Introduction

Gastric xanthelasma is a benign lesion that was

first described in 1887 (1). It is

characterized by the presence of lipid islands in the gastric

mucosa (2), and infiltration of

lamina propria with foamy macrophages under the microscope

(3). The prevalence of gastric

xanthelasma ranges from 0.018 to 7.7% according to the reported

literature (4–10). The etiology and pathogenesis are

still unclear. Foamy macrophages broken-down to the cell membranes

after mucosal damage to the stomach and abnormality of the lipid

metabolism are the main hypotheses to explain the etiology and

pathogenesis (5,11).

Certain studies have evaluated the correlation

between gastric xanthelasma and numerous factors, such as H.

pylori, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and early

gastric cancer, but there were some conflicting conclusions.

Research by Hori and Sutsumi revealed that gastric xanthelasma was

related to H. pylori (12);

however, research by Yi revealed a negative result concerning H.

pylori (5). Studies by both

Chen et al and Köksal et al found that gastric

xanthelasma was related to atrophic gastritis and intestinal

metaplasia (10,13). Nevertheless, research from Japan

indicated that xanthelasma may be a warning sign for the presence

of early gastric cancer (4,14).

The follow-up strategy varies among patients who

have different risks of gastric cancer. Distinctly understanding

the risk factors of gastric xanthelasma is important to manage

patients who have a high risk of developing gastric cancer.

Therefore, we retrospectively analysed the relationship between

gastric xanthelasma and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic or

pathological features by performing a cross-sectional study.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present study is a cross-sectional retrospective

study that was performed at the Department of Gastroenterology of

Shanghai Ruijin Hospital North between July 2016 and June 2017. All

of the patients signed an informed consent form before the

procedure. The informed consent forms obtained the consent of

patients to use their clinical data, and assured them that no

identifiable personal information would be disclosed. The present

study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jiading

Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shanghai, China)

(approval no. 2017005).

Patients

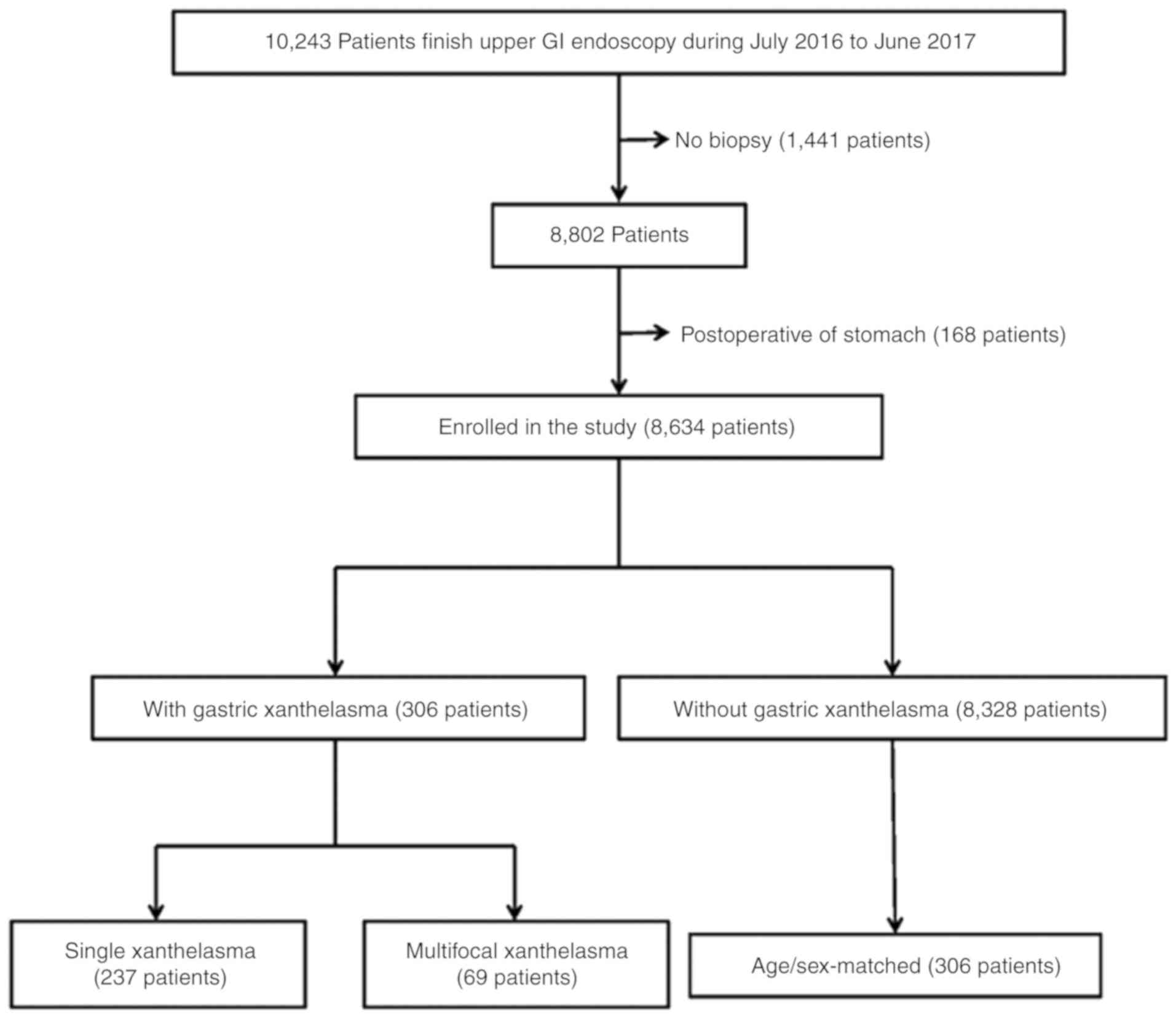

A total of 10,243 patients underwent upper GI

endoscopic examinations. The patients who did not have a stomach

biopsy pathological result and who had previously undergone

gastrectomy were excluded from this study. The following factors

were examined retrospectively: Age, sex, endoscopy findings, and

pathological results. Finally, 8,634 patients were enrolled in the

study, as presented in Fig. 1. To

exclude the influence of age and sex, controls matched with the

patients in terms of age and sex were also analyzed.

Endoscopic procedure

Upper GI endoscopic examination was performed using

pan-endoscopes (model name: Fujinon VP-4450HD-EG-590WR; Fujifilm)

equipped with the Picture Archiving and Communication System

(PacsVideo diagnostic work station, Neusoft Group Co., Ltd.). All

of the examinations were performed by 11 experienced endoscopists,

who carefully observed the esophagus, the entire stomach, and the

duodenum. The endoscopy findings, including peptic ulcer, bile

reflux, gastric polyp, and gastric xanthelasma, were recorded. Two

non-targeted biopsies in the antrum were routine biopsies.

Additional biopsies were collected where lesions were found. The

diagnosis of gastric xanthelasma was based on endoscopy and

histopathologic examination of biopsy samples. Anatomic locations

of all xanthelasmas were recorded during the procedure.

Histologic evaluation

The biopsy samples were fixed in 4% formalin,

embedded in paraffin in room temperature, and were performed on

4-µm sections. The histopathological changes of specimens were

stained by hematoxylin-eosin staining and were observed under light

microscope at ×400 magnification (Olympus BX-51; Olympus).

Histological diagnosis was independently performed by two

experienced pathologists. The pathological results, including

simple atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, H. pylori, dysplasia,

and gastric cancer, were recorded according to the updated Sydney

system (15).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp.) statistical package for

Windows was used for the statistical analysis. Data concerning age

were expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences in age between the two

groups were analyzed by the independent samples t-test or the

Mann-Whitney U test if the data were not parametric. The Chi-square

test was used to compare categorical variables in different groups,

and the Fisher's exact test was used when low anticipated cell

counts were noted. Both univariate analysis and binary logistic

regression were used to analyze the association of gastric

xanthelasma with other factors. All of the calculated P-values were

two-tailed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of patients with and

without gastric xanthelasma

Upon examination of the 8,634 patients, a total of

306 (3.54%) patients had xanthelasma. According to the presence of

gastric xanthelasma, the patients were divided into the following

two groups: With xanthelasma and without xanthelasma. The clinical

characteristics of the two groups are summarized in Table I. The average age of patients with

xanthelasma was 55.76 years, which was higher than that of those

without xanthelasma (P<0.0001). The frequency of duodenal ulcer

in the group with xanthelasma was less than that in the group

without xanthelasma (6.5 vs. 10.7%, P=0.020). The frequency of

atrophy in patients with xanthelasma was significantly higher than

those without xanthelasma (30.1 vs. 18.9%, OR 1.839, 95% CI

1.432-2.362, P<0.0001). The frequency of intestinal metaplasia

in patients with xanthelasma was also significantly higher than

that in those without xanthelasma (59.2 vs. 30.5%, OR 3.296, 95% CI

2.612-4.159, P<0.0001). However, there were no significant

differences in sex, gastric ulcer, bile reflux, gastric polyp,

H. pylori, dysplasia, and gastric cancer between the two

groups.

| Table I.Basic characteristics of the study

population with and without gastric xanthelasma. |

Table I.

Basic characteristics of the study

population with and without gastric xanthelasma.

| Characteristics | With xanthelasma

(n=306) n (%) | Without xanthelasma

(n=8,328) n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 55.76±11.18 | 49.17±13.58 |

|

|

<0.0001a |

| Sex |

|

| 0.860 | 0.684-1.081 | 0.201b |

| Male | 164 (53.6%) | 4,150 (49.8%) |

|

|

|

|

Female | 142 (46.4%) | 4,178 (50.2%) |

|

|

|

| Gastric ulcer |

|

| 0.761 | 0.402-1.442 | 0.470b |

|

Present | 10 (3.3%) | 354

(4.3%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 296 (96.7%) | 7,974 (95.7%) |

|

|

|

| Duodenal ulcer |

|

| 0.584 | 0.369-0.923 | 0.018b |

|

Present | 20 (6.5%) | 891

(10.7%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 286 (93.5%) | 7,437 (89.3%) |

|

|

|

| Bile reflux |

|

| 0.857 | 0.561-1.309 | 0.542b |

|

Present | 24 (8.9%) | 752

(9.3%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 282 (91.1%) | 7,576 (90.7%) |

|

|

|

| Gastric polyp |

|

| 1.178 | 0.811-1.712 | 0.363b |

|

Present | 32

(10.5%) | 751

(9.0%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 274 (89.5%) | 7,577 (91.0%) |

|

|

|

| Atrophy |

|

| 1.839 | 1.432-2.362 |

<0.0001b |

|

Present | 92

(30.1%) | 1,578 (18.9%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 214 (69.9%) | 6,750 (81.1%) |

|

|

|

| Intestinal

metaplasia |

|

| 3.296 | 2.612-4.159 |

<0.0001b |

|

Present | 181 (59.2%) | 2,542 (30.5%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 125 (40.8%) | 5,786 (69.5%) |

|

|

|

| H. pylori |

|

| 1.018 | 0.795-1.305 | 0.899b |

|

Present | 93

(30.4%) | 2,499 (30.0%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 213 (69.6%) | 5,829 (70.0%) |

|

|

|

| Dysplasia |

|

| 0.997 | 0.996-0.998 | 0.9999b |

|

Present | 0 (0) | 27

(0.3%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 306 (100%) | 8,301 (99.7%) |

|

|

|

| Gastric cancer |

|

| 1.112 | 0.407-3.043 | 0.836b |

|

Present | 4

(1.3%) | 98

(1.2%) |

|

|

|

|

Absent | 302 (98.7%) | 8,230 (98.8%) |

|

|

|

The significantly different factors were evaluated

by binary logistic analysis. The results revealed that age and

intestinal metaplasia remained significantly related to gastric

xanthelasma (P<0.0001; Table

II).

| Table II.Binary logistic analysis of factors

related to gastric xanthelasma. |

Table II.

Binary logistic analysis of factors

related to gastric xanthelasma.

|

Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 1.027 | 1.017-1.037 | <0.0001 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 0.650 | 0.410-1.032 | 0.068 |

| Atrophy | 0.945 | 0.720-1.240 | 0.683 |

| Intestinal

metaplasia | 2.700 | 2.090-3.487 | <0.0001 |

Comparison between patients with

gastric xanthelasma and age/sex-matched controls without gastric

xanthelasma

To eliminate the statistical influence of age, 306

patients without xanthelasma were matched in terms of age and sex

with patients with xanthelasma. The differences in duodenal ulcer,

atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia between these subgroups were

analyzed. The Chi-square test revealed that between the two groups,

there was no difference in the presence of duodenal ulcer

(P=0.872), but there were significant differences in the presence

of atrophy (OR 1.763, 95% CI 1.214-2.560, P=0.003) and intestinal

metaplasia (OR 2.508, 95% CI 1.811-3.474, P<0.0001) (Table III). Furthermore, binary logistic

analysis revealed that intestinal metaplasia was significantly

related to gastric xanthelasma (OR 2.338, 95% CI, 1.659-3.297,

P<0.0001), while atrophy was not related to gastric xanthelasma

(P=0.221; Table IV).

| Table III.Comparison between patients with

gastric xanthelasma and age/sex-matched controls without gastric

xanthelasma. |

Table III.

Comparison between patients with

gastric xanthelasma and age/sex-matched controls without gastric

xanthelasma.

|

Characteristics | With xanthelasma

(n=306) n (%) | Without xanthelasma

(n=306) n (%) | OR | 95% CI | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Duodenal ulcer |

|

| 0.949 | 0.503-1.789 | 0.026 | 0.872a |

|

Present | 20 (6.5) | 21 (6.9) |

|

|

|

|

|

Absent | 286 (93.5) | 285 (93.1) |

|

|

|

|

| Atrophy |

|

| 1.763 | 1.214-2.560 | 8.963 | 0.003a |

|

Present | 92

(30.1) | 60

(19.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

Absent | 214 (69.9) | 246 (80.4) |

|

|

|

|

| Intestinal

metaplasia |

|

| 2.508 | 1.811-3.474 | 31.174 |

<0.0001a |

|

Present | 181 (59.2) | 112 (36.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

Absent | 125 (40.8) | 194 (63.4) |

|

|

|

|

| Table IV.Binary logistic analysis of factors

related to gastric xanthelasma. |

Table IV.

Binary logistic analysis of factors

related to gastric xanthelasma.

|

Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Atrophy | 1.284 | 0.861-1.916 | 0.221 |

| Intestinal

metaplasia | 2.338 | 1.659-3.297 | <0.0001 |

Comparison of basic characteristics

between patients with single and multifocal xanthelasma

A subgroup analysis compared the basic

characteristics between patients with single and multifocal

xanthelasma. The average ages of patients with single and

multifocal xanthelasma were 55.20 and 57.99 years, respectively,

which revealed no significant difference (P=0.074). Other factors,

including sex, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, H. pylori,

and gastric cancer also exhibited no differences (P>0.05;

Table V).

| Table V.Basic characteristics of the study

population with single and multifocal xanthelasma. |

Table V.

Basic characteristics of the study

population with single and multifocal xanthelasma.

|

Characteristics | Single xanthelasma

(n=237) n (%) | Multifocal

xanthelasma (n=69) n (%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 55.20±11.62 | 57.99±10.43 |

| 0.074a |

|

Sex |

|

| 1.216 | 0.270b |

|

Male | 123 (51.9%) | 41 (59.4%) |

|

|

|

Female | 114 (48.1%) | 28 (40.6%) |

|

|

| Atrophy |

|

| 1.052 | 0.305b |

|

Present | 64

(27.0%) | 23 (33.3%) |

|

|

|

Absent | 173 (73.0%) | 46 (66.7%) |

|

|

| Intestinal

metaplasia |

|

| 0.630 | 0.427b |

|

Present | 135 (57.0%) | 43 (62.3%) |

|

|

|

Absent | 102 (43.0%) | 26 (37.7%) |

|

|

| H.

pylori |

|

| 1.472 | 0.225b |

|

Present | 71

(30.0%) | 26 (37.7%) |

|

|

|

Absent | 166 (70.0%) | 43 (62.3%) |

|

|

| Gastric cancer |

|

|

| 0.9999c |

|

Present | 3

(1.3%) | 1 (1.4%) |

|

|

|

Absent | 234 (98.7%) | 68 (98.6%) |

|

|

Comparison of localization

characteristics between gastric xanthelasma patients with and

without intestinal metaplasia

The locations of gastric xanthelasma were recorded

as cardia, fundus, corpus, angle, and antrum of the stomach.

Subgroup analysis compared localization characteristics between

gastric xanthelasma patients with and without intestinal

metaplasia; however, there were no significant differences in

localization characteristics (P>0.05; Table VI).

| Table VI.Location characteristics of gastric

xanthelasma with or without intestinal metaplasia. |

Table VI.

Location characteristics of gastric

xanthelasma with or without intestinal metaplasia.

| Location | With intestinal

metaplasia (n=181) | Without intestinal

metaplasia (n=125) |

χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Cardia |

|

|

| 0.479a |

|

Present | 6 | 2 |

|

|

|

Absent | 175 | 123 |

|

|

| Fundus |

|

| 0.287 | 0.592b |

|

Present | 9 | 8 |

|

|

|

Absent | 172 | 117 |

|

|

| Corpus |

|

| 0.153 | 0.696b |

|

Present | 26 | 16 |

|

|

|

Absent | 155 | 109 |

|

|

| Angle |

|

| 1.320 | 0.251b |

|

Present | 11 | 12 |

|

|

|

Absent | 170 | 113 |

|

|

| Antrum |

|

| 3.425 | 0.064b |

|

Present | 79 | 68 |

|

|

|

Absent | 102 | 57 |

|

|

Discussion

The prevalence of gastric xanthelasma was 3.54% in

our study, which is consistent with that in the reported literature

and is higher than a prevalence of 0.8% reported from China in 1989

and 2017 (10). The present study

revealed that gastric xanthelasma was associated with age, duodenal

ulcer, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia using univariate

analysis. Binary logistic analysis revealed that gastric

xanthelasma was significantly associated with age and intestinal

metaplasia. After adjusting for age, xanthelasma remained

associated with intestinal metaplasia. Number and location of

gastric xanthelasma exhibited no difference for intestinal

metaplasia.

Previous research has indicated that gastric

xanthelasma had a strong correlation with atrophy (16,17),

intestinal metaplasia and early gastric cancer (18,19).

Furthermore, in a previous study, 44.4-76.0% of gastric xanthelasma

patients were diagnosed as having atrophy (14). Isomoto et al found that

gastric xanthelasma patients had more severe atrophy than controls

(17). The present study revealed

that 30.1% of gastric xanthelasma patients had atrophy, and this

rate was lower than that reported in the literature. Moreover, in

previous studies, 13.3-48.9% of gastric xanthelasma patients were

diagnosed as having intestinal metaplasia (18,19).

However, the present data revealed that 59.2% of gastric

xanthelasma patients had intestinal metaplasia, which is the

highest ever reported. Furthermore, in previous research,

14.0-20.1% of gastric xanthelasma patients were diagnosed as having

early gastric cancer, and 47.6-72.5% of early gastric cancer

patients were observed to have gastric xanthelasma (16). However, the present research

indicated that gastric xanthelasma patients showed no significant

increase in early gastric cancer when compared to those without

gastric xanthelasma, which is consistent with the result reported

by Köksal et al (13).

Notably, binary logistic analysis revealed that

gastric xanthelasma was an independent risk factor for intestinal

metaplasia, not for atrophy and early gastric cancer, which is

inconsistent with the literature (16). Sekikawa et al conducted

research on the association beween gastric xanthelasma and other

endoscopic examinations results, including atrophy, gastric ulcer,

duodenal ulcer, reflux esophagitis, fundic gland polyp, and gastric

cancer, but they did not analyze the association between gastric

xanthelasma and pathological results of gastric mucosa (14). Two researchers completed the

analysis of the relationship between gastric xanthelasma and

pathological results of gastric mucosa; however, multivariate

correlation analysis was not performed, and the authors concluded

that gastric xanthelasma is a warning marker of multifocal atrophic

gastritis and advanced intestinal metaplasia (13). The present univariate analysis

revealed that gastric xanthelasma was significantly associated to

both atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, while binary logistic

analysis revealed that atrophy was not associated to gastric

xanthelasma. This indicated that atrophy was not an independent

factor for gastric xanthelasma.

Researchers from Japan revealed that gastric

xanthelasma was an independent risk factor for early gastric cancer

(16). However, the present study

did not derive the same conclusion. There are some possible reasons

for this discrepancy. First, the detection rate of early gastric

cancer was 61.7% in 2008, according to the nationwide

population-based data in Japan (20); however, this rate is lower than 10%

in China (21). Second, image

enhanced endoscopy (IEE), such as magnifying endoscopy with

narrow-band imaging, is generally used in Japan; however, IEE is

not prevalently used in China (22).

Moreover, 30% of patients were diagnosed as having

H. pylori infection by pathologists in our study, but there

was no difference between patients with and without gastric

xanthelasma. A study from South Korea presented the same conclusion

concerning H. pylori (5),

however two researchers in the 1990s found that gastric xanthelasma

was closely associated with H. pylori (12,17).

In the present study it was also revealed the number

and location of gastric xanthelasma exhibited no difference for

intestinal metaplasia. However, research by Köksal et al

revealed that multiple xanthelasma patients had a higher

probability of being diagnosed as having intestinal metaplasia than

those with single xanthelasmas, and the location of gastric

xanthelasma exhibited no difference (13).

While the present research is single-center and

retrospective, the data are integral and credible. The present

study, however has some limitations. First, a single-center study

may lack representation; therefore, multicenter research is

required. Second, in the present research, H. pylori

infection was based on pathology diagnosis and we did not have

complete data of other tests, which may have caused bias while

analyzing the relationship between gastric xanthelasma and H.

pylori infection. Third, due to only two non-targeted biopsies

in our routine biopsy, the OLGA and OLGIM systems could not be used

to evaluate the correlation between gastric xanthelasma and the

grade of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia.

In summary, gastric xanthelasma was associated with

age and intestinal metaplasia. Age- and sex-matched analysis

revealed that gastric xanthelasma was significantly associated with

intestinal metaplasia. This indicates that gastric xanthelasma may

be an independent endoscopic warning sign of intestinal metaplasia.

Therefore, when gastric xanthelasma is encountered during an

endoscopic procedure, more attention should be paid since it may

indicate intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Meiyu Shi from

Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine for

biostatistics support.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Chinese

Medicine Key Disciplines of Jiading District (grant no.

2017-ZYZDZK-01) and the Shanghai Health and Wellness Commission

Fund (grant no. 201640231).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are

available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

DX and PC conceived and designed the study. XY, YW

and PC provided administrative support and study patients. DX

collected and assembled the data. DX and XT performed data analysis

and interpretation. All of the authors contributed to the writing

and final approval of the manuscript and agree to be accountable

for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or

integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated

and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All of the patients signed an informed consent form

before the procedure. The informed consent forms obtained the

consent of patients to use their clinical data, and assured them

that no identifiable personal information would be disclosed. The

present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of

Jiading Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shanghai, China)

(approval no. 2017005).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Khachaturian T, Dinning JP and Earnest DL:

Gastric xanthelasma in a patient after partial gastrectomy. Am J

Gastroenterol. 93:1588–1589. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kimura K, Hiramoto T and Buncher CR:

Gastric xanthelasma. Arch Pathol. 87:110–117. 1969.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Coates AG, Nostrant TT, Wilson JA, Dobbins

WO III and Agha FP: Gastric xanthomatosis and cholestasis. A causal

relationship. Dig Dis Sci. 31:925–928. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sekikawa A, Fukui H, Maruo T, Tsumura T,

Kanesaka T, Okabe Y and Osaki Y: Gastric xanthelasma may be a

warning sign for the presence of early gastric cancer. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 29:951–956. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yi SY: Dyslipidemia and H pylori in

gastric xanthomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 13:4598–4601. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gencosmanoglu R, Sen-Oran E,

Kurtkaya-Yapicier O and Tozun N: Xanthelasmas of the upper

gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroentero. 39:215–219. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Petrov S, Churtchev J, Mitova R, Boyanova

L and Tarassov M: Xanthoma of the stomach-some morphometrical

peculiarities and scanning electron microscopy.

Hepatogastroenterology. 46:1220–1222. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen YS, Lin JB, Dai KS, Deng BX, Xu LZ,

Lin CD and Jiang ZG: Gastric xanthelasma. Chin Med J (Engl).

102:639–643. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Terruzzi V, Minoli G, Butti GC and Rossini

A: Gastric lipid islands in the gastric stump and in non-operated

stomach. Endoscopy. 12:58–62. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chen Y, He XJ, Zhou MJ and Li YM: Gastric

xanthelasma and metabolic disorders: A large retrospective study

among Chinese population. World J Gastroenterol. 23:7756–7764.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lechago J: Lipid islands of the stomach:

An insular issue? Gastroenterology. 110:630–632. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hori S and Tsutsumi Y: Helicobacter

pylori infection in gastric xanthomas: Immunohistochemical

analysis of 145 lesions. Pathol Int. 46:589–593. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Köksal AŞ, Suna N, Kalkan İH, Eminler AT,

Sakaoğulları ŞZ, Turhan N, Saygılı F, Kuzu UB, Öztaş E and Parlak

E: Is gastric xanthelasma an alarming endoscopic marker for

advanced atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia? Dig Dis Sci.

61:2949–2955. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sekikawa A, Fukui H, Sada R, Fukuhara M,

Marui S, Tanke G, Endo M, Ohara Y, Matsuda F, Nakajima J, et al:

Gastric atrophy and xanthelasma are markers for predicting the

development of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 51:35–42.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH and Correa

P: Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney

System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis,

Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 20:1161–1181. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kitamura S, Muguruma N, Okamoto K,

Tanahashi T, Fukuya A, Tanaka K, Fujimoto D, Kimura T, Miyamoto H,

Bando Y, et al: Clinicopathological assessment of gastric xanthoma

as potential predictive marker of gastric cancer. Digestion.

96:199–206. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Isomoto H, Mizuta Y, Inoue K, Matsuo T,

Hayakawa T, Miyazaki M, Onita K, Takeshima F, Murase K, Shimokawa I

and Kohno S: A close relationship between Helicobacter

pylori infection and gastric xanthoma. Scand J Gastroenterol.

34:346–352. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Arévalo F and Cerrillo G: Gastric xantoma:

Histological findings and clinico endoscopic characteristics in the

‘Hospital Nacional 2 de Mayo’ (1999–2005). Rev Gastroenterol Peru.

25:268–271. 2005.(In Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moretó M, Ojembarrena E, Zaballa M, Tánago

JG, Ibáñez S and Setién F: Retrospective endoscopic analysis of

gastric xanthelasma in the non-operated stomach. Endoscopy.

17:210–211. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

The Editorial Board of the Cancer

Statistics in Japan, . Cancer Statistics in Japan 2016. In:

Foundation for promotion of cancer research; Tokyo: pp. 922017

|

|

21

|

Du YQ, Cai QC, Liao Z, Fang J and Zhu CP:

China experts consensus on the protocol of early gastric cancer

screening (2017, Shanghai). Chin J Digest. 38:87–92. 2018.

|

|

22

|

Yao K, Uedo N, Muto M and Ishikawa H:

Development of an e-learning system for teaching endoscopists how

to diagnose early gastric cancer: Basic principles for improving

early detection. Gastric cancer. 20 (Suppl 1):S28–S38. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|