Introduction

Ovarian cancer, a malignant tumor frequently present

in the reproductive system of women, can be classified based on its

primitive tissue type into epithelial ovarian cancer, germ cell

tumors and stromal tumors. However, the pathogenesis of ovarian

cancer has yet to be fully elucidated. The currently favored

hypotheses include BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations (1), sexual hormone imbalance and prolonged

chronic inflammation stimulation. Concurrently, epidemiologic

studies indicated that the disease prevalence significantly

correlates with ethnicity and country (1). Due to its inconspicuous symptoms at

early stages, it is challenging to identify promptly; although it

can be managed at advanced stages with surgery and treatments such

as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the outcome remains

unsatisfactory. This, together with the extraordinary incidence and

mortality rate, poses an alarming threat to women's health,

compelling immediate exploration of innovative therapies.

In recent years, mitochondria-associated endoplasmic

reticulum (ER) membrane (MAM), a unique cellular membrane structure

existing between the outer mitochondrial membrane and the ER, has

become implicated in a range of physiological functions such as

mitochondrial biogenesis, function regulation, calcium ion

carriage, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress and autophagy through

this unique position. More importantly, mounting evidence indicates

that MAMs may act as a potential therapeutic target influencing

mitochondria and ER, two vital organelles in the cancer field.

Hence, elucidating the MAMs could potentially provide a novel

strategy for tackling diseases including ovarian cancer in the

future.

However, despite the relatively modest research

conducted on MAMs till date, it is evident from all empirical

findings that MAMs bear a relationship with various disorders

including cancers and neurodegenerative diseases. Regardless of

whether it is basic or clinical research, reports on MAMs are

comparatively scarce. Given its exceptional physiological structure

and distribution, it is conceivable that MAMs hold substantial

research value. Therefore, the impact of MAMs on physiological

function was primarily discussed in the present review and fresh

perspectives on the practical application of MAMs in ovarian cancer

treatment were provided via examining proteins existing on MAMs,

combined with their implementation in the management of ovarian

cancer.

Mitochondrial inner membrane association

with cellular physiological processes

In the appraisal of the profound correlation between

ER and mitochondria, it was found that the dynamic adjustments of

mitochondria and ER directly influence their physiological role and

structure. These phenomena imply the existence of MAMs. Employing

electron microscopy technology, the gap between mitochondria and ER

was observed to be ~10-30 nanometers-an incredibly diminutive

distance facilitating a plethora of protein interactions within

this ambit, thereby constructing the biological grounding to affect

the functions of mitochondria and ER (2). Despite the prevalent perception that

the functions of mitochondria and ER have distinct differences,

they can reciprocally influence each other via MAMs.

While it was previously proposed that MAMs are an

illusion (2), more recent

investigation utilizing cutting-edge scientific tools confirmed:

MAMs indeed exist. Notably, MAMs are not static; their distance

often varies with the presence of ribosomes. For instance, on a

smooth ER (SER), the distance of MAMs is usually 10–15 nanometers,

whereas on a rough ER (RER) it expands to 20–30 nanometers. More

crucially, MAMs serve as pivotal in maintaining cell calcium

homeostasis (3,4), lipid homeostasis (5), mitochondrial dynamic equilibrium

(6) and the stability of

organelles, among other physiological functions, which are critical

for the survival of the organism.

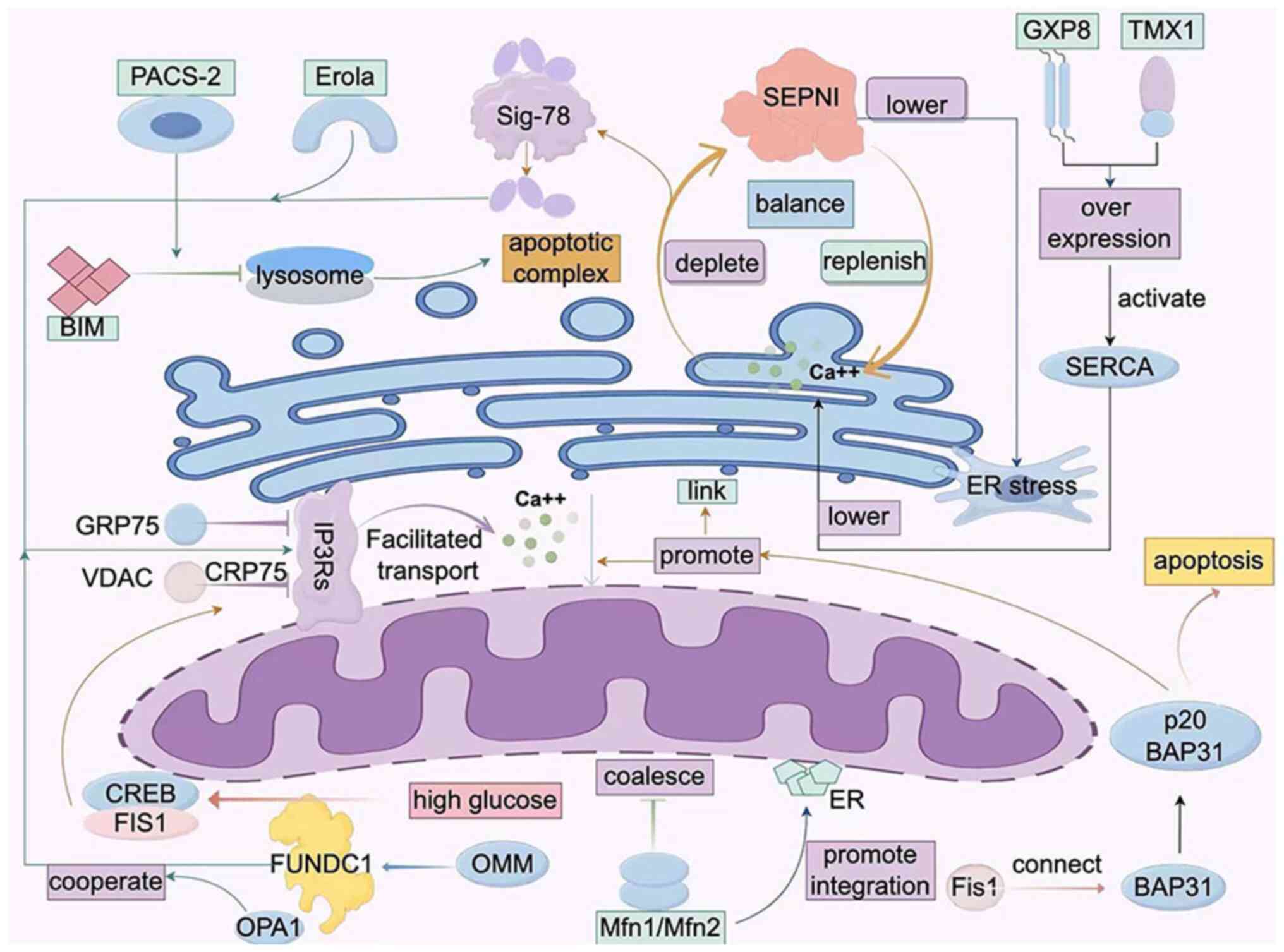

Calcium homoeostasis

Calcium ions (Ca2+) serve as the

secondary messengers within cells, regulating a myriad of cellular

processes. MAMs, significant bridges for Ca2+ transport,

finely tune Ca2+ signal transmission ensuring precise

and flawless execution of cell biological functions. At present,

two primary types of Ca2+ release channels have been

well-understood in MAMs, namely: IP3Rs and RyRs.

The IP3Rs, voltage-dependent anion channels that

dominate Ca2+ release above MAMs, collaborate with GRP75

and VDAC to take on this formidable task. The tripartite protein

complex assists calcium ions in traversing from mitochondria to

ER.

Another primal ER protein SEPN1, abundant in this

type of MAMs, can replenish calcium ions on the ER when it is

depleted, thus circumventing ER stress. Besides protecting IP3R

from oxidative harm by Ero1a, SEPN1 also upholds calcium ion

equilibrium between MAMs, mitochondria and ER (6).

Existing in the same form as a protein complex are

Sig-78 and immunoglobulin. When calcium ions are depleted in the

ER, Sig-78 dissociates from the complex and interacts with IP3Rs,

substantially enhancing Ca2+ influx into mitochondria.

Moreover, Ero1a, an oxidase residing in MAMs, prompts calcium ion

flux towards mitochondria when faced with ER stress by oxidative

binding to IP3R, thereby activating IP3R (7,8).

Lastly, glutathione peroxidase 8 (GXP8), a bipolar

transmembrane protein present in MAMs, can lower calcium level on

the ER by suppressing the activity of SERCA when overexpressed.

Also acting similar to GXP8 is the redox enzyme TMX1 located on the

ER, again by preventing the action of SERCA. SERCA plays a core

role in the transportation process of calcium ions. It regulates

the content of intracellular Ca2+ ions and profoundly

influences the flow of calcium ions in MAMs. When the pressure on

the ER becomes excessive, the activity of SERCA1 dramatically

escalates, thereby propelling calcium ions from the ER to

mitochondria, culminating in mitochondrial apoptosis (7,8).

Moreover, mitochondria demonstrate their unique role

during the transport of calcium ions over a short time period. Upon

the transfer of calcium ions from the ER to MAMs (7,8), high

calcium concentration regions often emerge macroscopically. Under

this state, the speed at which mitochondria absorb calcium ions

markedly accelerates. By contrast, when calcium ion concentration

is low, the efficiency of mitochondria in absorbing calcium ions

noticeably decreases. Therefore, the regulation of calcium ion

concentration is indeed heavily influenced by a profound impact led

by MAMs. Besides, existing research has unveiled that mitofusin 2

(Mfn 2) is a pivotal target for regulating calcium ion

concentration in MAMs; however, some studies have yielded contrary

experimental conclusions (9). Thus,

there still remains considerable research exploration space in

terms of how MAMs affect the degree of influence on the flow of

calcium ions between mitochondria and ER.

Lipid homeostasis

There is robust correlation between MAMs and lipid

homeostasis. Since other organelles lack the capacity to synthesize

phospholipids from their precursor, and the ER is a pivotal site

for regulating cell intrinsic lipid balance, lipids must diffuse

from the ER into other organelles. It has been previously reported

that MAMs are a cholesterol enriched membrane system, predominantly

composed of caveolin proteins, serving an essential function,

contributing towards enriching the related elements of MAMs' lipid

metabolism, thereby underscoring the indispensable role of MAMs in

preserving lipid homeostasis. Phosphatidyl serines (PS), as the

predominant enzyme system generated within the ER, is primarily

localized on MAMs. Subsequently, it translocates to mitochondria to

be converted into phosphatidyl ethanolamines (PE) (10). Some of the PE, upon return to the

ER, transforms into phosphatidyl cholines, which is further

distributed to various other organelles. In this process, the

pro-phospholipid acid of PS is synthesized in the ER, but

necessitates storage in MAMs.

In addition to phospholipid synthesis, MAMs also

perform another crucial element of cholesterol metabolism. The

newly synthesized cholesterol within the ER must be transported to

mitochondria to convert into pregnenolone, the primary substance of

sex steroids. In the rate-limiting step of this process, MAMs serve

a pivotal role. Furthermore, research indicates the abundant

presence of MAMs in cholesterol acyltransferase 1 (ACAT1), an

enzyme responsible for the conversion of free cholesterol into

cholesterol esters (CEs). Such CEs are commonly stored in fat

droplets. Hence, it is feasible to indirectly evaluate the activity

of MAMs by measuring the activity of ACAT1 (11). As such, MAMs have gradually emerged

as the primary activator of mitochondrial steroid synthesis.

Subsequently, MAMs also participate in the generation of ceramide,

regulating cell growth, inflammation response, differentiation and

apoptosis (12,13).

Mitochondrial dynamics

Significantly, it has been previously elucidated

that MAMs are the initial locations of mitochondrial division

(14). For instance, mitochondrial

division proteins 1, mitochondrial division factors, and

mitochondrial dynamics proteins are all sequestered at the MAMs

site and completed prior to mitochondrial division (15). Additionally, processes such as mtDNA

replication, mitochondrial transport and mitochondrial

self-division, all revolve around the MAMs.

Mitochondrial fusion and division, a highly dynamic

network system, maintains a steady state equilibrium of fusion and

division under normal physiological conditions to ensure optimal

cell functioning. Certainly, appropriate stimulation is paramount

for maintaining a high quality of mitochondria. Among key

constituents of the mitochondrial fusion mechanism, Mfn1, Mfn2 and

optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) play pivotal roles. Notably, Mfn1, acting as

a requisite GTPase for outer membrane fusion, primarily restricts

mitochondrial function through its interaction with Mfn1 on the

MAMs (16). In concert with Mfn1

and Mfn2 on the MAMs, Mfn2 helps form the mitochondrial outer

membrane and acquires specific morphology (17). Given the heightened degree of Mfn2

enrichment on the MAMs, it is conjectured that the MAMs hold great

significance during mitochondrial fusion, particularly when

post-MITOL/MARCH5 ubiquitination machinery causes alterations in

the intersection between the ER and mitochondria (18).

Acting as a cytosolic protein, Dlp1 dynamically

congregates to the mitochondrial membrane and substantially

enhances membrane contraction velocity via a GTP-dependent

oligomerization pathway. Under hypoxic circumstances, the

accumulation of the OMM protein FUNDC1 induces ectopic Dlp1

accumulation in the MAMs (19).

Furthermore, as an integral component of the apoptotic process,

Fis1 can bind to BAP31 in the MAMs, transmitting the mitochondrial

apoptotic signals to the ER. BAP31, a critical escort protein on

the ER membrane, participates in the degradation of misfolded

protein and apoptotic signaling within the endoplasmic reticulum

stress pathway. When Fis1 unites with BAP31, it cleaves BAP31 into

p20 BAP31; as an apoptosis-promoting protein, p20 BAP31 activates

procaspase-8 to convert it into a functional form, which can cleave

Bid and initiate cell apoptosis (20,21).

Activation of p20 BAP31 also facilitates Ca2+

translocation from the ER to the mitochondria, indicating the

ability of cellular apoptotic signals to feedback to the

mitochondria (22,23). The stability of calcium ions

similarly directly or indirectly influences the dynamics of the

mitochondria (24).

Apoptosis

The relationship between calcium homeostasis and

tissue structural integrity is exceedingly significant. With the

excessive metabolism of Ca2+, it can induce the opening

of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, escalating the

permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane. The mitochondrion

then undergoes depolarization, subsequently impeding ATP synthesis,

leading to an expansion in the mitochondria's molecular form and

ultimately causing the rupture of the outer membrane, thereby

releasing a substantial amount of cytochrome c, culminating in

apoptosis. Noteworthy, previous studies have also elucidated that

apoptotic signaling exists within MAMs (25–27).

The majority of apoptotic signals from the ER converge on the

mitochondria autophagy pathway. This further suggests that the ER

stress situation will directly influence the physiological

alterations of the mitochondria, and the most pivotal factor among

these is the BH3 protein (25),

which is uniquely activated by the ER and transmits autophagy

signaling to the mitochondria (26). However, presently, it remains

elusive whether this protein can be concurrently activated by all

forms of ER damage, or is activated only during specific

pathological processes where the ER is specifically damaged. It is

conceivable that it may emerge as a potential therapeutic drug

target for diseases in the future (27).

Moreover, the mitochondrial division factor Fis1

aids in maintaining the junctions between the ER and mitochondria

through its interaction with Bap31 (28). When procaspase-8 is recruited, the

cleavage of Bap31 will lead to an increase in mitochondrial

permeability and instigate apoptosis (29,30).

In the ordinary state, ceramide is synthesized via the ceramide

synthase pathway. However, under stress conditions (for example,

heat shock, TNF-α, Fas, chemotherapy drugs, toxins, radiation and

other factors), ceramide can be rapidly synthesized in

sphingomyelinase from sphingomyelinase. The accumulation of

ceramide not only modulates various molecules involved in apoptotic

signaling transductions but can interact with them, such as protein

phosphatase 1A/2A, protein kinase C, NF-κB and Ras. A substantial

accumulation of ceramide can lead to the formation of pores on the

external mitochondrial membrane, induce the release of

pro-apoptotic substances (such as cytochrome C) in the

mitochondrial membrane gap, and propagate stress signals from the

ER to the mitochondria (31).

Whereas suppressing the activity of ACS1/4 can reduce the synthesis

of ceramide and deter the occurrence of cell apoptosis (32). Nevertheless, given the intricate

nature and cross-domain relationships of apoptosis itself, markedly

more profound and meticulous discussions are needed to delve deeper

into this complex matter.

Proteins contributing to the function of

MAMs

The unique attributes of MAMs encompass their

protein composition and structure, underscoring their pivotal roles

in numerous physiological processes. Research on MAM proteins has

unveiled a broad spectrum of physiological functions; however,

comprehensive understanding remains to be achieved due to the

intricate diversity present in the richly diverse MAM proteome. For

example, the GTPase Mfn1/Mfn2, which plays an essential role in

mitophagy during mitotic spindle formation, was identified with

seemingly contradictory functional features (33); also present on the surface of MAMs

are the calcium release channels IP3R and VDAC (35), responsible for regulating

mitochondrial calcium homeostasis. Lastly, Grp75 holds a

significant influence on the organizational structure of MAMs

(38). The interactions among these

proteins remain unexplored and hint at the need for further

research.

FUNDC1

Research signifies that FUNDC1 is a ubiquitous

protein within organisms (46).

This protein is composed of 155 amino acids, encompassing three

membrane spanning regions. Notably, its N terminus harbors the LTR

motif, which aids in interaction with LC3 to regulate autophagy in

mitochondria (41,42). The regulation of this activity is

notably prominent under low oxygen environments; the study

predominantly focused on the effects of decreased Src kinase

activity and weaning tyrosine 18 phosphorylation levels, thereby

reinforcing the mutual interplay between LC3 and FUNDC1 (46).

FUNDC1 can also play a pivotal role in calcium

transfer through interaction with IP3R2. Under hyperglycemic

conditions, the activation of FUNDC1 can stimulate the binding of

CREB to the FIS1 promoter, thereby promoting MAM formation. This

indicates that FUNDC1 plays a critical part in the entire process

of MAM formation. Additionally, FUNDC1 also participates in

regulating mitochondrial dynamics, forming a synergistic

relationship with OPA1. It has been discovered that incorporating

change in lysine 10 in FUNDC1 significantly induces mitochondrial

aggregation, reflecting the importance of FUNDC1 in regulating

mitochondrial dynamics (47). NRF1,

as a transcription factor, can stimulate its expression by binding

to the FUNDC1 promoter 186/176 (48).

In HeLa cells, experiments have revealed that

suppressing expression of FUNDC1 propels mitochondrial fusion,

whereas augmenting its expression retards it, probably by inducing

DRP1 to drive mitochondrial proliferation (49). This process also encompasses

phosphorylation at site S13, which attenuates the interplay between

FUNDC1 and Drp1 while amplifying the interaction with OPA1. These

observations signify that alterations in FUNDC1 structure may guide

distinct pathways that culminate in corresponding alterations in

mitochondrial structure. Research along the path of FUNDC1 upstream

regulation and its influence on structural alteration is projected

to be a vital direction of future studies. Within the unique

structure of MAMs, FUNDC1 plays a pivotal role in the evolution of

various pathologies.

Experimental evidence has confirmed that suppression

of FUNDC1 expression fosters the generation of extensive MAMs in

diabetes-induced cardiomyopathy. This morphological and functional

reconfiguration of MAMs initiates cell apoptosis and the

disintegration of abnormal mitochondria, ultimately resulting in

reduced synthesis and disruption of the respiratory chain function

of mitochondria. In both patients afflicted with heart failure and

murine cardiac muscle cells, a decrease was observed in the FUNDC1

protein level (49). Additional

research uncovered that FUNDC1 mainly impairs mitochondrial

function, causing harm to cardiac muscle cells, and the disruption

of MAMs is intricately linked to mitochondrial dysfunction

(50). Similarly, magnesium oxide

and α-lipoic acid can diminish the phenotypic characteristics of

cardiac muscle cells through interaction with FUNDC1 (51). Besides these diseases, FUNDC1 can

also instigate mitochondrial autophagy, promptly triggering cell

apoptosis and myocardial infarction (52). These instances not only underscore

the significance of FUNDC1 but also spotlight the pivotal position

of MAMs within cellular processes.

PACS-2

The PACS family is composed of the two proteins

PACS-1 and PACS-2, which share a similar structure but exhibit

distinct functions. Both proteins contain a furin binding region

(FBR), an intrinsically disordered mid-region (MR), and a

C-terminal region (CTR) (52).

Specifically, the MR domain encompasses a native nuclear

localization signal (NLS) domain and an Akt phosphorylation site,

although the precise function of the CTR domain remains undefined

(53). The prevailing consensus in

academia suggests that the FBR domain plays a crucial role in

recognizing and adhering to cargo proteins.

In 1998, Werneburg et al (54) identified the crucial role of PACS-1

in directing trafficking across the Golgi network (TGN) for the

first time. Subsequently, in 2005, Köttgen et al (55) postulated that both PACS-1 and PACS-2

were involved in the transport process of polycystin-2 mediated by

members of the TRP ion channel family (TRPP2). PACS-2 can precisely

identify and bind cargo proteins with acidic ionization clusters,

facilitating their transportation towards relevant organelles and

thereby influencing cellular activities ranging from calcium

exchange and apoptosis to membrane transport (56).

Numerous studies suggested that PACS-2 influences

immune-induced apoptosis by regulating MAMs and thereby altering

mitochondrial division. Additionally, PACS-2 binds to CNX in the

cytoplasm and regulates the distribution of CNX to MAMs (57). Moreover, PACS-2 can interact with

BIM, inviting the recruitment of BIM to lysosomes in a

mitogen-activated protein kinase-JNK-dependent manner to form the

apoptosis complex (58). Deeper

research indicates that interaction of PACS-2 with ataxia

telangiectasia mutated (ATMs) can activate NF-κB to promote cell

survival (59). Furthermore,

previous evidence demonstrated that PACS-2 participates in DNA

damage-related apoptosis through two independent mechanisms.

Firstly, following DNA damage, PACS-2 employs its NLS domain to

shuttle itself into the nucleus and interact with SIRT1, thus

hindering the deacetylation of p53, leading to cell cycle arrest

(60). Secondly, upon DNA damage,

PACS-2 engages ATM to activate NF-κB, promoting the expression of

the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL (61). Factors such as TRAIL can induce

dephosphorylation of PACS-2 at Ser437 indirectly via Akt, thereby

stimulating mitochondrial membrane permeability increase and

lysosomal membrane permeability increase (62). By contrast, the stable

phosphorylation of PACS-2 is synchronous with the p53/p21 and

NF-κB/Bcl-xL pathways, serving as a cytoprotective mechanism.

Mfn2

Initially recognized as an obligatory dynein-like

protein integral to outer membrane fusion, Mfn2 has recently been

revealed to be localized on the ER membrane, engaging in reciprocal

interactions with the OMM. Research indicated that the expression

of Mfn2 alters the MAM hierarchy and is capable of enhancing the

ER-mitochondria distance within the cell (63), hinting that it plays a pivotal role

in sustaining mitochondrial morphology and ER-mitochondria contact

sites interconnection. Nevertheless, existing findings pose

contradictions to this hypothesis, revealing that cells with Mfn2

variations or deprivation may actually enhance ER-mitochondria

coupling (64,65), suggesting an imperative for further

investigation into the precise impact of Mfn2 on the MAM.

Significantly, Mfn2 serves as a receptor during the

PINK1-Parkin-mediated autophagy process, playing a critical role in

interface management (66).

Moreover, Mfn2 directly interacts with the mitochondrial transport

machinery, encompassing MIRO1/2 transmembrane transporters,

specifically linked to the function of MARC proteins (67). Mfn2 has been proven to influence the

fatty acid metabolism of mitochondria by binding mitochondrial with

lipid particles (68) and

facilitating the transfer of phosphatidylserine from the ER to the

mitochondria.

The downstream repercussions of Mfn2 on

mitochondrial functionality are manifold, including alterations in

the mitochondrial ultrastructure, cristae and supramolecular

structures, affecting the oxidative phosphorylation process

(69,70). Furthermore, the MAM can also

regulate the oxidative phosphorylation process through calcium ion

signal transmission (71). Mfn2 is

also implicated in modulations of mtDNA stability, potentially due

to its fusion effect leading to decreased mtDNA copies and

increased mtDNA deletion frequency (72) which is pivotal for the distribution

of mitochondrial DNA proteins. Additionally, studies have

highlighted the crucial role of Mfn2 in preserving podocyte

apoptosis through regulating the PERK pathway (73). Therefore, the multifaceted functions

of Mfn2 contribute to explaining why cells lacking Mfn2 display

diminished mitochondrial respiration.

Other proteins

Despite the diverse proteins existing on MAMs, the

functional studies of Mfn2, FUNDC1 and PACS-2 are more

comprehensive. Moreover, the influence of these proteins on related

diseases is more profound. In addition to these pivotal proteins,

MAMs also harbor critical participants including DJ-1, TDP-43 and

CypD, although they do not directly affect MAM structure but play a

crucial regulatory role in specific MAM functions. IP3R is an

important Ca2+ efflux channel located at the ER surface,

which mediates the release of Ca2+ from the ER lumen to

the cytoplasm (74). VDAC is an ion

channel located at the outer mitochondrial membrane; it mediates

the movement of various ions and metabolites into and out of

mitochondria and is involved in a series of cellular activities,

including cell apoptosis, metabolism and regulation of

Ca2+ (75). IP3R and

VDAC are linked by Grp75 to maintain MAM structure (76). It is known that overexpression of

VDAC can enhance the connection between ER and mitochondria,

thereby improving the flux of Ca2+ from the ER to the

mitochondria (77); when silencing

VDAC1, the connection between Grp75 and IP3R1 decreases, suggesting

decreased ER-mitochondrial interaction (78). Cells overexpressing Grp75 exhibit

more IP3R1-VDAC1 interaction sites (79). Silence of IP3R1 or Grp75 can also

reduce the connection between VDAC1 and Grp75 or IP3R1 (80).

Moreover, VAPB located within the ER membrane,

participates in the activation of IRE1/XBP1 axis during the

unfolded protein response in the ER (81,82).

VAPB can form a complex with the outer mitochondrial membrane

protein PTPIP51 and help maintain the structure of MAM. The mutant

form of VAPBP56S, showing stronger affinity for PTPIP51, thereby

promotes the transfer of Ca2+ from the ER to the

mitochondria; knocking out any one of these two genes can reduce

the transfer signal of Ca2+ (83) and decrease the level of contact

between the ER and the mitochondria (84,85).

MOSPD2 is another member of the VAP family; it is a

protein located on the surface of the ER membrane which can connect

the ER and other membrane structures, and can also bind to small

proteins that interact with VAP through the MSP (major sperm

protein structural domain), a protein sequence motif called FFAT,

such as PTPIP51 on the outer mitochondrial membrane (86). REEP1 is a protein located on the ER

and the outer mitochondrial membrane. It has been demonstrated that

REEP1 directly connects the ER and mitochondria through

oligomerization and is involved in the formation of the MAM

structure. Furthermore, REEP1 bends the ER membrane so that the ER

can wrap around the mitochondria, which helps form MAMs (86). The complexity they participate in

further highlights the complexity of MAMs, prompting to conduct

more in-depth exploration (Table I)

(Fig. 1).

| Table I.Functions of proteins on MAMs. |

Table I.

Functions of proteins on MAMs.

| Protein name | Functional

overview | Function | (Refs.) |

|---|

|

IP3Rs-Grp75-VDACs | Calcium

homeostasis | Regulation of

apoptosis, metabolism and Ca2+ | (34) |

| α-Synuclein |

| Promotes

Ca2+ by increasing endoplasmic reticulum and

mitochondrial contact | (39) |

| CypD |

| Affects the

transfer of Ca2+ between the two organelles | (44) |

| FATE1 |

| Downregulation of

the transfer of Ca2+ | (45) |

| Mfn1/MFN2 | The architecture of

MAMs | Maintain the

structural aspects of MAMs and induce endoplasmic Reticulum

stress. | (36) |

| MOSPD2-PTPIP51 |

| Plays a role in

connecting endoplasmic reticulum with other membrane

structures | (37) |

| DJ-1 |

| Enhances the

connection between the ER and mitochondria | (40) |

| TG2 |

| Increase the number

of ER-mitochondrial contacts | (43) |

| NogoB |

| Increase the gap

width of MAMs and affect their function | (45) |

MAMs in ovarian cancer

Cancer cells may modulate the expression of

Ca2+ ion channels, influence signal transduction

mechanisms (87,88), and modify the regulatory capacity of

MAMs on ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ transport to generate a

MDR phenotype (89). This allows

them to evolve continuously and achieve resistance to apoptosis.

Moreover, cancer cells necessitate additional mitochondrial ATP

production to sustain their heightened proliferation activity. As

Ca2+ sustains the activity of various enzymes in the

mitochondrial energy cycle, an appropriate mitochondrial

Ca2+ uptake is crucial for the survival of cancer cells.

However, excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake can lead to

mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, subsequently triggering

mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer cell death. Therefore, how to

balance the control of multiple proteins through MAMs on the

mitochondrial-ER complex mechanism is a pivotal strategy for cancer

cells to acquire resistance to cell death. Currently, the study of

Li et al (90) has

identified GRP75 (a critical chaperone protein) as playing a

pivotal role in the stability of MAMs by forming an

IP3R/GRP75/VDAC1 complex. When GRP75 is absent, it results in a

significant decrease in MAMs' stability, causing Ca2+

disorder between mitochondria and ER, leading to catastrophic

reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and ultimately

resulting in cell apoptosis. It is evident that targeting proteins

on MAMs can be a key target for improving ovarian cancer

research.

However, due to the particularity of MAMs' location

and structure, there remains a lack of definitive direct

correlation with ovarian cancer. Nevertheless, since MAMs are

located between mitochondria and ER, most current studies primarily

elucidate the impact on ovarian cancer from these two vital

organelles, thereby indirectly indicating the potential application

value of MAMs. Therefore, the following exploration of the

relationship among mitochondria, ER, and ovarian cancer provides

new perspectives and assistance for future direct study of MAMs in

ovarian cancer (Table II).

| Table II.Application of MAMs in ovarian

cancer. |

Table II.

Application of MAMs in ovarian

cancer.

| Author, year | Overall | Pointcut | Outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Vianello et

al, 2022 | MAMs | Mitochondrial

autophagy | Inhibition of

mitochondrial autophagy can restore response sensitivity in

cancerous cells to cisplatin. | (94) |

| Zhou et al,

2022 |

|

| The

aryl-glycosylated zinc (II)-cryptolepine complex disrupts aspects

of the mitochondrial autophagy pathway to induce programmed cell

death and autophagy in carcinoma cells. | (95) |

| Yu et al,

2017 |

|

| ABT737 can induce

mitochondrial autophagy, resulting in the release of cytochrome

C. | (96) |

| Chen et al,

2021 |

|

| Pardaxin, an

antibacterial peptide, stimulates the process of apoptosis due to

excess ROS production. | (97) |

| Wang et al,

2020 |

|

| Elastin cell growth

factor H propels the demise of cancer cells by catalyzing

mitochondrial autophagy. | (98) |

| Katreddy et

al, 2018 |

|

| Both siRNA or

Herdegradin activate mitochondrial autophagy to selectively

eradicate cancer cells. | (99) |

| Meng et al,

2022 |

|

| Cancer cell

proliferation is suppressed by suppressing the gene chain

CRL4cul4A/DDB1. | (100) |

| Yuan et al,

2023 |

|

| The augmentation

effect of cancer stem cells can be mitigated by judicious

suppression of mitochondrial autophagy. | (101) |

| Martinez-Outschoorn

et al, 2012 |

|

| The absence of

BRCA1 tumor suppressor gene triggers mitochondrial autophagy and

catabolic processes. | (102) |

| Jin et al,

2020 |

|

| The fucosylation of

TGF-β1 has the potential to activate the regulatory function in

ovarian cancer cells. | (103) |

| Yu et al,

2021 |

|

| Enhancing

PINK1/parkin mediated mitochondrial autophagy degrades the

sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin. | (147) |

| Bae et al,

2021 |

| Endoplasmic

reticulum stress | Campesterol can

inhibit ovarian cancer viainducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and

amplify the efficacy of conventional anticancer drugs. | (104) |

| Cheng et al,

2022 |

|

| The interaction

between OMA1 and endoplasmic reticulum stress can deter drug

resistance in cancer cells. | (114) |

| Jung et al,

2020 |

|

| DPP23 can serve to

diminish the resistance of ovarian cancer by invoking endoplasmic

reticulum stress. | (115) |

| Xu et al,

2021 |

|

| The PHLDA1 protein

mediates ovarians cancer cell apoptosis versity through the

endoplasmic reticulum stress response mechanism. | (116) |

| Kim and Lee,

2023 |

|

| The validity of

6-gingerolovercoming resistance towards gefitinib in ovarian cancer

cells is confirmed via stimulating endoplasmic reticulum

stress. | (117) |

| Bahar et al,

2021 |

|

| The combined

administration of PARP inhibitor and cisplatin downregulated

cisplatin-resistant OC cells, thereby mitigating endoplasmic

reticulum stress and overcoming PARP inhibitor cross- resistance in

OC. | (118) |

| Rezghi et

al, 2021 |

|

| Verified

miR-3c-1-1p engages cell apoptosis through endoplasmic reticulum

stress. | (120) |

| Kong et al,

2021 |

|

| The nanoparticle's

reduction-sensitive polymer form can escalate endoplasmic reticulum

stress, thus enhancing therapeutic efficacy. | (121) |

| Wang et al,

2020 |

|

| Epoxyeicosatrienoic

acid H induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and stimulates

apoptosis. | (122) |

| Wang et al,

2020 |

|

| The chemical

reagent DWP05195 triggers cellular apoptosis through the induction

of endoplasmic reticulum stress. | (123) |

| Yart et al,

2022 |

|

| Genomic

reprogramming was accomplished via Activation of UPR subsequent to

cell fusion, augmenting the traits of polytene cancers cells and

in vitro development. | (124) |

| Chen et al,

2022 |

|

| Suppressing ENTPD5

can inhibit the proliferation and migration of PSMA-positive cells,

and impede the activation of the GRP78/p-eIF-2α/CHOP pathway. | (125) |

| Barez et al,

2020 |

|

| It stimulates

intra-endoplasmic reticulum stress of cystathionine-12/3 and

Bax/Bcl-2 proteins, restraining the proliferation of cancerous

cells. | (126) |

| Zundell et

al, 2021 |

|

| Simultaneously, the

IRE1a/XBP1 pathway demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in ovarian

carcinoma har-boring ARID1A mutations. | (127) |

| Ma et al,

2019 |

|

| Hypoglycemia and

metformin induce apoptosis of malignant cells via endoplasmic

reticulum stress. | (128) |

| Lin et al,

2021 |

|

| Suppressing

over-expression of CARM1 exhibits efficacy in ovarian cancer

treatment. | (129) |

| Xiao et al,

2022 |

|

| The WEE1 inhibitor

AZD1775 triggers cell apoptosis, and the combination of AZD1775

with the IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 synergistically exhibits

anticancer efficacy. | (130) |

| Zhang et al,

2019 |

|

| ANGII exhibits

inhibitory effects on endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces the

morphogenesis and migration of ovarian cancer spheroids. | (131) |

| Singla et

al, 2022 |

|

| Natural compounds

exhibit potent inhibitory properties against endoplasmic reticulum

stress. | (132) |

| Hong et al,

2022 |

|

| The mountain yam

flavonoids can catalyze endoplasmic reticulum stress. | (133) |

| Li et al,

2019 |

|

| Chiwanol I

molecules can induce the death of cancer cells by stimulating the

endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. | (134) |

| Bae et al,

2020 |

|

| Fucosterol elicits

endoplasmic reticulum stress, which subsequently suppresses the

proliferation of cancer cells. | (135) |

| Zhu et al,

2023 |

|

| Two mechanisms have

been identified to synergistically counteract the resistance of

SKOV3/DDP cells against cisplatin. | (136) |

| Bae et al,

2020 |

|

| The phlorotannins

in Fucus evanescens can inhibit ovarian cancer cell

proliferation by regulating endo-plasmic reticulum stress. | (138) |

| Kim and Ko,

2021 |

|

| In traditional

Chinese medicine, JIO17 induces apoptosis of cancer cells. | (139) |

| Abdullah et

al, 2022 |

|

| The mechanism by

which endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers the release and embrace

of calreticulin in ovarian cancer cells has been scrutinized. | (140) |

| Bi et al,

2021 |

|

|

Methanesulfonylamine can initiate

extranuclear stress to consequently trigger immunogenic cell death

in ovarian cancer. | (142) |

| Lau et al,

2020 |

|

| Taxol elicits

mechanical stress within the endoplasmic reticulum, leading to

immunogenic cell death in malignant cells. | (143) |

| Song et al,

2018 |

|

| Endoplasmic

reticulum stress IRE1a/XBP1 could potentially influence the

antitumor immunity of ovarian cancer patients by manipulating T

cells. | (145) |

| Cao et al,

2019 |

|

| The evidence

underscores the capacity to release T cell-mediated antitumor

immunity by blocking Chop or endoplasmic reticulum stress. | (146) |

Mitochondrial autophagy and ovarian

cancer

Mitochondria are organelles involved in cellular

energy production and biosynthetic processes (91). Both their content of mtDNA and

expression levels of relevant mitochondrial mRNAs are altered

during tumor progression, including the development of ovarian

cancer. Investigations have suggested that suppressing

mitochondrial autophagy may effectively mitigate the disease

progression of cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer (92,93).

The studies by Yu et al (96) demonstrated that inducing mutations

in the p62 UBA structural domain could regulate subcellular

localization of HK2 in A2780 ovarian cancer cells' mitochondria,

freeing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy to decrease

cell sensitivity to cisplatin. Similarly, Vianello et al

(94) observed an increase in the

content of the mitochondrial autophagy receptor BNIP3 in

cisplatin-resistant cells and in ovarian cancers resistant to

platinum chemotherapy. Additionally, Zhou et al (95) revealed that the potent potential of

a complex of glycosylated zinc (II)-cryptolepine could disrupt the

mitochondrial autophagy pathway and induce autophagy and apoptosis

in SKOV-3/DDP cells, highlighting its capability in developing

chemotherapeutic drugs against cisplatin-resistant SKOV-3/DDP

cells. Simultaneously, Yu et al (96) confirmed that ABT737, a potent

inhibitor of BCL2/BCLXL, could considerably elevate the

concentration of DRP1 in mitochondria, thus triggering the release

of Cytochrome C in mitochondria and their autophagy in SKOV3/DDP

cells. This finding underscores the suitability of targeting

antiapoptotic proteins of the BCL2 family as a novel therapeutic

strategy for treating patients with ovarian cancer with cisplatin

resistance.

Inducing mitochondrial autophagy may trigger the

process of programmed cell death in ovarian cancer cells at the

terminal stage. Chen et al (97) discovered that the antimicrobial

peptide pardaxin can stimulate PA-1 and SKOV3 cells to generate

excessive ROS. This surplus ROS accomplishes this by decreasing the

destruction of fusion proteins, declining the expression of

mitochondrial transporters 1/2 and L-/S-OPA1, inducing the

expression of fusion proteins DRP1 and FIS1 to enhance

mitochondrial fission rates, and at the same time initiating the

expression of autophagy-related proteins Beclin, p62 and LC3 to

stimulate the apoptotic pathway. Furthermore, Wang et al

(98) revealed that the

epoxidecolchicine H derived from the metabolism of Phomopsis

was capable of effectively increasing the ROS levels in cells,

weakening the mitochondrial membrane potential, thereby causing

damage to mitochondria, activating the mitochondrial autophagy

process. Concurrently, this compound is also able to mediate

apoptosis pathways associated with ER stress, further propelling

the apoptotic process of ovarian cancer A2780 cells (98). Katreddy et al (99) study identified that high malignant

epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) are frequently

overexpressed in solid tumors. The use of siRNA or synthetic EGFR

downregulating peptides (Herdegradin) can effectively downregulate

the expression of EGFR protein. Notably, this downregulation is

achieved by activating the mTORC2/Akt pathway, stimulating

selective mitochondrial autophagy, and achieving the selective

elimination of ovarian cancer cells (100).

Moderate suppression of mitochondrial autophagy may

restrain the tumor's metastatic capacity. Yuan et al

(101) indicated that mice exposed

to BPA/BPS are more susceptible to tumor metastasis, as BPA/BPS can

enhance the stem cell characteristics of ovarian cancer cells via a

non-normal PINK1/p53 mitochondrial autophagy process, and the

moderate suppression of mitochondrial autophagy can restrain this

augmentation effect.

Focusing on the mitochondrial autophagy, researchers

aim to elucidate novel targeted targets in ovarian cancer therapy.

Martinez-Outschoorn et al (102) have elucidated that BRCA1 tumor

suppressor gene deletion can instigate hydrogen peroxide

production, wherein the hydrogen peroxide produced by BRCA1-null

ovarian cancer cells stimulates NFB activation in stromal

fibroblasts, inducing oxidative stress and consequently triggering

mitochondrial autophagy and catabolic processes. Concurrently, MCT4

marker upregulation and Cav-1 expression loss also occur. Jin et

al (103) further discovered

that fucosylation of TGF-β1 augments Trk-like autophosphorylation

via the PI3K/Akt and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways, thereby enabling

ovarian cancer cell regulatory functions. This provides an

alternate research avenue for TGF-β1 targeting in ovarian cancer

therapy. Bae et al (104)

identified that campesterol influences mitochondrial function,

triggering excessive calcium accumulation and the creation of ROS,

thereby inflicting ER stress and thereby inhibiting ovarian cancer.

They observed in experimental settings that campesterol amplified

the efficacy of conventional anticancer drugs, presenting potential

as a novel drug for future treatment of ovarian cancer; however,

this enhanced anticancer effect requires further study.

In summary, mitochondrial autophagy plays a

substantial role in ovarian cancer therapy. It not only enhances

the sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs and

reduces drug resistance by inhibiting mitochondrial autophagy; but

also triggers mitochondrial autophagy to drive ovarian cancer cell

apoptosis. Moreover, manipulating mitochondrial dynamics, enhancing

mitochondrial autophagy, or prodigiously initiating ROS generation

and suppressing mitochondrial autophagy can ultimately lead to

ovarian cancer cell demise. Hence, regulating the mechanisms of

mitochondrial autophagy may be conjectured as a potential strategy

for ovarian cancer therapy.

ER stress and ovarian cancer

Based on the presence or absence of ribosomes at the

cisternal face of cell membranes, ER can be classified as RER and

SER. These constitute distinct spatial domains that are

nevertheless integrally related constructs (105). Moreover, the ER can also be

classified based on its membrane structure features. These

structures encompass the outer nuclear membrane, flared ER pools,

and a polygonal pipeline system composed of triangular junction

rings (106).

The ER lies in proximity to numerous other

organelles and boasts extensive volumes within cells, the magnitude

of which is contingent upon the type of cell. Notably, the

interaction with mitochondria merits special mention. Given the

pivotal role of mitochondria in organs (specifically their function

during apoptosis), this association assumes paramount importance

(107,108). In fact, this connection between

the ER and mitochondria is predominantly mediated by the MAM

(109). Additionally, MAM

synergizes with the cell membrane to maintain its stability and

growth. This interplay is controlled by Ca2+ levels and

several proteins, including stromal interaction molecule 1 located

in the ER and calcium release-activated calcium channel protein1

residing in the cell membrane (110). Notably, the ER appears to also

partake in autophagy processes, as observed by linking endocytic

vesicle systems (111). When

contacted with specific ER assemblies known as sub-Golgi bodies,

one of the core structures of autophagosomes-the phagophore will

proliferate and mature into a mature autophagosome (112,113).

Recent scientific literature from recent years

suggests that ER stress can significantly diminish the resistance

of ovarian cancer cells. Cheng et al (114) discovered in their research that

mitochondrial protease OMA1 not only triggers the morphogenesis of

mitochondrial structures by cleaving OPA1 but also significantly

reduces the drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells by integrating

ER stress through its interaction with the PHB2/OMA1/DELE1 pathway.

Additionally, Jung et al (115) identified that DPP23, functioning

as an initiator of ER stress, effectively combats ovarian cancer

resistance. Xu et al (116)

revealed that PHLDA1 fine-tunes the apoptotic sensitivity of

ovarian cancer cells via the ER stress response process. Kim and

Lee (117) corroborated that

6-gingerol induces ER stress in ovarian cancer cells and

successfully overcomes resistance to gefitinib, thus providing a

novel strategy for treating ovarian cancer using the combination of

gefitinib and 6-gingerol. Lastly, Bahar et al (118) suggested that the combination of

PARPis and cis-diminution of cis-OC cells may present an

efficacious method to broaden therapeutic potential in response to

ER stress, thereby overcoming platinum chemotherapy resistance in

OC and PARPi cross-resistance.

ER stress is progressively emerging as a novel

treatment approach for ovarian cancer (119). Rezghi et al (120) demonstrated using experimental

evidence that miR-3c-1-1p regulates XBP30/CHOP/BIM-mediated ER

stress, suppresses transcription of XBP2 in ovarian cancer cells

and consequently triggers the activation of the apoptosis pathway.

Kong et al (121) utilized

platinum (IV) prodrug and near infrared II (NIR II) photothermal

agent IR1048 as the foundation, generating enhanced ER stress

through formation of reduced-sensitive polymer nanoparticles to

amplify therapeutic effects against ovarian cancer. Wang et

al (122) found that during

their research, Erythropoietinaxin 2A9 (EpoxiDRESSIN H), was

capable of triggering apoptosis pathways related to mitochondria

and ER stress, thereby stimulating apoptosis of human ovarian

cancer A2780 cells further. Similarly, Wang et al (123) reported that DWP05195 could induce

ER stress via the ROS-p38-CHOP pathway in human ovarian cancer

cells, triggering cell apoptosis. Yart et al (124) discovered that activation of UPR by

cellular fusions increases the generation of polyploid multi-cancer

cells in vitro and bestows them with new attributes, and

also established that regulation of UPR in patients with ovarian

cancer could represent an intriguing and potent therapeutic

strategy. Chen et al (125)

efficiently suppressed proliferation and migration of prostate

specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-positive cells by inhibiting

ENTPD5 and at the same time, blocked the activation of

GRP78/p-eIF-2α/CHOP pathway, providing potential effective

therapeutic targets for investigating prostate cancer treatment.

Barez et al (126)

confirmed in the context of studying IRE1a inhibitor STF-083010

that suppressing caspases-12/3 and Bax/Bcl-2 proteins could

effectively inhibit ovarian cancer proliferation, revealing

STF-083010 as a novel potential therapeutic target for treating

ovarian cancer cells associated with ER stress. Moreover, in

addition to IRE1a inhibitors, Zundell et al (127) posited that IRE1a/XBP1 pathway

carries innovative therapeutic potential against ARID1A-mutated

ovarian cancers, providing scientific basis for drugs concurrently

utilizing the IRE1a/XBP1 pathway. Ma et al (128) identified that under low glucose

and metformin's effect, ANGII triggers inhibited ER stress,

inducing the formation and migration of ovarian cancer spheroids.

By contrast, Lin et al (129) found that this pathway had

comparable effects on ovarian cancer cells expressing CARM1 and

could achieve the therapeutic objective by decreasing overexpressed

CARM1. Additionally, Xiao et al (130) used WEE1 inhibitor AZD1775 to

stimulate PERK, thereby triggering apoptosis of ovarian cancer

cells, and in clinical practice, combined AZD1775 with IRE1α

inhibitor MKC8866 to achieve synergistic anti-ovarian cancer

effects. Zhang et al (131)

observed that ANGII regulates lipid desaturation, triggering

suppression of ER stress, resulting in the formation and migration

of ovarian cancer spheroids.

Singla et al (132) asserted that naturally occurring

compounds play a pivotal role in regulating ER stress, further

demonstrating that various such natural substances, such as

quercetin, curcumin and resveratrol, exhibit effective ER stress

inhibitor effects in the context of ovarian cancer. Hong et

al (133) employed the action

of mountain heteroflavone complex extracted from tricuspid fruit on

ovarian cancer cells, observing apoptosis of cancer cells;

subsequent studies revealed that mountain heteroflavone can

interfere with mitochondrial co-localization through inhibiting the

PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways and initiate ER stress. Li et al

(134) identified cucurbitacin I

as inducing death of ovarian cancer cells via the ER stress

pathway. Bae et al (135)

discovered that fucosterol (present in algae) could induce

mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress, thereby suppressing the

proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Zhu et al (136) elucidated that naringin could

regulate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway to suppress SKOV3/DDP

cell autophagy, and also facilitate SKOV3/DDP cell apoptosis by

targeting ER stress; these two mechanisms synergistically

counteract tolerance to cisplatin exhibited by SKOV3/DDP cells.

This experimental outcome strongly supports the extensive

application prospects of natural compounds in treating ovarian

cancer therapies (137). Bae et

al (138) discerned the

regulatory effect of fucosanglioside in maqueigao (Centricellularis

longicaudata), a natural compound, on ER stress to restrain the

proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Kim and Ko (139) also posited that JIO17 from

traditional Chinese medicine can induce ovarian cancer cell

apoptosis through the NOX4/PERK/CHOP pathway.

Abdullah et al (140) investigated the mechanism by which

ER stress induces release and binding of calreticulin in ovarian

cancer cells, hypothesizing that calreticulin has a profound

connection with immunogenic cell death in ovarian cancer cells;

meanwhile, existing experiments have confirmed the value of

calreticulin in prognostic evaluation and prediction (141), and future research remains

necessary. Bi et al (142)

triggered immunogenic cell death in ovarian cancer through

initiating ER stress using a mitochondrial uncoupling agent

benzylamine, and remarkably inhibited tumor progression.

Separately, Lau et al (143) discovered that paclitaxel triggers

generation of ER stress through the TLR4/IKK2/SNARE pathway,

leading to immunogenic cell death in ovarian cancer cells,

suggesting a higher occurrence rate of immunogenic cell death in

ovarian cancer and therefore possessing significant research

significance; the importance of CALR as a crucial indicator for

paclitaxel chemotherapy in ovarian cancer was also underscored.

Beyond addressing mortality, the immune system also

plays a significant role in tumor cells (144,145). For instance, Song et al

(145) discovered that ER stress

IRE1a/XBP1 potentially influences T cell metabolic adaptability and

antitumor potency, thereby influencing the antitumor immunity of

patients with ovarian cancer, providing a novel therapeutic

approach in immunotherapy. Furthermore, Cao et al (146) elucidated the central function of

Chop in tumor-induced dysfunction of CD8 T cells, and the potential

for therapeutic efficacy to release T cell-mediated antitumor

immunity through blocking Chop or ER stress.

Conclusions

In light of the comprehensive factors, MAM carves a

unique functional role as a link between the mitochondria and ER.

It exhibits superior performance during mitochondrial autophagy and

ER stress response. It is capable of sequentially regulating these

two crucial processes to suppress the malignant proliferation,

migration and drug resistance ability of ovarian cancer. Notably,

its intrinsic regulatory mechanism implicates numerous proteins,

some of which may precisely be key players in a certain disease's

progression. Consequently, meticulously exploring its potential

application value and vast research prospects warrants more time

and effort. Nonetheless, the present review elucidated the

correlation between mitochondrial autophagy, ER stress and MAMs,

with an expectation of conducting more thorough research on this

topic in subsequent efforts. Furthermore, given that MAMs have not

been extensively validated in ovarian cancer-related studies, the

integrated analysis related to ovarian cancer outcomes remains

relatively thin. It is expected that in future research endeavors,

such research can be more profoundly conducted.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Hunan Provincial Nature

Foundation (2022JJ30035), Key Guiding Project of Hunan Provincial

Health Commission (202305017379), Key Project of Hunan Provincial

Health Commission (20230589), National College Student Innovation

and Entrepreneurship Program Training Project (S202310541063),

Hunan College Student Innovation (S202310541063) and

Entrepreneurship Program Training Project (S202310541063).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JHZ and YLX were involved in the writing of the

original manuscript. YFD and JZ completed the original manuscript.

HPL completed manuscript revisions. WJP was involved in drawing the

diagram. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wallace DC: A mitochondrial paradigm of

metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: A dawn for

evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 39:359–407. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Copeland DE and Dalton AJ: An association

between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum in cells of the

pseudobranch gland of a teleost. J Biophys Biochem Cytol.

5:393–396. 1959. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS,

Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA and Pozzan T: Close contacts with

the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+

responses. Science. 280:1763–1766. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wu H, Carvalho P and Voeltz GK: Here,

there, and everywhere: The importance of ER membrane contact sites.

Science. 361:eaan58352018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lev S: Nonvesicular lipid transfer from

the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

4:a0133002012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hoppins S and Nunnari J: Cell biology.

Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis-the ER connection. Science.

337:1052–1054. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Belosludtsev KN, Dubinin MV, Belosludtseva

NV and Mironova GD: Mitochondrial Ca2+ transport: Mechanisms,

molecular structures, and role in cells. Biochemistry (Mosc).

84:593–607. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Várnai P, De

Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T and Rizzuto

R: Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and

mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 175:901–911. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A,

Pozzan T and Pizzo P: On the role of mitofusin 2 in endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria tethering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

114:E2266–E2267. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gibellini F and Smith TK: The Kennedy

pathway-de novo synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine and

phosphatidylcholine. IUBMB Life. 62:414–428. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Puglielli L, Konopka G, Pack-Chung E,

Ingano LA, Berezovska O, Hyman BT, Chang TY, Tanzi RE and Kovacs

DM: Acyl-coenzyme A: Cholesterol acyltransferase modulates the

generation of the amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Cell Biol. 3:905–912.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

El Alwani M, Wu BX, Obeid LM and Hannun

YA: Bioactive sphingolipids in the modulation of the inflammatory

response. Pharmacol Ther. 112:171–183. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nikolova-Karakashian M, Karakashian A and

Rutkute K: Role of neutral sphingomyelinases in aging and

inflammation. Subcell Biochem. 49:469–486. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M,

DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J and Voeltz GK: ER tubules mark sites of

mitochondrial division. Science. 334:358–362. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Murley A, Sarsam RD, Toulmay A, Yamada J,

Prinz WA and Nunnari J: Ltc1 is an ER-localized sterol transporter

and a component of ER-mitochondria and ER-vacuole contacts. J Cell

Biol. 209:539–548. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ishihara N, Eura Y and Mihara K: Mitofusin

1 and 2 play distinct roles in mitochondrial fusion reactions via

GTPase activity. J Cell Sci. 117:6535–6546. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ainbinder A, Boncompagni S, Protasi F and

Dirksen RT: Role of mitofusin-2 in mitochondrial localization and

calcium uptake in skeletal muscle. Cell Calcium. 57:14–24. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Basso V, Marchesan E, Peggion C,

Chakraborty J, von Stockum S, Giacomello M, Ottolini D, Debattisti

V, Caicci F, Tasca E, et al: Regulation of ER-mitochondria contacts

by Parkin via Mfn2. Pharmacol Res. 138:43–56. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Okamoto K and Shaw JM: Mitochondrial

morphology and dynamics in yeast and multicellular eukaryotes. Annu

Rev Genet. 39:503–536. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Trojel-Hansen C and

Kroemer G: Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and

death. Circ Res. 111:1198–1207. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Iwasawa R, Mahul-Mellier AL, Datler C,

Pazarentzos E and Grimm S: Fis1 and Bap31 bridge the

mitochondria-ER interface to establish a platform for apoptosis

induction. EMBO J. 30:556–568. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Area-Gomez E and Schon EA: On the

pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: The MAM hypothesis. FASEB J.

31:864–867. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang B, Nguyen M, Chang NC and Shore GC:

Fis1, Bap31 and the kiss of death between mitochondria and

endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 30:451–452. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

MacAskill AF and Kittler JT: Control of

mitochondrial transport and localization in neurons. Trends Cell

Biol. 20:102–112. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Upton JP, Austgen K, Nishino M, Coakley

KM, Hagen A, Han D, Papa FR and Oakes SA: Caspase-2 cleavage of BID

is a critical apoptotic signal downstream of endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Mol Cell Biol. 28:3943–3951. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Puthalakath H, O'Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L,

Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin

J, Motoyama N, et al: ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating

BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 129:1337–1349. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li J, Lee B and Lee AS: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress-induced apoptosis: Multiple pathways and

activation of p53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and

NOXA by p53. J Biol Chem. 281:7260–7270. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Iwasawa R, Mahul-Mellier AL, Datler C,

Pazarentzos E and Grimm S: Fis1 and Bap31 bridge the

mitochondria-ER interface to establish a platform for apoptosis

induction. EMBO J. 30:556–568. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Area-Gomez E and Schon EA: On the

pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: The MAM hypothesis. FASEB J.

31:864–867. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang B, Nguyen M, Chang NC and Shore GC:

Fis1, Bap31 and the kiss of death between mitochondria and

endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 30:451–452. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Siskind LJ, Kolesnick RN and Colombini M:

Ceramide channels increase the permeability of the mitochondrial

outer membrane to small proteins. J Biol Chem. 277:26796–26803.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Coleman RA, Lewin TM, Van Horn CG and

Gonzalez-Baró MR: Do long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases regulate fatty

acid entry into synthetic versus degradative pathways? J Nutr.

132:2123–2126. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Larsen BD and Sørensen CS: The

caspase-activated DNase: Apoptosis and beyond. FEBS J.

284:1160–1170. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

de Brito OM and Scorrano L: Mitofusin 2

tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 456:605–610.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mazure NM: VDAC in cancer. Biochim Biophys

Acta Bioenerg. 1858:665–673. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Vinay Kumar C, Kumar KM, Swetha R, Ramaiah

S and Anbarasu A: Protein aggregation due to nsSNP resulting in

P56S VABP protein is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

J Theor Biol. 354:72–80. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Formosa LE and Ryan MT: Mitochondrial

fusion: Reaching the end of mitofusin's tether. J Cell Biol.

215:597–598. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Di Mattia T, Wilhelm LP, Ikhlef S,

Wendling C, Spehner D, Nominé Y, Giordano F, Mathelin C, Drin G,

Tomasetto C and Alpy F: Identification of MOSPD2, a novel scaffold

for endoplasmic reticulum membrane contact sites. EMBO Rep.

19:e454532018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lim Y, Cho IT, Schoel LJ, Cho G and Golden

JA: Hereditary spastic paraplegia-linked REEP1 modulates

endoplasmic reticulum/mitochondria contacts. Ann Neurol.

78:679–696. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Calì T, Ottolini D, Negro A and Brini M:

α-Synuclein controls mitochondrial calcium homeostasis by enhancing

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions. J Biol Chem.

287:17914–17929. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu Y, Ma X, Fujioka H, Liu J, Chen S and

Zhu X: DJ-1 regulates the integrity and function of ER-mitochondria

association through interaction with IP3R3-Grp75-VDAC1. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 116:25322–25328. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Stoica R, Paillusson S, Gomez-Suaga P,

Mitchell JC, Lau DH, Gray EH, Sancho RM, Vizcay-Barrena G, De Vos

KJ, Shaw CE, et al: ALS/FTD-associated FUS activates GSK-3β to

disrupt the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and ER-mitochondria

associations. EMBO Rep. 17:1326–1342. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Thoudam T, Ha CM, Leem J, Chanda D, Park

JS, Kim HJ, Jeon JH, Choi YK, Liangpunsakul S, Huh YH, et al: PDK4

augments ER-mitochondria contact to dampen skeletal muscle insulin

signaling during obesity. Diabetes. 68:571–586. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

D'Eletto M, Rossin F, Occhigrossi L,

Farrace MG, Faccenda D, Desai R, Marchi S, Refolo G, Falasca L,

Antonioli M, et al: Transglutaminase type 2 regulates

ER-mitochondria contact sites by interacting with GRP75. Cell Rep.

25:3573–3581.e4. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wu S, Lu Q, Wang Q, Ding Y, Ma Z, Mao X,

Huang K, Xie Z and Zou MH: Binding of FUN14 domain containing 1

with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in

mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes maintains

mitochondrial dynamics and function in hearts in vivo. Circulation.

136:2248–2266. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang W, Siraj S, Zhang R and Chen Q:

Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and

protects the heart from I/R injury. Autophagy. 13:1080–1081. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kuang Y, Ma K, Zhou C, Ding P, Zhu Y, Chen

Q and Xia B: Structural basis for the phosphorylation of FUNDC1 LIR

as a molecular switch of mitophagy. Autophagy. 12:2363–2373. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen M, Chen Z, Wang Y, Tan Z, Zhu C, Li

Y, Han Z, Chen L, Gao R, Liu L and Chen Q: Mitophagy receptor

FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy.

12:689–702. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wu W, Li W, Chen H, Jiang L, Zhu R and

Feng D: FUNDC1 is a novel mitochondrial-associated-membrane (MAM)

protein required for hypoxia-induced mitochondrial fission and

mitophagy. Autophagy. 12:1675–1676. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wang XL, Feng ST, Wang YT, Yuan YH, Li ZP,

Chen NH, Wang ZZ and Zhang Y: Mitophagy, a form of selective

autophagy, plays an essential role in mitochondrial dynamics of

Parkinson's disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 42:1321–1339. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gong Y, Luo Y, Liu S, Ma J, Liu F, Fang Y,

Cao F, Wang L, Pei Z and Ren J: Pentacyclic triterpene oleanolic

acid protects against cardiac aging through regulation of mitophagy

and mitochondrial integrity. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1868:1664022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhou H, Wang J, Zhu P, Zhu H, Toan S, Hu

S, Ren J and Chen Y: NR4A1 aggravates the cardiac microvascular

ischemia reperfusion injury through suppressing FUNDC1-mediated

mitophagy and promoting Mff-required mitochondrial fission by CK2α.

Basic Res Cardiol. 113:232018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Simmen T, Aslan JE, Blagoveshchenskaya AD,

Thomas L, Wan L, Xiang Y, Feliciangeli SF, Hung CH, Crump CM and

Thomas G: PACS-2 controls endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria

communication and Bid-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 24:717–729. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Werneburg NW, Bronk SF, Guicciardi ME,

Thomas L, Dikeakos JD, Thomas G and Gores GJ: Tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) protein-induced

lysosomal translocation of proapoptotic effectors is mediated by

phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-2 (PACS-2). J Biol

Chem. 287:24427–24437. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Köttgen M, Benzing T, Simmen T, Tauber R,

Buchholz B, Feliciangeli S, Huber TB, Schermer B, Kramer-Zucker A,

Höpker K, et al: Trafficking of TRPP2 by PACS proteins represents a

novel mechanism of ion channel regulation. EMBO J. 24:705–716.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Myhill N, Lynes EM, Nanji JA,

Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Fei H, Carmine Simmen K, Cooper TJ, Thomas G

and Simmen T: The subcellular distribution of calnexin is mediated

by PACS-2. Mol Biol Cell. 19:2777–2788. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Han S, Zhao F, Hsia J, Ma X, Liu Y, Torres

S, Fujioka H and Zhu X: The role of Mfn2 in the structure and

function of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial tethering in vivo.

J Cel Sci. 134:jcs2534432021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Leal NS, Schreiner B, Pinho CM, Filadi R,

Wiehager B, Karlström H, Pizzo P and Ankarcrona M: Mitofusin-2

knockdown increases ER-mitochondria contact and decreases amyloid

β-peptide production. J Cel Mol Med. 20:1686–1695. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Li J, Qi F, Su H, Zhang C, Zhang Q, Chen

Y, Chen P, Su L, Chen Y, Yang Y, et al: GRP75-faciliated

mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) integrity controls

cisplatin-resistance in ovarian cancer patients. Int J Biol Sci.

18:2914–2931. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Barroso-González J, Auclair S, Luan S,

Thomas L, Atkins KM, Aslan JE, Thomas LL, Zhao J, Zhao Y and Thomas

G: PACS-2 mediates the ATM and NF-κB-dependent induction of

anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in response to DNA damage. Cell Death Differ.

23:1448–1457. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhou H, Zhu P, Wang J, Toan S and Ren J:

DNA-PKcs promotes alcohol-related liver disease by activating

Drp1-related mitochondrial fission and repressing FUNDC1-required

mitophagy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 4:562019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A,

Pozzan T and Pizzo P: Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

112:E2174–E2181. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Li J, Qi F, Su H, Zhang C, Zhang Q, Chen

Y, Chen P, Su L, Chen Y, Yang Y, et al: GRP75-faciliated

mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) integrity controls

cisplatin-resistance in ovarian cancer patients. Int J Biol Sci.

18:2914–2931. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Chen Y and Dorn GW II:

PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling

damaged mitochondria. Science. 340:471–475. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Cao Y, Chen Z, Hu J, Feng J, Zhu Z, Fan Y,

Lin Q and Ding G: Mfn2 regulates high glucose-induced MAMs

dysfunction and apoptosis in podocytes via PERK pathway. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 9:7692132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Modi S, López-Doménech G, Halff EF,

Covill-Cooke C, Ivankovic D, Melandri D, Arancibia-Cárcamo IL,

Burden JJ, Lowe AR and Kittler JT: Miro clusters regulate

ER-mitochondria contact sites and link cristae organization to the

mitochondrial transport machinery. Nat Commun. 10:43992019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hernández-Alvarez MI, Sebastián D, Vives

S, Ivanova S, Bartoccioni P, Kakimoto P, Plana N, Veiga SR,

Hernández V, Vasconcelos N, et al: Deficient endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine transfer causes liver

disease. Cell. 177:881–895. e172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Baker N, Patel J and Khacho M: Linking

mitochondrial dynamics, cristae remodeling and supercomplex

formation: How mitochondrial structure can regulate bioenergetics.