Introduction

Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of

cancer-related deaths. The GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates of cancer

incidence and mortality prepared by the International Agency for

Research on Cancer reported an estimated 1.8 million deaths from

lung cancer, representing 18% of all cancer-related deaths, in 2020

worldwide (1). Lung cancer staging

is currently performed using the 8th edition of the

tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification (2). The World Health Organization (WHO)

classification of tumors was revised in 2021 (3) prior to the 9th edition of the TNM

classification.

Lung adenocarcinoma, a form of non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC), one of the main subtypes of lung cancer, consists

of adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma

(MIA), invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) and invasive

non-mucinous adenocarcinoma (INMA). INMA is classified into three

histological grades. Various agents have been developed for the

treatment of NSCLC (4–8). For patients with very early-stage

NSCLC, reduced surgery such as segmentectomy or partial resection

is performed (9–11). However, recurrence is a challenge in

these patients, and treatment of cases with recurrence is limited.

Therefore, the identification of prognostic markers to predict

recurrence is critical.

Several biomarkers for predicting therapeutic

efficacy in patients with lung cancer have been identified, such as

driver gene mutations for various molecular-targeted drugs and

programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and tumor proportion score (TPS)

for programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody therapy. Loss of function

alterations in RB1, TP53 and STK11/LKB1 have also

previously attracted attention as prognostic biomarkers for drug

therapy (12,13). However, the development of

biomarkers for recurrence in surgically resected NSCLC has not

progressed. The most accurate prognostic factor for surgically

resected early-stage NSCLC is the TNM classification. The

International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Pathology

Committee proposed histological grade as a prognostic factor in

INMA. The combination of predominant and worst histological

patterns significantly improved patient outcome prediction in

early-stage resected lung adenocarcinomas, and it was superior to

mitotic count, nuclear grade, cytological grade, tumor spread

through air spaces and necrosis (14). While in breast cancer, for example,

genomic assays are used to predict recurrence and determine the

administration of postoperative adjuvant therapy (15), treatment decisions in lung cancer

depend on the TNM classification.

Casein kinase 2 (CK2) is a serine/threonine kinase

that is essential for eukaryote cell survival. CK2α is the

catalytic subunit of CK2. The first study linking CK2 and

malignancy was in CK2α transgenic mice, which were reported to

develop T lymphomas (16). CK2 is

considered one of the driver kinases of carcinogenesis, and

overexpression of CK2α has been reported in various types of cancer

(17–19). Elevated nuclear CK2α protein levels

were observed in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck

(20) and breast cancer (21), and its high expression was

associated with poor clinical outcomes. CK2 regulates various

hallmarks of cancer (22),

particularly via its association with nuclear transcription factors

and its involvement in ribosomal gene transcription during rRNA

synthesis (23,24). Therefore, its localization in the

nucleus, especially in the nucleolus, is considered to be important

for its function (23,24). It was previously found that the

nucleolar localization of CK2α was a potential poor prognostic

factor in invasive breast carcinoma (25). Nucleolar CK2α is involved in

inflammatory pathways (26).

Cancers are also characterized by an increased inflammatory burden

(27,28). Thus, studying nucleolar CK2α in lung

cancer is pertinent in the present study. CK2 is known to play a

critical role in both innate and adaptive immune cells (29). CK2 is involved in i) activating

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by phosphorylating AKT at S129 to induce

proliferation and cancer metastasis (30,31);

ii) activating the NF-kB signaling pathway by phosphorylating p65

at S529 (32); and iii) activating

the JAK/STAT pathway by phosphorylating JAK, to induce inflammation

and immune response (33–35). CK2 inhibition by using low molecular

weight inhibitor demonstrated potent antitumor effects in

combination with immunotherapy. The inhibitor resulted in a

decrease of tumor-associated macrophages and polymorphonuclear

myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment

(36). In pan-cancer analysis, CK2

alpha protein 1 expression had positive correlations with

M1-macrophages and fibroblasts, and negative correlations with

CD8+ T cells and NK cells (37).

In the present study, the relationship between CK2α

nucleolar localization and patient prognosis was examined. The

subcellular localization of CK2α in surgically resected lung

adenocarcinomas was determined by immunohistochemistry. Focus was

addressed on adenocarcinoma, which is the same histological type as

the breast carcinoma in our previous study (25) and the most frequent type of

NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Antibody generation

For the production of recombinant human protein

kinase CK2α (gene name CSKN2A1), the cDNA was subcloned into

the pGEX-4T plasmid (Amersham; Cytiva). The GST fusion protein was

expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) and then

purified as a GST tag-free protein to the single band level

(24). A total of four BALB/c BDF1

female mice (6 weeks old) which were housed (20°C, auto-fresh

ventilation of 14–15 times/h, 12/12-h light/dark cycle) at

Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd., according to the

Guideline and the Law for the Human Treatment and Management of

Animals, were immunized with 50 µg of full-length CK2α five times

in weekly intervals. Sequential screening of mouse hybridoma clones

was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay coated with

serial dilution of recombinant full-length human CK2α or CK2α', and

then western blotting by using 20 µg of cultured 293 cell cytosolic

lysates with or without exogenously expressed human CK2α, which

were solubilized by the lysis buffer containing 10 mM Hepes (pH

7.4), 20 mM NaCl, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1.5 mM

MgCl2, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 1 µg/ml of

aprotinin, 0.5 mM PMSF, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gels and

transferred to PVDF membrane. Briefly, the detection of antigen,

CK2α, was evaluated as follows: PVDF membrane was blocked with 5%

BSA in Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl for 30 min at room

temperature; then primary anti-CK2α monoclonal antibody as purified

IgG was used at the concentration of 0.1 µg/ml for 1 h at room

temperature, followed by incubation with secondary anti-mouse

IgG-peroxidase conjugated antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. 6789; Abcam)

for 30 min, and detected by Chemiluminescent Detection Kit (cat.

no. 32209; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as previously described

(24). A total of >6 clones with

high affinity and specificity to CK2α both in vitro and

in vivo that did not cross-react with CK2α' were selected

(Fig. S1). The protein A-purified

IgG fraction derived from the hybridoma clone 6A3, subclass mouse

IgG2b κ, was used in the present study.

Patients

A total of 118 patients (64 males and 54 females)

with lung adenocarcinoma who had undergone pulmonary lobectomy as

complete resection between January 2014 and December 2018 at

Fukushima Medical University Hospital (Fukushima, Japan) were

enrolled. Median age was 69.5 (range; 40–86) years old. The

patients did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or

immunotherapy before surgery. Pathological staging was evaluated

using the International Staging System for Lung Tumors, 8th edition

(2,38). Up to 2016, patients were

re-diagnosed by pathologists using the 8th edition of the TNM

classification. All patients were pathologically reclassified by

pathologists following the WHO Classification of Tumors: Thoracic

Tumors 5th Edition (3). For INMA,

histological grade was evaluated and categorized by pathologists as

follows: Grade 1, well-differentiated; grade 2, moderately

differentiated; and grade 3, poorly differentiated (3,14). The

present study was conducted according to the guidelines of the

Declaration of Helsinki and was approved (approval no. 30113;

August 30, 2022) by the institutional Ethics Committee of Fukushima

Medical University (Fukushima, Japan). Verbal informed consent was

obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

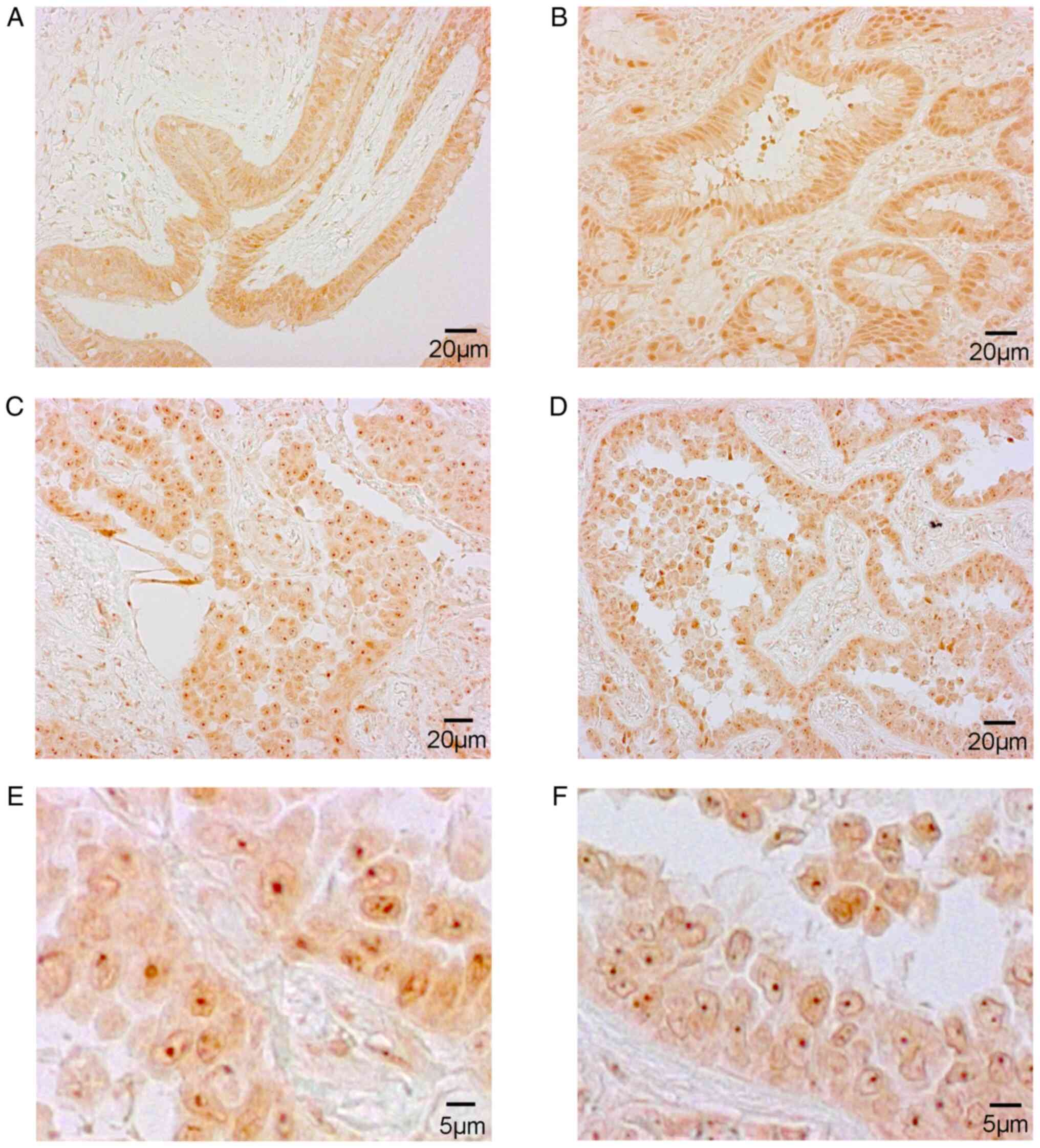

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tumor specimens were cut into 4-µm

thick sections. For rehydration, Tissue-Tek Prisma® Plus

was used (Sakura FineTek Japan Co. Ltd.) following the

manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, by descending concentration of

ethanol from 99.5, 95, to 80% in every 3 min. After rehydration and

antigen retrieval, the sections were autoclaved at 121°C for 10 min

in 10 mM citrate-Na buffer at pH 8.0. Following incubation with

1:200 normal serum (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 30 min at room

temperature, the sections were incubated at 4°C with primary

monoclonal antibody against CK2α (6A3) overnight at a concentration

of 0.1 µg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine

serum albumin (cat. no. A8531; MilliporeSigma). The primary

antibody was detected using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex

method. Goat anti-mouse biotinylated IgG (H + L; 1:250; cat. no.

BA-9200; Vector Laboratories, Inc.) was incubated at room

temperature for 30 min, followed by VECTASTAIN ABC-HRP Kit (cat.

no. PK-6100; Vector Laboratories Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The sections were not counterstained with

hematoxylin to avoid false positive staining of nucleoli. After

incubation with diaminobenzidine (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) for

40–80 sec, the sections were mounted on glass slides. The

immunoreactivity of each specimen was scored independently by two

pathologists using a light microscope based on the random selection

of at least three tumor areas. CK2 staining of each specimen was

evaluated as follows (25): I,

nuclear staining was not visible, but cell bodies were stained; II,

nuclear staining was more obvious compared with cytosolic staining;

III, nuclear staining was more intense than in category II; IV,

positive nucleolar staining was evident and nuclear staining was

observed; and V, staining was mostly confined to nucleoli, but

without intense staining of the nucleoplasm.

In some analyses, patients were categorized into two

groups: Patients with nucleolar CK2α staining (categories IV and V)

and those without nucleolar CK2α staining (categories I–III).

The EML4-ALK fusion protein was evaluated in 68

patients using the Nichirei Histofine ALK iAEP Kit (Nichirei

Biosciences Inc.) (39). PD-L1 TPS

was evaluated in 43 patients using a PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx

immunohistochemistry assay on the Dako Autostainer Link 48 at SRL,

Inc. PD-L1 TPS was defined as the percentage of viable tumor cells

with partial or complete membrane staining for PD-L1 (40). EGFR mutations were evaluated

in surgically resected tissue from 82 patients using the cobas EGFR

Mutation Test v2 at SRL, Inc (41).

These 68, 43 and 82 patients were randomly selected from the 118

patients.

Statistical analysis

The associations between nucleolar CK2α expression

and pathological parameters (pathological stage, histological type

and histological grade) were examined. Survival curves were created

using the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed in patients with and

without nucleolar CK2α staining using the log-rank test which was

performed using GraphPad Prism software v8.4.3 (GraphPad Software,

Inc.; Dotmatics). Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall

survival (OS) were defined as the time from surgery to relapse and

the time from surgery to death from any cause, respectively. The

Cox proportional regression model using the forward stepwise

likelihood ratio method was performed to identify prognostic

factors of survival using SPSS software v29 (IBM Corp.). The JMP

Pro v17.0 platform (JMP Statistical Discovery LLC) was used to

examine the relationship between nucleolar CK2α expression and

recurrence in early-stage patients.

Results

CK2 localization in nuclei of cancer

cells in lung adenocarcinoma

The characteristics of the 118 lung adenocarcinoma

patients included in the present study are included in Table I. The intracellular localization of

CK2 in tumor samples was categorized as aforementioned.

Representative images of the five categories of CK2α expression are

shown in Fig. 1.

| Table I.Patient characteristics (N=118). |

Table I.

Patient characteristics (N=118).

|

Characteristics | Value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range) | 69.5 (40–86) |

| Sex

(male/female) | 64/54 |

| Smoking status |

|

|

Never | 50 |

| Former

or current | 68 |

| Pathological stage

(8th) |

|

| 0 | 15 |

|

IA1 | 35 |

|

IA2 | 21 |

|

IA3 | 14 |

| IB | 13 |

|

IIA | 2 |

|

IIB | 10 |

|

IIIA | 8 |

| Histological

type |

|

|

Adenocarcinoma in

situ | 15 |

|

Minimally invasive

adenocarcinoma | 16 |

|

Invasive mucinous

adenocarcinoma | 5 |

|

Invasive non-mucinous

adenocarcinoma | 82 |

| Histological

grade |

|

| 1 | 11 |

| 2 | 42 |

| 3 | 29 |

| Epidermal growth

factor receptor mutation |

|

| Ex 19

del | 18 |

| Ex 21

L858R | 20 |

| Ex 19

del + T790M | 1 |

| Ex 21

L858R + T790M | 1 |

| Ex 21

L861Q | 1 |

| Ex 21

insertion | 1 |

| ND | 40 |

| NA | 36 |

| Anaplastic lymphoma

kinase rearrangement |

|

|

Positive | 2 |

| ND | 66 |

| NA | 50 |

| Programmed

death-ligand 1 tumor proportion score |

|

|

<1% | 16 |

|

1–49% | 18 |

|

≥50% | 9 |

| NA | 75 |

CK2α staining was localized to the nucleoli of

cancer cells (category IV and V) in 60 of 118 lung adenocarcinoma

tumors (50.8%; Table SI). There

were no category I specimens in the patient group. The relationship

between CK2α staining status, nucleolar CK2α status and

histopathological diagnosis is summarized in Table II. There were no apparent

associations between CK2α staining status or nucleolar CK2α status

and pathological stage, histological type and histological grade in

INMA, the main subtype of lung adenocarcinoma.

| Table II.Relationship between CK2α staining

status and nucleolar CK2α status with histopathological

diagnosis. |

Table II.

Relationship between CK2α staining

status and nucleolar CK2α status with histopathological

diagnosis.

|

| Pathological

stage | Histological

type |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

| 0 | I | II | III | AIS | MIA | IMA | INMA |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Histological

grade |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|

| CK2α staining |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 3 | 7 | 37 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 16 | 12 |

| 4 | 5 | 28 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 18 | 8 |

| 5 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| Nucleolar CK2α |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| – | 8 | 43 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 15 |

| + | 7 | 40 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 25 | 14 |

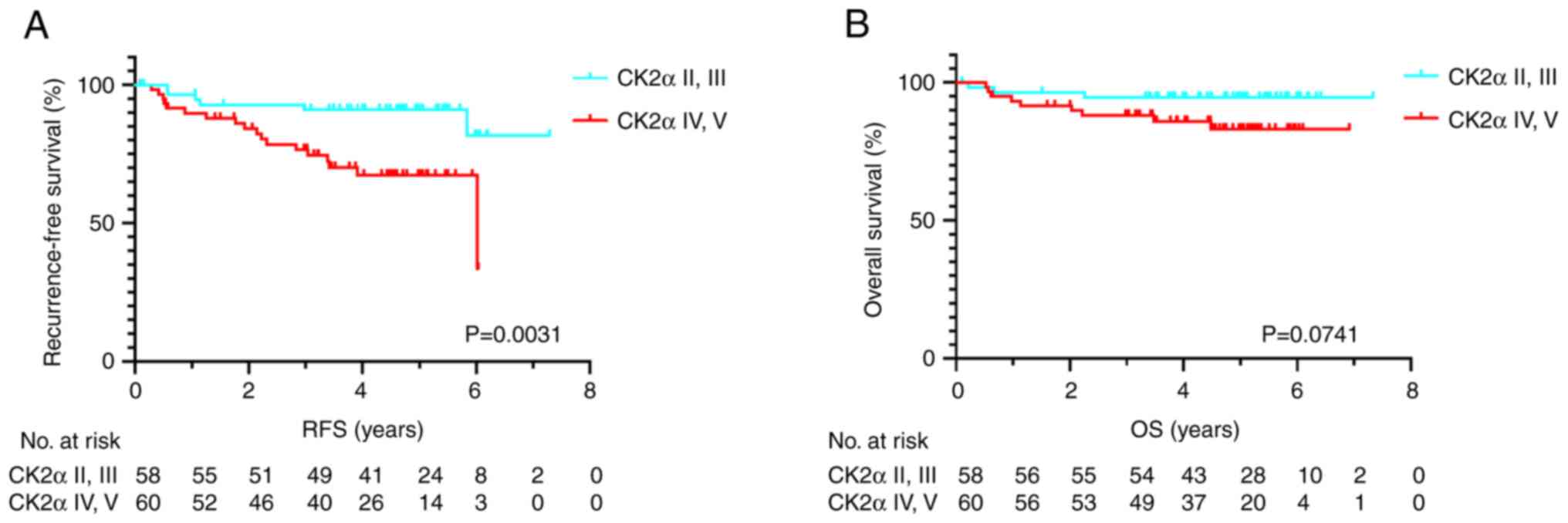

Nucleolar CK2 is associated with poor

prognosis in surgically resected early-stage lung

adenocarcinoma

Nucleolar CK2α staining in relation to RFS and OS

was next investigated. Among the 118 patients, 24 (20.3%)

experienced lung cancer recurrence and 12 (10.2%) patients

succumbed to any cause. The RFS time was significantly shorter in

the positive nucleolar CK2α staining group compared with the

negative group according to the log-rank test (P=0.0031; Fig. 2A). The OS time tended to be shorter

in the positive nucleolar CK2α staining group than the negative

group but without statistical significance (P=0.0741; Fig. 2B). The median RFS and OS were not

reached in all groups.

The sites of first recurrence in the 24 recurrent

cases were the lung (n=11), bone (n=8), mediastinal lymph nodes

(n=4), and hilar lymph node, pleural dissemination, brain, and

kidney (n=1 each). The sites of first recurrence in the

CK2α-positive cases were the lung (n=9), bone (n=5), mediastinal

lymph nodes (n=4), and hilar lymph node, pleural dissemination, and

brain (n=1 each).

Multivariate analysis revealed that lymph node

metastasis and positive nucleolar CK2α staining were poor

prognostic factors for RFS (Table

III). Lymphatic invasion was the only poor prognostic factor

for OS (Table IV).

| Table III.Univariate and Cox regression

multivariable stepwise procedure of recurrence-free survival in all

patients (N=118). |

Table III.

Univariate and Cox regression

multivariable stepwise procedure of recurrence-free survival in all

patients (N=118).

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | No. | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age (≥70

years) | 59 | 1.004 | 0.469–2.324 | 0.916 |

|

|

|

| Sex (male) | 64 | 1.732 | 0.737–4.072 | 0.208 |

|

|

|

| Lymph node

metastasis (positive) | 14 | 13.382 | 5.724–31.284 | <0.001 | 11.448 | 4.890–26.803 | <0.001 |

| p-stage

(II–III) | 20 | 10.745 | 4.565–25.292 | <0.001 |

|

|

|

| Lymphatic invasion

(positive) | 18 | 7.470 | 3.287–16.977 | <0.001 |

|

|

|

| Microscopic

vascular invasion (positive) | 25 | 4.148 | 1.829–9.411 | 0.001 |

|

|

|

| Histological type

(invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma) | 5 | 1.718 | 0.231–12.789 | 0.597 |

|

|

|

| Epidermal growth

factor receptor gene mutation (Neg and NE) | 76 | 0.617 | 0.276–1.382 | 0.241 |

|

|

|

| Anaplastic lymphoma

kinase gene translocation (Neg and NE) | 116 | 20.746 |

<0.001–1000< | 0.649 |

|

|

|

| Nucleolar casein

kinase 2 alpha (positive) | 60 | 3.745 | 1.470–9.541 | 0.006 | 3.038 | 1.178–7.836 | 0.022 |

| Table IV.Univariate and Cox regression

multivariable stepwise procedure of overall survival in all

patients (N=118). |

Table IV.

Univariate and Cox regression

multivariable stepwise procedure of overall survival in all

patients (N=118).

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | No. | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age (≥70) | 59 | 2.105 | 0.634–6.991 | 0.224 |

|

|

|

| Sex (male) | 64 | 4.455 | 0.976–20.340 | 0.054 |

|

|

|

| Lymph node

metastasis (positive) | 14 | 5.787 | 1.835–18.250 | 0.003 |

|

|

|

| p-stage

(II–III) | 20 | 5.217 | 1.681–16.188 | 0.004 |

|

|

|

| Lymphatic invasion

(positive) | 18 | 6.240 | 2.009–19.378 | 0.002 | 6.240 | 2.009–19.378 | 0.002 |

| Microscopic

vascular invasion (positive) | 25 | 2.874 | 0.910–9.071 | 0.072 |

|

|

|

| Histological type

(invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma) | 5 | 2.706 | 0.348–21.021 | 0.341 |

|

|

|

| Epidermal growth

factor receptor gene mutation (Neg and NE) | 76 | 2.747 | 0.601–12.555 | 0.192 |

|

|

|

| Anaplastic lymphoma

kinase gene translocation (Neg and NE) | 116 | 20.653 |

<0.001–1000< | 0.754 |

|

|

|

| Nucleolar casein

kinase 2 alpha (positive) | 60 | 3.097 | 0.838–11.449 | 0.090 |

|

|

|

Patients with adenocarcinoma in situ and MIA

have a favorable prognosis, and patients with IMA have a worse

prognosis relative to patients with INMA (2,3). Thus,

focus was next addressed on invasive non-mucinous patients.

Multivariate analysis of RFS showed that among patients with INMA,

lymph node metastasis and nucleolar CK2α staining positivity were

independent poor prognostic factors (Table SII). Age ≥70 years, lymph node

metastasis and lymphatic invasion were poor prognostic factors for

OS (Table SIII).

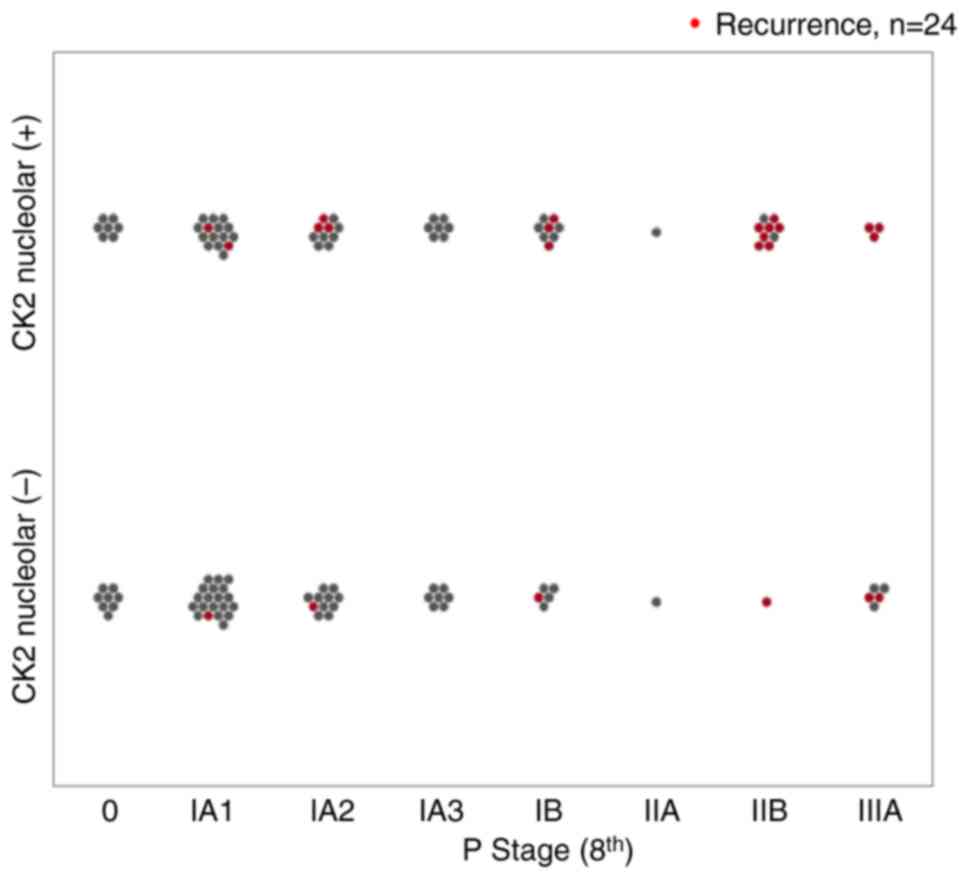

The relationship between nucleolar CK2α staining and

recurrence by stage in all cases is demonstrated in Fig. 3. Recurrence was more frequent in

patients with positive nucleolar CK2α staining, regardless of

pathological stage. The percentages of recurrent cases positive and

negative for nucleolar CK2α staining were 20% (8/40) and 7% (3/43)

in stage I, and 77% (10/13) and 43% (3/7) in stage II–III,

respectively.

Recurrence in stage I was more frequent among

nucleolar CK2α-positive cases. Positive nucleolar CK2α staining

tended to be a poor prognostic factor for RFS even in patients in

stage IA1 to IA2 (Fig. S2).

Discussion

Cancer is characterized by the accumulation of

heterogeneous genetic mutations as it proliferates, and treatment

is generally more difficult after recurrence as the tumors continue

to grow as a non-monoclonal cancer cell population. Therefore, it

is critical to identify patients at risk of recurrence as early as

possible to administer treatment to prevent future recurrence.

The present findings identified that CK2α in the

nucleolus of cancer cells in patients with early-stage lung

adenocarcinoma was associated with poor prognosis. Patients with

positive CK2α staining in nucleoli had significantly worse RFS

after surgical resection compared with patients with negative

staining (P=0.0031). The positive staining of CK2α in nucleoli was

independent of pathological stage, histological type and

histological grade (Table II).

Multivariate analysis revealed that positive CK2α staining in

nucleoli was an independent poor prognostic factor of RFS (Table III). This finding indicates that

positive CK2α staining in cancer cell nucleoli is a novel poor

prognostic factor in patients with early-stage lung adenocarcinoma.

Moreover, CK2α positive staining in the nucleolus may be a useful

marker for predicting future recurrence even in patients with stage

I lung adenocarcinoma, as shown in Fig.

3. Nucleolus-positive staining associated with recurrence.

Positive CK2α staining in the nucleolus may be a potential marker

that can be identified in 2D histopathological images in cases in

which there are extremely small lymphatic or venous invasions that

are difficult to determine on pathological sections.

In INMA of the lung (3,14),

nucleolus CK2α staining may improve the prediction of recurrence

combined with histological grade. In a previous study of invasive

breast carcinoma, positive CK2α staining in the nucleolus was

independent of luminal type, human epidermal growth factor receptor

2, or the triple negative type and a poor prognostic factor

(25). The absence of significant

differences in the OS of patients with and without CK2α nucleolar

staining in the present study may be because of the small number of

events. A longer observation period may also be necessary to

compare OS in patients with surgically resected early-stage NSCLC

because of the influence of treatment after recurrence.

The present findings suggest the potential value of

CK2α nucleolar staining to predict prognosis in surgically resected

early-stage NSCLC. Currently, there are no clear prognostic markers

in NSCLC other than TNM. While the International Association for

the Study of Lung Cancer Pathology Committee proposed histological

grade as a prognostic factor in surgically resected early-stage

INMA (14), the results of the

present study showed that CK2α staining in nucleoli is a prognostic

factor independent of this histological grade. In recent years,

limited resection approaches such as segmentectomy or partial

resection for very early-stage NSCLC have become a standard

treatment (9–11). CK2α staining of the nucleoli may be

worth considering as a biomarker in such patients with very

early-stage NSCLC to determine whether limited resection or

lobectomy should be performed. Rapid immunostaining can be useful

to make this decision intraoperatively (42). In breast cancer, the biological type

determined from genetic analysis is used to predict prognosis and

determine the indication for adjuvant therapy (43–45).

In the present study, adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to

eligible patients, making it difficult to consider the indication

for this on the basis of CK2α nucleolar staining. Nevertheless,

CK2α nucleolar staining could be used to identify those patients

likely to benefit from treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy,

including patients with early-stage non-small lung cancer.

Previous studies reported that CK2 is associated

with lung cancer metastasis (46),

and that chemical inhibitors of CK2 improve drug resistance

(47–49). The relationship between CK2 and

tumor immunity is also gaining attention (50,51). A

previous study reported that CK2 activated NF-E2-related factor 2

(Nrf2) by degrading Kelch-like ECH associated protein 1 (Keap1) and

activating AMP-activated protein kinase in human cancer cells

(52). Mutations in the Keap1-Nrf2

pathway are common in NSCLC and have been associated with poor

prognosis (53). Some clinical

trials of CX-4945, a low-molecular weight inhibitor of CK2α, for

various cancers are now underway. The current study included

patients with NSCLC who underwent surgical resection, and future

studies should be conducted in patients who have received drug

therapy. Studies examining the efficacy of CK2 inhibitors in

adjuvant therapy for surgically resected early-stage NSCLC patients

are also required.

A couple of limitations of the present study are

that it was a single-center, retrospective study, and future

validation at multiple centers is needed. Additionally, future

studies should investigate whether CK2α staining in nucleoli is

related to the efficacy of drug therapy in NCSLC, including

adjuvant therapy; these findings would indicate whether CK2α

staining in nucleoli could be developed into a useful biomarker for

treatment selection in addition to its utility as a prognostic

factor. In normal cells, CK2 is mostly localized in the cytoplasm.

The current results showed CK2 accumulation in the nucleolus in

human cancer tissues. Whether this accumulation of CK2 in the

nucleolus is predictive biomarker of a future recurrence should be

confirmed in future studies. The CK2 complex in MCF-7 breast cancer

cells is associated with protein synthesis (25), and it was previously reported that

CK2 interacts with chromatin in the cell nucleus to enhance gene

expression and is involved in rRNA synthesis (24). The molecular mechanisms underlying

the association of nucleolar CK2α with recurrence in lung

adenocarcinoma are yet to be determined.

In summary, the current findings indicated that CK2α

staining in nucleoli may be a useful marker for poor prognosis in

patients with surgically resected early-stage lung adenocarcinoma.

Positive staining of CK2α in nucleoli was independent of

pathological stage, histological type and histological grade.

Combining CK2α with TNM and histological grade may more accurately

predict recurrence in surgically resected early-stage lung

adenocarcinoma. Rapid evaluation by immunostaining of CK2α in

nucleoli could also be used to identify patients with early-stage

lung adenocarcinoma in whom limited surgery may be appropriate. In

patients with surgically resected nucleolar CK2α-positive lung

adenocarcinoma, CK2 inhibitors may reduce the risk of recurrence

when administered as adjuvant therapy after surgery. With the

global clinical development of CK2α inhibitors now underway, CK2α

is also a promising therapeutic target in lung adenocarcinoma,

including advanced disease, and should be studied in squamous cell

lung cancer.

In conclusion, surgically resected early-stage lung

adenocarcinoma patients with positive nucleolar CK2α staining had

significantly worse RFS compared with patients with negative

staining. Positive staining of CK2α in the nucleoli was independent

of pathological stage, histological type and histological grade,

and was an independent poor prognostic factor in the multivariate

analysis of RFS. The findings of the present study indicated that

nucleolar CK2α may be a prognostic factor and promising therapeutic

target for lung adenocarcinoma. These results require validation in

a multicenter setting with a larger number of patients.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms Yukiko Kikuta, Ms Moe

Muramatsu and Ms Junko Yamaki for technical support. The authors

would like to thank Dr Gabrielle White Wolf for editing a draft of

this manuscript.

Funding

This present study was supported by Japan Agency for Medical

Research and Development to MKH (AMED; grant nos. 20lm0203006j0004

and 22ym00126808j0001).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SM, MKH, YH and HS conceptualized the study. SM, YK

and MKH conducted investigation. SM, YK and MKH confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. SM, MKH, YO, MW, NO and KH

acquired data. SM, YK and MKH analyzed and validated data. SM and

MKH prepared the original draft of the manuscript. MKH and HS

wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. SM visualized data. YH

and HS supervised the study. SM and MKH performed project

administration. MKH acquired funding. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted according to the

guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved

(approval no. 30113; August 30, 2022) by the institutional Ethics

Committee of Fukushima Medical University (Fukushima, Japan).

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in

the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ALK

|

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

|

|

CK2α

|

casein kinase 2 alpha

|

|

EGFR

|

epidermal growth factor receptor

|

|

Keap1

|

Kelch-like ECH associated protein

1

|

|

Nrf2

|

NF-E2-related factor 2

|

|

PD-1

|

programmed death-1

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed death-ligand 1

|

|

TPS

|

tumor proportion score

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

UICC International Union Against Cancer, .

TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 8th ed. Wiley Blackwell;

2016

|

|

3

|

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial

Board, . Thoracic Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours; 5th

Edition. 2021

|

|

4

|

Attili I, Corvaja C, Spitaleri G, Del

Signore E, Trillo Aliaga P, Passaro A and de Marinis F: New

generations of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in treating NSCLC with

oncogene addiction: Strengths and limitations. Cancers (Basel).

15:50792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, Csőszi T,

Vynnychenko I, Goloborodko O, Luft A, Akopov A, Martinez-Marti A,

Kenmotsu H, et al: Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant

chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer

(IMpower010): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 398:1344–1357. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M,

Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, Felip E, Broderick SR, Brahmer JR, Swanson

SJ, et al: Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable

Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 386:1973–1985. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, Taube

JM, Galffy G, Hochmair M, Winder T, Zukov R, Garbaos G, Gao S, et

al: Perioperative durvalumab for resectable Non-Small-cell lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 389:1672–1684. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lu S, Wu L, Zhang W, Zhang P, Wang W, Fang

W, Xing W, Chen Q, Mei J, Yang L, et al: Perioperative toripalimab

+ platinum-doublet chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy in resectable

stage II/III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Interim event-free

survival (EFS) analysis of the phase III Neotorch study. J Clin

Oncol. 41:4251262023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Altorki N, Wang X, Kozono D, Watt C,

Landrenau R, Wigle D, Port J, Jones DR, Conti M, Ashrafi AS, et al:

Lobar or Sublobar Resection for Peripheral Stage IA Non-Small-Cell

Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 388:489–498. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Saji H, Okada M, Tsuboi M, Nakajima R,

Suzuki K, Aokage K, Aoki T, Okami J, Yoshino I, Ito H, et al:

Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral

non-small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): A multicentre,

open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial.

Lancet. 399:1607–1617. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Aokage K, Suzuki K, Saji H, Wakabayashi M,

Kataoka T, Sekino Y, Fukuda H, Endo M, Hattori A, Mimae T, et al:

Segmentectomy for ground-glass-dominant lung cancer with a tumour

diameter of 3 cm or less including ground-glass opacity (JCOG1211):

A multicentre, single-arm, confirmatory, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Respir Med. 11:540–549. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Offin M, Chan JM, Tenet M, Rizvi HA, Shen

R, Riely GJ, Rekhtman N, Daneshbod Y, Quintanal-Villalonga A,

Penson A, et al: Concurrent RB1 and TP53 alterations define a

subset of EGFR-Mutant lung cancers at risk for histologic

transformation and inferior clinical outcomes. J Thorac Oncol.

14:1784–1793. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Farooq H, Bien H, Chang V, Becker D, Park

YH and Bates SE: Loss of function STK11 alterations and poor

outcomes in non-small-cell lung cancer: Literature and case series

of US Veterans. Semin Oncol. 49:319–325. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Moreira AL, Ocampo PSS, Xia Y, Zhong H,

Russell PA, Minami Y, Cooper WA, Yoshida A, Bubendorf L, Papotti M,

et al: A grading system for invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma: A

proposal from the international association for the study of lung

cancer pathology committee. J Thorac Oncol. 15:1599–1610. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Varga Z, Sinn P and Seidman AD: Summary of

head-to-head comparisons of patient risk classifications by the

21-gene Recurrence Score® (RS) assay and other genomic

assays for early breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 145:882–893. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Seldin DC and Leder P: Casein Kinase II α

Transgene-Induced murine lymphoma: Relation to theileriosis in

cattle. Science. 267:894–897. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fleuren EDG, Zhang L, Wu J and Daly RJ:

The kinome ‘at large’ in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 16:83–98. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chua MMJ, Lee M and Dominguez I:

Cancer-type dependent expression of CK2 transcripts. PLoS One.

12:e01888542017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Strum SW, Gyenis L and Litchfield DW:

CSNK2 in cancer: Pathophysiology and translational applications. Br

J Cancer. 126:994–1003. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gapany M, Faust RA, Tawfic S, Davis A,

Adams GL, Leder P and Ahmed K: Association of elevated protein

kinase CK2 activity with aggressive behavior of squamous cell

carcinoma of the head and neck. Mol Med. 1:659–666. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Landesman-Bollag E, Romieu-Mourez R, Song

DH, Sonenshein GE, Cardiff RD and Seldin DC: Protein kinase CK2 in

mammary gland tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 20:3247–3257. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Firnau MB and Brieger A: CK2 and the

hallmarks of cancer. Biomedicines. 10:19872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Homma MK, Shibata T, Suzuki T, Ogura M,

Kozuka-Hata H, Oyama M and Homma Y: Role for protein kinase CK2 on

cell proliferation: Assessing CK2 complex components in the nucleus

during the cell cycle progression. In Protein Kinase CK2 Cellular

Function in Normal and Disease States. Ahmed K, Issinger OG and

Szyszka R: Springer International Publishing; Cham: pp. 197–226.

2015, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Homma MK, Nakato R, Niida A, Bando M,

Fujiki K, Yokota N, Yamamoto S, Shibata T, Takagi M, Yamaki J, et

al: Cell cycle-dependent gene networks for cell proliferation

activated by nuclear CK2α complexes. Life Sci Alliance.

7:e2023020772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Homma MK, Kiko Y, Hashimoto Y, Nagatsuka

M, Katagata N, Masui S, Homma Y and Nomizu T: Intracellular

localization of CK2α as a prognostic factor in invasive breast

carcinomas. Cancer Sci. 112:619–628. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Korsensky L, Chorev D, Saleem H,

Heller-Japheth R, Rabinovitz S, Haif S, Dahan N, Ziv T and Ron D:

Regulation of stability and inhibitory activity of the tumor

suppressor SEF through casein-kinase II-mediated phosphorylation.

Cell Signal. 86:1100852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sit M, Aktas G, Ozer B, Kocak MZ, Erkus E,

Erkol H, Yaman S and Savli H: Mean platelet volume: An overlooked

herald of malignant thyroid nodules. Acta Clin Croat. 58:417–420.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Atak BM, Bakir Kahveci G, Bilgin S,

Kurtkulagi O and Kosekli MA: Platelet to lymphocyte ratio in

differentiation of benign and malignant thyroid nodules. Exp Biomed

Res. 4:148–153. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Hong H and Benveniste EN: The immune

regulatory role of protein kinase CK2 and its implications for

treatment of cancer. Biomedicines. 9:19322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Di Maira G, Salvi M, Arrigoni G, Marin O,

Sarno S, Brustolon F, Pinna LA and Ruzzene M: Protein kinase CK2

phosphorylates and upregulates Akt/PKB. Cell Death Differ.

12:668–677. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Di Maira G, Brustolon F, Pinna LA and

Ruzzene M: Dephosphorylation and inactivation of Akt/PKB is

counteracted by protein kinase CK2 in HEK 293T cells. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 66:3363–3373. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang D, Westerheide SD, Hanson JL and

Baldwin AS Jr: Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced phosphorylation

of RelA/p65 on Ser529 is controlled by casein kinase II. J Biol

Chem. 275:32592–32597. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liongue C, O'Sullivan LA, Trengove MC and

Ward AC: Evolution of JAK-STAT pathway components: Mechanisms and

role in immune system development. PLoS One. 7:e327772012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Manni S, Brancalion A, Mandato E, Tubi LQ,

Colpo A, Pizzi M, Cappellesso R, Zaffino F, Di Maggio SA, et al:

Protein kinase CK2 inhibition down modulates the NF-κB and STAT3

survival pathways, enhances the cellular proteotoxic stress and

synergistically boosts the cytotoxic effect of bortezomib on

multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma cells. PLoS One.

8:e752802013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zheng Y, Qin H, Frank SJ, Deng L,

Litchfield DW, Tefferi A, Pardanani A, Lin FT, Li J, Sha B and

Benveniste EN: A CK2-dependent mechanism for activation of the

JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Blood. 118:156–166. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hashimoto A, Gao C, Mastio J, Kossenkov A,

Abrams SI, Purandare AV, Desilva H, Wee S, Hunt J, Jure-Kunkel M

and Gabrilovich DI: Inhibition of casein kinase 2 disrupts

differentiation of myeloid cells in cancer and enhances the

efficacy of immunotherapy in Mice. Cancer Res. 78:5644–5655. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu R, Tang W, Qiu K, Li P, Li Y, Li D and

He Z: An Integrative Pan-cancer analysis of the prognostic and

immunological role of casein kinase 2 alpha Protein 1 (CSNK2A1) in

human cancers: A study based on bioinformatics and

immunohistochemical analysis. Int J Gen Med. 14:6215–6232. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

American Joint Committee on Cancer, . AJCC

Cancer Staging Manual. 8th edition. Springer; 2017

|

|

39

|

Seto T, Kiura K, Nishio M, Nakagawa K,

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Hida T, Yamamoto N, Yoshioka H, Harada M, et

al: CH5424802 (RO5424802) for patients with ALK-rearranged advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer (AF-001JP study): A single-arm,

open-label, phase 1–2 study. Lancet Oncol. 14:590–598. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Roach C, Zhang N, Corigliano E, Jansson M,

Toland G, Ponto G, Dolled-Filhart M, Emancipator K, Stanforth D and

Kulangara K: Development of a companion diagnostic PD-L1

immunohistochemistry assay for pembrolizumab therapy in

non-small-cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol.

24:392–397. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Jänne PA, Yang JCH, Kim DW, Planchard D,

Ohe Y, Ramalingam SS, Ahn MJ, Kim SW, Su WC, Horn L, et al: AZD9291

in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J

Med. 372:1689–1699. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Terata K, Saito H, Nanjo H, Hiroshima Y,

Ito S, Narita K, Akagami Y, Nakamura R, Konno H, Ito A, et al:

Novel rapid-immunohistochemistry using an alternating current

electric field for intraoperative diagnosis of sentinel lymph nodes

in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 7:28102017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sotiriou C and Pusztai L: Gene-expression

signatures in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 360:790–800. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Harris LN, Ismaila N, McShane LM, Andre F,

Collyar DE, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hammond EH, Kuderer NM, Liu MC,

Mennel RG, et al: Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant

systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer:

American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline.

J Clin Oncol. 34:1134–1150. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Giuliano AE, Connolly JL, Edge SB,

Mittendorf EA, Rugo HS, Solin LJ, Weaver DL, Winchester DJ and

Hortobagyi GN: Breast Cancer-Major changes in the American Joint

Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer

J Clin. 67:290–303. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu Y, Amin EB, Mayo MW, Chudgar NP,

Bucciarelli PR, Kadota K, Adusumilli PS and Jones DR: CK2α, drives

lung cancer metastasis by targeting brms1 nuclear export and

degradation. Cancer Res. 76:2675–2686. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yang B, Yao J, Li B, Shao G and Cui Y:

Inhibition of protein kinase CK2 sensitizes non-small cell lung

cancer cells to cisplatin via upregulation of PML. Mol Cell

Biochem. 436:87–97. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

So KS, Rho JK, Choi YJ, Kim SY, Choi CM,

Chun YJ and Lee JC: AKT/mTOR down-regulation by CX-4945, a CK2

inhibitor, promotes apoptosis in chemorefractory non-small cell

lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 35:1537–1542. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jin C, Song P and Pang J: The CK2

inhibitor CX4945 reverses cisplatin resistance in the A549/DDP

human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Oncol Lett. 18:3845–3856.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhao X, Wei Y, Chu YY, Li Y, Hsu JM, Jiang

Z, Liu C, Hsu JL, Chang WC, Yang R, et al: Phosphorylation and

stabilization of PD-L1 by CK2 suppresses dendritic cell function.

Cancer Res. 82:2185–2195. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Husain K, Williamson TT, Nelson N and

Ghansah T: Protein kinase 2 (CK2): A potential regulator of immune

cell development and function in cancer. Immunol Med. 44:159–174.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jang DE, Song J, Park JW, Yoon SH and Bae

YS: Protein kinase CK2 activates Nrf2 via autophagic degradation of

Keap1 and activation of AMPK in human cancer cells. BMB Rep.

53:72–277. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hellyer JA, Padda SK, Diehn M and Wakelee

HA: Clinical Implications of KEAP1-NFE2L2 Mutations in NSCLC. J

Thorac Oncol. 16:395–403. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|