Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the second most lethal gynecologic

malignancy, with an estimated 206,839 mortalities associated with

the disease in 2022 according to the recent global cancer

statistics (1). The data from the

American Cancer Society in 2024 indicated that there has been no

improvement in the mortality/incidence rate of 62% of ovarian

cancers in the last 30 years (2).

More than 80% of patients with ovarian cancer experience recurrence

and eventually develop treatment resistance after surgery and

platinum-based chemotherapy (3,4). The

mainstay of treatment for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC),

which progresses within 6 months of completing the platinum

treatment, has been the sequential use of cytotoxic drugs,

including pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), gemcitabine,

paclitaxel and topotecan, in recent years (4). However, the effective proportion of

these drugs is only 10–15%, and the expected survival time is ~12

months (5,6). The ongoing research on developing new

drugs and identifying new therapeutic targets is constantly

evolving.

ADCs selectively deliver cytotoxic payloads to tumor

cells, representing a rapidly evolving cancer therapy (6–8). At

present, 15 ADCs have been approved by the US Food and Drug

Administration for tumor treatment, and the development of these

drugs for PROC has gained interest. In November 2022, mirvetuximab

soravtansine (MIRV; ELAHERE®) was approved by the US

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the first ADC for ovarian

cancer (9). MIRV targets folate

receptor α (FRα) on the surface of tumor cells to induce tumor cell

killing, thereby displaying promising clinical activity in patients

with FRα-positive ovarian cancer (10). Other ADCs are still under active

development in the treatment of PROC. In addition, studies on using

ADCs in combination therapy with various anticancer drugs are

underway (NCT05887609, NCT06660511, NCT05941507).

The present review aimed to describe the structure

and mechanism of action of ADCs, present an overview of the

progress in the effectiveness of various types of ADCs in treating

PROC in preclinical studies and clinical trials, and to discuss the

recent advances in combining ADCs with chemotherapeutic agents,

targeted agents and immunotherapies for PROC treatment. The present

study also analyzed the toxicity characteristics and management of

ADCs and finally considered the future development of ADCs for

ovarian cancer.

Literature search

A literature search was performed using the Web of

Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos/) and PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

databases. ‘ADC’, ‘monotherapy’, ‘combination therapy’,

‘platinum-resistant ovarian cancer’ and ‘research progress’ were

used as the core search terms. Each core search term was searched

separately, and then Boolean logical operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were

applied for combined searches, for example, ‘(ADC AND monotherapy

AND platinum-resistant ovarian cancer) OR (ADC AND combination

therapy AND platinum-resistant ovarian cancer)’. The search fields

were limited to the title, abstract and keywords to pinpoint

relevant literature. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Studies focused on ADC monotherapy or combination therapy for PROC;

ii) clinical research, basic research or review articles; iii)

language limited to English; and iv) published within the last 10

years (January 1, 2014 to December 1, 2024) to obtain the latest

research developments. The literature needed for the writing

process was also included where appropriate. The exclusion criteria

were as follows: i) Duplicate publications or highly similar

content; ii) non-research literature such as conference abstracts,

reviews, letters, news reports and so forth; and iv) literature

with weak relevance or missing key data.

The quality of clinical studies was assessed by

evaluating randomization methods, implementation of blinding, and

descriptions of loss of visits and withdrawals; the assessment for

the quality of basic research covered dimensions such as

rationality of experimental design, sample size and statistical

methods of data; and that of review articles focused on the

comprehensiveness of their literature coverage, depth of analysis

and logic. Two professionals performed independent assessment, and

a third expert was asked to adjudicate in case of disagreement.

Structure and mechanism of action of

ADCs

Structure and mechanism of action

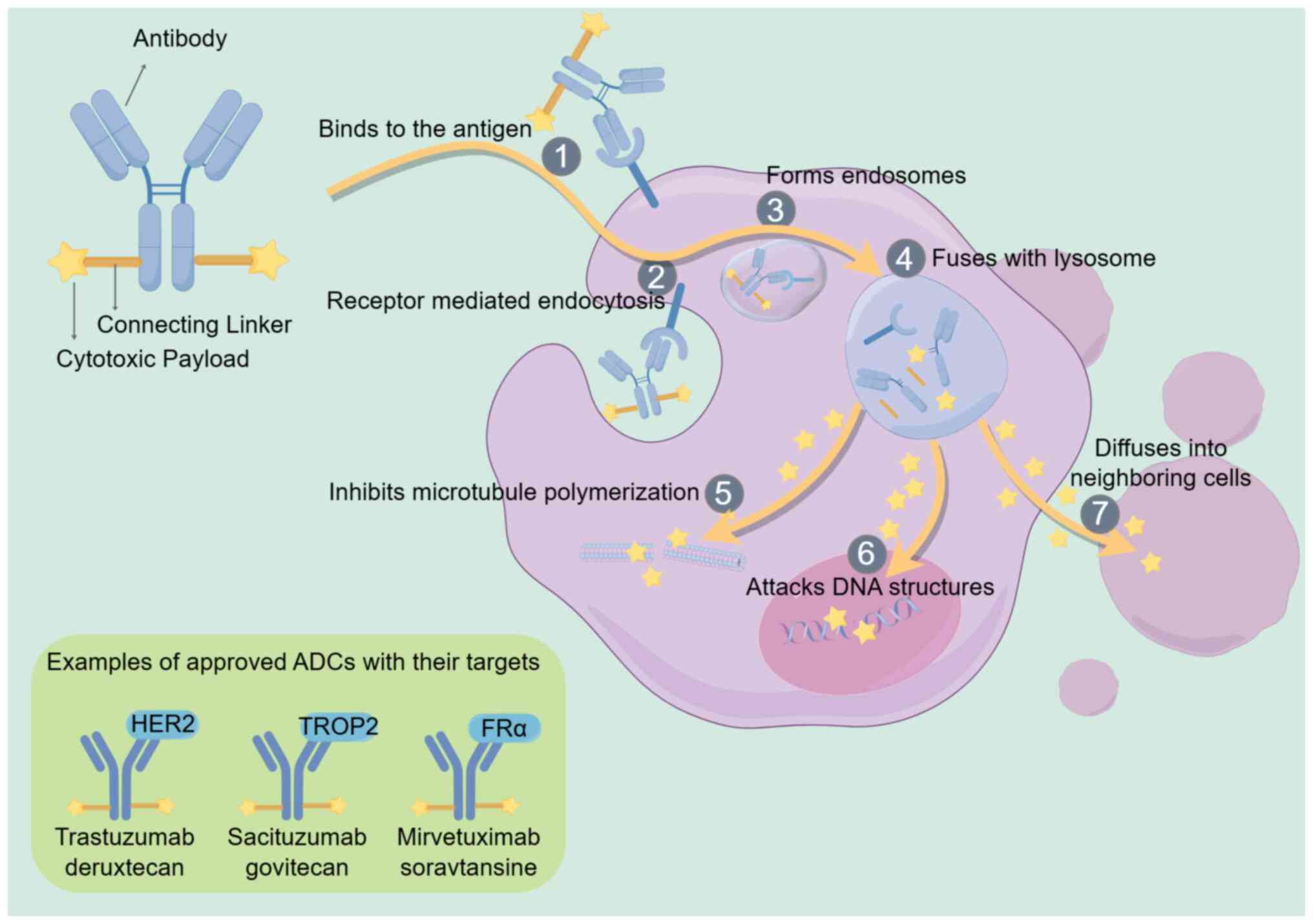

ADCs are complexes comprising an antibody, a

cytotoxic payload and a connecting linker. They specifically

recognize tumor cell surface antigens, induce endocytosis and

release cytotoxic drugs into tumor cells, ultimately leading to the

death of tumor cells (6,11). The connection of cytotoxic drugs

with antibodies was first realized in the 1950s (12). Researchers conducted clinical trials

on the mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)-based ADCs in the 1980s

(13). Following a long and slow

development, the field has become active again in the last decade,

with ADCs entering the global market at a much faster pace.

Usually, ADCs are administered intravenously. Then, the antibodies

of ADCs bind to the antigen on cancer cells, penetrate the cells

via receptor-mediated endocytosis to form endosomes and fuse with

lysosomes. The cytotoxic payload detaches from the antibody and

diffuses into the cell in the presence of various lysosome enzymes,

resulting in tumor cell death by disrupting DNA structures or

inhibiting microtubule polymerization (8,14,15).

In addition, the payload can penetrate the extracellular matrix and

surrounding cells, resulting in a bystander effect (16). Fig.

1 shows a schematic representation of the structure and

mechanism of action of conventional ADCs.

The most commonly used antibody backbone in ADCs is

IgG. The antibody-binding antigen should be highly expressed on the

surface of tumor cell membranes with minimal expression on normal

tissues (17,18) to enhance the effectiveness of the

drug by delivering it to specific targets, protect the non-target

tissues from the damage caused by chemotherapy, and reduce the

systemic toxicity. FRα, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2), trophoblast cell surface antigen-2 (TROP2), mesothelin,

sodium-dependent phosphate transporter 2b (NaPi2b) and CDH6 are

usually overexpressed in epithelial ovarian cancer, making them the

most commonly used conjugated antigens (19).

The covalent binding of antigen-targeting antibodies

to cytotoxic payloads requires connecting linkers (20). Linkers have two main functions; the

primary one is maintaining stability in the bloodstream, keeping

the cytotoxic payload attached to the antibody when it moves

through the plasma; the other aspect is to efficiently release the

payload into the tumor (8). The

linkers should keep this attachment stable and unchanged in the

bloodstream, with the drug being released only after

antigen-antibody binding (21).

Linkers are cleavable or non-cleavable depending on their chemical

characteristics. Cleavable linkers are chemically unstable

structures that can deliver drugs extracellularly and induce the

killing of nearby tumor cells (22,23).

The non-cleavable linker releases the drug solely when the antibody

undergoes internalization and degradation within the lysosomes of

the target cells. However, the cytotoxic payloads are released

after the apoptosis of tumor cells, which may also result in the

non-specific killing of surrounding tumor cells (24).

The cytotoxic payloads in ADCs now encompass a range

of DNA-targeting agents, microtubule-binding proteins and some

topoisomerase 1 inhibitors. The agents targeting microtubules are

the most frequently used payloads, targeting the medenosine and

periwinkle alkaloid sites. They interfere with the kinetics of

microtubule protein polymerization and maintain the cell cycle in

the G2/M phase, leading to cell death (25,26).

Not all tumor types are sensitive to a given type of payload and,

therefore, diversifying payloads is critical to expanding the

indications of ADCs.

ADCs in tumor therapy

Alternative strategies based on the use of ADCs are

highly effective in treating cancer. The use of ADCs in clinical

oncology has increased with the advent of novel technologies and

the discovery of new targets (9,27). To

date, 15 ADCs have received marketing approval from the FDA, and

hundreds more are undergoing preclinical and clinical evaluation

(28). Besides hematological

tumors, ADCs have been approved for use in breast, gastric, lung,

uroepithelial, cervical, ovarian and head-and-neck squamous cell

carcinomas. Several previous studies have described the ADC drugs

approved for oncology treatment (29–31).

Solid tumors offer a broad opportunity for ADC

development. The treatment choices for advanced or metastatic

recurrent solid tumors are limited, and current immunotherapies

rarely cure the disease (9).

Therefore, ADCs have immense potential and unique advantages in a

wide range of solid tumors.

Efficacy of ADC in PROC treatment

ADC monotherapy for PROC

Targeting FRα

FRα, one of the four members of the FR family, is a

glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane protein (32) that binds to folic acid and related

compounds and transports them into the cell through

receptor-mediated endocytosis (33,34).

FRα is seldom expressed in normal tissues but is specifically

expressed in epithelial tumors, including ovarian cancer,

endometrial cancer, triple-negative breast cancer and

non-small-cell lung cancer (35,36),

making FRα a promising target for tumor therapy.

In November 2022, MIRV was approved by the FDA as

the first ADC for ovarian cancer (37). Targeting FRα, MIRV comprises an

antibody, a cleavable linker and a small-molecule microtubule

inhibitor DM4 (a maytansine derivative) (38). MIRV is endocytosed by tumor cells

and transferred to lysosomes, where it is degraded to release

lysine-DM4. Lysine-DM4 produces metabolites that can inhibit

tubulin polymerization and microtubule assembly, causing cell cycle

arrest and leading to cell death (39). Further, the disintegration of tumor

cells leads to the release of catabolic metabolites, which may

induce bystander killing (40–42).

Several recent clinical studies have been conducted

on the efficacy and safety of MIRV in ovarian cancer (43–45). A

phase II trial (NCT04296890) including 106 patients with PROC

showed a reduction in tumor size in 71.4% of patients, an objective

response rate (ORR) of 32.4% and a median duration of remission

(DOR) of 6.9 months (43). This

result supports the clinically meaningful efficacy of MIRV in PROC

expressing FRα, regardless of prior therapy or sequencing.

Recently, a phase III trial (NCT04209855) compared MIRV with

chemotherapeutic drugs (paclitaxel, PLD or topotecan) (45). The results showed a median

progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.62 months in the MIRV group

and 3.98 months in the chemotherapy group. The ORR of MIRV (42.3%)

was significantly higher compared with that of chemotherapy

(15.9%). The median overall survival of MIRV (16.46 months) was

also significantly longer compared with that of chemotherapy (12.75

months). Fewer adverse events also demonstrated the safety of MIRV

over chemotherapy. These results support the use of MIRV for

treating platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer, providing a

new alternative for treating PROC (46). Some ongoing clinical trials are

assessing the efficacy and adverse effects of MIRV in PROC

(NCT06365853, NCT06682988 and NCT05622890).

Besides MIRV, luveltamab tazevibulin (STRO-002) is

the second ADC drug targeting FRα. STRO-002 acts as a tumor killer

by releasing the tubulin-targeting cytotoxin 3-aminophenyl

hemiasterlin (SC209) and reducing the potential for drug efflux

(47). STRO-002 is still in phase

I–III trials (NCT03748186, NCT05200364, NCT06238687 and

NCT05870748), both as a monotherapy or in combination with

bevacizumab in a variety of solid tumors, including PROC.

Farletuzumab ecteribulin (MORAb-202) is another ADC

that targets FRα-expressing tumor cells. MORAb-202 initially

inhibited tumor growth in a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model

of triple-negative breast cancer, demonstrating durable efficacy

proportional to FRα expression (48). In clinical trials, MORAb-202 showed

promising antitumor activity and good tolerability in a phase I

study (NCT03386942) of FRα-positive solid tumors, including PROC

(49). Also, two phase I/II trials

of MORAb-202 for treating PROC (NCT05613088 and NCT04300556) are

underway.

Targeting HER2

HER2 is another promising target that can enhance

cell proliferation, differentiation and migration and inhibit

apoptosis (50). HER2 is

upregulated in a range of solid tumors, including breast, gastric

and gynecological tumors (51).

However, HER2-targeted therapies are not yet approved for use in

diseases other than breast, lung, gastric and colorectal cancers

(52). Trastuzumab deruxtecan

(T-DXd) targets HER2 and contains a topoisomerase I inhibitor

payload (53). T-DXd is approved

for treating HER2-expressing breast and gastric cancers and

HER2-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer (50). Preclinical studies demonstrated the

antitumor activity of T-DXd against primary and metastatic ovarian

tumors overexpressing HER2 (54). A

global multicenter phase II study (NCT04482309) was conducted to

evaluate the efficacy and safety of T-DXd in patients with

HER2-expressing solid tumors across seven cohorts, including three

major gynecological tumors. T-DXd treatment exhibited robust

clinical efficacy, conferring sustained clinical benefits for

patients with HER2-expressing solid tumors (55). Among all studied tumor types, the

highest ORR was observed in the three major gynecological tumor

cohorts, with an ORR of 57.5% for endometrial cancer, 50.0% for

cervical cancer and 45.0% for ovarian cancer. Among the ovarian

cancer cohort, 35.0% of the patients had previously received five

or more lines of treatment and the median overall survival time was

13.2 months; by contrast, the median overall survival time for

patients with high HER2 expression (IHC 3+) increased to 20.0

months (55). These findings

indicate that T-DXd is a promising drug for HER2-expressing

recurrent PROC (56).

Targeting TROP2

TROP2 is another tumor target highly expressed in

ovarian cancer. This is a type I cell surface glycoprotein first

discovered in human trophoblasts (57). It is upregulated in a variety of

malignant tumors and plays an important role in tumor development,

invasion and metastasis (58).

Datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd; DS-1062a), an effective

topoisomerase I inhibitor, is an ADC that targets TROP2. Dato-DXd

specifically binds to TROP2, transports it intracellularly to

lysosomes and releases DXd. In preclinical experiments, Dato-DXd

induced DNA damage and apoptosis of tumor cells in vitro and

displayed antitumor activity in vivo in xenograft tumors

with high TROP2 expression (59).

When mixed with TROP2 (IHC 3+) tumor cells, Dato-DXd showed a

significant bystander-killing effect on tumor cells with low TROP2

expression, thus prolonging the survival time of epithelial ovarian

cancer xenograft models and reducing toxicity (60). Most clinical trials are conducted on

breast cancer. A phase II clinical trial (NCT05489211) is currently

evaluating Dato-DXd for treating advanced/metastatic solid tumors,

including ovarian cancer (61). The

efficacy of Dato-DXd in ovarian cancer expressing TROP2 deserves

continued attention.

Targeting mesothelin

Mesothelin represents a promising potential target

for ovarian cancer. High expression of mesothelin is associated

with chemotherapeutic resistance and poor prognosis in epithelial

ovarian cancer (62). Anetumab

ravtansine exhibits a high degree of affinity for mesothelin, using

the microtubule inhibitor DM4 as a payload. It has displayed high

antitumor activity and good tolerability as a monotherapy in the

preclinical models of ovarian cancer (63). A phase I study (NCT02751918)

determined the antitumor activity, safety and pharmacokinetics of

anetumab ravtansine in PROC-expressing mesothelin. The result

showed an ORR of 27.7%, DOR of 7.6 months and PFS of 5.0 months

(64). This result suggests that

targeting mesothelin is an effective and well-tolerated treatment

option in patients with PROC. The development of other combination

therapy regimens for anetumab ravtansine (65) and other ADCs targeting mesothelin

(BMS-986148) (66) has also

provided preliminary evidence of clinical activity and tolerable

adverse reactions and toxicity in ovarian cancer.

Targeting NaPi2b

NaPi2b is another promising target for ADC, which is

expressed in 95% of ovarian cancers (67). Lifastuzumab vedotin (LIFA) targeting

NaPi2b displayed activity and acceptable safety in phase I studies

(68,69). A phase II study compared the

efficacy of LIFA and polyethylene glycol liposome doxorubicin in

patients with PROC. The results showed that LIFA was

well-tolerated, and ORR increased (34 vs. 15%; P=0.03) (70). Moreover, XMT-1536 and TUB-040 are

other ADCs targeting NaPi2b. Currently, the safety and efficacy of

these drugs in PROC are under evaluation in clinical trials

(NCT06517485, NCT03319628, NCT06517433 and NCT06303505).

Other ADCs

New ADCs for ovarian cancer are constantly being

developed. Raludotatug deruxtecan (R-DXd) targets cadherin 6 (CDH6)

and was effective and safe in a preclinical study using PDX tumor

models of serous ovarian cancer expressing CDH6 (71). B7-H4-directed ADC, using a

pyrrolobenzodiazepine-dimer payload, displayed antitumor activity

in a PARP inhibitor and platinum-resistant PDX model of high-grade

serous ovarian cancer (72).

The findings of several newly completed clinical

trials examining the use of ADCs in ovarian cancer (NCT06517485 and

NCT06517433) are yet to be published. Table I lists the clinical trials

investigating ADC monotherapy for ovarian cancer that deserve

continued attention in the future.

| Table I.Ongoing clinical trials of ADCs

monotherapy in ovarian cancer. |

Table I.

Ongoing clinical trials of ADCs

monotherapy in ovarian cancer.

| NCT identifier | ADC | Target | Ovarian cancer | Phase | Completion

time |

|---|

| NCT06303505 | TUB-040 | NaPi2b | Platinum-resistant,

high-grade ovarian cancer | I/II | 2027-01 |

| NCT06457997 | PHN-010 | - | Advanced/metastatic

serous, endometroid, or clear-cell epithelial ovarian cancer | I | 2027-07 |

| NCT06390995 | Mirvetuximab

Soravtansine (TAK-853) | FRα | FRα-positive

advanced ovarian cancer | I/II | 2026-09-30 |

| NCT04152499 | SKB264 | TROP2 | Locally advanced

unresectable/metastatic epithelial ovarian cancer | I/II | 2026-07-16 |

| NCT06234423 | CUSP06 | CDH6 |

Platinum-refractory/resistant ovarian

cancer | I | 2027-08-31 |

| NCT06003231 | Disitamab vedotin

(DV) | HER2 | Previously treated,

locally-advanced, unresectable or metastatic ovarian neoplasms | II | 2028-05-31 |

| NCT06173037 | RC88 | Mesothelin | Platinum-resistant

recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer | II | 2026-12-31 |

| NCT05103683 | TORL-1-23 | CLDN6 | Advanced ovarian

cancer | I | 2025-11-15 |

| NCT06523803 | ZW171 | Mesothelin |

Mesothelin-expressing advanced or

metastatic ovarian cancer | I | 2027-12 |

| NCT05527184 | IMGN151 | FRα | Recurrent, HGS

epithelial ovarian cancer | I | 2025-12-30 |

| NCT06014190 | HS-20089 | B7-H4 | Recurrent or

metastatic ovarian cancer | II | 2027-12-31 |

| NCT05613088 | Farletuzumab

Ecteribulin (MORAb-202) | FRα | Platinum-resistant

HGS ovarian cancer | II | 2026-10-11 |

| NCT06466187 | SGN-MesoC2 | - | Advanced ovarian

neoplasms | I | 2028-11-01 |

| NCT04300556 | MORAb-202 | FRα | Platinum-resistant

HGS epithelial ovarian cancer | I/II | 2024-10-30 |

| NCT06084481 | ABBV-400 | c-Met | Platinum resistant,

high grade epithelial ovarian cancer | I | 2026-07-01 |

| NCT06238479 | LY4101174 | Nectin-4 | Recurrent, advanced

or metastatic ovarian cancer | I | 2027-03-04 |

| NCT06465069 | LY4052031 | Nectin 4 | Advanced or

metastatic ovarian cancer | I | 2027-05 |

| NCT06545617 | BAT8006 | FRα | Platinum-resistant

epithelial ovarian cancer | I/II | 2028-01-31 |

Combination therapy using ADCs and

other agents

Combination therapy using chemotherapeutic

agents

Chemotherapeutic agents such as platinum, which can

damage DNA, target the S phase of the cell cycle and induce the

G2/M phase. Preclinical studies described below have

shown that these chemotherapeutic agents can bind effectively to

ADCs containing microtubule-disrupting payloads. MIRV has been

demonstrated to arrest the cell cycle and enhance DNA damage. The

combination of MIRV with carboplatin, Adriamycin or doxorubicin has

been found to inhibit proliferation synergistically in ovarian

cancer cell lines and PDX models (73). The combination therapy of

carboplatin and STRO-002 further improved the efficacy of STRO-002

(47). The combination of anetumab

ravtansine with carboplatin or PLD demonstrated enhanced efficacy

in vivo and in vitro (in ovarian cancer cell line and

PDX models) compared with monotherapy in ovarian cancer (74). MIRV combined with carboplatin in

early clinical trials achieved an ORR of 71%, with only minor

adverse events (75), making it a

highly active therapy for ovarian cancer.

Combination therapy with the

molecularly targeted drug bevacizumab

A prevalent issue in solid tumors is inadequate

blood flow and hypoxia within the vasculature (76). Using drugs such as anti-vascular

endothelial growth factor antibodies (e.g., bevacizumab) can

modulate angiogenesis and vascular porosity, thereby altering the

tumor vascular system. Bevacizumab, the first targeted drug

indicated for ovarian cancer, has been approved for use in

combination with chemotherapy (77). Administering bevacizumab in

combination with platinum-based chemotherapy after disease

progression still improved PFS (78). ADCs have also shown safety and

efficacy in combination with bevacizumab, particularly in PROC.

Preclinical studies demonstrated that MIRV combined with

bevacizumab resulted in rapid destruction of the tumor

microvascular system and extensive areas of necrosis (73,74).

Moreover, it was highly effective in a PDX model of PROC, causing

significant regression and complete remission (73). Anetumab ravtansine combined with

bevacizumab also demonstrated enhanced antitumor efficacy (74). These results emphasized the superior

biological activity of the combination and further advanced the

combination into clinical trials.

In clinical trials, the combination of MIRV and

bevacizumab demonstrated efficacy and was well-tolerated in

patients with PROC (79). In

another cohort from the same study (NCT02606305), 94 patients with

PROC treated with MIRV and bevacizumab had an ORR of 44%, an median

duration of remission (mDOR) of 9.7 months, and an median

progression-free survival (mPFS) of 8.2 months (80). Furthermore, incorporating MIRV into

dual therapy with platinum and bevacizumab demonstrated enhanced

efficacy and safety profiles in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer

(81). All these results point to

the importance of ADCs combined with bevacizumab. Currently, a

number of ongoing trials are investigating several additional

combinations of different ADCs with bevacizumab (NCT05445778,

NCT05200364 and NCT03587311).

Combination therapy with

immunotherapy

Other than directly inducing cancer cell death using

cytotoxic payloads, ADC also has antitumor immune activity

(8,82,83).

The related mechanisms, including Fc-mediated effector function,

immune cell death, dendritic cell maturation, enhancement of T-cell

infiltration and enhancement of immune memory, among others, have

been the subject of discussion (84–87).

ADCs have been shown to possess considerable immunomodulatory

capacity in animal models (88).

Combination of ADCs with immunotherapy in refractory tumors is a

promising strategy for clinical treatment; its improved antitumor

effects have been initially demonstrated in many preclinical

studies and early clinical trials.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) combined with

ADCs have synergistic effects in triple-negative breast cancer

(89); the rationale behind this

combination is that ADCs activate the immune system, whereas ICIs

remove the brakes, allowing the immune system to regain its ability

to recognize and kill tumor cells (90). Durvalumab combined with T-DXd

(NCT03742102) exhibited an ORR of 100% and was found to be safe in

a small group of patients with low expression of HER2. The interim

results of T-DXd alone and combined with patulizumab (NCT04538742)

showed ORRs of 77.3 and 82.0% and 12-month PFSs of 77.3 and 89.4%,

respectively, demonstrating promising efficacy and controllable

safety. The clinical benefits of ADCs combined with immunotherapy

have been observed in clinical trials on both uroepithelial cancer

(NCT03288545 and NCT04264936) and lung cancer (NCT02099058),

besides breast cancer (91). MIRV

combined with other agents, including pembrolizumab, was evaluated

in FRα-positive PROC. Preliminary data showed good tolerability and

therapeutic activity, with an ORR of 43%, mDOR of 6.9 months, and

mPFS of 5.2 months for MIRV combined with pembrolizumab

(NCT02606305). The synergistic effect of ADCs and immunotherapy can

overcome treatment resistance, displaying encouraging efficacy and

safety in tumor treatment. However, large, randomized phase III

clinical trials are needed to test their efficacy against

conventional therapy.

Table II lists the

ongoing clinical trials on ADC combination therapy for ovarian

cancer.

| Table II.Ongoing clinical trials of ADCs

combination therapy in ovarian cancer. |

Table II.

Ongoing clinical trials of ADCs

combination therapy in ovarian cancer.

| NCT Identifier | ADC combination

therapy | Target | Ovarian cancer | Phase | Completion

time |

|---|

| NCT05887609 | MIRV in combination

with Olaparib | FRα | Recurrent

platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer | II | 2027-12 |

| NCT06660511 | Disitamab vedotin

in combination with anlotinib hydrochloride | HER2 | HER-2-expressing

recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer | I | 2025-10-15 |

| NCT05941507 | LCB84 single agent

and in combination with an anti-PD-1 Ab | TROP2 | Advanced ovarian

cancer | I/II | 2027-05 |

| NCT04606914 | MIRV in combination

with carboplatin | FRα | FRα-positive

advanced-stage ovarian cancer | II | 2028-05-31 |

| NCT05797168 | Saruparib

(AZD5305), bevacizumab, carboplatin | - | Advanced ovarian

cancer | I/II | 2028-01-06 |

| NCT05293496 | Vobramitamab

duocarmazine (MGC018) in combination with lorigerlimab

(MGD019) | B7-H3 | Advanced epithelial

ovarian cancer | I | 2026-03 |

| NCT05445778 | MIRV in combination

with bevacizumab | FRα | FRα-high recurrent

platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian cancer | III | 2029-04 |

| NCT05489211 | Dato-DXd as

monotherapy and in combination with anticancer agents | TROP2 | Advanced/metastatic

ovarian cancer | II | 2026-08-19 |

Toxicity characteristics and management of

ADCs

Adverse reactions and toxicity

ADC has fewer side effects compared with

conventional chemotherapy due to its ability to target tumor cells.

The toxicity of ADCs arises primarily from the payload and

secondarily from linker and bystander effects (92).

A common treatment-related adverse event (TRAE)

associated with MIRV is ocular toxicity. A systematic review and

meta-analysis showed that the most common TRAEs in patients treated

with MIRV were blurred vision (all grades, 45%; grade III, 2%; no

grade IV), nausea (all grades, 42%; grade III, 1%; no grade IV) and

diarrhea (all grades, 42%; grade III, 2%; no grade IV) (93). In a previously mentioned phase II

trial of MIRV (NCT04296890), the most common TRAEs were blurred

vision (all grades, 41%; grade III, 6%; no grade IV), keratoconus

(all grades, 29%; grade III, 8%; grade IV, 1%) and nausea (all

grades, 29%; no grade III or grade IV) (43). Further, ocular events requiring dose

reductions occurred in 12 patients (11%). One patient required

discontinuation of therapy.

T-DXd is associated with interstitial lung disease

(ILD)/pneumonia due to the expression of HER2 in lung epithelial

cells (94). It is mainly localized

to alveolar macrophages; the incidence and severity of

ILD/pneumonia depend on the T-DXd dose and frequency of

administration, suggesting that this ILD/pneumonia may be caused by

cytotoxic lung injury (95). It is

mild in most cases and can be effectively treated, but may be fatal

in some cases (96). Respiratory

disease (pneumonia) has been the most common cause of

treatment-related mortalities in all types of ADC therapy (97). Other TRAEs include nausea and

diarrhea, which are effectively controlled using antiemetic and

antidiarrheal medications.

Management and prevention

Toxicity management includes implementing supportive

measures, suspension of treatment, dosage adjustments, or permanent

discontinuation of therapy. Most ocular adverse events are mild and

reversible; they improve or subside upon discontinuation or therapy

improvement (98). Scheduling

regular eye examinations to monitor early signs and symptoms,

detecting ocular adverse effects in an early stage and prompting

pharmacological intervention, promoting the prophylactic use of

corticosteroids and lubricating eye drops, adjusting ADC dosage

when needed, and maintaining clear communication with the

ophthalmologist can help relieve symptoms before the vision is

affected, ultimately helping the patient to continue treatment

(98,99).

New guidelines for T-DXd-associated ILD/pneumonia

toxicity have been published. A multidisciplinary team and timely

management with steroids are recommended (100). Careful monitoring by a

multidisciplinary team facilitates early detection [e.g., grade I

(100)] of ILD/pneumonia, leading

to timely discontinuation of medication and initiation of steroids,

which prevents the development of fatal ILD/pneumonia.

Challenges in ADC development

The development of ADCs has some challenges. The

target expression is not uniform in tumors due to the heterogeneity

of tumor cells, and ADCs have limited effects on tumor cells with

low or no target expression. Normal tissues expressing the target

are attacked by the drug, limiting the drug dose. When combining

drugs, the optimal dose of each drug and the order of

administration also need to be re-explored. Other challenges

include tumor cells developing resistance to ADCs through multiple

mechanisms, the need to identify potential biomarkers for patient

selection and limitations in current clinical trial designs.

Mechanisms of ADC resistance

ADC resistance can be caused by various mechanisms,

including change in antigen expression, failure of ADC

transportation, failure of ADC internalization, change in tumor

sensitivity, exocytosis of ADC payload and activation of signaling

pathways (101–103). Some of these mechanisms are not

fully understood.

First, alterations occur in target antigen

expression, including target downregulation, loss or mutations in

target genes. Some tumor cells may evade ADC recognition and

binding by reducing or completely losing target expression.

Mutations in the target gene may also alter the structure and

function of the target, thus affecting the binding affinity of the

ADC to the target (101,102).

Second, the abnormal expression or defective

function of endocytosis-related proteins, such as cell surface grid

proteins, in some tumor cells can lead to the inability of ADC to

enter the cell effectively during the internalization and

processing of ADC. ADCs that enter the cell are usually transported

to the lysosome for degradation, releasing cytotoxic drugs to play

a role. If tumor cells enhance the stability of lysosomes or change

the microenvironment of lysosomes, ADCs cannot release drugs in

lysosomes, resulting in drug resistance (103,104).

Furthermore, a resistance mechanism related to drug

metabolism and clearance involves high expression of drug efflux

pumps (e.g., drug transporter proteins such as multidrug resistance

protein 1 and multidrug resistance-associated protein 1), which can

pump ADCs or their released cytotoxic drugs out of the cell,

decreasing the drug concentration in the cell, thus leading to drug

resistance (104). In breast

cancer, acquired resistance to ADC developed in two different

cancer cells after months of drug treatment, primarily due to

increased expression of the drug efflux protein ABCC1 or decreased

expression of HER2 antigen (105).

Finally, the alterations in multiple signaling

pathways in tumor cells are also closely related to ADC resistance.

For example, the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

can promote the proliferation, survival and metabolism of tumor

cells, making them resistant to the cytotoxic effects of ADCs. The

abnormal activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway may also lead

to the development of ADC resistance in tumor cells (106). Alterations in some signaling

pathways involved in regulating the cell cycle and apoptosis (such

as aberrant activation of STAT3) can also lead to the development

of ADC resistance (106).

Selection of potential biomarkers

The selection of potential biomarkers for ADC drug

development is also challenging. Normal tissues and cells may also

partially express ADC targets, and therefore ADC payloads may have

serious side effects on these normal cells (15). The biomarker should preferably be

present only on tumor cells or tumor tissue and not expressed in

normal cells and tissues. Uniform criteria to determine the

expression level that accurately predicts ADC efficacy are lacking.

For example, in the case of gosatuzumab, the TROP-2 ADC drug,

although TROP-2 expression is associated with efficacy, the exact

threshold of expression needs to be further defined with more

sufficient evidence. In addition, the biomarker expression of

different cells within the same tumor may vary or the biomarker

expression levels of the same types of tumors originating from

different patients may be different due to the existence of

intra-tumor and inter-tumor heterogeneity. All of these increase

the difficulty in finding universal biomarkers (107), making the selection of specific

targets highly challenging. Moreover, the tumor cells lacking a

specific target can proliferate rapidly in the presence of ADCs,

leading to a new round of recurrence and drug resistance (108), again demonstrating the importance

of finding tumor-specific targets.

Limitations of clinical trials

Current clinical trials are mostly limited to the

efficacy of ADC monotherapy. The information on the safety and

toxicity of monotherapy and the efficacy of combination therapy is

still in the preliminary stages. First, like-for-like comparisons

of newer ADC drugs with standard-of-care or other comparable ADC

drugs in clinical trials are scarce, limiting their status and

superiority in their class and creating difficulties in dosing

choices for clinicians and patients. Second, the maximum tolerated

dose is usually derived from safety data in phase I trials.

However, the cumulative toxicity of a drug may not be apparent

until after multiple courses of therapy, which needs further

investigation. In addition, the complexity of the design of

sequencing, dosage and duration of combination therapy, as well as

the lack of established theoretical and practical guidance, makes

the design and implementation of clinical trials more

difficult.

Practical challenges in clinical

practice

A number of other novel approaches to tumor

treatment are currently available, which include tumor cell

therapy, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (109), T-cell receptor engineered T-cell

therapy (110), tumor-infiltrating

lymphocyte therapy (111), ICI

therapies, therapies using gene editing techniques such as

CRISPR-Cas9 (112) and oncolytic

virotherapy (113). ADCs have

shown good efficacy in treating various hematological malignancies

and solid tumors, with relatively good safety, controllable adverse

effects and fewer serious adverse effects such as cytokine release

syndrome (114). The precise

delivery mechanism, excellent therapeutic effect and safety of ADC

indicate its great developmental potential in the field of tumor

therapy and wide recognition in the tumor therapy market.

However, the development of ADCs faces several

practical challenges in clinical practice. First, comprehensive

patient stratification from both clinical and molecular

characteristics is needed for specific clinical applications.

Besides determining the molecular typing of the patient's tumor

cells to select sensitive ADC drugs, the patient's general

conditions, such as age, physical status and comorbidities, and

other tumor-related characteristics, such as tumor site, size,

stage and metastasis, need to be comprehensively considered. For

example, the tolerability of ADC therapy may need to be more

carefully evaluated in patients with advanced stage and poor

physical status. Further, patient tumor samples can be

comprehensively analyzed using multi-omics technologies, such as

genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, to mine

highly specific and sensitive biomarker combinations for

individualized and precise treatment. Second, as ADCs are

expensive, a study suggested a reduction in total drug acquisition

costs by at least 50% to make it a cost-effective strategy

(115). The present study

recommends using advanced computer simulation and artificial

intelligence techniques to improve drug design and screening

efficiency, optimize research and development processes, and

enhance production by increasing coupling efficiency and product

purity, ultimately reducing research and development and

manufacturing costs.

Future perspectives of ADC therapy

Treatment of PROC remains a major challenge. Despite

the development of systemic therapies for ovarian cancer,

bevacizumab, PARP inhibitors and ICIs still fail to meet the

therapeutic needs of patients with PROC. ADC-specific delivery

payload reduces side effects and has been shown to be superior to

conventional monotherapy in PROC, resulting in patient benefits

(116). ADCs combined with

bevacizumab have displayed superior activity and tolerability in

PROC. Therefore, ADCs may become the preferred combination with

bevacizumab, providing a superior treatment option for patients

with PROC. However, the results from applications in other cancers

have shown that ADCs can eventually allow disease progression due

to the emergence of drug resistance. These ADC-resistant cells

remain sensitive to standard chemotherapeutic agents or other ADCs,

which suggests that ADC resistance can be overcome by the

appropriate use of other alternative drugs.

Several possible ways to overcome ADC resistance

have been proposed, such as the use of cytotoxic agents with poor

efflux potential and combinations with other drugs (117,118). With technological advancement,

dual-targeting ADCs and dual-drug ADCs have been further developed.

Dual-targeting ADCs can recognize and bind to two different targets

at the same time and also bind to tumor cells more precisely and

effectively, thus overcoming the therapeutic challenges posed by

tumor heterogeneity. These strategies are expected to reduce the

likelihood of tumor cells becoming resistant to treatment and

extend the effective duration of drug therapy (119). Dual-drug ADCs, on the contrary,

use two different cytotoxic drugs as payloads; more significant

antitumor activity can be obtained, and the occurrence of drug

resistance can be reduced by precisely controlling the ratio of the

two drugs (120). Enhancing the

bystander-killing effect by converting non-cleavable linkers into

cleavable linkers is also a way to overcome drug resistance

(105). Moreover, ADCs release

tumor-associated antigens while killing tumor cells, thus

activating the antitumor immune response, making ADCs synergistic

with ICIs (121). The combination

of the two can enhance the killing effect on tumor cells, thus

overcoming the drug resistance of ADCs. For example, one study has

shown that combining ADCs and ICIs can improve the ORR of patients,

prolong PFS and also have certain therapeutic effects on some

patients resistant to ADC in triple-negative breast cancer

(NCT03742102). These studies are expected to provide additional

insights into the optimal use of these agents.

The optimization of the ADC drug structure and

innovative developments are expected to further improve its

therapeutic efficacy and safety. Consequent to the ongoing

advancement of science and technology, the search for ADCs more

precisely targeting tumor cells and more stable in the circulation

may represent a prominent research focus in the future. The

continuous discovery and validation of new drug targets can propel

the advancement of ADCs, thereby broadening the range of ADC

applications in clinical settings. This may have a significant and

far-reaching impact on the landscape of cancer treatment. Combining

ADCs with various antitumor agents is a promising strategy that

needs further exploration and optimization to improve efficacy and

mitigate adverse effects. The current ADCs in PROC are primarily

directed toward high-grade plasmacytoid ovarian cancer. Further

studies may include other histological subtypes.

The safety and resistance after long-term drug use

needs to be further evaluated as research continues. At present,

the research on the discovery, related mechanisms and solutions of

drug resistance in ADC mainly focuses on breast cancer, lung cancer

and gastric cancer. The corresponding data on ovarian cancer is

still lacking. ADC resistance may be discovered in the future due

to reduced FRα expression. Therefore, inspiration should be drawn

from the studies on other cancers and actively address potential

drug resistance by developing novel ADC designs or implementing

appropriate alternative and combination therapies.

Conclusions

ADCs have demonstrated potent clinical activity in

PROC by selectively delivering cytotoxic drugs to tumor cells,

improving therapeutic efficacy and reducing toxicity. The approval

of MIRV for treating FRα-positive PROC has led to the rapid

evolution of ADC monotherapy and combination therapies, which

offers hope for patients with PROC. The gradual use of more

effective ADCs for treating PROC may be observed in the future.

The development of novel drugs that can more

accurately target tumor cells and are more stable in the

circulation will be the future pursuit of researchers. The possible

emergence of ADC resistance and the mechanism behind it during

clinical application should be considered, so as to more

effectively use ADCs as a weapon to optimize the therapeutic

regimens for patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

KS and SY were responsible for conceptualization,

data curation and writing the original draft. NS and FT

participated in the topic selection and were responsible for data

collection and analysis. SR and HaW were responsible for software

and validation, managing the literature and editing the table

section of the manuscript. YZ and YW were responsible for creating

the figure and participated in drafting the manuscript. HoW and HG

were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Matulonis UA, Sood AK, Fallowfield L,

Howitt BE, Sehouli J and Karlan BY: Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis

Primers. 2:160612016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

St Laurent J and Liu J: Treatment

approaches for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol.

42:127–133. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Davis A, Tinker AV and Friedlander M:

‘Platinum resistant’ ovarian cancer: What is it, who to treat and

how to measure benefit? Gynecol Oncol. 133:624–631. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C and Corvaïa

N: Strategies and challenges for the next generation of

antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 16:315–337. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tsuchikama K, Anami Y, Ha SYY and Yamazaki

CM: Exploring the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 21:203–223. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Drago JZ, Modi S and Chandarlapaty S:

Unlocking the potential of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer

therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:327–344. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dumontet C, Reichert JM, Senter PD,

Lambert JM and Beck A: Antibody-drug conjugates come of age in

oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22:641–661. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gonzalez-Ochoa E, Veneziani AC and Oza AM:

Mirvetuximab soravtansine in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer.

Clin Med Insights Oncol. 17:117955492311872642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Joubert N, Beck A, Dumontet C and

Denevault-Sabourin C: Antibody-Drug conjugates: The last decade.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 13:2452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mathe G, Tran BL and Bernard J: Effect on

mouse leukemia 1210 of a combination by diazo-reaction of

amethopterin and gamma-globulins from hamsters inoculated with such

leukemia by heterografts. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 246:1626–1628.

1958.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Perez HL, Cardarelli PM, Deshpande S,

Gangwar S, Schroeder GM, Vite GD and Borzilleri RM: Antibody-drug

conjugates: Current status and future directions. Drug Discov

Today. 19:869–881. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Khongorzul P, Ling CJ, Khan FU, Ihsan AU

and Zhang J: Antibody-drug conjugates: A comprehensive review. Mol

Cancer Res. 18:3–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Samantasinghar A, Sunildutt NP, Ahmed F,

Soomro AM, Salih ARC, Parihar P, Memon FH, Kim KH, Kang IS and Choi

KH: A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of

antibody drug conjugate. Biomed Pharmacother. 161:1144082023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Staudacher AH and Brown MP: Antibody drug

conjugates and bystander killing: Is antigen-dependent

internalisation required? Br J Cancer. 117:1736–1742. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dubowchik GM and Walker MA:

Receptor-mediated and enzyme-dependent targeting of cytotoxic

anticancer drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 83:67–123. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Doronina SO, Toki BE, Torgov MY,

Mendelsohn BA, Cerveny CG, Chace DF, DeBlanc RL, Gearing RP, Bovee

TD, Siegall CB, et al: Development of potent monoclonal antibody

auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol.

21:778–784. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lee EK and Liu JF: Antibody-drug

conjugates in gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 153:694–702.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Teicher BA and Chari RV: Antibody

conjugate therapeutics: Challenges and potential. Clin Cancer Res.

17:6389–6397. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jain N, Smith SW, Ghone S and Tomczuk B:

Current ADC linker chemistry. Pharm Res. 32:3526–3540. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bargh JD, Isidro-Llobet A, Parker JS and

Spring DR: Cleavable linkers in antibody-drug conjugates. Chem Soc

Rev. 48:4361–4374. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kovtun YV, Audette CA, Ye Y, Xie H,

Ruberti MF, Phinney SJ, Leece BA, Chittenden T, Blättler WA and

Goldmacher VS: Antibody-drug conjugates designed to eradicate

tumors with homogeneous and heterogeneous expression of the target

antigen. Cancer Res. 66:3214–3221. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tsuchikama K and An Z: Antibody-drug

conjugates: Recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries.

Protein Cell. 9:33–46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dumontet C and Jordan MA:

Microtubule-binding agents: A dynamic field of cancer therapeutics.

Nat Rev Drug Discov. 9:790–803. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen H, Lin Z, Arnst KE, Miller DD and Li

W: Tubulin inhibitor-based antibody-drug conjugates for cancer

therapy. Molecules. 22:12812017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fuentes-Antrás J, Genta S, Vijenthira A

and Siu LL: Antibody-drug conjugates: In search of partners of

choice. Trends Cancer. 9:339–354. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Riccardi F, Dal Bo M, Macor P and Toffoli

G: A comprehensive overview on antibody-drug conjugates: From the

conceptualization to cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol.

14:12740882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fu Z, Li S, Han S, Shi C and Zhang Y:

Antibody drug conjugate: The ‘biological missile’ for targeted

cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kaplon H, Crescioli S, Chenoweth A,

Visweswaraiah J and Reichert JM: Antibodies to watch in 2023. MAbs.

15:21534102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yao P, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wei X, Liu Y, Du

C, Hu M, Feng C, Li J, Zhao F, et al: Knowledge atlas of

antibody-drug conjugates on CiteSpace and clinical trial

visualization analysis. Front Oncol. 12:10398822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Luhrs CA and Slomiany BL: A human

membrane-associated folate binding protein is anchored by a

glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol tail. J Biol Chem. 264:21446–21449.

1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen C, Ke J, Zhou XE, Yi W, Brunzelle JS,

Li J, Yong EL, Xu HE and Melcher K: Structural basis for molecular

recognition of folic acid by folate receptors. Nature. 500:486–489.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhao R, Min SH, Wang Y, Campanella E, Low

PS and Goldman ID: A role for the proton-coupled folate transporter

(PCFT-SLC46A1) in folate receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Biol

Chem. 284:4267–4274. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Cheung A, Opzoomer J, Ilieva KM, Gazinska

P, Hoffmann RM, Mirza H, Marlow R, Francesch-Domenech E, Fittall M,

Rodriguez DD, et al: Anti-Folate receptor alpha-directed antibody

therapies restrict the growth of triple-negative breast cancer.

Clin Cancer Res. 24:5098–5111. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ledermann JA, Canevari S and Thigpen T:

Targeting the folate receptor: Diagnostic and therapeutic

approaches to personalize cancer treatments. Ann Oncol.

26:2034–2043. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Heo YA: Mirvetuximab soravtansine: First

approval. Drugs. 83:265–273. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dilawari A, Shah M, Ison G, Gittleman H,

Fiero MH, Shah A, Hamed SS, Qiu J, Yu J, Manheng W, et al: FDA

approval summary: Mirvetuximab soravtansine-gynx for FRα-positive,

platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 29:3835–3840.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Oroudjev E, Lopus M, Wilson L, Audette C,

Provenzano C, Erickson H, Kovtun Y, Chari R and Jordan MA:

Maytansinoid-antibody conjugates induce mitotic arrest by

suppressing microtubule dynamic instability. Mol Cancer Ther.

9:2700–2713. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Moore KN, Martin LP, O'Malley DM,

Matulonis UA, Konner JA, Vergote I, Ponte JF and Birrer MJ: A

review of mirvetuximab soravtansine in the treatment of

platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Future Oncol. 14:123–136. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tomao F, D'Incalci M, Biagioli E,

Peccatori FA and Colombo N: Restoring platinum sensitivity in

recurrent ovarian cancer by extending the platinum-free interval:

Myth or reality? Cancer. 123:3450–3459. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ab O, Whiteman KR, Bartle LM, Sun X, Singh

R, Tavares D, LaBelle A, Payne G, Lutz RJ, Pinkas J, et al:

IMGN853, a folate receptor-α (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug

conjugate, exhibits potent targeted antitumor activity against

FRα-expressing tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 14:1605–1613. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Matulonis UA, Lorusso D, Oaknin A, Pignata

S, Dean A, Denys H, Colombo N, Van Gorp T, Konner JA, Marin MR, et

al: Efficacy and safety of mirvetuximab soravtansine in patients

with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer with high folate receptor

alpha expression: Results from the SORAYA study. J Clin Oncol.

41:2436–2445. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Martin LP, Konner JA, Moore KN, Seward SM,

Matulonis UA, Perez RP, Su Y, Berkenblit A, Ruiz-Soto R and Birrer

MJ: Characterization of folate receptor alpha (FRα) expression in

archival tumor and biopsy samples from relapsed epithelial ovarian

cancer patients: A phase I expansion study of the FRα-targeting

antibody-drug conjugate mirvetuximab soravtansine. Gynecol Oncol.

147:402–407. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Moore KN, Angelergues A, Konecny GE,

García Y, Banerjee S, Lorusso D, Lee JY, Moroney JW, Colombo N,

Roszak A, et al: Mirvetuximab soravtansine in FRα-positive,

platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 389:2162–2174.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sidaway P: Mirvetuximab soravtansine

superior to chemotherapy in platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian

cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 21:832024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Li X, Zhou S, Abrahams CL, Krimm S, Smith

J, Bajjuri K, Stephenson HT, Henningsen R, Hanson J, Heibeck TH, et

al: Discovery of STRO-002, a novel homogeneous ADC targeting folate

receptor alpha, for the treatment of ovarian and endometrial

cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 22:155–167. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Furuuchi K, Rybinski K, Fulmer J, Moriyama

T, Drozdowski B, Soto A, Fernando S, Wilson K, Milinichik A, Dula

ML, et al: Antibody-drug conjugate MORAb-202 exhibits long-lasting

antitumor efficacy in TNBC PDx models. Cancer Sci. 112:2467–2480.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Shimizu T, Fujiwara Y, Yonemori K, Koyama

T, Sato J, Tamura K, Shimomura A, Ikezawa H, Nomoto M, Furuuchi K,

et al: First-in-human phase 1 study of MORAb-202, an antibody-drug

conjugate comprising farletuzumab linked to eribulin mesylate, in

patients with folate receptor-α-positive advanced solid tumors.

Clin Cancer Res. 27:3905–3915. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Najjar MK, Manore SG, Regua AT and Lo HW:

Antibody-Drug conjugates for the treatment of HER2-positive breast

cancer. Genes (Basel). 13:20652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yan M, Schwaederle M, Arguello D, Millis

SZ, Gatalica Z and Kurzrock R: HER2 expression status in diverse

cancers: Review of results from 37,992 patients. Cancer Metastasis

Rev. 34:157–164. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Oh DY and Bang YJ: HER2-targeted

therapies-a role beyond breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

17:33–48. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ogitani Y, Aida T, Hagihara K, Yamaguchi

J, Ishii C, Harada N, Soma M, Okamoto H, Oitate M, Arakawa S, et

al: DS-8201a, A novel HER2-targeting ADC with a novel DNA

topoisomerase I inhibitor, demonstrates a promising antitumor

efficacy with differentiation from T-DM1. Clin Cancer Res.

22:5097–5108. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Mutlu L, McNamara B, Bellone S, Manavella

DD, Demirkiran C, Greenman M, Verzosa MSZ, Buza N, Hui P, Hartwich

TMP, et al: Trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201a), a HER2-targeting

antibody-drug conjugate, demonstrates in vitro and in vivo

antitumor activity against primary and metastatic ovarian tumors

overexpressing HER2. Clin Exp Metastasis. 41:765–775. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Meric-Bernstam F, Makker V, Oaknin A, Oh

DY, Banerjee S, González-Martín A, Jung KH, Ługowska I, Manso L,

Manzano A, et al: Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan in

patients With HER2-expressing solid tumors: Primary results from

the DESTINY-PanTumor02 phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 42:47–58.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Erickson BK, Zeybek B, Santin AD and Fader

AN: Targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in

gynecologic malignancies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 32:57–64. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Lipinski M, Parks DR, Rouse RV and

Herzenberg LA: Human trophoblast cell-surface antigens defined by

monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 78:5147–5150. 1981.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liu X, Deng J, Yuan Y, Chen W, Sun W, Wang

Y, Huang H, Liang B, Ming T, Wen J, et al: Advances in

Trop2-targeted therapy: Novel agents and opportunities beyond

breast cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 239:1082962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Okajima D, Yasuda S, Maejima T, Karibe T,

Sakurai K, Aida T, Toki T, Yamaguchi J, Kitamura M, Kamei R, et al:

Datopotamab deruxtecan, a novel TROP2-directed antibody-drug

conjugate, demonstrates potent antitumor activity by efficient drug

delivery to tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 20:2329–2340. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

McNamara B, Greenman M, Bellone S, Santin

LA, Demirkiran C, Mutlu L, Hartwich TMP, Yang-Hartwich Y, Ratner E,

Schwartz PE and Santin AD: Preclinical activity of datopotamab

deruxtecan, a novel TROP2 directed antibody-drug conjugate

targeting trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (TROP2) in ovarian

carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 189:16–23. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Janjigian YY, Oaknin A, Lang JM, Ciombor

KK, Ray-Coquard IL, Oza AM, Yonemori K, Xu RH, Zhao J, Gajavelli S,

et al: TROPION-PanTumor03: Phase 2, multicenter study of

datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) as monotherapy and in combination

with anticancer agents in patients (pts) with advanced/metastatic

solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 41:TPS31532023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Cheng WF, Huang CY, Chang MC, Hu YH,

Chiang YC, Chen YL, Hsieh CY and Chen CA: High mesothelin

correlates with chemoresistance and poor survival in epithelial

ovarian carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 100:1144–1153. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Golfier S, Kopitz C, Kahnert A, Heisler I,

Schatz CA, Stelte-Ludwig B, Mayer-Bartschmid A, Unterschemmann K,

Bruder S, Linden L, et al: Anetumab ravtansine: A novel

mesothelin-targeting antibody-drug conjugate cures tumors with

heterogeneous target expression favored by bystander effect. Mol

Cancer Ther. 13:1537–1548. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Santin AD, Vergote I, González-Martín A,

Moore K, Oaknin A, Romero I, Diab S, Copeland LJ, Monk BJ, Coleman

RL, et al: Safety and activity of anti-mesothelin antibody-drug

conjugate anetumab ravtansine in combination with

pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin in platinum-resistant ovarian

cancer: Multicenter, phase Ib dose escalation and expansion study.

Int J Gynecol Cancer. 33:562–570. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lheureux S, Alqaisi H, Cohn DE, Chern JY,

Duska LR, Jewell A, Corr B, Winer IS, Girda E, Crispens MA, et al:

A randomized phase II study of bevacizumab and weekly anetumab

ravtansine or weekly paclitaxel in platinum-resistant or refractory

ovarian cancer NCI trial#10150. J Clin Oncol. 40:55142022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Rottey S, Clarke J, Aung K, Machiels JP,

Markman B, Heinhuis KM, Millward M, Lolkema M, Patel SP, de Souza

P, et al: Phase I/IIa trial of BMS-986148, an anti-mesothelin

antibody-drug conjugate, alone or in combination with nivolumab in

patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 28:95–105.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Levan K, Mehryar M, Mateoiu C, Albertsson

P, Bäck T and Sundfeldt K: Immunohistochemical evaluation of

epithelial ovarian carcinomas identifies three different expression

patterns of the MX35 antigen, NaPi2b. BMC Cancer. 17:3032017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gerber DE, Infante JR, Gordon MS, Goldberg

SB, Martín M, Felip E, Garcia MM, Schiller JH, Spigel DR, Cordova

J, et al: Phase Ia study of anti-NaPi2b antibody-drug conjugate

lifastuzumab vedotin DNIB0600A in patients with non-small cell lung

cancer and platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

26:364–372. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Moore KN, Birrer MJ, Marsters J, Wang Y,

Choi Y, Royer-Joo S, Lemahieu V, Armstrong K, Cordova J, Samineni

D, et al: Phase 1b study of anti-NaPi2b antibody-drug conjugate

lifastuzumab vedotin (DNIB0600A. in patients with

platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

158:631–639. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Banerjee S, Oza AM, Birrer MJ, Hamilton

EP, Hasan J, Leary A, Moore KN, Mackowiak-Matejczyk B, Pikiel J,

Ray-Coquard I, et al: Anti-NaPi2b antibody-drug conjugate

lifastuzumab vedotin (DNIB0600A) compared with pegylated liposomal

doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer in a

randomized, open-label, phase II study. Ann Oncol. 29:917–923.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Suzuki H, Nagase S, Saito C, Takatsuka A,

Nagata M, Honda K, Kaneda Y, Nishiya Y, Honda T, Ishizaka T, et al:

Raludotatug deruxtecan, a CDH6-targeting antibody-drug conjugate

with a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor DXd, is efficacious in human

ovarian and kidney cancer models. Mol Cancer Ther. 23:257–271.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Gitto SB, Whicker M, Davies G, Kumar S,

Kinneer K, Xu H, Lewis A, Mamidi S, Medvedev S, Kim H, et al: A

B7-H4-targeting antibody-drug conjugate shows antitumor activity in

PARPi and platinum-resistant cancers with B7-H4 expression. Clin

Cancer Res. 30:1567–1581. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Ponte JF, Ab O, Lanieri L, Lee J, Coccia

J, Bartle LM, Themeles M, Zhou Y, Pinkas J and Ruiz-Soto R:

Mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853), a folate receptor

alpha-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, potentiates the activity

of standard of care therapeutics in ovarian cancer models.

Neoplasia. 18:775–784. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Quanz M, Hagemann UB, Zitzmann-Kolbe S,

Stelte-Ludwig B, Golfier S, Elbi C, Mumberg D, Ziegelbauer K and

Schatz CA: Anetumab ravtansine inhibits tumor growth and shows

additive effect in combination with targeted agents and

chemotherapy in mesothelin-expressing human ovarian cancer models.

Oncotarget. 9:34103–34121. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Moore KN, O'Malley DM, Vergote I, Martin

LP, Gonzalez-Martin A, Malek K and Birrer MJ: Safety and activity

findings from a phase 1b escalation study of mirvetuximab

soravtansine, a folate receptor alpha (FRalpha)-targeting

antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), in combination with carboplatin in

patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

151:46–52. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Jain RK: Normalization of tumor

vasculature: An emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy.

Science. 307:58–62. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Haunschild CE and Tewari KS: Bevacizumab

use in the frontline, maintenance and recurrent settings for

ovarian cancer. Future Oncol. 16:225–246. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Pignata S, Lorusso D, Joly F, Gallo C,

Colombo N, Sessa C, Bamias A, Salutari V, Selle F, Frezzini S, et

al: Carboplatin-based doublet plus bevacizumab beyond progression

versus carboplatin-based doublet alone in patients with

platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: A randomised, phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol. 22:267–276. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

O'Malley DM, Matulonis UA, Birrer MJ,

Castro CM, Gilbert L, Vergote I, Martin LP, Mantia-Smaldone GM,

Martin AG, Bratos R, et al: Phase Ib study of mirvetuximab

soravtansine, a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug

conjugate (ADC), in combination with bevacizumab in patients with

platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 157:379–385.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Gilbert L, Oaknin A, Matulonis UA,

Mantia-Smaldone GM, Lim PC, Castro CM, Provencher D, Memarzadeh S,

Method M, Wang J, et al: Safety and efficacy of mirvetuximab

soravtansine, a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug

conjugate (ADC), in combination with bevacizumab in patients with

platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 170:241–247.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Richardson DL, Moore KN, Vergote I,

Gilbert L, Martin LP, Mantia-Smaldone GM, Castro CM, Provencher D,

Matulonis UA, Stec J, et al: Phase 1b study of mirvetuximab

soravtansine, a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug

conjugate, in combination with carboplatin and bevacizumab in

patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

185:186–193. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Nicolò E, Giugliano F, Ascione L,

Tarantino P, Corti C, Tolaney SM, Cristofanilli M and Curigliano G:

Combining antibody-drug conjugates with immunotherapy in solid

tumors: current landscape and future perspectives. Cancer Treat

Rev. 106:1023952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Gerber HP, Sapra P, Loganzo F and May C:

Combining antibody-drug conjugates and immune-mediated cancer

therapy: What to expect? Biochem Pharmacol. 102:1–6. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Vafa O, Gilliland GL, Brezski RJ, Strake

B, Wilkinson T, Lacy ER, Scallon B, Teplyakov A, Malia TJ and

Strohl WR: An engineered Fc variant of an IgG eliminates all immune

effector functions via structural perturbations. Methods.

65:114–126. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Bauzon M, Drake PM, Barfield RM, Cornali

BM, Rupniewski I and Rabuka D: Maytansine-bearing antibody-drug

conjugates induce in vitro hallmarks of immunogenic cell death

selectively in antigen-positive target cells. Oncoimmunology.

8:e15658592019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Müller P, Martin K, Theurich S, Schreiner

J, Savic S, Terszowski G, Lardinois D, Heinzelmann-Schwarz VA,

Schlaak M, Kvasnicka HM, et al: Microtubule-depolymerizing agents

used in antibody-drug conjugates induce antitumor immunity by

stimulation of dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2:741–755.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Iwata TN, Ishii C, Ishida S, Ogitani Y,

Wada T and Agatsuma T: A HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate,

trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201a), enhances antitumor immunity in a

mouse model. Mol Cancer Ther. 177:1494–1503. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Junttila TT, Li G, Parsons K, Phillips GL

and Sliwkowski MX: Trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1. retains all the

mechanisms of action of trastuzumab and efficiently inhibits growth

of lapatinib insensitive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

128:347–356. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wu S, Ge A, Deng X, Liu L and Wang Y:

Evolving immunotherapeutic solutions for triple-negative breast

carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 130:1028172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Bardia A, Mayer IA, Diamond JR, Moroose

RL, Isakoff SJ, Starodub AN, Shah NC, O'Shaughnessy J, Kalinsky K,

Guarino M, et al: Efficacy and safety of anti-trop-2 antibody drug

conjugate sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132) in heavily pretreated

patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 35:2141–2148. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Camidge DR, Barlesi F, Goldman JW,

Morgensztern D, Heist R, Vokes E, Angevin E, Hong DS, Rybkin II,

Barve M, et al: A phase 1b study of telisotuzumab vedotin in

combination with nivolumab in patients with NSCLC. JTO Clin Res

Rep. 3:1002622022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Anastasio MK, Shuey S and Davidson BA:

Antibody-drug conjugates in gynecologic cancers. Curr Treat Options

Oncol. 25:1–19. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Wang Y, Liu L, Jin X and Yu Y: Efficacy

and safety of mirvetuximab soravtansine in recurrent ovarian cancer

with FRa positive expression: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 194:1042302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, Park YH, Kim

SB, Tamura K, Andre F, Iwata H, Ito Y, Tsurutani J, et al:

Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast

cancer. N Engl J Med. 382:610–621. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Kumagai K, Aida T, Tsuchiya Y, Kishino Y,

Kai K and Mori K: Interstitial pneumonitis related to trastuzumab

deruxtecan, a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeting

Ab-drug conjugate, in monkeys. Cancer Sci. 111:4636–4645. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Swain SM, Nishino M, Lancaster LH, Li BT,