Introduction

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), one main immune

cell population found in most solid tumors, contribute to tumor

development, progression, drug resistance and suppression of

antitumor immune cells (1–4). There are two main TAM subtypes: M1

macrophages, which encourage inflammation, and M2 macrophage, which

encourage tissue repair (5). TAMs are

mainly of the M2 phenotype (6). TAMs

are recruited to the tumor as a response to cancer-associated

inflammation (7,8) and acquire M2 properties in response to

cytokines such as tumor growth factor (TGF)-β, interleukin (IL)-10

and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). An increased

amount of M2 type TAMs is associated with a worse prognosis in

several cancer types including breast cancer (9,10).

However, recent single-cell sequencing results have shown that both

M1 and M2-associated genes are frequently expressed in the same

cells and are positively correlated with one another along the same

activation trajectory. These results have challenged the model of

macrophage polarization wherein M1 and M2 activation states are two

discrete states (11). As macrophages

affect all therapeutic modalities, further investigation of the

interplay between macrophages and tumor cells is urgently

needed.

The interplay between tumor cells and macrophage

have been revealed. For example, macrophages can release

inflammatory compounds such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α which

activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB and NF-κB regulates tumor cell

apoptosis, proliferation and inflammation. Moreover, macrophages

serve as a source for many pro-angiogenic factors including

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TNF-α, M-CSF/CSF1 and

IL-1 and IL-6 further contributing to tumor growth and metastasis

(12). In turn, tumors produce

factors, such as M-CSF/CSF1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

(MCP-1)/CCL2 and angiotensin II, triggering the amplification and

mobilization of macrophages in tumors (13–15).

Alternative splicing (AS) is a post-transcriptional

regulation process during gene expression that results in a single

gene coding for multiple proteins. AS has been proved to play

important roles in macrophage differentiation and regulation of

most tumor hallmarks (16). For

example, Liu et al found that splicing factor MBNL1

is the major regulator during the differentiation from monocytes to

macrophages (17). Human M-CSF

heterogeneity is partially derived from alternative mRNA splicing

(18). However, how tumor cells and

macrophages interplay at the alternative splicing level and its

potential application in cancer therapy remain unknown.

Understanding the tumor-macrophage crosstalk at the AS level would

reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor progression, drug

resistance and suppression of immune cells and further shade light

on the identification of new cancer therapeutic strategies.

Generally, TAMs appear to have an unfavorable role

in breast cancer (19,20). Moreover, breast cancer is considered

to be a highly heterogeneous disease, and many secreted factors may

differentially contribute to the macrophage phenotype. Therefore,

the aim of the present study was to understand macrophage

‘education’ under the influence of two breast cancer types,

estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer and

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) at the AS level in a

simplified setting. Through calculation of the number of common and

specific altered AS events, the present study aimed to ascertain:

i) Whether ER+ breast cancer and TNBC cells exert

similar influences on co-cultured macrophage cells; ii) whether

ER+ breast cancer and TNBC cells are affected to a

similar degree at the AS level in the presence of macrophages; iii)

which specific biological pathways are disturbed at the AS level in

macrophage cells when cocultured with ER+ breast cancer

and TNBC cells; iv) which specific biological pathways are

disturbed at the AS level in ER+ breast cancer and TNBC

cells at the presence of macrophage cells.

In the present study, we reanalyzed a previously

published dataset (GSE75130) and our results showed that differing

from transcriptional analysis, DNA repair and DNA damage processes

were enriched in both ER+ breast cancer and TNBC after

co-culturing with macrophages, which indicated the conserved

functional regulation of macrophages on tumor cells in the tumor

microenvironment. Meanwhile, macrophages were differentially

regulated from the pathway views by co-culturing with

ER+ breast cancer and TNBC cells. Sequence features of

skipped exons from different conditions were also characterized in

our analysis.

Materials and methods

GEO dataset GSE75130 was reanalyzed (21) which was originally used to

characterize the differences in macrophage activation under the

influence of either ER+ breast cancer or TNBC cells. For

detailed treatment procedures please refer to a previous study

(21).

Profiling of gene expression

Paired-end reads were mapped to the human genome

primary assembly (GRCh37) (22), and

the Ensembl human gene annotation for GRCh37 genebuild was used to

improve the accuracy of the mapping with STAR software

(STAR_2.4.2a) (23). FeatureCounts

(version 1.4.6-p5) (24) was used to

assign sequence reads to genes. Mitochondrial genes, ribosomal

genes, and genes possessing less than five raw reads in half the

samples were removed. Normalized gene expression profiles were

obtained with the edgeR package 1.6 (25).

Alternative splicing analysis

For AS analysis, MISO software (version 0.5.4)

(26) was used to analyze RNA-Seq

data and estimate the percentage of splicing isoforms. Firstly, we

utilized MISO to achieve the AS profiles for each treated sample

and 5 types of AS profiles including alternative 3′/5′ splice site

(A3SS, A5SS), skipped exons (SE), mutually exclusive exons (MXE)

and retained introns (RI) were obtained. AS profiles were

represented by percentage of splice-in (PSI/Ψ) values. Secondly, we

identified the delta PSI (ΔPSI) by comparing the cocultured sample

with individually cultured sample. Finally, we determine the

significantly different AS events by Bayes factor >6 and

|ΔPSI|>0.2.

Principal component analysis

(PCA)

PCA was performed as previously described (27). A total of 20,169 genes were accounted

for in PCA of the whole transcriptome. Expression was normalized

with the reads per million mapped reads (RPM) method. The prcomp

package from R was used to perform PCA and the default parameters

were used (28). The ggplot2 package

from R was used to draw the scatter plot (29). A total of 36,377 AS events were

utilized in the PCA of the ER+ breast cancer and TNBC

transcriptome analysis. A total of 35,476 AS events were utilized

in the PCA of the macrophage transcriptome analysis.

Functional enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis was

conducted with webserver DAVID 6.8 (30). P<0.05 was considered as

statistically significant. Background gene list was set to 16,133

esemble genes which possess alternative splicing isoforms.

Protein-protein interaction

analysis

Web server STRING (31) was utilized to explore the

protein-protein interactions. Default parameters were applied.

NCBI protein domain analysis

Protein domains of full-length CHEK2 (accession no.

CAG30304.1) was analyzed with NCBI webserver (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (32). Two significant protein domains were

identified. The first domain is STKc_Chk2 (accession: cd14084) and

the second is FHA (accession: cd00060).

Evolutionary conservation

Placental Mammal PhastCons scores were used to

represent evolutionary conservation. For average conservation of

exons, bigWigAverageOverBed (33) was

used to calculate the mean conservation across each exon. The

ggplot2 package from R was used to draw the box plot (29).

3′ and 5′splicing strength

To evaluate splice site strength, 3′ of the

exon-intron boundary (20 nt into intron and +3 nt into exon) and 5′

of the exon-intron boundary (3 nt into exon and +6 nt into intron),

together with the transcript sequences for these regions were

obtained by bedtools (34).

MaxEntScan (35) was used to

calculate the strength of the splice sites for the AS exons.

Repetitive element enrichment

To identify repetitive elements in AS exons, Repeat

Masker track was downloaded from UCSC Genome Browser and

intersected with AS exons by bedtools intersect (34). Repeats were grouped into families

defined by the Pfam database of repetitive DNA elements.

Phylostratum scores were used to describe gene age, as previously

reported (36).

Association between 222 splicing

factors and altered AS events

Overlap of gene-associated events and conditional

specific events (macrophages vs. macrophages co-cultured with T47D

cells; macrophages vs. macrophages co-cultured with MDA-MB-231

cells; T47D cells vs. T47D cells co-cultured with macrophages; and

MDA-MB-231 cells vs. MDA-MB-231 cells co-cultured with macrophages)

were used to assess how much of the conditional specific events

could be explained by each splicing factor. First, conditional

specific ES events were isolated by comparing splicing events from

treatment samples against those from the control samples. The

significant splicing events were determined based on Bayes factor

>6 and |ΔPSI| >0.2. Second, gene-associated ES events were

determined by correlation analyses using gene expression levels

(RPKM) and PSI values across all samples. Correlation coefficients

(R-value) and corresponding P-values were calculated with the

Pearson method, and gene-associated events were determined by

R>0.2 and P<0.0001. Common events were considered as events

that occurred (overlapped) in both gene-associated and conditional

specific events. Finally, top 5 splicing factors which explain the

most conditional specific events were isolated.

Statistical analyses

Significantly different AS events were determined by

Bayes factor >6 and |ΔPSI|>0.2 during comparison of AS events

between cocultured state and single cultured state. Fisher exact

test was applied to test significance of GO term enrichment and

P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. R>0.2 and

P<0.0001 were applied to identify significantly associated AS

events to a specific splicing factor across 14 samples in this

study. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to test significance

in Fig. 6A-D and P<0.05 was set to

determine significance. Fisher's exact test was used to test

significant enrichment of each elements and P-values were-log10

transformed to plot the heatmap in Fig.

6E.

Results

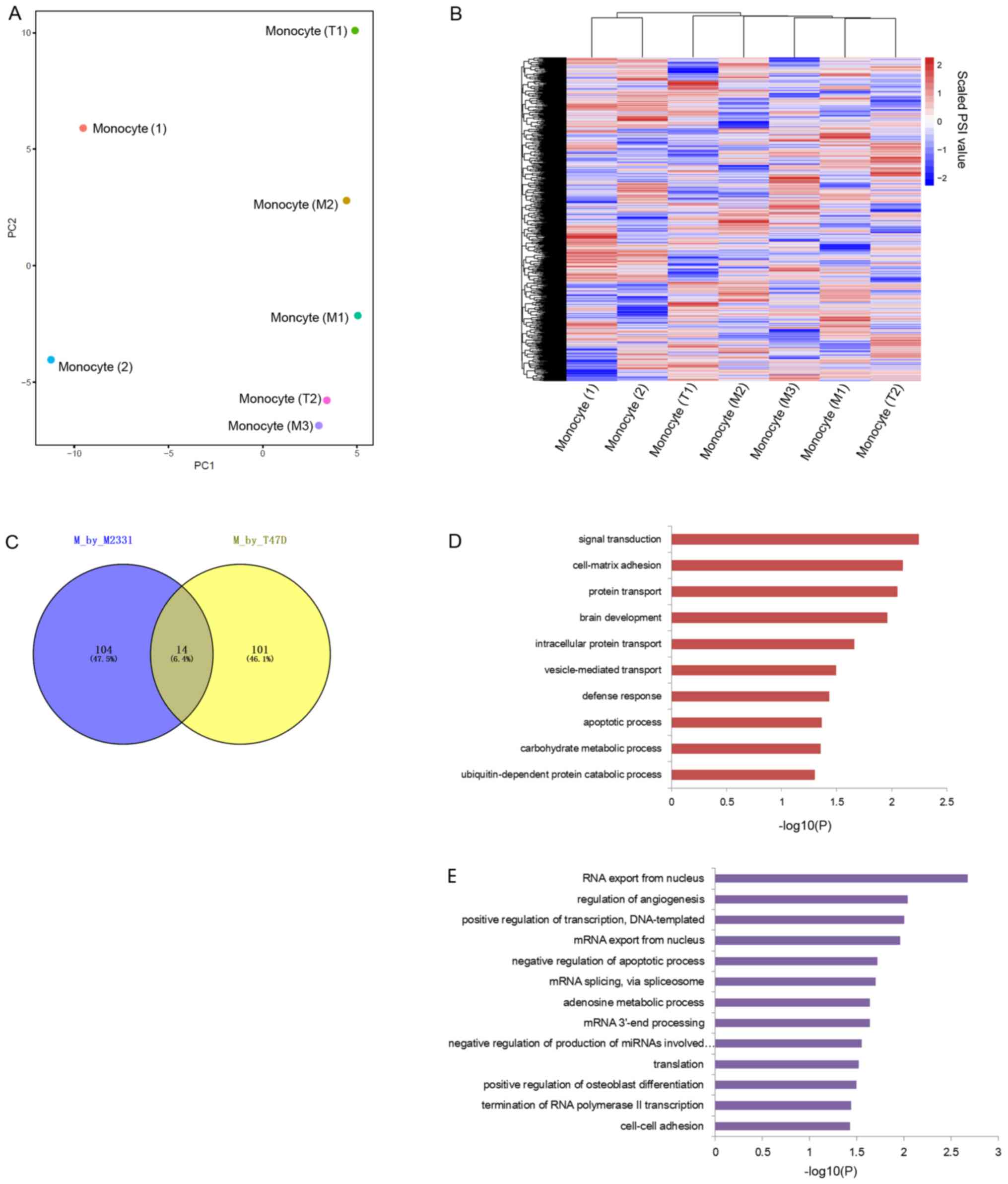

Confirmation of data reliability

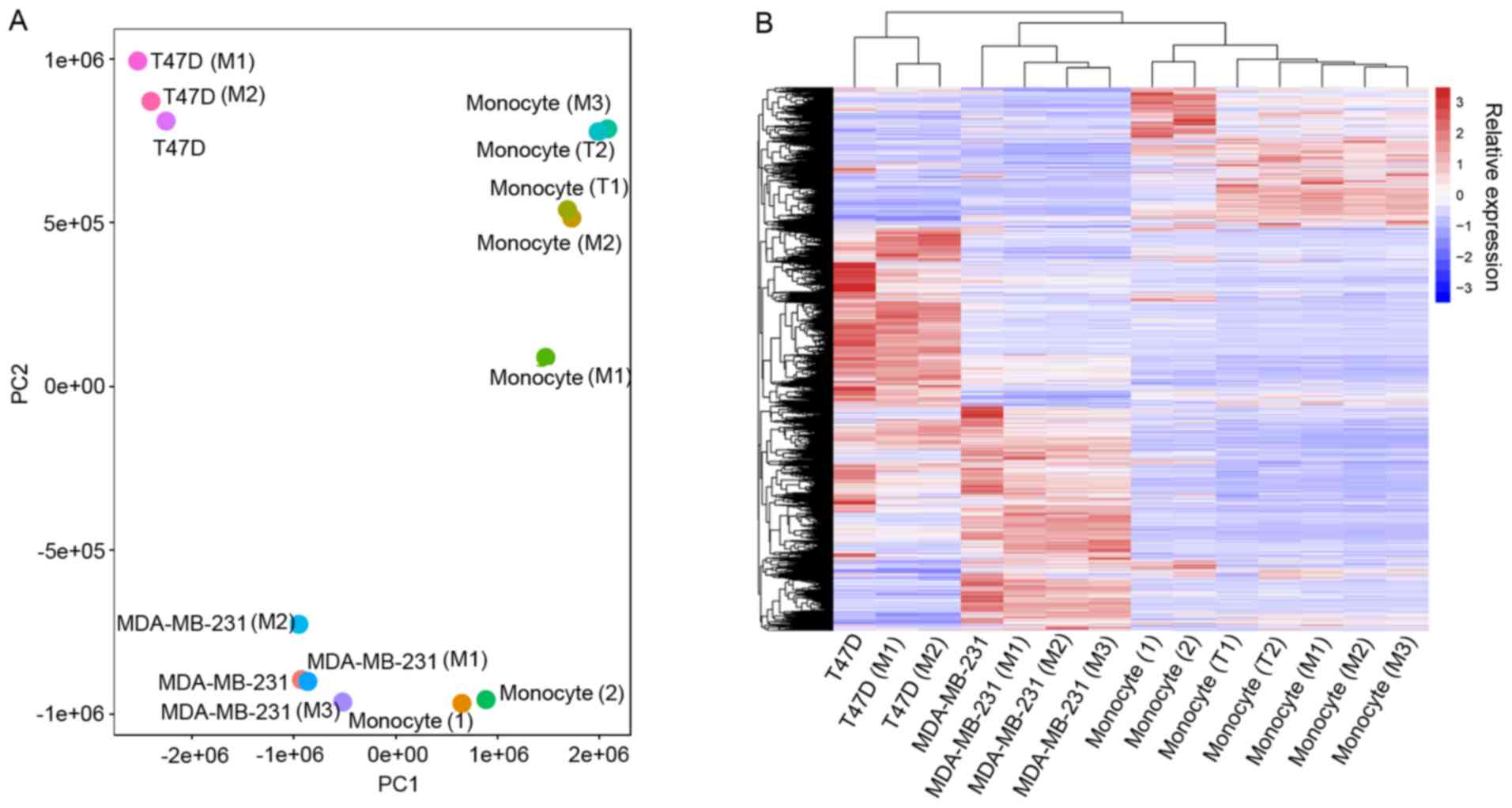

To investigate the interplay between breast cancer

cells and macrophages at the alternative splicing level, we

downloaded one dataset from a previous study (21). In this previous study, freshly

isolated human peripheral monocytes were cultured with two breast

cancer cell lines (T47D, ER+ and MDA-MB-231, TNBC) in an

in vitro Transwell co-culture assay. Then, at day five, the

whole transcriptome of macrophage cells and breast tumor cells were

sequenced. Detailed sample information was previously described

(22). We firstly evaluated the data

reliability by investigating the genetic variance among samples

using gene expression profiles based on the assumption that samples

from the same cell type and treatment should have smaller genetic

distances. PCA was performed with 20,169 genes and the results

showed that samples were grouped together according to the types

and treatments (Fig. 1A). Then

unsupervised clustering based on the same transcriptomes confirmed

the dataset reliability (Fig.

1B).

DNA damage and DNA repair pathways are

altered in both MDA-MB-231 and T47D cell lines by co-culturing with

macrophages

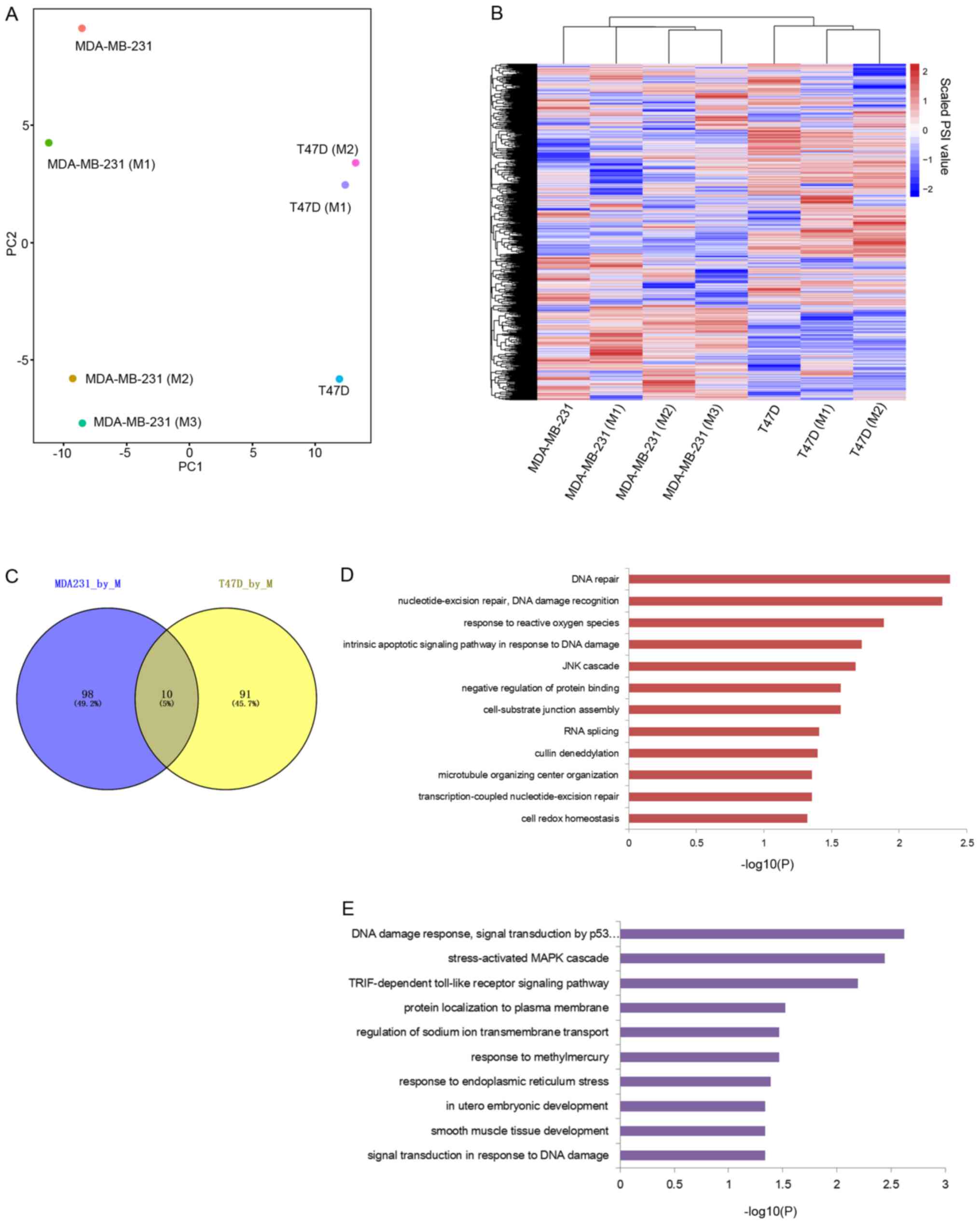

Next, we aimed to ascertain how macrophages educate

different breast cancer cells at the AS level. To obtain the AS

profile for each sample, we performed the Mixture of Isoforms

(MISO) pipeline (26) according to

its recommended procedure (https://miso.readthedocs.io/en/fastmiso/). Five types

of AS events including skip exon (SE), alternative 3′/5′ splice

sites (A3SS, A5SS), mutually exclusive exons (MXE), and retained

introns (RI) were analyzed. A total of 36,377 splicing events with

values at least in 7 samples were identified. Then, PCA and

unsupervised clustering were used to characterize the genetic

distances among samples. The PCA result showed that both T47D and

MDA-MB-231 individually cultured samples were obviously separated

from their macrophage co-cultured states (Fig. 2A). Unsupervised clustering result also

supported that co-cultured breast cancer cells were different from

the individually cultured states (Fig.

2B). These results indicated that AS profiles of both TNBC and

ER+ breast cancer were affected by co-culturing with

macrophages.

Then, it was further determined which AS events were

affected in each breast caner type and whether the altered AS

events from two breast cancer types were largely similar or

different. We isolated those altered splicing events by comparing

the co-cultured states with individually cultured states from T47D

and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. Statistically different

splicing events with delta percentage of splice-in (ΔPSI) >0.2

and bayes factor >6 were isolated. A total of 101 and 108

different splicing events were identified from T47D and MDA-MB-231

cell lines, respectively (Tables I

and II) and there were 10 common

splicing events in both T47D and MDA-MB-231 altered splicing

events. All of these results indicated that ER+ breast

cancer cells and TNBC cells were differently ‘educated’ at the AS

level by co-culturing with the macrophages (Fig. 2C).

| Table I.Altered AS events in MDA-MB-231 cells

co-cultured with macrophages. |

Table I.

Altered AS events in MDA-MB-231 cells

co-cultured with macrophages.

| Gene | Events | ΔPSI

(SRR2922607_vs_SRR2922615) | ΔPSI

(SRR2922607_vs_SRR2922617) |

|---|

| GPS1 |

chr17:80009763:80009840:+@chr17:80010135:80010335:+@chr17:80011150:80011242:+ | 0.68 | 0.57 |

| NA |

chr17:79520100:79520153:-@chr17:79518954:79519078:-@chr17:79517274:79518229:- | 0.62 | 0.61 |

| INO80B,

WBP1 |

chr2:74685527:74685798:+@chr2:74685959:74686046:+@chr2:74686565:74686872:+ | 0.60 | 0.48 |

| TSC1 |

chr9:135786955-135786840:-@chr9:135786500-135786389:- | 0.50 | 0.44 |

| MTRF1 |

chr13:41837621:41837713:-@chr13:41836547:41836617:-@chr13:41836184:41836467:-@chr13:41834629:41835051:- | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| CTDP1 |

chr18:77477810:77478016:+@chr18:77488907:77489069:+@chr18:77496355:77496521:+ | 0.46 | 0.36 |

| HAUS2 |

chr15:42851537:42851606:+@chr15:42852980:42853068:+@chr15:42853468:42853600:+ | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| VWA9 |

chr15:65903469:65903134|65903436:-@chr15:65899497:65899763:- | 0.44 | 0.45 |

| PFDN5 |

chr12:53689235:53689423:+@chr12:53690214|53691634:53691708:+ | 0.44 | 0.66 |

| SPAG9 |

chr17:49054469:49054582:-@chr17:49053224:49053262:-@chr17:49052132:49052308:- | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| PPCDC |

chr15:75315927:75315967:+@chr15:75320588:75320794:+@chr15:75335782:75335877:

+@chr15:75340894:75341062:+ | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| OGG1 |

chr3:9796388:9796569:+@chr3:9798451:9798500:+@chr3:9807493:9808353:+ | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| ATG12 |

chr5:115177087:115177548:-@chr5:115176515:115176631:-@chr5:115176194:115176309:-@chr5:115173325:115173461:- | 0.41 | 0.34 |

| RHOC,

PPM1J |

chr1:113249700:113250025:-@chr1:113247790|113248874:113247722:- | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| RBM25 |

chr14:73566375-73566458:+@chr14:73569900-73570186:+ | 0.40 | 0.39 |

|

KIAA1551 |

chr12:32123123:32123290:+@chr12:32133812:32138891:+@chr12:32140173:32140256:+ | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| WDR26 |

chr1:224619283:224619179|224619227:-@chr1:224612220:224612356:- | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| PRPF4B |

chr6:4060647-4060920:+@chr6:4061249-4061381:+ | 0.37 | 0.34 |

| PRDX5 |

chr11:64085560:64085858:+@chr11:64087206:64087340:+@chr11:64088337:64088375:+ | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| PFKM |

chr12:48528726:48528821|48529166:+@chr12:48531504:48531629:+ | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| MAP2K7 |

chr19:7968765:7968953:+@chr19:7970693:7970740:+@chr19:7974640:7974781:+ | 0.35 | 0.31 |

| NFATC4 |

chr14:24845500:24845760|24846084:+@chr14:24846844:24848810:+ | 0.34 | 0.33 |

| NAV3 |

chr12:78515720:78516208:+@chr12:78520947:78520988:+@chr12:78522486:78522646:+ | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| APEX1 |

chr14:20923737-20923932:+@chr14:20924073-20924260:+ | 0.33 | 0.21 |

| VWA9 |

chr15:65903486:65903024|65903134:-@chr15:65899497:65899780:- | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| TAGLN |

chr11:117070040:117070148|117070545:+@chr11:117073718:117073909:+ | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| SOD2 |

chr6:160103670-160103506:-@chr6:160100330-160100096:- | 0.33 | 0.40 |

| UBXN1 |

chr11:62444990:62445106:-@chr11:62444111|62444477:62443972:- | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| SDR39U1 |

chr14:24911552:24911658:-@chr14:24911384:24911466:-@chr14:24910880:24911001:- | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| ITGA6 |

chr2:173362703:173362828:+@chr2:173366500:173366629:+@chr2:173368819:173371181:+ | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| TSPAN4 |

chr11:842824:842915:+@chr11:847201:847300:+@chr11:850288:850367:+@chr11:862550:862741:+ | 0.32 | 0.37 |

|

C16orf13 |

chr16:686094:686347:-@chr16:685612:685774:-@chr16:685281:685340:- | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| VWA9 |

chr15:65903469:65903134|65903436:-@chr15:65899497:65899780:- | 0.3 | 0.33 |

| RPAIN |

chr17:5329291-5329619:+@chr17:5331391-5331531:+ | 0.29 | 0.27 |

|

SUV420H1 |

chr11:67980944:67981068:-@chr11:67957384:67957619:-@chr11:67953248:67953395:- | 0.29 | 0.38 |

| COX7A2 |

chr6:75950892:75950981:-@chr6:75949993:75950101:-@chr6:75947391:75947704:- | 0.28 | 0.32 |

| ZNRD1 |

chr6:30029036-30029175:+@chr6:30029292-30029446:+ | 0.28 | 0.38 |

| GNB2L1 |

chr5:180669170:180669345:-@chr5:180668563|180668639:180668492:- | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| ERRFI1 |

chr1:8075555:8075752:-@chr1:8075368:8075460:-@chr1:8071779:8074456:- | 0.27 | 0.30 |

|

SLC25A35 |

chr17:8192961-8192892:-@chr17:8191750-8191082:- | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| GOLGA2 |

chr9:131036129:131036251:-@chr9:131035064:131035144:-@chr9:131030699:131030803:- | 0.27 | 0.39 |

| NA |

chr14:105180540:105181193:+@chr14:105181621:105181677:+@chr14:105185132:105185947:+ | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| RFWD3 |

chr16:74700684:74700779:-@chr16:74698522:74698643:-@chr16:74694830:74695349:-@chr16:

74685818:74686020:- | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| SEC23A |

chr14:39572797:39573033:-@chr14:39572236:39572432:-@chr14:39565102:39565343:-@chr14:39562391:39562448:- | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| RPS21 |

chr20:60962899-60962970:+@chr20:60963365-60963576:+ | 0.26 | 0.30 |

| TXNRD1 |

chr12:104680460:104680887:+@chr12:104682709:104682818:+@chr12:104705068:104705190:

+@chr12:104707023:104707095:+ | 0.26 | 0.39 |

| ALG13 |

chrX:110928193:110928331:+@chrX:110929365:110929402:+@chrX:110931115:110933623:+ | 0.25 | 0.20 |

| MTRF1 |

chr13:41837621:41837713:-@chr13:41836184:41836467:-@chr13:41834629:41835051:- | 0.25 | 0.21 |

|

C16orf13 |

chr16:686094:686347:-@chr16:685518:685774:-@chr16:685281:685340:- | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| PHC2 |

chr1:33799893:33799691|33799786:-@chr1:33797876:33798005:- | 0.24 | 0.26 |

|

C16orf13 |

chr16:686094:686347:-@chr16:685518:685774:-@chr16:685281:685340:-@chr16:684719:684797:- | 0.24 | 0.30 |

| PTPN3 |

chr9:112189230:112189402:-@chr9:112184998:112185132:-@chr9:112182704:112182880:- | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| BAX |

chr19:49464067-49464171:+@chr19:49464789-49465055:+ | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| PFKM |

chr12:48528726:48528821:+@chr12:48529074:48529166:+@chr12:48531504:48531629:+ | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| TMEM41B |

chr11:9305140-9304918:-@chr11:9302588-9302201:- | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| NCAPG2 |

chr7:158444985:158445172:-@chr7:158443524:158443664:-@chr7:158439152:158439255:- | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| MTRF1L |

chr6:153316454:153316271|153316379:-@chr6:153315648:153315811:- | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| ORMDL1 |

chr2:190648995:190649097:-@chr2:190647740:190647849:-@chr2:190647148:190647328:- | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| RHOC,

PPM1J |

chr1:113249700:113250025:-@chr1:113247722:113248874:-@chr1:113246266:113246428:- | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| BCAS3 |

chr17:59093112:59093262:+@chr17:59104227:59104271:+@chr17:59112027:59112151:+ | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| TSPAN4 |

chr11:844081:844186:+@chr11:847201:847300:+@chr11:850288:850367:+@chr11:862550:862741:+ | 0.22 | 0.27 |

| NFATC4 |

chr14:24845500-24845760:+@chr14:24846844-24848810:+ | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| DRAM2 |

chr1:111663315:111663138|111663154:-@chr1:111662499:111662581:- | 0.20 | 0.23 |

| ANKRD49 |

chr11:94229770-94230117:+@chr11:94231237-94232744:+ | 0.20 | 0.28 |

| MEF2A |

chr15:100185766:100185969:+@chr15:100211528:100211659:+@chr15:100211725:100211862:

+@chr15:100214598:100214817:+ | −0.2 | −0.33 |

| NCOR2 |

chr12:124812179:124811955|124812093:-@chr12:124810737:124810916:- | −0.20 | −0.24 |

| TSPAN4 |

chr11:847201:847300:+@chr11:850288:850367:+@chr11:862550:862741:+ | −0.20 | −0.22 |

| CYB5B |

chr16:69458498:69458760:+@chr16:69481053:69481181:+@chr16:69492996:69493024:+@chr16:

69496333:69500167:+ | −0.20 | −0.21 |

| MIR3654,

EEF1G |

chr11:62342380-62342149:-@chr11:62340214-62340056:- | −0.21 | −0.22 |

| MKNK2 |

chr19:2040133:2040176:-@chr19:2037828|2039855:2037470:- | −0.22 | −0.29 |

| NA |

chr19:3638882:3639014:-@chr19:3633435:3633518:-@chr19:3630179:3633167:- | −0.22 | −0.24 |

| YKT6 |

chr7:44250622:44250723:+@chr7:44251153:44251203:+@chr7:44251846:44253893:+ | −0.22 | −0.23 |

| FN1 |

chr2:216246935:216247048:-@chr2:216245534:216245803:-@chr2:216243853:216244040:- | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| MBNL2 |

chr13:98009736:98009889:+@chr13:98017390:98017425:+@chr13:98018713:98018807:

+@chr13:98043576:98046374:+ | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| ARL6IP4,

RP11-197N18.2 |

chr12:123465676:123465813|123465846:+@chr12:123466118:123466426:+ | −0.23 | −0.21 |

| UBC |

chr12:125398665:125398551|125398587:-@chr12:125398042:125398320:- | −0.24 | −0.27 |

| C9orf9 |

chr9:135763677-135763824:+@chr9:135765344-135765418:+ | −0.24 | −0.26 |

| MRRF |

chr9:125026882:125027217:+@chr9:125027741:125027824:+@chr9:125033143:125033354:+ | −0.25 | −0.32 |

| SPNS1 |

chr16:28986096:28986713:+@chr16:28986813:28986878:+@chr16:28989229:28989365:

+@chr16:28990476:28990627:+ | −0.25 | −0.26 |

|

AC124789.1 |

chr17:36607870:36608071:-@chr17:36607550:36607769:-@chr17:36606638:36606967:- | −0.25 | −0.23 |

| TBRG1 |

chr11:124495567:124495799:+@chr11:124496369:124496505:+@chr11:124496800:124496946:+ | −0.25 | −0.21 |

| H2AFY |

chr5:134696187:134696297:-@chr5:134688636:134688735:-@chr5:134686513:134686603:-

@chr5:134681658:134681747:- | −0.26 | −0.38 |

| NAV3 |

chr12:78513017:78513725:+@chr12:78515720:78516208:+@chr12:78522486:78522646:+ | −0.26 | −0.27 |

|

AC124789.1 |

chr17:36607870:36608071:-@chr17:36607550:36607637:-@chr17:36606638:36606967:- | −0.26 | −0.25 |

| LRRC28 |

chr15:99796103:99796330:+@chr15:99816781:99816821:+@chr15:99827462:99827499:+ | −0.30 | −0.42 |

| OSBPL3 |

chr7:24903115:24903218:-@chr7:24902819:24902911:-@chr7:24901232:24901388:- | −0.30 | −0.33 |

| TBRG1 |

chr11:124495567:124495799:+@chr11:124496369:124496505:+@chr11:124496589:

124496647:+@chr11:124496800:124496946:+ | −0.30 | −0.32 |

| NA |

chr17:57232800:57232317|57232492:-@chr17:57187308:57189706:- | −0.30 | −0.29 |

| EEF1D |

chr8:144679518:144679845:-@chr8:144674817:144675063:-@chr8:144671161:144672251:- | −0.31 | −0.32 |

| NBPF12 |

chr1:146395307:146395516:+@chr1:146397359:146397461:+@chr1:146398293:146398507:+ | −0.32 | −0.32 |

| NA |

chr6:30524486:30525227:+@chr6:30525927:30525989:+@chr6:30529105:30529285:+@chr6:

30529611:30529901:+ | −0.32 | −0.31 |

| UBAP2L |

chr1:154241233:154241430:+@chr1:154241838:154241888:+@chr1:154242676:154243329:+ | −0.33 | −0.20 |

| ASB8 |

chr12:48551242:48551377:-@chr12:48547308|48547312:48547151:- | −0.35 | −0.33 |

| PARP3 |

chr3:51976361:51976724:+@chr3:51977365|51977370:51977554:+ | −0.35 | −0.33 |

| EEF1D |

chr8:144679518:144679845:-@chr8:144674817:144675063:-@chr8:144672815:144672908:-

@chr8:144671161:144672251:- | −0.36 | −0.40 |

| MBNL2 |

chr13:98009736:98009889:+@chr13:98018713:98018807:+@chr13:98043576:98046374:+ | −0.36 | −0.37 |

| ATG12 |

chr5:115176515:115176631:-@chr5:115176194:115176309:-@chr5:115173325:115173461:- | −0.37 | −0.46 |

| GCOM1,

POLR2M |

chr15:57967166:57967266:+@chr15:57976600:57976872:+@chr15:57998132:57999153:

+@chr15:58001383:58001556:+ | −0.37 | −0.41 |

| COPS7B |

chr2:232646417:232646593:+@chr2:232653265:232653442:+@chr2:232658973:232659061:

+@chr2:232660816:232661018:+ | −0.37 | −0.34 |

| ZNF507 |

chr19:32836514:32836689:+@chr19:32838151:32838244:+@chr19:32843735:32845863:+ | −0.40 | −0.41 |

| EEF1D |

chr8:144679518:144679845:-@chr8:144674817:144675063:-@chr8:144672778:144672908:- | −0.41 | −0.43 |

|

C17orf70 |

chr17:79519078:79518758|79518954:-@chr17:79517274:79518229:- | −0.43 | −0.48 |

| SAFB |

chr19:5667057:5667175:+@chr19:5667358|5667364:5667461:+ | −0.47 | −0.54 |

| FGFR1 |

chr8:38314874:38315052:-@chr8:38287200:38287466:-@chr8:38285864:38285953:- | −0.47 | −0.32 |

| PIK3CD |

chr1:9711790:9711860:+@chr1:9751525:9751629:+@chr1:9770163:9770338:+@chr1:9770482:9770654:+ | −0.53 | −0.47 |

| ACADVL |

chr17:7127132-7127194:+@chr17:7127287-7127388:+ | −0.57 | −0.62 |

| STAG2 |

chrX:123095164:123095285:+@chrX:123095636:123095706:+@chrX:123155217:123155281:

+@chrX:123156381:123156521:+ | −0.57 | −0.61 |

| NME3 |

chr16:1821411-1821270:-@chr16:1821172-1821071:- | −0.67 | −0.49 |

| Table II.Altered AS events in T47D cells

co-cultured with macrophages. |

Table II.

Altered AS events in T47D cells

co-cultured with macrophages.

| Gene | Events | ΔPSI

(SRR2922618_vs_SRR2922619) | ΔPSI

(SRR2922618_vs_SRR2922620) |

|---|

| UBQLN1 |

chr9:86284100:86284242:-@chr9:86281265:86281309:-@chr9:86279945:86280060:- | −0.49 | −0.57 |

| PFDN5 |

chr12:53689235:53689423:+@chr12:53690214|53691634:53691708:+ | −0.64 | −0.54 |

| ARMC8 |

chr3:137906148:137906441:+@chr3:137907297:137907372:+@chr3:137928659:137928735:+ | −0.61 | −0.53 |

| SENP2 |

chr3:185316200:185316333:+@chr3:185316780:185316812:+@chr3:185318553:185318643:+ | −0.59 | −0.52 |

| RRN3 |

chr16:15185172:15185228:-@chr16:15180222:15180311:-@chr16:15179986:15180115:- | −0.32 | −0.51 |

| SULF1 |

chr8:70378859:70379185:+@chr8:70408000:70408161:+@chr8:70414109:70414203:+ | −0.44 | −0.50 |

| NA |

chr5:10236590:10236727:-@chr5:10235323:10235373:-@chr5:10225620:10227759:- | −0.45 | −0.49 |

| NA |

chr6:30524486:30525227:+@chr6:30525927:30525989:+@chr6:30529611:30529901:+ | −0.47 | −0.47 |

| VAMP1 |

chr12:6574107-6574056:-@chr12:6572008-6571404:- | −0.43 | −0.45 |

| ZFAND6 |

chr15:80364903:80364989:+@chr15:80390758:80390920:+@chr15:80412670:80412840:+ | −0.38 | −0.45 |

| CNOT1 |

chr16:58663632:58663790:-@chr16:58658557:58658698:-@chr16:58657186:58657313:-

@chr16:58633140:58633415:- | −0.38 | −0.45 |

|

C16orf13 |

chr16:686094:686347:-@chr16:685612:685774:-@chr16:685281:685340:- | −0.31 | −0.45 |

| 43349 |

chrX:118759298:118759342:-@chrX:118752749|118754014:118750909:- | −0.28 | −0.45 |

| SP140L |

chr2:231253274:231253348:+@chr2:231254634:231254738:+@chr2:231256802:231256944:+ | −0.39 | −0.44 |

| TMEM91, BCKDHA,

CTC-435M10.3 |

chr19:41888677:41888826:+@chr19:41889466:41889537:+@chr19:41889768:41889987:+ | −0.29 | −0.44 |

| VAMP1 |

chr12:6574107-6574056:-@chr12:6572008-6571403:- | −0.40 | −0.43 |

| IKBKB |

chr8:42128820:42128987:+@chr8:42129601:42129723:+@chr8:42146152:42146246:

+@chr8:42147674:42147791:+ | −0.75 | −0.41 |

| FKBP14 |

chr7:30062281:30062432:-@chr7:30059829:30059920:-@chr7:30058612:30058739:- | −0.40 | −0.41 |

| NCOR2 |

chr12:124862783:124862930:-@chr12:124858959:124859009:-@chr12:124856568:124857156:- | −0.33 | −0.41 |

| ANAPC11 |

chr17:79849599:79849709|79849717:+@chr17:79852343:79852462:+ | −0.36 | −0.40 |

| MYO5A |

chr15:52638558:52638658:-@chr15:52635314:52635394:-@chr15:52632393:52632591:- | −0.37 | −0.39 |

|

C16orf13 |

chr16:686094:686347:-@chr16:685518:685774:-@chr16:685281:685340:-@chr16:684719:684797:- | −0.27 | −0.38 |

| PTPN3 |

chr9:112189230:112189402:-@chr9:112184998:112185132:-@chr9:112182704:112182880:- | −0.29 | −0.37 |

| 43349 |

chrX:118763281:118763471:-@chrX:118752749|118754014:118750909:- | −0.29 | −0.37 |

|

ATP6V0D1 |

chr16:67514860:67515089:-@chr16:67478431:67478609:-@chr16:67477002:67477081:- | −0.31 | −0.36 |

| PILRB,

CTB-161A2.4 |

chr7:99950187-99950537:+@chr7:99950620-99950746:+ | −0.37 | −0.35 |

| NA |

chr3:37396592:37396678:+@chr3:37402734:37402796:+@chr3:37407571:37408370:+ | −0.26 | −0.35 |

| MUC1 |

chr1:155160639:155160707:-@chr1:155160198:155160334:-@chr1:155159701:155159850:- | −0.37 | −0.34 |

| DALRD3 |

chr3:49058279:49058467:-@chr3:49055833:49055986:-@chr3:49055456:49055751:- | −0.33 | −0.34 |

|

RP11-66N24.4 |

chr14:24025198:24025552:+@chr14:24025952:24026243:+@chr14:24027904:24028790:+ | −0.31 | −0.34 |

| ZNRD1 |

chr6:30029036-30029175:+@chr6:30029292-30029446:+ | −0.31 | −0.33 |

| NA |

chr7:75633076:75633173:-@chr7:75630208:75630272:-@chr7:75625655:75625917:- | −0.36 | −0.32 |

| DLG1 |

chr3:196921296:196921460:-@chr3:196888511:196888609:-@chr3:196876614:196876667:- | −0.3 | −0.32 |

| NEIL2 |

chr8:11627172:11627300:+@chr8:11627683:11627844:+@chr8:11628955:11629094:+ | −0.29 | −0.32 |

|

C16orf13 |

chr16:686094:686347:-@chr16:685518:685774:-@chr16:685281:685340:- | −0.21 | −0.32 |

| TPD52L1 |

chr6:125574863:125574901:+@chr6:125578244:125578304:+@chr6:125583980:125584644:+ | −0.37 | −0.31 |

| ORMDL1 |

chr2:190648995:190649097:-@chr2:190647740:190647849:-@chr2:190647148:190647328:- | −0.36 | −0.31 |

| ORMDL1 |

chr2:190648995:190649097:-@chr2:190647328|190647849:190647148:- | −0.40 | −0.29 |

| SMPD4 |

chr2:130921947:130922018:-@chr2:130918759:130918845:-@chr2:130914824:130914969:- | −0.34 | −0.29 |

| AP001055.7,

C21orf33 |

chr21:45553494:45553720:+@chr21:45553984:45554036:+@chr21:45555942:45556055:+ | −0.26 | −0.28 |

| NA |

chr22:50964675:50964905:-@chr22:50964430:50964570:-@chr22:50961997:50962853:- | −0.25 | −0.28 |

| NA |

chr17:5326089:5326149:+@chr17:5331391:5331531:+@chr17:5335862:5336340:+ | −0.34 | −0.27 |

| NA |

chr10:14920782:14920918:+@chr10:14923499:14923644:+@chr10:14938845:14939516:+ | −0.29 | −0.27 |

| C1orf52 |

chr1:85725041:85725355:-@chr1:85724618:85724744:-@chr1:85724207:85724405:- | −0.28 | −0.27 |

|

RP11-66N24.4 |

chr14:24025198:24025552:+@chr14:24025952:24026248:+@chr14:24027904:24028790:+ | −0.27 | −0.27 |

| ISYNA1 |

chr19:18548670:18548798:-@chr19:18547289|18547915:18547140:- | −0.26 | −0.27 |

| ENTPD6 |

chr20:25176339:25176503:+@chr20:25187158:25187226:+@chr20:25187712:25188033:+ | −0.23 | −0.26 |

| NA |

chr11:72983352:72983511:+@chr11:73006775:73006860:+@chr11:73007530:73009664:+ | −0.31 | −0.25 |

| MBD1 |

chr18:47801347:47801415:-@chr18:47800556:47800723:-@chr18:47799934:47800233:- | −0.26 | −0.25 |

| CRYZ |

chr1:75175782:75175931:-@chr1:75172787:75172888:-@chr1:75172583:75172678:- | −0.25 | −0.25 |

| SLMAP |

chr3:57908616:57908750:+@chr3:57911572:57911661:+@chr3:57913023:57914894:+ | −0.24 | −0.25 |

| ZMYM2 |

chr13:20567203-20567704:+@chr13:20567966-20568059:+ | −0.32 | −0.24 |

| CHEK2 |

chr22:29095826:29095925:-@chr22:29092889:29092975:-@chr22:29091698:29091861:- | −0.28 | −0.24 |

| MBD1 |

chr18:47801347:47801415:-@chr18:47800556:47800720:-@chr18:47799934:47800233:- | −0.25 | −0.24 |

| ATP5J |

chr21:27107965:27107164|27107626:-@chr21:27101942:27102112:- | −0.24 | −0.24 |

| UBE2D3 |

chr4:103749101:103749307:-@chr4:103748749:103748898:-@chr4:103747642:103747793:- | −0.22 | −0.24 |

| ATP13A3 |

chr3:194134488:194134568:-@chr3:194132928:194133017:-@chr3:194123403:194126845:- | −0.27 | −0.23 |

| MBD1 |

chr18:47801499:47801615:-@chr18:47801347:47801415:-@chr18:47800556:47800723:-

@chr18:47799934:47800233:- | −0.25 | −0.23 |

| SDR39U1 |

chr14:24911552:24911658:-@chr14:24911384:24911466:-@chr14:24910880:24911001:- | −0.23 | −0.23 |

| CTAGE5,

MIA2 |

chr14:39788413:39788495:+@chr14:39790132:39790260:+@chr14:39796068:39796226:+ | −0.27 | −0.22 |

| PAK4 |

chr19:39660172:39660397:+@chr19:39663558:39663746:+@chr19:39664216:39664650:+ | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| ZFAND5 |

chr9:74979612:74980163:-@chr9:74978386:74978522:-@chr9:74975544:74975703:- | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| CLDND1,

CPOX |

chr3:98241693:98241910:-@chr3:98240497:98240547:-@chr3:98239977:98240286:- | −0.36 | −0.21 |

| NA |

chr7:75039605:75039743:+@chr7:75039889:75040009:+@chr7:75044163:75044301:+ | −0.33 | −0.21 |

| HSPA14 |

chr10:14882074:14882156:+@chr10:14884133:14884845:+@chr10:14885370:14886747:+ | −0.25 | −0.21 |

| TPD52L1 |

chr6:125569428:125569529:+@chr6:125574863:125574901:+@chr6:125578244:125578304:

+@chr6:125583980:125584644:+ | −0.26 | −0.20 |

| LGMN |

chr14:93176017:93176217:-@chr14:93170985:93171052:-@chr14:93170152:93170706:- | −0.24 | −0.20 |

| GGCX |

chr2:85788509:85788657:-@chr2:85787938:85788108:-@chr2:85786040:85786198:- | −0.22 | −0.20 |

| OS9 |

chr12:58112776:58112965:+@chr12:58113882:58114046:+@chr12:58114189:58114301:+ | −0.22 | −0.20 |

| UBC |

chr12:125398665:125398551|125398587:-@chr12:125398042:125398320:- | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| MRPL9 |

chr1:151735622:151735431|151735466:-@chr1:151734852:151734976:- | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| EEF1D |

chr8:144679518:144679845:-@chr8:144674817:144675063:-@chr8:144672815:144672908:-

@chr8:144671161:144672251:- | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| RPL17,

RPL17-C18ORF32 |

chr18:47018628:47018834:-@chr18:47017954|47018203:47017902:- | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| ENOX2 |

chrX:129790555:129790669:-@chrX:129771378|129771384:129771203:- | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| ARL6IP4,

RP11-197N18.2 |

chr12:123465676:123465813|123465846:+@chr12:123466142:123466426:+ | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| MRPL9 |

chr1:151735622:151735426|151735466:-@chr1:151734852:151734976:- | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| NOP56 |

chr20:2636580:2636680|2636860:+@chr20:2637047:2637195:+ | 0.20 | 0.24 |

| CPSF3L |

chr1:1249681:1249745:-@chr1:1249301|1249485:1249112:- | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| NA |

chr18:674406-674161:-@chr18:673076-670324:- | 0.20 | 0.27 |

| C10orf2 |

chr10:102747293:102747370|102749210:+@chr10:102749401:102749641:+ | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| LIME1,

ZGPAT |

chr20:62367133-62368064:+@chr20:62368886-62369000:+ | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| FLOT1 |

chr6:30698877-30698696:-@chr6:30698504-30698459:- | 0.22 | 0.29 |

| GYLTL1B |

chr11:45944329-45944515:+@chr11:45944609-45944718:+ | 0.39 | 0.29 |

| MIIP |

chr1:12089280-12089951:+@chr1:12090085-12090181:+ | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| SCMH1 |

chr1:41503034:41503213:-@chr1:41499655:41499774:-@chr1:41494256:41494398:- | 0.36 | 0.33 |

| TAOK2 |

chr16:29997586-29997825:+@chr16:29999680-29999719:+ | 0.48 | 0.34 |

| SRSF5 |

chr14:70235515-70235613:+@chr14:70235899-70237257:+ | 0.29 | 0.35 |

| PQLC3 |

chr2:11304330:11304387:+@chr2:11312051:11312171:+@chr2:11315094:11315135:

+@chr2:11317863:11318998:+ | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| APEX1 |

chr14:20923385-20923487:+@chr14:20923737-20923862:+ | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| PGAP2 |

chr11:3832480:3832654:+@chr11:3838662:3838765:+@chr11:3844139:3844223:

+@chr11:3845113:3845365:+ | 0.53 | 0.39 |

| ARL6IP4,

RP11-197N18.2 |

chr12:123465676:123465813:+@chr12:123466118|123466142:123466426:+ | 0.33 | 0.42 |

| TCEA2 |

chr20:62701118-62701174:+@chr20:62701613-62701767:+ | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| PGAP2 |

chr11:3832480:3832654:+@chr11:3838583:3838765:+@chr11:3844139:3844223:

+@chr11:3845113:3845365:+ | 0.62 | 0.48 |

| WDR19 |

chr4:39274600-39274681:+@chr4:39276428-39276578:+ | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| ZNF707 |

chr8:144766622:144766712:+@chr8:144766926:144767237:+@chr8:144771374:144771471:

+@chr8:144772227:144772293:+ | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| ARSA |

chr22:51066601:51066326|51066374:-@chr22:51065984:51066220:- | 0.42 | 0.59 |

| ZBTB8OS |

chr1:33116030:33116155:-@chr1:33100369:33100393:-@chr1:33099552:33099673:- | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| RGL2 |

chr6:33261843-33261811:-@chr6:33261693-33261572:- | 0.49 | 0.60 |

| OSBPL6 |

chr2:179204399:179204491:+@chr2:179209013:179209087:+@chr2:179213951:179214116:+ | 0.56 | 0.60 |

| WDR90 |

chr16:705773-705889:+@chr16:706302-706537:+ | 0.28 | 0.64 |

| TIMM9 |

chr14:58894110:58894232:-@chr14:58893772:58893960:-@chr14:58878625:58878689:-

@chr14:58877561:58877656:- | 0.50 | 0.68 |

To further investigate the biological processes

affected by those altered AS events, Gene Ontology (GO) functional

enrichment analysis was performed. GO terms such as DNA repair,

nucleotide-excision repair, DNA damage recognition, response to

reactive oxygen species, intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in

response to DNA damage were significantly enriched in the

MDA-MB-231-altered AS events (Fig.

2D). Biological processes such as DNA damage response, signal

transduction by p53 class mediator resulting in cell cycle arrest,

stress-activated MAPK cascade, signal transduction in response to

DNA damage were significantly enriched in T47D-altered alternative

splicing events (Fig. 2E). Taken

together, although the altered AS events from MDA-MB-231 and T47D

cells were different, DNA repair and DNA damage-related biological

processes were significantly enriched in both breast cancer cell

lines of differing types in the presence of macrophages.

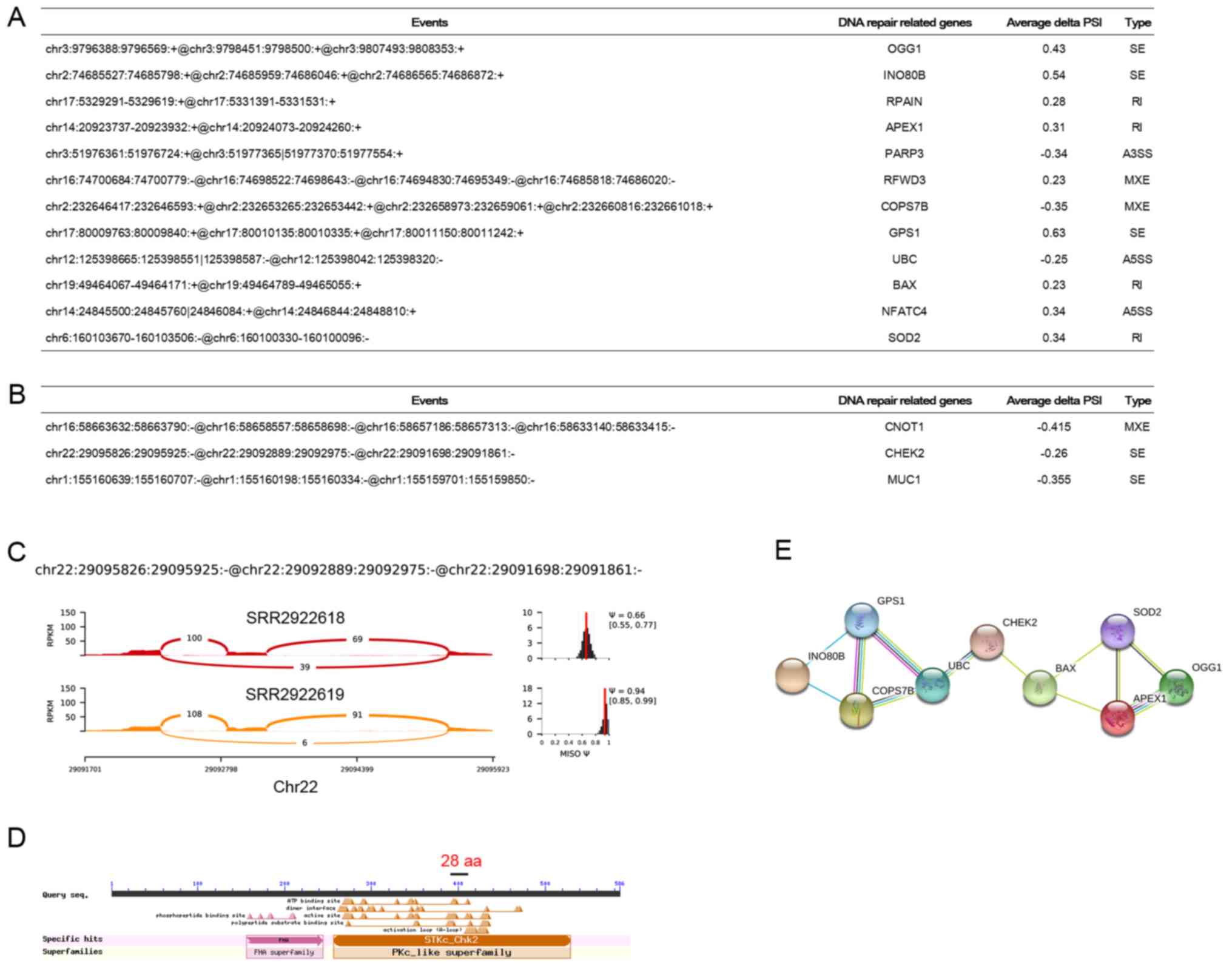

Then, we investigated how the DNA repair and DNA

damage-related AS events influence the function of corresponding

genes. Fig. 3A and B shows the DNA

repair and DNA damage-related AS events identified from MDA-MB-231

and T47D samples, respectively. Sashimi plots showed the AS events

‘chr22:29095826:29095925:-@chr22:29092889:29092975:-@chr22:29091698:29091861:-’

from gene Chek2 in T47D individual cultured sample

(SRR2922618) and co-cultured sample (SRR2922619) (Fig. 3C). CHEK2 is a cell cycle checkpoint

regulator and putative tumor suppressor (37) which contains a forkhead-associated

protein interaction domain essential for activation in response to

DNA damage and is rapidly phosphorylated in response to replication

blocks and DNA damage. CHEK2 has been shown to stabilize the

tumor-suppressor protein p53 (38,39),

leading to cell cycle arrest in G1 and it also interacts with and

phosphorylates BRCA1, allowing BRCA1 to restore survival after DNA

damage (40). According to our domain

analysis, we found that CHEK2 contains two crutial functional

domains (Fig. 3D): The first one is

STKc_Chk2, in which STKs can catalyze the transfer of a

γ-phosphoryl group from ATP to serine/threonine residues on protein

substrates, and the second one is FHA domain which is a putative

nuclear signaling domain. The skipped exon of Chek2 encodes 28 aa

which locates in the STKc_Chk2 domain (Fig. 3D). Thus the inclusion or exclusion of

the skippd exon changes the STKc_Chk2 domain of Chek2, which may

play an important role in the functional regulation of CHEK2.

Protein-protein interaction network analysis showed that these DNA

repair proteins have extensive interactions and CHEK2 may serve as

a hub gene in the network (Fig.

3E).

Altered AS events in macrophages by

co-culturing with MDA-MB-231 and T47D cells, respectively

As the differentiation of TAMs is largely regulated

by mediators secreted by tumor cells, it was ascertained how

different breast cancer cells ‘educate’ macrophages and regulate

the differentiation process at the AS level. Similarly, a total of

35,476 splicing events with values in at least 7 samples were

identified. Then, PCA and unsupervised clustering were used to

characterize the genetic distances among samples. From the PCA

result, it was revealed that macrophages individually cultured were

separated from their co-cultured states whereas the co-cultured

states of macrophage from T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were not able

to be separated (Fig. 4A), which is

also supported by the unsupervised clustering result (Fig. 4B). Then, we isolated those altered

splicing events by comparing the co-cultured samples with

individually cultured samples. A total of 115 and 118 significant

splicing events were identified in macrophages co-cultured with

MDA-MB-231 and T47D cells, respectively (Tables III and IV). There were 14 common splicing events in

the macrophages co-cultured with T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells

(P>0.2) which indicated that ER+ breast cancer cells

and TNBC cells have different influences on macrophages at the AS

level (Fig. 4C).

| Table III.Altered AS events in macrophages

co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells. |

Table III.

Altered AS events in macrophages

co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells.

| Gene | Events | ΔPSI

(SRR2922608_vs_SRR2922609) | ΔPSI

(SRR2922608_vs_SRR2922611) |

|---|

| WARS |

chr14:100841620:100841927:-@chr14:100840473:100840602:-@chr14:100840317:100840401:-

@chr14:100835424:100835595:- | −0.44 | −0.87 |

| WARS |

chr14:100841620:100841927:-@chr14:100840473:100840581:-@chr14:100840317:100840401:-

@chr14:100835424:100835595:- | −0.47 | −0.85 |

|

SLC25A19 |

chr17:73285170:73285453:-@chr17:73284583:73284672:-@chr17:73284469:73284542:-

@chr17:73282714:73282883:- | −0.44 | −0.54 |

| AKR1B1 |

chr7:134132813-134132732:-@chr7:134132133-134132050:- | −0.59 | −0.53 |

| NA |

chr3:148750159-148749988:-@chr3:148749150-148747904:- | −0.47 | −0.53 |

| WDR67 |

chr8:124153001:124153141:+@chr8:124154502:124154696:+@chr8:124156957:124157095:+ | −0.57 | −0.50 |

| AKR1B1 |

chr7:134132813:134132213|134132732:-@chr7:134132050:134132133:- | −0.58 | −0.49 |

| PLK3 |

chr1:45270011-45270173:+@chr1:45270322-45270451:+ | −0.35 | −0.47 |

| NA |

chr13:99852679:99853193:+@chr13:99883688:99883767:+@chr13:99890681:99890808:+ | −0.29 | −0.45 |

|

RABGAP1L |

chr1:174780970:174781098:+@chr1:174846530:174846743:+@chr1:174926594:174926686:+ | −0.44 | −0.44 |

| GBA2 |

chr9:35737936-35737745:-@chr9:35737601-35736864:- | −0.36 | −0.43 |

| AP1G2 |

chr14:24031497:24031624:-@chr14:24031171:24031275:-@chr14:24030721:24030844:- | −0.31 | −0.43 |

| IFFO1 |

chr12:6658922:6659062:-@chr12:6658642:6658650:-@chr12:6657834:6657991:- | −0.56 | −0.42 |

| HYAL2 |

chr3:50359204:50358797|50358999:-@chr3:50357000:50357966:- | −0.47 | −0.42 |

| PQLC3 |

chr2:11312051:11312171:+@chr2:11315094:11315135:+@chr2:11317863:11318998:+ | −0.31 | −0.42 |

| APEX1 |

chr14:20923385-20923487:+@chr14:20923737-20923862:+ | −0.46 | −0.39 |

| CKB |

chr14:103987600:103987771:-@chr14:103986839:103986929:-@chr14:103986459:103986648:- | −0.47 | −0.37 |

| RASSF7 |

chr11:560971:561033:+@chr11:561762:561892:+@chr11:562079:562776:+ | −0.42 | −0.37 |

| UGP2 |

chr2:64068098:64068366:+@chr2:64069193:64069338:+@chr2:64069673:64069733:

+@chr2:64083440:64083567:+ | −0.32 | −0.37 |

| UGP2 |

chr2:64068098:64068366:+@chr2:64069193:64069338:+@chr2:64082018:64082070:

+@chr2:64083440:64083567:+ | −0.38 | −0.36 |

| SPATA20 |

chr17:48624429:48624646:+@chr17:48625081:48625128:+@chr17:48625644:48625814:+ | −0.29 | −0.36 |

| UEVLD |

chr11:18557953:18558016:-@chr11:18555877:18556000:-@chr11:18552950:18554034:- | −0.41 | −0.35 |

| MX1 |

chr21:42797978:42798190:+@chr21:42799133:42799231:+@chr21:42799682:42799793:+ | −0.32 | −0.34 |

| SPHK1 |

chr17:74381532-74381735:+@chr17:74382024-74382218:+ | −0.32 | −0.34 |

| NIPBL |

chr5:37063892-37064121:+@chr5:37064629-37065921:+ | −0.38 | −0.33 |

| DYSF |

chr2:71738937:71739051:+@chr2:71740370:71740462:+@chr2:71740846:71741051:+ | −0.38 | −0.33 |

| PSTPIP1 |

chr15:77327849:77327904:+@chr15:77328143|77328152:77328276:+ | −0.31 | −0.33 |

| PXN |

chr12:120703420:120703574:-@chr12:120664642:120664920:-@chr12:120662446:120662530:-

@chr12:120661954:120662180:- | −0.30 | −0.33 |

| ZSWIM7 |

chr17:15881477-15881358:-@chr17:15881227-15881047:- | −0.25 | −0.33 |

| FAM21C |

chr10:46252460:46252587:+@chr10:46254763:46254849:+@chr10:46258836:46258937:+ | −0.24 | −0.33 |

| STXBP2 |

chr19:7707869:7707934:+@chr19:7708051:7708131:+@chr19:7709500:7709638:+ | −0.25 | −0.32 |

| NA |

chrX:30742218:30742298:+@chrX:30745583:30745669:+@chrX:30746849:30749577:+ | −0.42 | −0.31 |

| CEP350 |

chr1:180080132-180080330:+@chr1:180081572-180082515:+ | −0.35 | −0.31 |

| PCNP |

chr3:101293042:101293123:+@chr3:101298634|101298686:101298848:+ | −0.25 | −0.31 |

| ZSWIM7 |

chr17:15881477-15881358:-@chr17:15881227-15879875:- | −0.24 | −0.30 |

| DGUOK |

chr2:74173846:74174033:+@chr2:74177712:74177859:+@chr2:74185273:74185372:+ | −0.33 | −0.29 |

| NA |

chr12:9845424:9845527:+@chr12:9845630:9845711:+@chr12:9846421:9846544:+@chr12:9847356:9852151:+ | −0.50 | −0.28 |

| CKB |

chr14:103987600:103987771:-@chr14:103986806:103986929:-@chr14:103986459:103986648:- | −0.28 | −0.28 |

| C9,

DAB2 |

chr5:39388901:39388954:-@chr5:39388407:39388469:-@chr5:39382720:39383373:-@chr5:39381556:39381718:- | −0.21 | −0.28 |

| TBRG1 |

chr11:124495567:124495799:+@chr11:124496369:124496505:+@chr11:124496800:124496946:+ | −0.27 | −0.27 |

| NA |

chr12:9845424:9845527:+@chr12:9846421:9846544:+@chr12:9847356:9852151:+ | −0.45 | −0.26 |

| TNIP1 |

chr5:150460441:150460645:-@chr5:150444521:150444688:-@chr5:150443174:150443308:- | −0.31 | −0.26 |

| PARVG |

chr22:44568836:44569071:+@chr22:44577622:44577797:+@chr22:44579198:44579288:+ | −0.28 | −0.26 |

| NIN |

chr14:51226575:51227077:-@chr14:51223210:51225348:-@chr14:51221460:51221585:- | −0.22 | −0.26 |

| NA |

chr6:30181082:30181271:-@chr6:30172433:30172542:-@chr6:30168812:30168915:- | −0.25 | −0.25 |

| VPS33B |

chr15:91565384:91565833:-@chr15:91561035:91561115:-@chr15:91557614:91557663:- | −0.37 | −0.24 |

| HYAL2 |

chr3:50360084:50360281:-@chr3:50358797:50359204:-@chr3:50357000:50357966:- | −0.35 | −0.24 |

| YIPF1 |

chr1:54325729:54325826:-@chr1:54320674:54320724:-@chr1:54317392:54317943:- | −0.20 | −0.24 |

| UBE2D3 |

chr4:103748749:103749105:-@chr4:103747793|103748001:103747642:- | −0.26 | −0.23 |

|

PPP1R12A |

chr12:80201006:80201110:-@chr12:80199946:80200113:-@chr12:80199372:80199548:

-@chr12:80192274:80192364:- | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| TANK |

chr2:162016855:162016995|162016997:+@chr2:162036125:162036272:+ | −0.24 | −0.21 |

| NA |

chr12:15747871-15747991:+@chr12:15749024-15751265:+ | −0.23 | −0.21 |

|

C17orf76-AS1 |

chr17:16342641-16342728:+@chr17:16342895-16343567:+ | −0.23 | −0.21 |

| CPNE1,

NFS1 |

chr20:34252682:34252878:-@chr20:34246852:34246936:-@chr20:34220717:34220845:- | −0.30 | −0.20 |

| NA |

chr12:9845424:9845527|9846544:+@chr12:9847356:9852151:+ | −0.26 | −0.20 |

| TNIP1 |

chr5:150460441:150460645:-@chr5:150444521:150444692:-@chr5:150443174:150443308:- | −0.25 | −0.20 |

| CNN2 |

chr19:1032558:1032695:+@chr19:1036066:1036245:+@chr19:1036415:1036561:+ | −0.21 | −0.20 |

|

TNFRSF12A |

chr16:3070313:3070492:+@chr16:3071216:3071320:+@chr16:3071556:3071690:+ | −0.20 | −0.20 |

| CD44 |

chr11:35211382:35211612:+@chr11:35219668:35219793:+@chr11:35232793:35232996:

+@chr11:35236399:35236461:+ | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| GK |

chrX:30671476:30671732:+@chrX:30683628:30683701:+@chrX:30695492:30695569:+ | 0.40 | 0.20 |

| UNC45A |

chr15:91478515:91478560|91478605:+@chr15:91478774:91478935:+ | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| 43166 |

chr2:160615737:160615846|160615869:+@chr2:160619391:160619504:+ | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| TBC1D15 |

chr12:72287002:72287104:+@chr12:72288105:72288155:+@chr12:72288466:72288663:+ | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| CD44 |

chr11:35211382:35211612:+@chr11:35226059:35226187:+@chr11:35227659:35227790:+ | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| APLP2 |

chr11:129992200:129992408:+@chr11:129993507:129993674:+@chr11:129996595:129996725:+ | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| NUDT22 |

chr11:63993762-63993899:+@chr11:63994107-63994604:+ | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| DCAF6 |

chr1:167973771:167974031:+@chr1:167992226:167992285:+@chr1:168007609:168007726:+ | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| CBFB |

chr16:67116116:67116211|67116242:+@chr16:67132613:67134958:+ | 0.20 | 0.23 |

| CD44 |

chr11:35211382:35211612:+@chr11:35229652:35229756:+@chr11:35232793:35232996:+@chr11:

35236399:35236461:+ | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| DPP7 |

chr9:140009170-140009099:-@chr9:140009028-140008915:- | 0.28 | 0.23 |

| ARGLU1 |

chr13:107212005-107211780:-@chr13:107209479-107209396:- | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| BAG6 |

chr6:31620477:31620177|31620201:-@chr6:31619433:31619553:- | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| PLD1 |

chr3:171405161:171405374:-@chr3:171404475:171404588:-@chr3:171395356:171395484:- | 0.36 | 0.24 |

| RFFL,

RAD51L3-RFFL |

chr17:33353393:33353580:-@chr17:33348390:33348800:-@chr17:33344542:33344625:- | 0.37 | 0.24 |

| NCOR2 |

chr12:124812179:124811955|124812093:-@chr12:124810737:124810916:- | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| CELF2 |

chr10:11370889-11371060:+@chr10:11372419-11374591:+ | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| CELF2 |

chr10:11370889-11371060:+@chr10:11372419-11374605:+ | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| CD44 |

chr11:35211382:35211612:+@chr11:35231512:35231601:+@chr11:35232793:35232996:

+@chr11:35236399:35236461:+ | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| CELF2 |

chr10:11370889-11371060:+@chr10:11372419-11376357:+ | 0.34 | 0.27 |

|

RP11-458D21.5 |

chr1:145281369:145281704:+@chr1:145290429:145290511:+@chr1:145293114:145293272:

+@chr1:145293371:145293580:+ | 0.34 | 0.27 |

| RNASE1 |

chr14:21270956:21271036:-@chr14:21270408:21270478:-@chr14:21269515:21270252:- | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| TMX2-CTNND1,

RP11-691N7.6,CTNND1 |

chr11:57529234:57529518|57529591:+@chr11:57556509:57556627:+ | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| CD44 |

chr11:35211382:35211612:+@chr11:35219695:35219793:+@chr11:35232793:35232996:

+@chr11:35236399:35236461:+ | 0.28 | 0.29 |

| PGAP2 |

chr11:3832480:3832654:+@chr11:3838662:3838765:+@chr11:3845113:3845365:+ | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| SRRM1 |

chr1:24989151:24989295:+@chr1:24989674:24989715:+@chr1:24993306:24993416:+ | 0.34 | 0.29 |

| NSUN4 |

chr1:46810473:46810816:+@chr1:46812593:46812747:+@chr1:46818540:46818700:+ | 0.33 | 0.30 |

| CHFR |

chr12:133447310:133447369:-@chr12:133446205:133446384:-@chr12:133438053:133438220:- | 0.51 | 0.30 |

| SNX17 |

chr2:27593389:27593673:+@chr2:27594136:27594174:+@chr2:27595490:27595607:+ | 0.23 | 0.31 |

| ITGA6 |

chr2:173362703:173362828:+@chr2:173366500:173366629:+@chr2:173368819:173371181:+ | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| CHFR |

chr12:133447310:133447369:-@chr12:133446205:133446420:-@chr12:133438053:133438220:- | 0.46 | 0.32 |

| NA |

chr14:20923290:20923497|20923548:+@chr14:20923737:20923862:+ | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| PNPLA8 |

chr7:108166473:108166762:-@chr7:108161920:108161965:-@chr7:108154880:108156018:- | 0.4 | 0.34 |

| GOLIM4 |

chr3:167759180:167759262:-@chr3:167758574:167758657:-@chr3:167754624:167754782:- | 0.29 | 0.35 |

| LILRA2,

LILRB1 |

chr19:55087274:55087576:+@chr19:55088932:55089190:+@chr19:55098477:55098527:

+@chr19:55098668:55099027:+ | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| FLNB |

chr3:58124009:58124256:+@chr3:58127585:58127656:+@chr3:58128377:58128479:+ | 0.41 | 0.36 |

| CD44 |

chr11:35211382:35211612:+@chr11:35219695:35219793:+@chr11:35226059:35226187:+

@chr11:35229652:35229753:+ | 0.47 | 0.36 |

| STX2 |

chr12:131283070:131283180:-@chr12:131280540:131280665:-@chr12:131274145:131276522:- | 0.29 | 0.38 |

| POLD1 |

chr19:50910584:50910672:+@chr19:50911964|50912042:50912158:+ | 0.37 | 0.38 |

| NA |

chr13:99852679:99853193:+@chr13:99853683:99853821:+@chr13:99883688:99883767:

+@chr13:99890681:99890808:+ | 0.46 | 0.41 |

| AFTPH |

chr2:64800080:64800202:+@chr2:64806620:64806680:+@chr2:64812556:64812679:+ | 0.52 | 0.41 |

| NA |

chr1:120930039:120930293:-@chr1:120928331:120928615:-@chr1:120926128:120927417:- | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| AC069513.3,

SDHAP2 |

chr3:195389442:195389604:+@chr3:195390495:195390703:+@chr3:195390957:195391121:+ | 0.34 | 0.44 |

| ELMOD3 |

chr2:85617261-85617388:+@chr2:85617883-85618875:+ | 0.43 | 0.44 |

| ELMOD3 |

chr2:85617261-85617388:+@chr2:85617883-85618871:+ | 0.43 | 0.45 |

| FBXO38 |

chr5:147805085:147805264:+@chr5:147806776:147807285:+@chr5:147812987:147813087:+ | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| FBXO38 |

chr5:147805085:147805264:+@chr5:147806776:147807510:+@chr5:147812987:147813087:+ | 0.32 | 0.48 |

|

AC024560.3 |

chr3:197350091:197350253:-@chr3:197349058:197349201:-@chr3:197348575:197348739:- | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| NBPF14 |

chr1:148011680:148011788:-@chr1:148010884:148011056:-@chr1:148009344:148009516:

-@chr1:148008573:148008624:- | 0.20 | 0.51 |

| NQO2 |

chr6:3000067:3000319:+@chr6:3002284:3002520:+@chr6:3003903:3004023:+ | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| AFTPH |

chr2:64800080:64800202:+@chr2:64806620:64808407:+@chr2:64812556:64812679:+ | 0.57 | 0.55 |

| IFT88 |

chr13:21141208:21141395:+@chr13:21141809:21142136:+@chr13:21148519:21148614:+ | 0.58 | 0.59 |

| NQO2 |

chr6:3000067:3000319:+@chr6:3003903:3004023:+@chr6:3004729:3004885:+@chr6:3006702:3006793:+ | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| HPCAL1 |

chr2:10536961:10537046:+@chr2:10546391:10546487:+@chr2:10548688:10548860:

+@chr2:10559860:10560261:+ | 0.44 | 0.62 |

|

SLC25A19 |

chr17:73284672:73284469|73284583:-@chr17:73282714:73282883:- | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| PDE1B |

chr12:54964025-54964141:+@chr12:54966385-54966525:+ | 0.63 | 0.63 |

|

TRIM39-RPP21 |

chr6:30312906:30313005:+@chr6:30313075:30313175:+@chr6:30313268:30313350:

+@chr6:30314209:30314334:+ | 0.45 | 0.67 |

| PTGS1 |

chr9:125133465:125133551:+@chr9:125133892:125134113:+@chr9:125140178:125140294:+ | 0.77 | 0.73 |

| NA |

chr17:26646121:26646391:+@chr17:26652529:26652673:+@chr17:26653560:26655711:+ | 0.61 | 0.74 |

| Table IV.Altered AS events in macrophages

co-cultured with T47D cells. |

Table IV.

Altered AS events in macrophages

co-cultured with T47D cells.

| Gene | Event | ΔPSI

(SRR2922612_vs_SRR2922610) | ΔPSI

(SRR2922612_vs_SRR2922614) |

|---|

| IL6 |

chr7:22766766:22766900:+@chr7:22767132:22767253:+@chr7:22768312:22768425:+ | −0.68 | −0.55 |

| CKB |

chr14:103987600:103987771:-@chr14:103986839:103986929:-@chr14:103986459:103986648:- | −0.5 | −0.55 |

| SUCO |

chr1:172520652:172520766:+@chr1:172522400:172522510:+@chr1:172525009:172525163:+ | −0.51 | −0.52 |

| SEP3 |

chr22:42390625-42390718:+@chr22:42392906-42394225:+ | −0.47 | −0.49 |

| ANKRD49 |

chr11:94229770:94229994|94230243:+@chr11:94231237:94232744:+ | −0.37 | −0.47 |

| NA |

chr14:70883617:70883807:-@chr14:70855187:70855323:-@chr14:70842393:70842488:- | −0.46 | −0.46 |

| IQSEC2 |

chrX:53310678:53310796:-@chrX:53308746:53308841:-@chrX:53295506:53296246:- | −0.46 | −0.46 |

| SP110 |

chr2:231084589:231084827:-@chr2:231081496:231081536:-@chr2:231079665:231079833:- | −0.51 | −0.44 |

| ANXA2 |

chr15:60688350:60688626:-@chr15:60685237:60685639:-@chr15:60678227:60678285:- | −0.46 | −0.44 |

| DCTD |

chr4:183837692:183837439|183837572:-@chr4:183836614:183836728:- | −0.35 | −0.44 |

| MGA |

chr15:42032251:42032401:+@chr15:42034744:42035370:+@chr15:42040835:42041125:+ | −0.44 | −0.43 |

|

C17orf76-AS1 |

chr17:16342641-16342728:+@chr17:16342895-16343567:+ | −0.4 | −0.43 |

| KIAA0226L,

PPP1R2P4 |

chr13:46961269:46961635:-@chr13:46952025:46952140:-@chr13:46946076:46946732:- | −0.36 | −0.43 |

| HNRNPC |

chr14:21737457:21737638:-@chr14:21731495|21731741:21731470:- | −0.36 | −0.43 |

| EXOC7 |

chr17:74087224:74087316:-@chr17:74086410:74086562:-@chr17:74085256:74085401:- | −0.36 | −0.42 |

| NA |

chr2:3605976:3606588:+@chr2:3606994|3607038:3607319:+ | −0.48 | −0.41 |

| ARIH2 |

chr3:48956254:48956431:+@chr3:48960181:48960244:+@chr3:48962151:48962272:+ | −0.31 | −0.41 |

| NA |

chr12:15747871-15747991:+@chr12:15749024-15751265:+ | −0.26 | −0.41 |

| RPS15A,

RP11-1035H13.3 |

chr16:18801656:18801566|18801632:-@chr16:18800303:18800440:- | −0.47 | −0.4 |

| RP11-691N7.6,

CTNND1 |

chr11:57529234:57529518:+@chr11:57556509:57556627:+@chr11:57558857:57559145:+ | −0.47 | −0.39 |

| UGP2 |

chr2:64068098:64068366:+@chr2:64069193:64069338:+@chr2:64069673:64069733:

+@chr2:64083440:64083567:+ | −0.24 | −0.39 |

| EXOC7 |

chr17:74087224:74087316:-@chr17:74086410:74086478:-@chr17:74085256:74085401:- | −0.35 | −0.36 |

| SLC41A2 |

chr12:105352071:105351866|105351968:-@chr12:105321875:105322472:- | −0.46 | −0.34 |

| NA |

chrX:30742218:30742298:+@chrX:30745583:30745669:+@chrX:30746849:30749577:+ | −0.4 | −0.34 |

| NHLRC3 |

chr13:39613701:39613848:+@chr13:39616242:39616442:+@chr13:39618227:39618318:+ | −0.35 | −0.34 |

| IL6 |

chr7:22766766:22766900:+@chr7:22767063:22767253:+@chr7:22768312:22768425:+ | −0.34 | −0.34 |

| ST7L |

chr1:113162266:113162405:-@chr1:113161531:113161761:-@chr1:113159435:113159517:

-@chr1:113153463:113153625:- | −0.5 | −0.33 |

| UGP2 |

chr2:64068098:64068366:+@chr2:64069193:64069338:+@chr2:64082018:64082070:

+@chr2:64083440:64083567:+ | −0.22 | −0.33 |

|

RABGAP1L |

chr1:174780970:174781098:+@chr1:174846530:174846743:+@chr1:174926594:174926686:+ | −0.46 | −0.32 |

| WASH4P |

chr16:67427-67291:-@chr16:67051-66916:- | −0.27 | −0.32 |

| ZCCHC6 |

chr9:88916191:88916516:-@chr9:88913682:88913745:-@chr9:88902648:88903659:- | −0.34 | −0.31 |

| USP8 |

chr15:50773678:50774262:+@chr15:50776472:50776558:+@chr15:50781998:50782078:+ | −0.31 | −0.31 |

| NUBP2 |

chr16:1836538:1836656|1836956:+@chr16:1837678:1837832:+ | −0.27 | −0.31 |

| TMEM19 |

chr12:72094612-72094805:+@chr12:72097757-72097836:+ | −0.36 | −0.3 |

| HNRNPH1 |

chr5:179047893:179048036:-@chr5:179046270:179046361:-@chr5:179045146:179045324:- | −0.42 | −0.29 |

| SBF1 |

chr22:50897684:50897821:-@chr22:50895463:50895540:-@chr22:50894921:50895102:- | −0.35 | −0.29 |

| BCL2L13 |

chr22:18171752:18171908:+@chr22:18178907:18178976:+@chr22:18185009:18185152:+ | −0.32 | −0.29 |

| YWHAZ |

chr8:101965078:101965221:-@chr8:101964157:101964353:-@chr8:101960824:101961128:- | −0.3 | −0.29 |

| TCOF1 |

chr5:149769450:149769586:+@chr5:149771107:149771220:+@chr5:149771520:149771739:+ | −0.25 | −0.29 |

| CHTOP |

chr1:153610771:153610924:+@chr1:153614719:153614905:+@chr1:153617540:153618782:+ | −0.34 | −0.28 |

| GIT2 |

chr12:110385061:110385309:-@chr12:110383065:110383154:-@chr12:110376970:110377052:- | −0.32 | −0.28 |

| PCM1 |

chr8:17838100:17838264:+@chr8:17840742:17840798:+@chr8:17842956:17843128:+ | −0.27 | −0.28 |

| SIGLEC11,

NUP62 |

chr19:50432583:50432988:-@chr19:50431072|50431105:50430951:- | −0.21 | −0.28 |

| ANKRD12,

RP11-21J18.1 |

chr18:9195549:9195696:+@chr18:9204474:9204542:+@chr18:9208655:9208801:+ | −0.28 | −0.27 |

| AC092755.4,

BNIP2 |

chr15:59961091:59961189:-@chr15:59960302:59960337:-@chr15:59955062:59956319:- | −0.25 | −0.27 |

| CNN2 |

chr19:1032558:1032695:+@chr19:1036066:1036245:+@chr19:1036415:1036561:+ | −0.25 | −0.27 |

| NSUN4 |

chr1:46805849:46806591:+@chr1:46806995:46807169:+@chr1:46810473:46810816:+ | −0.25 | −0.27 |

| NUBP2 |

chr16:1836538:1836656:+@chr16:1836739:1836956:+@chr16:1837678:1837832:+ | −0.25 | −0.27 |

| SRPK2 |

chr7:104767440:104767509:-@chr7:104766695:104766787:-@chr7:104766229:104766321:

-@chr7:104756823:104758469:- | −0.42 | −0.26 |

| ITGAM |

chr16:31308835:31308975:+@chr16:31309063|31309066:31309275:+ | −0.33 | −0.26 |

| OSBPL3 |

chr7:24874355:24873706|24874105:-@chr7:24870387:24870524:- | −0.32 | −0.26 |

| YWHAZ |

chr8:101965078:101965221:-@chr8:101964157:101964536:-@chr8:101960824:101961128:- | −0.26 | −0.26 |

|

C17orf76-AS1 |

chr17:16342641-16342728:+@chr17:16342895-16343017:+ | −0.2 | −0.26 |

| PXN |

chr12:120703420:120703574:-@chr12:120664642:120664920:-@chr12:120662446:120662530:

-@chr12:120661954:120662180:- | −0.28 | −0.25 |

| NA |

chr22:50964675:50964905:-@chr22:50964430:50964585:-@chr22:50961997:50962853:- | −0.53 | −0.24 |

| ANXA2 |

chr15:60690142:60690185:-@chr15:60688350:60688626:-@chr15:60685237:60685639:

-@chr15:60678227:60678285:- | −0.27 | −0.24 |

| DFFA |

chr1:10523266-10523115:-@chr1:10521759-10520603:- | −0.23 | −0.24 |

| NA |

chr1:171673674-171673527:-@chr1:171671224-171669296:- | −0.29 | −0.22 |

| CKB |

chr14:103987600:103987771:-@chr14:103986806:103986929:-@chr14:103986459:103986648:- | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| MAPK7 |

chr17:19283921-19284999:+@chr17:19285094-19285779:+ | −0.22 | −0.22 |

| SLC11A2 |

chr12:51375586-51375422:-@chr12:51373841-51373566:- | −0.39 | −0.21 |

| MPZL1 |

chr1:167742473:167742605:+@chr1:167745301:167745403:+@chr1:167757057:167761156:+ | −0.25 | −0.21 |

| ABI1 |

chr10:27054147:27054247:-@chr10:27047991:27048164:-@chr10:27040527:27040712:- | −0.33 | −0.2 |

| ABI1 |

chr10:27054147:27054247:-@chr10:27047991:27048167:-@chr10:27040527:27040712:- | −0.32 | −0.2 |

| NT5C2 |

chr10:104899163:104899236:-@chr10:104871502:104871562:-@chr10:104866346:104866463:- | 0.22 | 0.2 |

| ILK |

chr11:6624964:6625052:+@chr11:6625410|6625456:6625590:+ | 0.29 | 0.2 |

| SRRT |

chr7:100479674:100479862:+@chr7:100480386:100480711:+@chr7:100481691:100481860:+ | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| MFSD10 |

chr4:2933880-2933772:-@chr4:2933663-2933552:- | 0.2 | 0.22 |

| ACTR6 |

chr12:100594555:100594697|100594838:+@chr12:100598718:100598835:+ | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| NCOR1 |

chr17:16118676:16118874:-@chr17:16101915:16102033:-@chr17:16097776:16097953:- | 0.33 | 0.22 |

| TXNRD1 |

chr12:104680460:104680887:+@chr12:104682711:104682818:+@chr12:104705068:104705190:

+@chr12:104707023:104707095:+ | 0.39 | 0.22 |

| LILRA2,

LILRB1 |

chr19:55087274:55087576:+@chr19:55088932:55089190:+@chr19:55098477:55098527:

+@chr19:55098668:55099027:+ | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| RPL17,

RPL17-C18orf32 |

chr18:47018628:47018834:-@chr18:47017954|47018203:47017902:- | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| TXNRD1 |

chr12:104680727:104680887|104681124:+@chr12:104682709:104682818:+ | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| NA |

chr1:44679125-44679199:+@chr1:44679381-44679530:+ | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| MSRB1 |

chr16:1991406:1990779|1991258:-@chr16:1988234:1989144:- | 0.31 | 0.24 |

| WARS |

chr14:100842597:100842680:-@chr14:100841620:100841883:-@chr14:100828045:100828258:- | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| NA |

chr10:105156166:105156270:-@chr10:105155503:105155789:-@chr10:105153956:105154151:

-@chr10:105152128:105152223:- | −0.37 | 0.25 |

| IRF7 |

chr11:615647-615345:-@chr11:615259-615097:- | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| RREB1 |

chr6:7229230:7232140:+@chr6:7240671:7240835:+@chr6:7246657:7247454:+ | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| DCAF6 |

chr1:167973771:167974031:+@chr1:167992226:167992285:+@chr1:168007609:168007726:+ | 0.23 | 0.26 |

| PXN |

chr12:120663712:120663872:-@chr12:120662446:120662530:-@chr12:120661954:120662180:- | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| SRSF7 |

chr2:38976671:38976847:-@chr2:38976040:38976488:-@chr2:38975721:38975795:- | 0.37 | 0.27 |

| MLL3 |

chr7:151855948:151856157:-@chr7:151854846:151855010:-@chr7:151853290:151853431:- | 0.45 | 0.27 |

| WARS |

chr14:100842597:100842680:-@chr14:100841620:100841883:-@chr14:100835424:100835595:- | 0.24 | 0.28 |

| FBXO38 |

chr5:147805085:147805264:+@chr5:147806776:147807510:+@chr5:147812987:147813087:+ | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| NT5C3 |

chr7:33102180:33102409:-@chr7:33075546:33075600:-@chr7:33066429:33066527:- | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| NCOR2 |

chr12:124812179:124811955|124812093:-@chr12:124810737:124810916:- | 0.37 | 0.28 |

| NA |

chr6:30181082:30181271:-@chr6:30168812:30168915:-@chr6:30166443:30166930:- | 0.3 | 0.31 |

| SRSF6 |

chr20:42087001:42087149:+@chr20:42087793:42088060:+@chr20:42088411:42088535:+ | 0.33 | 0.31 |

| C10orf2 |

chr10:102750626:102750767|102750811:+@chr10:102752947:102754158:+ | 0.27 | 0.32 |

| DYRK1B |

chr19:40317925:40318065:-@chr19:40317507|40317627:40317312:- | 0.38 | 0.32 |

| HNRNPH1 |

chr5:179050670:179050596|179050637:-@chr5:179050038:179050165:- | 0.38 | 0.33 |

| ANKZF1 |

chr2:220098855-220099010:+@chr2:220099548-220100034:+ | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| ARIH2 |

chr3:48956254:48956431:+@chr3:48960181:48960244:+@chr3:48962151:48962272:

+@chr3:48982569:48982614:+ | 0.3 | 0.36 |

| CAMTA2 |

chr17:4886052:4886187:-@chr17:4885384:4885522:-@chr17:4884973:4885126:- | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| MRRF |

chr9:125027741:125027824|125028059:+@chr9:125033143:125033354:+ | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| SETMAR |

chr3:4344988:4345210:+@chr3:4354582:4354913:+@chr3:4355331:4355445:+ | 0.42 | 0.36 |

| RREB1 |

chr6:7229230:7232140:+@chr6:7240671:7240835:+@chr6:7248744:7252213:+ | 0.6 | 0.36 |

| NA |

chr1:207095163:207095378:-@chr1:207087104:207087439:-@chr1:207086274:207086387:- | 0.43 | 0.39 |

|

RP11-315D16.2 |

chr15:68497583:68498448:-@chr15:68491879:68492019:-@chr15:68489778:68489966:- | 0.48 | 0.39 |

| NA |

chr18:32820994:32821073:+@chr18:32822355:32822848:+@chr18:32823116:32823257:+ | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| FOPNL |

chr16:15982415:15982447:-@chr16:15977865:15978062:-@chr16:15973661:15973745:

-@chr16:15967348:15967484:- | 0.38 | 0.41 |

| AAMDC |

chr11:77532208:77532287:+@chr11:77552065:77552106:+@chr11:77553525:77553674:+ | 0.47 | 0.41 |

| NA |

chrX:1718085:1718325:+@chrX:1719031:1719100:+@chrX:1719552:1721411:+ | 0.48 | 0.41 |

| TCTN1 |

chr12:111078188:111078322:+@chr12:111078829:111078954:+@chr12:111082772:111082934:

+@chr12:111085016:111085141:+ | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| MON1A |

chr3:49950653:49950792:-@chr3:49948959:49949444:-@chr3:49947552:49948317:- | 0.47 | 0.44 |

| TMBIM6 |

chr12:50135340:50135394:+@chr12:50135740:50135898:+@chr12:50138196:50138325:

+@chr12:50146247:50146332:+ | 0.43 | 0.45 |

| NA |

chr5:80597402:80597489|80597517:+@chr5:80604380:80604530:+ | 0.48 | 0.45 |

| TM2D1 |

chr1:62160369:62160442:-@chr1:62152464:62152593:-@chr1:62149089:62149218:- | 0.42 | 0.46 |

| NA |

chr22:18165980:18166087:+@chr22:18185009:18185152:+@chr22:18209443:18213621:+ | 0.25 | 0.47 |

| CHD8 |

chr14:21868572:21868771:-@chr14:21868466|21868490:21868310:- | 0.35 | 0.47 |

| NA |

chr22:18171752:18171908:+@chr22:18185009:18185152:+@chr22:18209443:18213621:+ | 0.23 | 0.48 |

| SLA |

chr8:134114644:134114786:-@chr8:134087098:134087375:-@chr8:134072345:134072445:

-@chr8:134063061:134063160:- | 0.51 | 0.62 |

| ARIH2 |

chr3:48956254:48956431:+@chr3:48962151:48962272:+@chr3:48964895:48965246:+ | 0.36 | 0.64 |

Similarly, GO functional enrichment analysis was

applied to investigate the biological processes affected by those

altered AS events. GO terms such as signal transduction,

cell-matrix adhesion, protein transport, brain development were

significantly enriched in the macrophages co-cultured with

MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4D). Terms

such as RNA export from the nucleus, regulation of angiogenesis,

positive regulation of transcription, DNA-templated, mRNA export

from the nucleus, negative regulation of apoptotic process were

significantly enriched in the macrophages co-cultured with the T47D

cells (Fig. 4E). Briefly, protein

transport-related processes were altered by co-culturing

macrophages with the MDA-MB-231 cells and RNA processing biological

processes were affected by co-culturing macrophages with the T47D

cells.

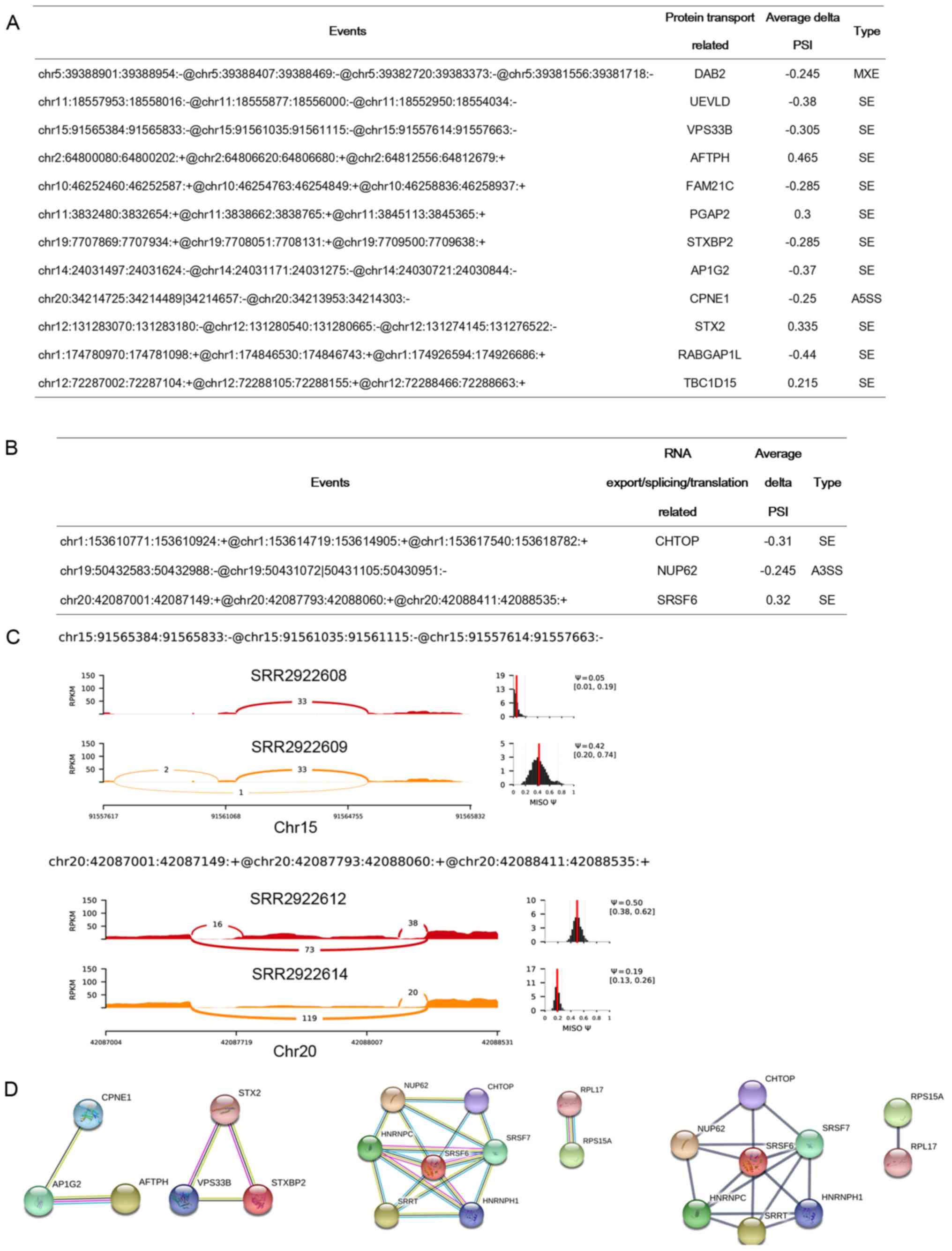

The RNA processing and protein transport-related AS

events derived from the macrophages co-cultured with the MDA-MB-231

(Fig. 5A) and T47D (Fig. 5B) cells were further analyzed.

Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 33B (VPS33B) is a Sec1

familiy protein involved in vesicle transport which mediates

protein sorting and plays an important role in segregation of

intracellular molecules into distinct organelles (41,42). As

known, the induced inflammatory responses by microbial ligands is

influenced by internalization of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), thus,

endosomal maturation in clearing receptors terminates inflammatory

responses. Akbar et al found that Vps33B proteins play

critical roles in the maturation of phagosomes and endosomes in

Drosophila and mammals and therefore affect the process of

maturation of macrophages (43).

Sashimi plot showed the AS event

‘chr15:91565384:91565833:-@chr15:91561035:91561115:-@chr15:91557614:91557663:-’

of gene VPS33B. The exon was largely excluded from the

macrophages co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5C), which may influence the protein

function and further the maturation process of macrophages. The

protein encoded by SRSF6 belongs to the splicing factor SR

and may play a role in the determination of alternative splicing.

Boisson et al demonstrated that SRSF6 regulate the AS of the

IKBKG gene, which accounts for NF-κB activation and further

immune response activation (44).

Here, we showed that SRSF6 itself is regulated by AS.

Specifically, the event

‘chr20:42087001:42087149:+@chr20:42087793:42088060:+@chr20:42088411:42088535:+’

of SRSF6 was significantly included after coculturing macrophages

with T47D cells (Fig. 5C). PPI

analysis showed that protein transport-related proteins CPNE1,

AP1G2, AFTPH, STX2, VPS33B and STXBP2 were interacted intimately

(Fig. 5D). In the interaction network

of RNA processing proteins, SRSF6 has extensive interactions with

another 6 proteins and may serve as the hub protein in the network

(Fig. 5D). These results further

indicate that AS events containing genes including Vps33B

and SRSF6 may play important roles in the maturation

processes of macrophages.

Sequence feature characterization of

the altered skip exons

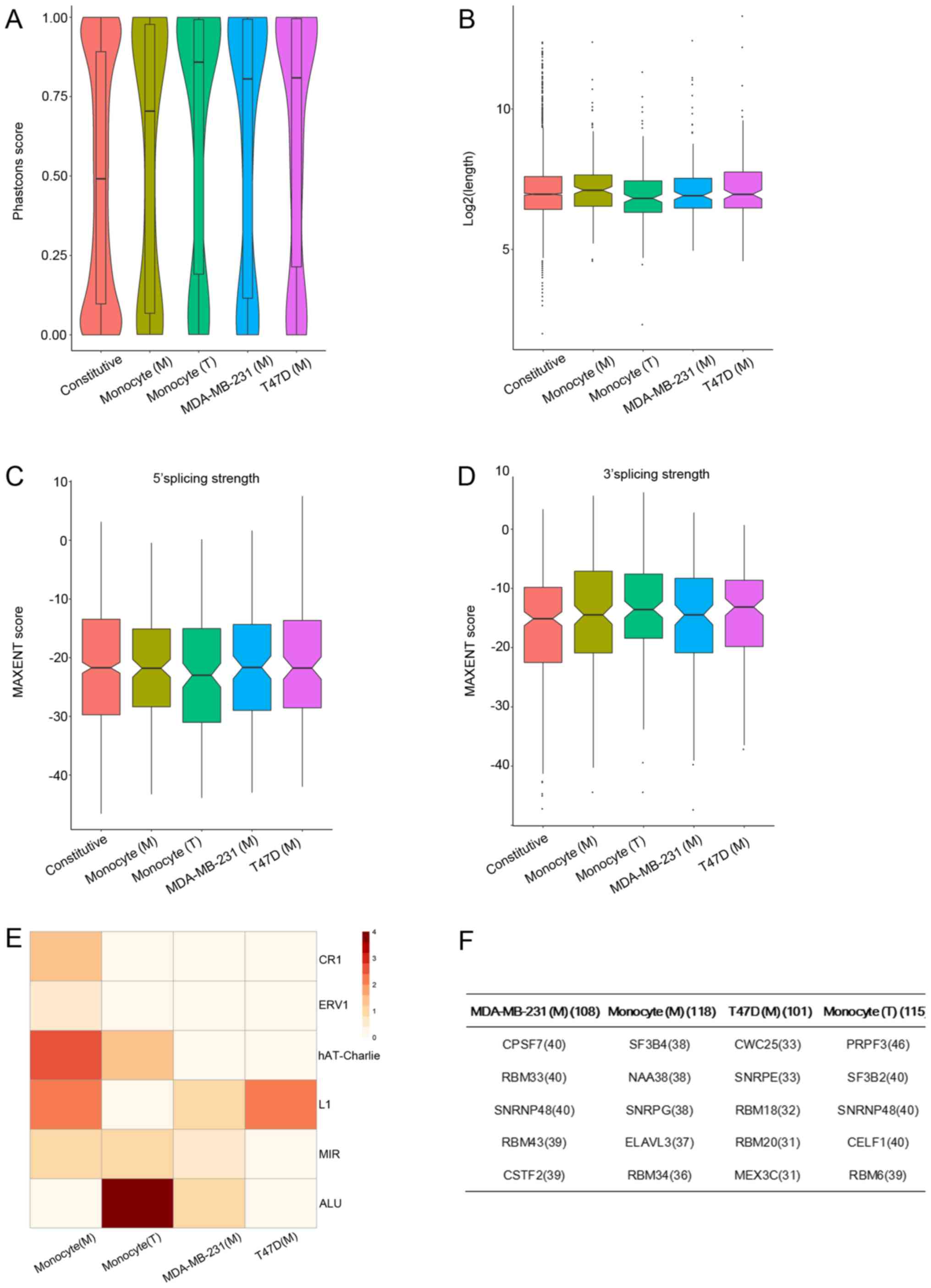

To investigate whether the altered AS events in

different treatments had distinct properties, we first measured the

degree of evolutionary conservation of skip exon sequences across

placental mammals. Unexpectedly, all the altered skip exons in

different treatments showed a higher degree of sequence

conservation equivalent compared to that of constitutive exons

(Fig. 6A). Altered skip exons in the

macrophages co-cultured with T47D cells showed highest evolutionary

conservation, whereas macrophages co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells

showed the lowest. There were no significant differences in skip

exon length among the different treatments (Wilcoxon signed-rank

test, P>0.05; Fig. 6B). Splicing

site strength analysis showed there were no significant differences

in splicing strength between constitutive skip and altered skip

exons and no significant differences among the different treatments

(Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P>0.05; Fig. 6C and D). Repetitive elements such as

Alu are known to be stochastically exonized (45), and we found Alu elements were more

enriched within skip exons in the macrophages cocultured with the

T47D cells, were fewer in skip exons of macrophages cocultured with

the MDA-MB-231 cells, and were almost absent from skip exons of

MDA-MB-231 co-cultured with macrophages and T47D co-cultured with

macrophages (Fisher's exact test; Fig.

6E). We conclude that altered skip exons of macrophages

cocultured with T47D cells were mostly enriched with Alu element

and had highest evolutionary conservation.

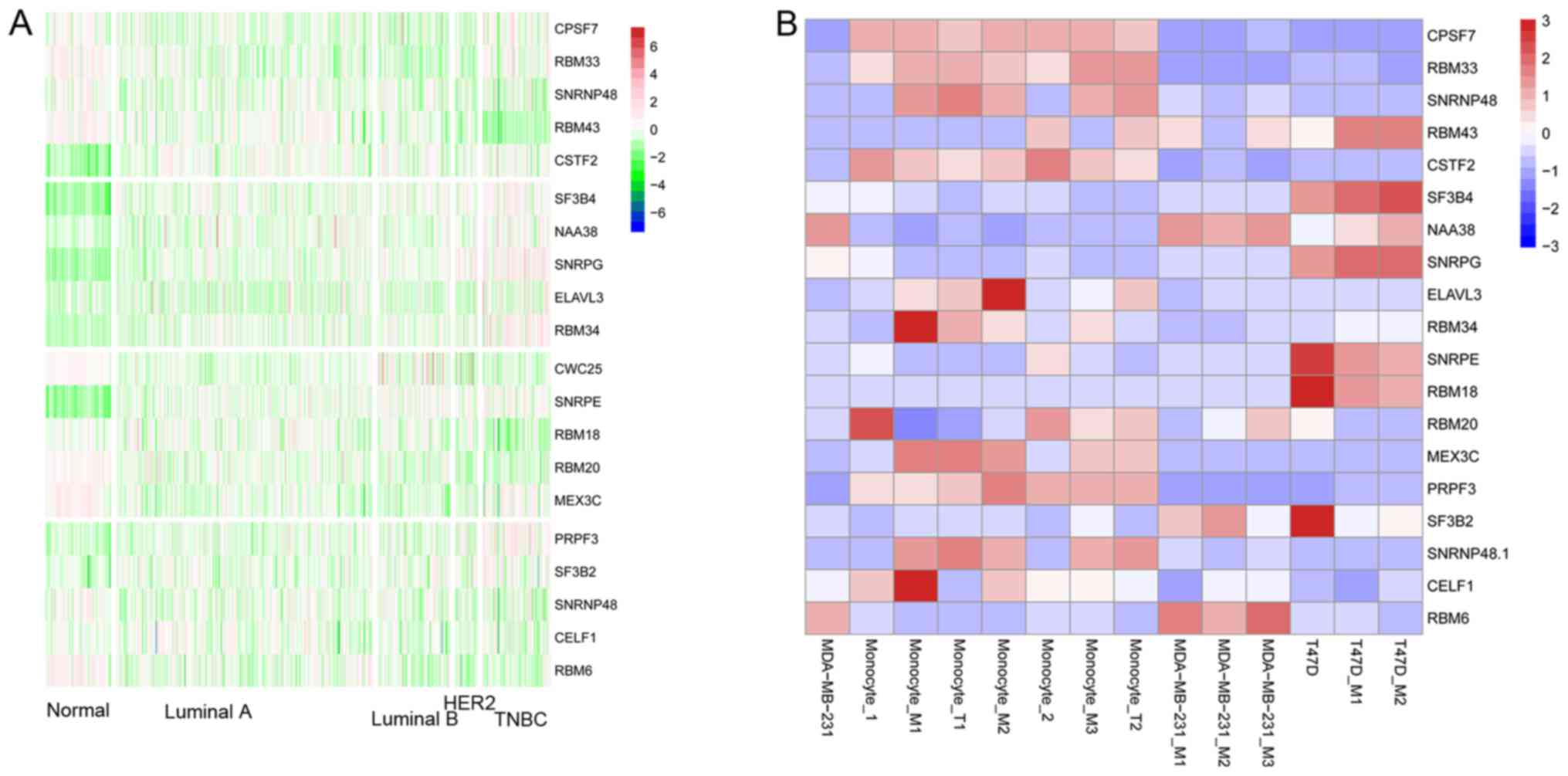

Finally, the splicing factors responsible for the AS

events in the different cells and treatments were determined. Here,

we calculated the associations between splicing factor expression

and the PSI values across the 14 samples. The top 5 splicing

factors which possessed the most associated splicing events in each

of the 4 cell conditions are shown in Fig. 6F. In the MDA-MB-231 cells co-cultured

with macrophages, CPSF7, RBM33, SNRNP48, RBM43 and

CSTF2 were the top five. Akman et al confirmed that

CSTF2 is a major regulator of 3′UTR shortening in TNBC and

contributes to the proliferation phenotype (46). In T47D cells co-cultured with

macrophages, CWC25, SNRPE, RBM18, RBM20 and MEX3C

were the top five. Meanwhile, in the macrophages co-cultured with

MDA-MB-231 cells, SF3B4, NAA38, SNRPG, ELAVL3 and

RBM34 were the top five and in the macrophages co-cultured

with T47D cells, PRPF3, SF3B2, SNRNP48, CELF1 and

RBM46 were the top five. Lin et al found that

knockdown of CELF1 in primary human macrophages led to

increased inflammatory response to M1 stimulation (47). Subsequently, the expression pattern of

candidate splicing factors among normal and 4 breast cancer

subtypes was explored. Generally, splicing factors responsible for

each condition showed similar expression pattern among the samples

(Fig. 7A). In addition, we

characterized the expression pattern of these splicing factors

among samples from the GSE75130 dataset. Splicing factors such as

CPSF7, RBM33, SNRNP48 responsible for the altered AS events

in MDA-MB-231 cells cocultured with macrophages showed a similar

expression pattern among the different treatments (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

In the present study, mutual editing of alternative

splicing (AS) between tumor cells and macrophage was investigated

by re-exploring a previous dataset. Importantly, it was found that

ER+ and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) were

differentially regulated from the AS events view when co-cultured

with macrophages. However, DNA repair and DNA damage processes were

enriched in both ER+ and TNBC after co-culturing with

macrophages. Meanwhile, macrophages were also differentially

regulated from the biological processes view by co-culturing with

ER+ and TNBC. These results revealed a new view of the

mutual regulation between tumor cells and macrophages, in which