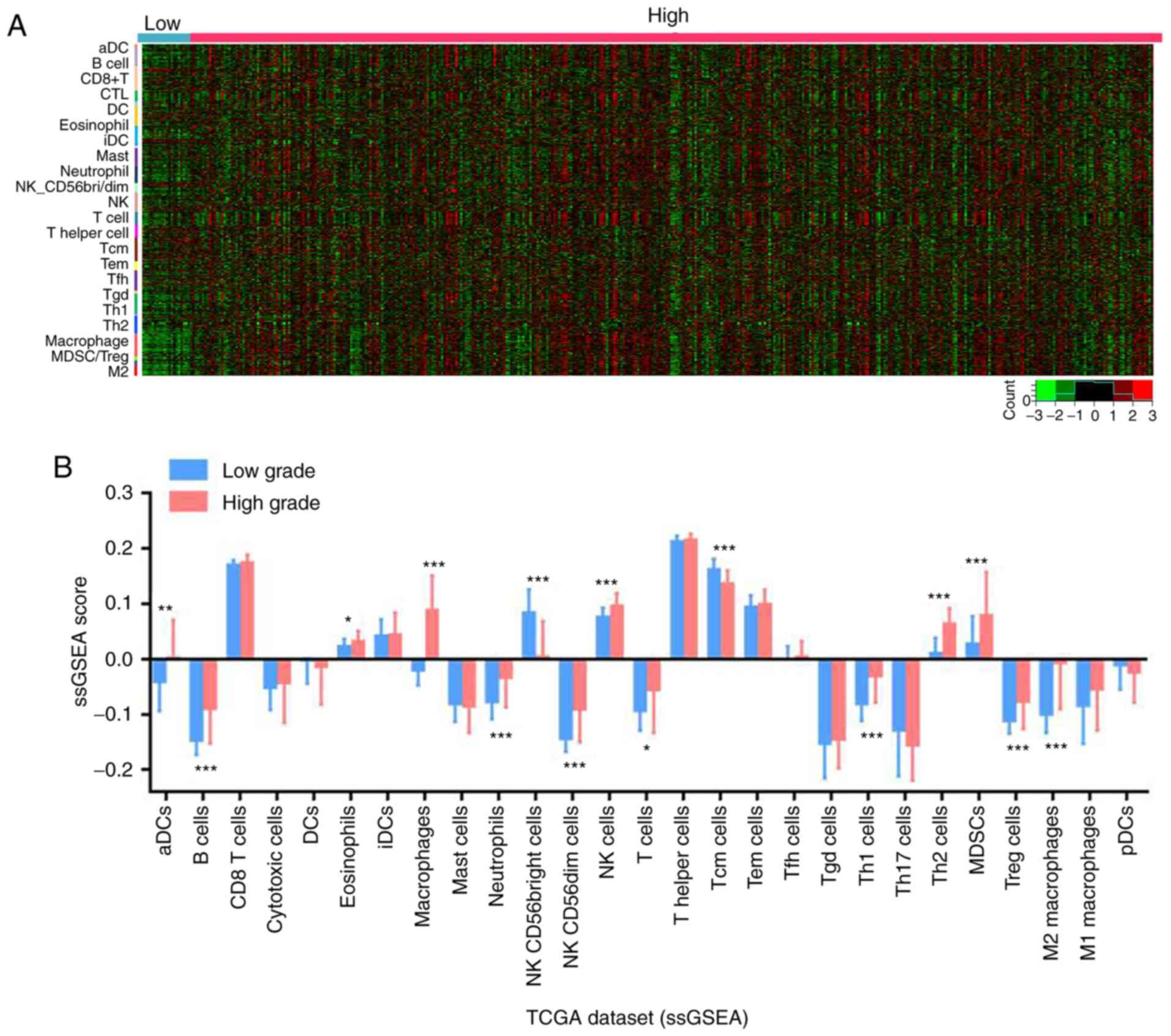

To explore the influence of immune cells on the

malignant progression of bladder cancer, first, the RNA-seq data of

426 patients with bladder cancer from TCGA database were analyzed

to evaluate the immune landscape. The marker genes of the majority

of types of immune cells were evaluated between low and high

histologic grade bladder cancer samples in TCGA dataset. The

results revealed that B cells, macrophages and M2 macrophages were

enriched in high grade bladder cancer, as presented in the

corresponding heat map in Fig. 1A.

Given that ssGSEA had previously been implemented to determine the

immune landscape in clear cell renal cell carcinoma by utilizing

RNA-seq data (7), the infiltration of

each immune cell in the bladder cancer RNA-seq data was

quantitatively analyzed using this method. The results indicated

that B cells, macrophages, neutrophils, NK CD56dim cells, NK cells,

T helper (Th) 1 cells, Th2 cells, MDSCs, Tregs and M2 macrophages

were significantly enriched in high grade compared with low grade

bladder cancer tissues (Fig. 1B).

CIBERSORT was next applied to statistically estimate the relative

proportions of immune cell subsets among different grades of

bladder cancer samples in the TCGA dataset, following the method

reported by Gentles et al (27). It was demonstrated that the

infiltration levels of macrophage subsets (M0/M1/M2) and CD4 cell

subsets (memory activated/memory resting) were higher in high grade

bladder cancer. Furthermore, M2 macrophages accounted for the

largest proportion among the 22 subsets of tumor-infiltrating

immune cells, suggesting that they may have a key role in the

progression of bladder cancer (Fig.

1C). Data from the GSE32894 dataset were used to validate the

composition and proportion of tumor-infiltrating immune cell

subsets in bladder cancer. The results were consistent with those

observed in TCGA dataset, with higher levels of macrophage and M2

macrophage infiltration in the high-grade tumors compared with the

low-grade tumors (Fig. 1D).

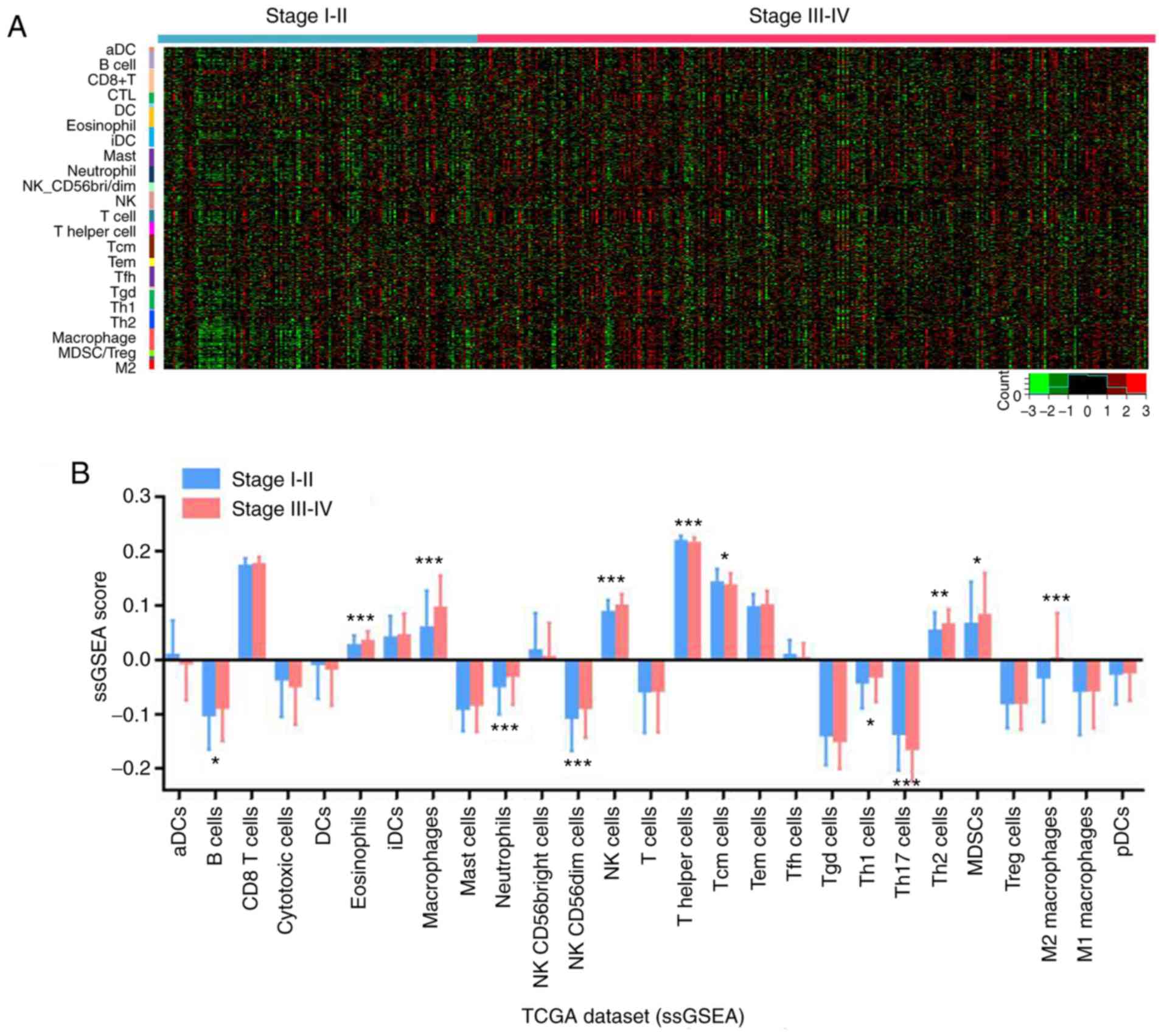

The immune cell infiltration in different pathologic

stages of bladder cancer was then explored. As presented in

Fig. 2A-C, in the TCGA dataset, B

cells, macrophages and M2 macrophages exhibited a high infiltration

level in higher compared with lower stage bladder cancer, with M2

macrophages having the highest proportion. Furthermore, the

infiltration levels of macrophages and M2 macrophages were

positively associated with the pathologic stage of bladder cancer,

as confirmed by the data analysis from the validation datasets

GSE32894 (Fig. 2D) and E-MTAB-1803

(Fig. 2E).

In summary, the present results demonstrated that

the infiltration levels or proportions of macrophages, especially

M2 macrophages, were positively associated with histologic grade

and pathologic stage of bladder cancer, suggesting that M2

macrophages may be involved in the progression of bladder

cancer.

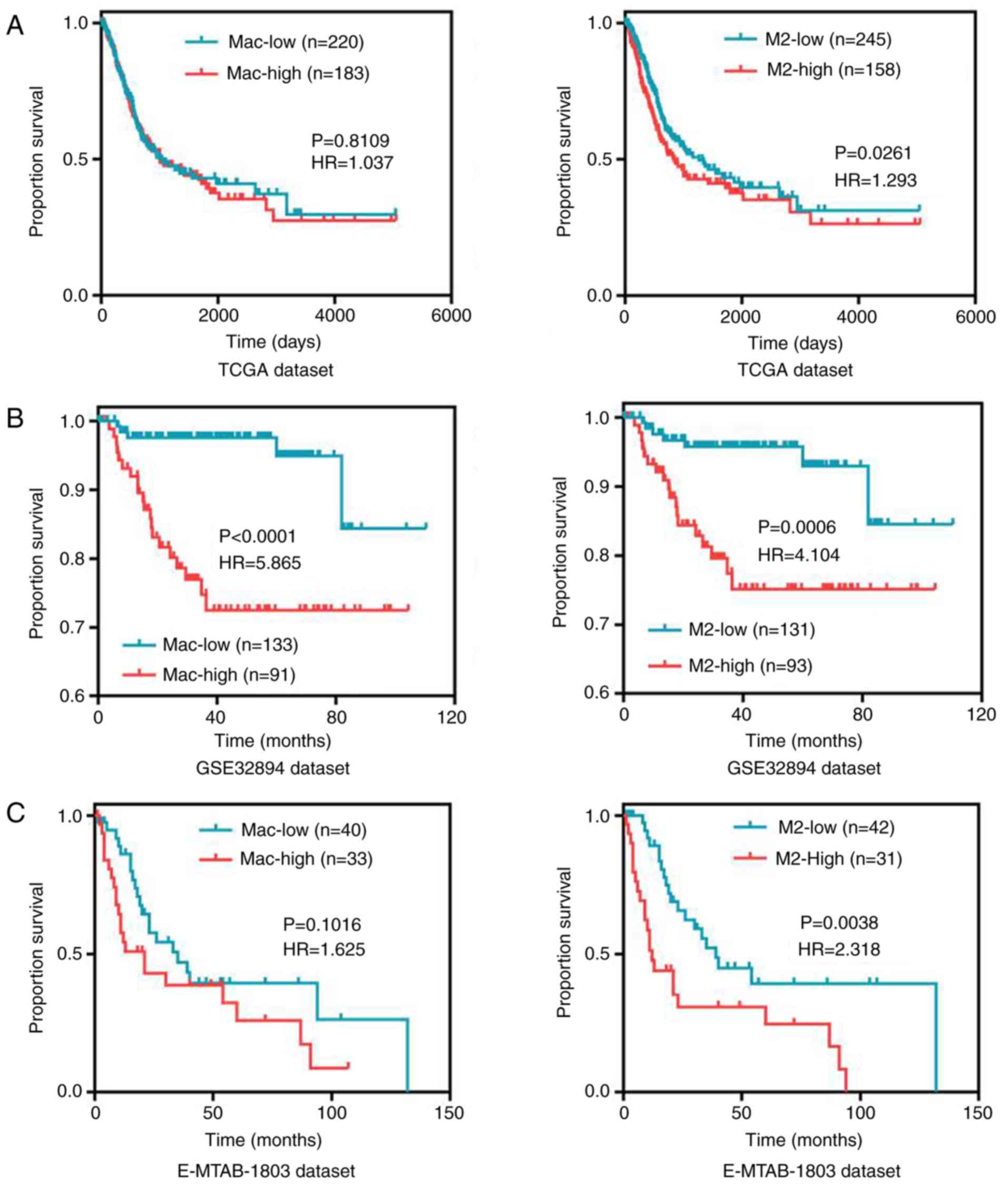

Association of M2 macrophage

infiltration with the prognosis of patients with bladder

cancer

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis and ssGSEA

scores were used to further explore the effect of M2 macrophage

infiltration on the prognosis of patients with bladder cancer. In

TCGA dataset, it was observed that patients with high infiltration

of M2 macrophages had worse overall survival compared with patients

with low infiltration (Fig. 3A). No

significant difference was observed in patient survival with

varying total macrophage infiltration (Fig. 3A). Patients in the validation dataset

GSE32894 with high macrophage and M2 macrophage infiltration

exhibited worse disease-free survival (Fig. 3B). Finally, patients in the validation

dataset E-MTAB-1803 with high M2 macrophage infiltration (but not

total macrophage infiltration) exhibited worse overall survival

(Fig. 3C). Consequently, high

infiltration of M2 macrophages was associated with poor prognosis

in patients with bladder cancer.

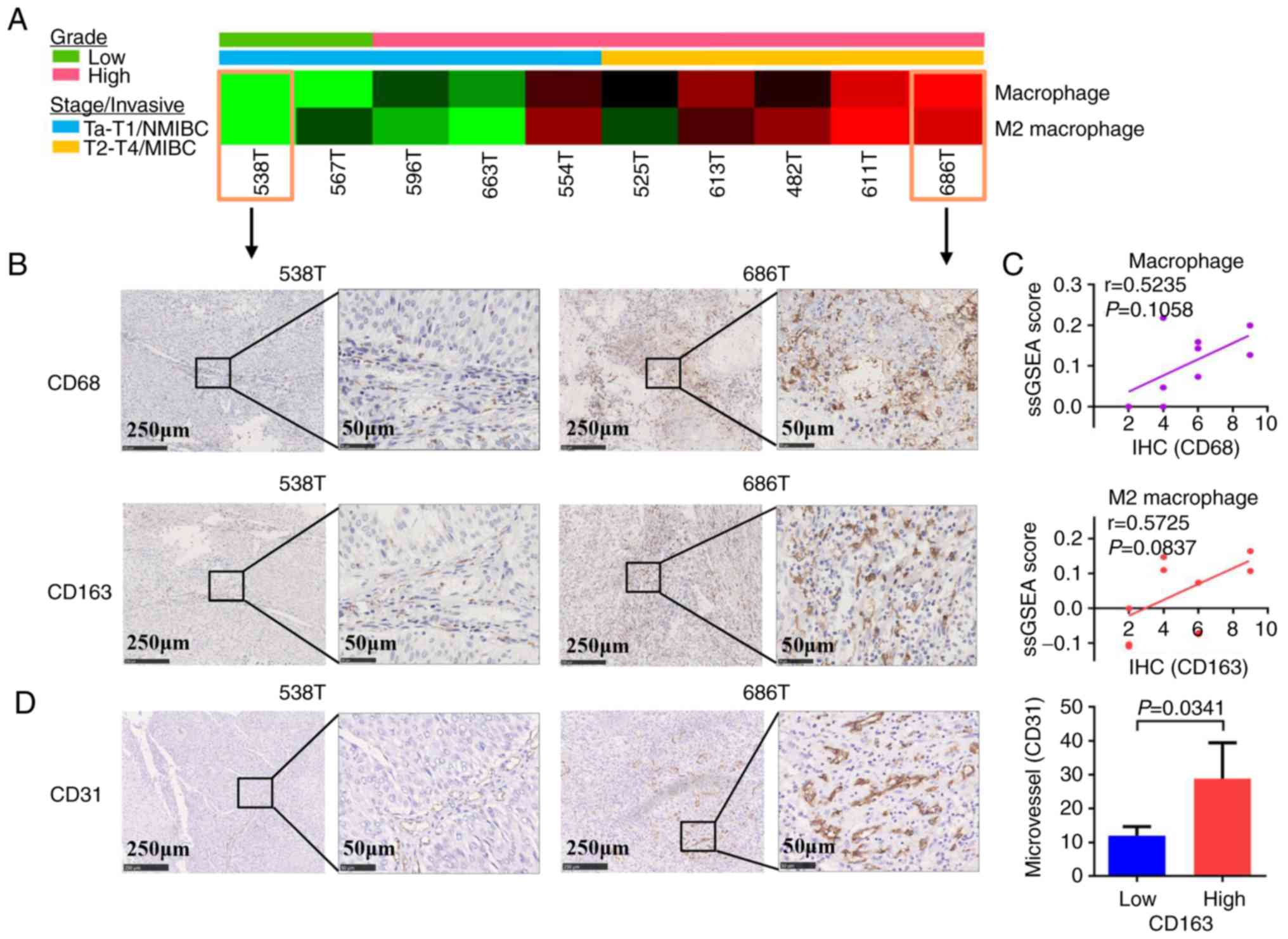

Validation of macrophage and M2

macrophage infiltration in bladder cancer

To confirm the infiltration of macrophages and M2

macrophages in tumor tissues from patients with bladder cancer in

Eastern China, the present study calculated the immune infiltration

scores for 10 newly collected tumor tissues with different

histologic grades and pathologic stages (NMIBC or MIBC) via

analyzing RNA-seq data with ssGSEA algorithm. It was demonstrated

that higher grade and stage (MIBC) bladder cancer tissues had

higher infiltration levels of macrophages and M2 macrophages,

compared with lower grade and stage (NMIBC) bladder cancer tissues

(Fig. 4A). Consequently, the

infiltration of macrophages and M2 macrophages in the 10 samples

was evaluated by IHC staining with anti-CD68 and anti-CD163

antibody, respectively. IHC scores revealed that there was high

macrophage and M2 macrophage infiltration in higher grade and stage

bladder cancer tissues (MIBC) compared with lower grade and stage

(NMIBC) bladder cancer tissues (Fig.

4B). In addition, the IHC scores were consistent with the

ssGSEA scores in the same bladder cancer patient. Pearson

correlation analysis was used to evaluate the consistency between

the IHC scores and ssGSEA scores, and the results revealed that the

two methods were positively correlated, albeit not significantly

(Fig. 4C). The reason for the lack of

statistical significance may be related to the small numbers of

samples used. Further analysis of the infiltration of macrophages

and M2 macrophages in 48 tumor tissues by IHC revealed that

macrophages and M2 macrophages were associated with the grade and

the invasiveness/stage of bladder cancer, but not with age or sex

(Table I). To investigate the

relationship between tumor-infiltrating M2 macrophages and

angiogenesis, IHC experiments were performed for the evaluation of

microvessel density via staining of CD31 in the 10 samples. The

results revealed that there were more microvessels in higher grade

and stage bladder cancer tissues and that the microvessel count was

significantly higher in the CD163-high compared with the CD163-low

tissues (Fig. 4C).

| Table I.Macrophage and M2 macrophage

infiltration in bladder cancer samples as analyzed by

immunohistochemistry staining. |

Table I.

Macrophage and M2 macrophage

infiltration in bladder cancer samples as analyzed by

immunohistochemistry staining.

|

| CD68

expression | CD163

expression |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 21 | 14 | 0.740 | 20 | 15 | 0.522 |

|

Female | 9 | 4 |

| 9 | 4 |

|

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥60 | 22 | 8 | 0.066 | 21 | 9 | 0.127 |

|

<60 | 8 | 10 |

| 8 | 10 |

|

| Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low-grade | 6 | 12 | 0.002 | 5 | 13 | 0.001 |

|

High-grade | 24 | 6 |

| 24 | 6 |

|

| Invasiveness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NMIBC | 10 | 10 | 0.019 | 9 | 11 | 0.008 |

|

MIBC | 19 | 3 |

| 19 | 3 |

|

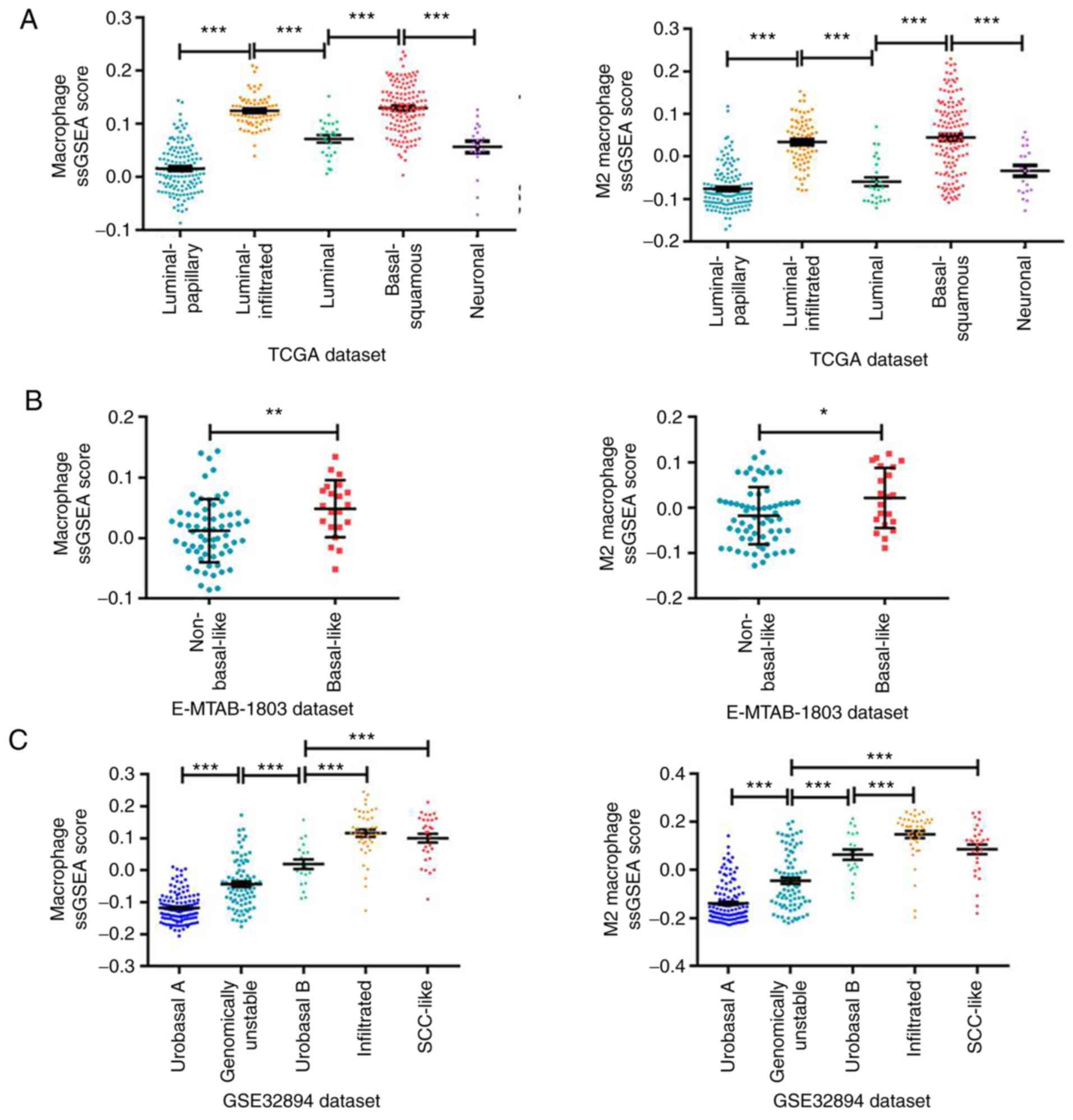

M2 macrophage infiltration varies by

molecular subtype in MIBC

Based on the high M2 macrophage infiltration in

MIBC, further investigations were conducted on whether M2

macrophage infiltration was associated with the transcriptional

molecular subtypes of MIBC. Analysis of the association of the

RNA-seq data from TCGA database with the ssGSEA scores revealed

that macrophages and M2 macrophages displayed significantly

different infiltration levels among the MIBC subtypes (Fig. 5A), with the highest infiltration

observed in the basal-squamous subtype, as defined by a previous

study using TCGA dataset (30). This

was consistent with the aforementioned results, where the

infiltration of macrophages and M2 macrophages was higher in

bladder cancer with higher grade and stage and associated with low

survival and poor prognosis of patients with basal-squamous

subtype. In addition, macrophage and M2 macrophage infiltration was

significantly higher in the basal-like subtype in the validation

dataset E-MTAB-1803 (Fig. 5B),

similar to the basal-squamous subtype in TCGA classification.

Finally, it was confirmed in the validation dataset GSE32894 that

macrophage and M2 macrophage infiltration was higher in the

infiltrated and SCC-like subtypes (5,31), which

are similar to the basal subtype. These results indicated that the

macrophage and M2 macrophage infiltration was associated with

molecular subtypes of MIBC. Additionally, M2 macrophages accounted

for the majority proportion of all subtypes of infiltrating

macrophages in bladder cancer, as presented in Figs. 1C and 2C, which indicated that the infiltration of

M2 macrophages may provide a good estimate of the overall

macrophage population in bladder cancer.

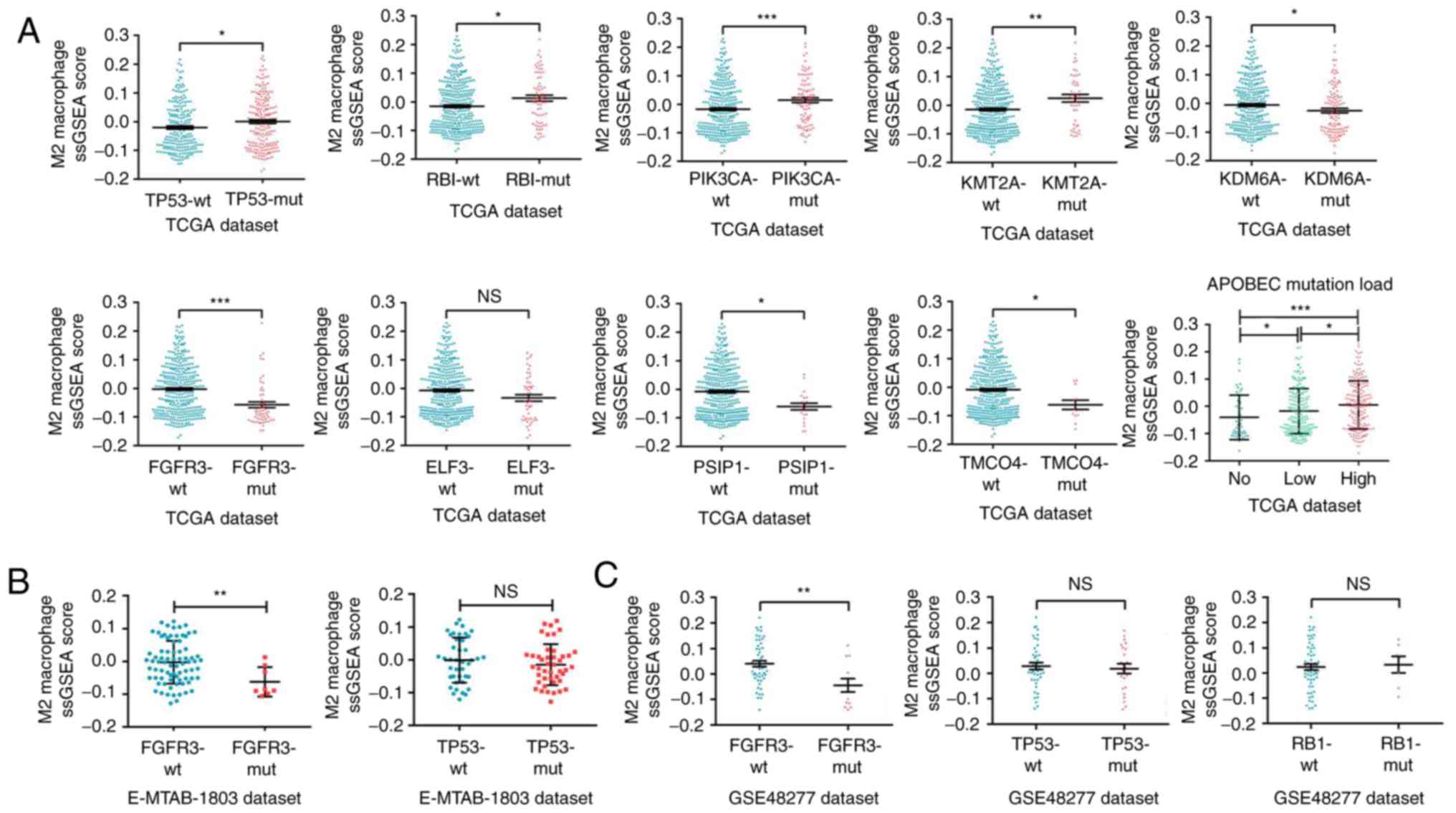

M2 macrophage infiltration is

associated with specific mutations in bladder cancer

The discovery that the infiltration of macrophages,

especially M2 macrophages, was associated with malignant

progression of bladder cancer and with the molecular subtypes of

MIBC implied that specific intrinsic genomics might affect the

infiltration of M2 macrophages. Therefore, the difference in M2

macrophage infiltration levels among different gene mutation types

was explored. Analysis of a large number of mutant genes using

ssGSEA algorithm in the TCGA dataset revealed that the M2

macrophage infiltration levels differed among multiple mutant

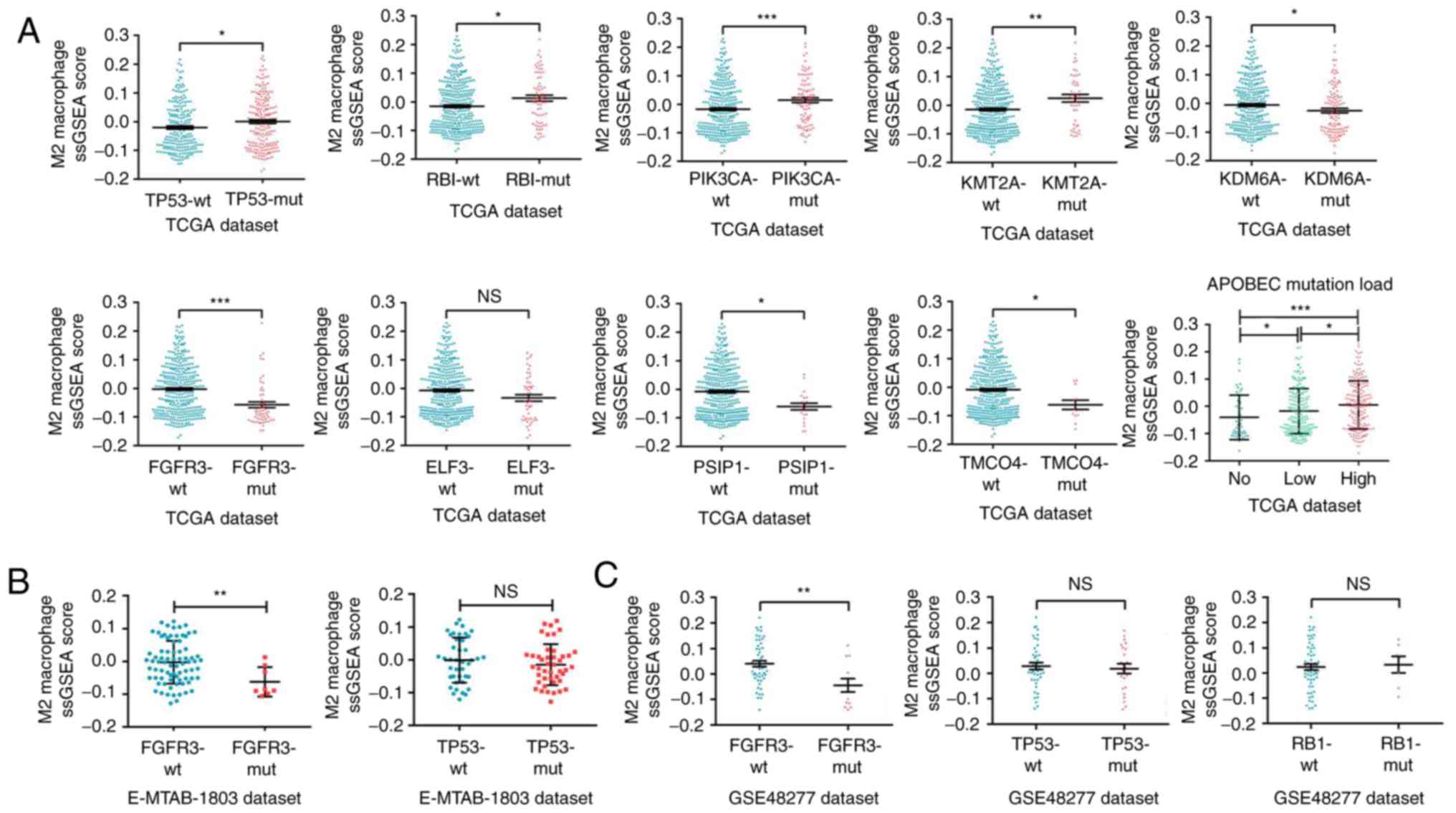

genes. As presented in Fig. 6A, the

M2 macrophage infiltration was higher in bladder tumor tissues with

mutant TP53, RB transcriptional corepressor 1 (RB1),

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α

(PIK3CA), lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A), lysine demethylase

6A (KDM6A) and apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme

catalytic-polypeptide-like (APOBEC), but lower in tissues with

mutant fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), E74-like ETS

transcription factor 3 (ELF3), PC4 and SFRS1 interacting protein 1

(PSIP1) and transmembrane and coiled-coil domains 4 (TMCO4). In the

validation datasets E-MTAB-1803 and GSE48277, it was confirmed that

M2 macrophage infiltration was lower in tissues with mutant FGFR3

(Fig. 6B and C); however, no

significant difference was observed for the mutation status of TP53

and RB1 (Fig. 6B and C). In summary,

M2 macrophage infiltration varied among bladder cancer mutant gene

types, suggesting that specific mutations may influence M2

macrophage infiltration.

| Figure 6.M2 macrophage infiltration is

associated with specific mutations in bladder cancer. (A) Analyses

of M2 macrophage infiltration profiles in bladder cancer samples

with various mutant statuses from TCGA dataset. (B) Validation

analyses of M2 macrophage infiltration profiles in samples with

FCFR3 and TP53 mutant statuses from the E-MTAB-1803 and (C)

GSE48277 datasets. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, with

comparisons indicated by brackets. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

RB1, RB transcriptional corepressor 1; PIK3CA,

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α;

KMT2A, lysine methyltransferase 2A; KDM6A, lysine demethylase 6A;

FGFR3, growth factor receptor 3; ELF3, E74-like ETS transcription

factor 3; PSIP, PC4 and SFRS1 interacting protein 1; TMCO4,

transmembrane and coiled-coil domains 4; APOBEC, apolipoprotein B

mRNA editing enzyme catalytic-polypeptide-like; ns, not

significant. |

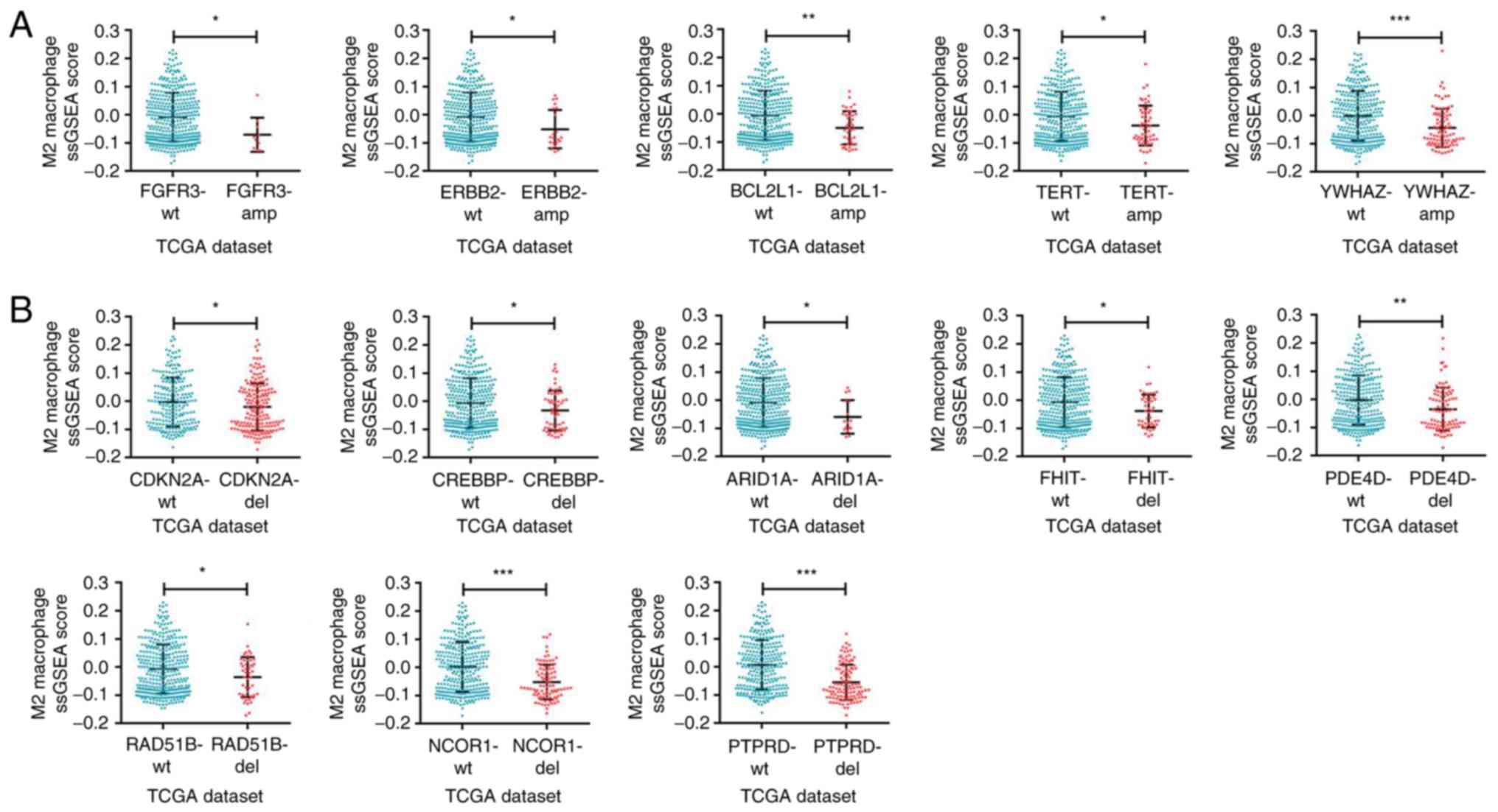

M2 macrophage infiltration is

correlated with specific copy number variations in bladder

cancer

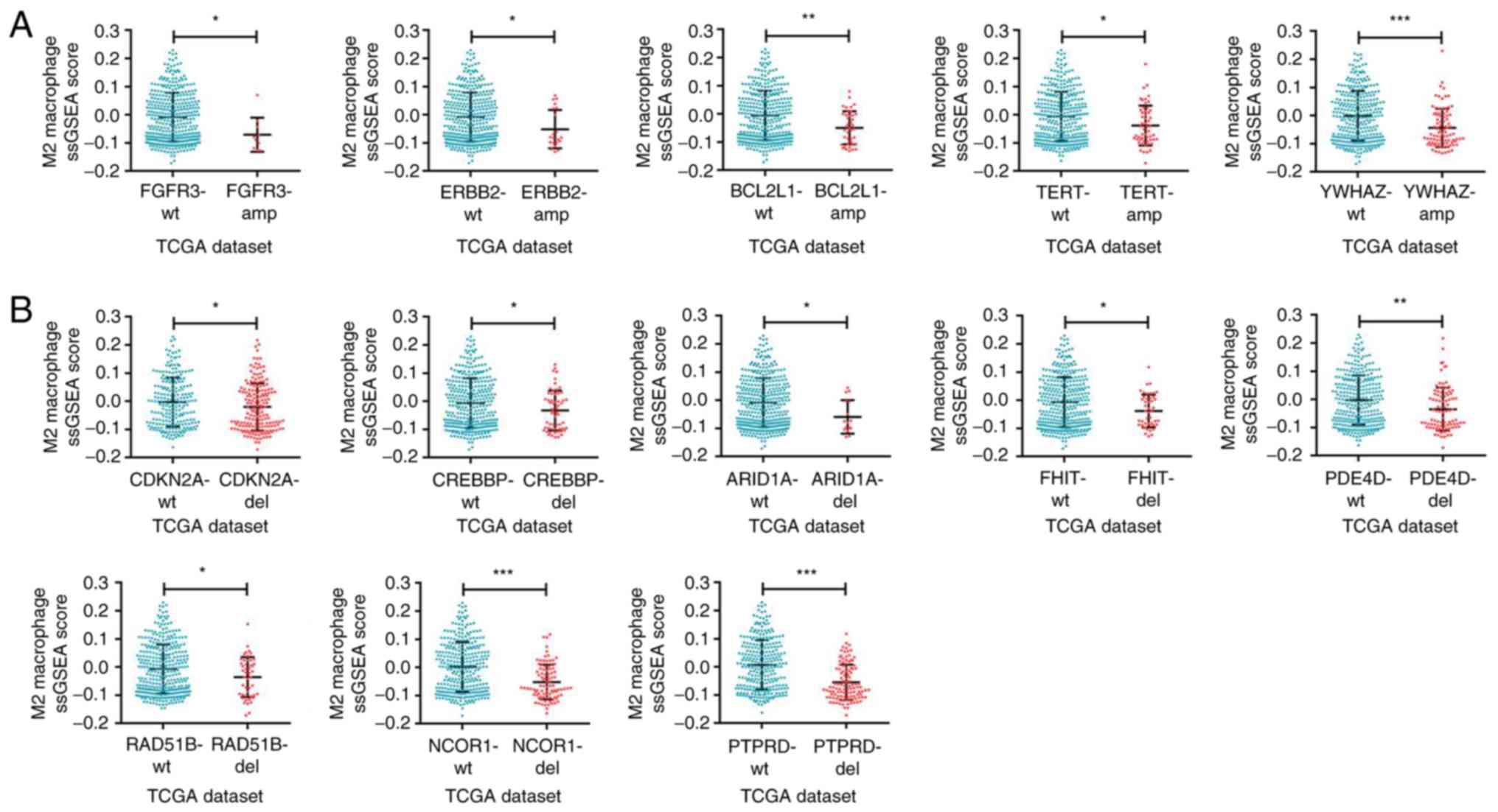

Further exploration was performed on whether there

were differences in the M2 macrophage infiltration among different

bladder cancer-specific copy number variations. It was demonstrated

that the M2 macrophage infiltration was influenced by specific

amplification types of copy number variations. The results of the

ssGSEA algorithm in TCGA dataset indicated that the infiltration in

the tissues with amplified FGFR3, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

(ERBB2), BCL2-like 1 (BCL2L1), telomerase reverse transcriptase

(TERT) and tyrosine-3-monooxygenase/tryptophan-5-monooxygenase

activation protein ζ (YWHAZ) and with deleted cyclin-dependent

kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), CREB binding protein (CREBBP),

AT-rich interaction domain 1A (ARID1A), fragile histidine triad

diadenosine triphosphatase (FHIT), phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D),

RAD51 paralog B (RAD51B), nuclear receptor corepressor 1 (NCOR1)

and protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D (PTPRD) was

significantly reduced (Fig. 7A and B,

respectively). Thus, the intrinsic specific copy number variations

of bladder cancer and related molecular mechanisms may influence

the M2 macrophage infiltration in the TME of bladder cancer.

| Figure 7.M2 macrophage infiltration is

associated with specific copy number alterations in bladder cancer.

(A) Analyses of M2 macrophage infiltration profiles in bladder

cancer samples with specific amplification of gene copy number from

TCGA dataset. (B) M2 macrophage infiltration profiles in bladder

cancer samples with specific deletion of gene copy number from TCGA

dataset. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, with

comparisons indicated by brackets. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

FGFR3, growth factor receptor 3; ERBB2, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine

kinase 2; BCL2L1, BCL2-like 1; TERT, telomerase reverse

transcriptase; YWHAZ,

tyrosine-3-monooxygenase/tryptophan-5-monooxygenase activation

protein ζ; CDKN2A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; CREBBP,

CREB binding protein; ARID1A, AT-rich interaction domain 1A; FHIT,

fragile histidine triad diadenosine triphosphatase; PDE4D,

phosphodiesterase 4D; RAD51B, RAD51 paralog B; NCOR1, nuclear

receptor corepressor 1; PTPRD, protein tyrosine phosphatase

receptor type D. |

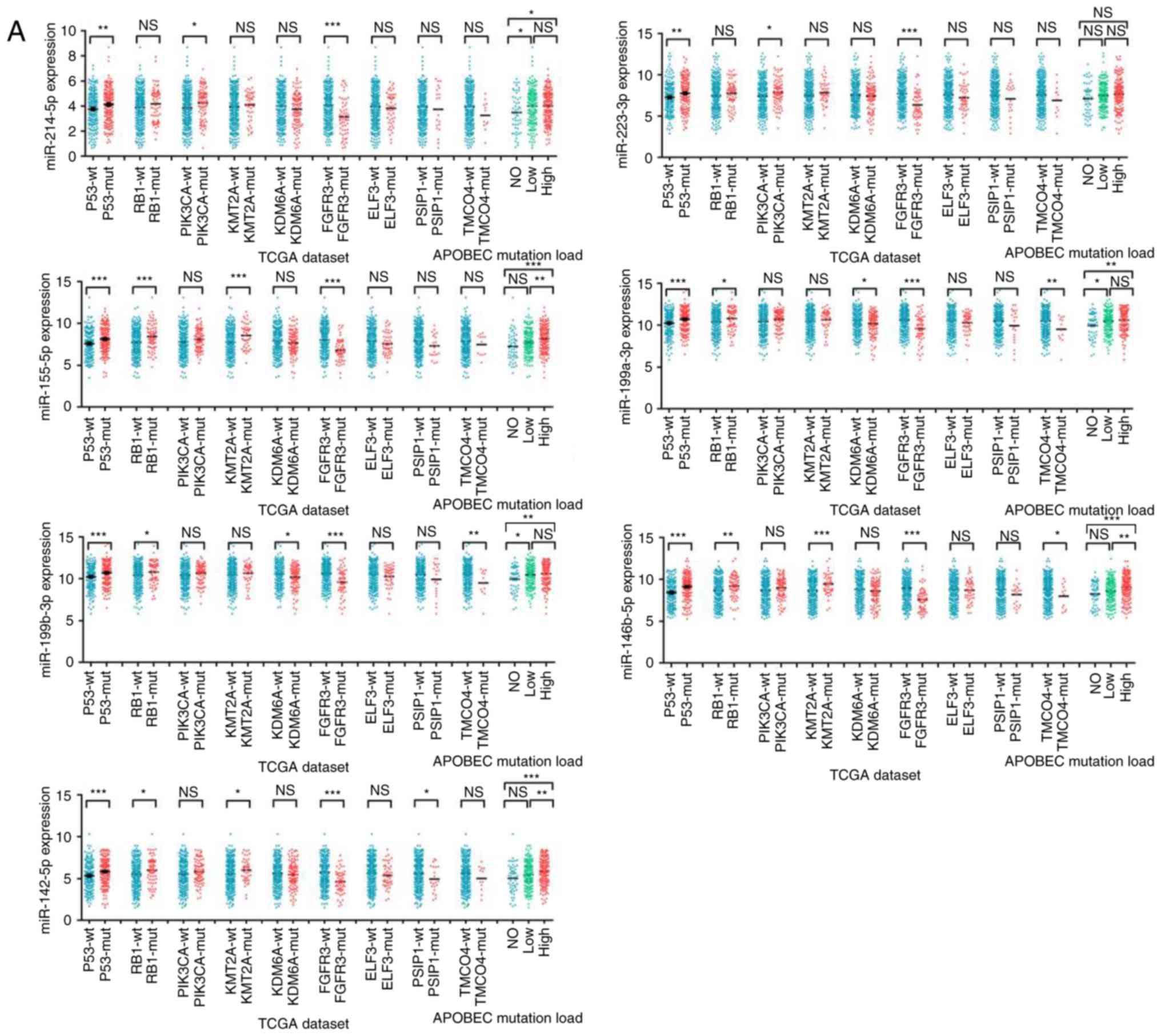

M2 macrophage infiltration is

associated with differentially expressed miRNAs in bladder

cancer

To further investigate the mechanisms of modulating

the tumor-infiltrating M2 macrophages in bladder cancer, miRNA

expression data were analyzed between tissues containing wild type

and mutant TP53, RB1, PIK3CA, KMT2A, KDM6A, FGFR3, ELF3, PSIP1,

TMCO4, and APOBEC. There was not a specific miRNA consistently

expressed differentially in all of the mutant genes. Since the

PIK3CA mutation has been previously reported to be associated with

macrophage infiltration (32), miRNAs

expressed differentially (P<0.1) between wild type and mutant

type of PIK3CA were selected. The differential expression of these

miRNAs in the remaining mutant genes were analyzed in sequence.

Seven miRNAs (miR-214-5p, miR-223-3p, miR-155-5p, miR-199a-3p,

miR-199b-3P, miR-146b-5p, miR-142-5p), which were expressed

differentially in at least three mutant genes and positively

correlated with M2 macrophage infiltration, as well as expressed

highly in high grade bladder cancer, were finally identified

(Fig. 8A-C). The differential

expression of these miRNAs in each copy number variant subtype and

stage of bladder cancer was further analyzed (Fig. S1).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that M2 macrophages

were the predominant tumor-infiltrating immune cells in the bladder

cancer microenvironment, most abundant in the ‘basal’ subtype of

MIBC and associated with the histopathologic grade and stage, as

well as the prognosis of patients. Furthermore, miRNAs expressed

differentially due to cancer-specific genomic alterations were

identified as potential triggers of M2 macrophage recruitment in

the TME of bladder cancer.

Previous studies on the immune microenvironment of

bladder cancer focused on a few selected immune cells, such as

tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells (TIDCs), tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes (TILs), and TAMs (detected by immunohistochemical

staining for CD68), and mostly involving a small number of samples

(14,33–35). In

the present study, ssGSEA and CIBERSORT algorithms were employed to

explore the infiltration of various immune cells in a large-scale

data and the results revealed that M2 macrophages were the main

immune components in bladder cancer and were associated with the

progression of tumors and the poor prognosis of patients.

Numerous studies have investigated the bladder

cancer-associated macrophages, focusing on the role of macrophages

in the treatment of bladder cancer with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

(BCG), neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunological checkpoint

inhibitors (15,35–37).

However, few studies have focused on M2 macrophages. In the present

study, high-throughput data obtained from multiple datasets were

used to demonstrate the importance of M2 macrophages in bladder

cancer progression.

Sjödahl et al (14) observed that a high CD68/CD3 ratio

reflected a poor prognosis among MIBC. Recently, Wu et al

(38) performed a meta-analysis and

demonstrated that TAMs identified with CD68 alone were not

significantly correlated with the prognosis of bladder cancer

patients, but TAMs detected with CD163 were significantly

correlated with poor relapse-free survival. Maniecki et al

(39) reported that CD163 mRNA

expression in bladder cancer biopsies was associated with advanced

tumor stages, aggressive tumor grade and poor overall survival. In

addition, high tumor macrophage infiltration (by CD163-positive

staining in IHC) was associated with advanced stage and tumor grade

(39). Aljabery et al

(40) assessed bladder cancer samples

from cystectomy by IHC and observed that M2 infiltration was not

correlated to stage or grade, but appeared to be inversely

correlated with improved cancer-specific survival; however,

patients collected in their study were all MIBC and patients with

NMIBC, which account for ~75% of all bladder cancer, were not

included. In the present study, NMIBC and MIBC samples were

included and analyzed, and M2 macrophages were demonstrated to be

associated with histologic grade and pathologic stage of bladder

cancer, as well as prognosis of patients with bladder cancer, based

on large-scale data bioinformatics analysis and biological

experimental analyses (IHC for CD163). These results suggested that

M2 macrophages may be potential targets for immunotherapy of

bladder cancer. The increased infiltration of TAMs (M2-like) is

associated with a poor response to BCG in patients with NMIBC

(35). The stromal immunotypes could

effectively predict response to adjuvant chemotherapy, recurrence

and survival in patients with MIBC (41). Nowadays, several approaches (including

depletion of TAMs, inhibition of monocyte recruitment into the

cancer, blockade of M2 macrophages, reprogramming of TAMs toward M1

macrophages) have been evaluated as strategies to target TAMs in

cancer (42). Novel immunotherapies

targeting M2 macrophages or their combination with immune

checkpoint inhibitors may present promising results in the

treatment of bladder cancer and other types of cancer (43,44).

In the present study, it was observed that

microvessel count was significantly higher in bladder cancer

tissues with highly infiltrated M2 macrophages, which indicated

that M2 macrophages may stimulate angiogenesis (45). In addition, there were more

microvessels in higher grade and stage bladder cancer tissues,

which was consistent with the hypothesis that M2 macrophages

promote neovascularization and cancer progression (46).

Tumor intrinsic genomics were found to affect the

composition of the immune microenvironment. Molecular subtypes of

glioblastoma differentially activate the immune microenvironment

and the tumor-promoting M2 macrophages exhibit a high association

with the mesenchymal subtype relative to proneural and classical

subtypes (47). It has also been

reported that TILs are associated with neurofibromin 1 and RB1

mutations, as well as epidermal growth factor receptor-amplified

and homozygous PTEN-deleted alterations in glioblastomas (48). In the present study, the levels of M2

macrophage infiltration varied among different bladder cancer

molecular subtypes, with the ‘basal’ subtype of MIBC having the

highest infiltration levels. Several gene mutations and copy number

variations were associated in the current study with M2 macrophage

infiltration in bladder cancer. Bladder cancer cells can produce

factors, such as macrophage-colony stimulating factor or monocyte

chemoattractant protein family-1, that trigger the amplification

and mobilization of macrophages in the TME (49–51).

Bladder cancer also affects macrophages by releasing and delivering

miRNAs, which may impede the M1 phenotype polarization, drive M2

phenotype polarization of macrophages, or switch phenotypes from M1

to M2 by binding to downstream targets or macrophages (9,52,53). The current results demonstrated that

there were miRNAs expressed differentially in cancer-specific

genomic alterations, related with M2 macrophage infiltration, and

highly expressed in high grade and advanced stage of bladder

cancer. Taken together, these results indicated that the bladder

cancer-specific genomic alterations may lead to differentially

expressed miRNAs, that may subsequently influence M2 macrophage

infiltration and promote bladder cancer progression. It has been

suggested that exosomes mediate the communication between tumor

cells and macrophages (54,55). Exosomes are a type of nanometric

membrane vesicles released by cells into the extracellular

environment, that regulate the biological activities of target

cells via delivering DNAs, RNAs and proteins (56). Consequently, it can be speculated that

bladder cancer with special genomic alterations may promote the

recruitment and polarization of M2 macrophages in the TME via

exosomal miRNAs. Future studies are required to validate this

hypothesis and to explore the intrinsic genomic mechanisms

affecting M2 macrophage infiltration, with the aim to provide a

potential therapeutic target of immunotherapy for bladder

cancer.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

M2 macrophages were the predominant tumor-infiltrating immune cells

in bladder cancer. Their infiltration was associated with the

histologic grade, pathologic stage of bladder cancer and ‘basal’

subtype of MIBC, as well as prognosis of patients. Differentially

expressed miRNAs, associated with cancer-specific genomic

alterations, may be important drivers of M2 macrophage

infiltration, which may serve as a potential immunotherapy target

for bladder cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Fund of China (grant no. 8150101083, 81572509), the

Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission

(grant no. 2017-01-07-00-07-E00014), the Leading Talents Training

Program of Shanghai in 2017.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YX and LT conceived the study, performed the

experiment, and wrote the manuscript. FL collected the clinical

samples and data and participated in the analysis. AL, SZ, XH and

QX participated in the experiments. LT and ZY analyzed the data. CX

and YS contributed to the initial design of the study, supervised

the bioinformatic and experimental analyses, and critically edited

the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study's protocol involving human

subjects was approved by the Ethics Committee of Changhai Hospital

of the Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China).

Written informed consent for using tumor tissue in scientific

research was obtained from all patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

NMIBC

|

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

|

|

MIBC

|

muscle invasive bladder cancer

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

NKs

|

natural killer cells

|

|

TAMs

|

tumor-associated macrophages

|

|

Tregs

|

regulatory T cells

|

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

EBI

|

European Bioinformatics Institute

|

|

ssGSEA

|

single-sample geneset enrichment

analysis

|

|

CIBERSORT

|

Cell Type Identification By Estimating

Relative Subsets Of known RNA Transcripts

|

|

RNA-seq

|

RNA sequencing

|

|

TIDCs

|

tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells

|

|

TILs

|

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

|

References

|

1

|

Sanli O, Dobruch J, Knowles MA, Burger M,

Alemozaffar M, Nielsen ME and Lotan Y: Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis

Primers. 3:170222017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M, Capoun O,

Cohen D, Compérat EM, Hernández V, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Rouprêt M,

et al: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma

of the bladder: Update 2016. Eur Urol. 71:447–461. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H,

Bellmunt J, Guo G, Cherniack AD, Hinoue T, Laird PW, Hoadley KA,

Akbani R, et al: Comprehensive molecular characterization of

muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell. 171:540–556.e25. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sjödahl G, Lauss M, Lövgren K, Chebil G,

Gudjonsson S, Veerla S, Patschan O, Aine M, Fernö M, Ringnér M, et

al: A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res.

18:3377–3386. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Choi W, Porten S, Kim S, Willis D, Plimack

ER, Hoffman-Censits J, Roth B, Cheng T, Tran M, Lee IL, et al:

Identification of distinct basal and luminal subtypes of

muscle-invasive bladder cancer with different sensitivities to

frontline chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 25:152–165. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang H, Ye YL, Li MX, Ye SB, Huang WR,

Cai TT, He J, Peng JY, Duan TH, Cui J, et al: CXCL2/MIF-CXCR2

signaling promotes the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor

cells and is correlated with prognosis in bladder cancer. Oncogene.

36:2095–2104. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kitamura T, Qian BZ and Pollard JW: Immune

cell promotion of metastasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 15:73–86. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Şenbabaoğlu Y, Gejman RS, Winer AG, Liu M,

Van Allen EM, de Velasco G, Miao D, Ostrovnaya I, Drill E, Luna A,

et al: Tumor immune microenvironment characterization in clear cell

renal cell carcinoma identifies prognostic and

immunotherapeutically relevant messenger RNA signatures. Genome

Biol. 17:2312016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang N, Liang H and Zen K: Molecular

mechanisms that influence the macrophage m1-m2 polarization

balance. Front Immunol. 5:6142014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Qian BZ and Pollard JW: Macrophage

diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell.

141:39–51. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Na YR, Yoon YN, Son DI and Seok SH:

Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition blocks M2 macrophage differentiation

and suppresses metastasis in murine breast cancer model. PLoS One.

8:e634512013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ruffell B and Coussens LM: Macrophages and

therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell. 27:462–472. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Korpal M, Puyang X, Jeremy Wu Z, Seiler R,

Furman C, Oo HZ, Seiler M, Irwin S, Subramanian V, Julie Joshi J,

et al: Evasion of immunosurveillance by genomic alterations of

PPARγ/RXRα in bladder cancer. Nat Commun. 8:1032017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sjödahl G, Lövgren K, Lauss M, Chebil G,

Patschan O, Gudjonsson S, Månsson W, Fernö M, Leandersson K,

Lindgren D, et al: Infiltration of CD3+ and

CD68+ cells in bladder cancer is subtype specific and

affects the outcome of patients with muscle-invasive tumors. Urol

Oncol. 32:791–797. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Miyake M, Tatsumi Y, Gotoh D, Ohnishi S,

Owari T, Iida K, Ohnishi K, Hori S, Morizawa Y, Itami Y, et al:

Regulatory T cells and tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor

microenvironment in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer treated with

intravesical Bacille Calmette-Guérin: A long-term follow-up study

of a Japanese Cohort. Int J Mol Sci. 18(pii): E21862017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M,

Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, Angell H, Fredriksen T,

Lafontaine L, Berger A, et al: Spatiotemporal dynamics of

intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human

cancer. Immunity. 39:782–795. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sanyal R, Polyak MJ, Zuccolo J, Puri M,

Deng L, Roberts L, Zuba A, Storek J, Luider JM, Sundberg EM, et al:

MS4A4A: A novel cell surface marker for M2 macrophages and plasma

cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 95:611–619. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ambarus CA, Krausz S, van Eijk M, Hamann

J, Radstake TR, Reedquist KA, Tak PP and Baeten DL: Systematic

validation of specific phenotypic markers for in vitro polarized

human macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 375:196–206. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lugo-Villarino G, Troegeler A, Balboa L,

Lastrucci C, Duval C, Mercier I, Bénard A, Capilla F, Al Saati T,

Poincloux R, et al: The C-type lectin receptor DC-SIGN has an

anti-inflammatory role in human M(IL-4) macrophages in response to

Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Immunol. 9:11232018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Choi JW, Kwon MJ, Kim IH, Kim YM, Lee MK

and Nam TJ: Pyropia yezoensis glycoprotein promotes the M1 to M2

macrophage phenotypic switch via the STAT3 and STAT6 transcription

factors. Int J Mol Med. 38:666–674. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu M, Yang W, Liu S, Hock D, Zhang B, Huo

RY, Tong X and Yan H: LXRα is expressed at higher levels in healthy

people compared to atherosclerosis patients and its over-expression

polarizes macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory MΦ2 phenotype.

Clin Exp Hypertens. 40:213–217. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lo TH, Silveira PA, Fromm PD, Verma ND, Vu

PA, Kupresanin F, Adam R, Kato M, Cogger VC, Clark GJ and Hart DN:

Characterization of the expression and function of the C-type

lectin receptor CD302 in mice and humans reveals a role in

dendritic cell migration. J Immunol. 197:885–898. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bellora F, Castriconi R, Dondero A,

Reggiardo G, Moretta L, Mantovani A, Moretta A and Bottino C: The

interaction of human natural killer cells with either unpolarized

or polarized macrophages results in different functional outcomes.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:21659–21664. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ornstein MC, Diaz-Montero CM, Rayman P,

Elson P, Haywood S, Finke JH, Kim JS, Pavicic PG Jr, Lamenza M,

Devonshire S, et al: Myeloid-derived suppressors cells (MDSC)

correlate with clinicopathologic factors and pathologic complete

response (pCR) in patients with urothelial carcinoma (UC)

undergoing cystectomy. Urol Oncol. 36:405–412. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gielen PR, Schulte BM, Kers-Rebel ED,

Verrijp K, Petersen-Baltussen HM, ter Laan M, Wesseling P and Adema

GJ: Increase in both CD14-positive and CD15-positive

myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations in the blood of

patients with glioma but predominance of CD15-positive

myeloid-derived suppressor cells in glioma tissue. J Neuropathol

Exp Neurol. 74:390–400. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Reich M, Liefeld T, Gould J, Lerner J,

Tamayo P and Mesirov JP: GenePattern 2.0. Nat Genet. 38:500–501.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV,

Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, et al: The

prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across

human cancers. Nat Med. 21:938–945. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zeng S, Yu X, Ma C, Song R, Zhang Z, Zi X,

Chen X, Wang Y, Yu Y, Zhao J, et al: Transcriptome sequencing

identifies ANLN as a promising prognostic biomarker in bladder

urothelial carcinoma. Sci Rep. 7:31512017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chai CY, Chen WT, Hung WC, Kang WY, Huang

YC, Su YC and Yang CH: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression

correlates with focal macrophage infiltration, angiogenesis and

unfavourable prognosis in urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Pathol.

61:658–664. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder

carcinoma. Nature. 507:315–322. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn

M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA,

et al: Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature.

406:747–752. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

An Y, Adams JR, Hollern DP, Zhao A, Chang

SG, Gams MS, Chung PED, He X, Jangra R, Shah JS, et al: Cdh1 and

Pik3ca mutations cooperate to induce immune-related invasive

lobular carcinoma of the breast. Cell Rep. 25:702–714.e6. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hanada T, Nakagawa M, Emoto A, Nomura T,

Nasu N and Nomura Y: Prognostic value of tumor-associated

macrophage count in human bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 7:263–269.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ayari C, LaRue H, Hovington H, Decobert M,

Harel F, Bergeron A, Têtu B, Lacombe L and Fradet Y: Bladder tumor

infiltrating mature dendritic cells and macrophages as predictors

of response to bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy. Eur Urol.

55:1386–1395. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Takayama H, Nishimura K, Tsujimura A,

Nakai Y, Nakayama M, Aozasa K, Okuyama A and Nonomura N: Increased

infiltration of tumor associated macrophages is associated with

poor prognosis of bladder carcinoma in situ after intravesical

bacillus Calmette-Guerin instillation. J Urol. 181:1894–1900. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tervahartiala M, Taimen P, Mirtti T,

Koskinen I, Ecke T, Jalkanen S and Boström PJ: Immunological tumor

status may predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and outcome

after radical cystectomy in bladder cancer. Sci Rep. 7:126822017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang X, Ni S, Chen Q, Ma L, Jiao Z, Wang C

and Jia G: Bladder cancer cells induce immunosuppression of T cells

by supporting PD-L1 expression in tumour macrophages partially

through interleukin 10. Cell Biol Int. 41:177–186. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wu SQ, Xu R, Li XF, Zhao XK and Qian BZ:

Prognostic roles of tumor associated macrophages in bladder cancer:

A system review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 9:25294–25303. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Maniecki MB, Etzerodt A, Ulhøi BP,

Steiniche T, Borre M, Dyrskjøt L, Orntoft TF, Moestrup SK and

Møller HJ: Tumor-promoting macrophages induce the expression of the

macrophage-specific receptor CD163 in malignant cells. Int J

Cancer. 131:2320–2331. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Aljabery F, Olsson H, Gimm O, Jahnson S

and Shabo I: M2-macrophage infiltration and macrophage traits of

tumor cells in urinary bladder cancer. Urol Oncol.

36:159.e19–159.e26. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Fu H, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Liu Z, Zhang J, Xie

H, Fu Q, Dai B, Ye D and Xu J: Identification and validation of

stromal immunotype predict survival and benefit from adjuvant

chemotherapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 24:3069–3078. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Rubio C, Munera-Maravilla E, Lodewijk I,

Suarez-Cabrera C, Karaivanova V, Ruiz-Palomares R, Paramio JM and

Dueñas M: Macrophage polarization as a novel weapon in conditioning

tumor microenvironment for bladder cancer: Can we turn demons into

gods? Clin Transl Oncol. 21:391–403. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Pyonteck SM, Akkari L, Schuhmacher AJ,

Bowman RL, Sevenich L, Quail DF, Olson OC, Quick ML, Huse JT,

Teijeiro V, et al: CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization

and blocks glioma progression. Nat Med. 19:1264–1272. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhu Y, Knolhoff BL, Meyer MA, Nywening TM,

West BL, Luo J, Wang-Gillam A, Goedegebuure SP, Linehan DC and

DeNardo DG: CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating

macrophages and improves response to T-cell checkpoint

immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res.

74:5057–5069. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sica A and Mantovani A: Macrophage

plasticity and polarization: In vivo veritas. J Clin Invest.

122:787–795. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bronte V and Murray PJ: Understanding

local macrophage phenotypes in disease: Modulating macrophage

function to treat cancer. Nat Med. 21:117–119. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, Kim H, Squatrito M,

Scarpace L, deCarvalho AC, Lyu S, Li P, Li Y, et al: Tumor

evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates

with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell.

32:42–56.e6. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Rutledge WC, Kong J, Gao J, Gutman DA,

Cooper LA, Appin C, Park Y, Scarpace L, Mikkelsen T, Cohen ML, et

al: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in glioblastoma are associated

with specific genomic alterations and related to transcriptional

class. Clin Cancer Res. 19:4951–4960. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG and Pollard

JW: Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary

tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 193:727–740. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang

J, Campion LR, Kaiser EA, Snyder LA and Pollard JW: CCL2 recruits

inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis.

Nature. 475:222–225. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A,

Ryan R, Pucci F, Sio SW, Kuswanto W, Rauch PJ, Chudnovskiy A,

Iwamoto Y, et al: Angiotensin II drives the production of

tumor-promoting macrophages. Immunity. 38:296–308. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ying W, Tseng A, Chang RC, Morin A, Brehm

T, Triff K, Nair V, Zhuang G, Song H, Kanameni S, et al:

MicroRNA-223 is a crucial mediator of PPARγ-regulated alternative

macrophage activation. J Clin Invest. 125:4149–4159. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

He X, Tang R, Sun Y, Wang YG, Zhen KY,

Zhang DM and Pan WQ: MicroR-146 blocks the activation of M1

macrophage by targeting signal transducer and activator of

transcription 1 in hepatic schistosomiasis. EBioMedicine.

13:339–347. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Liu Y, Gu Y and Cao X: The exosomes in

tumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 4:e10274722015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Cooks T, Pateras IS, Jenkins LM, Patel KM,

Robles AI, Morris J, Forshew T, Appella E, Gorgoulis VG and Harris

CC: Mutant p53 cancers reprogram macrophages to tumor supporting

macrophages via exosomal miR-1246. Nat Commun. 9:7712018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Junker K, Heinzelmann J, Beckham C, Ochiya

T and Jenster G: Extracellular vesicles and their role in urologic

malignancies. Eur Urol. 70:323–331. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|