Introduction

Cervical cancer remains the fourth leading cause of

cancer-related incidence and mortality, with 660,000 new cases and

350,000 deaths among women worldwide in 2022 (1). Despite ongoing advancements in disease

management, patient prognosis is influenced by multiple individual

factors, highlighting the urgent need for personalized therapeutic

strategies guided by reliable prognostic and predictive biomarkers

(2–4).

In this context, the cancer cell surface proteome

(surfaceome) has emerged as a critical area of study due to its

role in tumor progression and treatment response. Defined as the

complete set of plasma membrane proteins with at least one amino

acid residue exposed to the extracellular space (5), the surfaceome facilitates the

selective movement of substances and serves as an anchoring base

for the cytoskeleton, and its structure influences crucial

signaling processes triggered by interactions between cells and the

extracellular matrix. The surfaceome includes receptors,

transporters, channels, cell-adhesion proteins and enzymes, making

it a rich source of potential diagnostic biomarkers and important

targets for therapeutic interventions.

Interferon-induced transmembrane proteins (IFITMs)

are small Dispanin proteins containing two (trans) membrane helices

that localize in the plasma membrane and endosomal/lysosomal

membranes (6). Immunity-related

IFITMs (IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3) are highly homologous, but they

differ in their subcellular localization and function, as

demonstrated in recent years (7,8).

IFITM1 differs from IFITM2 and IFITM3 by a 21-amino acid truncation

at the N-terminus and a 13-amino acid extension at the C-terminus.

Unlike IFITM2 and IFITM3, which are predominantly found in

endosomal membranes, IFITM1 is localized primarily in the plasma

membrane on the cell surface.

Immunity-related IFITMs are strongly induced by type

I and type II interferons (IFNs) and function mainly as restriction

factors that block viral infections. They also play an important

role in cancer progression (6,9–11).

Although the exact mechanisms of their function remain unknown,

IFITMs influence membrane structure and function (12–14),

the intracellular trafficking of endocytosed cargo (15), and pH regulation within the

vesicular environment (16,17). These processes are crucial for

regulating surface protein expression, trafficking and recycling,

leading us to hypothesize that IFITM1 could modulate surfaceome

composition.

The aim of the present study was to elucidate the

mechanisms by which IFITMs contribute to tumor progression. Initial

investigations revealed that the suppression of IFITM1 in cervical

cancer cells affects the levels of members of the IFN-related DNA

damage resistance signature (IRDS) (18), including major histocompatibility

complex class I (MHC-I), suggesting a possible explanation for the

inverse correlation between metastasis formation and IFITM1/3

expression in cervical cancer tissues. Building on these findings,

the authors focused on the cell surface proteome and, for the first

time to the best of our knowledge, it was demonstrated how IFITM1

levels impact the cervical cancer cell surfaceome and associated

cell phenotype.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

SiHa cell line [cat. no. HTB-35; American Type

Culture Collection (ATCC)] was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (cat.

no. R4130; MilliporeSigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(cat. no. S-FBS-SA-015; Serana Europe GmbH) and

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. XC-A4122; Biosera) at 37°C with

5% CO2. The cells were passaged every two days using

Accutase (cat. no. A6964; MilliporeSigma). Cell line authentication

(STR profiling) and mycoplasma testing were performed

regularly.

The lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to

generate single- and double-IFITM1- and IFITM3-knockout (KO) cells.

The generation and characterization of IFITM1- and IFITM3-KO SiHa

clones were described previously (18). SiHa wild-type (wt) and SiHa

scrambled cells served as controls. SiHa scrambled control was

generated using the CRISPR/Cas method with sgRNA that lacks a

complementary sequence in the genome. For all methods used to

evaluate the effect of IFNγ, the cells were treated with human IFNγ

recombinant protein (cat. no. PHC4031; Gibco™; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at a concentration of 100 ng/ml for 24 h. SiHa

cell line exhibits baseline IFN pathway activity, and the IFNγ

concentration used ensures effective and measurable exogenous

pathway stimulation, as confirmed by the detection of

IFN-stimulated protein levels following treatment with increasing

IFNγ concentrations.

Pulse stable isotope labeling with

amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), biotinylation and isolation of

cell surface proteins

For pulse SILAC, SiHa wt and IFITM1 KO cells (clones

no. I, II and IV) were cultured in biological triplicates for 24 h

on 10-cm plates in R6K4 RPMI SILAC medium (cat. no. SM022; Gemini

Biosciences) containing 13C-labeled arginine and 2D labeled lysine

supplemented with dialyzed FBS (cat. no. A3382001; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and penicillin-streptomycin. Three

independently created clones (no. I, II and IV) were used as

biological replicates of IFITM1 KO cells to minimize the effect of

clonal selection. The cells from 3×10 cm-well plates were harvested

with Accutase, rinsed in ice-cold PBS and incubated with 0.8 mM

cell impermeable EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (cat. no. 21331;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in PBS for 10 min. After

centrifugation at 200 × g/4°C/5 min, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) was added

to quench the excess Sulfo-NHS-SS Biotin. After washing in PBS, the

cell pellets were suspended in lysis buffer (2% NP-40, 0.2% SDS, 10

mM EDTA, 108 mM oxidized glutathione, 1X protease inhibitor mix)

and incubated on ice for 30 min. Biotinylated proteins were

incubated with Pierce high-capacity streptavidin agarose (cat. no.

20359; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h; washed 3 times in

Buffer A (1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM oxidized glutathione), 2 times

in Buffer B (10% SDS, 5 mM oxidized glutathione), 2 times in Buffer

C (2 M NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM oxidized glutathione, heated to 40°C)

and 4 times in Buffer D (50 mM Tris (pH 8), 5 mM oxidized

glutathione); and then eluted with 200 mM DTT reducing agent in 125

mM Tris (pH 6.8) for 5 min at 85°C.

MS analysis

Peptide generation using FASP

Proteins were digested using a filter-aided sample

preparation protocol (FASP) (19).

Briefly, whole material obtained from enriched cell surface

proteins was loaded on Microcon Ultracel-30 spin filter columns

with a 30-kDa cutoff (MilliporeSigma). Urea buffer (8 M urea in 0.1

M Tris, pH 8.5) was added to the filter column, which was

subsequently centrifuged at 14,000 × g/20°C/15 min. Protein

reduction was performed via the addition of 100 mM Tris

(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (MilliporeSigma) in urea

buffer at 37°C/30 min/600 rpm in a thermomixer. The column was

centrifuged at 14,000 × g/20°C/15 min, and free sulfhydryl groups

were alkylated using 300 mM iodoacetamide in urea buffer

(MilliporeSigma). Protein alkylation was performed in the dark for

20 min, followed by another centrifugation at 14,000 × g/15 min.

Ammonium bicarbonate was added to the column (final concentration

of 10 µM), followed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g/20 min. Trypsin

(Promega Corporation) was added at a 1:100 ratio, and the proteins

were digested overnight at 37°C. The columns were centrifuged at

14,000 × g/15 min, and the peptides were desalted on C18 Micro spin

columns (Harvard Apparatus).

LC-MS/MS analyses

The samples were separated using an UltiMate 3000

rapid separation liquid chromatography (RSLC) nano chromatograph

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Peptides were loaded on a

precolumn (µ-precolumn, 30 m i.d., 5 mm length, C18 PepMap 100, 5

µm particle size, 100 Å pore size) and further separated on an

Acclaim PepMap RSLC column (75 µm i.d., length 250 mm, C18,

particle size 2 µm, pore size 100 Å) with a flow rate of 300 nl/min

using a linear gradient of B (80% acetonitrile in 0.08% aq. formic

acid) in A (0.1% aq. formic acid): 2% B for 4 min, 2–40% B for 64

min, 40–98% B for 2 min, with A (0.1% aq. formic acid) and B (80%

acetonitrile in 0.08% aq. formic acid). Peptides eluted from the

column were introduced into an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) operating in the Top20

data-dependent acquisition mode. A survey scan of 400–2,000 m/z was

performed at 120,000 resolution with an AGC target of

1×106 and a 200 ms injection time, followed by 20

data-dependent MS2 scans performed in the LTQ linear ion trap with

1 microscan, a 10 ms injection time and 10,000 AGC.

Database searching and data

evaluation

The mass spectrometry data were processed using

Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), version 2.2,

for SILAC-labeled samples. For the raw files of each triplicate

sample set, a consensus workflow was applied, consisting of the

following sequential nodes: the Minora feature detector, the

Precursor Ion Quantifier, and the Feature Mapper. Data processing

was performed using the Sequest HT engine with the following search

settings: database Swiss-Prot TaxID=9606, 2017-10-25, sequences

42252, taxonomy: Homo sapiens (updated September 2019) and database

with contaminants: PD_Contaminants_2015_5fasta; enzyme trypsin; 2

missed cleavage sites; precursor mass tolerance 10 ppm; fragment

mass tolerance 0.6 Da; static modification carbamidomethyl [+57.02

Da, (C)], label 13C(6) [+6.020 Da

(R)] and label 2H(4) [+4.025 Da

(K)]; dynamic modifications oxidation [+15.995 Da (M)], Met-loss +

Acetyl [protein terminus, −89.030 Da (M)]. The results were further

validated using the Percolator algorithm (version integrated in

Proteome Discoverer 2.2), which applies semi-supervised machine

learning for peptide-spectrum match validation and false discovery

rate (FDR) estimation, with a FDR threshold of 1%. For the protein

quantification and statistical assessment of the biological

triplicates, the Precursor Ions Quantifier was applied with the

following parameters: using only unique peptides and razor

peptides, normalization on total peptide amount, pairwise ratio

calculation and ANOVA (background-based) hypothesis test. The

relative quantification value is represented as the relative peak

area of the peptides with heavy isotope labels in SiHa wt cells

compared with IFITM1 KO cells or cells treated with IFNγ compared

with control SiHa cells without any treatment (Appendix S1). The normalized peptide

abundances were used to calculate the statistical significance of

differences between groups (wt vs. IFITM1 KO; untreated vs.

IFNγ-treated samples) using an unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed using

DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (20), and protein-protein interactions were

mapped using STRING database (21).

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the

ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE repository (22) with the dataset identifier PXD053951

and the following access login credentials: Username: reviewer_pxd053951@ebi.ac.uk;

Password: ouMaYQI4Qg6T.

Flow cytometry

The cells were harvested using Accutase, washed in

1% BSA (cat. no. A3059; MilliporeSigma) in PBS, and incubated with

PE-conjugated anti-CD166 monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 12-1668-42)

or FITC-conjugated anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (cat. no.

11-0409-42; both from Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

for 30 min on ice in the dark. After a second wash, the cells were

resuspended in 1% BSA in PBS and measured with a FACSVerse

instrument (BD Biosciences). The results were analyzed using

FACSSuite (BD Biosciences). Statistical analysis was performed

using an unpaired t-test with data from three biological

replicates.

Protein extraction, PAGE and western

blotting

The cells were scraped into 1X LDS lysis buffer on

ice: 105 mM Tris hydrochloride, 140 mM Tris base, 75 mM LDS, 0.5 mM

EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. 78429;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 0.1 mM PMSF (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The samples were frozen after lysis. The cell

lysates were sonicated and cleared by centrifugation (20,000 × g/30

min/4°C). The total protein concentration was measured using a DC

protein assay (cat. no. 5000112; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Appropriate amounts of cell lysates were mixed with DTT

(MilliporeSigma) to a final concentration of 100 mM and 4X NuPAGE

LDS Sample Buffer (cat. no. NP0008; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and then heated at 95°C for 10 min. Samples (20

µg/lane) were loaded into 10% polyacrylamide gels, separated by

molecular weight, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes

using the Mini-PROTEAN system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The

membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk in phosphate-buffered

saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) at room temperature for 1 h and

incubated with primary antibodies diluted in milk buffer overnight

at 4°C. After washing in PBST, the membranes were incubated at room

temperature for 1 h with HRP-linked secondary antibodies. After

washing in PBST and PBS, the chemiluminescent signal was visualized

using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents and a G:BOX Chemi

XRQ image analysis system and software (Syngene). Fiji ImageJ

software v. 2.14.0/1.54f (National Institutes of Health) (23) was used to quantify the signal

intensity of individual proteins relative to the intensity of the

loading control β-actin.

The primary antibodies and their dilutions used were

as follows: anti-IFITM1 (1:1,000; 5B5E2; cat. no. 60074-1-Ig;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-IFITM2 (1:500; 3D5F7; cat. no.

66137-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-IFITM3 (1:1,000; D8E8G;

cat. no. 59212; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-CD166

(1:1,000; EPR2759(2); cat. no. ab109215; Abcam) and anti-β-actin

(1:5,000; cat. no. MA1-140; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

The secondary antibodies used were as follows:

anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000; cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.) and anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch

Laboratories, Inc.).

Migration and invasion assays

For the wound healing assay, cells

(7×105) were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated in

complete growth medium for 48 h. To inhibit cell proliferation and

avoid serum-free starvation conditions, the cells were treated with

mitomycin C (10 µg/ml; M5353; MilliporeSigma) and incubated for 2 h

at 37°C (24). The cells were then

scratched and washed twice with PBS. To observe cell migration, the

cells were cultivated in complete growth medium, and images were

captured at time 0 (t0) and after 24 h (t24)

using an Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope (Nikon Corporation) at

×100 magnification. Fiji ImageJ software (23) with the Wound healing size tool

plugin (25) was used for scratch

area quantification. The migration rate (%) was calculated as

[(scratch area t0-scratch area t24)/scratch

area t0)]*100. The assay was repeated in biological

triplicate (each in technical duplicate), and statistical analysis

was conducted using an unpaired t-test.

For the Transwell migration assay, a

1×105 cell suspension in serum-free RPMI was placed in

the top chamber of each insert (cat. no. 140620; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Complete RPMI medium was added to the lower

chambers. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After

incubation, the cells on the upper surface of the inserts were

removed, and the membranes were fixed with 70% ethanol at room

temperature for 15 min. The migratory cells were stained with 0.5%

crystal violet for 15 min. Images of the stained cells were

captured using an Eclipse Ti-S microscope (Nikon Corporation). The

number of migratory cells was calculated as an average of 5 fields

of view (100× magnification) in each of the independent

triplicates, and statistical analysis was conducted using an

unpaired t test.

To evaluate the invasion potential of the cells, a

3D Matrigel drop invasion assay was performed as established by

Aslan et al (26). Images

were captured 6 days after drop formation using an EVOS™ FL Digital

Inverted Microscope (Invitrogen™; objective magnification, ×4), and

the invasion area (mm2) per field of view was calculated

using Fiji ImageJ software (23).

Two independent fields of view were evaluated for each drop. The

assay was repeated in independent biological duplicates, each in

technical triplicates, and statistical analysis was conducted using

an unpaired t-test.

Cervicosphere formation assay

Cells were seeded in ultralow attachment plates

(Corning, Inc.) at a density of 10,000 viable cells per well using

a FACSAria III. The cells were cultured in K-SFM (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with B27 (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 10 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor

(MilliporeSigma) and 10 ng/ml bFGF (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The cells were then cultivated for 10 days.

Images of the formed spheres were captured using an EVOS™ FL

Digital Inverted Microscope (Invitrogen™; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.; objective magnification, ×4), and the total number of spheres

per well was determined. The sphere size was evaluated using Fiji

ImageJ software (23) with a lower

threshold of 6,000 µm2. The assay was repeated in

independent biological triplicates, and statistical analysis was

conducted using an unpaired t test.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Cells (1×106) were seeded into 60 mm cell

culture dishes and incubated overnight in complete RPMI. The cells

were then treated with IFNγ (100 ng/ml; cat. no. PHC4031; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and further incubated for 24 h. RNA

was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (cat. no. 74104; Qiagen) and

transcribed into cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse

Transcription Kit (cat. no. 4368814, Applied Biosystems™; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Luna® Universal qPCR Master Mix (NEB) was used with 20 ng of cDNA

per 10 µl reaction in a 384-well plate, along with specific primers

(sequences below). Primers specific to ACTB were used as an

endogenous control. The thermocycling conditions recommended by the

master mix manufacturer were applied. qPCR was performed, and the

results were analyzed using the QuantStudio 5 system (Applied

Biosystems™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Relative gene

expression was quantified using the ΔΔCq method (2−ΔΔCq)

(27) from biological triplicates,

each with technical triplicates. The SiHa wt control was chosen as

the reference sample. Statistical analysis was conducted using the

unpaired t-test to compare IFITM1 KO samples vs. scrambled ctrl

(significance levels indicated by asterisks) and untreated (CTRL)

vs. IFNγ-treated (IFNγ) samples (indicated by hashtags) separately.

Primer sequences were as follows: IFITM1 forward,

5′-AGCACCATCCTTCCAAGGTCC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TAACAGGATGAATCCAATGGTC-3′; HLA-A forward,

5′-AAGTGGGAGGCGGCCCATGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-ATGTGTCTTGGGGGGGTCCGT-3′; HLA-B forward,

5′-ACTGAGCTTGTGGAGACCAGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCAGCCCCTCATGCTGT-3′;

HLA-C forward, 5′-ATCGTTGCTGGCCTGGCTGTCCT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCATCAGAGCCCTGGGCACTGTT-3′; IGF2R forward,

5′-TTGAGTGGCGAACGCAGTATGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CAGTGATGGCTTCCCAGTTGTC-3′; M6PR forward,

5′-CTCCAGTCCCTCATCTCACC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGCCTGCTACACCATTTTGC-3′;

sortilin 1 (SORT1) forward, 5′-AGTTTCAGTGACCCACGTCAG and reverse,

5′-AGTAGGTCAGGTAACAAAGTCCAGT-3′; CD166/ALCAM forward,

5′-GAACACGATGAGGCAGACGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-TTCCATATTACCGAGGTCCTTGT-3′; CD40 forward,

5′-CTGGTCTCACCTCGCTATGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCAGTGGGTGGTTCTGGAT-3′;

CD276 forward, 5′-GGAGAATGCAGGAGCTGAGG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCCAGAGGGTAGGAGCTGTA-3′; and ACTB forward,

5′-GGAACGGTGAAGGTGACAGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-ACCTCCCCTGTGTGGACTTG-3′.

Natural killer (NK) cytotoxicity

assay

The NK-92 cell line purchased from ATCC (cat. no.

CRL-2407) was cultured in Alpha Minimum Essential Medium without

ribonucleosides and deoxyribonucleosides (cat. no. 22561021; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol

(cat. no. I7508; MilliporeSigma), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (cat.

no. 21985023; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 0.02 mM folic

acid (cat. no. F8758; MilliporeSigma), 200 U/ml recombinant IL-2

(cat. no. PHC0026; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 25% FBS

and penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. The

cells were passaged regularly every 2 days at a concentration of

2–3×105 viable cells/ml. SiHa cells intended for

cocultivation were washed and resuspended in PBS to a concentration

of 1×106 cells/ml. The cells were stained with CFSE

solution (cat. no. 565082; BD Biosciences) at a final concentration

of 2 µM in a 37°C water bath for 10 min. The cells were then washed

thoroughly in PBS and complete RPMI. A total of 6×104

cells per well were seeded in 24-well plates and allowed to grow

overnight. The following day, complete RPMI was added to an NK-92

cell culture at a 1:1 ratio, and NK-92 cells were added at the

indicated ratios to the CFSE-stained SiHa cells. The cell lines

alone without coculture were used as controls. After 4 h of

co-cultivation at 37°C with 5% CO2, SiHa cells were

harvested with Accutase and mixed with collected medium containing

NK-92 and dead SiHa cells. Dead cells stained with 7-AAD (cat. no.

559925; BD Biosciences) for 10 min were analyzed by FACSVerse (BD

Biosciences). The dead SiHa cells were gated as the

CFSE+ 7-AAD+ population (Figs. S1 and S3). Statistical analysis was performed

using the unpaired t-test with data from three biological

replicates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between two groups were

analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. For proteomic data

analysis, one-way ANOVA with background-based hypothesis testing

(as implemented in Proteome Discoverer 2.2) was applied, followed

by unpaired two-tailed t-tests for specific pairwise comparisons.

Data is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using

GraphPad Prism version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software; Dotmatics).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

IFITM1 modulates the cervical cancer

cell surfaceome in both IFNγ-dependent and IFNγ-independent

manners

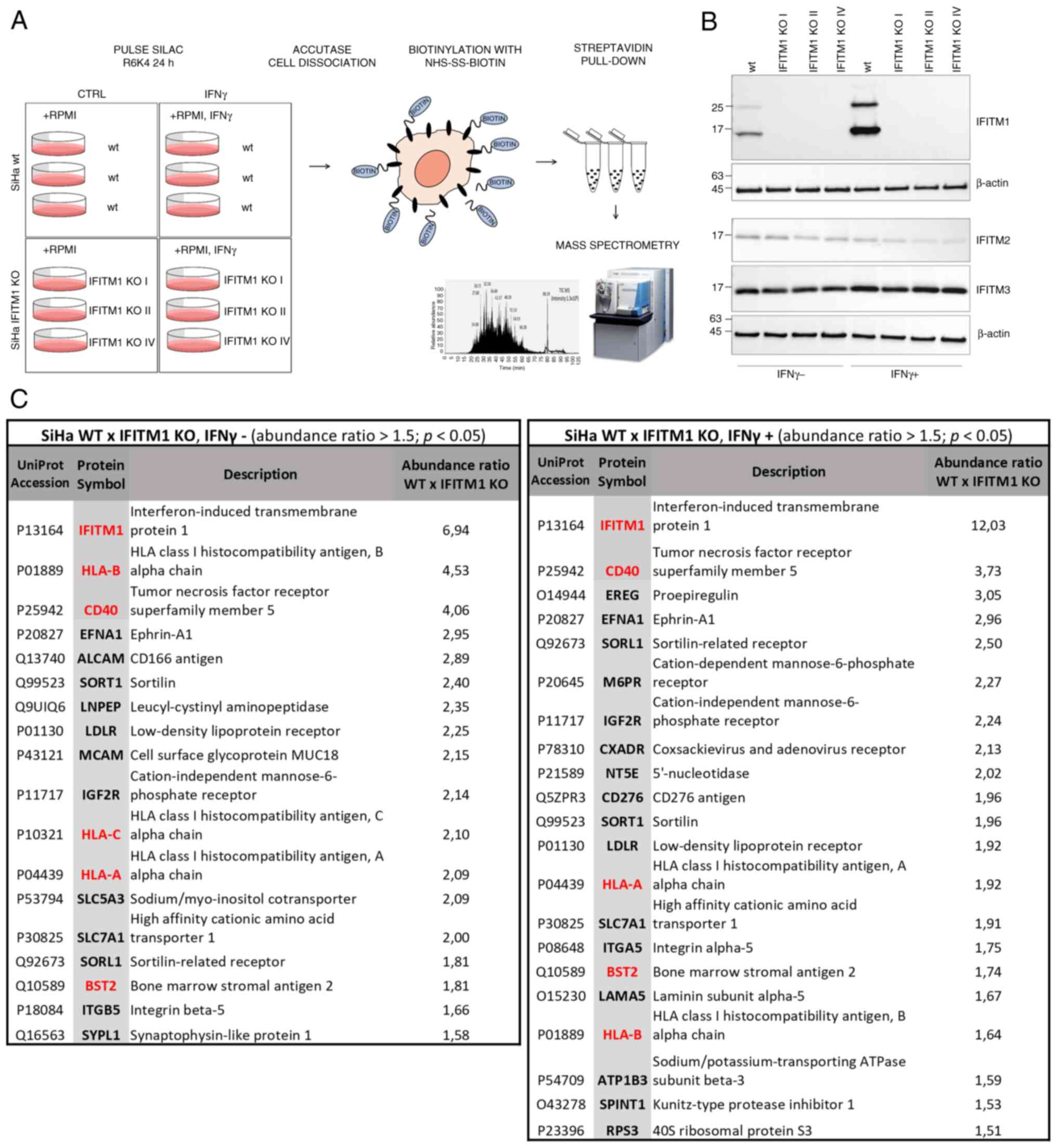

To investigate the IFITM1-regulated cancer cell

surfaceome, we used the SiHa cervical cancer cell line, which

expresses relatively high levels of IFITM1 protein even without IFN

stimulation. In a previous study, it was demonstrated by the

authors that IFITM1 regulates the surface expression of human

leukocyte antigen B (HLA-B) in this cell line (18). IFITM1 KO SiHa cells were generated

using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, and their preparation and

characterization were performed as described previously (18).

To identify and quantify cell surface proteins whose

levels differ between SiHa wt and IFITM1 KO cells, a proteomic

approach was employed, combining SILAC, membrane protein isolation,

and MS analysis (Fig. 1A). To

capture proteins regulated only after IFN induction of IFITM1,

cells were treated with IFNγ alongside SILAC medium, allowing

protein turnover analysis. To minimize clonal selection bias, three

independently generated IFITM1 KO cell clones were used as

biological replicates (Fig. 1B).

Western blot analysis of IFITM1 levels revealed an additional

higher-molecular-weight band (~25 kDa) alongside the expected

15-kDa band. This band likely represents an IFITM1 dimer or a

post-translationally modified form of IFITM1, as previously

reported (6,28). In addition to IFITM1, the expression

of the related proteins IFITM2 and IFITM3 was examined, as they are

often affected in KO studies due to their high sequence similarity.

Western blot analysis confirmed that IFITM2 and IFITM3 expression

was preserved in IFITM1 KO clones. However, a slight decrease in

the protein levels is evident, particularly in the presence of

IFNγ. This may be a consequence of the tight co-regulation within

the IFITM family (6).

A set of proteins that were significantly

downregulated in IFITM1 KO cells with a fold change ≥1.5 and a

significance level of P<0.05 were identified and quantified: 18

proteins without IFNγ treatment and 21 proteins after IFNγ

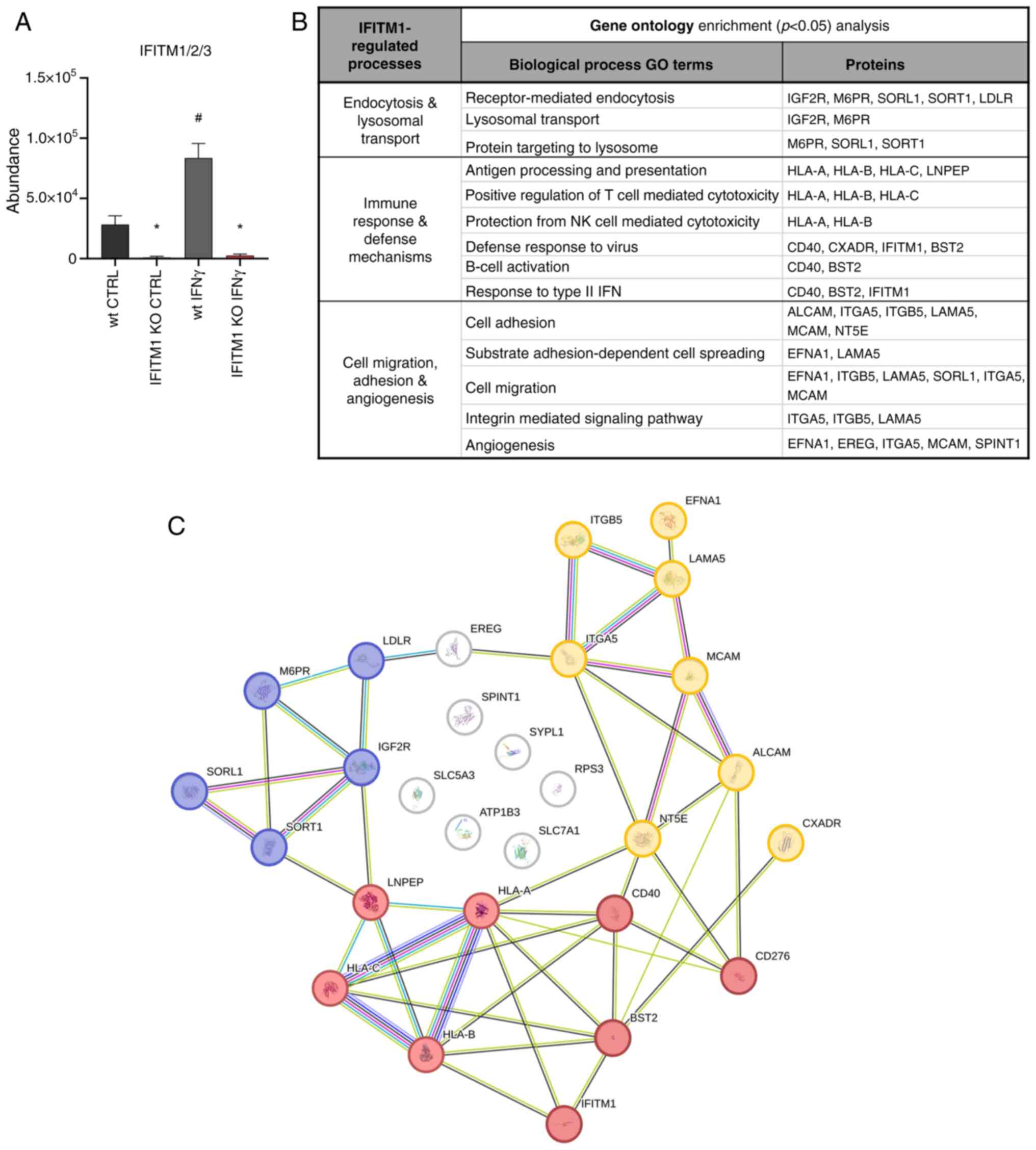

treatment (Fig. 1C, Appendix S1). As expected, IFITM1 was the

protein with the greatest difference in expression and was also

induced by IFNγ (Fig. 2A). GO

analysis using the DAVID bioinformatics tool (20) revealed that IFITM1-regulated

proteins are involved primarily in receptor-mediated endocytosis,

lysosomal transport of proteins, antiviral responses, antigen

processing and presentation, regulation of immune system

activity/function, and cell adhesion and migration (Fig. 2B). Using the STRING database of

known and predicted protein-protein interactions (21), three major groups of interacting

proteins that were significantly downregulated in IFITM1 KO cells

were identified (Fig. 2C).

IFITM1 protein regulates transcript

abundance and modulates protein dynamics

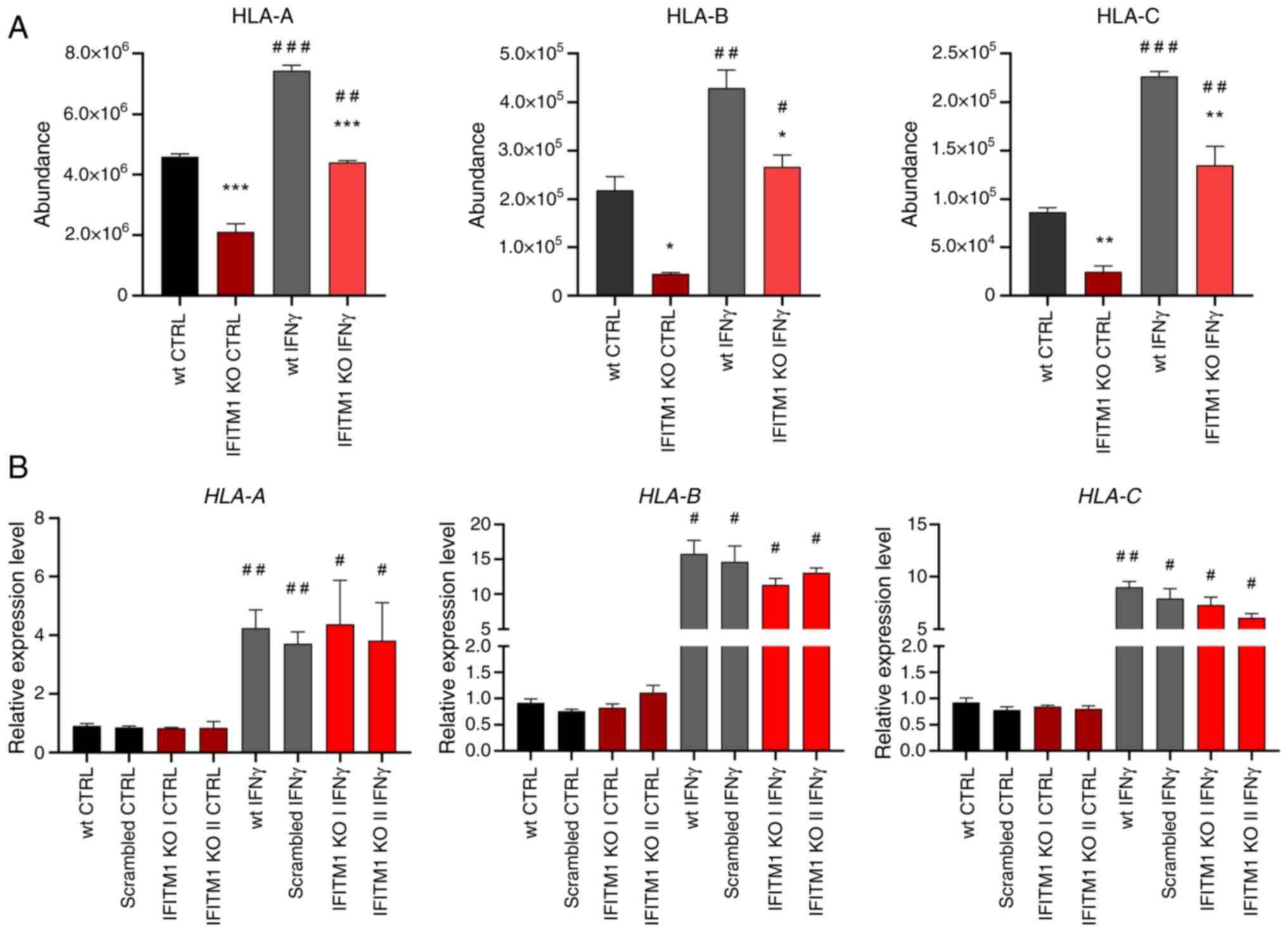

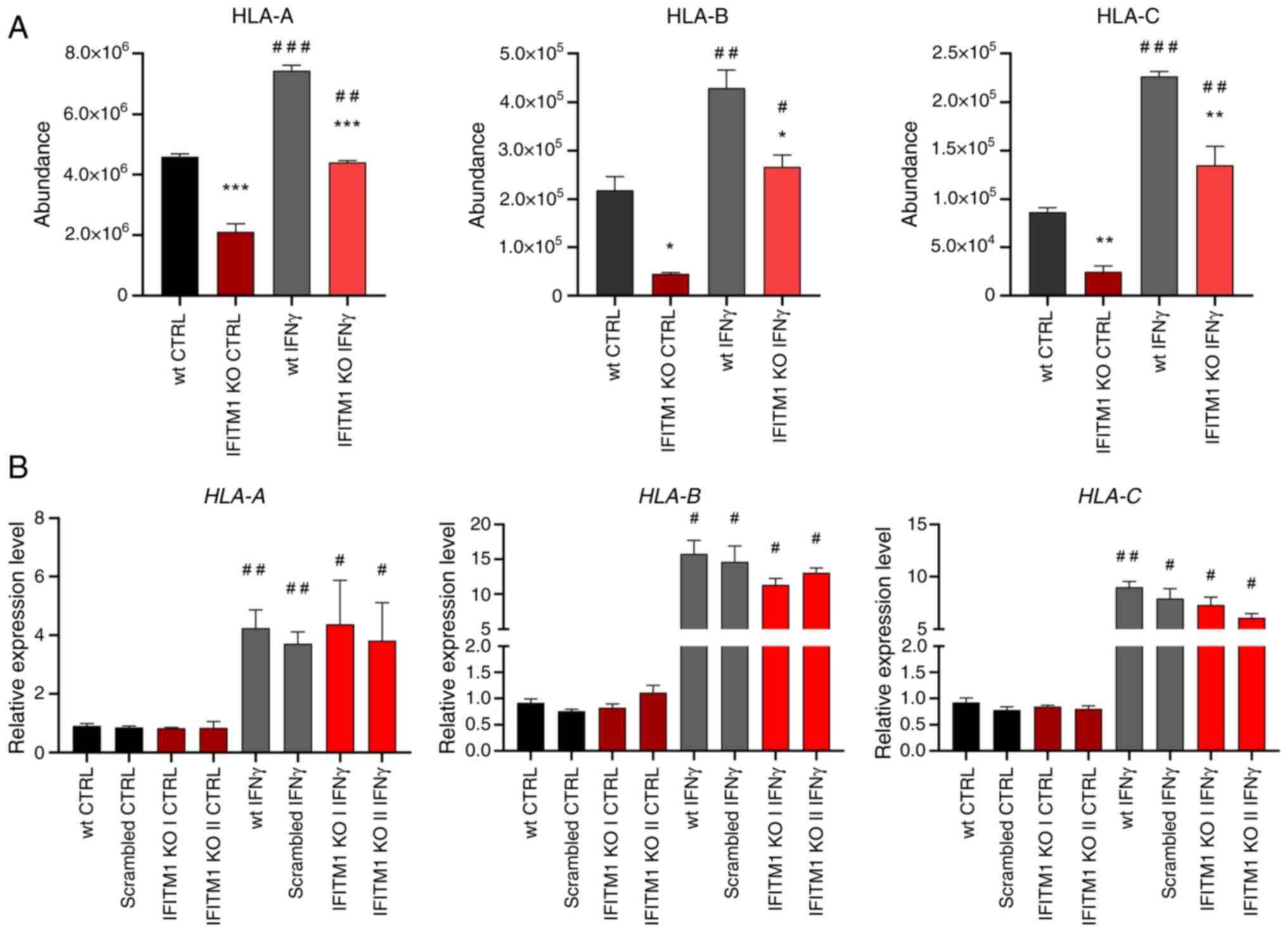

The first group of proteins consists of proteins

essential for antigen presentation and the immune response

(Fig. 2C, red). IFITM1 KO cells

presented reduced surface expression of all three major HLA class I

molecules [HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C (Fig.

3A)] along with decreased levels of antigen-trimming leucyl and

cystinyl aminopeptidase (LNPEP; Fig.

S2). Although IFNγ treatment increased HLA abundance in both wt

and IFITM1 KO cells, the levels remained significantly lower in

IFITM1 KO cells. Gene expression analysis confirmed the increased

transcriptional activity of HLA genes after IFNγ treatment

in both cell lines, with no significant differences between them.

These findings suggested that IFITM1 regulates HLA molecules at the

post-translational level (Fig. 3B),

which is consistent with the authors' previous findings concerning

HLA-B in IFITM1/3 double-KO SiHa cells (29).

| Figure 3.Membrane protein levels and

associated gene expression of HLA class I molecules. (A) Peptide

abundances determined by mass spectrometry analysis as a measure of

HLA protein levels. (B) Determination of HLA gene expression

by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. ACTB was used as

an endogenous control. The level of gene expression is relative to

the value of the wt control (reference sample). The error bars

represent the mean ± SEM from biological replicates. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 when comparing wt and IFITM1 KO;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01, and

###P<0.001 when comparing untreated CTRL and

respective IFNγ-treated samples. HLA, human leukocyte antigen; wt,

wild-type; KO, knockout; CTRL, control; IFN, interferon; IFITM,

interferon-induced transmembrane protein. |

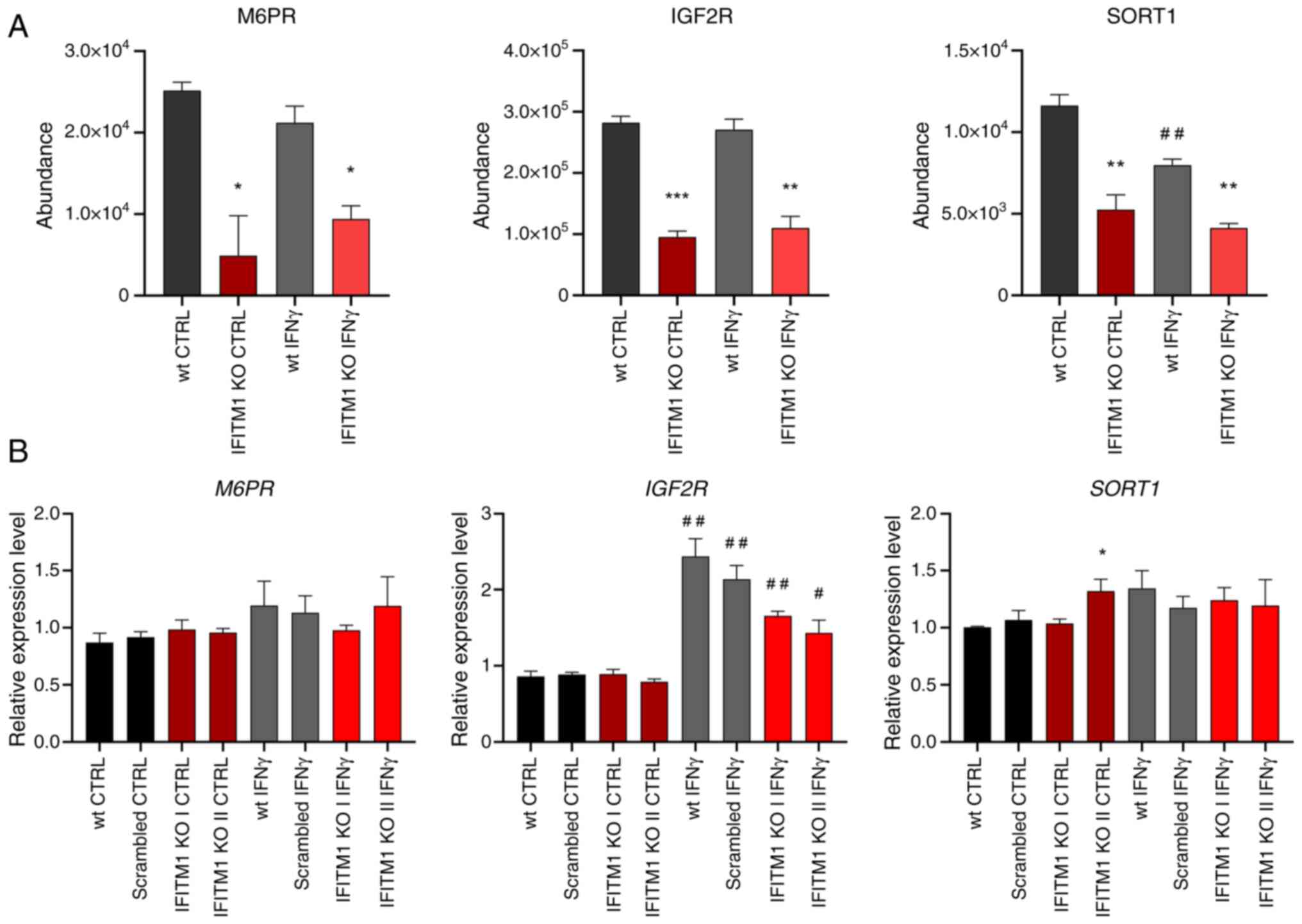

The second group of proteins contains proteins

pertaining to endocytosis, lysosomal transport, and lysosome

function (Fig. 2C, blue), including

mannose 6-phosphate (M6P) receptors (IGF2R and M6PR) and other

M6P-independent sorting receptors [SORT1, sortilin related receptor

1 (SORL1) and LDLR] that are critical for protein trafficking from

the Golgi apparatus to lysosomes and endosomes. IFNγ did not affect

the plasma membrane levels of these proteins (Figs. 4A and S2). Interestingly, SORT1 levels were

reduced upon IFNγ stimulation (Fig.

4A). Gene expression analysis of M6PR and IGF2R

revealed no significant differences between wt and IFITM1 KO cells

(Fig. 4B). Although surfaceome

analysis revealed stable IGF2R membrane levels after IFNγ

treatment, IGF2R gene expression was induced, which is

consistent with reports in microglia (30). Conversely, SORT1 gene

expression remained unchanged under IFNγ treatment (Fig. 4B), highlighting cell-specific

regulatory differences (31).

Variability among IFITM1 KO clones was observed, with one clone

displaying higher SORT1 expression, which did not persist in

the IFN-treated samples and was not reflected in the surfaceome

analysis.

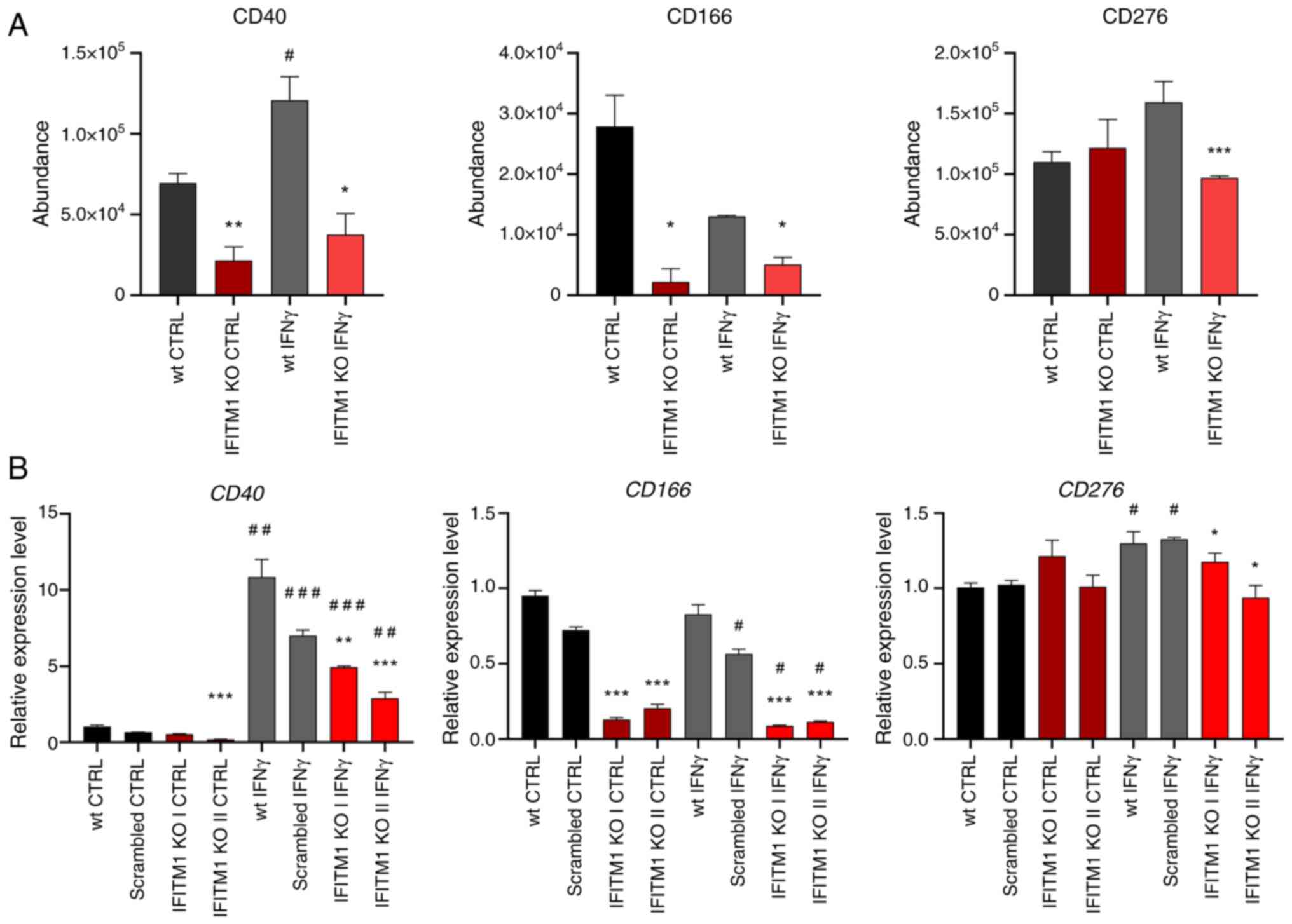

The third group consists of cell adhesion molecules

(CAMs) that mediate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix

interactions (Fig. 2C, yellow).

These multifunctional molecules often act as cell surface

receptors, are overexpressed in cancer, and represent potential

immunotherapy targets [for example, ALCAM-CD166; melanoma CAM

(MCAM)-CD146/Mucin 18, CXADR] (32–34).

Additionally, CD166, CD146 and CD40 play crucial roles in

activating immune responses in tumor tissues. IFITM1-regulated CAMs

include IFNγ-inducible (CD40, CD276) and non-IFNγ-inducible (CD166,

MCAM, EFNA1, CXADR) proteins (Figs.

1C, 5A and S2). Changes in CD40 and CD166 membrane

levels were found to be associated with their respective expression

data (Fig. 5B), confirming that

IFITM1 plays a significant role in regulating genes associated with

tumor progression. Interestingly, IFITM1 depletion alone does not

affect the expression or surface localization of CD276, an immune

checkpoint molecule. However, upon IFNγ treatment, CD276 expression

was upregulated at the RNA level in SiHa wt cells but not in IFITM1

KO cells. A similar trend was observed at the protein surface

level; however, the induction of CD276 in SiHa wt cells did not

reach statistical significance (P=0.06). These findings suggested

that IFITM1 plays an important role in the regulation of CD276 by

IFNγ and provide further evidence that IFITM1 acts as a master

regulator not only for IRDS proteins but also for cell surface

receptors.

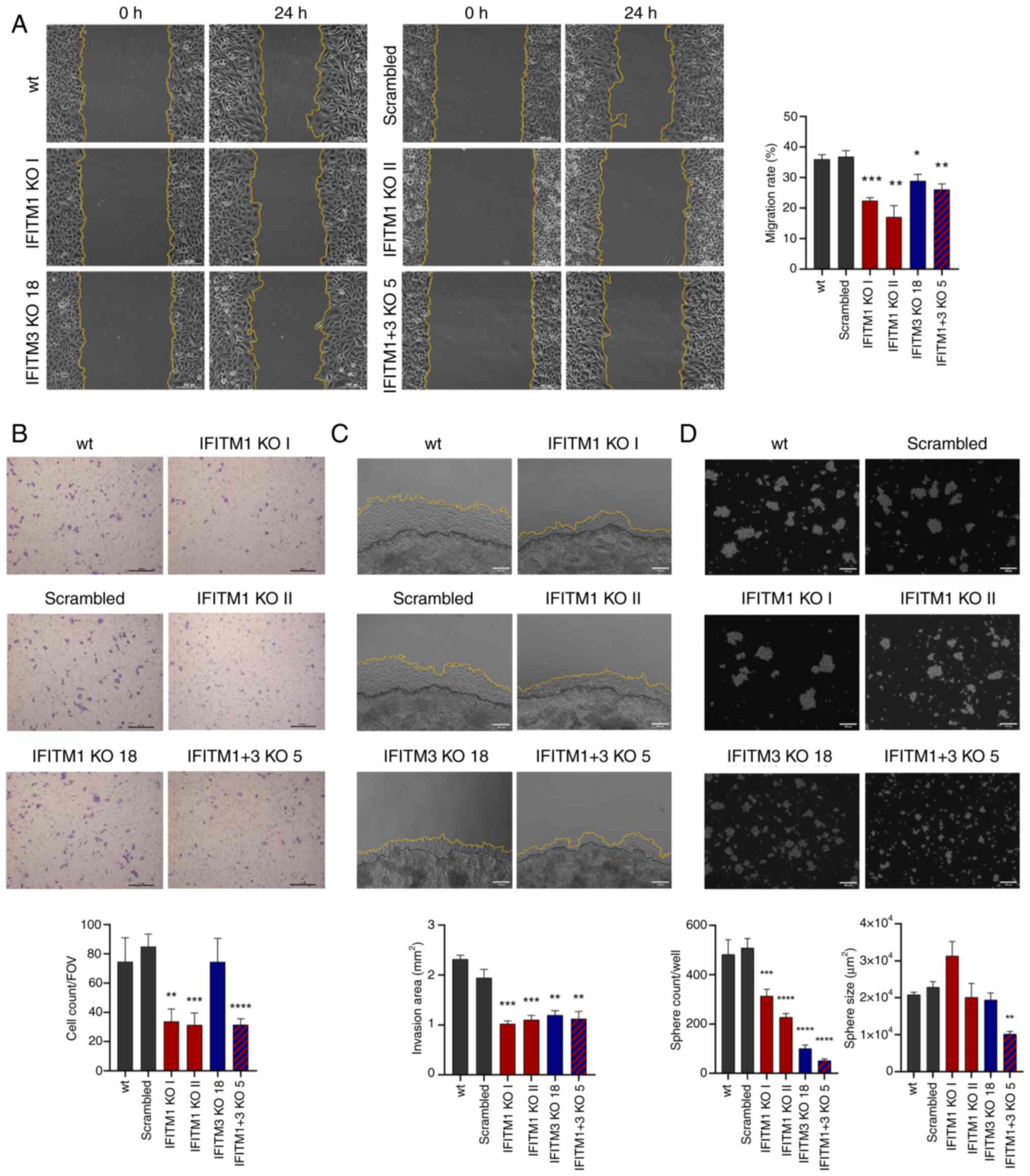

Functional analyses confirm the

involvement of IFITM1 and IFITM3 in the mechanisms driving cancer

progression

Following the analysis of the data obtained from MS,

the effects of the IFITM1 protein were further validated by

performing functional assays focused on cancer cell adhesion,

migration, invasion and sphere formation-processes driven by

changes in surfaceome composition. To verify the impact of the

related IFITM3 protein and its possible relationship with IFITM1,

independent IFITM3 KO and double-knockout IFITM1+3 KO SiHa

derivatives, whose preparation has been previously described, were

also tested (18).

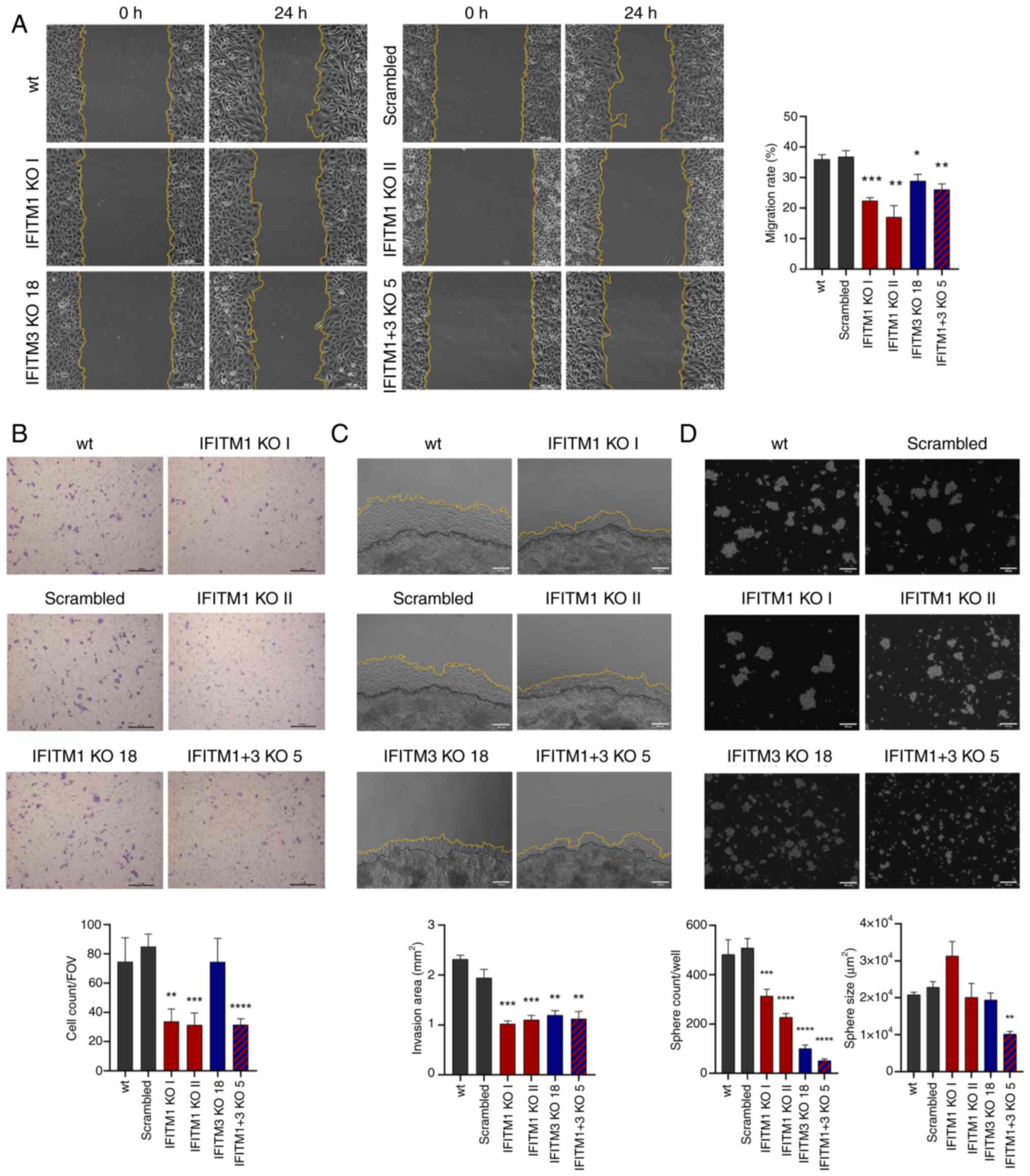

As expected, IFITM1 KO cells migrated more slowly

compared with SiHa wt cells, as shown by the results of the wound

healing (scratch) and Transwell migration assays, which were

evaluated after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 6A and B). Interestingly, IFITM3 KO

cells exhibited significantly reduced migration potential in the

scratch assay, although the Transwell assay did not confirm this

phenotype. When double-knockout IFITM1+3 KO cells were evaluated, a

phenotype with low migratory activity was observed, similar to that

of the IFITM1 KO clones.

| Figure 6.Evaluation of SiHa IFITM KO cell

adhesion, migration and invasion abilities. (A) Representative

images (magnification, ×100) of the wound healing (scratch) assay,

with the borders of the scratch highlighted with yellow lines. The

scratch area was determined at 0 and 24 h using Fiji ImageJ, and

the values were used to calculate the migration rate (%). The

average migration rates of IFITM1 KO, IFITM3 KO and IFITM1+3 KO

cells in comparison with those of control cells (wt, scrambled) are

shown in the graph. (B) Representative images of migratory cells

after 24 h of Transwell assay (scale bar, 200 µm). The graph shows

the average number of cells per field of view (FOV) for individual

IFITM KO clones and their controls. (C) Representative images of

cells invading (yellow line) from 3D Matrigel drops (black line)

taken after 6 days (scale bar, 400 µm). The invasion area

(mm2) was determined by Fiji ImageJ, and the average

values for individual IFITM KO clones and controls are shown in the

graph. (D) Representative images of 10-day cervicopheres formed by

IFITM KO and control cells (scale bar, 400 µm). The average numbers

of all spheres formed per well are compared in the left graph. The

graph on the right shows the average sphere size (µm2)

that was determined using Fiji ImageJ. The error bars represent the

means from biological replicates ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. IFITM, interferon-induced

transmembrane protein; KO, knockout; wt, wild-type. |

To assess invasive ability, a 3D Matrigel drop assay

was performed, which quantifies invading cells embedded in a

Matrigel drop (26). This method

confirmed a reduced capacity to invade through the Matrigel matrix

in all tested IFITM KO clones, on the basis of the extent of the

invasion area evaluated 6 days after Matrigel drop formation

(Fig. 6C).

To evaluate the role of IFITM proteins in cell-cell

adhesion and anchorage-independent growth, the ability of wt and

IFITM1 KO and/or IFITM3 KO cells to form cervicospheres was

compared. All the tested IFITM KO clones exhibited a significantly

reduced capacity to grow as spheres, suggesting that the IFITM1 and

IFITM3 proteins influence intercellular interactions and

cell-extracellular matrix adhesion (Fig. 6D). Notably, compared with IFITM1 KO

cells, IFITM3 KO cells displayed a greater reduction in sphere

formation. However, the most pronounced reduction in both the

number and size of spheres was observed in IFITM1+3 KO cells.

IFITM1 and IFITM3 KO cells show

reduced expression of immunity-related CD markers and increased

resistance to NK cell killing

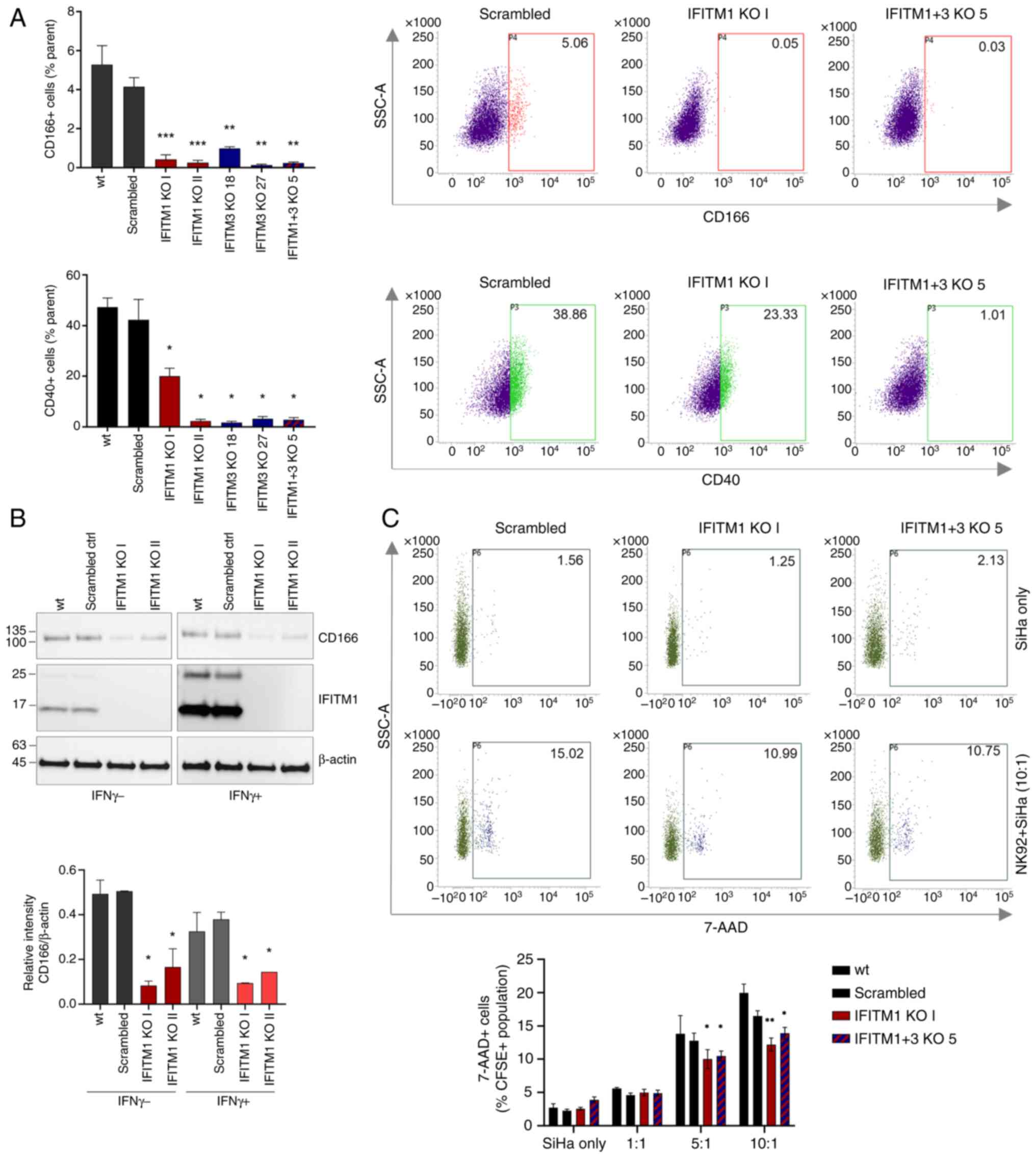

Given the identified group of IFITM1-regulated

proteins involved in immune responses, two selected proteins were

further validated, CD40 and CD166, which are critical factors in

tumor-immune cell interactions.

FACS analysis confirmed reduced CD40 and CD166

levels in all the tested IFITM KO cell clones (Figs. 7A and S3A). Immunoblotting also revealed a

decreased CD166 expression at the total protein level (Fig. 7B). Consistent with the MS and qPCR

findings, immunoblotting of SiHa cell lysates revealed that CD166

expression was not responsive to IFNγ stimulation (Fig. 7B).

Using the NK cytotoxicity assay, which involves the

co-cultivation of tumor and NK cells followed by an analysis of

tumor cell viability, the influence of IFITM proteins on

intercellular communication and the ability of NK cells to

recognize and eliminate tumor cells were examined. This assay

demonstrated that both IFITM1 KO and IFITM1+3 KO cells are

significantly more resistant to NK cell-mediated killing, as

evidenced by a lower percentage of dead (7-AAD+) tumor

cells after 4 h of co-cultivation (Figs. 7C and S3B).

Discussion

Despite advancements in prevention, detection and

treatment, cervical cancer remains a leading cause of

cancer-related mortality in women. Treatment is stage-dependent

(TNM, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

classification), with advanced cases requiring a combination of

surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy (2). Cisplatin remains the cornerstone of

chemotherapy, used alone or in combination, including as

neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor mass before surgery (35). Significant progress has been made in

targeted therapies, with bevacizumab (anti-vascular endothelial

growth factor) and pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 immunotherapy) approved

for recurrent and metastatic cervical cancer (36,37).

Ongoing clinical trials are investigating additional approaches,

such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors, mammalian target

of rapamycin inhibitors and therapeutic HPV vaccines (38).

Despite these advances, the prognosis for

advanced-stage disease remains poor due to tumor heterogeneity and

therapy resistance. The shift toward precision medicine underscores

the need for prognostic and predictive biomarkers to improve

patient stratification and treatment outcomes (3,4). In

this context, surfaceome analysis represents a powerful tool for

identifying therapeutic targets by profiling cell surface

proteins.

IFITM1 was originally identified as a leukocyte

membrane surface antigen and is now known primarily for its

significant antiviral activity (39). Over the past decade, increasing

evidence has shown that IFITM1 is overexpressed in numerous human

solid tumors (6,40). Aberrant expression of IFITM1

promotes tumor cell proliferation, inhibits cell death, stimulates

invasion and metastasis, contributes to cancer cell resistance to

endocrine therapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and has

prognostic value for patient outcomes (6,11,40).

IFITM1 is also part of a subset of IFN-responsive genes that

contribute to the IRDS signature. The authors have demonstrated

that the suppression of IFITM1 via siRNA targeting can impair the

IRDS network (18,41). Current knowledge indicates that

IFITM proteins affect membrane structure and function,

intracellular trafficking, and the turnover of cell surface

receptors (15). IFITM1 has also

been reported to be a tight junction protein (42,43).

It was previously demonstrated that knocking out the IFITM1 and

IFITM3 proteins led to the downregulation of HLA-B expression on

the surface of cervical cancer cells, suggesting an explanation for

the inverse correlation between IFITM1/3 expression and metastasis

formation (18). In the present

study, it was confirmed that, in addition to HLA-B, IFITM1

regulates a whole set of surface proteins in cervical cancer cells,

both with and without dependence on IFNγ. Furthermore, IFITM1

knockout affects the regulation of specific protein surface

expression, either at the level of membrane dynamics or gene

transcription.

Most published studies focus on either one IFITM

family member or the combined effect of several IFITMs without

distinguishing individual members. This is because of the high

homology between IFITM proteins (6), which makes specific targeting

difficult. However, recent studies have overcome these obstacles

and are now describing the different functions of IFITM proteins

(44–47). This phenomenon is particularly

intriguing among such homologous proteins. Therefore, in addition

to focusing on IFITM1, validation and functional assays were

enriched with IFITM3 KO cells, as well as ‘double KO’ cells

depleted of both the IFITM1 and IFITM3 proteins, by the CRISPR/Cas9

gene-editing method to reveal their synergistic effects.

SILAC-based quantitative MS is a widely used

proteomic approach that enables the quantification and evaluation

of protein dynamics within living cells. An additional step

involving surface-protein biotinylation allowed us to enrich

samples with surface/membrane proteins, whose detection in total

lysates is challenging owing to their hydrophobic nature and the

abundance of intracellular proteins. Given the location of IFITM1

in the plasma membrane and its known role in altering membrane

properties during antiviral responses, the surfaceomes of IFITM1 KO

cells and parental SiHa wt cells were measured with or without IFNγ

treatment. The SILAC approach allowed us to evaluate the changes in

protein levels induced by the treatment and compare the membrane

protein levels between IFITM1 KO and SiHa wt cells, including

effects that were dependent on or independent of the presence of

IFNγ.

A total of 28 proteins that were differentially

expressed in wt and IFITM1 KO cells with a fold change of ≥1.5.

Among these proteins, 9 were significantly stimulated by IFNγ. The

present results suggested that IFITM1 affects surfaceome

composition even without IFNγ stimulation, at least in SiHa cell

line, which has a relatively high basal level of IFITM1.

Furthermore, the changes upon IFNγ stimulation indicate the

possible involvement of IFITM1 in the IFN-dependent regulation of

differentially expressed proteins or possible changes in the

functional properties of IFITM1 itself in the presence of IFN. A

detailed understanding of how IFITM1 contributes to IFN signaling

and the subsequent expression of IFN-inducible proteins deserves

further study.

As expected, the protein with the greatest

difference in expression between wt and IFITM1 KO cells was IFITM1.

Only one IFITM peptide was detected by MS, and this peptide is

common to the IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 proteins, thus

distinguishing between them was not possible. Western blot analysis

confirmed that IFITM1 expression was specifically ablated in IFITM1

KO cells, while IFITM2 and IFITM3 expression was preserved, albeit

with a slight decrease, particularly in the presence of IFNγ. This

reduction may result from the tight co-regulation of these proteins

due to shared regulatory elements, the stabilizing effects of

hetero-oligomer formation within cellular membranes, and

alterations in IFN response dynamics caused by IFITM1 KO, which may

further influence the expression of IFN-stimulated genes, including

IFITMs, through feedback regulation (6,18).

Together with the predominant localization of IFITM1 on the cell

surface (in contrast to IFITM2 and IFITM3, which are mostly located

in endosomes/lysosomes), it was hypothesized that the identified

peptide originated from IFITM1, with a minor contribution from

IFITM2/3, which can be temporarily found on the cell surface before

their internalization into endosomes (48). This also explains the presence of

small amounts of the IFITM peptide in the IFITM1 KO samples.

Despite the advantages of quantitative proteomics,

limitations in peptide quantification and reproducibility may lead

to the exclusion of relevant targets. Nonetheless, this approach

enabled us to identify entire functional protein groups, which led

to the discovery of IFITM1-regulated processes central to our

study. The proteins, whose levels in the plasma membrane were

downregulated by IFITM1 knockout, can be classified into three main

groups according to their function: Endocytosis and lysosomal

transport, antigen processing and presentation together with

regulation of the immune response, and cell adhesion and migration.

The regulation of the rate and manner of endocytosis controls the

exposure and abundance of membrane proteins at the cell surface.

Once internalized, proteins undergo recycling or degradation in

lysosomes through autophagy. IFITM proteins are known to modulate

membrane rigidity and curvature, cholesterol content, trafficking

of endocytosed cargo, and endosomal/lysosomal pH, thereby affecting

viral entry into cells (12,13,15–17,49).

According to our MS data, IFITM1 affects several proteins linked to

receptor-mediated endocytosis and endosomal/lysosomal trafficking

(LDLR, IGF2R, M6PR, SORT1 and SORL1). On the basis of the unchanged

gene expression levels of selected representatives of this

functional group (IGF2R, M6PR and SORT1) in IFITM1 KO cells, it was

hypothesized that, along with effects on the biophysical properties

of membranes, IFITM1 affects the exposure and turnover of numerous

membrane proteins, which may be another explanation for its broad

antiviral properties and underscores its significant role in tumor

progression. A more detailed description of how IFITM proteins

regulate the stability and localization of other proteins is the

subject of our further investigation.

The dysregulation of cell migration, adhesion and

invasion regulators, such as MCAM/CD146, ALCAM/CD166, CAR/CXADR,

EFNA1, LAMA5, CD73/NT5E and integrins, contributes to cancer

progression and metastasis (50–55).

The importance of IFITM1 in these processes is supported by

functional assays showing a decreased ability of IFITM1 KO cells to

migrate (toward the scratch or across the porous membrane) and

invade through Matrigel, which represents the extracellular matrix.

These results are consistent with findings in various tumor types

reported in the literature (56–58).

However, little is known about IFITM proteins in cervical cancer.

In contrast, Zheng et al (59) reported that migration was inhibited

after the transfection of HeLa cells with an IFITM1 recombinant

construct. While IFITM1 KO clones showed consistent results across

migration assays, the IFITM3 KO 18 clone exhibited a discrepancy.

IFITM3 KO cells migrated similarly to controls in the Transwell

assay, but their migratory ability was significantly reduced in the

scratch assay. This may be due to the distinct principles of each

assay: the Transwell assay measures individual cell migration,

where cytoskeletal components are crucial, while the scratch assay

focuses on collective migration, which relies on cell-cell adhesion

molecules. Both IFITM1 and IFITM3 are associated with membrane

structure and dynamics, which are closely linked to cytoskeletal

remodeling. However, their functions may differ due to differences

in their localization and expression patterns (6).

To evaluate adhesion properties, the cells were

allowed to proliferate in low-attachment plates, forcing them to

adhere to each other and form cervicospheres. IFITM1 and IFITM3 KO

clones showed a diminished ability to form spheres, as evaluated on

the basis of sphere counts. Compared with single KO, the knockout

of both IFITM1 and IFITM3 had a synergistic effect. Interestingly,

when evaluating the size of the formed spheres, clones deficient in

one of the IFITM proteins did not differ from the controls, whereas

deficiency in both proteins led to significantly smaller cell

aggregates. Sphere formation assays are typically used to evaluate

stem cell properties. However, changes in stem cell markers among

IFITM KO clones (data not shown) were not observed, indicating that

the observed differences are due to alterations in adhesion

proteins.

Surfaceome analysis confirmed our previous findings

that IFITM proteins affect the exposure of MHC-I molecules at the

surface of cervical cancer cells (18), which might be important for cancer

cell interactions with the immune system, supporting tumor immune

escape (60). These findings were

recently confirmed by She et al (61), who described the effect of IFITM1

expression on the brain colonization of human lung cancer cells

through the regulation of the membrane localization of MHC-I and

the enhancement of CD8+ T-cell cytolytic activity.

Interestingly, it was also shown that IFITM1 deficiency does not

affect the expression level of HLA genes, suggesting that

IFITM1 instead affects the dynamics of proteins within the

membrane. This finding is consistent with our previous results on

the HLA-B gene (29).

Additionally, IFN-independent LNPEP aminopeptidase, which is

important for antigen trimming before MHC-I-mediated presentation

(62), was identified among the

downregulated molecules in IFITM1 KO cells. Other proteins

regulated by IFITM1 that could be involved in antitumor immune

responses include CD40 (63–65),

CD166 (32,66), MCAM/CD146 (67,68)

and CXADR (52). Interestingly,

differences were observed in the involvement of the IFNγ signaling

pathway in the regulation of CD markers. The membrane levels of the

IFN-inducible CD40 and CD276 proteins correlated with the gene

expression levels. IFITM1 knockout leads to CD40 downregulation

irrespective of the presence of IFNγ and abolishes IFN-induced

CD276 expression, which is also reflected in the membrane exposure

of the protein. Furthermore, IFITM1 decreases the expression of

CD166, which is unresponsive to IFNγ treatment, as confirmed by

SILAC, qPCR and western blot analysis. The surface levels of the

CD40 and CD166 proteins were further validated and significant

downregulation of the IFITM1 and IFITM3 KO SiHa derivatives was

confirmed. Consistent with the differential levels of

immune-related proteins, IFITM1 KO and IFITM1+3 KO clones escaped

the effects of NK cells, as demonstrated by the NK cytotoxicity

assay. Other studies that link IFITM proteins with innate and

adaptive immunity are emerging, highlighting the potential role of

these proteins in tumor immunosurveillance (69–71).

Uncovering the exact mechanism by which IFITMs regulate these

proteins and thereby hinder antitumor immunity will be the subject

of our further investigations.

In conclusion, the importance of the IFITM1 and

IFITM3 proteins in processes that depend on the composition of

proteins in the plasma membrane, such as cell adhesion, migration,

invasion and interaction with immune cells was confirmed. The

presented results confirm the authors' hypothesis that IFITM

proteins regulate the expression and membrane exposure of proteins,

thereby facilitating tumor progression while also supporting tumor

immunosurveillance. The precise mechanism by which IFITM1 modulates

the membrane presentation of identified proteins remains the

subject of ongoing research.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Czech Science Foundation

(grant no. 23-06884S), the project SALVAGE (P JAC; grant no.

CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004644) funded by the European Union and by

the State Budget of the Czech Republic, and MH CZ-DRO (MMCI; grant

no. 00209805).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The data generated in the

present study may be found in the PRIDE database under accession

number PXD053951 or at the following URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD053951.

Authors' contributions

NF and MN designed the present study, performed the

experiments and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. LB

designed the study and conducted the experiments. LD and LU

performed proteomic measurements. LH designed the proteomic

methodology and data analysis. TRH and BV provided key revisions of

the manuscript and conducted data interpretation. NF and MN confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

7-AAD

|

7-aminoactinomycin D

|

|

ALCAM

|

activated leukocyte cell adhesion

molecule

|

|

CAM

|

cell adhesion molecules

|

|

CFSE

|

carboxy-fluorescein succinimidyl

ester

|

|

CXADR

|

coxsackie virus and adenovirus

receptor

|

|

ECL

|

enhanced chemiluminescence

|

|

EFNA1

|

ephrin A1

|

|

FASP

|

filter-aided sample preparation

protocol

|

|

FDR

|

false discovery rate

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

HLA

|

human leukocyte antigen

|

|

IFITM

|

interferon-induced transmembrane

protein

|

|

IFN

|

interferon

|

|

IGF2R

|

insulin-like growth factor 2

receptor

|

|

IRDS

|

IFN-related DNA damage resistance

signature

|

|

KO

|

knockout

|

|

LDLR

|

low-density lipoprotein receptor

|

|

LNPEP

|

leucyl and cystinyl

aminopeptidase

|

|

M6P

|

mannose-6-phosphate

|

|

M6PR

|

M6P receptor

|

|

MCAM

|

melanoma CAM

|

|

MHC-I

|

major histocompatibility complex

class I

|

|

PBST

|

phosphate-buffered saline with Tween

20

|

|

RSLC

|

rapid separation liquid

chromatography

|

|

SILAC

|

stable isotope labeling with amino

acids in cell culture

|

|

SORL1

|

sortilin related receptor 1

|

|

SORT1

|

sortilin 1

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

D'Augè TG, Donato VD and Giannini A:

Strategic approaches in management of early-stage cervical cancer:

A comprehensive editorial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 51:2352024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Garg P, Krishna M, Subbalakshmi AR,

Ramisetty S, Mohanty A, Kulkarni P, Horne D, Salgia R and Singhal

SS: Emerging biomarkers and molecular targets for precision

medicine in cervical cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1879:1891062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

D'Oria O, Bogani G, Cuccu I, D'Auge TG, Di

Donato V, Caserta D and Giannini A: Pharmacotherapy for the

treatment of recurrent cervical cancer: An update of the

literature. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 25:55–65. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bausch-Fluck D, Goldmann U, Müller S, van

Oostrum M, Müller M, Schubert OT and Wollscheid B: The in silico

human surfaceome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:E10988–E10997. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Friedlová N, Zavadil Kokáš F, Hupp TR,

Vojtěšek B and Nekulová M: IFITM protein regulation and functions:

Far beyond the fight against viruses. Front Immunol.

13:10423682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Narayana SK, Helbig KJ, McCartney EM, Eyre

NS, Bull RA, Eltahla A, Lloyd AR and Beard MR: The

interferon-induced transmembrane proteins, IFITM1, IFITM2, and

IFITM3 inhibit hepatitis C virus entry. J Biol Chem.

290:25946–25959. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Prelli Bozzo C, Nchioua R, Volcic M,

Koepke L, Krüger J, Schütz D, Heller S, Stürzel CM, Kmiec D,

Conzelmann C, et al: IFITM proteins promote SARS-CoV-2 infection

and are targets for virus inhibition in vitro. Nat Commun.

12:45842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ren L, Du S, Xu W, Li T, Wu S, Jin N and

Li C: Current progress on host antiviral factor IFITMs. Front

Immunol. 11:5434442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liao Y, Goraya MU, Yuan X, Zhang B, Chiu

SH and Chen JL: Functional involvement of interferon-inducible

trans-membrane proteins in antiviral immunity. Front Microbiol.

10:10972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gómez-Herranz M, Taylor J and Sloan RD:

IFITM proteins: Understanding their diverse roles in viral

infection, cancer, and immunity. J Biol Chem. 299:1027412023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li K, Markosyan RM, Zheng YM, Golfetto O,

Bungart B, Li M, Ding S, He Y, Liang C, Lee JC, et al: IFITM

proteins restrict viral membrane hemifusion. PLoS Pathog.

9:e10031242013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, Choi YJ, Lee JH, Shi

M, Huang IC, Farzan M and Jung JU: The antiviral effector IFITM3

disrupts intracellular cholesterol homeostasis to block viral

entry. Cell Host Microbe. 13:452–464. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rahman K, Datta SAK, Beaven AH, Jolley AA,

Sodt AJ and Compton AA: Cholesterol binds the amphipathic helix of

IFITM3 and regulates antiviral activity. J Mol Biol.

434:1677592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Spence JS, He R, Hoffmann HH, Das T,

Thinon E, Rice CM, Peng T, Chandran K and Hang HC: IFITM3 directly

engages and shuttles incoming virus particles to lysosomes. Nat

Chem Biol. 15:259–268. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gerlach T, Hensen L, Matrosovich T,

Bergmann J, Winkler M, Peteranderl C, Klenk HD, Weber F, Herold S,

Pöhlmann S and Matrosovich M: pH optimum of hemagglutinin-mediated

membrane fusion determines sensitivity of influenza A viruses to

the interferon-induced antiviral state and IFITMs. J Virol.

91:e00246–17. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wee YS, Roundy KM, Weis JJ and Weis JH:

Interferon-inducible transmembrane proteins of the innate immune

response act as membrane organizers by influencing clathrin and

v-ATPase localization and function. Innate Immun. 18:834–845. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gómez-Herranz M, Nekulova M, Faktor J,

Hernychova L, Kote S, Sinclair EH, Nenutil R, Vojtesek B, Ball KL

and Hupp TR: The effects of IFITM1 and IFITM3 gene deletion on IFNγ

stimulated protein synthesis. Cell Signal. 60:39–56. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N and

Mann M: Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis.

Nat Methods. 6:359–362. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, Jiao X, Baseler

MW, Lane HC, Imamichi T and Chang W: DAVID: A web server for

functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene

lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50:W216–W221. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D,

Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, et al:

The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks,

and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement

sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49:D605–D612. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J,

Bernal-Llinares M, Hewapathirana S, Kundu DJ, Inuganti A, Griss J,

Mayer G, Eisenacher M, et al: The PRIDE database and related tools

and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data.

Nucleic Acids Res. 47:D442–D450. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E,

Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S,

Schmid B, et al: Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image

analysis. Nat Methods. 9:676–682. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Grada A, Otero-Vinas M, Prieto-Castrillo

F, Obagi Z and Falanga V: Research techniques made simple: Analysis

of collective cell migration using the wound healing assay. J

Invest Dermatol. 137:e11–e16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Suarez-Arnedo A, Figueroa FT, Clavijo C,

Arbeláez P, Cruz JC and Muñoz-Camargo C: An image J plugin for the

high throughput image analysis of in vitro scratch wound healing

assays. PLoS One. 15:e02325652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Aslan M, Hsu EC, Liu S and Stoyanova T:

Quantifying the invasion and migration ability of cancer cells with

a 3D Matrigel drop invasion assay. Biol Methods Protoc.

6:bpab0142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nekulová M, Wyszkowska M, Friedlová N,

Uhrík L, Zavadil Kokáš F, Hrabal V, Hernychová L, Vojtěšek B, Hupp

TR and Szymański MR: Biochemical evidence for conformational

variants in the anti-viral and pro-metastatic protein IFITM1. Biol

Chem. 405:311–324. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gómez-Herranz M, Faktor J, Yébenes

Mayordomo M, Pilch M, Nekulova M, Hernychova L, Ball KL, Vojtesek

B, Hupp TR and Kote S: Emergent role of IFITM1/3 towards splicing

factor (SRSF1) and antigen-presenting molecule (HLA-B) in cervical

cancer. Biomolecules. 12:10902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Suh HS, Cosenza-Nashat M, Choi N, Zhao ML,

Li JF, Pollard JW, Jirtle RL, Goldstein H and Lee SC: Insulin-like

growth factor 2 receptor is an IFNgamma-inducible microglial

protein that facilitates intracellular HIV replication:

Implications for HIV-induced neurocognitive disorders. Am J Pathol.

177:2446–2458. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pirault J, Polyzos KA, Petri MH, Ketelhuth

DFJ, Bäck M and Hansson GK: The inflammatory cytokine

interferon-gamma inhibits sortilin-1 expression in hepatocytes via

the JAK/STAT pathway. Eur J Immunol. 47:1918–1924. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ferragut F, Vachetta VS, Troncoso MF,

Rabinovich GA and Elola MT: ALCAM/CD166: A pleiotropic mediator of

cell adhesion, stemness and cancer progression. Cytokine Growth

Factor Rev. 61:27–37. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wu Z, Wu Z, Li J, Yang X, Wang Y, Yu Y, Ye

J, Xu C, Qin W and Zhang Z: MCAM is a novel metastasis marker and

regulates spreading, apoptosis and invasion of ovarian cancer

cells. Tumour Biol. 33:1619–1628. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kawada M, Inoue H, Kajikawa M, Sugiura M,

Sakamoto S, Urano S, Karasawa C, Usami I, Futakuchi M and Masuda T:

A novel monoclonal antibody targeting coxsackie virus and

adenovirus receptor inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Sci Rep.

7:404002017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li J, Li Y, Wang H, Shen L, Wang Q, Shao

S, Shen Y, Xu H, Liu H, Cai R and Feng W: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

with weekly cisplatin and paclitaxel followed by chemoradiation for

locally advanced cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 23:512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tewari KS, Colombo N, Monk BJ, Dubot C,

Cáceres MV, Hasegawa K, Shapira-Frommer R, Salman P, Yañez E, Gümüs

M, et al: Pembrolizumab or placebo plus chemotherapy with or

without bevacizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic

cervical cancer: Subgroup analyses from the KEYNOTE-826 randomized

clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 10:1852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Monk BJ, Enomoto T, Kast WM, McCormack M,

Tan DSP, Wu X and González-Martín A: Integration of immunotherapy

into treatment of cervical cancer: Recent data and ongoing trials.

Cancer Treat Rev. 106:1023852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kumar Kore R, Shirbhate E, Singh V, Mishra

A, Veerasamy R and Rajak H: New investigational drug's targeting

various molecular pathways for treatment of cervical cancer:

Current status and future prospects. Cancer Invest. 42:627–642.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bailey CC, Zhong G, Huang IC and Farzan M:

IFITM-family proteins: The cell's first line of antiviral defense.

Annu Rev Virol. 1:261–283. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liang R, Li X and Zhu X: Deciphering the

roles of IFITM1 in tumors. Mol Diagn Ther. 24:433–441. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Weichselbaum RR, Ishwaran H, Yoon T,

Nuyten DS, Baker SW, Khodarev N, Su AW, Shaikh AY, Roach P, Kreike

B, et al: An interferon-related gene signature for DNA damage

resistance is a predictive marker for chemotherapy and radiation

for breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:18490–18495. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Popson SA, Ziegler ME, Chen X, Holderfield

MT, Shaaban CI, Fong AH, Welch-Reardon KM, Papkoff J and Hughes CC:

Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 regulates endothelial

lumen formation during angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

34:1011–1019. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wilkins C, Woodward J, Lau DTY, Barnes A,

Joyce M, McFarlane N, McKeating JA, Tyrrell DL and Gale M Jr:

IFITM1 is a tight junction protein that inhibits hepatitis C virus

entry. Hepatology. 57:461–469. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Buchrieser J, Dufloo J, Hubert M, Monel B,

Planas D, Rajah MM, Planchais C, Porrot F, Guivel-Benhassine F, Van

der Werf S, et al: Syncytia formation by SARS-CoV-2-infected cells.

EMBO J. 39:e1062672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Chmielewska AM, Gómez-Herranz M, Gach P,

Nekulova M, Bagnucka MA, Lipińska AD, Rychłowski M, Hoffmann W,

Król E, Vojtesek B, et al: The role of IFITM proteins in tick-borne

encephalitis virus infection. J Virol. 96:e01130212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Basile A, Zannella C, De Marco M, Sanna G,

Franci G, Galdiero M, Manzin A, De Laurenzi V, Chetta M, Rosati A,

et al: Spike-mediated viral membrane fusion is inhibited by a

specific anti-IFITM2 monoclonal antibody. Antiviral Res.

211:1055462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Meischel T, Fritzlar S, Villalon-Letelier

F, Tessema MB, Brooks AG, Reading PC and Londrigan SL: IFITM

proteins that restrict the early stages of respiratory virus

infection do not influence late-stage replication. J Virol.

95:e00837212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Jia R, Xu F, Qian J, Yao Y, Miao C, Zheng

YM, Liu SL, Guo F, Geng Y, Qiao W and Liang C: Identification of an

endocytic signal essential for the antiviral action of IFITM3. Cell

Microbiol. 16:1080–1093. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ishikawa-Sasaki K, Murata T and Sasaki J:

IFITM1 enhances nonenveloped viral RNA replication by facilitating

cholesterol transport to the Golgi. PLoS Pathog. 19:e10113832023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

von Lersner A, Droesen L and Zijlstra A:

Modulation of cell adhesion and migration through regulation of the

immunoglobulin superfamily member ALCAM/CD166. Clin Exp Metastasis.

36:87–95. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shen X, Li M, Lei Y, Lu S, Wang S, Liu Z,

Wang C, Zhao Y, Wang A, Bi C and Zhu G: An integrated analysis of

single-cell and bulk transcriptomics reveals EFNA1 as a novel

prognostic biomarker for cervical cancer. Hum Cell. 35:705–720.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Owczarek C, Elmasry Y and Parsons M:

Contributions of coxsackievirus adenovirus receptor to

tumorigenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 51:1143–1155. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liu F, Wu Q, Dong Z and Liu K: Integrins

in cancer: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

Pharmacol Ther. 247:1084582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Diao B, Sun C, Yu P, Zhao Z and Yang P:

LAMA5 promotes cell proliferation and migration in ovarian cancer

by activating Notch signaling pathway. FASEB J. 37:e231092023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang L, Zhou X, Zhou T, Ma D, Chen S, Zhi

X, Yin L, Shao Z, Ou Z and Zhou P: Ecto-5′-nucleotidase promotes

invasion, migration and adhesion of human breast cancer cells. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 134:365–372. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yang Y, Koh YW, Sari IN, Jun N, Lee S, Phi

LTH, Kim KS, Wijaya YT, Lee SH, Baek MJ, et al: Interferon-induced

transmembrane protein 1-mediated EGFR/SOX2 signaling axis is

essential for progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Int J

Cancer. 144:2020–2032. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Hatano H, Kudo Y, Ogawa I, Tsunematsu T,

Kikuchi A, Abiko Y and Takata T: IFN-induced transmembrane protein

1 promotes invasion at early stage of head and neck cancer

progression. Clin Cancer Res. 14:6097–6105. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liang Y, Li E, Min J, Gong C, Gao J, Ai J,

Liao W and Wu L: MiR-29a suppresses the growth and metastasis of

hepatocellular carcinoma through IFITM3. Oncol Rep. 40:3261–3272.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zheng W, Zhao Z, Yi X, Zuo Q, Li H, Guo X,

Li D, He H, Pan Z, Fan P, et al: Down-regulation of IFITM1 and its

growth inhibitory role in cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer

Cell Int. 17:882017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Taylor BC and Balko JM: Mechanisms of

MHC-I downregulation and role in immunotherapy response. Front

Immunol. 13:8448662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

She X, Shen S, Chen G, Gao Y, Ma J, Gao Y,

Liu Y, Gao G, Zhao Y, Wang C, et al: Immune surveillance of brain

metastatic cancer cells is mediated by IFITM1. EMBO J.

42:e1111122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Saveanu L and van Endert P: The role of

insulin-regulated aminopeptidase in MHC class I antigen

presentation. Front Immunol. 3:572012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Elgueta R, Benson MJ, de Vries VC, Wasiuk

A, Guo Y and Noelle RJ: Molecular mechanism and function of

CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol Rev.

229:152–172. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Grewal IS, Foellmer HG, Grewal KD, Xu J,

Hardardottir F, Baron JL, Janeway CA Jr and Flavell RA: Requirement

for CD40 ligand in costimulation induction, T cell activation, and

experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Science. 273:1864–1867.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Djureinovic D, Wang M and Kluger HM:

Agonistic CD40 antibodies in cancer treatment. Cancers (Basel).

13:13022021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Yang Y, Sanders AJ, Ruge F, Dong X, Cui Y,

Dou QP, Jia S, Hao C, Ji J and Jiang WG: Activated leukocyte cell

adhesion molecule (ALCAM)/CD166 in pancreatic cancer, a pivotal

link to clinical outcome and vascular embolism. Am J Cancer Res.

11:5917–5932. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Jing L, An Y, Cai T, Xiang J, Li B, Guo J,

Ma X, Wei L, Tian Y, Cheng X, et al: A subpopulation of

CD146+ macrophages enhances antitumor immunity by

activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell Mol Immunol. 20:908–923.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Duan H, Jing L, Jiang X, Ma Y, Wang D,

Xiang J, Chen X, Wu Z, Yan H, Jia J, et al: CD146 bound to LCK

promotes T cell receptor signaling and antitumor immune responses

in mice. J Clin Invest. 131:e1485682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Yánez DC, Ross S and Crompton T: The IFITM

protein family in adaptive immunity. Immunology. 159:365–372. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Cai Y, Ji W, Sun C, Xu R, Chen X, Deng Y,

Pan J, Yang J, Zhu H and Mei J: Interferon-induced transmembrane

protein 3 shapes an inflamed tumor microenvironment and identifies

immuno-hot tumors. Front Immunol. 12:7049652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Shen C, Li YJ, Yin QQ, Jiao WW, Li QJ,

Xiao J, Sun L, Xu F, Li JQ, Qi H and Shen AD: Identification of

differentially expressed transcripts targeted by the knockdown of

endogenous IFITM3. Mol Med Rep. 14:4367–4373. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|